Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Richard I of England

View on Wikipedia

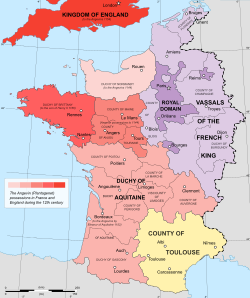

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199), known as Richard the Lionheart or Richard Cœur de Lion (Old Norman French: Quor de Lion)[2][3] because of his reputation as a great military leader and warrior,[4][b] was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine, and Gascony; Lord of Cyprus; Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes; and was overlord of Brittany at various times during the same period. He was the third of five sons of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine and was therefore not expected to become king, but his two elder brothers predeceased their father.

Key Information

By the age of 16, Richard had taken command of his own army, putting down rebellions in Poitou against his father.[4] Richard was an important Christian commander during the Third Crusade, leading the campaign after the departure of Philip II of France. Despite achieving several victories against his Muslim counterpart, Saladin, he was ultimately forced to end his campaign without retaking Jerusalem.[6]

Richard probably spoke both French and Occitan, and based on the testimony of Roger of Howden, most likely understood Middle English.[7] He was born in England, where he spent his childhood; before becoming duke of Aquitaine, however, he lived most of his adult life in the Duchy of Aquitaine, in the southwest of France. Following his accession to the crown of England, he spent very little time, perhaps as little as six months, in England. Most of his reign was spent on Crusade, in captivity, or actively defending the French portions of the Angevin Empire. Though regarded as a model king during the four centuries after his death[8] and viewed as a pious hero by his subjects,[9] he was later perceived by historians as a ruler who treated the kingdom of England merely as a source of revenue for his armies rather than a land entrusted to his stewardship.[10] This "Little England" view of Richard has come under increasing scrutiny by modern historians, who view it as anachronistic.[8] Richard I is an enduring iconic figure both in England and in France.[11]

Early life and accession in Aquitaine

[edit]Childhood

[edit]

Richard was born on 8 September 1157,[12] probably at Beaumont Palace,[13] in Oxford, England, son of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine. He was the younger brother of William, Henry the Young King, and Matilda; William died before Richard's birth.[14] As a younger son of Henry II, Richard was not expected to ascend the throne.[15] Four more children were born to King Henry and Queen Eleanor: Geoffrey, Eleanor, Joan, and John. Richard also had two half-sisters from his mother's first marriage to Louis VII of France: Marie and Alix.[14]

Richard is often depicted as having been the favourite son of his mother.[16] His father was Angevin-Norman and great-grandson of William the Conqueror. Contemporary historian Ralph de Diceto traced his family's lineage through Matilda of Scotland to the Anglo-Saxon kings of England and Alfred the Great, and from there legend linked them to Noah and Woden. According to Angevin family tradition, there was even 'infernal blood' in their ancestry, with a claimed descent from the fairy, or female demon, Melusine.[13][17]

While his father visited his lands from Scotland to France, Richard probably spent his childhood in England. His first recorded visit to the European continent was in May 1165, when his mother took him to Normandy. His wet nurse was Hodierna of St Albans, whom he gave a generous pension after he became king.[18] Little is known about Richard's education.[19] Although he was born in Oxford and brought up in England up to his eighth year, it is not known to what extent he used or understood English; he was an educated man who composed poetry and wrote in Limousin (lenga d'òc) and also in French.[20]

During his captivity, English prejudice against foreigners was used in a calculated way by his brother John to help destroy the authority of Richard's chancellor, William Longchamp, who was a Norman. One of the specific charges laid against Longchamp, by John's supporter Hugh Nonant, was that he could not speak English. This indicates that by the late 12th century a knowledge of English was expected of those in positions of authority in England.[21][22]

Richard was said to be very attractive; his hair was between red and blond, and he was light-eyed with a pale complexion. According to Clifford Brewer, he was 6 feet 5 inches (1.96 m),[23] although that is unverifiable since his remains have been lost since at least the French Revolution. John, his youngest brother, was known to be 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m).

The Itinerarium peregrinorum et gesta regis Ricardi, a Latin prose narrative of the Third Crusade, states that: "He was tall, of elegant build; the colour of his hair was between red and gold; his limbs were supple and straight. He had long arms suited to wielding a sword. His long legs matched the rest of his body".[24]

Marriage alliances were common among medieval royalty: they led to political alliances and peace treaties and allowed families to stake claims of succession on each other's lands. In March 1159, it was arranged that Richard would marry one of the daughters of Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona; however, these arrangements failed, and the marriage never took place. Henry the Young King was married to Margaret, daughter of Louis VII of France, on 2 November 1160.[25] Despite this alliance between the Plantagenets and the Capetians, the dynasty on the French throne, the two houses were sometimes in conflict. In 1168, the intercession of Pope Alexander III was necessary to secure a truce between them. Henry II had conquered Brittany and taken control of Gisors and the Vexin, which had been part of Margaret's dowry.[26]

Early in the 1160s there had been suggestions Richard should marry Alys, Countess of the Vexin, fourth daughter of Louis VII; because of the rivalry between the kings of England and France, Louis obstructed the marriage. A peace treaty was secured in January 1169 and Richard's betrothal to Alys was confirmed.[27] Henry II planned to divide his and Eleanor's territories among their three eldest surviving sons: Henry would become King of England and have control of Anjou, Maine, and Normandy; Richard would inherit Aquitaine and Poitiers from his mother; and Geoffrey would become Duke of Brittany through marriage with Constance, heir presumptive of Conan IV. At the ceremony where Richard's betrothal was confirmed, he paid homage to the king of France for Aquitaine, thus securing ties of vassalage between the two.[28]

After Henry II fell seriously ill in 1170, he enacted his plan to divide his territories, although he would retain overall authority over his sons and their territories. His son Henry was crowned as heir apparent in June 1170, and in 1171 Richard left for Aquitaine with his mother, and Henry II gave him the duchy of Aquitaine at the request of Eleanor. Richard and his mother embarked on a tour of Aquitaine in 1171 in an attempt to pacify the locals.[29] Together, they laid the foundation stone of St Augustine's Monastery in Limoges. In June 1172, at age 14, Richard was formally recognised as duke of Aquitaine and count of Poitou when he was granted the lance and banner emblems of his office; the ceremony took place in Poitiers and was repeated in Limoges, where he wore the ring of St Valerie, who was the personification of Aquitaine.[30][31]

Revolt against Henry II

[edit]According to Ralph of Coggeshall, Henry the Young King instigated a rebellion against Henry II; he wanted to reign independently over at least part of the territory his father had promised him, and to break away from his dependence on Henry II, who controlled the purse strings.[32] There were rumors that Eleanor might have encouraged her sons to revolt against their father.[33]

Henry the Young King abandoned his father and left for the French court, seeking the protection of Louis VII; his brothers Richard and Geoffrey soon followed him, while the five-year-old John remained in England. Louis gave his support to the three brothers and even knighted Richard, tying them together through vassalage.[34] Jordan Fantosme, a contemporary poet, described the rebellion as a "war without love".[35]

The brothers made an oath at the French court that they would not make terms with Henry II without the consent of Louis VII and the French barons.[37] With the support of Louis, Henry the Young King attracted many barons to his cause through promises of land and money; one such baron was Philip I, Count of Flanders, who was promised £1,000 and several castles. The brothers also had supporters ready to rise up in England. Robert de Beaumont, 3rd Earl of Leicester, joined forces with Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk, Hugh de Kevelioc, 5th Earl of Chester, and William I of Scotland for a rebellion in Suffolk. The alliance with Louis was initially successful, and by July 1173 the rebels were besieging Aumale, Neuf-Marché, and Verneuil, and Hugh de Kevelioc had captured Dol in Brittany.[38] Richard went to Poitou and raised the barons who were loyal to himself and his mother in rebellion against his father. Eleanor was captured, so Richard was left to lead his campaign against Henry II's supporters in Aquitaine on his own. He marched to take La Rochelle but was rejected by the inhabitants; he withdrew to the city of Saintes, which he established as a base of operations.[39][40]

In the meantime, Henry II had raised a very expensive army of more than 20,000 mercenaries with which to face the rebellion.[38] He marched on Verneuil, and Louis retreated from his forces. The army proceeded to recapture Dol and subdued Brittany. At this point Henry II made an offer of peace to his sons; on the advice of Louis the offer was refused.[41] Henry II's forces took Saintes by surprise and captured much of its garrison, although Richard was able to escape with a small group of soldiers. He took refuge in Château de Taillebourg for the rest of the war.[39] Henry the Young King and the Count of Flanders planned to land in England to assist the rebellion led by the Earl of Leicester. Anticipating this, Henry II returned to England with 500 soldiers and his prisoners (including Eleanor and his sons' wives and fiancées),[42] but on his arrival found out that the rebellion had already collapsed. William I of Scotland and Hugh Bigod were captured on 13 and 25 July respectively. Henry II returned to France and raised the siege of Rouen, where Louis VII had been joined by Henry the Young King after abandoning his plan to invade England. Louis was defeated and a peace treaty was signed in September 1174,[41] the Treaty of Montlouis.[43]

When Henry II and Louis VII made a truce on 8 September 1174, its terms specifically excluded Richard.[42][44] Abandoned by Louis and wary of facing his father's army in battle, Richard went to Henry II's court at Poitiers on 23 September and begged for forgiveness, weeping and falling at the feet of Henry, who gave Richard the kiss of peace.[42][44] Several days later, Richard's brothers joined him in seeking reconciliation with their father.[42] The terms the three brothers accepted were less generous than those they had been offered earlier in the conflict (when Richard was offered four castles in Aquitaine and half of the income from the duchy):[37] Richard was given control of two castles in Poitou and half the income of Aquitaine; Henry the Young King was given two castles in Normandy; and Geoffrey was permitted half of Brittany. Eleanor remained Henry II's prisoner until his death, partly as insurance for Richard's good behaviour.[45]

Final years of Henry II's reign

[edit]

After the conclusion of the war, the process of pacifying the provinces that had rebelled against Henry II began. The King travelled to Anjou for this purpose, and Geoffrey dealt with Brittany. In January 1175 Richard was dispatched to Aquitaine to punish the barons who had fought for him. The historian John Gillingham notes that the chronicle of Roger of Howden is the main source for Richard's activities in this period. According to the chronicle, most of the castles belonging to rebels were to be returned to the state they were in 15 days before the outbreak of war, while others were to be razed.[46] Given that by this time it was common for castles to be built in stone, and that many barons had expanded or refortified their castles, this was not an easy task.[47] Roger of Howden records the two-month siege of Castillon-sur-Agen; while the castle was "notoriously strong", Richard's siege engines battered the defenders into submission.[48]

On this campaign, Richard acquired the name "the Lion" or "the Lionheart" due to his noble, brave and fierce leadership.[49][47] He is referred to as "this our lion" (hic leo noster) as early as 1187 in the Topographia Hibernica of Giraldus Cambrensis,[50] while the byname "lionheart" (le quor de lion) is first recorded in Ambroise's L'Estoire de la Guerre Sainte in the context of the Accon campaign of 1191.[51]

Henry seemed unwilling to entrust any of his sons with resources that could be used against him. It was suspected that he had appropriated Alys of France, Richard's betrothed, as his mistress. This made a marriage between Richard and Alys technically impossible in the eyes of the Church, but Henry prevaricated: he regarded Alys's dowry, Vexin in the Île-de-France, as valuable. Richard was discouraged from renouncing Alys because she was the sister of King Philip II of France, a close ally.[52][53]

After his failure to overthrow his father, Richard concentrated on putting down internal revolts by the nobles of Aquitaine, especially in the territory of Gascony. The increasing cruelty of his rule led to a major revolt there in 1179. Hoping to dethrone Richard, the rebels sought the help of his brothers Henry and Geoffrey. The turning point came in the Charente Valley in the spring of 1179. The well-defended fortress of Taillebourg seemed impregnable. The castle was surrounded by a cliff on three sides and a town on the fourth side with a three-layer wall. Richard first destroyed and looted the farms and lands surrounding the fortress, leaving its defenders no reinforcements or lines of retreat. The garrison sallied out of the castle and attacked Richard; he was able to subdue the army and then followed the defenders inside the open gates, where he easily took over the castle in two days. Richard's victory at Taillebourg deterred many barons from thinking of rebelling and forced them to declare their loyalty to him. In 1181–82, Richard faced a revolt over the succession to the county of Angoulême. His opponents turned to Philip II of France for support, and the fighting spread through the Limousin and Périgord. The excessive cruelty of Richard's punitive campaigns aroused even more hostility.[54]

After Richard had subdued his rebellious barons, he again challenged his father. From 1180 to 1183 the tension between father and son grew, as Henry II commanded Richard to pay homage to Henry the Young King, but Richard refused. Finally, in 1183, the younger Henry and Geoffrey of Brittany invaded Aquitaine in an attempt to subdue Richard. Richard's barons joined in the fray and turned against their duke. However, Richard and his army succeeded in holding back the invading armies, and they executed any prisoners. The conflict paused briefly in June 1183, when the Young King died. With the death of his elder brother, Richard became the eldest surviving son and therefore heir to the English crown. Henry II demanded that Richard give up Aquitaine (which he planned to give to his youngest son, John, as his inheritance). Richard refused, and conflict continued between him and his father. Finally, the King brought Queen Eleanor out of prison, sent her to Aquitaine, and demanded that Richard return possession of his lands to his mother.[55] Meanwhile, in 1186, Geoffrey died in a tournament. He had a daughter, Eleanor, and a posthumous son, Arthur.[56]

In 1187, to strengthen his position, Richard allied himself with 22-year-old Philip II, the son of Eleanor's ex-husband Louis VII by Adela of Champagne. Roger of Howden wrote:

The King of England was struck with great astonishment, and wondered what [this alliance] could mean, and, taking precautions for the future, frequently sent messengers into France for the purpose of recalling his son Richard; who, pretending that he was peaceably inclined and ready to come to his father, made his way to Chinon, and, in spite of the person who had the custody thereof, carried off the greater part of his father's treasures, and fortified his castles in Poitou with the same, refusing to go to his father.[57]

Overall, Howden is chiefly concerned with the politics of the relationship between Richard and Philip. Gillingham has addressed theories suggesting that this political relationship was also sexually intimate, which he posits probably stemmed from an official record announcing that, as a symbol of unity between the two countries, the kings of England and France had slept overnight in the same bed. Gillingham has characterized this as "an accepted political act, nothing sexual about it;... a bit like a modern-day photo opportunity".[58]

With news arriving of the Battle of Hattin, he took the cross at Tours in the company of other French nobles. In exchange for Philip's help against his father, Richard paid homage to Philip in November 1188. On 4 July 1189, the forces of Richard and Philip defeated Henry's army at Ballans. Henry agreed to name Richard his heir apparent. Two days later Henry died in Chinon, and Richard succeeded him as King of England, Duke of Normandy, and Count of Anjou. Roger of Howden claimed that Henry's corpse bled from the nose in Richard's presence, which was assumed to be a sign that Richard had caused his death.[citation needed]

King and crusader

[edit]Coronation and anti-Jewish violence

[edit]

Richard I was officially invested as Duke of Normandy on 20 July 1189 and crowned king in Westminster Abbey on 3 September 1189.[59] Tradition barred all Jews and women from the investiture, but some Jewish leaders arrived to present gifts for the new king.[60] According to Ralph of Diceto, Richard's courtiers stripped and flogged the Jews, then flung them out of court.[61]

When a rumour spread that Richard had ordered all Jews to be killed, the people of London attacked the Jewish population.[61] Many Jewish homes were destroyed by arsonists, and several Jews were forcibly converted.[61] Some sought sanctuary in the Tower of London, and others managed to escape. Among those killed was Jacob of Orléans, a respected Jewish scholar.[62] Roger of Howden, in his Gesta Regis Ricardi, claimed that the jealous and bigoted citizens started the rioting, and that Richard punished the perpetrators, allowing a forcibly converted Jew to return to his native religion. Baldwin of Forde, Archbishop of Canterbury, reacted by remarking, "If the King is not God's man, he had better be the devil's".[63]

Offended that he was not being obeyed, and aware that the attacks could destabilise his realm on the eve of his departure on crusade, Richard ordered the execution of those responsible for the most heinous murders and persecutions, including rioters who had accidentally burned down Christian homes.[64] He distributed a royal writ demanding that the Jews be left alone. The edict was only loosely enforced, however, and the following March further violence occurred, including a massacre at York.[65]

Crusade plans

[edit]Richard had already taken the cross as Count of Poitou in 1187. His father and Philip II had done so at Gisors on 21 January 1188 after receiving news of the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin. After Richard became king, he and Philip agreed to go on the Third Crusade, since each feared that during his absence the other might usurp his territories.[66]

Richard swore an oath to renounce his past wickedness in order to show himself worthy to take the cross. He started to raise and equip a new crusader army. He spent most of his father's treasury (filled with money raised by the Saladin tithe), raised taxes, and even agreed to free King William I of Scotland from his oath of subservience to Richard in exchange for 10,000 marks (£6,500). To raise still more revenue he sold the right to hold official positions, lands, and other privileges to those interested in them.[67] Those already appointed were forced to pay huge sums to retain their posts. William Longchamp, Bishop of Ely and the King's chancellor, made a show of bidding £3,000 to remain as Chancellor. He was apparently outbid by a certain Reginald the Italian, but that bid was refused.[citation needed]

Richard made some final arrangements on the continent.[68] He reconfirmed his father's appointment of William Fitz Ralph to the important post of seneschal of Normandy. In Anjou, Stephen of Tours was replaced as seneschal and temporarily imprisoned for fiscal mismanagement. Payn de Rochefort, an Angevin knight, became seneschal of Anjou. In Poitou the ex-provost of Benon, Peter Bertin, was made seneschal, and finally, the household official Helie de La Celle was picked for the seneschalship in Gascony. After repositioning the part of his army he left behind to guard his French possessions, Richard finally set out on the crusade in summer 1190.[68] (His delay was criticised by troubadours such as Bertran de Born.) He appointed as regents Hugh de Puiset, Bishop of Durham, and William de Mandeville, 3rd Earl of Essex – who soon died and was replaced by William Longchamp.[69] Richard's brother John was not satisfied by this decision and started scheming against William Longchamp. When Richard was raising funds for his crusade, he was said to have declared, "I would have sold London if I could find a buyer".[70]

Occupation of Sicily

[edit]

In September 1190 Richard and Philip arrived in Sicily.[71] After the death of King William II of Sicily in 1189 his cousin Tancred had seized power, although the legal heir was William's aunt Constance. Tancred had imprisoned William's widow, Queen Joan, who was Richard's sister, and did not give her the money she had inherited in William's will. When Richard arrived he demanded that his sister be released and given her inheritance; she was freed on 28 September, but without the inheritance.[72] The presence of foreign troops also caused unrest: in October, the people of Messina revolted, demanding that the foreigners leave.[73] Richard attacked Messina, capturing it on 4 October 1190.[73] After looting and burning the city Richard established his base there, but this created tension between Richard and Philip. He remained there until Tancred finally agreed to sign a treaty on 4 March 1191. The treaty was signed by Richard, Philip, and Tancred.[74] Its main terms were:

- Joan was to receive 20,000 ounces (570 kg) of gold as compensation for her inheritance, which Tancred kept.

- Richard officially proclaimed his nephew, Duke Arthur I of Brittany, as his heir, and Tancred promised to marry one of his daughters to Arthur when he came of age, giving a further 20,000 ounces (570 kg) of gold that would be returned by Richard if Arthur did not marry Tancred's daughter.

The two kings stayed in Sicily for a while, but this resulted in increasing tensions between them and their men, with Philip plotting with Tancred against Richard.[75] The two kings eventually met to clear the air and reached an agreement, including the end of Richard's betrothal to Philip's sister Alys.[76] In 1190 King Richard, before leaving for the Holy Land for the crusade, met Joachim of Fiore, who spoke to him of a prophecy contained in the Book of Revelation.

Conquest of Cyprus

[edit]

In April 1191, Richard left Messina for Acre with an army of 17,000 men,[77] but a storm dispersed his large fleet.[78] After some searching, it was discovered that the ship carrying his sister Joan and his new fiancée, Berengaria of Navarre, was anchored on the south coast of Cyprus, along with the wrecks of several other vessels, including the treasure ship. Survivors of the wrecks had been taken prisoner by the island's ruler, Isaac Komnenos.[79]

On 1 May 1191, Richard's fleet arrived in the port of Lemesos on Cyprus.[79] He ordered Isaac to release the prisoners and treasure.[79] Isaac refused, so Richard landed his troops and took Lemesos.[80] Various princes of the Holy Land arrived in Lemesos at the same time, in particular Guy of Lusignan. All declared their support for Richard provided that he support Guy against his rival, Conrad of Montferrat.[81]

The local magnates abandoned Isaac, who considered making peace with Richard, joining him on the crusade, and offering his daughter in marriage to the person named by Richard.[82] Isaac changed his mind, however, and tried to escape. Richard's troops, led by Guy de Lusignan, conquered the whole island by 1 June. Isaac surrendered and was confined with silver chains because Richard had promised that he would not place him in irons. Richard named Richard de Camville and Robert of Thornham as governors. He later sold the island to the master of Knights Templar, Robert de Sablé, and it was subsequently acquired, in 1192, by Guy of Lusignan and became a stable feudal kingdom.[83]

The rapid conquest of the island by Richard was of strategic importance. The island occupies a key strategic position on the maritime lanes to the Holy Land, whose occupation by the Christians could not continue without support from the sea.[83] Cyprus remained a Christian stronghold until the Ottoman invasion in 1570.[84] Richard's exploit was well publicised and contributed to his reputation, and he also derived significant financial gains from the conquest of the island.[84] Richard left Cyprus for Acre on 5 June with his allies.[84]

Marriage

[edit]Before leaving Cyprus on crusade, Richard married Berengaria, the first-born daughter of King Sancho VI of Navarre. Richard had first grown close to her at a tournament held in her native Navarre.[85] The wedding was held in Lemesos on 12 May 1191 at the Chapel of St George and was attended by Richard's sister Joan, whom he had brought from Sicily. The marriage was celebrated with great pomp and splendour, many feasts and entertainments, and public parades and celebrations followed, commemorating the event. When Richard married Berengaria he was still officially betrothed to Alys, and he pushed for the match in order to obtain the Kingdom of Navarre as a fief, as Aquitaine had been for his father. Further, Eleanor championed the match, as Navarre bordered Aquitaine, thereby securing the southern border of her ancestral lands. Richard took his new wife on crusade with him briefly, though they returned separately. Berengaria had almost as much difficulty in making the journey home as her husband did, and she did not see England until after his death. After his release from German captivity, Richard showed some regret for his earlier conduct, but he was not reunited with his wife.[86] The marriage remained childless.[citation needed]

In the Holy Land

[edit]

Richard landed at Acre on 8 June 1191.[87] He gave his support to his Poitevin vassal Guy of Lusignan, who had brought troops to help him in Cyprus. Guy was the widower of his father's cousin Sibylla of Jerusalem and was trying to retain the kingship of Jerusalem, despite his wife's death during the Siege of Acre the previous year.[88] Guy's claim was challenged by Conrad of Montferrat, second husband of Sibylla's half-sister, Isabella: Conrad, whose defence of Tyre had saved the kingdom in 1187, was supported by Philip of France, son of his first cousin Louis VII of France, and by another cousin, Leopold V, Duke of Austria.[89] Richard also allied with Humphrey IV of Toron, Isabella's first husband, from whom she had been forcibly divorced in 1190. Humphrey was loyal to Guy and spoke Arabic fluently, so Richard used him as a translator and negotiator.[90]

Richard and his forces aided in the capture of Acre, despite Richard's serious illness. At one point, while sick from arnaldia, a disease similar to scurvy, he picked off guards on the walls with a crossbow, while being carried on a stretcher covered "in a great silken quilt".[91][92] Eventually, Conrad of Montferrat concluded the surrender negotiations with Saladin's forces inside Acre and raised the banners of the kings in the city. Richard quarrelled with Leopold over the deposition of Isaac Komnenos (related to Leopold's Byzantine mother) and his position within the crusade. Leopold's banner had been raised alongside the English and French standards. This was interpreted as arrogance by both Richard and Philip, as Leopold was a vassal of the Holy Roman Emperor (although he was the highest-ranking surviving leader of the imperial forces). Richard's men tore the flag down and threw it in the moat of Acre.[93][94] Leopold left the crusade immediately. Philip also left soon afterwards, in poor health and after further disputes with Richard over the status of Cyprus (Philip demanded half the island) and the kingship of Jerusalem.[95]

Richard had kept approximately 2,700 Muslim prisoners as hostages against Saladin fulfilling all the terms of the surrender of the lands around Acre.[96] Philip, before leaving, had entrusted his prisoners to Conrad, but Richard forced him to hand them over to him. Richard feared his forces being bottled up in Acre, and believed that his troops could not advance with the prisoners in train. He therefore ordered all the prisoners to be executed. He then moved south, defeating Saladin's forces at the Battle of Arsuf, 30 miles (50 km) north of Jaffa, on 7 September 1191. Saladin attempted to harass Richard's army into breaking its formation in order to defeat it in detail. Richard maintained his army's defensive formation, however, until the Hospitallers broke ranks to charge the right wing of Saladin's forces. Richard then ordered a general counterattack, which won the battle. Arsuf was an important victory. The Muslim army was not destroyed, despite the considerable casualties it suffered, but it did rout; this was considered shameful by the Muslims and boosted the morale of the Crusaders. In November 1191, following the fall of Jaffa, the Crusader army advanced inland towards Jerusalem. The army then marched to Beit Nuba, only 12 miles (19 km) from Jerusalem. Muslim morale in Jerusalem was so low that the arrival of the Crusaders would probably have caused the city to fall quickly. However, the weather was appallingly bad, cold with heavy rain and hailstorms; this, combined with the fear that the Crusader army, if it besieged Jerusalem, might be trapped by a relieving force, led to the decision to retreat back to the coast.[97] Richard attempted to negotiate with Saladin, but this was unsuccessful. In the first half of 1192, he and his troops refortified Ascalon, having earlier taken the fortified town of Darum.[98]

An election forced Richard to accept Conrad of Montferrat as King of Jerusalem, and he sold Cyprus to his defeated protégé, Guy. Only days later, on 28 April 1192, Conrad was stabbed to death by the Assassins[99] before he could be crowned. Eight days later Richard's own nephew Henry II of Champagne was married to the widowed Isabella, although she was carrying Conrad's child. The murder was never conclusively solved, and Richard's contemporaries widely suspected his involvement.[100]

The crusader army made another advance on Jerusalem, and, in June 1192, it came within sight of the city before being forced to retreat once again, this time because of dissension amongst its leaders. In particular, Richard and the majority of the army council wanted to force Saladin to relinquish Jerusalem by attacking the basis of his power through an invasion of Egypt. The leader of the French contingent, Hugh III, Duke of Burgundy, however, was adamant that a direct attack on Jerusalem should be made. This split the Crusader army into two factions, and neither was strong enough to achieve its objective. Richard stated that he would accompany any attack on Jerusalem but only as a simple soldier; he refused to lead the army. Without a united command the army had little choice but to retreat back to the coast.[101]

A period of minor skirmishes with Saladin's forces commenced, punctuated by another defeat in the field for the Ayyubid army at the Battle of Jaffa. Baha' al-Din, a contemporary Muslim soldier and biographer of Saladin, recorded a tribute to Richard's martial prowess at this battle: "I have been assured ... that on that day the king of England, lance in hand, rode along the whole length of our army from right to left, and not one of our soldiers left the ranks to attack him. The Sultan was wroth thereat and left the battlefield in anger...".[102] Both sides realised that their respective positions were growing untenable. Richard knew that both Philip and his own brother John were starting to plot against him, and the morale of Saladin's army had been badly eroded by repeated defeats. However, Saladin insisted on the razing of Ascalon's fortifications, which Richard's men had rebuilt, and a few other points. Richard made one last attempt to strengthen his bargaining position by attempting to invade Egypt – Saladin's chief supply-base – but failed. In the end, time ran out for Richard. He realised that his return could be postponed no longer, since both Philip and John were taking advantage of his absence. He and Saladin finally came to a settlement on 2 September 1192. The terms provided for the destruction of Ascalon's fortifications, allowed Christian pilgrims and merchants access to Jerusalem, and initiated a three-year truce.[103] Richard, being ill with arnaldia, left for England on 9 October 1192.[104]

Life after the Third Crusade

[edit]Captivity, ransom and return

[edit]

Bad weather forced Richard's ship to put in at Corfu, in the lands of Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelos, who objected to Richard's annexation of Cyprus, formerly Byzantine territory. Disguised as a Knight Templar, Richard sailed from Corfu with four attendants, but his ship was wrecked near Aquileia, forcing Richard and his party into taking a dangerous land route through central Europe. On his way to the territory of his brother-in-law Henry the Lion, Richard was captured shortly before Christmas 1192 near Vienna by Leopold of Austria, who accused Richard of arranging the murder of his cousin Conrad of Montferrat. Moreover, Richard had personally offended Leopold by casting down his standard from the walls of Acre.[94]

Leopold kept Richard prisoner at Dürnstein Castle under the care of Leopold's ministerialis Hadmar of Kuenring.[105] This mishap was soon known in England, but the regents were for some weeks uncertain of his whereabouts. While in prison, Richard wrote the musical piece Ja nus hons pris or Ja nuls om pres ("No man who is imprisoned"), which is addressed to his half-sister Marie. He wrote the song, in French and Occitan versions, to express his feelings of abandonment by his people and his sister. The detention of a crusader was contrary to public law,[106][107] and on these grounds Pope Celestine III excommunicated Leopold.[108]

On 28 March 1193, Richard was brought to Speyer and handed over to Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI, who imprisoned him in Trifels Castle. The Emperor was aggrieved by the support the Plantagenets had given to the family of Henry the Lion and by Richard's recognition of Tancred in Sicily.[106] Henry VI needed money to raise an army and assert his rights over southern Italy and continued to hold Richard for ransom. Nevertheless, to Richard's irritation, Pope Celestine hesitated to excommunicate Henry VI, as he had Duke Leopold, for the continued wrongful imprisonment of Richard. He famously refused to show deference to the Emperor and declared to him, "I am born of a rank which recognises no superior but God".[109] The King was at first shown a certain measure of respect, but later, at the prompting of Philip of Dreux, Bishop of Beauvais and Philip of France's cousin, the conditions of Richard's captivity worsened, and he was kept in chains, "so heavy," Richard declared, "that a horse or ass would have struggled to move under them."[110]

The Emperor demanded that 150,000 marks (100,000 pounds of silver) be delivered to him before he would release the King, the same amount raised by the Saladin tithe only a few years earlier,[111] and two to three times the annual income of the English Crown under Richard. Meanwhile, Eleanor worked tirelessly to raise the ransom for her son's release. Leopold also requested Eleanor, Fair Maid of Brittany, niece of Richard, marry his heir Frederick. Both clergy and laymen were taxed for a quarter of the value of their property, the gold and silver treasures of the churches were confiscated, and money was raised from the scutage and the carucage taxes. At the same time, Richard's brother John and King Philip of France offered 80,000 marks for Henry VI to hold Richard prisoner until Michaelmas 1194. Henry turned down the offer. The money to release the King was transferred to Germany by the Emperor's ambassadors, but "at the king's peril" (had it been lost along the way, Richard would have been held responsible), and finally, on 4 February 1194, Richard was released. Philip sent a message to John: "Look to yourself; the devil is loose".[112] Furthermore, upon the sudden death of Leopold, under the pressure of the Pope, the new duke Frederick was forced to abandon his marriage plan with Eleanor of Brittany.[113][114]

War against Philip of France

[edit]In Richard's absence, his brother John revolted with the aid of Philip; amongst Philip's conquests in the period of Richard's imprisonment was a part of Normandy[115] called Norman Vexin facing French Vexin. Richard forgave John when they met again and named him as his heir in place of their nephew Arthur. At Winchester, on 11 March 1194, Richard was crowned a second time to nullify the shame of his captivity.[116]

Richard began his reconquest of the lost lands in Normandy. The fall of the Château de Gisors to the French in 1193 opened a gap in the Norman defences. The search began for a fresh site for a new castle to defend the duchy of Normandy and act as a base from which Richard could launch his campaign to take back Vexin from French control.[117] A naturally defensible position was identified, perched high above the River Seine, an important transport route, in the manor of Andeli. Under the terms of the Treaty of Louviers (December 1195) between Richard and Philip II, neither king was allowed to fortify the site; despite this, Richard intended to build the vast Château Gaillard.[118] Richard tried to obtain the manor through negotiation. Walter de Coutances, Archbishop of Rouen, was reluctant to sell the manor, as it was one of the diocese's most profitable, and other lands belonging to the diocese had recently been damaged by war.[118] When Philip besieged Aumale in Normandy, Richard grew tired of waiting and seized the manor,[118][119] although the act was opposed by the Catholic Church.[120] The archbishop issued an interdict against performing church services in the duchy of Normandy; Roger of Howden detailed "unburied bodies of the dead lying in the streets and square of the cities of Normandy". The interdict was still in force when work began on the castle, but Pope Celestine III repealed it in April 1197 after Richard made gifts of land to the archbishop and the diocese of Rouen, including two manors and the prosperous port of Dieppe.[121][122]

Royal expenditure on castles declined from the levels spent under Henry II, attributed to a concentration of resources on Richard's war with the king of France.[123] However, the work at Château Gaillard was some of the most expensive of its time and cost an estimated £15,000 to £20,000 between 1196 and 1198.[124] This was more than double Richard's spending on castles in England, an estimated £7,000.[125] Unprecedented in its speed of construction, the castle was mostly complete in two years, when most construction on such a scale would have taken the better part of a decade.[124] According to William of Newburgh, in May 1198 Richard and the labourers working on the castle were drenched in a "rain of blood". While some of his advisers thought the rain was an evil omen, Richard was undeterred.[126] As no master-mason is mentioned in the otherwise detailed records of the castle's construction, military historian Richard Allen Brown has suggested that Richard himself was the overall architect; this is supported by the interest Richard showed in the work through his frequent presence.[127] In his final years, the castle became Richard's favourite residence, and writs and charters were written at Château Gaillard bearing "apud Bellum Castrum de Rupe" (at the Fair Castle of the Rock).[128]

Château Gaillard was ahead of its time, featuring innovations that would be adopted in castle architecture nearly a century later. Allen Brown described Château Gaillard as "one of the finest castles in Europe",[128] and military historian Sir Charles Oman wrote that it was considered "the masterpiece of its time. The reputation of its builder, Cœur de Lion, as a great military engineer might stand firm on this single structure. He was no mere copyist of the models he had seen in the East, but introduced many original details of his own invention into the stronghold".[129]

Determined to resist Philip's designs on contested Angevin lands such as the Vexin and Berry, Richard poured all his military expertise and vast resources into the war on the French King. He organised an alliance against Philip, including Baldwin IX of Flanders, Renaud, Count of Boulogne, and his father-in-law, King Sancho VI of Navarre, who raided Philip's lands from the south. Most importantly, he managed to secure the Welf inheritance in Saxony for his nephew, Henry the Lion's son, who was elected Otto IV of Germany in 1198.[citation needed]

Partly as a result of these and other intrigues, Richard won several victories over Philip. At Fréteval in 1194, just after Richard's return to France from captivity and money-raising in England, Philip fled, leaving his entire archive of financial audits and documents to be captured by Richard. At the Battle of Gisors (sometimes called Courcelles) in 1198, Richard took Dieu et mon Droit – "God and my Right" – as his motto (still used by the British monarchy today), echoing his earlier boast to Emperor Henry that his rank acknowledged no superior but God.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]

In March 1199, Richard was in Limousin suppressing a revolt by Viscount Aimar V of Limoges. Although it was Lent, he "devastated the Viscount's land with fire and sword".[131] He besieged the tiny, virtually unarmed castle of Châlus-Chabrol. Some chroniclers claimed that this was because a local peasant had uncovered a treasure trove of Roman gold.[132]

On 26 March 1199, Richard was hit in the shoulder by a crossbow bolt, and the wound turned gangrenous.[133] Richard asked to have the crossbowman brought before him; called alternatively Pierre (or Peter) Basile, John Sabroz, Dudo,[134][135] and Bertrand de Gourdon (from the town of Gourdon) by chroniclers, the man turned out (according to some sources, but not all) to be a boy. He said Richard had killed his father and two brothers, and that he had intended to kill Richard in revenge. He expected to be executed, but as a final act of mercy Richard forgave him, saying "Live on, and by my bounty behold the light of day", before he ordered the boy to be freed and sent away with 100 shillings.[c]

Richard died on 6 April 1199 in the arms of his mother, and thus "ended his earthly day."[137] Because of the nature of his death, it was later said that "the Lion by the Ant was slain".[138] According to one chronicler, Richard's last act of chivalry proved fruitless when the infamous mercenary captain Mercadier had the boy flayed alive and hanged as soon as Richard died.[139]

Richard's heart was buried at Rouen in Normandy, his entrails in Châlus (where he died), and the rest of his body at the feet of his father at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou.[140] In 2012, scientists analysed the remains of Richard's heart and found that it had been embalmed with various substances, including frankincense, a symbolically important substance because it had been present both at the birth and embalming of Christ.[141]

Henry Sandford, Bishop of Rochester (1226–1235), announced that he had seen a vision of Richard ascending to Heaven in March 1232 (along with Stephen Langton, the former archbishop of Canterbury), the King having presumably spent 33 years in purgatory as expiation for his sins.[142]

Richard produced no legitimate heirs and acknowledged only one illegitimate son, Philip of Cognac. He was succeeded by his brother John as king.[143] His French territories, with the exception of Rouen, initially rejected John as a successor, preferring his nephew Arthur.[144] The lack of any direct heirs from Richard was the first step in the dissolution of the Angevin Empire.[143]

Character

[edit]Contemporaries considered Richard as both a king and a knight famed for personal martial prowess; this was, apparently, the first such instance of this combination.[145] He was known as a valiant, competent military leader and individual fighter who was courageous and generous. At the same time, he was considered prone to the sins of lust, pride, greed and, above all, excessive cruelty. Ralph of Coggeshall, summarising Richard's career, deplores that the King was one of "the immense cohort of sinners".[146] He was criticised by clergy chroniclers for having taxed the clergy both for the Crusade and for his ransom, whereas the church and the clergy were usually exempt from taxes.[147]

Richard was a patron and a protector of the trouvères and troubadours of his entourage; he was also a poet himself.[8][148] He was interested in writing and music, and two poems are attributed to him. The first one is a sirventes in Old French, Dalfin je us voill desrenier, and the second one is a lament that he wrote during his imprisonment at Dürnstein Castle, Ja nus hons pris, with a version in Old Occitan and a version in Old French.[148][149]

Speculation regarding sexuality

[edit]In the historiography of the second half of the 20th century, much interest was shown in Richard's sexuality, in particular whether there was evidence of homosexuality. The topic had not been raised by Victorian or Edwardian historians, a fact denounced as a "conspiracy of silence" by John Harvey (1948).[150] The argument primarily drew on accounts of Richard's behaviour, as well as of his confessions and penitences, and of his childless marriage.[151] Richard did have at least one illegitimate child, Philip of Cognac, and there are reports on his sexual relations with local women during his campaigns.[152] Historians remain divided on the question of Richard's sexuality.[153] Harvey argued in favour of his homosexuality[154] but has been disputed by other historians, most notably John Gillingham (1994), who argues that Richard was probably heterosexual.[155] Flori (1999) again argued in favour of Richard's homosexuality, based on Richard's two public confessions and penitences (in 1191 and 1195) which, according to Flori, "must have" referred to the sin of sodomy.[156] But Flori concedes that contemporary accounts of Richard taking women by force exist,[157] concluding that he probably had sexual relations with both men and women.[158] Flori and Gillingham nevertheless agree that accounts of bed-sharing do not support the suggestion that Richard had a sexual relationship with King Philip II, as other modern authors had suggested.[159]

Legacy

[edit]Heraldry

[edit]

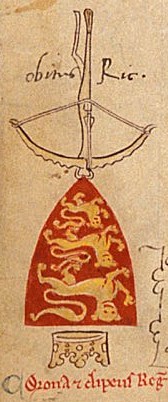

The second Great Seal of Richard I (1198) shows him bearing a shield depicting three lions passant-guardant. This is the first instance of the appearance of this blazon, which later became established as the Royal Arms of England. It is likely, therefore, that Richard introduced this heraldic design.[130] In his earlier Great Seal of 1189, he had used either one lion rampant or two lions rampants combatants, arms which he may have adopted from his father.[160]

Richard is also credited with having originated the English crest of a lion statant (now statant-guardant).[161] The coat of three lions continues to represent England on several coins of the pound sterling, forms the basis of several emblems of English national sports teams (such as the England national football team, and the team's "Three Lions" anthem),[162] and endures as one of the most recognisable national symbols of England.[163]

Medieval folklore

[edit]

Around the middle of the 13th century, various legends developed that, after Richard's capture, his minstrel Blondel travelled Europe from castle to castle, loudly singing a song known only to the two of them (they had composed it together).[164] Eventually, he came to the place where Richard was being held, and Richard heard the song and answered with the appropriate refrain, thus revealing where the King was incarcerated. The story was the basis of André Ernest Modeste Grétry's opera Richard Cœur-de-Lion and seems to be the inspiration for the opening to Richard Thorpe's film version of Ivanhoe. It seems unconnected to the real Jean 'Blondel' de Nesle, an aristocratic trouvère. It also does not correspond to the historical reality, since the King's jailers did not hide the fact; on the contrary, they publicised it.[165] An early account of this legend is to be found in Claude Fauchet's Recueil de l'origine de la langue et poesie françoise (1581).[166]

At some time around the 16th century, tales of Robin Hood started to mention him as a contemporary and supporter of King Richard the Lionheart, Robin being driven to outlawry, during the misrule of Richard's evil brother John, while Richard was away at the Third Crusade.[167]

Historical reputation and modern reception

[edit]

Richard's reputation over the years has "fluctuated wildly", according to historian John Gillingham.[168] According to Gillingham, "Richard's reputation, above all as a crusader, meant that the tone of contemporaries and near contemporaries, whether writing in the West or the Middle East, was overwhelmingly favourable."[8] Even historians attached to the court of his enemy Philip Augustus believed that if Richard had not fought against Philip then England would never have had a better king. A German contemporary, Walther von der Vogelweide, believed that Richard's generosity was what made his subjects willing to raise a king's ransom on his behalf. Richard's character was also praised by figures in Saladin's court such as Baha ad-Din and Ibn al-Athir, who judged him the most remarkable ruler of his time. Even in Scotland he won a high place in historical tradition.[8]

After Richard's death his image was further romanticized[169] and for at least four centuries Richard was considered a model king by historians such as Holinshed and John Speed.[8] However, in 1621 the Stuart courtier and poet and historian Samuel Daniel criticized Richard for wasting English resources on the crusade and wars in France. This "remarkably original and consciously anachronistic interpretation" eventually became the common opinion of scholars.[8] Though Richard's popular image tended to be dominated by the positive qualities of chivalry and military competence,[145] his reputation among historians was typified by Steven Runciman's verdict: "he was a bad son, a bad husband, and a bad king, but a gallant and splendid soldier" ("History of the Crusades" Vol. III).

Victorian England was divided on Richard: many admired him as a crusader and man of God, erecting an heroic statue to him outside the Houses of Parliament. The late-Victorian scholar William Stubbs, however, thought him "a bad son, a bad husband, a selfish ruler, and a vicious man". During his ten years' reign, Richard was in England for no more than six months, and totally absent for the last five years.[168] This led Stubbs to argue Richard harbored no sympathy "or even consideration, for his people" and that "his ambition was that of a mere warrior."[170]

However, since 1978 this approach has been increasingly questioned for its insularity. According to Gillingham, "it is now more widely acknowledged that Richard was head of a dynasty with far wider responsibilities than merely English ones, and that in judging a ruler's political acumen more weight might be attached to contemporary opinion than to views which occurred to no one until many centuries after his death."[8]

In World War I, when British troops commanded by General Edmund Allenby captured Jerusalem, the British press printed cartoons of Richard looking down from the heavens with the caption reading, "At last my dream has come true".[171] General Allenby protested against his campaign being presented as a latter-day Crusade, stating "The importance of Jerusalem lay in its strategic importance, there was no religious impulse in this campaign".[172]

Family tree

[edit]: Bold borders indicate legitimate children of English monarchs

| Baldwin II King of Jerusalem | Fulk IV Count of Anjou | Bertrade of Montfort | Philip I King of France | William the Conqueror King of England r. 1066–1087 | Saint Margaret of Scotland | Malcolm III King of Scotland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melisende Queen of Jerusalem | Fulk V King of Jerusalem | Eremburga of Maine | Robert Curthose | William II King of England r. 1087–1100 | Adela of Normandy | Henry I King of England r. 1100–1135 | Matilda of Scotland | Duncan II King of Scotland | Edgar King of Scotland | Alexander I King of Scotland | David I King of Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sibylla of Anjou | William Clito | Stephen King of England r. 1135–1154 | Geoffrey Plantagenet Count of Anjou | Empress Matilda | William Adelin | Matilda of Anjou | Henry of Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Margaret I | Philip of Alsace Count of Flanders | Louis VII King of France | Eleanor of Aquitaine | Henry II King of England r. 1154–1189 | Geoffrey Count of Nantes | William FitzEmpress | Malcolm IV King of Scotland | William the Lion King of Scotland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baldwin I Latin Emperor | Isabella of Hainault | Philip II King of France | Henry the Young King | Matilda Duchess of Saxony | Richard I King of England r. 1189–1199 | Geoffrey II Duke of Brittany | Eleanor | Alfonso VIII King of Castile | Joan | William II King of Sicily | John King of England r. 1199–1216 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis VIII King of France | Otto IV Holy Roman Emperor | Arthur I Duke of Brittany | Blanche of Castile Queen of France | Henry III King of England r. 1216–1272 | Richard of Cornwall King of the Romans | Joan Queen of Scotland | Alexander II King of Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Historians are divided in their use of the terms Plantagenet and Angevin in regard to Henry II and his children. Some class Henry II to be the first Plantagenet king of England; others refer to Henry II, Richard I, and John as the Angevin dynasty, and consider Henry III to be the first Plantagenet ruler.[1]

- ^ The troubadour Bertran de Born also called him Richard Oc-e-Non (Occitan for 'Yes and No'), possibly from a reputation for terseness.[5]

- ^ Although there are numerous variations of the story's details, it is not disputed that Richard did pardon the person who shot the bolt.[136]

References

[edit]- ^ Hamilton 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Saunders, Connie J. (2004). Writing War: Medieval Literary Responses to Warfare. D.S. Brewer. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8599-1843-5.

- ^ Trudgill, Peter (2021) European Language Matters: English in Its European Context, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781108832960 p. 61.

- ^ a b Turner & Heiser 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Gillingham, John (1978). Richard the Lionheart. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-8129-0802-2.

- ^ Addison 1842, pp. 141–149.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gillingham 2004

- ^ Turner & Heiser 2000[page needed]

- ^ Harvey 1948, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Harvey 1948, p. 58.

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 1.

- ^ a b Gillingham 2002, p. 24.

- ^ a b Flori 1999, p. ix.

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 2.

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 28.

- ^ Huscroft, Richard (2016). Tales From the Long Twelfth Century: The Rise and Fall of the Angevin Empire. Yale University Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-3001-8725-0.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, pp. 28, 32

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Leese 1996, p. 57

- ^ Prestwich & Prestwich 2004, p. 76

- ^ Stafford, Nelson & Martindale 2001, pp. 168–169

- ^ Brewer 2000, p. 41

- ^ McLynn, Frank (2012). Lionheart and Lackland: King Richard, King John and the Wars of Conquest. Random House. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7126-9417-9.

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 26–27

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 25, 28

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 27–28

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 40

- ^ Turner & Heiser 2000, p. 57

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 32.

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 41.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b Gillingham 2002, p. 48.

- ^ a b Flori 1999, p. 33.

- ^ a b Flori 1999, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 49.

- ^ a b Flori 1999, pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b c d Flori 1999, p. 35.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Gillingham 2002, p. 50.

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 52.

- ^ a b Flori 1999, p. 41

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 41–42.

- ^ "Richard the Lionheart Biography". www.medieval-life-and-times.info. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ Giraldi Cambrensis topographia Hibernica, dist. III, cap. L; ed. James F. Dimock in: Rolles Series (RS), Band 21, 5, London 1867, S. 196.

- ^ L'Estoire de la Guerre Sainte, v. 2310, ed. G. Paris in: Collection de documents inédits sur l'histoire de France, vol. 11, Paris 1897, col. 62.

- ^ Hilton, Lisa (2010). Queens Consort: England's Medieval Queens. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-0-2978-5749-5.[page needed]

- ^ Hilliam, David (2004). Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Richest Queen in Medieval Europe. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4042-0162-0.

- ^ "His reliance upon military force proved counterproductive. The more ruthless his punitive expeditions and the more rapacious his mercenaries' plundering, the more hostility he aroused. Even English chroniclers commented on the hatred aroused among Richard's Aquitanian subjects by his excessive cruelty"Turner & Heiser 2000, p. 264

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 94

- ^ Warren 1991, p. 37

- ^ Roger of Hoveden 1853, p. 64

- ^ Martin 2008.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 107

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c Flori 1999f, p. 95

- ^ Graetz & Bloch 1902[page needed]

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 465–466 As cited by Flori, the chronicler Giraud le Cambrien reports that Richard was fond of telling a tale according to which he was a descendant of a countess of Anjou who was, in fact, the fairy Melusine, concluding that his family "came from the devil and would return to the devil".

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Graetz & Bloch 1902, pp. 409–416

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 100.

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 97–101.

- ^ a b Flori 1999f, p. 101

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 99.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 118.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 111.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 114.

- ^ a b Flori 1999f, p. 116

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 117.

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Phillips, Jonathan (2014). The Crusades, 1095–1204 (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 170.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Flori 1999f, p. 132

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 134.

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 134–136.

- ^ a b Flori 1999f, p. 137

- ^ a b c Flori 1999f, p. 138

- ^ Abbott, Jacob (1877). History of King Richard the First of England (3rd ed.). Harper & Brothers. ASIN B00P179WN8.

- ^ Richard I. by Jacob Abbot, New York and London Harper & Brothers 1902

- ^ According to Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad on the 7th, but the Itinerarium and Gesta mention the 8th as the date of his arrival (L. Landon, The itinerary of King Richard I, with studies on certain matters of interest connected with his reign, London, 1935, p. 50

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 148

- ^ Gillingham 2002, pp. 148–149

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 149

- ^ Hosler, John D. (2018). Siege of Acre, 1189–1191: Saladin, Richard the Lionheart, and the Battle That Decided the Third Crusade. Yale University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-3002-3535-7. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon and Schuster. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-8498-3770-5. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Richard Coer de Lyon II vv. 6027–6028: Kyng R. let breke his baner, / And kest it into þe reuer.

- ^ a b Huffman, Joseph Patrick (2009). The Social Politics of Medieval Diplomacy: Anglo-German Relations (1066–1307). University of Michigan Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-472-02418-6.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 154.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, pp. 167–171.

- ^ Gillingham 1979, pp. 198–200.

- ^ Gillingham (1978), pp. 209–212

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie "Saladin" trans. Jean Marie Todd Harvard University Press 2011. p. 266 ISBN 978-0-6740-5559-9 "two members of the Assassin Sect, disguised as monks"

- ^ Wolff, Robert L., and Hazard, H. W. (1977). A History of the Crusades: Volume Two, The Later Crusades 1187–1311, The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 80.

- ^ Gillingham 1979, pp. 209–212.

- ^ Baha' al-Din Yusuf Ibn Shaddad (also rendered Beha al-Din and Beha Ed-Din), trans. C.W. Wilson (1897) Saladin Or What Befell Sultan Yusuf, Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society, London.[1], p. 376

- ^ Richard I. by Jacob Abbott, New York and London Harper & Brothers 1902

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie "Saladin" trans. Jean Marie Todd Harvard University Press 2011. pp. 267–269. ISBN 978-0-6740-5559-9

- ^ Arnold 1999, p. 128

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 295.

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Mann, Horace Kinder (1914). The Lives of the Popes in the Early Middle Ages. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-7222-2160-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Longford 1989, p. 85.

- ^ William of Newburgh, Historia, ii. 493–494, cited in John Gillingham, "The Kidnapped King: Richard I in Germany, 1192–1194," German Historical Institute London Bulletin, 2008. Richard would have his revenge on Dreux when the Bishop was captured, clad in a mailcoat and fully armed, by Richard's men in 1197; the king promptly clapped him into prison, from whence he was released only in 1200, a year after Richard's death.

- ^ Madden 2005, p. 96

- ^ Purser 2004, p. 161.

- ^ Costain, Thomas B. The Magnificent Century: The Pageant of England. Garden City: Doubleday, 1951, pp. 4–7

- ^ The Angevin Empire

- ^ Gillingham 2004.

- ^ Barrow 1967, p. 184.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, pp. 303–305.

- ^ a b c Gillingham 2002, p. 301.

- ^ Turner 1997, p. 10.

- ^ Packard 1922, p. 20.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, pp. 302–304

- ^ Brown 2004, p. 112.

- ^ Brown 1976, pp. 355–356.

- ^ a b McNeill 1992, p. 42.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 304.

- ^ Gillingham 2002, p. 303.

- ^ Brown 2004, p. 113.

- ^ a b Brown 1976, p. 62.

- ^ Oman 1991, p. 33.

- ^ a b Lewis, Suzanne (1987). The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora. California studies in the history of art. Vol. 21. University of California Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-5200-4981-9.

- ^ Ralph_of_Coggeshall, p. 94.

- ^ "King Richard I of England Versus King Philip II Augustus". Historynet.com. 23 August 2006. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ Gillingham 2004.

- ^ Gillingham 1989, p. 16.

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 233–254.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 234

- ^ Weir, Alison (2011). Eleanor of Aquitaine: By the Wrath of God, Queen of England. New York City: Random House. p. 319. ASIN B004OEIDOS.

- ^ Meade, Marion (1977). Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Biography. New York: Penguin Books. p. 329. ASIN B00328ZUOS.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 238.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 235.

- ^ Charlier, Philippe (28 February 2013). "The embalmed heart of Richard the Lionheart (1199 A.D.): a biological and anthropological analysis". Nature. 3 (1) 1296. Joël Poupon, Gaël-François Jeannel, Dominique Favier, Speranta-Maria Popescu, Raphaël Weil, Christophe Moulherat, Isabelle Huynh-Charlier, Caroline Dorion-Peyronnet, Ana-Maria Lazar, Christian Hervé & Geoffroy Lorin de la Grandmaison. London, England: Nature Research. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3.1296C. doi:10.1038/srep01296. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3584573. PMID 23448897.

- ^ Gillingham 1979, p. 8. Roger of Wendover (Flores historiarum, p. 234) ascribes Sandford's vision to the day before Palm Sunday, 3 April 1232.

- ^ a b Saccio, Peter; Black, Leon D. (2000). "John, The Legitimacy of the King; The Angevin Empire". Shakespeare's English Kings: History, Chronicle, and Drama (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 190–195. ISBN 0-19-512319-0.

- ^ Jones 2014, pp. 150–152

- ^ a b Flori 1999f, pp. 484–485

- ^ Among the sins for which the King of England was criticised, alongside lust, those of pride, greed, and cruelty loom large. Ralph of Coggeshall, describing his death in 1199, summarises in a few lines Richard's career and the vain hopes raised by his accession to the throne. Alas, he belonged to 'the immense cohort of sinners'" (Flori 1999, p. 335).

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 322.

- ^ a b "Richard I the Lionheart". Dictionary of music (in French). Larousse. 2005.

- ^ Gillingham 2002

- ^ Harvey, pp. 33–34. This question was mentioned, however, in Richard, A., Histoire des comtes de Poitout, 778–1204, vol. I–II, Paris, 1903, t. II, p. 130, cited in Flori 1999f, p. 448 (French).

- ^ Summarised in McLynn, pp. 92–93. Roger of Howden tells of a hermit who warned, "Be thou mindful of the destruction of Sodom, and abstain from what is unlawful", and Richard thus "receiving absolution, took back his wife, whom for a long time he had not known, and putting away all illicit intercourse, he remained constant to his wife and the two become one flesh". Roger of Hoveden, The Annals, trans. Henry T. Riley, 2. Vols. (London: H.G. Bohn, 1853; repr. New York: AMS Press, 1968)

- ^ McLynn, p. 93; see also Gillingham 1994, pp. 119–139.

- ^ Burgwinkle, William E. (2004). Sodomy, Masculinity and Law in Medieval Literature: France and England, 1050–1230. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0-5218-3968-6.

- ^ As cited in Flori 1999f, p. 448 (French). See for example Brundage, Richard Lion Heart, New York, 1974, pp. 38, 88, 202, 212, 257; Runciman, S., A History of the Crusades, Cambridge, 1951–194, t. III, pp. 41ff.; and Boswell, J., Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality, Chicago, 1980, pp. 231ff.

- ^ Gillingham 1994, pp. 119–139.

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 456–462.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 463.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 464.

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 454–456 (French). Contemporary accounts refer to various signs of friendship between the two when Richard was at Philip's court in 1187 during his rebellion against his father Henry II, including sleeping in the same bed. However, according to Flori and Gillingham, such signs of friendship were part of the customs of the time, indicating trust and confidence, and cannot be interpreted as proof of the homosexuality of either man.

- ^ Heraldry: An Introduction to a Noble Tradition. "Abrams Discoveries" series. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1997. p. 59. ISBN 978-0810928305.

- ^ Woodward and Burnett, Woodward's: A Treatise on Heraldry, British and foreign, With English and French Glossaries, p. 37. Ailes, Adrian (1982). The Origins of The Royal Arms of England. Reading: Graduate Center for Medieval Studies, University of Reading. pp. 52–63. Charles Boutell, A. C. Fox-Davies, ed., The Handbook to English Heraldry, 11th ed. (1914).

- ^ Ingle, Sean (18 July 2002). "Why do England have three lions on their shirts?". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ Boutell, Charles, 1859. The Art Journal London. p. 353.

- ^ Flori 1999f, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Flori 1999f, p. 192.

- ^ Fauchet, Claude (1581). Recueil de l'origine de la langue et poesie françoise. Paris: Mamert Patisson. pp. 130–131.

- ^ Holt, J. C. (1982). Robin Hood. Thames & Hudson. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-5002-5081-5.

- ^ a b John Gillingham, Kings and Queens of Britain: Richard I; Cannon & Hargreaves 2004, [page needed]

- ^ "Matthew's small sketch of a crossbow above Richard's inverted shield was probably intended to draw attention to the king's magnanimous forgiveness of the man who had caused his death, a true story first told by Roger of Howden, but with a different thrust. It was originally meant to illustrate Richard's stern, unforgiving character, since he only pardoned Peter Basil when he was sure he was going to die; but the Chronica Majora adopted a later popular conception of the generous hearted preux chevalier, transforming history into romance". Suzanne Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora, California studies in the history of art, vol. 21, University of California Press, 1987, p. 180.

- ^ Stubbs, William (2017). The Constitutional History of England. Vol. 1. Miami, Florida: HardPress. pp. 550–551. ISBN 978-1-5847-7148-7.

- ^ Curry, Andrew (8 April 2002). "The First Holy War". U.S. News & World Report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. News & World Report, L.P.

- ^ Phillips, Jonathan (2009). Holy Warriors: a Modern History of the Crusades. London, England: Random House. pp. 327–331. ISBN 978-1-4000-6580-6.

- ^ Turner, Ralph V.; Heiser, Richard R. (2000). The Reign of Richard Lionheart, Ruler of the Angevin empire, 1189–1199. Harlow: Longman. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-0-5822-5659-0.; Seel, Graham E. (2012). King John: An Underrated King. London: Anthem Press. Figure 1. ISBN 978-0-8572-8518-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

Bibliography

[edit]- Addison, Charles (1842). The History of the Knights Templars, the Temple Church, and the Temple. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Arnold, Benjamin (1999) [1985], German Knighthood 1050–1300, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0-1982-1960-6

- Barrow, G. W. S. (1967) [1956]. Feudal Britain: The Completion of the Medieval Kingdoms 1066–1314. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-7-2400-0898-0.

- Brown, Richard Allen (1976) [1954]. Allen Brown's English Castles. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-8438-3069-6.

- —— (2004). Die Normannen (in German). Albatros Im Patmos Verlag. ISBN 978-3-4919-6122-7.

- Brewer, Clifford (2000). The Death of Kings. London: Abson Books. ISBN 978-0-9029-2099-6.

- Cannon, John; Hargreaves, Anne (2004) [2001]. Kings and Queens of Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1986-0956-6.

- Flori, Jean (1999). Richard the Lionheart: Knight and King. Translated by Jean Birrell. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2047-0.

- —— (1999f), Richard Coeur de Lion: le roi-chevalier (in French), Paris: Biographie Payot, ISBN 978-2-2288-9272-8

- Gillingham, John (1979). Richard the Lionheart. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8129-0802-2.

- —— (1989). Richard the Lionheart. Butler and Tanner Ltd. ISBN 978-0-2977-9606-0.

- —— (1994). Richard Coeur De Lion: Kingship, Chivalry And War in the Twelfth Century. London: Hambledon & London. ISBN 978-1-8528-5084-5.

- —— (2002) [1999]. Richard I. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-3000-9404-6.

- —— (2004). "Richard I (1157–1199), king of England". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23498. Retrieved 16 August 2024. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- Graetz, Heinrich Bella Löwy; Bloch, Philipp (1902), History of the Jews, vol. 3, Jewish Publication Society of America, ISBN 978-1-5398-8573-3

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Hamilton, J.S. (2010). The Plantagenets: History of a Dynasty. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-5712-6. OL 28013041M.

- Harvey, John (1948), The Plantagenets, Fontana/Collins, ISBN 978-0-0063-2949-7

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Jones, Dan (2014). The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-1431-2492-4.

- Leese, Thelma Anna (1996). Royal: Issue of the Kings and Queens of Medieval England, 1066–1399. Heritage Books Inc. ISBN 978-0-7884-0525-9.

- Longford, Elizabeth (1989). The Oxford Book of Royal Anecdotes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1921-4153-8.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2005), Crusades: The Illustrated History (annotated, illustrated ed.), University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-4720-3127-6

- Martin, Nicole (18 March 2008). "Richard I slept with French king 'but not gay'". The Daily Telegraph. p. 11. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. See also "Bed-heads of state". The Daily Telegraph. 18 March 2008. p. 25. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008.

- McNeill, Tom (1992). English Heritage Book of Castles. London: English Heritage and B. T. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-7025-3.

- Oman, Charles (1991) [1924], A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages, Volume Two: 1278–1485 AD, Greenhill Books, ISBN 978-1-8536-7105-0

- Packard, Sydney (1922). "King John and the Norman Church". The Harvard Theological Review. 15 (1): 15–40. doi:10.1017/s0017816000001383. S2CID 160036290.

- Prestwich, J.O.; Prestwich, Michael (10 October 2004). The Place of War in English History, 1066–1214. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-8438-3098-6.

- Purser, Toby (2004). Medieval England 1042–1228 (illustrated ed.). Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-4353-2760-6.

- Ralph of Coggeshall. Chronicon Anglicanum (in Latin). Essex, England.

- Roger of Hoveden (1853). The annals of Roger de Hoveden: comprising The history of England and of other countries of Europe from A.D. 732 to A.D. 1201. Vol. 2. Translated by Riley, Henry T. London: H.G. Bohn.

- Stafford, Pauline; Nelson, Janet L.; Martindale, Jane (2001). Law, Laity and Solidarities. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5836-3.

- Turner, Ralph (1997). "Richard Lionheart and English Episcopal Elections". Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies. 29 (1): 1–13. doi:10.2307/4051592. JSTOR 4051592.

- Turner, Ralph V.; Heiser, Richard R (2000). The Reign of Richard Lionheart, Ruler of the Angevin empire, 1189–1199. Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-5822-5659-0.

- Warren, W. Lewis (1991). King John. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-4134-5520-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Ambroise (2003). The History of the Holy War. Translated by Ailes, Marianne. Boydell Press.

- Ralph of Diceto (1876). Stubbs, William (ed.). Radulfi de Diceto Decani Lundoniensis Opera Historica (in Italian). London.

- Berg, Dieter (2007). Richard Löwenherz (in German). Darmstadt.

- Edbury, Peter W. (1996). The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation. Ashgate. ISBN 1-8401-4676-1.

- Gabrieli, Francesco, ed. (1969). Arab Historians of the Crusades. University of California Press. ISBN 0-5200-5224-2.

- Maalouf, Amin (1984), "L'impossible rencontre", in J'ai lu (ed.), Les Croisades vues par les Arabes (in French), J'ai Lu, p. 318, ISBN 978-2-2901-1916-7

- Nelson, Janet L., ed. (1992). Richard Cœur de Lion in History and Myth. ISBN 0-9513-0856-4.

- Nicholson, Helen J., ed. (1997). The Chronicle of the Third Crusade: The Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi. Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-0581-7.

- Roger of Hoveden (1867). Stubbs, William (ed.). Gesta Regis Henrici II & Gesta Regis Ricardi Benedicti Abbatis (in Latin). London.

- Roger of Hoveden (1868–1871). Stubbs, William (ed.). Chronica Magistri Rogeri de Houedene (in Latin). London.

- Runciman, Steven (1951–1954). A History of the Crusades. Vol. 2–3.

- Stubbs, William, ed. (1864). Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi (in Latin). London.

- Medieval Sourcebook: Guillame de Tyr (William of Tyre): Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum (History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea).

- Williams, Patrick A (1970). "The Assassination of Conrad of Montferrat: Another Suspect?". Traditio. XXVI.

External links

[edit]- Richard I at the official website of the British monarchy

- Richard I at BBC History

- Works by or about Richard I of England at the Internet Archive

- Portraits of King Richard I at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Richard I of England