Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Halakha

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

Halakha (/hɑːˈlɔːxə/ hah-LAW-khə;[1] Hebrew: הֲלָכָה, romanized: hălāḵā, Sephardic: [halaˈχa]), also transliterated as halacha, halakhah, and halocho (Ashkenazic: [haˈlɔχɔ]), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandments (mitzvot), subsequent Talmudic and rabbinic laws, and the customs and traditions which were compiled in the many books such as the Shulchan Aruch or Mishneh Torah. Halakha is often translated as "Jewish law", although a more literal translation might be "the way to go" or "the way of walking". The word is derived from the root ה–ל–כ, which refers to concepts related to "to go", "to walk". Halakha not only guides religious practices and beliefs; it also guides numerous aspects of day-to-day life.[2]

Historically, widespread observance of the laws of the Torah is first in evidence beginning in the second century BCE, and some say that the first evidence was even earlier. [3] In the Jewish diaspora, halakha served many Jewish communities as an enforceable avenue of law — both civil and religious, since no differentiation of them exists in classical Judaism. Since the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) and Jewish emancipation, some have come to view the halakha as less binding in day-to-day life, because it relies on rabbinic interpretation, as opposed to the authoritative, canonical text which is recorded in the Hebrew Bible. Under contemporary Israeli law, certain areas of Israeli family and personal status law are, for Jews, under the authority of the rabbinic courts, so they are treated according to halakha. Some minor differences in halakha are found among Ashkenazi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, Sephardi Jews, Yemenite, Ethiopian and other Jewish communities which historically lived in isolation.[4]

Etymology and terminology

[edit]

The word halakha is derived from the Hebrew root halakh – "to walk" or "to go".[5]: 252 Taken literally, therefore, halakha translates as "the way to walk", rather than "law". The word halakha refers to the corpus of rabbinic legal texts, or to the overall system of religious law. The term may also be related to Akkadian ilku, a property tax, rendered in Aramaic as halakh, designating one or several obligations.[6] It may be descended from hypothetical reconstructed Proto-Semitic root *halakh- meaning "to go", which also has descendants in Akkadian, Arabic, Aramaic, and Ugaritic.[7]

Halakha is often contrasted with aggadah ("the telling"), the diverse corpus of rabbinic exegetical, narrative, philosophical, mystical, and other "non-legal" texts.[6] At the same time, since writers of halakha may draw upon the aggadic and even mystical literature, a dynamic interchange occurs between the genres. Halakha also does not include the parts of the Torah not related to commandments.

Halakha constitutes the practical application of the 613 mitzvot ("commandments") in the Torah, as developed through discussion and debate in the classical rabbinic literature, especially the Mishnah and the Talmud (the "Oral Torah"), and as codified in the Mishneh Torah and Shulchan Aruch.[8] Because halakha is developed and applied by various halakhic authorities rather than one sole "official voice", different individuals and communities may well have different answers to halakhic questions. With few exceptions, controversies are not settled through authoritative structures because during the Jewish diaspora, Jews lacked a single judicial hierarchy or appellate review process for halakha.

According to some scholars, the words halakha and sharia both mean literally "the path to follow". The fiqh literature parallels rabbinical law developed in the Talmud, with fatwas being analogous to rabbinic responsa.[9][10]

Commandments (mitzvot)

[edit]According to the Talmud (Tractate Makot), 613 mitzvot are in the Torah, 248 positive ("thou shalt") mitzvot and 365 negative ("thou shalt not") mitzvot, supplemented by seven mitzvot legislated by the rabbis of antiquity.[11] Currently, many of the 613 commandments cannot be performed until the building of the Temple in Jerusalem and the universal resettlement of the Jewish people in the Land of Israel by the Messiah. According to one count, only 369 can be kept, meaning that 40% of mitzvot are not possible to perform. Of these 369, 77 of these are positive mitzvot and 194 are negative.[12]

Rabbinic Judaism divides laws into categories:[13][14]

- The Law of Moses which are believed to have been revealed by God to the Israelites at biblical Mount Sinai. These laws are composed of the following:

- The Written Torah, laws written in the Hebrew Bible.

- The Oral Torah, laws believed to have been transmitted orally prior to their later compilation in texts such as the Mishnah, Talmud, and rabbinic codes.

- Laws of human origin, including rabbinic decrees, interpretations, customs, etc.

This division between revealed and rabbinic commandments may influence the importance of a rule, its enforcement and the nature of its ongoing interpretation.[13] Halakhic authorities may disagree on which laws fall into which categories or the circumstances (if any) under which prior rabbinic rulings can be re-examined by contemporary rabbis, but all Halakhic Jews hold that both categories exist[citation needed] and that the first category is immutable, with exceptions only for life-saving and similar emergency circumstances.

A second classical distinction is between the Written Law, laws written in the Hebrew Bible, and the Oral Law, laws which are believed to have been transmitted orally prior to their later compilation in texts such as the Mishnah, Talmud, and rabbinic codes.

Commandments are divided into positive and negative commands, which are treated differently in terms of divine and human punishment. Positive commandments require an action to be performed and are considered to bring the performer closer to God. Negative commandments (traditionally 365 in number) forbid a specific action, and violations create a distance from God.

A further division is made between chukim ("decrees" – laws without obvious explanation, such as shatnez, the law prohibiting wearing clothing made of mixtures of linen and wool), mishpatim ("judgements" – laws with obvious social implications) and eduyot ("testimonies" or "commemorations", such as the Shabbat and holidays). Through the ages, various rabbinical authorities have classified some of the 613 commandments in many ways.

A different approach divides the laws into a different set of categories:[15]

- Laws in relation to God (bein adam laMakom, lit. "between a person and the Place"), and

- Laws about relations with other people (bein adam le-chavero, "between a person and his friend").

Sources and process

[edit]- Chazal (lit. "Our Sages, may their memory be blessed"): all Jewish sages of the Mishna, Tosefta and Talmud eras (c. 250 BCE – c. 625 CE).

- The Zugot ("pairs"), both the 200-year period (c. 170 BCE – 30 CE, "Era of the Pairs") during the Second Temple period in which the spiritual leadership was in the hands of five successions of "pairs" of religious teachers, and to each of these pairs themselves.

- The Tannaim ("repeaters") were rabbis living primarily in Eretz Yisrael who codified the Oral Torah in the form of the Mishnah; 0–200 CE.

- The Amoraim ("sayers") lived in both Eretz Yisrael and Babylonia. Their teachings and discussions were compiled into the two versions of the Gemara; 200–500.

- The Savoraim ("reasoners") lived primarily in Sassanid Babylonia due to the suppression of Judaism in the Eastern Roman Empire under Theodosius II; 500–650.

- The Geonim ("greats" or "geniuses") presided over the two major Babylonian Academies of Sura and Pumbedita; 650–1038.

- The Rishonim ("firsts") are the rabbis of the late medieval period (c. 1038–1563), preceding the Shulchan Aruch.

- The Acharonim ("lasts") are the rabbis from c. 1500 to the present.

The development of halakha in the period before the Maccabees, which has been described as the formative period in the history of its development, is shrouded in obscurity. Historian Yitzhak Baer argued that there was little pure academic legal activity at this period and that many of the laws originating at this time were produced by a means of neighbourly good conduct rules in a similar way as carried out by Greeks in the age of Solon.[16] For example, the first chapter of Bava Kamma, contains a formulation of the law of torts worded in the first person.[5]: 256

The boundaries of Jewish law are determined through the Halakhic process, a religious-ethical system of legal reasoning. Rabbis generally base their opinions on the primary sources of halakha as well as on precedent set by previous rabbinic opinions. The major sources and genre of halakha consulted include:

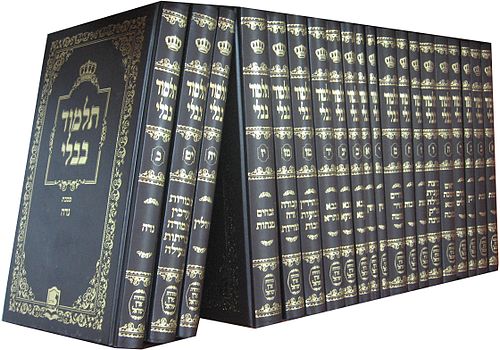

- The foundational Talmudic literature (especially the Mishna and the Babylonian Talmud) with commentaries;

- Talmudic hermeneutics: the science which defines the rules and methods for the investigation and exact determination of the meaning of the Scriptures; also includes the rules from which the Halakhot are derived and which were established by the written law. These may be seen as the rules from which early Jewish law is derived.

- Gemara – the Talmudic process of elucidating the halakha

- The post-Talmudic codificatory literature, such as Maimonides's Mishneh Torah and the Shulchan Aruch with its commentaries (see #Codes of Jewish law below);

- Regulations and other "legislative" enactments promulgated by rabbis and communal bodies:

- Gezeirah ("declaration"): "preventative legislation" of the rabbis, intended to prevent violations of the commandments

- Takkanah ("repair" or "regulation"): "positive legislation", practices instituted by the rabbis not based (directly) on the commandments

- Minhag: Customs, community practices, and customary law, as well as the exemplary deeds of prominent (or local) rabbis;

- The she'eloth u-teshuvoth (responsa, "questions and answers") literature.

- Dina d'malchuta dina ("the law of the king is law"): an additional aspect of halakha, being the principle recognizing non-Jewish laws and non-Jewish legal jurisdiction as binding on Jewish citizens, provided that they are not contrary to a law in Judaism. This principle applies primarily in areas of commercial, civil and criminal law.

In antiquity, the Sanhedrin functioned essentially as the Supreme Court and legislature (in the US judicial system) for Judaism, and had the power to administer binding law, including both received law and its own rabbinic decrees, on all Jews—rulings of the Sanhedrin became halakha; see Oral law. That court ceased to function in its full mode in 40 CE. Today, the authoritative application of Jewish law is left to the local rabbi, and the local rabbinical courts, with only local applicability. In branches of Judaism that follow halakha, lay individuals make numerous ad-hoc decisions but are regarded as not having authority to decide certain issues definitively.

Since the days of the Sanhedrin, however, no body or authority has been generally regarded as having the authority to create universally recognized precedents. As a result, halakha has developed in a somewhat different fashion from Anglo-American legal systems with a Supreme Court able to provide universally accepted precedents. Generally, Halakhic arguments are effectively, yet unofficially, peer-reviewed. When a rabbinic posek ("he who makes a statement", "decisor") proposes an additional interpretation of a law, that interpretation may be considered binding for the posek's questioner or immediate community. Depending on the stature of the posek and the quality of the decision, an interpretation may also be gradually accepted by other rabbis and members of other Jewish communities.

Under this system there is a tension between the relevance of earlier and later authorities in constraining Halakhic interpretation and innovation. On the one hand, there is a principle in halakha not to overrule a specific law from an earlier era, after it is accepted by the community as a law or vow,[17] unless supported by another, relevant earlier precedent; see list below. On the other hand, another principle recognizes the responsibility and authority of later authorities, and especially the posek handling a then-current question. In addition, the halakha embodies a wide range of principles that permit judicial discretion and deviation (Ben-Menahem).

Notwithstanding the potential for innovation, rabbis and Jewish communities differ greatly on how they make changes in halakha. Notably, poskim frequently extend the application of a law to new situations, but do not consider such applications as constituting a "change" in halakha. For example, many Orthodox rulings concerning electricity are derived from rulings concerning fire, as closing an electrical circuit may cause a spark. In contrast, Conservative poskim consider that switching on electrical equipment is physically and chemically more like turning on a water tap (which is permissible by halakha) than lighting a fire (which is not permissible), and therefore permitted on Shabbat. The reformative Judaism in some cases explicitly interprets halakha to take into account its view of contemporary society. For instance, most Conservative rabbis extend the application of certain Jewish obligations and permissible activities to women (see below).

Within certain Jewish communities, formal organized bodies do exist. Within Modern Orthodox Judaism, there is no one committee or leader, but Modern US-based Orthodox rabbis generally agree with the views set by consensus by the leaders of the Rabbinical Council of America. Within Conservative Judaism, the Rabbinical Assembly has an official Committee on Jewish Law and Standards.[18]

Note that takkanot (plural of takkanah) in general do not affect or restrict observance of Torah mitzvot. (Sometimes takkanah refers to either gezeirot or takkanot.) However, the Talmud states that in exceptional cases, the Sages had the authority to "uproot matters from the Torah". In Talmudic and classical Halakhic literature, this authority refers to the authority to prohibit some things that would otherwise be Biblically sanctioned (shev v'al ta'aseh, "thou shall stay seated and not do"). Rabbis may rule that a specific mitzvah from the Torah should not be performed, e. g., blowing the shofar on Shabbat, or taking the lulav and etrog on Shabbat. These examples of takkanot which may be executed out of caution lest some might otherwise carry the mentioned items between home and the synagogue, thus inadvertently violating a Sabbath melakha. Another rare and limited form of takkanah involved overriding Torah prohibitions. In some cases, the Sages allowed the temporary violation of a prohibition in order to maintain the Jewish system as a whole. This was part of the basis for Esther's relationship with Ahasuerus (Xeres). For general usage of takkanaot in Jewish history see the article Takkanah. For examples of this being used in Conservative Judaism, see Conservative halakha.

Historical analysis

[edit]| Rabbinical eras |

|---|

The antiquity of the rules can be determined only by the dates of the authorities who quote them; in general, they cannot safely be declared older than the tanna ("repeater") to whom they are first ascribed. It is certain, however, that the seven middot ("measurements", and referring to [good] behavior) of Hillel and the thirteen of Ishmael are earlier than the time of Hillel himself, who was the first to transmit them.

The Talmud gives no information concerning the origin of the middot, although the Geonim ("Sages") regarded them as Sinaitic (Law given to Moses at Sinai).

The middot seem to have been first laid down as abstract rules by the teachers of Hillel, though they were not immediately recognized by all as valid and binding. Different schools interpreted and modified them, restricted or expanded them, in various ways. Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Ishmael and their scholars especially contributed to the development or establishment of these rules. "It must be borne in mind, however, that neither Hillel, Ishmael, nor [a contemporary of theirs named] Eliezer ben Jose sought to give a complete enumeration of the rules of interpretation current in his day, but that they omitted from their collections many rules which were then followed."[19]

Akiva devoted his attention particularly to the grammatical and exegetical rules, while Ishmael developed the logical. The rules laid down by one school were frequently rejected by another because the principles that guided them in their respective formulations were essentially different. According to Akiva, the divine language of the Torah is distinguished from the speech of men by the fact that in the former no word or sound is superfluous.

Some scholars have observed a similarity between these rabbinic rules of interpretation and the hermeneutics of ancient Hellenistic culture. For example, Saul Lieberman argues that the names of rabbi Ishmael's middot (e. g., kal vahomer, a combination of the archaic form of the word for "straw" and the word for "clay" – "straw and clay", referring to the obvious [means of making a mud brick]) are Hebrew translations of Greek terms, although the methods of those middot are not Greek in origin.[20][21][22]

Views today

[edit]Orthodox Judaism holds that halakha is divine law laid down in the Torah, rabbinical laws, rabbinical decrees, and customs combined. The rabbis, who made many additions and interpretations of Jewish law, did so only in accordance with regulations they believed, as Orthodox Jews still believe, were given for this purpose to Moses on Mount Sinai.[23][24]

Conservative Judaism holds that halakha is normative and binding and is developed as a partnership between people and God based on the Sinaitic Torah. While there is a wide variety of Conservative views, a common belief is that halakha is, and has always been, an evolving process subject to interpretation by rabbis in every time period.

Reconstructionist Judaism asserts that halakha is normative and binding; however, it also views halakha as an evolving concept. The traditional halakhic system, according to this perspective, cannot produce a code of conduct that is meaningful and acceptable to the majority of contemporary Jews. Reconstructionism's founder, Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, believed that "Jewish life [is] meaningless without Jewish law." One of the planks of the Society for the Jewish Renascence, of which Kaplan was a founder, stated: "We accept the halakha, which is rooted in the Talmud, as the norm of Jewish life, availing ourselves, at the same time, of the method implicit therein to interpret and develop the body of Jewish Law in accordance with the actual conditions and spiritual needs of modern life."[25]

Reform Judaism holds that modern views of how the Torah and rabbinic law developed imply that the body of rabbinic Jewish law is no longer normative (seen as binding) on Jews today. Those in the "traditionalist" wing believe that the halakha represents a personal starting point, holding that each Jew is obligated to interpret the Torah, Talmud, and other Jewish works for themselves, and this interpretation will create separate commandments for each person. Those in the liberal and classical wings of Reform believe that in this day and era, most Jewish religious rituals are no longer necessary, and many hold that following most Jewish laws is actually counter-productive. They propose that Judaism has entered a phase of ethical monotheism and that the laws of Judaism are only remnants of an earlier stage of religious evolution and need not be followed. This is considered wrong, and even heretical, by Orthodox and Conservative Judaism.

Humanistic Judaism values the Torah as a historical, political, and sociological text written by their ancestors. They do not believe "that every word of the Torah is true, or even morally correct, just because the Torah is old". The Torah is both disagreed with and questioned. Humanistic Jews believe that the entire Jewish experience, and not only the Torah, should be studied as a source for Jewish behavior and ethical values.[26]

Some Jews believe that gentiles are bound by a subset of halakha called the Seven Laws of Noah, also referred to as the Noahide Laws. According to the Talmud, they are a set of imperatives given by God to the "children of Noah" – that is, all of humanity.[27]

Flexibility

[edit]Despite its internal rigidity, halakha has a degree of flexibility in finding solutions to modern problems not explicitly mentioned in the Torah. From the very beginnings of Rabbinic Judaism, halakhic inquiry allowed for a "sense of continuity between past and present, a self-evident trust that their pattern of life and belief now conformed to the sacred patterns and beliefs presented by scripture and tradition".[28] According to an analysis by Jewish scholar Jeffrey Rubenstein of Michael Berger's book Rabbinic Authority, the authority that rabbis hold "derives not from the institutional or personal authority of the sages but from a communal decision to recognize that authority, much as a community recognizes a certain judicial system to resolve its disputes and interpret its laws."[29] Given this covenantal relationship, rabbis are charged with connecting their contemporary community with the traditions and precedents of the past.

When presented with contemporary issues, rabbis go through a halakhic process to find an answer. The classical approach has permitted new rulings regarding modern technology. For example, some of these rulings guide Jewish observers about the proper use of electricity on the Sabbath and holidays. Often, as to the applicability of the law in any given situation, the proviso is to "consult your local rabbi or posek". This notion lends rabbis a certain degree of local authority; however, for more complex questions, the issue is passed on to higher rabbis, who will then issue a teshuva, which is a responsum that is binding.[30] Indeed, rabbis will continuously issue different opinions and will constantly review each other's work so as to maintain the truest sense of halakha. This process allows rabbis to maintain a connection of traditional Jewish law to modern life. Of course, the degree of flexibility depends on the sect of Judaism, with Reform being the most flexible, Conservative somewhat in the middle, and Orthodox being much more stringent and rigid. Modern critics, however, have charged that with the rise of movements that challenge the "divine" authority of halakha, traditional Jews have greater reluctance to change not only the laws themselves but also other customs and habits than traditional Rabbinical Judaism did before the advent of Reform in the 19th century.

Denominational approaches

[edit]Orthodox Judaism

[edit]

Orthodox Jews believe that halakha is a religious system whose core represents the revealed will of God. Although Orthodox Judaism acknowledges that rabbis have made many decisions and decrees regarding Jewish Law where the written Torah itself is nonspecific, they did so only in accordance with regulations received by Moses on Mount Sinai (see Deuteronomy 5:8–13). These regulations were transmitted orally until shortly after the destruction of the Second Temple. They were then recorded in the Mishnah, and explained in the Talmud and commentaries throughout history up until the present day. Orthodox Judaism believes that subsequent interpretations have been derived with the utmost accuracy and care. The most widely accepted codes of Jewish law are known as Mishneh Torah and the Shulchan Aruch.[31]

Orthodox Judaism has a range of opinions on the circumstances and extent to which change is permissible. Haredi Jews generally hold that even minhagim (customs) must be retained, and existing precedents cannot be reconsidered. Modern Orthodox authorities are more inclined to permit limited changes in customs and some reconsideration of precedent.[32]

Despite the Orthodox views that halakha was given at Sinai, Orthodox thought (and especially modern Orthodox thought) encourages debate, allows for disagreement, and encourages rabbis to enact decisions based on contemporary needs. Rabbi Moshe Feinstein says in his introduction to his collection of responsa that a rabbi who studies the texts carefully is required to provide a halakhic decision. That decision is considered to be a true teaching, even if it is not the true teaching in according to the heavens.[33] For instance, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik believes that the job of a halakhic decisor is to apply halakha − which exists in an ideal realm−to people's lived experiences.[34] Moshe Shmuel Glasner, the chief rabbi of Cluj (Klausenberg in German or קלויזנבורג in Yiddish) stated that the Oral Torah was an oral tradition by design, to allow for the creative application of halakha to each time period, and even enabling halakha to evolve. He writes:

Thus, whoever has due regard for the truth will conclude that the reason the [proper] interpretation of the Torah was transmitted orally and forbidden to be written down was not to make [the Torah] unchanging and not to tie the hands of the sages of every generation from interpreting Scripture according to their understanding. Only in this way can the eternity of Torah be understood [properly], for the changes in the generations and their opinions, situation and material and moral condition requires changes in their laws, decrees and improvements.[35]

Conservative Judaism

[edit]

The view held by Conservative Judaism is that the Torah is not the word of God in a literal sense. However, the Torah is still held as mankind's record of its understanding of God's revelation, and thus still has divine authority. Therefore, halakha is still seen as binding. Conservative Jews use modern methods of historical study to learn how Jewish law has changed over time, and are, in some cases, willing to change Jewish law in the present.[36]

A key practical difference between Conservative and Orthodox approaches is that Conservative Judaism holds that its rabbinical body's powers are not limited to reconsidering later precedents based on earlier sources, but the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards (CJLS) is empowered to override Biblical and Taanitic prohibitions by takkanah (decree) when perceived to be inconsistent with modern requirements or views of ethics. The CJLS has used this power on a number of occasions, most famously in the "driving teshuva", which says that if someone is unable to walk to any synagogue on the Sabbath, and their commitment to observance is so loose that not attending synagogue may lead them to drop it altogether, their rabbi may give them a dispensation to drive there and back; and more recently in its decision prohibiting the taking of evidence on mamzer status on the grounds that implementing such a status is immoral. The CJLS has also held that the Talmudic concept of Kavod HaBriyot permits lifting rabbinic decrees (as distinct from carving narrow exceptions) on grounds of human dignity, and used this principle in a December 2006 opinion lifting all rabbinic prohibitions on homosexual conduct (the opinion held that only male-male anal sex was forbidden by the Bible and that this remained prohibited). Conservative Judaism also made a number of changes to the role of women in Judaism including counting women in a minyan,[37] permitting women to chant from the Torah,[38] and ordaining women as rabbis.[39]

The Conservative approach to halakhic interpretation can be seen in the CJLS's acceptance of Rabbi Elie Kaplan Spitz's responsum decreeing the biblical category of mamzer as "inoperative."[40] The CJLS adopted the responsum's view that the "morality which we learn through the larger, unfolding narrative of our tradition" informs the application of Mosaic law.[40] The responsum cited several examples of how the rabbinic sages declined to enforce punishments explicitly mandated by Torah law. The examples include the trial of the accused adulteress (sotah), the "law of breaking the neck of the heifer," and the application of the death penalty for the "rebellious child."[41] Kaplan Spitz argues that the punishment of the mamzer has been effectively inoperative for nearly two thousand years due to deliberate rabbinic inaction. Further he suggested that the rabbis have long regarded the punishment declared by the Torah as immoral, and came to the conclusion that no court should agree to hear testimony on mamzerut.

Codes of Jewish law

[edit]

The most important codifications of Jewish law include the following; for complementary discussion, see also History of responsa in Judaism.

- The Mishnah, composed by Judah haNasi, in 200 CE, as a basic outline of the state of the Oral Law in his time. This was the framework upon which the Talmud was based; the Talmud's dialectic analysis of the content of the Mishna (gemara; completed c. 500) became the basis for all later halakhic decisions and subsequent codes.

- Codifications by the Geonim of the halakhic material in the Talmud.

- An early work, She'iltot ("Questions") by Ahai of Shabha (c. 752) discusses over 190 mitzvot – exploring and addressing various questions on these. The She'iltot was influential on both of the following, subsequent works.

- The first legal codex proper, Halachot Pesukot ("Decided Laws"), by Yehudai ben Nahman (c. 760), rearranges the Talmud passages in a structure manageable to the layman. (It was written in vernacular Aramaic, and subsequently translated into Hebrew as Hilkhot Riu.)

- Halakhot Gedolot ("Great Law Book"), by Simeon Kayyara, published two generations later (but possibly written c. 743 CE), contains extensive additional material, mainly from Responsa and Monographs of the Geonim, and is presented in a form that is closer to the original Talmud language and structure. (Probably since it was distributed, also, amongst the newly established Ashkenazi communities.)

- The Hilchot HaRif was written by the Rabbi Isaac Alfasi (1013–1103); it has summations of the legal material found in the Talmud. Alfasi transcribed the Talmud's halakhic conclusions verbatim, without the surrounding deliberation; he also excluded all aggadic (non-legal, and homiletic) matter. The Hilchot soon superseded the geonic codes, as it contained all the decisions and the laws then relevant, and additionally, served as an accessible Talmudic commentary; it has been printed with almost every subsequent edition of the Talmud.

- The Mishneh Torah by Maimonides (1135–1204). This work encompasses the full range of Talmudic law; it is organized and reformulated in a logical system – in 14 books, 83 sections and 1000 chapters – with each halakha stated clearly. The Mishneh Torah is very influential to this day, and several later works reproduce passages verbatim. It also includes a section on Metaphysics and fundamental beliefs. (Some claim this section draws heavily on Aristotelian science and metaphysics; others suggest that it is within the tradition of Saadia Gaon.) It is the main source of practical halakha for many Yemenite Jews – mainly Baladi and Dor Daim – as well as for a growing community referred to as talmidei haRambam.

- The work of the Rosh, Rabbi Asher ben Jehiel (1250?/1259?–1328), an abstract of the Talmud, concisely stating the final halakhic decision and quoting later authorities, notably Alfasi, Maimonides, and the Tosafists. This work superseded Rabbi Alfasi's and has been printed with almost every subsequent edition of the Talmud.

- The Sefer Mitzvot Gadol (The "SeMaG") of Rabbi Moses ben Jacob of Coucy (first half of the 13th century, Coucy, northern France). "SeMaG" is organised around the 365 negative and the 248 positive commandments, separately discussing each of them according to the Talmud (in light of the commentaries of Rashi and the Tosafot) and the other codes existent at the time. Sefer Mitzvot Katan ("SeMaK") by Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil is an abridgement of the SeMaG, including additional practical halakha, as well as aggadic and ethical material.

- "The Mordechai" – by Mordecai ben Hillel (d. Nuremberg 1298) – serves both as a source of analysis, as well as of decided law. Mordechai considered about 350 halakhic authorities, and was widely influential, particularly amongst the Ashkenazi and Italian communities. Although organised around the Hilchot of the Rif (Rabbi Isaac Alfasi), it is, in fact, an independent work. It has been printed with every edition of the Talmud since 1482.

- The Arba'ah Turim (lit. "The Four Columns"; the Tur) by Rabbi Jacob ben Asher (1270–1343, Toledo, Spain). This work traces the halakha from the Torah text and the Talmud through the Rishonim, with the Hilchot of Alfasi as its starting point. Ben Asher followed Maimonides's precedent in arranging his work in a topical order, however, the Tur covers only those areas of Jewish law that were in force in the author's time. The code is divided into four main sections; almost all codes since this time have followed the Tur's arrangement of material.

- Orach Chayim ("The Way of Life"): worship and ritual observance in the home and synagogue, through the course of the day, the weekly sabbath and the festival cycle.

- Yoreh De'ah ("Teach Knowledge"): assorted ritual instructions and prohibitions, dietary laws and regulations concerning menstrual impurity.

- Even Ha'ezer ("The Rock of the Helpmate"): marriage, divorce and other issues in family law.

- Choshen Mishpat ("The Breastplate of Judgement"): The administration and adjudication of civil law.

- Agur (c. 1490) by Rabbi Jacob ben Judah Landau comprises principally an abridged presentation of the first and second parts of the Tur, emphasizing practice; it also excerpts other works, and includes Kabbalistic elements. The Agur was the first sefer to contain a Haskama (rabbinical approbation). It was influential on subsequent codes.

- The Beit Yosef and the Shulchan Aruch of Rabbi Yosef Karo (1488–1575). The Beit Yosef is a huge commentary on the Tur in which Rabbi Karo traces the development of each law from the Talmud through later rabbinical literature (examining 32 authorities, beginning with the Talmud and ending with the works of Rabbi Israel Isserlein). The Shulchan Aruch (literally "set table") is, in turn, a condensation of the Beit Yosef – stating each ruling simply; this work follows the chapter divisions of the Tur. The Shulchan Aruch, together with its related commentaries, is considered by many to be the most authoritative compilation of halakha since the Talmud. In writing the Shulchan Aruch, Rabbi Karo based his rulings on three authorities – Maimonides, Asher ben Jehiel (Rosh), and Isaac Alfasi (Rif); he considered the Mordechai in inconclusive cases. Sephardic Jews, generally, refer to the Shulchan Aruch as the basis for their daily practice.

- The works of Rabbi Moshe Isserles ("Rema"; Kraków, Poland, 1525 to 1572). Isserles noted that the Shulchan Aruch was based on the Sephardic tradition, and he created a series of glosses to be appended to the text of the Shulkhan Aruch for cases where Sephardi and Ashkenazi customs differed (based on the works of Yaakov Moelin, Israel Isserlein, and Israel Bruna). The glosses are called ha-Mapah ("the Tablecloth"). His comments are now incorporated into the body of all printed editions of the Shulchan Aruch, typeset in a different script; today, "Shulchan Aruch" refers to the combined work of Karo and Isserles. Isserles' Darkhei Moshe is similarly a commentary on the Tur and the Beit Yosef.

- The Levush Malkhut ("Levush") of Rabbi Mordecai Yoffe (c. 1530–1612). A ten-volume work, five discussing halakha at a level "midway between the two extremes: the lengthy Beit Yosef of Karo on the one hand, and on the other Karo's Shulchan Aruch together with the Mappah of Isserles, which is too brief", that particularly stresses the customs and practices of the Jews of Eastern Europe. The Levush was exceptional among the codes, in that it treated certain Halakhot from a Kabbalistic standpoint.

- The Shulchan Aruch HaRav of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi (c. 1800) was an attempt to re-codify the law as it stood at that time – incorporating commentaries on the Shulchan Aruch, and subsequent responsa – and thus stating the decided halakha, as well as the underlying reasoning. The work was written partly so that laymen would be able to study Jewish law. Unfortunately, most of the work was lost in a fire prior to publication. It is the basis of practice for Chabad-Lubavitch and other Hasidic groups and is quoted as authoritative by many subsequent works, Hasidic and non-Hasidic alike.

- Works structured directly on the Shulchan Aruch, providing analysis in light of Acharonic material and codes:

- The Mishnah Berurah of Rabbi Yisroel Meir ha-Kohen, (the "Chofetz Chaim", Poland, 1838–1933) is a commentary on the "Orach Chayim" section of the Shulchan Aruch, discussing the application of each halakha in light of all subsequent Acharonic decisions. It has become the authoritative halakhic guide for much of Orthodox Ashkenazic Jewry in the postwar period.

- Aruch HaShulchan by Rabbi Yechiel Michel Epstein (1829–1888) is a scholarly analysis of halakha through the perspective of the major Rishonim. The work follows the structure of the Tur and the Shulchan Aruch; rules dealing with vows, agriculture, and ritual purity, are discussed in a second work known as Aruch HaShulchan he'Atid.

- Kaf HaChaim on Orach Chayim and parts of Yoreh De'ah, by the Sephardi sage Yaakov Chaim Sofer (Baghdad and Jerusalem, 1870–1939) is similar in scope, authority and approach to the Mishnah Berurah. This work also surveys the views of many kabbalistic sages (particularly Isaac Luria), when these impact the Halakha.

- Yalkut Yosef, by Rabbi Yitzhak Yosef, is a voluminous, widely cited and contemporary work of halakha, based on the rulings of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (1920–2013).

- Piskei T'shuvot, by Rabbi Ben-Zion Simcha Isaac Rabinowitz, is a commentary on Orach Chayim and the Mishna Berura, drawing on contemporary Acharonim. Generally oriented towards the decrees of the Hassidic poskim, it includes practical solutions and instructions for modern Halakhic issues. P'sakim U'T'shuvot by Rabbi Aharon Aryeh Katz (Rabinowitz's son in law) is a similar work on Yoreh De'ah.

- Layman-oriented works of halakha:

- Thesouro dos Dinim ("Treasury of religious rules") by Menasseh Ben Israel (1604–1657) is a reconstituted version of the Shulkhan Arukh, written in Portuguese with the explicit purpose of helping conversos from Iberia reintegrate into halakhic Judaism.[42]

- The Kitzur Shulchan Aruch of Rabbi Shlomo Ganzfried (Hungary 1804–1886), a "digest", covering applicable Halakha from all four sections of Shulchan Aruch, and reflecting the very strict Hungarian customs of the 19th century. It became immensely popular after its publication due to its simplicity, and is still popular in Orthodox Judaism as a framework for study, if not always for practice. This work is not considered binding in the same way as the Mishneh Torah or Shulchan Aruch.

- Chayei Adam and Chochmat Adam by Avraham Danzig (Poland, 1748–1820) are similar Ashkenazi works; the first covers Orach Chaim, the second in large Yoreh De'ah, as well as laws from Even Ha'ezer and Choshen Mishpat pertinent to everyday life.

- The Ben Ish Chai by Yosef Chaim (Baghdad, 1832–1909) is a collection of the laws on everyday life – parallel in scope to the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch – interspersed with mystical insights and customs, addressed to the masses and arranged by the weekly Torah portion. Its wide circulation and coverage has seen it become a standard reference work in Sephardi Halakha.

- Contemporary "series":

- Peninei Halakha by Rabbi Eliezer Melamed. Fifteen volumes thus far, covering a wide range of subjects, from Shabbat to organ donations, and in addition to clearly posing the practical law – reflecting the customs of various communities – also discusses the spiritual foundations of the Halakhot. It is widely studied in the Religious Zionist community.

- Tzurba M’Rabanan by Rabbi Benzion Algazi. Six volumes covering 300 topics[43] from all areas of the Shulchan Aruch, "from the Talmudic source through modern-day halachic application", similarly studied in the Religious Zionist community (and outside Israel, through Mizrachi in numerous Modern Orthodox communities; 15 bilingual translated volumes).

- Nitei Gavriel by Rabbi Gavriel Zinner. Thirty volumes on the entire spectrum of topics in halachah, known for addressing situations not commonly brought in other works, and for delineating the varying approaches amongst the Hasidic branches; for both reasons they are often reprinted.

- Temimei Haderech ("A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice") by Rabbi Isaac Klein with contributions from the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly. This scholarly work is based on the previous traditional law codes, but written from a Conservative Jewish point of view, and not accepted among Orthodox Jews.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Halacha". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "Halacha: The Laws of Jewish Life." Archived 2019-07-18 at the Wayback Machine My Jewish Learning. 8 April 2019.

- ^ Adler 2022.

- ^ "Jewish Custom (Minhag) Versus Law (Halacha)." Archived 2019-12-25 at the Wayback Machine My Jewish Learning. 8 April 2019.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Louis. "Halakhah". Encyclopaedia Judaica (2 ed.).

- ^ a b Schiffman, Lawrence H. "Second Temple and Hellenistic Judaism". Halakhah. Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception. Vol. 11. De Gruyter. pp. 2–8. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "Reconstruction:Proto-Semitic/halak- - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- ^ "Introduction to Halacha, the Jewish Legal Tradition." Archived 2019-01-04 at the Wayback Machine My Jewish Learning. 8 April 2019.

- ^ Glenn 2014, pp. 183–84.

- ^ Messick & Kéchichian 2009.

- ^ Hecht, Mendy. "The 613 Commandments (Mitzvot)." Archived 2019-04-20 at the Wayback Machine Chabad.org. 9 April 2019.

- ^ Danzinger, Eliezer. "How Many of the Torah's Commandments Still Apply?". chabad. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ a b Sinclair, Julian. "D'Oraita." Archived 2019-07-02 at the Wayback Machine The JC. 5 November 2008. 9 April 2019.

- ^ Tauber, Yanki. "5. The 'Written Torah' and the 'Oral Torah.'” Archived 2019-07-02 at the Wayback Machine Chabad.org. 9 April 2019.

- ^ Tauber, Yanki. "The Two-Way Mirror". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2025-10-01.

- ^ Baer, I. F. (1952). "The Historical Foundations of the Halacha". Zion (in Hebrew). 17. Historical Society of Israel: 1–55.

- ^ Rema Choshen Mishpat Chapter 25

- ^ "Committee on Jewish Law and Standards." Archived 2019-05-09 at the Wayback Machine The Rabbinical Assembly. 9 April 2019.

- ^ "TALMUD HERMENEUTICS - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- ^ Lieberman, Saul (1962). "Rabbinic interpretation of scripture". Hellenism in Jewish Palestine. Jewish Theological Seminary of America. p. 47. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Lieberman, Saul (1962). "The Hermeneutic Rules of the Aggadah". Hellenism in Jewish Palestine. Jewish Theological Seminary of America. p. 68. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Daube, David (1949). "Rabbinic methods of interpretation and Hellenistic rhetoric". Hebrew Union College Annual. 22: 239–264. JSTOR 23506588.

- ^ Deuteronomy 17:11

- ^ "Vail course explores origins of Judaism". Vail Daily. 13 July 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

"Just as science follows the scientific method, Judaism has its own system to ensure authenticity remains intact," said Rabbi Zalman Abraham of JLI's New York headquarters.

- ^ Cedarbaum, Daniel (6 May 2016). "Reconstructing Halakha". Reconstructing Judaism. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "FAQ for Humanistic Judaism, Reform Judaism, Humanists, Humanistic Jews, Congregation, Arizona, AZ". Oradam.org. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "Noahide Laws." Archived 2016-01-21 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopedia Britannica. 3 July 2019.

- ^ Corrigan, John; Denny, Frederick; Jaffee, Martin S.; Eire, Carlos (2016). Jews, Christians, Muslims: A Comparative Introduction to Monotheistic Religions (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9780205018253. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Rubenstein, Jeffrey L. (2002). "Michael Berger. Rabbinic Authority. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. xii, 226 pp". AJS Review. 26 (2) (2 ed.): 356–359. doi:10.1017/S0364009402250114. S2CID 161130964.

- ^ Satlow, Michael, and Daniel Picus. “Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.” Lecture. Providence, Brown University.

- ^ Jacobs, Jill. "The Shulchan Aruch Archived 2018-12-25 at the Wayback Machine." My Jewish Learning. 8 April 2019.

- ^ Sokol, Sam. "A journal’s new editor wants to steer the Modern Orthodox debate into the 21st century." Archived 2019-03-31 at the Wayback Machine Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 7 February 2019. 8 April 2019.

- ^ Feinstein, Rabbi Moshe. "Introduction to Orach Chayim Chelek Aleph". Iggrot Moshe (in Hebrew). [...] אבל האמת להוראה כבר נאמר לא בשמים היא אלא כפי שנראה להחכם אחרי שעיין כראוי לברר ההלכה בש"ס ובפוסקים כפי כחו בכובד ראש וביראה מהשי"ת ונראה לו שכן הוא פסק הדין הוא האמת להוראה ומחוייב להורות כן אף אם בעצם גליא כלפי שמיא שאינו כן הפירוש, ועל כזה נאמר שגם דבריו דברי אלקים חיים מאחר שלו נראה הפירוש כמו שפסק ולא היה סתירה לדבריו. ויקבל שכר על הוראתו אף שהאמת אינו כפירוש.

- ^ Kaplan, Lawrence (1973). "The Religious Philosophy of Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik". Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought. 14 (2): 43–64. JSTOR 23257361.

- ^ Glasner, Moshe Shmuel, Introduction to the דור רביעי, translated by Yaakov Elman, archived from the original on 2023-04-17, retrieved 2023-05-09

- ^ "Halakhah in Conservative Judaism." Archived 2019-12-24 at the Wayback Machine My Jewish Learning. 8 April 2019.

- ^ Fine, David J. "Women and the Minyan." Archived 2020-06-17 at the Wayback Machine Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly. OH 55:1.2002. p. 23.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about Masorti." Archived 2019-06-19 at the Wayback Machine Masorti Olami. 25 March 2014. 8 April 2019.

- ^ Goldman, Ari. "Conservative Assembly ...." Archived 2019-12-31 at the Wayback Machine New York Times. 14 February 1985. 8 April 2019.

- ^ a b Kaplan Spitz, Elie. "Mamzerut." Archived 2019-12-27 at the Wayback Machine Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly. EH 4.2000a. p. 586.

- ^ Kaplan Spitz, p. 577-584.

- ^ Moreno-Goldschmidt, Aliza (2020). "Menasseh ben Israel's Thesouro dos Dinim: Reeducating the New Jews". Jewish History. 33 (3–4): 325–350. doi:10.1007/s10835-020-09360-5. S2CID 225559599 – via SpringerLink.

- ^ Tzurba Learning-Schedule Archived 2020-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, mizrachi.org

Bibliography

[edit]- Adler, Yonatan (2022). The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300254907.

- J. David Bleich, Contemporary Halakhic Problems (5 vols), Ktav ISBN 0-87068-450-7, 0-88125-474-6, 0-88125-315-4, 0-87068-275-X; Feldheim ISBN 1-56871-353-3

- Menachem Elon, Ha-Mishpat ha-Ivri (trans. Jewish Law: History, Sources, Principles ISBN 0-8276-0389-4); Jewish Publication Society ISBN 0-8276-0537-4

- Glenn, H. Patrick (2014). Legal Traditions of the World – Sustainable Diversity in Law (5th edition) ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199669837

- Jacob Katz, Divine Law in Human Hands – Case Studies in Halakhic Flexibility, Magnes Press. ISBN 965-223-980-1

- Moshe Koppel, "Meta-Halakhah: Logic, Intuition, and the Unfolding of Jewish Law", ISBN 1-56821-901-6

- Mendell Lewittes, Jewish Law: An Introduction, Jason Aronson. ISBN 1-56821-302-6

- Messick, Brinkley; Kéchichian, Joseph A. (2009). "Fatwā. Process and Function". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015.

- Daniel Pollack ed., Contrasts in American and Jewish Law, Ktav. ISBN 0-88125-750-8

- Emanuel Quint, A Restatement of Rabbinic Civil Law (11 vols), Gefen Publishing. ISBN 0-87668-765-6, 0-87668-799-0, 0-87668-678-1, 0-87668-396-0, 0-87668-197-6, 1-56821-167-8, 1-56821-319-0, 1-56821-907-5, 0-7657-9969-3, 965-229-322-9, 965-229-323-7, 965-229-375-X

- Emanuel Quint, Jewish Jurisprudence: Its Sources & Modern Applications , Taylor and Francis. ISBN 3-7186-0293-8

- Steven H. Resnicoff, Understanding Jewish Law, LexisNexis, 2012. ISBN 978-1422490204

- Joel Roth, Halakhic Process: A Systemic Analysis, Jewish Theological Seminary. ISBN 0-87334-035-3

- Joseph Soloveitchik, Halakhic Man, Jewish Publication Society trans. Lawrence Kaplan. ISBN 0-8276-0397-5

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Further reading

[edit]- Dorff, Elliot N.; Rosett, Arthur (1988). A Living Tree: The Roots and Growth of Jewish Law. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-88706-459-0.

- Neusner, Jacob (1974–1977). A History of the Mishnaic Law of Purities. Leiden: E. J. Brill. Part I–XXII.

- Neusner, Jacob (1979–1980). A History of the Mishnaic Law of Holy Things. Leiden: E. J. Brill. Part I–VI. Reprint: Eugene, Or: Wipf and Stock Publ., 2007, ISBN 1-55635-349-9

- Neusner, Jacob (1979–1980). A History of the Mishnaic Law of Women. Leiden: E. J. Brill. Part I–V.

- Neusner, Jacob (1981–1983). A History of the Mishnaic Law of Appointed Times. Leiden: E. J. Brill. Part I–V.

- Neusner, Jacob (1983–1985). A History of the Mishnaic Law of Damages. Leiden: E. J.Brill. Part I–V.

- Neusner, Jacob (2000). The Halakhah: An Encyclopaedia of the Law of Judaism. The Brill Reference Library of Judaism. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 9004116176

- Vol. 1: Between Israel and God. Part A. Faith, Thanksgiving, Enlandisement: Possession and Partnership.

- Vol. 2: Between Israel and God. Part B. Transcendent Transactions: Where Heaven and Earth Intersect.

- Vol. 3: Within Israel’s Social Order.

- Vol. 4: Inside the Walls of the Israelite Household. Part A. At the Meeting of Time and Space. Sanctification in the Here and Now: The Table and the Bed. Sanctification and the Marital Bond. The Desacralization of the Household: The Bed.

- Vol. 5: Inside the Walls of the Israelite Household. Part B. The Desacralization of the Household: The Table. Foci, Sources, and Dissemination of Uncleanness. Purification from the Pollution of Death.

- Neusner, Jacob, ed. (2005). The Law of Agriculture in the Mishnah and the Tosefta. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

External links

[edit]Full-text resources of major halakhic works

- Mishneh Torah: Hebrew; English

- Arba'ah Turim: Hebrew

- Shulchan Aruch: Hebrew; English (incomplete)

- Shulchan Aruch HaRav: Hebrew

- Aruch HaShulchan: Hebrew

- Kitzur Shulchan Aruch: Hebrew; English[usurped]

- Ben Ish Chai: Hebrew

- Kaf HaChaim: Hebrew (search on site)

- Mishnah Berurah: Hebrew; English

- Chayei Adam: Hebrew

- Chochmat Adam: Hebrew

- Peninei Halakha: Hebrew; English

- Yalkut Yosef: Hebrew

- A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice: Hebrew

Halakha

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Definition and Core Concepts

Halakha, from the Hebrew root halakh meaning "to walk" or "to go," constitutes the body of Jewish religious laws directing the behavior of observant Jews in ritual, ethical, and civil matters.[3][10] It derives primarily from the 613 commandments (mitzvot) enumerated in the Torah—248 positive injunctions and 365 prohibitions—supplemented by rabbinic enactments and longstanding customs.[11][2] At its core, Halakha functions as a normative system prescribing a divine path for human conduct, distinguishing it from aggadah, which encompasses non-legal narrative and ethical teachings.[3] In traditional Orthodox understanding, it embodies God's revealed will, requiring adaptation of eternal principles to evolving circumstances through authorized rabbinic interpretation while preserving the Torah's immutability.[12] This process integrates interpretive rules, consensus among scholars, and precedent to yield practical rulings (psak) binding on the community.[2] Key concepts include the categorization of laws into those between humans and God (e.g., prayer, Sabbath observance) and those between humans (e.g., monetary disputes, interpersonal ethics), emphasizing both ritual purity and social justice as interconnected obligations.[10] Halakha's authority stems from its transmission via the Oral Torah, parallel to the Written Torah, ensuring continuity from Mosaic revelation at Sinai, as articulated in rabbinic literature.[1] Observance entails not merely compliance but a holistic way of life oriented toward covenantal fidelity.[2]Distinction from Aggadah and Related Terms

Halakha constitutes the prescriptive legal framework of rabbinic Judaism, encompassing rules for religious observance, ethical conduct, and communal life derived from biblical texts and rabbinic interpretation.[13] It derives from the Hebrew root h-l-kh, meaning "to walk," signifying the normative path of Jewish practice that demands adherence in daily actions.[14] In contrast, aggadah (or aggada) refers to the non-legal components of rabbinic literature, including narratives, parables, ethical exhortations, theological expositions, and homiletic interpretations aimed at elucidating the deeper meanings of Torah.[15] Aggadah engages with abstract themes such as human conscience, divine relations, and moral sensibilities, often employing metaphorical or allegorical language rather than enforceable directives.[16] The Talmud exemplifies this binary structure, comprising the Mishnah's primarily halakhic discussions amplified by Gemara, where approximately 10-20% of the content shifts to aggadic material interspersed among legal sugyot (debates).[17] Halakhic passages prioritize precision, consensus via majority rabbinic opinion, and applicability to verifiable actions, rendering them binding upon Jewish communities.[18] Aggadic elements, however, permit interpretive flexibility; they inspire piety and worldview but do not serve as sources for legal rulings, as medieval authorities like Maimonides emphasized that aggadah's cryptic style resists literal enforcement and may convey eternal truths through hyperbole or symbolism.[13] Related terms include midrash halakhah, which applies exegetical methods to derive binding laws from Torah verses, distinct from midrash aggadah, which focuses on narrative expansions for inspirational purposes.[19] While halakha and aggadah interrelate—aggadah often providing theological rationale for halakhic observance—their separation ensures halakha's focus on causal, observable compliance, whereas aggadah explores existential dimensions unbound by precedent.[20] This delineation, rooted in tannaitic traditions, underscores rabbinic literature's dual aim: guiding behavior through law while nurturing spiritual depth through lore.[21]Primary Sources

Written Torah and Biblical Foundations

The Written Torah, known as Torah she-bi-Khtav, consists of the Five Books of Moses—Genesis (Bereshit), Exodus (Shemot), Leviticus (Vayikra), Numbers (Bamidbar), and Deuteronomy (Devarim)—which form the core textual basis for Halakha.[22] These books, traditionally attributed to divine revelation to Moses at Mount Sinai around 1312 BCE, contain explicit commandments, narratives, and principles that underpin Jewish legal observance.[22] Halakha derives its authority from these texts, which outline laws governing ritual purity, ethical conduct, civil relations, and worship, though many require interpretive expansion for practical application.[23] Central to the Written Torah are the 613 mitzvot (commandments), enumerated by Maimonides in his Sefer HaMitzvot in the 12th century CE based on Talmudic tradition.[24] Of these, 248 are positive commandments (actions to perform, corresponding to the human body's limbs) and 365 are negative commandments (prohibitions, matching the solar year's days).[24] Approximately 77 positive and 194 negative mitzvot remain observable today, with others contingent on Temple service, land possession in Israel, or specific conditions like kingship.[25] Biblical foundations categorize mitzvot into domains such as those between humans and God (bein adam l'Makom), including monotheistic declarations (Exodus 20:2-3) and Sabbath observance (Exodus 20:8-11), and those between humans (bein adam l'chavero), such as prohibitions against murder (Exodus 20:13) and theft (Exodus 20:15).[26] Ritual laws in Leviticus detail sacrifices, purity (e.g., Leviticus 11 on dietary restrictions), and festivals, while civil codes in Exodus and Deuteronomy address damages, contracts, and justice (e.g., Deuteronomy 16:20 on pursuing righteousness).[26] These foundations emphasize covenantal obligations, with non-observance incurring specified penalties like excision (karet) or capital punishment by human courts for grave offenses (e.g., Leviticus 20:2-5).[25]Oral Torah: Mishnah and Tosefta

The Mishnah, redacted by Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi (also known as Judah the Prince) in the Land of Israel around 200 CE, constitutes the foundational written compilation of the Tannaitic Oral Torah, systematizing oral traditions of biblical interpretation and legal application that had been transmitted verbally since the time of Moses.[27] This redaction occurred amid Roman persecution and the need to preserve Jewish law following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, marking a shift from purely oral transmission to a fixed text while prohibiting broader public documentation to maintain its interpretive fluidity.[28] Composed in Mishnaic Hebrew, the Mishnah organizes halakhic material into six orders (sedarim)—Zeraim (agricultural laws), Moed (festivals), Nashim (women and family), Nezikin (civil and criminal law), Kodashim (sacrificial rites), and Tohorot (purity laws)—encompassing 63 tractates that delineate practical rulings, debates among Tannaim (sages from circa 10–220 CE), and scriptural derivations without explicit proof-texts in most cases. As the core repository of Oral Torah for halakhic practice, the Mishnah supplements the Written Torah by clarifying ambiguities, such as specifying Sabbath prohibitions implied in Exodus 20:8–11, and serves as the basis for subsequent rabbinic analysis, where its unattributed statements typically reflect the view of Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi or consensus.[29] The Tosefta, compiled in Palestine during the early third century CE shortly after the Mishnah, functions as a parallel and supplementary corpus of Tannaitic traditions, drawing on similar sources but including beraitot (external teachings) omitted from the Mishnah, alternative formulations, and expansions on its topics.[30] Attributed in tradition to Rabbi Hiyya or disciples of Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi, it mirrors the Mishnah's six-order structure but expands to greater length, often providing narrative sequences, additional cases, or dialectical exchanges that elucidate or challenge Mishnaic brevity.[31] Scholarly analysis reveals complex interrelations, with some Tosefta passages reflecting earlier or variant versions of Mishnah material, suggesting it may comment on proto-Mishnaic texts or preserve rejected traditions, though it lacks independent canonical authority and is subordinate to the Mishnah in halakhic decision-making.[32] In the development of Halakha, both texts anchor the Oral Torah's legal framework, with the Mishnah providing authoritative baselines for the Gemara's expansions in the Talmuds, while the Tosefta supplies corroborative or supplementary evidence, such as extended rulings on damages in tractate Bava Kamma, ensuring comprehensive coverage of practical observance.[29] Their Tannaitic origin underscores a commitment to preserving interpretive traditions empirically rooted in biblical precedents and rabbinic consensus, forming the exegetical bedrock for later codes without superseding the Written Torah's primacy.[27]Talmudic Expansions: Babylonian and Jerusalem

The Talmudic expansions on the Mishnah consist of the Gemara, comprising analytical discussions by Amoraim that elaborate, debate, and derive halakhic rulings from tannaitic texts. These appear in two parallel compilations: the Jerusalem Talmud (Yerushalmi) and the Babylonian Talmud (Bavli), both central to halakhic methodology through their dialectical expansion of mishnaic laws into practical precedents and interpretive principles.[3] The Yerushalmi was redacted in the Galilee region of the Land of Israel toward the end of the 4th century to early 5th century CE, reflecting Palestinian Amoraic traditions from approximately 220–470 CE. It provides Gemara on the first 39 tractates of the Mishnah, prioritizing orders like Zeraim (agricultural laws) and Moed (festivals), which were pertinent to life in the [Holy Land](/page/Holy Land), while offering incomplete coverage of Nashim, Nezikin, and negligible discussion on Kodashim and Tohorot. Characterized by shorter, more repetitive narratives in Palestinian Aramaic, it preserves unique local customs but suffers from textual fragmentation and less systematic resolution of disputes.[33][3] The Bavli, compiled in Babylonian academies such as Sura and Pumbedita from around 220–500 CE with redaction extending into the 6th century, features intricate, layered arguments in Babylonian Aramaic across 36 and a half non-consecutive tractates, emphasizing Moed through Tohorot with deeper civil, ritual, and ethical analyses. Its comprehensive scope, including extended case studies and cross-references, enabled more refined halakhic conclusions, rendering it superior in clarity and authority.[33][3] For Halakha, the Bavli holds precedence over the Yerushalmi in cases of divergence, as its later development incorporated broader scholarly input, better textual integrity, and the geopolitical dominance of Babylonian Jewry post-5th century CE, which shifted rabbinic leadership eastward. Authorities like Maimonides mandated adherence to Bavli rulings across Jewish communities, using the Yerushalmi primarily as a supplementary source for Palestinian-specific laws or to illuminate ambiguities in the Bavli. Both Talmuds supply the foundational debates—resolving contradictions via majority views, logical inference, or scriptural analogy—that later codes distill into binding norms, underscoring Halakha's evolution from oral discourse to codified practice.[3][33]

Post-Talmudic Authorities: Geonim and Rishonim

The Geonim, heads of the Babylonian academies at Sura and Pumbedita, served as primary halakhic authorities from 589 CE to 1038 CE, succeeding the savoraim in interpreting and applying Talmudic law amid diaspora communities under Islamic rule.[34] Their era marked the institutionalization of responsa (she'elot u-teshuvot), with large-scale production beginning in the mid-8th century, addressing queries on ritual, civil, and communal matters that adapted Talmudic rulings to new realities like Karaite challenges and regional customs.[35][36] Key innovations included the compilation of halakhic codes, such as Rav Amram Gaon's Seder Rav Amram Gaon (c. 850 CE), an early prayer book with legal rubrics, and efforts to enforce Talmudic study through ordinances (taqqanot) that sometimes leniently modified strict halakha to align with prevailing practices.[37][38] Prominent Geonim like Saadia ben Joseph (882–942 CE) integrated philosophy with halakhic defense against sectarians, authoring works like Sefer ha-Mitzvot, while Sherira ben Hanina (c. 906–1006 CE) and Hai ben Sherira (939–1038 CE) issued thousands of responsa that established Babylonian Talmudic primacy over the Jerusalem version.[37] Their authority derived from academy leadership, fostering a centralized model that influenced subsequent rabbinic decision-making.[39] Transitioning from Geonic centralization, the Rishonim—rabbinic scholars spanning roughly the 11th to 15th centuries—decentralized halakhic discourse across Ashkenazic, Sephardic, and Provencal centers, producing commentaries, novellae, and codes that reconciled Talmudic ambiguities through pilpul (dialectical analysis).[40] This period saw the rise of independent academies in Europe post-1066 CE expulsions from Muslim lands, with figures like Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (Rif, 1013–1103 CE) authoring Sefer ha-Halakhot, a concise Talmudic digest excluding non-legal aggadah to guide practical psak (rulings).[41] In France and Germany, Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi, 1040–1105 CE) provided verse-by-verse Talmud commentaries emphasizing plain meaning (peshat), complemented by Tosafot—glosses from his students and descendants (c. 12th–13th centuries) that harmonized apparent contradictions via casuistic extensions.[42] Sephardic Rishonim, including Moses ben Maimon (Rambam, 1138–1204 CE), codified comprehensive systems like the Mishneh Torah (completed 1180 CE), a 14-volume work organizing all mitzvot without direct Talmudic citations to facilitate study and adjudication.[41] Others, such as Nahmanides (Ramban, 1194–1270 CE) and Solomon ben Aderet (Rashba, c. 1235–1310 CE), issued responsa balancing innovation with precedent, often debating Maimonides' rationalism versus stringency in areas like ritual purity and festivals.[42] Geonim and Rishonim advanced halakha by prioritizing empirical Talmudic fidelity, incorporating minhag (custom) via consensus, and using middot (hermeneutic rules) for derivation, though regional divergences emerged—e.g., Ashkenazic leniencies in kitniyot prohibitions absent in Sephardic practice.[43] Their works, exceeding hundreds of volumes by the Rishonim's end, laid precedents for later codifiers, emphasizing majority views in disputes while preserving minority opinions for potential hora'ah (instruction).[42][44] This era's output, disseminated via manuscripts until printing's advent, solidified rabbinic authority against external pressures, ensuring halakha's adaptability without doctrinal rupture.[39]Derivational Principles and Methodology

Interpretive Rules and Middot

The interpretive rules of Halakha, termed middot (measures), comprise a set of formalized hermeneutical principles utilized by rabbinic authorities to elucidate ambiguities in the Written Torah and derive corresponding obligations in the Oral Torah. These rules enable systematic expansion of biblical legislation, addressing issues such as textual inclusions, exclusions, contradictions, and contextual implications, while preserving the integrity of scriptural plain meaning (peshat) as a baseline. Originating in pre-Tannaitic traditions, the middot were first codified by Hillel the Elder around the 1st century BCE, with his seven rules forming the foundation for later elaborations; they emphasize logical inference, analogy (hekkesh from juxtaposition or equality, gezerah shavah from verbal similarity), and scriptural juxtaposition to resolve interpretive challenges, including reconciliation of conflicting texts, without introducing extraneous elements.[45][46] Hillel's middot include kal va-ḥomer (a fortiori reasoning, where a law applicable in a stringent case applies even more so in a lenient one), gezerah shavah (analogy drawn from identical phrasing across verses), binyan av (establishing a general principle from one or two cases), inference from context, and rules for general-particular sequences. These were not universally accepted initially but gained prominence through usage in early rabbinic exegesis, as evidenced in Tannaitic sources like the Sifra. Rabbi Ishmael ben Elisha, a leading tanna of the early 2nd century CE, expanded this framework into thirteen middot, compiled in the Baraita de-Rabbi Ishmael, which introduces the Sifra—a halakhic midrash on Leviticus—and is recited in certain daily prayer services to underscore their role in transmitting Oral Torah derivations.[47][48] Ishmael's thirteen middot build upon Hillel's by subdividing rules (e.g., elaborating general-particular dynamics into multiple variants) and adding mechanisms for contradiction resolution, providing a more granular toolkit for Talmudic debates while requiring traditional validation for certain applications, such as gezerah shavah, which demands a received tradition (mesorah) from Sinai to avoid speculative overreach. The rules are:- Kal va-ḥomer: Inference from minor to major or vice versa.[48]

- Gezerah shavah: Analogy via equivalent expressions in different contexts.

- Binyan av: Building a general rule from one scriptural case.

- Kelal u-peraṭ: A general statement limited by a following particular.

- Perat u-kelal: A particular extended by a following general.

- Kelal u-peraṭ u-kelal la'avor: General-particular-general to include only similar cases.

- Kelal she-hu ṭzarich le-faraṭ: General requiring particular for definition.

- Davar he-hayah bi-khelal ve-yaṣa' le-lamed: Exclusion from general to teach a distinct rule.

- Davar he-hayah bi-khelal ve-yaṣa' ki-ʿinyano: Exclusion aligned with its own context.

- Davar he-hayah bi-khelal ve-yaṣa' lo ki-ʿinyano: Exclusion unrelated to context, limiting the general.

- Davar he-hayah bi-khelal ve-yaṣa' al ribbuy o miʿuṭ: Exclusion for expansion or restriction.

- Davar ha-lamed me-ʿinyano: Inference from immediate context.

- Shenei kesuvim ha-maḥḥishim zeh et zeh: Reconciliation of contradictory verses via a third.[47][48]