Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Music of Germany

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2025) |

| Music of Germany | ||||||||

| General topics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genres | ||||||||

| Specific forms | ||||||||

| Media and performance | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Regional music | ||||||||

|

||||||||

Germany claims some of the most renowned composers, singers, producers and performers of the world. Germany is the largest music market in Europe, and third largest in the world.[1]

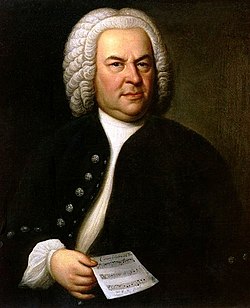

German classical music is one of the most performed in the world; German composers include some of the most accomplished, influential, and popular in history, among them Georg Friedrich Händel, Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Carl Maria von Weber, Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Richard Wagner, Johannes Brahms and Richard Strauss, many of whom were among the composers who created the field of German opera.

German popular music of the 20th and 21st century includes the movements of Neue Deutsche Welle, disco, metal/rock, pop rock, and indie. German electronic music gained global influence, with Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream being pioneer groups in this genre.[2][3] The electro and techno scene is internationally popular.

Germany hosts many large rock music festivals. The Rock am Ring and Rock im Park festival is among the largest in the world. Since around 1990, the new-old German capital Berlin has developed a diverse music and entertainment industry.

Minnesingers and Meistersingers (Man and Woman)

[edit]The beginning of what is now considered German music could be traced back to the 12th-century compositions of mystic abbess Hildegard of Bingen, who wrote a variety of hymns and other kinds of Christian music.

After Latin-language religious music had dominated for centuries, in the 12th century to the 14th centuries, Minnesinger (love poets), singing in German, spread across Germany. Minnesinger were aristocrats, traveling from court to court, who had become musicians, and their work left behind a vast body of literature, Minnelieder. The following two centuries saw the Minnesinger replaced by middle-class Meistersinger, who were often master craftsmen in their main profession, whose music was much more formalized and rule-based than that of the Minnesinger. Minnesinger and Meistersinger could be considered parallels of French troubadours and trouvère.

Among the Minnesinger, Hermann, a monk from Salzburg, deserves special note. He incorporated folk styles from the Alpine regions in his compositions. He made some primitive forays into polyphony as well. Walther von der Vogelweide and Reinmar von Hagenau are probably the most famous minnesingers from this period.

Classical music of Germany

[edit]Germans have played a leading role in the development of classical music. Many of the best classical musicians such as Bach, Händel, Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms, Wagner, Mahler, or Schoenberg (a lineage labeled the "German Stem" by Igor Stravinsky) were German. At the beginning of the 15th century, German classical music was revolutionized by Oswald von Wolkenstein, who travelled across Europe learning about classical traditions, spending time in countries like France and Italy. He brought back some techniques and styles to his homeland, and within a hundred years, Germany had begun producing composers renowned across the continent. Among the first of these composers was the organist Conrad Paumann. The largest summer festival for classical music in Germany is the Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival.

Chorale

[edit]Beginning in the 16th century, polyphony, or the intertwining of multiple melodies, arrived in Germany. Protestant chorales predominated; in contrast to Catholic music, chorale was vibrant and energetic. Composers included Dieterich Buxtehude, Heinrich Schütz and Martin Luther, leader of the Protestant Reformation. Luther happened to accompany his sung hymns with a lute, later recreated as the waldzither that became a national instrument of Germany in the 20th century.[4]

Opera

[edit]

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Die Zauberflöte (1791) is usually said to be the beginning of German opera. An earlier starting date for German opera, however, could be Heinrich Schütz's Dafne from 1627. Schütz is said to be the first great German composer before Johann Sebastian Bach, and was a major figure in 17th-century music.

In the 19th century, two figures were paramount in German opera: Carl Maria von Weber and Richard Wagner. Wagner introduced devices like the Leitmotiv, a musical theme which recurs for important characters or ideas. Wagner (and Weber) based his operas of German history and folklore, most importantly including the Ring of the Nibelung (1874). Into the 20th century, opera composers included Richard Strauss (Der Rosenkavalier) and Engelbert Humperdinck, who wrote operas meant for young audiences. Across the border in Austria, Arnold Schoenberg innovated a form of twelve-tone music that used rhythm and dissonance instead of traditional melodies and harmonies, while Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht collaborated on some of the great works of German theater, including Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny and The Three-Penny Opera.

Following the war, German composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Hans Werner Henze began experimenting electronic sounds in classical music.

Germany is also very well known for its many subsidised opera houses, such as Semperoper, Munich State Theatre and the Bayreuth Festspielhaus.

Baroque period

[edit]

Baroque music, which was the first music to use tonality in the modern sense, is also known for its ornamentation and artistic use of counterpoint. It originated in Northern Italy at the end of the 16th century, and the style migrated quickly to Germany, which was one of the most active centers of early Baroque music. Early German Baroque composers included Heinrich Schütz, Michael Praetorius, Johann Hermann Schein, and Samuel Scheidt. The culmination of the Baroque era was undoubtedly in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Friedrich Händel in the first half of the 18th century. Bach established German styles through his skill in counterpoint, harmonic and motivic organisation, and adapted rhythms, forms, and textures from Italy and France. Bach wrote numerous works, including preludes, cantatas, fugues, concertos for harpsichord, violin and wind, orchestral suites, the Brandenburg Concertos, St Matthew Passion, St John Passion and the Christmas Oratorio. Händel was a cosmopolitan composer that wrote music for virtually every genre of his time. His most famous works include the orchestral suites Water Music, Music for the Royal Fireworks and the oratorio Messiah. Another important composer was Georg Philipp Telemann, one of the most prolific musicians in history.

Classical era

[edit]

By the middle of the 18th century, the cities of Vienna, Dresden, Berlin and Mannheim had become the center for orchestral music. The Esterházy princes of Vienna, for example, were the patrons of Joseph Haydn, an Austrian who invented the classic format of the string quartet, symphony and sonata. Later that century, Vienna's Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart emerged, mixing German and Italian traditions into his own style. Mozart was a prolific and influential composer who composed over 600 works, many acknowledged as pinnacles of symphonic, concertante, chamber, operatic, and choral music. He is among the most popular of classical composers, and his influence on subsequent Western art music is profound; Ludwig van Beethoven composed his own early works in the shadow of Mozart.

Romantic era

[edit]

The following century saw two major German composers come to fame early—Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert. Beethoven, a student of Haydn's in Vienna, used unusually daring harmonies and rhythm and composed numerous pieces for piano, violin, symphonies, chamber music, string quartets and an opera. Schubert created a field of artistic, romantic poetry and music called lied; his lieder cycles included Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise.[5]

Franz Schubert was extremely prolific during his lifetime. His output consists of over six hundred secular vocal works (mainly Lieder), seven complete symphonies, sacred music, operas, incidental music and a large body of chamber and piano music. He is ranked among the greatest composers of the late Classical era and early Romantic era.

Early in the 19th century, a composer by the name of Richard Wagner was born. He was a "Musician of the Future" who disliked the strict traditionalist styles of music. He is credited with developing leitmotivs which were simple recurring themes found in his operas.

Carl Maria von Weber was a composer, conductor, pianist, guitarist[6] and critic, one of the first significant composers of the Romantic school. His operas Der Freischütz, Euryanthe and Oberon greatly influenced the development of the Romantic opera in Germany. Felix Mendelssohn was a composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. He was particularly well received in Britain as a composer, conductor and soloist. He wrote symphonies, concerti, oratorios, piano music and chamber music. Robert Schumann was a composer and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann's published compositions were written exclusively for the piano until 1840; he later composed works for piano and orchestra; many Lieder (songs for voice and piano); four symphonies; an opera; and other orchestral, choral, and chamber works. Johannes Brahms honored the music pioneered by Mozart and Beethoven and advanced his music into a Romantic idiom, in the process creating bold new approaches to harmony and melody.

The later 19th century saw Vienna continue its elevated position in European classical music, as well as a burst of popularity with Viennese waltzes. These were composed by people like Johann Strauss the Younger. Richard Strauss was a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. He is known for his operas, which include Der Rosenkavalier and Salome; his lieder, especially his Four Last Songs; and his tone poems. Strauss, along with Gustav Mahler, represents the late flowering of German Romanticism after Richard Wagner, in which pioneering subtleties of orchestration are combined with an advanced harmonic style.

20th century

[edit]

The first half of 20th century saw a split between German and Austrian music. In Vienna, Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils Alban Berg and Anton Webern moved along an increasingly avant-garde path, pioneering atonal music in 1909 and twelve-tone music in 1923. Meanwhile, composers in Berlin took a more populist route, from the cabaret-like socialist operas of Kurt Weill to the Gebrauchsmusik of Paul Hindemith. In Munich there was also Carl Orff, who was influenced by the French Impressionist composer Claude Debussy. He began to use colorful, unusual combinations of instruments in his orchestration. His most popular work is Carmina Burana.

Many composers emigrated to the United States when the Nazi Party came to power, including Schoenberg, Hindemith, and Erich Korngold. During this period, the Nazi Party embarked on a campaign to rid Germany of so-called degenerate art, which became a catch-all phrase that included music with any link to Jews, Communists, jazz, and anything else thought to be dangerous. Some figures such as Karl Amadeus Hartmann remained defiantly in Germany during the years of Nazi dominance, continually watchful of how their output might be interpreted by the authorities.

After the defeat of Nazi Germany, musicians were also subjected to the Allied policy of denazification. But here, the supposed non-political nature of music was able to excuse many, including Wilhelm Furtwängler and Herbert von Karajan (who had actually joined the Nazi Party in 1933). They both claimed to have concentrated mainly on music and to have ignored politics, but also to have conducted pieces in ways that were meant to be "gestures of defiance."[7]

In West Germany in the second half of the 20th century, German and Austrian music was largely dominated by the avant-garde. In the 60s and 70s, the Darmstadt New Music Summer School was a major center of European modernism; German composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen and Hans Werner Henze and non-German ones such as Pierre Boulez and Luciano Berio all studied there. In contrast, composers in East Germany were advised to avoid the avant-garde and to compose music in keeping with the tenets of Socialist Realism.[8] Music written in this style was supposed to advance party politics as well as be more accessible to all.[9] Hanns Eisler and Ernst Hermann Meyer were among the most famous of the first generation of GDR composers.

More recently, composers such as Helmut Lachenmann and Olga Neuwirth have extensively explored the possibilities of extended techniques. Hans Werner Henze largely dissociated himself from the Darmstadt school in favour of a more lyrical approach, and remains perhaps Germany's most lauded contemporary composer. Although he had lived outside the country since the 1950s and until his death in 2012, he remained influenced by the Germanic musical tradition.

Folk music

[edit]Germany has many unique regions with their own folk traditions of music and dance. Much of the 20th century saw German culture appropriated for the ruling powers (who fought "foreign" music at the same time).

In both East and West Germany, folk songs called "volkslieder" were taught to children; these were popular, sunny and optimistic, and had little relation to authentic German folk traditions. Inspired by American and English roots revivals, Germany underwent many of the same changes following the 1968 student revolution in West Germany, and new songs, featuring political activism and realistic joy, sadness and passion, were written and performed on the burgeoning folk scene. In East Germany, the same process did not begin until the mid-70s, where some folk musicians began incorporating revolutionary ideas in coded songs.

Popular folk songs included emigration songs from the 19th century, work songs and songs of apprentices, as well as democracy-oriented folk songs collected in the 1950s by Wolfgang Steinitz. Beginning in 1970, the Festival des politischen Liedes, an East German festival focusing on political songs, was held annually and organized (until 1980) by the FDJ (East German youth association). Musicians from up to thirty countries would participate, and, for many East Germans, it was the only exposure possible to foreign music. Among foreign musicians at the festival, some were quite renowned, including Inti-Illimani (Chile), Billy Bragg (England), Dick Gaughan (Scotland), Mercedes Sosa (Argentina) and Pete Seeger (United States), while German performers included, from both East and West, Oktoberklub, Wacholder and Hannes Wader.

Oom-pah is a kind of music played by the brass bands; it is associated with beer halls.

Bavaria and Swabia

[edit]Bavarian folk music is likely the best known outside of Germany. Yodeling and schuhplattler dancers are among the stereotyped images of German folk life, though these are only found today in the southernmost areas. Bavarian folk music has played a role in the Alpine New Wave, and produced several pioneering world music groups that fuse traditional Bavarian sounds with foreign styles.

Around the turn of the 20th century, across Europe and especially in Bavaria, many people became concerned about a loss of cultural traditions. This idea was connected to the Heimatschutz movement, which sought to protect regional identities and boundaries. What is considered Bavarian folk music in modern Germany is not the same as what Bavarian folk music was in the early 20th century; like any kind of folk or popular music, styles and traditions have evolved over time, giving birth to new forms of music.

The popularity of the Volkssänger (people's singer) in Bavaria began in the 1880s, and continued in earnest until the 1920s. Shows consisting of duets, ensemble songs, humor and parodies were popular, but the format began changing significantly following World War I. Bally Prell, the "Beauty Queen of Schneizlreuth", was emblematic of this change. She was an attractive tenor who sang lieder, chanson and opera and operetta.

Swabian folk music is most popularly represented by acts like Saiten Fell and Firlefanz and the singer-songwriter (and player of the hurdy-gurdy and guitar) Thomas Felder.

Christmas carols

[edit]Some Christmas carols familiar in English are translations of German Christmas songs (Weihnachtslieder). Pastoral Weihnachtslieder are sometimes called Hirtenlieder (shepherd songs). Three well-known examples are "O Tannenbaum" ("O Christmas Tree"), from a German folksong arranged by Ernst Anschütz; "Silent Night" ("Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht"), by the Austrians Franz Xaver Gruber and Joseph Mohr; and "Still, still, still", an Austrian folksong also from the Salzburg region, based on an 1819 melody by Süss, with the original words, slightly changed over time and location, by G. Götsch.[10]

Early popular music

[edit]

Between World War I and World War II, German music branched out to form new, more liberal and independent styles.

Kabarett

[edit]The first form of German pop music is said to be cabaret, which arose during the Weimar Republic in the 1920s as the sensual music of late-night clubs. Marlene Dietrich and Margo Lion were among the most famous performers of the period, and became associated with both humorous satire and liberal ideas.

Swing Movement

[edit]The strict regimentation of youth culture in Nazi Germany through the Hitler Youth led to the emergence of several underground protest movements, through which adolescents were able better to exert their independence.

One of these consisted mainly of upper middle class youths, who based their protest on their musical preferences, rejecting the völkisch music propagated by the Party in place of American jazz forms, especially Swing. While musical preferences are often a feature of youthful rebellion—as the history of rock and roll shows—jazz and especially Swing were particularly offensive to the Nazi hierarchy: not only did they promote sexual permissiveness, but they were also associated with the American enemy and worse, with the African race they considered inferior. On the other hand, Joseph Goebbels assembled some of the now jobless musicians from Germany and conquered countries into a big band called Charlie and His Orchestra.

Popular music from West Germany

[edit]After World War II, German pop music was greatly influenced by music from USA and Great Britain. Apart from Schlager and Liedermacher, it is necessary to distinguish between pop music in West Germany and pop music in East Germany which developed in different directions. Pop music from West Germany was often heard in East Germany, had more variety and is still present today, while East German music has had little influence.

In West Germany, English-language pop music became more and more important, and today most songs on the radio are English. Nevertheless, there is great diversity in German language pop music. There is also original English-language pop music from Germany, some having international success (for instance the Scorpions and James Last), but little with enduring broad success in Germany itself. There was very little English pop music from East Germany.

Germany has also had a thriving English-language pop scene since the end of the war, with several European and US acts topping the charts. However, Germans and German-oriented musicians have been successful as well. In the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century such European pop acts were popular as well as artists such as Sarah Connor, No Angels and Monrose who performed various types of mainstream pop in English. Many of these acts have had success all over Europe and Asia.

Schlager and Volksmusik

[edit]Schlager is a kind of vocal pop music, frequently in the form of sentimental ballads sung in German, popularized by singers such as Gitte Hænning and Rex Gildo in the 1960s, though not without a wide range within the style (Modern Schlager, Schlager-Gold, Volksmusik resp. "volkstümlicher Schlager"[clarification needed]). Schlager/Volksmusik[clarification needed] is strictly separated from international pop music and is only played on special format radio stations (sometimes mixed with international Oldies).

An important part of Schlager is volkstümliche Musik, a Schlager-like interpretation of traditional German folk themes that is very popular in German-speaking countries, especially among the older generation.

Schlager has a wide variety, and the artists with many other styles, for example: Heino, Katja Ebstein, Wolfgang Petry, Guildo Horn, Roland Kaiser, Helene Fischer and many others.

Liedermacher

[edit]Liedermacher (Songwriter) has sophisticated lyrics and is sung with minimal instrumentation, for instance only with acoustic guitar. Some songs are very political in nature. This is related to American Folk/Americana and French Chanson styles.

Famous West German Liedermacher are Reinhard Mey, Klaus Hoffmann, Hannes Wader and Konstantin Wecker. A famous East German Liedermacher was Wolf Biermann. Herman van Veen from the Netherlands was also very popular in Germany. Several Liedermacher artists also record special albums for children.

Rock

[edit]

The US military radio station American Forces Network (AFN) had a great impact on German postwar culture, starting with AFN Munich in July 1945, which was formative for the further development of German rock and jazz culture. Bill Ramsey, a senior producer at AFN Frankfurt in 1953 who came from Ohio, later became famous as a jazz and Schlager singer in Germany (while remaining almost unknown in the US).

Prior to the late 1960s however, rock music in Germany was a negligible part of the schlager genre covered by interpreters such as Peter Kraus and Ted Herold, who played rock 'n' roll standards by Little Richard or Bill Haley, sometimes translated into German.

Genuine German rock first appeared around 1968, just as the hippie countercultural explosion was peaking in the US and UK. At the time, the German musical avant-garde had been experimenting with electronic music for more than a decade, and the first German rock bands fused psychedelic rock from abroad with electronic sounds. The next few years saw the formation of a group of bands that came to be known as Krautrock or Kosmische Musik groups; these included Amon Düül, who later became the world music pioneers Dissidenten, Tangerine Dream, Popol Vuh, Can, Neu! and Faust.

Neue Deutsche Welle

[edit]

Neue Deutsche Welle (NDW) is an outgrowth of British punk rock and new wave which appeared in the mid-to late 1970s. It was arguably the first successful unique German form of Pop music, but was limited in its stylistic devices (funny lyrics and surreal composition and production). Though it was a huge success in Germany itself in the 1980s, this was not long-lasting mostly due to over-commercialization. Some artists became famous internationally like Nena, Trio, Falco (from Austria) and Joachim Witt.

Popular artists

[edit]In the 1980s and 1990s most German-language popular music was sung by male solo artists. Very popular singers are Udo Jürgens, Udo Lindenberg, Herbert Grönemeyer, Marius Müller-Westernhagen, Peter Maffay and BAP.

Udo Jürgens has maintained a large following since the late 60s and still sold out entire soccer stadiums during concerts in 2012. Grönemeyer also has managed to maintain his success up to today. Maffay developed from Schlager to rock and has a large but delimited fan base—he is seldom played on the radio. BAP, who sing in Kölsch, the dialect of their hometown Cologne, enjoy success nationwide.

Hamburger Schule

[edit]Hamburger Schule (School of Hamburg) is an underground music-movement that started in the late 1980s and was still active till around the mid-1990s. It has similar traditions as Neue Deutsche Welle and mixed all that with punk, grunge and experimental pop music. Hamburger Schule includes intellectual lyrics with postmodern theories and social criticism. Important artists are Blumfeld, Die Sterne, Die Goldenen Zitronen and Tocotronic.

Popular music from East Germany

[edit]Ostrock

[edit]By the early 1970s, experimental West German rock styles had crossed the border into East Germany and influenced the creation of an East German rock movement referred to as Ostrock. On the other side of the Iron Curtain, these bands tended to be stylistically more conservative than in the West, to have more reserved engineering, and often to include more classical and traditional structures (such as those developed by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht in their 1920s Berlin theater songs). These groups often featured poetic lyrics loaded with indirect double-meanings and deeply philosophical challenges to the status quo. As such, they were a style of Krautrock. The best-known of these bands were The Puhdys, Karat, City, Stern-Combo Meißen and Silly.

Only a few individual songs, such as "Am Fenster" by City and "Über sieben Brücken mußt Du geh'n" by Karat, found wide popularity outside the GDR. There was also a wide diversity of underground bands. Out of this scene later grew the internationally successful band Rammstein.

Popular music from reunified Germany

[edit]Modern popular music

[edit]

In the 1990s, German-language groups had only limited popularity, and only a few artists managed to be played on the radio, for example Nena, Herbert Grönemeyer, Marius Müller-Westernhagen, Die Ärzte, Rammstein, Rosenstolz or Die Prinzen.

In the mid-2000s the German band Wir sind Helden found success with a new style of German-language pop-rock. This success was followed by several other bands and artists that led to a new boom of German-language music and a broader acceptance of existing German-language recording artists.

Synthpop, Eurodance, Pop

[edit]

In the late 1980s (prior to reunification) and the 1990s, Synthpop and Eurodance became popular throughout Germany. Often, different styles were mixed in between these to attract a broad variety of audiences.

Hip Hop

[edit]Hip hop in Germany arrived in the early 1980s, and graffiti and breakdancing became well-known quickly, even in socialist East Germany.[11] German hip hop "started out as a transnational youth subculture.[12][13] The commercial success started in 1992 with the hit "Die Da" from Die Fantastischen Vier from Stuttgart. The Rödelheim Hartreim Projekt tried to establish a "gangster" rap. An early influential group was Advanced Chemistry including Torch. They sparked an interest in speaking out for the immigrants and used rap as a way to defend themselves.[14][15] Fettes Brot from Hamburg, has been successful since their beginning. They sing about funny topics, such as infidelity and boasting about their prowess with women. Whereas hip hop had a peak of success in the early first decade of the 21st century, gangster rap became a controversial part of German music and youth culture just as late as 2004 with Aggro Berlin.

Punk

[edit]Punk music in Germany has a long and diverse history. When bands like the Sex Pistols and The Clash became popular in West Germany, a number of Punk bands were formed, which led to the creation of a German punk scene. Among the first wave of bands were Male, from Düsseldorf, founded in 1976, PVC, from West Berlin, and Big Balls and the Great White Idiot, from Hamburg. Early German punk groups were heavily influenced by UK bands, often writing their lyrics in English. The main difference is that German punk bands had not yet become political.

Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s there were new movements within the German punk scene, led by labels like ZickZack Records, from Hamburg. It was during this period that the term Neue Deutsche Welle (New German Wave) was first coined by Alfred Hilsberg. Many of these bands played experimental post-punk, often using synthesizers and computers. Among them were The Nina Hagen Band, as well as Fehlfarben and Abwärts, from Hamburg. Both are still active, though they have changed their style several times. Other bands played a more aggressive style of punk rock with a clear leftist political direction influenced by earlier political rock bands like Ton Steine Scherben[16] - bands like Slime,[17] Toxoplasma, or Vorkriegsjugend[18][19] are still relevant in the German punk scene. There is a still existing scene with many only locally known independent bands that confine themselves from the bigger and more popular groups (that are often branded as "Kommerzpunk").[20]

Punkrock was outlawed in the GDR. Bands like Schleim-Keim or L'Attentat were observed and persecuted by the Stasi and could not perform in the public.[21] Music was produced in underground and exchanged on Tape, an attempt to release a split-vinyl of "Schleimkeim" and "Zwitschermaschine" failed since the latter was undercut by government agents.[22]

Nonpolitical punkrock that is also listened to by skinheads is termed as Oi!. Thematically, Oi! songs are often about alcohol, relations, and/or violence. While some Oi! Bands like "Loikaemie" did antifascist songs, there are many cases with an affliction to neonazis, with fluid borders toward right-extremist rockmusic ("Rechtsrock") within the Oi!-Scene.[23]

There are few German language bands who managed to be successful for a longer period. The best known are the punk bands Die Ärzte and Die Toten Hosen. Both were formed in the early 1980s but have very different approaches to punk. As successful as those two bands in number of sales and number one albums but much lesser accepted by the public and normally not played by German media because of their affiliation with right-wing politics but with a huge fan community were the Oi!-Band Böhse Onkelz.[24]

Heavy metal

[edit]

Germany has a long and strong history with heavy metal. It is considered by many[who?][weasel words] to be one of Europe's heaviest contributors to the scene.[citation needed] The genre is quite popular and mainstream within the country. Early hard rock/heavy metal was brought to German soil with the success of Scorpions and Accept. Germany is today known for its large metal festivals including Wacken Open Air and Summer Breeze Open Air.

Germany has a strong tradition of speed metal and power metal, with Helloween considered the “fathers of power metal”.[25] Other early speed metal bands include Running Wild, Grave Digger, Rage, and to some extent Warlock and Stormwitch. The European style of power metal, developed in Germany, was popularized by German bands like Blind Guardian, Gamma Ray, Freedom Call, Iron Savior, Avantasia, Edguy and Primal Fear gained international recognition. In many cases these bands initially started out playing speed metal, but later switched to power metal. More recently, a new generation of power metal-influenced bands like Masterplan, Orden Ogan, Kissin' Dynamite and Powerwolf is becoming more and more popular in Germany and abroad.

Running Wild are also considered a pioneer of the pirate metal genre with the release of their 1987 album Under Jolly Roger, which was one of the first pirate-themed heavy metal albums.

Three local variants of metal subgenres exist in Germany. The Teutonic thrash metal scene is represented by such groups as Kreator, Sodom, Destruction, Tankard and Exumer. Medieval metal, incorporates German traditional music with industrial metal. Notable bands include Subway to Sally, In Extremo, Corvus Corax, Saltatio Mortis and Schandmaul (the last is considered folk rock in Germany).

Germany has been a major host of the post-hardcore and metalcore scene in which various festivals and tours were in which bands from all over the world played in. Rock am Ring is held at the Nürburgring race track in Nürburg, Rhineland-Palatinate while its counterpart, Rock im Park, is held at the Zeppelinfeld in Nuremberg, Bavaria. Full Force, another huge event, hosts shows between the end of June and at the start of July in Löbnitz, Saxony. In Hamburg, the Elbriot is held annually while over in Cuxhaven, the Deichbrand takes place between July and August. During the summer, the Summer Breeze Open Air festival takes place in Dinkelsbühl, Bavaria. In Wacken, Schleswig-Holstein, the Wacken Open Air festival is held during the first weekend of August. Germany is also the birthplace of the European-wide Impericon Never Say Die! Tour that is held in the Spring all over Europe. Impericon also based their retail store in Leipzig.

Neue Deutsche Härte

[edit]

Neue Deutsche Härte (engl. "New German Hardness") is a term for an extremely popular German variant of Industrial metal. It combines the common sound of metal with elements of gothic and industrial music as well as electronic samples and is mostly sung in German. It is known for morbid and provocative lyrical themes and over-the-top stage shows often featuring fire, pyrotechnic, stunts and other special effects. It draws its audience from both the metal and goth scene. Some bands, especially Rammstein and Oomph! have gained mainstream success and, despite their lyrics being mostly in German, have also found success in non-German-speaking countries. Other famous artists include Stahlhammer (from Austria), Megaherz, Unheilig, Eisbrecher, Tanzwut, and Joachim Witt.

Medieval Metal

[edit]Medieval metal or medieval rock is a subgenre of folk metal that blends hard rock or heavy metal music with medieval folk music. Medieval metal is mostly restricted to Germany where it is known as Mittelalter-Metal or Mittelalter-Rock. The genre emerged from the middle of the 1990s with contributions from Subway to Sally, In Extremo, Schandmaul and Wolgemut. The style is characterised by the prominent use of a wide variety of traditional folk and medieval instruments.

Goth

[edit]Germany is the home of a vivid Goth scene, and has a large scene of musicians from the spectrum who are typically known as Goth musicians. Most notable artists are Lacrimosa, Lacrimas Profundere, Xmal Deutschland, Das Ich, Deine Lakaien, Illuminate, Untoten, Erben der Schöpfung (from Liechtenstein), No More, Girls Under Glass or Project Pitchfork. Leipzig is home of the largest event of this subculture worldwide called the Wave-Gotik-Treffen, regularly hosting 25,000 attendants. The WGT is closely followed by the annual M'era Luna festival in Hildesheim.

Neue Deutsche Todeskunst (engl. "New German Death Art") is a German death-obsessed Dark Wave style of music that blends Death rock, German Rock, Gothic Rock, and neo-classical music with German philosophical texts and a theatrical stage show. It is restricted to Germany where it emerged in the early 1990s from bands such as Das Ich, Lacrimosa, Relatives Menschsein and Goethes Erben. Many NDT artists are known for their use of Classical Latin.

Electronic music and techno

[edit]

Germany has the largest electronic music scene in the world[citation needed] and has a long tradition in and influence on almost all genres of electronic music. The band Kraftwerk was one of the first bands in the world to make music entirely on electronic equipment, and the band Tangerine Dream is often credited as being among the originators and primary influences of the "Berlin School" of electronic music, which would later influence trance music. Some other bands like Liaisons Dangereuses, Tyske Ludder, Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft and Die Krupps created a style later called Electronic body music. Recently a few electronica artists have become successful in the mainstream, such as Monika Kruse, Marusha, Blümchen and MIA. Artists on the cutting edge of German-language techno include Klee. Both Einstürzende Neubauten (collapsing new buildings, translated literally) and KMFDM (no pity for the majority, translated literally) are considered by many industrial and electronic music fans as the godfathers of their genre. Their sounds developed the modern styles of groups such as NIN, Marilyn Manson, Rammstein, and New Order. Einstürzende Neubauten can be recognized by their Prince-esque logo, which has been subliminally fused into several mainstream American movies (such as a tattoo in the movie Bug, directed by William Friedkin, starring Harry Connick Jr.). KMFDM has released many songs in English, making them more accessible to their huge American and worldwide audience.

In the 1990s, Germany was one of the most successful contributors to the Eurodance genre, with notable German-based acts including Real McCoy, Snap!, Culture Beat, La Bouche, Captain Jack, Captain Hollywood Project, Fun Factory, Masterboy and Haddaway.

Trance music is a style of electronic music that originated in Germany in the very late 1980s and early 1990s, upon German unification. Following the development of trance music in Germany, many Trance genres stemmed from the original trance music and most trance genres developed in Germany, most notably "Anthem trance" or also called "uplifting" or "epic" trance, progressive trance, and "Ambient trance".

Klezmer in Germany and Eastern Europe

[edit]Klezmer is a musical Jewish genre that consists of mainly instrumental songs. In Germany, Klezmer expanded significantly after the fall of the Berlin Wall in the mid-1980s.[28] As Klezmer was expanding, so was the Yiddish folk movement, and the two genres became intertwined to a certain extent. In the 1980s while Klezmer was seeing tremendous growth, many Jews in Eastern Europe turned to Klezmer as a means of understanding their communist backgrounds and showing their remembrance to those who experienced the Holocaust. Once Klezmer groups started to tour outside of Europe in the 1980s, Americans gained immediate interest in the music genre. Henry Sapoznik created the first American Klezmer band, known as Kapelye, which toured all around Europe.[28] The spread of Americans playing Klezmer brought a new tone to the genre which captured large audiences. Most American groups who played Klezmer added a hint of American rock into their performances, which was different from the traditional sound of Klezmer in Eastern Europe. It was uncomfortable at first for many of the American Klezmer bands to play in Germany because of the trauma that had occurred there. Despite Germany's background, the American Klezmer groups knew Germany was a place they had to play because of Klezmer's popularity there. Over time, Klezmer's audience expanded in Germany and the American Klezmer bands were able to adjust.

Giora Feidman is arguably one of the most influential Klezmer musicians.[citation needed] Feidman created a new perspective for Klezmer, and shared a new ideology for how the music genre could be viewed and appreciated. Feidman gained a large amount of popularity from his work on the musical play, Ghetto, which associated him and his style with the Holocaust.[28] He brought a new theme to Klezmer music which focused on the remembrance of the Holocaust, and a way of "healing" the trauma caused by the Holocaust. Feidman turned Klezmer into a form of personal expression, in which he tried to unite all people (especially the Jews and Germans) and all things through Klezmer.[28] He completely shifted the ideology of Klezmer and explained how Klezmer is in everything, it is even a way to get in touch with religion and communicate with God.[28] However, some people believe Feidman took his ideology too far and turned Klezmer into something that it never intended to become.[citation needed]

During the 1980s Klezmer underwent significant transformation, and by the middle-late 1990s Klezmer experienced a new wave of change. Klezmer became a name for many different trends far from where it originated. Klezmer was known as a political statement, a method of healing, amateur musicians getting together and playing music, a way to reconnect with lost traditions.[28]

Jazz

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Bundesverband Musikindustrie: Deutschland drittgrößter Musikmarkt weltweit". Musikindustrie.de. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Kraftwerk maintain their legacy as electro-pioneers". Deutsche Welle. 8 April 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ "Tangerine Dream's Edgar Froese, Electronic Pioneer: An Appreciation". Billboard. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ "Waldzither – Bibliography of the 19th century". Studia Instrumentorum. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

Es ist eine unbedingte Notwendigkeit, dass der Deutsche zu seinen Liedern auch ein echt deutsches Begleitinstrument besitzt. Wie der Spanier seine Gitarre (fälschlich Laute genannt), der Italiener seine Mandoline, der Engländer das Banjo, der Russe die Balalaika usw. sein Nationalinstrument nennt, so sollte der Deutsche seine Laute, die Waldzither, welche schon von Dr. Martin Luther auf der Wartburg im Thüringer Walde (daher der Name Waldzither) gepflegt wurde, zu seinem Nationalinstrument machen. – Liederheft von C. H. Böhm (Hamburg, March 1919)

- ^ John Deathridge, "The Invention of German Music, c. 1800", United and Diversity in European Culture c. 1800, ed. Tim Blanning and Hagen Schulze (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 35–60.

- ^ Max Maria Weber, Carl Maria von Weber: The Life of an Artist, translated by John Palgrave Simpson, two volumes (London: Chapman and Hall, 1865), 1:52, 62, 94, 137, 143, 152, 177, 211, 244, 271, 278; John Warrack, Carl Maria von Weber, second edition (Cambridge, New York, and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 67, 94, 107, 141.

- ^ Monod, David, Settling Scores: German music, denazification, and the Americans, 1945–1953 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2005)

- ^ Kmetz, John, et al., "Germany" Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 20 October 2008 <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40055>

- ^ Mehner, Klaus, "Deutschland ab 1945: Deutsche Demokratische Republik", vol. 2, Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, ed. Ludwig Finscher (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1995), 1188–1191

- ^ Chew, Geoffrey (2001). "Weihnachtslied". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ "Breakdance in der DDR". Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ Von Dirke, Sabine. "Hip Hop Made in Germany, From Old School to the Kanaksta Movement." German Pop Culture p. 108

- ^ Brown, Timothy S. "'Keeping it Real' in a Different 'Hood: (African-) Americanization and Hip-hop in Germany." In The Vinyl Ain't Final: Hip Hop and the Globalization of Black Popular Culture p. 147

- ^ Bennett, Andy. "Hip-Hop am Main, Rappin' on the Tyne: Hip-hop Culture as a Local Construct in Two European Cities." In That's the Joint!: The Hip-hop Studies Reader, 177–200. New York; London: Routledge, 2004, p. 183-184

- ^ Bennett, Andy. "Hip-Hop am Main, Rappin' on the Tyne: Hip-hop Culture as a Local Construct in Two European Cities." In That's the Joint!: The Hip-hop Studies Reader, p. 181-2. New York; London: Routledge, 2004.

- ^ "Am Anfang war das Feuer". www.rbb24.de (in German). Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Uthoff, Jens (3 April 2013). "Biografie der Punkband Slime: Symbol für Konflikte". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ "VORKRIEGSJUGEND -- Bier und Hartz 4". 3 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ "Vorkriegsjugend – indiepedia.de". indiepedia.de. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ "Kommerzpunk" as seen in the song "Scheiss Kommerz" by "Wohlstandskinder", https://www.magistrix.de/lyrics/The%20Wohlstandskinder/Scheiss-Kommerz-102536.html

- ^ mdr.de. "Punks in der DDR: Einmal Punk – immer Punk | MDR.DE". www.mdr.de (in German). Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Teschner, Dirk (25 October 2020), "DDR von unten", Die Tageszeitung: Taz

- ^ "Rechte Jugendliche Lebenswelten -> Milieuzeichnung: Skinheads / Oi". grauzonen.info. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ "Vom Rechtsrock zum Mainstream? - "Die Böhsen Onkelz sind keine rechte Band mehr"". Deutschlandfunk Kultur (in German). 14 June 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ "Helloween Family Tree". The Metal. 9 June 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2025.

- ^ "Stockhausen: The Father of Electronic Music".

- ^ "Kraftwerk: Pioneers of Electronic Music and Their 2025 US Tour". 11 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Gruber, Ruth Ellen (2002). Virtually Jewish : reinventing Jewish culture in Europe. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21363-7. OCLC 46937484.

References

[edit]- Painter, Karen (2007). Symphonic Aspirations: German Music and Politics, 1900–1945. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02661-2.

- Gregor, Neil (2025). The Symphony Concert in Nazi Germany. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-83910-3.

- Kater, Michael (2007). The Twisted Muse: Musicians and Their Music in the Third Reich. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509620-0.

- Laux, Karl, ed. (1960). Das Musikleben in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, 1945–1959. VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik Leipzig.

Further reading

[edit]- Helms, Siegmund, ed. (1972). Schlager in Deutschland: Beiträge zur Analyse der Popularmusik und des Musikmarktes. Breitkopf & Härtel. N.B.: Includes a bibliog. dictionary of German musicians on pp. 177–235. Without ISBN.

- Schütte, Uwe, ed. (2017). German Pop Music. A Companion. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-042571-0.

External links

[edit]- German music Brief biographies, sound samples, CDs from folk music to classical composers to contemporary rock, pop, and hip-hop German music.

- German audio music samples German music audio sound samples, CDs from folk music to classical, rock, pop, and hip-hop German music audio downloads.

- Web Portal on Music in Germany, Goethe-Institut

Music of Germany

View on GrokipediaThe music of Germany encompasses a diverse array of traditions originating from the German-speaking regions, prominently featuring foundational contributions to Western classical music through Baroque polyphony, symphonic innovation, and operatic grandeur, as well as enduring folk elements and pioneering roles in 20th- and 21st-century popular and electronic genres.[1][2][3]

Central to this heritage are composers of the Baroque era, such as Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), whose extensive oeuvre—including the Brandenburg Concertos and The Well-Tempered Clavier—exemplifies contrapuntal mastery and structural complexity that influenced subsequent musical development.[1][2] In the transition to the Classical and Romantic periods, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) composed nine symphonies that expanded orchestral forms and expressed profound emotional depth, even as he contended with progressive deafness, thereby bridging stylistic eras.[1][2] Richard Wagner (1813–1883) further transformed opera with monumental works like The Ring of the Nibelung, employing leitmotifs to weave narrative and thematic continuity, establishing Bayreuth as a dedicated festival site for his compositions.[1]

Beyond classical domains, German folk music incorporates regional brass bands, yodeling, and Schlager—a light, sentimental pop style popularized since the mid-20th century by figures like Heino—reflecting working-class and entertainment traditions.[2][3] In the post-war era, innovations in electronic music emerged with Kraftwerk's 1970s synthesizer-driven works, laying groundwork for global genres like techno, which flourished through events such as the Love Parade.[2][3] Contemporary scenes include punk and rock acts like Die Toten Hosen, hip-hop pioneers Die Fantastischen Vier, and pop stars such as Helene Fischer, underscoring Germany's ongoing influence across musical spectrums.[2][3]