Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Yakut language

View on Wikipedia| Yakut | |

|---|---|

| Sakha | |

| саха тыла, saxa tıla | |

| Pronunciation | [säˈχä tʰɯˈɫä] |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Yakutia, Magadan Oblast, Amur Oblast, Krasnoyarsk Krai (Evenkiysky District) |

| Ethnicity | Yakuts |

Native speakers | c. 450,000[1] |

Turkic

| |

| Cyrillic (formerly Latin and Cyrillic-based) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | sah |

| ISO 639-3 | sah |

| Glottolog | yaku1245 |

| ELP | Yakut |

Sakha language

| |

Yakut is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

The Yakut language (/jəˈkuːt/ yə-KOOT),[2] also known as the Sakha language (/səˈxɑː/ sə-KHAH) or Yakutian, is a Siberian Turkic language spoken by around 450,000 native speakers—primarily by ethnic Yakuts. It is one of the official languages of the Sakha Republic, a republic in the Russian Federation.

The Yakut language has a large number of loanwords of Mongolic origin, a layer of vocabulary of unclear origin, as well as numerous recent borrowings from Russian. Like other Turkic languages, Yakut is an agglutinative language and features vowel harmony.

Classification

[edit]Yakut is a member of the Northeastern Common Turkic family of languages, which also includes Shor, Tuvan and Dolgan. Like most Turkic languages, Yakut has vowel harmony, is agglutinative and has no grammatical gender. Word order is usually subject–object–verb. Yakut has been influenced by Tungusic and Mongolian languages.[3]

Historically, Yakut left the community of Common Turkic speakers relatively early.[4] Due to this, it diverges in many ways from other Turkic languages and mutual intelligibility between Yakut and other Turkic languages is low[5] and many cognate words are hard to notice when heard. Nevertheless, Yakut contains many features which are important for the reconstruction of Proto-Turkic, such as the preservation of long vowels.[6] Even with significant divergent features, Sakha (i.e. Yakut) is typically grouped with the Common Turkic branch of the family rather than the Oghuric branch with Chuvash. A relatively few scholars (W. Radlov and others) have expressed the view that Sakha (i.e. Yakut) is not Turkic.

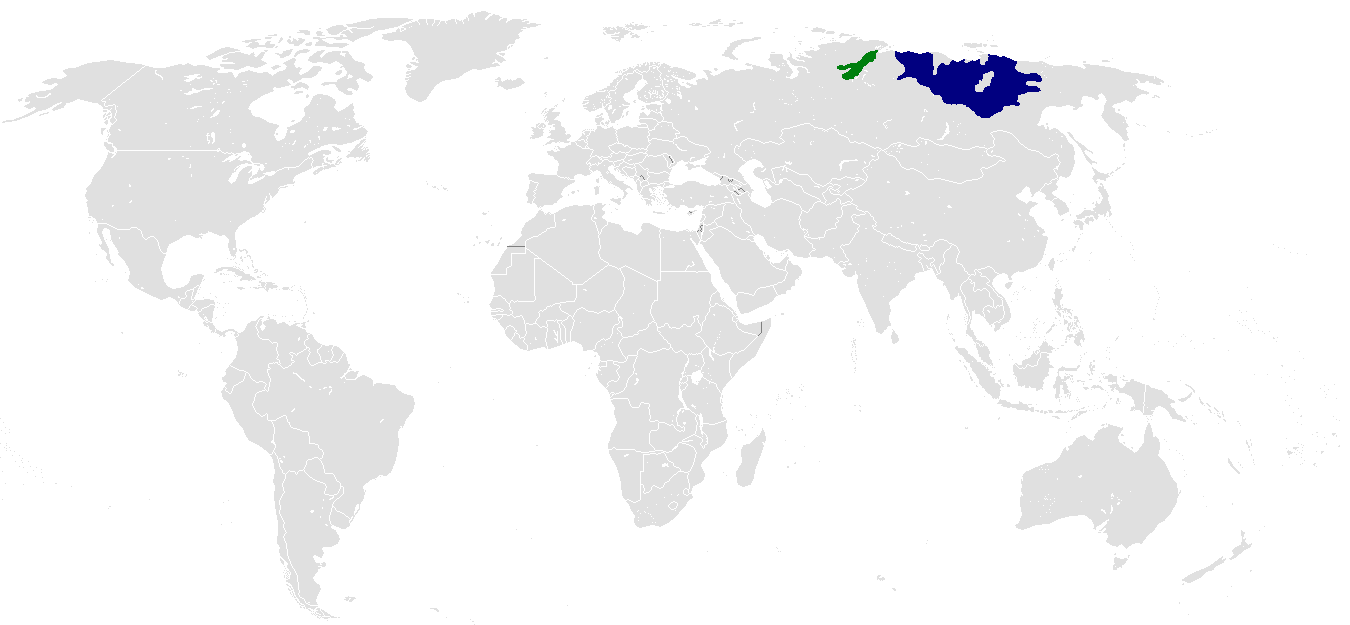

Geographic distribution

[edit]Yakut is spoken mainly in the Sakha Republic. It is also used by ethnic Yakuts in Khabarovsk Region and a small diaspora in other parts of the Russian Federation, Kazakhstan, Turkey and other parts of the world. Dolgan, a close relative of Yakut, which formerly was considered by some a dialect of Yakut,[7] is spoken by Dolgans in Krasnoyarsk Region. Yakut is widely used as a lingua franca by other ethnic minorities in the Sakha Republic – more Dolgans, Evenks, Evens and Yukagirs speak Yakut rather than their own languages. About 8% of people of ethnicities other than Yakut living in Sakha claimed knowledge of the Yakut language in the 2002 census.[8]

Phonology

[edit]Consonants

[edit]Yakut has the following consonants phonemes,[9] where the IPA value is provided in slashes '//' and the native script value is provided in bold followed by the romanization in parentheses.

| Bilabial | Dental/ alveolar |

Palatal | Velar/ uvular |

Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | /m/ м (m) |

/n/ н (n) |

/ɲ/ нь (ń) |

/ŋ/ ҥ (ŋ) |

||

| Plosive / Affricate |

voiceless | /p/ п (p) |

/t/ т (t) |

/t͡ʃ/ ч (č) |

/k/ к (k) |

|

| voiced | /b/ б (b) |

/d/ д (d) |

/d͡ʑ/ дь (ǰ) |

/ɡ/ г (g) |

||

| Fricative | voiceless | /s/ с (s) |

/χ/ х (x) |

/h/ һ (h) | ||

| voiced | /ʁ/ ҕ (ɣ) |

|||||

| Approximant | plain | /l/ л (l) |

/j/ й (y) |

|||

| nasalized | /ȷ̃/ й (ỹ) |

|||||

| Flap | /ɾ/ р (r) |

|||||

- /n, t, d/ are laminal denti-alveolar [n̪, t̪, d̪], whereas /s, l, ɾ/ are alveolar [s, l, ɾ].

- The nasal glide /ȷ̃/ is not distinguished from /j/ in the orthography, where both are written as ⟨й⟩. Thus айыы can be ayïï [ajɯː] 'deed, creation, work' or aỹïï [aȷ̃ɯː] 'sin, transgression'.[10] The nasal glide /ȷ̃/ has a very restricted distribution, appearing in very few words.[11]

- /ɾ/ is pronounced as a flap [ɾ] between vowels, e.g. орон (oron) [oɾon] 'place', and as a trill [r] at the end of words, e.g. тур (tur) [tur] 'stand'.[12][13]

- /ɾ/ does not occur at the beginning of words in native Yakut words; borrowed Russian words with onset /ɾ/ are usually rendered with an epenthetic vowel, e.g. Russian рама (rama) > Yakut араама (araama) 'frame'.

Yakut is in many ways phonologically unique among the Turkic languages. Yakut and the closely related Dolgan language are the only Turkic languages without postalveolar sibilants. Additionally, no known Turkic languages other than Yakut and Khorasani Turkic have the palatal nasal /ɲ/.

Consonant assimilation

[edit]Consonants at morpheme boundaries undergo extensive assimilation, both progressive and regressive.[14][15] All suffixes possess numerous allomorphs. For suffixes which begin with a consonant, the surface form of the consonant is conditioned on the stem-final segment. There are four such archiphonemic consonants: G, B, T, and L. Examples of each are provided in the following table for the suffixes -GIt (second-person plural possessive suffix, oɣoɣut 'your [pl.] child'), -BIt (first-person plural possessive suffix, oɣobut, 'our child'), -TA (partitive case suffix, tiiste 'some teeth'), -LArA (third-person plural possessive suffix, oɣoloro 'their child'). Note that the alternation in the vowels is governed by vowel harmony (see the main article and the below section).

| Consonant archiphoneme |

Immediately preceding sound (example) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High vowel i, u, ï, ü (kihi) |

Low vowel a, e, o, ö (oɣo) |

/l/ (uol) |

/j,ɾ/ (kötör) |

Voiceless consonants (tiis) |

/χ/ (ïnaχ) |

Nasal (oron) | |

| G -GIt |

[g] kihi-git |

[ɣ] oɣo-ɣut |

[g] uol-gut |

[g] kötör-güt |

[k] tiis-kit |

[χ] ïnaχ-χït |

[ŋ] oroŋ-ŋut[a] |

| B -BIt |

[b] kihi-bit |

[b] oɣo-but |

[b] uol-but |

[b] kötör-büt |

[p] tiis-pit |

[p] ïnaχ-pït |

[m] orom-mut[b] |

| T -TA |

[t] kihi-te |

[t] oɣo-to |

[l] uol-la |

[d] kötör-dö |

[t] tiis-te |

[t] ïnaχ-ta |

[n] oron-no |

| L -LArA |

[l] kihi-lere |

[l] oɣo-loro |

[l] uol-lara |

[d] kötör-dörö |

[t] tiis-tere |

[t] ïnaχ-tara |

[n] oron-noro |

| 'person' | 'child' | 'boy' | 'bird' | 'tooth' | 'cow' | 'bed' | |

There is an additional regular morphophonological pattern for [t]-final stems: they assimilate in place of articulation with an immediately following labial or velar. For example at 'horse' > akkït 'your [pl.] horse', > appït 'our horse'.

Debuccalization

[edit]Yakut initial s- corresponds to initial h- in Dolgan and played an important operative rule in the development of proto-Yakut, ultimately resulting in initial Ø- < *h- < *s- (example: Dolgan huoq and Yakut suox, both meaning "not").[clarification needed] The historical change of *s > h, known as debuccalization, is a common sound-change across the world's languages, being characteristic of such language groups as Greek and Indo-Iranian in their development from Proto-Indo-European, as well as such Turkic languages as Bashkir, e.g. höt 'milk' < *süt.[16]

Debuccalization is also an active phonological process in modern Yakut. Intervocalically the phoneme /s/ becomes [h]. For example the /s/ in кыыс (kïïs) 'girl' becomes [h] between vowels:[17]

kïïs

girl

>

>

kïïh-ïm

girl-POSS.1SG

'girl; daughter' > 'my daughter'

Vowels

[edit]Yakut has twenty phonemic vowels: eight short vowels, eight long vowels,[a] and four diphthongs. The following table gives broad transcriptions for each vowel phoneme,[b] as well as the native script bold and romanization in italics:

| Front | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | ||

| Close | short | /i/ и (i) |

/y/ ү (ü) |

/ɯ/ ы (ï [c]) |

/u/ у (u) |

| long[d] | /iː/ ии (ii) |

/yː/ үү (üü) |

/ɯː/ ыы (ïï) |

/uː/ уу (uu) | |

| Diphthong | /ie/ иэ (ie) |

/yø/ үө (üö) |

/ɯa/ ыа (ïa) |

/uɔ/ уо (uo) | |

| Open | short | /e/ э (e) |

/ø/ ө (ö) |

/a/ а (a) |

/ɔ/ о (o) |

| long | /eː/ ээ (ee) |

/øː/ өө (öö) |

/aː/ аа (aa) |

/ɔː/ оо (oo) | |

- ^ The long vowel phonemes /eː/, /ɔː/, and /øː/ appear in very few words and are thus considered marginal phonemes.[18]

- ^ Note that these vowels are extremely broad. Narrower transcriptions[19] transcribe the high back non-front vowel ы as central /ɨ/. The front non-high unrounded open vowel in э, ээ, and иэ are more accurately [ɛ], [ɛː], [iɛ], respectively.

- ^ ы is occasionally Romanized as y,[20] consistent with the BGN/PCGN romanization of Russian Cyrillic. Turkologists and Altaicists tend to transcribe the vowel as ï,[21] or as ɨ.[22]

- ^ Some authors romanize long vowels with a macron (e.g. /iː/ ī, /yː/ ǖ)[5] or with a colon (e.g. /iː/ i:/iː, /yː/, ü:/üː).[23]

Vowel harmony

[edit]Like other Turkic languages, a characteristic feature of Yakut is progressive vowel harmony. Most root words obey vowel harmony, for example in кэлин (kelin) 'back', all the vowels are front and unrounded. Yakut's vowel harmony in suffixes is the most complex system in the Turkic family.[24] Vowel harmony is an assimilation process where vowels in one syllable take on certain features of vowels in the preceding syllable. In Yakut, subsequent vowels all take on frontness and all non-low vowels take on lip rounding of preceding syllables' vowels.[25] There are two main rules of vowel harmony:

- Frontness/backness harmony:

- Front vowels are always followed by front vowels.

- Back vowels are always followed by back vowels.

- Rounding harmony:

- Unrounded vowels are always followed by unrounded vowels.

- Close rounded vowels always occur after close rounded vowels.

- Open unrounded vowels do not assimilate in rounding with close rounded vowels.

The quality of the diphthongs /ie, ïa, uo, üö/ for the purposes of vowel harmony is determined by the first segment in the diphthong. Taken together, these rules mean that the pattern of subsequent syllables in Yakut is entirely predictable, and all words will follow the following pattern:[26] Like the consonant assimilation rules above, suffixes display numerous allomorphs determined by the stem they attach to. There are two archiphoneme vowels I (an underlyingly high vowel) and A (an underlyingly low vowel).

| Category | Final vowel in stem |

Suffix vowels |

|---|---|---|

| Unrounded, back | a, aa, ï, ïï, ïa | a, aa, ï, ïï, ïa |

| Unrounded, front | e, ee, i, ii, ie | e, ee, i, ii, ie |

| Rounded back | u, uu, uo | a, aa, u, uu, uo |

| Rounded, front, close | ü, üü, üö | e, ee, ü, üü, üö |

| Rounded, back | o, oo | o, oo, u, uu, uo |

| Rounded, open, low | ö, öö | ö, öö, ü, üü, üö |

| Archiphonemic vowel |

Preceding vowel | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | |||||

| unrounded (i, ii, ie, e, ee) |

rounded | unrounded (ï, ïï, ïa, a, aa) |

rounded | |||

| high (ü, üü, üö) |

low (ö, öö) |

high (u, uu, uo) |

low (o, oo) | |||

| I | i | ü | ï | u | ||

| A | e | ö | a | o | ||

Examples of I can be seen in the first-person singular possessive agreement suffix -(I)m:[27] as in (a):

|

a. aat-ïm name-POSS.1SG 'my name' |

et-im meat-POSS.1SG 'my meat' |

uol-um son-POSS.1SG 'my son' |

üüt-üm milk-POSS.1SG 'my milk' |

The underlyingly low vowel phoneme A is represented through the third-person singular agreement suffix -(t)A[28] in (b):

|

b. aɣa-ta father-POSS.3SG 'his/her father' |

iỹe-te mother-POSS.3SG 'his/her mother' |

oɣo-to child-POSS.3SG 'his/her child' |

töbö-tö top-POSS.3SG 'his/her top' |

uol-a son-POSS.3SG 'his/her son' |

Orthography

[edit]After three earlier phases of development, Yakut is currently written using the Cyrillic script: the modern Yakut alphabet, established in 1939 by the Soviet Union, consists of all the Russian characters with five additional letters and two digraphs for phonemes not present in Russian: Ҕҕ, Ҥҥ, Өө, Һһ, Үү, Дь дь, and Нь нь, as follows:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ҕ ҕ | Д д | Дь дь | Е е | Ё ё |

| Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ҥ ҥ |

| Нь нь | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Һ һ | Т т | У у |

| Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы |

| Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

| Letter | А | Б | В | Г | Ҕ | Д | Дь | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ҥ | Нь | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Һ | Т | У | Ү | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | а | бэ | вэ | гэ | ҕэ | дэ | дьэ | е | ё | жэ | зэ | и | ый | кы | эл | эм | эн | ҥэ | ньэ | о | ө | пэ | эр | эс | һэ | тэ | у | ү | эф | хэ | цэ | че | ша | ща | [a] | ы | [b] | э | ю | я |

| IPA | /a/ | /b/ | /v/ | /g/ | /ɣ/ | /d/ | /d͡ʒ/ | /(j)e/ | /jo/ | /ʒ/ | /z/ | /i/ | /j/, /ȷ̃/ | /k/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ | /ŋ/ | /ɲ/ | /ɔ/ | /ø/ | /p/ | /ɾ/ | /s/ | /h/ | /t/ | /u/ | /y/ | /f/ | /χ/ | /t͡s/ | /t͡ʃ/ | /ʃ/ | /ɕː/ | /◌.j/ | /ɯ/ | /◌ʲ/ | /e/ | /ju/ | /ja/ |

Long vowels are represented through the doubling of vowels, e.g. үүт (üüt) /yːt/ 'milk', a practice that many scholars follow in romanizations of the language.[29][30][31]

The full Yakut alphabet contains letters for consonant phonemes not present in native words (and thus not indicated in the phonology tables above): the letters В /v/, Е /(j)e/, Ё /jo|/, Ж /ʒ/, З /z/, Ф /f/, Ц /t͡s/, Ш /ʃ/, Щ /ɕː/, Ъ, Ю /ju/, Я /ja/ are used exclusively in Russian loanwords. In addition, in native Yakut words, the soft sign ⟨Ь⟩ is used exclusively in the digraphs ⟨дь⟩ and ⟨нь⟩.

Transliteration

[edit]There are numerous conventions for the Romanization of Yakut. Bibliographic sources and libraries typically use the ALA-LC Romanization tables for non-Slavic languages in Cyrillic script.[32] Linguists often employ Turkological standards for transliteration,[33] or a mixture of Turkological standards and the IPA.[22] In addition, others employ Turkish orthography.[34] Comparison of some of these systems can be seen in the following:

бу

/bu

DEM

ыт

ɯt

dog

аттааҕар

at.taːɣar

horse-COMP

түргэнник

tyrgɛn.nɪk

fast-ADV

сүүрэр

syːrɛr/

run-PRES

'This dog runs faster than a horse'[37]

эһэ

/ɛhɛ

bear

бөрөтөөҕөр

bøɾøtøːɣør

wolf-COMP

күүстээх

kyːstɛːχ/

strong-have

'A bear is stronger than a wolf'[37]

| дьон | айыы | бу | ыт | аттааҕар | түргэнник | сүүрэр | эһэ | бөрөтөөҕөр | күүстээх | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | /d͡ʒon/ | /ajɯː/ | /bu/ | /ɯt/ | /at.taːɣar/ | /tyrgɛn.nɪk/ | /syːrɛr/ | /ɛhɛ/ | /bøɾøtøːɣør/ | /kyːstɛːχ/ | |

| Turkological | Krueger | ǰon | ajıı | bu | ıt | attaaɣar | türgennik | süürer | ehe | böröötööɣör | küüsteeχ |

| Johanson | ǰon | ayï: | bu | ït | atta:ɣar | türgännik | sü:rär | ähä | börötö:ɣör | kü:stä:χ | |

| Robbeets & Savalyev |

ʤon | ïyïː | bu | ït | attaːɣar | türgennik | süːrer | ehe | börötöːɣör | kü:steːχ | |

| ALA-LC[32] | d'on | aĭyy | bu | yt | attaaghar | tu̇rgennik | su̇u̇rer | eḣe | bȯrȯtȯȯghȯr | ku̇u̇steekh | |

| KNAB[38] | djon | ajy: | bu | yt | atta:ǧar | türgennik | sü:rer | eḩe | börötö:ǧör | kü:ste:h | |

| Turkish orthography | con | ayıı | bu | ıt | attaağar | türgennik | süürer | ehe | börötööğör | küüsteex | |

Grammar

[edit]Syntax

[edit]The typical word order can be summarized as subject – adverb – object – verb; possessor – possessed; adjective – noun.

Pronouns

[edit]Personal pronouns in Yakut distinguish between first, second, and third persons and singular and plural number.

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | мин (min) | биһиги (bihigi) | |

| 2nd person | эн (en) | эһиги (ehigi) | |

| 3rd person | human | кини[a] (kini) | кинилэр (kiniler) |

| non-human | ол (ol) | олор (olor) | |

Although nouns have no gender, the pronoun system distinguishes between human and non-human in the third person, using кини (kini, 'he/she') to refer to human beings and ол (ol, 'it') to refer to all other things.[39]

Grammatical number

[edit]Nouns have plural and singular forms. The plural is formed with the suffix /-LAr/, which may surface as -лар (-lar), -лэр (-ler), -лөр (-lör), -лор (-lor), -тар (-tar), -тэр (-ter), -төр (-tör), -тор (-tor), -дар (-dar), -дэр (-der), -дөр (-dör), -дор (-dor), -нар (-nar), -нэр (-ner), -нөр (-nör), or -нор (-nor), depending on the preceding consonants and vowels. The plural is used only when referring to a number of things collectively, not when specifying an amount. Nouns have no gender.

| Final sound basics | Plural affix options | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Vowels, /l/ | -lar, -ler, -lor, -lör | kïïllar 'beasts', eheler 'bears', oɣolor 'children', börölör 'wolves' |

| /k, p, s, t, χ/ | -tar, -ter, -tor, -tör | attar 'horses', külükter 'shadows', ottor, 'herbs', bölöxtör 'groups' |

| /y, r/ | -dar, -der, -dor, -dör | baaydar 'rich people', ederder 'young people'[a] xotoydor 'eagles', kötördör 'birds' |

| /m, n, ŋ/ | -nar, -ner, -nor, -nör | kïïmnar 'sparks', ilimner 'fishing nets', oronnor 'beds', bödöŋnör 'large ones' |

- ^ baydar 'rich people' and ederder 'young' people are examples of predicative adjectives (i.e. baay 'rich', eder 'young') being pluralized

There is a parallel construction with plural suffix -ттАр, which can even be added to adjectives e.g.

- уол (uol) 'boy; son' > уолаттар (uolattar),

- эр 'man' > эрэттэр or folkloric эрэн (cf. Uzbek folkloric eran)

- хотун 'noblewoman' > хотуттар or хотут

- тойон 'commander' > тойоттор or тойот

- оҕонньор 'old man, husband' > оҕонньоттор

- кэм 'time' > кэммит

- дьон 'people' > дьоммут

- ойун 'shaman' > ойууттар

- доҕор 'friend' > доҕоттор

- күөл 'lake' > күөлэттэр

- хоһуун 'hard-working' > хоһууттар

- буур 'male' (of deer and elk) > буураттар ('male deers')

- кыыс (kïïs) 'girl; daughter' > кыргыттар (kïrgïttar) (standard, suppletive) or кыыстар (dialectal, regular).

The word кыргыттар, disregarding the composite -(ы)ттар plural suffix, has cognates in numerous Turkic languages, such as Uzbek (qirqin 'bondwoman'), Bashkir, Tatar, Kyrgyz (кыз-кыркын 'girls'), Chuvash (хӑрхӑм), Turkmen (gyrnak) and extinct Qarakhanid, Khwarezmian and Chaghatay.

Nominal inflection (cases)

[edit]Only Sakha (Yakut) has a rich case system that differs markedly from all the other Siberian Turkic languages. It has retained the ancient comitative case from Old Turkic (due to strong influence from Mongolian) while in other Turkic languages, the old comitative has become an instrumental case. However, in Sakha language the Old Turkic locative case has come to denote partitive case, thus leaving no case form for the function of locative. Instead, locative, dative and allative cases are realized through Common Turkic dative suffix:

Норуокка

"хайа

хаппыыстата"

диэн

аатынан

биллэр

хайаҕа

үүнэр

үүнээйи.

A plant known among locals as "mountain cabbage" that grows on a mountain.

where -ҕа is dative and хайаҕа literally means "to the mountain". Furthermore, (in addition to locative,) genitive and equative cases are lost as well. Yakut has eight grammatical cases: nominative (unmarked), accusative -(n)I, dative -GA, partitive -TA, ablative -(t)tan, instrumental -(I)nAn, comitative -LIIn, and comparative -TAAɣAr.[40] Examples of these are shown in the following table for a vowel-final stem eye (of Mongolian origin) 'peace' and a consonant-final stem uot 'fire':

| eye 'peace' | uot 'fire' | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | eye | uot |

| Accusative | eyeni | uotu |

| Dative | eyeɣe | uokka |

| Partitive[a] | eyete | uotta |

| Ablative[b] | eyetten | uottan |

| Instrumental | eyenen | uotunan |

| Comitative | eyeliin | uottuun |

| Comparative[c] | eyeteeɣer | uottaaɣar |

- ^ Sakha partitive suffix is believed by some linguists to be an innovation stemming from the influence of Evenki which led the Old Turkic locative suffix to assume partitive function in Sakha; no other Turkic language has partitive suffix save for Khalaj and (nearly-extinct) Tofa.[41] Sakha partitive is similar to the corresponding Finnish partitive case.[42]

- ^ The Ablative suffix appears as -TAn following a consonant and -TTAn following a vowel. Clear examples of the former are ox 'arrow' → oxton 'from an/the arrow', oxtorton 'from (the) arrows'.

- ^ Sakha is the only language within the Turkic family to have comparative case.

The partitive object case indicates that just a part of an object is affected, e.g.:

Uː-ta

water-PTV

is!

drink-IMP.2SG

Drink some water!

The corresponding expression below with the object in the accusative denotes wholeness:

Uː-nu

water-ACC.

is!

drink-IMP.2SG

Drink [all] the water!

The partitive is only used in imperative or necessitative expressions, e.g.

Uː-ta

water-PT

a-γal-ϊaχ-χa

bring-PRO-DAT

naːda.

necessary.

One has to bring some water.

Note the word naːda is borrowed from Russian надо (must).

A notable detail about Yakut case is the absence of the genitive,[43] a feature which some argue is due to historical contact with Evenki (a Tungusic language), the language with which Sakha (i.e. Yakut) was in most intensive contact.[44] Possessors are unmarked, with the possessive relationship only being realized on the possessed noun itself either through the possessive suffix[45] (if the subject is a pronoun) or through partitive case suffix (if the subject is any other nominal). For example, in (a) the first-person pronoun subjects are not marked for genitive case; neither do full nominal subjects (possessors) receive any marking, as shown in (b):

min

1SG.NOM

oɣo-m

child-POSS.1SG

/

/

bihigi

1PL.NOM

oɣo-but

child-POSS.1PL

'my son' / 'our child'

Masha

Masha.NOM

aɣa-ta

father-PTV.3SG

'Masha's father'

Note the change in shape of the dative suffix when used with and without pronominal suffixes:

"Хоско киирдэ" - (He/She) entered a/the room.

"Хоһугар киирдэ" - (He/She) entered his/her room.

-ко and -гар are both dative suffixes (and -у serves to denote "his/her").

Verbal inflection

[edit]Tenses

[edit]E. I. Korkina (1970) enumerates following tenses: present-future tense, future tense and eight forms of past tense (including imperfect).

Sakha imperfect has two forms: analytic and synthetic. Both forms are based on the aorist suffix -Ar, common to all Turkic languages. The synthetic form, despite expressing a past aspect, lacks the Common Turkic past suffix, which is very unusual for a Turkic language. This is considered by some to be another influence from Even, a Tungusic language. Example:

Биһиги

иннибитинэ

бу

кыбартыыраҕа

оҕолоох

ыал

олорбуттар.

Before us, a family with children used to live here.

Imperative

[edit]Sakha, under Evenki/Even contact influence, has developed a distinction in imperative: immediate imperative ("do now!") and future/remote imperative ("do later!").[1]

| Positive | Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate | -∅/-(I)ŋ | -ma-∅/-ma-(I)ŋ |

| Remote | -A:r/-A:r-(I)ŋ | -(I)m-A:r/-(I)m-A:r-(I)ŋ |

Immediate imperative example:

Николай

Атласов

алаадьыны

буһарыы

туһунан

кэпсиирин

истиҥ

Listen to Nikolay Atlasov’s talk about preparing oladyi.

Denominal verbs

[edit]Common Turkic has denominal suffix -LA, used to create verbs from nouns (i.e. Uzbek tishla= 'to bite' from tish 'tooth'). The suffix is also present in Sakha (in various shapes, due to vowel harmony), but Sakha takes it a step further: theoretically verbs can be created from any noun by attaching to that noun the denominal suffix:

Арай

биирдэ,

теннистии

туран,

хараҕым

ааһан

иһэр

кыыска

хатана

түспүтэ.

Once upon a time, while playing tennis, my eyes caught a sight of a girl passing by.

where the word for “playing tennis” (теннистии) is derived from теннистээ, “to play tennis”, created by attaching the suffix -тээ.

Converbs

[edit]Sakha converbs end in -(A)n as opposed to Common Turkic -(I)B. They express simultaneous and sequential action and are also used with auxiliary verbs, preceding them:

Күлүгүн

кытта

охсуһан

таҕыстыҥ

You continuously fought with his shadow.

Simultaneous and sequential actions are expressed through the converbial suffix -а(н):

Самаан

сайын

бүтэн,

айылҕа

барахсан

уһун

улук

уутугар

оҥостордуу

от-мас

хагдарыйан

күөх

солко

симэҕин

ыһыктар

күһүҥҥү

тымныы

салгыннаах,

сиппэрэҥ

күннэр

тураллар

Summer having past, very cold and sleety days of autumn arise wherein the mother nature dresses in robe made green by plants growing in shallow waters.

Кэлэн

иһэллэр,

итириктэр

After coming, they would drink (and) get drunk.

Questions

[edit]The Sakha yes–no question marker is enclitic duo or du:, whereas almost all other Turkic languages use markers of the type -mi, compare:

Күөрэгэй

kyœregej

lark-NOM

ырыатын

ïrïa-tï-n

song-3SG.POSS-ACC

истэҕин

ist-e-ɣin

hear-PRS-2SG

дуо?

=duo?

=Q

Do you hear the song of larks?

and the same sentence in Uzbek (note the question suffix -mi in contrast to Sakha):

To’rg’ay jirini eshit(a)yapsanmi?

Question words in Yakut remain in-situ; they do not move to the front of the sentence. Sample question words include: туох (tuox) 'what', ким (kim) 'who', хайдах (xajdax) 'how', хас (xas) 'how much; how many', ханна (xanna) 'where', and ханнык (xannïk) 'which'.

| Pronoun | Translation |

|---|---|

| ким | who |

| туох | what |

| хаһан | when |

| ханна | where |

| хайдах | how |

| хас | how many |

| төһө | how much |

| хайа | which, how |

| хайаа= | do what? |

Ordinal numbers

[edit]Ordinals are formed by appending -үс to numerals:

Казань

-

дойдубут

үһүс

тэбэр

сүрэҕэ

Qazan - the third beating heart of our country

Rusisms

[edit]Together with having a considerable number of Russian loanwords, Sakha language features Russisms in colloquial speech. Example:

Курууса

жарылабын.

I am frying a chicken

Both words in the sentence above are loans from Russian: "Курууса" - (курица "kuritsa"), 'chicken"; "жарылабын" - cf. "жарить", 'to fry'.

Vocabulary

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

The Yakut lexicon includes loans from Russian, Mongolic, Evenki, and number of words from other languages or of unknown origin. The Mongolic loans do not appear to be traceable to any specific Mongolic language, but a few have been traced to Buryat and Khalkha Mongolian. They are widely dispersed through various categories of words with words relating to the home and law having the most Mongolic loans. Russian loans on the contrary are much more widespread but less evenly dispersed though various types of words. Words relating to the modern world, clothing, and the home have the most Russian influence.[46]

Oral and written literature

[edit]The Yakut have a tradition of oral epic in their language called Олоҥхо ("Olonkho"), traditionally performed by skilled performers. The subject matter is based on Yakut mythology and legends. Versions of many Olonkho poems have been written down and translated since the 19th century, but only a very few older performers of the oral Olonkho tradition are still alive. They have begun a program to teach young people to sing this in their language and revive it, though in a modified form.[47]

The first printing in Yakut was a part of a book by Nicolaas Witsen published in 1692 in Amsterdam.[48]

In 2005, Marianne Beerle-Moor, director of the Institute for Bible Translation, Russia/CIS, was awarded the Order of Civil Valour by the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) for the translation of the New Testament into Yakut.[49]

Probably the first-ever Islamic book in Sakha language, "Билсиҥ: Ислам" ("Get to know: Islam"), written by a Sakha convert born in the village of Asyma, was published in 2012.[50] This short book (52 pages) is intended to be a condensed introduction to the fundamentals of Islam in Sakha. The author occasionally employs native terms (which are also used in Olonkho corpus) to render some Islamic concepts, such as the jinn.

Examples

[edit]Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

| Novgorodov alphabet (1920–1929) | зɔn barɯta beje sꭣltatɯgar ꭣnna bɯra:bɯgar teŋ bꭣlan tꭢry:ller. kiniler barɯ ꭢrkꭢ:n ꭢjdꭢ:q, sꭣbasta:q bꭣlan tꭢry:ller, ꭣnna beje bejeleriger tɯlga ki:riniges bɯhɯ:lara dɔʃɔrdɔhu: tɯ:nna:q bꭣlꭣqta:q. |

| Yañalif (1929–1939) | Çon вarьta вeje suoltatьgar uonna вьraaвьgar teꞑ вuolan tɵryyller. Kiniler вarь ɵrkɵn ɵjdɵɵq, suoвastaaq вuolan tɵryyller, uonna вeje вejeleriger tьlga kiiriniges вьhььlara doƣordohuu tььnnaaq вuoluoqtaaq. |

| Cyrillic (1939–present) | Дьон[a] барыта бэйэ[b] суолтатыгар уонна быраабыгар[c] тэҥ буолан төрүүллэр. Кинилэр бары өркөн өйдөөх, суобастаах[d] буолан төрүүллэр, уонна бэйэ бэйэлэригэр тылга кииринигэс быһыылара доҕордоһуу[e] тыыннаах буолуохтаах. |

| Common Turkic alphabet | Con barıta beye suoltatıgar uonna bıraabıgar teñ buolan törüüller. Kiniler barı örkön öydööx, suobastaax buolan törüüller, uonna beye beyeleriger tılga kiiriniges bıhıılara doğorhuu tıınnaax buoluoxtaax. |

| International Phonetic Alphabet | [ɟ͡ʝɔn barɯta beje su͜ɔɫtatɯgar u͜ɔnna bɯraːbɯgar teŋ bu͜ɔɫan tøryːller ‖ kiniler barɯ ørkøːn øjdøːx su͜ɔbastaːχ bu͜ɔɫan tøryːller u͜ɔnna beje bejeleriger tɯɫga kiːriniges bɯhɯːɫara dɔʁɔrdɔhuː tɯːnnaːq bu͜ɔɫu͜ɔχtaːχ ǁ] |

| English translation | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

See also

[edit]- Yakuts

- Dolgan language

- Semyon Novgorodov – the inventor of the first IPA-based Yakut alphabet

References

[edit]- ^ "Sakha language". Britannica.

- ^ "Yakut". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Forsyth 1994, p.56: "Their language...Turkic in its vocabulary and grammar, shows the influence of both Tungus and Mongolian.".

- ^ Johanson 2021, pp. 20, 24.

- ^ a b Stachowski & Menz 1998.

- ^ Johanson 2021, p. 19.

- ^ Antonov 1997.

- ^ Russian Census 2002. 6. Владение языками (кроме русского) населением отдельных национальностей по республикам, автономной области и автономным округам Российской Федерации Archived 2006-11-04 at the Wayback Machine (Knowledge of languages other than Russian by the population of republics, autonomous oblast and autonomous districts) (in Russian)

- ^ Pakendorf & Stapert 2020.

- ^ Krueger 1962, p. 67.

- ^ Pakendorf & Stapert 2020, p. 432.

- ^ Krueger 1962, pp. 68–9.

- ^ Kharitonov 1947, p. 63.

- ^ Kharitonov 1947, p. 64.

- ^ Stachowski & Menz 1998, p. 420.

- ^ "Ubrjatova, E. I. 1960 Opyt sravnitel'nogo izuc˙enija fonetic˙eskix osobennostej naselenija nekotoryx rajonov Jakutskoj ASSR. Moscow. 1985. Jazyk noril'skix dolgan. Novosibirsk: "Nauka" SO. In Tungusic Languages 2 (2): 1–32. Historical Aspects of Yakut (Saxa) Phonology. Gregory D. S. Anderson. University of Chicago" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ Johanson 2021, p. 36.

- ^ Johanson 2021, p. 283.

- ^ Pakendorf & Stapert 2020, p. 433; Anderson 1998.

- ^ Vinokurova 2005; Baker & Vinokurova 2010.

- ^ Robbeets & Savalyev 2020, p. lxxxii; Johanson 2021; Krueger 1962; Stachowski & Menz 1998.

- ^ a b Anderson 1998.

- ^ Pakendorf 2007; Pakendorf & Stapert 2020

- ^ Johanson 2021, p. 315.

- ^ Krueger 1962, pp. 48–9; Stachowski & Menz 1998, p. 419.

- ^ Johanson 2021, p. 316.

- ^ -(I)m indicates that this suffix appears as -m in vowel-final words (e.g. oɣo 'child' > oɣom 'my child'.

- ^ Consonants in parentheses indicate that the suffix loses the consonant in consonant-final words, e.g. uol 'son' > uola 'his/her son.'

- ^ Krueger 1962.

- ^ Vinokurova 2005.

- ^ Petrova 2011.

- ^ a b "Non-Slavic languages (in Cyrillic Script)" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 3, 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Krueger 1962; Stachowski & Menz 1998; Johanson 2021; Menz & Monastyrev 2022

- ^ Kirişçioğlu 1999.

- ^ "дьон". sakhatyla.ru. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "айыы". sakhatyla.ru. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Krueger 1962, p. 89.

- ^ "Romanization" (PDF). August 2019.

- ^ Kirişçioğlu, M. Fatih (1999). Saha (Yakut) Türkçesi Grameri. Ankara: Türk Dil Kurumu. ISBN 975-16-0587-3.

- ^ Krueger 1962; Stachowski & Menz 1998; Vinokurova 2005

- ^ Suihkonen, Pirkko; Comrie, Bernard; Solovyev, Valery (18 July 2012). Argument Structure and Grammatical Relations. John Benjamins. p. 205. ISBN 9789027274717.

- ^ Bárány, András; Biberauer, Theresa; Douglas, Jamie; Vikner, Sten (28 May 2021). Syntactic architecture and its consequences III. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 54. ISBN 9783985540044.

- ^ Krueger 1962; Stachowski & Menz 1998; Baker & Vinokurova 2010; Johanson 2021.

- ^ Pakendorf 2007.

- ^ Baker & Vinokurova 2010.

- ^ Haspelmath, Martin; Tadmor, Uri (2009). Loanwords in the worlds languages A comprehensive handbook. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 506–508. ISBN 978-3-11-021843-5.

- ^ Robin Harris. 2012. Sitting "under the mouth": decline and revitalization in the Sakha epic tradition "Olonkho". Doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia.

- ^ "Предпосылки возникновения якутской книги". Память Якутии. Archived from the original on 2018-11-03. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ^ "People". Institute for Bible Translation, Russia/CIS. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "В Якутии издали книгу об исламе на языке саха".

Bibliography

[edit]- Anderson, Gregory D. S. (1998). "Historical Aspects of Yakut (Saxa) Phonology". Turkic Languages. 2 (2): 1–32.

- Antonov, N. K. (1997). Tenshev, E. R. (ed.). Yazyki mira (seriya knig) (in Russian). Indrik (izdatelstvo). pp. 513–524. ISBN 5-85759-061-2.

- Baker, Mark C; Vinokurova, Nadya (2010). "Two modalities of case assignment: case in Sakha". Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. 28 (3): 593–642. doi:10.1007/s11049-010-9105-1. S2CID 18614663.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521477710.

- Johanson, Lars (2021). Turkic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 20, 24.

- Kharitonov, L. N. (1947). Samouchitel' jakutskogo jazyka (in Russian). Jakutskoe knizhnoe izdatel'stvo.

- Kirişçioğlu, M. Fatih (1999). Saha (Yakut) Türkçesi Grameri (in Turkish). Ankara: Türk Dil Kurumu. ISBN 975-16-0587-3.

- Krueger, John R. (1962). Yakut Manual. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Menz, Astrid; Monastyrev, Vladimir (2022). "Yakut". In Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Á. (eds.). The Turkic Languages (Second ed.). Routledge. pp. 444–59. doi:10.4324/9781003243809. ISBN 978-0-415-73856-9. S2CID 243795171.

- Robbeets, Martine; Savalyev, Alexander (2020). "Romanization Conventions". In Robbeets, Martine; Savalyev, Alexander (eds.). The Oxford Guide to the Transeurasian Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. lii–lxxxii.

- Pakendorf, Brigitte (2007). Contact in the prehistory of the Sakha (Yakuts): Linguistic and genetic perspectives (Thesis). Universiteit Leiden.

- Pakendorf, Brigitte; Stapert, Eugénie (2020). "Sakha and Dolgan, the North Siberian Turkic Languages". In Robbeets, Martine; Savalyev, Alexander (eds.). The Oxford Guide to the Transeurasian Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 430–45. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198804628.003.0027. ISBN 978-0-19-880462-8.

- Petrova, Nyurguyana (2011). Lexicon and Clause-Linkage Properties of the Converbal Constructions in Sakha (Yakut) (Thesis). University of Buffalo.

- Stachowski, Marek; Menz, Astrid (1998). "Yakut". In Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Á. (eds.). The Turkic Languages. Routledge.

- Ubryatova, E.I., ed. (1980). Grammatika sovremennogo jakutskogo literaturnogo jazyka. Moscow: Nauka.

- Vinokurova, Nadezhda (2005). Lexical Categories and Argument Structure: A study with reference to Sakha (Thesis). Universiteit Utrecht.

External links

[edit]Language-related

[edit]- Yakut Vocabulary List (from the World Loanword Database)

- Yakut thematic vocabulary lists

- [3]

- "Comparison of Yakut and Mongolian vocabulary". Archived from the original on February 5, 2008.

- Yakut texts with Russian translations in the Internet Archive – heroic poetry, fairy tales, legends, proverbs, etc.

- Sakhalyy suruk – Yakut Unicode fonts and Keyboard Layouts for PC

- Sakhatyla.ru – On-line Yakut–Russian, Russian–Yakut dictionary

- Yakut–English Dictionary Archived April 2, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- BGN/PCGN romanization tool for Yakut

- Sakha Open World Archived 2006-06-19 at the Wayback Machine – MP3's of Sakha Radio

Content in Yakut

[edit]- Sakha Open World – Орто Дойду Archived 2017-09-22 at the Wayback Machine – A platform to promote the Yakut Language on the web; News, Lyrics, Music, Fonts, Forum, VideoNews (in Yakut, Unicode)

- Baayaga village website – news and stories about and by the people of Baayaga (in Yakut)

- Kyym.ru – site of Yakut newspaper

- НВК Саха (NVK Sakha) Yakut language news channel on YouTube

Yakut language

View on GrokipediaClassification and History

Classification

The Yakut language, also known as Sakha, belongs to the Turkic language family and is classified within the Siberian Turkic branch, more specifically the Northeastern subgroup.[1] This positioning distinguishes it from the more southern and western branches of the Turkic family, such as the Oghuz or Kipchak groups, which are predominant in Central Asia and the Near East.[7] Yakut maintains close linguistic ties with Dolgan, a variety spoken by a small ethnic group in northern Siberia, forming what is often described as a dialect continuum due to their high degree of mutual intelligibility and shared structural features.[8] In contrast to many Central Asian Turkic languages, where vowel length has largely been lost or merged, Yakut preserves several Proto-Turkic long vowels, a retention that aids in reconstructing earlier stages of the family.[9] The language exhibits substrate influences from non-Turkic sources, including potential Paleo-Siberian elements in its basic lexicon of unknown origin and Mongolic layers evident in vocabulary and phonological traits acquired through historical contacts.[1][5] These influences reflect the complex areal interactions in Siberia, where Turkic speakers encountered indigenous populations.Historical Development

The Yakut language, also known as Sakha, originated from Proto-Turkic speakers who had migrated to the Lake Baikal region in South Siberia, with its ancient form emerging by the 6th–7th centuries CE among tribes such as the Kurykans.[1] These early speakers underwent migrations northward from the Lake Baikal region into the Lena River basin between the 13th and 15th centuries, a process associated with the expansion of the Mongol Empire. This migration involved a small founder population, evidenced by genetic studies showing a bottleneck around 1,300 years ago, contributing to Sakha's divergence from other Turkic languages, and included assimilation of local Evenk and Yukaghir populations.[1] This relocation isolated Yakut from other Turkic languages, fostering unique developments while incorporating substrate influences from Paleo-Siberian tongues.[10] Key historical contacts shaped Yakut's evolution, beginning with intensive Mongolic interactions during the Mongol Empire (13th–14th centuries), resulting in approximately 2,000–2,500 lexical borrowings related to administration, culture, and daily life.[1] Further influences from Tungusic languages, such as Evenk, contributed phonetic shifts (e.g., fricative developments) and lexical borrowings, forming an areal linguistic zone in northeastern Siberia.[10] Russian contact intensified from the 17th century onward, following the establishment of the Yakutsk fort in 1632, leading to widespread bilingualism among Yakuts and the integration of over 3,000 Russian loanwords by the pre-revolutionary period, particularly in domains like technology and governance.[1] The development of a literary standard for Yakut began in the 19th century under the Russian Empire, with the first orthography reform in 1851 by Otto Boethlingk, who adapted the Cyrillic script with additional characters to represent Yakut phonemes in works like official documents and missionary texts.[11] This Cyrillic-based system supported early literature, such as A. Y. Uvarovsky's Reminiscences (1851). In the Soviet era, orthographic shifts occurred: a Latin-based alphabet (Yañalif variant) was introduced around 1922–1929 for education and publishing, reflecting broader Turkic latinization policies.[6] Standardization culminated in 1939–1940 with a return to a modified Cyrillic script, aligning Yakut writing more closely with Russian while accommodating vowel harmony and unique sounds, though it faced initial resistance from Sakha intellectuals.[11] This Cyrillic reform solidified the modern literary norm by the mid-20th century.[6]Geographic Distribution and Sociolinguistics

Geographic Distribution

The Yakut language, also known as Sakha, is primarily spoken in the Sakha Republic (Yakutia), a vast federal subject of Russia located in northeastern Siberia, encompassing an area of approximately 3,083,523 square kilometers.[12] This region stretches from the Lena River basin in the south to the Arctic Ocean in the north, forming the core homeland of the ethnic Sakha people who speak the language as their native tongue.[13] The language's distribution aligns closely with the republic's administrative boundaries, where it serves as one of the two official languages alongside Russian.[14] Within the Sakha Republic, significant concentrations of Yakut speakers are found in urban centers, particularly the capital city of Yakutsk, which has a population exceeding 300,000 and hosts the largest community of native speakers.[15] Other notable urban areas include Neryungri in the south and Mirny in the central diamond-mining district, where Yakut is commonly used among local Sakha populations engaged in industry and administration.[16] These cities represent key hubs for the language's everyday use in education, media, and commerce. The Yakut language exhibits dialectal variation across the republic, with four primary groups: Central, Vilyuy, Northwestern, and Northeastern dialects. The Central dialect, spoken around the middle Lena River valley including areas near Yakutsk and the Aldan River, forms the basis for the standard literary Yakut.[1] The Vilyuy dialect is found along the Vilyuy River basin. Northwestern dialects prevail in the Arctic coastal zones, such as along the Anabar and Olenyok rivers, showing influences from neighboring Tungusic languages like Evenki, while Northeastern dialects are spoken in areas like Verkhoyansk, with Even influence.[5][1] These variations are mutually intelligible, facilitating communication across the expansive territory. Beyond the Sakha Republic, small Yakut-speaking communities exist in adjacent Russian regions, including Magadan Oblast, where historical migrations and economic ties have established pockets of speakers.[17] Internationally, diaspora groups have formed due to recent migrations, notably in Kazakhstan, where Sakha individuals have sought refuge from political and economic pressures in Russia, and in the United States, with scattered communities in states like Washington and California tracing back to 19th-century explorations and modern relocations.[18][19] Overall, Yakut has approximately 450,000 speakers worldwide, predominantly within Russia.[13]Number of Speakers and Language Status

The Yakut language, spoken primarily by the ethnic Sakha (Yakuts), has an estimated 450,000 native speakers, concentrated mainly in the Sakha Republic (Yakutia) of Russia. According to the 2021 Russian census, 95% of ethnic Yakuts (approximately 445,000 individuals) declared Sakha as their native language.[6][20] This figure accounts for the core speech community, though some estimates reach up to 480,000 when including closely related groups.[16] Additionally, Yakut serves as a second language for smaller numbers of speakers from neighboring indigenous groups, such as Evenks, Evens, and Yukaghirs, who often adopt it as a regional lingua franca in multilingual settings.[5][21] Yakut holds official status as a co-state language alongside Russian in the Sakha Republic, as enshrined in the republic's 1992 Constitution and the Law on Languages in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) of the same year.[22][23] This legal framework mandates its use in education, media, government administration, and public signage, promoting its role in official domains across the republic.[24] Bilingualism is widespread among Yakut speakers, with approximately 94% of the population in Yakutia proficient in Russian.[25] Russian predominates in urban centers like Yakutsk, where code-switching and language shift toward Russian are common in professional and social interactions.[26][27] According to the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, Yakut is classified as vulnerable as of the latest assessments, with intergenerational transmission at risk due to ongoing urbanization, migration to Russian-speaking areas, and historical Russification policies that prioritize Russian in broader societal functions.[28][29] Despite its official recognition, these pressures contribute to a gradual decline in daily usage outside home and cultural contexts.[30]Revitalization Efforts and Modern Usage

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, revitalization efforts for the Yakut (Sakha) language gained momentum in the 1990s through legislative measures in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), including language laws that established Yakut as a state language alongside Russian and mandated its use in public spheres such as education and administration.[31] These initiatives were part of broader post-Soviet policies aimed at restoring indigenous linguistic rights, with the Republic's Language Law granting official status to Yakut and supporting its integration into daily life.[24] Ongoing state programs, such as the "Preservation and Development of State and Official Languages in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)," continue to fund activities like linguistic monitoring and sociolinguistic expeditions to sustain these efforts.[32] In education, bilingual programs are central to Yakut revitalization, particularly in the Sakha Republic's schools where Yakut serves as the medium of instruction for subjects up to grade 9 in select institutions, fostering proficiency among younger generations.[33] Urban initiatives in Yakutsk during the 2020s have emphasized school-based linguistic and cultural practices, demonstrating how civic engagement in the capital has embedded Yakut revival into local curricula and community activities, countering urban Russian dominance.[34] These programs have evolved over 25 years, from basic language classes to comprehensive immersion models that integrate Yakut with cultural education.[35] Technological advancements have bolstered Yakut's modern usage, with Google Translate adding support for the language in June 2024 as part of an expansion to 110 new languages, enhancing accessibility for its speakers.[36] Mobile applications like Сахалыы provide interactive self-tutoring for beginners, while online resources such as the electronic 15-volume Yakut dictionary and Leipzig Corpora Collection offer searchable corpora and bilingual tools for learners and researchers.[37][38][39] Social media platforms, including VKontakte groups dedicated to Sakha culture and language practice, host discussions and content in Yakut, promoting organic usage among urban youth and diaspora communities.[40] Cultural events and media further promote Yakut in contemporary contexts, exemplified by the Yhyakh festival, where Sakha diaspora in the United States gathered in Lynnwood, Washington, in June 2024 to celebrate traditional rites and language through rituals and performances.[41] The Sakha National Broadcasting Company (NVK Sakha) produces television and radio content in Yakut, including news, cultural programs, and even AI-assisted media, reaching audiences across the Republic and supporting linguistic immersion in daily broadcasting. These efforts collectively enhance Yakut's vitality amid globalization, blending tradition with innovation to engage both local and international audiences.[42]Phonology

Consonants

The Yakut language, also known as Sakha, possesses a consonant inventory of 18 phonemes, including bilabial and alveolar stops /p, b, t, d/, velar and uvular stops /k, g, q/, affricates /t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ/, nasals /m, n, ŋ/, liquid /r/ (with allophones and [ɾ]), lateral /l/, fricatives /s, χ/, approximant /j/, and a marginal glottal fricative /h/.[43] Some phonemes, such as /p, t͡ʃ, g, h/, occur primarily in loanwords and exhibit limited minimal pairs, reflecting Yakut's divergence from other Turkic languages while retaining uvulars like /q/ and /χ/ from Proto-Turkic origins; velar consonants /k, g, χ/ vary allophonically to uvular [q, ɣ, χ] before back vowels.[43][1][5] Allophonic variations affect several consonants, with /r/ realized as a flap [ɾ] in syllable-final position and a trill syllable-initially, while /l/ typically appears as velarized [ɫ].[43] Gemination arises in loanwords, particularly from Russian, where consonant length is maintained or induced for phonetic adaptation, as in borrowings exhibiting doubled obstruents.[44] Consonant assimilation includes both progressive and regressive types, such as nasal place assimilation leading to gemination, exemplified by /sop-pot/ → [soppót] '3sg negative'.[45] Voicing assimilation occurs across morpheme boundaries, where obstruents agree in voicing with the preceding segment, and word-final obstruents undergo devoicing.[43] Coronal consonants like /n/ and /t/ are particularly prone to assimilation in clusters.[45] Debuccalization is a distinctive process in Yakut, where the coronal fricative /s/ shifts to glottal intervocalically, as in *kiši → kihi 'person'.[1] This change, potentially reinforced by Tungusic substrate influence, represents an areal innovation absent in most other Turkic languages.[1][44]Vowels

The Yakut language, also known as Sakha, possesses a vowel system consisting of eight short phonemes and their eight long counterparts, totaling 16 monophthongal vowels. The short vowels are /a/, /e/, /ɯ/, /o/, /ø/, /i/, /u/, and /y/, distinguished by contrasts in frontness/backness, height, and rounding. For instance, /a/ is a low back unrounded vowel, /e/ is mid front unrounded, /ɯ/ is high back unrounded, /o/ is mid back rounded, /ø/ is mid front rounded, /i/ is high front unrounded, /u/ is high back rounded, and /y/ is high front rounded. Vowel length is phonemically contrastive, as evidenced by minimal pairs such as /at/ 'horse' versus /aːt/ 'name', where the duration differentiates meaning.[46][43] Yakut exhibits a two-way vowel harmony system primarily governed by palatal (front-back) harmony, in which suffixes alternate to match the frontness or backness of the root vowel, with /i/ and /ɯ/ often behaving as neutral vowels that do not trigger harmony but align with the preceding vowel's features. Labial harmony additionally applies, particularly for rounding in non-high vowels following rounded vowels, resulting in alternations like /oɣo-lor/ (with back rounded harmony) versus /kɯrsa-lar/ (unrounded). This harmony operates strictly within stems and across morpheme boundaries in native words, but exceptions occur in loanwords, where foreign vowels may disrupt the pattern, such as in borrowings from Russian that retain non-harmonizing sequences.[46][47][1] The language retains four diphthongs from Proto-Turkic origins: /ɯa/, /uo/, /ie/, and /yø/, which function as single phonological units and exhibit length distinctions in some contexts, such as /a/ versus /aː/ in monophthongs paralleling diphthongal contrasts. These diphthongs involve a glide from high to non-high vowels while preserving front-back and rounding agreement, for example /uot/ 'fire'. Phonemic length in diphthongs and monophthongs underscores their role in lexical distinctions inherited from earlier Turkic stages.[46][48] In terms of vowel quality and reduction, unstressed vowels tend to centralize, with high vowels like /i/ and /u/ lowering or laxing in non-prominent positions, such as word-finally (/i/ → [ɪ]). This process contributes to phonetic variation without altering phonemic contrasts. Historically, the Yakut vowel system derives from Proto-Turkic through mergers, including the coalescence of certain mid vowels and the retention of length oppositions that were lost in many other Turkic languages, alongside influences from substrate languages leading to centralized qualities in unstressed syllables.[43][48]Orthography

Cyrillic Script

The Yakut Cyrillic alphabet consists of 40 letters, comprising the standard 33 letters of the Russian Cyrillic alphabet plus seven additional characters: five letters (Ҕ ҕ for /ɣ/, Ҥ ҥ for /ŋ/, Ө ө for /ø/, Ү ү for /y/, and Һ һ for /h/) and two digraphs treated as distinct letters (Дь дь for /dʲ/ and Нь нь for /nʲ/).[6][13] Among the Russian letters, some such as в, е, ё, ж, з, ф, ц, ш, щ, ъ, ь, ю, and я appear primarily in Russian loanwords and are not used in native Yakut vocabulary.[6] The adoption of the Cyrillic script for Yakut began in the mid-19th century, with the first systematic alphabet developed in 1851 by German linguist Otto Boethlingk, who adapted the Russian Cyrillic with additional diacritics to transcribe Yakut sounds for linguistic and missionary purposes.[49] This early Cyrillic system was used sporadically until the early 20th century, when a Latin-based alphabet was introduced in 1917 by Sakha educator Semyon Novgorodov and implemented widely from 1929 to 1939 as part of Soviet latinization policies for Turkic languages.[49] Cyrillic was reinstated in 1939–1940 by Soviet decree, aligning Yakut with Russian orthographic norms while incorporating the five additional letters to better suit the language's needs.[49] Subsequent reforms in the 1950s refined the orthography for greater phonemic accuracy, standardizing the representation of long vowels through doubled letters (e.g., аа for long /aː/) and specific digraphs for palatalized consonants, such as дь for /dʲ/ and нь for /nʲ/, as well as ннь for a prolonged palatal nasal.[50] Affricates are typically rendered with digraphs like ч for the /tʃ/ sound, and uvular sounds may use combinations such as кы in certain contexts.[6] Punctuation and writing conventions follow standard Russian rules, including the use of commas, periods, and quotation marks, with no unique Yakut-specific deviations in everyday texts.[6] In linguistic resources like dictionaries, stress is occasionally marked with an acute accent (´) to indicate prosodic features important for Yakut pronunciation.[6]Transliteration Systems

Transliteration systems for the Yakut (Sakha) language convert its Cyrillic orthography into Latin script primarily for international scholarship, bibliographic cataloging, and geographic naming. These systems account for Yakut's unique Cyrillic letters—such as Ҕ, Ҥ, Ө, Ү, and Һ—while aligning with broader Cyrillic romanization standards. The International Organization for Standardization's ISO 9:1995 provides a one-to-one mapping for Slavic and non-Slavic Cyrillic alphabets, adapted for Yakut by assigning diacritics to special characters: Ҕ to ğ, Ҥ to ṅ, Ө to ô, Ү to ù, and Һ to ḥ, with standard mappings like х to x and ы to y.[51] This system prioritizes reversibility, allowing reconstruction of the original Cyrillic, but its diacritics can complicate readability in non-technical contexts. Scholarly and library conventions often employ the ALA-LC romanization, developed by the American Library Association and Library of Congress, which favors digraphs over diacritics for accessibility. In this scheme, Yakut-specific letters are rendered as Ҕ to gh, Ҥ to ng, Ө to ö, Ү to ü, and Һ to h, with х as kh and combinations like дь as dь (palatalized d).[52] The BGN/PCGN system, used by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names and Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use, closely mirrors ALA-LC for Yakut, applying gh for Ҕ, ng for Ҥ, ö for Ө, ü for Ү, and h for Һ, while handling loanword letters (e.g., ж as zh) per Russian conventions.[53] These systems ensure consistency in academic publications and maps, though variations arise in representing palatalization (e.g., нь as ny or n').| Cyrillic | ISO 9 | ALA-LC | BGN/PCGN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ҕ/ҕ | ğ | gh | gh |

| Ҥ/ҥ | ṅ | ng | ng |

| Ө/ө | ô | ö | ö |

| Ү/ү | ù | ü | ü |

| Һ/һ | ḥ | h | h |

| Х/х | x | kh | kh |

| Ы/ы | y | y | y |

Grammar

Nominal Morphology

The nominal morphology of the Yakut language (also known as Sakha) features agglutinative inflections on nouns to indicate case, number, and possession, reflecting its Turkic heritage with innovations from Siberian contact. Nouns typically stem from roots that undergo vowel harmony, with suffixes attaching in a fixed order: number, then possession, then case. This system allows for complex expressions of grammatical relations without prepositions, using postpositional cases for locative and instrumental functions.[55] Sakha employs eight cases: nominative, partitive, accusative, dative, ablative, comitative, instrumental, and comparative, each marked by suffixes that harmonize with the stem's vowels (front/back, rounded/unrounded). The nominative case is unmarked and serves as the default for subjects and predicates (e.g., ot 'fire' in subject position). The partitive marks indefinite direct objects with -tA (e.g., kinige-tA 'a book-PAR'). The accusative marks definite direct objects with -nI (e.g., kinige-ni 'the book-ACC'). The dative -GA indicates recipients or goals (e.g., uota-qa 'to the house-DAT'). The ablative -GAan expresses source or motion away (e.g., uota-qa:n 'from the house-ABL'). The comitative -LIIn denotes accompaniment (e.g., bèlè-liin 'with a knife-COM'). The instrumental -LIIn denotes means (e.g., bèlè-liin 'with a knife-INS'; shares form with comitative). The comparative -AAdAk compares equality (e.g., tùhuna-a:dak 'like a swan-COMP'). These cases are detailed in standard grammars, with some functional overlap.[56][57][5] Grammatical number is marked on nouns, with the singular form unmarked and the plural typically suffixed as -LAr (varying by harmony: -lar, -lèr, -lor, -lör) or -tAr after certain stems (e.g., ot-lar 'fires-PL'). Number markers precede possessive and case suffixes, enabling stacked inflections (e.g., uol-lar-y 'sons-PL-ACC').[55][56] Personal pronouns inflect for case like nouns, distinguishing singular and plural without gender; they are: 1SG min (I), 2SG en (you), 3SG kin (he/she human)/ ol (it non-human), 1PL bihigi (we), 2PL ehigi (you all), 3PL kiniler (they human)/ olor (they non-human). For example, the 1SG dative is min-i 'to me', and plural forms add appropriate suffixes (e.g., bihigi-nie 'to us'). Demonstrative pronouns include tän (this near), ol (that near), and kaɣan (that remote), also declining for case (e.g., tän-ni 'this-ACC'). Possessive pronouns derive from personal ones plus suffixes (e.g., min-nie 'mine'), but are less common than suffixed possession.[5][57] Possession is expressed alienably through the genitive case on the possessor or inalienably via person-number suffixes on the possessed noun, which precede case markers. Inalienable suffixes include 1SG -m(y) (e.g., ama-m 'my father'), 2SG -ŋ(ŋi) (e.g., ama-ŋ 'your father'), 3SG -A (e.g., ama-ta 'his father'), 1PL -bIt (e.g., ama-byt 'our father'), 2PL -ɢIt (e.g., ama-ɣyt 'your [pl] father'), and 3PL -LArA (e.g., ama-lara 'their father'). For alienable possession with genitive: ama-ta-ŋa üöte-te 'his father's house' (father-3SG-GEN house-3SG). These suffixes agree in person and number, with phonetic adjustments for harmony and assimilation, and are obligatory for definite possession in Turkic-style constructions.[58][59]Verbal Morphology

Verbal morphology in the Sakha language (also known as Yakut) is highly agglutinative, with verbs inflecting for person and number through suffixes attached to the stem. Subject agreement is marked by predicative suffixes in the present-future tense (e.g., -bin for 1SG in bar-a-bin "I go") and possessive suffixes in past tenses (e.g., -im for 1SG in bar-bït-im "I had gone").[46] Negation in non-past tenses is expressed via the suffix -ba(t) or -ma on the verb stem, while past negation uses the connegative form of the verb combined with the negative auxiliary e- (pronounced /eː/), as in the structure for "I did not go."[57][5] The language distinguishes several tenses and aspects in the indicative mood, primarily through suffixes and auxiliaries. The present-future tense is formed with -a/-ï (vowel harmony variants), as in kör-ö "sees." Past tenses include the direct/witnessed past with -dï/-tï (e.g., bar-dïm "I went," implying personal knowledge) and the indirect/evidential past with -bït (e.g., bar-bïtim "I went," for reported or inferred events).[46][13] Additional aspects encompass the perfective (-bït for completed actions), habitual (-ar for repeated events, e.g., bar-ar-ïm "I go habitually"), and durative forms using auxiliaries like tur-a "stand" for ongoing actions.[5] Evidentiality is grammatically marked in past tenses to differentiate direct experience from hearsay or inference, a feature distinguishing Sakha from many other Turkic languages.[60][13] The imperative mood lacks dedicated singular forms for the second person in immediate contexts (e.g., kel! "come!"), but plural imperatives use -ïŋŋa (e.g., kel-iŋŋa "come, you all!"). Prohibitives (negative imperatives) employ the particle eː or the suffix -(ï)ma, as in eː kel "don't come!" for immediate prohibition.[46][13] Remote imperatives add -a:r (e.g., kel-a:r "come later!"), with corresponding negative forms using eː. Non-finite verbal forms are extensive and play a key role in complex sentences. Converbs include the simultaneous converb -a/-ï (e.g., bar-a "while going") and the sequential converb -ïn (e.g., bar-ïn "after going"). Participles comprise the present -aan/-ïn (e.g., bar-aan "going"), past -ïr (e.g., bar-ïr "having gone"), and future -iax (e.g., bar-iax "who will go"). Denominal verbs are derived from nouns using the suffix -la- (e.g., from tïs "tooth" to tïs-la- "to tooth," meaning "to bite").[5] These forms allow for adverbial clauses and relative constructions without finite marking. Voice distinctions are marked by derivational suffixes inserted before tense and agreement. The causative voice uses -aa- or -tar/-iar (e.g., köl-öö-t "makes drink" from köl "drink"). The passive employs -ïl- (e.g., tut-ullun "is held" from tut "hold"), which can also function as an anticausative in some contexts. Reflexive voice is indicated by -na- or -(ï)n, often with vowel shortening (e.g., beye-n "self" from beye "body," yielding "to clothe oneself").[61][5][46]Syntax and Other Features

The Yakut language, also known as Sakha, exhibits a predominantly subject-object-verb (SOV) word order in its basic clause structure, though this order is not entirely rigid and can vary for discourse purposes such as emphasis or topicalization.[62] Like other Turkic languages, Sakha relies on postpositions rather than prepositions to indicate spatial, temporal, and other relational meanings; for example, the postposition kïtta ('with') follows the noun it modifies. The language is highly agglutinative, with words often formed by stacking multiple suffixes—up to five in a single stem—to encode grammatical relations, derivation, and inflection, allowing for compact expression of complex ideas within individual words.[63] Questions in Sakha are formed using interrogative particles and pronouns, distinguishing between yes/no and wh-questions. Yes/no questions typically employ the particle duo (or variants like -ba in cliticized form) placed at the end of the clause, as in Min tuhugun ołorobun? Duo? ('Did I sit on the chair?') to seek confirmation.[64] Wh-questions incorporate interrogative pronouns such as kim ('who'), tuoh ('what'), hanna ('where'), and hahaan ('when'), which occupy positions similar to their declarative counterparts, maintaining the SOV frame unless fronted for focus; for instance, Kim kelir? ('Who is coming?').[5] Ordinal numbers in Sakha are derived from cardinal numerals by adding the suffix -Is (with vowel harmony variants like -üs), reflecting its Turkic heritage; examples include biir-is ('first'), ikki-s ('second'), and üs-üs ('third'). Cardinal numerals from one to ten are: biir (1), ikki (2), üs (3), tüört (4), biäs (5), alta (6), sätte (7), aǵıs (8), toǵus (9), and uon (10).[57][65] Due to extensive contact with Russian, Sakha incorporates numerous Rusisms, including loanwords adapted into native morphology—such as Russian nouns converted to verbs via Sakha derivational suffixes—and calques that mirror Russian syntactic patterns, like direct translations of idiomatic expressions. In bilingual contexts, code-switching is prevalent, particularly intrasententially, where speakers alternate between Sakha and Russian elements, as documented in corpora of urban Yakutsk speech.[7][66] Among other distinctive features, Sakha lacks grammatical gender, treating nouns uniformly without masculine, feminine, or neuter distinctions, a trait shared with most Turkic languages. The language employs evidentiality markers, often through past tense suffixes or sentence-final particles, to indicate the source of information, such as direct observation (-a in recent past) versus inference (-büt in remote past). Sakha also favors a topic-comment structure, where the topic is marked for prominence at the clause periphery, facilitating flexible information packaging in discourse.[13]Vocabulary

The core vocabulary of Sakha consists primarily of words inherited from Proto-Turkic, forming the base lexicon with agglutinative structures typical of Turkic languages.[13] However, due to historical migrations and contacts, approximately 29% of the core vocabulary comprises loanwords, as analyzed in a database of 1,411 basic terms.[7] The largest layer of borrowings comes from Mongolic languages, accounting for about 11-13% of the core vocabulary (around 148-184 items, including derivatives), primarily acquired during the 13th-14th centuries under the Mongol Empire. These include nouns, verbs, and adjectives, such as дьыл ('year') from Mongolic dil. Russian loanwords constitute 17% (240 items), mostly nouns related to modern technology, administration, and daily life, with adaptations like kinige ('book') from Russian kniga. Tungusic influences, particularly from Evenki, contribute about 1% (14 items), focusing on terms for natural phenomena and cultural practices, such as words for reindeer herding. Minor borrowings from other sources, including Finno-Ugric, Indo-European, and indigenous Siberian languages, are negligible.[7][13] Loanwords are integrated into Sakha through phonological adaptation to vowel harmony and consonant rules, as well as morphological suffixation. For instance, Russian borrowings may undergo vowel shifts or cluster simplifications (e.g., samovar → sılaabaar), while older Mongolic loans fully assimilate. Verbs from Mongolic often take Sakha verbalizing suffixes like -la. This layering reflects Sakha's divergence from other Turkic languages while enriching its lexicon for Arctic and Siberian contexts.[7]Literature and Culture

Oral Traditions

The oral traditions of the Yakut (Sakha) people form a cornerstone of their pre-literate cultural heritage, encompassing epic narratives, mythological tales, and ritualistic chants that encode cosmology, moral lessons, and survival knowledge in the harsh Siberian environment. These traditions, transmitted intergenerationally through performance rather than writing, reflect the Yakuts' Turkic roots blended with local adaptations to the taiga landscape. Central to this heritage is the epic genre known as olonkho, which embodies heroic quests and spiritual conflicts. The olonkho epics are monumental poetic compositions, typically comprising 10,000 to 15,000 verses, recounting the adventures of legendary heroes who battle cosmic forces to protect humanity. Performed by skilled storytellers called olonkho-oyuun (or akyns), these narratives blend sung verses, prosaic recitatives, dramatic acting, and improvisation, often lasting several nights during communal gatherings. Themes revolve around warriors confronting deities, spirits, and animals, while also addressing historical transitions like the shift from nomadism. A prominent example is Nyurgun Bootur the Swift, which depicts the hero's exploits against malevolent entities in a tripartite universe of upper, middle, and lower worlds. In 2005, UNESCO proclaimed olonkho a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, recognizing its role in preserving Yakut identity; it was formally inscribed on the Representative List in 2008.[67] Yakut folklore extends beyond epics to include creation myths, riddles, and proverbs that illustrate a dualistic worldview pitting benevolent upper gods (Aiyy) against malevolent lower demons (Abasy). In these myths, the Aiyy—sky-dwelling creators of light, fertility, and order—emerge victorious in primordial wars, shaping the three-layered cosmos: the harmonious upper realm, the earthly middle plane inhabited by humans, and the chaotic underworld ruled by the Abasy, who embody disease, death, and disruption. Riddles and proverbs, often embedded in daily discourse, draw on natural phenomena like rivers and reindeer to impart wisdom, such as the proverb equating resilience to the enduring taiga pine. These elements bear traces of Evenki (Tungusic) influences from neighboring indigenous groups, evident in shared motifs of animistic spirits and shamanic intermediaries that enriched Yakut narratives through centuries of interaction in Sakha Republic.[68][69] Shamanistic chants integrate olonkho motifs into rituals, where performers invoke spirits through rhythmic recitations to heal, divine, or harmonize with nature. These oral invocations, passed down in rural communities, feature olonkho-style verses describing sacred sites and cosmic trees like Aal Luuk Mas, bridging epic storytelling with ceremonial practice to maintain spiritual equilibrium. Transmission remains vital among elders in remote villages, ensuring the chants' adaptability to contemporary ecological challenges. Preservation efforts in the 2020s have intensified through digital recordings and cultural festivals, countering the decline of traditional performers. Organizations like the Snowchange Cooperative document oral histories in Sakha communities, capturing olonkho variants and folklore via audio archives since the early 2000s, with ongoing projects emphasizing intergenerational sharing. The annual Ysyakh Olonkho festival, held around the summer solstice, revives these traditions through live performances of epics, chants, and dances, fostering communal transmission and UNESCO-aligned safeguarding in regions like Neryungri.[70][71][72]Written Literature

The written literature of the Yakut (Sakha) language emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, laying the foundation for a distinct national literary tradition through poetry and early prose that drew on folklore and cultural identity. A key figure in this period was A.I. Sofronov (pen name Alampa), a pioneering poet and writer whose works, including the 1912 short story "The Story" and the drama Lyubov / Taptal ("Love"), introduced innovative structures like the "notch formula"—ethical motifs rooted in Yakut philosophy—and addressed social conflicts of the time.[73][74][75] Sofronov's contributions were instrumental in establishing Yakut literature as a vehicle for national cultural formation, blending traditional elements with emerging modernist influences.[73] During the Soviet era, Yakut literature flourished under state support, emphasizing themes of socialism, collectivization, and the adaptation of folklore to ideological narratives, with prominent authors producing poetry, novels, and epic retellings. Platon A. Oyunsky (1893–1939), regarded as the founder of Soviet Yakut literature, adapted traditional olonkho epics into written form, notably in Nurgun Botur the Swift, a monumental work that preserved heroic folklore while aligning it with socialist realism.[76][77] Nikolai E. Mordvinov, another classic of this period, contributed early novels such as Springtime (1920s), which depicted the establishment of Soviet power in rural Yakutia and integrated folk motifs with revolutionary themes.[78][79] These writers, alongside figures like A.E. Kulakovsky, elevated Yakut literature's role in promoting ecological and moral education within a socialist framework.[78] In the post-Soviet period, Yakut literature has diversified, incorporating urban themes, historical reflections, and global influences while expanding genres such as poetry, novels, and children's literature to address contemporary identity and cultural sovereignty. Authors like N.A. Luginov have gained prominence with multi-volume historical novels, including the trilogy By Genghis Khan's Will (1997–2005), exploring Yakut origins and epic heritage in a modern context.[80] Other writers, such as V.S. Yakovlev-Dalan, have continued to weave folklore into prose, fostering a post-Soviet renaissance that revives national motifs amid globalization.[81] This era has seen increased focus on philosophical and ecological narratives, building on classics to navigate urban-rural divides and cultural preservation.[82] Publishing infrastructure has supported this development, with the National Publishing Company Bichik serving as the primary outlet for Yakut-language works since the post-Soviet transition, producing over 300 titles annually across fiction, children's books, and educational materials.[83][84] Literary recognition has been bolstered by ongoing state prizes, such as the Platon Oyunsky Award, which has honored contributions to Yakut literature since its establishment and continues to promote new voices in the 1990s and beyond.[77]Media and Digital Presence

The Yakut language, also known as Sakha, maintains a notable presence in print media through publications such as the newspaper Sakha Sirä, which features content in the native language and serves as a key outlet for regional news and cultural discourse.[85] Radio broadcasting in Yakut began in the early Soviet era, with stations like the Sakha State Radio providing daily programs in the language since the 1930s, building on earlier experimental Arctic transmissions from the 1920s that included indigenous content.[86] Television coverage expanded through the state broadcaster GTRK Sakha, which airs Yakut-language programming on regional affiliates of the federal Russia-1 network, including news and cultural shows that reach audiences across the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Yakut cinema has seen a significant boom since the 2010s, often referred to as "Sakhawood," with independent productions showcasing the language and local narratives; notable examples include the 2016 film The Bonfire, directed by Dmitry Davydov, which explores Sakha traditions and has gained international recognition.[87] These films, typically low-budget yet critically acclaimed, highlight themes of indigenous life in Siberia and are increasingly available on Russian streaming platforms like IVI, where select titles offer Yakut audio tracks or subtitles to broader audiences.[88] In the digital realm, the Sakha Wikipedia (sah.wikipedia.org) hosts over 17,000 articles as of November 2025, serving as a vital repository for encyclopedic knowledge in the language and supporting online learning efforts.[89] Social media platforms feature Yakut influencers, such as digital creator Verona, who share cultural and linguistic content on Instagram and YouTube, fostering community engagement among younger speakers. Mobile applications further enhance accessibility, with tools like the Саха Тыла dictionary app providing offline Yakut-Russian and Yakut-English translations, updated in 2024 to include expanded vocabulary and pronunciation aids.[90] Despite these advancements, Yakut media faces challenges from limited content production due to resource constraints in a remote region.Sample Texts

Useful Phrases

The following are common phrases in Sakha (Yakut), presented in Cyrillic script with Roman transliteration and English translation.[91]- Hello (informal): Дорообо (Doroobo) – Hello

- Thank you: Махтал (Maxtal) – Thank you