Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

World War I

View on Wikipedia

| World War I | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Allied Powers:

|

Central Powers:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

World War I,[b] or the First World War, (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Main areas of conflict included Europe and the Middle East, as well as parts of Africa and the Asia-Pacific. The war saw important developments in weaponry including tanks, aircraft, artillery, machine guns, and chemical weapons. One of the deadliest conflicts in history, it resulted in an estimated 30 million military casualties, and 8 million civilian deaths from war-related causes and genocide. The movement of large numbers of people was a major factor in the deadly Spanish flu pandemic.

The causes of World War I included the rise of the German Empire and decline of the Ottoman Empire, which disturbed the long-standing balance of power in Europe, the exacerbation of imperial rivalries, and an arms race between the great powers. Growing tensions in the Balkans reached a breaking point on 28 June 1914 when Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb, assassinated Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. Austria-Hungary blamed Serbia, and declared war on 28 July. After Russia mobilised in Serbia's defence, Germany declared war on Russia and France, who had an alliance. The United Kingdom entered the war after Germany invaded Belgium, and the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in November. Germany's strategy in 1914 was to quickly defeat France before transferring its forces to the east, but its advance was halted in September, and by the end of the year the Western Front consisted of a near-continuous line of trenches from the English Channel to Switzerland. The Eastern Front was more dynamic, but neither side gained a decisive advantage, despite costly offensives. Italy, Bulgaria, Romania, Greece and others entered the war from 1915 onward.

Major battles, including those at Verdun, the Somme, and Passchendaele, failed to break the stalemate on the Western Front. In April 1917, the United States joined the Allies after Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare against Atlantic shipping. Later that year, the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in the October Revolution; Soviet Russia signed an armistice with the Central Powers in December, followed by a separate peace in March 1918. That month, Germany launched a spring offensive in the west, which despite initial successes left the German Army exhausted and demoralised. The Allied Hundred Days Offensive, beginning in August 1918, caused a collapse of the German front line. Following the Vardar Offensive, Bulgaria signed an armistice in late September. By early November, the Allies had signed armistices with the Ottomans and with Austria-Hungary, leaving Germany isolated. Facing a revolution at home, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated on 9 November, and the war ended with the Armistice of 11 November 1918.

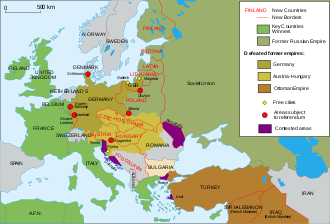

The Paris Peace Conference of 1919–1920 imposed settlements on the defeated powers. Under the Treaty of Versailles, Germany lost significant territories, was disarmed, and was required to pay large war reparations to the Allies. The dissolution of the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires led to new national boundaries and the creation of new independent states including Poland, Finland, the Baltic states, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia. The League of Nations was established to maintain world peace, but its failure to manage instability during the interwar period contributed to the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

Names

[edit]Before World War II, the events of 1914–1918 were generally known as the Great War or simply the World War.[1] In August 1914, the magazine The Independent wrote "This is the Great War. It names itself."[2] In October 1914, the Canadian magazine Maclean's similarly wrote, "Some wars name themselves. This is the Great War."[3] Contemporary Europeans also referred to it as "the war to end war" and it was also described as "the war to end all wars" due to their perception of its unparalleled scale, devastation, and loss of life.[4] The first recorded use of the term First World War was in September 1914 by German biologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel who stated, "There is no doubt that the course and character of the feared 'European War' ... will become the first world war in the full sense of the word."[5]

Background

[edit]Political and military alliances

[edit]

For much of the 19th century, the major European powers maintained a tenuous balance of power, known as the Concert of Europe.[6] After 1848, this was challenged by Britain's withdrawal into so-called splendid isolation, the decline of the Ottoman Empire, New Imperialism, and the rise of Prussia under Otto von Bismarck. Victory in the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War allowed Bismarck to consolidate a German Empire. Post-1871, the primary aim of French policy was to avenge this defeat,[7][8] but by the early 1890s, this had switched to the expansion of the French colonial empire.[9]

In 1873, Bismarck negotiated the League of the Three Emperors, which included Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Germany. After the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War, the League was dissolved due to Austrian concerns over the expansion of Russian influence in the Balkans, an area they considered to be of vital strategic interest. Germany and Austria-Hungary then formed the 1879 Dual Alliance, which became the Triple Alliance when Italy joined in 1882.[10] For Bismarck, the purpose of these agreements was to isolate France by ensuring the three empires resolved any disputes among themselves. In 1887, Bismarck set up the Reinsurance Treaty, a secret agreement between Germany and Russia to remain neutral if either were attacked by France or Austria-Hungary.[11]

For Bismarck, peace with Russia was the foundation of German foreign policy, but in 1890, he was forced to retire by Wilhelm II. The latter was persuaded not to renew the Reinsurance Treaty by his new Chancellor, Leo von Caprivi.[12] This gave France an opening to agree to the Franco-Russian Alliance in 1894, which was then followed by the 1904 Entente Cordiale with Britain. The Triple Entente was completed by the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention. While not formal alliances, by settling longstanding colonial disputes in Asia and Africa, British support for France or Russia in any future conflict became a possibility.[13] This was accentuated by British and Russian support for France against Germany during the 1911 Agadir Crisis.[14]

Arms race

[edit]

German economic and industrial strength continued to expand rapidly post-1871. Backed by Wilhelm II, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz sought to use this growth to build an Imperial German Navy that could compete with the British Royal Navy.[15] This policy was based on the work of US naval author Alfred Thayer Mahan, who argued that possession of a blue-water navy was vital for global power projection; Tirpitz had his books translated into German, while Wilhelm made them required reading for his advisors and senior military personnel.[16]

Bismarck opposed any attempt to compete with the Royal Navy, since he believed Britain would not interfere in Europe as long as its maritime supremacy remained secure. His dismissal in 1890 led to a change in policy and the start of an Anglo-German naval arms race.[17] Despite the vast sums spent by Tirpitz, the launch of HMS Dreadnought in 1906 made every existing battleship obsolete, and gave the British a technological advantage they never relinquished.[15] Ultimately, Germany invested huge resources on creating a navy large enough to antagonise Britain, but not defeat it. In 1911, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg acknowledged defeat, leading to the Rüstungswende or 'armaments turning point', when he switched expenditure from the navy to the army.[18]

This decision was driven by German concerns over the speed of Russia's recovery from defeat in the Russo-Japanese War and the subsequent 1905 Russian Revolution. Economic reforms led to a significant post-1908 expansion of railways and transportation infrastructure, particularly in its western border regions.[19] Since Germany and Austria-Hungary relied on faster mobilisation to compensate for their numerical inferiority compared to Russia, the threat posed by the closing of this gap was more important than competing with the Royal Navy. After Germany expanded its standing army by 170,000 troops in 1913, France extended compulsory military service from two to three years, sparking similar measures from the Balkan powers, Italy, the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary. Absolute figures are difficult to calculate due to differences in categorising expenditure since they often omit civilian infrastructure projects like railways which had logistical importance and military use. However, from 1908 to 1913, military spending by the six major European powers increased by over 50% in real terms.[20]

Conflicts in the Balkans

[edit]

The years before 1914 were marked by a series of crises in the Balkans, as other powers sought to benefit from the Ottoman decline. While Pan-Slavic and Orthodox Russia considered itself the protector of Serbia and other Slav states, they preferred the strategically vital Bosporus straits to be controlled by a weak Ottoman government, rather than an ambitious Slav power like Bulgaria. Russia had ambitions in northeastern Anatolia while its clients had overlapping claims in the Balkans. These competing interests divided Russian policy-makers and added to regional instability.[21]

Austrian statesmen viewed the Balkans as essential for the continued existence of their Empire and saw Serbian expansion as a direct threat. The 1908–1909 Bosnian Crisis began when Austria annexed the former Ottoman territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which it had occupied since 1878. Timed to coincide with the Bulgarian Declaration of Independence from the Ottoman Empire, this unilateral action was denounced by the European powers, but accepted as there was no consensus on how to resolve the situation. Some historians see this as a significant escalation, ending any chance of Austria cooperating with Russia in the Balkans, while also damaging diplomatic relations between Serbia and Italy.[22]

Tensions increased after the 1911–1912 Italo-Turkish War demonstrated Ottoman weakness and led to the formation of the Balkan League, an alliance of Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro, and Greece.[23] The League quickly overran most of the Ottomans' territory in the Balkans during the 1912–1913 First Balkan War, much to the surprise of outside observers.[24] The Serbian capture of ports on the Adriatic resulted in partial Austrian mobilisation, starting on 21 November 1912, including units along the Russian border in Galicia. The Russian government decided not to mobilise in response, unprepared to precipitate a war.[25]

The Great Powers sought to re-assert control through the 1913 Treaty of London, which had created an independent Albania while enlarging the territories of Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro and Greece. However, disputes between the victors sparked the 33-day Second Balkan War, when Bulgaria attacked Serbia and Greece on 16 June 1913; it was defeated, losing most of Macedonia to Serbia and Greece, and Southern Dobruja to Romania.[26] The result was that even countries which benefited from the Balkan Wars, such as Serbia and Greece, felt cheated of their "rightful gains", while for Austria it demonstrated the apparent indifference with which other powers viewed their concerns, including Germany.[27] This complex mix of resentment, nationalism and insecurity helps explain why the pre-1914 Balkans became known as the "powder keg of Europe".[28][29][30][31]

Prelude

[edit]Sarajevo assassination

[edit]

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, visited Sarajevo, the capital of the recently annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina. Cvjetko Popović, Gavrilo Princip, Nedeljko Čabrinović, Trifko Grabež, Vaso Čubrilović (Bosnian Serbs) and Muhamed Mehmedbašić (from the Bosniaks community),[34] from the movement known as Young Bosnia, took up positions along the Archduke's motorcade route, to assassinate him. Supplied with arms by extremists within the Serbian Black Hand intelligence organisation, they hoped his death would free Bosnia from Austrian rule.[35]

Čabrinović threw a grenade at the Archduke's car and injured two of his aides. The other assassins were also unsuccessful. An hour later, as Ferdinand was returning from visiting the injured officers in hospital, his car took a wrong turn into a street where Gavrilo Princip was standing. He fired two pistol shots, fatally wounding Ferdinand and his wife Sophie.[36]

According to historian Zbyněk Zeman, in Vienna "the event almost failed to make any impression whatsoever. On 28 and 29 June, the crowds listened to music and drank wine, as if nothing had happened."[37] Nevertheless, the impact of the murder of the heir to the throne was significant, and has been described by historian Christopher Clark as a "9/11 effect, a terrorist event charged with historic meaning, transforming the political chemistry in Vienna".[38]

Expansion of violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]

Austro-Hungarian authorities encouraged subsequent anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo.[39][40] Violent actions against ethnic Serbs were also organised outside Sarajevo, in other cities in Austro-Hungarian-controlled Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia. Austro-Hungarian authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina imprisoned approximately 5,500 prominent Serbs, 700 to 2,200 of whom died in prison. A further 460 Serbs were sentenced to death. A predominantly Bosniak special militia known as the Schutzkorps was established, and carried out the persecution of Serbs.[41][42][43][44]

July Crisis

[edit]

The assassination initiated the July Crisis, a month of diplomatic manoeuvring among Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, France and Britain. Believing that Serbian intelligence helped organise Franz Ferdinand's murder, Austrian officials wanted to use the opportunity to end Serbian interference in Bosnia and saw war as the best way of achieving this.[45] However, the Foreign Ministry had no solid proof of Serbian involvement.[46] On 23 July, Austria delivered an ultimatum to Serbia, listing ten demands made intentionally unacceptable to provide an excuse for starting hostilities.[47]

Serbia ordered general mobilisation on 25 July, but accepted all the terms, except for those empowering Austrian representatives to suppress "subversive elements" inside Serbia, and take part in the investigation and trial of Serbians linked to the assassination.[48][49] Claiming this amounted to rejection, Austria broke off diplomatic relations and ordered partial mobilisation the next day; on 28 July, they declared war on Serbia and began shelling Belgrade. Russia ordered general mobilisation in support of Serbia on 30 July.[50]

Anxious to ensure backing from the SPD political opposition by presenting Russia as the aggressor, German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg delayed the commencement of war preparations until 31 July.[51] That afternoon, the Russian government were handed a note requiring them to "cease all war measures against Germany and Austria-Hungary" within 12 hours.[52] A further German demand for neutrality was refused by the French who ordered general mobilisation but delayed declaring war.[53] The German General Staff had long assumed they faced a war on two fronts; the Schlieffen Plan envisaged using 80% of the army to defeat France, then switching to Russia. Since this required them to move quickly, mobilisation orders were issued that afternoon.[54] Once the German ultimatum to Russia expired on the morning of 1 August, the two countries were at war.

At a meeting on 29 July, the British cabinet had narrowly decided its obligations to Belgium under the 1839 Treaty of London did not require it to oppose a German invasion with military force; however, Prime Minister Asquith and his senior Cabinet ministers were already committed to supporting France, the Royal Navy had been mobilised, and public opinion was strongly in favour of intervention.[55] On 31 July, Britain sent notes to Germany and France, asking them to respect Belgian neutrality; France pledged to do so, but Germany did not reply.[56] Aware of German plans to attack through Belgium, French Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre asked his government for permission to cross the border and pre-empt such a move. To avoid violating Belgian neutrality, he was told any advance could come only after a German invasion.[57] Instead, the French cabinet ordered its Army to withdraw 10 km behind the German frontier, to avoid provoking war. On 2 August, Germany occupied Luxembourg and exchanged fire with French units when German patrols entered French territory; on 3 August, they declared war on France and demanded free passage across Belgium, which was refused. Early on the morning of 4 August, the Germans invaded, and Albert I of Belgium called for assistance under the Treaty of London.[58][59] Britain sent Germany an ultimatum demanding they withdraw from Belgium; when this expired at midnight, without a response, the two empires were at war.[60]

Progress of the war

[edit]Opening hostilities

[edit]Confusion among the Central Powers

[edit]Germany promised to support Austria-Hungary's invasion of Serbia, but interpretations of what this meant differed. Previously tested deployment plans had been replaced early in 1914, but those had never been tested in exercises. Austro-Hungarian leaders believed Germany would cover its northern flank against Russia.[61]

Serbian campaign

[edit]

Beginning on 12 August, the Austrians and Serbs clashed at the battles of the Cer and Kolubara; over the next two weeks, Austrian attacks were repulsed with heavy losses. As a result, Austria had to keep sizeable forces on the Serbian front, weakening their efforts against Russia.[62] Serbia's victory against Austria-Hungary in the 1914 invasion has been called one of the major upset victories of the twentieth century.[63] In 1915, the campaign saw the first use of anti-aircraft warfare after an Austrian plane was shot down with ground-to-air fire, as well as the first medical evacuation by the Serbian army.[64][65]

German offensive in Belgium and France

[edit]

Upon mobilisation, in accordance with the Schlieffen Plan, 80% of the German Army was located on the Western Front, with the remainder acting as a screening force in the East. Rather than a direct attack across their shared frontier, the German right wing would sweep through the Netherlands and Belgium, then swing south, encircling Paris and trapping the French army against the Swiss border. The plan's creator, Alfred von Schlieffen, head of the German General Staff from 1891 to 1906, estimated that this would take six weeks, after which the German army would transfer to the East and defeat the Russians.[66]

The plan was substantially modified by his successor, Helmuth von Moltke the Younger. Under Schlieffen, 85% of German forces in the west were assigned to the right wing, with the remainder holding along the frontier. By keeping his left-wing deliberately weak, he hoped to lure the French into an offensive into the "lost provinces" of Alsace-Lorraine, which was the strategy envisaged by their Plan XVII.[66] However, Moltke grew concerned that the French might push too hard on his left flank and as the German Army increased in size from 1908 to 1914, he changed the allocation of forces between the two wings to 70:30.[67] He also considered Dutch neutrality essential for German trade and cancelled the incursion into the Netherlands, which meant any delays in Belgium threatened the viability of the plan.[68] Historian Richard Holmes argues that these changes meant the right wing was not strong enough to achieve decisive success.[69]

The initial German advance in the West was very successful. By the end of August, the Allied left, which included the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), was in full retreat, and the French offensive in Alsace-Lorraine was a disastrous failure, with casualties exceeding 260,000.[70] German planning provided broad strategic instructions while allowing army commanders considerable freedom in carrying them out at the front, but Alexander von Kluck used this freedom to disobey orders, opening a gap between the German armies as they closed on Paris.[71] The French army, reinforced by the British expeditionary corps, seized this opportunity to counter-attack and pushed the German army 40 to 80 km back. Both armies were then so exhausted that no decisive move could be implemented, so they settled in trenches, with the vain hope of breaking through as soon as they could build local superiority.

In 1911, the Russian Stavka agreed with the French to attack Germany within fifteen days of mobilisation, ten days before the Germans had anticipated, although it meant the two Russian armies that entered East Prussia on 17 August did so without many of their support elements.[72]

By the end of 1914, German troops held strong defensive positions inside France, controlled the bulk of France's domestic coalfields, and inflicted 230,000 more casualties than it lost itself. However, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Germany the chance of a decisive outcome, while it had failed to achieve the primary objective of avoiding a long, two-front war.[73] As was apparent to several German leaders, this amounted to a strategic defeat; shortly after the First Battle of the Marne, Crown Prince Wilhelm told an American reporter "We have lost the war. It will go on for a long time but lost it is already."[74]

Asia and the Pacific

[edit]

On 30 August 1914, New Zealand occupied German Samoa (now Samoa). On 11 September, the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force landed on the island of New Britain, then part of German New Guinea. On 28 October, the German cruiser SMS Emden sank the Russian cruiser Zhemchug in the Battle of Penang. Japan declared war on Germany before seizing territories in the Pacific, which later became the South Seas Mandate, as well as German Treaty ports on the Chinese Shandong peninsula at Tsingtao. After Vienna refused to withdraw its cruiser SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth from Tsingtao, Japan declared war on Austria-Hungary, and the ship was scuttled in November 1914.[75] Within a few months, Allied forces had seized all German territories in the Pacific, leaving only isolated commerce raiders and a few holdouts in New Guinea.[76][77]

African campaigns

[edit]

Some of the first clashes of the war involved British, French, and German colonial forces in Africa. On 6–7 August, French and British troops invaded the German protectorates of Togoland and Kamerun. On 10 August, German forces in South-West Africa attacked South Africa; sporadic and fierce fighting continued for the rest of the war. The German colonial forces in German East Africa, led by Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, fought a guerrilla warfare campaign and only surrendered two weeks after the armistice took effect in Europe.[78]

Indian support for the Allies

[edit]

Before the war, Germany had attempted to use Indian nationalism and pan-Islamism to its advantage, a policy continued post-1914 by instigating uprisings in India, while the Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition urged Afghanistan to join the war on the side of Central Powers. However, contrary to British fears of a revolt in India, the outbreak of the war saw a reduction in nationalist activity.[79][80] Leaders from the Indian National Congress and other groups believed support for the British war effort would hasten Indian Home Rule, a promise allegedly made explicit in 1917 by Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State for India.[81]

In 1914, the British Indian Army was larger than the British Army itself, and between 1914 and 1918 an estimated 1.3 million Indian soldiers and labourers served in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. In all, 140,000 soldiers served on the Western Front and nearly 700,000 in the Middle East, with 47,746 killed and 65,126 wounded.[82] The suffering engendered by the war, as well as the failure of the British government to grant self-government to India afterward, bred disillusionment, resulting in the campaign for full independence led by Mahatma Gandhi.[83]

Western Front

[edit]Trench warfare begins

[edit]

Pre-war military tactics that had emphasised open warfare and individual riflemen proved obsolete when confronted with conditions prevailing in 1914. Technological advances allowed the creation of strong defensive systems largely impervious to massed infantry advances, such as barbed wire, machine guns and above all far more powerful artillery, which dominated the battlefield and made crossing open ground extremely difficult.[84] Both sides struggled to develop tactics for breaching entrenched positions without heavy casualties. In time, technology enabled the production of new offensive weapons, such as gas warfare and the tank.[85]

After the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914, Allied and German forces unsuccessfully tried to outflank each other, a series of manoeuvres later known as the "Race to the Sea". By the end of 1914, the opposing forces confronted each other along an uninterrupted line of entrenched positions from the Channel to the Swiss border.[86] Since the Germans were normally able to choose where to stand, they generally held the high ground, while their trenches tended to be better built; those constructed by the French and English were initially considered "temporary", only needed until an offensive would destroy the German defences.[87] Both sides tried to break the stalemate using scientific and technological advances. On 22 April 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres, the Germans (violating the Hague Convention) used chlorine gas for the first time on the Western Front. Several types of gas soon became widely used by both sides and though it never proved a decisive, battle-winning weapon, it became one of the most feared and best-remembered horrors of the war.[88][89]

Continuation of trench warfare

[edit]

In February 1916, the Germans attacked French defensive positions at the Battle of Verdun, lasting until December 1916. Casualties were greater for the French, but the Germans bled heavily as well, with anywhere from 700,000[90] to 975,000[91] casualties between the two combatants. Verdun became a symbol of French determination and self-sacrifice.[92]

The Battle of the Somme was an Anglo-French offensive from July to November 1916. The opening day, on 1 July 1916, was the bloodiest single day in the history of the British Army, which suffered 57,500 casualties, including 19,200 dead. As a whole, the Somme offensive led to an estimated 420,000 British casualties, along with 200,000 French and 500,000 Germans.[93] The diseases that emerged in the trenches were a major killer on both sides. The living conditions led to disease and infection, such as trench foot, lice, typhus, trench fever, and the 'Spanish flu'.[94]

Naval war

[edit]

At the start of the war, German cruisers were scattered across the globe, some of which were subsequently used to attack Allied merchant shipping. These were systematically hunted down by the Royal Navy, though not before causing considerable damage. One of the most successful was the SMS Emden, part of the German East Asia Squadron stationed at Qingdao, which seized or sank 15 merchantmen, a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer. Most of the squadron was returning to Germany when it sank two British armoured cruisers at the Battle of Coronel in November 1914, before being virtually destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in December. The SMS Dresden escaped with a few auxiliaries, but after the Battle of Más a Tierra, these too were either destroyed or interned.[95]

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, Britain began a naval blockade of Germany. This proved effective in cutting off vital supplies, though it violated accepted international law.[96] Britain also mined international waters which closed off entire sections of the ocean, even to neutral ships.[97] Since there was limited response to this tactic, Germany expected a similar response to its unrestricted submarine warfare.[98]

The Battle of Jutland[d] in May/June 1916 was the only full-scale clash of battleships during the war, and one of the largest in history. The clash was indecisive, though the Germans inflicted more damage than they received; thereafter the bulk of the German High Seas Fleet was confined to port.[99]

German U-boats attempted to cut the supply lines between North America and Britain.[100] The nature of submarine warfare meant that attacks often came without warning, giving the crews of the merchant ships little hope of survival.[100][101] The United States launched a protest, and Germany changed its rules of engagement. After the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania in 1915, Germany promised not to target passenger liners, while Britain armed its merchant ships, placing them beyond the protection of the "cruiser rules", which demanded warning and movement of crews to "a place of safety" (a standard that lifeboats did not meet).[102] Finally, in early 1917, Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, realising the Americans would eventually enter the war.[100][103] Germany sought to strangle Allied sea lanes before the United States could transport a large army overseas, but, after initial successes, eventually failed to do so.[100]

The U-boat threat lessened in 1917, when merchant ships began travelling in convoys, escorted by destroyers. This tactic made it difficult for U-boats to find targets, which significantly lessened losses; after the hydrophone and depth charges were introduced, destroyers could potentially successfully attack a submerged submarine. Convoys slowed the flow of supplies since ships had to wait as convoys were assembled; the solution was an extensive program of building new freighters. Troopships were too fast for the submarines and did not travel the North Atlantic in convoys.[104] The U-boats sunk more than 5,000 Allied ships, at the cost of 199 submarines.[105]

World War I also saw the first use of aircraft carriers in combat, with HMS Furious launching Sopwith Camels in a successful raid against the Zeppelin hangars at Tondern in July 1918, as well as blimps for antisubmarine patrol.[106]

Southern theatres

[edit]War in the Balkans

[edit]

Faced with Russia in the east, Austria-Hungary could spare only one-third of its army to attack Serbia. After suffering heavy losses, the Austrians briefly occupied the Serbian capital, Belgrade. A Serbian counter-attack in the Battle of Kolubara succeeded in driving them from the country by the end of 1914. For the first 10 months of 1915, Austria-Hungary used most of its military reserves to fight Italy. German and Austro-Hungarian diplomats scored a coup by persuading Bulgaria to join the attack on Serbia.[107] The Austro-Hungarian provinces of Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia provided troops for Austria-Hungary. Montenegro allied itself with Serbia.[108]

Bulgaria declared war on Serbia on 14 October 1915, and joined in the attack by the Austro-Hungarian army under Mackensen's army of 250,000 that was already underway. Serbia was conquered in a little more than a month, as the Central Powers, now including Bulgaria, sent in 600,000 troops in total. The Serbian army, fighting on two fronts and facing certain defeat, retreated into northern Albania. The Serbs suffered defeat in the Battle of Kosovo. Montenegro covered the Serbian retreat toward the Adriatic coast in the Battle of Mojkovac on 6–7 January 1916, but ultimately the Austrians also conquered Montenegro. The surviving Serbian soldiers were evacuated to Greece.[109] After the conquest, Serbia was divided between Austro-Hungary and Bulgaria.[110]

In late 1915, a Franco-British force landed at Salonica in Greece to offer assistance and to pressure its government to declare war against the Central Powers. However, the pro-German King Constantine I dismissed the pro-Allied government of Eleftherios Venizelos before the Allied expeditionary force arrived.[111]

The Macedonian front was at first mostly static. French and Serbian forces retook limited areas of Macedonia by recapturing Bitola on 19 November 1916, following the costly Monastir offensive, which brought stabilisation of the front.[112]

Serbian and French troops finally made a breakthrough in September 1918 in the Vardar offensive, after most German and Austro-Hungarian troops had been withdrawn. The Bulgarians were defeated at the Battle of Dobro Pole, and by 25 September British and French troops had crossed the border into Bulgaria proper as the Bulgarian army collapsed. Bulgaria capitulated four days later, on 29 September 1918.[114] The German high command responded by despatching troops to hold the line, but these forces were too weak to re-establish a front.[115]

The Allied breakthrough on the Macedonian front cut communications between the Ottoman Empire and the other Central Powers, and made Vienna vulnerable to attack. Hindenburg and Ludendorff concluded that the strategic and operational balance had now shifted decidedly against the Central Powers and, a day after the Bulgarian collapse, insisted on an immediate peace settlement.[116]

Ottoman Empire

[edit]

The Ottomans threatened Russia's Caucasian territories and Britain's communications with India via the Suez Canal. The Ottoman Empire took advantage of the European powers' preoccupation with the war and conducted large-scale ethnic cleansing of the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian Christian populations—the Armenian genocide, Greek genocide, and Assyrian genocide respectively.[117][118] [119]

The British and French opened overseas fronts with the Gallipoli (1915) and Mesopotamian campaigns (1914). In Gallipoli, the Ottoman Empire successfully repelled the British, French, and Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs). In Mesopotamia, by contrast, after the defeat of the British defenders in the siege of Kut by the Ottomans (1915–1916), British Imperial forces reorganised and captured Baghdad in March 1917. The British were aided in Mesopotamia by local Arab and Assyrian fighters, while the Ottomans employed local Kurdish and Turcoman tribes.[120]

The Suez Canal was defended from Ottoman attacks in 1915 and 1916; in August 1916, a German and Ottoman force was defeated at the Battle of Romani by the ANZAC Mounted Division and the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division. Following this victory, an Egyptian Expeditionary Force advanced across the Sinai Peninsula, pushing Ottoman forces back in the Battle of Magdhaba in December and the Battle of Rafa on the border between the Egyptian Sinai and Ottoman Palestine in January 1917.[121]

Russian armies generally had success in the Caucasus campaign. Enver Pasha, supreme commander of the Ottoman armed forces, dreamed of re-conquering central Asia and areas that had been previously lost to Russia. He was, however, a poor commander.[122] He launched an offensive against the Russians in the Caucasus in December 1914 with 100,000 troops, insisting on a frontal attack against mountainous Russian positions in winter. He lost 86% of his force at the Battle of Sarikamish.[123] General Nikolai Yudenich, the Russian commander from 1915 to 1916, drove the Turks out of most of the southern Caucasus.[123]

The Ottoman Empire, with German support, invaded Persia (modern Iran) in December 1914 to cut off British and Russian access to petroleum reservoirs around Baku.[124] Persia, ostensibly neutral, had long been under British and Russian influence. The Ottomans and Germans were aided by Kurdish and Azeri forces, together with a large number of major Iranian tribes, while the Russians and British had the support of Armenian and Assyrian forces. The Persian campaign lasted until 1918 and ended in failure for the Ottomans and their allies. However, the Russian withdrawal from the war in 1917 led Armenian and Assyrian forces to be cut off from supply lines, outnumbered, outgunned and isolated, forcing them to fight and flee towards British lines in northern Mesopotamia.[125]

The Arab Revolt, instigated by the British Foreign Office, started in June 1916 with the Battle of Mecca, led by Sharif Hussein. The Sharif declared the independence of the Kingdom of Hejaz and, with British assistance, conquered much of Ottoman-held Arabia, resulting finally in the Ottoman surrender of Damascus. Fakhri Pasha, the Ottoman commander of Medina, resisted for more than 2+1⁄2 years during the siege of Medina before surrendering in January 1919.[126]

The Senussi tribe, along the border of Italian Libya and British Egypt, incited and armed by the Turks, waged a small-scale guerrilla war against Allied troops. The British were forced to dispatch 12,000 troops to oppose them in the Senussi campaign. Their rebellion was finally crushed in mid-1916.[127]

Total Allied casualties on the Ottoman fronts amounted to 650,000 men. Total Ottoman casualties were 725,000, with 325,000 dead and 400,000 wounded.[128]

Italian Front

[edit]

Though Italy joined the Triple Alliance in 1882, a treaty with its traditional Austrian enemy was so controversial that subsequent governments denied its existence and the terms were only made public in 1915.[129] This arose from nationalist designs on Austro-Hungarian territory in Trentino, the Austrian Littoral, Rijeka and Dalmatia, considered vital to secure the borders established in 1866.[130] In 1902, Rome secretly had agreed with France to remain neutral if the latter was attacked by Germany, effectively nullifying its role in the Triple Alliance.[131]

When the war began in 1914, Italy argued the Triple Alliance was defensive and it was not obliged to support an Austrian attack on Serbia. Opposition to joining the Central Powers increased when Turkey became a member in September, since in 1911 Italy had occupied Ottoman possessions in Libya and the Dodecanese islands.[132] To secure Italian neutrality, the Central Powers offered them Tunisia, while in return for an immediate entry into the war, the Allies agreed to their demands for Austrian territory and sovereignty over the Dodecanese.[133] Although they remained secret, these provisions were incorporated into the April 1915 Treaty of London, and Italy joined the Allies. On 23 May, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary,[134] and on Germany fifteen months later.

The pre-1914 Italian army was short of officers, trained men, adequate transport and modern weapons; by April 1915, some of these deficiencies had been remedied but it was still unprepared for the major offensive required by the Treaty of London.[135] The advantage of superior numbers was offset by the difficult terrain; much of the fighting took place high in the Alps and Dolomites, where trench lines had to be cut through rock and ice and keeping troops supplied was a major challenge. These issues were exacerbated by unimaginative strategies and tactics.[136] Between 1915 and 1917, the Italian commander, Luigi Cadorna, undertook a series of frontal assaults along the Isonzo, which made little progress and cost many lives; by the end of the war, Italian combat deaths totalled around 548,000.[137]

In the spring of 1916, the Austro-Hungarians counterattacked in Asiago in the Strafexpedition, but made little progress and were pushed by the Italians back to Tyrol.[138] Although Italy occupied southern Albania in May 1916, their main focus was the Isonzo front which, after the capture of Gorizia in August 1916, remained static until October 1917. After a combined Austro-German force won a major victory at Caporetto, Cadorna was replaced by Armando Diaz who retreated more than 100 kilometres (62 mi) before holding positions along the Piave River.[139] A second Austrian offensive was repulsed in June 1918. On 24 October, Diaz launched the Battle of Vittorio Veneto and initially met stubborn resistance,[140] but with Austria-Hungary collapsing, Hungarian divisions in Italy demanded they be sent home.[141] When this was granted, many others followed and the Imperial army disintegrated, the Italians taking over 300,000 prisoners.[142] On 3 November, the Armistice of Villa Giusti ended hostilities between Austria-Hungary and Italy which occupied Trieste and areas along the Adriatic Sea awarded to it in 1915.[143]

Eastern Front

[edit]Initial actions

[edit]

As previously agreed with French president Raymond Poincaré, Russian plans at the start of the war were to simultaneously advance into Austrian Galicia and East Prussia as soon as possible. Although their attack on Galicia was largely successful, and the invasions achieved their aim of forcing Germany to divert troops from the Western Front, the speed of mobilisation meant they did so without much of their heavy equipment and support functions. These weaknesses contributed to Russian defeats at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes in August and September 1914, forcing them to withdraw from East Prussia with heavy losses.[144][145] By spring 1915, they had also retreated from Galicia, and the May 1915 Gorlice–Tarnów offensive allowed the Central Powers to invade Russian-occupied Poland.[146]

Despite the successful June 1916 Brusilov offensive against the Austrians in eastern Galicia,[147] shortages of supplies, heavy losses and command failures prevented the Russians from fully exploiting their victory. However, it was one of the most significant offensives of the war, diverting German resources from Verdun, relieving Austro-Hungarian pressure on the Italians, and convincing Romania to enter the war on the side of the Allies on 27 August. It also fatally weakened both the Austrian and Russian armies, whose offensive capabilities were badly affected by their losses and increased disillusion with the war that ultimately led to the Russian revolutions.[148]

Meanwhile, unrest grew in Russia as Tsar Nicholas II remained at the front, with the home front controlled by Empress Alexandra. Her increasingly incompetent rule and food shortages in urban areas led to widespread protests and the murder of her favourite, Grigori Rasputin, at the end of 1916.[149]

Romanian participation

[edit]Despite secretly agreeing to support the Triple Alliance in 1883, Romania increasingly found itself at odds with the Central Powers over their support for Bulgaria in the Balkan Wars and the status of ethnic Romanian communities in Hungarian-controlled Transylvania,[150] which comprised an estimated 2.8 million of the region's 5.0 million population.[151] With the ruling elite split into pro-German and pro-Entente factions,[152] Romania remained neutral for two years while allowing Germany and Austria to transport military supplies and advisors across Romanian territory.[153]

In September 1914, Russia acknowledged Romanian rights to Austro-Hungarian territories including Transylvania and Banat, whose acquisition had widespread popular support,[151] and Russian success against Austria led Romania to join the Entente in the August 1916 Treaty of Bucharest.[153] Under the strategic plan known as Hypothesis Z, the Romanian army planned an offensive into Transylvania, while defending Southern Dobruja and Giurgiu against a possible Bulgarian counterattack.[154] On 27 August 1916, they attacked Transylvania and occupied substantial parts of the province before being driven back by the recently formed German 9th Army, led by former Chief of Staff Erich von Falkenhayn.[155] A combined German-Bulgarian-Turkish offensive captured Dobruja and Giurgiu, although the bulk of the Romanian army managed to escape encirclement and retreated to Bucharest, which surrendered to the Central Powers on 6 December 1916.[156]

In the summer of 1917, a Central Powers offensive began in Romania under the command of August von Mackensen to knock Romania out of the war, resulting in the battles of Oituz, Mărăști and Mărășești, where up to 1,000,000 Central Powers troops were present. The battles lasted from 22 July to 3 September and eventually the Romanian army was victorious advancing 500 km2. August von Mackensen could not plan for another offensive as he had to transfer troops to the Italian Front.[157] Following the Russian revolution, Romania found itself alone on the Eastern Front and signed the Treaty of Bucharest with the Central Powers, which recognised Romanian sovereignty over Bessarabia in return for ceding control of passes in the Carpathian Mountains to Austria-Hungary and leasing its oil wells to Germany. Although approved by Parliament, King Ferdinand I refused to sign it, hoping for an Allied victory in the west.[158] Romania re-entered the war on 10 November 1918, on the side of the Allies and the Treaty of Bucharest was formally annulled by the Armistice of 11 November 1918.[159][e]

Central Powers peace overtures

[edit]On 12 December 1916, after ten brutal months of the Battle of Verdun and a successful offensive against Romania, Germany attempted to negotiate a peace with the Allies.[161] However, this attempt was rejected out of hand as a "duplicitous war ruse".[161]

US president Woodrow Wilson attempted to intervene as a peacemaker, asking for both sides to state their demands. Lloyd George's War Cabinet considered the German offer to be a ploy to create divisions among the Allies. After initial outrage and much deliberation, they took Wilson's note as a separate effort, signalling that the US was on the verge of entering the war against Germany following the "submarine outrages". While the Allies debated a response to Wilson's offer, the Germans chose to rebuff it in favour of "a direct exchange of views". Learning of the German response, the Allied governments were free to make clear demands in their response of 14 January. They sought restoration of damages, the evacuation of occupied territories, reparations for France, Russia and Romania, and a recognition of the principle of nationalities.[162] The Allies sought guarantees that would prevent or limit future wars.[163] The negotiations failed and the Entente powers rejected the German offer on the grounds of honour, and noted Germany had not put forward any specific proposals.[161]

Final years of the war

[edit]Russian Revolution and withdrawal

[edit]

By the end of 1916, Russian casualties totalled nearly five million killed, wounded or captured, with major urban areas affected by food shortages and high prices. In March 1917, Tsar Nicholas ordered the military to forcibly suppress strikes in Petrograd but the troops refused to fire on the crowds.[164] Revolutionaries set up the Petrograd Soviet and fearing a left-wing takeover, the State Duma forced Nicholas to abdicate and established the Russian Provisional Government, which confirmed Russia's willingness to continue the war. However, the Petrograd Soviet refused to disband, creating competing power centres and causing confusion and chaos, with frontline soldiers becoming increasingly demoralised.[165]

Following the tsar's abdication, Vladimir Lenin—with the help of the German government—was ushered from Switzerland into Russia on 16 April 1917. Discontent and the weaknesses of the Provisional Government led to a rise in the popularity of the Bolshevik Party, led by Lenin, which demanded an immediate end to the war. The Revolution of November was followed in December by an armistice and negotiations with Germany. At first, the Bolsheviks refused the German terms, but when German troops began marching across Ukraine unopposed, they acceded to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918. The treaty ceded vast territories, including Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and parts of Poland and Ukraine to the Central Powers.[166]

With the Russian Empire out of the war, Romania found itself alone on the Eastern Front and signed the Treaty of Bucharest with the Central Powers in May 1918. Under the terms of the treaty, Romania ceded territory to Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria and leased its oil reserves to Germany. However, the terms also included the Central Powers' recognition of the union of Bessarabia with Romania.[167][158]

United States enters the war

[edit]

The United States was a major supplier of war material to the Allies but remained neutral in 1914, in large part due to domestic opposition.[168] The most significant factor in creating the support Wilson needed was the German submarine offensive, which not only cost American lives but paralysed trade as ships were reluctant to put to sea.[169]

On 6 April 1917, Congress declared war on Germany as an "Associated Power" of the Allies.[170] The US Navy sent a battleship group to Scapa Flow to join the Grand Fleet, and provided convoy escorts. In April 1917, the US Army had fewer than 300,000 men, including National Guard units, compared to British and French armies of 4.1 and 8.3 million respectively. The Selective Service Act of 1917 drafted 2.8 million men, though training and equipping such numbers was a huge logistical challenge. By June 1918, over 667,000 members of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) were transported to France, a figure which reached 2 million by the end of November.[171]

Despite his conviction that Germany must be defeated, Wilson went to war to ensure the US played a leading role in shaping the peace, which meant preserving the AEF as a separate military force, rather than being absorbed into British or French units as his Allies wanted.[172] He was strongly supported by AEF commander General John J. Pershing, a proponent of pre-1914 "open warfare" who considered the French and British emphasis on artillery misguided and incompatible with American "offensive spirit".[173] Much to the frustration of his Allies, who had suffered heavy losses in 1917, he insisted on retaining control of American troops, and refused to commit them to the front line until able to operate as independent units. As a result, the first significant US involvement was the Meuse–Argonne offensive in late September 1918.[174]

Nivelle Offensive (April–May 1917)

[edit]

In December 1916, Robert Nivelle replaced Pétain as commander of French armies on the Western Front and began planning a spring attack in Champagne, part of a joint Franco-British operation.[175] Poor security meant German intelligence was well informed on tactics and timetables, but despite this, when the attack began on 16 April the French made substantial gains, before being brought to a halt by the newly built and extremely strong defences of the Hindenburg Line. Nivelle persisted with frontal assaults and, by 25 April, the French had suffered nearly 135,000 casualties, including 30,000 dead, most incurred in the first two days.[176]

Concurrent British attacks at Arras were more successful, though ultimately of little strategic value.[177] Operating as a separate unit for the first time, the Canadian Corps' capture of Vimy Ridge is viewed by many Canadians as a defining moment in creating a sense of national identity.[178][179] Though Nivelle continued the offensive, on 3 May the 21st Division, which had been involved in some of the heaviest fighting at Verdun, refused orders to go into battle, initiating the French Army mutinies; within days, "collective indiscipline" had spread to 54 divisions, while over 20,000 deserted.[180]

Sinai and Palestine campaign (1917–1918)

[edit]

In March and April 1917, at the First and Second Battles of Gaza, German and Ottoman forces stopped the advance of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, which had begun in August 1916 at the Battle of Romani.[181][182] At the end of October 1917, the Sinai and Palestine campaign resumed, when General Edmund Allenby's XXth Corps, XXI Corps and Desert Mounted Corps won the Battle of Beersheba.[183] Two Ottoman armies were defeated a few weeks later at the Battle of Mughar Ridge and, early in December, Jerusalem had been captured following another Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Jerusalem.[184][185][186]

About this time, Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein was relieved of his duties as the Eighth Army's commander, replaced by Djevad Pasha, and a few months later the commander of the Ottoman Army in Palestine, Erich von Falkenhayn, was replaced by Otto Liman von Sanders.[187][188]

In early 1918, the front line was extended and the Jordan Valley was occupied, following the First Transjordan and the Second Transjordan attacks by British Empire forces in March and April 1918.[189]

German offensive and Allied counter-offensive (March–November 1918)

[edit]

In December 1917, the Central Powers signed an armistice with Russia, thus freeing large numbers of German troops for use in the West. With German reinforcements and new American troops pouring in, the outcome was to be decided on the Western Front. The Central Powers knew that they could not win a protracted war, but they held high hopes for success in a final quick offensive.[191] Ludendorff drew up plans (Operation Michael) for the 1918 offensive on the Western Front. The operation commenced on 21 March 1918, with an attack on British forces near Saint-Quentin. German forces achieved an unprecedented advance of 60 kilometres (37 mi).[192] The initial offensive was a success; after heavy fighting, however, the offensive was halted. Lacking tanks or motorised artillery, the Germans were unable to consolidate their gains. The problems of re-supply were also exacerbated by increasing distances that now stretched over terrain that was shell-torn and often impassable to traffic.[193] Germany launched Operation Georgette against the northern English Channel ports. The Allies halted the drive after limited territorial gains by Germany. The German Army to the south then conducted Operations Blücher and Yorck, pushing broadly towards Paris. Germany launched Operation Marne (Second Battle of the Marne) on 15 July, in an attempt to encircle Reims. The resulting counter-attack, which started the Hundred Days Offensive on 8 August,[194] led to a marked collapse in German morale.[195][196][197]

Allied advance to the Hindenburg Line

[edit]

By September, the Germans had fallen back to the Hindenburg Line. The Allies had advanced to the Hindenburg Line in the north and centre. German forces launched numerous counterattacks, but positions and outposts of the Line continued falling, with the BEF alone taking 30,441 prisoners in the last week of September. On 24 September, the Supreme Army Command informed the leaders in Berlin that armistice talks were inevitable.[198]

The final assault on the Hindenburg Line began with the Meuse-Argonne offensive, launched by American and French troops on 26 September. Two days later the Belgians, French and British attacked around Ypres, and the day after the British at St Quentin in the centre of the line. The following week, cooperating American and French units broke through in Champagne at the Battle of Blanc Mont Ridge ( 3–27 October), forcing the Germans off the commanding heights, and closing towards the Belgian frontier.[199] On 8 October, the Hindenburg Line was pierced by British and Dominion troops of the First and Third British Armies at the Second Battle of Cambrai.[200]

Breakthrough of Macedonian front (September 1918)

[edit]

Allied forces started the Vardar offensive on 15 September at two key points: Dobro Pole and near Dojran Lake. In the Battle of Dobro Pole, the Serbian and French armies had success after a three-day-long battle with relatively small casualties, and subsequently made a breakthrough in the front, something which was rarely seen in World War I. After the front was broken, Allied forces started to liberate Serbia and reached Skopje at 29 September, after which Bulgaria signed an armistice with the Allies on 30 September.[201][202]

Armistices and capitulations

[edit]

The collapse of the Central Powers came swiftly. Bulgaria was the first to sign an armistice, the Armistice of Salonica on 29 September 1918.[203] Wilhelm II, in a telegram to Tsar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria described the situation thus: "Disgraceful! 62,000 Serbs decided the war!".[204][205] On the same day, the German Supreme Army Command informed Wilhelm II and the Imperial Chancellor Count Georg von Hertling, that the military situation facing Germany was hopeless.[206]

On 24 October, the Italians began a push that rapidly recovered territory lost after the Battle of Caporetto. This culminated in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, marking the end of the Austro-Hungarian Army as an effective fighting force. The offensive also triggered the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During the last week of October, declarations of independence were made in Budapest, Prague, and Zagreb. On 29 October, the imperial authorities asked Italy for an armistice, but the Italians continued advancing, reaching Trento, Udine, and Trieste. On 3 November, Austria-Hungary sent a flag of truce and accepted the Armistice of Villa Giusti, arranged with the Allied Authorities in Paris. Austria and Hungary signed separate armistices following the overthrow of the Habsburg monarchy. In the following days, the Italian Army occupied Innsbruck and all Tyrol, with over 20,000 soldiers.[207] On 30 October, the Ottoman Empire capitulated, and signed the Armistice of Mudros.[203]

German government surrenders

[edit]

With the military faltering and with widespread loss of confidence in the kaiser, Germany moved towards surrender. Prince Maximilian of Baden took charge on 3 October as Chancellor of Germany. Negotiations with President Wilson began immediately, in the hope that he would offer better terms than the British and French. Wilson demanded a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary control over the German military.[209]

The German Revolution of 1918–1919 began at the end of October 1918. Units of the German Navy refused to set sail for a large-scale operation in a war they believed to be as good as lost. The sailors' revolt, which then ensued in the naval ports of Wilhelmshaven and Kiel, spread across the whole country within days and led to the proclamation of a republic on 9 November 1918, shortly thereafter to the abdication of Wilhelm II, and German surrender.[210][211][212][213][214]

Aftermath

[edit]In the aftermath of the war, the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian empires disappeared.[f] Numerous nations regained their former independence, and new ones were created. Four dynasties fell as a result of the war: the Romanovs, the Hohenzollerns, the Habsburgs, and the Ottomans. Belgium and Serbia were badly damaged, as was France, with 1.4 million soldiers dead,[215] not counting other casualties. Germany and Russia were similarly affected.[216]

Formal end of the war

[edit]

A formal state of war between the two sides persisted for another seven months, until the signing of the Treaty of Versailles with Germany on 28 June 1919. The US Senate did not ratify the treaty despite public support for it,[217][218]and did not formally end its involvement in the war until the Knox–Porter Resolution was signed on 2 July 1921 by President Warren G. Harding.[219] For the British Empire, the state of war ceased under the provisions of the Termination of the Present War (Definition) Act 1918 concerning:

Some war memorials date the end of the war as being when the Versailles Treaty was signed in 1919, which was when many of the troops serving abroad finally returned home; by contrast, most commemorations of the war's end concentrate on the armistice of 11 November 1918.[225]

Peace treaties and national boundaries

[edit]

The Paris Peace Conference imposed a series of peace treaties on the Central Powers officially ending the war. The 1919 Treaty of Versailles dealt with Germany and, building on Wilson's 14th point, established the League of Nations on 28 June 1919.[226][227]

The Central Powers had to acknowledge responsibility for "all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by" their aggression. In the Treaty of Versailles, this statement was Article 231. This article became known as the "War Guilt Clause", as the majority of Germans felt humiliated and resentful.[228] The Germans felt they had been unjustly dealt with by what they called the "diktat of Versailles". German historian Hagen Schulze said the Treaty placed Germany "under legal sanctions, deprived of military power, economically ruined, and politically humiliated."[229] Belgian historian Laurence Van Ypersele emphasises the central role played by memory of the war and the Versailles Treaty in German politics in the 1920s and 1930s:

Active denial of war guilt in Germany and German resentment at both reparations and continued Allied occupation of the Rhineland made widespread revision of the meaning and memory of the war problematic. The legend of the "stab in the back" and the wish to revise the "Versailles diktat", and the belief in an international threat aimed at the elimination of the German nation persisted at the heart of German politics. Even a man of peace such as [Gustav] Stresemann publicly rejected German guilt. As for the Nazis, they waved the banners of domestic treason and international conspiracy in an attempt to galvanise the German nation into a spirit of revenge. Like a Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany sought to redirect the memory of the war to the benefit of its policies.[230]

Meanwhile, new nations liberated from German rule viewed the treaty as a recognition of wrongs committed against small nations by much larger aggressive neighbours.[231]

Austria-Hungary was partitioned into several successor states, largely but not entirely along ethnic lines. Apart from Austria and Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Poland, Romania and Yugoslavia received territories from the Dual Monarchy (the formerly separate and autonomous Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia was incorporated into Yugoslavia). The details were contained in the treaties of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Trianon. As a result, Hungary lost 64% of its total population, decreasing from 20.9 million to 7.6 million, and losing 31% (3.3 out of 10.7 million) of its ethnic Hungarians.[232] According to the 1910 census, speakers of the Hungarian language included approximately 54% of the entire population of the Kingdom of Hungary. Within the country, numerous ethnic minorities were present: 16.1% Romanians, 10.5% Slovaks, 10.4% Germans, 2.5% Ruthenians, 2.5% Serbs and 8% others.[233] Between 1920 and 1924, 354,000 Hungarians fled former Hungarian territories attached to Romania, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia.[234]

The Russian Empire lost much of its western frontier as the newly independent nations of Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland were carved from it. Romania took control of Bessarabia in April 1918.[235]

National identities

[edit]After 123 years, Poland re-emerged as an independent country. The Kingdom of Serbia and its dynasty, as a "minor Entente nation" and the country with the most casualties per capita,[236][237][238] became the backbone of a new multinational state, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later renamed Yugoslavia. Czechoslovakia, combining the Kingdom of Bohemia with parts of the Kingdom of Hungary, became a new nation. Romania would unite all Romanian-speaking people under a single state, leading to Greater Romania.[239]

In Australia and New Zealand, the Battle of Gallipoli became known as those nations' "Baptism of Fire". It was the first major war in which the newly established countries fought, and it was one of the first times that Australian troops fought as Australians, not just subjects of the British Crown, and independent national identities for these nations took hold. Anzac Day, named after the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), commemorates this defining moment.[240][241]

In the aftermath of World War I, Greece fought against Turkish nationalists led by Mustafa Kemal, a war that eventually resulted in a massive population exchange between the two countries under the Treaty of Lausanne.[242] According to various sources,[243] several hundred thousand Greeks died during this period, which was tied in with the Greek genocide.[244]

Casualties

[edit]

The total number of military and civilian casualties in World War I was about 40 million: estimates range from around 15 to 22 million deaths[245] and about 23 million wounded military personnel, ranking it among the deadliest conflicts in human history. The total number of deaths includes between 9 and 11 million military personnel, with an estimated civilian death toll of about 6 to 13 million.[245][246]

Of the 60 million European military personnel who were mobilised from 1914 to 1918, an estimated 8 million were killed, 7 million were permanently disabled, and 15 million were seriously injured. Germany lost 15.1% of its active male population, Austria-Hungary lost 17.1%, and France lost 10.5%.[247] France mobilised 7.8 million men, of which 1.4 million died and 3.2 million were injured.[248] Approximately 15,000 deployed men sustained gruesome facial injuries, causing social stigma and marginalisation; they were called the gueules cassées (broken faces). In Germany, civilian deaths were 474,000 higher than in peacetime, due in large part to food shortages and malnutrition that had weakened disease resistance. These excess deaths are estimated as 271,000 in 1918, plus another 71,000 in the first half of 1919 when the blockade was still in effect.[249] Starvation caused by famine killed approximately 100,000 people in Lebanon.[250]

Diseases flourished in the chaotic wartime conditions. In 1914 alone, louse-borne epidemic typhus killed 200,000 in Serbia.[251] Starting in early 1918, a major influenza epidemic known as Spanish flu spread across the world, accelerated by the movement of large numbers of soldiers, often crammed together in camps and transport ships with poor sanitation. The Spanish flu killed at least 17 to 25 million people,[252][253] including an estimated 2.64 million Europeans and as many as 675,000 Americans.[254] Between 1915 and 1926, an epidemic of encephalitis lethargica affected nearly 5 million people worldwide.[255][256]

Eight million equines, mostly horses, donkeys and mules died, three-quarters of them from the extreme conditions they worked in.[257]

War crimes

[edit]Chemical weapons in warfare

[edit]

The German army was the first to successfully deploy chemical weapons during the Second Battle of Ypres (April–May 1915), after German scientists under the direction of Fritz Haber at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute developed a method to weaponise chlorine.[g][259] The use of chemical weapons had been sanctioned by the German High Command to force Allied soldiers out of their entrenched positions, complementing rather than supplanting more lethal conventional weapons.[259] Chemical weapons were deployed by all major belligerents throughout the war, inflicting approximately 1.3 million casualties, of which about 90,000 were fatal.[259] The use of chemical weapons in warfare was a direct violation of the 1899 Hague Declaration Concerning Asphyxiating Gases and the 1907 Hague Convention on Land Warfare, which prohibited their use.[260][261]

Genocides by the Ottoman Empire

[edit]

The ethnic cleansing of the Ottoman Empire's Armenian population, including mass deportations and executions, during the final years of the Ottoman Empire is considered genocide.[263] The Ottomans carried out organised and systematic massacres of the Armenian population at the beginning of the war and manipulated acts of Armenian resistance by portraying them as rebellions to justify further extermination.[264] In early 1915, several Armenians volunteered to join the Russian forces and the Ottoman government used this as a pretext to issue the Tehcir Law (Law on Deportation), which authorised the deportation of Armenians from the Empire's eastern provinces to Syria between 1915 and 1918. The Armenians were intentionally marched to death and a number were attacked by Ottoman brigands.[265] While the exact number of deaths is unknown, the International Association of Genocide Scholars estimates around 1.5 million.[263][266] The government of Turkey continues to deny the genocide to the present day, arguing that those who died were victims of inter-ethnic fighting, famine, or disease during World War I; these claims are rejected by most historians.[267]

Other ethnic groups were similarly attacked by the Ottoman Empire during this period, including Assyrians and Greeks, and some scholars consider those events to be part of the same policy of extermination.[268][269][270] At least 250,000 Assyrian Christians, about half of the population, and 350,000–750,000 Anatolian and Pontic Greeks were killed between 1915 and 1922.[271]

Prisoners of war

[edit]

About 8 million soldiers surrendered and were held in POW camps during the war. All nations pledged to follow the Hague Conventions on fair treatment of prisoners of war, and the survival rate for POWs was generally much higher than that of combatants at the front.[272]

Around 25–31% of Russian losses (as a proportion of those captured, wounded, or killed) were to prisoner status; for Austria-Hungary 32%; for Italy 26%; for France 12%; for Germany 9%; for Britain 7%. Prisoners from the Allied armies totalled about 1.4 million (not including Russia, which lost 2.5–3.5 million soldiers as prisoners). From the Central Powers, about 3.3 million soldiers became prisoners; most of them surrendered to Russians.[273]

Soldiers' experiences

[edit]Allied personnel was around 42,928,000, while Central personnel was near 25,248,000.[216] British soldiers of the war were initially volunteers but were increasingly conscripted. Surviving veterans returning home often found they could discuss their experiences only among themselves, so formed "veterans' associations" or "Legions".

Conscription

[edit]

Conscription was common in most European countries, but was controversial in English-speaking countries.[274] It was especially unpopular among minority ethnicities, especially the Irish Catholics in Ireland,[275] Australia,[276][page needed][277] and the French Catholics in Canada.[278][279]

In the US, conscription began in 1917 and was generally well-received, with a few pockets of opposition in isolated rural areas.[280][page needed] The administration decided to rely primarily on conscription, rather than voluntary enlistment, to raise military manpower after only 73,000 volunteers enlisted out of the initial 1 million target in the first six weeks of war.[281]

Military attachés and war correspondents

[edit]Military and civilian observers from every major power closely followed the course of the war.[282] Many were able to report on events from a perspective somewhat akin to modern "embedded" positions within the opposing land and naval forces.[283][284]

Economic effects

[edit]Macro- and micro-economic consequences devolved from the war. Families were altered by the departure of many men. With the death or absence of the primary wage earner, women were forced into the workforce in unprecedented numbers. At the same time, the industry needed to replace the lost labourers sent to war. This aided the struggle for voting rights for women.[285]

In all nations, the government's share of GDP increased, surpassing 50% in both Germany and France and nearly reaching that level in Britain. To pay for purchases in the US, Britain cashed in its extensive investments in American railroads and then began borrowing heavily from Wall Street. President Wilson was on the verge of cutting off the loans in late 1916 but allowed a great increase in US government lending to the Allies. After 1919, the US demanded repayment of these loans. The repayments were, in part, funded by German reparations that, in turn, were supported by American loans to Germany. This circular system collapsed in 1931 and some loans were never repaid. Britain still owed the United States $4.4 billion[h] of World War I debt in 1934; the last installment was finally paid in 2015.[286]

Britain turned to her colonies for help in obtaining essential war materials whose supply from traditional sources had become difficult. Geologists such as Albert Kitson were called on to find new resources of precious minerals in the African colonies. Kitson discovered important new deposits of manganese, used in munitions production, in the Gold Coast.[287]

Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles (the so-called "war guilt" clause) stated Germany accepted responsibility for "all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies."[288] It was worded as such to lay a legal basis for reparations, and a similar clause was inserted in the treaties with Austria and Hungary. However, neither of them interpreted it as an admission of war guilt.[289] In 1921, the total reparation sum was placed at 132 billion gold marks. However, "Allied experts knew that Germany could not pay" this sum. The total sum was divided into three categories, with the third being "deliberately designed to be chimerical" and its "primary function was to mislead public opinion ... into believing the 'total sum was being maintained.'"[290] Thus, 50 billion gold marks (12.5 billion dollars) "represented the actual Allied assessment of German capacity to pay" and "therefore ... represented the total German reparations" figure that had to be paid.[290]

This figure could be paid in cash or in-kind (coal, timber, chemical dyes, etc.). Some of the territory lost—via the Treaty of Versailles—was credited towards the reparation figure as were other acts such as helping to restore the Library of Louvain.[291] By 1929, the Great Depression caused political chaos throughout the world.[292] In 1932 the payment of reparations was suspended by the international community, by which point Germany had paid only the equivalent of 20.598 billion gold marks.[293] With the rise of Adolf Hitler, all bonds and loans that had been issued and taken out during the 1920s and early 1930s were cancelled. David Andelman notes "Refusing to pay doesn't make an agreement null and void. The bonds, the agreement, still exist." Thus, following the Second World War, at the London Conference in 1953, Germany agreed to resume payment on the money borrowed. On 3 October 2010, Germany made the final payment on these bonds.[i]

The Australian prime minister, Billy Hughes, wrote to the British prime minister, David Lloyd George, "You have assured us that you cannot get better terms. I much regret it, and hope even now that some way may be found of securing agreement for demanding reparation commensurate with the tremendous sacrifices made by the British Empire and her Allies." Australia received £5,571,720 in war reparations, but the direct cost of the war to Australia had been £376,993,052, and, by the mid-1930s, repatriation pensions, war gratuities, interest and sinking fund charges were £831,280,947.[298]

Support and opposition for the war

[edit]Support

[edit]

In the Balkans, Yugoslav nationalists such as the leader, Ante Trumbić, strongly supported the war, desiring the freedom of Yugoslavs from Austria-Hungary and other foreign powers and the creation of an independent Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav Committee, led by Trumbić, was formed in Paris on 30 April 1915, but shortly moved its office to London.[299] In April 1918, the Rome Congress of Oppressed Nationalities met, including Czechoslovak, Italian, Polish, Transylvanian, and Yugoslav representatives who urged the Allies to support national self-determination for the peoples residing within Austria-Hungary.[300]

In the Middle East, Arab nationalism soared in Ottoman territories in response to the rise of Turkish nationalism during the war. Arab nationalist leaders advocated the creation of a pan-Arab state. In 1916, the Arab Revolt began in Ottoman-controlled territories of the Middle East to achieve independence.[301]

In East Africa, Iyasu V of Ethiopia was supporting the Dervish state who were at war with the British in the Somaliland campaign.[302] Von Syburg, the German envoy in Addis Ababa, said, "now the time has come for Ethiopia to regain the coast of the Red Sea driving the Italians home, to restore the Empire to its ancient size." The Ethiopian Empire was on the verge of entering World War I on the side of the Central Powers before Iyasu's overthrow at the Battle of Segale due to Allied pressure on the Ethiopian aristocracy.[303]

Several socialist parties initially supported the war when it began in August 1914.[300] But European socialists split on national lines, with the concept of class conflict held by radical socialists such as Marxists and syndicalists being overborne by their patriotic support for the war.[304] Once the war began, Austrian, British, French, German, and Russian socialists followed the rising nationalist current by supporting their countries' intervention in the war.[305]