Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Colored gold

View on Wikipedia

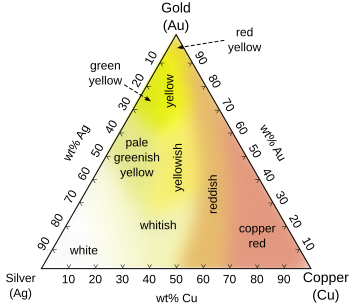

Colored gold is the name given to any gold that has been treated using techniques to change its natural color. Pure gold is slightly reddish yellow in color,[2] but colored gold can come in a variety of different colors by alloying it with different elements.

Colored golds can be classified in three groups:[3]: 118

- Alloys with silver and copper in various proportions, producing white, yellow, green and red golds. These are typically malleable alloys.

- Intermetallic compounds, producing blue and purple golds, as well as other colors. These are typically brittle, but can be used as gems and inlays.

- Surface treatments, such as oxide layers.

Pure 100% (in practice, 99.9% or better) gold is 24 karat by definition, so all colored golds are less pure than this, commonly 18K (75%), 14K (58.5%), 10K (41.6%), or 9K (37.5%).[4]

Alloys

[edit]White gold

[edit]

The word white covers a broad range of colors that borders or overlaps pale yellow, tinted brown, and even very pale rose. White gold is an alloy of gold and at least one white metal (usually nickel, silver, platinum or palladium).[5] Like yellow gold, the purity of white gold is given in karats.

Rose, red, and pink gold

[edit]

Rose gold is a gold-copper alloy[6] widely used for specialized jewelry. Rose gold, also known as pink gold and red gold, was popular in Russia at the beginning of the 19th century, and was also known as Russian gold.[7] Rose gold jewelry is becoming more popular in the 21st century, and is commonly used for wedding rings, bracelets, and other jewelry.

Although the names are often used interchangeably, the difference between red, rose, and pink gold is the copper content: the higher the copper content, the stronger the red coloration. Pink gold uses the least copper, followed by rose gold, with red gold having the highest copper content. Examples of the common alloys for 18K rose gold, 18K red gold, 18K pink gold, and 12K red gold include:[4]

- 18K red gold: 75% gold, 25% copper

- 18K rose gold: 75% gold, 22.25% copper, 2.75% silver

- 18K pink gold: 75% gold, 20% copper, 5% silver

- 12K red gold: 50% gold and 50% copper

Up to 15% zinc can be added to copper-rich alloys to change their color to reddish yellow or dark yellow.[3] 14K red gold, often found in the Middle East, contains 41.67% copper.

The highest karat version of rose gold, also known as crown gold, is 22 karat. Amongst the alloys made of gold, silver, and copper, the hardest is the 18.1 K pink gold (75.7% gold and 24.3% copper). An alloy with only gold and silver is the hardest at 15.5 K (64.5% gold and 35.5% silver).

During ancient times, due to impurities in the smelting process, gold frequently turned a reddish color. This is why many Greek and Roman texts, and some texts from the Middle Ages, describe gold as "red".[citation needed]

Spangold

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (July 2024) |

Some gold-copper-aluminium alloys form a fine surface texture at heat treatment, yielding a spangling effect. At cooling, they undergo a quasi-martensitic transformation from body-centered cubic to body-centered tetragonal phase; the transformation does not depend on the cooling rate. A polished object is heated in hot oil to 150–200 °C for 10 minutes then cooled below 20 °C, forming a sparkly surface covered with tiny facets.[3]

The alloy of 76% gold, 19% copper, and 5% aluminium yields a yellow color; the alloy of 76% gold, 18% copper, and 6% aluminium is pink.[3]

Green gold

[edit]Electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of silver and gold, develops a greenish cast with increasing silver content, ranging in color from green-yellow (for proportions of silver between 14% and 29%) to pale green-yellow (for proportions of silver between 29% and 50%).[8]: Fig. 2 It was known to the ancient Persians as long ago as 860 BC.[4] However, electrum was used even thousands of years before that, by both the Akkadians and Ancient Egyptians (as evidenced by the Royal Cemetery at Ur). Even the tops of some Egyptian pyramids were known to be capped in thin layers of electrum. Fired enamels adhere better to these alloys than to pure gold.

Cadmium can also be added to gold alloys to create a green color, but there are health concerns regarding its use, as cadmium is highly toxic.[9] Adding 2% cadmium to 18K red gold yields a light green color, whereas the alloy of 75% gold, 15% silver, 6% copper, and 4% cadmium is dark green.[3]

Gray gold

[edit]Gray gold alloys are usually made from gold and palladium.[citation needed] A cheaper alternative which does not use palladium is made by adding silver, manganese, and copper to the gold in specific ratios.[10]

Intermetallic

[edit]All the AuX2 intermetallics have the cubic fluorite (CaF2) crystal structure, and, therefore, are brittle.[3] Deviation from the stoichiometry results in loss of color. Slightly nonstoichiometric compositions are used, however, to achieve a fine-grained two- or three-phase microstructure with reduced brittleness. Another way of reducing brittleness is to add a small amount of palladium, copper, or silver.[11]

The intermetallic compounds tend to have poor corrosion resistance. The less noble elements are leached to the environment, and a gold-rich surface layer is formed. Direct contact of blue and purple gold elements with skin should be avoided as exposure to sweat may result in metal leaching and discoloration of the metal surface.[11]

Purple gold

[edit]

Purple gold (also called amethyst gold[citation needed] and violet gold[citation needed]) is an alloy of gold and aluminium rich in gold–aluminium intermetallic (AuAl2). Gold content in AuAl2 is around 79% and can therefore be referred to as 18 karat gold. Purple gold is more brittle than other gold alloys (called the "purple plague" when it forms and causes serious faults in electronics[12]), as it is an intermetallic compound instead of a malleable alloy, and a sharp blow may cause it to shatter.[13] It is therefore usually machined and faceted to be used as a "gem" in conventional jewelry rather than by itself. At a lower content of gold, the material is composed of the intermetallic and an aluminium-rich solid solution phase. At a higher content of gold, the gold-richer intermetallic AuAl forms; the purple color is preserved to about 15% of aluminium. At 88% of gold the material is composed of AuAl and changes color. The actual composition of AuAl2 is closer to Au6Al11 as the sublattice is incompletely occupied.[3]

Blue gold

[edit]Blue gold is an alloy of gold and either gallium or indium.[13] Gold-indium contains 46% gold (about 11 karat) and 54% indium,[4] forming an intermetallic compound AuIn2. While several sources remark this intermetallic to have "a clear blue color",[3] in fact the effect is slight: AuIn2 has CIE LAB color coordinates of 79, −3.7, −4.2[11] which appears roughly as a grayish color. With gallium, gold forms an intermetallic AuGa2 (58.5% Au, 14ct) which has slighter bluish hue. The melting point of AuIn2 is 541 °C, for AuGa2 it is 492 °C. AuIn2 is less brittle than AuGa2, which itself is less brittle than AuAl2.[11]

A surface plating of blue gold on karat gold or sterling silver can be achieved by a gold plating of the surface, followed by indium plating, with layer thickness matching the 1:2 atomic ratio. A heat treatment then causes interdiffusion of the metals and formation of the required intermetallic compound.

Surface treatments

[edit]Black gold

[edit]Black gold is a type of gold used in jewelry.[14][15] Black-colored gold can be produced by various methods:

- Patination by applying sulfur- and oxygen-containing compounds.

- Plasma-assisted chemical vapor deposition process involving amorphous carbon

- Controlled oxidation of gold containing chromium or cobalt (e.g. 75% gold, 25% cobalt[4]).

A range of colors from brown to black can be achieved on copper-rich alloys by treatment with potassium sulfide.[3]

Cobalt-containing alloys, e.g. 75% gold with 25% cobalt, form a black oxide layer with heat treatment at 700–950 °C. Copper, iron and titanium can be also used for such effect. Gold-cobalt-chromium alloy (75% gold, 15% cobalt, 10% chromium) yields a surface oxide that is olive-tinted because of the chromium(III) oxide content, is about five times thinner than Au-Co and has significantly better wear resistance. The gold-cobalt alloy consists of gold-rich (about 94% Au) and cobalt-rich (about 90% Co) phases; the cobalt-rich phase grains are capable of oxide-layer formation on their surface.[3]

More recently, black gold can be formed by creating nanostructures on the surface. A femtosecond laser pulse deforms the surface of the metal, creating an immensely increased surface area which absorbs virtually all the light that falls on it, thus rendering it deep black,[16] but this method is used in high technology applications rather than for appearance in jewelry. The blackness is due to the excitation of localized surface plasmons which creates strong absorption in a broad range in plasmon resonance. The broadness of the plasmon resonance, and absorption wavelength range, depends on the interaction between different gold nanoparticles.[17]

Blue gold

[edit]Oxide layers can also be used to obtain blue gold from an alloy of 75% gold, 24.4% iron, and 0.6% nickel; the layer forms on heat treatment in air between 450 and 600 °C.[3]

A rich sapphire blue colored gold of 20–23K can also be obtained by alloying with ruthenium, rhodium, and three other elements and heat-treating at 1800 °C, to form the 3–6 micrometers thick colored surface oxide layer.[3]

See also

[edit]- Corinthian bronze

- Crown gold

- Electrum

- Hepatizon

- List of alloys

- Mokume-gane, a mixed-metal laminate

- Orichalcum

- Panchaloha, alloys used for making Hindu temple icons

- Pyrite, often referred to as Fool's Gold

- Shakudō, copper with 4–10% gold

- Titanium gold

- Tumbaga

References

[edit]- ^ Woodrow Carpenter (June 1986). "Metals Suitable for Enameling". Glass on Metal Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- ^ Encyclopædia of Chemistry, theoretical, Practical, and Analytical: As Applied to the Arts and Manufactures. J. B. Lippincott & Company. 1880. pp. 70–.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cretu, Cristian; van der Lingen, Elma (December 1999). "Coloured gold alloys" (PDF). Gold Bulletin. 32 (4): 115–126. doi:10.1007/BF03214796. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-30.

- ^ a b c d e Emsley, John (2003). Nature's building blocks: an A–Z guide to the elements (Reprinted with corrections, 1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 168. ISBN 0-19-850340-7.

- ^ "White gold". Birmingham, UK: Assay Office. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Plumlee, Scott David (2014). Handcrafting Chain and Bead Jewelry: Techniques for Creating Dimensional Necklaces and Bracelets. Potter/TenSpeed/Harmony. ISBN 978-0-7704-3469-4.

- ^ Paris, Calin Van (2016-11-09). "Why Rose Gold's Romantic Glow Is Here to Stay". Allure. Retrieved 2024-07-09.

- ^ Rapson, William S. (December 1990). "The metallurgy of the coloured carat gold alloys". Gold Bulletin. 23 (4): 125–133. doi:10.1007/BF03214713.

- ^ Mead, M. N. (2010). "Cadmium confusion: Do consumers need protection?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 118 (12): a528–34. doi:10.1289/ehp.118-a528. PMC 3002210. PMID 21123140.

- ^ US 6576187, Ribault, Laurent & LeMarchand, Annie, "For manufacturing jewels by the disposable wax casting technique; does not cause allergies", issued 2003

- ^ a b c d Klotz, U. E. (2010). "Metallurgy and processing of coloured gold intermetallics — Part I: Properties and surface processing". Gold Bulletin. 43: 4–10. doi:10.1007/BF03214961.

- ^ "Purple plague" Archived 2014-05-04 at the Wayback Machine. International Electrotechnical Commission Glossary

- ^ a b "Gold In Purple Color, Blue Color And Even Black Gold". kaijewels.com.

- ^ "Jewellery Technology". World Gold Council. Archived from the original on March 3, 2006.

- ^ Rapson, W. S. (1978). Gold Usage. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-581250-4.

- ^ "Ultra-Intense Laser Blast Creates True 'Black Metal'". Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ ElKabbash, Mohamed; et al. (2017). "Tunable Black Gold: Controlling the Near-Field Coupling of Immobilized Au Nanoparticles Embedded in Mesoporous Silica Capsules". Advanced Optical Materials. 5 (21) 1700617. doi:10.1002/adom.201700617. S2CID 103781835.

External links

[edit] Media related to gold-containing alloys at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to gold-containing alloys at Wikimedia Commons