Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Organ system

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2019) |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Development of organ systems |

|---|

| Details | |

|---|---|

| System | Lymphatic system |

| Identifiers | |

| FMA | 7149 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

An organ system is a biological system consisting of a group of organs that work together to perform one or more bodily functions.[1] Each organ has a specialized role in an organism body, and is made up of distinct tissues.

Humans

[edit]

There are 11 distinct organ systems in human beings,[2] which form the basis of human anatomy and physiology. The 11 organ systems: the respiratory system, digestive and excretory system, circulatory system, urinary system, integumentary system, skeletal system, muscular system, endocrine system, lymphatic system, nervous system, and reproductive system. There are other systems in the body that are not organ systems—for example, the immune system protects the organism from infection, but it is not an organ system since it is not composed of organs. Some organs are in more than one system—for example, the nose is in the respiratory system and also serves as a sensory organ in the nervous system; the testes and ovaries are both part of the reproductive and endocrine systems.

| Organ system | Description | Component organs |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory system | breathing: exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide | nose, mouth, paranasal sinuses, pharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, lungs and thoracic diaphragm |

| Digestive and excretory system | digestion: breakdown and absorption of nutrients, excretion of solid wastes | teeth, tongue, salivary glands, esophagus, stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, small intestine, large intestine, rectum and anus |

| Circulatory system | circulate blood in order to transport nutrients, waste, hormones, O2, CO2, and aid in maintaining pH and temperature | blood, heart, arteries, veins and capillaries |

| Urinary system | maintain fluid and electrolyte balance, purify blood and excrete liquid waste (urine) | kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra |

| Integumentary system | exterior protection of body and thermal regulation | skin, hair, fat and nails |

| Skeletal system | structural support and protection, production of blood cells | bones, cartilage, ligaments and tendons |

| Muscular system | movement of body, production of heat | skeletal muscles, smooth muscles and cardiac muscle |

| Endocrine system | communication within the body using hormones made by endocrine glands | hypothalamus, pituitary, pineal gland, thyroid, parathyroid and adrenal glands, ovaries and testicles |

| Exocrine system | various functions including lubrication and protection | ceruminous glands, lacrimal glands, sebaceous glands and mucus |

| Lymphatic system | return lymph to the bloodstream, aid immune responses, form white blood cells | lymph, lymph nodes, lymph vessels, tonsils, spleen and thymus |

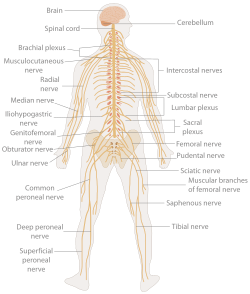

| Nervous system | sensing and processing information, controlling body activities | brain, spinal cord, nerves, sensory organs and the following sensory systems (nervous subsystems): visual system,smell (olfactory system), taste (gustatory system) and hearing (auditory system) |

| Reproductive system | sex organs involved in reproduction | ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, vulva, penis, testicles, vasa deferentia, seminal vesicles and prostate |

Other animals

[edit]Other animals have similar organ systems to humans although simpler animals may have a lot of organs in an organ system or even fewer organ systems.

Plants

[edit]

Plants have two major organs systems. Vascular plants have two distinct organ systems: a shoot system, and a root system. The shoot system consists stems, leaves, and the reproductive parts of the plant (flowers and fruits). The shoot system generally grows above ground, where it absorbs the light needed for photosynthesis. The root system, which supports the plants and absorbs water and minerals, is usually underground.[3]

| Organ system | Description | Component organs |

|---|---|---|

| Root system | anchors plants into place, absorbs water and minerals, and stores carbohydrates | roots |

| Shoot system | stem for holding and orienting leaves to the sun as well as transporting materials between roots and leaves, leaves for photosynthesis, and flowers for reproduction | stem, leaves, and flowers |

References

[edit]- ^ Betts, J Gordon; et al. (2013). 1.2 Structural Organization of the Human Body - Anatomy and Physiology. Openstax. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3. Archived from the original on 2023-03-24. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ Wakim, Suzanne; Grewal, Mandeep (August 8, 2020). "Human Organs and Organ Systems". Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ Hillis, David M.; Sadava, David; Hill, Richard W.; Price, Mary V. (2014). "The plant body". Principles of Life (2nd ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates. pp. 521–536. ISBN 978-1464175121.

Organ system

View on Grokipedia- Integumentary system: Comprising the skin, hair, nails, and glands, it protects against pathogens and environmental hazards while regulating body temperature.[2]

- Skeletal system: Made up of bones, cartilage, and ligaments, it provides structural support, enables movement, and protects vital organs.[1]

- Muscular system: Consisting of skeletal, smooth, and cardiac muscles, it facilitates voluntary and involuntary movements and generates heat.[1]

- Nervous system: Including the brain, spinal cord, and nerves, it coordinates body activities through electrical and chemical signals for sensing and responding to the environment.[1]

- Endocrine system: Formed by glands such as the thyroid and pituitary, it regulates bodily functions via hormones that influence metabolism, growth, and reproduction.[1]

- Cardiovascular (circulatory) system: Encompassing the heart, blood vessels, and blood, it transports oxygen, nutrients, hormones, and waste products throughout the body.[1]

- Lymphatic (immune) system: Composed of lymph nodes, vessels, spleen, and thymus, it defends against infections and returns excess tissue fluid to the bloodstream.[1]

- Respiratory system: Involving the lungs, trachea, and airways, it facilitates gas exchange by inhaling oxygen and exhaling carbon dioxide.[1]

- Digestive system: Including the mouth, stomach, intestines, and accessory organs like the liver, it breaks down food for nutrient absorption and eliminates waste.[1]

- Urinary (excretory) system: Consisting of kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra, it filters blood to remove waste and regulates fluid and electrolyte balance.[1]

- Reproductive system: Differentiated into male (testes, penis) and female (ovaries, uterus) components, it produces gametes and supports offspring development.[1]

Conceptual Foundations

Definition of an Organ System

In biology, the foundational level of organization beyond cells involves tissues, which are groups of similar cells along with their extracellular matrix that perform a common function.[3] These tissues integrate to form organs, defined as anatomically distinct structures composed of two or more tissue types that collaborate to carry out one or more specific physiological roles.[4] For instance, the heart is an organ formed from cardiac muscle tissue, connective tissue, and epithelial tissue, enabling it to pump blood effectively.[4] An organ system represents the next hierarchical level, consisting of a group of two or more organs that interact in a coordinated manner to perform one or more complex functions essential for the organism's survival.[5] Each organ within the system contributes specialized roles, with their activities integrated through mechanisms such as neural signaling, hormonal regulation, or direct physical connections to achieve overall functionality.[6] Basic integration often occurs via feedback loops, where outputs from one organ influence the activity of others to maintain balance; for example, negative feedback mechanisms can adjust organ responses to stabilize internal conditions.[7] This coordination ensures that the system operates as a unified whole rather than isolated parts. The distinction between an organ and an organ system is primarily functional and structural: an organ is a self-contained unit focused on a singular or limited set of tasks, whereas an organ system encompasses multiple organs working interdependently toward broader physiological goals.[4] Etymologically, "organ" derives from the Greek organon, meaning "tool" or "instrument," reflecting its role as a specialized functional component, while "system" stems from systema, denoting an "organized whole" assembled from parts.[8][9] Through such organ system interactions, organisms achieve homeostasis, the dynamic maintenance of stable internal environments.Historical Context

The concept of organ systems as coordinated groups of organs functioning together traces its roots to ancient observations in Greek and Roman biology. Aristotle, in his work History of Animals (circa 350 BCE), provided one of the earliest systematic classifications of animal organs, grouping them based on their roles in respiration, nutrition, and reproduction, such as the heart, lungs, and esophagus in blooded animals.[10] Similarly, Galen of Pergamon (129–circa 216 CE), building on Hippocratic traditions, integrated organs into his humoral theory, viewing them as interconnected components that balanced the four humors—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—to maintain bodily harmony, with the liver, heart, and brain serving as key regulatory sites. The Renaissance marked a pivotal shift toward empirical anatomy, challenging ancient authorities through direct dissection. Andreas Vesalius's De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543) revolutionized understanding by presenting detailed illustrations and descriptions of human organ groupings, including the vascular, nervous, and digestive systems, emphasizing their structural interdependence and correcting Galenic errors based on human cadavers rather than animal proxies.[11] This work laid the groundwork for recognizing organ systems as functional units, influencing subsequent anatomists like William Harvey, who in 1628 described the circulatory system's closed loop. In the 19th century, physiological integration elevated organ systems from static anatomy to dynamic regulators of bodily stability. Claude Bernard, in lectures from the 1850s and his 1865 Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, introduced the concept of milieu intérieur, positing that organs collectively maintain a constant internal environment despite external changes, as seen in the liver's regulation of blood glucose.[12] Building on this, Walter B. Cannon coined "homeostasis" in his 1926 paper "Physiological Regulation of Normal States," framing organ systems—such as the endocrine and nervous—as coordinated mechanisms preserving equilibrium, exemplified by adrenal responses to stress.[13] The late 20th century saw the emergence of systems biology, refining organ system concepts through molecular and computational lenses. In the 1990s, advances in genomics and high-throughput technologies, as articulated in early frameworks like those from Leroy Hood's group, shifted focus to integrative models of organ interactions, treating systems like the immune or cardiovascular as networks of genes, proteins, and cells rather than isolated units.[14] Key milestones include Aristotle's organ classifications (4th century BCE), Galen's humoral integrations (2nd century CE), Vesalius's anatomical treatise (1543), Bernard's milieu intérieur (1865), Cannon's homeostasis (1926), and foundational publications such as "Equipping scientists for the new biology" in Nature Biotechnology (2000), which outlined the need for integrative approaches in biology, underscoring a progression from descriptive to predictive biology. Since 2000, systems biology has advanced through the integration of high-throughput omics data, computational modeling, and artificial intelligence applications, such as protein structure prediction with AlphaFold (2021) and multiscale network analyses, enabling more precise predictive models of organ system dynamics as of 2025.[15][16][17]Organ Systems in Animals

In Humans

In humans, the body is composed of 11 major organ systems, each consisting of specialized organs and tissues that collaborate to perform essential physiological functions and maintain overall homeostasis. These systems integrate to support life processes in a bipedal, endothermic mammal, where constant internal balance is critical for survival in varied environments.[1][18] The following table outlines the 11 major human organ systems, their primary functions, and key components:| Organ System | Primary Function | Key Organs and Tissues |

|---|---|---|

| Integumentary | Protects against pathogens and injury, regulates body temperature, and synthesizes vitamin D. | Skin, hair, nails, sweat glands, sebaceous glands (epithelial and connective tissues).[1] |

| Skeletal | Provides structural support, protects organs, enables movement, and stores minerals. | Bones, cartilage, ligaments, bone marrow (connective tissue).[19] |

| Muscular | Facilitates movement, maintains posture, and generates heat. | Skeletal muscles, tendons (muscle and connective tissues).[19] |

| Nervous | Detects stimuli, processes information, and coordinates responses. | Brain, spinal cord, nerves, sensory organs (nervous tissue).[1] |

| Endocrine | Regulates metabolism, growth, reproduction, and stress responses via hormones. | Pituitary gland, thyroid, adrenal glands, pancreas (glandular epithelial tissue).[1] |

| Cardiovascular (Circulatory) | Transports oxygen, nutrients, hormones, and waste products throughout the body. | Heart, blood vessels, blood (muscular, epithelial, and connective tissues).[1] |

| Lymphatic/Immune | Defends against infections, returns excess tissue fluid to circulation, and absorbs fats. | Lymph nodes, spleen, thymus, lymphatic vessels (connective tissue).[20] |

| Respiratory | Facilitates gas exchange (oxygen intake, carbon dioxide removal). | Lungs, trachea, bronchi, diaphragm (epithelial and muscular tissues).[1] |

| Digestive | Breaks down food, absorbs nutrients, and eliminates waste. | Mouth, esophagus, stomach, intestines, liver, pancreas (epithelial and muscular tissues).[21] |

| Urinary | Filters blood, removes waste, regulates fluid/electrolyte balance, and maintains pH. | Kidneys, ureters, bladder, urethra (epithelial and connective tissues).[1] |

| Reproductive | Produces gametes, supports fetal development, and facilitates species reproduction. | Ovaries/testes, uterus/prostate, associated ducts (epithelial and glandular tissues; male and female variants).[1] |