Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Poly(methyl methacrylate)

View on Wikipedia | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Poly(methyl 2-methylpropenoate)

| |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.112.313 |

| KEGG | |

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| (C5H8O2)n | |

| Molar mass | Varies |

| Density | 1.18 g/cm3[1] |

| −9.06×10−6 (SI, 22 °C)[2] | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.4905 at 589.3 nm[3] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) is a synthetic polymer derived from methyl methacrylate. It is a transparent thermoplastic used as an engineering plastic. PMMA is also known as acrylic, acrylic glass, as well as by the trade names and brands Crylux, Walcast, Hesalite, Plexiglas, Acrylite, Lucite, PerClax, and Perspex, among several others (see below). This plastic is often used in sheet form as a lightweight or shatter-resistant alternative to glass. It can also be used as a casting resin, in inks and coatings, and for many other purposes.

It is often technically classified as a type of glass in that it is a non-crystalline vitreous substance, hence its occasional historic designation as acrylic glass.

History

[edit]The first acrylic acid was created in 1843. Methacrylic acid, derived from acrylic acid, was formulated in 1865. The reaction between methacrylic acid and methanol results in the ester methyl methacrylate.

It was developed in 1928 in several different laboratories by many chemists, such as William R. Conn, Otto Röhm, and Walter Bauer, and first brought to market in 1933 by the German company Röhm & Haas AG (as of January 2019, part of Evonik Industries) and its partner and former U.S. affiliate Rohm and Haas Company under the trademark Plexiglas.[4]

Polymethyl methacrylate was discovered in the early 1930s by British chemists Rowland Hill and John Crawford at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in the United Kingdom.[citation needed] ICI registered the product under the trademark Perspex. About the same time, chemist and industrialist Otto Röhm of Röhm and Haas AG in Germany attempted to produce safety glass by polymerizing methyl methacrylate between two layers of glass. The polymer separated from the glass as a clear plastic sheet, which Röhm gave the trademarked name Plexiglas in 1933.[5] Both Perspex and Plexiglas were commercialized in the late 1930s. In the United States, E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company (now DuPont Company) subsequently introduced its own product under the trademark Lucite. In 1936 ICI Acrylics (now Lucite International) began the first commercially viable production of acrylic safety glass. During World War II both Allied and Axis forces used acrylic glass for submarine periscopes and aircraft windscreen, canopies, and gun turrets. Scraps of acrylic were also used to make clear pistol grips for the M1911A1 pistol or clear handle grips for the M1 bayonet or theater knives so that soldiers could put small photos of loved ones or pin-up girls' pictures inside. They were called "Sweetheart Grips" or "Pin-up Grips". Others were used to make handles for theater knives made from scrap materials.[6] Civilian applications followed after the war.[7]

Names

[edit]Common orthographic stylings include polymethyl methacrylate[8][9] and polymethylmethacrylate. The full IUPAC chemical name is poly(methyl 2-methylpropenoate), although it is a common mistake to use "an" instead of "en".

Although PMMA is often called simply "acrylic", acrylic can also refer to other polymers or copolymers containing polyacrylonitrile. Notable trade names and brands include Walcast, Acrylite, Altuglas,[10] Astariglas, Cho Chen, Crystallite, Cyrolite,[11] Hesalite (when used in Omega watches), Lucite,[12] Optix,[11] Oroglas,[13] PerClax, Perspex,[11] Plexiglas,[11][14] R-Cast, and Sumipex.

Properties

[edit]

PMMA is a strong, tough, and lightweight material. It has a density of 1.17–1.20 g/cm3,[1][15] which is approximately half that of glass, which is generally, depending on composition, 2.2–2.53 g/cm3.[1] It also has good impact strength, higher than both glass and polystyrene, but significantly lower than polycarbonate and some engineered polymers. PMMA ignites at 460 °C (860 °F) and burns, forming carbon dioxide, water, carbon monoxide, and low-molecular-weight compounds, including formaldehyde.[16]

PMMA is an economical alternative to polycarbonate (PC) when tensile strength, flexural strength, transparency, polishability, and UV tolerance are more important than impact strength, chemical resistance, and heat resistance. Additionally, PMMA does not contain the potentially harmful bisphenol-A subunits found in polycarbonate and is a far better choice for laser cutting.[17] It is often preferred because of its moderate properties, easy handling and processing, and low cost. Non-modified PMMA behaves in a brittle manner when under load, especially under an impact force, and is more prone to scratching than conventional inorganic glass, but modified PMMA is sometimes able to achieve high scratch and impact resistance.

PMMA transmits up to 92% of visible light (3 mm (0.12 in) thickness),[18] and gives a reflection of about 4% from each of its surfaces due to its refractive index (1.4905 at 589.3 nm).[3] It filters ultraviolet (UV) light at wavelengths below about 300 nm (similar to ordinary window glass). Some manufacturers[19] add coatings or additives to PMMA to improve absorption in the 300–400 nm range. PMMA passes infrared light of up to 2,800 nm and blocks IR of longer wavelengths up to 25,000 nm. Colored PMMA varieties allow specific IR wavelengths to pass while blocking visible light (for remote control or heat sensor applications, for example).

PMMA swells and dissolves in many organic solvents; it also has poor resistance to many other chemicals due to its easily hydrolyzed ester groups. Nevertheless, its environmental stability is superior to most other plastics such as polystyrene and polyethylene, and therefore it is often the material of choice for outdoor applications.[20]

PMMA has a maximum water absorption ratio of 0.3–0.4% by weight.[15] Tensile strength decreases with increased water absorption.[21] Its coefficient of thermal expansion is relatively high at (5–10)×10−5 °C−1.[22]

The Futuro house was made of fibreglass-reinforced polyester plastic, polyester-polyurethane, and poly(methylmethacrylate); one of them was found to be degrading by cyanobacteria and Archaea.[23][24]

PMMA can be joined using cyanoacrylate cement (commonly known as superglue), with heat (welding), or by using chlorinated solvents such as dichloromethane or trichloromethane[25] (chloroform) to dissolve the plastic at the joint, which then fuses and sets, forming an almost invisible weld. Scratches may easily be removed by polishing or by heating the surface of the material. Laser cutting may be used to form intricate designs from PMMA sheets. PMMA vaporizes to gaseous compounds (including its monomers) upon laser cutting, so a very clean cut is made, and cutting is performed very easily. However, the pulsed lasercutting introduces high internal stresses, which on exposure to solvents produce undesirable "stress-crazing" at the cut edge and several millimetres deep. Even ammonium-based glass-cleaner and almost everything short of soap-and-water produces similar undesirable crazing, sometimes over the entire surface of the cut parts, at great distances from the stressed edge.[26] Annealing the PMMA sheet/parts is therefore an obligatory post-processing step when intending to chemically bond lasercut parts together.

In the majority of applications, PMMA will not shatter. Rather, it breaks into large dull pieces. Since PMMA is softer and more easily scratched than glass, scratch-resistant coatings are often added to PMMA sheets to protect it (as well as possible other functions).

Pure poly(methyl methacrylate) homopolymer is rarely sold as an end product, since it is not optimized for most applications. Rather, modified formulations with varying amounts of other comonomers, additives, and fillers are created for uses where specific properties are required. For example:

- A small amount of acrylate comonomers are routinely used in PMMA grades destined for heat processing, since this stabilizes the polymer to depolymerization ("unzipping") during processing.

- Comonomers such as butyl acrylate are often added to improve impact strength.

- Comonomers such as methacrylic acid can be added to increase the glass transition temperature of the polymer for higher temperature use such as in lighting applications.

- Plasticizers may be added to improve processing properties, lower the glass transition temperature, improve impact properties, and improve mechanical properties such as elastic modulus [27]

- Dyes may be added to give color for decorative applications, or to protect against (or filter) UV light.

- Fillers may be substituted to reduce cost.

Synthesis and processing

[edit]Production

[edit]PMMA is routinely produced by emulsion polymerization, solution polymerization, and bulk polymerization. Generally, radical initiation is used (including living polymerization methods), but anionic polymerization of PMMA can also be performed.[28]

The glass transition temperature (Tg) of atactic PMMA is 105 °C (221 °F). The Tg values of commercial grades of PMMA range from 85 to 165 °C (185 to 329 °F); the range is so wide because of the vast number of commercial compositions that are copolymers with co-monomers other than methyl methacrylate. PMMA is thus an organic glass at room temperature; i.e., it is below its Tg. The forming temperature starts at the glass transition temperature and goes up from there.[29] All common molding processes may be used, including injection molding, compression molding, and extrusion. The highest quality PMMA sheets are produced by cell casting, but in this case, the polymerization and molding steps occur concurrently. The strength of the material is higher than molding grades owing to its extremely high molecular mass. Rubber toughening has been used to increase the toughness of PMMA to overcome its brittle behavior in response to applied loads.

Recycling

[edit]Plexiglass can be broken down with pyrolysis at a temperature of at least 400 °C (752 °F). The recovered monomers then are purified, but the costs and complexity have prevented this from becoming the norm.[30]

Another approach binds monomers to the ends of long polymer chains. Those monomers detach when heated, triggering the chain to disassemble, with monomer yields of up to 90%, although the presence of dyes reduce this number. However, polymers produced by this technology require special machinery and lack thermal stability.[30]

A third approach adds a chlorinated dichlorobenzene solvent to crushed Plexiglass. The mixture is heated to a modest 90–150 °C (194–302 °F) and exposed to ultraviolet light. The light splits a chlorine radical from the solvent, which breaks the polymer into monomers, which are purified via distillation, yielding virgin-grade stock. Even in the presence of additives, yields are 94 to 98%.[30]

Applications

[edit]

Being transparent and durable, PMMA is a versatile material and has been used in a wide range of fields and applications such as rear-lights and instrument clusters for vehicles, appliances, and lenses for glasses. PMMA in the form of sheets affords to shatter resistant panels for building windows, skylights, bulletproof security barriers, signs and displays, sanitary ware (bathtubs), LCD screens, furniture and many other applications. It is also used for coating polymers based on MMA provides outstanding stability against environmental conditions with reduced emission of VOC. Methacrylate polymers are used extensively in medical and dental applications where purity and stability are critical to performance.[28]

Glass substitute

[edit]

- PMMA is commonly used for constructing residential and commercial aquariums. Designers started building large aquariums when poly(methyl methacrylate) could be used. It is less often used in other building types due to incidents such as the Summerland disaster.

- PMMA is used for viewing ports and even complete pressure hulls of submersibles, such as the Alicia submarine's viewing sphere and the window of the bathyscaphe Trieste.

- PMMA is used in the lenses of exterior lights of automobiles.[31]

- Spectator protection in ice hockey rinks is made from PMMA.

- Historically, PMMA was an important improvement in the design of aircraft windows, making possible such designs as the bombardier's transparent nose compartment in the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Modern aircraft transparencies often use stretched acrylic plies.

- Police vehicles for riot control often have the regular glass replaced with PMMA to protect the occupants from thrown objects.

- PMMA is an important material in the making of certain lighthouse lenses.[32]

- PMMA was used for the roofing of the compound in the Olympic Park for the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. It enabled a light and translucent construction of the structure.[33]

- PMMA (under the brand name "Lucite") was used for the ceiling of the Houston Astrodome.

Daylight redirection

[edit]- Laser-cut acrylic panels have been used to redirect sunlight into a light pipe or tubular skylight and, from there, to spread it into a room.[34] Their developers Veronica Garcia Hansen, Ken Yeang, and Ian Edmonds were awarded the Far East Economic Review Innovation Award in bronze for this technology in 2003.[35][36]

- Attenuation being quite strong for distances over one meter (more than 90% intensity loss for a 3000 K source),[37] acrylic broadband light guides are then dedicated mostly to decorative uses.

- Pairs of acrylic sheets with a layer of microreplicated prisms between the sheets can have reflective and refractive properties that let them redirect part of incoming sunlight in dependence on its angle of incidence. Such panels act as miniature light shelves. Such panels have been commercialized for purposes of daylighting, to be used as a window or a canopy such that sunlight descending from the sky is directed to the ceiling or into the room rather than to the floor. This can lead to a higher illumination of the back part of a room, in particular when combined with a white ceiling, while having a slight impact on the view to the outside compared to normal glazing.[38][39]

Medicine

[edit]- PMMA has a good degree of compatibility with human tissue, and it is used in the manufacture of rigid intraocular lenses which are implanted in the eye when the original lens has been removed in the treatment of cataracts. This compatibility was discovered by the English ophthalmologist Harold Ridley in WWII RAF pilots, whose eyes had been riddled with PMMA splinters coming from the side windows of their Supermarine Spitfire fighters – the plastic scarcely caused any rejection, compared to glass splinters coming from aircraft such as the Hawker Hurricane.[40] Ridley had a lens manufactured by the Rayner company (Brighton & Hove, East Sussex) made from Perspex polymerised by ICI. On 29 November 1949 at St Thomas' Hospital, London, Ridley implanted the first intraocular lens.[41]

In particular, acrylic-type lenses are useful for cataract surgery in patients that have recurrent ocular inflammation (uveitis), as acrylic material induces less inflammation.

- Eyeglass lenses are commonly made from PMMA.

- Historically, hard contact lenses were frequently made of this material. Soft contact lenses are often made of a related polymer, where acrylate monomers containing one or more hydroxyl groups make them hydrophilic.

- In orthopedic surgery, PMMA bone cement is used to affix implants and to remodel lost bone.[42] It is supplied as a powder with liquid methyl methacrylate (MMA). Although PMMA is biologically compatible, MMA is considered to be an irritant and a possible carcinogen. PMMA has also been linked to cardiopulmonary events in the operating room due to hypotension.[43] Bone cement acts like a grout and not so much like a glue in arthroplasty. Although sticky, it does not bond to either the bone or the implant; rather, it primarily fills the spaces between the prosthesis and the bone preventing motion. A disadvantage of this bone cement is that it heats up to 82.5 °C (180.5 °F) while setting that may cause thermal necrosis of neighboring tissue. A careful balance of initiators and monomers is needed to reduce the rate of polymerization, and thus the heat generated.

- In cosmetic surgery, tiny PMMA microspheres suspended in some biological fluid are injected as a soft-tissue filler under the skin to reduce wrinkles or scars permanently.[44] PMMA as a soft-tissue filler was widely used in the beginning of the century to restore volume in patients with HIV-related facial wasting. PMMA is used illegally to shape muscles by some bodybuilders.

- Plombage is an outdated treatment of tuberculosis where the pleural space around an infected lung was filled with PMMA balls, in order to compress and collapse the affected lung.

- Emerging biotechnology and biomedical research use PMMA to create microfluidic lab-on-a-chip devices, which require 100 micrometre-wide geometries for routing liquids. These small geometries are amenable to using PMMA in a biochip fabrication process and offers moderate biocompatibility.

- Bioprocess chromatography columns use cast acrylic tubes as an alternative to glass and stainless steel. These are pressure rated and satisfy stringent requirements of materials for biocompatibility, toxicity, and extractables.

Dentistry

[edit]Due to its aforementioned biocompatibility, poly(methyl methacrylate) is a commonly used material in modern dentistry, particularly in the fabrication of dental prosthetics, artificial teeth, and orthodontic appliances.

- Acrylic prosthetic construction: Pre-polymerized, powdered PMMA spheres are mixed with a Methyl Methacrylate liquid monomer, Benzoyl Peroxide (initiator), and NN-Dimethyl-P-Toluidine (accelerator), and placed under heat and pressure to produce a hardened polymerized PMMA structure. Through the use of injection molding techniques, wax based designs with artificial teeth set in predetermined positions built on gypsum stone models of patients' mouths can be converted into functional prosthetics used to replace missing dentition. PMMA polymer and methyl methacrylate monomer mix is then injected into a flask containing a gypsum mold of the previously designed prosthesis, and placed under heat to initiate polymerization process. Pressure is used during the curing process to minimize polymerization shrinkage, ensuring an accurate fit of the prosthesis. Though other methods of polymerizing PMMA for prosthetic fabrication exist, such as chemical and microwave resin activation, the previously described heat-activated resin polymerization technique is the most commonly used due to its cost effectiveness and minimal polymerization shrinkage.

- Artificial teeth: While denture teeth can be made of several different materials, PMMA is a material of choice for the manufacturing of artificial teeth used in dental prosthetics. Mechanical properties of the material allow for heightened control of aesthetics, easy surface adjustments, decreased risk of fracture when in function in the oral cavity, and minimal wear against opposing teeth. Additionally, since the bases of dental prosthetics are often constructed using PMMA, adherence of PMMA denture teeth to PMMA denture bases is unparalleled, leading to the construction of a strong and durable prosthetic.[45]

Art and aesthetics

[edit]

- Acrylic paint essentially consists of PMMA suspended in water; however since PMMA is hydrophobic, a substance with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups needs to be added to facilitate the suspension.

- Modern furniture makers, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, seeking to give their products a space age aesthetic, incorporated Lucite and other PMMA products into their designs, especially office chairs. Many other products (for example, guitars) are sometimes made with acrylic glass to make the commonly opaque objects translucent.

- Perspex has been used as a surface to paint on, for example by Salvador Dalí.

- Diasec is a process which uses acrylic glass as a substitute for normal glass in picture frames. This is done for its relatively low cost, light weight, shatter-resistance, aesthetics and because it can be ordered in larger sizes than standard picture framing glass.

- As early as 1939, Los Angeles-based Dutch sculptor Jan de Swart experimented with samples of Lucite sent to him by DuPont; De Swart created tools to work the Lucite for sculpture and mixed chemicals to bring about certain effects of color and refraction.[46]

- From approximately the 1960s onward, sculptors and glass artists such as Jan Kubíček, Leroy Lamis, and Frederick Hart began using acrylics, especially taking advantage of the material's flexibility, light weight, cost and its capacity to refract and filter light.

- In the 1950s and 1960s, Lucite was an extremely popular material for jewelry, with several companies specialized in creating high-quality pieces from this material. Lucite beads and ornaments are still sold by jewelry suppliers.

- Acrylic sheets are produced in dozens of standard colors, most commonly sold using color numbers developed by Rohm & Haas in the 1950s.

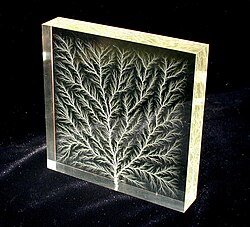

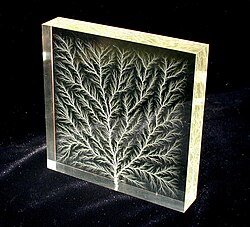

Methyl methacrylate "synthetic resin" for casting (simply the bulk liquid chemical) may be used in conjunction with a polymerization catalyst such as methyl ethyl ketone peroxide (MEKP), to produce hardened transparent PMMA in any shape, from a mold. Objects like insects or coins, or even dangerous chemicals in breakable quartz ampules, may be embedded in such "cast" blocks, for display and safe handling.

Other uses

[edit]

- PMMA, in the commercial form Technovit 7200 is used vastly in the medical field. It is used for plastic histology, electron microscopy, as well as many more uses.

- PMMA has been used to create ultra-white opaque membranes that are flexible and switch appearance to transparent when wet.[47]

- Acrylic is used in tanning beds as the transparent surface that separates the occupant from the tanning bulbs while tanning. The type of acrylic used in tanning beds is most often formulated from a special type of polymethyl methacrylate, a compound that allows the passage of ultraviolet rays.

- Sheets of PMMA are commonly used in the sign industry to make flat cut out letters in thicknesses typically varying from 3 to 25 millimeters (0.1 to 1.0 in). These letters may be used alone to represent a company's name and/or logo, or they may be a component of illuminated channel letters. Acrylic is also used extensively throughout the sign industry as a component of wall signs where it may be a backplate, painted on the surface or the backside, a faceplate with additional raised lettering or even photographic images printed directly to it, or a spacer to separate sign components.

- PMMA was used in Laserdisc optical media.[48] (CDs and DVDs use both acrylic and polycarbonate for impact resistance).

- It is used as a light guide for the backlights in TFT-LCDs.[49]

- Plastic optical fiber used for short-distance communication is made from PMMA, and perfluorinated PMMA, clad with fluorinated PMMA, in situations where its flexibility and cheaper installation costs outweigh its poor heat tolerance and higher attenuation versus glass fiber.

- PMMA, in a purified form, is used as the matrix in laser dye-doped organic solid-state gain media for tunable solid state dye lasers.[50]

- In semiconductor research and industry, PMMA aids as a resist in the electron beam lithography process. A solution consisting of the polymer in a solvent is used to spin coat silicon and other semiconducting and semi-insulating wafers with a thin film. Patterns on this can be made by an electron beam (using an electron microscope), deep UV light (shorter wavelength than the standard photolithography process), or X-rays. Exposure to these creates chain scission or (de-cross-linking) within the PMMA, allowing for the selective removal of exposed areas by a chemical developer, making it a positive photoresist. PMMA's advantage is that it allows for extremely high resolution patterns to be made. Smooth PMMA surface can be easily nanostructured by treatment in oxygen radio-frequency plasma[51] and nanostructured PMMA surface can be easily smoothed by vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) irradiation.[51]

- PMMA is used as a shield to stop beta radiation emitted from radioisotopes.

- Small strips of PMMA are used as dosimeter devices during the Gamma Irradiation process. The optical properties of PMMA change as the gamma dose increases, and can be measured with a spectrophotometer.

- Blacklight-reactive UV tattoos may use tattoo ink made with PMMA microcapsules and fluorescent dyes.[52]

- In the 1960s, luthier Dan Armstrong developed a line of electric guitars and basses whose bodies were made completely of acrylic. These instruments were marketed under the Ampeg brand. Ibanez[53] and B.C. Rich have also made acrylic guitars.

- Ludwig-Musser makes a line of acrylic drums called Vistalites, well known as being used by Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham.

- Artificial nails in the "acrylic" type often include PMMA powder.[54]

- Some modern briar, and occasionally meerschaum, tobacco pipes sport stems made of Lucite.

- PMMA technology is utilized in roofing and waterproofing applications. By incorporating a polyester fleece sandwiched between two layers of catalyst-activated PMMA resin, a fully reinforced liquid membrane is created in situ.

- PMMA is a widely used material to create deal toys and financial tombstones.

- PMMA is used by the Sailor Pen Company of Kure, Japan, in their standard models of gold-nib fountain pens, specifically as the cap and body material.

- Optical fibers made of PMMA are used by Fiber optic drone.[55][56]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA, Acrylic) Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine. Makeitfrom.com. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- ^ Wapler, M. C.; Leupold, J.; Dragonu, I.; von Elverfeldt, D.; Zaitsev, M.; Wallrabe, U. (2014). "Magnetic properties of materials for MR engineering, micro-MR and beyond". JMR. 242 (2014): 233–242. arXiv:1403.4760. Bibcode:2014JMagR.242..233W. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2014.02.005. PMID 24705364. S2CID 11545416.

- ^ a b Refractive index and related constants – Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA, Acrylic glass) Archived 2014-11-06 at the Wayback Machine. Refractiveindex.info. Retrieved 2014-10-27.

- ^ Plexiglas history by Evonik (in German)).

- ^ "DPMAregister | Marken - Registerauskunft". register.dpma.de. Retrieved 2021-09-29.

- ^ Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 77th Congress First Session (Volume 87, Part 11 ed.). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1941. pp. A2300 – A2302. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ "Polymethyl methacrylate". Archived from the original on 2017-10-31. Retrieved 2017-05-22.

- ^ "polymethyl methacrylate", Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier

- ^ "polymethyl methacrylate". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ David K. Platt (1 January 2003). Engineering and High Performance Plastics Market Report: A Rapra Market Report. Smithers Rapra. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-85957-380-8. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d Charles A. Harper; Edward M. Petrie (10 October 2003). Plastics Materials and Processes: A Concise Encyclopedia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-471-45920-0. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Trademark Electronic Search System". TESS. US Patent and Trademark Office. p. Search for Registration Number 0350093. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ "Misused materials stoked Sumerland fire". New Scientist. 62 (902). IPC Magazines: 684. 13 June 1974. ISSN 0262-4079. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016.

- ^ "WIPO Global Brand Database". Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- ^ a b DATA TABLE FOR: Polymers: Commodity Polymers: PMMA Archived 2007-12-13 at the Wayback Machine. Matbase.com. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

- ^ Zeng, W. R.; Li, S. F.; Chow, W. K. (2002). "Preliminary Studies on Burning Behavior of Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)". Journal of Fire Sciences. 20 (4): 297–317. doi:10.1177/073490402762574749. hdl:10397/31946. S2CID 97589855. INIST 14365060.

- ^ "Never cut these materials" (PDF).

- ^ McKeen, Laurence W. (2019). The effect of UV light and weather on plastics and elastomers (4th ed.). Washington, WA: Elsevier. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-1281-6457-0.

- ^ Altuglas International Plexiglas UF-3 UF-4 and UF-5 sheets Archived 2006-11-17 at the Wayback Machine. Plexiglas.com. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

- ^ Myer Ezrin Plastics Failure Guide: Cause and Prevention Archived 2016-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, Hanser Verlag, 1996 ISBN 1-56990-184-8, p. 168

- ^ Ishiyama, Chiemi; Yamamoto, Yoshito; Higo, Yakichi (2005). Buchheit, T.; Minor, A.; Spolenak, R.; et al. (eds.). "Effects of Humidity History on the Tensile Deformation Behaviour of Poly(methyl–methacrylate) (PMMA) Films". MRS Proceedings. 875 O12.7. doi:10.1557/PROC-875-O12.7.

- ^ "Tangram Technology Ltd. – Polymer Data File – PMMA". Archived from the original on 2010-04-21.

- ^ Cappitelli, Francesca; Principi, Pamela; Sorlini, Claudia (2006). "Biodeterioration of modern materials in contemporary collections: Can biotechnology help?". Trends in Biotechnology. 24 (8): 350–4. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.06.001. PMID 16782219.

- ^ Rinaldi, Andrea (2006). "Saving a fragile legacy. Biotechnology and microbiology are increasingly used to preserve and restore the world's cultural heritage". EMBO Reports. 7 (11): 1075–9. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400844. PMC 1679785. PMID 17077862.

- ^ "Working with Plexiglas" Archived 2015-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. science-projects.com.

- ^ Andersen, Hans J. "Tensions in acrylics when laser cutting". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ López, Alejandro; Hoess, Andreas; Thersleff, Thomas; Ott, Marjam; Engqvist, Håkan; Persson, Cecilia (2011-01-01). "Low-modulus PMMA bone cement modified with castor oil". Bio-Medical Materials and Engineering. 21 (5–6): 323–332. doi:10.3233/BME-2012-0679. ISSN 0959-2989. PMID 22561251.

- ^ a b Stickler, Manfred; Rhein, Thoma (2000). "Polymethacrylates". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_473. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ Ashby, Michael F. (2005). Materials Selection in Mechanical Design (3rd ed.). Elsevier. p. 519. ISBN 978-0-7506-6168-3.

- ^ a b c Coxworth, Ben (2025-03-03). "Simple technique may allow for almost complete recycling of Plexiglass". New Atlas. Retrieved 2025-03-05.

- ^ Kutz, Myer (2002). Handbook of Materials Selection. John Wiley & Sons. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-471-35924-1.

- ^ Terry Pepper, Seeing the Light, Illumination Archived 2009-01-23 at the Wayback Machine. Terrypepper.com. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

- ^ Deplazes, Andrea, ed. (2013). Constructing Architecture – Materials Processes Structures, A Handbook. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-03821-452-6.

- ^ Yeang, Ken. Light Pipes: An Innovative Design Device for Bringing Natural Daylight and Illumination into Buildings with Deep Floor Plan Archived 2009-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, Nomination for the Far East Economic Review Asian Innovation Awards 2003

- ^ "Lighting up your workplace". Fresh Innovators. May 9, 2005. Archived from the original on 2 July 2005.

- ^ Kenneth Yeang Archived 2008-09-25 at the Wayback Machine, World Cities Summit 2008, June 23–25, 2008, Singapore

- ^ Gerchikov, Victor; Mossman, Michele; Whitehead, Lorne (2005). "Modeling Attenuation versus Length in Practical Light Guides". LEUKOS. 1 (4): 47–59. doi:10.1582/LEUKOS.01.04.003. S2CID 220306943.

- ^ How Serraglaze works Archived 2009-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. Bendinglight.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

- ^ Glaze of light Archived 2009-01-10 at the Wayback Machine, Building Design Online, June 8, 2007

- ^ Robert A. Meyers, "Molecular biology and biotechnology: a comprehensive desk reference", Wiley-VCH, 1995, p. 722 ISBN 1-56081-925-1

- ^ Apple, David J (2006). Sir Harold Ridely and His Fight for Sight: He Changed the World So That We May Better See It. Thorofare NJ USA: Slack. ISBN 978-1-55642-786-2.

- ^ Carroll, Gregory T.; Kirschman, David L. (2022-07-13). "A portable negative pressure unit reduces bone cement fumes in a simulated operating room". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 11890. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1211890C. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-16227-x. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9279392. PMID 35831355.

- ^ Kaufmann, Timothy J.; Jensen, Mary E.; Ford, Gabriele; Gill, Lena L.; Marx, William F.; Kallmes, David F. (2002-04-01). "Cardiovascular Effects of Polymethylmethacrylate Use in Percutaneous Vertebroplasty". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 23 (4): 601–4. PMC 7975098. PMID 11950651.

- ^ "Filling in Wrinkles Safely". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. February 28, 2015. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Zarb, George Albert (2013). Prosthodontic treatment for edentulous patients: complete dentures and implant-supported prostheses (13th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-07844-3. OCLC 773020864.

- ^ de Swart, Ursula. My Life with Jan. Collection of Jock de Swart, Durango, CO

- ^ Syurik, Julia; Jacucci, Gianni; Onelli, Olimpia D.; Holscher, Hendrik; Vignolini, Silvia (22 February 2018). "Bio-inspired Highly Scattering Networks via Polymer Phase Separation". Advanced Functional Materials. 28 (24) 1706901. doi:10.1002/adfm.201706901.

- ^ Goodman, Robert L. (2002-11-19). How Electronic Things Work... And What to do When They Don't. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-142924-5.

PMMA Laserdisc.

- ^ Williams, K.S.; Mcdonnell, T. (2012), "Recycling liquid crystal displays", Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Handbook, Elsevier, pp. 312–338, doi:10.1533/9780857096333.3.312, ISBN 978-0-85709-089-8, retrieved 2022-06-27

- ^ Duarte, F. J. (Ed.), Tunable Laser Applications (CRC, New York, 2009) Chapters 3 and 4.

- ^ a b Lapshin, R. V.; Alekhin, A. P.; Kirilenko, A. G.; Odintsov, S. L.; Krotkov, V. A. (2010). "Vacuum ultraviolet smoothing of nanometer-scale asperities of poly(methyl methacrylate) surface". Journal of Surface Investigation. X-ray, Synchrotron and Neutron Techniques. 4 (1): 1–11. Bibcode:2010JSIXS...4....1L. doi:10.1134/S1027451010010015. S2CID 97385151.

- ^ Bedocs, Paul M.; Cliffel, Maureen; Mahon, Michael J.; Pui, John (March 2008). "Invisible tattoo granuloma". Cutis. 81 (3): 262–264. ISSN 0011-4162. PMID 18441850.

- ^ JS2K-PLT Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Ibanezregister.com. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

- ^ Symington, Jan (2006). "Salon management". Australian nail technology. Croydon, Victoria, Australia: Tertiary Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-86458-598-1.

- ^ Wang, Sherri; Chang, Rod. "Fiber-Optic drones revolutionize warfare but leave toxic footprint in Ukraine". digitimes.com. DigiTimes. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ Moreland, Leon. "Plastic pollution from fibre optic drones may threaten wildlife for years". Conflict and Environmental Observatory. Retrieved 29 May 2025.