Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Semi-trailer truck

View on Wikipedia

A semi-trailer truck[1] (also known by a wide variety of other terms – see below) is the combination of a tractor unit and one or more semi-trailers to carry freight. A semi-trailer attaches to the tractor with a type of hitch called a fifth wheel.

Other terms

[edit]There are a wide variety of English-language terms for a semi-trailer truck, including:

- Semi-trailer

- Semi-truck

- Truck & trailer[2]

- Semi[3]

- Big rig[4]

- Tractor-trailer[5]

- Eighteen-wheeler[6]

- Articulated lorry[7]

- Artic[8] (short for articulated lorry)

- Juggernaut[9]

- Heavy Goods Vehicle/HGV[10]

- Transport truck

- Transfer truck

Regional configurations

[edit]Europe

[edit]

The main difference between tractor units in Europe and North America is that European models are cab over engine (COE, called "forward control" in the United Kingdom),[11] while the majority of North American trucks are "conventional" (called "normal control" or "bonneted" in the UK).[12][13] European trucks, whether straight trucks or fully articulated, have a sheer face on the front. This allows shorter trucks with longer trailers (with larger freight capacity) within the legal maximum total length. Furthermore, it offers greater maneuverability in confined areas, a more balanced weight-distribution, and better overall view for the driver. The major disadvantage is that for repairs on COE trucks, the entire cab has to hinge forward to allow maintenance access.[citation needed]

In Europe, usually only the driven tractor axle has dual wheels, while single wheels are used for every other axle on the tractor and the trailer. The most common combination used in Europe is a semi tractor with two axles and a cargo trailer with three axles, one of which is sometimes a lift axle, giving 5 axles and 12 wheels in total. This format is now common across Europe as it is able to meet the EU maximum weight limit of 40,000 kg (88,000 pounds) without overloading any axle. Individual countries have raised their own weight limit. The U.K., for example, has a 44,000 kg (97,000 pounds) limit, an increase achieved by adding an extra axle to the tractor, usually in the form of a middle unpowered lifting axle (midlift) with a total of 14 wheels. The lift axles used on both tractors and trailers allow the trucks to remain legal when fully loaded (as weight per axle remains within the legal limits); on the other hand, these axle set(s) can be raised off the roadway for increased maneuverability or for reduced fuel consumption and tire wear when carrying lighter loads. Although lift axles usually operate automatically, they can be lowered manually even while carrying light loads, in order to remain within legal (safe) limits when, for example, navigating back-road bridges with severely restricted axle loads. For greater detail, see the United Kingdom section, below.[citation needed]

When using a dolly, which generally has to be equipped with lights and a license plate, rigid trucks can be used to pull semi-trailers. The dolly is equipped with a fifth wheel to which the trailer is coupled. Because the dolly attaches to a pintle hitch on the truck, maneuvering a trailer hooked to a dolly is different from maneuvering a fifth wheel trailer. Backing the vehicle requires the same technique as backing an ordinary truck/full trailer combination, though the dolly/semi setup is probably longer, thus requiring more space for maneuvering. The tractor/semi-trailer configuration is rarely used on timber trucks since they use the two major advantages of having the weight of the load on the drive wheels, and the loader crane used to lift the logs from the ground can be mounted on the rear of the truck behind the load, allowing a short (lightweight) crane to reach both ends of the vehicle without uncoupling. Also, construction trucks are more often seen in a rigid + midaxle trailer configuration instead of the tractor/semi-trailer setup.[citation needed]

Continental Europe

[edit]

The maximum overall length in the EU and EEA member states was 18.75 m (61.5 ft) with a maximum weight of 40 or 44 tonnes (39.4 or 43.3 long tons; 44.1 or 48.5 short tons) if carrying an ISO container.[14] However, rules limiting the semi-trailers to 16.5 m (54 ft) and 18.75 m are met with trucks carrying a standardized 7.82 m (26 ft) body with one additional 7.82 m body on tow as a trailer.[15] 25.25-metre (83 ft) truck combinations were developed under the branding of EcoCombi which influenced the name of EuroCombi for an ongoing standardization effort where such truck combinations shall be legal to operate in all jurisdictions of the European Economic Area. With the 50% increase in cargo weight, the fuel efficiency increases an average of 20% with a corresponding relative decrease in carbon emissions and with the added benefit of one third fewer trucks on the road.[14] The 1996 EU regulation defines a Europe Module System (EMS) as it was implemented in Sweden. The wording of EMS combinations and EuroCombi are now used interchangeably to point to truck combinations as specified in the EU document; however, apart from Sweden and Finland, the EuroCombi is only allowed to operate on specific roads in other EU member states. Since 1996 Sweden and Finland formally won a final exemption from the European Economic Area rules with 60 tonne and 25.25-metre (83 ft) combinations. From 2006, 25.25 m truck trailer combinations are to be allowed on restricted routes within Germany, following a similar (on-going) trial in The Netherlands. Similarly, Denmark has allowed 25.25 m combinations on select routes. These vehicles will run a 60-tonne (59.1-long-ton; 66.1-short-ton) weight limit. Two types are to be used: 1) a 26-tonne truck pulling a dolly and semi-trailer, or 2) an articulated tractor unit pulling a B-double, member states gained the ability to adopt the same rules. In Italy the maximum permitted weight (unless exceptional transport is authorized) is 44 tonnes for any kind of combination with five axles or more. Czech Republic has allowed 25.25 m combinations with a permission for a selected route.[citation needed]

Nordic countries

[edit]

Denmark and Norway allow 25.25 m (83 ft) trucks (Denmark from 2008, and Norway from 2008 on selected routes). In Sweden, the allowed length has been 24 m (79 ft) since 1967. Before that, the maximum length was unlimited; the only limitations were on axle load. What stopped Sweden from adopting the same rules as the rest of Europe, when securing road safety, was the national importance of a competitive forestry industry.[14][16] Finland, with the same road safety issues and equally important forestry industry, followed suit. The change made trucks able to carry three stacks of cut-to-length logs instead of two, as it would be in a short combination. They have one stack together with a crane on the 6×4 truck, and two additional stacks on a four axle trailer. The allowed gross weight in both countries is up to 60 t (59 long tons; 66 short tons) depending on the distance between the first and last axle.[citation needed]

In the negotiations starting in the late 1980s preceding Sweden and Finland's entries to the European Economic Area and later the European Union, they insisted on exemptions from the EU rules citing environmental concerns and the transportation needs of the logging industry. In 1995, after their entry to the union, the rules changed again, this time to allow trucks carrying a standard CEN unit of 7.82 m (26 ft) to draw a 13.6 m (45 ft) standard semi-trailer on a dolly, a total overall length of 25.25 m. Later, B-double combinations came into use, often with one 6 m (20 ft) container on the B-link and a 12 m (40 ft) container (or two 6 m containers) on a semi-trailer bed. In allowing the longer truck combinations, what would take two 16.5 m (54 ft) semi-trailer trucks and one 18.75 m (62 ft) truck and trailer to haul on the continent now could be handled by just two 25.25 m trucks – greatly reducing overall costs and emissions. Prepared since late 2012 and effective in January 2013, Finland has changed its regulations to allow total maximum legal weight of a combination to be 76 t (75 long tons; 84 short tons). At the same time the maximum allowed height would be increased by 20 cm (8 in); from current maximum of 4.2 m (13.8 ft) to 4.4 m (14.4 ft). The effect this major maximum weight increase would cause to the roads and bridges in Finland over time is strongly debated.[citation needed]

However, longer and heavier combinations are regularly seen on public roads; special permits are issued for special cargo. The mining company Boliden AB have a standing special permit for 76-tonne (75-long-ton; 84-short-ton) combinations on select routes between mines in the inland and the processing plant in Boliden, taking a 50-tonne (49-long-ton; 55-short-ton) load of ore. Volvo has a special permit for a 32 m (105 ft), steering B-trailer-trailer combination carrying two 12 m (40 ft) containers to and from Gothenburg harbour and the Volvo Trucks factory, all on the island of Hisingen.[18] Another example is the ongoing project En Trave Till (lit. 'One more pile' or 'One more stack') started in December 2008. It will allow even longer vehicles to further rationalize the logging transports. As the name of the project points out, it will be able to carry four stacks of timber, instead of the usual three. The test is limited to Norrbotten county and the European route E4 between the timber terminal in Överkalix and the sawmill in Munksund (outside Piteå). The vehicle is a 30 m (98 ft) long truck trailer combination with a gross weight exceeding 90 tonnes (89 long tons; 99 short tons). It is estimated that this will give a 20% lower cost and 20–25% CO2 emissions reduction compared to the regular 60-tonne (59-long-ton; 66-short-ton) truck combinations. As the combination spreads its weight over more axles, braking distance, road wear and traffic safety is believed to be either the same or improved with the 90-tonne (89-long-ton; 99-short-ton) truck-trailer. In the same program two types of 76-tonne (75-long-ton; 84-short-ton) combinations will be tested in Dalsland and Bohuslän counties in western Sweden: an enhanced truck and trailer combination for use in the forest and a b-double for plain highway transportation to the mill in Skoghall. In 2012, the Northland Mining company received permission for 90-tonne (89-long-ton; 99-short-ton) combinations with normal axle load (an extra dolly) for use on the 150 km (93 mi) Kaunisvaara-Svappavaara route, carrying iron ore.[19][20][21]

As of 2015[update], the longest and heaviest truck in everyday use in Finland is operated by transport company Ketosen Kuljetus as part of a pilot project studying transport efficiency in the timber industry. The combined vehicle is 33 metres (108 ft) long, has 13 axles, and weighs a total of 104 tonnes (102 long tons; 115 short tons).[22][23]

Starting from 21 January 2019 the Government of Finland changed the maximum allowed length of truck from 25.25 to 34.50 meters (82.8 to 113.2 ft). New types of vehicle combinations that differ from the current standards may also be used on the road. The requirements for combinations also include camera systems for side visibility, an advanced emergency braking and lane detector system, electronic driving stability system and electronically controlled brakes. Maximum length of a vehicle combination 34.5 metres Maximum length of a vehicle combination 34.5 metres

United Kingdom

[edit]

In the United Kingdom, a semi-trailer truck is known as an 'articulated lorry' (or colloquially as an 'artic'). The maximum permitted gross weight of a semi-trailer truck without the use of a Special Type General Order (STGO) is 44,000 kg (97,000 lb). In order for a 44,000 kg semi-trailer truck to be permitted on UK roads the tractor and semi-trailer must have three or more axles each. Lower weight semi-trailer trucks can mean some tractors and trailer having fewer axles.[24] In practice, as with double decker buses and coaches in the UK, there is no legal height limit for semi-trailer trucks; however, bridges over 16.5 ft (5.03 m) do not have the height marked on them. Semi-trailer trucks in continental Europe have a height limit of 13.1 ft (4.0 m). Vehicles heavier than 44,000 kg are permitted on UK roads but are indivisible loads, which would be classed as abnormal (or oversize). Such vehicles are required to display an STGO (Special Types General Order) plate on the front of the tractor unit and, under certain circumstances, are required to travel by an authorized route and have an escort.[citation needed]

Most UK trailers are 45 ft (13.7 m) long and, dependent on the position of the fifth wheel and kingpin, a coupled tractor unit and trailer will have a combined length of between 50 and 55 ft (15.25 and 16.75 m). Although the Construction and Use Regulations allow a maximum rigid length of 60 ft (18.2 m), this, combined with a shallow kingpin and fifth wheel set close to the rear of the tractor unit, can give an overall length of around 75 ft (22.75 m).[25]

In January 2012, the Department for Transport began conducting a trial of longer semi-trailers. The trial involves 900 semi-trailers of 48 ft (14.6 m) in length (i.e. 3 ft [1 m] longer than the current maximum), and a further 900 semi-trailers of 51 ft (15.65 m) in length (i.e. 7 ft [2.05 m] longer). This will result in the total maximum length of the semi-trailer truck being 57 ft (17.5 m) for trailers 48 ft in length, and 61 ft (18.55 m) for trailers 51 ft long. The increase in length will not result in the 97,000 lb weight limit being exceeded and will allow some operators to approach the weight limit which may not have been previously possible due to the previous length of trailers. The trial will run for a maximum of 10 years. Providing certain requirements are fulfilled, a Special Types General Order (STGO) allows for vehicles of any size or weight to travel on UK roads. However, in practice, any such vehicle has to travel by a route authorized by the Department of Transport and move under escort. The escort of abnormal loads in the UK is now predominantly carried out by private companies, but extremely large or heavy loads that require road closures must still be escorted by the police.[citation needed]

In the UK, some semi-trailer trucks have eight tyres on three axles on the tractor; these are known as six-wheelers or "six leggers," with either the centre or rear axle having single wheels which normally steer as well as the front axle and can be raised when not needed (i.e. when unloaded or only a light load is being carried; an arrangement known as a TAG axle when it is the rear axle, or mid-lift when it is the center axle). Some trailers have two axles which have twin tyres on each axle; other trailers have three axles, of which one axle can be a lift axle which has super-single wheels. In the UK, two wheels bolted to the same hub are classed as a single wheel, therefore a standard six-axle articulated truck is considered to have twelve wheels, even though it has twenty tyres. The UK also allows semi-trailer truck which have six tyres on two axles; these are known as four-wheelers.[citation needed]

In 2009, the operator Denby Transport designed and built a 83 ft-long (25.25 m) B-Train (or B-Double) semi-trailer truck called the Denby Eco-Link to show the benefits of such a vehicle, which were a reduction in road accidents and result in fewer road deaths, a reduction in emissions due to the one tractor unit still being used and no further highway investment being required. Furthermore, Denby Transport asserted that two Eco-Links would replace three standard semi-trailer trucks while, if limited to the current UK weight limit of 97,000 lb (44 t), it was claimed the Eco-Link would reduce carbon emissions by 16% and could still halve the number of trips needed for the same amount of cargo carried in conventional semi-trailer trucks. This is based on the fact that for light but bulky goods such as toilet paper, plastic bottles, cereals and aluminum cans, conventional semi-trailer trucks run out of cargo space before they reach the weight limit. At 97,000 lb (44 t), as opposed to 132,000 lb usually associated with B-Trains, the Eco-Link also exerts less weight per axle on the road compared to the standard six-axle 97,000 lb (44 t) semi-trailer truck.[citation needed]

The vehicle was built after Denby Transport believed they had found a legal-loophole in the present UK law to allow the Eco-Link to be used on the public roads. The relevant legislation concerned the 1986 Road Vehicles Construction and Use Regulations. The 1986 regulations state that "certain vehicles" may be permitted to draw more than one trailer and can be up to 85 ft (25.9 m).[citation needed] The point of law reportedly hinged on the definition of a "towing implement", with Denby prepared to argue that the second trailer on the Eco-Link was one. The Department for Transport were of the opinion that this refers to recovering a vehicle after an accident or breakdown, but the regulation does not explicitly state this.[citation needed]

During BTAC performance testing the Eco-Link was given an "excellent" rating for its performance in maneuverability, productivity, safety and emissions tests, exceeding ordinary semi-trailer trucks in many respects. Reportedly, private trials had also shown the Denby vehicle had a 20% shorter stopping distance than conventional semi-trailer trucks of the same weight, due to having extra axles. The active steer system meant that the Eco-Link had a turning circle of 41 ft (12.5 m), the same as a conventional semi-trailer truck.[citation needed]

Although the Department for Transport advised that the Eco-Link was not permissible on public roads, Denby Transport gave the Police prior warning of the timing and route of the test drive on the public highway, as well as outlining their position in writing to the Eastern Traffic Area Office. On 1 December 2009 Denby Transport were preparing to drive the Eco-Link on public roads, but this was cut short because the Police pulled the semi-trailer truck over as it left the gates in order to test it for its legality "to investigate any... offenses which may be found". The Police said the vehicle was unlawful due to its length and Denby Transport was served with a notice by the Vehicle and Operator Services Agency (VOSA) inspector to remove the vehicle from the road for inspection. Having returned to the yard, Denby Transport was formally notified by Police and VOSA that the semi-trailer truck could not be used. Neither the Eco-Link, nor any other B-Train, have since been permitted on UK roads. However, this prompted the Department for Transport to undertake a desk study into semi-trailer trucks, which has resulted in the longer semi-trailer trial which commenced in 2012.[citation needed]

North America

[edit]

In North America, the combination vehicles made up of a powered truck tractor and one or more semitrailers are known as "semis", "semitrailers",[26] "tractor-trailers", "big rigs", "semi-trucks", "eighteen-wheelers", or "semi-tractor-trailers".[citation needed]

The tractor unit typically has two or three axles; those built for hauling heavy-duty commercial-construction machinery may have as many as five, some often being lift axles.[27]

The most common tractor-cab layout has a forward engine, one steering axle, and two drive axles. The fifth-wheel trailer coupling on most tractor trucks is movable fore and aft, to allow adjustment in the weight distribution over its rear axle(s).[citation needed]

Ubiquitous in Europe but less common in North America since the 1990s, is the cabover engine configuration, where the driver sits next to or over the engine. With changes in the US to the maximum length of the combined vehicle, the cabover was largely phased out of North American over-the-road (long-haul) service by 2007. Cabovers were difficult to service; for a long time, the cab could not be lifted on its hinges to a full 90-degree forward tilt, severely limiting access to the front of the engine.[citation needed]

As of 25 May 2016[update], a truck could cost US$100,000, while the diesel fuel cost could be $70,000 per year.[28] Trucks average from 4 to 8 miles per US gallon (59 to 29 L/100 km), with fuel economy standards requiring better than 7 miles per US gallon (34 L/100 km) efficiency by 2014.[29] Power requirements in standard conditions are 170 hp (130 kW) at 55 mph (89 km/h) or 280 hp (210 kW) at 70 mph (113 km/h), and somewhat different power usage in other conditions.[30]

The cargo trailer usually has tandem axles at the rear, each of which has dual wheels, or eight tires on the trailer, four per axle. In the US it is common to refer to the number of wheel hubs, rather than the number of tires; an axle can have either single or dual tires with no legal difference.[31][32] The combination of eight tires on the trailer and ten tires on the tractor is what led to the moniker eighteen wheeler, although this term is considered by some truckers to be a misnomer (the term "eighteen-wheeler" is a nickname for a five-axle over-the-road combination). Many trailers are equipped with movable tandem axles to allow adjusting the weight distribution.[citation needed]

To connect the second of a set of doubles to the first trailer, and to support the front half of the second trailer, a converter gear known as a "dolly" is used. This has one or two axles, a fifth-wheel coupling for the rear trailer, and a tongue with a ring-hitch coupling for the forward trailer. Individual states may further allow longer vehicles, known as "longer combination vehicles" (LCVs), and may allow them to operate on roads other than Interstates.[citation needed]

Long combination vehicle types include:

- Doubles (officially "STAA doubles", known colloquially as "a set of joints"): Two 28.5 ft (8.7 m) trailers.

- B-Doubles: Twin 33 ft (10.1 m) trailers in B-double configuration (very common in Canada but rarely used in the United States).

- Triples: Three 28.5 ft (8.7 m) trailers.

- Turnpike Doubles: Two 40 ft (12.2 m) – 53 ft (16.2 m) trailers.

- Rocky Mountain Doubles: One 40 to 53 ft (12.2 to 16.2 m) trailer (though usually no more than 48 ft (14.6 m)) and one 28.5 ft (8.7 m) trailer (known as a "pup").

- In Canada, a Turnpike Double is two 53 ft (16.2 m) trailers, and a Rocky Mountain Double is a 50 ft (15.2 m) trailer with a 24 ft (7.3 m) "pup".[33][34][35]

The US federal government, which only regulates the Interstate Highway System, does not set maximum length requirements (except on auto and boat transporters), only minimums. Tractors can pull two or three trailers if the combination is legal in that state. Weight maximums are 20,000 lb (9,100 kg) on a single axle, 34,000 lb (15,000 kg) on a tandem, and 80,000 lb (36,000 kg) total for any vehicle or combination. There is a maximum width of 8.5 ft (2.6 m) and no maximum height.[36][37]

Roads other than Interstates are regulated by individual states, and laws vary widely. Maximum weight varies between 80,000 lb (36,000 kg) to 171,000 lb (78,000 kg), depending on the combination.[38] Most states restrict operation of larger tandem trailer setups such as triple units, turnpike doubles, and Rocky Mountain doubles. Reasons for limiting the legal trailer configurations include safety concerns and the impracticality of designing and constructing roads that can accommodate the larger wheelbase of these vehicles and the larger minimum turning radii associated with them. In general, these configurations are restricted to the Interstates. Except for these units, double setups are not restricted to certain roads any more than a single setup. They are also not restricted by weather conditions or "difficulty of operation". The Canadian province of Ontario, however, does have weather-related operating restrictions for larger tandem trailer setups.[39]

Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]Australian road transport has a reputation for using very large trucks and road trains. This is reflected in the most popular configurations of trucks generally having dual drive axles and three axles on the trailers, with four tyres on each axle. This means that Australian single semi-trailer trucks will usually have 22 tyres, which is generally more than their counterparts in other countries. Super single tyres are sometimes used on tri-axle trailers. The suspension is designed with travel limiting, which will hold the rim off the road for one blown or deflated tyre for each side of the trailer, so a trailer can be driven at reduced speed to a safe place for repair. Super singles are also often used on the steer axle in Australia to allow greater loading over the steer axle. The increase in loading of steer tyres requires a permit.[citation needed]

Long haul transport usually operates as B-doubles with two trailers (each with three axles), for a total of nine axles (including steering). In some lighter duty applications, only one of the rear axles of the truck is driven, and the trailer may have only two axles. From July 2007, the Australian Federal and State Governments allowed the introduction of B-triple trucks on a specified network of roads.[40] B-Triples are set up differently from conventional road trains. The front of their first trailer is supported by the turntable on the prime mover. The second and third trailers are supported by turntables on the trailers in front of them. As a result, B-Triples are much more stable than road trains and handle exceptionally well. True road trains only operate in remote areas, regulated by each state or territory government.[citation needed]

In total, the maximum length that any articulated vehicle may be (without a special permit and escort) is 53.5 m (176 ft), its maximum load may be up to 164 tonnes gross, and may have up to four trailers. However, heavy restrictions apply to the areas where such a vehicle may travel in most states. In remote areas such as the Northern Territory great care must be taken when sharing the road with longer articulated vehicles that often travel during the daytime, especially four-trailer road trains.[citation needed]

Articulated trucks towing a single trailer or two trailers (commonly known as "short doubles") with a maximum overall length of 19 m (62 ft) are referred to as "General access heavy vehicles" and are permitted in all areas, including metropolitan. B-doubles are limited to a maximum total weight of 62.5 tonnes and overall length of 25 m (82 ft), or 26 m (85 ft) if they are fitted with approved FUPS (Front Underrun Protection System) devices. B-doubles may only operate on designated roads, which includes most highways and some major metropolitan roads. B-doubles are very common in all parts of Australia including state capitals and on major routes they outnumber single trailer configurations.[citation needed]

Maximum width of any vehicle is 2.5 m (8.2 ft) and a height of 4.3 m (14 ft). In the past few years, allowance has been made by several states to allow certain designs of heavy vehicles up to 4.6 m (15 ft) high but they are also restricted to designated routes. In effect, a 4.6 meter high B-double will have to follow two sets of rules: they may access only those roads that are permitted for B-doubles and for 4.6 meter high vehicles.[citation needed]

In Australia, both conventional prime movers and cabovers are common, however, cabovers are most often seen on B-doubles on the eastern seaboard where the reduction in total length allows the vehicle to pull longer trailers and thus more cargo than it would otherwise.[citation needed]

-

An Australian prime mover Kenworth and B double trailer combination

-

Volvo road train in Australia

-

B-double truck on the Sturt Highway

New Zealand

[edit]New Zealand legislation governing truck dimensions falls under the Vehicle Dimensions and Mass Rules, published by NZ Transport Agency.[41] New rules were introduced effective 1 February 2017,[42] which increased the maximum height, width and weight of loads and vehicles, to simplify regulations, increase the amount of freight carried by road, and to improve the range of vehicles and trailers available to transport operators.[citation needed]

Common combinations in New Zealand are a standard semi-trailer, a B-train, or a rigid towing vehicle pulling a trailer with a drawbar, with a maximum of nine axles. Standard maximum vehicle lengths for trailers with one axle set are:

- Semi-trailer: 19 m (62 ft)

- Simple: 22 m (72 ft)

- Pole: 20 m (66 ft)

Trailers with two axle sets can be 20 m (66 ft) long, including heavy rigid vehicles towing two trailers. Oversized loads require, at minimum, a permit, and may require one or more pilot vehicles.[43]

High-productivity motor vehicle (HPMV) permits are issued for vehicles exceeding 44 tonnes, or the above dimensions.[44] Trucks up to 62 tonnes were allowed, with an initial bridge strengthening program costing $12.5m.[45]

Construction

[edit]

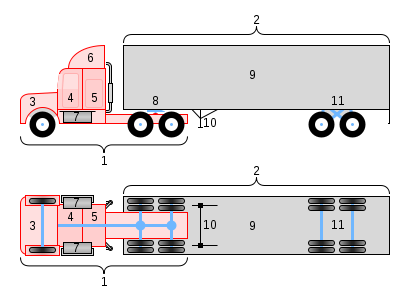

1. tractor unit

2. semi-trailer (detachable)

3. engine compartment

4. cabin

5. sleeper (not present in all trucks)

6. air dam (not present in all trucks)

7. fuel tanks

8. fifth wheel coupling

9. enclosed cargo space

10. landing gear – legs for when semi-trailer is detached

11. tandem axles

Types of trailers

[edit]There are many types of semi-trailers in use, designed to haul a wide range of products.

Coupling and uncoupling

[edit]The cargo trailer is, by means of a king pin, hooked to a horseshoe-shaped quick-release coupling device called a fifth wheel or a turntable hitch at the rear of the towing engine that allows easy hook up and release. The truck trailer cannot move by itself because it only has wheels at the rear end: it requires a forward axle, provided by the towing engine, to carry half the load weight. When braking hard at high speeds, the vehicle has a tendency to fold at the pivot point between the towing vehicle and the trailer. Such a truck accident is called a "trailer swing", although it is also commonly described as a "jackknife."[46] Jackknifing is a condition where the tractive unit swings round against the trailer, and not vice versa.

Braking

[edit]

Semi trucks use air pressure, rather than hydraulic fluid, to actuate the brake. The use of air hoses allows for ease of coupling and uncoupling of trailers from the tractor unit. The most common failure is brake fade, usually caused when the drums or discs and the linings of the brakes overheat from excessive use.

The parking brake of the tractor unit and the emergency brake of the trailer are spring brakes that require air pressure in order to be released. They are applied when air pressure is released from the system, and disengaged when air pressure is supplied. This is a fail-safe design feature which ensures that if air pressure to either unit is lost, the vehicle will stop to a grinding halt, instead of continuing without brakes and becoming uncontrollable. The trailer controls are coupled to the tractor through two gladhand connectors, which provide air pressure, and an electrical cable, which provides power to the lights and any specialized features of the trailer.

Glad-hand connectors (also known as palm couplings) are air hose connectors, each of which has a flat engaging face and retaining tabs. The faces are placed together, and the units are rotated so that the tabs engage each other to hold the connectors together. This arrangement provides a secure connection but allows the couplers to break away without damaging the equipment if they are pulled, as may happen when the tractor and trailer are separated without first uncoupling the air lines. These connectors are similar in design to the ones used for a similar purpose between railroad cars. Two air lines typically connect to the trailer unit. An emergency or main air supply line pressurizes the trailer's air tank and disengages the emergency brake, and a second service line controls the brake application during normal operation.

In the UK, male/female quick release connectors (red line or emergency), have a female on the truck and male on the trailer, but a yellow line or service has a male on the truck and female on the trailer. This avoids coupling errors (causing no brakes) plus the connections will not come apart if pulled by accident. The three electrical lines will fit one way around a primary black, a secondary green, and an ABS lead, all of which are collectively known as suzies or suzie coils.

In New Zealand all trucks and trailers use a DUOMATIC air coupler which has female receivers mounted on the truck/tractor and on the trailer, and male on both ends of the suzie lines (they can be completely removed and stored in the cab to prevent theft). Connecting the red and blue lines is one operation at each end. The red and blue lines are always on the same side of every fitting so they can never hook up in reverse or the wrong way around. The same system is used in Europe.

Another braking feature of semi-trucks is engine braking, which could be either a compression brake (usually shortened to Jake brake) or exhaust brake or combination of both. However, the use of compression brake alone produces a loud and distinctive noise, and to control noise pollution, some local municipalities have prohibited or restricted the use of engine brake systems inside their jurisdictions, particularly in residential areas. The advantage to using engine braking instead of conventional brakes is that a truck can descend a long grade without overheating its wheel brakes. Some vehicles can also be equipped with hydraulic or electric retarders which have an advantage of near silent operation.

Transmission

[edit]

Because of the wide variety of loads the semi may carry, they usually have a manual transmission to allow the driver to have as much control as possible. However, all truck manufacturers now offer automated manual transmissions (manual gearboxes with automated gear change), as well as conventional hydraulic automatic transmissions.

Semi-truck transmissions can have as few as three forward speeds or as many as 18 forward speeds (plus 2 reverse speeds). A large number of transmission ratios means the driver can operate the engine more efficiently. Modern on-highway diesel engines are designed to provide maximum torque in a narrow RPM range (usually 1200–1500 RPM); having more gear ratios means the driver can hold the engine in its optimum range regardless of road speed (drive axle ratio must also be considered).

A ten-speed manual transmission, for example, is controlled via a six-slot H-box pattern, similar to that in five-speed cars — five forward and one reverse gear. Gears six to ten (and high-speed reverse) are accessed by a Lo/High range splitter; gears one to five are Lo range; gears six to ten are High range using the same shift pattern. A Super-10 transmission, by contrast, has no range splitter; it uses alternating "stick and button" shifting (stick shifts 1-3-5-7-9, button shifts 2-4-6-8-10). The 13-, 15-, and 18-speed transmissions have the same basic shift pattern but include a splitter button to enable additional ratios found in each range. Some transmissions may have 12 speeds.

Another difference between semi-trucks and cars is the way the clutch is set up. On an automobile, the clutch pedal is depressed full stroke to the floor for every gear shift, to ensure the gearbox is disengaged from the engine. On a semi-truck with constant-mesh transmission (non-synchronized), such as by the Eaton Roadranger series, not only is double-clutching required, but a clutch brake is required as well. The clutch brake stops the rotation of the gears and allows the truck to be put into gear without grinding when stationary. The clutch is pressed to the floor only to allow a smooth engagement of low gears when starting from a full stop; when the truck is moving, the clutch pedal is pressed only far enough to break torque for gear changes.

Theoretically, semi-trucks could have diesel-electric transmission, as electric motors have better torque at 0 RPM than diesel engines, but this would significantly increase the weight of the truck itself, above the maximum legal weight for road vehicles.[47]

Lights

[edit]An electrical connection is made between the tractor and the trailer through a cable often referred to as a pigtail. This cable is a bundle of wires in a single casing. Each wire controls one of the electrical circuits on the trailer, such as running lights, brake lights, turn signals, etc. A coiled cable is used which retracts these coils when not under tension, such as when not cornering. It is these coils that cause the cable to look like a pigtail.

In most countries, a trailer or semi-trailer must have minimum

- 2 rear lights (red)

- 2 stop lights (red)

- 2 turning lights; one for right and one for left, flashing (amber; red optional in North America. May be combined with a brake light in North America)

- 2 marking lights behind if wider than certain specifications (red; plus a group of 3 red lights in the middle in North America)

- 2 marking lights front if wider than the truck or wider than certain specifications (white; amber in North America)

Wheels and tires

[edit]Although dual wheels are the most common, use of two single, wider tires, known as super singles, on each axle is becoming popular among bulk cargo carriers and other weight-sensitive operators. With increased efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the use of the super-single tire is gaining popularity. There are several advantages to this configuration. The first of these is that super singles reduce fuel consumption. In 1999, tests on an oval track showed a 10% fuel savings when super singles were used. These savings are realized because less energy is wasted flexing fewer tire sidewalls. Second, the lighter overall tire weight allows a truck to be loaded with more freight. The third advantage is that the single wheel encloses less of the brake unit, which allows faster cooling and reduces brake fade.

In Europe, super singles became popular when the allowed weight of semitrailer rigs was increased from 38 to 40 tonnes.[48] In this reform the trailer industry replaced two 10-tonne (22,000 lb) axles with dual wheels, with three 8-tonne (18,000 lb) axles on wide-base single wheels. The significantly lower axle weight on super singles must be considered when comparing road wear from single versus dual wheels. The majority of super singles sold in Europe have a width of 385 mm (15.2 in). The standard 385 tires have a legal load limit of 4,500 kg (9,900 lb). (Note that expensive, specially reinforced 385 tires approved for 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) do exist. Their market share is tiny, except for mounting on the steer axle.)

Skirted trailers

[edit]An innovation rapidly growing in popularity is the skirted trailer. The space between the road and the bottom of the trailer frame was traditionally left open until it was realized that the turbulent air swirling under the trailer is a major source of aerodynamic drag. Three split skirt concepts were verified by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to provide fuel savings greater than 5%, and four split skirt concepts had EPA-verified fuel savings between 4% and 5%.[49]

Skirted trailers are often combined with Underrun Protection Systems (underride guards), greatly improving safety for passenger vehicles sharing the road.

Underride guard

[edit]

Underride protection systems can be installed at the rear, front and sides of a truck and the rear and sides of a trailer. A Rear Underrun Protection System (RUPS) is a rigid assembly hanging down from trailer's chassis, which is intended to provide some protection for passenger cars which collide with the rear of the trailer. Public awareness of this safeguard was increased in the aftermath of the accident that killed actress Jayne Mansfield on 29 June 1967, when the car she was in hit the rear of a tractor-trailer, causing fatal head trauma. After her death, the NHTSA proposed requiring a rear underride guard, also known as a Mansfield bar, an ICC bar, or a DOT bumper.[50][51] The proposal to mandate rear underride guards was withdrawn in 1971 after strong lobbying and opposition by the trucking industry,[52] and so they were not federally mandated until 1996; that mandate did not go into effect until 1998.[53]

The bottom rear of the trailer is near head level for an adult seated in a car, and without the underride guard, the only protection for such an adult's head in a rear-end collision would be the car's windshield and A pillars. The front of the car goes under the platform of the trailer rather than making contact via the passenger car bumper, so the car's protective crush zone becomes irrelevant and air bags are ineffective in protecting the passengers. If installed, the underride guard can provide a rigid area for the car to contact that is lower than the lip of the bonnet/hood, thus preventing the vehicle from squatting and running under the truck, instead ensuring that the vehicle's crush zones and engine block can absorb the force of the collision.

In addition to rear underride guards, truck tractor cabs may be equipped with a Front Underrun Protection System (FUPS) at the front bumper of the truck, if the front end is not low enough for the bumper to provide the adequate protection on its own. The safest tractor-trailers are also equipped with side underride guards, also called Side Underrun Protection System (SUPS). These additional barriers prevent passenger cars from skidding underneath the trailer from the side, such as in an oblique or side collision, or if the trailer jackknifes across the road, and this also helps protect cyclists, pedestrians, and other vulnerable road users.[54] In the 1969 proposal for rear underride guards, the Federal Highway Administration indicated that, "It is anticipated that the proposed [rear underride guard] standard will be amended, after technical studies have been completed, to extend the requirement for underride protection to the sides of large vehicles".[55] However, to date, a side underride guard mandate has yet to ever be proposed by the USDOT or NHTSA. In fact, for side underride guards, NHTSA has disregarded successful crash tests that stop a passenger vehicle from underriding a semitrailer,[56][57] ignored recommendations,[58] disregarded administrative petitions,[59] and denied petitions.[60][61] In fact, for decades NHTSA has ignored credible scientific research on side underride guards and failed to take simple steps to stop these crashes.[62]

In Europe, side and rear underrun protection are mandated on all lorries and trailers with a gross weight of 3,500 kilograms (7,700 lb) or more.[63] Several US states and cities have adopted or are in the process of adopting truck side guards, including New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington DC. The NTSB has recommended that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) develop standards for side underride protection systems for trucks, and for newly manufactured trucks to be equipped with technology meeting the standards.[64]

In addition to safety benefits, these underride guards may improve fuel mileage by reducing air turbulence under the trailer at highway speeds. Another benefit of having a sturdy rear underride guard is that it may be secured to a loading dock with a hook to prevent "trailer creep", a movement of the trailer away from the dock, which opens up a dangerous gap during loading or unloading operations.[65]

Semi-truck manufacturers

[edit]Current semi-truck manufacturers include:

Asia-Pacific

[edit]- Ashok Leyland (India)

- BharatBenz (India)

- C&C Trucks (China)

- CAMC Hanma (China)

- China National Heavy Duty Truck Group (China)

- Dongfeng Trucks (China)

- Eicher Motors (India)

- FAW Group (China)

- Foton Motor (China)

- Fuso (Japan)

- Hino (Japan)

- Hyundai (South Korea)

- Isuzu (Japan)

- JAC Motors (China)

- Mahindra Truck and Bus Division (India)

- SAIC Hongyan (China)

- Shacman (China)

- Tata Daewoo (South Korea-India)

- Tata Motors (India)

- UD Trucks (Japan)

- XCMG Hanvan (China)

Canada and United States

[edit]Europe

[edit]Other locations

[edit]- BMC (Turkey)

- Ford Otosan (Turkey)

- Kamaz (Russia)

- MAZ (Belarus)

- Volkswagen (Latin America, South Africa)

Former semi-truck manufacturers include:

Driver's license

[edit]

A special driver's license is required to operate various commercial vehicles.

Australia

[edit]Truck drivers in Australia require an endorsed license. These endorsements are gained through training and experience. The minimum age to hold an endorsed license is 18 years, and/or must have held open (full) driver's license for minimum 12 months.

The following are the heavy vehicle license classes in Australia:

- LR (Light Rigid) – Class LR covers a rigid vehicle with a GVM (gross vehicle mass) of more than 4.5 tonnes but not more than 8 tonnes. Any towed trailer must not weigh more than 9 tonnes GVM. Also includes vehicles with a GVM up to 8 tonnes which carry more than 12 adults including the driver and vehicles in Class C.

- MR (Medium Rigid) – Class MR covers a rigid vehicle with two axles and a GVM of more than 8 tonnes. Any towed trailer must not weigh more than 9 tonnes GVM. Also includes vehicles in Class LR.

- HR (Heavy Rigid) – Class HR covers a rigid vehicle with three or more axles and a GVM of more than 15 tonnes. Any towed trailer must not weigh more than 9 tonnes GVM. Also includes articulated buses and vehicles in Class MR.

- HC (Heavy Combination) – Class HC covers heavy combination vehicles like a prime mover towing a semi-trailer, or rigid vehicles towing a trailer with a GVM of more than 9 tonnes. Also includes vehicles in Class HR.

- MC (Multi Combination) – Class MC covers multi-combination vehicles like road trains and B-double vehicles. Also includes vehicles in Class HC.

In order to obtain an HC License the driver must have held an MR or HR license for at least 12 months. To upgrade to an MC License the driver must have held a HR or HC license for at least 12 months. From licenses MR and upward there is also a B Condition which may apply to the license if testing in a synchromesh or automatic transmission vehicle. The B Condition may be removed upon the driver proving the ability to drive a constant mesh transmission using the clutch. Constant mesh transmission refers to crash box transmissions, predominantly Road Ranger eighteen-speed transmissions in Australia.

Canada

[edit]Regulations vary by province. A license to operate a vehicle with air brakes is required (i.e., normally a Class I, II, or III commercial license with an "A" or "S" endorsement in provinces other than Ontario). In Ontario, a "Z" endorsement[66] is required to drive any vehicle using air brakes; in provinces other than Ontario, the "A" endorsement is for air brake operation only, and an "S" endorsement is for both operation and adjustment of air brakes. Anyone holding a valid Ontario driver's license (i.e., excluding a motorcycle license) with a "Z" endorsement can legally drive any air-brake-equipped truck-trailer combination with a registered- or actual-gross-vehicle-weight (i.e., including towing- and towed-vehicle) up to 11 tonnes, that includes one trailer weighing no more than 4.6 tonnes if the license falls under the following three classes: Class E (school bus—maximum 24-passenger capacity or ambulance), F (regular bus—maximum 24-passenger capacity or ambulance) or G (car, van, or small-truck).

A Class B (any school bus), C (any urban-transit-vehicle or highway-coach), or D (heavy trucks other than tractor-trailers) license enables its holder to drive any truck-trailer combination with a registered- or actual-gross-vehicle-weight (i.e., including towing- and towed-vehicle) greater than 11 tonnes, that includes one trailer weighing no more than 4.6 tonnes.[67] Anyone holding an Ontario Class A license (or its equivalent) can drive any truck-trailer combination with a registered- or actual-gross-vehicle-weight (i.e., including towing- and towed-vehicles) greater than 11 tonnes, that includes one or more trailers weighing more than 4.6 tonnes.

Europe

[edit]A category CE driving licence is required to drive a tractor-trailer in Europe. Category C (Γ in Greece) is required for vehicles over 7,500 kg (16,500 lb), while category E is for heavy trailers, which in the case of trucks and buses means any trailer over 750 kg (1,650 lb). Vehicles over 3,500 kg (7,700 lb)—which is the maximum limit of B license—but under 7,500 kg can be driven with a C1 license. Buses require a D (Δ in Greece) license. A bus that is registered for no more than 16 passengers, excluding the driver, can be driven with a D1 license.

New Zealand

[edit]In New Zealand, drivers of heavy vehicles require specific licenses, termed as classes. A Class 1 license (car license) will allow the driving of any vehicle with Gross Laden Weight (GLW) or Gross Combination Weight (GCW) of 6,000 kg (13,000 lb) or less. For other types of vehicles the classes are separately licensed as follows:

- Class 2 – Medium Rigid Vehicle: Any rigid vehicle with GLW 18,001 kg (39,685 lb) or less with light trailer of 3,500 kg (7,700 lb) or less, any combination vehicle with GCW 12,001 kg (26,458 lb) or less, any rigid vehicle of any weight with no more than two axles, or any Class 1 vehicle.

- Class 3 – Medium Combination Vehicle: Any combination vehicle of GCW 25,001 kg (55,118 lb) or less, or any Class 2 vehicle.

- Class 4 – Heavy Rigid Vehicle: Any rigid vehicle of any weight, any combination vehicle which consists of a heavy vehicle and a light trailer, or any vehicle of Class 1 or 2 (but not 3).

- Class 5 – Heavy Combination Vehicle: Any combination vehicle of any weight, and any vehicle covered by previous classes.

- Class 6 – Motorcycle.

Further information on the New Zealand licensing system for heavy vehicles can be found at the New Zealand Transport Agency.

Taiwan

[edit]

The Road Traffic Security Rules (道路交通安全規則) require a combination vehicle driver license (Chinese: 聯結車駕駛執照) to drive a combination vehicle (Chinese: 聯結車). These rules define a combination vehicle as a motor vehicle towing a heavy trailer, i.e., a trailer with a gross weight of more than 750 kilograms (1,653 lb).

United States

[edit]Drivers of semi-trailer trucks generally require a Class A commercial driver's license (CDL) to operate any combination vehicles with a gross combination weight rating (or GCWR) in excess of 26,000 lb (11,800 kg) if the gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) of the towed vehicle(s) is in excess of 10,000 lb (4,500 kg).[68] Some states (such as North Dakota) provide exemptions for farmers, allowing non-commercial license holders to operate semis within a certain air-mile radius of their reporting location. State exemptions, however, are only applicable in intrastate commerce; stipulations of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) may be applied in interstate commerce. Also a person under the age of 21 cannot operate a commercial vehicle outside the state where the commercial license was issued. This restriction may also be mirrored by certain states in their intrastate regulations. A person must be at least 18 in order to be issued a commercial license.

In addition, endorsements are necessary for certain cargo and vehicle arrangements and types;

- H – Hazardous Materials (HazMat or HM) – necessary if materials require HM placards.

- N – Tankers – the driver is acquainted with the unique handling characteristics of liquids tankers.

- X – Signifies Hazardous Materials and Tanker endorsements, combined.

- T – Doubles & Triples – the licensee may pull more than one trailer.

- P – Buses – Any Vehicle designed to transport 16 or more passengers (including the driver).

- S – School Buses – Any school bus designed to transport 11 or more passengers (including the driver).

- W – Tow Truck

Role in trade

[edit]Modern day semi-trailer trucks often operate as a part of a domestic or international transport infrastructure to support containerized cargo shipment.

Various types of rail flat bed train cars are modified to hold the cargo trailer or container with wheels or without. This is called Intermodal or piggyback. The system allows the cargo to switch from highway to railway or vice versa with relative ease by using gantry cranes.

The large trailers pulled by a tractor unit come in many styles, lengths, and shapes. Some common types are: vans, reefers, flatbeds, sidelifts and tankers. These trailers may be refrigerated, heated, ventilated, or pressurized, depending on climate and cargo. Some trailers have movable wheel axles that can be adjusted by moving them on a track underneath the trailer body and securing them in place with large pins. The purpose of this is to help adjust weight distribution over the various axles, to comply with local laws.

Media

[edit]Television

[edit]- 1960s TV series Cannonball

- NBC ran two popular TV series about truck drivers in the 1970s featuring actor Claude Akins in major roles:

- Movin' On (1974–1976)

- B. J. and the Bear (1978–1981)

- The Highwayman (1987–1988), a semi-futuristic action-adventure series starring Sam Jones, featuring hi-tech, multi-function trucks.

- Knight Rider, an American television show featured a semi-trailer truck called The Semi, operated by the Foundation for Law & Government (F.L.A.G.) as a mobile support facility for KITT. Also, in two episodes KITT faced off against an armored semi called Goliath.

- The Transformers, a 1980s cartoon featuring tractor-trailer trucks as the alternate modes for the Autobots' leader Optimus Prime (Convoy in Japanese version), their second-in-command Ultra Magnus, and as the Stunticons' leader Motormaster. Optimus Prime returned in the 2007 film.

- Trick My Truck, a CMT show features trucks getting 'tricked out' (heavily customized).

- Ice Road Truckers, a History Channel show charts the lives of drivers who haul supplies to remote towns and work sites over frozen lakes that double as roads.

- 18 Wheels of Justice, featuring Federal Agent Michael Cates (Lucky Vanous) as a crown witness for the mafia who goes undercover, when forced into it, to fight crime.

- Eddie Stobart: Trucks & Trailers, a UK television show showing the trucking company Eddie Stobart and its drivers.

- Highway Thru Hell, a Canadian reality TV show that follows the operations of Jamie Davis Motor Trucking, a heavy vehicle rescue and recovery towing company based in Hope, British Columbia.

Films

[edit]- Duel, Steven Spielberg's 1971 film, features a Peterbilt 281 tanker truck as the villain

- White Line Fever, a 1975 Columbia Pictures film, starring Jan-Michael Vincent

- Smokey and the Bandit, a 1977 film featuring a number of trucks on the side of the bandit

- Convoy, a 1978 film directed by Sam Peckinpah, starring Kris Kristofferson

- Mad Max 2, George Miller's 1981 film, features the titular character driving a Mack R series truck

- Maximum Overdrive, Stephen King's 1986 film, featured big rigs as its primary homicidal villains

- Over the Top (1987 film), a 1987 film directed by Menahem Golan, starring Sylvester Stallone

- Black Dog, a 1998 film directed by Kevin Hooks, starring Patrick Swayze

- Prime Mover, a 2008 film directed by David Caesar

- Joy Ride, a 2001 film directed by John Dahl, starring Paul Walker and Steve Zahn

- Big Rig, a 2008 documentary film directed by Doug Pray

Music

[edit]- "Convoy", a pop song by C. W. McCall, spurred sales of CB radios with an imaginary trucking story.

- The eighteen-wheeled truck was immortalized in numerous country music songs, such as the Red Sovine titles "Giddyup Go", "Teddy Bear" and "Phantom 309", and Dave Dudley's "Six Days on the Road".

- The thrash metal band, BigRig, was named after these trucks.

- Country song "Eighteen Wheels and a Dozen Roses", made popular in 1987 by singer-songwriter Kathy Mattea.

- "Roll On (Eighteen Wheeler)" by Alabama tells the story of a trucker who calls home to his family every night while out on the road.

- "Papa Loved Mama" by Garth Brooks is about a trucker and his wife.

- "Truck Drivin' Song" by "Weird Al" Yankovic tells the story of a female trucker, sung by a male with a deep voice.

- "Cold Shoulder" by Garth Brooks is about a trucker stuck on the side of the highway during a blizzard, fantasizing about being home with his wife.

- "Drivin' My Life Away" by Eddie Rabbitt, a former trucker, co-written with Even Stevens and David Malloy, sings of the life on the road.

Video games and truck simulators

[edit]Podcasts

[edit]- Over the Road, a podcast series by Radiotopia on truck driving the North America / US

See also

[edit]- Air brake (road vehicle)

- Articulated lorries

- Articulated vehicle

- Brake

- Bus

- Cab over

- Containerization

- DAT Solutions (a.k.a. Dial-a-truck)

- Dolly (trailer)

- Drayage

- Dump truck

- Gladhand connector

- Hybrid vehicle

- Jackknifing

- List of trucks

- Loader crane

- Loading dock

- Lockrod

- Logging truck

- Long combination vehicle

- Oversize load

- Progressive shifting

- Refrigerator truck ("reefer")

- Road train

- Roll trailer

- Semi-trailer

- Terminal tractor

- Tank truck

- Tractor unit

- Trailer (vehicle)

- Trailer bus

- Train

- Truck

- Truck driver

- Truck sleeper

References

[edit]- ^ "semitrailer". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "semitruck". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "semi". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "Big rig Definition & Meaning". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "tractor-trailer". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "eighteen-wheeler". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "articulated lorry". Cambridge dictionary. Retrieved 1 May 2025.

- ^ "artic". Cambridge dictionary. Retrieved 1 May 2025.

- ^ "juggernaut". Cambridge dictionary. Retrieved 1 May 2025.

- ^ "Heavy goods vehicle". Cambridge dictionary. Retrieved 1 May 2025.

- ^ Kilcarr, Sean (10 August 2017). "Getting cabover crazy". American Trucker. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Mike A. (Summer 2013). "The Sales & Service Literature of Leyland Motors Ltd" (PDF). Leyland Torque (60). The Leyland Society.

- ^ Hjelm, Linus; Bergqvist, Björn (2009). "European Truck Aerodynamics – A Comparison Between Conventional and CoE Truck Aerodynamics and a Look into Future Trends and Possibilities". The Aerodynamics of Heavy Vehicles II: Trucks, Buses, and Trains. Lecture Notes in Applied and Computational Mechanics. Vol. 41. Springer. pp. 469–477. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-85070-0_45. ISBN 978-3-540-85069-4.

- ^ a b c Ramberg, K. (October 2004). "Fewer Trucks Improve the Environment" (PDF). Svenskt Näringsliv. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wideberg, J.; et al. (May 2006). "Study Of Stability Measures And Legislation Of Heavy Articulated Vehicles In Different OECD Countries" (PDF). University of Seville, KTH and Scania AB. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Två regeringsbeslut för längre och tyngre fordon". Regeringskansliet. 16 April 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ HCT as an enabler for Combined Transports – A Study on potentials of implementing HCT-vehicles in Sweden

- ^ "The next environmental improvement: Long truck rigs". Volvo Trucks. 3 October 2008.

- ^ Krantz, Olivia (2014). "Where Size Matters". Uptime (2): 8–15.

- ^ "Dispensation for 90 Tonnes Truckes is Favorable for All Concerned". Northland.eu. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013.

- ^ full law text in Finnish language, explanation by Finnish Forest Association in English, 76 tons in the newspaper

- ^ Nilsson, Stefan (28 October 2015). "104-tons Scania i finskt försök". Trailer (in Swedish). Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "Largest lorry in western Europe to start operating in Finnish Lapland". Finnish Forest Association. 26 August 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "A Guide to Haulage & Courier Vehicle Types & Weights". Returnloads.net. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "Moving goods by road". HM (UK) Revenue & Customs. 5 April 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster". 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Understanding Lift Axles in Semi-Trailer Trucks: Benefits, Regulations, and Usage". Duaparts. 1 January 2025. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ Smith, Allen (25 May 2016). "What It Really Costs to Own a Commercial Truck". Ask The Trucker. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

pay over $100,000 for your first commercial vehicle. 18-wheeler drinks .. easily more than $70,000 annually

- ^ Dyer, Ezra. "10 Things You Didn't Know About Semi Trucks". Popularmechanics.com. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "Understanding Tractor-trailer Performance" (PDF). Caterpillar. 2006. p. 5. LEGT6380.

- ^ "Guidelines on Maximum Weights and Dimensions" (PDF). Ireland Road Safety Authority. February 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ Crismon, Fred W (2001). US Military Wheeled Vehicles (3 ed.). Victory WWII Pub. p. 10. ISBN 0-970056-71-0.

- ^ "British Columbia, max. dimension of semi-trailer truck".

- ^ "Manitoba, max. dimension of semi-trailer truck" (PDF).

- ^ "Ontario, max. dimension of semi-trailer truck" (PDF).

- ^ "Commercial Vehicle Size and Weight Program". Freight Management and Operations. US Department of Transportation. May 2003. FHWA-OP-03-099. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Federal Size Regulations for Commercial Motor Vehicles". US Department of Transportation. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ Jakubicek, Paul (16 January 2015). "Top 10 Heaviest Semi Trucks in the United States and Canada". BigTruckGuide.com. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Long Combination Vehicles". Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ "Vaile Announces the B-Triple Road Network" (Press release). Ministry for the Department of Infrastructure. 9 July 2007. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008.

- ^ "Vehicle Dimensions and Mass Guide" (PDF). NZ Transport Agency.

- ^ "Vehicle dimensions and mass (VDAM) changes". 13 February 2017.

- ^ "Overdimension vehicles and loads" (PDF). NZ Transport Agency.

- ^ "Land Transport Rule – Vehicle Dimensions and Mass 2016 – Rule 41001/2016" (PDF). NZTA. 1 May 2021.

- ^ "More monster trucks to thunder along our roads". Stuff. 27 July 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Brian. "Truck Jackknife Accidents". Fried Rogers Goldberg. Fried Rogers Goldberg LLC. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "r/Trucks – Why aren't semi trucks diesel-electric like trains and busses? Genuine question". reddit. 21 May 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ "COST 334: Effects of Wide Single Tyres and Dual Tyres" (PDF). European Commission, Directorate General Transport. European Union. 29 November 2001.

- ^ Wood, Richard (2012). "EPA Smartway Verification of Trailer Undercarriage Advanced Aerodynamic Drag Reduction Technology". SAE International Journal of Commercial Vehicles. 5 (2). EPA Smartway: 607–615. doi:10.4271/2012-01-2043. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ "Underride Guard". Everything2. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- ^ United States Congressional Committee on Commerce (1997). Reauthorization of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. p. 39.

- ^ Morris, John D. (19 July 1971). "Agency Drops Safety Plan Opposed by Trucking Men". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ NHTSA, USDOT (10 July 2014). "Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards; Rear Impact Guards, Rear Impact Protection" (PDF). Federal Register. 79 (132): 39362–39363. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2023 – via National Archives.

- ^ Cottingham, Darren (2 December 2019). "What does side underrun protection do on trucks and trailers?". Driver Knowledge Tests. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023.

- ^ NHTSA, USDOT (19 March 1969). "Motor Vehicle Safety Standards; Rear Underride Protection; Trailers and Trucks with Gross Vehicle Weight Rating Over 10,000 Pounds" (PDF). Federal Register. 53 (34): 5383–5384. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2023 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Side guard on semitrailer prevents underride in 40 mph test". IIHS-HLDI. 29 August 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Charles (29 September 2017). "Wabash prototype: Side underride guard with aero skirt". Trailer Body Builders. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ National Transportation Safety Board (3 April 2014). "Safety Recommendations" (PDF). Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ NHTSA, USDOT (10 July 2014). "Grant of petition for rulemaking". Federal Register. 79 (132): 39362–39363 – via National Archives.

- ^ NHTSA, USDOT (24 September 1979). "Denial of a petition for rulemaking" (PDF). Federal Register. 44 (1): 55077–55078 – via National Archives.

- ^ NHTSA, USDOT (5 July 2022). "Denial of petition for a defect investigation". Federal Register. 87 (1): 39899–39901 – via National Archives.

- ^ Thompson, A. C.; Mehrotra, Kartikay; Ingram, Julia (13 June 2023). "Trapped Under Trucks: The Inside Story of the Government's Failure to Prevent Underride Crashes". ProPublica. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ "Heavy goods vehicles". MOBILITY AND TRANSPORT, Road Safety. European Commission. 17 October 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ The National Law Review (17 August 2019). "U.S. Slow to Require Side Underride Guards on Trucks". Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Underride Guard on Everything2; Retrieved: 29 November 2007.

- ^ "Ministry of Transportation | ontario.ca". www.ontario.ca. Archived from the original on 21 August 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Ontario drivers classes".

- ^ "10 Tips for Semi-Truck Drivers Obtaining Their CDL License". 5 Star Truck Sales. 7 June 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2025.

- ^ "Official Rigs of Rods Forum". Rigs of Rods. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

External links

[edit]- TruckNetUK.com, dedicated to trucking information in UK and Europe

- Ol' Blue, USA, safety and education in and around trucking in the US

- natm.com/ Promote trailer safety and the success of the trailer manufacturing industry through education and advocacy.

Semi-trailer truck

View on GrokipediaHistory

Invention and Early Adoption

The semi-trailer truck originated in 1898 when Scottish-American engineer Alexander Winton, founder of the Winton Motor Carriage Company in Cleveland, Ohio, designed the first such vehicle to transport his newly manufactured automobiles without accumulating mileage on the cars themselves.[8] [9] Winton's prototype featured a tractor unit pulling a two-wheeled trailer that transferred a portion of its load weight to the tractor via a rudimentary coupling, marking the initial shift from full trailers to semi-trailers for improved stability and load distribution.[10] He produced and sold the first commercial version in 1899, initially for auto-hauling purposes.[11] Further refinement occurred in 1914 when Detroit blacksmith August Fruehauf constructed a single-axle platform semi-trailer for lumber merchant Frederic Sibley, adapting it to a modified Ford Model T tractor to address the limitations of horse-drawn wagons on rudimentary roads.[12] [13] This design emphasized durability for heavy loads and spurred Fruehauf to establish the Fruehauf Trailer Corporation in 1918, which standardized semi-trailer production.[14] Concurrently, the fifth-wheel coupling mechanism, essential for articulating the trailer to the tractor, was patented in 1915 by Charles H. Martin of the Martin Rocking Fifth Wheel Company, with improvements by Herman Farr enabling smoother turns and load transfer; Fruehauf adopted this by 1916, facilitating broader mechanical viability.[15] [16] Early adoption remained limited through the 1900s and 1910s due to poor road infrastructure, unreliable early engines, and competition from railroads and full trailers, with semi-trucks primarily used for short-haul specialized freight like automobiles or lumber.[8] World War I accelerated limited military applications for semi-trailers in supply transport, producing around 125 variants by Fruehauf for diverse uses.[14] Post-1918, adoption expanded commercially in the 1920s as federal highway funding improved routes and diesel engines emerged, enabling longer hauls; by 1925, articulated trucks accounted for a growing share of over-the-road freight, though full regulatory standardization awaited the 1930s.[17][18]Mid-20th Century Expansion

The post-World War II economic expansion in the United States drove rapid growth in the trucking sector, as surging consumer demand for manufactured goods outpaced rail capacity and favored flexible semi-trailer configurations for door-to-door delivery.[19] By the late 1940s, wartime logistics experience had demonstrated the reliability of articulated vehicles, prompting manufacturers to scale production of diesel-powered semi-tractors capable of pulling heavier trailers over improved rural roads. This period marked a shift from short-haul applications to intercity freight, with semi-trailers increasingly used for commodities like lumber, steel, and consumer products, as evidenced by the proliferation of specialized haulers such as Peterbilt models introduced for logging in 1939 and adapted for broader commercial use post-war.[11] The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 catalyzed further expansion by funding the Interstate Highway System, a 41,000-mile network of controlled-access roads that reduced travel times and enabled semi-trucks to operate at higher speeds with minimal congestion, fundamentally altering freight economics.[20] Truck freight volumes reflected this infrastructure boost, rising from 281.6 billion ton-miles in 1960 and projected to nearly double by 1980, underscoring semi-trailers' role in capturing market share from rail.[21] In parallel, European countries pursued road modernization amid reconstruction, though stricter axle-load regulations constrained semi-trailer lengths relative to American standards, limiting expansion to regional networks until harmonized EU directives in later decades.[22] Technological refinements in the 1950s and 1960s amplified semi-trailer viability, including widespread adoption of turbocharged diesel engines for superior torque and fuel economy, alongside innovations like power steering and improved fifth-wheel couplings that enhanced maneuverability for tandem-axle setups.[23][24] Trailer interchanges and modular designs minimized cargo handling, boosting efficiency for just-in-time supply chains emerging in manufacturing hubs.[25] By the mid-1960s, the U.S. trucking workforce had swelled to approximately 8 million, with semi-trailers dominating over-the-road hauls and supporting suburbanization by enabling rapid distribution from centralized warehouses.[26] These developments solidified semi-trailers as a cornerstone of industrialized logistics, though vulnerabilities like steel shortages in the early 1940s had earlier tempered wartime scaling.[25]Post-1970s Technological and Regulatory Evolution

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) initiated federal emissions standards for heavy-duty highway diesel engines in 1974 under the Clean Air Act of 1970, targeting hydrocarbons (HC), carbon monoxide (CO), and NOx, with initial limits of 16 g/bhp·hr for HC+NOx and 40 g/bhp·hr for CO.[27] Standards tightened progressively, introducing particulate matter (PM) limits of 0.25 g/bhp·hr in 1991 and 0.10 g/bhp·hr by 1994, alongside NOx reductions to 4.0 g/bhp·hr in 1998, which spurred adoption of exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) systems.[27] Major overhauls occurred with 2004 standards cutting NOx to 2.0 g/bhp·hr and the 2007-2010 phase-in achieving 0.20 g/bhp·hr NOx and 0.01 g/bhp·hr PM, necessitating diesel particulate filters (DPF), ultra-low sulfur diesel (15 ppm), and later selective catalytic reduction (SCR).[27][28] Safety regulations advanced through National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) updates to Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS). Building on earlier underride guard requirements from the 1950s, NHTSA finalized FMVSS Nos. 223 and 224 in 1996, effective January 1998, mandating rear impact guards on trailers and semitrailers with gross vehicle weight ratings (GVWR) exceeding 10,000 pounds (4,536 kg) to withstand specified crash forces, reducing passenger vehicle underride risks.[29][30] Antilock braking systems (ABS), first commercially available on heavy-duty trucks in 1987 via Freightliner, became federally required for new tractors in March 1997 and semitrailers in March 1998 under FMVSS 121 amendments, improving stability and reducing jackknifing.[31][32] Technological responses included electronic engine controls emerging in the early 1980s, with systems like Detroit Diesel's Series 60 (introduced 1987) enabling precise fuel metering and emissions management, replacing mechanical governors for better efficiency.[33][34] Aerodynamic enhancements, such as rounded cab designs and side skirts in the 1990s, reduced drag coefficients, contributing to fuel efficiency gains; combined with low-rolling-resistance tires and powertrain optimizations, Class 8 truck efficiency doubled from the 1970s to 2010s, hauling equivalent freight with half the fuel.[28] These innovations, driven by regulatory pressures, improved operational safety and environmental compliance without compromising payload capacities standardized under the 1982 Surface Transportation Assistance Act.[28]Recent Developments (2000s–2025)

The 2000s saw significant regulatory pushes for emissions reductions in semi-trailer truck engines, primarily through U.S. EPA standards finalized in 2001 that required heavy-duty diesel engines to achieve 95% cuts in nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter by model year 2010, implemented via phased requirements starting in 2007.[35] These changes mandated widespread adoption of technologies like selective catalytic reduction (SCR) systems and diesel particulate filters, alongside ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel introduced in 2006 to enable such aftertreatment.[27] Safety evolved with the proliferation of electronic stability control (ESC) in tractors during the decade, becoming federally mandatory for new heavy combination vehicles by June 2015, which studies linked to reduced rollover incidents by improving yaw stability during evasive maneuvers.[36] Telematics adoption accelerated for compliance and efficiency, building on satellite-based systems from the 1980s but integrating GPS and data analytics for real-time monitoring of fuel use and driver behavior by the late 2000s.[37] The 2010s emphasized efficiency and advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS). EPA's Phase 1 greenhouse gas standards in 2011, followed by Phase 2 in 2016 for model years 2018-2027, incentivized aerodynamic fairings, low-rolling-resistance tires, and engine improvements, projecting up to 10% fuel savings for tractor-trailers through trailer skirts and side panels.[38] ADAS features like collision mitigation braking and lane departure warnings became standard on many models, with electronic logging devices (ELDs) mandated by FMCSA in 2017 to enforce hours-of-service rules via telematics, reducing fatigue-related risks.[39] These developments coincided with projections for advanced efficiency technologies, including lightweight materials and predictive cruise control, potentially yielding 20-30% gains by the 2020s in tractor-trailer combinations.[40] By the 2020s, electrification and autonomy emerged as transformative frontiers. Tesla initiated pilot deliveries of its battery-electric Semi tractor in late 2022, achieving efficiencies of 1.55 kWh per mile in tests and planning volume production at 50,000 units annually starting in 2026 from a Nevada facility.[41] Autonomous systems advanced with commercial pilots; Aurora Innovation deployed fully driverless semi-trucks on Texas public highways in 2025, accumulating over 3.3 million commercial miles with near-100% on-time deliveries in hub-to-hub routes.[42][43] EPA's Phase 3 GHG standards, finalized in 2024 for model year 2027 and later, further targeted zero-emission vocational vehicles, though infrastructure limitations and high upfront costs have slowed broad adoption of electric semis.[44] Proposals for speed limiters on heavy trucks, anticipated in 2025 by FMCSA, aim to cap speeds at 60-68 mph to enhance safety, amid ongoing debates over their impact on traffic flow.[45] Innovations like electrified trailers with integrated power and control systems also gained traction for regenerative braking and range extension.[46]Terminology and Configurations

Common Terms and Definitions