Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

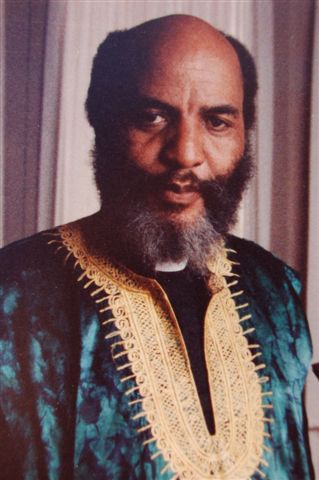

James Bevel

View on Wikipedia

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008) was an American minister and a leader and major strategist of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its director of direct action and nonviolent education, Bevel initiated, strategized, and developed SCLC's three major successes of the era:[2][3] the 1963 Birmingham Children's Crusade,[4] the 1965 Selma voting rights movement, and the 1966 Chicago open housing movement.[5] He suggested that SCLC call for and join a March on Washington in 1963[6] and strategized the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches which contributed to Congressional passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.[7]

Key Information

Prior to his time with SCLC, Bevel worked in the Nashville Student Movement, which conducted the 1960 Nashville Lunch-Counter Sit-Ins, the 1961 Open Theater Movement, and recruited students to continue the 1961 Freedom Rides after they were attacked. He helped with initiating and directing the 1961 and 1962 voting rights movement in Mississippi. In 1967, Bevel was chairman of the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam. He initiated the 1967 March on the United Nations as part of the anti-war movement.[8][9] His last major action was as co-initiator of the 1995 Day of Atonement/Million Man March in Washington, D.C. For his work, Bevel has been called the strategist and architect of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement[10] and, with Dr. King, half of the first-tier team that formulated many of the strategies and actions to gain federal legislation and social changes during the 1960s civil rights era.[8][9]

In 2005 Bevel was accused by one of his daughters of incest. Three others accused him of sexual abuse that allegedly occurred when they were children, though he was never charged with those crimes. He was tried for incest in April 2008, convicted, and sentenced to fifteen years in prison and a fine of $50,000.[11] After serving seven months, he was freed awaiting an appeal; he died of pancreatic cancer in December 2008 and was buried in Eutaw, Alabama.[12]

Early life and education (1936–1961)

[edit]Bevel was born in 1936 in Itta Bena, Mississippi, the son of Illie and Dennis Bevel.[13] He was one of 17 children and grew up in rural LeFlore County of the Mississippi Delta and in Cleveland, Ohio. He worked on a cotton plantation for a time as a youth and later in a steel mill. He was educated at segregated local schools in both Mississippi and Cleveland. After high school he served in the U.S. Navy for a time and pursued a career as a singer.[14]

Feeling an inner call to become a minister, he attended the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee from 1957 to 1961 and became a Baptist preacher. He joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.[14] While at seminary, Bevel reread Leo Tolstoy's 1894 book The Kingdom of God Is Within You, which had previously inspired his decision to leave the military. Bevel also read several of Mohandas Gandhi's books and newspapers while taking off-campus workshops on Gandhi's philosophy and nonviolent techniques taught by James Lawson of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Bevel also attended workshops at the Highlander Folk School taught by its founder, Myles Horton, who emphasized grassroots organizing.[13]

Leading the movements (1960s)

[edit]Nashville Student Movement (1960–1961) and SNCC

[edit]In 1960, along with James Lawson's and Myles Horton's students Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, Diane Nash, C.T. Vivian and others, Bevel participated in the Nashville Sit-In Movement organized by Nash, whom he would later marry, to desegregate the city's lunch counters. After the success of this action, and with the aid of SCLC's Ella Baker, activist students from Nashville and across the South developed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). While working on SNCC's commitment to desegregate theaters, Bevel successfully directed the 1961 Nashville Open Theater Movement.[15]

The Open Theater Movement, led by Bevel, had success in Nashville, the only city in the country where SCLC activists had organized such an action. In this same period, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had organized the 1961 Freedom Rides through the Deep South to challenge southern state laws and practices that interstate buses and their facilities remain segregated despite federal laws for equal treatment. After buses and riders were severely attacked, including a firebombing of a bus and beatings with police complicity in Birmingham, Alabama, CORE suspended the rides.[16] Diane Nash, the Nashville Student Movement's chairman, urged the group to continue the Freedom Rides, and called for college volunteers from Fisk and other universities across the South. Bevel selected the student teams for the buses. He and the others were arrested after they arrived in Jackson, Mississippi and tried to desegregate the waiting rooms in the bus terminal. Eventually, the Freedom Riders reached their goal of New Orleans, Louisiana, generating nationwide coverage of the violence to maintain Jim Crow and white supremacy in the South.[17]

While in the Jackson jail, Bevel and Bernard Lafayette initiated the Mississippi Voting Rights Movement. They, Nash, and others stayed in Mississippi to work on grassroots organizing.[18] Activists encountered severe violence at that time and retreated to regroup. Later efforts in Mississippi developed as Freedom Summer in 1964, when extensive voter education and registration efforts took place. Lafayette and his wife, Colia Lidell, also opened an SNCC project in Selma, Alabama, to assist the work of local organizers such as Amelia Boynton.

Bevel and King join forces (1962)

[edit]In 1962, Bevel was invited to meet in Atlanta with Martin Luther King Jr, a minister who was head of the SCLC. At that meeting, which had been suggested by James Lawson, Bevel and King agreed to work together on an equal basis, with neither having veto power over the other, on projects under the auspices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). They agreed to work until they had ended segregation, obtained voting rights, and ensured that all American children had a quality education. They agreed to continue until they had achieved these goals, and to ask for funding from the SCLC only if the group was involved in organizing a movement.[8][9]

Bevel soon became SCLC's director of direct action and director of nonviolent education to augment King's positions as SCLC's chairman and spokesperson.[citation needed]

Birmingham Children's Crusade (1963)

[edit]

In 1963, SCLC agreed to assist its co-founder, Fred Shuttlesworth, and others in their work on desegregating retail businesses and jobs in Birmingham, Alabama, where discussion and negotiations with city officials had yielded few results. Weeks of demonstrations and marches resulted in King, Ralph Abernathy, and Shuttlesworth being arrested and jailed. King wanted to fill the jails with protesters, but it was becoming more difficult to find adults to march. They were severely penalized for missing work and were trying to support their families.

Bevel suggested recruiting students in the campaign.[14] King was initially reluctant, but agreed. Bevel spent weeks developing strategy, recruiting and educating students in the philosophy and techniques of nonviolence. Their meetings occurred at Birmingham's 16th Street Baptist Church, and it was from there that Bevel directed the students, 50 at a time, to peacefully walk to Birmingham's City Hall to talk to Mayor Art Hanes about segregation in the city. Almost 1,000 students were arrested on the first day. The following day, when more students arrived at the church and started to walk to city hall, Eugene "Bull" Connor, City Commissioner of Public Safety, ordered that German Shepherd dogs and high-pressure fire hoses be used to stop them. The national and international media covered the story, and photographs of the force used against schoolchildren generated public outrage against the city and its officials.

Dispute with President John F. Kennedy and the March on Washington

[edit]During what was later called the Birmingham Children's Crusade, President John F. Kennedy asked King to stop using children in the campaign. King asked Bevel to refrain from recruiting students, and Bevel instead said that he would organize the children to march to Washington D.C. to meet with Kennedy about segregation, and King agreed.[6] Bevel went to the children and asked them to prepare to take to the highways for a march on Washington, with the goal of questioning the President about his plans to end legal segregation in America.[6] Hearing of this plan, and in response to the city's violent treatment of the students, the Kennedy administration asked SCLC's leaders what they wanted in a comprehensive civil rights bill. Kennedy's staff, who were already drafting one, came to an agreement on its contents with the SCLC's leadership. Bevel then called off plans for the children's march.

Alabama Project and the Selma Voting Rights Movement (1965)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

In September 1963, a bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham killed four young girls attending Sunday School and damaged the church. It was later proven that a Ku Klux Klan chapter was responsible. Bevel proposed organizing the Alabama Voting Rights Project, and co-wrote the project proposal with his wife Diane Nash.[19] They moved to Alabama to implement the project along with Birmingham student activist James Orange.

At the turn of the 20th century, southern state legislatures had passed new constitutions and laws that effectively disenfranchised most blacks. Practices such as requiring payment of poll taxes and literacy tests administered in a discriminatory way by white officials maintained the exclusion of blacks from the political system in the 1960s. SNCC had been conducting a Voting Rights Project (headed by Prathia Hall and Worth Long) since the early 1960s, meeting with violence in Alabama. In late 1963 Bevel, Nash, and Orange also worked with local grassroots organizations to educate blacks and support them in trying to gain registration as voters, but made little progress. They invited King and other SCLC leaders to Selma to develop larger protests and actions, and work alongside Bevel's and Nash's Alabama Project.[5] Together the groups became collectively known as the Selma Voting Rights Movement, with James Bevel as its director.

The Movement began to stage regular marches to the county courthouse, which had limited hours for blacks to register as voters. Some protesters were jailed, but the movement kept the pressure on. On February 16, 1965, Jimmie Lee Jackson, his mother, and grandfather took part in a nighttime march led by C. T. Vivian to protest the related jailing of activist James Orange in Marion, Alabama. The street lights were turned off by Alabama State Troopers who attacked the protesters. In the melee, Jackson, 26, was shot in the stomach while defending his mother from an attack. He died a few days later.

Bevel and others were grieved and outraged. He suggested a march from Selma to Montgomery, the capital, to protest Jackson's death and press Governor George Wallace to support voting rights for African Americans.[9] As the first march reached the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge and passed out of the city, they were attacked by county police and Alabama State Troopers. The large group were bludgeoned and tear-gassed in what became known as "Bloody Sunday". SNCC chairman John Lewis and Amelia Boynton were both injured.

In March 1965 protesters made a symbolic march, inspired by a fiery speech by Bevel at Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church, where much organizing was done.[14] The protesters were under an injunction, so they remained within city limits. Organizers appealed to the federal court against an injunction by the state against marching to complete their planned march to the capital. Judge Frank Johnson approved a public march. Following the nationwide publicity generated by Jackson's death and the previous attack on peaceful marchers, hundreds of religious, labor and civic leaders, many celebrities, and activists and citizens of many ethnicities traveled to Selma to join the march. By the time they entered Montgomery 54 miles away, the marchers were thousands strong. Even before the final march occurred, President Lyndon Johnson had gone on national television to address a joint session of Congress, appealing for passage of his administration-backed comprehensive Voting Rights Act.

In 1965 SCLC gave its highest honor, the Rosa Parks Award, to James Bevel and Diane Nash for their work on the Alabama Voting Rights Project.

Chicago Freedom Movement (1965–1966) and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement (1967)

[edit]In 1966, Bevel chose Chicago as the site of SCLC's long-awaited Northern Campaign.[20] He worked to create tenant unions and build grassroots action to "end" slums. From previous discussions with King, and from work of American Friends Service Committee activist Bill Moyer, Bevel organized, and directed the Chicago open housing movement. Housing in the area was segregated in a de facto way, enforced by covenants and real estate practices. This movement ended within a Summit Conference that included Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley.

As the Chicago movement neared its conclusion A. J. Muste, David Dellinger, representatives of North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh, and others asked Bevel to take over the directorship of the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam.[21] Bevel was influential in gaining King's support for the anti-war movement,[14] and with King agreeing to participate as a speaker, Bevel agreed to lead the antiwar effort.

He renamed the organization the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, recruited members of many diverse groups, and organized the April 15, 1967 march from Central Park to the United Nations Building in New York City. Originally planned as a rally in Central Park, the United Nations Anti-Vietnam War March became the largest demonstration in American history to that date.[citation needed] During his speech to the crowd that day, Bevel called for a larger march in Washington D.C., a plan that evolved into the October 1967 March on the Pentagon. This rally was attended by tens of thousands of peace activists who followed the growing counterculture movement.[22]

Memphis sanitation strike (1968)

[edit]Although he opposed King's and SCLC's participation in it, Bevel, along with King and Ralph Abernathy, helped lead the Memphis sanitation workers' strike by organizing the protest and work stoppage.[23][24] The strike began on February 12, 1968, after two black sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a malfunctioning garbage compactor truck on February 1, and the city's discriminatory response to the deaths catalyzed over 1,300 sanitation workers to walk off their jobs.[23]

King arrived at Memphis on March 18, 1968, to address a crowd of approximately 25,000 people, the largest indoor gathering the civil rights movement had ever seen, where he encouraged supporters to engage in a citywide work stoppage and promised to return on March 22 to lead a protest march through the city.[23] When King left Memphis the following day, Bevel and Ralph Abernathy remained in the city to help organize the planned protest and work stoppage.[23][25] Their organizing efforts included coordinating with local leadership, planning demonstration logistics, and building community support for the March 22 citywide action.

The originally planned March 22 demonstration was postponed due to a massive snowstorm that prevented King's return to Memphis, forcing organizers to reschedule the march for March 28.[26] On March 28, the demonstration turned violent when some participants engaged in window-breaking and looting, resulting in the death of 16-year-old Larry Payne and injuries to approximately 60 people.[27][28]

Due to the violence that ensued during the strike, the city of Memphis filed a formal District Court complaint against King, Hosea Williams, James Bevel, James Orange, Ralph Abernathy, and Bernard Lee, all members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) staff.[27][28] The legal complaint accused them of engaging in a conspiracy to incite riots or breaches of the peace. The strike ultimately concluded on April 16, 1968, twelve days after King's assassination on April 4 at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, with the city recognizing the union and agreeing to wage increases for the sanitation workers.[23]

King assassination (April 4, 1968)

[edit]In 1968 Dr. King objected to Bevel and other SCLC organizers' opposition to proceeding with King's planned Poor People's Campaign. Historian Taylor Branch quotes King in At Canaan's Edge: America in the King Years, 1965–1968 (2006) as saying that "Andrew Young had given in to doubt, Bevel to brains, and Jackson to ambition", and said that the movement had made them, and now they were using the movement to promote themselves. "He confronted Bevel, who had been a mentor to Jackson and Young, as 'a genius who flummoxed his own heart'. 'You don't like to work on anything that isn't your own idea,' King said, 'Bevel, I think you owe me one.'"[29]

Bevel was in the parking lot of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis and witnessed King's assassination on April 4, 1968. He reminded SCLC's executive board and staff that evening that King had left "marching orders" that, if anything should happen to him, he intended for Abernathy to take his place as SCLC's chairman.[30] Bevel continued to oppose the Poor People's Campaign, but served as its director of nonviolent education.

For Bevel, King's assassination "represented a great personal crisis."[31] In particular, he claimed that James Earl Ray had not killed King and he offered to defend Ray in court; also campaigning for Ray's release from prison, even though Ray pled guilty to the crime.[14]

Bevel was not the only prominent civil rights leader who believed Ray was a convenient scapegoat for Dr. King’s murder. The wife and family of Dr. King filed and won a civil suit in 1999 proving Ray had been framed by a group of murderous conspirators, including federal government agencies. Though the lawsuit remains largely ignored in media, the Loyd Jowers trial is well documented.

Bevel in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s

[edit]SCLC's board of directors removed Bevel from his leadership positions in 1970. He had become "increasingly overbearing" in King's absence, and acted with "an almost studied arrogance," though the direct cause of his removal was the result of an incident at Spelman College, in Atlanta.[31]

Also in 1970, Bevel created the Making of the Man Clinic.[32]

In the 1980s, Bevel supported Ronald Reagan as president.[14] In 1986, Bevel, Chicago alderman Danny K. Davis, singer-songwriter Kristin Lems, and others participated in an unsuccessful project of creating a summit in Chicago for Gorbachev and Reagan to bring peace and resolution to the ongoing Cold War.[33]

In 1989, Bevel and Abernathy organized the National Committee Against Religious Bigotry and Racism. This was financially backed by the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon, which appeared to be trying to improve its controversial image by allying with such respected leaders.[34][35] A year earlier, Bevel had denounced the deprogramming of a Moon follower and called for the protection of religious freedom. He also supported Unification Church members in their protest against news media use of the word "Moonie", which they considered offensive.[36][37]

Bevel moved to Omaha, Nebraska, in November 1990 as the leader of the "Citizens Fact-Finding Commission to Investigate Human Rights Violations of Children in Nebraska", a group organized by the Schiller Institute.[38] The commission was associated with conspiracy theorist Lyndon LaRouche, and sought to persuade the state legislature to reopen its two-year investigation into the Franklin child prostitution ring allegations. Bevel never submitted the collected petitions and left the state the following summer.[39]

In 1992, Bevel ran on LaRouche's ticket as the vice presidential candidate. At the time, he was living and working in Leesburg, Virginia, near LaRouche's headquarters. LaRouche, characterized as a perennial candidate, was serving a prison sentence for mail fraud and tax evasion.[40] He engaged in LaRouche seminars on issues including "Is the Anti Defamation League the new KKK?"[41] When Bevel introduced LaRouche at a convention of the 1996 National African American Leadership Summit, both men were booed off the stage. A fight broke out between LaRouche supporters and black nationalists.[42]

Criminal charges (2007–2008)

[edit]In May 2007, Bevel was arrested in Alabama on a charge of incest committed sometime between October 1992 and October 1994 in Loudoun County, Virginia. At the time, Bevel was living in Leesburg, Virginia, and working with LaRouche's group, whose international headquarters was a few blocks from Bevel's apartment.

The accuser was one of his daughters, who was 13–15 years old at the time and lived with him. At a family reunion, three other daughters had also alleged that Bevel sexually abused them.[14] Virginia had no statute of limitations for the offense of incest. Bevel pleaded not guilty to the one count charged and maintained his innocence. During his four-day trial in 2008, the accusing daughter testified that she was repeatedly molested by him, beginning when she was six years old.[43]

During the trial, prosecutors presented key evidence: a 2005 police-sting telephone call recorded by the Leesburg police without Bevel's knowledge. During that 90-minute call, Bevel's daughter asked him why he had sex with her the one time in 1993, and she asked him why he wanted her to use a vaginal douche afterward. Bevel said that he had no interest in getting her pregnant. At trial, Bevel denied committing the sexual act and his recorded statement was used against him.[44]

On April 10, 2008, after a three-hour deliberation, the jury convicted Bevel of incest. His bond was revoked and he was taken into custody.[45] On October 15, 2008, the judge sentenced him, based on the jury's recommendation, to 15 years in prison and fined him $50,000. After the verdict, Bevel claimed that the charges were part of a conspiracy to destroy his reputation, and said that he might appeal. He received an appeal bond on November 4, 2008, and was released from jail three days later, after a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.[14] Six weeks later he died of cancer, at the age of 72, in Springfield, Virginia.[46]

Bevel's attorney requested that the Court of Appeals of Virginia abate the conviction on account of Bevel's death. The Court of Appeals remanded the case to the trial court to determine whether there was good cause not to abate the conviction. The trial court found that abating the conviction would deny the victim the closure that she sought and denied the motion to abate. The Court of Appeals affirmed this judgment.[47] Bevel's attorney appealed the denial of the abatement motion to the Supreme Court of Virginia. In an opinion issued November 4, 2011, the commonwealth's Supreme Court held that abatement of criminal convictions was not available in Virginia under the circumstances of Bevel's case. Because the executor of Bevel's estate had not sought to prosecute the appeal, the Court affirmed the dismissal of his appeal as moot.[48]

Marriage and family

[edit]In 1961, Bevel married activist Diane Nash after he completed his seminary studies. They worked together on civil rights, and had a daughter and son together. They divorced after seven years.[49] He married two other women in the following decades, and had told the court during his incest case that he had 16 children born of seven women.[14]

Cultural impact

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Faithful to my Father's Dream, Enoch Bevel. dissentmagazine.org.

- ^ Kryn, Randall L. (1989). "James L. Bevel; The Strategist of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement". In Garrow, David (ed.). We Shall Overcome. Brooklyn, New York: Carlson Publishing Company. p. 325. ISBN 978-0926019027.

- ^ Kryn, Randy (October 2005). "Movement Revision Research Summary Regarding James Bevel". middlebury.edu. Middlebury, Vermont: Middlebury College. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ Thomas Ricks, NPR interview, October 4, 2022

- ^ a b Kryn in Garrow, 1989.

- ^ a b c Kryn in Garrow, 1989, p. 533.

- ^ Fager, Charles (July 1985). Selma, 1965: The March That Changed the South (2nd ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-0405-7.

- ^ a b c Kryn in Garrow, 1989, pp. 517, 523–24.

- ^ a b c d Kryn, 2005.

- ^ Kryn in Garrow, 1989, title & p. 532.

- ^ Barakat, Matthew (April 10, 2008). "Civil Rights Leader Convicted of Incest". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 26, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ Morton, Jason (December 29, 2008). "Controversial civil rights leader buried in Eutaw". The Tuscaloosa News. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Halberstam, David (2012). The Children. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1-4532-8613-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Weber, Bruce (December 23, 2008). "James L. Bevel, 72, an Adviser to Dr. King, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2002). SNCC: The New Abolitionists. Cambridge, Massachusetts: South End Press.

- ^ Peck, Jim (May 1961). "Freedom Ride" (PDF). CORE-Lator.

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2007). Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Hogan, Wesley (December 1, 2013). "In peace and freedom: my journey in Selma". The Sixties. 6 (2): 240–242. doi:10.1080/17541328.2014.898510. ISSN 1754-1328. S2CID 143987916.

- ^ Civil rights teaching, Alabama Project

- ^ Kryn in Garrow, 1989, pp. 521–522.

- ^ Kryn in Garrow, 1989, pp. 533–534.

- ^ "The Day The Pentagon Was Supposed To Lift Off Into Space" Archived 2005-12-19 at the Wayback Machine, American Heritage magazine, 21 October 2005, Accessed September 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike". The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute, Stanford University. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ "Memphis Sanitation Strike (1968)". BlackPast.org. February 6, 2024. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ "Memphis Sanitation Strike (1968)". BlackPast.org. February 6, 2024. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ "Memphis Sanitation Strike (1968)". BlackPast.org. February 6, 2024. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ a b "Martin Luther King, Jr., and Memphis Sanitation Workers". National Archives. September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ a b "The 50th Anniversary of the Sanitation Workers Strike that cleaned up Memphis". Chicago Crusader. January 18, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2025.

- ^ Taylor Branch, At Canaan's Edge, 2006

- ^ Kryn in Garrow, 1989, p. 524.

- ^ a b Mack, Adam (2003). "No "Illusion of Separation": James L. Bevel, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Vietnam War". Peace & Change. 28 (1): 108–133. doi:10.1111/1468-0130.00255. ISSN 1468-0130.

- ^ "Reverend James Bevel's Biography".

- ^ Lipinski, Ann Marie (November 25, 1986), "Reykjavik's got nothing on us, Chicago informs world leaders", Chicago Tribune, pp. section 2, page 3

- ^ Leigh, Andrew (October 15, 1989). "Inside Moon's Washington; The Private Side of Public Relations: Improving the Image, Looking for Clout". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. p. b.01.

- ^ Sargent, Frederic O. (2004). The Civil Rights Revolution: Events and Leaders, 1955–1968. McFarland. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7864-1914-2.

- ^ "Call Deprogramming 'Spiritual Rape' Church Chiefs Denounce Whelan Acquittal". Omaha World-Herald. Omaha, Nebraska. November 8, 1988. p. 23.

- ^ Hatch, Walter (February 13, 1989). "Big names lend luster to group's causes – Church leader gains legitimacy among U.S. conservatives". The Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington: The Seattle Times Company. p. A1.

- ^ Dorr, Robert (March 10, 1991). "Franklin Stories Called LaRouche 'Moneymaker'". Omaha World-Herald. Omaha, Nebraska: Berkshire Hathaway. p. 1B.

- ^ Dorr, Robert (September 20, 1992). "Activist in Franklin Probe Is LaRouche Running Mate". Omaha World-Herald. Omaha, Nebraska: Berkshire Hathaway. p. 7B.

- ^ Barakat, Matthew (April 10, 2008). "Civil rights leader convicted of incest". USA Today. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ LaRouche Connection Master List 1991–1995

- ^ Manning, Marable (Spring 1998). "Black fundamentalism". Dissent. New York. pp. 69–77.

- ^ "Allegations Pour In Against Civil Rights Leader Accused Of Incest". Washington, DC: NBC-WRC. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- ^ Brubaker, Bill (April 11, 2008). "Civil Rights Leader Convicted of Incest". The Washington Post.

- ^ Brubaker, Bill (April 12, 2008). "Incest Verdict Is Bittersweet For Daughter Of Minister". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012.

- ^ Remington, Alexander (December 24, 2008). "The Rev. James L. Bevel dies at 72; civil rights activist and top lieutenant to King". The Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Bevel v. Commonwealth (Va.Ct.App., 14 Sept. 2010)". US Law. Justia. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Bevel v. Commonwealth (Va.S.Ct., 4 Nov. 2011)". U.S. Law. Justia. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ Hall, Heidi (April 21, 2013). "Years After Change, Activist Lives Her Conviction". USA Today. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (May 9, 2014). "Common Is James Bevel, Andre Holland Is Andrew Young In Ava DuVernay's Mlk Tale 'Selma'". Deadline. Archived from the original on May 11, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

External links

[edit]- James Bevel profile, The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute

- Statements by Rev. James L. Bevel, The Freedom Rides (see request for download at bottom of page). From the Helen L. Bevel Archives.

- SNCC Digital Gateway: James Bevel, Documentary website created by the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University, telling the story of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and grassroots organizing from the inside out

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- "A Father's Shadow" by Les Carpenter, May 25, 2008, The Washington Post

- Eyes on the Prize; Interview with James Bevel,[dead link] 1985-11-13, American Archive of Public Broadcasting

- Bevel's Last Sermon, YouTube video by Seth McClellan, filmed 10 days before Bevel's death