Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

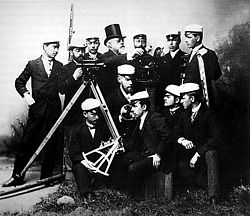

Surveying

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2023) |

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. These points are usually on the surface of the Earth, and they are often used to establish maps and boundaries for ownership, locations, such as the designated positions of structural components for construction or the surface location of subsurface features, or other purposes required by government or civil law, such as property sales.[1]

A professional in land surveying is called a land surveyor. Surveyors work with elements of geodesy, geometry, trigonometry, regression analysis, physics, engineering, metrology, programming languages, and the law. They use equipment, such as total stations, robotic total stations, theodolites, GNSS receivers, retroreflectors, 3D scanners, lidar sensors, radios, inclinometer, handheld tablets, optical and digital levels, subsurface locators, drones, GIS, and surveying software.

Surveying has been an element in the development of the human environment since the beginning of recorded history. It is used in the planning and execution of most forms of construction. It is also used in transportation, communications, mapping, and the definition of legal boundaries for land ownership. It is an important tool for research in many other scientific disciplines.

Definition

[edit]The International Federation of Surveyors defines the function of surveying as follows:[2]

A surveyor is a professional person with the academic qualifications and technical expertise to conduct one, or more, of the following activities;

- to determine, measure and represent land, three-dimensional objects, point-fields and trajectories;

- to assemble and interpret land and geographically related information,

- to use that information for the planning and efficient administration of the land, the sea and any structures thereon; and,

- to conduct research into the above practices and to develop them.

History

[edit]Ancient history

[edit]

Surveying has occurred since humans built the first large structures. In ancient Egypt, a rope stretcher would use simple geometry to re-establish boundaries after the annual floods of the Nile River. The almost perfect squareness and north–south orientation of the Great Pyramid of Giza, built c. 2700 BC, affirm the Egyptians' command of surveying. The groma instrument may have originated in Mesopotamia (early 1st millennium BC).[3] The prehistoric monument at Stonehenge (c. 2500 BC) was set out by prehistoric surveyors using peg and rope geometry.[4]

The mathematician Liu Hui described ways of measuring distant objects in his work Haidao Suanjing or The Sea Island Mathematical Manual, published in 263 AD.

The Romans recognized land surveying as a profession. They established the basic measurements under which the Roman Empire was divided, such as a tax register of conquered lands (300 AD).[5] Roman surveyors were known as Gromatici.

In medieval Europe, beating the bounds maintained the boundaries of a village or parish. This was the practice of gathering a group of residents and walking around the parish or village to establish a communal memory of the boundaries. Young boys were included to ensure the memory lasted as long as possible.

In England, William the Conqueror commissioned the Domesday Book in 1086. It recorded the names of all the land owners, the area of land they owned, the quality of the land, and specific information of the area's content and inhabitants. It did not include maps showing exact locations.

Modern era

[edit]

Abel Foullon described a plane table in 1551, but it is thought that the instrument was in use earlier as his description is of a developed instrument.

Gunter's chain was introduced in 1620 by English mathematician Edmund Gunter. It enabled plots of land to be accurately surveyed and plotted for legal and commercial purposes.

Leonard Digges described a theodolite that measured horizontal angles in his book A geometric practice named Pantometria (1571). Joshua Habermel (Erasmus Habermehl) created a theodolite with a compass and tripod in 1576. Johnathon Sission was the first to incorporate a telescope on a theodolite in 1725.[6]

In the 18th century, modern techniques and instruments for surveying began to be used. Jesse Ramsden introduced the first precision theodolite in 1787. It was an instrument for measuring angles in the horizontal and vertical planes. He created his great theodolite using an accurate dividing engine of his own design. Ramsden's theodolite represented a great step forward in the instrument's accuracy. William Gascoigne invented an instrument that used a telescope with an installed crosshair as a target device, in 1640. James Watt developed an optical meter for the measuring of distance in 1771; it measured the parallactic angle from which the distance to a point could be deduced.

Dutch mathematician Willebrord Snellius (a.k.a. Snel van Royen) introduced the modern systematic use of triangulation. In 1615 he surveyed the distance from Alkmaar to Breda, approximately 72 miles (116 km). He underestimated this distance by 3.5%. The survey was a chain of quadrangles containing 33 triangles in all. Snell showed how planar formulae could be corrected to allow for the curvature of the Earth. He also showed how to resect, or calculate, the position of a point inside a triangle using the angles cast between the vertices at the unknown point. These could be measured more accurately than bearings of the vertices, which depended on a compass. His work established the idea of surveying a primary network of control points, and locating subsidiary points inside the primary network later. Between 1733 and 1740, Jacques Cassini and his son César undertook the first triangulation of France. They included a re-surveying of the meridian arc, leading to the publication in 1745 of the first map of France constructed on rigorous principles. By this time triangulation methods were well established for local map-making.

It was only towards the end of the 18th century that detailed triangulation network surveys mapped whole countries. In 1784, a team from General William Roy's Ordnance Survey of Great Britain began the Principal Triangulation of Britain. The first Ramsden theodolite was built for this survey. The survey was finally completed in 1853. The Great Trigonometric Survey of India began in 1801. The Indian survey had an enormous scientific impact. It was responsible for one of the first accurate measurements of a section of an arc of longitude, and for measurements of the geodesic anomaly. It named and mapped Mount Everest and the other Himalayan peaks. Surveying became a professional occupation in high demand at the turn of the 19th century with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. The profession developed more accurate instruments to aid its work. Industrial infrastructure projects used surveyors to lay out canals, roads and rail.

In the US, the Land Ordinance of 1785 created the Public Land Survey System. It formed the basis for dividing the western territories into sections to allow the sale of land. The PLSS divided states into township grids which were further divided into sections and fractions of sections.[1]

Napoleon Bonaparte founded continental Europe's first cadastre in 1808. This gathered data on the number of parcels of land, their value, land usage, and names. This system soon spread around Europe.

Robert Torrens introduced the Torrens system in South Australia in 1858. Torrens intended to simplify land transactions and provide reliable titles via a centralized register of land. The Torrens system was adopted in several other nations of the English-speaking world. Surveying became increasingly important with the arrival of railroads in the 1800s. Surveying was necessary so that railroads could plan technologically and financially viable routes.

20th century

[edit]

At the beginning of the century, surveyors had improved the older chains and ropes, but they still faced the problem of accurate measurement of long distances. Trevor Lloyd Wadley developed the Tellurometer during the 1950s. It measures long distances using two microwave transmitter/receivers.[7] During the late 1950s Geodimeter introduced electronic distance measurement (EDM) equipment.[8] EDM units use a multi frequency phase shift of light waves to find a distance.[9] These instruments eliminated the need for days or weeks of chain measurement by measuring between points kilometers apart in one go.

Advances in electronics allowed miniaturization of EDM. In the 1970s the first instruments combining angle and distance measurement appeared, becoming known as total stations. Manufacturers added more equipment by degrees, bringing improvements in accuracy and speed of measurement. Major advances include tilt compensators, data recorders and on-board calculation programs.

The first satellite positioning system was the US Navy TRANSIT system. The first successful launch took place in 1960. The system's main purpose was to provide position information to Polaris missile submarines. Surveyors found they could use field receivers to determine the location of a point. Sparse satellite cover and large equipment made observations laborious and inaccurate. The main use was establishing benchmarks in remote locations.

The US Air Force launched the first prototype satellites of the Global Positioning System (GPS) in 1978. GPS used a larger constellation of satellites and improved signal transmission, thus improving accuracy. Early GPS observations required several hours of observations by a static receiver to reach survey accuracy requirements. Later improvements to both satellites and receivers allowed for Real Time Kinematic (RTK) surveying. RTK surveys provide high-accuracy measurements by using a fixed base station and a second roving antenna. The position of the roving antenna can be tracked.

21st century

[edit]The theodolite, total station and RTK GPS survey remain the primary methods in use.

Remote sensing and satellite imagery continue to improve and become cheaper, allowing more commonplace use. Prominent new technologies include three-dimensional (3D) scanning and lidar-based topographical surveys. UAV technology along with photogrammetric image processing is also appearing.

Equipment

[edit]Hardware

[edit]The main surveying instruments in use around the world are the theodolite, measuring tape, total station, 3D scanners, GPS/GNSS, level and rod. Most instruments screw onto a tripod when in use. Tape measures are often used for measurement of smaller distances. 3D scanners and various forms of aerial imagery are also used.

The theodolite is an instrument for the measurement of angles. It uses two separate circles, protractors or alidades to measure angles in the horizontal and the vertical plane. A telescope mounted on trunnions is aligned vertically with the target object. The whole upper section rotates for horizontal alignment. The vertical circle measures the angle that the telescope makes against the vertical, known as the zenith angle. The horizontal circle uses an upper and lower plate. When beginning the survey, the surveyor points the instrument in a known direction (bearing), and clamps the lower plate in place. The instrument can then rotate to measure the bearing to other objects. If no bearing is known or direct angle measurement is wanted, the instrument can be set to zero during the initial sight. It will then read the angle between the initial object, the theodolite itself, and the item that the telescope aligns with.

The gyrotheodolite is a form of theodolite that uses a gyroscope to orient itself in the absence of reference marks. It is used in underground applications.

The total station is a development of the theodolite with an electronic distance measurement device (EDM). A total station can be used for leveling when set to the horizontal plane. Since their introduction, total stations have shifted from optical-mechanical to fully electronic devices.[10]

Modern top-of-the-line total stations no longer need a reflector or prism to return the light pulses used for distance measurements. They are fully robotic, and can even e-mail point data to a remote computer and connect to satellite positioning systems, such as Global Positioning System. Real Time Kinematic GPS systems have significantly increased the speed of surveying, and they are now horizontally accurate to within 1 cm ± 1 ppm in real-time, while vertically it is currently about half of that to within 2 cm ± 2 ppm.[11]

GPS surveying differs from other GPS uses in the equipment and methods used. Static GPS uses two receivers placed in position for a considerable length of time. The long span of time lets the receiver compare measurements as the satellites orbit. The changes as the satellites orbit also provide the measurement network with well conditioned geometry. This produces an accurate baseline that can be over 20 km long. RTK surveying uses one static antenna and one roving antenna. The static antenna tracks changes in the satellite positions and atmospheric conditions. The surveyor uses the roving antenna to measure the points needed for the survey. The two antennas use a radio link that allows the static antenna to send corrections to the roving antenna. The roving antenna then applies those corrections to the GPS signals it is receiving to calculate its own position. RTK surveying covers smaller distances than static methods. This is because divergent conditions further away from the base reduce accuracy.

Surveying instruments have characteristics that make them suitable for certain uses. Theodolites and levels are often used by constructors rather than surveyors in first world countries. The constructor can perform simple survey tasks using a relatively cheap instrument. Total stations are workhorses for many professional surveyors because they are versatile and reliable in all conditions. The productivity improvements from a GPS on large scale surveys make them popular for major infrastructure or data gathering projects. One-person robotic-guided total stations allow surveyors to measure without extra workers to aim the telescope or record data. A fast but expensive way to measure large areas is with a helicopter, using a GPS to record the location of the helicopter and a laser scanner to measure the ground. To increase precision, surveyors place beacons on the ground (about 20 km (12 mi) apart). This method reaches precisions between 5–40 cm (depending on flight height).[12]

Surveyors use ancillary equipment such as tripods and instrument stands; staves and beacons used for sighting purposes; PPE; vegetation clearing equipment; digging implements for finding survey markers buried over time; hammers for placements of markers in various surfaces and structures; and portable radios for communication over long lines of sight.

Software

[edit]Land surveyors, construction professionals, geomatics engineers and civil engineers using total station, GPS, 3D scanners, and other collector data use land surveying software to increase efficiency, accuracy, and productivity. Land Surveying Software is a staple of contemporary land surveying.[13]

Typically, much if not all of the drafting and some of the designing for plans and plats of the surveyed property is done by the surveyor, and nearly everyone working in the area of drafting today (2021) utilizes CAD software and hardware both on PC, and more and more in newer generation data collectors in the field as well.[14] Other computer platforms and tools commonly used today by surveyors are offered online by the U.S. Federal Government and other governments' survey agencies, such as the National Geodetic Survey and the CORS network, to get automated corrections and conversions for collected GPS data, and the data coordinate systems themselves.

Techniques

[edit]

Surveyors determine the position of objects by measuring angles and distances. The factors that can affect the accuracy of their observations are also measured. They then use this data to create vectors, bearings, coordinates, elevations, areas, volumes, plans and maps. Measurements are often split into horizontal and vertical components to simplify calculation. GPS and astronomic measurements also need measurement of a time component.

Distance measurement

[edit]

Before EDM (Electronic Distance Measurement) laser devices, distances were measured using a variety of means. In pre-colonial America Natives would use the "bow shot" as a distance reference ("as far as an arrow can slung out of a bow", or "flights of a Cherokee long bow").[15] Europeans used chains with links of a known length such as a Gunter's chain, or measuring tapes made of steel or invar. To measure horizontal distances, these chains or tapes were pulled taut to reduce sagging and slack. The distance had to be adjusted for heat expansion. Attempts to hold the measuring instrument level would also be made. When measuring up a slope, the surveyor might have to "break" (break chain) the measurement- use an increment less than the total length of the chain. Perambulators, or measuring wheels, were used to measure longer distances but not to a high level of accuracy. Tacheometry is the science of measuring distances by measuring the angle between two ends of an object with a known size. It was sometimes used before to the invention of EDM where rough ground made chain measurement impractical.

Angle measurement

[edit]Historically, horizontal angles were measured by using a compass to provide a magnetic bearing or azimuth. Later, more precise scribed discs improved angular resolution. Mounting telescopes with reticles atop the disc allowed more precise sighting (see theodolite). Levels and calibrated circles allowed the measurement of vertical angles. Verniers allowed measurement to a fraction of a degree, such as with a turn-of-the-century transit.

The plane table provided a graphical method of recording and measuring angles, which reduced the amount of mathematics required. In 1829 Francis Ronalds invented a reflecting instrument for recording angles graphically by modifying the octant.[16]

By observing the bearing from every vertex in a figure, a surveyor can measure around the figure. The final observation will be between the two points first observed, except with a 180° difference. This is called a close. If the first and last bearings are different, this shows the error in the survey, called the angular misclose. The surveyor can use this information to prove that the work meets the expected standards.

Leveling

[edit]

The simplest method for measuring height is with an altimeter using air pressure to find the height. When more precise measurements are needed, means like precise levels (also known as differential leveling) are used. When precise leveling, a series of measurements between two points are taken using an instrument and a measuring rod. Differences in height between the measurements are added and subtracted in a series to get the net difference in elevation between the two endpoints. With the Global Positioning System (GPS), elevation can be measured with satellite receivers. Usually, GPS is somewhat less accurate than traditional precise leveling, but may be similar over long distances.

When using an optical level, the endpoint may be out of the effective range of the instrument. There may be obstructions or large changes of elevation between the endpoints. In these situations, extra setups are needed. Turning is a term used when referring to moving the level to take an elevation shot from a different location. To "turn" the level, one must first take a reading and record the elevation of the point the rod is located on. While the rod is being kept in exactly the same location, the level is moved to a new location where the rod is still visible. A reading is taken from the new location of the level and the height difference is used to find the new elevation of the level gun, which is why this method is referred to as differential levelling. This is repeated until the series of measurements is completed. The level must be horizontal to get a valid measurement. Because of this, if the horizontal crosshair of the instrument is lower than the base of the rod, the surveyor will not be able to sight the rod and get a reading. The rod can usually be raised up to 25 feet (7.6 m) high, allowing the level to be set much higher than the base of the rod.

Determining position

[edit]The primary way of determining one's position on the Earth's surface when no known positions are nearby is by astronomic observations. Observations to the Sun, Moon and stars could all be made using navigational techniques. Once the instrument's position and bearing to a star is determined, the bearing can be transferred to a reference point on Earth. The point can then be used as a base for further observations. Survey-accurate astronomic positions were difficult to observe and calculate and so tended to be a base off which many other measurements were made. Since the advent of the GPS system, astronomic observations are rare as GPS allows adequate positions to be determined over most of the surface of the Earth.

Reference networks

[edit]

Few survey positions are derived from the first principles. Instead, most surveys points are measured relative to previously measured points. This forms a reference or control network where each point can be used by a surveyor to determine their own position when beginning a new survey.

Survey points are usually marked on the earth's surface by objects ranging from small nails driven into the ground to large beacons that can be seen from long distances. The surveyors can set up their instruments in this position and measure to nearby objects. Sometimes a tall, distinctive feature such as a steeple or radio aerial has its position calculated as a reference point that angles can be measured against.

Triangulation is a method of horizontal location favoured in the days before EDM and GPS measurement. It can determine distances, elevations and directions between distant objects. Since the early days of surveying, this was the primary method of determining accurate positions of objects for topographic maps of large areas. A surveyor first needs to know the horizontal distance between two of the objects, known as the baseline. Then the heights, distances and angular position of other objects can be derived, as long as they are visible from one of the original objects. High-accuracy transits or theodolites were used, and angle measurements were repeated for increased accuracy. See also Triangulation in three dimensions.

Offsetting is an alternate method of determining the position of objects, and was often used to measure imprecise features such as riverbanks. The surveyor would mark and measure two known positions on the ground roughly parallel to the feature, and mark out a baseline between them. At regular intervals, a distance was measured at right angles from the first line to the feature. The measurements could then be plotted on a plan or map, and the points at the ends of the offset lines could be joined to show the feature.

Traversing is a common method of surveying smaller areas. The surveyors start from an old reference mark or known position and place a network of reference marks covering the survey area. They then measure bearings and distances between the reference marks, and to the target features. Most traverses form a loop pattern or link between two prior reference marks so the surveyor can check their measurements.

Datum and coordinate systems

[edit]Many surveys do not calculate positions on the surface of the Earth, but instead, measure the relative positions of objects. However, often the surveyed items need to be compared to outside data, such as boundary lines or previous survey's objects. The oldest way of describing a position is via latitude and longitude, and often a height above sea level. As the surveying profession grew it created Cartesian coordinate systems to simplify the mathematics for surveys over small parts of the Earth. The simplest coordinate systems assume that the Earth is flat and measure from an arbitrary point, known as a 'datum' (singular form of data). The coordinate system allows easy calculation of the distances and direction between objects over small areas. Large areas distort due to the Earth's curvature. North is often defined as true north at the datum.

For larger regions, it is necessary to model the shape of the Earth using an ellipsoid or a geoid. Many countries have created coordinate-grids customized to lessen error in their area of the Earth.

Errors and accuracy

[edit]A basic tenet of surveying is that no measurement is perfect, and that there will always be a small amount of error.[17] There are three classes of survey errors:

- Gross errors or blunders: Errors made by the surveyor during the survey. Upsetting the instrument, misaiming a target, or writing down a wrong measurement are all gross errors. A large gross error may reduce the accuracy to an unacceptable level. Therefore, surveyors use redundant measurements and independent checks to detect these errors early in the survey.

- Systematic: Errors that follow a consistent pattern. Examples include effects of temperature on a chain or EDM measurement, or a poorly adjusted spirit-level causing a tilted instrument or target pole. Systematic errors that have known effects can be compensated or corrected.

- Random: Random errors are small unavoidable fluctuations. They are caused by imperfections in measuring equipment, eyesight, and conditions. They can be minimized by redundancy of measurement and avoiding unstable conditions. Random errors tend to cancel each other out, but checks must be made to ensure they are not propagating from one measurement to the next.

Surveyors avoid these errors by calibrating their equipment, using consistent methods, and by good design of their reference network. Repeated measurements can be averaged and any outlier measurements discarded. Independent checks like measuring a point from two or more locations or using two different methods are used, and errors can be detected by comparing the results of two or more measurements, thus utilizing redundancy.

Once the surveyor has calculated the level of the errors in his or her work, it is adjusted. This is the process of distributing the error between all measurements. Each observation is weighted according to how much of the total error it is likely to have caused and part of that error is allocated to it in a proportional way. The most common methods of adjustment are the Bowditch method, also known as the compass rule, and the principle of least squares method.

The surveyor must be able to distinguish between accuracy and precision. In the United States, surveyors and civil engineers use units of feet wherein a survey foot breaks down into 10ths and 100ths. Many deed descriptions containing distances are often expressed using these units (125.25 ft). On the subject of accuracy, surveyors are often held to a standard of one one-hundredth of a foot; about 1/8 inch. Calculation and mapping tolerances are much smaller wherein achieving near-perfect closures are desired. Though tolerances will vary from project to project, in the field and day to day usage beyond a 100th of a foot is often impractical.

Types

[edit]Local organisations or regulatory bodies class specializations of surveying in different ways. Broad groups are:

- As-built survey: a survey that documents the location of recently constructed elements of a construction project. As-built surveys are done for record, completion evaluation and payment purposes. An as-built survey is also known as a 'works as executed survey'. As built surveys are often presented in red or redline and laid over existing plans for comparison with design information.

- Cadastral or boundary surveying: a survey that establishes or re-establishes boundaries of a parcel using a legal description. It involves the setting or restoration of monuments or markers at the corners or along the boundaries of a parcel. These take the form of iron rods, pipes, or concrete monuments in the ground, or nails set in concrete or asphalt. The ALTA/ACSM Land Title Survey is a standard proposed by the American Land Title Association and the American Congress on Surveying and Mapping. It incorporates elements of the boundary survey, mortgage survey, and topographic survey.

- Control surveying: Control surveys establish reference points to use as starting positions for future surveys. Most other forms of surveying will contain elements of control surveying.

- Construction surveying and engineering surveying: topographic, layout, and as-built surveys associated with engineering design. They often need geodetic computations beyond normal civil engineering practice.

- Deformation survey: a survey to determine if a structure or object is changing shape or moving. First the positions of points on an object are found. A period of time is allowed to pass and the positions are then re-measured and calculated. Then a comparison between the two sets of positions is made.

- Dimensional control survey: This is a type of survey conducted in or on a non-level surface. Common in the oil and gas industry to replace old or damaged pipes on a like-for-like basis, the advantage of dimensional control survey is that the instrument used to conduct the survey does not need to be level. This is useful in the off-shore industry, as not all platforms are fixed and are thus subject to movement.

- Foundation survey: a survey done to collect the positional data on a foundation that has been poured and is cured. This is done to ensure that the foundation was constructed in the location, and at the elevation, authorized in the plot plan, site plan, or subdivision plan.

- Hydrographic survey: a survey conducted with the purpose of mapping the shoreline and bed of a body of water. Used for navigation, engineering, or resource management purposes.

- Leveling: either finds the elevation of a given point or establish a point at a given elevation.

- LOMA survey: Survey to change base flood line, removing property from a Special Flood Hazard Area.

- Measured survey : a building survey to produce plans of the building. such a survey may be conducted before renovation works, for commercial purpose, or at end of the construction process.

- Mining surveying: Mining surveying includes directing the digging of mine shafts and galleries and the calculation of volume of rock. It uses specialised techniques due to the restraints to survey geometry such as vertical shafts and narrow passages.

- Mortgage survey: A mortgage survey or physical survey is a simple survey that delineates land boundaries and building locations. It checks for encroachment, building setback restrictions and shows nearby flood zones. In many places a mortgage survey is a precondition for a mortgage loan.

- Photographic control survey: A survey that creates reference marks visible from the air to allow aerial photographs to be rectified.

- Stakeout, layout or setout: an element of many other surveys where the calculated or proposed position of an object is marked on the ground. This can be temporary or permanent. This is an important component of engineering and cadastral surveying.

- Structural survey: a detailed inspection to report upon the physical condition and structural stability of a building or structure. It highlights any work needed to maintain it in good repair.

- Subdivision: A boundary survey that splits a property into two or more smaller properties.

- Topographic survey: a survey of the positions and elevations of points and objects on a land surface, presented as a topographic map with contour lines.

- Existing conditions: Similar to a topographic survey but instead focuses more on the specific location of key features and structures as they exist at that time within the surveyed area rather than primarily focusing on the elevation, often used alongside architectural drawings and blueprints to locate or place building structures.

- Underwater survey: a survey of an underwater site, object, or area.

Plane vs. geodetic surveying

[edit]Based on the considerations and true shape of the Earth, surveying is broadly classified into two types.

Plane surveying assumes the Earth is flat. Curvature and spheroidal shape of the Earth is neglected. In this type of surveying all triangles formed by joining survey lines are considered as plane triangles. It is employed for small survey works where errors due to the Earth's shape are too small to matter.[18]

In geodetic surveying the curvature of the Earth is taken into account while calculating reduced levels, angles, bearings and distances. This type of surveying is usually employed for large survey works. Survey works up to 100 square miles (260 square kilometers ) are treated as plane and beyond that are treated as geodetic.[19] In geodetic surveying necessary corrections are applied to reduced levels, bearings and other observations.[18]

On the basis of the instrument used

[edit]- Chain Surveying

- Compass Surveying

- Plane table Surveying

- Levelling

- Theodolite Surveying

- Traverse Surveying

- Tacheometric Surveying

- Aerial Surveying

Profession

[edit]

The basic principles of surveying have changed little over the ages, but the tools used by surveyors have evolved. Engineering, especially civil engineering, often needs surveyors.

Surveyors help determine the placement of roads, railways, reservoirs, dams, pipelines, retaining walls, bridges, and buildings. They establish the boundaries of legal descriptions and political divisions. They also provide advice and data for geographical information systems (GIS) that record land features and boundaries.

Surveyors must have a thorough knowledge of algebra, basic calculus, geometry, and trigonometry. They must also know the laws that deal with surveys, real property, and contracts.

Most jurisdictions recognize three different levels of qualification:

- Survey assistants or chainmen are usually unskilled workers who help the surveyor. They place target reflectors, find old reference marks, and mark points on the ground. The term 'chainman' derives from past use of measuring chains. An assistant would move the far end of the chain under the surveyor's direction.

- Survey technicians often operate survey instruments, run surveys in the field, do survey calculations, or draft plans. A technician usually has no legal authority and cannot certify his work. Not all technicians are qualified, but qualifications at the certificate or diploma level are available.

- Licensed, registered, or chartered surveyors usually hold a degree or higher qualification. They are often required to pass further exams to join a professional association or to gain certifying status. Surveyors are responsible for planning and management of surveys. They have to ensure that their surveys, or surveys performed under their supervision, meet the legal standards. Many principals of surveying firms hold this status.

Related professions include cartographers, hydrographers, geodesists, photogrammetrists, and topographers, as well as civil engineers and geomatics engineers.

Licensing

[edit]Licensing requirements vary with jurisdiction, and are commonly consistent within national borders. Prospective surveyors usually have to receive a degree in surveying, followed by a detailed examination of their knowledge of surveying law and principles specific to the region they wish to practice in, and undergo a period of on-the-job training or portfolio building before they are awarded a license to practise. Licensed surveyors usually receive a post nominal, which varies depending on where they qualified. The system has replaced older apprenticeship systems.

A licensed land surveyor is generally required to sign and seal all plans. The state dictates the format, showing their name and registration number.

In many jurisdictions, surveyors must mark their registration number on survey monuments when setting boundary corners. Monuments take the form of capped iron rods, concrete monuments, or nails with washers.

Surveying institutions

[edit]

Most countries' governments regulate at least some forms of surveying. Their survey agencies establish regulations and standards. Standards control accuracy, surveying credentials, monumentation of boundaries and maintenance of geodetic networks. Many nations devolve this authority to regional entities or states/provinces. Cadastral surveys tend to be the most regulated because of the permanence of the work. Lot boundaries established by cadastral surveys may stand for hundreds of years without modification.

Most jurisdictions also have a form of professional institution representing local surveyors. These institutes often endorse or license potential surveyors, as well as set and enforce ethical standards. The largest institution is the International Federation of Surveyors (Abbreviated FIG, for French: Fédération Internationale des Géomètres). They represent the survey industry worldwide.

Building surveying

[edit]Most English-speaking countries consider building surveying a distinct profession. They have their own professional associations and licensing requirements. A building surveyor can provide technical building advice on existing buildings, new buildings, design, compliance with regulations such as planning and building control. A building surveyor normally acts on behalf of his or her client ensuring that their vested interests remain protected. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) is a world-recognised governing body for those working within the built environment.[20]

Cadastral surveying

[edit]One of the primary roles of the land surveyor is to determine the boundary of real property on the ground. The surveyor must determine where the adjoining landowners wish to put the boundary. The boundary is established in legal documents and plans prepared by attorneys, engineers, and land surveyors. The surveyor then puts monuments on the corners of the new boundary. They might also find or resurvey the corners of the property monumented by prior surveys.

Cadastral land surveyors are licensed by governments. The cadastral survey branch of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) conducts most cadastral surveys in the United States.[21] They consult with Forest Service, National Park Service, Army Corps of Engineers, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Reclamation, and others. The BLM used to be known as the United States General Land Office (GLO).

In states organized per the Public Land Survey System (PLSS), surveyors must carry out BLM cadastral surveys under that system.

Cadastral surveyors often have to work around changes to the earth that obliterate or damage boundary monuments. When this happens, they must consider evidence that is not recorded on the title deed. This is known as extrinsic evidence.[22]

Quantity surveying

[edit]Quantity surveying is a profession that deals with the costs and contracts of construction projects. A quantity surveyor is an expert in estimating the costs of materials, labor, and time needed for a project, as well as managing the financial and legal aspects of the project. A quantity surveyor can work for either the client or the contractor, and can be involved in different stages of the project, from planning to completion. Quantity surveyors are also known as Chartered Surveyors in the UK.

Notable surveyors

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Some U.S. Presidents were land surveyors. George Washington and Abraham Lincoln surveyed colonial or frontier territories early in their career, prior to serving in office.

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler is considered the "father" of geodetic surveying in the U.S.[23]

David T. Abercrombie practiced land surveying before starting an outfitter store of excursion goods. The business would later turn into Abercrombie & Fitch lifestyle clothing store.

Percy Harrison Fawcett was a British surveyor who explored the jungles of South America attempting to find the Lost City of Z. His biography and expeditions were recounted in the book The Lost City of Z and were later adapted on film screen.

Inō Tadataka produced the first map of Japan using modern surveying techniques starting in 1800, at the age of 55.

See also

[edit]Types and methods

[edit]- Arc measurement, historical method for determining Earth's local radius

- Photogrammetry, a method of collecting information using aerial photography and satellite images

- Cadastral surveyor, used to document land ownership by the production of documents, diagrams, plats, and maps

- Dominion Land Survey, the method used to divide most of Western Canada into one-square-mile sections for agricultural and other purposes

- Public Land Survey System, a method used in the United States to survey and identify land parcels

- Survey township, a square unit of land, six miles (~9.7 km) on a side, done by the U.S. Public Land Survey System

- Construction surveying, the locating of structures relative to a reference line, used in the construction of buildings, roads, mines, and tunnels

- Deviation survey, used in the oil industry to measure a borehole's departure from the vertical

Geospatial survey organizations

[edit]- Survey of India, India's central agency in charge of mapping and surveying

- Ordnance Survey, a national mapping agency for Great Britain

- U.S. National Geodetic Survey, performing geographic surveys as part of the U.S. Department of Commerce

- United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, a former surveying agency of the United States Government

Other

[edit]- Burt's solar compass – Surveying instrument that uses the Sun's direction instead of magnetism

- Cartography – Study and practice of making maps

- Exsecant – Trigonometric function defined as secant minus one

- International Federation of Surveyors – Global organization for the profession of surveying and related disciplines

- Prismatic compass – Navigation and surveying instrument to measure magnetic bearing

- Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors

- Survey camp – Civil engineering training course

- Surveying in early America – Mapping Indian land cessions

- Surveying in North America – Survey methods in North America

References

[edit]- ^ a b United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management Technical Bulletin (1973). Manual of Instructions for the Survey of the Public Lands of the United States 1973. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. p. 1. ISBN 978-0910845601.

- ^ "Definition". fig.net. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Hong-Sen Yan & Marco Ceccarelli (2009), International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms: Proceedings of HMM 2008, Springer, p. 107, ISBN 978-1-4020-9484-2

- ^ Johnson, Anthony, Solving Stonehenge: The New Key to an Ancient Enigma. (Thames & Hudson, 2008) ISBN 978-0-500-05155-9

- ^ Lewis, M. J. T. (23 April 2001). Surveying Instruments of Greece and Rome. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521792974. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Turner, Gerard L'E. Nineteenth Century Scientific Instruments, Sotheby Publications, 1983, ISBN 0-85667-170-3

- ^ Sturman, Brian; Wright, Alan. "The History of the Tellurometer" (PDF). International Federation of Surveyors. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ Cheves, Marc. "Geodimeter-The First Name in EDM". Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ Mahun, Jerry. "Electronic Distance Measurement". Jerrymahun.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ Key, Henk; Lemmens, Mathias. "Robotic Total Stations". GIM International. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "Real-Time Kinematic (RTK): Chapter 5- Resolving Errors". Hexagon. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ "Toni Schenk, Suyoung Seo, Beata Csatho: Accuracy Study of Airborne Laser Scanning Data with Photogrammetry, p. 118" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009.

- ^ "View DigitalGlobe Imagery Solutions @ Geospatial Forum". 4 June 2010.

- ^ "CAD for Surveying". Tutorgram. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places - Registration form for Antietam Village Historic District" (PDF).

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- ^ Kahmen, Heribert; Faig, Wolfgang (1988). Surveying. Berlin: de Gruyter. p. 9. ISBN 3-11-008303-5. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ a b BC Punmia (2005). Surveying by BC Punmia. Firewall Media. p. 2. ISBN 9788170088530. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ N N Basak (2014). Surveying and Levelling. McGraw Hill Education. p. 542. ISBN 9789332901537. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "Building Surveyors London - ZFN Chartered Surveyors". ZFN. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ A History of the Rectangular Survey System by C. Albert White, 1983, Pub: Washington, D.C. : U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management : For sale by Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O.,

- ^ Richards, D., & Hermansen, K. (1995). Use of extrinsic evidence to aid interpretation of deeds. Journal of Surveying Engineering, (121), 178.

- ^ Joe Dracup (1997) "A new age of geodesy begins: 1970-1990", History of Geodetic Survey – Part 7, ACSM Bulletin. American Congress on Surveying and Mapping. [1]

Further reading

[edit]- Brinker, Russell C; Minnick, Roy, eds. (1995). The Surveying Handbook. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-2067-2. ISBN 978-1-4613-5858-9.

- Keay J (2000), The Great Arc: The Dramatic Tale of How India was Mapped and Everest was Named, Harper Collins, 182pp, ISBN 0-00-653123-7.

- Pugh J C (1975), Surveying for Field Scientists, Methuen, 230pp, ISBN 0-416-07530-4

- Genovese I (2005), Definitions of Surveying and Associated Terms, ACSM, 314pp, ISBN 0-9765991-0-4.

External links

[edit]- Géomètres sans Frontières : Association de géometres pour aide au développement. NGO Surveyors without borders (in French)

- The National Museum of Surveying The Home of the National Museum of Surveying in Springfield, Illinois

- Land Surveyors United Support Network Global social support network featuring surveyor forums, instructional videos, industry news and support groups based on geolocation.

- Natural Resources Canada – Surveying Archived 29 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Good overview of surveying with references to construction surveys, cadastral surveys, photogrammetry surveys, mining surveys, hydrographic surveys, route surveys, control surveys and topographic surveys

- Table of Surveying, 1728 Cyclopaedia

- Surveying & Triangulation The History of Surveying And Survey Equipment

- NCEES National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying (NCEES)

- NSPS National Society of Professional Surveyors (NSPS)

- Ground Penetrating Radar FAQ Archived 22 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine Using Ground Penetrating Radar for Land Surveying

- Survey Earth A Global event for professional land surveyors and students to remeasure planet in a single day during summer solstice as a community of land surveyors.

- Surveyors – Occupational Employment Statistics

- Public Land Survey System Foundation (2009), Manual of Surveying Instructions For the Survey of the Public Lands of the United States

Surveying

View on GrokipediaSurveying is the science and art of making all essential measurements to determine the relative position of points or physical and cultural details above, on, or beneath the Earth's surface.[1] It involves assessing land features through observations to support planning, mapping, and construction activities in civil engineering.[2] Fundamental to the discipline are principles such as working from the whole to the part to propagate errors outward and locating each point by at least two independent measurements—linear or angular—for accuracy verification.[3] These methods ensure precise determination of distances, angles, elevations, and positions, forming the basis for reliable geospatial data.[4] Originating over 5,000 years ago in ancient Egypt, where tools like the plumb bob and merkhet were used for aligning structures such as the pyramids and demarcating land after Nile floods, surveying addressed practical needs for boundary definition and monumental construction.[5] By the 18th century, advancements like the theodolite enabled large-scale triangulation networks, exemplified by the French meridian arc measurement from Dunkirk to Barcelona to refine Earth's shape calculations.[6] In contemporary practice, techniques have shifted to electronic tools including total stations for integrated angle and distance measurement, GPS for real-time positioning via satellite signals, and LiDAR for high-density 3D point clouds in terrain modeling.[7] These evolutions have enhanced efficiency and precision, minimizing cumulative errors in projects ranging from infrastructure development to environmental monitoring, while maintaining empirical reliance on verifiable field data over modeled assumptions.[8]

Fundamentals

Definition and Scope

Surveying is the science and profession of determining the relative positions of points on or near the Earth's surface by measuring distances, angles, and elevations, thereby establishing lines, areas, volumes, and contours for mapping, boundary delineation, and engineering purposes. The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) delineates the core functions of surveying as including the measurement, evaluation, and representation of land parcels, three-dimensional objects, point fields, and trajectories; the assembly and interpretation of geographically related data; and the formulation of legal and technical procedures for land and sea administration.[9] A surveyor is a professional with the academic qualifications and technical expertise to perform surveying activities. In Spanish-speaking countries, surveyors are commonly known as agrimensores or topógrafos, and the discipline is referred to as agrimensura. An agrimensor is a professional expert in agrimensura, the discipline concerned with measuring, delimiting, and representing land parcels. They identify, measure, and value real estate properties (public or private, urban or rural), establish legal boundaries, conduct topographic surveys, and prepare plans for cadastral, legal, and territorial planning purposes.[10][11] This encompasses both plane surveying, which treats the Earth's surface as a flat plane suitable for small areas (typically under 250 square kilometers where curvature effects are negligible), and geodetic surveying, which accounts for the Earth's curvature and ellipsoidal shape over larger expanses.[12] The scope of surveying extends beyond mere measurement to practical applications in defining property boundaries, supporting infrastructure development, and enabling precise resource management. In civil engineering and construction, it facilitates site preparation, layout staking, and volume computations for earthwork, with accuracy requirements often specified to millimeters for critical alignments.[13] Legal applications include cadastral surveys for land tenure records, resolving disputes through monumentation and plat certification, while environmental and mining surveys monitor terrain changes and subsurface features.[14] Specialized branches such as hydrographic surveying map underwater topography for navigation and coastal engineering, and topographic surveying produces detailed elevation models for urban planning and flood analysis.[15] Modern surveying integrates with geomatics, incorporating geospatial technologies like GPS and remote sensing to enhance data collection efficiency and precision, though traditional field methods remain foundational for verification.[16] Its interdisciplinary nature supports sectors including transportation (for alignment design), agriculture (for precision farming layouts), and defense (for terrain modeling), underscoring its role in causal chains from data acquisition to informed decision-making in spatial contexts.[17]Core Principles and Mathematical Foundations

Surveying operates on the principle of determining the relative spatial locations of points through direct measurements of angles, distances, and elevations, enabling the creation of maps and models for engineering and legal purposes. These measurements adhere to geometric consistency, where positions are computed relative to control points, assuming a plane tangent to the Earth's surface for local surveys (plane surveying) or incorporating ellipsoidal models for extensive networks (geodetic surveying). Independent checks, such as closed traverses verifying angular and linear closures, ensure reliability, with allowable errors scaled by survey order, for example, angular closure limited to 1 minute times the square root of the number of stations in ordinary surveys.[18][19] The mathematical foundation rests on trigonometry and coordinate geometry. Trigonometric functions—sine, cosine, and tangent—resolve right triangles inherent in survey setups, as per the definitions sin(θ) = opposite/hypotenuse, cos(θ) = adjacent/hypotenuse, and tan(θ) = opposite/adjacent, allowing computation of horizontal distances from slope measurements via HD = slope distance × cos(tan⁻¹(%slope)). Bearings convert to latitudes (north-south components) and departures (east-west) using latitude = horizontal distance × cos(bearing) and departure = horizontal distance × sin(bearing), facilitating rectangular coordinate systems. For curved alignments, central angles and radii yield arc lengths as L = R × θ (θ in radians).[18][20] Error management underpins these computations, distinguishing accuracy (proximity to true value) from precision (measurement repeatability), with random errors propagating inversely with the square root of observations (error ∝ 1/√n) and systematic errors corrected via calibration. Blunders are eliminated through procedural redundancies like double observations, while least squares adjustment minimizes residuals across overdetermined systems, propagating covariance as per the law of error propagation. Vertical distances incorporate slope effects as VD = horizontal distance × %slope/100, and areas derive from coordinate polygons via the shoelace formula: A = (1/2) |Σ (x_i y_{i+1} - x_{i+1} y_i)|. Slope reductions for measured distances apply series approximations, such as horizontal correction C_h ≈ h²/(2d) for height difference h and slant distance d.[18][20][19]Historical Development

Ancient Origins

The practice of surveying emerged in ancient Mesopotamia around 3500 BC, as evidenced by clay tablets recording land measurements for agriculture and property demarcation following seasonal floods of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.[21] These early efforts involved basic tools such as measuring rods, plumb lines for vertical alignment, and sighting poles to establish straight lines and boundaries, reflecting a practical necessity for organized urban planning in cities like Ur.[22] Babylonian surveyors further advanced computational methods, developing tables of reciprocals by approximately 2000 BC to calculate areas of irregular fields, which constituted an empirical precursor to trigonometry independent of Greek theoretical geometry.[23] Boundary disputes were resolved using kudurru stones, inscribed limestone markers erected around 1200 BC to legally fix land limits and prevent encroachment.[24] In ancient Egypt, surveying practices paralleled Mesopotamian needs but were intensified by the annual Nile inundations, which erased field boundaries and necessitated annual remeasurement for taxation and irrigation by around 3000 BC.[24] Professional surveyors, known as harpedonaptai or "rope-stretchers," employed knotted ropes leveraging the 3-4-5 Pythagorean triple to form right angles, alongside plumb bobs for vertical checks and cubit rods for linear distances, enabling precise alignments in monumental architecture.[25] This expertise is demonstrated in the Great Pyramid of Giza, constructed circa 2580–2560 BC under Pharaoh Khufu, where base sides measure 230.33 meters with deviations under 20 cm and orientations aligned to true north within 3 arcminutes, feats achieved without advanced optics but through stellar observations and geometric staking.[26] Additional tools like the merkhet—a timekeeping and sighting device using a plumb line and bar—facilitated nocturnal alignments for pyramid layouts.[27] Greek surveying built on Egyptian foundations by the 6th century BC, incorporating theoretical geometry from Thales and Pythagoras to refine leveling and distance methods, though practical tools remained rudimentary until Hellenistic innovations.[24] Hero of Alexandria (c. 10–70 AD) described the dioptra, a precursor to the theodolite, for measuring angles and elevations in engineering projects like canals.[28] Roman techniques, systematized from the 1st century BC, emphasized the groma—a cross-staff with plumb lines for establishing perpendiculars and grids—for military camps, roads, and aqueducts, as detailed in Vitruvius's De Architectura (c. 15 BC), which prescribed trigonometric calculations for terrain profiling.[29][30] These methods ensured centuriation grids dividing conquered lands into square plots of 710 meters per side, facilitating efficient administration across the empire.[31]Early Modern Advances (16th-19th Centuries)

The early modern period marked a transition in surveying from rudimentary tools to precise instrumentation and systematic methods, driven by needs for accurate mapping, navigation, and territorial administration in expanding European states. The introduction of the theodolite around 1550 by English mathematician Leonard Digges provided a means to measure horizontal and vertical angles with greater accuracy than prior quadrant-based devices, facilitating detailed topographic work.[32] In 1620, Edmund Gunter invented the Gunter's chain, a 66-foot standardized tool for linear measurement that reduced errors in chaining distances over uneven terrain and became a staple in English surveying practice until the late 19th century.[33] Methodological advances centered on triangulation, first conceptualized by Gemma Frisius in 1533 as a way to compute distances via angular measurements from known baselines, avoiding direct chaining across obstacles. Willebrord Snellius applied this in 1615 to survey a 72-mile meridian arc in the Netherlands, establishing it as a viable technique for large-scale mapping.[34] By 1669, Jean Picard enhanced the method using telescopic instruments to measure a meridian arc near Paris with unprecedented precision, contributing to refinements in Earth's oblateness calculations.[35] Large national surveys exemplified these innovations. In Great Britain, the Principal Triangulation began in 1784 under William Roy, employing Ramsden's newly constructed great theodolite—capable of arcseconds accuracy—for baseline measurements and angle networks that formed the basis of the Ordnance Survey's mapping.[36] France's Cassini family conducted a comprehensive triangulation-based map of the kingdom from the 1740s to 1793, integrating geodesic data to produce the first national topographic chart at 1:86,400 scale.[37] The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, initiated in 1802 by William Lambton, extended over 2,400 miles of arcs using similar principles, achieving accuracies vital for colonial administration and scientific inquiry into the Himalayas' heights.[38] These efforts underscored surveying's role in geodetic science, with instruments like the improved theodolite enabling verifiable data that informed astronomy and cartography, though challenges such as atmospheric refraction and baseline precision persisted, requiring empirical corrections.[33]20th Century Innovations

The 20th century introduced electronic technologies that fundamentally transformed surveying from labor-intensive optical methods to precise, rapid electronic measurements. Electronic distance measurement (EDM) devices, utilizing modulated light or microwaves, enabled accurate distance determination over kilometers without physical tapes or chains. The first EDM instrument, the Geodimeter, was developed in Sweden in 1948, employing infrared light modulated at radio frequencies to measure phase differences for distance calculation.[39] In the 1950s, microwave-based systems like the Tellurometer, invented by Trevor Lloyd Wadley in South Africa, extended measurement ranges to tens of kilometers, facilitating geodetic surveys previously impractical.[40] These innovations reduced fieldwork time and error sources, with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey adopting EDM by the mid-1950s for national control networks.[41] Building on EDM, the total station emerged in the late 1960s as an integrated instrument combining an electronic theodolite for angle measurement with EDM for distances, along with onboard data recording. The Zeiss Elta 46, introduced in 1968, represented one of the earliest commercial total stations, allowing simultaneous capture of horizontal and vertical angles and slant distances.[42] By the 1970s, portable total stations revolutionized routine surveys, automating computations and minimizing manual transcription errors; for instance, models from Sokkisha, a major manufacturer since 1920, incorporated these features for construction and topographic applications.[43] This integration increased efficiency, with accuracies reaching millimeters over hundreds of meters, supplanting separate transits and EDM units.[44] Advancements in photogrammetry complemented ground-based innovations, leveraging aerial photography for large-scale mapping. Early 20th-century developments included stereoplotters for deriving contours from overlapping images, with the U.S. Geological Survey refining techniques using panoramic and multi-lens cameras since 1904.[45] Analytical photogrammetry, formalized mid-century, used mathematical models to correct distortions, enabling precise 3D coordinates from stereo pairs without mechanical plotters.[46] These methods supported military and civilian mapping, though they required calibration against ground control points established via EDM and total stations.[47] Modern theodolites evolved concurrently, with manufacturers like Heinrich Wild producing high-precision optical models such as the T2 and T3 in the early 1900s, which gained widespread adoption for their durability and micrometer readings.[48] By mid-century, optical micrometers and autocollimators enhanced angular resolution to seconds of arc, paving the way for digital encoders in total stations. These refinements minimized refractive errors and supported denser control networks essential for urban expansion and infrastructure projects.[40]21st Century Transformations

The widespread adoption of real-time kinematic (RTK) global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) in the early 2000s enabled surveyors to achieve centimeter-level accuracy in real-time positioning, fundamentally shifting from post-processed to instantaneous data collection for applications like construction staking and boundary delineation.[49] By processing carrier-phase signals from base and rover receivers, RTK mitigated atmospheric and satellite clock errors, reducing fieldwork duration by up to 50% compared to static GPS methods in prior decades.[50] This technology, building on prototypes from the 1990s, became a standard tool by the mid-2000s, with integration into robotic total stations allowing automated tracking and measurement over dynamic sites.[51] Light detection and ranging (LiDAR) systems, particularly terrestrial and airborne variants, transformed topographic and as-built surveying in the 2000s by generating dense point clouds with millions of measurements per second, capturing surface details inaccessible to traditional instruments.[52] First applied aerially in the 1980s, LiDAR's 21st-century proliferation stemmed from miniaturized sensors and improved algorithms, yielding vertical accuracies of 10-15 cm over large areas for flood modeling and infrastructure assessment.[53] Concurrently, 3D laser scanners emerged as portable tools for high-definition surveying, producing survey-grade point clouds for volumetric calculations and deformation monitoring, with scan rates exceeding 1 million points per second by the 2010s.[54] These methods enhanced causal understanding of terrain dynamics through empirical 3D reconstructions, though data volume necessitated advanced processing to filter noise from vegetation or structures.[55] Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, revolutionized aerial surveying from the mid-2010s onward, enabling rapid photogrammetric mapping of expansive sites with ground sampling distances under 2 cm per pixel, slashing acquisition times from weeks to hours for agriculture and mining projects.[56] Regulatory advancements, such as FAA Part 107 certification in 2016, accelerated civilian adoption, integrating UAVs with onboard GNSS and LiDAR payloads for orthomosaic generation and volume computations accurate to 1-3% error.[57] This shift reduced human exposure to hazardous terrains while providing verifiable datasets via structure-from-motion algorithms, though challenges like signal interference in urban canyons persist.[58] Emerging integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning in the 2020s has automated point cloud classification and anomaly detection, processing terabytes of survey data to identify features like pavement distress with 95% accuracy, thereby minimizing manual interpretation errors.[59] Cloud-based platforms facilitate real-time collaboration and BIM-compatible outputs, with AI-driven predictive modeling enhancing error mitigation in GNSS networks.[60] These developments, grounded in empirical validation against ground truth, underscore surveying's evolution toward data-centric workflows, though reliance on proprietary algorithms warrants scrutiny for reproducibility.[61]Instruments and Equipment

Measuring Devices

Measuring devices in surveying encompass instruments designed to quantify distances, angles, and elevations with precision required for mapping and construction. Early distance measurements relied on Gunter's chain, developed in 1620 by Edmund Gunter, which measured 66 feet via 100 iron links, each 7.92 inches long, facilitating standardized linear assessments in land surveys.[62] Steel tapes, introduced in the 19th century, replaced chains due to their flexibility and reduced sag errors; these tapes, often 100 feet long, achieve accuracies of ±0.01 feet under controlled tension and temperature.[63] Invar tapes, alloyed with nickel to minimize thermal expansion (coefficient approximately 1.2 × 10^{-6}/°C), enable sub-millimeter precision over baselines up to 100 meters, essential for geodetic control networks.[64] Optical levels, including dumpy levels patented by William Gravatt in 1832, establish horizontal sight lines for elevation differences using a spirit level and telescope; modern variants like the Leica NA2 achieve accuracies of 1:40,000, or about ±0.25 mm per km double-run.[33][65] The dumpy level's rigid design prevents relative motion between the bubble and line of sight, supporting elevation transfers with errors under 2 mm over 100 meters when paired with invar rods.[66] Theodolites measure horizontal and vertical angles; originating from Leonard Digges' 1571 description in Pantometria, they evolved into transit theodolites by the 19th century, capable of 20 arcsecond resolutions.[67] Precision theodolites, such as those by Ramsden in 1787, employ optical micrometers for readings to 0.1 arcseconds, critical for triangulation where angular errors propagate to positional inaccuracies via sine rule computations.[36] Total stations integrate electronic theodolites with distance meters using phase-shift or pulse laser technology, introduced commercially in 1971; they compute 3D coordinates directly, with accuracies of 1 mm + 1 ppm for distance and 1 arcsecond for angles.[68] This combination reduces fieldwork by automating stadia reductions and reflectorless measurements up to 500 meters, though atmospheric refraction and prism centering introduce systematic errors mitigated by empirical corrections.[69]Positioning Systems

Positioning systems in surveying determine the geospatial coordinates of points relative to established reference frames, crucial for control surveys and integration with other measurements. These systems have evolved from ground-based triangulation to satellite-based Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), providing absolute positioning with varying accuracy levels depending on the technique and corrections applied. GNSS receivers calculate positions by processing signals from orbiting satellites, using trilateration to solve for latitude, longitude, and elevation.[70] The U.S. Global Positioning System (GPS), fully operational since December 1993 with 24 satellites, pioneered satellite positioning for surveying in the 1980s through differential techniques. Complementary constellations—Russia's GLONASS (full operational capability in 2011), Europe's Galileo (initial services from 2016), and China's BeiDou (global coverage by 2020)—enhance satellite availability, reducing dilution of precision and improving reliability in obstructed environments. Multi-constellation GNSS receivers achieve positioning fixes faster and with greater robustness than single-system GPS alone.[71][70] For sub-centimeter precision required in cadastral and engineering surveys, augmentation methods correct common errors from ionospheric delay, satellite clock drift, and multipath. Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) positioning employs a fixed base station transmitting carrier-phase corrections to a rover via radio or cellular networks, yielding horizontal accuracies of 8 mm + 1 ppm (parts per million) of baseline distance and vertical accuracies of 15 mm + 1 ppm. Network RTK, using Continuously Operating Reference Stations (CORS), extends coverage over wide areas with similar precision by interpolating virtual reference data.[72][73] Post-processed techniques, such as static GNSS surveys, involve extended occupations (typically 30 minutes to several hours per point) followed by differential analysis, attaining millimeter-level accuracy suitable for geodetic control networks. Precise Point Positioning (PPP) leverages global correction models without local bases, offering decimeter to centimeter accuracy after convergence periods of 20-60 minutes, increasingly viable with dual-frequency receivers. Hybrid systems integrate GNSS with inertial measurement units (IMUs) for continuous positioning in GNSS-denied settings like urban canyons. Surveyors select methods based on project tolerances, with RTK dominating real-time applications due to efficiency despite dependency on line-of-sight to sky.[74][75]Data Processing Software

Data processing software in surveying encompasses specialized applications designed to ingest raw observational data from instruments such as total stations, GNSS receivers, and levels, then apply computational algorithms to correct errors, compute coordinates, and generate deliverables like digital maps or legal descriptions. These tools automate traditionally manual calculations, enabling efficient handling of large datasets while ensuring compliance with standards for accuracy, such as those outlined in the Federal Geodetic Control Committee guidelines. Fundamental operations include data import in proprietary or standard formats (e.g., ASCII, LandXML), outlier detection via statistical tests, and network adjustment to distribute errors across observations.[76] A cornerstone algorithm in these systems is least-squares adjustment, which solves overdetermined systems by minimizing the sum of squared residuals weighted by observation precisions, thereby providing optimal estimates of unknown parameters like station coordinates under Gaussian error assumptions. This method is particularly vital for geodetic networks and GNSS post-processing, where it integrates carrier-phase ambiguities and tropospheric delays resolved through double-differencing techniques. For instance, in GNSS data reduction, least-squares formulations incorporate satellite ephemerides and receiver clock biases to yield centimeter-level positions, outperforming simpler averaging in multipath-prone environments.[77] Complementary approaches, such as Kalman filtering, enable real-time or sequential processing for dynamic surveys, fusing inertial data with GNSS for robust trajectory estimation in mobile mapping. Commercial software suites dominate professional use, with examples including Trimble Business Center, which supports multi-instrument data fusion and exports to CAD formats, processing workflows that reduced adjustment times from hours to minutes for control networks as of its 2023 release. Leica Infinity provides similar capabilities, emphasizing cloud-based collaboration for GNSS baseline computations accurate to millimeters over baselines exceeding 100 km. Open-source alternatives like RTKLIB offer least-squares GNSS processing for cost-sensitive applications, though they require user expertise to validate results against proprietary benchmarks. Integration with GIS platforms, such as ArcGIS or QGIS plugins, facilitates terrain modeling and volume computations from adjusted point clouds, with error propagation tracked via covariance matrices. Quality control features in these programs include chi-squared tests for residual analysis and Monte Carlo simulations for uncertainty quantification, ensuring outputs meet jurisdictional tolerances (e.g., 1:5000 horizontal accuracy for cadastral surveys). Recent advancements incorporate machine learning for automated blunder detection, as demonstrated in hybrid least-squares models that improved GNSS convergence by 20-30% in urban canyons per 2024 studies.[78] Users must verify software against independent benchmarks, given vendor-specific implementations that may diverge in handling datum transformations like ITRF to local grids.[79]Surveying Methods

Distance and Angle Measurement

Distance and angle measurements form the core of most surveying techniques, enabling the determination of relative positions through methods such as triangulation, which relies primarily on angles, and trilateration, which uses distances.[80] These measurements allow surveyors to establish control points and map features with precision, accounting for factors like terrain slope by converting slope distances to horizontal equivalents via trigonometric corrections.[63] Traditional distance measurement employed direct methods using chains or tapes, such as the Gunter's chain of 66 feet (20.117 meters) divided into 100 links, pulled under tension to minimize sag and ensure accuracy within 1:5000 for closures in early surveys.[81] [82] Angular measurements historically used compasses or circumferentors to determine bearings, though these were prone to magnetic interference and limited to horizontal angles with accuracies of about 1 degree.[6] [83] Modern electronic distance measurement (EDM) instruments, introduced in the mid-20th century, emit modulated electromagnetic waves—typically infrared or laser—to a reflector, calculating distance from the phase shift or time-of-flight, achieving accuracies of 1 part per million or better over ranges up to 100 kilometers.[84] [85] For angles, theodolites measure horizontal and vertical orientations using optical encoders, with precisions down to 1 arcsecond, often verified by repeating face-left and face-right observations to average out collimation errors.[86] Total stations integrate EDM with electronic theodolites, automating slope distance, zenith angle, and horizontal angle recordings to compute coordinates via polar-to-Cartesian conversions, reducing fieldwork time while maintaining sub-millimeter relative accuracy in robotic models.[87] [69] Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), such as GPS, provide distance-derived positions through carrier-phase measurements, offering absolute accuracies of 1-5 centimeters in real-time kinematic (RTK) mode after differential corrections, though line-of-sight obstructions limit their use in dense environments compared to optical methods.[88] In traversing, sequential distance and angle measurements form closed loops for error adjustment, with least-squares optimization ensuring network reliability.[80]Leveling and Elevation Determination