Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Svalbard

View on Wikipedia

Svalbard (/ˈsvɑːlbɑːr(d)/ SVAHL-bar(d),[4] Urban East Norwegian: [ˈsvɑ̂ːɫbɑr]), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it lies about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range from 74° to 81° north latitude, and from 10° to 35° east longitude. The largest island is Spitsbergen (37,673 km2), followed in size by Nordaustlandet (14,443 km2), Edgeøya (5,073 km2), and Barentsøya (1,288 km2). Bjørnøya or Bear Island (178 km2) is the most southerly island in the territory, situated some 147 km south of Spitsbergen. Other small islands in the group include Hopen to the southeast of Edgeøya, Kongsøya and Svenskøya in the east, and Kvitøya to the northeast. The largest settlement is Longyearbyen, situated in Isfjorden on the west coast of Spitsbergen.[5]

Key Information

Whalers who sailed far north in the 17th and 18th centuries used the islands as a base; subsequently, the archipelago was abandoned.[6][7] Coal mining started at the beginning of the 20th century, and several permanent communities such as Pyramiden and Barentsburg were established.[8] The Svalbard Treaty of 1920 recognizes Norwegian sovereignty, and the Norwegian Svalbard Act of 1925 made Svalbard a full part of the Kingdom of Norway. The Svalbard Treaty established Svalbard as a free economic zone and restricts the military use of the archipelago. The Norwegian Store Norske and the Russian Arktikugol remain the only mining companies in place.

Research and tourism have become important supplementary industries, with the University Centre in Svalbard and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault playing critical roles in the local economy. Apart from Longyearbyen, other settlements include the Russian mining community of Barentsburg, the Norwegian research station of Ny-Ålesund, the Polish research station of Hornsund, the settlement of Nybyen, and the Swedish-Norwegian mining outpost of Sveagruva (which closed in 2020).[9] Other settlements lie farther north, but are populated only by rotating groups of researchers. No roads connect the settlements; instead, snowmobiles, aircraft, and boats provide inter-settlement transport. Svalbard Airport serves as the main gateway.

Approximately 60% of the archipelago is covered with glaciers, and the islands feature many mountains and fjords.[10] The archipelago has an Arctic climate, although with significantly higher temperatures than other areas at the same latitude due to the impact of the tail end of the Gulf Stream from the Atlantic Ocean. The flora has adapted to take advantage of the long period of midnight sun to compensate for the polar night.[11] Many seabirds use Svalbard as a breeding ground, and it is home to polar bears, reindeer, the Arctic fox, and certain marine mammals. Seven national parks and 23 nature reserves cover two-thirds of the archipelago, protecting the largely untouched fragile environment. Norway announced new regulations regarding tourism in February 2024, including a maximum of 200 people on a ship, to protect flora and fauna in Svalbard.[12]

While part of the Kingdom of Norway since 1925, Svalbard is not part of geographical Norway; administratively, the archipelago is not part of any Norwegian county, but forms an unincorporated area.[13] This means that it is administered directly by the Norwegian government through an appointed governor, and is a special jurisdiction subject to the Svalbard Treaty that is outside of the Schengen Area, the Nordic Passport Union, and the European Economic Area. Svalbard and Jan Mayen are collectively assigned the ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 country-code "SJ". Both areas are administered by Norway, though they are separated by a distance of over 950 kilometres (510 nautical miles) and have very different administrative structures.

Etymology

[edit]

The name Svalbard was officially adopted for the archipelago by Norway under the 1925 Svalbard Act which formally annexed it.[14] The former name Spitsbergen was thenceforth restricted to the main island. In 1827, Baltazar Keilhau first proposed that the Old Norse toponym Svalbarði, found in medieval Icelandic sources, referred to Spitsbergen.[14][15] Keilhau's theory was revived by Gustav Storm in 1890 and Gunnar Isachsen in 1907, at a time when ancient Norse connection to the land would help modern Norway's contested claim to sovereignty.[14][15] Svalbard is a modern Norwegian analogue of Svalbarði, which in turn derives from svalr ('cold') and barð ('edge', 'ridge', 'turf', 'beard').[15]

The Icelandic Annals record that Svalbarði was discovered in 1194, while the Landnámabók places it four days' sailing north of Langanes.[15] The word dægr "day" might mean either 12 or 24 hours; Isachsen took the latter interpretation, thus discounting Jan Mayen as Svalbarði.[15] Cultural studies academic Roald Berg says Svalbarði more likely referred to part of Greenland, but the 1925 renaming cemented Norwegian sovereignty as recognised by the 1920 Spitsbergen Treaty (now the Svalbard Treaty).[14]

The name Spitsbergen originated with Dutch navigator and explorer Willem Barentsz, who in 1596 described the "pointed mountains" or, in Dutch, spitse bergen that he saw on the west coast of the main island. Barentsz did not recognize that he had discovered an archipelago, and consequently the name Spitsbergen long remained in use both for the main island and for the archipelago as a whole.[16] Later the main island was sometimes distinguished as West Spitsbergen. The spelling Spitzbergen, with z instead of s, derives from German.[17]

Geography

[edit]

The Svalbard Treaty of 1920[18] defines Svalbard as all islands, islets, and skerries from 74° to 81° north latitude, and from 10° to 35° east longitude.[19][20] The land area is 61,022 km2 (23,561 sq mi), and dominated by the island of Spitsbergen, which constitutes more than half the archipelago, followed by Nordaustlandet and Edgeøya.[21]

All settlements are on Spitsbergen, except the meteorological outposts on Bjørnøya and Hopen.[18] The Norwegian state took possession of all unclaimed land, or 95.2% of the archipelago, at the time the Svalbard Treaty entered into force; Store Norske, a Norwegian coal mining company, owns 4%, Arktikugol, a Russian coal mining company, owns 0.4%, while other private owners hold 0.4%.[22]

As Svalbard is north of the Arctic Circle, it experiences midnight sun in summer and polar night in winter. At 74° north, the midnight sun lasts 99 days and polar night 84 days, while the respective figures at 81° north are 141 and 128 days.[23] In Longyearbyen, midnight sun lasts from 20 April until 23 August, and polar night lasts from 26 October to 15 February.[19] In winter, the combination of full moon and reflective snow can give additional light.[23]

Due to the Earth's tilt and the high latitude, Svalbard has extensive twilights. Longyearbyen sees the first and last day of polar night having seven and a half hours of twilight, whereas the perpetual light lasts for two weeks longer than the midnight sun.[24][25] On the summer solstice, the sun bottoms out at 12° sun angle in the middle of the night, being much higher during night than in mainland Norway's polar light areas.[26] However, the daytime maximum sun angle at the summer solstice is approximately 35°.

Glacial ice covers 36,502 km2 (14,094 sq mi) or 60% of Svalbard; 30% is barren rock while 10% is vegetated.[27] The largest glacier is Austfonna (8,412 km2 or 3,248 sq mi) on Nordaustlandet, followed by Olav V Land and Vestfonna. During summer, it is possible to ski from Sørkapp in the south to the north of Spitsbergen, with only a short distance not being covered by snow or glacier. Kvitøya is 99.3% covered by glacier.[28]

The landforms of Svalbard were created through repeated ice ages, when glaciers cut the former plateau into fjords, valleys, and mountains.[29] The tallest peak is Newtontoppen (1,717 m or 5,633 ft), followed by Perriertoppen (1,712 m or 5,617 ft), Ceresfjellet (1,675 m or 5,495 ft), Chadwickryggen (1,640 m or 5,380 ft), and Galileotoppen (1,637 m or 5,371 ft). The longest fjord is Wijdefjorden (108 km or 67 mi), followed by Isfjorden (107 km or 66 mi), Van Mijenfjorden (83 km or 52 mi), Woodfjorden (64 km or 40 mi), and Wahlenbergfjorden (46 km or 29 mi).[30] Svalbard is part of the High Arctic Large Igneous Province,[31] and experienced Norway's strongest earthquake on 6 March 2009 at magnitude 6.5.[32]

History

[edit]Dutch discovery

[edit]The Dutchman Willem Barentsz made the first discovery of the archipelago in 1596, when he sighted the coast of the island of Spitsbergen while searching for the Northern Sea Route.[33]

The first recorded landing on the islands of Svalbard dates to 1604, when an English ship landed at Bjørnøya, or Bear Island, and started hunting walrus. Annual expeditions soon followed, and Spitsbergen became a base for hunting the bowhead whale from 1611.[34][35] Because of the lawless nature of the area, English, Danish, Dutch, and French companies and authorities tried to use force to keep out other countries' fleets.[36][37]

17th–18th centuries

[edit]

Smeerenburg was one of the first settlements, established by the Dutch in 1619.[38] Smaller bases were also built by the English, Danish, and French. At first, the outposts were merely summer camps, but from the early 1630s, a few individuals started to overwinter. Whaling at Spitsbergen lasted until the 1820s, when the Dutch, British, and Danish whalers moved elsewhere in the Arctic.[39] By the late 17th century, Russian hunters arrived; they overwintered to a greater extent and hunted land mammals such as the polar bear and fox.[40]

Norwegian hunting—mostly for walrus—started in the 1790s. The first Norwegian citizens to reach Spitsbergen proper were a number of Coast Sámi people from the Hammerfest region, who were hired as part of a Russian crew for an expedition in 1795.[41]

19th century

[edit]After the Anglo-Russian War in 1809, Russian activity on Svalbard diminished, and had ceased by the 1820s.[42] Norwegian whaling was abandoned about the same time as the Russians left,[43] but whaling continued around Spitsbergen until the 1830s, and around Bjørnøya until the 1860s.[44]

20th century

[edit]Svalbard Treaty

[edit]By the 1890s, Svalbard had become a destination for Arctic tourism, coal deposits had been found, and the islands were being used as a base for Arctic exploration.[45] The first mining was along Isfjorden by Norwegians in 1899; by 1904, British interests had established themselves in Adventfjorden and started the first year-round operations.[46] Production in Longyearbyen, by US interests, started in 1908;[47] and Store Norske established itself in 1916, as did other Norwegian interests during the First World War, in part by buying US interests.[48]

Discussions to establish the sovereignty of the archipelago commenced in the 1910s,[50] but were interrupted by World War I.[51] On 9 February 1920, following the Paris Peace Conference, the Svalbard Treaty was signed, granting full sovereignty to Norway. However, all signatory countries were granted non-discriminatory rights to fishing, hunting, and mineral resources.[52] The treaty took effect on 14 August 1925, at the same time as the Svalbard Act regulated the archipelago and the first governor, Johannes Gerckens Bassøe, took office.[53]

The archipelago has traditionally been known as Spitsbergen, and the main island as West Spitsbergen. During the 1920s, Norway renamed the archipelago Svalbard, and the main island became Spitsbergen.[54] Kvitøya, Kong Karls Land, Hopen, and Bjørnøya were not regarded as part of the Spitsbergen archipelago.[55] Russians have traditionally called the archipelago Grumant (Грумант).[56] The Soviet Union retained the name Spitsbergen (Шпицберген) to support undocumented claims that Russians were the first to discover the island.[57][58]

In 1928, Italian explorer Umberto Nobile and the crew of the airship Italia crashed on the icepack off the coast of Foyn Island. The subsequent rescue attempts were covered extensively in the press and Svalbard received short-lived fame as a result.[59]

Second World War

[edit]

Svalbard, known to both British and Germans as Spitsbergen, was little affected by the German invasion of Norway in April 1940. The settlements continued to operate as before, mining coal and monitoring the weather.[60][61][62]

In July 1941, following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the Royal Navy reconnoitered the islands with a view to using them as a base of operations to send supplies to north Russia, but the idea was rejected as impractical.[63] Instead, with the agreement of the Soviets and the Norwegian government in exile, in August 1941 the Norwegian and Soviet settlements on Svalbard were evacuated, and facilities there destroyed, in Operation Gauntlet.[64][65] However, the Norwegian government in exile decided it would be important politically to establish a garrison in the islands, which was done in May 1942 during Operation Fritham.[66]

Meanwhile, the Germans responded to the destruction of the weather station by establishing a reporting station of their own, codenamed "Banso", in October 1941.[67] They were chased away in October by a visit from what the Germans mistook to be four British warships, but later returned.[68] A second station, "Knospe", was established at Ny-Ålesund in 1941, remaining until 1942. In May 1942, after the arrival of the Fritham force, the German unit at Banso was evacuated.[69]

In September 1943 in Operation Zitronella a German task force, which included the battleship Tirpitz, was sent to attack the garrison and destroy the settlements at Longyearbyen and Barentsburg.[70] This was achieved, but had little long-term effect: after their departure the Norwegians returned and re-established their presence.[71]

In September 1944, the Germans set up their last weather station, Operation Haudegen in Nordaustlandet; it functioned until after the German surrender.[72] On 4 September 1945, the soldiers were picked up by a Norwegian seal hunting vessel and surrendered to its captain. This group of men were the last German troops to surrender after the Second World War.[73]

After the war, the Soviet Union proposed common Norwegian and Soviet administration and military defence of Svalbard. This was rejected in 1947 by Norway, which two years later joined NATO. The Soviet Union retained high civilian activity on Svalbard, in part to ensure that the archipelago was not used by NATO.[74]

Post-war

[edit]

After the war, Norway re-established operations at Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund,[75] while the Soviet Union established mining in Barentsburg, Pyramiden, and Grumant.[76] The mine at Ny-Ålesund had several fatal accidents, killing 71 people while it was in operation from 1945 to 1954 and from 1960 to 1963. The Kings Bay Affair, caused by the 1962 accident killing 21 workers, forced Gerhardsen's Third Cabinet to resign.[77][78]

From 1964, Ny-Ålesund became a research outpost, and a facility for the European Space Research Organisation.[79] Petroleum test drilling was started in 1963 and continued until 1984, but no commercially viable fields were found.[80] From 1960, regular charter flights were made from the mainland to a field at Hotellneset;[81] in 1975, Svalbard Airport, Longyearbyen opened, allowing year-round services.[82]

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union supplied about two-thirds of the population on the islands (Norwegians making up the remaining third) with the population of the archipelago slightly under 4,000.[76] Russian activity has diminished considerably since then, falling from 2,500 to 450 people from 1990 to 2010.[83][84] Grumant was closed after it was depleted in 1962.[76]

Pyramiden was closed in 1998.[85] Coal exports from Barentsburg ceased in 2006 because of a fire,[86] but resumed in 2010.[87] The Russians experienced two air accidents: Vnukovo Airlines Flight 2801 (1996), which killed 141 people,[88] and the Heerodden helicopter accident (2008), which killed three people.[89]

Longyearbyen remained purely a company town until 1989 when utilities, culture, and education was separated into Svalbard Samfunnsdrift.[90] In 1993, it was sold to the national government and the University Centre was established.[91] Through the 1990s, tourism increased and the town developed an economy independent of Store Norske and mining.[92] Longyearbyen was incorporated on 1 January 2002, adopting a community council.[90]

On 30 June 2025 the Mine 7, the last Norwegian coal mine in Svalbard, was closed, though the mine in Barentsburg continued operation.[93]

Population

[edit]Demographics

[edit]In 2016, Svalbard had a population of 2,667, of which 423 were Russian and Ukrainian, 10 Polish, and 322 other non-Norwegians living in Norwegian settlements.[21] The largest non-Norwegian groups in Longyearbyen in 2005 were from Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, and Thailand.[84]

In mid-2023, there were 3,094 inhabitants on Spitsbergen, including 2,465 at Longyearbyen, 130 at Ny-Ålesund, and 10 (Polish) at the Hornsund (Isbjørnhamna) research station; there were 440 Russians at Barentsburg and some 50 at Pyramiden. There were no inhabitants on the other islands except for nine at the meteorological station on Bear Island (at Herwighamna) and four at the one on Hopen.[citation needed]

As of January 2025, there were 1691 Norwegians and 865 non-Norwegians living in Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund;[94] there were 297 residents of Barentsburg and Pyramiden; and there were 10 residents of Hornsund.[95]

Settlements

[edit]Longyearbyen is the largest settlement on the archipelago; it is the seat of the governor and the only incorporated town. The town features an airport, hospital, primary and secondary school, university, sports center with a swimming pool, library, culture center, cinema,[86] bus transport, hotels, a bank,[96] and several museums.[97] The newspaper Svalbardposten is published weekly.[98] Very little mining activity remains at Longyearbyen; coal mines at Sveagruva and Lunckefjellet suspended operations in 2017 and were closed permanently in 2020.[99][100]

Ny-Ålesund is a permanent research settlement in the northwest of Spitsbergen and the northernmost functional civilian settlement in the world. Formerly a mining town, it is still a company town operated by the Norwegian state-owned Kings Bay company. While some tourism to the outpost is permitted, Norwegian authorities limit access to minimize impact on scientific work.[86] Ny-Ålesund has a winter population of 35 and a summer population of 180.[101] The Norwegian Meteorological Institute has outposts at Bjørnøya and Hopen, with nine and four inhabitants respectively. Both can also house temporary research staff.[86] Poland operates the Polish Polar Station at Hornsund, with ten permanent residents.[86]

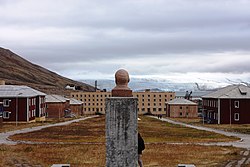

The Russian (formerly Soviet) mining settlement of Pyramiden was abandoned in 1998, leaving Barentsburg as the only permanently inhabited Russian settlement. It is a company town: all facilities are owned by Arktikugol, which operates a coal mine. In addition to the mining facilities, Arktikugol has opened a hotel and souvenir shop, catering to tourists taking day trips or hikes from Longyearbyen.[86]

The village features a school, library, sports center, community center, swimming pool, farm, and greenhouse. Pyramiden features similar facilities; both are built in typical post-World War II Soviet architectural and planning style and contain the world's two most northerly Lenin statues and other socialist realist art.[102] As of 2023[update], about 48 workers are stationed in the largely abandoned Pyramiden to maintain local infrastructure and run its hotel, which has been re-opened to tourism.[103][104]

Religion

[edit]Most of the population is Christian. Most of the Norwegians are affiliated with the Church of Norway. Russian and Ukrainian population belongs to the Orthodox Church. Catholics on the archipelago are pastorally served by the Territorial Prelature of Tromsø.[105]

Politics

[edit]

The Svalbard Treaty of 1920 established full Norwegian sovereignty over the archipelago. The islands are, unlike the Norwegian Antarctic territories, a part of the Kingdom of Norway and not a dependency. The treaty came into effect in 1925, following the Svalbard Act. All forty-eight signatory countries of the treaty have the right to conduct commercial activities on the archipelago without discrimination, although all activity is subject to Norwegian legislation. The treaty limits Norway's right to collect taxes to that of financing services on Svalbard.[20][106] Therefore, Svalbard has a lower income tax than mainland Norway, and there is no value added tax. There is a separate budget for Svalbard to ensure compliance.[107]

Svalbard is not governed by Norway's policies on migration and does not issue visas or residence permits itself.[108][109] Foreigners do not need a visa or work and residence permits from the Norwegian authorities to travel to Svalbard. However, foreign citizens with a visa requirement for the Schengen Area must have a Schengen visa when travelling to and from Svalbard via mainland Norway.[110]

The Svalbard Act established the institution of the Governor of Svalbard (Norwegian: Sysselmester, formerly Sysselmannen), who holds the responsibility as both county governor and chief of police, as well as holding other authority granted from the executive branch. Duties include environmental policy, family law, law enforcement, search and rescue, tourism management, information services, contact with foreign settlements, and judge in some areas of maritime inquiries and judicial examinations—albeit never in the same cases as acting as police.[111][112] Since 2021, Lars Fause has been governor. The institution is subordinate to the Ministry of Justice and the Police, but reports to other ministries in matters within their portfolio.[113]

Since 2002, Longyearbyen Community Council has had many of the same responsibilities of a municipality, including utilities, education, cultural facilities, fire department, roads, and ports.[92] No care or nursing services are available, nor are welfare payments available. Norwegian residents retain pension and medical rights through their mainland municipalities.[114] The hospital is part of University Hospital of North Norway, while the airport is operated by state-owned Avinor. Ny-Ålesund and Barentsburg remain company towns with all infrastructure owned by Kings Bay and Arktikugol.[92] Other public offices with presence on Svalbard are the Norwegian Directorate of Mining, the Norwegian Polar Institute, the Norwegian Tax Administration, and the Church of Norway.[115] Svalbard is subordinate to Nord-Troms District Court and Hålogaland Court of Appeal, both in Tromsø.[116]

Although Norway is part of the European Economic Area (EEA) and the Schengen Agreement, Svalbard is not part of the Schengen Area or the EEA.[117] Non-EU and non-Nordic Svalbard residents do not need Schengen visas for Svalbard itself, but those travelling via mainland Norway require visas to pass through Norway. People without a source of income can be rejected by the governor.[118]

No one is required to have a visa or residence permit on Svalbard. Regardless of citizenship, persons can live and work in Svalbard indefinitely. The Svalbard Treaty grants treaty nationals equal right of abode as Norwegian nationals. So far, non-treaty nationals have been admitted visa-free as well. While there is no visa requirement, everyone must meet certain requirements in order to stay in Svalbard. These requirements are governed by a separate policy called "Regulations relating to rejection and expulsion of persons from Svalbard".[119] Among the requirements is that residents must have the means to be able to reside on Svalbard. These requirements apply to both foreigners and Norwegian citizens, and the Governor of Svalbard may reject persons who do not meet the requirements.[110][clarification needed][120][121] Russia retains a consulate in Barentsburg.[122]

In September 2010, a treaty was signed between Russia and Norway fixing the boundary between the Svalbard archipelago and the Novaya Zemlya archipelago. Increased interest in petroleum exploration in the Arctic raised interest in a resolution of the dispute. The agreement takes into account the relative positions of the archipelagos, rather than being based simply on northward extension of the continental border of Norway and Russia.[123]

Defense

[edit]Svalbard constitutes a demilitarized zone, as the treaty prohibits the establishment of military installations on the islands. However, since the treaty recognizes Norway as the sovereign power in the archipelago, the country claims exclusive rights in the maritime zone around the islands; rights which Norway argues permit the Norwegian Coast Guard to conduct fishery and other maritime surveillance and enforcement in these waters.[20][106][124] Certain other parties to the treaty (including Spain, Iceland and particularly Russia) argue that the Treaty provides them with extensive rights beyond Svalbard's territorial sea.[125] Norway claims an exclusive economic zone of more than three-quarters of a million square kilometers around Svalbard, though "Russia does not recognize Norwegian functional rights with respect to the Svalbard Fisheries Protection Area".[126]

In the 2020s, in order to strengthen Norway's ability to enforce its claims around the archipelago, the Norwegian Coast Guard embarked on a significant modernization program. As of 2023, the Coast Guard is replacing its older Nordkapp-class offshore patrol vessels with significantly larger ice-capable ships, each displacing just under 10,000 tonnes. The three new Jan Mayen-class offshore patrol vessels are armed with a 57 mm (2.2 in) main gun and are capable of operating up to two medium-sized helicopters. The ships have a maximum speed of 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) with more than 60 days endurance and the complement is up to 100 people.[127] The first ship, KV Jan Mayen, was delivered in early 2023.[128] These vessels will complement NoCGV Svalbard which predominantly serves Svalbard and the surrounding waters. In 2023, Norway also announced the acquisition of six MH-60R helicopters which are to be initially deployed with the Coast Guard, though they are to be prepared to be equipped for anti-submarine operations as well.[129] The Royal Norwegian Navy patrols waters of the Svalbard Archipelago at least once a year with a Fridtjof Nansen-class frigate.[130]

The Royal Norwegian Air Force fleet of Boeing P-8 Poseidons stationed at Evenes Air Station on the mainland have capacity for surveillance of the Svalbard Archipelago as part of the surveillance of the Barents Sea.[131][132] The F-35s of the Royal Norwegian Air Force stationed at Evenes Air Station has range to patrol over parts of the Svalbard Archipelago, and could also be stationed further north at Banak Air Station if deemed necessary.[citation needed]

With the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, tensions in the Arctic have increased. In January 2022, an undersea telecommunications cable connecting Svalbard with mainland Norway was damaged. Norwegian suspicions fell on a Russian trawler as the only vessel in the area at the time. The investigation was nevertheless reported as inconclusive. In 2022, Russia announced new investment plans to support its presence at Barentsburg and Pyramiden.[133]

Economy

[edit]The three main industries on Svalbard are coal mining, tourism, and research. In 2007, there were 484 people working in the mining sector, 211 people working in the tourism sector, and 111 people working in the education sector. The same year, the mining yielded revenues of 2.008 billion Norwegian kroner (US$227,791,078), tourism 317 million kroner (US$35,967,202), and research 142 million kroner (US$16,098,404).[92][134]

In 2006, the average income for economically active people was 494,700 kroner, 23% higher than on the mainland.[135] Almost all housing is owned by the various employers and institutions and rented to their employees; there are only a few privately owned houses, most of which are recreational cabins. Because of this, it is difficult to live on Svalbard without working for an established institution.[118]

Since the resettlement of Svalbard in the early 20th century, coal mining has been the dominant commercial activity. Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, a subsidiary of the Norwegian Ministry of Trade and Industry, operates Svea Nord in Sveagruva and Mine 7 in Longyearbyen. The former produced 20 million tonnes from the period 2001–2009, while the latter uses 35% of its output to fuel the Longyearbyen Power Station.[136] In March 2020, the Sveagruva mining settlement was shut down due to budget related issues and efforts to clean up after coal mining in Svalbard.[137]

Since 2007, there has not been any significant mining by the Russian state-owned Arktikugol in Barentsburg.[92] The Gruve 7 mine shut down in June 2025.[93][138]

There has been test drilling for petroleum on land, but these did not give satisfactory results for permanent operation. Norwegian authorities do not allow offshore petroleum activities for environmental reasons, and the land formerly test-drilled have been protected as natural reserves or national parks.[92] In 2011, a 20-year plan to develop offshore oil and gas resources around Svalbard was announced.[139]

Svalbard has historically been a base for both whaling and fishing. Norway claimed a 200-nautical-mile (370-kilometre) exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around Svalbard in 1977,[22] with 31,688 square kilometres (9,239 square nautical miles) of internal waters and 770,565 square kilometres (224,661 square nautical miles) of EEZ.[140] Norway retains a restrictive fisheries policy in the zone,[22] and the claims are disputed by Russia.[18]

Tourism is focused on the environment and is centered on Longyearbyen. Activities include hiking, kayaking, walks through glacier caves, and snowmobile and dog-sled safaris. Cruise ships generate a significant portion of the traffic, including both stops by offshore vessels and expeditionary cruises starting and ending in Svalbard. Traffic is strongly concentrated between March and August; overnight stays have quintupled from 1991 to 2008, when there were 93,000 overnight stays.[92]

In February 2024, Norway announced limits on tourism to favor protection of flora and fauna in the archipelago. Now, ships are limited to 200 passengers in protected areas, among other regulations, many of which concern the breaking of fast ice, use of vehicles on sea ice after 1 March, and marine traffic near walrus areas. There are 43 defined landing spots.[12]

The Arctic World Archive, a huge digital archiving concern run by Norwegian private company Piql and the state-owned coal-mining company Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, opened in March 2017.[141] In mid-2020, it acquired its biggest customer in the form of GitHub, a subsidiary of Microsoft.[142]

One source of income for the area was, until 2015, visiting cruise ships. The Norwegian government became concerned about large numbers of cruise ship passengers suddenly landing at small settlements such as Ny-Ålesund, which is conveniently close to the barren-yet-picturesque Magdalena Fjord. With the increasing size of the larger ships, up to 2,000 people can potentially appear in a community that normally numbers less than 40. As a result, the government severely restricted the size of cruise ships that may visit.[143]

Unemployment is effectively nonexistent as there is no public assistance.[109]

Science and research

[edit]

Research on Svalbard centers on Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund, the most accessible areas in the high Arctic. The Svalbard Treaty grants permission for any nation to conduct non-military research on Svalbard, resulting in the Polish Polar Station and the Chinese Arctic Yellow River Station, plus Russian facilities in Barentsburg.[144] Concerns have been raised about potential dual use of the Arctic Yellow River Station.[145][146]

The University Centre in Svalbard in Longyearbyen offers undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate courses to 350 students in various arctic sciences, particularly biology, geology, and geophysics. Courses are provided to supplement studies at mainland universities; there are no tuition fees and courses are held in English, with Norwegian and international students equally represented.[91]

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is a seedbank to store seeds from as many of the world's crop varieties and their botanical wild relatives as possible. A cooperation between the government of Norway and the Global Crop Diversity Trust, the vault is cut into rock near Longyearbyen, keeping it at a natural −6 °C (21 °F) and refrigerating the seeds to −18 °C (0 °F).[147][148]

The Svalbard Undersea Cable System is a 1,440 km (890 mi) fibre optic line from Svalbard to Harstad, needed for communicating with polar orbiting satellites through Svalbard Satellite Station and installations in Ny-Ålesund.[149][150]

Transport

[edit]

In Longyearbyen, Barentsburg, and Ny-Ålesund, there are road networks, but they do not connect with each other. Off-road motorized transport is prohibited on bare ground in Svalbard, but snowmobiles are used extensively during winter—both for commercial and recreational activities. Transport from Longyearbyen to Barentsburg (45 km or 28 mi) and Pyramiden (100 km or 62 mi) is possible by snowmobile in winter, or by ship all year round. All settlements have ports and Longyearbyen has a bus system.[151]

Svalbard Airport, 3 kilometres (2 mi) from Longyearbyen, is the only airport offering air transport off the archipelago. Scandinavian Airlines has daily scheduled services to Tromsø and Oslo. Low-cost carrier Norwegian Air Shuttle also has a service between Oslo and Svalbard, operating three or four times a week; there are also irregular charter services to Russia.[152] Finnair operated service from Helsinki, operating three times per week between June and August 2016, but Norwegian authorities disallowed this route, citing the 1978 bilateral agreement on air traffic between Finland and Norway.[153][154][155]

Lufttransport provides regular corporate charter services from Longyearbyen to Ny-Ålesund Airport, Hamnerabben, and Svea Airport for Kings Bay and Store Norske. These flights are generally not available to the public.[156] There are heliports in Barentsburg and Pyramiden, and helicopters are frequently used by the governor and to a lesser extent the mining company Arktikugol.[157]

Climate

[edit]

The climate of Svalbard is dominated by its high latitude, with the average daily mean summer temperature at 4 to 7 °C (39 to 45 °F) (1991–2020 averages), and January averages at −13 to −9 °C (9 to 16 °F) (1991–2020). The more southern Bear Island has January mean temperatures as mild as −4.6 °C (24 °F) in the 1991–2020 base period.[158]

The West Spitsbergen Current, the northernmost branch of the North Atlantic Current system, moderates Svalbard's temperatures, particularly during winter. Winter temperatures in Svalbard are up to 20 °C (36 °F) higher than those at similar latitudes in Russia and Canada. The warm Atlantic water keeps the surrounding waters open and navigable most of the year. The interior fjord areas and valleys, sheltered by the mountains, have larger temperature differences than the coast, giving about 2 °C (4 °F) warmer summer temperatures and 3 °C (5 °F) colder winter temperatures.[159]

On the south of Spitsbergen, the temperature is slightly higher than further north and west. During winter, the temperature difference between south and north is typically 5 °C (9 °F), and about 3 °C (5 °F) in summer. Bear Island has average temperatures even higher than the rest of the archipelago.[159]

Svalbard is where cold polar air from the north and mild, wet sea air from the south meet, creating low pressure, changeable weather and strong winds, particularly in winter; in January, a strong breeze is registered 17% of the time at Isfjord Radio, but only 1% of the time in July. In summer, fog is common, particularly off the coast, with visibility under 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) registered 20% of the time in July and 1% of the time in January, at Hopen and Bjørnøya.[160]

Precipitation is frequent, but falls in small quantities, typically less than 400 millimetres (16 in) per year in western Spitsbergen. More rain falls on the uninhabited east side, where there can be more than 1,000 millimetres (39 in).[160] On average, Svalbard has lower humidity than other places in the Arctic Circle. The only places in the Arctic with a lower average are in mainland Norway, Sweden and Finland.[citation needed]

2016 was the warmest year on record at Svalbard Airport, with a remarkable mean temperature of 0.0 °C (32.0 °F), 7.5 °C (13.5 °F) above the 1961–90 average, and more comparable to a location at the Arctic Circle. The coldest temperature of the year was as high as −18 °C (0 °F), warmer than the mean minimum in a normal January, February or March. In the same year, the number of days when there was rainfall equalled the number of days when there was snowfall, a significant deviation from the usual pattern whereby there would be at least twice as many snow days.[161]

Global warming has resulted in noticeable climatic changes on Svalbard. Between 1970 and 2020, the average temperature on Svalbard rose by 4 degrees Celsius, and in the winter months by 7 degrees.[162] On 25 July 2020, a new record temperature of 21.7 °C (71.1 °F) was measured for the Svalbard archipelago, which is also the highest temperature ever recorded in the European part of the High Arctic; in addition, temperatures of over 20 degrees were measured four days in a row in July 2020.[163]

As in large parts of the Arctic, the ice–albedo feedback effects can also be noticed on Svalbard: Due to the substantial ice melt, ice surfaces are transformed into open water, the darker surface of which absorbs more solar energy instead of reflecting it back; as a result, these waters heat up and further ice in the area melts faster and faster, creating more open waters, etc. A temperature increase of between 7 and 10 degrees is expected on Svalbard by the end of the century.[162]

Nature

[edit]

In addition to humans, three primarily terrestrial mammalian species inhabit the archipelago: the Arctic fox, the Svalbard reindeer, and accidentally introduced southern voles, which are found only in Grumant.[164] Attempts to introduce the Arctic hare and the muskox have both failed.[165] There are 15 to 20 types of marine mammals, including: whales, dolphins, seals, walruses, and polar bears.[164]

Polar bears are the iconic symbol of Svalbard, and one of the main tourist attractions.[166] The animals are protected and people moving outside the settlements are required to have appropriate scare devices to ward off attacks. They are also advised to carry a firearm for use as a last resort.[167][168] In August 2011, a British schoolboy was killed and four others were injured by a polar bear.[169] In July 2018, a polar bear was shot dead after it attacked and injured a polar bear guard leading tourists off a cruise ship.[170][171] In August 2020, a Dutch man was killed by a polar bear at a campsite in Longyearbyen. The polar bear was shot dead.[172][173] In 2022, a polar bear attacked a French tourist, who suffered injuries to an arm. The bear left after shots had been fired. It was later euthanised following a professional assessment of its injuries.[174]

As of 2021, Svalbard has around 300 resident[175] polar bears.[176] Svalbard and Franz Joseph Land share a common population of roughly 2,650 polar bears, with Kong Karls Land being the most important breeding ground.[177]

The Svalbard reindeer (R. tarandus platyrhynchus) is a distinct subspecies; although it was previously almost extinct, it can be legally hunted (as can Arctic fox).[164] It has also been documented that polar bears, desperate for food, hunt and successfully kill Svalbard reindeer.[178] There are limited numbers of domesticated animals in the Russian settlements.[179]

About eighty species of bird are found on Svalbard, most of which are migratory.[180] The Barents Sea is among the areas in the world with most seabirds, with about 20 million individuals during late summer. The most common are: little auk, northern fulmar, thick-billed murre, and black-legged kittiwake. Sixteen species are on the IUCN Red List. Particularly Bjørnøya, Storfjorden, Nordvest-Spitsbergen, and Hopen are important breeding ground for seabirds. The Arctic tern has the furthest migration, all the way to Antarctica.[164]

Two songbirds migrate to Svalbard to breed: the snow bunting and the northern wheatear. Rock ptarmigan is the only bird to overwinter.[181] Remains of Predator X (Pliosaurus funkei) from the Jurassic period were discovered here. It is one of the largest dinosaur-era marine reptiles ever found.[182]

Svalbard has permafrost and tundra, including low, middle, and high Arctic vegetation. One hundred and sixty-five species of plants have been found on the archipelago.[164] Only those areas which defrost in the summer are vegetated, which accounts for about 10% of the archipelago.[183] Vegetation is most abundant in Nordenskiöld Land, around Isfjorden and where affected by guano.[184] While there is little precipitation, giving the archipelago a steppe climate, plants still have good access to water because the cold climate reduces evaporation.[160][164] The growing season is very short, and may last only a few weeks.[185] The Svalbard poppy (Papaver dahlianum) is the symbolic flower of Svalbard.[186]

There are seven national parks in Svalbard: Forlandet, Indre Wijdefjorden, Nordenskiöld Land, Nordre Isfjorden Land, Nordvest-Spitsbergen, Sassen-Bünsow Land and Sør-Spitsbergen.[187] The archipelago has fifteen bird sanctuaries, one geotopic protected area and six nature reserves—with Nordaust-Svalbard and Søraust-Svalbard both being larger than any of the national parks. Most of the nature reserves and three of the national parks were created in 1973, with the remaining areas gaining protection in the 2000s.[188] All human traces dating from before 1946 are automatically protected.[167] The protected areas make up 65% of the archipelago.[135] Svalbard is on Norway's tentative list for nomination as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[189]

The total solar eclipse of 20 March 2015 included only Svalbard and the Faroe Islands in the band of totality.[190]

Education

[edit]Longyearbyen School serves ages 6–18. It is the primary/secondary school in the northernmost location on Earth. Once pupils reach ages 16 or 17, most families move to mainland Norway.[191] Barentsburg has its own school serving the Russian community; by 2014 it had three teachers, and its welfare funds had declined.[192] A primary school served the community of Pyramiden in the pre-1998 period.[193]

There is a non-degree offering tertiary educational institution in Longyearbyen,[191] University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), the northernmost tertiary school on Earth.[194]

-

Barentsburg School

Sports

[edit]Association football is the most popular sport in Svalbard. There are three football pitches (one at Barentsburg), but no stadiums because of the small population.[195] There is also an indoor hall adopted for multiple sports including indoor football.[196] Winter sports, such as skiing, snowmobiling and dog sledding, are popular.[197] There is a multi-sport club, Svalbard Turn.[197]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "World Factbook: Svalbard". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ "Svalbard". Central Intelligence Agency. 15 February 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023 – via CIA.gov.

- ^ "Population of Svalbard". Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020. Table 2: Population in the settlements. Svalbard

- ^ "Svalbard – definition of Svalbard in English | Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ Dickie, Gloria (1 June 2021). "The World's Northernmost Town Is Changing Dramatically". Scientific American. 324 (6): 44–53. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0621-44. PMID 39020622. Archived from the original (Original title: "The Polar Crucible") on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ "Whaling – Svalbard Museum". svalbardmuseum.no. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Norum, Roger; Proctor, James (3 May 2018). Svalbard: Spitsbergen, Jan Mayen and Franz Josef Land. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 29–30, 43. ISBN 978-1-78477-047-1.

- ^ Norum, Roger; Proctor, James (3 May 2018). Svalbard: Spitsbergen, Jan Mayen and Franz Josef Land. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-78477-047-1.

- ^ Stange, Rolf (26 February 2020). "Svea Nord is history". Spitsbergen | Svalbard. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Godone, Danilo (4 October 2017). Glacier Evolution in a Changing World. BoD – Books on Demand. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-953-51-3543-2.

- ^ "Svalbard: Svalbard". ncpor.res.in. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Norway: Amendments to environmental regulations in Svalbard". ieu-monitoring.com. Insight EU Monitoring. Archived from the original on 5 May 2025. Retrieved 5 May 2025.

The Norwegian Government has adopted several amendments to the environmental regulations in Svalbard. 'Climate change together with increased activity has resulted in a great pressure on the vulnerable arctic wildlife and nature in Svalbard. We are now tightening the environmental regulations in Svalbard to strengthen the protection of flora and fauna, says the Norwegian minister of climate and environment,' Mr. Andreas Bjelland Eriksen.

- ^ Svalbard, Norway. Svalbard, Norway – historical views – earth watching. (n.d.). European Space Agency

- ^ a b c d Berg, Roald (December 2013). "From "Spitsbergen" to "Svalbard". Norwegianization in Norway and in the "Norwegian Sea", 1820–1925". Acta Borealia. 30 (2): 154–173. doi:10.1080/08003831.2013.843322. S2CID 145567480.

- ^ a b c d e Isachsen, Gunnar (June 1907). "La découverte du Spitsberg par les Normands". La Géographie. 15 (6): 421–432.

- ^ In Search of Het Behouden Huys: A Survey of the Remains of the House of Willem Barentsz on Novaya Zemlya, LOUWRENS HACQUEBORD, p. 250 Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ ... the Archipelago of Spitsbergen, comprising, with Bear Island... all the islands situated between 10deg. and 35deg. longitude East of Greenwich and between 74deg. and 81 deg. latitude North, especially West Spitsbergen..." Treaty concerning the Archipelago of Spitsbergen (1920), p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Svalbard". World Fact Book. Central Intelligence Agency. 15 January 2010. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Svalbard". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b c "Svalbard Treaty". Wikisource. 9 February 1920. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Population in the settlements. Svalbard". Statistics Norway. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.[dead link]

- ^ a b c "7 Industrial, mining and commercial activities". Report No. 9 to the Storting (1999–2000): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 29 October 1999. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b Torkilsen (1984): 96–97

- ^ "Sunrise and sunset in Longyearbyen October 2019". Timeanddate.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Sunrise and sunset in Longyearbyen April 2019". Timeanddate.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Sunrise and sunset in Longyearbyen June". Timeanddate.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 3

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 102–104

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 4–6

- ^ "Geographical survey. Fjords and mountains". Statistics Norway. 22 October 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Maher, Harmon D. Jr. (November 1999). "Research Project on the manifestation of the High Arctic Large Igneous Province (HALIP) on Svalbard". University of Nebraska at Omaha. Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Svalbard hit by major earthquake". The Norway Post. Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 March 2009. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 30. Arlov (1996): 39–40

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 32

- ^ Arlov (1996): 62

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 34–36

- ^ Arlov (1996): 63–67

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 37

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 39

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 40

- ^ Carlheim-Gyllensköld (1900), p. 155

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 44

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 47

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 50

- ^ Arlov (1996): 239

- ^ Arlov (1996): 249

- ^ Arlov (1996): 261

- ^ Arlov (1996): 273

- ^ Jan Oskar Engene (7 February 1996). "Svalbard flag proposal (Norway)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ Arlov (1996): 288

- ^ Arlov (1996): 294

- ^ Arlov (1996): 305–306

- ^ Arlov (1996): 319

- ^ Umbreit (2005): XI–XII

- ^ "Place names of Svalbard". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Arlov (1996): 51

- ^ Fløgstad (2007): 18

- ^ Arlov (1996): 50

- ^ Cross (2002): 84–85; 128–130

- ^ Dege (2004): 289–296

- ^ "World War II: The Weather War". Svalbard Museum. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "World War II – Svalbard Museum". svalbardmuseum.no. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Roskill Vol I: 388

- ^ Arlov (1996): 397

- ^ Roskill Vol I: 389

- ^ Roskill Vol II: 132–133

- ^ Arlov (1996): 400

- ^ Dege (2004): XI

- ^ Dege (2004): XI-XIII

- ^ Arlov (1996): 402–403

- ^ Roskill Vol III: 62

- ^ Selinger, Franz (1 April 1986). "Forsvarsmuseet's Svalbard expeditions 1984 and 1985". GeoJournal. 12 (3): 337–340. doi:10.1007/BF00175022. ISSN 1572-9893.

- ^ Dege (2004): 258

- ^ Arlov (1996): 407–408

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 206

- ^ a b c Torkildsen (1984): 202

- ^ "Kings Bay" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 3 November 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Kings Bay-saken" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Arlov (1996): 412

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 261

- ^ Tjomsland and Wilsberg (1995): 163

- ^ Tjomsland and Wilsberg (1995): 162–164

- ^ "Persons in settlements 1 January. 1990–2005". Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Non-Norwegian population in Longyearbyen, by nationality. Per 1 January. 2004 and 2005. Number of persons". Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Fløgstad (2007): 127

- ^ a b c d e f "10 Longyearbyen og øvrige lokalsamfunn". St.meld. nr. 22 (2008–2009): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 17 April 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Staalesen, Atle (8 November 2010). "Russians restarted coal mining at Svalbard". Barents Observer. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ^ "29 Aug 1996". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Eisenträger, Stian & Per Øyvind Fange (30 March 2008). "- Kraftig vindkast trolig årsaken". Verdens Gang. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b Arlov and Holm (2001): 49

- ^ a b "Arctic science for global challenges". University Centre in Svalbard. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g "9 Næringsvirksomhet". St.meld. nr. 22 (2008–2009): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 17 April 2009. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b "The Looming Military Threat in the Arctic". The Economist. 12 August 2025. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Hansen, Pål (21 June 2025). "Norsk tilstedeværelse på Svalbard svekkes: Lokalstyret ber regjeringen gripe inn". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Population of Svalbard". SSB. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Shops/services". Svalbard Reiseliv. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Attractions". Svalbard Reiseliv. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 179

- ^ Stange, Rolf (15 February 2019). "Lunckefjellet: the end of an arctic coal mine". Spitsbergen | Svalbard. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ Stange, Rolf (26 February 2020). "Svea Nord is history". Spitsbergen | Svalbard. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "Ny-Ålesund". Kings Bay. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 94–203

- ^ "Back in Pyramiden, Svalbard – RUIN MEMORIES". 18 June 2013. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Barr, Susan (14 February 2020), "Pyramiden", Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian), retrieved 24 June 2024

- ^ "Catholic Church in Svalbard and Jan Mayen". www.gcatholic.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Svalbard Treaty". Governor of Svalbard. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "The Svalbard Treaty – Svalbard Museum". svalbardmuseum.no. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Visas and immigration". Governor of Svalbard. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ a b Higgins, Andrew (9 July 2014). "A Harsh Climate Calls for Banishment of the Needy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Entry and residence". Governor of Svalbard. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "5 The administration of Svalbard". Report No. 9 to the Storting (1999–2000): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 29 October 1999. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Lov om Svalbard" (in Norwegian). Lovdata. 19 June 2009. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Organisation". Governor of Svalbard. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "From the cradle, but not to the grave" (PDF). Statistics Norway. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "6 Administrasjon". St.meld. nr. 22 (2008–2009): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 17 April 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Nord-Troms tingrett". Norwegian National Courts Administration. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Lov om gjennomføring i norsk rett av hoveddelen i avtale om Det europeiske økonomiske samarbeidsområde (EØS) m.v. (EØS-loven)". Lovdata (in Norwegian). 10 August 2007. Archived from the original on 10 December 2000. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Entry and residence". Governor of Svalbard. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ "Forskrift om bortvisning og utvisning av personer fra Svalbard – Lovdata".

- ^ "Entry and residence". sysselmannen.no. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ "Immigrants warmly welcomed". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Diplomatic and consular missions of Russia". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Russia and Norway Agree on Boundary" Archived 11 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine article by Andrew E. Kramer in The New York Times 15 September 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2010

- ^ Wither, James (8 September 2021). "Svalbard: NATO's Arctic 'Achilles' Heel'". Per Concordiam. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ Pedersen, Torbjørn (November 2008). "The constrained politics of the Svalbard offshore area". Marine Policy. 32 (6): 913–919. Bibcode:2008MarPo..32..913P. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2008.01.006. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "KYSTVAKTEN – NORWEGIAN COAST GUARD". Research Gate. January 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ "Norway's New Coast Guard Vessel Arrives for Fitting Out at Vard".

- ^ "Norway's Newest Coast Guard Vessel Ready for Operations in the High North". High North News. 23 June 2023.

- ^ Felstead, Peter (15 March 2023). "Norway to Replace its Cancelled NH90s with Six Sikorsky MH-60Rs". European Security and Defence. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ Nilsen, Thomas (15 November 2021). "Russia complains of Norwegian navy's visit to Svalbard". Arctic Today. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ "Evenes". Forsvaret (in Norwegian Nynorsk). Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Nilsen, Thomas (17 May 2022). "How Norway's new P-8 Poseidon will counter Russia's submarine threat in Arctic waters". ArcticToday. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Rosen, Kenneth (17 December 2022). "A Battle for the Arctic Is Underway. And the U.S. Is Already Behind". Politico. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Currency Converter – MSN Money". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Focus on Svalbard". Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police (2008–2009). Report No. 22 to the Storting: Svalbard (PDF) (Report). Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. p. 85; 111. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "Svea-gruva på Svalbard stengt etter 100 år" [The Svea mine on Svalbard closed after 100 years]. itromso.no (in Norwegian). 4 March 2020. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Norway's last Arctic miners are struggling with coal mine's end". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. AP. 13 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Gibbs, Walter; Koranyi, Balazs (18 November 2011). "Norway mobilises for oil push into Arctic". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ "Oversikt over geografiske forhold". Statistics Norway. 2009. Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Vincent, James (4 April 2017). "Keep your data safe from the apocalypse in an Arctic mineshaft". The Verge. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Linder, Courtney (15 November 2019). "Github Code – Storing Code for the Apocalypse". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Machan, Teresa (17 March 2014). "Cruise regulations put Svalbard off-limits". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "8 Research and higher education". Report No. 9 to the Storting (1999–2000): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 29 October 1999. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (21 July 2024). "China's expanding Arctic ambitions challenge the U.S. and NATO". Newsweek. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ Tang, Jane (7 November 2024). "How Chinese nationalism is sending jitters through the Arctic". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ Hopkin, M. (15 February 2007). "Norway Reveals Design of Doomsday' Seed Vault". Nature. 445 (7129): 693. doi:10.1038/445693a. PMID 17301757.

- ^ "Life in the cold store". BBC News. 26 February 2008. Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Gjesteland, Eirik (2004). "Technical solution and implementation of the Svalbard fibre cable" (PDF). Telektronic (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Skår, Rolf (2004). "Why and how Svalbard got the fibre" (PDF). Telektronic (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (1997): 63–67

- ^ "Direkteruter" (in Norwegian). Avinor. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ "Finnair opens twelve new scheduled routes and increases frequencies for summer 2016". Finnair. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ "Finnair denied route to Longyearbyen". thebarentsobserver.com. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016.

- ^ "Finnair grounded: Norway refuses to allow direct flights between Helsinki and Svalbard, citing 1978 agreement – icepeople". icepeople.net. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Charterflygning" (in Norwegian). Lufttransport. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ "11 Sjø og luft – transport, sikkerhet, redning og beredskap". St.meld. nr. 22 (2008–2009): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 17 April 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Temperaturnormaler for Spitsbergen i perioden 1961–1990" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b Torkilsen (1984): 98–99

- ^ a b c Torkilsen (1984): 101

- ^ S.L., Tutiempo Network. "Climate Svalbard Lufthavn (Year 2016) – Climate data (10080)". tutiempo.net. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b Hanssen-Bauer, I.; Førland, E.J.; Hisdal, H.; Mayer, S.; Sandø, A.B.; Sorteberg, A. (2019). "Climate in Svalbard 2100: A knowledge base for climate adaptation" (PDF). Norwegian Environment Agency. ISSN 2387-3027. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "Highest-ever temperature recorded in Norwegian Arctic archipelago". CTV News. 26 July 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Protected Areas in Svalbard" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 33

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 174

- ^ a b Umbreit (2005): 132

- ^ "Firearms in Svalbard". Sysselmannen.no. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "Polar bear kills British boy in Arctic". BBC News. 5 August 2011. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012.

- ^ Grieshaber, Kristen (28 July 2018). "Polar Bear Killed After Attack on Arctic Cruise Ship Guard". NBC4 Washington. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ "German man attacked by polar bear on Norwegian island | DW | 28 July 2018". DW.COM. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ "Nederlander gedood door ijsbeer op Spitsbergen" [Dutchman killed by polar bear on Spitsbergen]. nos.nl (in Dutch). 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polar bear kills Dutch man in Norway's Arctic Svalbard archipelago". Reuters. 28 August 2020. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polar bear killed after injuring woman at Svalbard campsite". The Guardian. Associated Press. 8 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Inge Johansen, Jørn; Eriksen, Inghild (1 July 2021). "På Svalbard er det cirka 300 "fastboende" isbjørner". NPK (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Aars, Jon; Marques, Tiago A.; Lone, Karen; Andersen, Magnus; Wiig, Øystein; Fløystad, Ida Marie Bardalen; Hagen, Snorre B.; Buckland, Stephen T. (2017). "The number and distribution of polar bears in the western Barents Sea". Polar Research. 36. doi:10.1080/17518369.2017.1374125. hdl:10852/65137. ISSN 1751-8369.

- ^ Obbard, Martyn E.; Thiemann, Gregory W.; Peacock, Elizabeth; DeBruyn, Terry D. (2010). Polar bears: proceedings of the 15th Working Meeting of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group, Copenhagen, Denmark, 29 June-3 July 2009 (PDF). Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. p. 150; 159. ISBN 978-2-8317-1255-0.

- ^ Stempniewicz, Lech; Kulaszewicz, Izabela; Aars, Jon (2021). "Yes, they can: polar bears Ursus maritimus successfully hunt Svalbard reindeer Rangifer tarandus platyrhynchus". Polar Biology. 44 (11): 2199–2206. Bibcode:2021PoBio..44.2199S. doi:10.1007/s00300-021-02954-w. ISSN 1432-2056.

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 165

- ^ "eBird – Svalbard". eBird. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ Torkilsen (1984): 162

- ^ "Enormous Jurassic Sea Predator, Pliosaur, Discovered in Norway". Science Daily. 29 February 2008. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Torkilsen (1984): 144

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 29–30

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 32

- ^ About Svalbard: Flora Archived 6 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Sysselmannen.no, retrieved: 10 April 2018

- ^ "Norges nasjonalparker" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Verneområder i Svalbard sortert på kommuner" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Svalbard". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Solar eclipse: Faroe Islands and Svalbard see the sun vanish – video". The Guardian. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Learning in the freezer". The Guardian. 29 August 2007. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Skinner, Toby (1 May 2014). "The Russians on Svalbard". Norwegian Air Shuttle (inflight magazine). Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Umbreit (2005)

- ^ "Heidi The glaciologist". Norwegian Air Shuttle (inflight magazine). 1 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Tony's Non-League Forum: All Other Football Interests: All other football: Is this the world's most Northerly Football Ground?". nonleaguematters.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017.

- ^ "Fotball på Svalbard". Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Svalbard's sporting frontier: from ice to the pitch". All Things Nordic. 7 January 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Arlov, Thor B. (1996). Svalbards historie: 1596–1996 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Aschehoug. ISBN 82-03-22171-8. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Arlov, Thor B.; Holm, Arne O.; Moe, Kirsti (2001). Fra company town til folkestyre: samfunnsbygging i Longyearbyen på 78° nord (in Norwegian). Longyearbyen: Svalbard samfunnsdrift. ISBN 82-996168-0-8. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Carlheim-Gyllensköld, V. (1900). På åttionda breddgraden. En bok om den svensk-ryska gradmätningen på Spetsbergen; den förberedande expeitionen sommaren 1898, dess färd rundt spetsbergens kuster, äfventyr i båtar och på isen; ryssars och skandinavers forna färder; m.m., m.m. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 708–711.

- Cross, Wilbur (2002). Disaster at the Pole: The Crash of the Airship Italia (1st ed.). Lyons Press. ISBN 9781585744961.

- Dege, Wilhelm (2004). Barr, William (ed.). War North of 80: The Last German Arctic Weather Station of World War II. Translated by Barr, William (illustrated ed.). University of Calgary Press. ISBN 9781552381106.

- Fløgstad, Kjartan (2007). Pyramiden: portrett av ein forlaten utopi (in Norwegian). Oslo: Spartacus. ISBN 978-82-430-0398-9.

- Grydehøj, Adam (2020). "Svalbard: International Relations in an Exceptionally International Territory" in The Palgrave Handbook of Arctic Policy and Politics. Palgrave.

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch (1887). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (9th ed.).

- Roskill, Stephen (1954–56). The War at Sea. Vols I-III. HMSO. OCLC 1137414397.

- Stange, Rolf (2011). Spitsbergen: Cold Beauty (in English, German, Dutch, and Norwegian). Rolf Stange. ISBN 978-3-937903-10-1. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Photo book.

- Stange, Rolf (2012). Spitsbergen – Svalbard: A complete guide around the arctic archipelago. Rolf Stange. ISBN 978-3-937903-14-9. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012.

- Tjomsland, Audun & Wilsberg, Kjell (1995). Braathens SAFE 50 år: Mot alle odds. Oslo. ISBN 82-990400-1-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Torkildsen, Torbjørn; Barr, Susan (1984). Svalbard, vårt nordligste Norge (in Norwegian). Oslo: Forlaget Det Beste. ISBN 82-7010-167-2. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Umbreit, Andreas (1997). Guide to Spitsbergen: Svalbard, Franz Josef Land, Jan Mayen (2nd ed.). Bradt Publications. ISBN 9781898323389.

- Umbreit, Andreas (2005). Spitsbergen: Svalbard, Franz Josef, Jan Mayen (3rd ed.). Chalfont St. Peter, Bucks: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-092-3. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

External links

[edit]- Sysselmannen – Governor of Svalbard website

- Svalbard Tourism – official tourist board website

- Weather Forcast Longyearbyen auf der Website Yr.no, Norwegisches Meteorologisches Institut und Norwegischer Rundfunk (NRK).

- Cecilia Blomdahl Impressions of Svalbard and Longyearbyen

Svalbard

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name and historical nomenclature

The name Svalbard derives from Old Norse Svalbarð, combining svalr ("cool" or "chilly") with barð ("edge" or "brim"), denoting "cold coast" or "cold edge." [9] This toponym first appears in the Icelandic Annals of 1194, recording "Svalbarði fundinn" ("Svalbard discovered"), though scholars debate whether it precisely identifies the modern archipelago or possibly eastern Greenland's cold shores, as medieval Norse references often blended vague Arctic locales without precise coordinates.[10] [11] Prior to Norwegian sovereignty, European explorers and whalers commonly referred to the archipelago as Spitsbergen (or Spitzbergen), a Dutch-coined term from the early 17th century evoking its "pointed" or jagged mountains, supplanting earlier vague Norse echoes in favor of descriptive topography observed during voyages.[12] The 1920 Spitsbergen Treaty—formally recognizing Norway's full sovereignty over the islands, including Bear Island—retained Spitsbergen in its international title, but Norway enacted the 1925 Svalbard Act to standardize Svalbard as the official name, reviving the Norse form to assert historical continuity amid competing claims.[13] [14] In Russian nomenclature, the archipelago persists as Шпицберген (Shpitsbergen), a phonetic adaptation of Spitsbergen reflecting Soviet-era mining interests in places like Barentsburg, though the 1920 treaty's equal-access provisions apply regardless of terminological variants.[13] This dual usage underscores how post-treaty geopolitics preserved Spitsbergen in non-Norwegian contexts, even as Svalbard gained primacy in official Norwegian mapping and administration.[14]Geography

Archipelago composition and location

Svalbard is an archipelago situated in the Arctic Ocean, extending between 74° and 81° N latitude and 10° to 35° E longitude.[15] The group lies approximately 930 kilometers north of mainland Norway, about 500 kilometers west of Russia's Franz Josef Land, and roughly 650 kilometers east of Greenland's northeast coast.[16][17] The archipelago encompasses more than 100 islands, islets, and skerries, with a total land area of 61,022 km².[18] Spitsbergen forms the dominant landmass at 39,000 km², comprising the majority of the territory.[19] Other major islands include Nordaustlandet (14,600 km²), Edgeøya (5,000 km²), and Barentsøya (1,300 km²), alongside smaller features such as Prins Karls Forland and Kong Karls Land.[19][20] Glaciers cover approximately 59 percent of Svalbard's land surface, equivalent to about 36,500 km², underscoring the archipelago's predominantly icy character.[19]Geology and landforms

Svalbard's geology features a Precambrian metamorphic basement complex overlain by unmetamorphosed sedimentary rocks spanning the Paleozoic to Cenozoic eras, with unconsolidated Quaternary deposits forming the uppermost layer.[21] The basement includes gneisses and granites, with the highest peak, Newtontoppen at 1,717 meters, composed of coarse-grained granite intruded during the Caledonian orogeny around 400 million years ago.[22] Sedimentary sequences begin with Devonian Old Red Sandstone formations, representing continental deposits from the post-Caledonian erosion phase, followed by Carboniferous coal-bearing strata in basins like Billefjorden.[22] Tectonic activity shaped the archipelago through events including the Svalbardian orogeny in the Late Carboniferous, which created fault zones and basins hosting coal deposits up to 30 meters thick, and the Eocene West Spitsbergen orogeny, resulting in fold-and-thrust belts that uplifted the central spine of Spitsbergen.[23] [24] These processes, combined with ongoing isostatic rebound, contribute to the rugged terrain of folded mountains and deep fjords, such as those in the Hornsund area, where alpine peaks rise sharply from glaciated inlets.[25] Pleistocene glaciations profoundly modified the landscape, eroding U-shaped valleys like Adventdalen, which spans 35 kilometers with widths up to 4 kilometers, through repeated ice stream advances.[26] Continuous permafrost underlies the entire archipelago, with thicknesses ranging from 100 meters in coastal and valley areas to over 500 meters in elevated regions, influencing surface stability and landform preservation.[27] Coal resources, primarily from Carboniferous-Permian and Paleogene formations like the Firkanten Formation, occur as veins and seams within these sedimentary layers, verified through over a century of extraction data.[28]Glaciers and hydrology

Approximately 34,000 km² of Svalbard's land area, or about 55-60% of the archipelago, is covered by glaciers and ice caps, comprising over 2,100 individual features ranging from small valley glaciers to extensive ice fields.[29][30] The largest is Austfonna on Nordaustlandet, spanning roughly 8,000-8,500 km² and ranking among the largest ice caps in the Arctic by area, with a volume estimated in the thousands of cubic kilometers based on radar and satellite-derived bed topography models.[31][29] Tidewater glaciers, which terminate directly in the sea, dominate the western and northern coasts and contribute significantly to mass loss through iceberg calving, with archipelago-wide calving fluxes estimated at 5.0-8.4 km³ water equivalent per year from field and remote sensing observations.[32] Glacier mass balance, measured annually at select sites by the Norwegian Polar Institute through stake networks and snow pit surveys, exhibits high variability driven by winter accumulation and summer ablation processes quantified via glaciological methods.[33] For instance, monitoring at glaciers like Midtre Lovénbreen and Svenbreen has recorded predominantly negative balances since the 1960s, with accelerated losses in recent decades; the mass balance year 2023/24 saw a total ice loss of 61.7 ± 11.1 Gt across monitored Svalbard glaciers, derived from satellite gravimetry and in-situ data calibration.[34][35][36] Calving rates at tidewater fronts, tracked via time-lapse imagery, seismic sensors, and repeat satellite-derived front positions (e.g., over 124,000 positions for 149 glaciers from 1985-2023), fluctuate with terminus dynamics, often exceeding several meters per day at fast-flowing outlets like Kronebreen.[37] Svalbard's hydrology is constrained by continuous permafrost, which underlies nearly the entire land surface and prevents the development of permanent rivers, resulting instead in ephemeral meltwater streams that form during the short summer ablation season.[38] These streams, fed primarily by glacier surface melt and routed through braided channels in proglacial zones, exhibit peak discharges in July-August, with water budgets reconstructed from gauging stations showing high seasonality and limited subsurface infiltration due to frozen ground.[39] Coastal waters, integral to the broader hydrological dynamics, are modulated by the West Spitsbergen Current—a warm, saline branch of the North Atlantic Current (extension of the Gulf Stream)—which transports Atlantic water northward along the western shelf, influencing fjord circulation and glacier-ocean interactions via upwelling and mixing observed in vessel-mounted profiler data.[40][41]Climate

Seasonal patterns and extremes