Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Adventism

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Adventism |

|---|

|

|

|

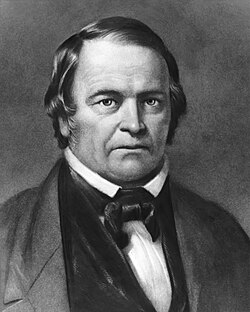

Adventism is a branch of Protestant Christianity[1][2] that believes in the imminent Second Coming (or the "Second Advent") of Jesus Christ. It originated in the 1830s in the United States during the Second Great Awakening when Baptist preacher William Miller first publicly shared his belief that the Second Coming would occur at some point between 1843 and 1844. His followers became known as Millerites. After Miller's prophecies failed, the Millerite movement split up and was continued by a number of groups that held different doctrines from one another. These groups, stemming from a common Millerite ancestor, collectively became known as the Adventist movement.

Although the Adventist churches hold much in common with mainline Christianity, their theologies differ on whether the intermediate state of the dead is unconscious sleep or consciousness, whether the ultimate punishment of the wicked is annihilation or eternal torment, the nature of immortality, whether the wicked are resurrected after the millennium, and whether the sanctuary of Daniel 8 refers to the one in heaven or one on earth.[1] Seventh-day Adventists and some smaller Adventist groups observe the seventh day Sabbath. The General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists has compiled that church's core beliefs in the 28 Fundamental Beliefs (1980 and 2005).

In 2010, Adventism claimed to have some 22 million believers who were scattered in various independent churches.[3] The largest church within the movement—the Seventh-day Adventist Church—had more than 23 million members in 2025.[4]

History

[edit]Adventism began as an inter-denominational movement. Its most vocal leader was William Miller. Between 50,000 and 100,000 people in the United States supported Miller's predictions of Christ's return. After the "Great Disappointment" of October 22, 1844, many people in the movement gave up on Adventism. Of those remaining Adventist, the majority gave up believing in any prophetic (biblical) significance for the October 22 date, yet they remained expectant of the near Advent (second coming of Jesus).[1][5]

Of those who retained the October 22 date, many maintained that Jesus had come not literally but "spiritually", and consequently were known as "spiritualizers". A small minority held that something concrete had indeed happened on October 22, but that this event had been misinterpreted. This belief later emerged and crystallized with the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the largest remaining body.[1][5]

Albany Conference (1845)

[edit]The Albany Conference in 1845, attended by 61 delegates, was called to attempt to determine the future course and meaning of the Millerite movement. Following this meeting, the "Millerites" then became known as "Adventists" or "Second Adventists". However, the delegates disagreed on several theological points. Four groups emerged from the conference: The Evangelical Adventists, The Life and Advent Union, the Advent Christian Church, and the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

The largest group was organized as the American Millennial Association, a portion of which was later known as the Evangelical Adventist Church.[1] Unique among the Adventists, they believed in an eternal hell and consciousness in death. They declined in numbers, and by 1916 their name did not appear in the United States Census of Religious Bodies. It has diminished to almost non-existence today. Their main publication was the Advent Herald,[6] of which Sylvester Bliss was the editor until his death in 1863. It was later called the Messiah's Herald.

The Life and Advent Union was founded by George Storrs in 1863. He had established The Bible Examiner in 1842. It merged with the Adventist Christian Church in 1964.

The Advent Christian Church officially formed in 1861 and grew rapidly at first. It declined a little during the 20th century. The Advent Christians publish the four magazines The Advent Christian Witness, Advent Christian News, Advent Christian Missions and Maranatha. They also operate a liberal arts college at Aurora, Illinois; and a one-year Bible College in Lenox, Massachusetts, called Berkshire Institute for Christian Studies.[7] The Primitive Advent Christian Church later separated from a few congregations in West Virginia.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church officially formed in 1863. It believes in the sanctity of the seventh-day Sabbath as a holy day for worship. It publishes the Adventist Review, which evolved from several early church publications. Youth publications include KidsView, Guide and Insight. It has grown to a large worldwide denomination and has a significant network of medical and educational institutions.

Miller did not join any of the movements, and he spent the last few years of his life working for unity, before dying in 1849.

Denominations

[edit]

The Handbook of Denominations in the United States, 12th ed., describes the following churches as "Adventist and Sabbatarian (Hebraic) Churches":

Christadelphians

[edit]The Christadelphians were founded in 1844 by John Thomas. In 2000, there were an estimated 25,000 members in 170 ecclesias, or churches, in the United States.

Advent Christian Church

[edit]The Advent Christian Church was founded in 1860 and had 25,277 members in 302 churches in 2002 in America. It is a "first-day" body of Adventist Christians founded on the teachings of William Miller. It adopted the "conditional immortality" doctrine of Charles F. Hudson and George Storrs, who formed the "Advent Christian Association" in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1860.

Primitive Advent Christian Church

[edit]The Primitive Advent Christian Church is a small group which separated from the Advent Christian Church. It differs from the parent body mainly on two points. Its members observe foot washing as a rite of the church, and they teach that reclaimed backsliders should be baptized (even though they had formerly been baptized). This is sometimes referred to as rebaptism.

Seventh-day Adventist Church

[edit]The Seventh-day Adventist Church, founded in 1863, had over 23,000,000 baptized members (not counting children of members) worldwide in 2025.[8] It is best known for its teaching that Saturday, the seventh day of the week, is the Sabbath and is the appropriate day for worship. However, the second coming of Jesus Christ, along with Judgment Day based on the three angels' message in Revelation 14:6–13, remain core beliefs of Seventh-day Adventists.

Seventh Day Adventist Reform Movement

[edit]The Seventh Day Adventist Reform Movement is a small offshoot with an unknown number of members from the Seventh-day Adventist Church caused by disagreement over military service on the Sabbath day during World War I.

Davidian Seventh-day Adventist Association

[edit]The Davidians (originally named Shepherd's Rod) is a small offshoot with an unknown number of members made up primarily of voluntarily disfellowshipped members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. They were originally known as the Shepherd's Rod and are still sometimes referred to as such. The group derives its name from two books on Bible doctrine written by its founder, Victor Houteff, in 1929.

- Branch Davidians

The Branch Davidians were a split ("branch") from the Davidians.

A group that gathered around David Koresh (the so-called Koreshians) abandoned Davidian teachings and turned into a religious cult. Many of them were killed during the infamous Waco Siege of April 1993.

Church of God (Seventh Day)

[edit]The Church of God (Seventh-Day) was founded in 1863 and it had an estimated 11,000 members in 185 churches in 1999 in America. Its founding members separated in 1858 from those Adventists associated with Ellen G. White who later organized themselves as Seventh-day Adventists in 1863. The Church of God (Seventh Day) split in 1933, creating two bodies: one headquartered in Salem, West Virginia, and known as the Church of God (7th day) – Salem Conference and the other one headquartered in Denver, Colorado and known as the General Conference of the Church of God (Seventh-Day). The Worldwide Church of God splintered from this.[9]

Church of God General Conference

[edit]Many denominations known as "Church of God" have Adventist origins.

The Church of God General Conference was founded in 1921 and had 7,634 members in 162 churches in 2004 in America. It is a nontrinitarian first-day Adventist Christian body which is also known as the Church of God of the Abrahamic Faith and the Church of God General Conference (Morrow, GA).

Creation Seventh-Day Adventist Church

[edit]The Creation Seventh-Day Adventist Church is a small group that broke off from the Seventh-Day Adventists in 1988, and organized itself as a church in 1991.

United Seventh-Day Brethren

[edit]The United Seventh-Day Brethren is a small Sabbatarian Adventist body. In 1947, several individuals and two independent congregations within the Church of God Adventist movement formed the United Seventh-Day Brethren, seeking to increase fellowship and to combine their efforts in evangelism, publications, and other .

Other minor Adventist groups

[edit]- True and Free Adventists, a Soviet Union offshoot

- At least two denominations and numerous individual churches with a charismatic or Pentecostal-type bent have been influenced by or were offshoots – see charismatic Adventism generally

- Church of the Blessed Hope, a first-day Adventist church

- United Sabbath-Day Adventist Church, an African-American offshoot of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in New York City

- Celestia, a Christian communal town near Laporte in Sullivan County, Pennsylvania, founded by Millerite Peter E. Armstrong. It disintegrated before the end of the 19th century[10]

Other relationships

[edit]Early in its development, the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell had close connections with the Millerite movement and stalwarts of the Adventist faith, including George Storrs and Joseph Seiss. Although both Jehovah's Witnesses and the Bible Students do not identify as part of the Millerite Adventist movement (or other denominations, in general), some theologians categorize these groups as Millerite Adventist because of their teachings regarding an imminent Second Coming and their use of specific dates. The various independent Bible Student groups currently have a cumulative membership of about 20,000 worldwide.[citation needed] According to the Watch Tower Society, there were about 8.8 million Jehovah's Witnesses worldwide as of 2024.[11]

See also

[edit]- Advent Christian Church

- Adventist and related churches

- List of Christian denominations#Millerites and comparable groups

- Seventh-day Adventist Church

- Other movements in Adventism

General:

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Mead, Frank S.; Hill, Samuel S.; Atwood, Craig D. (2006). "Adventist and Sabbatarian (Hebraic) Churches". Handbook of Denominations in the United States (12th ed.). Nashville, Tn: Abingdon Press. pp. 256–276.

- ^ Bergman, Jerry (1995). "The Adventist and Jehovah's Witness Branch of Protestantism". In Miller, Timothy (ed.). America's Alternative Religions. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. pp. 33–46. ISBN 978-0-7914-2397-4. Archived from the original on 2020-07-24.

- ^ "Christianity report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-05. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- ^ Witherspoon, Stanton (2025-05-14). "Adventist Membership Tops 23 Million with Surge in Africa and PNG". Spectrum Magazine. Retrieved 2025-05-29.

- ^ a b George Knight, A Brief History of Seventh-day Adventists.

- ^ "Partial archives". Adventistarchives.org. Archived from the original on 2009-09-05. Retrieved 2013-06-26.

- ^ "Berkshire Institute for Christian Studies".

- ^ Henao, Luis (July 8, 2025). "Newly elected Seventh-day Adventist Church leader reflects on challenges". Associated Press. Retrieved July 15, 2025.

- ^ Tarling, Lowell R. (1981). "The Churches of God". The Edges of Seventh-day Adventism: A Study of Separatist Groups Emerging from the Seventh-day Adventist Church (1844–1980). Barragga Bay, Bermagui South, NSW: Galilee Publications. pp. 24–41. ISBN 0-9593457-0-1.

- ^ "Celestia" blog by Jeff Crocombe, October 13, 2006

- ^ "2024 Grand Totals". Watchtower Bible and Tract Society. 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bergman, Jerry (1995). "The Adventist and Jehovah's Witness Branch of Protestantism". In Miller, Timothy (ed.). America's Alternative Religions. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. pp. 33–46. ISBN 978-0-7914-2397-4. Archived from the original on 2020-07-24.

- Butler, Jonathan. "From Millerism to Seventh-Day Adventism: Boundlessness to Consolidation", Church History, Vol. 55, 1986

- Jordan, Anne Devereaux. The Seventh-Day Adventists: A History (1988)

- Land, Gary. Adventism in America: A History (1998)

- Land, Gary. Historical Dictionary of the Seventh-Day Adventists (2005).

- Mead, Frank S.; Hill, Samuel S.; Atwood, Craig D. (2006). "Adventist and Sabbatarian (Hebraic) Churches". Handbook of Denominations in the United States (12th ed.). Nashville, Tn: Abingdon Press. pp. 256–276.

- Morgan, Douglas. Adventism and the American Republic: The Public Involvement of a Major Apocalyptic Movement (University of Tennessee Press, 2001) ISBN 1-57233-111-9

- Tarling, Lowell R. (1981). The Edges of Seventh-day Adventism: A Study of Separatist Groups Emerging from the Seventh-day Adventist Church (1844–1980). Barragga Bay, New South Wales: Galilee Publications. p. 81. ISBN 0-9593457-0-1.

External links

[edit]- History of the Millerite Movement, a reprint from the Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia 10:892–898, 1976.

- Graphical timeline of major Millerite groups from the Worldwide Church of God official website