Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Urban planning

View on Wikipedia

Urban planning (also called city planning or town planning in some contexts) is the process of developing and designing land use and the built environment, including air, water, and the infrastructure passing into and out of urban areas, such as transportation, communications, and distribution networks, and their accessibility.[1] Traditionally, urban planning followed a top-down approach in master planning the physical layout of human settlements.[2] The primary concern was the public welfare,[1][2] which included considerations of efficiency, sanitation, protection and use of the environment,[1] as well as taking account of effects of the master plans on the social and economic activities.[3] Over time, urban planning has adopted a focus on the social and environmental "bottom lines" that focuses on using planning as a tool to improve the health and well-being of people and maintain sustainability standards. In the early 21st century, urban planning experts such as Jane Jacobs called on urban planners to take resident experiences and needs more into consideration.

Urban planning answers questions about how people will live, work, and play in a given area and thus, guides orderly development in urban, suburban and rural areas.[4] Although predominantly concerned with the planning of settlements and communities, urban planners are also responsible for planning the efficient transportation of goods, resources, people, and waste; the distribution of basic necessities such as water and electricity; a sense of inclusion and opportunity for people of all kinds, culture and needs; economic growth or business development; improving health and conserving areas of natural environmental significance that actively contributes to reduction in CO2 emissions[5] as well as protecting heritage structures and built environments. Since most urban planning teams consist of highly educated individuals that work for city governments,[6] recent debates focus on how to involve more community members in city planning processes.

Urban planning is an interdisciplinary field that includes civil engineering, architecture, human geography, social science and design sciences. Practitioners of urban planning use research and analysis, strategic thinking, engineering architecture, urban design, public consultation, policy recommendations, implementation and management.[2] It is closely related to the field of urban design and some urban planners provide designs for streets, parks, buildings and other urban areas.[7] Urban planners work with the cognate fields of civil engineering, landscape architecture, architecture, and public administration to achieve strategic, policy and sustainability goals. Early urban planners were often members of these cognate fields though in the 21st century, urban planning is a separate, independent professional discipline. The discipline of urban planning is the broader category that includes different sub-fields such as land-use planning, zoning, economic development, environmental planning, and transportation planning.[8] Creating the plans requires a thorough understanding of penal codes and zonal codes of planning.

Another important aspect of urban planning is that the range of urban planning projects include the large-scale master planning of empty sites or Greenfield projects as well as small-scale interventions and refurbishments of existing structures, buildings and public spaces. Pierre Charles L'Enfant in Washington, D.C., Daniel Burnham in Chicago, Lúcio Costa in Brasília and Georges-Eugene Haussmann in Paris planned cities from scratch, and Robert Moses and Le Corbusier refurbished and transformed cities and neighborhoods to meet their ideas of urban planning.[9]

Terminology

[edit]It is also known as town planning, city planning, regional planning, or rural planning in specific contexts.

History

[edit]

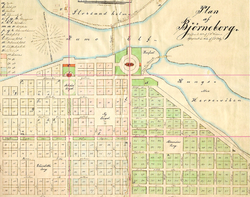

There is evidence of urban planning and designed communities dating back to the Mesopotamian, Indus Valley, Minoan, and Egyptian civilizations in the third millennium BCE. Archaeologists studying the ruins of cities in these areas find paved streets that were laid out at right angles in a grid pattern.[11] The idea of a planned out urban area evolved as different civilizations adopted it. Beginning in the 8th century BCE, Greek city states primarily used orthogonal (or grid-like) plans.[12] Hippodamus of Miletus (498–408 BC), the ancient Greek architect and urban planner, is considered to be "the father of European urban planning", and the namesake of the "Hippodamian plan" (grid plan) of city layout.[13]

The ancient Romans also used orthogonal plans for their cities. City planning in the Roman world was developed for military defense and public convenience. The spread of the Roman Empire subsequently spread the ideas of urban planning. As the Roman Empire declined, these ideas slowly disappeared. However, many cities in Europe still held onto the planned Roman city center. Cities in Europe from the 9th to 14th centuries, often grew organically and sometimes chaotically. But in the following centuries with the coming of the Renaissance many new cities were enlarged with newly planned extensions.[14] From the 15th century on, much more is recorded of urban design and the people that were involved. In this period, theoretical treatises on architecture and urban planning start to appear in which theoretical questions around planning the main lines, ensuring plans meet the needs of the given population and so forth are addressed and designs of towns and cities are described and depicted. During the Enlightenment period, several European rulers ambitiously attempted to redesign capital cities. During the Second French Empire, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, under the direction of Napoleon III, redesigned the city of Paris into a more modern capital, with long, straight, wide boulevards.[15]

Planning and architecture went through a paradigm shift at the turn of the 20th century. The industrialized cities of the 19th century grew at a tremendous rate. The evils of urban life for the working poor were becoming increasingly evident as a matter of public concern. The laissez-faire style of government management of the economy, in fashion for most of the Victorian era, was starting to give way to a New Liberalism that championed intervention on the part of the poor and disadvantaged. Around 1900, theorists began developing urban planning models to mitigate the consequences of the industrial age, by providing citizens, especially factory workers, with healthier environments. The following century would therefore be globally dominated by a central planning approach to urban planning, not representing an increment in the overall quality of the urban realm.

At the beginning of the 20th century, urban planning began to be recognized as a separate profession. The Town and Country Planning Association was founded in 1899 and the first academic course in Great Britain on urban planning was offered by the University of Liverpool in 1909.[16] In the 1920s, the ideas of modernism and uniformity began to surface in urban planning, and lasted until the 1970s. The architect Le Corbusier presented the Radiant City in 1933 as a city that grows up in the form of towers which offered a solution to the problem of pollution and over-crowding. But many planners started to believe that the ideas of modernism in urban planning led to higher crime rates and social problems.[3][17] In 1961 Jane Jacobs published The Death and Life of Great American Cities establishing the concept of livable streets, infusing urban renewal planners with a livable urban area perspective.[18] In the second half of the 20th century, urban planners gradually shifted their focus to individualism and diversity in urban centers.[19]

21st century practices

[edit]Urban planners studying the effects of increasing congestion in urban areas began to address the externalities, the negative impacts caused by induced demand from larger highway systems in western countries such as in the United States. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs predicted in 2018 that around 2.5 billion more people occupy urban areas by 2050 according to population elements of global migration. New planning theories have adopted non-traditional concepts such as Blue Zones and Innovation Districts to incorporate geographic areas within the city that allow for novel business development and the prioritization of infrastructure that would assist with improving the quality of life of citizens by extending their potential lifespan.

Planning practices have incorporated policy changes to help address anthropogenic (human caused) climate change. London began to charge a congestion charge for cars trying to access already crowded places in the city.[20] Cities nowadays stress the importance of public transit and cycling by adopting such policies.

Theories

[edit]

Planning theory is the body of scientific concepts, definitions, behavioral relationships, and assumptions that define the body of knowledge of urban planning. There are eight procedural theories of planning that remain the principal theories of planning procedure today: the rational-comprehensive approach, the incremental approach, the transactive approach, the communicative approach, the advocacy approach, the equity approach, the radical approach, and the humanist or phenomenological approach.[21] Some other conceptual planning theories include Ebenezer Howard's The Three Magnets theory that he envisioned for the future of British settlement, also his Garden Cities, the Concentric Model Zone also called the Burgess Model by sociologist Ernest Burgess, the Radburn Superblock that encourages pedestrian movement, the Sector Model and the Multiple Nuclei Model among others.[22]

Participatory urban planning

[edit]Participatory planning is an urban planning approach that involves the entire community in the planning process. Participatory planning in the United States emerged during the 1960s and 70s.[23]

Technical aspects

[edit]Technical aspects of urban planning involve the application of scientific, technical processes, considerations and features that are involved in planning for land use, urban design, natural resources, transportation, and infrastructure. Urban planning includes techniques such as: predicting population growth, zoning, geographic mapping and analysis, analyzing park space, surveying the water supply, identifying transportation patterns, recognizing food supply demands, allocating healthcare and social services, and analyzing the impact of land use.

In order to predict how cities will develop and estimate the effects of their interventions, planners use various models. These models can be used to indicate relationships and patterns in demographic, geographic, and economic data. They might deal with short-term issues such as how people move through cities, or long-term issues such as land use and growth.[24] One such model is the Geographic Information System (GIS) that is used to create a model of the existing planning and then to project future impacts on the society, economy and environment.

Building codes and other regulations dovetail with urban planning by governing how cities are constructed and used from the individual level.[25] Enforcement methodologies include governmental zoning, planning permissions, and building codes,[1] as well as private easements and restrictive covenants.[26]

Recent advances in urban planning include the use of urban digital twins (UDTs), which leverage artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT) to simulate and predict urban development scenarios. These technologies enable planners to collect real-time data, predict population growth, traffic patterns, and assess the environmental impact of urban interventions. AI and IoT are also employed to optimize resource allocation and improve sustainability by offering data-driven insights for long-term urban development planning[27]

With recent advances in information and communication technologies and the Internet of Things, an increasing number of cities are adopting technologies such as crowdsourced mobile phone sensing and machine learning to collect data and extract useful information to help make informed urban planning decisions.[28]

Urban planners

[edit]An urban planner is a professional who works in the field of urban planning for the purpose of optimizing the effectiveness of a community's land use and infrastructure. They formulate plans for the development and management of urban and suburban areas. They typically analyze land use compatibility as well as economic, environmental, and social trends. In developing any plan for a community (whether commercial, residential, agricultural, natural or recreational), urban planners must consider a wide array of issues including sustainability, existing and potential pollution, transport including potential congestion, crime, land values, economic development, social equity, zoning codes, and other legislation.

The importance of the urban planner is increasing in the 21st century, as modern society begins to face issues of increased population growth, climate change and unsustainable development.[29][30] An urban planner could be considered a green collar professional.[31]

Some researchers suggest that urban planners, globally, work in different "planning cultures", adapted to their cities and cultures.[32] However, professionals have identified skills, abilities, and basic knowledge sets that are common to urban planners across regional and national boundaries.[33][34][35]

Criticisms and debates

[edit]The school of neoclassical economics argues that planning is unnecessary, or even harmful, as market efficiency allows for effective land use.[36] A pluralist strain of political thinking argues in a similar vein that the government should not intrude in the political competition between different interest groups which decides how land is used.[36] The traditional justification for urban planning has in response been that the planner does to the city what the engineer or architect does to the home, that is, make it more amenable to the needs and preferences of its inhabitants.[36]

The widely adopted consensus-building model of planning, which seeks to accommodate different preferences within the community has been criticized for being based upon, rather than challenging, the power structures of the community.[37] Instead, agonism has been proposed as a framework for urban planning decision-making.[37]

Another debate within the urban planning field is about who is included and excluded in the urban planning decision-making process. Most urban planning processes use a top-down approach which fails to include the residents of the places where urban planners and city officials are working. Sherry Arnstein's "ladder of citizen participation" is often used by many urban planners and city governments to determine the degree of inclusivity or exclusivity of their urban planning.[38] One main source of engagement between city officials and residents are city council meetings that are open to the residents and that welcome public comments. Additionally, in US there are some federal requirements for citizen participation in government-funded infrastructure projects.[6]

Participatory urban planning has been criticized for contributing to the housing crisis in parts of the world.[39]

See also

[edit]- Air pollution

- Aire de mise en valeur de l'architecture et du paysage

- Behavioral urbanism

- Bicycle-friendly

- Blue space

- Circulation planning

- Curb cut effect

- Cycling infrastructure

- Development studies

- Domestic travel restrictions

- Epidemiology

- Green urbanism

- Hazard mitigation

- Index of urban planning articles

- Land recycling

- Landscape urbanism

- List of planned cities

- List of planning journals

- List of urban planners

- List of urban plans

- List of urban theorists

- Living street

- Low emission zone

- NIMBY

- New Urbanism

- Noise pollution

- Permeability

- Planning cultures

- Regional planning

- Road traffic safety

- Reurbanisation

- Rural development

- Tactical urbanism

- Smart city

- Sociotope

- Sponge city

- Street reclamation

- Stroad

- Sustainable urbanism

- Universal design

- Urban density

- Urban economics

- Urban planning education

- Urban green space

- Dark infrastructure

- Urban history

- Urban informatics

- Urban planning in communist countries

- Urban studies

- Urban theory

- Urban vitality

- Urbanism

- YIMBY

- Walkability

- Walking audit

- World Urbanism Day

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "What is Urban Planning". School of Urban Planning, McGill University. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Nigel (1998). Urban Planning Theory Since 1945. Los Angeles: Sage. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-7619-6093-5.

- ^ a b Midgley, James (1999). Social Development: The Developmental Perspective in Social Welfare. Sage. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8039-7773-0.

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 704. ISBN 978-0-415-86287-5.

- ^ Pobiner, Joe (18 February 2020). "3 urban planning trends that are changing how our cities will look in the future". Building Design + Construction. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ a b Levy, John M. (2017). Contemporary urban planning. Routledge, Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-138-66638-2. OCLC 992793499.

- ^ Van Assche, K.; Beunen, R.; Duineveld, M.; & de Jong, H. (2013). "Co-evolutions of planning and design: Risks and benefits of design perspectives in planning systems". Planning Theory, 12(2), 177–198.

- ^ "What Is Planning?". American Planning Association. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015.

- ^ Planetizen Courses (8 November 2019). "What is Urban Planning?". YouTube. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Hass-Klau, Carmen (2014). "Motorization and Footpath Planning During the Third Reich." The Pedestrian and the City. Routledge.

- ^ Davreu, Robert (1978). "Cities of Mystery: The Lost Empire of the Indus Valley". The World's Last Mysteries. (second edition). Sydney: Reader's Digest. pp. 121–129. ISBN 0-909486-61-1.

- ^ Kolb, Frank (1984). Die Stadt im Altertum. München: Verlag C.H. Beck, pp. 51–141: Morris, A. E. J. (1972). History of Urban Form. Prehistory to the Renaissance. London, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Glaeser, Edward (2011). Triumph of the City: How Our Best Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier. New York: Penguin Press, p. 19, ISBN 978-1-59420-277-3

- ^ Boerefijn, Wim (2010). The foundation, planning and building of new towns in the 13th and 14th centuries in Europe. An architectural-historical research into urban form and its creation. Phd. thesis Universiteit van Amsterdam. ISBN 978-90-9025157-8.

- ^ Jordan, David (1992). "Baron Haussmann and Modern Paris". American Scholar. 61 (1): 99.

- ^ Fainstein, Susan S. Urban planning at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Morris, Eleanor Smith; et al. (1997). British Town Planning and Urban Design: Principles and policies. Longman. pp. 147–149. ISBN 978-0-582-23496-3.

- ^ Carmen Hass-Klau (2014). The Pedestrian and the City. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-07890-4.

- ^ Routley, Nick (20 January 2018). "The Evolution of Urban Planning". Visual Capitalist. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "Congestion Charge (Official)". Transport for London. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Whittmore, Andrew (2 February 2015). "How Planners Use Planning Theory". Planetizen. Retrieved 24 April 2015. citing Whittemore, Andrew H. (2014). "Practitioners Theorize, Too Reaffirming Planning Theory in a Survey of Practitioners' Theories". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 35 (1): 76–85. doi:10.1177/0739456X14563144. S2CID 144888493.

- ^ Mohd Nazim Saifi (4 March 2017). "Town planning theories concept and models".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lane, Marcus B. (November 2005). "Public Participation in Planning: an intellectual history". Australian Geographer. 36 (3): 283–299. Bibcode:2005AuGeo..36..283L. doi:10.1080/00049180500325694. ISSN 0004-9182. S2CID 18008094.

- ^ Landis, John D. (2012). "Modeling Urban Systems". In Weber, Rachel; Crane, Randall (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Urban Planning. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 323–350. ISBN 978-0-19-537499-5.

- ^ Codes, rules, and standards are part of a matrix of relations that influence the practice of urban planning and design. These forms of regulation provide an important and inescapable framework for development, from the laying out of subdivisions to the control of stormwater runoff. The subject of regulations leads to the source of how communities are designed and constructed—defining how they can and can't be built—and how codes, rules, and standards continue to shape the physical space where we live and work. Ben-Joseph, Eran (2012). "Codes and Standards in Urban Planning and Design". In Weber, Rachel; Crane, Randall (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Urban Planning. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 352–370. ISBN 978-0-19-537499-5.

- ^ Smit, Anneke; Valiante, Marcia (2015). "Introduction". In Smit, Anneke; Valiante, Marcia (eds.). Public Interest, Private Property: Law and Planning Policy in Canada. Vancouver, British Columbia: University of British Columbia Press. pp. 1–36, page 10. ISBN 978-0-7748-2931-1.

- ^ Bibri, S. E.; Huang, J.; Jagatheesaperumal, S. K.; Krogstie, J. (2024). "The synergistic interplay of artificial intelligence and digital twin in environmentally planning sustainable smart cities". Environmental Science and Ecotechnology. 20 100433. doi:10.1016/j.ese.2024.100433. PMC 11145432. PMID 38831974.

- ^ Luis B. Elvas; Miguel Nunes; Joao C. Ferreira; Bruno Francisco; Jose A. Afonso (2024). "Georeferenced Analysis of Urban Nightlife and Noise Based on Mobile Phone Data". Applied Sciences. 14 (1): 362. doi:10.3390/app14010362. hdl:1822/89302.

- ^ Heidari, Hadi; Arabi, Mazdak; Warziniack, Travis; Sharvelle, Sybil (2021). "Effects of Urban Development Patterns on Municipal Water Shortage". Frontiers in Water. 3 694817. Bibcode:2021FrWat...394817H. doi:10.3389/frwa.2021.694817. ISSN 2624-9375.

- ^ Heidari, Hadi; Arabi, Mazdak; Warziniack, Travis; Kao, Shih-Chieh (June 2021). "Shifts in hydroclimatology of US megaregions in response to climate change". Environmental Research Communications. 3 (6): 065002. Bibcode:2021ERCom...3f5002H. doi:10.1088/2515-7620/ac0617. ISSN 2515-7620.

- ^ Kamenetz, Anya (14 January 2009). "Ten Best Green Jobs for the Next Decade". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ Friedman, John (2012). "Varieties of Planning Experience: Toward a Globalized Planning Culture?". In Weber, Rachel; Crane, Randall (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Urban Planning. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 87–98. ISBN 978-0-19-537499-5.

- ^ "American Institutes of Certified Planners Certification". American Planning Association. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ "Professional standards". Royal Institute of Town Planners. Royal Town Planning Institute. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ "About ISOCARP". International Society of City and Regional Planners. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Klosterman, Richard E. (1985). "Arguments for and against Planning". The Town Planning Review. 56 (1): 5–20. doi:10.3828/tpr.56.1.e8286q3082111km4. ISSN 0041-0020. JSTOR 40112168.

- ^ a b McAuliffe, Cameron; Rogers, Dallas (March 2019). "The politics of value in urban development: Valuing conflict in agonistic pluralism". Planning Theory. 18 (3): 300–318. doi:10.1177/1473095219831381. ISSN 1473-0952. S2CID 150714892.

- ^ Arnstein, Sherry (14 May 2020), ""A Ladder of Citizen Participation"", The City Reader, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, pp. 290–302, doi:10.4324/9780429261732-36, hdl:11250/2630064, ISBN 978-0-429-26173-2, S2CID 159193173

- ^ Einstein, Katherine Levine; Glick, David M.; Palmer, Maxwell (2020). "Neighborhood Defenders: Participatory Politics and America's Housing Crisis". Political Science Quarterly. 135 (2): 281–312. doi:10.1002/polq.13035.

Further reading

[edit]- Pennington, Mark (2008). "Urban planning". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 517–18. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n316. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024. S2CID 243497795.

- Knox, P. L. (2020) Better by Design?: Architecture, Urban Planning, and the Good City. Blacksburg: Virginia Tech Publishing. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21061/better-by-design

- Paul Waterhouse; Raymond Unwin (1912), Old Towns and New Needs; also the Town Extension Plan, Manchester: Victoria University of Manchester, OCLC 225676578, Wikidata Q18606907

External links

[edit]Library guides for urban planning

[edit]- "Urban Planning Resources". US: LibGuides at Arizona State University.

- "Urban Planning". Research Guides. University of California, Los Angeles Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library (September 2009). "Urban Planning: Basic Resources for Research". Research Guides. New York: Columbia University Libraries. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- "Urban and Regional Policy: Finding Articles". Research Guides. US: Georgia Tech. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022.

- Harvard University Graduate School of Design. "Urban Planning and Design". Research Guides. Massachusetts: Harvard Library.

- "Urban Affairs & Planning". Topic Guides. New York City: CUNY Hunter College Libraries. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- "City Planning". LibGuides. University of Illinois Library at University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Archived from the original on 23 August 2015.

- "Urban Studies & Planning". Research Guides. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Libraries. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014.

- "Urban and Regional Planning". Research Guides. US: University of Michigan Library.

- "Urban Studies & Planning". Oregon, US: LibGuides at Portland State University. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.