Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Radiolaria

View on Wikipedia

| Radiolaria Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

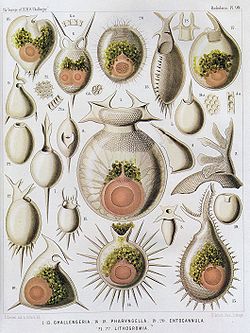

| Radiolaria illustration from the Challenger expedition 1873–76 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Sar |

| Clade: | Rhizaria |

| Phylum: | Retaria |

| Subphylum: | Radiolaria Cavalier-Smith, 1987 |

| Classes | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are unicellular eukaryotes of diameter 0.1–0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and ectoplasm. The elaborate mineral skeleton is usually made of silica.[1] They are found as zooplankton throughout the global ocean. As zooplankton, radiolarians are primarily heterotrophic, but many have photosynthetic endosymbionts and are, therefore, considered mixotrophs. The skeletal remains of some types of radiolarians make up a large part of the cover of the ocean floor as siliceous ooze. Due to their rapid change as species and intricate skeletons, radiolarians represent an important diagnostic fossil found from the Cambrian onwards.

Description

[edit]Radiolarians have many needle-like pseudopods supported by bundles of microtubules, which aid in the radiolarian's buoyancy. The cell nucleus and most other organelles are in the endoplasm, while the ectoplasm is filled with frothy vacuoles and lipid droplets, keeping them buoyant. The radiolarian can often contain symbiotic algae, especially zooxanthellae, which provide most of the cell's energy. Some of this organization is found among the heliozoa, but those lack central capsules and only produce simple scales and spines.

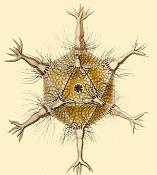

Some radiolarians are known for their resemblance to regular polyhedra, such as the icosahedron-shaped Circogonia icosahedra pictured below.

Taxonomy

[edit]The radiolarians belong to the supergroup Rhizaria together with (amoeboid or flagellate) Cercozoa and (shelled amoeboid) Foraminifera.[2] Traditionally the radiolarians have been divided into four groups—Acantharea, Nassellaria, Spumellaria and Phaeodarea. Phaeodaria is however now considered to be a Cercozoan.[3][4] Nassellaria and Spumellaria both produce siliceous skeletons and were therefore grouped together in the group Polycystina. Despite some initial suggestions to the contrary, this is also supported by molecular phylogenies. The Acantharea produce skeletons of strontium sulfate and is closely related to a peculiar genus, Sticholonche (Taxopodida), which lacks an internal skeleton and was for long time considered a heliozoan. The Radiolaria can therefore be divided into two major lineages: Polycystina (Spumellaria + Nassellaria) and Spasmaria (Acantharia + Taxopodida).[5][6]

There are several higher-order groups that have been detected in molecular analyses of environmental data. Particularly, groups related to Acantharia[7] and Spumellaria.[8] These groups are so far completely unknown in terms of morphology and physiology and the radiolarian diversity is therefore likely to be much higher than what is currently known.

The relationship between the Foraminifera and Radiolaria is also debated. Molecular trees support their close relationship—a grouping termed Retaria.[9] But whether they are sister lineages or whether the Foraminifera should be included within the Radiolaria is not known.

| Class | Order | Image | Families | Genera | Species | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polycystinea | Nassellaria |

|

... | |||

| Spumellaria |

|

... | ||||

| Collodaria |

|

... | ||||

| Acantharea |

|

... | ||||

| Sticholonchea | Taxopodida |

|

1 | 1 | 1 | ... |

Biogeography

[edit]

In the diagram on the right, a Illustrates generalized radiolarian provinces [10][11] and their relationship to water mass temperature (warm versus cool color shading) and circulation (gray arrows). Due to high-latitude water mass submergence under warm, stratified waters in lower latitudes, radiolarian species occupy habitats at multiple latitudes, and depths throughout the world oceans. Thus, marine sediments from the tropics reflect a composite of several vertically stacked faunal assemblages, some of which are contiguous with higher latitude surface assemblages. Sediments beneath polar waters include cosmopolitan deep-water radiolarians, as well as high-latitude endemic surface water species. Stars in (a) indicate the latitudes sampled, and the gray bars highlight the radiolarian assemblages included in each sedimentary composite. The horizontal purple bars indicate latitudes known for good radiolarian (silica) preservation, based on surface sediment composition.[12][13]

Data show that some species were extirpated from high latitudes but persisted in the tropics during the late Neogene, either by migration or range restriction (b). With predicted global warming, modern Southern Ocean species will not be able to use migration or range contraction to escape environmental stressors, because their preferred cold-water habitats are disappearing from the globe (c). However, tropical endemic species may expand their ranges toward midlatitudes. The color polygons in all three panels represent generalized radiolarian biogeographic provinces, as well as their relative water mass temperatures (cooler colors indicate cooler temperatures, and vice versa).[13]

-

Circogonia icosahedra, radiolarian species shaped like a regular icosahedron

-

Anthocyrtium hispidum Haeckel

Radiolarian shells

[edit]Radiolarians are unicellular predatory protists encased in elaborate globular shells (or "capsules"), usually made of silica and pierced with holes. Their name comes from the Latin for "radius". They catch prey by extending parts of their body through the holes. As with the silica frustules of diatoms, radiolarian shells can sink to the ocean floor when radiolarians die and become preserved as part of the ocean sediment. These remains, as microfossils, provide valuable information about past oceanic conditions.[14]

-

Like diatoms, radiolarians come in many shapes

-

Also like diatoms, radiolarian shells are usually made of silicate

-

However acantharian radiolarians have shells made from strontium sulfate crystals

-

Cutaway schematic diagram of a spherical radiolarian shell

-

Cladococcus abietinus

So I set to work on seeking a solution to the Morphogenesis Equations on a sphere. The theory was that a spherical organism was subject to diffusion across its surface membrane by an alien substance, eg sea-water. The Equations were:

The function , taken to be the radius vector from the centre to any point on the surface of the membrane, was argued to be representable as a series of normalised Legendre functions. The algebraic solution of the above equations ran to some 30 pages in my Thesis and are therefore not reproduced here. They are written in full in the book entitled "Morphogenesis" which is a tribute to Turing, edited by P. T. Saunders, published by North Holland, 1992.[16]

The algebraic solution of the equations revealed a family of solutions, corresponding to a parameter n, taking values 2, 4. 6.

When I had solved the algebraic equations, I then used the computer to plot the shape of the resulting organisms. Turing told me that there were real organisms corresponding to what I had produced. He said that they were described and depicted in the records of the voyages of HMS Challenger in the 19th Century.

I solved the equations and produced a set of solutions which corresponded to the actual species of Radiolaria discovered by HMS Challenger in the 19th century. That expedition to the Pacific Ocean found eight variations in the growth patterns. These are shown in the following figures. The essential feature of the growth is the emergence of elongated "spines" protruding from the sphere at regular positions. Thus the species comprised two, six, twelve, and twenty, spine variations.

Diversity and morphogenesis

[edit]Bernard Richards, worked under the supervision of Alan Turing (1912–1954) at Manchester as one of Turing's last students, helping to validate Turing's theory of morphogenesis.[18][19][20][21]

"Turing was keen to take forward the work that D'Arcy Thompson had published in On Growth and Form in 1917".[20]

closely replicate some radiolarian shell patterns[22]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Spine variations in radiolarians as discovered by HMS Challenger in the 19th century and drawn by Ernst Haeckel

-

Cromyatractus tetracelyphus with 2 spines

-

Circopus sexfurcus with 6 spines

-

Circopurus octahedrus with 6 spines and 8 faces

-

Circogonia icosahedra with 12 spines and 20 faces

-

Circorrhegma dodecahedra with 20 (incompletely drawn) spines and 12 faces

-

Cannocapsa stethoscopium with 20 spines

The gallery shows images of the radiolarians as extracted from drawings made by the German zoologist and polymath Ernst Haeckel in 1887.

- Turing, Alan (1952). "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 237 (641): 37–72. Bibcode:1952RSPTB.237...37T. doi:10.1098/rstb.1952.0012. JSTOR 92463. S2CID 120437796.

- Richards, Bernard (2005-2006) "Turing, Richards and Morphogenesis", The Rutherford Journal, Volume 1.

Fossil record

[edit]The earliest known radiolaria date to the very start of the Cambrian period, appearing in the same beds as the first small shelly fauna—they may even be terminal Precambrian in age.[24][25][26][27] They have significant differences from later radiolaria, with a different silica lattice structure and few, if any, spikes on the test.[26] About ninety percent of known radiolarian species are extinct. The skeletons, or tests, of ancient radiolarians are used in geological dating, including for oil exploration and determination of ancient climates.[28]

Some common radiolarian fossils include Actinomma, Heliosphaera and Hexadoridium.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Smalley, I.J. (1963). "Radiolarians:construction of spherical skeleton". Science. 140 (3565): 396–397. Bibcode:1963Sci...140..396S. doi:10.1126/science.140.3565.396. PMID 17815802. S2CID 28616246.

- ^ Pawlowski J, Burki F (2009). "Untangling the phylogeny of amoeboid protists". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 56 (1): 16–25. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00379.x. PMID 19335771.

- ^ Yuasa T, Takahashi O, Honda D, Mayama S (2005). "Phylogenetic analyses of the polycystine Radiolaria based on the 18s rDNA sequences of the Spumellarida and the Nassellarida". European Journal of Protistology. 41 (4): 287–298. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2005.06.001.

- ^ Nikolaev SI, Berney C, Fahrni JF, et al. (May 2004). "The twilight of Heliozoa and rise of Rhizaria, an emerging supergroup of amoeboid eukaryotes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (21): 8066–71. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308602101. PMC 419558. PMID 15148395.

- ^ Krabberød AK, Bråte J, Dolven JK, et al. (2011). "Radiolaria divided into Polycystina and Spasmaria in combined 18S and 28S rDNA phylogeny". PLOS ONE. 6 (8) e23526. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623526K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023526. PMC 3154480. PMID 21853146.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (December 1993). "Kingdom protozoa and its 18 phyla". Microbiol. Rev. 57 (4): 953–94. doi:10.1128/mmbr.57.4.953-994.1993. PMC 372943. PMID 8302218.

- ^ Decelle J, Suzuki N, Mahé F, de Vargas C, Not F (May 2012). "Molecular phylogeny and morphological evolution of the Acantharia (Radiolaria)". Protist. 163 (3): 435–50. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2011.10.002. PMID 22154393.

- ^ Not F, Gausling R, Azam F, Heidelberg JF, Worden AZ (May 2007). "Vertical distribution of picoeukaryotic diversity in the Sargasso Sea". Environ. Microbiol. 9 (5): 1233–52. Bibcode:2007EnvMi...9.1233N. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01247.x. PMID 17472637.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (July 1999). "Principles of protein and lipid targeting in secondary symbiogenesis: euglenoid, dinoflagellate, and sporozoan plastid origins and the eukaryote family tree". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 46 (4): 347–66. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04614.x. PMID 18092388. S2CID 22759799.

- ^ Boltovskoy, D., Kling, S. A., Takahashi, K. & BjØrklund, K. (2010) "World atlas of distribution of recent Polycystina (Radiolaria)". Palaeontologia Electronica, 13: 1–230.

- ^ Casey, R. E., Spaw, J. M., & Kunze, F. R. (1982) "Polycystine radiolarian distribution and enhancements related to oceanographic conditions in a hypothetical ocean". Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull., 66: 319–332.

- ^ Lazarus, David B. (2011). "The deep-sea microfossil record of macroevolutionary change in plankton and its study". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 358 (1): 141–166. Bibcode:2011GSLSP.358..141L. doi:10.1144/SP358.10. S2CID 128826639.

- ^ a b Trubovitz, Sarah; Lazarus, David; Renaudie, Johan; Noble, Paula J. (2020). "Marine plankton show threshold extinction response to Neogene climate change". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5069. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5069T. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18879-7. PMC 7582175. PMID 33093493.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Wassilieff, Maggy (2006) "Plankton – Animal plankton", Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Accessed: 2 November 2019.

- ^ Kachovich, Sarah (2018) "Minds over Methods: Linking microfossils to tectonics" Blog of the Tectonics and Structural Geology Division of the European Geosciences Union.

- ^ Turing, Alan; Saunders, P. T. (1992). Morphogenesis (in Esperanto). Amsterdam: North-Holland. ISBN 978-0-08-093405-1. OCLC 680063781.

- ^ Richards, Bernard (2006) "Turing, Richards and Morphogenesis", The Rutherford Journal, Volume 1.

- ^ Richards, Bernard (1954), "The Morphogenesis of Radiolaria", MSc thesis, Manchester, UK: The University of Manchester

- ^ Richards, Bernard (2005). "Turing, Richards and morphogenesis". The Rutherford Journal. 1.

- ^ a b Richards, Bernard (2017). "Chapter 35 – Radiolaria: Validating the Turing theory". In Copeland, Jack; et al. (eds.). The Turing Guide. pp. 383–388.

- ^ Copeland, Jack; Bowen, Jonathan; Sprevak, Mark; Wilson, Robin; et al. (2017). "Notes on Contributors". The Turing Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 478. ISBN 978-0-19-874783-3.

- ^ Varea, C.; Aragon, J.L.; Barrio, R.A. (1999). "Turing patterns on a sphere". Physical Review E. 60 (4): 4588–92. Bibcode:1999PhRvE..60.4588V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.60.4588. PMID 11970318.

- ^ Kachovich, S., Sheng, J. and Aitchison, J.C., 2019. Adding a new dimension to investigations of early radiolarian evolution. Scientific reports, 9(1), pp.1–10. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42771-0.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Chang, Shan; Feng, Qinglai; Zhang, Lei (14 August 2018). "New Siliceous Microfossils from the Terreneuvian Yanjiahe Formation, South China: The Possible Earliest Radiolarian Fossil Record". Journal of Earth Science. 29 (4): 912–919. Bibcode:2018JEaSc..29..912C. doi:10.1007/s12583-017-0960-0. S2CID 134890245.

- ^ Zhang, Ke; Feng, Qing-Lai (September 2019). "Early Cambrian radiolarians and sponge spicules from the Niujiaohe Formation in South China". Palaeoworld. 28 (3): 234–242. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2019.04.001. S2CID 146452469.

- ^ a b A. Braun; J. Chen; D. Waloszek; A. Maas (2007), "First Early Cambrian Radiolaria", in Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Komarower, Patricia (eds.), The Rise and Fall of the Ediacaran Biota, Special publications, vol. 286, London: Geological Society, pp. 143–149, doi:10.1144/SP286.10, ISBN 978-1-86239-233-5, OCLC 156823511

- ^ Maletz, Jörg (June 2017). "The identification of putative Lower Cambrian Radiolaria". Revue de Micropaléontologie. 60 (2): 233–240. Bibcode:2017RvMic..60..233M. doi:10.1016/j.revmic.2017.04.001.

- ^ Zuckerman, L.D., Fellers, T.J., Alvarado, O., and Davidson, M.W. "Radiolarians", Molecular Expressions, Florida State University, 4 February 2004.

- Zettler, Linda A.; Sogin, ML; Caron, DA (1997). "Phylogenetic relationships between the Acantharea and the Polycystinea: A molecular perspective on Haeckel's Radiolaria". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (21): 11411–6. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9411411A. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.21.11411. PMC 23483. PMID 9326623.

- López-García P, Rodríguez-Valera F, Moreira D (January 2002). "Toward the monophyly of Haeckel's radiolaria: 18S rRNA environmental data support the sisterhood of polycystinea and acantharea". Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 (1): 118–121. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003976. PMID 11752197.

- Adl SM, Simpson AG, Farmer MA, et al. (2005). "The New Higher Level Classification of Eukaryotes with Emphasis on the Taxonomy of Protists". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 52 (5): 399–451. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. PMID 16248873.

- Haeckel, Ernst (2005). Art Forms from the Ocean: The Radiolarian Atlas of 1862. Munich; London: Prestel Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7913-3327-4.

External links

[edit]- [1]Radiolarians

- Brodie, C. (February 2005). "Geometry and Pattern in Nature 3: The holes in radiolarian and diatom tests". Micscape (112). ISSN 1365-070X.

- Radiolaria.org

- Haeckel, Ernst (1862). Die Radiolarien (Rhizopoda radiaria). Berlin. Archived from the original on 2009-06-19. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Radiolaria—Droplet

- Tree Of Life—Radiolaria

- ^ Boltovskoy, Demetrio; Anderson, O. Roger; Correa, Nancy M. (2016). "Radiolaria and Phaeodaria". In Archibald, John M.; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Slamovits, Claudio H.; Margulis, Lynn; Melkonian, Michael; Chapman, David J.; Corliss, John O. (eds.). Handbook of the Protists. Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–33. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32669-6_19-1. ISBN 978-3-319-32669-6.

Radiolaria

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Characteristics

Radiolaria are a diverse group of amoeboid protists classified within the Rhizaria clade of the SAR supergroup, which encompasses Stramenopiles, Alveolates, and Rhizaria.[5] These primarily marine, planktonic, single-celled eukaryotes are ubiquitous in oceanic environments, ranging in size from approximately 0.1 mm to several millimeters, with some colonial forms reaching larger dimensions.[4] As heterotrophic or mixotrophic organisms, they obtain nutrition through phagocytosis, capturing prey such as bacteria, protists, and small metazoans, while certain species host photosynthetic endosymbionts like dinoflagellates to supplement their diet.[1][4] A defining feature of Radiolaria is their use of pseudopodia for locomotion, prey capture, and structural support, including axopodia—rigid, axoneme-supported extensions—and filopodia, which are finer, thread-like protrusions.[6] Most species possess biomineralized skeletons that provide rigidity and protection; for instance, Polycystinea feature intricate opaline silica structures, whereas Acantharia construct skeletons from strontium sulfate crystals.[1] These organisms exhibit a characteristic central capsule, a membranous structure that segregates the inner endoplasm—containing the nucleus and organelles—from the outer ectoplasm, which is involved in cytoplasmic streaming and pseudopodial activity.[2] Radiolaria are estimated to include thousands of extant species, though only hundreds have been formally described due to challenges in morphological and molecular identification, with metabarcoding revealing far greater diversity.[1][4] They play significant roles in marine biogeochemical cycles, particularly by exporting biogenic silica from surface waters to the deep ocean through sinking skeletons and contributing to the biological pump via organic carbon remineralization.[1][7]Historical Context

The German physiologist Johannes Müller is credited with the discovery of Radiolaria in 1858, when he published detailed observations of these marine protozoans collected from the Mediterranean Sea near St. Tropez.[8] He coined the term "Radiolaria" to describe their distinctive radial symmetry, particularly evident in the arrangement of their axopodia—slender, radiating cytoplasmic projections used for feeding and locomotion.[9] Müller's work, including "Über die Radiolarien des Mittelmeeres," laid the groundwork for recognizing Radiolaria as a distinct group of rhizopods characterized by a central capsule and skeletal elements.[10] Ernst Haeckel, one of Müller's students, advanced the study through pioneering microscopy in the mid-19th century, producing vivid artistic illustrations that highlighted their intricate forms.[8] His seminal 1887 monograph, "Report on the Radiolaria Collected by H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873-1876," synthesized global collections and described 739 genera and 4,318 species, with over 3,500 newly identified, emphasizing their morphological diversity.[8] Haeckel's depictions not only served scientific purposes but also influenced art and design, showcasing Radiolaria as exemplars of natural beauty and symmetry.[11] Early classifications faced challenges due to the group's morphological variability, with Haeckel proposing six orders—Thalassicollea, Sphaerozoea, Peripylea, Cannopylea, Cyrtoidea, and Phaeoidea—in his 1862 work based primarily on skeletal and cytoplasmic features.[8] Later revisions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries addressed these issues by separating Acantharia, distinguished by their strontium sulfate skeletons, from Polycystinea, which feature siliceous skeletons, refining the taxonomic framework to better reflect compositional differences.[12] The HMS Challenger expedition (1872–1876), the first global oceanographic survey, significantly expanded knowledge of Radiolaria's distribution by collecting samples from diverse marine environments, confirming their ubiquitous presence in oceans worldwide and contributing vast material for Haeckel's analysis.[4] This voyage underscored their role as key planktonic components, influencing subsequent marine biology research.[8]Taxonomy and Phylogeny

Classification Hierarchy

Radiolaria are placed within the eukaryotic supergroup Rhizaria, specifically in the phylum Retaria, which also encompasses Foraminifera, while Cercozoa forms a sister group.[13] The foundational classification system for Radiolaria was proposed by Ernst Haeckel in 1887, dividing them into four major legions based on skeletal morphology: Spumellaria, Nassellaria, Acantharia, and Phaeodaria.[14] This framework has been revised since the 2000s through integration of molecular phylogenetics and emended Linnaean ranks, resulting in a more streamlined hierarchy that excludes Phaeodaria (now classified within Cercozoa due to distinct ribosomal RNA signatures) and recognizes three primary classes: Acantharia, Polycystinea, and Taxopodida.[15] Acantharia, characterized by strontium sulfate skeletons, represent one class with approximately 150 extant species across about 50 genera; they are organized into four orders, including Acanthometrida (e.g., families like Acanthometridae with geometric radial spicules).[16][17] Polycystinea form the largest class, featuring opaline silica skeletons and encompassing over 7,500 described species (predominantly fossil records from the Mesozoic and Cenozoic), with extant diversity estimated at around 900 species; this class is subdivided into four orders—Spumellaria, Nassellaria, Collodaria, and Orodaria—with recent molecular evidence suggesting Collodaria nests within Nassellaria.[15][18] Representative families within Collodaria include Collosphaeridae, known for their organic lattice shells enclosing colonial forms. Orodaria is distinguished by exceptionally large siliceous skeletons.[15] Taxopodida constitutes a minor class with a single extant species, Sticholonche zanclea, distinguished by its axopodia and lack of a mineralized skeleton.[15] Phaeodaria, with organic-walled skeletons, were historically included but their placement remains debated in some morphological systems; however, molecular evidence supports their separation as a distinct rhizarian lineage outside core Radiolaria.[15]Molecular and Morphological Insights

Molecular phylogenetics has significantly advanced the understanding of Radiolaria relationships, with analyses of small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) and actin genes providing key evidence. Studies using SSU rRNA sequences have supported the monophyly of Polycystinea, a major subgroup characterized by siliceous skeletons, while indicating polyphyly for the broader Radiolaria when including groups like Acantharea and Phaeodaria.[19][20] Combined SSU rRNA and actin phylogenies further reinforce Rhizaria as the supergroup encompassing Radiolaria, highlighting evolutionary links but also divergences within the group.[21] These genetic markers have revealed deep phylogenetic splits, challenging traditional groupings and emphasizing the need for integrated approaches. A landmark 2025 morpho-molecular framework has synthesized extensive genetic and morphological data to delineate over 15 higher clades within Radiolaria, prompting a major taxonomic revision at high ranks into at least six primary groups, including nesting Collodaria within Nassellaria and identifying new clades (Rad-A, Rad-B, Rad-C) under Spasmaria, with Taxopodida placed in Rad-B.[22] This framework, based on multi-locus sequencing including 18S and 28S rRNA, correlates genetic lineages with biogeographic patterns and skeletal traits, estimating that current diversity assessments underestimate true species richness by a factor of 2–3 times due to cryptic forms revealed through metabarcoding surveys.[4] Metabarcoding of environmental DNA from marine plankton has uncovered numerous undescribed operational taxonomic units (OTUs), particularly in deep-sea and polar environments, underscoring the limitations of morphology-alone identifications.[1] The integration of morphological features with molecular data has been crucial for resolving these clades, with axopodial patterns—such as the arrangement and microtubular structure of axopodia—and skeletal ultrastructure examined via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) showing strong correlations to genetic clusters. For instance, variations in spicular systems and cortical shell geometries in Spumellaria and Nassellaria align with distinct ribosomal sequence branches, enabling finer delineations of evolutionary relationships.[23] However, challenges persist in addressing cryptic species diversity, where genetically distinct populations exhibit minimal morphological differences, complicating delimitation and potentially masking up to half of the total radiolarian diversity.[24] SEM analyses of skeletal microfabrics have helped bridge these gaps but highlight the need for broader sampling to capture intraspecific variation.[25] Recent taxonomic revisions from 2022 to 2025 have elevated several families and proposed splits within orders like Nassellaria, driven by biogeographic and molecular evidence. For example, Nassellaria has been subdivided into additional suborders based on latitudinal distribution patterns and actin gene divergences, reflecting adaptations to distinct oceanic provinces.[26] These updates, informed by time-calibrated phylogenies, have refined the classification of over 20 families, incorporating data from global expeditions to account for regional endemism.[24] Ongoing debates center on the exclusion of Phaeodaria from core Radiolaria, stemming from substantial genetic divergence observed in SSU rRNA phylogenies that place them outside Polycystinea and Spasmaria clusters. This polyphyletic positioning challenges Haeckel's historical Radiolaria monophyly, with some analyses suggesting Phaeodaria as a separate rhizarian lineage due to differences in skeletal composition and ribosomal signatures. Such exclusions underscore the evolving nature of radiolarian taxonomy, emphasizing genetic data's role in redefining group boundaries.[12]Morphology

Cellular Organization

Radiolaria exhibit a distinctive cellular architecture characterized by a central capsule, a membranous structure that divides the cytoplasm into an inner endoplasm and an outer ectoplasm. The central capsule, enclosed by a thin organic membrane perforated by pores, houses the endoplasm, which contains essential eukaryotic organelles such as the nucleus or nuclei, mitochondria for respiration, and Golgi apparatus for secretory functions including biochemical synthesis and vacuole formation. In contrast, the surrounding ectoplasm forms a frothy, alveolate layer filled with vacuoles that aid in buoyancy and digestion, along with fewer mitochondria and digestive vacuoles for processing captured prey. This division allows for specialized functions, with the endoplasm focused on core metabolic processes and the ectoplasm on peripheral activities like nutrient uptake and waste expulsion.[27][2][28] The ectoplasm extends outward as a network of pseudopodia, which are critical for locomotion, attachment, and feeding. Axopodia, stiff radial projections reinforced by axial bundles of microtubules, radiate from the cell surface and function primarily in prey capture by ensnaring small planktonic organisms. Rhizopodia, finer and more irregular extensions, are less branched than those in foraminifera and serve for substrate attachment in certain species, facilitating temporary adhesion during passive drifting. These pseudopodia also support the integration of symbiotic partners and waste dispersal, enhancing the cell's interaction with the marine environment.[27][28][29] Key organelles within the central capsule include one or more nuclei; for instance, species in the order Acantharia possess multiple nuclei, often numbering in the hundreds prior to reproduction, which supports their complex life cycles. The Golgi apparatus, located in the endoplasm, plays a role in organelle packaging and cellular secretion. Many radiolaria are mixotrophic, harboring symbiotic algae in the ectoplasm for supplemental nutrition via photosynthesis; examples include dinoflagellates such as Brandtodinium nutricula in nassellarians and collodarians, and haptophytes like Phaeocystis cordata in acantharians, which contribute significantly to the host's energy needs.[27][30][31] Radiolaria cells typically measure 50–500 μm in diameter, with solitary forms averaging around 100–300 μm and colonial variants potentially larger. They are generally non-motile plankton, relying on buoyancy from lipid droplets, vacuoles, and skeletal elements for passive flotation in ocean currents, though pseudopodia enable weak, localized movements such as surface clinging in laboratory settings.[32][28][27]Skeletal Structures

Radiolaria exhibit diverse skeletal compositions that reflect their taxonomic divisions and ecological adaptations. In the subclass Polycystinea, skeletons are primarily composed of opaline silica (SiO₂·nH₂O), formed through intracellular biomineralization within silica deposition vesicles (SDVs) where silicic acid polymerizes into structured lattices.[33] In contrast, Acantharia produce skeletons of strontium sulfate (celestite, SrSO₄), consisting of monocrystalline spicules that radiate from the cell center in symmetrical arrays.[34] Phaeodaria possess fragile siliceous skeletons composed primarily of opal silica with organic components, which degrade rapidly after cell death.[35] The morphogenesis of radiolarian skeletons involves precise geometrical patterning guided by cytoskeletal elements that template mineral deposition. Spumellaria often display radial symmetry, including dodecahedral arrangements in their spherical or polyhedral forms, achieved through sequential bridge and rim growth within SDVs.[36] Nassellaria exhibit greater morphological diversity, with over 20 distinct geometries ranging from simple conical spines to complex latticed cephalis structures, evolving from monoaxial body plans that complicate symmetry progressively during ontogeny.[37] These patterns arise from organic matrices that direct silica or celestite precipitation, ensuring species-specific intricacy without external molds.[38] Skeletal structures serve multiple functions, including mechanical protection against predation and structural support for pseudopodial extensions used in prey capture. In many species, the porous lattices enhance buoyancy by balancing density with increased surface area, allowing vertical migration in the water column.[39] However, these skeletons are vulnerable to dissolution; siliceous forms in Polycystinea degrade in undersaturated deep waters below the lysocline, while celestite in Acantharia dissolves even faster in seawater, limiting fossil preservation to siliceous taxa.[28] The unique shapes also aid taxonomic identification, as they encode phylogenetic signals across the group's diversity.[1] Recent genomic studies have identified silicon transporter genes (SIT-L homologs) in polycystinean and phaeodarian radiolarians, analogous to those in diatoms, facilitating silicic acid uptake for biomineralization and highlighting convergent evolution in silica cycling.[40] Complementary 2025 research on silicon isotope fractionation in radiolarian skeletons further elucidates how these transporters influence isotopic signatures preserved in sediments, providing proxies for ancient ocean silica dynamics.[41]Ecology

Global Distribution

Radiolaria are ubiquitous throughout marine environments worldwide, primarily occupying pelagic zones from the sunlit surface waters to bathypelagic and abyssal depths, but they are notably absent from freshwater habitats.[1] Their distribution spans all latitudes, from polar to tropical regions, with the highest species diversity occurring in tropical and subtropical waters; for instance, polycystine radiolarians exhibit peak richness in equatorial Pacific assemblages, where abundances and variety are markedly elevated compared to higher latitudes.[1][42] Biogeographic patterns of Radiolaria reveal distinct provinces shaped by latitudinal gradients, with species richness decreasing progressively poleward from the equator toward the poles, reflecting a classic diversity trough in equatorial versus polar communities.[43] Many taxa display diel vertical migration within the upper 200 m, facilitating access to food resources and avoiding predators during daylight hours.[1] Acantharia tend to be surface-limited, concentrating in the oligotrophic upper layers of tropical and subtropical oceans, whereas Polycystinea often extend into deeper waters, with notable abundances below 100 m in both tropical and temperate zones.[44][42] Key environmental factors influencing Radiolarian distribution include water temperature, with optimum ranges of 15–25°C favoring many tropical and subtropical species; salinity levels of 35–38 psu in typical oceanic conditions; and silica availability, which is essential for the biosiliceous skeletons of groups like Spumellaria and Nassellaria.[1] Recent analyses confirm that low-latitude species richness has remained relatively high and stable over the past 10 million years, underscoring the resilience of equatorial assemblages to long-term climatic shifts.[45] In terms of abundance, populations can reach up to approximately 1400 individuals per cubic meter in the upper 100 m of tropical waters during peak periods, while Radiolaria contribute significantly to heterotrophic plankton biomass, accounting for around 12% of the total eukaryotic community in global surveys.[42]00495-6)Ecological Roles

Radiolaria occupy a central trophic position in marine planktonic food webs as phagotrophic heterotrophs, primarily consuming bacterioplankton, phytoplankton such as diatoms and dinoflagellates, and smaller protists like ciliates and tintinnids, with prey sizes typically ranging from 1 to 50 μm captured via their axopodia.[1] These axopodia, which are microtubule-supported pseudopods radiating from the cell surface, facilitate prey adhesion and transport to the cytostome for ingestion, enabling Radiolaria to act as key grazers in the microbial loop.[1] In turn, Radiolaria serve as prey for a diverse array of predators, including copepods (with at least 63 species documented to ingest them at frequencies of 0.01–1% in gut contents), fish larvae, and gelatinous zooplankton, thereby transferring energy and nutrients to higher trophic levels.[1] Biogeochemically, Radiolaria play a pivotal role in nutrient cycling, particularly as major contributors to biogenic silica export, where their siliceous skeletons account for a substantial portion of opal flux to deep-sea sediments—up to 50–80% in certain oligotrophic regions like the tropical oceans.[46] Through grazing, they facilitate carbon remineralization by repackaging organic matter into sinking fecal pellets and aggregates, exporting significant amounts of particulate organic carbon to depths beyond 3000 m, with episodic flux events contributing up to 60% of annual organic carbon delivery in some areas.[7] Approximately 20% of radiolarian species exhibit mixotrophy, hosting endosymbiotic photosynthetic algae such as dinoflagellates (e.g., Brandtodinium spp.) or haptophytes, which enhance host carbon acquisition via translocation of photosynthates while Radiolaria provide nutrients like ammonium and CO₂ to symbionts, thereby boosting overall primary production in nutrient-poor waters.[1][3] In community dynamics, Radiolaria function as keystone taxa in the microbial loop, linking bacterial production to larger grazers and influencing overall planktonic biodiversity through their high abundances—sometimes comprising over 12% of eukaryotic communities in global surveys.00495-6) Their assemblages serve as sensitive indicators of ocean health, with shifts in composition and size distributions observed in response to environmental stressors; for instance, recent studies highlight decreasing average test sizes and altered diversity patterns under ocean warming and acidification, potentially disrupting silica cycling and food web stability.[1] Radiolaria also engage in ecological interactions, including mutualistic symbioses with algae that promote host survival in stratified waters, and competitive dynamics with other silica-utilizing organisms like diatoms for dissolved silicate, which has historically driven evolutionary adaptations in shell morphology and weight.[1][47]Reproduction and Life Cycle

Reproductive Modes

Radiolaria primarily reproduce asexually, with binary fission involving the equal division of the central capsule and cytoplasm to produce two daughter cells, while multiple fission generates numerous offspring through the formation of swarmers or flagellated stages.[48][49][50] In binary fission, the parent cell is typically lost after the division of the nucleus and cytoplasm, ensuring rapid population growth under favorable conditions.[48] Species-specific variations highlight the diversity of asexual modes; Acantharia produce motile, biflagellated swarmers as part of multiple fission, often occurring annually and either directly from the adult stage or following encystment.[51][52] Sexual reproduction in Radiolaria is rare but supported by recent molecular evidence, particularly in Acantharia where transcriptomic analyses of swarmers reveal sexual cues and gamete-related genes, suggesting fusion of flagellated cells to form zygotes.[53][54] Nuclear dimorphism in some species further indicates possible gamete fusion, with reproduction predominantly parthenogenetic in others.[55] Alternation of generations, involving dimorphic sexual and asexual phases, has been hypothesized for certain Polycystinea, analogous to patterns observed in foraminifera.[56][57] Environmental factors influence these reproductive processes, with nutrient-rich conditions promoting fission for population expansion, while stress such as silica limitation triggers encystment as a survival mechanism prior to swarmer release in groups like Acantharia.[58][56]Developmental Processes

Radiolaria exhibit a holoplanktonic life cycle, remaining in the water column throughout their development without benthic phases. Their ontogeny involves progressive morphological and skeletal changes, with larval-like stages in certain groups transitioning to mature forms through growth and reorganization processes. In Acantharia, development begins with vegetative juveniles in surface waters, where celestite skeletons form via mineral deposition. These transition to a reproductive encystment phase, during which spicules are resorbed, and a dense celestite shell (up to 1 mm in diameter and 5–7 µm thick) develops, causing rapid sinking at rates up to 500 m per day to mesopelagic or bathypelagic depths. In deep waters, cysts release flagellated swarmer cells (2–3 µm), which fuse to produce new juveniles that ascend to upper layers for maturation and skeleton regrowth. This encystment-to-dispersal cycle facilitates vertical migration and nutrient acquisition, with cyst formation prominent in high-productivity regions.[59] For polycystine Radiolaria such as Spumellaria, ontogenetic development features stepwise skeletal addition of siliceous elements. Initial stages form a central microsphere, followed by the medullary shell (main chamber) and subsequent outer cortical shells or lattices connected by radial spines. Three distinct phases characterize this progression: a young stage with basic skeletal framework, a progressively growing stage involving incremental lattice expansion, and a fully grown stage with complete extracapsular structure. Post-fission cytoplasmic reorganization occurs after binary division, redistributing organelles and initiating new skeletal deposition in daughter cells. Overall lifespans in Radiolaria range from 2–3 weeks to 1–2 months, varying by species and environmental conditions. For instance, Spongaster tetras completes its cycle in at least one month, with maturation occurring over weeks via continuous skeleton accretion. Development is modulated by environmental factors, including temperature; in warm tropical waters, radiolarians respond sensitively to upper ocean conditions (top 25 m), potentially accelerating growth rates under elevated temperatures as observed in recent paleoceanographic proxies. Early developmental stages face predation risks from protists and metazoans, contributing to population turnover, though precise mortality rates remain understudied.[60]Evolutionary History

Fossil Record

The fossil record of Radiolaria begins in the Cambrian period around 540 million years ago (Ma), with the earliest evidence consisting of simple siliceous spicules preserved in sedimentary rocks. These initial forms indicate the emergence of skeletal structures in early radiolarian lineages, though the record remains sparse and fragmentary due to limited preservation. By the Ordovician period, approximately 485 Ma, significant diversification occurred, including the first appearance of polycystine radiolarians, marking a shift toward more complex skeletal architectures and expanded ecological roles in marine plankton.[61][62] Radiolarian tests, primarily composed of opaline silica, are preserved in lithologies such as cherts formed through diagenetic alteration of siliceous sediments and in deep-sea oozes that accumulate below the carbonate compensation depth. However, post-depositional dissolution in undersaturated seawater preferentially destroys fragile tests, biasing the fossil record toward robust, thick-walled forms and underrepresenting delicate or thin-shelled taxa. Comprehensive global records derive from ocean drilling expeditions, including Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) and Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) cores, which have recovered continuous sequences of radiolarian-bearing sediments from multiple ocean basins, enabling detailed biostratigraphic analyses.[63][64][65] Key events in the radiolarian fossil record include the Permian-Triassic mass extinction around 252 Ma, which resulted in approximately 96% species loss across marine ecosystems, severely decimating radiolarian diversity through prolonged environmental stress. This was followed by a major radiation during the Cretaceous period (145–66 Ma), with high diversity amid favorable oceanic conditions, and a post-dinosaur resurgence in the early Cenozoic after the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary event, leading to stable diversity levels that persist today. Exceptional abundances are evident in Miocene radiolarian earth deposits, such as the Monterey Formation in California, reflecting high productivity in upwelling zones. A 2023 analysis of Neogene radiolarian records further revealed no significant correlation between species abundance and extinction risk over multimillion-year timescales, highlighting the role of external environmental drivers in shaping long-term patterns.[66][67][68][69][70][45]Phylogenetic Evolution

Radiolaria belong to the supergroup Rhizaria, with molecular clock analyses indicating an origin for the group around 760 million years ago (Ma) during the Neoproterozoic era.[22] This deep phylogenetic placement positions Radiolaria as an early-diverging lineage within Rhizaria, predating the Cambrian explosion of skeletal forms. Acantharia represents a basal clade within Radiolaria, characterized by strontium sulfate skeletons, while the crown group of Polycystinea, encompassing Spumellaria and Nassellaria, diversified later, with siliceous skeletons emerging in the early Paleozoic.[71][72] Key divergences within Radiolaria occurred during the Paleozoic, including the split between Spumellaria and Nassellaria around 512 Ma.[73] This bifurcation coincided with adaptive radiations driven by increasing ocean oxygenation and elevated silica availability, enabling the evolution of intricate siliceous skeletal structures in polycystine lineages.[74] Fossil-calibrated molecular clocks further refine these timelines, dating the origin of Spumellaria to the middle Cambrian (ca. 515 Ma) and Nassellaria to the Devonian (ca. 420 Ma).[75] Recent 2025 molecular frameworks integrate metabarcoding and phylogenomic data to date major clades, revealing that modern Nassellaria diversified around 200 Ma in the Mesozoic, following the Permian-Triassic extinction.[72] Cryptic speciation in the Quaternary epoch has been inferred through allopatric processes, where geographic isolation in ocean basins promoted hidden genetic divergence without marked morphological changes.[76] Evolutionary patterns in Radiolaria exhibit high extinction and speciation rates, with turnover estimated at 20–30% per million years, reflecting dynamic responses to paleoceanographic shifts.[77] Diversity remains stable in tropical regions across geological timescales, while 2025 analyses show no consistent trends in skeletal size during major climate transitions, such as the Permian-Triassic boundary.[45]Scientific Significance

Paleoceanographic Applications

Radiolarian fossils serve as valuable proxies in paleoceanography due to their siliceous skeletons, which preserve well in marine sediments and reflect past oceanographic conditions through assemblage compositions and geochemical signatures. Shifts in radiolarian assemblages, particularly the abundance of warm-water species such as Spongaster tetras and Cycladophora davisiana, have been used to reconstruct sea surface temperatures (SSTs) with an accuracy of approximately ±2°C, enabling inferences about thermal gradients and circulation changes. A 2025 review of Quaternary radiolarian records from 33 sediment cores in the Northwest Pacific demonstrated the utility of these proxies for high-resolution SST reconstructions, highlighting species-specific responses to temperature variations during glacial-interglacial cycles.[60][78] Biogenic silica flux from radiolarian skeletons acts as an indicator of paleoproductivity, particularly in upwelling zones where nutrient-rich waters enhance siliceous plankton blooms. For instance, elevated opal accumulation in Benguela Current sediments correlates with periods of intensified upwelling and higher primary production during the late Miocene to Recent. Transfer functions derived from modern radiolarian distributions link species ratios—such as those between shallow-dwelling and deep-water taxa—to environmental parameters like salinity and dissolved oxygen levels, allowing quantitative estimates of past water mass properties with standard errors typically under 1-2 units for oxygen. These approaches have been applied across the Pacific to infer changes in stratification and ventilation.[79][80][81] Notable case studies illustrate the application of radiolarian proxies to major climatic transitions. During the Eocene-Oligocene boundary (~34 Ma), a pronounced faunal turnover in the Indian Ocean, marked by the decline of tropical species and rise of cosmopolitan cool-water forms, coincided with global cooling and the onset of Antarctic glaciation, reflecting a ~4-6°C drop in deep-water temperatures. In the Pliocene-Pleistocene, radiolarian migrations in the equatorial Pacific tracked ice age cycles, with poleward shifts of subtropical assemblages during interglacials and equatorward contractions in glacials, correlating with SST fluctuations of up to 5°C and intensified trade winds. These patterns provide evidence for ocean front migrations and polar amplification of climate variability.[82][83][84] Despite their strengths, radiolarian proxies face limitations from taphonomic biases, including dissolution in undersaturated bottom waters and selective preservation of robust skeletons, which can skew assemblage representations by up to 30-50% in silica-poor settings. Calibration challenges arise from regional ecological variations and the need for extensive modern analog datasets to minimize extrapolation errors in transfer functions. To address these, multi-proxy integrations with calcareous foraminifera enhance reliability, as seen in combined SST estimates from the Southern Ocean that reduce uncertainties by cross-validating siliceous and calcareous signals.[85][86][87]Modern Research Directions

Recent studies on Radiolaria in the context of climate change have revealed no consistent size responses among radiolarian species to warming events during the Paleozoic-Mesozoic transition, with geographic variations showing decreases in low-latitude forms and increases in mid- to high-latitude ones.[88] These findings, drawn from fossil records spanning millions of years, suggest that radiolarian communities can tolerate temperature changes over extended periods without widespread adverse effects, though rapid modern warming may exceed such thresholds. Assemblage shifts observed in historical data, including poleward range expansions of surviving species during past thermal stresses, suggest predictions of future migrations toward higher latitudes as oceans warm, potentially altering marine ecosystem structures.[89][90] Advances in molecular and genomic techniques have enhanced understanding of radiolarian diversity, with metabarcoding and morpho-molecular frameworks uncovering hidden taxonomic groups beyond traditional morphological classifications.[91] A 2025 study integrating these methods provides a comprehensive assessment of extant radiolarian diversity and biogeography, highlighting evolutionary histories that imply greater species richness than previously estimated, potentially doubling known counts through detection of cryptic lineages.[91] These approaches also support models of biomineralization processes and their evolutionary history in Radiolaria, though direct gene editing applications remain exploratory in related protist systems.[4] The intricate silica nanostructures of radiolarian skeletons have inspired biotechnological innovations, particularly in fabricating biomimetic nanomaterials for applications in drug delivery and environmental remediation.[92] Researchers have synthesized radiolaria-like mesoporous silica hollow spheres with radial spines using dynamic templating methods, mimicking the hierarchical architecture to enhance material porosity and surface area.[92] Ecological modeling of ocean acidification effects further explores thresholds for skeleton dissolution in siliceous plankton like Radiolaria, revealing that while silica is more resistant than carbonates, increased acidity could accelerate biogenic silica recycling at depths beyond 500 meters, impacting carbon and silicon cycles.[93][94] Future research directions emphasize integrating satellite remote sensing with in situ data to monitor radiolarian assemblages and detect large-scale distributional shifts or blooms in response to environmental perturbations.[1] Long-term observatories, such as those leveraging Tara Oceans expedition datasets, enable real-time tracking of protist communities, including Radiolaria, through molecular time-series analysis to assess ongoing climate impacts and biodiversity dynamics.[95][96] These efforts prioritize open-access resources for predictive modeling, fostering interdisciplinary approaches to marine protist ecology.[97]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Report_on_the_Radiolaria/Bibliography