Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Atmospheric physics

View on Wikipedia |

| Meteorology |

|---|

| Climatology |

| Aeronomy |

| Glossaries |

Within the atmospheric sciences, atmospheric physics is the application of physics to the study of the atmosphere. Atmospheric physicists attempt to model Earth's atmosphere and the atmospheres of the other planets using fluid flow equations, radiation budget, and energy transfer processes in the atmosphere (as well as how these tie into boundary systems such as the oceans). In order to model weather systems, atmospheric physicists employ elements of scattering theory, wave propagation models, cloud physics, statistical mechanics and spatial statistics which are highly mathematical and related to physics. It has close links to meteorology and climatology and also covers the design and construction of instruments for studying the atmosphere and the interpretation of the data they provide, including remote sensing instruments. At the dawn of the space age and the introduction of sounding rockets, aeronomy became a subdiscipline concerning the upper layers of the atmosphere, where dissociation and ionization are important.

Remote sensing

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

Remote sensing is the small or large-scale acquisition of information of an object or phenomenon, by the use of either recording or real-time sensing device(s) that is not in physical or intimate contact with the object (such as by way of aircraft, spacecraft, satellite, buoy, or ship). In practice, remote sensing is the stand-off collection through the use of a variety of devices for gathering information on a given object or area which gives more information than sensors at individual sites might convey.[1] Thus, Earth observation or weather satellite collection platforms, ocean and atmospheric observing weather buoy platforms, monitoring of a pregnancy via ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron-emission tomography (PET), and space probes are all examples of remote sensing. In modern usage, the term generally refers to the use of imaging sensor technologies including but not limited to the use of instruments aboard aircraft and spacecraft, and is distinct from other imaging-related fields such as medical imaging.

There are two kinds of remote sensing. Passive sensors detect natural radiation that is emitted or reflected by the object or surrounding area being observed. Reflected sunlight is the most common source of radiation measured by passive sensors. Examples of passive remote sensors include film photography, infrared, charge-coupled devices, and radiometers. Active collection, on the other hand, emits energy in order to scan objects and areas whereupon a sensor then detects and measures the radiation that is reflected or backscattered from the target. radar, lidar, and SODAR are examples of active remote sensing techniques used in atmospheric physics where the time delay between emission and return is measured, establishing the location, height, speed and direction of an object.[2]

Remote sensing makes it possible to collect data on dangerous or inaccessible areas. Remote sensing applications include monitoring deforestation in areas such as the Amazon Basin, the effects of climate change on glaciers and Arctic and Antarctic regions, and depth sounding of coastal and ocean depths. Military collection during the Cold War made use of stand-off collection of data about dangerous border areas. Remote sensing also replaces costly and slow data collection on the ground, ensuring in the process that areas or objects are not disturbed.

Orbital platforms collect and transmit data from different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, which in conjunction with larger scale aerial or ground-based sensing and analysis, provides researchers with enough information to monitor trends such as El Niño and other natural long and short term phenomena. Other uses include different areas of the earth sciences such as natural resource management, agricultural fields such as land usage and conservation, and national security and overhead, ground-based and stand-off collection on border areas.[3]

Radiation

[edit]

Atmospheric physicists typically divide radiation into solar radiation (emitted by the sun) and terrestrial radiation (emitted by Earth's surface and atmosphere).

Solar radiation contains variety of wavelengths. Visible light has wavelengths between 0.4 and 0.7 micrometers.[4] Shorter wavelengths are known as the ultraviolet (UV) part of the spectrum, while longer wavelengths are grouped into the infrared portion of the spectrum.[5] Ozone is most effective in absorbing radiation around 0.25 micrometers,[6] where UV-c rays lie in the spectrum. This increases the temperature of the nearby stratosphere. Snow reflects 88% of UV rays,[6] while sand reflects 12%, and water reflects only 4% of incoming UV radiation.[6] The more glancing the angle is between the atmosphere and the sun's rays, the more likely that energy will be reflected or absorbed by the atmosphere.[7]

Terrestrial radiation is emitted at much longer wavelengths than solar radiation. This is because Earth is much colder than the sun. Radiation is emitted by Earth across a range of wavelengths, as formalized in Planck's law. The wavelength of maximum energy is around 10 micrometers.

Cloud physics

[edit]Cloud physics is the study of the physical processes that lead to the formation, growth and precipitation of clouds. Clouds are composed of microscopic droplets of water (warm clouds), tiny crystals of ice, or both (mixed phase clouds). Under suitable conditions, the droplets combine to form precipitation, where they may fall to the earth.[8] The precise mechanics of how a cloud forms and grows is not completely understood, but scientists have developed theories explaining the structure of clouds by studying the microphysics of individual droplets. Advances in radar and satellite technology have also allowed the precise study of clouds on a large scale.

Atmospheric electricity

[edit]

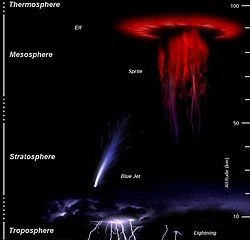

Atmospheric electricity is the term given to the electrostatics and electrodynamics of the atmosphere (or, more broadly, the atmosphere of any planet). The Earth's surface, the ionosphere, and the atmosphere is known as the global atmospheric electrical circuit.[9] Lightning discharges 30,000 amperes, at up to 100 million volts, and emits light, radio waves, X-rays and even gamma rays.[10] Plasma temperatures in lightning can approach 28,000 kelvins and electron densities may exceed 1024/m3.[11]

Atmospheric tide

[edit]The largest-amplitude atmospheric tides are mostly generated in the troposphere and stratosphere when the atmosphere is periodically heated as water vapour and ozone absorb solar radiation during the day. The tides generated are then able to propagate away from these source regions and ascend into the mesosphere and thermosphere. Atmospheric tides can be measured as regular fluctuations in wind, temperature, density and pressure. Although atmospheric tides share much in common with ocean tides they have two key distinguishing features:

i) Atmospheric tides are primarily excited by the Sun's heating of the atmosphere whereas ocean tides are primarily excited by the Moon's gravitational field. This means that most atmospheric tides have periods of oscillation related to the 24-hour length of the solar day whereas ocean tides have longer periods of oscillation related to the lunar day (time between successive lunar transits) of about 24 hours 51 minutes.[12]

ii) Atmospheric tides propagate in an atmosphere where density varies significantly with height. A consequence of this is that their amplitudes naturally increase exponentially as the tide ascends into progressively more rarefied regions of the atmosphere (for an explanation of this phenomenon, see below). In contrast, the density of the oceans varies only slightly with depth and so there the tides do not necessarily vary in amplitude with depth.

Note that although solar heating is responsible for the largest-amplitude atmospheric tides, the gravitational fields of the Sun and Moon also raise tides in the atmosphere, with the lunar gravitational atmospheric tidal effect being significantly greater than its solar counterpart.[13]

At ground level, atmospheric tides can be detected as regular but small oscillations in surface pressure with periods of 24 and 12 hours. Daily pressure maxima occur at 10 a.m. and 10 p.m. local time, while minima occur at 4 a.m. and 4 p.m. local time. The absolute maximum occurs at 10 a.m. while the absolute minimum occurs at 4 p.m.[14] However, at greater heights the amplitudes of the tides can become very large. In the mesosphere (heights of ~ 50 – 100 km) atmospheric tides can reach amplitudes of more than 50 m/s and are often the most significant part of the motion of the atmosphere.

Aeronomy

[edit]

Aeronomy is the science of the upper region of the atmosphere, where dissociation and ionization are important. The term aeronomy was introduced by Sydney Chapman in 1960.[15] Today, the term also includes the science of the corresponding regions of the atmospheres of other planets. Research in aeronomy requires access to balloons, satellites, and sounding rockets which provide valuable data about this region of the atmosphere. Atmospheric tides play an important role in interacting with both the lower and upper atmosphere. Amongst the phenomena studied are upper-atmospheric lightning discharges, such as luminous events called red sprites, sprite halos, blue jets, and elves.

Centers of research

[edit]In the UK, atmospheric studies are underpinned by the Met Office, the Natural Environment Research Council and the Science and Technology Facilities Council. Divisions of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) oversee research projects and weather modeling involving atmospheric physics. The US National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center also carries out studies of the high atmosphere. In Belgium, the Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy studies the atmosphere and outer space. In France, there are several public or private entities researching the atmosphere, as an example météo-France (Météo-France), several laboratories in the national scientific research center (such as the laboratories in the IPSL group).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ COMET program (1999). Remote Sensing. Archived 2013-05-07 at the Wayback Machine University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Retrieved on 2009-04-23.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Radar. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2009-24-23.

- ^ NASA (2009). Earth. Archived 2006-09-29 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2009-02-18.

- ^ Atmospheric Science Data Center. What Wavelength Goes With a Color? Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-04-15.

- ^ Windows to the Universe. Solar Energy in Earth's Atmosphere. Archived 2010-01-31 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-04-15.

- ^ a b c University of Delaware. Geog 474: Energy Interactions with the Atmosphere and at the Surface. Retrieved on 2008-04-15.

- ^ Wheeling Jesuit University. Exploring the Environment: UV Menace. Archived August 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2007-06-01.

- ^ Oklahoma Weather Modification Demonstration Program. CLOUD PHYSICS. Archived 2008-07-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-04-15.

- ^ Dr. Hugh J. Christian and Melanie A. McCook. Lightning Detection From Space: A Lightning Primer. Archived April 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-04-17.

- ^ NASA. Flashes in the Sky: Earth's Gamma-Ray Bursts Triggered by Lightning. Retrieved on 2007-06-01.

- ^ Fusion Energy Education.Lightning! Sound and Fury. Archived 2016-11-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-04-17.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology. Atmospheric Tide. Retrieved on 2008-04-15.

- ^ Scientific American. Does the Moon have a tidal effect on the atmosphere as well as the oceans?. Retrieved on 2008-07-08.

- ^ Dr James B. Calvert. Tidal Observations. Retrieved on 2008-04-15.

- ^ Andrew F. Nagy, p. 1-2 in Comparative Aeronomy, ed. by Andrew F. Nagy et al. (Springer 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-87824-9)

Further reading

[edit]- J. V. Iribarne, H. R. Cho, Atmospheric Physics, D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1980.

External links

[edit] Media related to Atmospheric physics at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Atmospheric physics at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg/250px-ISS-48_Towering_cumulonimbus_and_other_clouds_over_the_Earth_(2).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-ISS-48_Towering_cumulonimbus_and_other_clouds_over_the_Earth_(2).jpg)