Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Back-arc basin

View on Wikipedia

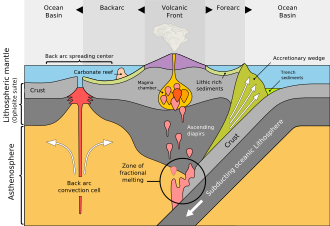

A back-arc basin is a type of geologic basin, found at some convergent plate boundaries. Presently all back-arc basins are submarine features associated with island arcs and subduction zones, with many found in the western Pacific Ocean. Most of them result from tensional forces, caused by a process known as oceanic trench rollback, where a subduction zone moves towards the subducting plate.[1] Back-arc basins were initially an unexpected phenomenon in plate tectonics, as convergent boundaries were expected to universally be zones of compression. However, in 1970, Dan Karig published a model of back-arc basins consistent with plate tectonics.[2]

Structural characteristics

[edit]Back-arc basins are typically very long and relatively narrow, often thousands of kilometers long while only being a few hundred kilometers wide at most. For back-arc extension to form, a subduction zone is required, but not all subduction zones have a back-arc extension feature.[3] Back-arc basins are found in areas where the subducting plate of oceanic crust is very old.[3] The restricted width of back-arc basins is due to magmatic activity being reliant on water and induced mantle convection, limiting their formation to along subduction zones.[3] Spreading rates vary from only a few centimeters per year (as in the Mariana Trough), to 15 cm/year in the Lau Basin.[4] Spreading ridges within the basins erupt basalts that are similar to those erupted from the mid-ocean ridges; the main difference being back-arc basin basalts are often very rich in magmatic water (typically 1–1.5 weight % H2O), whereas mid-ocean ridge basalt magmas are very dry (typically <0.3 weight % H2O). The high water contents of back-arc basin basalt magmas is derived from water carried down the subduction zone and released into the overlying mantle wedge.[1] Additional sources of water could be the eclogitization of amphiboles and micas in the subducting slab. Similar to mid-ocean ridges, back-arc basins have hydrothermal vents and associated chemosynthetic communities.

Seafloor spreading

[edit]Evidence of seafloor spreading has been seen in cores of the basin floor. The thickness of sediment that collected in the basin decreased toward the center of the basin, indicating a younger surface. The idea that thickness and age of sediment on the sea floor is related to the age of the oceanic crust was proposed by Harry Hess.[5] Magnetic anomalies of the crust that had formed in back-arc basins deviated in form from the crust formed at mid-ocean ridges.[2] In many areas the anomalies do not appear parallel, as well as the profiles of the magnetic anomalies in the basin lacking symmetry or a central anomaly as a traditional ocean basin does, indicating asymmetric seafloor spreading.[2]

This has prompted some to characterize the spreading in back-arc basins to be more diffused and less uniform than at mid-ocean ridges.[6] The idea that back-arc basin spreading is inherently different from mid-ocean ridge spreading is controversial and has been debated through the years.[6] Another argument put forward is that the process of seafloor spreading is the same in both cases, but the movement of seafloor spreading centers in the basin causes the asymmetry in the magnetic anomalies.[6] This process can be seen in the Lau back-arc basin.[6] Though the magnetic anomalies are more complex to decipher, the rocks sampled from back-arc basin spreading centers do not differ very much from those at mid-ocean ridges.[7] In contrast, the volcanic rocks of the nearby island arc differ significantly from those in the basin.[7]

Back-arc basins are different from normal mid-ocean ridges because they are characterized by asymmetric seafloor spreading, but this is quite variable even within single basins. For example, in the central Mariana Trough, current spreading rates are 2–3 times greater on the western flank,[8] whereas at the southern end of the Mariana Trough the position of the spreading center adjacent to the volcanic front suggests that overall crustal accretion has been nearly entirely asymmetric there.[9] This situation is mirrored to the north where a large spreading asymmetry is also developed.[10]

Other back-arc basins such as the Lau Basin have undergone large rift jumps and propagation events (sudden changes in relative rift motion) that have transferred spreading centers from arc-distal to more arc-proximal positions.[11] Conversely, study of recent spreading rates appear to be relatively symmetric with perhaps small rift jumps.[12] The cause of asymmetric spreading in back-arc basins remains poorly understood. General ideas invoke asymmetries relative to the spreading axis in arc melt generation processes and heat flow, hydration gradients with distance from the slab, mantle wedge effects, and evolution from rifting to spreading.[13][14][15]

Formation and tectonics

[edit]The extension of the crust behind volcanic arcs is believed to be caused by processes in association with subduction.[1] As the subducting plate descends into the asthenosphere it sheds water, causing mantle melting, volcanism, and the formation of island arcs. Another result of this is a convection cell is formed.[1] The rising magma and heat along with the outwards tension in the crust in contact with the convection cell cause a region of melt to form, resulting in a rift. This process drives the island arc toward the subduction zone and the rest of the plate away from the subduction zone.[1] The backward motion of the subduction zone relative to the motion of the plate which is being subducted is called trench rollback (also known as hinge rollback or hinge retreat). As the subduction zone and its associated trench pull backward, the overriding plate is stretched, thinning the crust and forming a back-arc basin. In some cases, extension is triggered by the entrance of a buoyant feature in the subduction zone, which locally slows down subduction and induces the subducting plate to rotate adjacent to it. This rotation is associated with trench retreat and overriding plate extension.[9]

The age of the subducting crust needed to establish back-arc spreading has been found to be 55 million years old or older.[15][3] This is why back-arc spreading centers appear concentrated in the western Pacific.[3] The dip angle of the subducting slab may also be significant, as is shown to be greater than 30° in areas of back-arc spreading; this is most likely because as oceanic crust gets older it becomes denser, resulting in a steeper angle of descent.[3]

The thinning of the overriding plate from back-arc rifting can lead to the formation of new oceanic crust (i.e., back-arc spreading). As the lithosphere stretches, the asthenosphere below rises to shallow depths and partially melts as a result of adiabatic decompression melting. As this melt nears the surface, spreading begins.

Sedimentation

[edit]Sedimentation is strongly asymmetric, with most of the sediment supplied from the active volcanic arc which regresses in step with the rollback of the trench.[16] From cores collected during the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) nine sediment types were found in the back-arc basins of the western Pacific.[16] Debris flows of thick to medium bedded massive conglomerates account for 1.2% of sediments collected by the DSDP.[16] The average size of the sediments in the conglomerates are pebble sized but can range from granules to cobbles.[16] Accessory materials include limestone fragments, chert, shallow water fossils and sandstone clasts.[16]

Submarine fan systems of interbedded turbidite sandstone and mudstone made up 20% of the total thickness of sediment recovered by the DSDP.[16] The fans can be divided into two sub-systems based on the differences in lithology, texture, sedimentary structures, and bedding style.[16] These systems are inner and midfan subsystem and the outer fan subsystem.[16] The inner and midfan system contains interbedded thin to medium bedded sandstones and mudstones.[16] Structures that are found in these sandstones include load clasts, micro-faults, slump folds, convolute laminations, dewatering structures, graded bedding, and gradational tops of sandstone beds.[16] Partial Bouma sequences can be found within the subsystem.[16] The outer fan subsystem generally consists of finer sediments when compared to the inner and midfan system.[16] Well sorted volcanoclastic sandstones, siltstones and mudstones are found in this system.[16] Sedimentary structures found in this system include parallel laminae, micro-cross laminae, and graded bedding.[16] Partial Bouma sequences can be identified in this subsystem.[16]

Pelagic clays containing iron-manganese micronodules, quartz, plagioclase, orthoclase, magnetite, volcanic glass, montmorillonite, illite, smectite, foraminiferal remains, diatoms, and sponge spicules made up the uppermost stratigraphic section at each site it was found. This sediment type consisted of 4.2% of the total thickness of sediment recovered by the DSDP.[16]

Biogenic pelagic silica sediments consist of radiolarian, diatomaceous, silicoflagellate oozes, and chert.[16] It makes up 4.3% of the sediment thickness recovered.[16] Biogenic pelagic carbonates is the most common sediment type recovered from the back-arc basins of the western Pacific.[16] This sediment type made up 23.8% of the total thickness of sediment recovered by the DSDP.[16] The pelagic carbonates consist of ooze, chalk, and limestone.[16] Nanofossils and foraminifera make up the majority of the sediment.[16] Resedimented carbonates made up 9.5% of the total thickness of sediment recovered by the DSDP.[16] This sediment type had the same composition as the biogenic pelagic carbonated, but it had been reworked with well-developed sedimentary structures.[16] Pyroclastics consisting of volcanic ash, tuff and a host of other constituents including nanofossils, pyrite, quartz, plant debris, and glass made up 9.5% of the sediment recovered.[16] These volcanic sediments were sourced form the regional tectonic controlled volcanism and the nearby island arc sources.[16]

Locations

[edit]

Active back-arc basins are found in the Marianas, Kermadec-Tonga, South Scotia, Manus, North Fiji, and Tyrrhenian Sea regions, but most are found in the western Pacific. Not all subduction zones have back-arc basins; some, like the central Andes, are associated with rear-arc compression.

There are a number of extinct or fossil back-arc basins, such as the Parece Vela-Shikoku Basin, Sea of Japan, and Kurile Basin. Compressional back-arc basins are found, for example, in the Pyrenees and the Swiss Alps.[17]

History of thought

[edit]With the development of plate tectonic theory, geologists thought that convergent plate margins were zones of compression, thus zones of strong extension above subduction zones (back-arc basins) were not expected. The hypothesis that some convergent plate margins were actively spreading was developed by Dan Karig in 1970, while a graduate student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.[2] This was the result of several marine geologic expeditions to the western Pacific.

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Forsyth, D; Uyeda, S (1975). "On the Relative Importance of the Driving Forces of Plate Motion". Geophysical Journal International. 7 (4): 163–200. Bibcode:1975GeoJ...43..163F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1975.tb00631.x.

- ^ a b c d Karig, Daniel (1970). "Ridges and basins of the Tonga-Kermadec island arc system". Journal of Geophysical Research. 75 (2): 239–254. Bibcode:1970JGR....75..239K. doi:10.1029/JB075i002p00239.

- ^ a b c d e f Sdrolias, M; Muller, R.D. (2006). "Controls on back-arc basin formations". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 7 (4): Q04016. Bibcode:2006GGG.....7.4016S. doi:10.1029/2005GC001090. S2CID 129068818.

- ^ Taylor, B.; Zellmer, K.; Martinez, F.; Goodliffe, A. (1996). "Sea-floor Spreading in the Lau Back-arc Basin". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 144 (1–2): 35–40. Bibcode:1996E&PSL.144...35T. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(96)00148-3. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ Hess, Henry H (1962). "History of Ocean Basins". Petrological Studies: A Volume to Honor A .F. Buddington. pp. 599–620. OCLC 881288.

- ^ a b c d Taylor, B; Zellmer, K; Martinez, F; Goodliffe, A (1996). "Sea-floor spreading in the Lau back-arc basin". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 144 (1–2): 35–40. Bibcode:1996E&PSL.144...35T. doi:10.1016/0012-821x(96)00148-3.

- ^ a b Gill, J.B. (1976). "Composition and age of Lau Basin and Ridge volcanic rocks: Implications for evolution of an interarc basin and remnant arc". GSA Bulletin. 87 (10): 1384–1395. Bibcode:1976GSAB...87.1384G. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1976)87<1384:CAAOLB>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Deschamps, A.; Fujiwara, T. (2003). "Asymmetric accretion along the slow-spreading Mariana Ridge". Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4 (10): 8622. Bibcode:2003GGG.....4.8622D. doi:10.1029/2003GC000537.

- ^ a b Martinez, F.; Fryer, P.; Becker, N. (2000). "Geophysical Characteristics of the Southern Mariana Trough, 11N–13N". J. Geophys. Res. 105 (B7): 16591–16607. Bibcode:2000JGR...10516591M. doi:10.1029/2000JB900117.

- ^ Yamazaki, T.; Seama, N.; Okino, K.; Kitada, K.; Joshima, M.; Oda, H.; Naka, J. (2003). "Spreading process of the northern Mariana Trough: Rifting-spreading transition at 22 N". Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4 (9): 1075. Bibcode:2003GGG.....4.1075Y. doi:10.1029/2002GC000492.

- ^ Parson, L.M.; Pearce, J.A.; Murton, B.J.; Hodkinson, R.A.; RRS Charles Darwin Scientific Party (1990). "Role of ridge jumps and ridge propagation in the tectonic evolution of the Lau back-arc basin, southwest Pacific". Geology. 18 (5): 470–473. Bibcode:1990Geo....18..470P. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1990)018<0470:RORJAR>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Zellmer, K.E.; Taylor, B. (2001). "A three-plate kinematic model for Lau Basin opening". Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2 (5): 1020. Bibcode:2001GGG.....2.1020Z. doi:10.1029/2000GC000106. 2000GC000106.

- ^ Barker, P.F.; Hill, I.A. (1980). "Asymmetric spreading in back-arc basins". Nature. 285 (5767): 652–654. Bibcode:1980Natur.285..652B. doi:10.1038/285652a0. S2CID 4233630.

- ^ Martinez, F.; Fryer, P.; Baker, N.A.; Yamazaki, T. (1995). "Evolution of backarc rifting: Mariana Trough, 20–24N". J. Geophys. Res. 100 (B3): 3807–3827. Bibcode:1995JGR...100.3807M. doi:10.1029/94JB02466. Archived from the original on 2011-08-27. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ^ a b Molnar, P.; Atwater, T. (1978). "Interarc spreading and Cordilleran tectonics as alternates related to the age of subducted oceanic lithosphere". Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 41 (3): 330–340. Bibcode:1978E&PSL..41..330M. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(78)90187-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Klein, G.D. (1985). "The Control of Depositional Depth, Tectonic Uplift, and Volcanism on Sedimentation Processes in the Back-Arc Basins of the Western Pacific Ocean". Journal of Geology. 93 (1): 1–25. Bibcode:1985JG.....93....1D. doi:10.1086/628916. S2CID 129527339.

- ^ Munteanu, I.; et al. (2011). "Kinematics of back-arc inversion of the Western Black Sea Basin". Tectonics. 30 (5): n/a. Bibcode:2011Tecto..30.5004M. doi:10.1029/2011tc002865.

General and cited references

[edit]- Barker, P.F.; Hill, I.A. (1980). "Asymmetric spreading in back-arc basins". Nature. 285 (5767): 652–654. Bibcode:1980Natur.285..652B. doi:10.1038/285652a0. S2CID 4233630.

- Deschamps, A.; Fujiwara, T. (2003). "Asymmetric accretion along the slow-spreading Mariana Ridge". Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4 (10): 8622. Bibcode:2003GGG.....4.8622D. doi:10.1029/2003GC000537.

- Forsyth, D.; Uyeda, S. (1975). "On the Relative Importance of the Driving Forces of Plate Motion*". Geophysical Journal International. 43 (1): 163–200. Bibcode:1975GeoJ...43..163F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246x.1975.tb00631.x.

- Gill, J.B. (1976). "Composition and age of Lau Basin and Ridge volcanic rocks: Implications for evolution of an interarc basin and remnant arc". GSA Bulletin. 87 (10): 1384–1395. Bibcode:1976GSAB...87.1384G. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1976)87<1384:caaolb>2.0.co;2.

- Hess, Henry H. (1962). "History of Ocean Basins". Petrological Studies: A Volume to Honor A .F. Buddington. 599–620. OCLC 881288.

- Karig, Daniel E (1970). "Ridges and basins of the Tonga-Kermadec island arc system". Journal of Geophysical Research. 75 (2): 239–254. Bibcode:1970JGR....75..239K. doi:10.1029/JB075i002p00239.

- Klein, G.D. (1985). "The Control of Depositional Depth, Tectonic Uplift, and Volcanism on Sedimentation Processes in the Back-Arc Basins of the Western Pacific Ocean". Journal of Geology. 93 (1): 1–25. Bibcode:1985JG.....93....1D. doi:10.1086/628916. S2CID 129527339.

- Martinez, F.; Fryer, P.; Baker, N.A.; Yamazaki, T. (1995). "Evolution of backarc rifting: Mariana Trough, 20–24N". J. Geophys. Res. 100 (B3): 3807–3827. Bibcode:1995JGR...100.3807M. doi:10.1029/94JB02466.

- Martinez, F.; Fryer, P.; Becker, N. (2000). "Geophysical Characteristics of the Southern Mariana Trough, 11N–13N". J. Geophys. Res. 105 (B7): 16591–16607. Bibcode:2000JGR...10516591M. doi:10.1029/2000JB900117.

- Molnar, P.; Atwater, T. (1978). "Interarc spreading and Cordilleran tectonics as alternates related to the age of subducted oceanic lithosphere". Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 41 (3): 330–340. Bibcode:1978E&PSL..41..330M. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(78)90187-5.

- Parson, L.M.; Pearce, J.A.; Murton, B.J.; Hodkinson, R.A. (1990). "Role of ridge jumps and ridge propagation in the tectonic evolution of the Lau back-arc basin, southwest Pacific". Geology. 18 (5): 470–473. Bibcode:1990Geo....18..470P. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1990)018<0470:RORJAR>2.3.CO;2.

- Sdrolias, M.; Muller, R.D. (2006). "Controls on back-arc basin formations". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 7 (4): 1–40. Bibcode:2006GGG.....7.4016S. doi:10.1029/2005GC001090. S2CID 129068818.

- Taylor, Brian (1995). Backarc Basins: Tectonics and Magmatism. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 9780306449376. OCLC 32464941.

- Taylor, B.; Zellmer, K.; Martinez, F.; Goodliffe, A. (1996). "Sea-floor spreading in the Lau back-arc basin". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 144 (1–2): 35–40. Bibcode:1996E&PSL.144...35T. doi:10.1016/0012-821x(96)00148-3.

- Uyeda S (1984). "Subduction zones: their diversity, mechanism and human impact". GeoJournal. 8 (1): 381–406. Bibcode:1984GeoJo...8..381U. doi:10.1007/BF00185938. S2CID 128986436.

- Wallace, Laura M.; Ellis, Susan; Mann, Paul (2009). "Collisional model for rapid fore-arc block rotations, arc curvature, and episodic back-arc rifting in subduction settings". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 10 (5): n/a. Bibcode:2009GGG....10.5001W. doi:10.1029/2008gc002220.

- Yamazaki, T.; Seama, N.; Okino, K.; Kitada, K.; Joshima, M.; Oda, H.; Naka, J. (2003). "Spreading process of the northern Mariana Trough: Rifting-spreading transition at 22 N". Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4 (9): 1075. Bibcode:2003GGG.....4.1075Y. doi:10.1029/2002GC000492.

- Zellmer, K.E.; Taylor, B. (2001). "A three-plate kinematic model for Lau Basin opening". Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2 (5): 1020. Bibcode:2001GGG.....2.1020Z. doi:10.1029/2000GC000106.

External links

[edit]- Animation of subduction, trench rollback and back-arc basin expansion in EGU GIFT2017: Shaping the Mediterranean from the Inside Out, via YouTube

Back-arc basin

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

A back-arc basin is a geologic feature that forms in subduction zones, where one tectonic plate is forced beneath another, leading to the development of a volcanic arc on the overriding plate due to partial melting of the subducting slab and overlying mantle.[6] These basins are positioned behind (landward of) the volcanic arc, within the overriding plate, and represent areas of extensional tectonics driven by tension associated with subduction dynamics.[3] Specifically, back-arc basins are depressions characterized by rifting and crustal extension behind the volcanic arc, often resulting from the rollback of the subducting slab, which induces tensional forces in the overriding plate.[7] This distinguishes them from fore-arc basins, which lie between the subduction trench and the volcanic arc, typically experiencing compressional deformation and sediment accretion rather than extension.[3] Morphologically, back-arc basins are typically elongated marginal seas with thinned continental or oceanic crust, ranging from 5 to 15 km in thickness, elevated heat flow averaging around 95 mW/m², and prominent active faulting along rift zones.[4][8] These features often evolve to include seafloor spreading, producing new oceanic crust similar to mid-ocean ridges.[3]Geological significance

Back-arc basins play a pivotal role in global plate tectonics by enabling extension behind volcanic arcs, which accommodates the rollback of subducting slabs and contributes to the production of new oceanic crust through rifting and seafloor spreading.[3] This process integrates back-arc basins into the broader subduction system, where they facilitate dynamic interactions between converging plates, including enhanced mantle flow and crustal thinning that support subduction efficiency.[2] Furthermore, the accretion of arc-derived materials from back-arc settings to continental margins promotes long-term continental growth, as volcanic arcs and associated sediments are incorporated into overriding plates over geologic time.[2] Economically, back-arc basins hold substantial value due to their hydrocarbon potential, including reservoirs of gas hydrates formed under suitable pressure-temperature conditions in sedimentary layers, as documented in the Ulleung Basin of the East Sea.[9] They also host volcanogenic massive sulfide deposits rich in copper, zinc, lead, gold, and silver, formed by hydrothermal activity at spreading centers, making them key targets for marine mineral exploration.[10] High geothermal gradients driven by mantle upwelling and slab-derived fluids further enhance their importance, providing opportunities for renewable energy extraction, particularly in regions like the Sumatra back-arc basins where heat flow exceeds 100 mW/m².[11] From a scientific perspective, back-arc basins function as natural laboratories for examining mantle convection patterns induced by slab pull and rollback, revealing how subducting plates dehydrate and release fluids that hydrate the overlying mantle wedge.[12] These settings elucidate connections between arc-front and back-arc magmatism, with geochemical signatures tracing fluid and melt migration from the slab to the surface, thus informing models of subduction zone evolution.[13] Active basins signal vigorous subduction, while fossil examples preserve records of ancient tectonic regimes, aiding reconstructions of Earth's convective history. Environmentally, back-arc basins shape regional ocean circulation by creating semi-enclosed marginal seas that modify current pathways and nutrient distribution. They foster exceptional biodiversity, especially at hydrothermal vents where chemosynthetic communities thrive on geochemical gradients, supporting endemic species adapted to extreme conditions.[14] Additionally, rifting and associated faulting in these basins amplify seismic hazards, contributing to earthquake risks in subduction-related zones through stress accumulation and release.[15]Formation and Tectonics

Formation mechanisms

Back-arc basins primarily form through the process of slab rollback, in which the subducting oceanic plate steepens and retreats, inducing extension in the overriding plate behind the volcanic arc.[2] This rollback occurs as the negatively buoyant slab pulls the trench away from the overriding plate, creating tensional stresses that lead to rifting and basin initiation.[4] Hinge retreat at the subduction zone further facilitates this extension by allowing the subduction hinge to migrate trenchward, effectively lengthening the mantle wedge and accommodating back-arc spreading.[2] In a simple kinematic model, the extension rate in the back-arc region approximates the rollback velocity of the slab, assuming minimal motion of the overriding plate relative to the mantle. Secondary factors contributing to back-arc basin development include trench migration driven by slab pull, which enhances the overall extensional regime, and asthenospheric upwelling in the mantle wedge induced by the retreating slab.[3] This upwelling promotes decompression melting and further weakens the lithosphere, aiding rifting.[3] Gravitational instabilities within the mantle wedge, such as convective downwellings or Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities, can also drive localized extension by facilitating material flow and reducing lithospheric strength.[16] Initiation of back-arc basins typically occurs with relatively fast subduction rates that allow for sufficient slab pull to promote rollback over compression. Young, buoyant subducting slabs, with ages less than about 40-50 Ma, are particularly conducive to this process due to their lower density and tendency to steepen, enhancing hinge retreat and extension.[17] In contrast, slower subduction rates often result in compressive tectonics in the overriding plate, suppressing back-arc extension. A basic model for quantifying lithospheric extension in back-arc basins uses the stretching factor , defined as the ratio of initial to final horizontal length after extension, where indicates thinning. Crustal thickness reduces accordingly, with the final thickness given by where is the initial crustal thickness, leading to rifting and basin subsidence as increases. This pure-shear model provides insight into the geodynamic evolution from initial rifting to potential seafloor spreading.[18]Associated tectonic processes

The development and evolution of back-arc basins are intrinsically linked to subduction zone dynamics, where the angle of the subducting slab and the rate of plate convergence play pivotal roles in dictating upper-plate extension versus compression. Steep slab dips exceeding 50° facilitate rapid trench rollback, generating extensional forces that initiate and sustain back-arc rifting, as observed in systems like the New Hebrides where slab steepening promotes mantle flow and basin formation.[19] Conversely, shallow slab angles below 30° enhance coupling between plates, leading to compressional stresses that inhibit extension and favor forearc shortening.[19] These parameters also determine basin polarity: intraoceanic basins, formed in ocean-ocean subduction settings, typically feature steeper slabs and higher convergence rates, enabling full seafloor spreading, while retroarc basins in continent-ocean contexts exhibit shallower dips and moderate convergence rates, often restricting activity to rifting without widespread oceanic crust generation.[4] Interactions between back-arc extension and volcanic arcs occur via coupled mantle flow dynamics, creating feedback loops that influence arc magmatism. As back-arc spreading activates, upwelling in the extensional zone induces a broad convection cell that transports depleted mantle material from the back-arc toward the sub-arc region, diluting the fertility of the arc's mantle source and reducing melt production.[20] This process, lasting 10-15 million years, is amplified by accelerating trench retreat, which thins the overriding plate and alters corner flow patterns, often correlating with diminished or paused arc volcanism during peak extension phases.[20] Back-arc basins undergo dynamic transitions, progressing from rifting to spreading before potential closure through collisional tectonics. Initial rifting arises from localized extension in the overriding plate, evolving into seafloor spreading when spreading rates surpass 8 cm/yr, as higher convergence drives sufficient rollback to thin the lithosphere and generate new crust.[4] Subsequent closure via arc-continent collision inverts these basins, where underthrusting of continental margins activates fold-thrust belts, northward-verging thrusts, and rapid uplift (rates of 0.2-0.5 mm/yr), exhuming sediments from depths exceeding 2500 m in under 1 million years and partitioning strain across the arc system.[21] Globally, back-arc basins align with supercontinent cycles, emerging prominently during subduction-intensive phases that drive continental dispersal. Upper mantle-confined subduction produces short-lived basins (~500 km from the trench) via divergent tractions (0.5-1.5 × 10¹² N/m), while penetration into the lower mantle sustains broader flow cells and distal extension (3000-4000 km from the trench) over 40 million years, facilitating breakups like that of Pangea through enhanced tectonic tractions exceeding 10 times those of upper mantle processes.[22] Recent numerical models (as of 2025) further highlight the role of slab rollback and dehydration in controlling arc rifting and back-arc evolution.[23]Structural and Geological Features

Structural characteristics

Back-arc basins are characterized by elongated, asymmetric rift geometries that reflect the directional pull of subduction-driven extension behind volcanic arcs. These basins typically span lengths of 100–1000 km and widths of 50–200 km, with the narrower dimension oriented parallel to the arc trend.[24] The asymmetry arises from uneven extension, often manifesting as deeper floors on the side away from the arc and shallower marginal plateaus adjacent to the volcanic front. Central features include axial highs or lows along the rift axis, which accommodate focused extension and may evolve into spreading centers in mature basins. For instance, the Mariana Trough displays pronounced east-west asymmetry in bathymetry, with the spreading axis offset eastward.[24] Fault systems in back-arc basins are dominated by extensional structures that facilitate lithosphere stretching. Listric normal faults, dipping away from the arc at angles decreasing with depth, form rotational fault blocks and rollover anticlines, as observed in the Tyrrhenian Sea where both southeast- and northwest-dipping faults thin the crust. These are complemented by graben-horst architectures, creating alternating basins and uplifts that segment the rift floor, such as in the northern Okinawa Trough. Transform faults play a critical role in accommodating oblique extension, linking en echelon rift segments and ridge offsets, particularly in basins like the Manus Basin where they connect to propagating spreading centers.[24] The crustal structure beneath back-arc basins features significant thinning of continental or proto-oceanic crust to 4–7 km thickness, compared to normal oceanic crust of ~7 km, due to combined tectonic extension and magmatic addition.[24] Moho uplift accompanies this thinning, elevating the crust-mantle boundary to shallower depths of 10–15 km in places like the Kuril Basin. A distinctive high-velocity lower crustal layer, 2–5 km thick with P-wave velocities exceeding 6.8 km/s, is ubiquitous and attributed to mafic magmatic underplating from arc-related melts intruding the base of the crust.[24] This layer, evident in the Mariana Trough as a 3 km thick zone, enhances crustal strength and influences later seafloor spreading dynamics.[24] Geophysical signatures highlight the extensional nature of these basins. Free-air gravity anomalies show pronounced lows of -15 to -40 mGal over the rift axes, signaling isostatic response to thinned crust, as in the Aleutian and Grenada basins.[24] Seismic reflection and refraction profiles reveal layered crustal architectures, with detachment faults at 10–20 km depth facilitating large-scale extension; for example, in the Lau-Havre-Taupo system, profiles indicate low-angle detachments or rolling-hinge mechanisms underlying the rift. These features underscore the transition from continental rifting to oceanic spreading in back-arc settings.[24]Seafloor spreading dynamics

In mature back-arc basins, seafloor spreading occurs along central rift axes, generating new oceanic crust through symmetric or asymmetric extension at rates typically ranging from 1 to 10 cm/yr, though some segments reach up to 16 cm/yr. This process is primarily driven by slab pull forces associated with subducting plate rollback, which induces lithospheric extension behind the volcanic arc, often resulting in oblique or orthogonal spreading directions relative to the arc. Symmetric spreading, as observed in the West Philippine Basin at approximately 8.8 cm/yr from 60 to 35 Ma, produces balanced crustal accretion on both flanks, while asymmetric spreading, evident in the Mariana Trough at 4.3 cm/yr over the past 10 Ma, leads to wider development on one side due to differential extension influenced by proximity to the arc. Episodic ridge jumps and propagations further shape the spreading geometry, as seen in the South China Sea where ridge relocation altered the spreading direction from east-west to east-northeast-west-southwest during the Oligocene.[4] Evidence for these dynamics derives from geophysical surveys revealing symmetric magnetic stripe patterns flanking the spreading axes, which record reversals in Earth's geomagnetic field and allow calculation of half-spreading rates. For instance, in the Mariana Trough, linear magnetic anomalies oriented northwest-southeast enable determination of spreading history through age assignments to anomaly chronologies. Bathymetric profiles highlight axial ridges and abyssal hills formed by faulting and volcanism, with shallower depths (around 2-3 km) near active segments like the Lau Basin compared to extinct ones exceeding 5 km. Hydrothermal vents, such as those along the Eastern Lau Spreading Center, indicate robust magmatic heat sources sustaining circulation, often clustered at segment centers.[4][25] The resulting oceanic crust in back-arc basins is characteristically thin, averaging 4-7 km, thinner than typical mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) crust due to hydrous mantle melting and rapid extension. This includes a layered structure with sheeted dike complexes in the upper crust (Layer 2, ~1-2 km thick) and gabbroic intrusions forming a high-velocity lower crust (Layer 3, ~3-5 km, Vp 6.9-7.4 km/s) from underplated melts. Half-spreading rates (v) are quantified using magnetic anomalies via the formula: where is the distance between identified anomalies and is the time interval between their formation ages, as applied in the Banda Sea where spacing yields ~3 cm/yr.[4][25][26] Spreading variations reflect differences in subduction dynamics and mantle conditions, with slow-spreading segments (1-4 cm/yr, e.g., Kuril Basin) exhibiting focused magmatism and thicker crust, while fast-spreading ones (8-16 cm/yr, e.g., Lau Basin) show smoother bathymetry and thinner crust from distributed melt supply. Ultraslow segments (<2 cm/yr, as in parts of the Bransfield Strait) promote amagmatic extension, exposing serpentinized peridotite at the surface through faulting, which alters the lower crust with high-velocity layers from hydration rather than gabbroic intrusion. These differences influence overall basin asymmetry and longevity, with fast variants sustaining activity longer before potential extinction.[4][27]Magmatism and volcanism

Magmatism in back-arc basins primarily arises from partial melting of the mantle wedge, induced by fluids and melts derived from the subducting slab, which lower the solidus temperature and promote hydrous flux melting.[28] These processes generate a spectrum of magma compositions ranging from boninitic to tholeiitic basalts, with the former characterized by high SiO₂ (>52 wt%) and MgO (>8 wt%) contents due to melting of refractory, harzburgitic mantle sources previously depleted by earlier melt extraction.[29] Subduction influence is evident in trace element geochemistry, such as Nb/Zr ratios typically less than 1, reflecting the addition of slab-derived components that enrich incompatible elements like Ba, U, and Pb while depleting high-field-strength elements like Nb and Zr relative to mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) norms.[30] Volcanic manifestations in back-arc settings include submarine arc-like volcanoes and seamount chains proximal to the volcanic front, transitioning to axial volcanism at spreading centers further back, where magmas are emplaced along the structural framework of seafloor spreading.[31] These melts exhibit elevated H₂O contents, often 2-4 wt% in basaltic glasses, compared to MORB (∼0.2-0.5 wt%), enhancing melt productivity and contributing to the formation of extensive volcanic edifices and rift-related intrusions.[32] Over time, magmatic compositions evolve from early-stage boninites, linked to initial subduction initiation and intense slab fluid fluxing, to more mature MORB-like tholeiitic lavas as back-arc extension progresses, reflecting reduced slab influence and increased input from upwelling asthenosphere.[33] This transition typically occurs over several million years, with boninitic activity confined to the first 1-5 Ma of basin development. Geophysical evidence for these processes includes seismic tomography revealing low-velocity zones in the mantle wedge, indicative of hot, hydrous peridotite at depths of 50-150 km, where P-wave velocities are 2-5% lower than surrounding mantle due to partial melting and fluid presence.[34] Associated heat flow anomalies often exceed 100 mW/m² near active spreading centers, far exceeding the global oceanic average of ∼50 mW/m², driven by advective heat transport from rising melts and elevated mantle temperatures.[11]Sedimentation and Basin Evolution

Sedimentary processes

Sedimentary processes in back-arc basins are dominated by terrigenous inputs from adjacent volcanic arcs and continental margins, primarily through arc-derived volcaniclastics, hemipelagic oozes, and turbidites generated by shelf erosion. Volcaniclastics, including pyroclastic debris and epiclastic sediments, are transported via sediment gravity flows such as turbidity currents and debris flows, often sourced from subaerial or submarine arc volcanism. Hemipelagic oozes, composed of fine-grained biogenic and clayey materials, settle slowly from suspension, while turbidites form from density-driven flows that redistribute coarser shelf-derived sediments into deeper basin settings. Deposition patterns distinguish axial regimes along spreading centers, characterized by thinner volcaniclastic layers interbedded with pelagic sediments, from marginal zones near the arc, where thicker sequences accumulate due to slope instability and proximal inputs.[35][36] These processes create diverse depositional environments, including deep-marine fans and slope aprons in mature basins, where submarine fans build from axial turbidite channels and aprons form along faulted margins. In immature rifting stages, shallower settings may support localized reefal platforms on horst blocks, fostering carbonate buildup before subsidence deepens the basin. Basin subsidence rates typically range from 100 to 500 m/Myr during active extension, driving rapid accommodation space creation and influencing sediment distribution from axial highs to marginal lows. These environments reflect the interplay of tectonic subsidence and sediment supply, with deep-water settings prevailing as rifting progresses.[36][37] Rapid burial in these subsiding basins promotes distinct diagenetic features, including undercompaction of shales due to high sedimentation rates outpacing dewatering, leading to elevated pore pressures and fluid expulsion along faults. This process facilitates the formation of authigenic minerals such as clays (e.g., kaolinite, illite), zeolites, and pyrite through reactions with evolving pore fluids influenced by hydrothermal inputs. Undercompaction preserves porosity in fine-grained lithologies but enhances fracturing and fluid migration, altering basin permeability over time.[38][39] Modern analogs, such as the Okinawa Trough, exemplify these dynamics with high sedimentation rates up to 1 km/Myr in tectonically active segments, driven by intense fluvial inputs from Taiwan and frequent turbidite events that fill the basin axis. These rates underscore the role of proximal sediment sources in sustaining rapid infill during ongoing rifting.[40]Stratigraphic development and evolution

The stratigraphic development of back-arc basins typically progresses through distinct phases, beginning with syn-rift sedimentation dominated by clastic deposits derived from adjacent volcanic arcs and eroding footwalls. During this initial extensional phase, continental to shallow-marine alluvial, fluvial, and lacustrine facies accumulate in fault-controlled depocenters, as observed in the Early Miocene infill of the Pannonian Basin's subbasins like Kiskunhalas.[41] Following rift climax, the post-rift stage is characterized by thermal subsidence leading to the deposition of pelagic carbonates and fine-grained turbidites in deeper waters, with thicknesses reaching 2-3 km in areas like the Makó Trough.[41] Later modifications often include inversion unconformities, where tectonic compression erodes or truncates earlier strata, as seen in the Middle-Late Miocene unconformity (~11.6 Ma) across the central Pannonian Basin.[41] Evolutionary models describe back-arc basins transitioning from narrow rifts to wider oceanic-like domains through progressive crustal thinning and seafloor spreading, driven by subduction rollback. In the Pannonian system, extension migrated diachronously from northwest-southeast in the Early Miocene to east-west in the Late Miocene, achieving 150-270 km of total extension and thinning factors up to 2.2.[42] Subsequent closure phases may involve obduction or terrane accretion, incorporating ophiolite sequences onto continental margins; for instance, in the Banda Arc, short-lived (1-10 Ma) back-arc spreading centers inverted during collision, leading to ophiolite obduction 5-20 Ma after extension onset.[43] These sequences, such as those in the Newfoundland Caledonides, preserve remnants of intra-oceanic crust formed near sutures.[43] Stratigraphic evolution is modulated by eustasy, tectonics, and climate, which drive facies shifts from terrigenous clastics to biogenic carbonates. Eustatic sea-level fluctuations and tectonic subsidence control accommodation space, while climate influences sediment supply and carbonate production; in the Okinawa Trough, multi-episodic extension shifted depocenters southward, transitioning from Miocene clastics to Pliocene-Pleistocene deeper marine facies.[44] Inherited orogenic structures further dictate asymmetry in basin fill, as in the Pannonian Basin where pre-existing nappes reactivated during inversion.[42] Uplifted back-arc basins provide fossil records of Cenozoic to Mesozoic histories, reconstructed via backstripping to model subsidence curves and paleo-water depths. The method involves decompaction of stratigraphic layers using porosity-depth relations and Airy isostasy to isolate tectonic subsidence from sedimentary loading.[44] In the Rocas Verdes Basin of Patagonia, backstripping reveals Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous rift subsidence (150-145 Ma) followed by Cretaceous foreland transition and Paleogene uplift, with rates up to 900 m/Myr during accelerated phases.[45] Similarly, the Okinawa Trough's Neogene record shows episodic subsidence rates increasing from 8 m/Ma (23-5 Ma) to 340 m/Ma (post-0.7 Ma), reflecting diachronous rifting.[44]Global Examples

Major back-arc basins

Back-arc basins are classified as active or fossil based on their current tectonic status. Active basins exhibit ongoing rifting or seafloor spreading behind subduction zones, while fossil basins represent extinct spreading centers that have transitioned to passive margins or been incorporated into continental crust.[3] Examples of active basins include the Mariana Trough, which has been spreading since approximately 6 Ma, and the Lau Basin, ongoing since about 6 Ma.[25][46] Fossil basins, such as the Parece Vela Basin (extinct around 15 Ma after opening ~30 Ma) and the Tasman Sea (opened ~83 Ma, ceased ~52 Ma), no longer experience extension and often preserve magnetic anomalies indicative of past spreading.[3][47] Globally, back-arc basins are predominantly concentrated along the Pacific Ring of Fire, particularly in the western Pacific behind subduction zones like the Mariana, Tonga-Kermadec, and Vanuatu arcs, with examples including the Lau Basin near Fiji and the Mariana Trough. Other notable examples include the Aleutian Basin in the North Pacific, associated with the Aleutian arc, and the Japan Sea, a large fossil basin behind the Japanese arc that opened from ~30 Ma to ~15 Ma.[1] Fewer occur in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, such as the Scotia Sea in the South Atlantic and the Tyrrhenian Sea in the Mediterranean, reflecting limited subduction activity in those regions.[48][49] Prominent examples span a range of sizes, ages, and spreading dynamics. The following table summarizes key metrics for seven major back-arc basins, highlighting their locations, initiation ages, full spreading rates (where applicable), and status.| Basin | Location (approx. coordinates) | Age (initiation to cessation, Ma) | Spreading Rate (full, cm/yr) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mariana Trough | 12°–20°N, 142°–146°E | ~6–present | 2–5 | Active |

| Lau Basin | 15°–25°S, 173°E–179°W | ~6–present | 4–16 | Active |

| Okinawa Trough | 25°–30°N, 122°–130°E | ~10–present | 4–8 (half rates 2–4) | Active (rifting) |

| North Fiji Basin | 16°–22°S, 173°–180°E | ~10–present | 10–12 | Active |

| Tyrrhenian Sea | 38°–42°N, 10°–15°E | ~5–present | 4–6 | Active |

| Parece Vela Basin | 20°–25°N, 130°–140°E | ~30–15 | Historical (~5–10) | Fossil |

| Tasman Sea | 30°–45°S, 150°–170°E | ~83–52 | Historical (2–4) | Fossil |