Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Earring

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

| Earrings | |

|---|---|

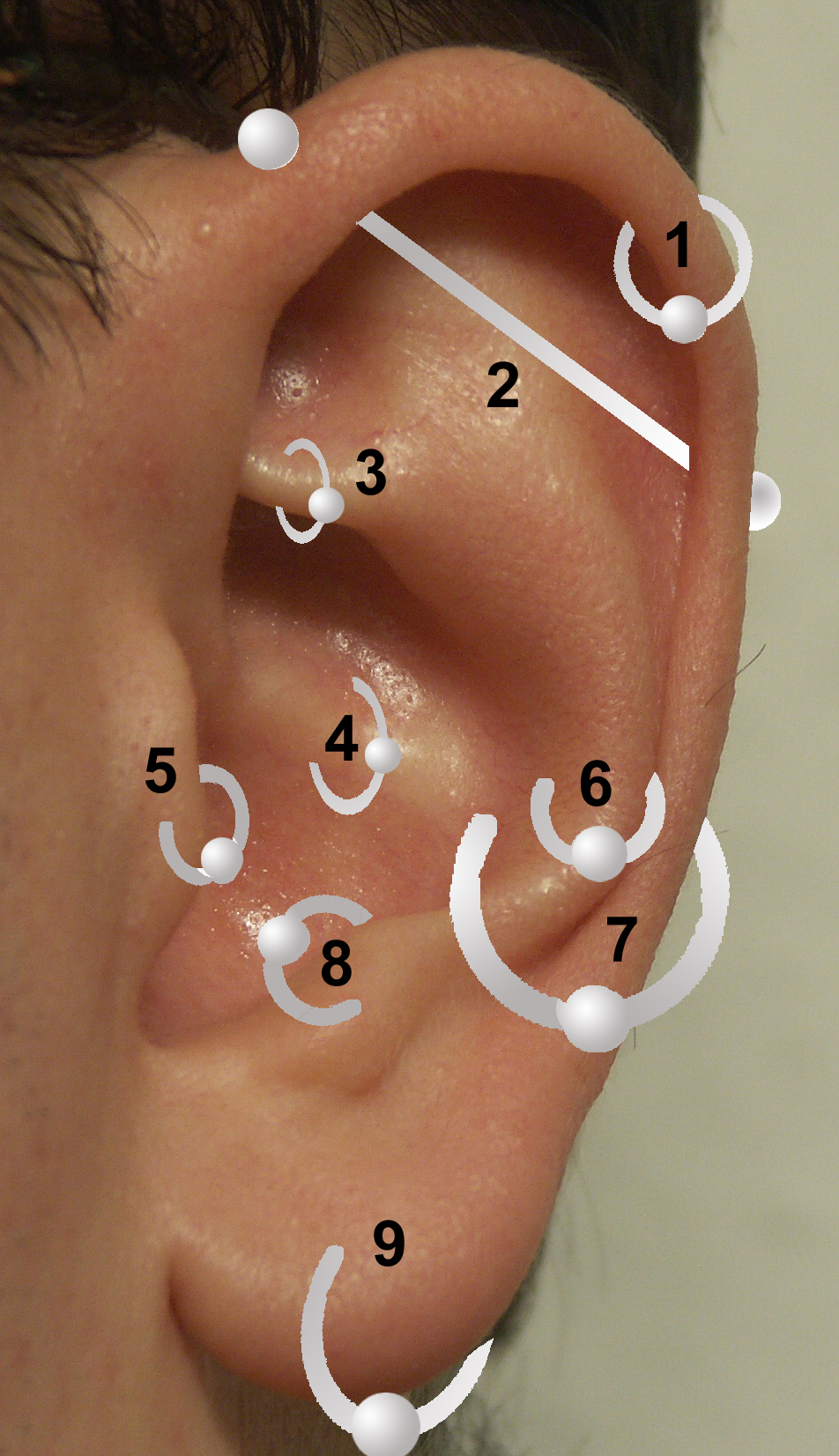

Earring locations on image: 1: helix; 2: industrial; 3: rook; 4: daith; 5: tragus; 6: snug; 7: conch; 8: anti-tragus; 9: earlobe | |

| Location | Ear |

| Jewelry | Captive bead ring, barbell, circular barbell, flesh plug |

| Healing | 6–12 months |

Earrings are jewelry that can be worn on one's ears. Earrings are commonly worn in a piercing in the earlobe[1] or another external part of the ear, or by some other means, such as stickers or clip-ons. Earrings have been worn across multiple civilizations and historic periods, often carrying a cultural significance. They are for both men and women.

Locations for piercings other than the earlobe include the rook, tragus, and across the helix (see image in the infobox). The simple term "ear piercing" usually refers to an earlobe piercing, whereas piercings in the upper part of the external ear are often referred to as "cartilage piercings". Cartilage piercings are more complex to perform than earlobe piercings and take longer to heal.[2]

Earring components may be made of any number of materials, including metal, plastic, glass, precious stone, beads, wood, bone, and other materials. Designs range from small hoops and studs to large plates and dangling items. The size is ultimately limited by the physical capacity of the earlobe to hold the earring without tearing. However, heavy earrings worn over extended periods of time can lead to stretching of the piercing; ear stretching can also be done intentionally.

History

[edit]

Ear piercing for the purpose of wearing earrings is one of the oldest known forms of body modification, with artistic and written references from cultures around the world dating back to early history. Gold earrings, along with other jewelry made of gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian were found in the ancient sites in Lothal, India,[4] and Sumerian Royal Cemetery at Ur from the Early Dynastic period.[5][6][7] Gold, silver and bronze hoop earrings were prevalent in the Minoan Civilization (2000–1600 BCE) and examples can be seen on frescoes on the Aegean island of Santorini, Greece. During the late Minoan and early Mycenaean periods of Bronze Age Greece hoop earrings with conical pendants were fashionable.[8] Early evidence of earrings worn by men can be seen in archeological evidence from Persepolis in ancient Persia. The carved images of soldiers of the Persian Empire, displayed on some of the surviving walls of the palace, show them wearing an earring.

Howard Carter writes in his description of Tutankhamun's tomb that the Pharaoh's earlobes were perforated, but no earrings were found inside the wrappings, although the tomb contained some. The burial mask's ears were perforated as well, but the holes were covered with golden discs. This implies that at the time, earrings were only worn in Egypt by children, much like in Egypt of Carter's times.[9]

Other early evidence of earring-wearing is evident in the Biblical record; gold earrings were a sign of wealth, but ear piercing was also used on slaves.[10] By the classical period, including in the Middle East, as a general rule, they were considered exclusively female ornaments. During certain periods in Greece and Rome also, earrings were worn mainly by women, though they were popular among men in early periods and had resurfaced later on, as famous figures like Plato were known to have worn them.[11][12][13]

The practice of wearing earrings was a tradition for Ainu men and women,[14] but the Government of Meiji Japan forbade Ainu men to wear earrings in the late-19th century.[15] Earrings were also commonplace among nomadic Turkic tribes and Korea. Lavish ear ornaments have remained popular in India from ancient times to the present day. And it was common that men and women wear earrings during Silla, Goryeo to Joseon.

In Western Europe, earrings became fashionable among English courtiers and gentlemen in the sixteenth century during the English Renaissance. Revealing of attitudes at the time, and commenting on the degeneracy of his contemporaries, Holinshed in his Chronicle (1577) observes: "Some lusty courtiers and gentlemen of courage do wear either rings of gold, stones or pearls in their ears, whereby they imagine the workmanship of God to be not a little amended."[16] Among sailors, a pierced earlobe was a symbol that the wearer had sailed around the world or had crossed the equator.[17]

Piercing the ears for wearing earrings is practical for two main reasons: first, wearing earrings in pierced ears for prolonged periods is far less uncomfortable than alternative means of attachment to the earlobe (such as clips), and second, the fastenings are generally more secure, which means that the risk of losing an earring is lower. However, styles and attitudes in the late 19th and the first half of the 20th century dictated that piercing one's ears was considered primitive, barbaric, or to be practised only within certain ethnic groups; thus earrings during this period were predominantly clip-ons. In 1951 Queen Elizabeth II had her ears pierced so that she could wear a pair of earrings given her as a wedding present, perhaps prompting many other women to follow suit. By the late 1950s or early 1960s, the practice of piercing the ears re-emerged in the Western world, among young women who wished to identify with the anti-materialist youth culture, and as an act of generational rebellion, especially those who had travelled to more distant or exotic locations.[18] Teenage girls held "ear-piercing parties", where they performed the procedure on one another. By the mid-1960s, with the invention of more modern ear-piercing devices, physicians began to offer ear piercing as a service;[19] simultaneously, Manhattan jewelry stores were some of the earliest commercial, non-medical locations for having one's ears pierced.[citation needed]

By the late 1960s, ear piercing began to make inroads among men through the hippie and gay communities, although they had been popular among sailors for decades (or longer).[20]

By the early 1970s, ear piercing had become fairly widespread among women, thus creating a broader market for the procedure. Throughout the United States, department stores would hold ear-piercing events, sponsored by manufacturers of earrings and ear-piercing devices. At these events, a nurse or other trained person would perform the procedure, using the ear-piercing device to pierce customers' earlobes with sharpened and sterilized starter earrings.

In the late 1970s, multiple piercings became popular in the punk rock community, and by the 1980s the trend for male popular music performers to have pierced ears helped establish a fashion trend for men; this was later adopted by many professional athletes. British men started piercing both ears in the 1980s, with George Michael of Wham! as a prominent example. By the early 21st century, it had become widely accepted for teenage boys and men to have either one or both ears pierced.

Multiple piercings in one or both ears first emerged in mainstream America in the 1970s. Initially, the trend was for women to wear a second set of earrings in the earlobes, or for men to double-pierce a single earlobe. Asymmetric styles with more and more piercings became popular, eventually leading to the cartilage-piercing trend from the 1990s onwards. Double ear piercing in newborn babies is a phenomenon in Central America, particularly in Costa Rica.

By the 1990s, boutique jewelry stores, such as Claire's and Piercing Pagoda, had become a mainstay of shopping malls in the United States, with inexpensive ear piercing via a multiplicity of styles of starter earrings as their primary offering, usually performed in plain view so as to demystify the procedure and present it as a quick, simple, exciting, and even enjoyable experience rather than as a painful ordeal, as it had often been characterized. This further popularised ear piercing, attracting both male and female customers, parents with younger children wanting their ears pierced, and encouraging repeat visits for multiple piercing, with teenage girls and young women as the primary target segment. Claire's claims it has performed over 100 million ear piercings, more than any other retailer.

From the 1990s onwards, with the increasing popularity of body piercing, a variety of specialized piercings in the ear other than the lobe had become popular; these require professional piercers who are trained with piercing techniques using bevelled piercing needles and specialised piercing jewellery rather than conventional ear-piercing instruments and basic starter studs. Such ear piercings include the tragus piercing, antitragus piercing, rook piercing, industrial piercing, helix piercing, orbital piercing, daith piercing, and conch piercing. In the 21st century this has further developed into the concept of ear curation, in which multiple piercings are "designed" for each customer to complement their ear shape, any existing piercings, and their desire for unique and personalised ear piercings and jewellery. Such designs are often referred to as "constellations", and some piercers have become renowned for their work with celebrities and influencers; as such, ear piercing has moved from the mainstream to having become a form of haute couture as it involves specialist practitioners, intricate designs, high-quality materials, and custom fitting.

In addition, earlobe stretching, while common in indigenous cultures for thousands of years, began to appear in Western society in the 1990s, and is now fairly common. However, this form of ear piercing is still infrequent compared to standard ear piercing, and may still be considered countercultural by some.

Types of earrings

[edit]Modern standard pierced earrings

[edit]Barbell earrings

[edit]Barbell earrings get their name from their resemblance to a barbell, generally coming in the form of a metal bar with an orb on either end. One of these orbs is affixed in place, while the other can be detached to allow the barbell to be inserted into a piercing. Several variations on this basic design exist, including barbells with curves or angles in the bar of the earring.

Claw earrings

[edit]The claw, talon or pincher is essentially a curved taper which is worn in stretched ear lobe piercings. The thickest end is generally flared and may be decorated, and a rubber o-ring may also be used to prevent the talon from becoming dislodged when worn. Common materials include acrylic and glass. A similar item of jewelry is the crescent, or pincher, which as the name suggests, is shaped like a crescent moon and is tapered at both ends. Talons and claws may also be quite ornamental (e.g.: carved in the form of a serpent or dragon). Consequently, they may prove to be an impractical choice of jewelry as they may snag on hair, clothing, etc.

Statement earrings

[edit]

Statement earrings can be defined as "earrings which invite attention from others by demonstrating bold, original, and unique designs with innovative construction and material combinations". They include one or more of the following design features:[21]

- Dangles

- Tassels

- Sparkles

- Bold or striking colours

- Hoops

Stud/minimal earrings

[edit]

The main characteristic of a stud earring is the appearance of floating on the ear or earlobe without a visible (from the front) point of connection. A stud earring features a gemstone or other ornament mounted on a narrow post that passes straight through a piercing in the ear or earlobe, which is held in place behind the ear by means of a removable friction back or clutch (sometimes referred to as a butterfly or scroll fitting).[22] To prevent their loss, the posts of some more expensive stud earrings made of precious metals or containing precious stones, such as solitaire diamonds, are threaded, allowing a screw back to hold the stud securely in place.

Heart earrings

[edit]Heart earrings are earrings in the form of the heart. They can be in the normal wearing degree and also they can be in a rotation of 180° wearing degree.

Hoop earrings

[edit]

Hoop earrings are circular or semi-circular in design and look very similar to a ring. Hoop earrings generally come in the form of a hoop of metal that can be opened to pass through the ear piercing. They are often constructed of metal tubing, with a thin wire attachment penetrating the ear. The hollow tubing is permanently attached to the wire at the front of the ear, and slips into the tube at the back. The entire device is held together by tension between the wire and the tube. Other hoop designs do not complete the circle, but penetrate through the ear in a post, using the same attachment techniques that apply to stud earrings. A variation is the continuous hoop earring. In this design, the earring is constructed of a continuous piece of solid metal, which penetrates through the ear and can be rotated almost 360°. One of the ends is permanently attached to a small piece of metallic tubing or a hollow metallic bead. The other end is inserted into the tubing or bead, and is held in place by tension. One special type of hoop earring is the sleeper earring, a circular wire normally made of gold, with a diameter of approximately one centimeter. Hinged sleepers, which were common in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s, comprise two semi-circular gold wires connected via a tiny hinge at one end, and fastened via a small clasp at the other, to form a continuous hoop whose fastening mechanism is effectively invisible to the naked eye. Because their small size makes them unobtrusive and comfortable, and because they are normally otherwise unadorned, sleepers are so-called because they were intended to be worn at night to keep a pierced ear from closing, and were often the choice for the first set of earrings immediately following the ear piercing in the decades before ear-piercing guns using studs became commonplace, but are often a fashion choice in themselves because of their attractive simplicity and because they subtly call attention to the fact that the ear is pierced.

Drop earrings

[edit]

A drop earring attaches to the earlobe and features a gemstone or ornament that dangles down from a chain, hoop, or similar object. The length of these ornaments vary from the very short to the extravagantly long. Such earrings are occasionally known as droplet earrings, dangle earrings, or pendant earrings. They also include chandelier earrings, which branch out into elaborate, multi-level pendants.

Chandelier earrings

[edit]

Chandelier earrings have an appearance similar to that of chandeliers, with a design that dangles below the ear and is wider at the base than the top.

Dangle earrings

[edit]

Dangle earrings (also known as drop earrings) are designed to suspend from the bottoms of the earlobes. Their lengths vary from a centimeter or two, all the way to brushing the wearer's shoulders. A pierced dangle earring is generally attached to the ear with a thin wire passing through the earlobe. It may connect to itself with a small hook at the back, or in the French hook design, the wire passes through the earlobe piercing without closure, although small plastic or silicone retainers are sometimes used on ends. Rarely, dangle earrings use the post attachment design. There are also variants that attach without piercing.

Huggy earrings

[edit]Huggy earrings are hoops that closely follow the curve of the earlobe, instead of dangling down beneath it as in regular hoop earrings. Commonly, stones are channel set in huggy earrings.

Ear thread

[edit]Ear thread, or earthreader, ear string, or threader earrings, are a chain that is thin enough to slip into the ear hole, dangling down at the back. Sometimes, people add beads or other materials onto the chain, so the chain dangles with beads below the ear.

Jhumka earrings

[edit]A type of dangling bell-shaped traditional earrings mostly worn by women of the Indian subcontinent.[citation needed] A jhumki is a traditional earring commonly worn in South Asia, especially in India and Pakistan. It features a bell-shaped design and is usually crafted from metals such as gold, silver, or brass, often adorned with detailed patterns and gemstones.

Body piercing jewelry used as earrings

[edit]

Body piercing jewelry is often used for ear piercings, and is selected for a variety of reasons including the availability of larger gauges, better piercing techniques, and a reduced risk of healing complications.

- Captive bead rings – Captive bead rings, often abbreviated as CBRs and sometimes called ball closure rings, are a style of body piercing jewelry that is an almost 360° ring with a small gap for insertion through the ear. The gap is closed with a small bead that is held in place by the ring's tension. Larger gauge ball closure rings exhibit considerable tension, and may require ring expanding pliers for insertion and removal of the bead.

- Barbells – Barbells are composed of a thin, straight metal rod with a bead permanently fixed to one end. The other end is threaded, either externally or tapped with an internal thread, and the other bead is screwed into place after the barbell is inserted through the ear. Since the threads on externally threaded barbells tend to irritate the piercing, internal threads have become the most common variety. Another variation are threadless barbells or press-fit jewelry, with a hollow post, a fixed back disk and a front end that is attached with a slightly bend pin that is inserted into the post.[23]

- Circular barbells – Circular barbells are similar to ball-closure rings, except that they have a larger gap, and have a permanently attached bead at one end, and a threaded bead at the other, like barbells. This allows for much easier insertion and removal than with ball closure rings, but at the loss of a continuous look.

- Plugs – Earplugs are short cylindrical pieces of jewelry. Some plugs have flared ends to hold them in place, others require small elastic rubber rings (O-rings) to keep them from falling out. They are usually used in large-gauge piercings.

- Flesh tunnels – Flesh tunnels, also known as eyelets or bullet holes, are similar to plugs; however, they are hollow in the middle. Flesh tunnels are most commonly used in larger gauge piercings either because weight is a concern to the wearer or for aesthetic reasons.

-

Stretched ear piercing without jewelry

-

16 mm (0.63 in) flesh tunnel

Gauges and other measuring systems

[edit]For an explanation of how earring sizes are denoted, see the article Body jewelry sizes.

Clip-on and other non-pierced earrings

[edit]

Several varieties of non-pierced earrings exist.

- Clip-on earrings – Clip-on earrings have existed longer than any other variety of non-pierced earrings. The clip itself is a two-part piece attached to the back of an earring. The two pieces closed around the earlobe, using mechanical pressure to hold the earring in place.

- Ear screws – Screwed onto the lobe, these can be adjusted for a more comfortable fit for those who find clip-on earrings otherwise too painful after prolonged wear. Ear screws may also be part of a clip design.

- Magnetic earrings – Magnetic earrings simulate the look of a (pierced) stud earring by attaching to the earlobe with a magnetic back that hold the earring in place on by magnetic force.

- Stick-on earrings – Stick-on earrings are adhesive-backed items which stick to the skin of the earlobe and simulate the look of a (pierced) stud earring. They are considered a novelty item.

- Spring hoop earrings – Spring hoops are almost indistinguishable from standard hoop earrings and stay in place by means of spring force.

- An alternative which is often used is bending a wire or even just using the ring portion of a CBR to put on the earlobe, which stays on by pinching the ear.

- Ear hook earrings – A large hook like the fish hook that is big enough to hook and hang over the whole ear and dangles.

- The hoop – A hoop threads over the ear and hangs from just inside the ear, above where ears are pierced. Mobiles or other dangles can be hung from the hoop to create a variety of styles.

- Ear cuffs – Wrap around the outer cartilage (similar to a conch piercing) and may be chained to a lobe piercing.

Permanent earrings

[edit]Where most earrings worn in the western world are designed to be removed easily to be changed at will, earrings can also be permanent (non-removable). They appear today in the form of larger gauge rings which are difficult or impossible for a person to remove without assistance. Occasionally, hoop earrings are permanently installed by the use of solder,[24] though this poses some risks due to toxicity of metals used in soldering and the risk of burns from the heat involved. Besides permanent installations, locking earrings are occasionally worn due to their personal symbolism or erotic value.

Ear piercing

[edit]Pierced ears have had one or more holes or "piercings" created in the earlobes or the cartilage portion of the external ears for the wearing of earrings. Piercings become permanent when the tract around the starter earring epithelializes[25] during the healing period following the initial piercing, and are sometimes mischaracterised as a fistula. The piercings do not form fully if the starter earrings are removed prematurely, or if earrings are not worn in the piercings for a longer period, depending on the recency with which the ear was pierced.

Conch piercing

[edit]A conch piercing is a perforation of the part of the external human ear called the "concha", the hollow next to the ear canal, for the purpose of inserting and wearing jewelry. Conch piercings have become popular among young women in recent decades as part of a trend for multiple ear piercings.[26]

Helix piercing

[edit]The helix piercing is a perforation of the helix or upper ear cartilage for the purpose of inserting and wearing a piece of jewelry. The piercing itself is usually made with a small gauge hollow piercing needle, and typical jewelry would be a small diameter captive bead ring, or a stud.[27]

Sometimes, two helix piercings hold the same piece of jewelry, usually a barbell, which is called an industrial piercing.

Like any other cartilage piercing, helix piercings may be painful to receive, and bumping or tugging on them by accident during healing can cause irritation. When they are left alone and not being irritated or touched, there is typically no discomfort. Piercers recommended avoiding unnecessary touching of helix piercings during healing, which can take 6 to 9 months.

Snug piercing

[edit]A snug (or antihelix) piercing is a piercing which passes through the anti-helix of the ear from the medial to lateral surfaces.[28]

Spiral piercing

[edit]

An ear spiral is a thick spiral that is usually worn through the earlobe. It is worn in ears that have been stretched and normally held in place only by its own downward pressure. Glass ear spirals are shown but many materials are used. Some designs are quite ornate and may include decorative appendages flaring from the underlying concentric pattern.

Piercing techniques

[edit]A variety of techniques are used to pierce ears, ranging from "do it yourself" methods using household items to medically sterile methods using specialized equipment.

A long-standing home method involves using ice as a local anesthetic, a sewing needle, a burning match or rubbing alcohol for disinfection, and a semi-soft object, such as a potato, cork, bar of soap, or rubber eraser, to hold the ear in place. Sewing thread may be drawn through the piercing and tied, as a device for keeping the piercing open during the healing process. Alternatively, a gold stud or wire earring may be directly inserted into the fresh piercing as the initial retaining device. Home methods are often unsafe and risky owing to improper sterilization and poor placement.

Another method for piercing ears, introduced in the 1960s, was the use of sharpened spring-loaded earrings known as self-piercers, trainers, or sleepers, which gradually pushed through the earlobe. However, these could easily slip from their initial placement position, often resulting in considerable discomfort, and often would not penetrate fully through the earlobe without additional pressure being applied. This method fell into disuse owing to the popularity of faster and more successful piercing techniques.

Ear-piercing instruments, sometimes called ear-piercing guns, were originally developed for physicians' use, but became widely used in retail settings.[29] Today more and more people in the Western world have their ears pierced with an ear-piercing instrument in specialty jewellery or accessory stores, in beauty salons and in pharmacies; however, some choose to do it at home using disposable ear-piercing kits. An earlobe piercing performed with an ear-piercing instrument is often described as feeling similar to being pinched, or being snapped by a rubber band. Piercing with this method, especially for cartilage piercings, is not recommended by many piercing professionals, as it is claimed by some to cause blunt-force trauma to the skin, and that it takes longer to heal than needle piercing. In addition, the external housing of most ear-piercing instruments is made of plastic, which cannot be sterilized in an Autoclave, potentially increasing the risk of infection. Piercing the cartilage of the ear with an ear-piercing instrument has been known to shatter the cartilage and lead to more serious complications.

An alternative method that has been growing in popularity since the 1990s is the use of the same hollow piercing needles that are used in body piercing. Some piercers may use a forceps or clamp to hold the earlobe during the piercing, while others pierce the ear freehand. After the desired placement of the piercing has been marked, the piercer positions the needle tip at the desired place and angle, and quickly pushes the needle fully through the earlobe. Immediately after the piercing, a cork can be placed on the needle tip behind the earlobe; if a cannula has been used, the needle is withdrawn, leaving the plastic sheath in place through the new piercing. Depending on the type of starting earring the client has selected, the piercer then inserts the jewellery into the end of the needle or cannula sheath, and guides it through the new piercing either forwards or backwards, and finally attaches either a clasp (for a standard earring post) or labret stud (if a flatback labret has been used). The piercer then disinfects the newly pierced lobe again. Once the piercing has been completed, the used needles and cannulas are then disposed of.

Regardless of whether their ear piercing is to be performed with an ear-piercing instrument or a needle, the client will first select their desired piercing jewellery, sign any consent forms, and is usually seated so that the piercer is able perform the piercing with ease. Ear-piercing practitioners normally disinfect the earlobe with alcohol prior to piercing, and mark the intended point of piercing, providing the client the opportunity to confirm that the position is correct, or to have the mark repositioned. Once the client agrees upon the intended placement of the piercing on the ear, the piercing is usually completed within a few minutes.

In tribal cultures and among some neo-primitive body-piercing enthusiasts, piercings are performed using other tools, such as animal or plant organics.

Initial healing time for an earlobe piercing is typically six to eight weeks. Subsequently, earrings can be changed, but if the piercing is left open for an extended period of time, there is some risk that it may close, requiring re-piercing. Piercing professionals recommend wearing earrings in newly pierced ears continuously for at least six months, and sometimes up to a year. Cartilage piercings require more healing time (up two to three times as long) than earlobe piercings. Even after fully healing, earlobe piercings tend to shrink in the prolonged absence of earrings, and may in some cases close.

Health risks

[edit]For ear piercing in general, it is now widely considered that the use of sterilized hollow piercing needles reduces both the trauma to the tissue and the chances of contracting a bacterial infection, and should be chosen as a method if it is available or practical (this may not be the case for younger children). As with any invasive procedure, there is a non-zero risk from ear piercing of infection from blood-borne pathogens such as hepatitis and HIV; however, modern piercing techniques make this risk extremely low. While there has never been a documented case of HIV transmission via piercing or tattooing, there have been instances of hepatitis transmission.[30]

With conventional earlobe piercing, there are common, but usually minor health risks that can be minimised if proper piercing techniques and hygienic procedures are observed. One study found that up to 35% of persons with pierced ears had one or more complications, including minor infection (77% of pierced-ear sites with complications), allergic reaction (43%), keloids (2.5%), and traumatic tearing (2.5%).[31] Tearing or splitting of the earlobe can be avoided by not wearing earrings during activities in which they are likely to become snagged, such as while playing sports. Hence, such activities should be avoided during the healing period following the piercing. Torn earlobes may require surgical repair.[32]

With cartilage piercing, it is commonly believed that piercing with a conventional piercing instrument and ear-piercing studs, which are not as sharp as bevelled piercing needles, can cause trauma to the cartilage, make healing more problematic. Further, because there is less blood flow in ear cartilage than in the earlobe, infection can become much more serious. Regardless of the piercing method, however, infections of the upper ear are commonly reported resulting following cartilage piercing.

Nickel in earrings worn in pierced ears is a significant risk factor for contact allergies,[33] and there is a correlation between the piercing of young girls' earlobes and the subsequent development of nickel allergies.[34][35][36]

Certain people have a predisposition to the formation of keloids following ear piercing, which often require dermatological intervention to address.

Religious and cultural use

[edit]According to Hindu dharma tradition, most girls and some boys (especially the "twice-born") get their ears pierced as part of a Dharmic rite known as Karnavedha before they are about five years old. Infants may get their ears pierced as early as several days after their birth.

Similar customs are practiced in other Asian countries, including Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Laos, although traditionally most males wait to get their ears pierced until they have reached young adulthood.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of earring". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ^ Davis, Jeanie. "Piercing? Stick to Earlobe". WebMD. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ Kleiner, Fred S. (2015). Gardner's Art through the Ages: Backpack Edition, Book A: Antiquity. [ ]: Cengage Learning. pp. 90–91. ISBN 9781305544895.

Two elegantly dressed young women bedecked with bracelets and hoop earrings gather crocuses. [...] Crocus gatherers, detail of the east wall of room 3 of building Xeste 3, Akrotiri, Thera (Cyclades) Greece, c. 1650-1625 BCE

- ^ Ornament in Indian Architecture. University of Delaware Press. 1991. p. 14. ISBN 9780874133998.

- ^ "Earring — ca. 2600–2500 B.C." MetMuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- ^ "Jewelry from The Royal Tombs of Ur". sumerianshakespeare.com. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- ^ "Queen Puabi's Headdress from the Royal Cemetery at Ur". Penn Museum. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- ^ Pitts-Taylor, Victoria (2008). Cultural Encyclopedia of the Body [2 volumes]. [ ]: ABC-CLIO. pp. 94–95. ISBN 9781567206913.

The Fayum mummy portraits from Hawara dating from the first to the third centuries CE depict several females with various styles of earrings. In most cases, the portraits are thought to represent Greek colonists living in Egypt. Some early Greeks wore earrings for the purposes of fashion as well as protection against evil. The popularity of earrings is evident in major cultures of the ancient world. In the middle Minoan period (2000–1600 BCE), gold, silver, and bronze hoop earrings with tapered ends were popular. In the late Minoan and early Mycenaean periods, the hoop evolved with a conical pendant.

- ^ The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen: Discovered by the Late Earl of Carnarvon and Howard Carter, Volume 3, pp. 74–75

- ^ Encyclopedia of Body Adornment, p. 94

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 798.

- ^ Notopoulos, James A. (1940). "Porphyry's Life of Plato". Classical Philology. 35 (3): 284–293. doi:10.1086/362396. ISSN 0009-837X. JSTOR 264394. S2CID 161160877.

- ^ "Perseus Under Philologic: Diog. Laert. 3.1.43". anastrophe.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-07. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ Sherrow, Victoria (2001). For appearance' sake: the historical encyclopedia of good looks, beauty, and grooming. Greenwood Publishing Group via Google Books. p. 101.

- ^ Ito, Masami (May 20, 2008). "Ainu: indigenous in every way but not by official fiat". The Japan Times. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Jewellery / by H. Clifford Smith, M.A.

- ^ Demello, Margo (2007). Encyclopedia of body adornment. Abc-Clio. ISBN 978-0-313-33695-9.

- ^ I Love Those Earrings: A Popular History from Ancient to Modern, Chris Filstrup, Jane Merrill

- ^ Beech, Georgina (2023-05-12). "100 Years Of Piercings". Glam. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ Hall, Trish (1991-05-19). "Piercing Fad Is Turning Convention on Its Ear". The New York Times.

- ^ Graves, Treva (2019-05-21). The Style File: A Woman's Guide to Dress for Success. Page Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-64462-832-4.

- ^ Erlanger, Micaela (2018-04-03). How to Accessorize: A Perfect Finish to Every Outfit. Clarkson Potter/Ten Speed. ISBN 978-1-5247-6115-8.

- ^ The Piercing Bible: The Definitive Guide to Safe Body Piercing, Elayne Angel Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale, 16 Feb 2011, p72

- ^ "No earrings give Cordone midas touch". BBC News. 2000-08-27. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ "Ear Piercing - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics".

- ^ Kale, Sirin (3 July 2019). "The curated ear: why delicate, decorative piercings are the new tattoos". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Edwards, Jess (13 December 2018). "Everything you need to know about helix piercings". Cosmopolitan. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ "Snug" Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine on BMEzine Encyclopedia Archived 2011-04-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Erica Weir (2001-03-20). "Canadian Medical Association Journal – Navel gazing: a clinical glimpse at body piercing". CMAJ. 164 (6): 864. PMC 80907. PMID 11276561. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "CDC Fact Sheet: HIV and Its Transmission". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-06-07. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ^ Meltzer DI (2005). "Complications of body piercing". Am Fam Physician. 72 (10): 2029–34. PMID 16342832. Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ^ Watson D. (Feb 2012). "Torn Earlobe Repair". Liver International. 35 (1): 187.

- ^ Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menné T, Johansen JD (2007). "The epidemiology of contact allergy in the general population—prevalence and main findings". Contact Dermatitis. 57 (5): 287–99. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01220.x. PMID 17937743. S2CID 44890665.

- ^ Harmful earrings (pl. Szkodliwe kolczyki) Fizjointormator. Retrieved 2015-04-01

- ^ "Polscy naukowcy ostrzegają: kolczyki szkodzą dzieciom" [Polish scientists warn: earrings harm children]. TVN24.pl (in Polish). 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2015-04-01.

- ^ Czarnobilska E.; Oblutowicz K.; Dyga W.; Wsołek-Wnek K.; Śpiewak R. (May 2009). "Contact hypersensitivity and allergic contact dermatitis among school children and teenagers with eczema". Contact Dermatitis. 60 (5): 264–269. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01537.x. PMID 19397618. S2CID 30920753.

Further reading

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 798–799. This source has a summary description of archaeological and artistic finds as of the early 20th century.

- Holmes, Anita, Pierced and Pretty: The Complete Guide to Ear Piercing, Pierced Earrings, and How to Create Your Own, William Morrow and Co., 1988. ISBN 0-688-03820-4.

- Jolly, Penny Howell, "Marked Difference: Earrings and 'The Other' in Fifteenth-Century Flemish Artwork," in Encountering Medieval Textiles and Dress: Objects, Texts, Images, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, pp. 195–208. ISBN 0-312-29377-1.

- Mascetti, Daniela and Triossi, Amanda, Earrings: From Antiquity to the Present, Thames and Hudson, 1999. ISBN 0-500-28161-0.

- McNab, Nan, Body Bizarre Body Beautiful, Fireside, 2001. ISBN 0-7432-1304-1.

- Mercury, Maureen and Haworth, Steve, Pagan Fleshworks: The Alchemy of Body Modification, Park Street Press, 2000. ISBN 0-89281-809-3.

- Steinbach, Ronald D., The Fashionable Ear: A History of Ear Piercing Trends for Men and Women, Vantage Press, 1995. ISBN 0-533-11237-0.

- Vale, V., Modern Primitives, RE/Search, 1989. ISBN 0-9650469-3-1

- van Cutsem, Anne, A World of Earrings: Africa, Asia, America, Skira, 2001. ISBN 88-8118-973-9.