Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ugaritic alphabet

View on Wikipedia| Ugaritic | |

|---|---|

The Ugaritic writing system | |

| Script type | |

Period | c. 1400 – c. 1190 BCE |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Ugaritic, Hurrian, Akkadian |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Ugar (040), Ugaritic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Ugaritic |

| U+10380–U+1039F | |

The Ugaritic alphabet is an abjad (consonantal alphabet) with syllabic elements written using the same tools as cuneiform (i.e. pressing a wedge-shaped stylus into a clay tablet), which emerged c. 1400[1] or 1300 BCE[2] to write Ugaritic, an extinct Northwest Semitic language; it fell out of use amid the Late Bronze Age collapse c. 1190 BCE. It was discovered in Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra, Syria) in 1928. It has 30 letters. Other languages, particularly Hurrian, were occasionally written in the Ugaritic script in the area around Ugarit, but not elsewhere.

Clay tablets written in Ugaritic provide the earliest evidence of both the North Semitic and South Semitic orders of the alphabet, which gave rise to the alphabetic orders of the reduced Phoenician writing system and its descendants, including the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, Hebrew, Syriac, Greek and Latin, and of the Geʽez script, which was also influenced by the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing system,[3] and adapted for Amharic. The Arabic and Ancient South Arabian scripts are the only other Semitic alphabets which have letters for all or almost all of the 29 commonly reconstructed Proto-Semitic consonant phonemes.

The script was written from left to right. Although cuneiform was pressed into clay, its symbols were unrelated to those of Akkadian cuneiform.[4]

Function

[edit]The Ugaritic writing system was an augmented abjad. In most syllables only consonants were written, including the /w/ and /j/ of diphthongs. Ugaritic was unusual among early abjads because it also indicated vowels occurring after the glottal stop. It is thought that the letter for the syllable /ʔa/ originally represented the consonant /ʔ/, as aleph does in other Semitic abjads, and that it was later restricted to /ʔa/ with the addition, at the end of the alphabet, of /ʔi/ and /ʔu/.[5][6]

The final consonantal letter of the alphabet, s2, has a disputed origin along with both "appended" glottals, but "The patent similarity of form between the Ugaritic symbol transliterated [s2], and the s-character of the later Northwest Semitic script makes a common origin likely, but the reason for the addition of this sign to the Ugaritic alphabet is unclear (compare Segert 1983: 201–218, Dietrich and Loretz 1988). In function, [s2] is like Ugaritic s, but only in certain words – other s-words are never written with [s2]."[7]

The words that show s2 are predominantly borrowings, and thus it is often thought to be a late addition to the alphabet representing a foreign sound that could be approximated by native /s/; Huehnergard and Pardee make it the affricate /ts/.[8] Segert instead theorizes that it may have been syllabic /su/, and for this reason grouped with the other syllabic signs /ʔi/ and /ʔu/.[9]

Probably the last three letters of the alphabet were originally developed for transcribing non-Ugaritic languages (texts in the Akkadian language and Hurrian language have been found written in the Ugaritic alphabet) and were then applied to write the Ugaritic language.[4] The three letters denoting glottal stop plus vowel combinations were used as simple vowel letters when writing other languages.

The only punctuation is a word divider.[citation needed]

Origin

[edit]

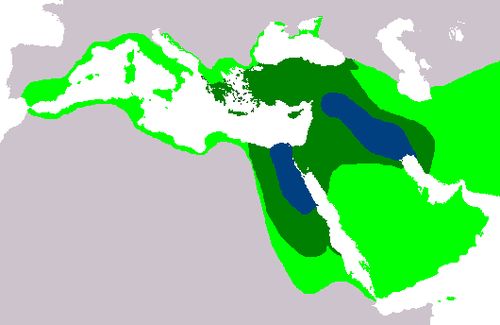

At the time the Ugaritic script was in use (c. 1300 – c. 1190 BCE),[10] Ugarit, although not a great cultural or imperial centre, was located at the geographic centre of the literate world, among Egypt, Anatolia, Cyprus, Crete, and Mesopotamia. Ugaritic combined the system of the Semitic abjad with cuneiform writing methods (pressing a stylus into clay). Scholars have searched in vain for graphic prototypes of the Ugaritic letters in Mesopotamian cuneiform.

Recently, some have suggested that Ugaritic represents some form of the Proto-Sinaitic script,[11] the letter forms distorted as an adaptation to writing on clay with a stylus. There may also have been a degree of influence from the poorly understood Byblos syllabary.[12]

It has been proposed in this regard that the two basic shapes in cuneiform, a linear wedge, as in 𐎂, and a corner wedge, as in 𐎓, may correspond to lines and circles in the linear Semitic alphabets: the three Semitic letters with circles, preserved in the Greek Θ, O and Latin Q, are all made with corner wedges in Ugaritic: 𐎉 ṭ, 𐎓 ʕ, and 𐎖 q. Other letters look similar as well: 𐎅 h resembles its assumed Greek cognate E, while 𐎆 w, 𐎔 p, and 𐎘 θ are similar to Greek Y, Π, and Σ turned on their sides.[11] Jared Diamond[13] believes the alphabet was consciously designed, citing as evidence the possibility that the letters with the fewest strokes may have been the most frequent.

Abecedaries

[edit]Lists of Ugaritic letters, abecedaria, have been found in two alphabetic orders. The "Northern Semitic order" is more similar to the one found in Phoenician, Hebrew and Arabic, the earlier, so-called ʾabjadī order, and more distantly, the Greek and Latin alphabets. The "Southern Semitic order" is more similar to the one found in the South Arabian, and the Geʽez scripts. The Ugaritic (U) letters are given in cuneiform and transliteration.

North Semitic

| Letter: | 𐎀 | 𐎁 | 𐎂 | 𐎃 | 𐎄 | 𐎅 | 𐎆 | 𐎇 | 𐎈 | 𐎉 | 𐎊 | 𐎋 | 𐎌 | 𐎍 | 𐎎 | 𐎏 | 𐎐 | 𐎑 | 𐎒 | 𐎓 | 𐎔 | 𐎕 | 𐎖 | 𐎗 | 𐎘 | 𐎙 | 𐎚 | 𐎛 | 𐎜 | 𐎝 |

| Transliteration: | ʾa | b | g | ḫ | d | h | w | z | ḥ | ṭ | y | k | š | l | m | ḏ | n | ẓ | s | ʿ | p | ṣ | q | r | ṯ | ġ | t | ʾi | ʾu | s2 |

South Semitic

| Letter: | 𐎅 | 𐎍 | 𐎈 | 𐎎 | 𐎖 | 𐎆 | 𐎌 | 𐎗 | 𐎚 | 𐎒 | 𐎋 | 𐎐 | 𐎃 | 𐎁 | 𐎔 | 𐎀 | 𐎓 | 𐎑 | 𐎂 | 𐎄 | 𐎙 | 𐎉 | 𐎇 | 𐎏 | 𐎊 | 𐎘 | 𐎕 | [ | 𐎛 | 𐎜 | 𐎝 | ] | |

| Transliteration: | h | l | ḥ | m | q | w | š | r | t | s | k | n | ḫ | b | p | ʾa | ʿ | ẓ | g | d | ġ | ṭ | z | ḏ | y | ṯ | ṣ | [ | ʾi | ʾu | s2 | ] |

Letters

[edit]

| Letter[14] | Phoneme | IPA | Corresponding letter in[15] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoenician | Ancient South Arabian | Aramaic | Arabic | ||||||||

| 𐎀 | ả (ʾa) | [ʔa] | 𐤀 | 𐩱 | 𐡀 | ا | |||||

| 𐎁 | b | [b] | 𐤁 | 𐩨 | 𐡁 | ب | |||||

| 𐎂 | g | [ɡ] | 𐤂 | 𐩴 | 𐡂 | ج | |||||

| 𐎃 | ḫ | [x] | 𐤇 | 𐩭 | 𐡇 | خ | |||||

| 𐎄 | d | [d] | 𐤃 | 𐩵 | 𐡃 | د | |||||

| 𐎅 | h | [h] | 𐤄 | 𐩠 | 𐡄 | ه | |||||

| 𐎆 | w | [w] | 𐤅 | 𐩥 | 𐡅 | و | |||||

| 𐎇 | z | [z] | 𐤆 | 𐩸 | 𐡆 | ز | |||||

| 𐎈 | ḥ | [ħ] | 𐤇 | 𐩢 | 𐡇 | ح | |||||

| 𐎉 | ṭ | [tˤ] | 𐤈 | 𐩷 | 𐡈 | ط | |||||

| 𐎊 | y | [j] | 𐤉 | 𐩺 | 𐡉 | ے/ي | |||||

| 𐎋 | k | [k] | 𐤊 | 𐩫 | 𐡊 | ڪ/ك | |||||

| 𐎌 | š | [ʃ] | 𐤔 | 𐩦 | 𐡔 | ش | |||||

| 𐎍 | l | [l] | 𐤋 | 𐩡 | 𐡋 | ل | |||||

| 𐎎 | m | [m] | 𐤌 | 𐩣 | 𐡌 | م | |||||

| 𐎏 | ḏ | [ð] | 𐤆 | 𐩹 | 𐡃 | ذ | |||||

| 𐎐 | n | [n] | 𐤍 | 𐩬 | 𐡍 | ن | |||||

| 𐎑 | ẓ | [θˤ] | 𐤎 | 𐩼 | 𐡈 | ظ | |||||

| 𐎒 | s | [s] | 𐤎 | 𐩪 | 𐡎 | س | |||||

| 𐎓 | ʿ | [ʕ] | 𐤏 | 𐩲 | 𐡏 | ع | |||||

| 𐎔 | p | [p] | 𐤐 | 𐩰 | 𐡐 | ف | |||||

| 𐎕 | ṣ | [sˤ] | 𐤑 | 𐩮 | 𐡑 | ص | |||||

| 𐎖 | q | [q] | 𐤒 | 𐩤 | 𐡒 | ق | |||||

| 𐎗 | r | [r] | 𐤓 | 𐩧 | 𐡓 | ر | |||||

| 𐎘 | ṯ | [θ] | 𐤔 | 𐩻 | 𐤕 | ث | |||||

| 𐎙 | ġ | [ɣ] | 𐤏 | 𐩶 | 𐡏 | غ | |||||

| 𐎚 | t | [t] | 𐤕 | 𐩩 | 𐡕 | ت | |||||

| 𐎛 | ỉ (ʾi) | [ʔi] | 𐤉 | 𐩺 | 𐡉 | إ | |||||

| 𐎜 | ủ (ʾu) | [ʔu] | 𐤅 | 𐩥 | 𐡅 | ؤ | |||||

| 𐎝 | s₂ | [su] | |||||||||

| 𐎟 | word divider | 𐤟 | |||||||||

Ugaritic short alphabet

[edit]Two shorter variants of the Ugaritic alphabet existed with findspots primarily not in the area of Ugarit. Findspots have included Tel Beit Shemesh, Sarepta, and Tiryns. It is generally found on inscribed objects vs the tablets of the standard Ugaritic alphabet and unlike the standard version it is usually written right to left.[16] One variant contained 27 letters and the other 22 letters. It is not known what the relative chronology of the different Ugaritic alphabets was.[17][18][19]

Unicode

[edit]Ugaritic script was added to the Unicode Standard in April, 2003 with the release of version 4.0.

The Unicode block for Ugaritic is U+10380–U+1039F:

| Ugaritic[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1038x | 𐎀 | 𐎁 | 𐎂 | 𐎃 | 𐎄 | 𐎅 | 𐎆 | 𐎇 | 𐎈 | 𐎉 | 𐎊 | 𐎋 | 𐎌 | 𐎍 | 𐎎 | 𐎏 |

| U+1039x | 𐎐 | 𐎑 | 𐎒 | 𐎓 | 𐎔 | 𐎕 | 𐎖 | 𐎗 | 𐎘 | 𐎙 | 𐎚 | 𐎛 | 𐎜 | 𐎝 | 𐎟 | |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Six letters for transliteration were added to the Latin Extended-D block in March 2019 with the release of Unicode 12.0:[20]

- U+A7BA Ꞻ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER GLOTTAL A

- U+A7BB ꞻ LATIN SMALL LETTER GLOTTAL A

- U+A7BC Ꞽ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER GLOTTAL I

- U+A7BD ꞽ LATIN SMALL LETTER GLOTTAL I

- U+A7BE Ꞿ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER GLOTTAL U

- U+A7BF ꞿ LATIN SMALL LETTER GLOTTAL U

See also

[edit]- Old Persian cuneiform – a much later, unrelated attempt at a cuneiform semi-alphabet.

References

[edit]- ^ William M. Schniedewind, A Primer on Ugaritic, p. 32

- ^ Ugaritic, in The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia

- ^ Ullendorf, Edward (July 1951). "Studies in the Ethiopic Syllabary". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 21 (3). Cambridge University Press: 207–217. doi:10.2307/1156593. JSTOR 1156593.

- ^ a b Healey, John F. (1990). "The Early Alphabet". Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet. University of California Press. p. 216. ISBN 0-520-07431-9.

- ^ Coulmas, Florian (1991). The writing systems of the world. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-18028-9.

- ^ Schniedewind, William; Hunt, Joel (2007). A primer on Ugaritic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46698-1.

- ^ Ugaritic, in The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia

- ^ Huehnergard, An Introduction to Ugaritic (2012), p. 21; Pardee, Ugaritic alphabetic cuneiform in the context of other alphabetic systems in Studies in ancient Oriental civilization (2007), p. 183.

- ^ Stanislave Segert, "The Last Sign of the Ugaritic Alphabet" in Ugaritic-Forschugen 15 (1983): 201–218

- ^ Ugaritic, in The Ancient-Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia

- ^ a b Brian Colless, Cuneiform alphabet and picto-proto-alphabet

- ^ A Basic Grammar of the Ugaritic Language: With Selected Texts and Glossary, p. 19 by Stanislav Segert, 1985.

- ^ Writing Right | Senses | DISCOVER Magazine

- ^ Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). "Epigraphic Semitic Scripts". The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- ^ Kogan, Leonid (2011). "Tab. 6.2: Regular correspondences of the Proto-Semitic consonants". In Weninger, Stefan (ed.). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

- ^ [1]Fossé, Cécile, et al., "Archaeo-Material Study of the Cuneiform Tablet from Tel Beth-Shemesh", Tel Aviv 51.1, pp. 3-17, 2024

- ^ [2]Ferrara, Silvia, "A ‘top-down’ re-invention of an old form: Cuneiform alphabets in context", Understanding Relations Between Scripts II, pp. 15-51, 2020

- ^ Bordreuil, P., "Cunéiformes alphabétiques non canoniques", I. La tablette alphabétique sénestroverse RS 22.03’, Syria 58 (3–4), pp. 301–311, 1981

- ^ Dietrich, M. and Loretz, O., "Die Keilalphabete. Die phönizisch kanaanäischen und altarabischen Alphabete in Ugarit", Münster, 1988

- ^ Suignard, Michel (2017-05-09). "L2/17-076R2: Revised proposal for the encoding of an Egyptological YOD and Ugaritic characters" (PDF).

External links

[edit]- Download a Ugaritic font (includes Unicode font)

- Ugaritic cuneiform characters from the Unicode Ugaritic cuneiform script

- Ugaritic cuneiform Omniglot entry on the subject

- Ugaritic script (ancientscripts.com)

- Ugaritic writing

- GNU FreeFont Unicode font family with Ugaritic range in its sans-serif face.

Ugaritic alphabet

View on GrokipediaOverview

Description

The Ugaritic alphabet is a cuneiform-based abjad, or consonantal alphabet, consisting of 30 signs that primarily represent consonants, with occasional use of certain signs as mater lectionis to indicate vowels.[5][6] This script was developed specifically for writing the Ugaritic language, an extinct Northwest Semitic tongue closely related to other ancient Levantine languages such as Hebrew and Phoenician.[7] The script was inscribed on clay tablets using a stylus to produce wedge-shaped impressions, a technique adapted from broader Mesopotamian cuneiform traditions.[8] Tablets varied in size, from small ones measuring about 3 by 4 centimeters to larger examples up to 30 by 20 centimeters, and were typically fired or sun-dried for durability, rendering them resistant to decay and allowing many to survive millennia.[8][9] Ugaritic texts were composed and used mainly from the 14th to the 12th century BCE in the ancient city of Ugarit, located at modern Ras Shamra in Syria.[9][10]Historical Significance

The Ugaritic alphabet represents the earliest known full alphabetic abecedary, dating to the 14th-13th centuries BCE, which has provided crucial evidence for the evolution of alphabetic scripts from proto-alphabetic forms to the modern systems used today.[11] These abecedaries, inscribed on clay tablets in cuneiform style, confirm the antiquity of the Proto-Canaanite sign names and their sequential order, bridging earlier linear traditions with later Phoenician developments.[12] Their discovery underscores the alphabet's role in advancing literacy in the ancient Near East by simplifying writing for Semitic languages, distinct from the more complex syllabic cuneiform systems.[13] The script's primary historical value lies in preserving Ugaritic literature, including major epics such as the Baal Cycle and the Kirta epic, which offer direct parallels to Canaanite and biblical narratives.[14] The Baal Cycle, detailing the storm god Baal's conflicts and kingship, mirrors motifs of divine battles and cosmic order found in Hebrew Bible texts like Psalms and Job, illuminating shared mythological frameworks.[15] Similarly, the Kirta epic's themes of royal succession and divine intervention resonate with stories in Genesis and 1-2 Samuel, revealing common literary structures and poetic devices in Northwest Semitic traditions.[14] In Ugarit, a cosmopolitan port city, the alphabet facilitated multilingualism by serving alongside Akkadian cuneiform for diplomatic and administrative purposes, while Hurrian appeared in ritual texts, reflecting the society's diverse linguistic interactions.[16] This coexistence— with over 1,400 Ugaritic texts amid Akkadian and Hurrian documents—highlights the script's adaptability in a hub of international trade and cultural exchange during the Late Bronze Age.[17] Such evidence demonstrates how the Ugaritic alphabet supported local identity amid imperial influences from Hittite and Egyptian powers.[18] The Ugaritic corpus has profoundly shaped biblical studies by revealing linguistic and mythological affinities between Ugaritic and Hebrew, such as shared vocabulary for divine titles and ritual practices.[15] These parallels, particularly in the Baal Cycle's depiction of deities and the Kirta epic's familial motifs, have informed interpretations of Hebrew Bible narratives, clarifying Canaanite influences on Israelite religion and literature.[14] Overall, the alphabet's texts have revolutionized scholarly understanding of Semitic cultural continuity in the ancient Levant.History and Discovery

Archaeological Context

The ancient city of Ugarit, identified with the archaeological site of Tell Ras Shamra on the Mediterranean coast of modern-day Syria near Latakia, was first systematically excavated starting in 1929 by the French Archaeological Mission under the direction of Claude F.A. Schaeffer.[19] These excavations, initiated after a chance discovery of a tomb by a local farmer, uncovered the remains of a major Late Bronze Age port city that thrived as a commercial and cultural hub from approximately 1400 BCE to 1200 BCE. Among the most significant finds were over 1,500 clay tablets inscribed in the Ugaritic cuneiform alphabet, unearthed primarily from the royal palace archives, temple complexes (including the house of the high priest), and private dwellings throughout the city. These tablets, dating to the city's final centuries, encompass administrative, literary, and ritual texts that reflect Ugarit's role in international trade and diplomacy.[18] The preservation of these artifacts resulted from Ugarit's abrupt destruction around 1185 BCE, attributed to an invasion by the Sea Peoples—a confederation of maritime raiders—whose assault led to widespread fires and the collapse of structures, inadvertently baking the unfired clay tablets in the debris.[20] This cataclysmic event ended Ugarit's occupation, leaving the site abandoned until modern times. Excavations also revealed a range of associated artifacts, including cylinder seals used for administrative purposes, imported and local pottery indicative of trade networks, and bilingual inscriptions pairing Ugaritic with Akkadian, Hittite, or Egyptian, highlighting the city's multicultural interactions.Decipherment Process

The decipherment of the Ugaritic alphabet began shortly after the discovery of cuneiform tablets at Ras Shamra in 1929, with initial recognition of its alphabetic nature occurring in the early 1930s through the analysis of abecedaries by scholars such as Charles Virolleaud, Édouard Dhorme, and Hans Bauer. These abecedaries, which listed signs in a sequential order resembling known Semitic alphabets, provided crucial evidence that the script was not syllabic like standard Akkadian cuneiform but rather an alphabetic system of 27 consonants and three vowel indicators. Dhorme, working independently, proposed phonetic values for many signs by comparing them to Phoenician and other West Semitic scripts, achieving about 24 correct assignments by late 1930 based solely on the initial texts.[21] Further confirmation came from bilingual Ugaritic-Akkadian vocabulary lists unearthed at Ugarit, which matched Ugaritic terms to their Akkadian equivalents in lexical contexts. These bilinguals, often appearing as glosses or parallel entries in administrative and scholarly tablets, confirmed many of the provisional readings from the abecedaries and revealed the script's adaptation of cuneiform wedges for an alphabetic purpose. The lists facilitated the identification of word roots and grammatical forms, bridging gaps in the comparative method.[22] By the early 1930s, the alphabet was fully deciphered. Significant contributions to understanding Ugaritic grammar and vocabulary came from Cyrus H. Gordon, whose 1940 publication, Ugaritic Grammar, synthesized these efforts and established a foundational framework for reading the script.[23] Gordon's work emphasized morphological patterns shared with other Semitic languages, enabling the translation of literary and ritual texts. The process overcame major challenges, including the absence of direct descendant languages or contemporary bilingual inscriptions like the Rosetta Stone, relying instead on comparative philology with Hebrew, Phoenician, and Arabic cognates to infer meanings and syntax. This method, combined with the internal consistency of Ugaritic texts such as myths and letters, validated the decipherment despite initial uncertainties in sign order and vocalization. For instance, abecedaries like the one inscribed on a small tablet helped confirm the aleph-to-taw sequence familiar from later alphabets.[21]Origins and Development

Cultural and Linguistic Background

Ugarit, located on the northern Syrian coast, served as a major cosmopolitan port city during the Late Bronze Age (c. 1450–1200 BCE), facilitating extensive trade networks with Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia (Hittite territories). This strategic position at the crossroads of major cultural spheres enabled the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies, contributing to an environment ripe for linguistic and scribal innovations, including the development of the Ugaritic alphabet as a local writing system alongside established scripts like Akkadian cuneiform. Linguistically, Ugaritic belongs to the Northwest Semitic branch of the Semitic language family, classified as a distinct language closely related to the Canaanite subgroup, which includes Hebrew and Phoenician. It retains archaic features such as a fully preserved dual number in nouns, verbs, and pronouns, alongside a case system with three cases (nominative, accusative, genitive) in the singular and two (nominative, oblique) in the dual and plural, marking it as more conservative than later Canaanite languages where these elements largely eroded.[24] In sociolinguistic terms, Ugaritic was predominantly employed in written form for elite purposes, including religious literature (such as myths and rituals), administrative records (like economic lists and legal documents), and diplomatic correspondence, reflecting its role in institutional and high-status activities within the palace, temples, and elite residences. While no direct evidence survives for everyday oral communication, the language likely functioned as a vernacular spoken by the local population, with writing confined to a literate minority amid a multilingual society where Akkadian served international needs. Ugaritic texts exhibit notable influences from neighboring languages, incorporating Akkadian lexical borrowings, particularly in administrative and technical terminology (e.g., terms for trade and governance), due to Mesopotamia's dominant cultural and economic role. Additionally, Hurrian personal names appear frequently in Ugaritic onomastics and documents, indicating significant Hurrian demographic presence and cultural integration, especially in ritual and elite contexts.[25]Theories of Invention

The primary scholarly consensus holds that the Ugaritic alphabet developed as an adaptation of the earlier Proto-Sinaitic script, which emerged around 1850–1500 BCE among Semitic-speaking Canaanite workers laboring in Egyptian turquoise mines at Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula. These workers are believed to have selectively borrowed and simplified Egyptian hieroglyphic and hieratic signs, applying the acrophonic principle—where a sign's phonetic value derives from the initial consonant of a familiar Semitic word for the depicted object—to create a concise consonantal system of about 22–30 signs, far less complex than the syllabic cuneiform of Mesopotamia or the logographic Egyptian systems. In Ugarit, this linear alphabetic precursor was then reformatted into a cuneiform medium using wedge-shaped impressions on clay tablets, likely to leverage existing scribal infrastructure while expressing the local Northwest Semitic vernacular, with the earliest attested examples dating to the 14th century BCE.[26][11] This adaptation theory is supported by morphological parallels between Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions and Ugaritic signs, such as the 'alep sign representing an ox head (ʾalp in Semitic languages) for the glottal stop /ʔ/, and the absence of syllabic elements that characterize Akkadian or Hittite cuneiform, emphasizing instead a purely consonantal inventory suited to Semitic phonology. The process reflects a pragmatic innovation at cultural crossroads, where Egyptian oversight of mining operations exposed illiterate or semi-literate Semitic laborers to hieroglyphic models, prompting them to devise a script for practical communication like worker tallies or dedications, as argued in Orly Goldwasser's analysis of the inventors as non-elite miners lacking formal scribal training. Recent work underscores the social dimensions of this invention, portraying it as a collaborative "disruptive technology" born from intercultural exchanges in the Late Bronze Age Levant, rather than a solitary elite endeavor, with Ugarit's polyglot environment—blending Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and local influences—facilitating the script's localization around 1400 BCE.[27][28][29] Alternative hypotheses propose either a more direct derivation from Egyptian hieratic cursive script, bypassing Proto-Sinaitic intermediaries, or an independent invention within Ugarit itself as a simplification of local cuneiform traditions. Proponents of the hieratic origin, such as Carleton T. Hodge, point to specific sign resemblances—like the Ugaritic bēt (house) echoing hieratic forms—and argue that Ugaritic scribes, familiar with Egyptian administrative texts, directly mimicked these for efficiency in a multicultural port city. Independent invention theories, though less dominant, suggest Ugarit innovated the alphabet de novo around the 15th century BCE to assert cultural autonomy amid imperial pressures from Egypt and Hatti, drawing on but not deriving from external models. These views remain minority positions, challenged by the acrophonic consistencies linking Ugaritic to earlier Sinai evidence.[30][31] Ongoing debates center on the precise timeline and agency of invention, with traditional views placing Proto-Sinaitic origins in the 19th century BCE (ca. 1900–1700) based on paleographic and stratigraphic dating of Serabit inscriptions, while revisionist paleographers like Goldwasser advocate a narrower 19th-century window (ca. 1840 BCE) tied to specific pharaonic expeditions under Amenemhat III. In contrast, some scholars extend the emergence to the 15th century BCE, aligning it closer to Ugaritic attestations and attributing greater continuity to Canaanite scribal networks rather than isolated mining innovations. The role of illiterate or sub-elite innovators persists as a contentious point, with 2010s studies emphasizing how non-literate Semitic workers at cultural interfaces could conceptualize phonetic abstraction without prior writing systems, though critics argue this underestimates scribal mediation in script transmission. These discussions highlight the alphabet's invention as a dynamic, socially embedded process rather than a singular event. Recent archaeological findings, such as possible alphabetic inscriptions on clay cylinders from Umm el-Marra in northern Syria dated to circa 2400 BCE (announced in November 2024), suggest alphabetic writing may have emerged even earlier in the region, potentially by 500 years predating Proto-Sinaitic examples, though the interpretation remains tentative and subject to further analysis.[32][33][34][35]Script Characteristics

Functional Type

The Ugaritic alphabet functions as an abjad, a type of writing system that primarily represents consonants, with 30 signs dedicated to consonantal phonemes.[5] Three of these signs—the aleph variants (ʾa, ʾi, ʾu)—also serve as matres lectionis, indicating the vowels /a/, /i/, /u/ (short or long), to provide limited vocalic guidance in specific contexts like word-initial glottal stops or to specify vowel quality. This partial vowel notation distinguishes the Ugaritic script from pure consonantaries while keeping the system compact and suited to the language's structure. The script's phonemic coverage encompasses the core consonantal inventory of Ugaritic, a Northwest Semitic language, including distinctive features like emphatic (pharyngealized) consonants ṭ, ṣ, and q; guttural (pharyngeal and glottal) sounds such as ḥ and ʿ; and a rich set of sibilants comprising /s/, /z/, /š/, and /ṣ/.[5] It does not encode tones, diphthongs, or a complex vowel inventory, aligning with Ugaritic's phonology of three basic vowel qualities (/a/, /i/, /u/) in short and long forms, which are largely predictable from morphological patterns.[5] Compared to syllabic systems like Akkadian cuneiform, which requires separate signs for consonant-vowel combinations, the Ugaritic abjad enables more streamlined notation, particularly advantageous for Semitic root-based morphology where consonantal skeletons determine lexical meaning.[18] This efficiency likely contributed to its adoption for vernacular literary and administrative texts alongside the more cumbersome syllabary used for Akkadian.[18] A key limitation of the abjad format is the omission of short vowels and inconsistent use of matres lectionis, resulting in potential ambiguities in pronunciation and word division that must be inferred from grammatical context, poetic parallelism, or cross-references with cognate Semitic languages like Hebrew and Phoenician.[36]Writing Conventions

The Ugaritic alphabet was inscribed primarily on clay tablets using a reed stylus, which produced horizontal wedges to form the cuneiform-like signs, distinguishing it from the more vertical or complex wedge arrangements typical of contemporary logosyllabic cuneiform scripts used for Akkadian and other languages.[37] This horizontal orientation allowed for efficient linear writing and reflected an adaptation aimed at compatibility with local administrative and literary practices while maintaining the material familiarity of cuneiform.[38] Styli were typically made from reed, though variants in wood, bone, ivory, or metal have been attested, enabling scribes to create the 30-sign alphabet with relative speed on purpose-made tablets or incidental surfaces like pottery and stone.[37] Texts were written in left-to-right horizontal lines, a convention adopted from Middle Babylonian syllabic cuneiform practices prevalent in the Late Bronze Age Levant.[38] This left-to-right progression contrasted with the right-to-left norm of some linear alphabetic precursors, emphasizing the script's cuneiform heritage while facilitating its abjad function for consonantal representation.[37] Formatting relied on word dividers rather than punctuation, with no evidence of systematic sentence-ending marks or other diacritics.[37] Common dividers included a small vertical wedge (𐎟), a short vertical stroke, or a vertical line (⟨ω⟩), used inconsistently to separate prosodic or morphosyntactic units, such as prefix particles from following morphemes in administrative and literary texts.[39] Dots appeared rarely, often in vertical arrangements of three, as an alternative separator in some inscriptions.[40] Polyphony was rare, with most signs representing single consonants, though certain graphemes exhibited limited multiple phonetic values, complicating precise phonemic transcription in specific dialectal contexts.[41] Tablets were often oriented in portrait format, with text flipped bottom-to-top when read, and lines sometimes overrun onto edges without additional formatting cues.[37]Corpus and Examples

Abecedaries

Abecedaries in the Ugaritic script are instructional texts consisting of sequential lists of the alphabet's signs, primarily used to teach aspiring scribes the fixed order and forms of the letters. These practice exercises were typically inscribed on small clay tablets, fragments, or occasionally along the edges of larger documents, reflecting their role in elementary scribal education during the Late Bronze Age at Ugarit. The purpose was pedagogical, facilitating the memorization of the 30-sign consonantal alphabet and its arrangement, which was essential for literacy in administrative, literary, and ritual contexts. Such texts demonstrate the structured nature of scribal training, where novices progressed from basic letter sequences to more complex compositions. Over twenty abecedaries have been unearthed at Ugarit, varying in completeness and sometimes showing minor deviations in sign placement or omissions due to the fragmentary state of the tablets. Notable examples include KTU 5.6 (RS 12.063), an early complete sequence discovered in a domestic context, and KTU 5.21 (RS 24.288), a well-preserved tablet containing all 30 signs inscribed in a single column, found in a temple cella and dated to the 13th century BCE. Other significant specimens, such as KTU 5.4, 5.12, and 5.27, exhibit partial lists or repetitions, likely representing student exercises with errors or intentional variations for practice. These artifacts, cataloged in the standard edition Die keilalphabetischen Texte aus Ugarit (KTU), highlight the prevalence of such training materials across residential, administrative, and religious sites in the city.[42] The standard order preserved in these abecedaries follows the Proto-Canaanite sequence: ʾ b g ḫ d h w z ḥ ṭ y k š m ḏ n z s ʿ p ṣ q r ġ t ʾ i u, with occasional insertions or adjustments for additional sibilants and semi-vowels. This arrangement, consistent across most examples like RS 24.288, begins with glottal and labial sounds, progresses through velars and dentals, and ends with a secondary group of sibilants and gutturals, differing from the later Phoenician order by including extra signs for Ugaritic phonology. Variations appear in about half the abecedaries, such as reversed pairs (e.g., š and l swapped) or incomplete sections, possibly indicating regional or individual scribal preferences during training. The sequence's stability underscores its role as a foundational mnemonic device.[11] These abecedaries provide the earliest attested evidence of a fixed alphabetic order in the Semitic world, dating to circa 1400–1200 BCE, and confirm the Ugaritic script's direct lineage from Proto-Canaanite precursors while influencing subsequent systems like Phoenician and Hebrew. Their discovery aided the decipherment of the script by revealing the letter inventory and sequence independently of bilingual texts. As tools for scribal training, they illustrate Ugarit's advanced educational infrastructure, where literacy was disseminated beyond elite circles to support the city's multilingual bureaucracy.[11]Major Inscriptions

The major inscriptions in the Ugaritic script encompass a diverse corpus of literary, administrative, religious, and bilingual texts discovered primarily at Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit), dating to the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1400–1200 BCE). These texts, part of an overall corpus of approximately 1,500–2,000 Ugaritic texts and fragments, demonstrate the script's versatility in recording complex narratives and practical documents on clay tablets, often in poetic or formulaic styles that reflect oral traditions adapted to writing.[43] Among the most prominent literary works are epic poems exploring themes of divinity, kingship, and human-divine relations. The Baal Cycle (KTU 1.1–1.6), the longest surviving Ugaritic narrative, depicts the storm god Baal's ascent to divine kingship through conflicts with sea chaos (Yamm) and death (Mot), culminating in the construction of his palace on Mount Saphon, symbolizing fertility and cosmic order. This epic, preserved on multiple tablets likely copied by the scribe Ilimalku, underscores Baal's role as a warrior-king and patron deity, with vivid descriptions of divine assemblies, battles, and rituals that parallel broader Canaanite mythology. The Legend of Kirta (KTU 1.14–1.16), a royal saga, follows King Kirta's divinely ordained quest—guided by El in a dream—to besiege Udum and marry Princess Ḥuraya for heirs, emphasizing kingship's dependence on lineage, divine favor, and familial duty amid personal loss and rebellion. Similarly, the Tale of Aqhat (KTU 1.17–1.19) narrates the righteous judge Danel's plea to El for a son, Aqhat, whose life is threatened by the warrior goddess Anat over a bow; the story culminates in Aqhat's murder, prolonged mourning, and themes of vengeance, mortality, and the interplay between divine caprice and human piety, evoking patriarchal ideals of justice and fertility. These epics, inscribed in the alphabetic cuneiform, highlight the script's capacity for rhythmic parallelism and epic scope, serving both mythological and ideological functions tied to Ugaritic royalty and theology.[43][44] Administrative inscriptions reveal the script's practical applications in governance and diplomacy. Economic records, such as lists of commodities, personnel, and transactions, document Ugarit's bustling trade and resource management, often in terse, formulaic entries that attest to the city's role as a Mediterranean hub. Diplomatic letters detail alliances, tribute, and military matters among regional powers, showcasing the script's use in international relations during the 14th–13th centuries BCE; known exchanges with Egypt, however, were conducted in Akkadian cuneiform. Temple ritual lists enumerate offerings, sacrifices, and personnel duties, providing glimpses into institutional organization and daily cultic practices. These texts, typically brief and utilitarian, illustrate the alphabet's efficiency for non-literary purposes beyond elite mythology.[45] Religious inscriptions further illuminate Ugarit's polytheistic worldview, with prominent Hurrian influences evident in hymns and incantations. Hymns praise deities like Tešub (syncretized with Baal) and Nikkal, blending Hurrian poetic forms with Ugaritic elements to invoke protection and prosperity, often in syllabic or alphabetic cuneiform from priestly houses. Incantations against misfortune, such as those for healing or averting evil, incorporate ritual formulas addressing the pantheon headed by El as creator-father and Baal as storm warrior, reflecting a hierarchical divine family that governed natural and social orders. These texts, numbering around 50 Hurrian-influenced examples, highlight cultural fusion under Hittite oversight and the script's role in esoteric cultic transmission.[46] Bilingual inscriptions, particularly Ugaritic-Hurrian and Ugaritic-Akkadian parallels, have been crucial for decipherment and translation. Ritual texts like KTU 1.116 alternate Ugaritic instructions with Hurrian deity lists or recitations, using codeswitching without deep grammatical fusion to clarify sacrificial procedures and divine invocations. Akkadian-influenced documents, such as lexical lists or administrative notes, provide Semitic parallels that aid in reconstructing vocabulary and syntax, as seen in quadrilingual glosses equating terms across languages. These hybrids, from the 14th–12th centuries BCE, facilitated cross-cultural administration and scholarship by offering direct linguistic bridges.The Alphabet

Standard Letters

The standard Ugaritic alphabet consists of 30 signs, known as the "long alphabet," which represent the phonemes of the Ugaritic language, an extinct Northwest Semitic tongue spoken in the ancient city of Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra, Syria) during the Late Bronze Age (c. 1400–1200 BCE). These signs were impressed into clay tablets using a stylus to form wedge-shaped impressions, adapting the cuneiform technique prevalent in Mesopotamia but simplifying it into an abjad system where each sign denotes a single consonant (with three additional signs for glottal stops distinguished by implied vowels). The alphabet is written from left to right, contrasting with the right-to-left direction of many later Semitic scripts.[5] The shapes of the Ugaritic signs are composed primarily of straight wedges oriented horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, along with angled "Winkelhaken" wedges, mirroring the basic elements of Mesopotamian cuneiform but featuring fewer and simpler combinations—typically 1 to 7 wedges per sign—to suit alphabetic use rather than the complex syllabary of Akkadian. This adaptation is evident in the predominance of horizontal wedges in many signs, which often display minimal inclination and provide a visual distinction from the more vertically oriented or intricate Akkadian forms, emphasizing clarity for rapid inscription on clay. Some signs exhibit polyvalent tendencies, such as occasional interchange between similar sibilants like š (/ʃ/) and s (/s/ or affricate [ts]), reflecting phonetic nuances in the language, though most signs maintain distinct values.[5] The following table inventories the 30 standard signs in their conventional abecedary order, including Unicode representations, Latin transliterations, approximate phonetic values (using IPA where precise), and traditional Semitic acrophonic names derived from Northwest Semitic words (e.g., objects or animals beginning with the sound). These names, such as alpu for "ox," underscore the script's acrophonic principle, akin to early Semitic alphabets. Visual examples use Unicode glyphs, which approximate ancient impressions; actual tablets show variations in wedge depth and alignment due to stylus pressure.| Order | Unicode | Glyph | Transliteration | Phonetic Value | Semitic Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | U+10380 | 𐎀 | ʾ | /ʔ/ (glottal stop) | alpu (ox) |

| 2 | U+10381 | 𐎁 | b | /b/ | baytu (house) |

| 3 | U+10382 | 𐎂 | g | /g/ | gamlu (camel) |

| 4 | U+10383 | 𐎃 | ḫ | /χ/ (velar fricative) | ḫatpu (sickle) |

| 5 | U+10384 | 𐎄 | d | /d/ | diggu (grain) |

| 6 | U+10385 | 𐎅 | h | /h/ | ḥillu (cheer) |

| 7 | U+10386 | 𐎆 | w | /w/ | wa(y)du (hook) |

| 8 | U+10387 | 𐎇 | z | /z/ | zīnu (weapon) |

| 9 | U+10388 | 𐎈 | ḥ | /ħ/ (pharyngeal fricative) | ḥaṣ(a)bu (court) |

| 10 | U+10389 | 𐎉 | ṭ | /tˤ/ (emphatic stop) | ṭēltu (woman) |

| 11 | U+1038A | 𐎊 | y | /j/ | yadu (hand) |

| 12 | U+1038B | 𐎋 | k | /k/ | kapu (palm) |

| 13 | U+1038C | 𐎌 | š | /ʃ/ | šinnu (tooth) |

| 14 | U+1038D | 𐎍 | l | /l/ | lamdu (goad) |

| 15 | U+1038E | 𐎎 | m | /m/ | maynu (water) |

| 16 | U+1038F | 𐎏 | ḏ | /ð/ | ḏaḫaru (path) |

| 17 | U+10390 | 𐎐 | n | /n/ | naḫašu (serpent) |

| 18 | U+10391 | 𐎑 | ẓ | /θˤ/ or /sˤ/ (emphatic fricative) | ẓillu (shadow) |

| 19 | U+10392 | 𐎒 | s | /s/ or /ts/ | šawu (bow) |

| 20 | U+10393 | 𐎓 | ʿ | /ʕ/ (pharyngeal fricative) | ʿaynu (eye) |

| 21 | U+10394 | 𐎔 | p | /p/ | pū (mouth) |

| 22 | U+10395 | 𐎕 | ṣ | /sˤ/ (emphatic fricative) | ṣēdu (side) |

| 23 | U+10396 | 𐎖 | q | /q/ | qarnu (horn) |

| 24 | U+10397 | 𐎗 | r | /r/ | rašpu (flame) |

| 25 | U+10398 | 𐎘 | ṯ | /θ/ | ṯalāʾu (lamb) |

| 26 | U+10399 | 𐎙 | ġ | /ɣ/ (velar fricative) | ġašmu (load) |

| 27 | U+1039A | 𐎚 | t | /t/ | tawu (mark) |

| 28 | U+1039B | 𐎛 | i | /ʔi/ (glottal + i-vowel) | ʾiddu (hand, variant) |

| 29 | U+1039C | 𐎜 | u | /ʔu/ (glottal + u-vowel) | ʾummu (mother, variant) |

| 30 | U+1039D | 𐎝 | ss or s̀ | /s/ (variant sibilant) | sillu (basket, allograph) |