Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aquaculture of salmonids

View on WikipediaThe aquaculture of salmonids is the farming and harvesting of salmonid fish under controlled conditions for both commercial and recreational purposes. Salmonids (particularly salmon and rainbow trout), along with carp and tilapia, are the three most important fish groups in aquaculture.[2] The most commonly commercially farmed salmonid is the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar).

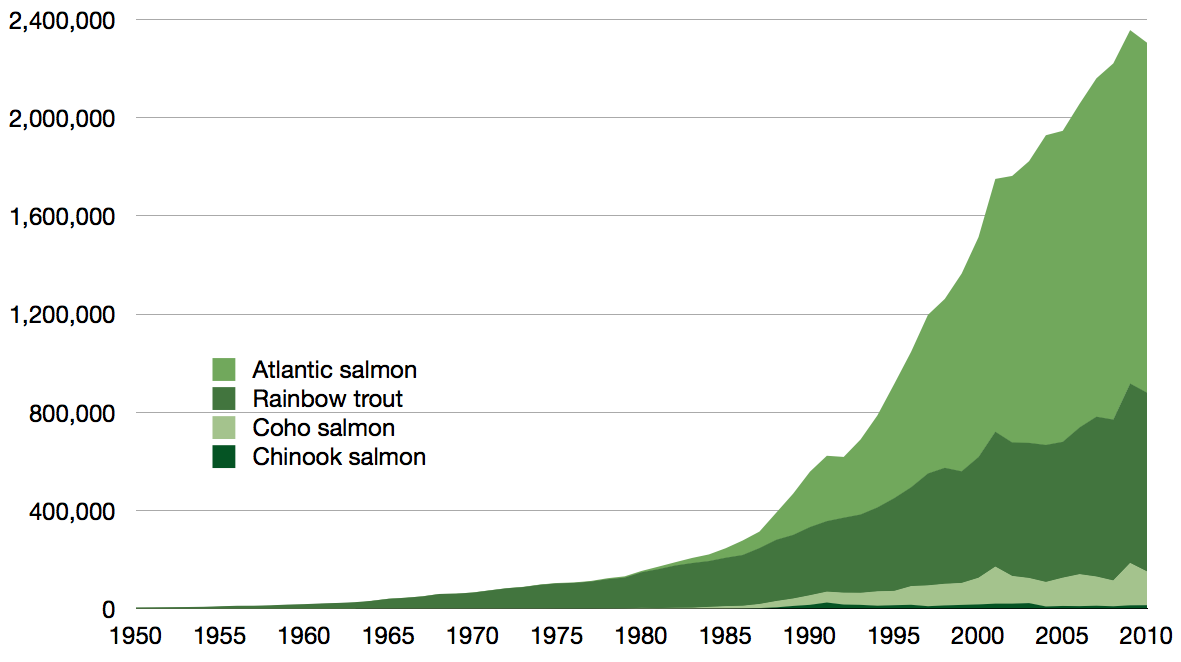

In the United States, Chinook salmon and rainbow trout are the most commonly farmed salmonids for recreational and subsistence fishing through the National Fish Hatchery System.[3] In Europe, brown trout are the most commonly reared fish for recreational restocking.[4] Commonly farmed non-salmonid fish groups include tilapia, catfish, black sea bass and bream. In 2007, the aquaculture of salmonids was worth USD $10.7 billion globally. Salmonid aquaculture production grew over ten-fold during the 25 years from 1982 to 2007. In 2012, the leading producers of salmonids were Norway, Chile, Scotland and Canada.[5]

Much controversy exists about the ecological and health impacts of intensive salmonids aquaculture. Of particular concern are the impacts on wild salmon and other marine life.

Methods

[edit]

The aquaculture or farming of salmonids can be contrasted with capturing wild salmonids using commercial fishing techniques. However, the concept of "wild" salmon as used by the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute includes stock enhancement fish produced in hatcheries that have historically been considered ocean ranching. The percentage of the Alaska salmon harvest resulting from ocean ranching depends upon the species of salmon and location.[6][not specific enough to verify] Methods of salmonid aquaculture originated in late 18th-century fertilization trials in Europe. In the late 19th century, salmon hatcheries were used in Europe and North America. From the late 1950s, enhancement programs based on hatcheries were established in the United States, Canada, Japan, and the USSR. The contemporary technique using floating sea cages originated in Norway in the late 1960s.[7]

Salmonids are usually farmed in two stages and in some places maybe more. First, the salmon are hatched from eggs and raised on land in freshwater tanks. Increasing the accumulated thermal units of water during incubation reduces time to hatching.[8] When they are 12 to 18 months old, the smolt (juvenile salmon) are transferred to floating sea cages or net pens anchored in sheltered bays or fjords along a coast. This farming in a marine environment is known as mariculture. There they are fed pelleted feed for another 12 to 24 months, when they are harvested.[9]

Norway produces 33% of the world's farmed salmonids, and Chile produces 31%.[10] The coastlines of these countries have suitable water temperatures and many areas well protected from storms. Chile is close to large forage fisheries which supply fish meal for salmon aquaculture. Scotland and Canada are also significant producers;[11][failed verification] and it was reported in 2012 that the Norwegian government at that time controlled a significant fraction of the Canadian industry.[12]

Modern salmonid farming systems are intensive. Their ownership is often under the control of huge agribusiness corporations, operating mechanized assembly lines on an industrial scale. In 2003, nearly half of the world’s farmed salmon was produced by just five companies.[13]

Hatcheries

[edit]Modern commercial hatcheries for supplying salmon smolts to aquaculture net pens have been shifting to recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS)s where the water is recycled within the hatchery. This allows location of the hatchery to be independent of a significant fresh water supply and allows economical temperature control to both speed up and slow down the growth rate to match the needs of the net pens.

Conventional hatchery systems operate flow-through, where spring water or other water sources flow into the hatchery. The eggs are then hatched in trays and the salmon smolts are produced in raceways. The waste products from the growing salmon fry and the feed are usually discharged into the local river. Conventional flow-through hatcheries, for example the majority of Alaska's enhancement hatcheries, use more than 100 tonnes (16,000 st) of water to produce a kg of smolts.

An alternative method to hatching in freshwater tanks is to use spawning channels. These are artificial streams, usually parallel to an existing stream with concrete or rip-rap sides and gravel bottoms. Water from the adjacent stream is piped into the top of the channel, sometimes via a header pond to settle out sediment. Spawning success is often much better in channels than in adjacent streams due to the control of floods which in some years can wash out the natural redds. Because of the lack of floods, spawning channels must sometimes be cleaned out to remove accumulated sediment. The same floods which destroy natural redds also clean them out. Spawning channels preserve the natural selection of natural streams as no temptation exists, as in hatcheries, to use prophylactic chemicals to control diseases. However, exposing fish to wild parasites and pathogens using uncontrolled water supplies, combined with the high cost of spawning channels, makes this technology unsuitable for salmon aquaculture businesses. This type of technology is only useful for stock enhancement programs.

Sea cages

[edit]Sea cages, also called sea pens or net pens, are usually made of mesh framed with steel or plastic. They can be square or circular, 10 to 32 m (33 to 105 ft) across and 10 m (33 ft) deep, with volumes between 1,000 and 10,000 m3 (35,000 and 353,000 cu ft). A large sea cage can contain up to 90,000 fish.

They are usually placed side by side to form a system called a seafarm or seasite, with a floating wharf and walkways along the net boundaries. Additional nets can also surround the seafarm to keep out predatory marine mammals. Stocking densities range from 8 to 18 kg (18 to 40 lb)/m3 for Atlantic salmon and 5 to 10 kilograms (11 to 22 lb)/m3 for Chinook salmon.[9][14]

In contrast to closed or recirculating systems, the open net cages of salmonid farming lower production costs, but provide no effective barrier to the discharge of wastes, parasites, and disease into the surrounding coastal waters.[13] Farmed salmon in open net cages can escape into wild habitats, for example, during storms.

An emerging wave in aquaculture is applying the same farming methods used for salmonids to other carnivorous finfish species, such as cod, bluefin tuna, halibut, and snapper. However, this is likely to have the same environmental drawbacks as salmon farming.[13][15]

A second emerging wave in aquaculture is the development of copper alloys as netting materials. Copper alloys have become important netting materials because they are antimicrobial (i.e., they destroy bacteria, viruses, fungi, algae, and other microbes), so they prevent biofouling (i.e., the undesirable accumulation, adhesion, and growth of microorganisms, plants, algae, tubeworms, barnacles, mollusks, and other organisms). By inhibiting microbial growth, copper alloy aquaculture cages avoid costly net changes that are necessary with other materials. The resistance of organism growth on copper alloy nets also provides a cleaner and healthier environment for farmed fish to grow and thrive.

Feeding

[edit]With the amount of worldwide fish meal production being almost a constant amount for the last 30+ years and at maximum sustainable yield, much of the fish meal market has shifted from chicken and pig feed to fish and shrimp feeds as aquaculture has grown in this time.[16]

Work continues on developing salmonid diet made from concentrated plant protein.[17] As of 2014, an enzymatic process can be used to lower the carbohydrate content of barley, making it a high-protein fish feed suitable for salmon.[18] Many other substitutions for fish meal are known, and diets containing zero fish meal are possible. For example, a planned closed-containment salmon fish farm in Scotland uses ragworms, algae, and amino acids as feed.[19] Some of the eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in Omega-3 fatty acids may be replaced by land-based (non-marine) algae oil, reducing the harvest of wild fish as fish meal.[20]

However, commercial economic animal diets are determined by least-cost linear programming models that are effectively competing with similar models for chicken and pig feeds for the same feed ingredients, and these models show that fish meal is more useful in aquatic diets than in chicken diets, where they can make the chickens taste like fish.[21] Unfortunately, this substitution can result in lower levels of the highly valued omega-3 content in the farmed product. However, when vegetable oil is used in the growing diet as an energy source and a different finishing diet containing high omega-3 content fatty acids from either fish oil, algae oils, or some vegetable oils are used a few months before harvest, this problem is eliminated.[22]

On a dry-dry basis, 2–4 kg of wild-caught fish are needed to produce 1 kg of salmon.[23] The ratio may be reduced if non-fish sources are added.[20] Wild salmon require about 10 kg of forage fish to produce 1 kg of salmon, as part of the normal trophic level energy transfer. The difference between the two numbers is related to farmed salmon feed containing other ingredients beyond fish meal and because farmed fish do not expend energy hunting.

In 2017 it was reported that the American company Cargill has been researching and developing alternative feeds with EWOS through its internal COMPASS programs in Norway, resulting in the proprietary RAPID feed blend. These methods studied macronutrient profiles of fish feed based upon geography and season. Using RAPID feed, salmon farms reduced the time to maturity of salmon to about 15 months, in a period one-fifth faster than usual.[24][25]

Other feed additives

[edit]As of 2008[update], 50-80% of the world fish oil production is fed to farmed salmonids.[26][27]

Farm raised salmonids are also fed the carotenoids astaxanthin and canthaxanthin, so their flesh colour matches wild salmon, which also contain the same carotenoid pigments from their diet in the wild.[28]

Harvesting

[edit]Modern harvesting methods are shifting towards using wet-well ships to transport live salmon to the processing plant. This allows the fish to be killed, bled, and filleted before rigor has occurred. This results in superior product quality to the customer, along with more humane processing. To obtain maximum quality, minimizing the level of stress is necessary in the live salmon until actually being electrically and percussively killed and the gills slit for bleeding.[29] These improvements in processing time and freshness to the final customer are commercially significant and forcing the commercial wild fisheries to upgrade their processing to the benefit of all seafood consumers.

An older method of harvesting is to use a sweep net, which operates a bit like a purse seine net. The sweep net is a big net with weights along the bottom edge. It is stretched across the pen with the bottom edge extending to the bottom of the pen. Lines attached to the bottom corners are raised, herding some fish into the purse, where they are netted. Before killing, the fish are usually rendered unconscious in water saturated in carbon dioxide, although this practice is being phased out in some countries due to ethical and product quality concerns. More advanced systems use a percussive-stun harvest system that kills the fish instantly and humanely with a blow to the head from a pneumatic piston. They are then bled by cutting the gill arches and immediately immersing them in iced water. Harvesting and killing methods are designed to minimize scale loss, and avoid the fish releasing stress hormones, which negatively affect flesh quality.[14]

Wild versus farmed

[edit]Wild salmonids are captured from wild habitats using commercial fishing techniques. Most wild salmonids are caught in North American, Japanese, and Russian fisheries. The following table shows the changes in production of wild salmonids and farmed salmonids over a period of 25 years, as reported by the FAO.[30] Russia, Japan and Alaska all operate major hatchery based stock enhancement programs. The resulting fish hatchery fish are defined as "wild" for FAO and marketing purposes.

| Species | 1982 | 2007 | 2013 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild | Farmed | Wild | Farmed | |||

| Atlantic salmon | 10,326 | 13,265 | 2,989 | 1,433,708 | 2,087,110[31] | |

| Steelhead | 171,946 | 604,695 | ||||

| Coho salmon | 42,281 | 2,921 | 17,200 | 115,376 | ||

| Chinook salmon | 25,147 | 8,906 | 11,542 | |||

| Pink salmon | 170,373 | 495,986 | ||||

| Chum salmon | 182,561 | 303,205 | ||||

| Sockeye salmon | 128,176 | 164,222 | ||||

| 1982 | 2007 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tonnes | percent | tonnes | percent | |

| Wild | 558,864 | 75 | 992,508 | 31 |

| Farmed | 188,132 | 25 | 2,165,321 | 69 |

| Overall | 746,996 | 3,157,831 | ||

Issues

[edit]The US in their dietary guidelines for 2010 recommends eating 8 ounces per week of a variety of seafood and 12 ounces for lactating mothers, with no upper limits set and no restrictions on eating farmed or wild salmon.[32] In 2018, Canadian dietary guidelines recommended eating at least two servings of fish each week and choosing fish such as char, herring, mackerel, salmon, sardines, and trout.[33]

Currently, much controversy exists about the ecological and health impacts of intensive salmonid aquaculture. Of particular concern are the impacts on wild salmonids and other marine life and on the incomes of commercial salmonid fishermen.[34] However, the 'enhanced' production of salmon juveniles – which for instance lead to a double-digit proportion (20-50%) of the Alaska's yearly ‘wild’ salmon harvest - is not void of controversy, and the Alaska salmon harvest are highly dependent on the operation of Alaska’s Regional Aquaculture Associations. Furthermore, the sustainability of enhanced/hatchery-based ‘wild’ caught salmon has long been hotly debated,[35] both from a scientific and political/marketing perspective. Such debate and positions were central to a 'halt' in the re-certification of Alaska salmon fisheries by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) in 2012.[36] The Alaska salmon fisheries subsequently re-attained MSC-certification status; however the heavily hatchery-dependent Prince William Sound (PWS) unit of certification (“one of the most valuable fishing area in the State”[37]) was for several years excluded from the MSC-certification (it remained ‘under assessment’ pending further analysis).

Disease and parasites

[edit]In 1972, Gyrodactylus, a monogenean parasite, was introduced with live trout and salmon from Sweden (Baltic stocks are resistant to it) into government-operated hatcheries in Norway. From the hatcheries, infected eggs, smolt, and fry were implanted in many rivers with the goal to strengthen the wild salmon stocks, but caused instead devastation to some of the wild salmon populations affected.[38]

In 1984, infectious salmon anemia (ISAv) was discovered in Norway in an Atlantic salmon hatchery. Eighty percent of the fish in the outbreak died. ISAv, a viral disease, is now a major threat to the viability of Atlantic salmon farming. It is now the first of the diseases classified on List One of the European Commission’s fish health regimen. Amongst other measures, this requires the total eradication of the entire fish stock should an outbreak of the disease be confirmed on any farm. ISAv seriously affects salmon farms in Chile, Norway, Scotland, and Canada, causing major economic losses to infected farms.[39] As the name implies, it causes severe anemia of infected fish. Unlike mammals, the red blood cells of fish have ribosomes, and can become infected with viruses. The fish develop pale gills, and may swim close to the water surface, gulping for air. However, the disease can also develop without the fish showing any external signs of illness, the fish maintain a normal appetite, and then they suddenly die. The disease can progress slowly throughout an infected farm, and in the worst cases, death rates may approach 100%. It is also a threat to the dwindling stocks of wild salmon. Management strategies include developing a vaccine and improving genetic resistance to the disease.[40]

In the wild, diseases and parasites are normally at low levels, and kept in check by natural predation on weakened individuals. In crowded net pens, they can become epidemics. Diseases and parasites also transfer from farmed to wild salmon populations. A recent study in British Columbia links the spread of parasitic sea lice from river salmon farms to wild pink salmon in the same river.[13] The European Commission (2002) concluded, "The reduction of wild salmonid abundance is also linked to other factors but there is more and more scientific evidence establishing a direct link between the number of lice-infested wild fish and the presence of cages in the same estuary."[41] It is reported that wild salmon on the west coast of Canada are being driven to extinction by sea lice from nearby salmon farms.[42] These predictions have been disputed by other scientists[43] and recent harvests have indicated that the predictions were in error. In 2011, Scottish salmon farming introduced the use of farmed ballan wrasse for the purpose of cleaning farmed salmon of ectoparasites.[44][45]

Globally, salmon production fell around 9% in 2015, in large part due to acute outbreaks of sea lice in Scotland and Norway.[46][47][48] Lasers are used to reduce lice infections.[49]

In the mid 1980s to the 1990s, bacterial kidney disease (BKD) caused by Renibacterium salmoninarum heavily impacted Chinook hatcheries in Idaho.[50] The disease causes granulomatous inflammation that can lead to abscesses in the liver, spleen, and kidneys.[51]

Pollution and contaminants

[edit]Salmonid farms are typically sited in marine ecosystems with good water quality, high water exchange rates, current speeds fast enough to prevent pollution of the bottom but slow enough to prevent pen damage, protection from major storms, reasonable water depth, and a reasonable distance from major infrastructure such as ports, processing plants, and logistical facilities such as airports. Logistical considerations are significant, and feed and maintenance labor must be transported to the facility and the product returned. Siting decisions are complicated by complex, politically driven permit problems in many countries that prevents optimal locations for the farms.

In sites without adequate currents, heavy metals can accumulate on the benthos (seafloor) near the salmon farms, particularly copper and zinc.[14]

Contaminants are commonly found in the flesh of farmed and wild salmon.[52] Health Canada in 2002 published measurements of PCBs, dioxins, furans, and PDBEs in several varieties of fish. The farmed salmonids population had nearly 3 times the level of PCBs, more than 3 times the level of PDBEs, and nearly twice the level of dioxins and furans seen in the wild population.[53] On the other hand, "Update of the monitoring of levels of dioxins and PCBs in food and feed", a 2012 study from the European Food Safety Authority, stated that farmed salmon and trout contained on average a many times lesser fraction of dioxins and PCBs than wild-caught salmon and trout."[54]

A 2004 study, reported in Science, analysed farmed and wild salmon for organochlorine contaminants. They found the contaminants were higher in farmed salmon. Within the farmed salmon, European (particularly Scottish) salmon had the highest levels, and Chilean salmon the lowest.[55] The FDA and Health Canada have established a tolerance/limit for PCBs in commercial fish of 2000 ppb[56] A follow-up study confirmed this, and found levels of dioxins, chlorinated pesticides, PCBs and other contaminants up to ten times greater in farmed salmon than wild Pacific salmon.[57] On a positive note, further research using the same fish samples used in the previous study, showed that farmed salmon contained levels of beneficial fatty acids that were two to three times higher than wild salmon.[58] A follow-up benefit-risk analysis on salmon consumption balanced the cancer risks with the (n–3) fatty acid advantages of salmon consumption. For this reason, current methods for this type of analysis take into consideration the lipid content of the sample in question. PCBs specifically are lipophilic, so are found in higher concentrations in fattier fish in general,[59] thus the higher level of PCB in the farmed fish is in relation to the higher content of beneficial n–3 and n–6 lipids they contain. They found that recommended levels of (n-3) fatty acid consumption can be achieved eating farmed salmon with acceptable carcinogenic risks, but recommended levels of (n-3) EPA+DHA intake cannot be achieved solely from farmed (or wild) salmon without unacceptable carcinogenic risks.[60] The conclusions of this paper from 2005 were that

"...consumers should not eat farmed fish from Scotland, Norway and eastern Canada more than three times a year; farmed fish from Maine, western Canada and Washington state no more than three to six times a year; and farmed fish from Chile no more than about six times a year. Wild chum salmon can be consumed safely as often as once a week, pink salmon, Sockeye and Coho about twice a month and Chinook just under once a month."[52]

In 2005, Russia banned importing chilled fish from Norway, after samples of Norwegian farmed fish showed high levels of heavy metals. According to the Russian Minister of Agriculture Aleksey Gordeyev, levels of lead in the fish were 10 to 18 times higher than Russian safety standards and cadmium levels were almost four times higher.[61]

Pollutants or toxins introduced by pisciculturists

[edit]In 2006, eight Norwegian salmon producers were caught in unauthorized and unlabeled use of nitrite in smoked and cured salmon. Norway applies EU regulations on food additives, according to which nitrite is allowed as a food additive in certain types of meat, but not fish. Fresh salmon was not affected.[62]

Kurt Oddekalv, leader of the Green Warriors of Norway, argues that the scale of fish farming in Norway is unsustainable. Huge volumes of uneaten feed and fish excrement pollute the seabed, while chemicals designed to fight sea lice find their way into the food chain. He says: "If people knew this, they wouldn’t eat salmon", describing the farmed fish as "the most toxic food in the world".[63] Don Staniford—the former scientist turned activist/investigator and head of a small Global Alliance Against Industrial Aquaculture—agrees, saying that a 10-fold increase in the use of some chemicals was seen in the 2016-2017 timeframe. The use of the toxic drug emamectin is rising fast. The levels of chemicals used to kill sea lice have breached environmental safety limits more than 100 times in the last 10 years.[64]

Impact on wild salmonids

[edit]Farmed salmonids can, and often do, escape from sea cages. If the farmed salmonid is not native, it can compete with native wild species for food and habitat.[65][66] If the farmed salmonid is native, it can interbreed with the wild native salmonids. Such interbreeding can reduce genetic diversity, disease resistance, and adaptability.[67] In 2004, about 500,000 salmon and trout escaped from ocean net pens off Norway. Around Scotland, 600,000 salmon were released during storms.[13] Commercial fishermen targeting wild salmon frequently catch escaped farm salmon. At one stage, in the Faroe Islands, 20 to 40 percent of all fish caught were escaped farm salmon.[68] In 2017, about 263,000 farmed non-native Atlantic salmon escaped from a net in Washington waters in the 2017 Cypress Island Atlantic salmon pen break.[69]

Sea lice, particularly Lepeophtheirus salmonis and various Caligus species, including C. clemensi and C. rogercresseyi, can cause deadly infestations of both farm-grown and wild salmon.[70][71] Sea lice are naturally occurring and abundant ectoparasites which feed on mucus, blood, and skin, and migrate and latch onto the skin of salmon during planktonic nauplii and copepodid larval stages, which can persist for several days.[72][73][74] Large numbers of highly populated, open-net salmon farms can create exceptionally large concentrations of sea lice; when exposed in river estuaries containing large numbers of open-net farms, many young wild salmon are infected, and do not survive as a result.[75][76] Adult salmon may survive otherwise critical numbers of sea lice, but small, thin-skinned juvenile salmon migrating to sea are highly vulnerable. In 2007, mathematical studies of data available from the Pacific coast of Canada indicated the louse-induced mortality of pink salmon in some regions was over 80%.[42] Later that year, in reaction to the 2007 mathematical study mentioned above, Canadian federal fisheries scientists Kenneth Brooks and Simon Jones published a critique titled "Perspectives on Pink Salmon and Sea Lice: Scientific Evidence Fails to Support the Extinction Hypothesis "[77] The time since these studies has shown a general increase in abundance of Pink Salmon in the Broughton Archipelago. Another comment in the scientific literature by Canadian Government Fisheries scientists Brian Riddell and Richard Beamish et al. came to the conclusion that there is no correlation between farmed salmon louse numbers and returns of pink salmon to the Broughton Archipelago. And in relation to the 2007 Krkosek extinction theory: "the data was [sic] used selectively and conclusions do not match with recent observations of returning salmon".[43]

A 2008 meta-analysis of available data shows that salmonid farming reduces the survival of associated wild salmonid populations. This relationship has been shown to hold for Atlantic, steelhead, pink, chum, and coho salmon. The decrease in survival or abundance often exceeds 50%.[78] However, these studies are all correlation analysis and correlation doesn't equal causation, especially when similar salmon declines were occurring in Oregon and California, which have no salmon aquaculture or marine net pens. Independent of the predictions of the failure of salmon runs in Canada indicated by these studies, the wild salmon run in 2010 was a record harvest.[79]

A 2010 study that made the first use of sea lice count and fish production data from all salmon farms on the Broughton Archipelago found no correlation between the farm lice counts and wild salmon survival. The authors conclude that the 2002 stock collapse was not caused by the farm sea lice population: although the farm sea lice population during the out-migration of juvenile pink salmon was greater in 2000 than that of 2001, there was a record salmon returning to spawn in 2001 (from the juveniles in 2000) compared with a 97% collapse in 2002 (from the juveniles in 2001). The authors also note that initial studies had not investigated bacterial and viral causes for the event despite reports of bleeding at the base of the fins, a symptom often associated with infections, but not with sea lice exposure under laboratory conditions. [80]

Wild salmon are anadromous. They spawn inland in fresh water and when young migrate to the ocean where they grow up. Most salmon return to the river where they were born, although some stray to other rivers. Concern exists about of the role of genetic diversity within salmon runs. The resilience of the population depends on some fish being able to survive environmental shocks, such as unusual temperature extremes. The effect of hatchery production on the genetic diversity of salmon is also unclear.[7]

Genetic modification

[edit]Salmon have been genetically modified in laboratories so they can grow faster. A company, Aqua Bounty Farms, has developed a modified Atlantic salmon which grows nearly twice as fast (yielding a fully grown fish at 16–18 months rather than 30), and is more disease resistant, and cold tolerant. It also requires 10% less food. This was achieved using a chinook salmon gene sequence affecting growth hormones, and a promoter sequence from the ocean pout affecting antifreeze production.[81] Normally, salmon produce growth hormones only in the presence of light. The modified salmon does not switch growth hormone production off. The company first submitted the salmon for FDA approval in 1996.[82] In 2015, FDA has approved the AquAdvantage Salmon for commercial production.[83] A concern with transgenic salmon is what might happen if they escape into the wild. One study, in a laboratory setting, found that modified salmon mixed with their wild cohorts were aggressive in competing, but ultimately failed.[84]

Impact on wild predatory species

[edit]Sea cages can attract a variety of wild predators which can sometimes become entangled in associated netting, leading to injury or death. In Tasmania, Australian salmon-farming sea cages have entangled white-bellied sea eagles. This has prompted one company, Huon Aquaculture, to sponsor a bird rehabilitation centre and try more robust netting.[85]

Ecological

[edit]Juvenile farmed Chinook have been shown to have higher rates of predation due to their larger size than wild juveniles upon release into marine environments. Their size correlates with the preferred size of prey for predators like birds, seals, and fish. This may have ecological implications because of the effect on feeding.[86]

Impact on forage fish

[edit]The use of forage fish for fish meal production has been almost a constant for the last 30 years and at the maximum sustainable yield, while the market for fish meal has shifted from chicken, pig, and pet food to aquaculture diets.[16] This market shift at constant production appears an economic decision implying that the development of salmon aquaculture had no impact on forage fish harvest rates.

Fish do not actually produce omega-3 fatty acids, but instead accumulate them from either consuming microalgae that produce these fatty acids, as is the case with forage fish like herring and sardines, or consuming forage fish, as is the case with fatty predatory fish like salmon. To satisfy this requirement, more than 50% of the world fish oil production is fed to farmed salmon.[26]

In addition, salmon require nutritional intakes of protein, which is often supplied in the form of fish meal as the lowest-cost alternative. Consequently, farmed salmon consume more fish than they generate as a final product, though considerably more preferred as food.

Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue and ASC Salmon Standard

[edit]In 2004, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)-USA initiated the Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue, one of several Aquaculture Dialogues.[11] The aim of the dialogues was to produce an environmental and social standard for farmed salmon and other species (12 species currently, as of 2018). Since 2012, the standards elaborated by the multi-stakeholder Dialogues were passed-on to the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) which was created in 2010 to administer and developed them further. The first such standard was the ASC Salmon Standard[87] (June 2012, and revised in 2017 after comprehensive public consultation). The WWF had originally identified what they called "seven key environmental and social impacts", characterised as:

- Benthic impacts and siting: Chemicals and excess nutrients from food and feces associated with salmon farms can disturb the flora and fauna on the ocean bottom (benthos).[88]

- Chemical inputs: Excessive use of chemicals – such as antibiotics, anti-foulants and pesticides – or the use of banned chemicals can have unintended consequences for marine organisms and human health.[89]

- Disease/parasites: Viruses and parasites can transfer between farmed and wild fish, as well as among farms.[90][91]

- Escapes: Escaped farmed salmon can compete with wild fish and interbreed with local wild stocks of the same population, altering the overall pool of genetic diversity.[92]

- Feed: A growing salmon farming business must control and reduce its dependency upon fishmeal and fishoil – a primary ingredient in salmon feed—so as not to put additional pressure on the world's fisheries. Fish caught to make fishmeal and oil currently represent one-third of the global fish harvest.[93]

- Nutrient loading and carrying capacity: Excess food and fish waste in the water have the potential to increase the levels of nutrients in the water. This can cause the growth of algae, which consumes oxygen that is meant for other plant and animal life.[94]

- Social issues: Salmon farming often employs a large number of workers on farms and in processing plants, potentially placing labor practices and worker rights under public scrutiny. Additionally, conflicts can arise among users of the shared coastal environment.

— World Wide Fund for Nature, [11]

Land-raised salmon

[edit]Recirculating aquaculture systems make it possible to farm salmon entirely on land, which as of 2019 is an ongoing initiative in the industry.[95] However, large farmed salmon companies such as Mowi and Cermaq were not investing in such systems beyond the hatchery stage.[96] In the United States, a major investor in the effort was Atlantic Sapphire, which plans to bring salmon raised in Florida to market in 2021.[96][97] Other companies investing in the effort include Nordic Acquafarms[98] and Whole Oceans.[99]

Challenges

[edit]Nephrocalcinosis is an emerging issue in salmon aquaculture with the increased use of recirculating aquaculture systems. One key driver of nephrocalcinosis is exposure to high levels of CO2 in the rearing water.[100]

Species

[edit]Atlantic salmon

[edit]

In their natal streams, Atlantic salmon are considered a prized recreational fish, pursued by avid fly anglers during its annual runs. At one time, the species supported an important commercial fishery and a supplemental food fishery. However, the wild Atlantic salmon fishery is commercially dead; after extensive habitat damage and overfishing, wild fish make up only 0.5% of the Atlantic salmon available in world fish markets. The rest are farmed, predominantly from aquaculture in Chile, Canada, Norway, Russia, the United Kingdom, and Tasmania.[101]

Atlantic salmon is, by far, the species most often chosen for farming. It is easy to handle, grows well in sea cages, commands a high market value, and adapts well to being farmed away from its native habitats.[7]

Adult male and female fish are anesthetized. Eggs and sperm are "stripped", after the fish are cleaned and cloth dried. Sperm and eggs are mixed, washed, and placed into fresh water. Adults recover in flowing, clean, well-aerated water.[102] Some researchers have studied cryopreservation of the eggs.[103]

Fry are generally reared in large freshwater tanks for 12 to 20 months. Once the fish have reached the smolt phase, they are taken out to sea, where they are held for up to two years. During this time, the fish grow and mature in large cages off the coasts of Canada, the United States, or parts of Europe.[101] Generally, cages are made of two nets; inner nets, which wrap around the cages, hold the salmon while outer nets, which are held by floats, keep predators out.[102]

Many Atlantic salmon escape from cages at sea. Those salmon that further breed tend to lessen the genetic diversity of the species leading to lower survival rates, and lower catch rates. On the West Coast of North America, the non-native salmon could be an invasive threat, especially in Alaska and parts of Canada. This could cause them to compete with native salmon for resources. Extensive efforts are underway to prevent escapes and the potential spread of Atlantic salmon in the Pacific and elsewhere.[104] The risk of Atlantic Salmon becoming a legitimate invasive threat on the Pacific Coast of N. America is questionable in light of both Canadian and American governments deliberately introducing this species by the millions for a 100-year period starting in the 1900s. Despite these deliberate attempts to establish this species on the Pacific coast; no established populations have been reported.[105][106]

In 2007, 1,433,708 tonnes of Atlantic salmon were harvested worldwide with a value of $7.58 billion.[107] Ten years later, in 2017, over 2 million tonnes of farmed Atlantic salmon were harvested.[108]

Steelhead

[edit]

In 1989, steelhead were reclassified into the Pacific trout as Oncorhynchus mykiss from the former binominals of Salmo gairdneri (Columbia River redband trout) and S. irideus (coastal rainbow trout). Steelhead are an anadromous form of rainbow trout that migrate between lakes and rivers and the ocean, and are also known as steelhead salmon or ocean trout.

Steelhead are raised in many countries throughout the world. Since the 1950s, production has grown exponentially, particularly in Europe and recently in Chile. Worldwide, in 2007, 604,695 tonnes of farmed steelhead were harvested, with a value of $2.59 billion.[109] The largest producer is Chile. In Chile and Norway, the ocean-cage production of steelhead has expanded to supply export markets. Inland production of rainbow trout to supply domestic markets has increased strongly in countries such as Italy, France, Germany, Denmark, and Spain. Other significant producing countries include the United States, Iran, Germany, and the UK.[109] Rainbow trout, including juvenile steelhead in fresh water, routinely feed on larval, pupal, and adult forms of aquatic insects (typically caddisflies, stoneflies, mayflies, and aquatic dipterana). They also eat fish eggs and adult forms of terrestrial insects (typically ants, beetles, grasshoppers, and crickets) that fall into the water. Other prey include small fish up to one-third of their length, crayfish, shrimp, and other crustaceans. As rainbow trout grow, the proportion of fish consumed increases in most populations. Some lake-dwelling forms may become planktonic feeders. In rivers and streams populated with other salmonid species, rainbow trout eat varied fish eggs, including those of salmon, brown and cutthroat trout, mountain whitefish, and the eggs of other rainbow trout. Rainbows also consume decomposing flesh from carcasses of other fish. Adult steelhead in the ocean feed primarily on other fish, squid, and amphipods.[110] Cultured steelhead are fed a diet formulated to closely resemble their natural diet that includes fish meal, fish oil, vitamins and minerals, and the carotenoid asthaxanthin for pigmentation.

The steelhead is especially susceptible to enteric redmouth disease. Considerable research has been conducted on redmouth disease, as its implications for steelhead farmers are significant. The disease does not affect humans.[111]

Coho salmon

[edit]

The Coho salmon[14] is the state animal of Chiba, Japan.[failed verification]

Coho salmon mature after only one year in the sea, so two separate broodstocks (spawners) are needed, alternating each year.[dubious – discuss] Broodfish are selected from the salmon in the seasites and transferred to freshwater tanks for maturation and spawning.[14]

Worldwide, in 2007, 115,376 tonnes of farmed Coho salmon were harvested with a value of $456 million.[112] Chile, with about 90 percent of world production, is the primary producer with Japan and Canada producing the rest.[14]

Chinook salmon

[edit]

Chinook salmon are the state fish of Oregon, and are known as "king salmon" because of their large size and flavourful flesh. Those from the Copper River in Alaska are particularly known for their color, rich flavor, firm texture, and high omega-3 oil content.[113] Alaska has a long-standing ban on finfish aquaculture that was enacted in 1989. (Alaska Stat. § 16.40.210[114])

Worldwide, in 2007, 11,542 tonnes (1,817,600 st) of farmed Chinook salmon were harvested with a value of $83 million.[115] New Zealand is the largest producer of farmed king salmon, accounting for over half of world production (7,400 tonnes in 2005).[116] Most of the salmon are farmed in the sea (mariculture) using a method sometimes called sea-cage ranching, which takes place in large floating net cages, about 25 m across and 15 m deep, moored to the sea floor in clean, fast-flowing coastal waters. Smolt (young fish) from freshwater hatcheries are transferred to cages containing several thousand salmon, and remain there for the rest of their lives. They are fed fishmeal pellets high in protein and oil.[116]

Chinook salmon are also farmed in net cages placed in freshwater rivers or raceways, using techniques similar to those used for sea-farmed salmon. A unique form of freshwater salmon farming occurs in some hydroelectric canals in New Zealand. A site in Tekapo, fed by fast, cold waters from the Southern Alps, is the highest salmon farm in the world, 677 m (2,221 ft) above sea level.[117]

Before they are killed, cage salmon are sometimes anaesthetised with a herbal extract. They are then spiked in the brain. The heart beats for a time as the animal is bled from its sliced gills. This method of relaxing the salmon when it is killed produces firm, long-keeping flesh.[116] Lack of disease in wild populations and low stocking densities used in the cages means that New Zealand salmon farmers do not use antibiotics and chemicals that are often needed elsewhere.[118]

Timeline

[edit]- 1527: The life history of the Atlantic salmon is described by Hector Boece of the University of Aberdeen, Scotland.[81]

- 1763: Fertilization trials for Atlantic salmon take place in Germany. Later biologists refined these in Scotland and France.[81]

- 1854: Salmon spawing beds and rearing ponds built along the bank of a river by the Dohulla Fishery, Ballyconneely, Ireland.[119]

- 1864: Hatchery raised Atlantic salmon fry were released in the River Plenty, Tasmania in a failed attempt to establish a population in Australia[120]

- 1892: Hatchery raised Atlantic salmon fry were released in the Umkomass river in South Africa in a failed attempt to establish a population in Africa.[121]

- Late 19th century: Salmon hatcheries are used in Europe, North America, and Japan to enhance wild populations.

- 1961: Hatchery raised Atlantic salmon fry were released in the rivers of the Falkland Islands in a failed attempt to establish a population in the South Atlantic.[122]

- Late 1960s: First salmon farms established in Norway and Scotland.

- 1970: Hatchery raised Atlantic salmon fry were released in the rivers of the Kerguelen Islands in a failed attempt to establish a population in the Indian Ocean.[123]

- Early 1970s: Salmon farms established in North America.

- 1973: Rainbow trout was first bred in Thailand on Doi Inthanon, the highest mountain in Thailand, as part of the Royal Project, an initiative of King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX).[124]

- 1975: Gyrodactylus, a small monogenean parasite, spreads from Norwegian hatcheries to wild salmon, probably by means of fishing gear, and devastates some wild salmon populations.[38]

- Late 1970s: Salmon farms established in Chile and New Zealand.

- 1984: Infectious salmon anemia, a viral disease, is discovered in a Norwegian salmon hatchery. Eighty percent of the involved fish die.

- 1985: Salmon farms established in Australia.

- 1987: First reports of escaped Atlantic salmon being caught in wild Pacific salmon fisheries.

- 1988: A storm hits the Faroe Islands releasing millions of Atlantic salmon.

- 1989: Furunculosis, a bacterial disease, spreads through Norwegian salmon farms and wild salmon.

- 1996: World farmed salmon production exceeds wild salmon harvest.

- 2007: A 10-square-mile (26 km2) swarm of Pelagia noctiluca jellyfish wipes out a 100,000 fish salmon farm in Northern Ireland.[125]

- 2019: The first salmon fish farm in the Middle East is established in the United Arab Emirates.[126]

- 2021: Open-net salmon farming is banned in Tierra del Fuego, Argentina.[127]

In popular culture

[edit]- Chapter 14 of Paul Torday's 2007 novel Salmon Fishing in the Yemen includes a description of a visit to the "McSalmon Aqua Farms" where salmon are raised caged in a sea loch in Scotland.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Based on data sourced from the relevant FAO Species Fact Sheets

- ^ "Fish Farming Information and Resources". farms.com. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ Joseph John Charbonneau; James Caudill (September 2010). "Conserving America's Fisheries-An Assessment of Economic Contributions from Fisheries and Aquatic Resource Conservation" (PDF). US Fish and Wildlife Service. p. 20. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ^ "Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme Salmo trutta". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ^ "Responsible Sourcing Guide: Farmed Atlantic Salmon" (PDF). Seafish. 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ "Commercial Fisheries". Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ^ a b c Knapp, Gunnar; Roheim, Cathy A.; Anderson, James L. (January 2007). The Great Salmon Run: Competition Between Wild And Farmed Salmon (PDF) (Report). World Wildlife Fund. ISBN 978-0-89164-175-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ^ "Incubation Biology". METRO EAST ANGLERS. Archived from the original on 2018-08-16. Retrieved 2016-03-27.

- ^ a b "Sea Lice and Salmon: Elevating the dialogue on the farmed-wild salmon story" (PDF). Watershed Watch Salmon Society. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ^ FAO (2008). "The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2008" (PDF). Rome: FAO. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-03-12.

- ^ a b c "Farmed Seafood". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on 2015-01-23. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ^ "B.C. Supreme Court upholds right of anti-salmon farm activist to make defamatory remarks". Postmedia Network Inc. VANCOUVER SUN. 28 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "It's all about salmon-Salmon Aquaculture" (PDF). Seafood Choices Alliance. Spring 2005. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ^ a b c d e f FAO: Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme: Oncorhynchus kisutch (Walbaum, 1792) Rome. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ^ Naylor R. L. (2005) "Search for Sustainable Solutions in Salmon Aquaculture" Stanford University.

- ^ a b Shepherd, Jonathan; Jackson, Andrew and Mittaine, Jean-Francois (July 4, 2007) Fishmeal industry overview. International Fishmeal and Fish Oil Organisation.

- ^ Durham, Sharon (2010-10-13). "Alternative Fish Feeds Use Less Fishmeal and Fish Oils". USDA Agricultural Research Service. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ^ Avant, Sandra (2014-07-14). "Process Turns Barley into High-protein Fish Food". USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ^ Merrit, Mike (13 January 2013) Sea-change as farm grows fish on land The Scotsman, Retrieved 22 January 2013

- ^ a b von Münchow, Otto (5 June 2019). "Gir Hardanger-laksen omega-3 fra alger importert fra Nebraska". Tu.no (in Norwegian). Teknisk Ukeblad.

- ^ Kadir Alsagoff, Syed A.; Clonts, Howard A.; Jolly, Curtis M. (1990). "An integrated poultry, multi-species aquaculture for Malaysian rice farmers: A mixed integer programming approach". Agricultural Systems. 32 (3): 207–231. Bibcode:1990AgSys..32..207K. doi:10.1016/0308-521X(90)90002-8.

- ^ Bell, J.G.; Pratoomyot, J.; Strachan, F.; Henderson, R.J.; Fontanillas, R.; Hebard, A.; Guy, D.R.; Hunter, D.; Tocher, D.R. (2010). "Growth, flesh adiposity and fatty acid composition of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) families with contrasting flesh adiposity: Effects of replacement of dietary fish oil with vegetable oils". Aquaculture. 306 (1–4): 225–232. Bibcode:2010Aquac.306..225B. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2010.05.021. hdl:1893/2421.

- ^ Naylor, Rosamond L. (1998). "Nature's Subsidies to Shrimp and Salmon Farming" (PDF). Science. 282 (5390): 883–884. doi:10.1126/science.282.5390.883. S2CID 129814837. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26.

- ^ "Cargill, an intensely private firm, sheds light on the food chain". The Economist. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ "CARGILL AQUA NUTRITION SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2016" (PDF). cargill.com. p. 20. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ a b FAO (2008), Fish oil, p. 58

- ^ "Farmed fish: a major provider or a major consumer of omega-3 oils?". GLOBEFISH. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Pigments in Salmon Aquaculture: How to Grow a Salmon-coloured Salmon". seafoodmonitor.com. Archived from the original on 2004-09-02. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

Astaxanthin (3,3'-hydroxy-β,β-carotene-4,4'-dione) is a carotenoid pigment, one of a large group of organic molecules related to vitamins and widely found in plants. In addition to providing red, orange, and yellow colours to various plant parts and playing a role in photosynthesis, carotenoids are powerful antioxidants, and some (notably various forms of carotene) are essential precursors to vitamin A synthesis in animals.

- ^ Modern Salmon Harvest. The Fishery and Aquaculture Industry Research Fund (2010)

- ^ FAO: Species fact sheets Rome.

- ^ FAO: Species Fact Sheets, Salmo salar

- ^ Dietary Guidelines. health.gov. Retrieved on 2016-10-26.

- ^ "Meat and Alternatives - Canada's Food Guide". Health Canada. 2012-11-19. Archived from the original on 2018-10-28.

- ^ Pirquet, K. T. (May/June 2010) "Follow the Money", Aquaculture North America, vol 16

- ^ Charron, Bertrand (April 2014). "Of Fairness… Seafood Watch & Farmed Salmon". www.seafoodintelligence.com.

- ^ Charron, Bertrand (May 2012). "Alaska salmon: ASMI vs. MSC?". Seafood Intelligence.

- ^ "2015 Alaska Preliminary Commercial Salmon Harvest and Exvessel Values". adfg.alaska.gov. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. October 16, 2015.

- ^ a b Stead, Selina M.; Laird, Lindsay (14 January 2002). The Handbook of Salmon Farming. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 348–. ISBN 978-1-85233-119-1.

- ^ "New Brunswick to help Chile beat disease". FIS. Fish Information and Services. 2008-12-12. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11.

- ^ Fact Sheet – Atlantic Salmon Aquaculture Research Archived 2010-12-29 at the Wayback Machine Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Scientific Evidence of Sea Lice from Fishfarms Seriously Harming Wild Stocks. saveourskeenasalmon.org

- ^ a b Krkosek, M.; Ford, J. S.; Morton, A.; Lele, S.; Myers, R. A.; Lewis, M. A. (2007). "Declining Wild Salmon Populations in Relation to Parasites from Farm Salmon". Science. 318 (5857): 1772–5. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1772K. doi:10.1126/science.1148744. PMID 18079401. S2CID 86544687.

- ^ a b Riddell, B. E.; Beamish, R. J.; Richards, L. J.; Candy, J. R. (2008). "Comment on "Declining Wild Salmon Populations in Relation to Parasites from Farm Salmon"". Science. 322 (5909): 1790. Bibcode:2008Sci...322.1790R. doi:10.1126/science.1156341. PMID 19095926. S2CID 7901971.

- ^ Cleaner-fish keep salmon healthy by eating lice. Bbc.com (14 August 2015). Retrieved on 2016-10-26.

- ^ Integrated Sea Lice Management Strategies – Scottish Salmon Producers' Organisation Archived 2018-06-23 at the Wayback Machine. Scottishsalmon.co.uk (2013-11-23). Retrieved on 2016-10-26.

- ^ Sarah Butler (2017-01-13). "Salmon retail prices set to leap owing to infestations of sea lice". The Guardian. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Gwynn Guilford (22 Jan 2017). "The gross reason you'll be paying a lot more for salmon this year". Quartz. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Sarah Knapton (12 August 2017). "Salmon farming has done 'enormous harm' to fish and environment, warns Jeremy Paxman". The Telegraph.

- ^ Dumiak, Michael. "Lice-Hunting Underwater Drone Protects Salmon With Lasers". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- ^ Munson, A. Douglas; Elliott, Diane G.; Johnson, Keith (2010). "Management of Bacterial Kidney Disease in Chinook Salmon Hatcheries Based on Broodstock Testing by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay: A Multiyear Study". North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 30 (4): 940–955. Bibcode:2010NAJFM..30..940M. doi:10.1577/M09-044.1.

- ^ Bruno, D. W. (1986). "Changes in serum parameters of rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri Richardson, and Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., infected with Renibacterium salmoninarum". Journal of Fish Diseases. 9 (3): 205–211. Bibcode:1986JFDis...9..205B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2761.1986.tb01005.x.

- ^ a b Lang S. S. (2005) "Stick to wild salmon unless heart disease is a risk factor, risk/benefit analysis of farmed and wild fish shows" Chronicle Online, Cornell University.

- ^ Fish and Seafood Survey – Environmental Contaminants – Food Safety – Health Canada. Hc-sc.gc.ca (2007-03-26). Retrieved on 2016-10-26.

- ^ "Update of the monitoring of levels of dioxins and PCBs in food and feed". EFSA Journal. 10 (7): 2832. 2012. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2832.

- ^ Hites, R. A.; Foran, J. A.; Carpenter, D. O.; Hamilton, M. C.; Knuth, B. A.; Schwager, S. J. (2004). "Global Assessment of Organic Contaminants in Farmed Salmon". Science. 303 (5655): 226–9. Bibcode:2004Sci...303..226H. doi:10.1126/science.1091447. PMID 14716013. S2CID 24058620.

- ^ Santerre, Charles R. (2008). "Balancing the risks and benefits of fish for sensitive populations" (PDF). Journal of Foodservice. 19 (4): 205–212. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.570.4751. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0159.2008.00111.x.

- ^ Schwager, SJ (2005-05-01). "Risk-based consumption advice for farmed Atlantic and wild Pacific Salmon contaminated with dioxins and dioxin-like compounds". Environmental Health Perspectives. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07.

- ^ Hamilton, M. Coreen; Hites, Ronald A.; Schwager, Steven J.; Foran, Jeffery A.; Knuth, Barbara A.; Carpenter, David O. (2005). "Lipid Composition and Contaminants in Farmed and Wild Salmon". Environmental Science & Technology. 39 (22): 8622–8629. Bibcode:2005EnST...39.8622H. doi:10.1021/es050898y. PMID 16323755.

- ^ Elskus, Adria A.; Collier, Tracy K.; Monosson, Emily (2005). "Ch. 4 Interactions between lipids and persistent organic pollutants in fish". In Moon, T.W.; Mommsen, T.P. (eds.). Environmental Toxicology. Elsevier. pp. 119–. doi:10.1016/S1873-0140(05)80007-4. ISBN 978-0-08-045873-1.

- ^ Foran, J. A.; Good, D. H.; Carpenter, D. O.; Hamilton, M. C.; Knuth, B. A.; Schwager, S. J. (2005). "Quantitative analysis of the benefits and risks of consuming farmed and wild salmon". The Journal of Nutrition. 135 (11): 2639–43. doi:10.1093/jn/135.11.2639. PMID 16251623.

- ^ "GAIN Report: Russia Bans Norwegian Fish" (PDF). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 2005-12-29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-01.

- ^ "Hard Times for Norwegian Salmon (2006)" (PDF).

- ^ Castle, Stephen (November 6, 2017). "As wild salmon decline, Norway pressures its giant fish farms". New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ Vidal, John (2017-01-01). "Salmon farming in crisis: 'We are seeing a chemical arms race in the seas'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ Fleming, I. A.; Hindar, K; Mjølnerød, I. B.; Jonsson, B; Balstad, T; Lamberg, A (2000). "Lifetime success and interactions of farm salmon invading a native population". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 267 (1452): 1517–1523. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1173. PMC 1690700. PMID 11007327.

- ^ Volpe, John P.; Taylor, Eric B.; Rimmer, David W.; Glickman, Barry W. (2000). "Evidence of Natural Reproduction of Aquaculture-Escaped Atlantic Salmon in a Coastal British Columbia River". Conservation Biology. 14 (3): 899–903. Bibcode:2000ConBi..14..899V. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99194.x. S2CID 86641677.

- ^ Gardner J. and D. L. Peterson (2003) "Making sense of the aquaculture debate: analysis of the issues related to netcage salmon farming and wild salmon in British Columbia", Pacific Fisheries Resource Conservation Council, Vancouver, BC.

- ^ Hansen L. P., J. A. Jacobsen and R. A. Lund (1999). "The incidence of escaped farmed Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., in the Faroese fishery and estimates of catches of wild salmon". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 56 (2): 200–206. Bibcode:1999ICJMS..56..200H. doi:10.1006/jmsc.1998.0437.

- ^ Lee, Kessina; Windrope, Amy; Murphy, Kyle (Jan 2018). 2017 Cypress Island Atlantic Salmon Net Pen Failure: An Investigation and Review (PDF) (Report). Washington State Department of Natural Resources. pp. 1–120.

- ^ Sea Lice and Salmon: Elevating the dialogue on the farmed-wild salmon story Archived 2010-12-14 at the Wayback Machine Watershed Watch Salmon Society, 2004.

- ^ Bravo, S. (2003). "Sea lice in Chilean salmon farms". Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 23: 197–200.

- ^ Morton, A.; R. Routledge; C. Peet; A. Ladwig (2004). "Sea lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) infection rates on juvenile pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) and chum (Oncorhynchus keta) salmon in the nearshore marine environment of British Columbia, Canada". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 61 (2): 147–157. doi:10.1139/f04-016.

- ^ Peet, C. R. (2007). Interactions between sea lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis and Caligus clemensii), juvenile salmon (Oncorhynchus keta and Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) and salmon farms in British Columbia. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

- ^ Krkošek, M.; A. Gottesfeld; B. Proctor; D. Rolston; C. Carr-Harris; M.A. Lewis (2007). "Effects of host migration, diversity and aquaculture on sea lice threats to Pacific salmon populations". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1629): 3141–9. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1122. PMC 2293942. PMID 17939989.

- ^ Morton, A.; R. Routledge; M. Krkošek (2008). "Sea Louse Infestation in Wild Juvenile Salmon and Pacific Herring Associated with Fish Farms off the East-Central Coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia" (PDF). North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 28 (2): 523–532. Bibcode:2008NAJFM..28..523M. doi:10.1577/M07-042.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-29. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- ^ Krkošek, M.; M.A. Lewis; A. Morton; L.N. Frazer; J.P. Volpe (2006). "Epizootics of wild fish induced by farm fish". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (42): 15506–10. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603525103. PMC 1591297. PMID 17021017.

- ^ Brooks, Kenneth M.; Jones, Simon R. M. (2008). "Perspectives on Pink Salmon and Sea Lice: Scientific Evidence Fails to Support the Extinction Hypothesis". Reviews in Fisheries Science. 16 (4): 403–412. Bibcode:2008RvFS...16..403B. doi:10.1080/10641260801937131. S2CID 55689510.

- ^ Ford, Jennifer S; Myers, Ransom A (2008). "A Global Assessment of Salmon Aquaculture Impacts on Wild Salmonids". PLOS Biology. 6 (2): e33. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060033. PMC 2235905. PMID 18271629.

- ^ Larkin, Kate (3 September 2010). "Canada sees shock salmon glut". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2010.449.

- ^ Marty, G. D.; Saksida, S. M.; Quinn, T. J. (2010). "Relationship of farm salmon, sea lice, and wild salmon populations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (52): 22599–604. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10722599M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009573108. PMC 3012511. PMID 21149706.

- ^ a b c Knapp, G; Roheim, CA; Anderson, JA (2007). Chapter 5: The World Salmon Farming Industry (PDF). University of Alaska Anchorage. ISBN 978-0-89164-175-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-22.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Fast Growing GM Salmon Swims Close to US Markets". The Fish Site. 2009-02-11. Archived from the original on 2010-02-01.

- ^ "Genetically Engineered Animals - AquAdvantage Salmon". www.fda.gov. United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ^ Devlin, R. H.; d'Andrade, M.; Uh, M.; Biagi, C. A. (2004). "Population effects of growth hormone transgenic coho salmon depend on food availability and genotype by environment interactions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (25): 9303–8. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.9303D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0400023101. PMC 438972. PMID 15192145.

- ^ "Fish farmer sponsors new aviary for injured eagles". ABC News. 2014-06-16. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- ^ Nelson, Benjamin W.; Shelton, Andrew O.; Anderson, Joseph H.; Ford, Michael J.; Ward, Eric J. (2019). "Ecological implications of changing hatchery practices for Chinook salmon in the Salish Sea". Ecosphere. 10 (11). Bibcode:2019Ecosp..10E2922N. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2922.

- ^ Aquaculture Stewardship Council, (ASC) (2017). ASC Salmon Standard (V1.1) (PDF). ASC.

- ^ "Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue: Benthic impacts report" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-05.

- ^ "Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue: Chemical report" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-29.

- ^ "Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue: Disease report" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-05.

- ^ "Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue: Sealice report" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-05.

- ^ "Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue: Escapes report" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-20.

- ^ "Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue: Feed report" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-05.

- ^ "Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue: Nutrient loading" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-29.

- ^ Shore, Randy (2018-10-20). "Growing pains as companies try to move fish farms from ocean to land". Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ a b "Report: Does 'big salmon' know something RAS startups don't?". Undercurrent News. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "Will Your Next Salmon Come from a Massive Land Tank in Florida?". www.politico.com. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- ^ "Nordic Aquafarms pursues US market before Maine salmon plant complete". Undercurrent News. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "Land-based salmon farmer Whole Oceans eyeing west coast". IntraFish. 2019-03-04. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ Fivelstad, Sveinung; Hosfeld, Camilla Diesen; Medhus, Reidunn Agathe; Olsen, Anne Berit; Kvamme, Kristin (2018). "Growth and nephrocalcinosis for Atlantic salmon ( Salmo salar L.) post-smolt exposed to elevated carbon dioxide partial pressures". Aquaculture. 482: 83–89. Bibcode:2018Aquac.482...83F. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2017.09.012.

- ^ a b Heen K. (1993). Salmon Aquaculture. Halstead Press.

- ^ a b Sedgwick, S. (1988). Salmon Farming Handbook. Fishing News Books LTD.

- ^ Bromage, N. (1995). Broodstock Management and Egg and Larval Quality. Blackwell Science.

- ^ Mills D. (1989). Ecology and Management of Atlantic Salmon. Springer-Verlag.

- ^ Nash, Colin E.; Waknitz, F.William (2003). "Interactions of Atlantic salmon in the Pacific Northwest". Fisheries Research. 62 (3): 237–254. doi:10.1016/S0165-7836(03)00063-8. ISSN 0165-7836.

- ^ MacCrimmon, Hugh R; Gots, Barra L (1979). World Distribution of Atlantic Salmon, Salmo salar. NRC Research Press.

- ^ FAO: Species Fact Sheets: Salmo salar (Linnaeus, 1758) Rome. Accessed 9 May 2009.

- ^ Integrated Annual Report 2017 - Leading the Blue Revolution (PDF). Marine Harvest. 2018. p. 246. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-22.

- ^ a b "Species Fact Sheets: Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum, 1792)". Rome: FAO. Archived from the original on 2018-07-01. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "BC Fish Facts-Steelhead" (PDF). British Columbia Ministry of Fisheries. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-18. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ Bullock, G. L. and Cipriano, R. C. (1990) LSC – Fish Disease Leaflet 82. Enteric Redmouth Disease of Salmonids. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ^ FAO: Species Fact Sheets: Oncorhynchus kisutch (Walbaum, 1792) Rome. Accessed 9 May 2009.

- ^ Foodies...FREAK! Copper River Salmon Arrive Archived 2010-02-14 at the Wayback Machine. Seattlest (2006-05-16). Retrieved on 2016-10-26.

- ^ "Alaska Statutes - Section 16.40.210.: Finfish farming prohibited". Findlaw. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- ^ FAO: Species Fact Sheets: Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum, 1792) Rome. Accessed 9 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Marine Aquaculture MFish. Updated 16 November 2007.

- ^ Wassilieff, Maggy Aquaculture: Salmon Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 September 2007

- ^ Aquaculture in New Zealand aquaculture.govt.nz

- ^ "History of Ballyconneely from earliest settlers to the present day". connemara.net. Archived from the original on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ Newton, Chris (2013). "The Strange Case of the Disappearing Salmon". The Trout's Tale – The Fish That Conquered an Empire. Ellesmere, Shropshire: Medlar Press. pp. 57–66. ISBN 978-1-907110-44-3.

- ^ Newton, Chris (2013). "Scotland with Lions". The Trout's Tale – The Fish That Conquered an Empire. Ellesmere, Shropshire: Medlar Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-907110-44-3.

- ^ Newton, Chris (2013). "Falklands' Silver". The Trout's Tale – The Fish That Conquered an Empire. Ellesmere, Shropshire: Medlar Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-907110-44-3.

- ^ Newton, Chris (2013). "The Monsters of Kerguelen". The Trout's Tale – The Fish That Conquered an Empire. Ellesmere, Shropshire: Medlar Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-907110-44-3.

- ^ ""ปลาเทราต์" เพาะเลี้ยงแห่งแรกในไทยที่ "โครงการหลวงอินทนนท์"" ["Trout" first cultivated in Thailand at “Inthanon Royal Project”]. ASTV Manager (in Thai). 2017-10-26. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ "Billions of jellyfish wipe out salmon farm". NBC News. November 21, 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ^ The National (29 March 2019). "Desert salmon farming becomes reality for Dubai-based company".

- ^ Cockburn, Harry (8 July 2021). "Argentina becomes first country to ban open-net salmon farming due to impact on environment". The Independent.

Further reading

[edit]- Beveridge, Malcolm (1984) Cage and Pen fish farming: Carrying capacity models and environmental impact FAO Fisheries technical paper 255, Rome. ISBN 92-5-102163-5

- Bjorndal, Trond (1990) The Economics of Salmon Aquaculture. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-632-02704-0

- Coimbra, João (1 January 2001). Modern Aquaculture in the Coastal Zone: Lessons and Opportunities. IOS Press. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-0-9673355-6-8.

- Harris, Graeme; Milner, Nigel (12 March 2007). Sea Trout: Biology, Conservation and Management. Wiley. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-4051-2991-6.

- Heen K., Monahan R. L. and Utter F. (1993) Salmon Aquaculture, Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-85238-204-2

- Knapp G., Roheim C. A. and Anderson J. A. (2007) The Great Salmon Run: Competition between Wild and Farmed Salmon Report of the Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage. ISBN 0-89164-175-0.

- Lustig, B. Andrew; Brody, Baruch A.; McKenny, Gerald P. (1 November 2008). Altering Nature: Volume II: Religion, Biotechnology, and Public Policy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 321–. ISBN 978-1-4020-6923-9.

- Pomeroy R., Bravo-Ureta B. E., Solis D. and Johnston R. J. (2008) "Bioeconomic modelling and salmon aquaculture: an overview of the literature" International Journal of Environment and Pollution 33(4) 485–500.

- Quinn, Thomas P. (2005). The Behavior and Ecology of Pacific Salmon and Trout. American Fisheries Society. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-295-98457-5.

- British Columbia Salmon Farming Association, "Did you Know" [1]

External links

[edit]- BC Salmon Farmers Association Archived 2011-04-23 at the Wayback Machine – Trade association representing the salmon aquaculture industry in British Columbia, Canada.

- CAIA – Canadian Industry Aquaculture Association Canadian association representing all salmon farms in Canada.

- Creating Standards for Responsibly Farmed Salmon – Salmon Aquaculture Dialogue, a "multi-stakeholder roundtable" led by the World Wildlife Fund

- Watershed Watch Salmon Society

- Positive Aquaculture Awareness Independent association which promotes salmon farming in British Columbia, Canada.

- What about this fish? – Video extract from Harvest of Fear.

Aquaculture of salmonids

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Origins and Early Practices

The origins of salmonid aquaculture trace to artificial fertilization experiments in Europe during the second half of the eighteenth century, aimed at propagating salmon and trout to replenish declining wild stocks depleted by overfishing and habitat loss.[11] These initial practices involved collecting ripe eggs and milt from wild fish during spawning runs, manually fertilizing them in controlled settings, and incubating the embryos in simple troughs or gravel beds mimicking natural redds, with survival rates often low due to fungal infections and poor water quality management.[11] By the mid-nineteenth century, dedicated hatcheries emerged, marking the transition from ad hoc propagation to systematic rearing. In 1852, the first salmon hatchery was established on the Rhine River in Europe, focusing on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) egg production and distribution to restock rivers.[12] French efforts followed, with the National Hatchery at Huningue producing and shipping approximately 40 million salmon eggs between 1852 and 1870 for river enhancement programs.[13] Early rearing techniques emphasized freshwater raceways or ponds for fry and fingerlings, fed natural diets like ground liver or insects, before release into wild systems; full grow-out to market size remained impractical due to high mortality in smolt-to-adult phases and lack of sea-cage technology.[14] In North America, trout hatcheries pioneered commercial-scale propagation, beginning with Seth Green's establishment of the first successful U.S. fish hatchery in 1864 at Caledonia, New York, initially targeting brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) and later brown trout (Salmo trutta).[15] Green's methods improved upon European techniques by using artificial incubation boxes with flowing spring water to achieve higher hatch rates—up to 80% in controlled trials—and emphasized selective breeding for faster growth, laying groundwork for domestication.[16] The first public salmon hatchery in the United States opened in 1871 at Craig's Pond Brook, Maine, funded by private and state interests to propagate Atlantic salmon for coastal fisheries restoration.[17] These operations prioritized stocking over harvest, producing millions of juveniles annually by the 1880s, though genetic dilution from hatchery releases later raised concerns about wild population fitness.[18] Early practices across regions shared common challenges, including disease outbreaks from dense rearing and nutritional deficiencies, addressed rudimentary through oxygenation via waterfalls or weirs and culling of weak individuals.[19] By the late nineteenth century, over 18 hatcheries operated in Scotland alone, distributing eyed eggs and fry to support anadromous salmon runs, while U.S. federal involvement via the 1871 U.S. Fish Commission scaled production for inland trout stocking.[20] These foundational efforts, driven by conservation imperatives rather than profit, evolved into modern aquaculture only after mid-twentieth-century advances in containment and feeds.[21]Commercial Expansion (1970s–1990s)

Commercial expansion of salmonid aquaculture began in the 1970s, primarily in Norway and Scotland, where sea-cage systems enabled the rearing of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) at scale. In Norway, production started from a baseline of approximately 500 metric tons in 1970, driven by government subsidies, advancements in floating net-pen technology pioneered in the late 1950s, and the development of dry pelleted feeds that improved growth efficiency and reduced reliance on raw fish.[22][23] By 1980, Norwegian output had reached 8,000 metric tons, supported by over 300 small-scale farms entering the sector amid declining wild stocks and rising demand for protein.[22] In Scotland, the first commercial harvest occurred in 1971, building on earlier freshwater trout farming experiments, with production scaling through similar cage innovations and access to cold coastal waters.[20] The 1980s marked rapid proliferation, fueled by export-oriented growth and biological improvements like selective breeding for faster growth and disease resistance. Norwegian production surged to 15,500 metric tons by 1983 and continued expanding, while Scotland's output grew from modest levels in the late 1970s to contribute significantly to European supply by decade's end.[23] Globally, farmed salmon volumes overtook certain wild Pacific salmon harvests by the mid-1980s, with new operations emerging in Chile (late 1970s), Canada, and the Faroe Islands, often transferring Norwegian expertise.[11] This era saw farm numbers peak, with Norway alone hosting over 500 sites by the mid-1980s, though high densities began revealing challenges like sea lice and bacterial infections, prompting early veterinary interventions.[24] Into the 1990s, production consolidated amid overcapacity and price volatility, yet overall volumes climbed, reaching 170,000 metric tons in Norway by 1990 and contributing to global farmed salmon exceeding 400,000 metric tons by the decade's close.[22] Regulatory reforms in Norway, including license reductions and biomass limits post-1989 crisis, shifted the industry toward larger, more efficient operations, enhancing sustainability and export competitiveness to markets in Europe and North America.[25] Scotland's harvest approached 115,000 metric tons by 1998, underscoring the North Atlantic's dominance, while Pacific species like coho and chinook saw limited but growing culturing in the Americas.[20] This period's expansion was underpinned by causal factors such as technological scalability and market incentives, though it also highlighted vulnerabilities to density-related pathologies absent in wild fisheries.[26]Modern Milestones and Global Growth (2000s–Present)

Global production of farmed Atlantic salmon, the dominant salmonid in aquaculture, expanded substantially from the 2000s onward, reaching approximately 2.7 million metric tons by 2023, more than double the combined farmed and wild salmon output of 1.89 million metric tons recorded in 2000.[27][28] This growth was driven primarily by Norway, which accounted for over half of worldwide farmed salmon output, followed by Chile, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the Faroe Islands.[29] Industry consolidation played a key role, with leading firms like Mowi, SalMar, and Cermaq achieving multi-national scale through organic expansion and acquisitions, enabling efficiencies in scale and technology deployment.[28] A pivotal challenge in the 2000s was the infectious salmon anemia (ISA) virus outbreak in Chile starting in 2007, which halved production and prompted regulatory reforms including fallowing periods, site rotations, and improved biosecurity, facilitating a rebound to pre-crisis levels by the mid-2010s.[30] Concurrently, advancements in feed formulation reduced reliance on marine ingredients; Norwegian salmon feeds, for instance, decreased marine protein content from 33.5% in 2000 to 14.5% by 2016 through incorporation of plant-based alternatives and novel proteins, mitigating pressure on wild fisheries while maintaining growth rates.[31] Disease management innovations, such as vaccines against sea lice and bacterial infections, alongside selective breeding programs enhancing disease resistance and feed conversion efficiency, further supported productivity gains across major producing regions.[32] In the 2010s and 2020s, technological shifts included the adoption of larger ocean pens, automated feeding systems with real-time monitoring via cameras and sensors, and extended freshwater post-smolt rearing to minimize early marine exposure to pathogens.[33] Emerging closed-containment systems, such as recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) and semi-closed pens, gained traction amid environmental pressures, with Canada mandating a transition away from open net-pens in British Columbia by 2029 to address concerns over escapes, waste, and interactions with wild stocks.[34] These developments, coupled with market demand for premium protein, positioned salmonid aquaculture as a cornerstone of global seafood supply, comprising about 80% of total salmon availability despite ongoing debates over ecological impacts.[35]Production Methods

Hatchery and Broodstock Management