Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of peace activists

View on Wikipedia

This list of peace activists includes people who have proactively advocated diplomatic, philosophical, and non-military resolution of major territorial or ideological disputes through nonviolent means and methods. Peace activists usually work with others in the overall anti-war and peace movements to focus the world's attention on what they perceive to be the irrationality of violent conflicts, decisions, and actions. They thus initiate and facilitate wide public dialogues intended to nonviolently alter long-standing societal agreements directly relating to, and held in place by, the various violent, habitual, and historically fearful thought-processes residing at the core of these conflicts, with the intention of peacefully ending the conflicts themselves.

A

[edit]

- Diane Abbott, British former Labour Party and current Independent Member of Parliament (MP) and patron of anti-war group Stop the War Coalition

- Dekha Ibrahim Abdi (1964–2011) – Kenyan peace activist, government consultant

- David Adams (born 1939) – American author and peace activist, task force chair of the United Nations International Year for the Culture of Peace, coordinator of the Culture of Peace News Network[1]

- Jane Addams (1860–1935) – American, national chairman of Woman's Peace Party, co-founder and president of Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- Ruth Adler (1944–1994) – feminist, and human rights campaigner in Scotland

- Eqbal Ahmad (1933/34–1999) – Pakistani political scientist, activist

- Martti Ahtisaari (1937–2023) – former president of Finland, active in conflict resolution

- Robert Baker Aitken (1917–2010) – Zen Buddhist Rōshi and anti-war activist, anti-nuclear testing activist, and proponent of deep ecology

- Tadatoshi Akiba (born 1942) – Japanese pacifist and nuclear disarmament advocate, former mayor of Hiroshima

- Widad Akrawi (born 1969) – Danish-Kurdish peace advocate, organizer

- Stew Albert (1939–2006) – American anti-Vietnam war activist, organizer

- Abdulkadir Yahya Ali (1957–2005) – Somali peace activist and founder of the Center for Research and Dialogue in Somalia

- B. R. Ambedkar (1891–1956) – Polymath, economist, jurist, social reformer, civil rights leader, political philosopher and revivalist of Buddhism in India

- Günther Anders (born Günther Siegmund Stern, 1902–1992) – German philosopher and a critic of nuclear weapons and nuclear deterrence

- Ghassan Andoni (born 1956) – Palestinian physicist, Christian, advocate of non-violent resistance

- Andrea Andreen (1888–1972) – Swedish physician, pacifist, and feminist

- Annot (1894–1981) – German artist, anti-war and anti-nuclear activist

- José Argüelles (1939–2011) – American New Age author and pacifist

- Émile Armand (1872–1963) – French anarchist and pacifist writer

- Émile Arnaud (1864–1921) – French peace campaigner, coined the word "pacifism"

- Klas Pontus Arnoldson (1844–1916) – Swedish pacifist, Nobel peace laureate, founder of the Swedish Peace and Arbitration Society

- Ya'akov Arnon (1913–1995) – Israeli economist, government official and pacifist

- Vittorio Arrigoni (1975–2011) – Italian reporter, anti-war activist

- Pat Arrowsmith (1930–2023) – British author and peace campaigner, co-founder of CND

- Arik Ascherman (born 1959) – Israeli-American rabbi and advocate for human rights in Israel and Palestine

- Muhammad Ashafa (born 1960) – Nigerian Imam and co-founder of the Interfaith Mediation Center of the Muslim-Christian Dialogue

- Steve Ashley (born 1946) — British singer-songwriter and peace campaigner

- Margaret Ashton (1856–1937) – British suffragist, local politician, pacifist

- Nafez Assaily (born 1956) – Palestinian sociologist and long-term advocate of nonviolence

- Julian Assange (born 1971) – founder of WikiLeaks, recipient of numerous prizes and awards, and one of only six people to be recognised with the Gold medal for Peace with Justice of the Sydney Peace Foundation

- Anita Augspurg (1857–1943) – German lawyer, writer, feminist, pacifist

- Uri Avnery (1923–2018) – Israeli writer and founder of Gush Shalom

- Mubarak Awad (born 1943) – Palestinian–American advocate of nonviolent resistance, founder of the Palestinian Centre for the Study of Nonviolence

- Ali Abu Awwad (born 1972) – Palestinian peace activist and proponent of nonviolence from Beit Ummar, founder of Taghyeer (Change) Movement

- Ayo Ayoola-Amale (born 1970) – Nigerian conflict resolution professional, ombudsman, peace builder and poet

B

[edit]

- Anton Bacalbașa (1865–1899) – Romanian Marxist and pacifist

- Eva Bacon (1909–1994) – Australian socialist, feminist, pacifist

- Gertrud Baer (1890–1981) – German Jewish peace activist, and a founding member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- Joan Baez (born 1941) – American anti-war protester, inspirational singer

- Matilde Bajer (1840–1934) – Danish feminist and peace activists

- Ella Baker (1903–1986) – African-American civil rights activist, feminist, pacifist

- Emily Greene Balch (1867–1961) – American pacifist, leader of Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, and 1946 Nobel peace laureate

- Ernesto Balducci (1922–1992) – Italian priest and peace activist

- Roger Nash Baldwin (1884–1981) – American pacifist, leader in Civil Liberties Bureau of American Union Against Militarism, supporting conscientious objectors to World War I; lifelong civil libertarian, co-founder of ACLU

- Edith Ballantyne (1922–2025) – Czech-Canadian peace activist

- Mary Barbour (1875–1958) – Scottish socialist, a founder of the Women's Peace Crusade, local councillor and magistrate; involved in the Red Clydeside movement

- Daniel Barenboim (born 1942) – pianist and conductor, joint founder – with Edward Said – of the West–Eastern Divan Orchestra, citizen of Argentina, Israel, Palestine and Spain

- Christine Ross Barker (1866–1940) – Canadian pacifist and suffragist

- Ludwig Bauer (1878–1935) – Austro-Swiss writer and pacifist

- Archibald Baxter (1881–1970) – New Zealand pacifist, socialist, and anti-war activist

- Alaide Gualberta Beccari (1842–1906) – Italian feminist, pacifist and social reformer

- Yolanda Becerra (born 1959) – Colombian feminist and peace activist

- Henriette Beenfeldt (1878–1949) – radical Danish peace activist

- Harry Belafonte (1927–2023) – American anti-war protester, performer

- Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo (born 1948) – East Timorese bishop, Nobel peace laureate

- Pope Benedict XV (1854–1922, Pope 1914–1922) – advocated peace throughout WW1; opposed aerial warfare; promoted humanitarian initiatives to protect children, prisoners of war, the wounded and missing persons

- Medea Benjamin (born 1952) – American author, organizer, co-founder of the anti-militarist Code Pink

- Tony Benn (1925–2014) – British Member of Parliament, anti-war and anti-imperialism campaigner, one of the founders of the Stop the War Coalition

- Meg Beresford (born 1937) – British activist, European Nuclear Disarmament movement

- Daniel Berrigan (1921–2016) – American anti-Vietnam war protester, Jesuit (Catholic) priest, poet, author, anti-nuke and war

- Frida Berrigan (born 1974) – American antinuclear activist

- Philip Berrigan (1923–2002) – American anti-Vietnam war protester, former Josephite (Catholic) priest, author, anti-nuke and war

- James Bevel (1936–2008) – American civil rights activist, anti-Vietnam war leader, organizer

- Vinoba Bhave (1895–1982) – Indian, Gandhian, teacher, author, organizer

- William J. Bichsel ("Bix") (1928–2015) – American Jesuit priest and antinuclear activist

- Albert Bigelow (1906–1993) – former US Navy officer turned pacifist, skipper of the first vessel to attempt disruption of the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons

- Ione Biggs (1916–2005) – American human rights activist

- Lotte Binder (1888–1930) – Transylvanian pacifist feminist

- Doris Blackburn (1889–1970) – Australian social reformer, politician, pacifist

- Janet Bloomfield (1953–2007) – British peace and disarmament campaigner, chair of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

- Bhikkhu Bodhi (born 1944) – American Theravada Buddhist monk and founder of Buddhist Global Relief[2]

- Kees Boeke (1884–1966) – Dutch educator, missionary and pacifist

- Beatrice Boeke-Cadbury (1884–1976) – English social activist, educator, Quaker missionary and pacifist

- Carl Bonnevie (1881–1972) – Norwegian jurist and peace activist

- Bono (born 1960) – Irish singer-songwriter, musician, venture capitalist, businessman, and philanthropist; born Paul David Hewson[3]

- Charles-Auguste Bontemps (1893–1981) – French anarchist, pacifist, writer

- John Bosco (1815–1888) – Italian priest, educator and author, who devoted his life to disadvantaged youth; founded the Salesians of Don Bosco and developed the nonviolent Salesian Preventive System of teaching

- Elise M. Boulding (1920–2010) – Norwegian-born American sociologist, specialising in academic peace research

- Albert Bourderon (1858–1930) – French socialist and pacifist

- Julia Boutros – Lebanese singer, humanitarian activist, and pacifist known as the "Lioness of Lebanon"

- José Bové (born 1953) – French farmer, politician, pacifist

- Norma Elizabeth Boyd (1888–1985) – African American politically active educator, children's rights proponent, pacifist

- Heloise Brainerd (1881–1969) – American women activist, pacifist

- Sophonisba Breckinridge (1866–1948) – American educator, social reformer, pacifist

- Lenni Brenner (born 1937) – American civil rights activist, opposed to the Vietnam war and strong opponent of Zionism

- Robin Briant (born 1939), New Zealand doctor and chair of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War

- Pierre Brizon (1878–1923) – French politician and pacifist

- Vera Brittain (1893–1970) – British writer, pacifist

- José Brocca (1891–1950) – Spanish activist, international delegate War Resisters' International, organiser of relief efforts during the Spanish Civil War

- Hugh Brock (1914–1985) – lifelong British pacifist and editor of Peace News between 1955 and 1964

- Peter Brock (1920–2006) – British-born Canadian pacifist historian

- Fenner Brockway (1888–1988) – British politician and Labour MP; humanist, pacifist and anti-imperialist; opposed conscription and founded the No-Conscription Fellowship in 1914; first chairperson of the War Resisters' International (1926–1934); founder member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and of the charity War on Want

- Emilia Broomé (1866–1925) – Swedish politician, feminist and peace activist

- Brigid Brophy (1929–1995) – British novelist, feminist, pacifist

- Olympia Brown (1835–1926) – American theologist, suffragist, pacifist

- Elihu Burritt (1810–1879) – American diplomat, social activist

- Caoimhe Butterly (born 1978) – Irish peace and human rights activist

- Maria C. Buțureanu (1872–1919) – Romanian educator and feminist pacifist

- Charles Roden Buxton (1875–1942) – British Liberal and later Labour MP, philanthropist and peace activist, critical of the Treaty of Versailles

C

[edit]

- Peter Ritchie Calder (1906–1982) – Scottish science journalist, socialist and peace activist

- Helen Caldicott (born 1938) – Australian physician, anti-nuclear activist, revived Physicians for Social Responsibility, campaigner against the dangers of radiation

- Hélder Câmara (1909–1999) – Brazilian archbishop, advocate of liberation theology, opponent of military dictatorship

- Marcelle Capy (1891–1962), novelist, journalist, pacifist

- Angelo Cardona (born 1997), Colombian peace activist, pacifist

- Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) – American industrialist and founder of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- April Carter (1937–2022) – British peace activist, researcher, editor

- Jimmy Carter (1924–2024) – American negotiator and former US president, organizer, international conflict resolution

- René Cassin (1887–1976) – French jurist, professor, and judge, co-wrote the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Benny Cederfeld de Simonsen (1865–1952) – Danish peace activist

- Pierre Cérésole (1879–1945) – Swiss engineer, founder of Service Civil International (SCI) or International Voluntary Service for Peace (IVSP)

- Montserrat Cervera Rodon (born 1949) – Catalan anti-militarist, feminist, and women's health activist

- Félicien Challaye (1875–1967) – French philosopher and pacifist

- Émile Chartier (1868–1951) – French philosopher, educator and pacifist

- Simone Tanner Chaumet (1916–1962) – French peace activist

- Cesar Chavez (1927–1993) – American farm worker, labor leader and civil rights activist

- Helen Chenevix (1886–1963) – Irish suffragist, trade unionist, pacifist

- Ada Nield Chew (1870–1945) – British suffragist and pacifist

- Molly Childers (1875–1964) – Irish writer, nationalist, pacifist

- Noam Chomsky (born 1928) – American linguist, philosopher, and activist

- Alice Amelia Chown (1866–1949) – Canadian feminist, pacifist and writer

- Howard Clark (1950–2013) – British peace activist, deputy editor of Peace News and Chair of War Resisters' International.

- Ramsey Clark (1927–2021) – American anti-war and anti-nuclear lawyer, activist, former U.S. Attorney General

- Helena Cobban (born 1952) – British peace activist, journalist, author

- William Sloane Coffin (1924–2006) – American cleric, anti-war activist

- James Colaianni (1922–2016) – American author, publisher, first anti-Napalm organizer

- Judy Collins (born 1939) – American anti-war singer/songwriter, protester

- Alex Comfort (1920–2000) – British scientist, physician, writer, pacifist, conscientious objector and author of The Joy of Sex

- Alecu Constantinescu (1872–1949) – Romanian trade unionist, journalist and pacifist

- Jeremy Corbyn (born 1949) – British politician, socialist, long-time anti-war, anti-imperialism and anti-racism campaigner

- Tom Cornell – American anti-war activist, initiated first anti-Vietnam War protest

- Rachel Corrie (1979–2003) – American activist for Palestinian human rights[4][5]

- David Cortright – American anti-nuclear weapon leader

- Norman Cousins (1915–1990) – American journalist, author, organizer, initiator

- Susan Crane (born c.1943) – American antinuclear activist

- Randal Cremer (1828–1908) – British trade unionist and Liberal MP (1885–1895, 1900–1908); pacifist; leading advocate for international arbitration; co-founded the Inter-Parliamentary Union and the International Arbitration League; promoted the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907; awarded Nobel Peace Prize (1903)

- Frances Crowe (1919–2019) – American pacifist, anti-nuclear power activist, draft counselor supporting conscientious objectors

- Edvin Kanka Ćudić (born 1988) – Bosnian human rights and peace activist, founder and coordinator of Association for Social Research and Communications (UDIK)

- Adam Curle (1916–2006) – Quaker peace activist; first professor of peace studies in the UK

D

[edit]

- Margaretta D'Arcy (born 1934) – Irish actress, writer and peace activist

- Mohammed Dajani Daoudi (born 1946) – Palestinian professor and peace activist

- Thora Daugaard (1874–1951) – Danish feminist, pacifist, journal editor and translator

- George Maitland Lloyd Davies (1880–1949) – Welsh pacifist and anti-war campaigner, chair of the Peace Pledge Union (1946–1949)

- Rennie Davis (1941–2021) – American anti-Vietnam war leader, organizer

- Dorothy Day (1897–1980) – American journalist, social activist, and co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement

- John Dear (born 1959) – American priest, author, and nonviolent activist

- Élisabeth Decrey Warner (born 1953) – Swiss peace activist, founder of Geneva Call

- Siri Derkert (1888–1973) – Swedish artist, pacifist and feminist

- David Dellinger (1915–2004) – American pacifist, organizer, anti-war leader

- Michael Denborough AM (1929–2014) – Australian medical researcher who founded the Nuclear Disarmament Party

- Dorothy Detzer (1893–1981) – American feminist, peace activist, U.S. secretary of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- Amanda Deyo (1838–?) – American Universalist minister, peace activist, correspondent

- Mary Dingman (1875–1961) – American social and peace activist

- Anita Dobelli (1865–?) – Italian peace activist and pacifist feminist

- Alma Dolens (1876–?) – Italian pacifist and suffragist

- Frank Dorrel – American peace activist, publisher of Addicted to War

- Ann Druyan (born 1949) – American documentary producer, vocal advocate for nuclear disarmament

- W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) – American socialist, historian, civil rights activist, peace activist and author

- Gabrielle Duchêne (1870–1954) – French feminist and pacifist

- Muriel Duckworth (1908–2009) – Canadian pacifist, feminist and community activist, founder of Nova Scotia Voice of Women for Peace

- Élie Ducommun (1833–1906) – Swiss pacifist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate

- Peggy Duff (1910–1981) – British peace activist, socialist, founder and first General Secretary of CND

- Henry Dunant (1828–1910) – Swiss businessman and social activist, founder of the Red Cross, and the joint first Nobel peace laureate (with Frédéric Passy)

- Roberta Dunbar (died 1956) – American clubwoman and peace activist

- Mel Duncan (born 1950) – American pacifist, founding executive director of Nonviolent Peaceforce

- B. D. Dykstra (1871–1955) – Dutch American pastor, writer, newspaper editor, and pacifist

E

[edit]

- Crystal Eastman (1881–1928) – American lawyer, suffragist, pacifist, journalist, co-founder of ACLU

- Shirin Ebadi (born 1947) – Iranian lawyer, human rights activist, Nobel peace laureate

- David Eberhardt (born 1941) – American antiwar activist

- Anna B. Eckstein (1868–1947) – German advocate of world peace

- Abdul Sattar Edhi (1928–2016) – Pakistani philanthropist, created the world's largest ambulance network (EDHI)

- Nikolaus Ehlen (1886–1965) – German pacifist teacher

- Hans Ehrenberg (1883–1958) – German Jewish philosopher and Christian theologian

- Albert Einstein (1879–1955) – German-born American scientist, Nobel Prize laureate in physics

- Daniel Ellsberg (1931–2023) – American anti-war whistleblower, protester, leaked the Pentagon Papers

- Robert Ellsberg (born 1955) – American religious publisher, peace activist and editor

- Scilla Elworthy (born 1943) – British Quaker, founded the Oxford Research Group and Peace Direct; advised in setting up The Elders

- James Gareth Endicott (1898–1993) – Canadian missionary, initiator, organizer, protester

- Hedy Epstein (1924–2016) – Jewish-American antiwar activist, escaped Nazi Germany on the Kindertransport; active in opposition to Israeli military policies

- Gladys del Estal (1956–1979) – Basque ecological activist, shot dead by the Guardia Civil at a protest against the Lemóniz Nuclear Power Plant and the Bardenas firing range

- Dorothy Evans (1888–1944) – Hunger-striking British suffragette, secretary of Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- Jodie Evans (born 1954) – American political activist, co-founder of Code Pink, initiator, organizer, filmmaker

- Maya Evans – British peace campaigner, arrested for reading out, near The Cenotaph, the names of British soldiers killed in Iraq

F

[edit]

- Mildred Fahrni (1900–1992) – Canadian pacifist, feminist, internationally active in the peace movement

- Andrew Feinstein (born 1964) – South African activist against the arms trade; first member of the South African Parliament to introduce a motion on the Holocaust

- Michael Ferber (born 1944) – American author, professor, anti-war activist

- Benjamin Ferencz (1920–2023) – American chief prosecutor[6] at the Einsatzgruppen Trial

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti (1919–2021) – American poet, painter, peace and social activist[7][8]

- Hermann Fernau (born 1883) – German lawyer, writer, journalist and pacifist

- Solange Fernex (1934–2006) – French peace activist and politician

- Beatrice Fihn (born 1982) – Swedish anti-nuclear activist, chairperson of International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN)

- Genevieve Fiore (1912–2002) – American women's rights and peace activist

- Ingrid Fiskaa (born 1977) – Norwegian politician and peace activist

- Jane Fonda (born 1937) – American anti-war protester, actress

- Henni Forchhammer (1863–1955) – Danish educator, feminist and pacifist

- Jim Forest (1941–2022) – American author, international secretary of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship

- Randall Forsberg (1943–2007) – led a lifetime of research and advocacy on ways to reduce the risk of war, minimize the burden of military spending, and promote democratic institutions; career started at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute in 1968

- Tom Fox (1951–2006) – American Quaker

- Diana Francis (born 1944) – British peace activist and scholar, former president of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation

- Ursula Franklin (1921–2016) – German-Canadian scientist, pacifist and feminist, whose research helped end atmospheric nuclear testing

- Marcia Freedman (1938–2021) – American-Israeli peace activist, feminist and supporter of gay rights

- Comfort Freeman – Liberian anti-war activist

- Maikki Friberg (1861–1927) – Finnish educator, journal editor, suffragist and peace activist

- Alfred Fried (1864–1921) – co-founder of German peace movement, called for world peace organization

G

[edit]

- Arun Manilal Gandhi (1934–2023) – Indian, organizer, educator, grandson of Mohandas

- Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) – Indian, writer, organizer, protester, lawyer, inspiration to movement leaders

- Alfonso García Robles (1911–1991) – Mexican diplomat, the driving force behind the Treaty of Tlatelolco, setting up a nuclear-free zone in Latin America and the Caribbean. Awarded 1982 Nobel Peace Prize

- Saadia Gardezi – Pakistani journalist and founder of Project Dastaan

- Eric Garris (born 1953) – American activist, founding webmaster of antiwar.com

- Martin Gauger (1905–1941) – German jurist and pacifist

- Leymah Gbowee (born 1972) – Liberian peace activist, organizer of women's peace movement in Liberia, awarded 2011 Nobel Peace Prize

- Aviv Geffen (born 1973) – Israeli singer and peace activist

- Everett Gendler (1928–2022) – American conservative rabbi, peace activist, writer

- Olive Gibbs (1918–1995) – British politician, founding member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and second to serve as its chair, 1964–1967

- Carol Gilbert (born 1947) – American Dominican nun and antinuclear activist

- Jeremy Gilley (born 1969) – as a result of Gilley's efforts, a General Assembly resolution was unanimously adopted by UN member states, establishing 21 September as an annual day of global ceasefire and non-violence on the UN International Day of Peace – Peace Day.

- Ann Fagan Ginger (1925–2025) – American legal scholar and teacher, activist, originator of "peace law" concept

- Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997) – American anti-war protester, writer, poet

- Igino Giordani (1894–1980) – Italian politician and cosponsor of the first Italian legislation on conscientious objection to military service, co-founder of the Catholic/ecumenical Focolare movement dedicated to unity and universal fraternity.

- Arthur Gish (1939–2010) – American public speaker and peace activist

- Bernie Glassman (1939–2018) – American Zen Buddhist roshi and founder of Zen Peacemakers

- Danny Glover (born 1946) – American actor and anti-war activist

- Vilma Glücklich (1872–1927) – Hungarian educator, pacifist and women's rights activist

- Emma Goldman (1869–1940) – Russian/American activist imprisoned in the U.S. for opposition to World War I

- Amy Goodman (born 1957) – American journalist, host of Democracy Now!

- Paul Goodman (1911–1972) – American writer, psychotherapist, social critic, anarchist philosopher and public intellectual

- Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–2022) – Russian anti-nuclear activist during and after Soviet presidency. In 1993 he launched Green Cross International and in 1995 initiated the World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates.

- Jean Goss (1912–1991) – French non-violence activist

- Hildegard Goss-Mayr (born 1930) – Austrian pacifist and theologian

- Dorothy Granada (born 1930) – American nurse, humanitarian, and peace and social justice activist who was the 1997 recipient of the International Pfeffer Peace Award

- Lorraine Granado (1948–2019) – American environmental, peace and social justice activist and organizer who co-founded the Colorado People's Environmental and Economic Network and Neighbors for a Toxic-Free Community in Denver

- Jonathan Granoff (born 1948) – Co-founder and President, Global Security Institute

- William Grassie (born 1957) – American nonviolence activist

- Jürgen Grässlin (born 1957) – teacher and activist against arms exports, especially of small arms (Heckler & Koch)

- Wavy Gravy (born 1936) – American entertainer and activist for peace

- Great Peacemaker – Native American co-founder of the Iroquois Confederacy, author Great Law of Peace

- Dick Gregory (1932–2017) – American comedian, anti-war protester

- Irene Greenwood (1898–1992) – Australian feminist, peace activist and broadcaster

- Richard Grelling (1853–1929) – German lawyer, writer and pacifist

- Ben Griffin (born 1977) – former British SAS soldier and Iraq War veteran

- Suze Groeneweg (1875–1940) – Dutch politician, feminist and pacifist

- Edward Grubb (1854–1939) – English Quaker, pacifist, active in the No-Conscription Fellowship

- Emil Grunzweig (1947–1983) – Israeli teacher and peace activist

- Gerson Gu-Konu, also Gerson Konu (1932–2006) – Peace and human rights activist from Togo

- J. Edward Guinan (1936–2014) – Founder of the Community for Creative Non-Violence

- Woody Guthrie (1912–1967) – American anti-war protester and musician, inspiration

- Tenzin Gyatso (born 1935) – 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and spiritual and formerly temporal ruler of Tibet and the Tibetan Government-in-Exile

H

[edit]

- Hugo Haase (1863–1919) – German socialist politician, jurist and pacifist

- Haggagovic (born 1984) – world traveler, peace activist, Egyptian television personality

- Lucina Hagman (1853–1946) – Finnish feminist, politician, pacifist

- Otto Hahn (1879–1968) – German chemist, discoverer of nuclear fission, Nobel Laureate, pacifist, anti-nuclear weapons and testing advocate

- Jeanne Halbwachs (1890–1980) – French pacifist, feminist and socialist

- Jeff Halper (born 1946) – American anthropologist and Israeli peace activist, founder of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions

- France Hamelin (1918–2007) – French artist, peace activist and resistance worker

- Eugénie Hamer (1865–after 1926) – Belgian peace activist and writer

- Katharine Hamnett (born 1947) – English fashion designer, known for designing T-shirts with large-print slogans against war and militarism

- Judith Hand (born 1940) – American biologist, pioneer of peace ethology

- Cornelius Bernhard Hanssen (1864–1939) – Norwegian teacher, shipowner, politician and founder of the Norwegian Peace Association

- Eline Hansen (1859–1919) – Danish feminist and peace activist

- G. Simon Harak (1948–2019) – American professor of theology, peace activist

- Keir Hardie (1856–1915) – Scottish socialist and pacifist, co-founder of Independent Labour Party and Labour Party, opposed WWI

- Florence Jaffray Harriman (1870–1967) – American suffragist, social reformer, pacifist and diplomat

- David Harris (1946–2023) – American anti-war organizer and draft resistance leader; later a journalist and author

- George Harrison (1943–2001) – English guitarist, singer-songwriter, and music and film producer, achieved international fame as the lead guitarist of The Beatles; religious and anti-war activist

- David Hartsough (born 1940) – American Quaker peace activist

- Marian Fleming Harwood (1846–1934) – Scottish-born Australian scholar, linguist, pacifist, and philanthropist

- Rhoda Hatch (1946–2020) – American peace activist who organized protests against Operation Desert Storm

- Marii Hasegawa (1918–2012) – Japanese peace activist and president (1971–1975) of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- Václav Havel (1936–2011) – Czech nonviolent writer, poet, and politician

- Brian Haw (1949–2011) – British activist, initiated and long time participant of the Parliament Square Peace Campaign

- Tom Hayden (1939–2016) – American civil rights activist, anti-Vietnam war leader, author, California politician

- Wilson A. Head (1914–1993) – American/Canadian sociologist, activist

- Larry Hebert – Active duty Senior Airman in US Air Force who went on a hunger strike in Washington, D.C., in March and April 2024 to protest U.S. military support of Israel's war in Gaza.

- Fredrik Heffermehl (1938–2023) – Norwegian jurist, writer and peace activist

- Idy Hegnauer (1909–2006) – Swiss nurse and peace activist

- Estrid Hein (1873–1956) – Danish ophthalmologist, women's rights activist and pacifist

- Arthur Henderson (1863–1935) – British politician, Labour Party leader, Foreign Secretary, chair of the Geneva Disarmament Conference, Nobel Peace Prize 1934

- Ammon Hennacy (1893–1970) – American Christian pacifist, anarchist and social activist

- Yella Hertzka (1873–1948) – Austrian peace and women's rights activist

- Alice Herz (1882–1965) – German-born feminist and anti-fascist who was the first person in the U.S. to self-immolate in protest against the Vietnam War

- Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907–1972) – Polish-born American rabbi, professor at Jewish Theological Seminary, civil rights and peace activist

- Bono (born 1960) – Irish singer-songwriter, musician, venture capitalist, businessman, and philanthropist; born Paul David Hewson

- Paul David Hewson (born 1960) – Irish singer-songwriter; see Bono above

- Hiawatha (1525–?) – Native American co-founder of the Iroguois League and co-author of the Great Law of Peace

- Sidney Hinkes (1925–2006) – British pacifist and Anglican priest

- Raichō Hiratsuka (1886–1971) – Japanese writer, political activist, feminist and pacifist

- Unutea Hirshon (born 1947) – French Polynesian anti-nuclear activist

- Emily Hobhouse (1860–1926) – British welfare campaigner, pacifist, and anti-war activist, publicly denounced the existence of the British concentration camps in South Africa

- Abbie Hoffman (1936–1989) – American anti-Vietnam war leader, co-founder of Yippies

- Ann-Margret Holmgren (1850–1940) – Swedish writer, feminist, and pacifist

- Margaret Holmes, AM (1909–2009) – Australian activist during the Vietnam War, member Anglican Pacifist Fellowship

- Robert L. Holmes (1935) – American Professor emeritus, international lecturer and theorist of nonviolence, war and morality at the University of Rochester[9][10][11]

- Inger Holmlund (1927–2019) – Swedish anti-nuclear activist

- Winifred Holtby (1898–1935) – English novelist; feminist, socialist and pacifist; active in the Independent Labour Party and League of Nations Union

- Alec Horsley (1902–1993) – British Quaker businessman, founder of the company which became Northern Foods, member of the Common Wealth Party, the Committee of 100, founding member of CND

- Ellen Hørup (1871–1953) – Danish writer, pacifist, and women's rights activist

- Nobuto Hosaka (born 1955) – Japanese politician, mayor of Setagaya in Tokyo; campaigned and won the mayor's job on an anti-nuclear platform in April 2011, just over a month after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster

- Julia Ward Howe (1819–1910) – American writer, social activist, peace advocate, author of the Mother's Day Proclamation

- Helmuth Hübener (1925–1942) – executed at the age of 17 in Nazi Germany for distributing anti-war leaflets

- Kate Hudson (born 1958) – British left-wing political activist and academic; General Secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and National Secretary of Left Unity; officer of the Stop the War Coalition since 2002

- Jessie Wallace Hughan (1875–1955) – founder of the War Resisters League; socialist and radical pacifist

- Emrys Hughes (1894–1969) – Welsh socialist member of the British Parliament, where he was an outspoken pacifist

- Laura Hughes (1886–1966) – Canadian feminist and pacifist

- Hannah Clothier Hull (1872–1958) – American Quaker activist, in the leadership of WILPF in the US

- John Hume (1937–2020) – Irish Nobel Peace Prize and Gandhi Peace Prize recipient, former leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, and former MP for Foyle 1983–2005

- John Peters Humphrey (1905–1995) – Canadian scholar, jurist, and human rights advocate, wrote the first draft of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Aldous Huxley (1894–1963) – English pacifist, anti-war and anti-conflict writer

I

[edit]

- Miguel Giménez Igualada (1888–1973) – Spanish anarchist, writer, pacifist

- Daisaku Ikeda (1928–2023) – Japanese Buddhist leader, writer, president of Soka Gakkai International, and founder of multiple educational and peace research institutions

- Kathleen Innes (1883–1967) – British educator, writer, pacifist

- Josephine Irwin (1890–1984) – American suffragist and educator

- Margaret Isely (1921–1997) – American peace activist and co-founder of WCPA

- Philip Isely (1915–2012) – American peace activist, writer and founder of WCPA & GREN

- Henriette Ith (1885–1978) – Swiss pacifist, Esperantist, author

J

[edit]

- Berthold Jacob (1898–1944) – German journalist and pacifist

- Aletta Jacobs (1854–1929) – Dutch physician, feminist and peace activist

- Martha Larsen Jahn (1875–1954) – Norwegian peace activist and feminist

- Jean Jaurès (1859–1914) – French anti-war activist, socialist leader

- Kirthi Jayakumar (born 1987) – Indian peace activist and gender equality activist, youth peace activist, peace educator and founder of The Red Elephant Foundation

- Zorica Jevremović (1948–2023) – Serbian playwright, theatre director, peace activist

- Jigonhsasee – co-founder, along with The Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha, of the Iroquois Confederacy, she became known as the Mother of Nations among the Iroquois.

- Tano Jōdai (1886–1982) – Japanese English literature professor, peace activist and university president

- John Paul II (1920–2005) – Polish Catholic pope, inspiration, advocate

- Helen John (1937–2017) – British activist, one of the first full-time members of the Greenham Common peace camp

- Hagbard Jonassen (1903–1977) – Danish botanist and peace activist

- Alice Jouenne (1873–1954) – French educator and socialist activist

- Terasawa Junsei (born 1950) – Japanese Buddhist monk and peace activist

K

[edit]

- Ekaterina Karavelova (1860–1947) – Bulgarian educator, writer, suffragist, feminist, pacifist

- Tawakkol Karman (born 1979) – Yemeni journalist, politician and human rights activist; shared 2011 Nobel Peace prize

- Randy Kehler (1944–2024) – American pacifist, anti-war activist, imprisoned draft resister, tax resister, nuclear weapons freeze organizer; inspiration to Daniel Ellsberg

- Helena Kekkonen (1926–2014) – Finnish peace activist and peace educator

- Helen Keller (1880–1968) – American activist, deafblind writer, speech "Strike Against The War" Carnegie Hall, New York 1916

- Kathy Kelly (born 1952) – American peace and anti-war activist, arrested over 60 times during protests; member and organizer of international peace teams

- Petra Kelly (1947–1992) – German politician, feminist, pacifist

- Steve Kelly (born c.1949) – American Jesuit priest and antinuclear activist

- Bruce Kent (1929–2022) – British political activist, former Catholic priest; anti-nuclear campaigner with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and president of the International Peace Bureau

- Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (1890–1988) – Pashtun independence activist, spiritual and political leader, lifelong pacifist

- Wahiduddin Khan (1925–2021) – Indian Islamic scholar and peace activist

- Abraham Yehudah Khein (1878–1957) – Ukrainian rabbi, essayist, pacifist

- Steve Killelea – initiated Global Peace Index and Institute for Economics and Peace

- Coretta Scott King (1927–2006) – American author, civil rights leader, and active in the anti-Vietnam war movement

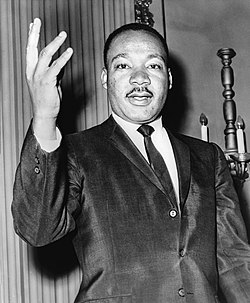

- Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968) – Civil rights leader, American anti-Vietnam war protester

- Anna Kleman (1862–1940) – Swedish suffragist and peace activist

- Michael D. Knox (born 1946) – founder of US Peace Memorial Foundation, antiwar activist, psychologist, professor

- Adam Kokesh (born 1982) – American activist, Iraq Veterans Against the War

- Annette Kolb (1870–1967) – German writer and pacifist

- Ron Kovic (born 1946) – American Vietnam war veteran, war protester

- Paul Krassner (1932–2019) – American anti-Vietnam war organizer, writer, Yippie co-founder

- Dennis Kucinich (born 1946) – former U.S. Representative from Ohio, advocate for US Department of Peace

L

[edit]

- Henri La Fontaine (1854–1943) – Belgian initiator, organizer, Nobel Peace Prize winner

- Léonie La Fontaine (1857–1949) – Belgian feminist and pacifist

- William Ladd (1778–1841) – early American activist, initiator, first president of the American Peace Society

- Benjamin Ladraa (born 1982) – Swedish activist

- Bernard Lafayette (born 1940) – American organizer, educator, initiator

- Maurice Laisant (1909–1991) – French anarchist and pacifist

- George Lakey (born 1937) – American peace activist, co-founder of the Movement for a New Society

- Grigoris Lambrakis (1912–1963) – Greek athlete, physician, politician, activist

- Gustav Landauer (1870–1919) – German writer, anarchist, pacifist

- Elena Landázuri (1888–1970) – Mexican feminist, pacifist, and social worker

- Lanza del Vasto (1901–1981) – Italian Gandhian, philosopher, poet, nonviolent activist

- Christian Lous Lange (1869–1938) – Norwegian historian and pacifist

- Alexander Langer (1946–1995) – Italian journalist, peace activist and politician

- George Lansbury (1859–1940) – British politician and Christian pacifist; Labour Party Leader (1932–1935); campaigner for social justice and women's rights and against imperialism; opposed WW1; campaigned for disarmament in the 1920s and 1930s; president of the Peace Pledge Union (1937)

- Roger Allen LaPorte (1943–1965) – American Catholic Worker who self-immolated in protest against the Vietnam War

- Bryan Law (1954–2013) – Australian non-violent activist

- Louis Lecoin (1888–1971) – French anarchist and pacifist

- Urbain Ledoux (1874–1941) – American Baháʼí diplomat and activist

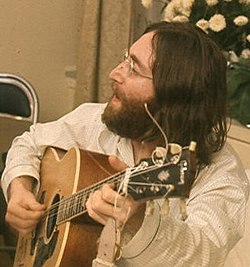

- John Lennon (1940–1980) – British singer/songwriter, anti-war protester

- Sidney Lens (1912–1986) – American anti-Vietnam war leader

- Muriel Lester (1885–1968) – British social reformer, pacifist and nonconformist; Ambassador and Secretary for the International Fellowship of Reconciliation; co-founder of the Kingsley Hall

- Captain Howard Levy – Army Captain sent to Leavenworth Military Prison for over two years for refusing an order to train Green Beret medics on their way to Vietnam.

- Bertie Lewis (1920–2010) – RAF airman who went on to become a U.K. peace campaigner

- Thomas Lewis (1940–2008) – American artist, anti-war activist with (Baltimore Four and Catonsville Nine)

- Bart de Ligt (1883–1938) – Dutch anarchist, pacifist and antimilitarist

- Georgia Lloyd (1913–1999) – American pacifist, writer

- Lola Maverick Lloyd (1875–1944) – American pacifist, suffragist, feminist

- Gabriele Moreno Locatelli (1959–1993) – Italian pacifist

- Grace Lolim (fl. 2000) – Kenyan human rights and peace activist

- James Loney (born 1964) – Canadian peace worker, kidnap victim

- Isabel Longworth (1881–1961) – Australian dentist and peace activist

- Lee Lorch (1915–2014) – Canadian mathematician and peace activist

- Fernand Loriot (1870–1932) – French teacher and pacifist

- Lowkey (born 1986) – British rapper and peace activist; opposed to the invasion of Iraq and US/UK foreign policy more generally

- David Loy (born 1947) – American scholar, author and Sanbo Kyodan Zen Buddhist teacher

- Chiara Lubich (1920–2008) – Italian Catholic mystic and founder of Focolare movement, advocate of unity amongst Christians, interreligious dialogue and cooperative relations between religious and non-religious people. Promoted "universal fraternity".

- Rae Luckock (1893–1972) – Canadian feminist, peace activist and politician

- Sigrid Helliesen Lund (1892–1987) – Norwegian peace activist

- Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919) – German Marxist and anti–war activist

- Jake Lynch (born 1964) – peace journalist, academic and writer

- Staughton Lynd (1929–2022) – American anti-Vietnam war leader

- Bradford Lyttle (born 1927) – American pacifist, writer, presidential candidate, and organizer with the Committee for Non-Violent Action

M

[edit]

- Wangari Maathai (1940–2011) – Kenyan environmental activist, Nobel peace laureate

- John Maclean (1879–1923) – Scottish radical socialist, who saw capitalism as the root of war

- Chrystal Macmillan (1872–1937) – Scottish politician, feminist, pacifist

- Salvador de Madariaga (1886–1978) – Spanish diplomat, historian and pacifist

- Carmen Magallón (born 1951) – Spanish physicist, pacifist, conducting research in support of women's advancement in science and peace

- Norman Mailer (1923–2007) – American anti-war writer, war protester

- Mairead Maguire (born 1944) – Northern Ireland peace movement, Nobel peace laureate

- Nelson Mandela (1918–2013) – South African statesman, leader in the anti-apartheid movement and post-apartheid reconciliation, founder of The Elders, inspiration

- Rosa Manus (1881–1942) – Dutch pacifist and suffragist

- Bob Marley (1945–1981) – Jamaican, inspirational anti-war singer/songwriter, inspiration

- Jacques Martin (1906–2001) – French pacifist and Protestant pastor

- Yoko Matsuoka (1916–1979) – Japanese anti-war activist, writer, and feminist

- Elizabeth McAlister (born 1939) – American former nun, peace activist, and co-founder of Jonah House

- Colman McCarthy (born 1938) – American journalist, teacher, lecturer, pacifist, progressive, anarchist, and long-time peace activist

- Emmanuel Charles McCarthy (born 1940) – American peace activist

- Eugene McCarthy (1916–2005) – U.S. presidential candidate, ran on an anti-Vietnam war agenda

- John McConnell (1915–2012) – American peace activist, creator of Earth Day

- George McGovern (1922–2012) – U.S. Senator, presidential candidate, anti-Vietnam war agenda

- Keith McHenry (born 1957) – American co-founder of Food Not Bombs

- Ciaran McKeown (1943–2019) – Irish Peace Activist

- David McReynolds (1929–2018) – leader in U.S. War Resisters League for 40 years, chair of War Resisters' International, organizer of major national anti-Vietnam War demonstrations

- David McTaggart (1932–2001) – Canadian activist against nuclear weapons testing, co-founder Greenpeace International

- Monica McWilliams (born 1954) – Northern Irish academic, peace activist, human rights defender and former politician. She was delegate at the Multi-Party Peace Negotiations, which led to the Good Friday Peace Agreement in 1998.

- Jeanne Mélin (1877–1964) – French pacifist, feminist, writer, and politician

- Adrienne van Melle-Hermans (1931–2007) – Dutch anti-nuclear peace activist, also active in ex-Yugoslavia

- Marjorie Bradford Melville (born 1929) – Member of the Catonsville Nine

- Rigoberta Menchú (born 1959) – Guatemalan indigenous rights advocate, anti-war activist, and co-founder of Nobel Women's Initiative

- Chico Mendes (1944–1988) – Brazilian environmentalist, trade union leader, and human rights advocate of peasants and indigenous peoples; assassinated in 1988

- Frank Merrick (1886–1981) – English composer, pianist, conscientious objector

- Thomas Merton (1915–1968) – American Trappist monk and poet, inspirational writer, philosopher

- Johanne Meyer (1838–1915) – pioneering Danish suffragist, pacifist, and journal editor

- Karl Meyer (born 1937) – American pacifist and tax resister

- Selma Meyer (1890–1941) – Dutch pacifist and resistance fighter of Jewish origin

- Fred Mfuranzima (born 1997) – Rwandan writer, peace activist

- Kizito Mihigo (1981–2020) – Rwandan Christian singer; genocide survivor; dedicated to forgiveness, peace and reconciliation after the 1994 genocide

- Olga Misař (1876–1950) – Austrian peace activist and writer

- Barry Mitcalfe (1930–1986) – a leader of the New Zealand movement against the Vietnam War and the New Zealand anti-nuclear movement

- Malebogo Molefhe (born c.1980) – Botswanan activist against gender-based violence

- Eva Moltesen (1871–1934) – Finnish-Danish writer and peace activist

- Roger Monclin (1903–1985) – French pacifist and anarchist

- Agda Montelius (1850–1920) – Swedish philanthropist, feminist and peace activist

- E. D. Morel (1873–1924) – British journalist, author, pacifist and politician; opposed the First World War and campaigned against slavery in the Congo

- Simonne Monet-Chartrand (1919–1993) – Canadian women's rights activist, feminist, and pacifist

- Anne Montgomery (1926–2012) – American Roman Catholic nun and antinuclear activist

- Howard Morland (born 1942) – American journalist, nuclear weapons abolitionist

- Norman Morrison (1933–1965) – American Quaker who set himself on fire in protest against the Vietnam War

- Sybil Morrison (1893–1984) – British pacifist active in the Peace Pledge Union

- Émilie de Morsier (1843–1896) – Swiss feminist, pacifist and abolitionist

- John Mott (1865–1955) – American evangelist, leader of the YMCA and WSCF, 1946 Nobel peace laureate

- Bobby Muller (born 1946) – Vietnam vet and driving force behind campaign to ban landmines, 1997 Nobel Peace Prize

- Alaa Murabit (born 1989) – Libyan Canadian physician and human rights advocate for inclusive peace and security

- Craig Murray (born 1958) – British former diplomat turned whistleblower, human rights activist and anti-war campaigner

- John Middleton Murry (1889–1957) – British author, sponsor of the Peace Pledge Union, and editor of Peace News 1940–1946

- A. J. Muste (1885–1967) – American pacifist, organizer, anti-Vietnam War leader

N

[edit]

- Fumiko Nakamura (1913–2013) – Japanese teacher and anti-war activist.

- Ottfried Nassauer (1956–2020) – German journalist and researcher, activist for arms control and against arms exports

- Abie Nathan (1927–2008) – Israeli humanitarian, founded Voice of Peace radio,[12] met with all sides of a conflict

- Ezra Nawi (1952–2021) – Israeli human rights activist and pacifist

- Paul Newman (1925–2008) – American anti-war protester, actor

- Gabriela Ngirmang (1922–2007) – Palauan peace and anti-nuclear activist

- Mrs. Ba Thanh Ngo (1931–2004) – Vietnamese anti-war and peace activist

- Elizabeth Pease Nichol (1807–1897) – suffragist, chartist, abolitionist, anti-vivisectionist, member of the Peace Society

- Georg Friedrich Nicolai (1874–1964) – German professor, famous for the book The Biology of War

- Martin Niemöller (1892–1984) – German anti-Nazi Lutheran pastor, imprisoned in Sachsenhausen and Dachau, vocal pacifist and campaigner for disarmament

- Anna T. Nilsson (1869–1947) – Swedish educator and peace activist

- Philip Noel-Baker (1889–1982) – British Labour Party politician, Olympic silver medallist, active campaigner for disarmament, Nobel Peace Prize 1959, co-founder with Fenner Brockway of the World Disarmament Campaign

- Louise Nørlund (1854–1919) – Danish feminist and peace activist

- Sari Nusseibeh (born 1949) – Palestinian activist

O

[edit]

- Phil Ochs (1940–1976) – American anti-Vietnam war singer/songwriter, initiated protest events

- Paul Oestreich (1878–1959) – German educator, board member of the "German Peace Society" in 1921– 1926

- Paul Oestreicher (born 1931) – German-born British human rights activist, Canon emeritus of Coventry Cathedral, Christian pacifist, active in post-war reconciliation

- Yoko Ono (born 1933) – Japanese anti-Vietnam war campaigner in America and Europe

- Ciaron O'Reilly (born 1960) – Australian pacifist, anti-war activist, Catholic Worker, served prison time in America and Ireland for disarming war material

- Carl von Ossietzky (1889–1938) – German pacifist, Nobel peace laureate, the opponent of Nazi rearmament

- Geoffrey Ostergaard (1926–1990) – British political scientist, academic, writer, anarchist, pacifist

- Laurence Overmire (born 1957) – American poet, author, theorist

P

[edit]

- Achola Pala – Kenyan anthropologist and sociologist

- Olof Palme (1927–1986) – Swedish prime minister, diplomat

- Ellen Palmstierna (1869–1941) – Swedish women's rights and peace activist

- Betty Papworth (1914–2008) – British communist and anti-war activist, member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and Stop the War Coalition

- Marian Cripps, Baroness Parmoor (1878–1952) – British anti-war activist

- Frédéric Passy (1822–1912) – French economist, peace activist and joint recipient (together with Henry Dunant) of the first Nobel Peace Prize (1901)

- Medha Patkar (born 1954) – Indian activist for Tribals and Dalits affected by dam projects

- Ron Paul (born 1935) – American author, physician, former U.S. congressman and presidential candidate, anti-war activist, libertarian Republican

- Ava Helen Pauling (1903–1981) – American human rights activist, feminist, pacifist

- Linus Pauling (1901–1994) – American anti-nuclear testing advocate and leader

- James Peck (1914–1993) – American anti-war and civil rights activist; advocate of nonviolent civil disobedience

- Priscilla Hannah Peckover (1833–1931) – English pacifist, nominated four times for the Nobel Peace Prize

- Mattityahu Peled (1923–1995) – Israeli scholar, officer and peace activist

- Miko Peled (born 1961) – Israeli peace activist, author of the book The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine

- Lindis Percy (born 1941) – British nurse, midwife, pacifist, founder of the Campaign for the Accountability of American Bases (CAAB)

- Frida Perlen (1870–1933) – Co-founder of the German section of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- Gabrielle Petit (1860–1952) – French feminist activist, anticlerical, libertarian socialist, newspaper editor

- Ann Pettitt (born 1947) – co-founder of Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp

- Concepción Picciotto (1936–2016) – Spanish-born anti-nuclear and anti-war protester, White House Peace Vigil

- Abbé Pierre (1912–2007) – French priest, founder of the Emmaus movement

- Ardeth Platte (1936–2020) – American Roman Catholic nun and antinuclear activist, and inspiration for Sister Jane Ingalls on Orange is the New Black.

- Peace Pilgrim (1908–1981) – American activist, walked the highways and streets of America promoting peace

- Amparo Poch y Gascón (1902–1968) – Spanish anarchist, pacifist and physician

- Ronald Podrow (1926–2004) – American pacifist and peace activist

- Paula Pogány (1884–1982) – Hungarian peace activist, suffragist, and conditioning/strength coach

- Maria Pognon (1844–1925) – French writer, feminist, suffragist and pacifist

- Joseph Polowsky (1916–1983) – American GI, advocate of better relations between the U.S. and Soviet Union between 1955 and 1983

- Pomnyun Sunim (born 1952) – South Korean author, peace activist, YouTuber

- Alberto Portugheis (born 1941) – Musician, campaigner for peace through the universal abolition of militarism

- Willemijn Posthumus-van der Goot (1897–1989) – Dutch economist, feminist, pacifist

- Vasily Pozdnyakov (1869–1921) – Russian conscientious objector and writer

- Manasi Pradhan (born 1962) – Indian activist; founder of Honour for Women National Campaign

- Devi Prasad (1921–2011) – Indian activist and artist

- Harriet Dunlop Prenter (1865/1866–1939) – Canadian feminist, pacifist

- Christoph Probst (1919–1943) – German pacifist and member of the anti-Nazi White Rose resistance

Q

[edit]- Ludwig Quidde (1858–1941) – German pacifist, 1927 Nobel peace laureate

R

[edit]

- Jim Radford (1928–2020) – British social, political and peace activist, Britain's youngest D-Day veteran, folk singer and co-organiser of the first Aldermaston March in 1958

- Gabrielle Radziwill (1877–1968) – Lithuanian pacifist, feminist and League of Nations official

- Clara Ragaz (1874–1957) – Swiss pacifist and feminist

- Abdullah Abu Rahmah – Palestinian peace activist

- Milan Rai (born 1965) – British writer and anti-war activist

- Justin Raimondo (1951–2019) – American author, anti-war activist, founder of Antiwar.com

- Cornelia Ramondt-Hirschmann (1871–1957) – Dutch teacher, feminist and pacifist

- José Ramos-Horta (born 1949) – East Timorese politician, head of the United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Guinea-Bissau, Nobel peace laureate

- Michael Randle (born 1933) – British peace activist and co-organiser of the first Aldermaston March

- Darrell Rankin (born 1957) – Canadian peace activist and Communist politician

- Jeannette Rankin (1880–1973) – first woman elected to the U.S. Congress, lifelong pacifist

- Marcus Raskin (1934–2017) – American social critic, opponent of the Vietnam war and the draft

- Dahlia Ravikovitch (1936–2005) – Israeli poet and peace activist

- Betty Reardon (1929) – founder and director of the Peace Education Center and Peace Education Graduate Degree Program at Teachers College, Columbia University

- Madeleine Rees (fl. from 1990s) – British lawyer, human right and peace proponent

- Ernie Regehr – Canadian peace researcher

- Eugen Relgis (1865–1987) – Romanian writer, pacifist and anarchist

- Patrick Reinsborough (born 1972) – American anti-war activist and author

- Maixux Rekalde (1934–2022) – Spanish Basque pacifist, activist, and journalist

- Megan Rice SHCJ (1930–2021) – Sister of the Holy Child and antinuclear disarmament activist

- Henry Richard (1812–1888) – Welsh Congregationalist minister and Member of Parliament (1868–1888), known as "the Apostle of Peace" / "Apostol Heddwch", advocate of international arbitration, secretary of the Peace Society for forty years (1848–1884)

- Lewis Fry Richardson (1881–1953) – English mathematician, physicist, pacifist, pioneer of modern mathematical techniques of weather forecasting and their application to studying the causes of war and how to prevent them

- Renate Riemeck (1920–2003) – German historian and Christian peace activist

- Paul Robeson (1898–1976) – American singer, actor, anti-fascist political activist, and vocal opponent of the Cold War

- Ellen Robinson (1840–1912) – British peace campaigner

- Julian Perry Robinson (1941–2020) – British peace researcher

- Adi Roche (born 1955) – Irish activist, chief executive of the charity Chernobyl Children International

- Douglas Roche (1929) – Canadian author, parliamentarian, diplomat, and peace activist

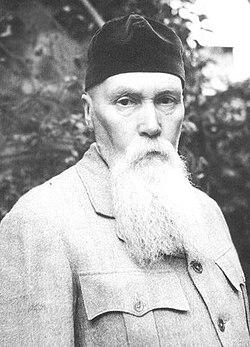

- Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947) – Russian visionary artist and mystic, creator of the Roerich Pact and Nobel Peace Prize candidate

- Amelia Rokotuivuna (1941–2005) – Fijian opponent of French nuclear tests in the Pacific

- Madeleine Rolland (1872–1960) – French translator and peace activist; sister of Romain Rolland

- Romain Rolland (1866–1944) – French dramatist, novelist, essayist, anti-war activist

- Óscar Romero (1917–1980) – Archbishop of San Salvador (Catholic), assassinated for his stand against social injustice and violence, canonized 14 October 2018

- Eleanor Roosevelt (1884–1962) – American pacifist, organized the 1948 United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights, first Gandhi Peace Award winner

- Martha Root (1872–1939) – American Baháʼí traveling teacher

- Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (1888–1973) – historian and social philosopher, whose work spanned the disciplines of history, theology, sociology, linguistics and beyond

- Franz Rosenzweig (1886–1929) – German Jewish theologian (rabi) and philosopher

- Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) – American author, political theorist, historian, staunch opponent of military interventions

- Elisabeth Rotten (1882–1964) – German-born Swiss peace activist and education reformer

- Coleen Rowley (born 1954) – ex-FBI agent, whistleblower, peace activist, and the first recipient of the Sam Adams Award

- Arundhati Roy (born 1961) – Indian writer, social critic and peace activist

- Jerry Rubin (1938–1994) – American anti-Vietnam war leader, co-founder of the Yippies

- Hagar Rublev (1954–2000) – Israeli peace activist, founder of Women in Black

- Otto Rühle (1874–1943) – German Marxist and pacifist

- Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) – British philosopher, logician, mathematician, outspoken advocate of nuclear disarmament

- Bayard Rustin (1912–1987) – American nonviolence, Anti-racism and LGBT Quaker activist

- Kathleen Rutherford (1896–1975) – British physician, philanthropist, humanitarian aid worker and peace campaigner.[13]

- Han Ryner (1861–1938) – French anarchist philosopher, pacifist

S

[edit]

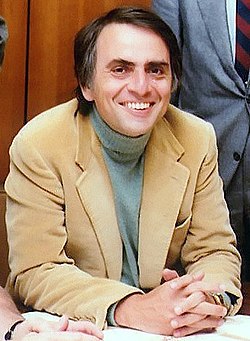

- Carl Sagan (1934–1996) – American astronomer, opposed escalation of the nuclear arms race

- Mohamed Sahnoun (1931–2018) – Algerian diplomat, peace activist, UN envoy to Somalia and to the Great Lakes region of Africa

- Edward Said (1935–2003) – Palestinian-American academic and cultural critic, joint founder with Daniel Barenboim of the West–Eastern Divan Orchestra

- Avril de Sainte-Croix (1855–1939) – French feminist, pacifist and writer

- Andrei Sakharov (1921–1989) – Russian nuclear physicist, human rights activist, and pacifist

- Ada Salter (1866–1942) – English Quaker and pacifist, a founding member of Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- Ed Sanders (born 1939) – American poet, organizer and singer, co-founder of anti-war band The Fugs

- Teresa Sarti Strada (1946–2009) – Italian teacher, pacifist and philanthropist who co-founded the NGO Emergency

- Mark Satin (born 1946) – American political theorist, anti-war proponent, draft-resistance organizer, philosopher, and writer

- Gerd Grønvold Saue (1930–2022) – Norwegian writer and peace activist

- Jean-René Saulière (1911–1999) – French anarchist and pacifist

- Henriette Sauret (1890–1976) – French feminist, author, pacifist, journalist

- Jonathan Schell (1943–2014) – American writer and campaigner against nuclear weapons, anti-war activist

- Manon Schick (born 1974) – Swiss-German journalist, human rights activist

- Sophie Scholl (1921–1943) – German student and Christian pacifist, active in the White Rose non-violent resistance movement in Nazi Germany

- Albert Schweitzer (1875–1965) – German-French activist against nuclear weapons and nuclear weapon testing whose speeches were published as Peace or Atomic War; co-founder of The Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy

- Kailash Satyarthi (born 1954) – child activist, Bachpan Bachao Aandolan, Nobel Peace Prize

- Rosika Schwimmer (1877–1948) – Hungarian feminist, pacifist and suffragist

- Molly Scott Cato (born 1963) – British green economist, Green Party politician, pacifist, and anti-nuclear campaigner

- Pete Seeger (1919–2014) – American singer, anti-war protester and inspirational singer/songwriter

- Margarethe Lenore Selenka (1860–1922) – German zoologist, feminist, and pacifist

- Suvada Selimović (born 1965), Bosnian pacifist who works to promote mutual aid between women and for those responsible for the crimes of the Bosnian War to be brought to justice

- Ravi Shankar (born 1956) – Indian spiritual teacher, humanitarian leader, and ambassador of peace

- Mary Shapard (c. 1882–1950s) – American author and peace activist who was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize; she was reportedly the first American to advocate for the formation of a "league of nations" during World War I and was also reportedly the source of the original text used by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to draft his Covenant of the League of Nations

- Jeff Sharlet (1942–1969) – American journalist and anti-Vietnam war soldier

- Gene Sharp (1928–2018) – American writer on non-violent resistance, founder of the Albert Einstein Institution

- H. James Shea Jr. (1939–1970) – American politician and anti-Vietnam War activist

- Cindy Sheehan (born 1957) – American anti-Iraq and anti-Afghanistan war leader

- Francis Sheehy-Skeffington (1878–1916) – Irish feminist, peace activist and writer

- Martin Sheen (born 1940) – American anti-war and anti-nuclear bomb protester, inspirational actor

- Nancy Shelley OAM (died 2010) – Quaker who represented the Australian peace movement at the UN in 1982

- Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) – English Romantic poet, non-violent philosopher, and inspiration

- Dick Sheppard (1880–1937) – Anglican priest and Christian pacifist, started the Peace Pledge Union

- David Dean Shulman (born 1949) – American indologist, humanist, peace activist and defender of Palestinian human rights

- Friedrich Siegmund-Schultze (1885–1969) – German theologian and pacifist

- Toma Sik (1939–2004) – Hungarian-Israeli peace activist

- Vivian Silver (1949–2023) – Canadian-Israeli peace activist, Palestinian rights activist, and women's rights activist, killed in the Hamas attack on 7 October 2023

- Jeanmarie Simpson (born 1959) – American feminist and peace activist

- Ramjee Singh (born 1927) – Indian activist, philosopher, and Gandhian

- Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (born 1938) – President of Liberia, shared 2011 Nobel Peace Prize with Tawakkol Karman and Leymah Gbowee in recognition of "their non-violent struggle for the safety of women and for women's rights to full participation in peace-building work"

- Sulak Sivaraksa (born 1932) – Thai writer and engaged Buddhist activist

- Samantha Smith (1972–1985) – American schoolgirl, young advocate of peace between Soviets and Americans

- Julia Solly (1862–1953) – British-born South African suffragist, feminist and pacifist

- Miriam Soljak (1879–1971) – New Zealand feminist, communist, unemployed-rights activist and pacifist

- Myrtle Solomon (1921–1987) – British General Secretary of the Peace Pledge Union and Chair of War Resisters' International

- Cornelio Sommaruga (1932–2024) – Swiss diplomat, president of the ICRC (1987–1999), founding President of Initiatives of Change International

- Donald Soper (1903–1998) – British Methodist minister, president of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and active in the CND

- August Spångberg (1893–1987) – Swedish member of parliament and recipient of the Eldh-Ekblad Peace Prize

- Sofia Elisabet Spångberg (1898 – 1992) – Swedish peace activist awarded King Haakon VII's Freedom Cross for her contributions to the Norwegian resistance during World War II

- Benjamin Spock (1903–1998) –American pediatrician, anti-Vietnam war protester, writer, inspiration

- Hope Squire (1878–1936) – British composer, pianist, and activist

- Helene Stähelin (1891–1970) – Swiss mathematician and peace activist

- Ringo Starr (born 1940) – British singer-songwriter, member of The Beatles

- Helen Steven (1942–2016) – Scottish Quaker and co-founder of the Scottish Centre for Nonviolence

- Cat Stevens (born 1948) – British singer-songwriter, convert to Islam, and humanitarian

- Lilian Stevenson (1870–1960) – Irish peace activist and historiographer

- Joffre Stewart (1925–2019) – American poet, anarchist, and pacifist

- Frances Benedict Stewart (fl. 1920s–1950s) – Chilean-born American sociologist, pacifist, feminist and Baháʼí Faith pioneer

- Yehuda Stolov (born 1961) – Founding director of the Interfaith Encounter Association

- Gino Strada (1948–2021) – Italian surgeon, anti-war activist, human rights activist, and founder of Emergency

- David Swanson (born 1969) – American anti-war activist, blogger and author

- Ivan Supek (1915–2007) – Croatian physicist, philosopher, peace activist and writer

- Bertha von Suttner (1843–1914) – Czech-Austrian pacifist, first woman Nobel peace laureate

- Helena Swanwick (1864–1939) – British feminist and pacifist

- Irma Szirmai (1867–1958) – Hungarian feminist and pacifist

T

[edit]

- Kathleen Tacchi-Morris (1899–1993) – British dancer, founder of Women for World Disarmament

- Nahoko Takada (1905–1991) – Japanese educator, trade unionist, politician, socialist and peace activist

- Tamanend (c. 1625–c. 1701) – known as a lover of peace and friendship, the Chief of Chiefs and Chief of the Turtle Clan of the Lenni-Lenape nation in the Delaware Valley signed the Peace Treaty with William Penn

- Guri Tambs-Lyche (1917–2008) – Norwegian women's rights activist and pacifist

- Tank Man – Stood in front of the tank during 1989 China protest

- Peter Tatchell (born 1952) – Australian-born British LGBT and human rights campaigner, founder of Christians for Peace

- Eve Tetaz (1931–2023) – retired American teacher, peace and justice activist

- Thích Nhất Hạnh (1926–2022) – Vietnamese Thiền Buddhist monk, peace activist, and inspirator of engaged Buddhism

- Jean-Marie Tjibaou (1936–1989) – Activist for the New Caledonia movement

- Thomas (1947–2009) – American anti-nuclear activist, White House peace vigil

- Ellen Thomas (born 1947) – American peace activist, White House peace vigil

- Helen Thomas (1966–1989) – Welsh peace activist who died after being hit by a police vehicle at the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp

- Dorothy Thompson (1923–2011) – English historian and peace activist

- Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) – American writer, philosopher, inspiration to movement leaders

- Sybil Thorndike (1882–1976) – British actress and pacifist; member of the Peace Pledge Union who gave readings for its benefit

- Setsuko Thurlow (born 1932) – Japanese-Canadian non-nuclear weapon activist, figure of International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN)

- Aethel Tollemache (1875–1955), British suffragette who became a pacifist, was arrested in London in 1917 (during World War I) for collecting signatures for a peace memorial

- Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) – Russian writer on nonviolence, inspiration to Gandhi, Bevel, and other movement leaders

- Aya Virginie Touré – Ivorian peace activist, proponent of non-violent resistance

- Jakow Trachtenberg (1888–1953) – Russian engineer and pacifist

- André Trocmé (1901–1971), with his wife Italian-born Magda (1901–1996) – French Protestant pacifist pastor, saved many Jews in Vichy France

- Benjamin Franklin Trueblood (1847–1916) – 19th century American writer, editor, organizer, pacifist, active in the American Peace Society

- Barbara Grace Tucker – Australian born peace activist, long time participant of the Parliament Square Peace Campaign

- Titia van der Tuuk (1854–1939) – Dutch feminist and pacifist

- Desmond Tutu (1931–2021) – South African cleric, initiator, anti-apartheid, Nobel Peace Prize 1984

- Clara Tybjerg (1864–1941) – Danish feminist, peace activist and educator

U

[edit]- Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941) – English Anglo-Catholic writer and pacifist

V

[edit]

- Jo Vallentine (born 1946) – Australian politician and peace activist

- Alfred Vanderpol (1854–1915) – French engineer, pacifist and writer

- Mordechai Vanunu (born 1954) – Israeli whistleblower

- Krista van Velzen (born 1974) – Dutch politician, pacifist and antimilitarist

- Madeleine Vernet (1878–1949) – French educator, writer and pacifist

- Llorenç Vidal Vidal (born 1936) – Spanish poet, educator and pacifist

- Stellan Vinthagen (born 1964) – Swedish anti-war and nonviolent resistance scholar-activist

- Louis Vitale (1932–2023) – American anti-war activist and Franciscan friar

- Bruno Vogel (1898–1987) – German pacifist and writer

- Kurt Vonnegut (1922–2007) – American anti-war and anti-nuclear writer and protester

W

[edit]

- Lillian Wald (1867–1940) – American nurse, writer, human rights activist, suffragist and pacifist

- Julia Grace Wales (1881–1957) – Canadian academic and pacifist

- John Wallach (1943–2002) – American journalist, founder of Seeds of Peace

- Sam Walton (born 1980s) – British Quaker, arrested (later acquitted) for attempting to disarm warplanes being used to bomb Yemen; CEO of Free Tibet

- Alyn Ware (born 1962) – New Zealand peace educator and campaigner, global coordinator for Parliamentarians for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament since 2002

- Roger Waters (born 1943) – English musician, co-founder of Pink Floyd, and anti-war activist

- Christopher Weeramantry (1926–2017) – President of the International Association of Lawyers against Nuclear Arms, former Sri Lankan Supreme Court Judge

- Matilda Widegren (1863–1938) – Swedish educator and committed peace activist

- Owen Wilkes (1940–2005) – New Zealand peace researcher and activist

- Anita Parkhurst Willcox (1892–1984) – American artist, feminist, pacifist

- Betty Williams (1943–2020) – Nobel peace laureate for her work towards bringing about reconciliation in Northern Ireland

- Jody Williams (born 1950) – American anti-landmine advocate and organizer, Nobel peace laureate

- Mary Wilhelmine Williams (1878–1944) – American historian, feminist and pacifist

- Waldo Williams (1904–1971) – Welsh language poet, Christian pacifist and Quaker, opposed the Korean War and conscription, imprisoned for refusing to pay taxes which could fund war

- George Willoughby (1914–2010) – American Quaker peace activist, co-founder of the Movement for a New Society and of Peace Brigades International

- Brian Willson (born 1941) – American veteran, peace activist and lawyer

- Dagmar Wilson (1916–2011) – founder, Women Strike for Peace

- George Winne Jr. (1947–1970) – American student who immolated himself in protest against the Vietnam War

- Lawrence S. Wittner (born 1941) – American peace historian, researcher, and movement activist

- Lilian Wolfe (1875–1974) – British anarchist, pacifist, feminist

- Walter Wolfgang (1923–2019) – German-born British activist

- Ann Wright (born 1947) – retired US army colonel and State Department official who resigned in opposition to the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, becoming a peace activist and antiwar campaigner

- Louise Wright (1861–1935) – Danish philanthropist, feminist and peace activist

- Mien van Wulfften Palthe (1875–1960) – Dutch feminist, suffragist and pacifist

- James Wuye (born 1960) – Nigerian pastor and co-founder of the Interfaith Mediation Center of the Muslim-Christian Dialogue

- David Wylie (born 1929) – American attorney, author, and peace activist

X

[edit]- Lluís Maria Xirinacs (1932–2007) – Catalan politician, writer, catholic cleric, nonviolent activist and advocate for the independence of Catalonia.

Y

[edit]

- Stephen Yang (1911–2007) – Sichuanese surgeon, educator, Quaker peace activist

- Peter Yarrow (1938–2025) – American singer-songwriter, anti-war activist

- Cheng Yen (born 1937) – Taiwanese Buddhist nun (bhikkhuni) and founder of Tzu Chi Foundation

- Ada Yonath (born 1939) – Israeli Laureate of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 2009, pacifist

- Yosano Akiko (1878–1942) – Japanese writer, feminist, pacifist

- Edip Yüksel (born 1957) – Kurdish-Turkish-American lawyer/author, Islamic peace proponent

- Malala Yousafzai (born 1997) – Pakistani peace advocate

Z

[edit]

- George Benedict Zabelka (1915–1992) – chaplain to the aircrews that dropped the nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki who later became a convert to the Christian gospel of nonviolence

- L. L. Zamenhof (1859–1917) – creator of Esperanto, the most widely used constructed international auxiliary language, fascinated by the idea of a world without war

- Alfred-Maurice de Zayas (born 1947) – Cuban-born American historian, lawyer in international law and human rights, vociferous critic of military interventions and the use of torture

- Angie Zelter (born 1951) – British anti-war and anti-nuclear activist, co-founder of Trident Ploughshares

- Clara Zetkin (1857–1933) – German Marxist, feminist and pacifist

- Else Zeuthen (1897–1975) – Danish peace activist and feminist

- Howard Zinn (1922–2010) – American historian, writer, peace advocate

- Arnold Zweig (1887–1968) – German writer and anti-war activist

See also

[edit]- Anti-nuclear protests

- Anti-war movement

- Bed-in

- Department of Peace

- Gandhi Peace Award

- Gandhi Peace Prize

- Great Law of Peace

- Indira Gandhi Prize

- League to Enforce Peace

- List of anti-war organizations

- List of anti-war songs

- List of books with anti-war themes

- List of peace prizes

- List of peace processes

- List of plays with anti-war themes

- Nobel Peace Prize laureates

- Non-interventionism

- Nonviolence

- Nonviolent resistance

- Nuclear disarmament

- Open Christmas Letter

- Otto Hahn Peace Medal

- Pacifism

- Pacifism in the United States

- Parliament Square Peace Campaign

- Peace

- Peaceworker

- Peace and conflict studies

- Peace churches

- Peace conference

- Peace congress

- Peace education

- Peacemaking

- Peace movement

- Peace Testimony

- United States Institute of Peace

- University for Peace

- War resister

- War Resisters League

- White House Peace Vigil

- World Congress of Imams and Rabbis for Peace

- World peace

- World Peace Prize

Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]Sources

[edit]- "American peace activist killed by army bulldozer in Rafah". Haaretz. 17 March 2003. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (Fall 2018). "A Call to Conscience". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- Chandran, Sudha (24 November 2000). "An Angel's Song". The Gulf Today. Sharjah.

- Colburn, Don (7 June 1988). "No More 'Evil Empire'". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- "Dr Kathleen Eleanor Hyde Rutherford MBE, MB, ChB, (1896-1975)" (PDF). Soroptimist International Great Britain & Ireland. n.d. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- Holmes, Robert L. (2013). Cicovacki, Predrag (ed.). The Ethics of Nonviolence: Essays by Robert L. Holmes. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62356-962-4.

- Holmes, Robert L. (2017). Pacifism: A Philosophy of Nonviolence. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4742-7982-6.

- "Israeli peace pioneer Abie Nathan dies aged 81". Haaretz. Associated Press. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Ludel, Wallace (23 February 2021). "Lawrence Ferlinghetti, poet, painter, and founder of San Francisco's City Lights bookstore, has died, aged 101". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

These experiences, particularly witnessing the aftermath of the Nagasaki bombing, turned Ferlinghetti into a lifelong pacifist and anti-war activist.

- "Peace Summit Award 2008: Bono". World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates. 12 December 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "Profile: Rachel Corrie". BBC News. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- "Robert Holmes Named to Mercer Brugler Professorship" (Press release). University of Rochester. 14 October 1994. Retrieved 2 November 2025.

- Tangcay, Jazz (22 January 2020). "'Prosecuting Evil' Director Barry Avrich on the Race to Complete Nuremburg Trial Doc". Variety. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Williams, Nadya (February 2021). "Lawrence Ferlinghetti: a veteran for peace". Obituary. Morning Star. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

The turning point in Ferlinghetti's life came in late September 1945 as he walked the streets of Nagasaki, Japan, six weeks after an atomic bomb was dropped on the city by his country's government. ... Among the 40,000 Japanese who were incinerated on the day of August 9 was one who was drinking tea at the time. ... Ferlinghetti picked up that person's teacup; it had flesh and bone fused into it. The cup has now sat on the mantelpiece of his home for 75-and-a-half years. ... In all his prodigiously creative works, he never missed the opportunity to chastise the absurdity of materialism, the obscenity of war and the soullessness of profit-driven destruction.

Further reading