Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Slavonia

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| History of Slavonia |

|---|

|

| History of Croatia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

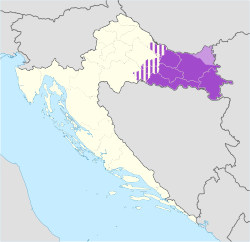

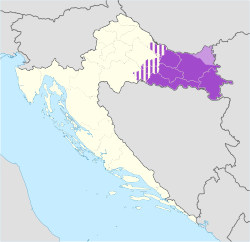

Slavonia (/sləˈvoʊniə/; Croatian: Slavonija[a]) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria, one of the four historical regions of Croatia.[1] Located in the Pannonian Plain and taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with five Croatian counties: Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Baranja, Požega-Slavonia, Virovitica-Podravina, and Vukovar-Syrmia, although the territory of the counties includes Baranya, and the definition of the western extent of Slavonia as a region varies. The counties cover 12,556 square kilometres (4,848 square miles) or 22.2% of Croatia, inhabited by 806,192—18.8% of Croatia's population. The largest city in the region is Osijek, followed by Slavonski Brod and Vinkovci.

Slavonia is located in the Pannonian Basin, largely bordered by the Danube, Drava, and Sava rivers. In the west, the region consists of the Sava and Drava valleys and the mountains surrounding the Požega Valley, and plains in the east. Slavonia enjoys a moderate continental climate with relatively low precipitation.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, which ruled the area of modern-day Slavonia until the 5th century, Ostrogoths and Lombards controlled the area before the arrival of Avars and Slavs. The Slavs in Lower Pannonia established a principality in the 7th century, which was later incorporated into the Kingdom of Croatia; after its decline, the kingdom was ruled through a personal union with Hungary. In the Kingdom of Hungary, the Ban of Slavonia was the King's governor of these lands, at various times distinct from the Ban of Croatia.

The Ottoman conquest of Slavonia took place in the 16th century. At the turn of the 18th century, after the Great Turkish War of 1683–1699, the Treaty of Karlowitz transferred Kingdom of Slavonia to the Habsburgs. After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Slavonia became part of the Hungarian part of the realm, and a year later it became part of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. In 1918, when Austria-Hungary dissolved, Slavonia became a part of the short-lived State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs which in turn became a part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later renamed Yugoslavia. During the Croatian War of Independence of 1991–1995, Slavonia saw fierce fighting, including the 1991 Battle of Vukovar.

The economy of Slavonia is largely based on processing industry, trade, transport, and civil engineering. Agriculture is a significant component of its economy: Slavonia contains 45% of Croatia's agricultural land and accounts for a significant proportion of Croatia's livestock farming and production of permanent crops. The gross domestic product (GDP) of the five counties of Slavonia is worth 6,454 million euro or 8,005 euro per capita, 27.5% below national average. The GDP of the five counties represents 13.6% of Croatia's GDP.

The cultural heritage of Slavonia represents a blend of historical influences, especially those from the end of the 17th century, when Slavonia started recovering from the Ottoman wars, and its traditional culture. Slavonia contributed to the culture of Croatia through art, writers, poets, sculptors, and art patronage. In traditional music, Slavonia comprises a distinct region of Croatia, and the traditional culture is preserved through folklore festivals, with prominence given to tamburica music and bećarac, a form of traditional song, recognized as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO. The cuisine of Slavonia reflects diverse influences—a blend of traditional and foreign elements. Slavonia is one of Croatia's winemaking areas, with Erdut, Ilok and Kutjevo recognized as centres of wine production.

History

[edit]

The name Slavonia originated in the Early Middle Ages. The area was named after the Slavs who settled there and called themselves *Slověne. The root *Slověn- appeared in various dialects of languages spoken by people inhabiting the area west of the Sutla river, as well as between the Sava and Drava rivers—South Slavs living in the area of the former Illyricum. The area bounded by those rivers was called *Slověnьje in the Proto-Slavic language. The word subsequently evolved to its various present forms in the Slavic languages, and other languages adopted the term.[2]

Prehistory and antiquity

[edit]Remnants of several Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures were found in all regions of Croatia,[3] but most of the sites are found in the river valleys of northern Croatia, including Slavonia. The most significant cultures whose presence was found include the Starčevo culture whose finds were discovered near Slavonski Brod and dated to 6100–5200 BC,[4] the Vučedol culture, the Baden culture and the Kostolac culture.[5][6] Most finds attributed to the Baden and Vučedol cultures are discovered in the area near the right bank of the Danube near Vukovar, Vinkovci and Osijek. The Baden culture sites in Slavonia are dated to 3600–3300 BC,[7] and Vučedol culture finds are dated to 3000–2500 BC.[8] The Iron Age left traces of the early Illyrian Hallstatt culture and the Celtic La Tène culture.[9] Much later, the region was settled by Illyrians and other tribes, including the Pannonians, who controlled much of present-day Slavonia. Even though archaeological finds of Illyrian settlements are much sparser than in areas closer to the Adriatic Sea, significant discoveries, for instance in Kaptol near Požega have been made.[10] The Pannonians first came into contact with the Roman Republic in 35 BC, when the Romans conquered Segestica, or modern-day Sisak. The conquest was completed in 11 BC, when the Roman province of Illyricum was established, encompassing modern-day Slavonia as well as a vast territory on the right bank of Danube. The province was renamed Pannonia and divided within two decades.[11]

Middle Ages

[edit]

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, which included the territory occupied by modern-day Slavonia, the area became a part of the Ostrogothic Kingdom by the end of the 5th century. However, control of the area proved a significant task, and Lombards were given increasing control of Pannonia in the 6th century, which ended in their withdrawal in 568 and the arrival of Pannonian Avars and Slavs, who established control of Pannonia by the year 582.[12] After the fall of the Avar Khaganate at the beginning of the 9th century, in Lower Pannonia there was a principality, governed by Slavic rulers who were vassals of Francs. The invasion of the Hungarian tribes overwhelmed this state. The eastern part of Slavonia in the 9th century may have been ruled by Bulgars.[13] The first king of Croatia Tomislav defeated Hungarian and Bulgarian invasions and spread the influence of Croatian kings northward to Slavonia.[14] The medieval Croatian kingdom reached its peak in the 11th century during the reigns of Petar Krešimir IV (1058–1074) and Dmitar Zvonimir (1075–1089).[15] When Stjepan II died in 1091, ending the Trpimirović dynasty, Ladislaus I of Hungary claimed the Croatian crown. Opposition to the claim led to a war and personal union of Croatia and Hungary in 1102, ruled by Coloman.[16] In the 2nd half of the 12th century, Croatia and the territory between the Drava and the Sava were governed by the ban of all Slavonia, appointed by the king. From the 13th century, a separate ban governed parts of present-day central Croatia, western Slavonia, and northwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina, an area where a new entity emerged named Kingdom of Slavonia (Latin: regnum Sclavoniae), while modern-day eastern Slavonia was a part of Hungary. Croatia and Slavonia were in 1476 united under the same ban (viceroy), but kept separate parliaments until 1558.[17]

The Ottoman conquests in Croatia led to the 1493 Battle of Krbava field and 1526 Battle of Mohács, both ending in decisive Ottoman victories. King Louis II of Hungary died at Mohács, and Ferdinand I of the House of Habsburg was elected in 1527 as the new ruler of Croatia, under the condition that he provide protection to Croatia against the Ottoman Empire, while respecting its political rights.[18][19] The period saw the rise to prominence of a native nobility such as the Frankopans and the Šubićs, and ultimately to numerous bans from the two families.[20] The present coat of arms of Slavonia, used in an official capacity as a part of the coat of arms of Croatia,[21] dates from this period—it was granted to Slavonia by king Vladislaus II Jagiellon on 8 December 1496.[22]

Ottoman conquest

[edit]

Following the Battle of Mohács, the Ottomans expanded their possessions in Slavonia seizing Đakovo in 1536 and Požega in 1537, defeating a Habsburg army led by Johann Katzianer, who was attempting to retake Slavonia, at Gorjani in September 1537. By 1540, Osijek was also under firm control of the Ottomans, and regular administration in Slavonia was introduced by establishing the Sanjak of Pojega. The Ottoman control in Slavonia expanded as Novska surrendered the same year. Turkish conquest continued—Našice were seized in 1541, Orahovica and Slatina in 1542, and in 1543, Voćin, Sirač and, after a 40-day siege, Valpovo. In 1544, Ottoman forces conquered Pakrac. Lessening hostilities brought about a five-year truce in 1547 and temporary stabilization of the border between Habsburg and Ottoman empires, with Virovitica becoming the most significant defensive Habsburg fortress and Požega the most significant Ottoman centre in Slavonia, as Ottoman advances to Sisak and Čazma were made, including a brief occupation of the cities. Further westward efforts of the Turkish forces presented a significant threat to Zagreb and the rest of Croatia and the Hungarian kingdom, prompting a greater defensive commitment by the Habsburg Monarchy. One year after the 1547 truce ended, Ivan Lenković devised a system of fortifications and troops in the border areas, a forerunner of the Croatian Military Frontier. Nonetheless, in 1552, the Ottoman conquest of Slavonia was completed when Virovitica was captured.[24] Ottoman advances in the Croatian territory continued until the 1593 Battle of Sisak, the first decisive Ottoman defeat, and a more lasting stabilisation of the frontier. During the Great Turkish War (1683–1698), Slavonia was regained in between 1684 and 1691 when the Ottomans abandoned the region—unlike western Bosnia, which had been part of Croatia before the Ottoman conquest.[19] The present-day southern border of Slavonia and the border between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina is a remnant of this outcome.[25][26]

The Ottoman wars instigated great demographic changes. Croats migrated towards Austria and the present-day Burgenland Croats are direct descendants of these settlers.[27] The Muslim population in Slavonia at the end of Turkish rule accounted for almost half of Slavonia's population who was indigenous, primarily Croats, less immigrants from Bosnia and Serbia and rarely genuine Turks or Arabs.[28] In the second half of the 16th century Vlachs from Slavonia were no longer an exclusive part of population because the Vlach privileges were attractive for many non-Vlachs who mixed with the Vlachs in order to get their status.[29] To replace the fleeing Croats, the Habsburgs called on the Orthodox populations of Bosnia and Serbia to provide military service in the Croatian Military Frontier. Serb migration into this region peaked during the Great Serb Migrations of 1690 and 1737–39.[30] The greatest Serb concentrations were in the eastern Slavonia, and Sremski Karlovci became the see of Serbian Orthodox metropolitans.[31] Part of the colonists came to Slavonia from area south of the Sava, especially from the Soli and Usora areas, continuing the process which already started after 1521. At beginning of the 17th century it seems that there was a new wave of colonization, about 10,000 families which are assumed to come from Sanjak of Klis or with less possibility from area of Sanjak of Bosnia.[32]

Habsburg Monarchy and Austria-Hungary

[edit]

The areas acquired through the Treaty of Karlowitz were assigned to Croatia, itself in the union with Hungary and the union ruled by the Habsburgs. The border area along the Una, Sava and Danube rivers became the Slavonian Military Frontier. At this time, Osijek took over the role of the administrative and military centre of the newly formed Kingdom of Slavonia from Požega.[26] The 1830s and 1840s saw romantic nationalism inspire the Croatian National Revival, a political and cultural campaign advocating unity of all South Slavs in the empire. Its primary focus was the establishment of a standard language as a counterweight to Hungarian, along with the promotion of Croatian literature and culture.[33] During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 Croatia sided with the Austrians, Ban Josip Jelačić helping to defeat the Hungarian forces in 1849, and ushering in a period of Germanization policy.[34] By the 1860s, failure of the policy became apparent, leading to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 and creation of a personal union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. The treaty left the issue of Croatia's status to Hungary as a part of Transleithania—and the status was resolved by the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement of 1868, when the kingdoms of Croatia and Slavonia were united as the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia.[35] After Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina following the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, the Military Frontiers were abolished and the Croatian and Slavonian Military Frontier territory returned to Croatia-Slavonia in 1881,[19] pursuant to provisions of the Croatian-Hungarian Settlement.[36][37] At that time, the easternmost point of Croatia-Slavonia became Zemun, as all of Syrmia was encompassed by the kingdom.[26]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia and World War II

[edit]

On 29 October 1918, the Croatian Sabor declared independence and decided to join the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs,[18] which in turn entered into union with the Kingdom of Serbia on 4 December 1918 to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.[39] The Treaty of Trianon was signed in 1920, at the end of World War I, between the Allies of World War I and Hungary as one of the successor states to Austria-Hungary.[40] The treaty established the southern border of Hungary along the Drava and Mura rivers, except in Baranya, where only the northern part of the county was kept by Hungary.[41][42] The territorial acquisition in Baranya was not made a part of Slavonia, even though adjacent to Osijek, because pre-1918 administrative divisions were disestablished by the new kingdom.[43] The political situation in the new kingdom deteriorated, leading to the dictatorship of King Alexander in January 1929.[44] The dictatorship formally ended in 1931 when the king imposed a more unitarian constitution transferring executive power to the king, and changed the name of the country to Yugoslavia.[45] The Cvetković–Maček Agreement of August 1939 created the autonomous Banovina of Croatia incorporating Slavonia. Pursuant to the agreement, the Yugoslav government retained control of defence, internal security, foreign affairs, trade, and transport while other matters were left to the Croatian Sabor and a crown-appointed 'Ban'.[46]

In April 1941, Yugoslavia was occupied by Germany and Italy. Following the invasion the territory of Slavonia was incorporated into the Independent State of Croatia, a Nazi-backed puppet state and assigned as a zone under German occupation for the duration of World War II. The regime introduced anti-semitic laws and conducted a campaign of ethnic cleansing and genocide against Serb and Roma populations,[47] exemplified by the Jasenovac and Stara Gradiška concentration camps,[48] but to a much lesser extent in Slavonia than in other regions, due to strategic interests of the Axis in keeping peace in the area.[49] The largest massacre occurred in 1942 in Voćin.[50][page needed]

Armed resistance soon developed in the region, and by 1942, the Yugoslav Partisans controlled substantial territories, especially in mountainous parts of Slavonia.[51] The Serbian royalist Chetniks, who carried out genocide against Croat civilian population,[52] struggled to establish a significant presence in Slavonia throughout the war.[49] Partisans led by Josip Broz Tito took full control of Slavonia in April 1945.[53] After the war, the new Yugoslav government interned local Germans in camps in Slavonia, the largest of which were in Valpovo and Krndija, where many died of hunger and diseases.[54]

Federal Yugoslavia and the independence of Croatia

[edit]

After World War II, Croatia—including Slavonia—became a single-party Socialist federal unit of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, ruled by the Communists, but enjoying a degree of autonomy within the federation. The autonomy effectively increased after the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution, basically fulfilling a goal of the Croatian Spring movement, and providing a legal basis for independence of the federative constituents.[55] In 1947, when all borders of the former Yugoslav constituent republics had been defined by demarcation commissions, pursuant to decisions of the AVNOJ of 1943 and 1945, the federal organization of Yugoslav Baranya was defined as Croatian territory allowing its integration with Slavonia. The commissions also set up the present-day 317.6-kilometre (197.3 mi) border between Serbia and Croatia in Syrmia, and along the Danube River between Ilok and mouth of the Drava and further north to the Hungarian border, the section south of confluence of the Drava matching the border between the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia and the Bács-Bodrog County that existed until 1918 and the end of World War I.[56]

The 1964 Slavonia earthquake caused widespread devastation and several human casualties. A large area of the region entered a period of several years of reconstruction afterwards.[57]

In the 1980s the political situation in Yugoslavia deteriorated with national tension fanned by the 1986 Serbian SANU Memorandum and the 1989 coups in Vojvodina, Kosovo and Montenegro.[58][59] In January 1990, the Communist Party fragmented along national lines, with the Croatian faction demanding a looser federation.[60] In the same year, the first multi-party elections were held in Croatia, with Franjo Tuđman's win raising nationalist tensions further.[61] The Serbs in Croatia, intent on achieving independence from Croatia, left the Sabor and declared the autonomy of areas that would soon become the unrecognized self-declared Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK).[62][63] As tensions rose, Croatia declared independence in June 1991; however the declaration came into effect on 8 October 1991.[64][65] Tensions escalated into the Croatian War of Independence when the Yugoslav National Army and various Serb paramilitaries attacked Croatia.[66] By the end of 1991, a high intensity war fought along a wide front reduced Croatia to controlling about two-thirds of its territory.[67][68]

In Slavonia, the first armed conflicts were clashes in Pakrac,[69][70] and Borovo Selo near Vukovar.[71][72] Western Slavonia was occupied in August 1991, following an advance by the Yugoslav forces north from Banja Luka across the Sava River.[73] This was partially pushed back by the Croatian Army in operations named Otkos 10,[66] and Orkan 91, which established a front line around Okučani and south of Pakrac that would hold virtually unchanged for more than three years until Operation Flash in May 1995.[74] Armed conflict in the eastern Slavonia, culminating in the Battle of Vukovar and a subsequent massacre,[75][76] also included heavy fighting and the successful defence of Osijek and Vinkovci. The front line stabilized and a ceasefire was agreed to on 2 January 1992, coming into force the next day.[77] After the ceasefire, United Nations Protection Force was deployed to the occupied areas,[78] but intermittent artillery and rocket attacks, launched from Serb-held areas of Bosnia, continued in several areas of Slavonia, especially in Slavonski Brod and Županja.[79][80] The war effectively ended in 1995 with Croatia achieving a decisive victory over the RSK in August 1995.[81] The remaining occupied areas—eastern Slavonia—were restored to Croatia pursuant to the Erdut Agreement of November 1995, with the process concluded in mid-January 1998.[82]

After the war, a number of towns and municipalities in the region were designated Areas of Special State Concern.

Geography

[edit]Political geography

[edit]

The Croatian counties were re-established in 1992, but their borders changed in some instances, with the latest revision taking place in 2006.[83] Slavonia consists of five counties—Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Baranja, Požega-Slavonia, Virovitica-Podravina and Vukovar-Syrmia counties—which largely cover the territory historically associated with Slavonia. The western borders of the five-county territory lie in the area where the western boundary of Slavonia generally has been located since the Ottoman conquest, with the remaining borders being at the international borders of Croatia.[26] This places the Croatian part of Baranya into the Slavonian counties, constituting the Eastern Croatia macroregion.[84] Terms Eastern Croatia and Slavonia are increasingly used as synonyms.[85] The Brod-Posavina County comprises two cities—Slavonski Brod and Nova Gradiška—and 26 Municipalities of Croatia.[86] The Osijek-Baranja County consists of seven cities—Beli Manastir, Belišće, Donji Miholjac, Đakovo, Našice, Osijek and Valpovo—and 35 municipalities.[87] The Požega-Slavonia County comprises five cities—Kutjevo, Lipik, Pakrac, Pleternica and Požega—and five municipalities.[88] The Virovitica-Podravina County covers three cities—Orahovica, Slatina and Virovitica—and 13 municipalities.[89] The Vukovar-Srijem County encompasses five cities—Ilok, Otok, Vinkovci, Vukovar and Županja—and 26 municipalities.[90] The whole of Slavonia is the eastern half of Central and Eastern (Pannonian) Croatia NUTS-2 statistical unit of Croatia, together with further areas of Central Croatia. Other statistical units correspond to the counties, cities and municipalities.[91] The five counties combined cover area size of 12,556 square kilometres (4,848 square miles), representing 22.2% of territory of Croatia.[92]

| County | Seat | Area (km2) | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brod-Posavina | Slavonski Brod | 2,043 | 130,782 |

| Osijek-Baranja | Osijek | 4,152 | 259,481 |

| Požega-Slavonia | Požega | 1,845 | 64,420 |

| Virovitica-Podravina | Virovitica | 2,068 | 70,660 |

| Vukovar-Syrmia | Vukovar | 2,448 | 144,438 |

| TOTAL: | 12,556 | 669,781 | |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics[92][93] | |||

Physical geography

[edit]

The boundaries of Slavonia, as a geographical region, do not necessarily coincide with the borders of the five counties, except in the south and east where the Sava and Danube rivers define them. The international borders of Croatia are boundaries common to both definitions of the region. In the north, the boundaries largely coincide because the Drava River is considered to be the northern border of Slavonia as a geographic region,[56] but this excludes Baranya from the geographic region's definition even though this territory is part of a county otherwise associated with Slavonia.[94][95][96] The western boundary of the geographic region is not specifically defined and it was variously defined through history depending on the political divisions of Croatia.[26] The eastern Croatia, as a geographic term, largely overlaps most definitions of Slavonia. It is defined as the territory of the Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Baranja, Požega-Slavonia, Virovitica-Podravina and Vukovar-Syrmia counties, including Baranya.[97]

Topography

[edit]

| Mountain | Peak | Elevation | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psunj | Brezovo Polje | 984 m (3,228 ft) | 45°24′N 17°19′E / 45.400°N 17.317°E |

| Papuk | Papuk | 953 m (3,127 ft) | 45°32′N 17°39′E / 45.533°N 17.650°E |

| Krndija | Kapovac | 792 m (2,598 ft) | 45°27′N 17°55′E / 45.450°N 17.917°E |

| Požeška Gora | Kapavac | 618 m (2,028 ft) | 45°17′N 17°35′E / 45.283°N 17.583°E |

Slavonia is entirely located in the Pannonian Basin, one of three major geomorphological parts of Croatia.[98] The Pannonian Basin took shape through Miocenian thinning and subsidence of crust structures formed during Late Paleozoic Variscan orogeny. The Paleozoic and Mesozoic structures are visible in Papuk, Psunj and other Slavonian mountains. The processes also led to the formation of a stratovolcanic chain in the basin 17 – 12 Mya (million years ago) and intensified subsidence observed until 5 Mya as well as flood basalts about 7.5 Mya. Contemporary uplift of the Carpathian Mountains prevented water flowing to the Black Sea, and the Pannonian Sea formed in the basin. Sediments were transported to the basin from uplifting Carpathian and Dinaric mountains, with particularly deep fluvial sediments being deposited in the Pleistocene during the uplift of the Transdanubian Mountains.[99] Ultimately, up to 3,000 metres (9,800 feet) of the sediment was deposited in the basin, and the Pannonian sea eventually drained through the Iron Gate gorge.[100] In the southern Pannonian Basin, the Neogene to Quaternary sediment depth is normally lower, averaging 500 to 1,500 metres (1,600 to 4,900 feet), except in central parts of depressions formed by subduction—around 4,000 metres (13,000 feet) in the Slavonia-Syrmia depression, 5,500 metres (18,000 feet) in the Sava depression and nearly 7,000 metres (23,000 feet) in the Drava depression, with the deepest sediment found between Virovitica and Slatina.[101]

The results of those processes are large plains in eastern Slavonia, Baranya and Syrmia, as well as in river valleys, especially along the Sava, Drava and Kupa. The plains are interspersed by the horst and graben structures, believed to have broken the Pannonian Sea surface as islands.[citation needed] The tallest among such landforms in Slavonia are 984-metre (3,228 ft) Psunj, and 953-metre (3,127 ft) Papuk—flanking the Požega Valley from the west and the north.[92] These two and Krndija, adjacent to Papuk, consist mostly of Paleozoic rocks which are 350 – 300 million years old. Požeška Gora and Dilj, to the east of Psunj and enveloping the valley from the south, consist of much more recent Neogene rocks, but Požeška Gora also contains Upper Cretaceous sediments and igneous rocks forming the main, 30-kilometre (19 mi) ridge of the hill and representing the largest igneous landform in Croatia. A smaller igneous landform is also present on Papuk, near Voćin.[102] The two mountains, as well as Moslavačka gora, west of Pakrac, are possible remnants of a volcanic arc related to Alpine orogeny—uplifting of the Dinaric Alps.[103] The Đakovo – Vukovar loess plain, extending eastward from Dilj and representing the watershed between the Vuka and Bosut rivers, gradually rises to the Fruška Gora south of Ilok.[104]

Hydrography and climate

[edit]The largest rivers in Slavonia are found along or near its borders—the Danube, Sava and Drava. The length of the Danube, flowing along the eastern border of Slavonia and through the cities of Vukovar and Ilok, is 188 kilometres (117 miles), and its main tributaries are the Drava 112-kilometre (70 mi) and the Vuka. The Drava discharges into the Danube near Aljmaš, east of Osijek, while mouth of the Vuka is located in Vukovar.

Major tributaries of the Sava, flowing along the southern border of Slavonia and through cities of Slavonski Brod and Županja are 89-kilometre (55 mi) the Orljava flowing through Požega, and the Bosut—whose 151-kilometre (94 mi) course in Slavonia takes it through Vinkovci. There are no large lakes in Slavonia. The largest ones are Lake Kopačevo whose surface area varies between 1.5 and 3.5 square kilometres (0.58 and 1.35 square miles), and Borovik Reservoir covering 2.5 square kilometres (0.97 square miles).[92] The Lake Kopačevo is connected to the Danube via Hulovski canal, situated within the Kopački Rit wetland,[105] while the Lake Borovik is an artificial lake created in 1978 in the upper course of the Vuka River.[106]

The entirety of Slavonia belongs to the Danube basin and the Black Sea catchment area, but it is divided in two sub-basins. One of those drains into the Sava—itself a Danube tributary—and the other into the Drava or directly into the Danube. The drainage divide between the two sub-basins runs along the Papuk and Krndija mountains, in effect tracing the southern boundary of the Virovitica-Podravina County and the northern boundary of Požega-Slavonia County, cuts through the Osijek-Podravina County north of Đakovo, and finally bisects the Vukovar-Syrmia County running between Vukovar and Vinkovci to reach Fruška Gora southwest of Ilok. All of Brod-Posavina County is located in the Sava sub-basin.[107]

Most of Croatia, including Slavonia, has a moderately warm and rainy humid continental climate as defined by the Köppen climate classification. Mean annual temperature averages 10 to 12 °C (50 to 54 °F), with the warmest month, July, averaging just below 22 °C (72 °F). Temperature peaks are more pronounced in the continental areas—the lowest temperature of −27.8 °C (−18.0 °F) was recorded on 24 January 1963 in Slavonski Brod,[108] and the highest temperature of 40.5 °C (104.9 °F) was recorded on 5 July 1950 in Đakovo.[109] The lowest level of precipitation is recorded in the eastern parts of Slavonia at less than 700 millimetres (28 inches) per year, mostly during the growing season. The western parts of Slavonia receive 900 to 1,000 millimetres (35 to 39 inches) precipitation. Low winter temperatures and the distribution of precipitation throughout the year normally result in snow cover, and freezing rivers—requiring use of icebreakers, and in extreme cases explosives,[110] to maintain the flow of water and navigation.[111] Slavonia receives more than 2,000 hours of sunshine per year on average. Prevailing winds are light to moderate, northeasterly and southwesterly.[92]

Demographics

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1857 | 412,303 | — |

| 1869 | 472,317 | +14.6% |

| 1880 | 470,373 | −0.4% |

| 1890 | 548,264 | +16.6% |

| 1900 | 604,664 | +10.3% |

| 1910 | 670,246 | +10.8% |

| 1921 | 666,723 | −0.5% |

| 1931 | 755,860 | +13.4% |

| 1948 | 782,596 | +3.5% |

| 1953 | 830,224 | +6.1% |

| 1961 | 903,350 | +8.8% |

| 1971 | 950,403 | +5.2% |

| 1981 | 954,491 | +0.4% |

| 1991 | 977,391 | +2.4% |

| 2001 | 891,259 | −8.8% |

| 2011 | 805,998 | −9.6% |

| 2021 | 665,858 | −17.4% |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics publications1 | ||

According to the 2011 census, the total population of the five counties of Slavonia was 806,192, accounting for 19% of population of Croatia. The largest portion of the total population of Slavonia lives in Osijek-Baranja county, followed by Vukovar-Syrmia county. Požega-Slavonia county is the least populous county of Slavonia. Overall the population density stands at 64.2 persons per square kilometre. The population density ranges from 77.6 to 40.9 persons per square kilometre, with the highest density recorded in Brod-Posavina county and the lowest in Virovitica-Podravina county. Osijek is the largest city in Slavonia, followed by Slavonski Brod, Vinkovci and Vukovar. Other cities in Slavonia have populations below 20,000.[93] According to the 2001 census, Croats account for 85.6 percent of population of Slavonia, and the most significant ethnic minorities are Serbs and Hungarians, comprising 8.8 percent and 1.4 percent of the population respectively. The largest portion of the Serb minority was recorded in Vukovar-Syrmia county (15 percent), while the largest Hungarian minority, in both relative and absolute terms, was observed in Osijek-Baranja county. The census recorded 85.4% of the population declaring themselves as Catholic, with further 4.4% belonging to Serbian Orthodox Church and 0.7% Muslims. 3.1% declared themselves as non-religious, agnostics or declined to declare their religion. The most widely used language in the region is Croatian, declared as the first language by 93.6% of the total population, followed by Serbian (2.6%) and Hungarian (1.0%).[112]

The demographic history of Slavonia is characterised by significant migrations, as is that of Croatia as a whole, starting with the arrival of the Croats, between the 6th and 9th centuries.[113] Following the establishment of the personal union of Croatia and Hungary in 1102,[16] and the joining of the Habsburg monarchy in 1527,[18] the Hungarian and German speaking population of Croatia began gradually increasing in number. The processes of Magyarization and Germanization varied in intensity but persisted until the beginning of the 20th century.[34][114] The Ottoman conquests initiated a westward migration of parts of the Croatian population;[115] the Burgenland Croats are direct descendants of some of those settlers.[27] To replace the fleeing Croats the Habsburgs called on the Orthodox populations of Bosnia and Serbia to provide military service in the Croatian Military Frontier. Serb migration into this region peaked during the Great Serb Migrations of 1690 and 1737–39.[30] Following the collapse of Austria-Hungary in 1918, the Hungarian population declined, due to emigration and ethnic bias. The changes were especially significant in the areas north of the Drava river, and Baranja County where they represented the majority before World War I.[116]

| Rank | City | County | Urban population | Municipal population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Osijek | Osijek-Baranja | 83,496 | 107,784 |

| 2 | Slavonski Brod | Brod-Posavina | 53,473 | 59,507 |

| 3 | Vinkovci | Vukovar-Syrmia | 31,961 | 35,375 |

| 4 | Vukovar | Vukovar-Syrmia | 26,716 | 28,016 |

| 5 | Požega | Požega-Slavonia | 19,565 | 26,403 |

| 6 | Đakovo | Osijek-Baranja | 19,508 | 27,798 |

| 7 | Virovitica | Virovitica-Podravina | 14,663 | 21,327 |

| 8 | Županja | Vukovar-Syrmia | 12,115 | 12,185 |

| 9 | Nova Gradiška | Brod-Posavina | 11,767 | 14,196 |

| 10 | Slatina | Virovitica-Podravina | 10,152 | 13,609 |

| County seats are indicated with bold font. Sources: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2011 Census[93] | ||||

Since the end of the 19th century there was substantial economic emigration abroad from Croatia in general.[117][118] After World War I, the Yugoslav regime confiscated up to 50 percent of properties and encouraged settlement of the land by Serb volunteers and war veterans in Slavonia,[26] only to have them evicted and replaced by up to 70,000 new settlers by the regime during World War II.[119] During World War II and in the period immediately following the war, there were further significant demographic changes, as the German-speaking population, the Danube Swabians, were either forced or otherwise compelled to leave—reducing their number from the prewar German population of Yugoslavia of 500,000, living in Slavonia and other parts of present-day Croatia and Serbia, to the figure of 62,000 recorded in the 1953 census.[120] The 1940s and the 1950s in Yugoslavia were marked by colonisation of settlements where the displaced Germans used to live, by people from the mountainous parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro, and migrations to larger cities spurred on by the development of industry.[121] [failed verification] In the 1960s and 1970s, another wave of economic migrants left—largely moving to Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Western Europe.[122][123][124]

The most recent changes to the ethnic composition of Slavonian counties occurred between censuses conducted in 1991 and 2001. The 1991 census recorded a heterogenous population consisting mostly of Croats and Serbs—at 72 percent and 17 percent of the total population respectively. The Croatian War of Independence, and the ethnic fracturing of Yugoslavia that preceded it, caused an exodus of the Croat population followed by an exodus of Serbs. The return of refugees since the end of hostilities is not complete—a majority of Croat refugees returned, while fewer Serbs did. In addition, ethnic Croats moved to Slavonia from Bosnia and Herzegovina and from Serbia.[84]

Economy and transport

[edit]

The economy of Slavonia is largely based on wholesale and retail trade and processing industry. Food processing is one of the most significant types of the processing industries in the region, supporting agricultural production in the area and encompassing meat packing, fruit and vegetable processing, sugar refining, confectionery and dairy industry. In addition, there are wineries in the region that are significant to economy of Croatia. Other types of the processing industry significant to Slavonia are wood processing, including production of furniture, cellulose, paper and cardboard; metalworking, textile industry and glass production. Transport and civil engineering are two further significant economic activities in Slavonia.[125]

The largest industrial centre of Slavonia is Osijek, followed by other county seats—Slavonski Brod, Virovitica, Požega and Vukovar, as well as several other cities, especially Vinkovci.[126][127][128][129][130]

The gross domestic product (GDP) of the five counties in Slavonia combined (in year 2008) amounted to 6,454 million euro, or 8,005 euro per capita—27.5% below Croatia's national average. The GDP of the five counties represented 13.6% of Croatia's GDP.[131] Several Pan-European transport corridors run through Slavonia: corridor Vc as the A5 motorway, corridor X as the A3 motorway and a double-track railway spanning Slavonia from west to east, and corridor VII—the Danube River waterway.[132] The waterway is accessed through the Port of Vukovar, the largest Croatian river port, situated on the Danube itself, and the Port of Osijek on the Drava River, 14.5 kilometres (9.0 miles) away from confluence of the rivers.[133]

Another major sector of the economy of Slavonia is agriculture, which also provides part of the raw materials for the processing industry. Out of 1,077,403 hectares (2,662,320 acres) of utilized agricultural land in Croatia, 493,878 hectares (1,220,400 acres), or more than 45%, are found in Slavonia, with the largest portion of the land situated in the Osijek-Baranja and Vukovar-Syrmia counties. The largest areas are used for production of cereals and oilseeds, covering 574,916 hectares (1,420,650 acres) and 89,348 hectares (220,780 acres) respectively. Slavonia's share in Croatia's agriculturally productive land is greatest in the production of cereals (53.5%), legumes (46.8%), oilseeds (88.8%), sugar beet (90%), tobacco (97.9%), plants used in pharmaceutical or perfume industry (80.9%), flowers, seedlings and seeds (80.3%) and plants used in the textile industry (69%). Slavonia also contributes 25.7% of cattle, 42.7% of pigs and 20% of the poultry stock of Croatia. There are 5,138 hectares (12,700 acres) of vineyards in Slavonia, representing 18.6% of total vineyards area in Croatia. Production of fruit and nuts also takes up a significant agricultural area. Apple orchards cover 1,261 hectares (3,120 acres), representing 42.3% of Croatia's apple plantations, plums are produced in orchards encompassing 450 hectares (1,100 acres) or 59.7% of Croatia's plum plantations and hazelnut orchards cover 319 hectares (790 acres), which account for 72.4% of hazelnut plantations in Croatia. Other significant permanent crops are cherries, pears, peaches and walnuts.[134]

| Counties of Slavonia by GDP, in million Euro | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

| Brod-Posavina | 575 | 643 | 699 | 717 | 782 | 786 | 869 | 931 | 1,074 | 968 |

| Osijek-Baranja | 1,370 | 1,499 | 1,699 | 1,710 | 1,884 | 1,999 | 2,193 | 2,538 | 2,844 | 2,590 |

| Požega-Slavonia | 337 | 371 | 395 | 428 | 456 | 472 | 484 | 541 | 557 | 510 |

| Virovitica-Podravina | 378 | 434 | 465 | 478 | 493 | 497 | 584 | 616 | 661 | 561 |

| Vukovar-Srijem | 651 | 723 | 795 | 836 | 889 | 964 | 1,098 | 1,144 | 1,318 | 1,180 |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics[135][136][137][138] | ||||||||||

| Counties of Slavonia by GDP per capita, in Euro | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

| Brod-Posavina | 3,260 | 3,633 | 3,955 | 4,065 | 4,452 | 4,487 | 4,972 | 5,345 | 6,183 | 5,606 |

| Osijek-Baranja | 4,147 | 4,537 | 5,149 | 5,199 | 5,750 | 6,127 | 6,757 | 7,875 | 8,871 | 8,112 |

| Požega-Slavonia | 3,934 | 4,320 | 4,610 | 5,020 | 5,383 | 5,605 | 5,786 | 6,505 | 6,750 | 6,229 |

| Virovitica-Podravina | 4,045 | 4,654 | 5,016 | 5,176 | 5,410 | 5,485 | 6,497 | 6,923 | 7,485 | 6,399 |

| Vukovar-Srijem | 3,184 | 3,528 | 3,903 | 4,127 | 4,414 | 4,807 | 5,501 | 5,756 | 6,647 | 5,974 |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics[135][136][137][138] | ||||||||||

In 2010, only two companies headquartered in Slavonia ranked among top 100 Croatian companies—Belje, agricultural industry owned by Agrokor,[139] and Belišće, paper mill and paper packaging material factory,[140] headquartered in Darda and Belišće respectively, both in Osijek-Baranja County. Belje ranks as the 44th and Belišće as the 99th largest Croatian company by income. Other significant businesses in the county include civil engineering company Osijek-Koteks (rank 103),[141] Saponia detergent and personal care product factory (rank 138),[142] Biljemerkant retail business (rank 145),[143] and Našicecement cement plant (rank 165), a part of Nexe Grupa construction product manufacturing company.[144] Sugar refining company Viro,[145] ranked the 101st and headquartered in Virovitica, is the largest company in Virovitica-Podravina County. Đuro Đaković Montaža d.d., a part of metal processing industry Đuro Đaković Holding of Slavonski Brod,[146] ranks the 171st among the Croatian companies and it is the largest business in Brod-Posavina County. Another agricultural industry company, Kutjevo d.d., headquartered in Kutjevo, is the largest company in Požega-Slavonia County,[147] ranks the 194th in Croatia by business income. Finally, the largest company by income in Vukovar-Syrmia county is another Agrokor owned agricultural production company—Vupik, headquartered in Vukovar,[148] and ranking the 161st among the companies headquartered in Croatia.[149]

Culture

[edit]

The cultural heritage of Slavonia represents a blend of social influences through its history, especially since the end of the 17th century, and the traditional culture. A particular impact was made by Baroque art and architecture of the 18th century, when the cities of Slavonia started developing after the Ottoman wars ended and stability was restored to the area. The period saw great prominence of the nobility, who were awarded estates in Slavonia by the imperial court in return for their service during the wars. They included Prince Eugene of Savoy, the House of Esterházy, the House of Odescalchi, Philipp Karl von Eltz-Kempenich, the House of Prandau-Normann, the House of Pejačević and the House of Janković. That in turn encouraged an influx of contemporary European culture to the region. Subsequent development of the cities and society saw the influence of Neoclassicism, Historicism and especially of Art Nouveau.[94]

The heritage of the region includes numerous landmarks, especially manor houses built by the nobility in largely in the 18th and the 19th centuries. Those include Prandau-Normann and Prandau-Mailath manor houses in Valpovo and Donji Miholjac respectively,[150][151] manor houses in Baranja—in Bilje,[152] at a former Esterházy estate in Darda,[153] in Tikveš,[154] and in Kneževo.[155] Pejačevićs built several residences, the most representative ones among them being manor house in Virovitica and the Pejačević manor house in Našice.[156] Further east, along the Danube, there are Odescalchi manor house in Ilok,[157] and Eltz manor house in Vukovar—the latter sustained extensive damage during the Battle of Vukovar in 1991,[158] but it was reconstructed by 2011.[159] In the southeast of the region, the most prominent are Kutjevo Jesuit manor house,[160] and Cernik manor house, located in Kutjevo and Cernik respectively.[161] The period also saw construction of Tvrđa and Brod fortifications in Osijek and Slavonski Brod.[162][163] Older, medieval fortifications are preserved only as ruins—the largest among those being Ružica Castle near Orahovica.[164] Another landmark dating to the 19th century is the Đakovo Cathedral—hailed by the Pope John XXIII as the most beautiful church situated between Venice and Istanbul.[165][166]

Slavonia significantly contributed to the culture of Croatia as a whole, both through works of artists and through patrons of the arts—most notable among them being Josip Juraj Strossmayer.[168] Strossmayer was instrumental in the establishment of the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts, later renamed the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts,[169] and the reestablishment of the University of Zagreb.[170] A number of Slavonia's artists, especially writers, made considerable contributions to Croatian culture. Nineteenth-century writers who are most significant in Croatian literature include Josip Eugen Tomić, Josip Kozarac, and Miroslav Kraljević—author of the first Croatian novel.[168] Significant twentieth-century poets and writers in Slavonia were Dobriša Cesarić, Dragutin Tadijanović, Ivana Brlić-Mažuranić and Antun Gustav Matoš.[171] Painters associated with Slavonia, who contributed greatly to Croatian art, were Miroslav Kraljević and Bela Čikoš Sesija.[172]

Slavonia is a distinct region of Croatia in terms of ethnological factors in traditional music. It is a region where traditional culture is preserved through folklore festivals. Typical traditional music instruments belong to the tamburica and bagpipe family.[173] The tamburica is the most representative musical instrument associated with Slavonia's traditional culture. It developed from music instruments brought by the Ottomans during their rule of Slavonia, becoming an integral part of the traditional music, its use surpassing or even replacing the use of bagpipes and gusle.[174] A distinct form of traditional song, originating in Slavonia, the bećarac, is recognized as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO.[175][176]

Out of 122 Croatia's universities and other institutions of higher education,[177] Slavonia is home to one university—Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek—[178] as well as three polytechnics in Požega, Slavonski Brod and Vukovar, as well as a college in Virovitica—all set up and run by the government.[179][180] The University of Osijek, has been established in 1975,[181] but the first institution of higher education in the city was Studium Philosophicum Essekini founded in 1707, and active until 1780.[182] Another historical institution of higher education was Academia Posegana operating in Požega between 1761 and 1776,[183] as an extension of a gymnasium operating in the city continuously,[184] since it opened in 1699 as the first secondary education school in Slavonia.[185]

Cuisine and wines

[edit]

The cuisine of Slavonia reflects cultural influences on the region through the diversity of its culinary influences. The most significant among those were from Hungarian, Viennese, Central European, as well as Turkish and Arab cuisines brought by series of conquests and accompanying social influences. The ingredients of traditional dishes are pickled vegetables, dairy products and smoked meats.[186] The most famous traditional preserved meat product is kulen, one of a handful Croatian products protected by the EU as indigenous products.[187]

Slavonia is one of Croatia's winemaking sub-regions, a part of its continental winegrowing region. The best known winegrowing areas of Slavonia are centered on Đakovo, Ilok and Kutjevo, where Graševina grapes are predominant, but other cultivars are increasingly present.[188] In past decades, an increasing quantity of wine production in Slavonia was accompanied by increasing quality and growing recognition at home and abroad.[189] Grape vines were first grown in the region of Ilok, as early as the 3rd century AD. The oldest Slavonian wine cellar still in continuous use for winemaking is located in Kutjevo—built in 1232 by Cistercians.[190]

Slavonian oak is used to make botti, large barrels traditionally used in the Piedmont region of Italy to make nebbiolo wines.[191]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Frucht, Richard C. (2004). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. Vol. 1 (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 413. ISBN 1-57607-800-0. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Alemko Gluhak (March 2003). "Ime Slavonije" [Name of Slavonia]. Migracijske I Etničke Teme (in Croatian). 19 (1). Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies, Zagreb: 111–117. ISSN 1333-2546. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Tihomila Težak-Gregl (April 2008). "Study of the Neolithic and Eneolithic as reflected in articles published over the 50 years of the journal Opuscula archaeologica". Opvscvla Archaeologica Radovi Arheološkog Zavoda. 30 (1). University of Zagreb, Faculty of Philosophy, Archaeological Department: 93–122. ISSN 0473-0992. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Kornelija Minichreiter; Ines Krajcar Bronić (April 2007). "Novi radiokarbonski datumi rane starčevačke kulture u Hrvatskoj" [New Radiocarbon Dates for the Early Starčevo Culture in Croatia]. Prilozi Instituta Za Arheologiju U Zagrebu (in Croatian). 23 (1). Institute of Archaeology, Zagreb. ISSN 1330-0644. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Balen, Jacqueline (December 2005). "The Kostolac horizon at Vučedol". Opvscvla Archaeologica Radovi Arheološkog Zavoda. 29 (1). University of Zagreb, Faculty of Philosophy, Archaeological Department: 25–40. ISSN 0473-0992. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Tihomila Težak-Gregl (December 2003). "Prilog poznavanju neolitičkih obrednih predmeta u neolitiku sjeverne Hrvatske" [A Contribution to Understanding Neolithic Ritual Objects in the Northern Croatia Neolithic]. Opvscvla Archaeologica Radovi Arheološkog Zavoda (in Croatian). 27 (1). University of Zagreb, Faculty of Philosophy, Archaeological Department: 43–48. ISSN 0473-0992. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ "Badenska kultura" [Baden culture] (in Croatian). Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ "Vučedolska kultura" [Vučedol culture] (in Croatian). Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Hrvoje Potrebica; Marko Dizdar (July 2002). "Prilog poznavanju naseljenosti Vinkovaca i okolice u starijem željeznom dobu" [A Contribution to Understanding Continuous Habitation of Vinkovci and its Surroundings in the Early Iron Age]. Prilozi Instituta Za Arheologiju U Zagrebu (in Croatian). 19 (1). Institut za arheologiju: 79–100. ISSN 1330-0644. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ John Wilkes (1995). The Illyrians. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-631-19807-9. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ András Mócsy (1974). Pannonia and Upper Moesia. Routledge. pp. 32–39. ISBN 978-0-7100-7714-1. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Danijel Dzino (2010). Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-18646-0. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Alimov, D. E. (2016). Etnogenez khorvatov: formirovaniye khorvatskoy etnopoliticheskoy obshchnosti v VII–IX vv Этногенез хорватов: формирование хорватской этнополитической общности в VII–IX вв. [Ethnogenesis of Croats: the formation of the Croatian ethnopolitical community in the 7th – 9th centuries] (PDF) (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Нестор-История. pp. 303–305. ISBN 978-5-4469-0970-4. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Vladimir Posavec (March 1998). "Povijesni zemljovidi i granice Hrvatske u Tomislavovo doba" [Historical maps and borders of Croatia in age of Tomislav]. Radovi Zavoda Za Hrvatsku Povijest (in Croatian). 30 (1): 281–290. ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Lujo Margetić (January 1997). "Regnum Croatiae et Dalmatiae u doba Stjepana II" [Regnum Croatiae et Dalmatiae in age of Stjepan II]. Radovi Zavoda Za Hrvatsku Povijest (in Croatian). 29 (1): 11–20. ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ a b Ladislav Heka (October 2008). "Hrvatsko-ugarski odnosi od sredinjega vijeka do nagodbe iz 1868. s posebnim osvrtom na pitanja Slavonije" [Croatian-Hungarian relations from the Middle Ages to the Compromise of 1868, with a special survey of the Slavonian issue]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). 8 (1). Hrvatski institut za povijest – Podružnica za povijest Slavonije, Srijema i Baranje: 152–173. ISSN 1332-4853. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ "Slavonija". Croatian Encyclopedia. Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography. 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Povijest saborovanja" [History of parliamentarism] (in Croatian). Sabor. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Frucht 2005, p. 422-423

- ^ Márta Font (July 2005). "Ugarsko Kraljevstvo i Hrvatska u srednjem vijeku" [Hungarian Kingdom and Croatia in the Middlea Ages]. Povijesni prilozi (in Croatian). 28 (28). Croatian Institute of History: 7–22. ISSN 0351-9767. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Zakon o grbu, zastavi i himni Republike Hrvatske te zastavi i lenti predsjednika Republike Hrvatske" [Coat of Arms, Flag and Anthem of the Republic of Croatia, Flag and Sash of the President of the Republic of Croatia Act]. Narodne Novine (in Croatian). 21 December 1990. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ Davor Brunčić (2003). "The symbols of Osijek-Baranja County" (PDF). Osijek-Baranja County. p. 44. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Franjo Emanuel Hoško (2005). "Ibrišimović, Luka" [Ibrišimović, Luka]. Hrvatski Biografski Leksikon (in Croatian). Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Dino Mujadžević (July 2009). "Osmanska osvajanja u Slavoniji 1552. u svjetlu osmanskih arhivskih izvora" [The 1552 Ottoman invasions in Slavonia according to the Ottoman archival sources]. Povijesni prilozi (in Croatian). 36 (36). Croatian History Institute: 89–107. ISSN 0351-9767. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Lane (1973), p. 409

- ^ a b c d e f Anita Blagojević (December 2008). "Zemljopisno, povijesno, upravno i pravno određenje istočne Hrvatske – korijeni suvremenog regionalizma" [Geographical, historical, administrative and legal determination of the eastern Croatia – the roots of modern regionalism]. Zbornik Pravnog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Rijeci (in Croatian). 29 (2). University of Rijeka: 1149–1180. ISSN 1846-8314. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Povijest Gradišćanskih Hrvatov" [History of Burgenland Croats] (in Croatian). Croatian Cultural Association in Burgenland. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Nihad Kulenović, 2016, Cross border cooperation between Baranja and Tuzla Region, http://baza.gskos.hr/Graniceidentiteti.pdf #page=234

- ^ Kaser, Karl (1997). Slobodan seljak i vojnik: Rana krajiška društva, 1545-1754. Naprijed. ISBN 978-953-178-064-3.

- ^ a b John R. Lampe; Marvin R. Jackson (1982). Balkan economic history, 1550–1950: from imperial borderlands to developing nations. Indiana University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-253-30368-4. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Ivo Banac (2015). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-5017-0194-8.

- ^ Nenad Moačanin, 2003, Požega i Požeština u sklopu Osmanlijskoga carstva : (1537.-1691.),{1555. svi obveznici "klasičnih" rajinskih dažbina u Srijemu i Slavoniji nazvani su "vlasima", što uključuje ne samo starosjedilačko hrvatsko pučanstvo nego i Mađare!), Neki su se dakle starosjedioci vraćali, a dijelom su kolonisti sa statusom koji je imao nekih sličnosti s vlaškim (a da sami nisu nužno bili ni porijeklom Vlasi) dolazili iz prekosavskih krajeva, posebice s područja Soli i Usore, nastavljajući tako proces započet već nakon 1521. Ako bi se ta pojava mogla povezati s preseljenjem, uglavnom u Podunavlje, 10 000 obitelji iz Kliskog sandžaka nakon pobune (1604?)98, i ako je prihvatljivo da ih se dosta naselilo i oko Požege, onda bismo možda mogli djelomice tumačiti bune i hajdučiju u to vrijeme dolaskom "buntovnijeg" pučanstva. Novo je stanovništvo moglo doći i s područja Bosanskog sandžaka, ali za sada se "kliska" pretpostavka čini nešto sigurnijom} http://baza.gskos.hr/cgi-bin/unilib.cgi?form=D1430506006 #page=35,40,80

- ^ Nikša Stančić (February 2009). "Hrvatski narodni preporod – ciljevi i ostvarenja" [Croatian National Revival – goals and achievements]. Cris: časopis Povijesnog društva Križevci (in Croatian). 10 (1): 6–17. ISSN 1332-2567. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ a b Ante Čuvalo (December 2008). "Josip Jelačić – Ban of Croatia". Review of Croatian History. 4 (1). Croatian Institute of History: 13–27. ISSN 1845-4380. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Constitution of Union between Croatia-Slavonia and Hungary". H-net.org. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ Ladislav Heka (December 2007). "Hrvatsko-ugarska nagodba u zrcalu tiska" [Croatian-Hungarian compromise in light of press clips]. Zbornik Pravnog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Rijeci (in Croatian). 28 (2). University of Rijeka: 931–971. ISSN 1330-349X. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Branko Dubravica (January 2002). "Političko-teritorijalna podjela i opseg civilne Hrvatske u godinama sjedinjenja s vojnom Hrvatskom 1871.-1886" [Political and territorial division and scope of civilian Croatia in period of unification with the Croatian military frontier 1871–1886]. Politička Misao (in Croatian). 38 (3). University of Zagreb, Faculty of Political Sciences: 159–172. ISSN 0032-3241. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Slavonia Round Trip". Get-by-bus. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ Spencer Tucker; Priscilla Mary Roberts (2005). World War I: encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 1286. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

- ^ Craig, G.A. (1966). Europe since 1914. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York.

- ^ "Trianon, Treaty of". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2009.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer (2005). Encyclopedia of World War I (1 ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 1183. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

Virtually the entire population of what remained of Hungary regarded the Treaty of Trianon as manifestly unfair, and agitation for revision began immediately.

- ^ "Parlamentarni izbori u Brodskom kotaru 1923. godine" [Parliamentary Elections in the Brod District in 1932]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). 3 (1). Croatian Institute of History – Slavonia, Syrmium and Baranya history branch: 452–470. November 2003. ISSN 1332-4853. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Zlatko Begonja (November 2009). "Ivan Pernar o hrvatsko-srpskim odnosima nakon atentata u Beogradu 1928. godine" [Ivan Pernar on Croatian-Serbian relations after 1928 Belgrade assassination]. Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru (in Croatian) (51). Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts: 203–218. ISSN 1330-0474. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Cvijeto Job (2002). Yugoslavia's Ruin: The Bloody lessons of nationalism, a patriot's warning. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7425-1784-4. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Klemenčić, Žagar 2004, p. 121–123

- ^ Klemenčić, Žagar 2004, p. 153–156

- ^ Josip Kolanović (November 1996). "Holocaust in Croatia – Documentation and research perspectives". Arhivski vjesnik (39). Croatian State Archives: 157–174. ISSN 0570-9008. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ a b Jelić Butić, Fikreta (1986). Četnici u Hrvatskoj, 1941-1945 [Chetniks in Croatia, 1941-1945]. Globus. p. 101. ISBN 978-86-343-0010-9.

- ^ Škiljan, Filip (2014). Organizirana prisilna iseljavanja Srba iz NDH (PDF). Zagreb: Srpsko narodno vijeće. ISBN 978-953-7442-13-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2018.

- ^ Mihajlo Ogrizović (March 1972). "Obrazovanje i odgoj mlade generacije i odraslih u Slavoniji za vrijeme NOB" [Education and schooling of youths and adults in Slavonia during the World War II]. Journal – Institute of Croatian History (in Croatian). 1 (1). Institute of Croatian History, Faculty of Philosophy Zagreb: 287–327. ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Klemenčić, Žagar 2004, p. 184

- ^ Zdravko Dizdar (December 2005). "Prilog istraživanju problema Bleiburga i križnih putova (u povodu 60. obljetnice)" [An addition to the research of the problem of Bleiburg and way of the cross (dedicated to their 60th anniversary)]. The Review of Senj (in Croatian). 32 (1). City Museum Senj – Senj Museum Society: 117–193. ISSN 0582-673X.

- ^ Geiger, Vladimir (2006). "Logori za folksdojčere u Hrvatskoj nakon Drugoga svjetskog rata 1945-1947" [Camps for Volksdeutsch in Croatia after the Second World War, 1945 to 1947]. Časopis Za Suvremenu Povijest (in Croatian). 38 (3): 1098, 1100.

- ^ Roland Rich (1993). "Recognition of States: The Collapse of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union". European Journal of International Law. 4 (1): 36–65. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejil.a035834. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ a b Egon Kraljević (November 2007). "Prilog za povijest uprave: Komisija za razgraničenje pri Predsjedništvu Vlade Narodne Republike Hrvatske 1945.-1946" [Contribution to the history of public administration: commission for the boundary demarcation at the government's presidency of the People's Republic of Croatia, 1945–1946 (English language summary title)]. Arhivski vjesnik (in Croatian). 50 (50). Croatian State Archives. ISSN 0570-9008. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ Josipović Batorek 2013, p. 195.

- ^ Frucht 2005, p. 433

- ^ "Leaders of a Republic in Yugoslavia Resign". The New York Times. Reuters. 12 January 1989. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Davor Pauković (1 June 2008). "Posljednji kongres Saveza komunista Jugoslavije: uzroci, tijek i posljedice raspada" [Last Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia: Causes, Consequences and Course of Dissolution]. Časopis Za Suvremenu Povijest (in Croatian). 1 (1). Centar za politološka istraživanja: 21–33. ISSN 1847-2397. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Branka Magas (13 December 1999). "Obituary: Franjo Tudjman". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Chuck Sudetic (2 October 1990). "Croatia's Serbs Declare Their Autonomy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Routledge. 1998. pp. 272–278. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Chuck Sudetic (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Ceremonial session of the Croatian Parliament on the occasion of the Day of Independence of the Republic of Croatia". Official web site of the Parliament of Croatia. Sabor. 7 October 2004. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ a b Chuck Sudetic (4 November 1991). "Army Rushes to Take a Croatian Town". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "Croatia Clashes Rise; Mediators Pessimistic". The New York Times. 19 December 1991. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Charles T. Powers (1 August 1991). "Serbian Forces Press Fight for Major Chunk of Croatia". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Stephen Engelberg (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Stephen Engelberg (4 March 1991). "Serb-Croat Showdown in One Village Square". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Stephen Engelberg (5 May 1991). "One More Dead as Clashes Continue in Yugoslavia". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Nation 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren; Boduszynski, Mieczyslaw; Draschtak, Raphael; Graovac, Igor; Kent, Sally; Malli, Rüdiger; Pavlović, Srdja; Vuić, Jason (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991–1995" (PDF). In Ingrao, Charles W.; Emmert, Thomas Allan (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: a Scholars' Initiative. Purdue University Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ Roger Cohen (2 May 1995). "CROATIA HITS AREA REBEL SERBS HOLD, CROSSING U.N. LINES". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Chuck Sudetic (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Eugene Brcic (29 June 1998). "Croats bury victims of Vukovar massacre". The Independent. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Chuck Sudetic (3 January 1992). "Yugoslav Factions Agree to U.N. Plan to Halt Civil War". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Carol J. Williams (29 January 1992). "Roadblock Stalls U.N.'s Yugoslavia Deployment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Antun Jelić (December 1994). "Child casualties in a Croatian community during the 1991-2 war". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 71 (6). BMJ Group: 540–2. doi:10.1136/adc.71.6.540. ISSN 0003-9888. PMC 1030096. PMID 7726618.

- ^ Zdravko Tomac (15 January 2010). "Strah od istine" [Fear of the Truth]. Portal of Croatian Cultural Council (in Croatian). Hrvatsko kulturno vijeće. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Dean E. Murphy (8 August 1995). "Croats Declare Victory, End Blitz". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Chris Hedges (16 January 1998). "An Ethnic Morass Is Returned to Croatia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Zakon o područjima županija, gradova i općina u Republici Hrvatskoj" [Territories of Counties, Cities and Municipalities of the Republic of Croatia Act]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). 28 July 2006. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ a b Dragutin Babić (March 2003). "Etničke promjene u strukturi stanovništva slavonskih županija između dvaju popisa (1991.–2001.)" [Ethnic changes in the population structure of counties in Slavonia between two censuses (1991–2001)]. Migracijske I Etničke Teme (in Croatian). 19 (1). The Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies. ISSN 1333-2546. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Ankica Barbir-Mladinović (29 September 2010). "U dijelu Hrvatske BDP na razini devedesetih" [In a part of Croatia, GDP hits 1990s level]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Croatian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ "Opći podaci o Brodsko-posavskoj županiji" [General information on Brod-Posavina County] (in Croatian). Brod-Posavina County. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Local self-government". Osijek-Baranja County. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Opći podaci o županiji" [General information on the county] (in Croatian). Požega-Slavonia County. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Virovitičko-podravska županija kroz povijest" [Virovitica-Podravina County through history] (in Croatian). Virovitica-Podravina County. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Osnovni podaci" [The basic information] (in Croatian). Vukovar-Syrmia County. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ "Nacionalno izviješće Hrvatska" [Croatia National Report] (PDF) (in Croatian). Council of Europe. January 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "2010 – Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Croatia" (PDF). Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "Census 2011 First Results". Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 29 June 2011. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Novi vijek" [Modern history] (in Croatian). Ministry of Culture (Croatia). Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ Silvana Fable (12 May 2011). "Jakovčić predložio Hrvatsku u četiri regije – Slavonija i Baranja, Istra, Dalmacija i Zagreb" [Jakovčić proposes Croatia of four regions – Slavonija and Baranja, Istria, Dalmatia and Zagreb]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Slavonija i Baranja – Riznica tradicije, ljepota prirode i burne povijesti" [Slavonia and Baranya – Treasuring tradition, natural heritage and tumultuous history]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 7 August 2010. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Anita Blagojević (December 2008). "Zemljopisno, povijesno, upravno i pravno određenje istočne Hrvatske – korijeni suvremenog regionalizma" [Geographic, historical, administrative and legal definition of the eastern Croatia - roots of contemporary regionalism]. Collected Papers of the Law Faculty of the University of Rijeka (in Croatian). 29 (2). Faculty of Law University of Rijeka: 1150. ISSN 1330-349X.

- ^ "Drugo, trece i cetvrto nacionalno izvješće Republike Hrvatske prema Okvirnoj konvenciji Ujedinjenih naroda o promjeni klime (UNFCCC)" [The second, third and fourth national report of the Republic of Croatia pursuant to the United Nations Framework Climate Change Convention (UNFCCC)] (PDF) (in Croatian). Ministry of Construction and Spatial Planning (Croatia). November 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Milos Stankoviansky; Adam Kotarba (2012). Recent Landform Evolution: The Carpatho-Balkan-Dinaric Region. Springer. pp. 14–18. ISBN 978-94-007-2447-1. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Dirk Hilbers (2008). The Nature Guide to the Hortobagy and Tisza River Floodplain, Hungary. Crossbill Guides Foundation. p. 16. ISBN 978-90-5011-276-5. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Bruno Saftić; Josipa Velić; Orsola Sztanó; Györgyi Juhász; Željko Ivković (June 2003). "Tertiary Subsurface Facies, Source Rocks and Hydrocarbon Reservoirs in the SW Part of the Pannonian Basin (Northern Croatia and South-Western Hungary)". Geologia Croatica. 56 (1). Croatian Geological Institute: 101–122. Bibcode:2003GeolC..56..101S. doi:10.4154/232. ISSN 1333-4875. S2CID 34321638.

- ^ Jakob Pamić; Goran Radonić; Goran Pavić. "Geološki vodič kroz park prirode Papuk" [Geological guide to the Papuk Nature Park] (PDF) (in Croatian). Papuk Geopark. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Vlasta Tari-Kovačić (2002). "Evolution of the northern and western Dinarides: a tectonostratigraphic approach" (PDF). EGU Stephan Mueller Special Publication Series. 1 (1). Copernicus Publications: 223–236. Bibcode:2002SMSPS...1..223T. doi:10.5194/smsps-1-223-2002. ISSN 1868-4556. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Izviješće o stanju okoliša Vukovarsko-srijemske županije" [Report on environmental conditions in the Vukovar-Syrmia County] (PDF). Službeni glasnik Vukovarsko-srijemske županije (in Croatian). 14 (18). Vukovar-Syrmia County: 1–98. 27 December 2006. ISSN 1846-0925. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ "Prostorni plan parka prirode "Kopački Rit"" [Kopački Rit Nature Park spatial plan] (PDF) (in Croatian). Osijek: Ministry of Environment and Nature Protection (Croatia). February 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Branko Nadilo (2010). "Zgrada agencije za vodne putove i športske udruge Vukovara" [Waterways agency building and sport associations of the city of Vukovar] (PDF). Građevinar (in Croatian). 62 (6). Croatian Association of Civil Engineers: 529–538. ISSN 0350-2465. Retrieved 14 June 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Pravilnik o područjima podslivova, malih slivova i sektora" [Ordinance on areas of sub-catchments, minor catchments and sectors]. Narodne Novine (in Croatian). 11 August 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ "Apsolutno najniža temperatura zraka u Hrvatskoj" [The absolute lowest air temperature in Croatia] (in Croatian). Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service. 3 February 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ Milan Sijerković (2008). "Ljetne vrućine napadaju" [Hot summer weather pushes on]. INA Časopis. 10 (40). INA: 88–92. Retrieved 13 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ivana Barišić (14 February 2012). "Vojska sa 64 kilograma eksploziva razbila led na Dravi kod Osijeka" [Army breaks Drava River ice near Osijek using 64 kilograms of explosives]. Večernji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ "Ledolomci na Dunavu i Dravi" [Icebreakers on Danube and Drava] (in Croatian). Croatian Radiotelevision. 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ "Popis stanovništva 2001" [2001 Census]. Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Mužić (2007), pp. 249–293

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt (2003). Ethnic groups and population changes in twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe. M.E. Sharpe. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Ivan Jurković (September 2003). "Klasifikacija hrvatskih raseljenika za trajanja osmanske ugroze (od 1463. do 1593.)" [Classification of Displacees Among Croats During the Ottoman Peril (from 1463 till 1593)]. Migracijske I Etničke Teme (in Croatian). 19 (2–3). Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies: 147–174. ISSN 1333-2546. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt (2003). Ethnic groups and population changes in twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 288–295. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Jelena Lončar (22 August 2007). "Iseljavanje Hrvata u Amerike te Južnu Afriku" [Migrations of Croats to the Americas and the South Africa] (in Croatian). Croatian Geographic Society. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Božena Vranješ-Šoljan (April 1999). "Obilježja demografskog razvoja Hrvatske i Slavonije 1860. – 1918" [Characteristics of demographic development of Croatia and Slavonia 1860–1918]. Radovi Zavoda Za Hrvatsku Povijest (in Croatian). 31 (1). University of Zagreb, Croatian History Institute: 41–53. ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Ivan Balta (October 2001). "Kolonizacija u Slavoniji od početka XX. stoljeća s posebnim osvrtom na razdoblje 1941.-1945. godine" [The colonisation in Slavonia between 1941 and 1945 (English summary title)]. Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru (in Croatian) (43). Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. ISSN 1330-0474.

- ^ Charles W. Ingrao; Franz A. J. Szabo (2008). The Germans and the East. Purdue University Press. p. 357. ISBN 978-1-55753-443-9. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Migrations in the territory of former Yugoslavia from 1945 until present time" (PDF). University of Ljubljana. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Hrvatsko iseljeništvo u Kanadi" [Croatian diaspora in Canada] (in Croatian). Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration (Croatia). Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Hrvatsko iseljeništvo u Australiji" [Croatian diaspora in Australia] (in Croatian). Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration (Croatia). Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Stanje hrvatskih iseljenika i njihovih potomaka u inozemstvu" [Balance of Croatian Emigrants and their Descendants Abroad] (in Croatian). Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration (Croatia). Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Županijska razvojna strategija Brodsko-posavske županije" [County development strategy of the Brod-Posavina County] (PDF) (in Croatian). Slavonski Brod: Brod-Posavina County. March 2011. pp. 27–40. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Informacija o stanju gospodarstva Vukovarsko-srijemske županije" [Information on state of economy of the Vukovar-Srijem County] (PDF) (in Croatian). Vukovar-Srijem County. September 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "County economy". Osijek-Baranja County. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Gospodarstvo Virovitičko-podravske županije" [Economy of Virovitica-Podravina County] (in Croatian). Croatian Employment Service. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Gospodarstvo Brodsko-posavske županije" [Economy of Brod-Posavina County] (in Croatian). Brod-Posavina County. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Gospodarski profil županije" [Economic profile of the county] (in Croatian). Požega-Slavonia County. Archived from the original on 3 December 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT FOR REPUBLIC OF CROATIA, STATISTICAL REGIONS AT LEVEL 2 AND COUNTIES, 2008". Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 11 February 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Transport: launch of the Italy-Turkey pan-European Corridor through Albania, Bulgaria, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Greece". European Union. 9 September 2002. Retrieved 6 September 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Priručnik za unutarnju plovidbu u Republici Hrvatskoj" [Manual of inland waterways navigation in the Republic of Croatia] (PDF) (in Croatian). Centar za razvoj unutarnje plovidbe d.o.o. December 2006. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Popis poljoprivrede 2003" [2003 Agricultural Census] (in Croatian). Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Bruto domaći proizvod za Republiku Hrvatsku, prostorne jedinice za statistiku 2. razine i županije od 2000. do 2006" [Gross domestic product of the Republic of Croatia, 2nd tier spatial units and counties, from 2000 to 2006]. Priopćenja 2002–2007 (in Croatian). 46 (12.1.5). Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 3 July 2009. ISSN 1334-0565.