Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Invasion of Poland

View on Wikipedia

| Invasion of Poland | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the European theatre of World War II | |||||||||

Left to right, top to bottom: Luftwaffe bombers over Poland; Schleswig-Holstein attacking the Westerplatte; Danzig Police destroying the Polish border post (re-enactment); German tank and armored car formation; German and Soviet troops shaking hands; bombing of Warsaw. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| |||||||||

The invasion of Poland,[e] also known as the September Campaign,[f] Polish Campaign,[g] and Polish Defensive War of 1939[h][13] (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak Republic, and the Soviet Union, which marked the beginning of World War II.[14] The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union, and one day after the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union had approved the pact.[15] The Soviets invaded Poland on 17 September. The campaign ended on 6 October with Germany and the Soviet Union dividing and annexing the whole of Poland under the terms of the German–Soviet Frontier Treaty.

The aim of the invasion was to disestablish Poland as a sovereign country, with its citizens destined for extermination.[16][17][18] German and Slovak forces invaded Poland from the north, south, and west the morning after the Gleiwitz incident. As the Wehrmacht advanced, Polish forces withdrew from their forward bases of operation close to the Germany–Poland border to more established defense lines to the east. After the mid-September Polish defeat in the Battle of the Bzura, the Germans gained an undisputed advantage. Polish forces then withdrew to the southeast where they prepared for a long defence of the Romanian Bridgehead and awaited expected support and relief from France and the United Kingdom.[19] On 3 September, based on their alliance agreements with Poland, the United Kingdom and France declared war on Germany; in the end their aid to Poland was very limited. France invaded a small part of Germany in the Saar Offensive, and the Polish army was effectively defeated even before the British Expeditionary Force could be transported to continental Europe.

On 17 September, the Soviet Red Army invaded Eastern Poland, the territory beyond the Curzon Line that fell into the Soviet "sphere of influence" according to the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact; this rendered the Polish plan of defence obsolete.[20] Facing a second front, the Polish government concluded the defence of the Romanian Bridgehead was no longer feasible and ordered an emergency evacuation of all troops to neutral Romania.[21] On 6 October, following the Polish defeat at the Battle of Kock, German and Soviet forces gained full control over Poland. The success of the invasion marked the end of the Second Polish Republic, though Poland never formally surrendered.

On 8 October, after an initial period of military administration, Germany directly annexed western Poland and the former Free City of Danzig and placed the remaining block of territory under the administration of the newly established General Government. The Soviet Union incorporated its newly acquired areas into its constituent Byelorussian and Ukrainian republics, and immediately started a campaign of Sovietization. In the aftermath of the invasion, a collective of underground resistance organizations formed the Polish Underground State within the territory of the former Polish state. Many of the military exiles who escaped Poland joined the Polish Armed Forces in the West, an armed force loyal to the Polish government-in-exile.

Background

[edit]On 30 January 1933, the National Socialist German Workers' Party, under its leader Adolf Hitler, came to power in Germany.[22] While some dissident elements within the Weimar Republic had long sought to annex territories belonging to Poland, it was Hitler's own idea and not a realization of any pre-1933 Weimar plans to invade and partition Poland,[23] annex Bohemia and Austria, and create satellite or puppet states economically subordinate to Germany.[24] As part of this long-term policy, Hitler at first pursued a policy of rapprochement with Poland, trying to improve opinion in Germany, culminating in the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934.[25] Earlier, Hitler's foreign policy worked to weaken ties between Poland and France and attempted to manoeuvre Poland into the Anti-Comintern Pact, forming a cooperative front against the Soviet Union.[25][26] Poland would be granted territory to its northeast in Ukraine and Belarus if it agreed to wage war against the Soviet Union, but the concessions the Poles were expected to make meant that their homeland would become largely dependent on Germany, functioning as little more than a client state. The Poles feared that their independence would eventually be threatened altogether;[26] historically Hitler had already denounced the right of Poland to independence in 1930, writing that Poles and Czechs were a "rabble not worth a penny more than the inhabitants of Sudan or India. How can they demand the rights of independent states?"[27]

The population of the Free City of Danzig was strongly in favour of annexation by Germany, as were many of the ethnic German inhabitants of the Polish territory that separated the German exclave of East Prussia from the rest of the Reich.[28] The Polish Corridor constituted land long disputed by Poland and Germany, and was inhabited by a Polish majority. The Corridor had become a part of Poland after the Treaty of Versailles. Many Germans also wanted the urban port city of Danzig and its environs (comprising the Free City of Danzig) to be reincorporated into Germany. Danzig city had a German majority,[29] and had been separated from Germany after Versailles and made into the nominally independent Free City. Hitler sought to use this as casus belli, a reason for war, reverse the post-1918 territorial losses, and on many occasions had appealed to German nationalism, promising to "liberate" the German minority still in the Corridor, as well as Danzig.[30]

| Events leading to World War II |

|---|

The invasion was referred to by Germany as the 1939 Defensive War (Verteidigungskrieg) since Hitler proclaimed that Poland had attacked Germany and that "Germans in Poland are persecuted with a bloody terror and are driven from their homes. The series of border violations, which are unbearable to a great power, prove that the Poles no longer are willing to respect the German frontier."[31]

Poland participated with Germany in the partition of Czechoslovakia that followed the Munich Agreement, although they were not part of the agreement. It coerced Czechoslovakia to surrender the region of Český Těšín by issuing an ultimatum to that effect on 30 September 1938, which was accepted by Czechoslovakia on 1 October.[32] This region had a Polish majority and had been disputed between Czechoslovakia and Poland in the aftermath of World War I.[33][34] The Polish annexation of Slovak territory (several villages in the regions of Čadca, Orava and Spiš) later served as the justification for the Slovak state to join the German invasion.

By 1937, Germany began to increase its demands for Danzig, while proposing that an extraterritorial roadway, part of the Reichsautobahn system, be built in order to connect East Prussia with Germany proper, running through the Polish Corridor.[35] Poland rejected this proposal, fearing that after accepting these demands, it would become increasingly subject to the will of Germany and eventually lose its independence as the Czechs had.[36] Polish leaders also distrusted Hitler.[36] The British were also wary of Germany's increasing strength and assertiveness threatening its balance of power strategy.[37] On 31 March 1939, Poland formed a military alliance with the United Kingdom and with France, believing that Polish independence and territorial integrity would be defended with their support if it were to be threatened by Germany.[38] On the other hand, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, still hoped to strike a deal with Hitler regarding Danzig (and possibly the Polish Corridor). Chamberlain and his supporters believed war could be avoided and hoped Germany would agree to leave the rest of Poland alone. German hegemony over Central Europe was also at stake. In private, Hitler said in May that Danzig was not the important issue to him, but the creation of Lebensraum for Germany.[39]

Breakdown of talks

[edit]With tensions mounting, Germany turned to aggressive diplomacy. On 28 April 1939, Hitler unilaterally withdrew from both the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934 and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935. Talks over Danzig and the Corridor broke down, and months passed without diplomatic interaction between Germany and Poland. During this interim period, the Germans learned that France and Great Britain had failed to secure an alliance with the Soviet Union against Germany, and that the Soviet Union was interested in an alliance with Germany against Poland. Hitler had already issued orders to prepare for a possible "solution of the Polish problem by military means" through the Case White scenario.

In May, in a statement to his generals while they were in the midst of planning the invasion of Poland, Hitler made it clear that the invasion would not come without resistance as it had in Czechoslovakia:[40]

With minor exceptions German national unification has been achieved. Further successes cannot be achieved without bloodshed. Poland will always be on the side of our adversaries... Danzig is not the objective. It is a matter of expanding our living space in the east, of making our food supply secure, and solving the problem of the Baltic states. To provide sufficient food you must have sparsely settled areas. There is therefore no question of sparing Poland, and the decision remains to attack Poland at the first opportunity. We cannot expect a repetition of Czechoslovakia. There will be fighting.[40]

On 22 August, just over a week before the onset of war, Hitler delivered a speech to his military commanders at the Obersalzberg:

The object of the war is … physically to destroy the enemy. That is why I have prepared, for the moment only in the East, my 'Death's Head' formations with orders to kill without pity or mercy all men, women, and children of Polish descent or language. Only in this way can we obtain the living space we need.[16]

With the surprise signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on 24 August, the result of secret Nazi–Soviet talks held in Moscow, Germany neutralized the possibility of Soviet opposition to a campaign against Poland and war became imminent. In fact, the Soviets agreed not to aid France or the UK in the event of their going to war with Germany over Poland and, in a secret protocol of the pact, the Germans and the Soviets agreed to divide Eastern Europe, including Poland, into two spheres of influence; the western one-third of the country was to go to Germany and the eastern two-thirds to the Soviet Union.

The German assault was originally scheduled to begin at 4:00 a.m. on 26 August. However, on 25 August, the Polish-British Common Defence Pact was signed as an annex to the Franco-Polish alliance. In this accord, Britain committed itself to the defence of Poland, guaranteeing to preserve Polish independence. At the same time, the British and the Poles were hinting to Berlin that they were willing to resume discussions—not at all how Hitler hoped to frame the conflict. Thus, he wavered and postponed his attack until 1 September, managing to in effect halt the entire invasion "in mid-leap".

However, there was one exception: during the night of 25–26 August, a German sabotage group, which had not received orders to suspend action, attacked the Jablunkov Pass and Mosty railway station in Silesia. On the morning of 26 August, the group was repelled by Polish troops. The German side described all this as an incident "caused by an insane individual".[i]

On 26 August, Hitler tried to dissuade the British and the French from interfering in the upcoming conflict, even pledging that the Wehrmacht forces would be made available to Britain's empire in the future. The negotiations convinced Hitler that there was little chance the Western Allies would declare war on Germany, and even if they did, because of the lack of "territorial guarantees" to Poland, they would be willing to negotiate a compromise favourable to Germany after its conquest of Poland.

Meanwhile, the increased number of overflights by high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft and cross-border troop movements signaled to all observers that war was imminent.

On 29 August, prompted by the British, Germany issued one last diplomatic offer, with Fall Weiss yet to be rescheduled. That evening, the German government responded in a communication that it aimed not only for the restoration of Danzig but also the Polish Corridor (which had not previously been part of Hitler's demands) in addition to the safeguarding of the German minority in Poland. It said that they were willing to commence negotiations, but indicated that a Polish representative with the power to sign an agreement had to arrive in Berlin the next day while in the meantime Germany would draw up a set of proposals.[41] The British Cabinet was pleased that negotiations had been agreed, but, mindful of how Emil Hácha had been forced to sign his country away under similar circumstances just months earlier, regarded the requirement for the immediate arrival of a Polish representative with full signing powers as an unacceptable ultimatum.[42][43] On the night of 30/31 August, German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop read a 16-point German proposal to ambassador Nevile Henderson. When the ambassador requested a copy of the proposals for transmission to the Polish government, Ribbentrop refused, on the grounds that the requested Polish representative had failed to arrive by midnight.[44] When Polish Ambassador Lipski went to see Ribbentrop later, on 31 August, to indicate that Poland was favorably disposed to negotiations, he announced that he did not have the full power to sign an agreement, and Ribbentrop dismissed him. German radio then broadcast that Poland had rejected Germany's offer, and that, therefore, negotiations with Poland had come to an end. Hitler issued orders for the invasion to commence soon afterwards.

On 29 August, Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Józef Beck ordered military mobilization, but under pressure from Great Britain and France, the mobilization was cancelled. When the final mobilization started, it added to the confusion in the country.[45]

On 30 August, the Polish Navy sent its destroyer flotilla to Britain, executing the Peking Plan. On the same day, Marshal of Poland Edward Rydz-Śmigły announced the mobilization of Polish troops. However, he was pressured into revoking the order by the French, who apparently still hoped for a diplomatic settlement, failing to realize that the Germans were fully mobilized and concentrated at the Polish border.[46] During the night of 31 August, the Gleiwitz incident, a false flag attack on the radio station, was staged near the border city of Gleiwitz in Upper Silesia by German units posing as Polish troops, as part of the wider Operation Himmler.[47] On 31 August, Hitler ordered hostilities against Poland to start at 4:45 the next morning. However, partly because of the earlier stoppage, Poland finally managed to mobilize only about 70% of its planned forces (about 900,000 of 1,350,000 soldiers planned to mobilize in first order). Because of that, many units were still forming or moving to their designated frontline positions. The late mobilization reduced combat capability of the Polish Army by about 1/3.

On 31 August, Edward VIII, the Duke of Windsor, sent a message to Victor Emmanuel III, the King of Italy, asking for Italy to intervene and try to prevent Germany and Poland from going to war.[48]

Opposing forces

[edit]Germany

[edit]Germany had a substantial numeric advantage over Poland and had developed a significant military before the conflict. The Heer (army) had 3,472 tanks in its inventory, of which 2,859 were with the Field Army and 408 with the Replacement Army.[49] 453 tanks were assigned into four light divisions, while another 225 tanks were in detached regiments and companies.[50] Most notably, the Germans had seven Panzer divisions, with 2,009 tanks between them, using a new operational doctrine.[51] It held that these divisions should act in coordination with other elements of the military, punching holes in the enemy line and isolating selected units, which would be encircled and destroyed. This would be followed up by less-mobile mechanized infantry and foot soldiers. The Luftwaffe (air force) provided both tactical and strategic air power, particularly dive bombers that disrupted lines of supply and communications. Together, the new methods were nicknamed "Blitzkrieg" (lightning war). While historian Basil Liddell Hart claimed "Poland was a full demonstration of the Blitzkrieg theory",[52] some other historians disagree.[53]

Aircraft played a major role in the campaign. Bombers also attacked cities, causing huge losses amongst the civilian population through terror bombing and strafing. The Luftwaffe forces consisted of 1,180 fighters, 290 Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers, 1,100 conventional bombers (mainly Heinkel He 111s and Dornier Do 17s), and an assortment of 550 transport and 350 reconnaissance aircraft.[54][55] In total, Germany had close to 4,000 aircraft, most of them modern. A force of 2,315 aircraft was assigned to Weiss.[56] Due to its earlier participation in the Spanish Civil War, the Luftwaffe was probably the most experienced, best-trained and best-equipped air force in the world in 1939.[57]

Poland

[edit]

Emerging in 1918 as an independent country after 123 years of the Partitions of Poland, the Second Polish Republic, when compared with countries such as United Kingdom or Germany, was a relatively indigent and mostly agricultural country. The partitioning powers did not invest in the development of industry, especially in the armaments industry in ethnically Polish areas. Moreover, Poland had to deal with damage caused by World War I. This resulted in the need to build a defense industry from scratch. Between 1936 and 1939, Poland invested heavily in the newly created Central Industrial Region. Preparations for a defensive war with Germany were ongoing for many years, but most plans assumed fighting would not begin before 1942. To raise funds for industrial development, Poland sold much of the modern equipment it produced.[58] In 1936, a National Defence Fund was set up to collect funds necessary for strengthening the Polish Armed forces. The Polish Army had approximately a million soldiers, but not all were mobilized by 1 September. Latecomers sustained significant casualties when public transport became targets of the Luftwaffe. The Polish military had fewer armored forces than the Germans, and these units, dispersed within the infantry, were unable to effectively engage the Germans.[59]

Experiences in the Polish–Soviet War shaped Polish Army organizational and operational doctrine. Unlike the trench warfare of World War I, the Polish–Soviet War was a conflict in which the cavalry's mobility played a decisive role.[60] Poland acknowledged the benefits of mobility but was unable to invest heavily in many of the expensive, unproven inventions since then. In spite of this, Polish cavalry brigades were used as mobile mounted infantry and had some successes against both German infantry and cavalry.[61]

An average Polish infantry division consisted of 16,492 soldiers and was equipped with 326 light and medium machine guns, 132 heavy machine guns, 92 anti-tank rifles and several dozen light, medium, heavy, anti-tank and anti-airplane field artillery. Contrary to the 1,009 cars and trucks and 4,842 horses in the average German infantry division, the average Polish infantry division had 76 cars and trucks and 6,939 horses.[62]

The Polish Air Force (Lotnictwo Wojskowe) was at a severe disadvantage against the German Luftwaffe due to inferiority in numbers and the obsolescence of its fighter planes. However, contrary to German propaganda, it was not destroyed on the ground—in fact it was successfully dispersed before the conflict started and not a single one of its combat planes was destroyed on the ground in the first days of the conflict.[63] In the era of fast progress in aviation the Polish Air Force lacked modern fighters, vastly due to the cancellation of many advanced projects, such as the PZL.38 Wilk and a delay in the introduction of a completely new modern Polish fighter PZL.50 Jastrząb. However, its pilots were among the world's best trained, as proven a year later in the Battle of Britain, in which the Poles played a notable part.[64]

Overall, the Germans enjoyed numerical and qualitative aircraft superiority. Poland had only about 600 aircraft, of which only PZL.37 Łoś heavy bombers were modern and comparable to their German counterparts. The Polish Air Force had roughly 185 PZL P.11 and some 95 PZL P.7 fighters, 175 PZL.23 Karaś Bs, 35 Karaś as light bombers.[Note 5] However, for the September Campaign, not all of those aircraft were mobilized. By 1 September, out of about 120 heavy bombers PZL.37s produced, only 36 PZL.37s were deployed, the rest being mostly in training units. All those aircraft were of indigenous Polish design, with the bombers being more modern than the fighters, according to the Ludomił Rayski air force expansion plan, which relied on a strong bomber force. The Polish Air Force consisted of a 'Bomber Brigade', 'Pursuit Brigade' and aircraft assigned to the various ground armies.[66] The Polish fighters were older than their German counterparts; the PZL P.11 fighter—produced in the early 1930s—had a top speed of only 365 km/h (227 mph), far less than German bombers. To compensate, the pilots relied on its maneuverability and high diving speed.[57]

The Polish Air Force's decisions to strengthen its resources came too late, mostly due to budget limitations. As a "last minute" order in the summer of 1939, Poland bought 160 French Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 fighters and 111 English airplanes (100 light bombers Fairey Battle, 10 Hurricanes and 1 Supermarine Spitfire; the sale of 150 Spitfires asked by the Polish government was rejected by the Air Ministry).[67] Despite the fact that some of the airplanes had been shipped to Poland (the first transport of purchased aircraft on the ship "Lassel" sailed from Liverpool on 28 August[68]), none of them would take part in combat. In late 1938, the Polish Air Force also ordered 300 advanced PZL.46 Sum light bombers, but due to a delay in starting mass production, none of them were delivered before 1 September.[69] When in the spring of 1939 it turned out that there were problems with the implementation of the new PZL.50 Jastrząb fighter, it was decided to temporarily implement the production of the fighter PZL P 11.G Kobuz. Nevertheless, due to the outbreak of the war, not one of the ordered 90 aircraft of this type were delivered to the army.[70]

The tank force consisted of two armored brigades, four independent tank battalions and some 30 companies of TKS tankettes attached to infantry divisions and cavalry brigades.[71] A standard tank of the Polish Army during the invasion of 1939 was the 7TP light tank. It was the first tank in the world to be equipped with a diesel engine and 360° Gundlach periscope.[72] The 7TP was significantly better armed than its most common opponents, the German Panzer I and II, but only 140 tanks were produced between 1935 and the outbreak of the war. Poland had also a few relatively modern imported designs, such as 50 Renault R35 tanks and 38 Vickers E tanks.[citation needed]

The Polish Navy was a small fleet of destroyers, submarines and smaller support vessels. Most Polish surface units followed Operation Peking, leaving Polish ports on 20 August and escaping by way of the North Sea to join with the British Royal Navy. Submarine forces participated in Operation Worek, with the goal of engaging and damaging German shipping in the Baltic Sea, but they had much less success. In addition, many merchant marine ships joined the British merchant fleet and took part in wartime convoys.[citation needed]

Details

[edit]German plan

[edit]

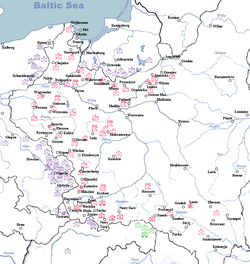

The September Campaign was devised by General Franz Halder, the chief of the general staff, and directed by General Walther von Brauchitsch the commander in chief of the German ground forces. It called for the start of hostilities before a declaration of war, and pursued a doctrine of mass encirclement and destruction of enemy forces. The infantry, far from completely mechanized but fitted with fast-moving artillery and logistic support, was to be supported by Panzers and small numbers of truck-mounted infantry (the Schützen regiments, forerunners of the panzergrenadiers) to assist the rapid movement of troops and concentrate on localized parts of the enemy front, eventually isolating segments of the enemy, surrounding, and destroying them. The prewar "armoured idea", which an American journalist in 1939 dubbed Blitzkrieg, which was advocated by some generals, including Heinz Guderian, would have had the armour punching holes in the enemy's front and ranging deep into rear areas, but the campaign in Poland would be fought along more traditional lines. That stemmed from conservatism on the part of the German High Command, which mainly restricted the role of armour and mechanized forces to supporting the conventional infantry divisions.[73]

Poland's terrain was well suited for mobile operations when the weather co-operated; the country had flat plains, with long frontiers totalling almost 5,600 km (3,500 mi). Poland's long border with Germany on the west and north, facing East Prussia, extended 2,000 km (1,200 mi). It had been lengthened by another 300 km (190 mi) on the southern side in the aftermath of the 1938 Munich Agreement. The German incorporation of Bohemia and Moravia and creation of the German puppet state of Slovakia meant that Poland's southern flank was also exposed.[74]

Hitler demanded that Poland be conquered in six weeks, but German planners thought that it would require three months.[75] They intended to exploit their long border fully with the great enveloping manoeuver of Fall Weiss. German units were to invade Poland from three directions:

- A main attack over the western Polish border, which was to be carried out by Army Group South, commanded by Colonel General Gerd von Rundstedt, attacking from German Silesia and from the Moravian and Slovak border. General Johannes Blaskowitz's 8th Army was to drive eastward against Łódź. General Wilhelm List's 14th Army was to push on toward Kraków and to turn the Poles' Carpathian flank. General Walter von Reichenau's 10th Army, in the centre with Army Group South's armour, was to deliver the decisive blow with a northeastward thrust into the heart of Poland.

- A second route of attack from northern Prussia. Colonel General Fedor von Bock commanded Army Group North, comprising General Georg von Küchler's 3rd Army, which was to strike southward from East Prussia, and General Günther von Kluge's 4th Army, which was to attack eastward across the base of the Polish Corridor.

- A tertiary attack by part of Army Group South's allied Slovak units from Slovakia.

- From within Poland, the German minority would assist by engaging in diversion and sabotage operations by Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz units that had been prepared before the war.[73]

All three assaults were to converge on Warsaw, and the main Polish army was to be encircled and destroyed west of the Vistula. Fall Weiss was initiated on 1 September 1939 and was the first operation of Second World War in Europe.

Polish defence plan

[edit]

The Polish determination to deploy forces directly at the German-Polish border, prompted by the Polish-British Common Defence Pact, shaped the country's defence plan, "Plan West". Poland's most valuable natural resources, industry and population were along the western border in Eastern Upper Silesia. Polish policy centred on their protection, especially since many politicians feared that if Poland retreated from the regions disputed by Germany, Britain and France would sign a separate peace treaty with Germany like the 1938 Munich Agreement and allow Germany to stay in those regions.[76] The fact that none of Poland's allies had specifically guaranteed Polish borders or territorial integrity was another Polish concern. These reasons made the Polish government disregard French advice to deploy the bulk of its forces behind natural barriers, such as the Vistula and San Rivers, despite some Polish generals supporting the idea to be a better strategy. The West Plan allowed the Polish armies to retreat inside the country, but that was supposed to be a slow retreat behind prepared positions intended to give the armed forces time to complete its mobilization and execute a general counteroffensive with the support of the Western Allies.[71]

In case of a failure to defend most of the territory, the army was to retreat to the south-east of the country, where the rough terrain, the Stryj and Dniestr rivers, valleys, hills and swamps would provide natural lines of defence against the German advance, and the Romanian Bridgehead could be created.

The Polish General Staff had not begun elaborating the "West" defence plan until 4 March 1939. It was assumed that the Polish Army, fighting in the initial phase of the war alone, would have to defend the western regions of the country. The plan of operations took into account the numerical and material superiority of the enemy and, also assumed the defensive character of Polish operations. The Polish intentions were defending the western regions that were judged as indispensable for waging the war, taking advantage of the propitious conditions for counterattacks by reserve units and avoiding it from being smashed before the beginning of Franco-British operations in Western Europe. The operation plan had not been elaborated in detail and concerned only the first stage of operations.[77]

The British and the French estimated that Poland would be able to defend itself for two to three months, and Poland estimated it could do so for at least six months. While Poland drafted its estimates based upon the expectation that the Western Allies would honor their treaty obligations and quickly start an offensive of their own, the French and the British expected the war to develop into trench warfare, much like World War I. The Polish government was not notified of the strategy and based all of its defence plans on promises of quick relief by the Western Allies.[78][79]

Polish forces were stretched thinly along the Polish-German border and lacked compact defence lines and good defence positions along disadvantageous terrain. That strategy also left supply lines poorly protected. One-third of Poland's forces were massed in or near the Polish Corridor, making them vulnerable to a double envelopment from East Prussia and the west. Another third was concentrated in the north-central part of the country, between the major cities of Łódź and Warsaw.[80] The forward positioning of Polish forces vastly increased the difficulty of carrying out strategic maneuvres, compounded by inadequate mobility, as Polish units often lacked the ability to retreat from their defensive positions, as they were being overrun by more mobile German mechanized formations.[81]

As the prospect of conflict increased, the British government pressed Marshal Edward Śmigły-Rydz to evacuate the most modern elements of the Polish Navy from the Baltic Sea.[82] In the event of war, the Polish military leaders realized that the ships that remained in the Baltic were likely to be quickly sunk by the Germans. Furthermore, since the Danish straits were well within operating range of the German Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe, there was little chance of an evacuation plan succeeding if it were implemented after hostilities began. Four days after the signing of the Polish-British Common Defence Pact, three destroyers of the Polish Navy executed the Peking Plan and so evacuated to Great Britain.[82]

Although the Polish military had prepared for conflict, the civilian population remained largely unprepared. Polish prewar propaganda emphasized that any German invasion would be easily repelled. That made Polish defeats during the German invasion come as a shock to the civilian population.[81] Lacking training for such a disaster, the civilian population panicked and retreated east, spreading chaos, lowering the troops' morale and making road transportation for Polish troops very difficult.[81] The propaganda also had some negative consequences for the Polish troops themselves, whose communications, disrupted by German mobile units operating in the rear and civilians blocking roads, were further thrown into chaos by bizarre reports from Polish radio stations and newspapers, which often reported imaginary victories and other military operations. That led to some Polish troops being encircled or taking a stand against overwhelming odds when they thought they were actually counterattacking or would soon receive reinforcements from other victorious areas.[81]

German invasion

[edit]

Following several German-staged incidents, such as the Gleiwitz incident, part of Operation Himmler, which German propaganda used as a pretext to claim that German forces were acting in self-defence, one of the first acts of war took place on 1 September 1939. At 04:45, the old German pre-dreadnought battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on the Polish military transit depot and coastal fort at Westerplatte, in the Free City of Danzig, on the Baltic Sea.[83] However, in many places, German units crossed the Polish border even before that time. Around then, the Luftwaffe attacked a number of military and civilian targets, including Wieluń, the first large-scale city bombing of the war. At 08:00, German troops, still without a formal declaration of war issued, attacked near the Polish village of Mokra. The Battle of the Border had begun. Later that day, the Germans attacked Poland's western, southern and northern borders, and German aircraft began raids on Polish cities. The main axis of attack led eastwards from Germany through the western Polish border. Supporting attacks came from East Prussia, in the north, and a joint German-Slovak tertiary attack by units (Field Army "Bernolák") from the German-allied Slovak Republic, in the south. All three assaults converged on the Polish capital, Warsaw.[84]

France and Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September, but failed to provide any meaningful support. The German-French border saw only a few minor skirmishes, and most German forces, including 85% of armoured forces, were engaged in Poland. Despite some Polish successes in minor border battles, the German technical, operational and numerical superiority forced the Polish armies to retreat from the borders towards Warsaw and Lwów. The Luftwaffe gained air superiority early in the campaign. By destroying communications, the Luftwaffe increased the pace of the advance which overran Polish airstrips and early warning sites, causing logistical problems for the Poles. Many Polish Air Force units ran low on supplies, and 98 of their number withdrew into neutral Romania.[85] The Polish initial strength of 400 was reduced to 54 by 14 September and air opposition virtually ceased,[85] with the main Polish air bases destroyed during the first 48 hours of the war.[86]

Germany attacked from three directions on land. Günther von Kluge led 20 divisions that entered the Polish Corridor and met a second force heading to Warsaw from East Prussia. Gerd von Rundstedt's 35 divisions attacked southern Poland.[86] By 3 September, when von Kluge in the north had reached the Vistula River, then some 10 km (6.2 mi) from the German border, and Georg von Küchler was approaching the Narew River, Walther von Reichenau's armour was already beyond the Warta river. Two days later, his left wing was well to the rear of Łódź and his right wing at the town of Kielce. On 7 September, the defenders of Warsaw had fallen back to a 48 km (30 mi) line paralleling the Vistula River, where they rallied against German tank thrusts. The defensive line ran between Płońsk and Pułtusk, respectively north-west and north-east of Warsaw.

The right wing of the Poles had been hammered back from Ciechanów, about 40 km (25 mi) north-west of Pułtusk, and was pivoting on Płońsk. At one stage, the Poles were driven from Pułtusk, and the Germans threatened to turn the Polish flank and thrust on to the Vistula and Warsaw. Pułtusk, however, was regained in the face of withering German fire. Many German tanks were captured after a German attack had pierced the line, but the Polish defenders outflanked them.[87] By 8 September, one of Reichenau's armoured corps, having advanced 225 km (140 mi) during the first week of the campaign, reached the outskirts of Warsaw. Light divisions on Reichenau's right were on the Vistula between Warsaw and the town of Sandomierz by 9 September, and List, in the south, was on the San River north and south of the town of Przemyśl. At the same time, Guderian led his 3rd Army tanks across the Narew, attacking the line of the Bug River that had already encircled Warsaw. All of the German armies made progress in fulfilling their parts of the plan. The Polish armies split up into uncoordinated fragments, some of which were retreating while others were launching disjointed attacks on the nearest German columns.

During this invasion, Hitler's troops made extensive use of Pervitin, a recently discovered methamphetamine, which enabled the constant movement of the troops, who no longer felt the need to sleep for several days. The drug would later also be used, this time officially distributed, in the invasions of France and the USSR.[88][89][90]

Polish forces abandoned the regions of Pomerelia (the Polish Corridor), Greater Poland and Polish Upper Silesia in the first week. The Polish plan for border defence was a dismal failure. The German advance, as a whole, was not slowed. On 10 September, the Polish commander-in-chief, Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły, ordered a general retreat to the south-east, towards the Romanian Bridgehead.[91] Meanwhile, the Germans were tightening their encirclement of the Polish forces west of the Vistula (in the Łódź area and, still farther west, around Poznań) and penetrating deeply into eastern Poland. Warsaw, which had undergone heavy aerial bombardment since the first hours of the war, was attacked on 9 September and was put under siege on 13 September. Around then, advanced German forces also reached Lwów, a major city in eastern Poland, and 1,150 German aircraft bombed Warsaw on 24 September.

The Polish defensive plan called for a strategy of encirclement. It would allow the Germans to advance in between two Polish Army groups in the line between Berlin and Warsaw-Lodz, and Armia Prusy would then move in and repulse the German spearhead, trapping it. For that to happen, Armia Prusy needed to be fully mobilized by 3 September. However, Polish military planners failed to foresee the speed of the German advance and assumed that Armia Prusy would need to be fully mobilized by 16 September.[92]

The largest battle during this campaign, the Battle of Bzura, took place near the Bzura River, west of Warsaw, and lasted from 9 to 19 September. The Polish armies Poznań and Pomorze, retreating from the border area of the Polish Corridor, attacked the flank of the advancing German 8th Army, but the counterattack failed despite initial success. After the defeat, Poland lost its ability to take the initiative and counterattack on a large scale. The German air power was instrumental during the battle. The offensive of the Luftwaffe broke what remained of the Polish resistance in an "awesome demonstration of air power".[93] The Luftwaffe quickly destroyed the bridges across the Bzura River. Then, the Polish forces were trapped out in the open and were attacked by wave after wave of Stukas, dropping 50 kg (110 lb) light bombs, which caused huge numbers of casualties. The Polish anti-aircraft batteries ran out of ammunition and retreated to the forests but were then smoked out by the Heinkel He 111 and Dornier Do 17s dropping 100 kg (220 lb) incendiaries. The Luftwaffe left the army with the task of mopping up survivors. The Stukageschwaders alone dropped 388 t (428 short tons) of bombs during the battle.[93]

By 12 September, all of Poland west of the Vistula had been conquered except for the isolated Warsaw.[86] The Polish government, led by President Ignacy Mościcki, and the high command, led by Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły, left Warsaw in the first days of the campaign and headed southeast, reaching Lublin on 6 September. From there, it moved on 9 September to Kremenez and, on 13 September to Zaleshiki, on the Romanian border.[94] Rydz-Śmigły ordered the Polish forces to retreat in the same direction, behind the Vistula and San Rivers, beginning the preparations for the defence of the Romanian Bridgehead area.[91]

Soviet invasion

[edit]

From the beginning, the German government repeatedly asked Molotov whether the Soviet Union would keep to its side of the partition bargain.[95][96] The Soviet forces were holding fast along their designated invasion points pending finalization of the five-month-long undeclared war with Japan in the Far East, successful end of the conflict for the Soviet Union, which occurred in the Battles of Khalkhin Gol. On 15 September 1939, Molotov and Shigenori Tōgō completed their agreement that ended the conflict, and the Nomonhan ceasefire went into effect on 16 September 1939. Now cleared of any "second front" threat from the Japanese, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin ordered his forces into Poland on 17 September.[97] It was agreed that the Soviets would relinquish its interest in the territories between the new border and Warsaw in exchange for inclusion of Lithuania in the Soviet "zone of interest".

By 17 September, the Polish defence had already been broken and the only hope was to retreat and reorganize along the Romanian Bridgehead. However, the plans were rendered obsolete nearly overnight when the over 800,000-strong Soviet Red Army entered and created the Belarusian and Ukrainian fronts after they had invaded the eastern regions of Poland, in violation of the Riga Peace Treaty, the Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact, and other international treaties, both bilateral and multilateral.[Note 6] Soviet diplomacy had lied that they were "protecting the Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities of eastern Poland since the Polish government had abandoned the country and the Polish state ceased to exist".[99]

The Polish border defence forces in the east, known as the Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza, had about 25 battalions. Rydz-Śmigły ordered them to fall back and not to engage the Soviets.[91] That, however, did not prevent some clashes and small battles, such as the Battle of Grodno, as soldiers and locals attempted to defend the city. The Soviets executed numerous Polish officers, including prisoners of war like General Józef Olszyna-Wilczyński.[100][101] The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists rose against the Poles, and communist partisans organized local revolts, robbing and killing civilians.[102] Those movements were quickly disciplined by the NKVD. The Soviet invasion was one of the decisive factors that convinced the Polish government that the war in Poland was lost.[103] Before the Soviet attack from the east, the Polish military's plan had called for long-term defence against Germany in south-eastern Poland and to await relief from an attack by the Western Allies on Germany's western border.[103] However, the Polish government refused to surrender or to negotiate peace with Germany. Instead, it ordered all units to evacuate Poland and to reorganize in France.

Meanwhile, Polish forces tried to move towards the Romanian Bridgehead area, still actively resisting the German invasion. From 17 to 20 September, Polish armies Kraków and Lublin were crippled at the Battle of Tomaszów Lubelski, the second-largest battle of the campaign. Lwów capitulated on 22 September because of the Soviet intervention; the city had been attacked by the Germans over a week earlier, and in the middle of the siege, the German troops handed operations over to their Soviet allies.[104] Despite a series of intensifying German attacks, Warsaw, defended by quickly-reorganized retreating units, civilian volunteers and militias, held out until 28 September. The Modlin Fortress north of Warsaw capitulated on 29 September, after an intense 16-day battle. Some isolated Polish garrisons managed to hold their positions long after they had been surrounded by German forces. The enclave of Westerplatte's tiny garrison capitulated on 7 September and the Oksywie garrison held until 19 September; the Hel Fortified Area was defended until 2 October.[105] In the last week of September, Hitler made a speech in Danzig and said:

Meantime, Russia felt moved, on its part, to march in for the protection of the interests of the White Russian and Ukrainian people in Poland. We realize now that in England and France this German and Russian co-operation is considered a terrible crime. An Englishman even wrote that it is perfidious—well, the English ought to know. I believe England thinks this co-operation perfidious because the co-operation of democratic England with bolshevist Russia failed, while National Socialist Germany's attempt with Soviet Russia succeeded. Poland never will rise again in the form of the Versailles treaty. That is guaranteed not only by Germany, but also guaranteed by Russia. – Adolf Hitler, 19 September 1939[106]

Despite a Polish victory at the Battle of Szack (the Soviets later executed all the officers and NCOs they had captured), the Red Army reached the line of rivers Narew, Bug, Vistula and San by 28 September, in many cases meeting German units advancing from the other direction. Polish defenders on the Hel Peninsula on the shore of the Baltic Sea held out until 2 October. The last operational unit of the Polish Army, General Franciszek Kleeberg's Samodzielna Grupa Operacyjna "Polesie", surrendered after the four-day Battle of Kock near Lublin on 6 October, marking the end of the September Campaign.[107]

Civilian deaths

[edit]The Polish Campaign was the first action by Hitler in his attempt to create Lebensraum (living space) for Germans. Nazi propaganda was one of the factors behind the German brutality directed at civilians that had worked relentlessly to convince the Germans into believing that Jews and Slavs were Untermenschen (subhumans).[108][109]

From the first day of invasion, the German air force (the Luftwaffe) attacked civilian targets and columns of refugees along the roads to terrorize the Polish people, disrupt communications and target Polish morale. The Luftwaffe killed 6,000 to 7,000 Polish civilians during the bombing of Warsaw.[110]

The German invasion saw atrocities committed against Polish men, women and children.[111] The German forces (both SS and the regular Wehrmacht) murdered tens of thousands of Polish civilians (such as the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler was notorious throughout the campaign for burning villages[112] and committing atrocities in numerous Polish towns, including massacres in Błonie, Złoczew, Bolesławiec, Torzeniec, Goworowo, Mława and Włocławek).[113]

Polish women and girls were raped en masse by the German invaders and then executed. In addition, large numbers of Polish women were routinely captured to force them into prostitution in German military brothels. Nazi raids in many Polish cities captured young women and girls, who were then forced to work in the brothels frequented by German officers and soldiers. Girls as young as 15 years old, who were classified as "fit for agricultural work in Germany", were sexually exploited by German soldiers at their destination.[114]

Altogether, the civilian losses of Polish population amounted to about 100,000[115] or between 150,000 and 200,000,[116] the large majority of which were due to German war operations and terror.[j] In Warsaw alone, 15,000 to 25,000 civilians lost their lives.[115] The deaths also included 12,136 Polish citizens of Polish and Jewish background killed in 615 known executions perpetrated by the German military, police and security forces before the close of the operations within the post-war borders of Poland.[115] In the German-occupied territories, a mass ethnic cleansing campaign called Operation Tannenberg was started in the course of the hostilities by the Wehrmacht and the Einsatzgruppen.[118] Roughly 1,250 German civilians were also killed during the invasion. (Also, 2,000 died fighting Polish troops as members of ethnic German militia forces such as the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz, which was a fifth column during the invasion.)[119]

The invasion of Poland marked the beginning of the Holocaust ("holocaust by bullets"), not only in its strict sense of the genocide of Jews, but also in its broader meaning of mass killings of various ethnic, political or social groups.[120]

Aftermath

[edit]

American journalist John Gunther wrote in December 1939 that "the German campaign was a masterpiece. Nothing quite like it has been seen in military history".[86] The country was divided between Germany and the Soviet Union. Slovakia gained back those territories taken by Poland in autumn 1938. Lithuania received the city of Vilnius and its environs on 28 October 1939 from the Soviet Union. On 8 and 13 September 1939, the German military district in the area of Posen, commanded by general Alfred von Vollard-Bockelberg, and West Prussia, commanded by general Walter Heitz, were established in conquered Greater Poland and Pomerelia, respectively.[121] Based on laws of 21 May 1935 and 1 June 1938, the German military delegated civil administrative powers to Chiefs of Civil Administration (CdZ).[121] Hitler appointed Arthur Greiser to become the CdZ of the Posen military district, and Danzig's Gauleiter Albert Forster to become the CdZ of the West Prussian military district.[121] On 3 October 1939, the military districts centered on and named "Lodz" and "Krakau" were set up under command of major generals Gerd von Rundstedt and Wilhelm List, and Hitler appointed Hans Frank and Arthur Seyß-Inquart as civil heads, respectively.[121] Thus the entirety of occupied Poland was divided into four military districts (West Prussia, Posen, Lodz, and Krakau).[122] Frank was at the same time appointed "supreme chief administrator" for all occupied territories.[121] On 28 September, another secret German–Soviet protocol modified the arrangements of August: all of Lithuania was shifted to the Soviet sphere of influence; in exchange, the dividing line in Poland was moved in Germany's favour, eastwards towards the Bug River. On 8 October, Germany formally annexed the western parts of Poland with Greiser and Forster as Reichsstatthalter, while the south-central parts were administered as the General Government led by Frank.

Even though water barriers separated most of the spheres of interest, the Soviet and German troops met on numerous occasions. The most remarkable event of this kind occurred at Brest-Litovsk on 22 September. The German 19th Panzer Corps—commanded by General Heinz Guderian—had occupied the city, which lay within the Soviet sphere of interest. When the Soviet 29th Tank Brigade (commanded by Semyon Krivoshein) approached, the commanders agreed that the German troops would withdraw and the Soviet troops would enter the city, saluting each other.[123] At Brest-Litovsk, Soviet and German commanders held a joint victory parade before German forces withdrew westward behind a new demarcation line.[20][124] Just three days earlier, however, the parties had a more hostile encounter near Lwów, when the German 137th Gebirgsjägerregimenter (mountain infantry regiment) attacked a reconnaissance detachment of the Soviet 24th Tank Brigade; after a few casualties on both sides, the parties turned to negotiations. The German troops left the area, and the Red Army troops entered Lwów on 22 September.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop pact and the invasion of Poland marked the beginning of a period during which the government of the Soviet Union increasingly tried to convince itself that the actions of Germany were reasonable, and were not developments to be worried about, despite evidence to the contrary.[125] On 7 September 1939, just a few days after France and Britain joined the war against Germany, Stalin explained to a colleague that the war was to the advantage of the Soviet Union, as follows:[126]

A war is on between two groups of capitalist countries ... for the redivision of the world, for the domination of the world! We see nothing wrong in their having a good hard fight and weakening each other ... Hitler, without understanding it or desiring it, is shaking and undermining the capitalist system ... We can manoeuvre, pit one side against the other to set them fighting with each other as fiercely as possible ... The annihilation of Poland would mean one fewer bourgeois fascist state to contend with! What would be the harm if as a result of the rout of Poland we were to extend the socialist system onto new territories and populations?[126]

About 65,000 Polish troops were killed in the fighting (and roughly 3,000 prisoners of war were executed[127][128]: 121 ), with 420,000 others being captured by the Germans and 240,000 more by the Soviets (for a total of 660,000 prisoners). Up to 120,000 Polish troops escaped to neutral Romania (through the Romanian Bridgehead and Hungary), and another 20,000 to Latvia and Lithuania, with the majority eventually making their way to France or Britain. Most of the Polish Navy succeeded in evacuating to Britain as well. German personnel losses were less than their enemies (c. 16,000 killed).

None of the parties to the conflict—Germany, the Western Allies or the Soviet Union—expected that the German invasion of Poland would lead to a war that would surpass World War I in its scale and cost.[citation needed] It would be months before Hitler would see the futility of his peace negotiation attempts with the United Kingdom and France, but the culmination of combined European and Pacific conflicts would result in what was truly a "world war". Thus, what was not seen by most politicians and generals in 1939 is clear from the historical perspective: The Polish September Campaign marked the beginning of a pan-European war, which combined with the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the Pacific War in 1941 to form the global conflict known as World War II.

The invasion of Poland led Britain and France to declare war on Germany on 3 September. However, they did little to affect the outcome of the September Campaign. No declaration of war was issued by Britain and France against the Soviet Union. This lack of direct help led many Poles to believe that they had been betrayed by their Western allies. British Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax said they were only obligated to declare war on Germany due to the first clause of the Anglo-Polish Agreement in 1939.[129]

The different attitude of the Anglo-French allies of Poland towards Nazi Germany and the USSR was argued at this time, for example, by the future head of the British government, Churchill:

Russians were guilty of gross treachery during the recent negotiations, but Marshal Voroshilov's demand that the Russian armies, if they were allies of Poland, should occupy Vilnius and Lvov was a perfectly reasonable military demand. It was rejected by Poland, whose arguments, despite their naturalness, cannot be considered satisfactory in the light of current events. As a result, Russia took up the same positions as an enemy of Poland that it might have taken as a very dubious and suspected friend. The difference is actually not as great as it might seem. The Russians mobilized a very large force and showed that they were able to move quickly and far from their pre-war positions. They now border on Germany, and the latter is completely unable to expose the Eastern front. A large German army will have to be left behind to monitor it. As far as I know, General Hamelin estimates its strength at least 20 divisions, but there may well be 25 or even more. Therefore, the Eastern front potentially exists.[130]

Russia is pursuing a cold policy of its own interests. We would prefer that the Russian armies stand in their present positions as friends and allies of Poland, rather than as invaders. But to protect Russia from the Nazi threat, it was clearly necessary that Russian armies should stand on this line. In any case, this line exists and, consequently, the Eastern front has been created, which Nazi Germany will not dare to attack...[130]

On 23 May 1939, Hitler explained to his officers that the object of the aggression was not Danzig, but the need to obtain German Lebensraum and details of this concept would be later formulated in the infamous Generalplan Ost.[131][132] The invasion decimated urban residential areas, civilians soon became indistinguishable from combatants, and the forthcoming German occupation (both on the annexed territories and in the General Government) was one of the most brutal episodes of World War II, resulting in between 5.47 million and 5.67 million Polish deaths[133] (about one-sixth of the country's total population, and over 90% of its Jewish minority)—including the mass murder of 3 million Polish citizens (mainly Jews as part of the final solution) in extermination camps like Auschwitz, in concentration camps, and in numerous ad hoc massacres, where civilians were rounded up, taken to a nearby forest, machine-gunned, and then buried, whether they were dead or not.[134] Among the 100,000 people murdered in the Intelligenzaktion operations in 1939–1940, approximately 61,000 were members of the Polish intelligentsia: scholars, clergy, former officers, and others, whom the Germans identified as political targets in the Special Prosecution Book-Poland, compiled before the war began in September 1939.[135]

According to the Polish Institute of National Remembrance, Soviet occupation between 1939 and 1941 resulted in the death of 150,000 and deportation of 320,000 of Polish citizens,[133][136] when all who were deemed dangerous to the Soviet regime were subject to Sovietization, forced resettlement, imprisonment in labor camps (the Gulags) or murdered, like the Polish officers in the Katyn massacre.[a]

Since October 1939, the Polish army that could escape imprisonment from the Soviets or Nazis were mainly heading for British and French territories. These places were considered safe, because of the pre-war alliance between Great-Britain, France and Poland. Not only did the government escape, but also the national gold supply was evacuated via Romania and brought to the West, notably London and Ottawa.[137][138] The approximately 75 tonnes (83 short tons) of gold was considered sufficient to field an army for the duration of the war.[139]

Eyewitness accounts

[edit]From Lemberg to Bordeaux ('Von Lemberg bis Bordeaux'), written by Leo Leixner, a journalist and war correspondent, is a first-hand account of the battles that led to the falls of Poland, the Low Countries, and France. It includes a rare eyewitness description of the Battle of Węgierska Górka. In August 1939, Leixner joined the Wehrmacht as a war reporter, was promoted to sergeant and, in 1941, published his recollections. The book was originally issued by Franz Eher Nachfolger, the central publishing house of the Nazi Party.[140]

The American journalist and filmmaker Julien Bryan came to besieged Warsaw on 7 September 1939 in the time of German bombardment. He photographed the beginning of the war by using one roll of colour film (Kodachrome) and much black-and-white film. He made one film about German crimes against civilians during the invasion. In colour, he photographed Polish soldiers, fleeing civilians, bombed houses, and a German bomber He 111 destroyed by the Polish Army in Warsaw. His photographs and film Siege are stored in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[141]

Misconceptions

[edit]Combat between Polish cavalry and German tanks

[edit]

Polish cavalry units did not engage German tanks with lances and swords. At the Battle of Tuchola Forest on 1 September 1939 the 18th Pomeranian Uhlan Regiment had been tasked to cover the retreat of Polish infantry. In the evening the Pomeranian Uhlans encountered contingents of the advancing German 20th Infantry Division of Heinz Guderian's XIX Army Corps. Commander Kazimierz Mastalerz ordered an attack, forcing the 20th infantry to withdraw and disperse. The engagement proved to be successful as the German advance had been delayed. However, upon redeployment, the 18th Pomeranians came under sudden and intense machine gun fire of German armored reconnaissance vehicles. Despite their quick retreat, nearly a third of the Uhlans were killed or wounded.[142]

A group of German and Italian war correspondents, who visited the battlefield noticed the dead cavalry men and horses among the armored vehicles. Italian reporter Indro Montanelli promptly published an article in the Corriere della Sera, on the brave and heroic Polish cavalry men, who charged German tanks with sabres and lances.

Historian Steven Zaloga in Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg (2004):

If a single image dominates the popular perception of the Polish campaign of 1939, it is the scene of Polish cavalry bravely charging the Panzers with their lances. Like many other details of the campaign, it is a myth that was created by German wartime propaganda and perpetuated by sloppy scholarship. Yet such myths have also been embraced by the Poles themselves as symbols of their wartime gallantry, achieving a cultural resonance in spite of their variance with the historical record.[143]

In 1939, 10% of the Polish army was made up of cavalry units.[144]

Polish Air Force

[edit]The Polish Air Force was not destroyed on the ground in the first days of the war. Though numerically inferior, it had been redeployed from major air bases to small camouflaged airfields shortly before the war. Only some trainers and auxiliary aircraft were destroyed on the ground. The Polish Air Force, despite being significantly outnumbered and with its fighters outmatched by more advanced German fighters, remained active until the second week of the campaign, inflicting significant damage on the Luftwaffe.[145] The Luftwaffe lost 285 aircraft to all operational causes, with 279 more damaged, and the Poles lost 333 aircraft.[146]

Polish resistance to the invasion

[edit]

Another question concerns whether Poland inflicted any significant losses on the German forces and whether it surrendered too quickly. While exact estimates vary, Poland cost the Germans about 45,000 casualties and 11,000 damaged or destroyed military vehicles, including 993 tanks and armored cars, 565 to 697 airplanes and 370 artillery pieces.[147][148][149] As for duration, the September Campaign lasted about a week and a half less than the Battle of France in 1940 even though the Anglo-French forces were much closer to parity with the Germans in numerical strength and equipment and were supported by the Maginot line.[Note 7] Furthermore, the Polish Army was preparing the Romanian Bridgehead, which would have prolonged Polish defence, but the plan was invalidated by the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939.[150]

Poland also never officially surrendered to the Germans. Under German occupation, there was continued resistance by forces such as the Armia Krajowa, Henryk Dobrzański's guerrillas, and the Leśni ("forest partisans").

First use of Blitzkrieg strategy

[edit]It is often assumed that Blitzkrieg is the strategy that Germany first used in Poland. Many early post-war histories, such as Barrie Pitt's in The Second World War (BPC Publishing 1966), attribute German victory to "enormous development in military technique which occurred between 1918 and 1940", and cite that "Germany, who translated (British inter-war) theories into action... called the result Blitzkrieg". That idea has been repudiated by some authors. Matthew Cooper writes:

Throughout the Polish Campaign, the employment of the mechanized units revealed the idea that they were intended solely to ease the advance and to support the activities of the infantry.... Thus, any strategic exploitation of the armoured idea was still-born. The paralysis of command and the breakdown of morale were not made the ultimate aim of the ... German ground and air forces, and were only incidental by-products of the traditional manoeuvers of rapid encirclement and of the supporting activities of the flying artillery of the Luftwaffe, both of which had as their purpose the physical destruction of the enemy troops. Such was the Vernichtungsgedanke of the Polish campaign. – Cooper[151]

Vernichtungsgedanke was a strategy dating back to Frederick the Great, and it was applied in the Polish Campaign, little changed from the French campaigns in 1870 or 1914. According to Cooper, the use of tanks "left much to be desired... Fear of enemy action against the flanks of the advance, fear which was to prove so disastrous to German prospects in the west in 1940 and in the Soviet Union in 1941, was present from the beginning of the war."[53]

John Ellis, writing in Brute Force, asserted that, "there is considerable justice in Matthew Cooper's assertion that the panzer divisions were not given the kind of strategic mission that was to characterize authentic armoured blitzkrieg, and were almost always closely subordinated to the various mass infantry armies".[152] (emphasis in original)

Zaloga and Madej, in The Polish Campaign 1939, also address the subject of mythical interpretations of Blitzkrieg and the importance of other arms in the campaign. They argue that Western accounts of the September campaign have stressed the shock value of the panzers and Stuka attacks have "tended to underestimate the punishing effect of German artillery on Polish units. Mobile and available in significant quantity, artillery shattered as many units as any other branch of the Wehrmacht."[153]

See also

[edit]- Gestapo–NKVD conferences

- List of Polish divisions in World War II

- Occupation of Poland (1939–1945)

- Phoney War

- Polish contribution to World War II

- Polish resistance movement in World War II

- The Black Book of Poland

- Timeline of the invasion of Poland

- Western betrayal

- German crimes during the September Campaign

Notes

[edit]- ^ See: Slovak invasion of Poland

- ^ From 17 September

- ^ Separated from 12th Army on 28 September

- ^ a b Improvised during the invasion

- ^ German: Überfall auf Polen 1939; Russian: вторжение в Польшу, transcription: vtorshenie v Polshshu; Slovak: invázia do Poľska

- ^ Polish: kampania wrześniowa

- ^ Polish: kampania polska; German: Polenfeldzug; also known as Polish Campaign of the Second World War (Polish: kampania polska drugiej wojny światowej)

- ^ Polish: wojna obronna 1939 roku

- ^ See Jabłonków incident.

- ^ Approximately 90% of Polish casualties during the entire World War II are attributed to Nazi Germany, and the total Polish wartime deaths inflicted by the Soviets, including the repressions that followed the occupation, are estimated not to have exceeded 100,000.[117]

- ^ Various sources contradict each other so the figures quoted above should only be taken as a rough indication of the strength estimate. The most common range differences and their brackets are: Polish personnel 1,490,900 (official figure of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs)—or 1,800,000. Polish tanks: 100–880, 100 is the number of modern tanks, while the 880 number includes older tanks from the World War I era and tankettes.[3][4]

- ^ The discrepancy in German casualties can be attributed to the fact that some German statistics still listed soldiers as missing decades after the war. Today the most common and accepted numbers are: 8,082 to 16,343 KIA, 320 to 5,029 MIA, 27,280 to 34,136 WIA.[6] For comparison, in his 1939 speech following the Polish campaign, Adolf Hitler presented these German figures: 10,576 KIA, 30,222 WIA, and 3,400 MIA.[7] According to early Allied estimates, including those of the Polish government-in-exile, the number of German KIA casualties was 90,000 and WIA casualties was 200,000[7][8] Equipment losses are given as 832 German tanks[9] with approximately 236[9] to 341 as irrecoverable losses and approximately 319 other armored vehicles as irrecoverable losses (including 165 Panzerspähwagen – of them 101 as irrecoverable losses)[9] 522–561 German planes (including 246–285 destroyed and 276 damaged), 1 German minelayer (M-85) and 1 German torpedo ship ("Tiger")

- ^ Soviet official losses – figures provided by Krivosheev – are currently estimated at 1,475 KIA or MIA presumed dead (Ukrainian Front – 972, Belorussian Front – 503), and 2,383 WIA (Ukrainian Front – 1,741, Belorussian Front – 642). The Soviets lost approximately 150 tanks in combat of which 43 as irrecoverable losses, while hundreds more suffered technical failures.[11] However, Russian historian Igor Bunich estimates Soviet manpower losses at 5,327 KIA or MIA without a trace and WIA.[12]

- ^ Various sources contradict each other so the figures quoted above should only be taken as a rough indication of losses. The most common range brackets for casualties are: Poland: 63,000 to 66,300 KIA, 134,000 WIA.[6] The often cited figure of 420,000 Polish prisoners of war represents only those captured by the Germans, as Soviets captured about 250,000 Polish POWs themselves, making the total number of Polish POWs about 660,000–690,000. In terms of equipment the Polish Navy lost one destroyer (ORP Wicher), one minelayer (ORP Gryf) and several support craft. Equipment loses included 132 Polish tanks and armored cars 327 Polish planes (118 fighters)[9]

- ^ P-11c (+43 reserve), 30 P-7 (+85 reserve), 118 P-23 Karaś light bombers, 36 P-37 Łoś bombers (armed in line, additionally a few of the total number produced were used in combat), 84 reconnaissance RXIII Lublin, RWD14 Czapla (+115 reserve)[65]

- ^ Other treaties violated by the Soviet Union were the 1919 Covenant of the League of Nations (to which the Soviet Union adhered in 1934); the Briand-Kellogg Pact of 1928 and the 1933 London Convention on the Definition of Aggression.[98]

- ^ Polish to German forces in the September Campaign: 1,000,000 soldiers, 4,300 guns, 880 tanks, 435 aircraft (Poland) to 1,800,000 soldiers, 10,000 guns, 2,800 tanks, 3,000 aircraft (Germany). French and participating Allies to German forces in the Battle of France: 2,862,000 soldiers, 13,974 guns, 3,384 tanks, 3,099 aircraft 2 (Allies) to 3,350,000 soldiers, 7,378 guns, 2,445 tanks, 5,446 aircraft (Germany).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The 1939 Campaign Archived 11 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2005.

- ^ ER Hooton, p. 85

- ^ Internetowa encyklopedia PWN, article on 'Kampania Wrześniowa 1939'

- ^ Website of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs – the Poles on the Front Lines

- ^ a b c (in Russian) Переслегин. Вторая мировая: война между реальностями.– М.:Яуза, Эксмо, 2006, с.22; Р. Э. Дюпюи, Т. Н. Дюпюи. Всемирная история войн. – С-П,М: АСТ, кн.4, с.93.

- ^ a b Wojna obronna Polski 1939, ed. Eugeniusz Kozłowski, Warszawa 1979, p. 851

- ^ a b "Polish War, German Losses". The Canberra Times. 13 October 1939. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ "Nazi Loss in Poland Placed at 290,000". The New York Times. 1941. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d Kamil Cywinski, Waffen und Geheimwaffen des deutschen Heeres 1933–1945

- ^ "Axis Slovakia: Hitler's Slavic Wedge, 1938–1945", p. 81

- ^ a b Кривошеев Г. Ф., Россия и СССР в войнах XX века: потери вооруженных сил. Статистическое исследование (Krivosheev G.F., Russia and the USSR in the wars of the 20th century: losses of the Armed Forces. A Statistical Study Greenhill 1997 ISBN 1853672807) (in Russian)

- ^ a b Bunich, Igor (1994). Operatsiia Groza, Ili, Oshibka V Tretem Znake: Istoricheskaia Khronika. Vita-Oblik. p. 88. ISBN 978-5859760039.

- ^ Czesław Grzelak, Henryk Stańczyk: Kampania polska 1939 roku. Początek II wojny światowej. Warsaw Oficyna Wydawnicza Rytm, 2005, p. 5, 385. ISBN 83-7399-169-7. (in Polish)

- ^ "German-Soviet Pact". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

...paved the way for the joint invasion and occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that September.

- ^ Collier, Martin, and Pedley, Philip Germany 1919–45 (2000) p. 146

- ^ a b Piotrowski (1998), p. 115.

- ^ Gushee, David P. (2013). The Sacredness of Human Life. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. pp. 313–315. ISBN 978-0-8028-4420-0.

- ^ Moor-Jankowski, Jan (5 August 2019). "Holocaust of non-jewish Poles during WWII". Archived from the original on 5 August 2019.

- ^ Dariusz Baliszewski (19 September 2004), Most honoru. Tygodnik Wprost (weekly), 38/2004. ISSN 0209-1747.

- ^ a b Kitchen, Martin (1990). A World in Flames: A Short History of the Second World War. Longman. p. 74. ISBN 978-0582034082. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Sanford (2005), pp. 20–24.

- ^ "The Nazification of Germany". University of South Florida. 2005.

- ^ Kimmich, Christoph M. (1 January 1969). "The Weimar Republic and the German-Polish Borders". The Polish Review. 14 (4): 37–45. JSTOR 25776872.

- ^ Majer, Diemut (2003). "Non-Germans" under the Third Reich: the Nazi judicial and administrative system in Germany and occupied Eastern Europe with special regard to occupied Poland, 1939–1945. JHU Press. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0801864933.

- ^ a b Rothwell, Victor (2001). Origins of the Second World War. Manchester University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0719059582.

- ^ a b Crozier, Andrew J. (1997). The causes of the Second World War. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0631186014..

- ^ A ridiculous hundred million Slavs : concerning Adolf Hitler's world-view, Tadeusz Manteuffel Institute of History Polish Academy of Sciences, Jerzy Wojciech Borejsza p. 49, Warsaw 2017

- ^ The Second World War: Volume 2 Europe 1939–1943, Tom 2 Robin Havers p. 25

- ^ Ergebnisse der Volks- und Berufszählung Vom 1. November 1923 in der Freien Stadt Danzig mit einem Anhang: Die Ergebnisse der Volkszählung vom 31. August 1924. Verlag des Statistischen Landesamtes der freien Stadt Danzig. 1926..

- ^ Snyder, Louis Leo; Montgomery, John D (2003). The new nationalism. Transaction Publishers. p. 88. ISBN 978-0765805508..

- ^ "German Army Attacks Poland; CitiesBombed, Port Blockaded; Danzig Is AcceptedInto Reich". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ Nowa Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN 1997, vol. VI, 981.

- ^ Zahradnik "Korzenie Zaolzia. Warszawa – Praga – Trzyniec", 16–17.

- ^ Gawrecká "Československé Slezsko. Mezi světovými válkami 1918–1938", Opava 2004, 21.

- ^ "Elbing-Königsberg Autobahn". Euronet.nl. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ a b "The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy". Yale. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ "World History in Context – Document".

- ^ Indiana University. "Chronology 1939". League of Nations Archives, Palais des Nations. Geneva: indiana.edu. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ A World at Total War: Global Conflict and the Politics of Destruction, 1937–1945, Roger Chickering, Stig Förster, Bernd Greiner, p. 97

- ^ a b Clark, Lloyd, Kursk: The Greatest Battle: Eastern Front 1943, 2011, p. 26

- ^ Reply of the German Chancellor to the Communication of 28 August 1939, from His Majesty's Government Cited in the British Blue Book

- ^ Viscount Halifax to Sir N. Henderson (Berlin) Cited in the British Blue book

- ^ Sir H. Kennard to Viscount Halifax (received 10 a.m.). Cited in the British Blue Book

- ^ Sir N. Henderson to Viscount Halifax (received 9:30 a.m. 31 August) Cited in the British Blue Book

- ^ Oslon and Cloud,"A Question of Honor" p. 50

- ^ Seidner, Stanley S. Marshal Edward Śmigły-Rydz Rydz and the defence of Poland, New York, 1978, ch. 2

- ^ Roger Manvell, Heinrich Fraenkel, Heinrich Himmler: The SS, Gestapo, His Life and Career, Skyhorse Publishing Inc., 2007, ISBN 1602391785, Google Books, p. 76

- ^ "Duke of Windsor Begs Italy's King to Intervene" (PDF). The New York Times. 88 (29804): 1. 31 August 1939. Retrieved 28 June 2025.

- ^ Jentz (1996), p. 88.

- ^ Jentz (1996), p. 91.

- ^ Jentz (1996), pp. 90–91.

- ^ B.H. Hart & A.J.P. Taylor, p. 41

- ^ a b Matthew Cooper, The German Army 1939–1945: Its Political and Military Failure

- ^ Bombers of the Luftwaffe, Joachim Dressel and Manfred Griehl, Arms and Armour, 1994

- ^ The Flying pencil, Heinz J. Nowarra, Schiffer Publishing, 1990, p. 25

- ^ A History of World War Two, A.J.P. Taylor, Octopus, 1974, p. 35

- ^ a b Seidner (1978), p. 162.

- ^ Seidner (1978), p. 177.

- ^ Seidner (1978), p. 270.

- ^ Seidner (1978), p. 135.

- ^ Seidner (1978), p. 158.

- ^ Zawadzki, Tadeusz (2009). "Porównanie sił". Polityka (3): 112.

- ^ Michael Alfred Peszke, Poland's Preparation for World War II, Military Affairs 43 (Feb 1979): 18–24

- ^ Michael Alfred Peszke, Polish Underground Army, the Western Allies, and the Failure of Strategic Unity in World War II, McFarland & Company, 2004, ISBN 078642009X, Google Print, p. 2

- ^ Adam Kurowski 'Lotnictwo Polskie 1939' 129

- ^ 'Duel for the Sky' by Christopher Shores