Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Central nervous system disease

View on Wikipedia| Central nervous system disease | |

|---|---|

| |

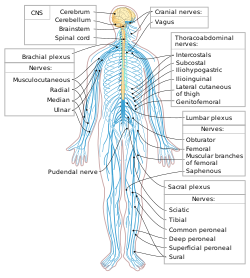

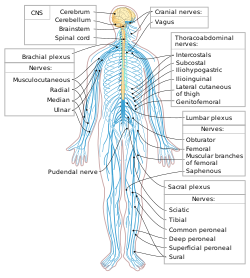

| Central nervous system in yellow (brain and spinal cord) | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, Neurology, Neurosurgery |

Central nervous system diseases or central nervous system disorders are a group of neurological disorders that affect the structure or function of the brain or spinal cord, which collectively form the central nervous system (CNS).[1][2][3] These disorders may be caused by such things as infection, injury, blood clots, age related degeneration, cancer, autoimmune disfunction, and birth defects. The symptoms vary widely, as do the treatments.

Central nervous system tumors are the most common forms of pediatric cancer.[citation needed] Brain tumors are the most frequent and have the highest mortality.[citation needed]

Some disorders, such as substance addiction, autism, and ADHD may be regarded as CNS disorders, though the classifications are not without dispute.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Every disease has different signs and symptoms. Some of them are persistent headache; pain in the face, back, arms, or legs; an inability to concentrate; loss of feeling; memory loss; loss of muscle strength; tremors; seizures; increased reflexes, spasticity, tics; paralysis; and slurred speech. One should seek medical attention if affected by these.[citation needed]

Causes

[edit]Trauma

[edit]Any type of traumatic brain injury (TBI) or injury done to the spinal cord can result in a wide spectrum of disabilities in a person. Depending on the section of the brain or spinal cord that experiences the trauma, the outcome may be anticipated.

Infections

[edit]Infectious diseases are transmitted in several ways. Some of these infections may affect the brain or spinal cord directly. Generally, an infection is a disease that is caused by the invasion of a microorganism or virus. Bacterial organisms are most often the cause, but animal parasites and fungi can also cause the infection.[4]

Degeneration

[edit]Degenerative spinal disorders involve a loss of function in the spine. Pressure on the spinal cord and nerves may be associated with herniation or disc displacement. Degenerative spinal disorders can be primarily caused by the natural aging process and wear and tear of the spine over time. However, other factors can accelerate or contribute to these conditions, such as injury, repetitive strain, genetics, and tumors.[5] Brain degeneration also causes central nervous system diseases (i.e. Alzheimer's, Lewy body dementia, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases).[citation needed] Raji et al 2010 reported correlation between obesity and brain degeneration and tissue loss.[6]

Structural defects

[edit]Common structural defects include birth defects,[7] anencephaly, and spina bifida. Children born with structural defects may have malformed limbs, heart problems, and facial abnormalities.

Defects in the formation of the cerebral cortex include microgyria, polymicrogyria, bilateral frontoparietal polymicrogyria, and pachygyria.

CNS Tumors

[edit]A tumor is an abnormal growth of body tissue. In the beginning, tumors can be noncancerous, but if they become malignant, they are cancerous. In general, they appear when there is a problem with cellular division. The exact causes of most central nervous system (CNS) tumors, including brain and spinal cord tumors, are still largely unknown. Over 90% of tumors arise sporadically with no apparent cause. However, some environmental and genetic factors are associated with an increased risk. Ionizing radiation is the only well-established environmental risk factor, accounting for only a few percent of incident CNS tumors. A few percent of CNS tumor cases are owing to specific inherited syndromes. Nonionizing radiation, pesticides, occupational exposures, infection, prior head trauma, and diet are other factors of CNS tumors under investigation.[8] Problems with the body's immune system can lead to tumors.

Autoimmune disorders

[edit]An autoimmune disorder is a condition where in the immune system attacks and destroys healthy body tissue. This is caused by a loss of tolerance to proteins in the body, resulting in immune cells recognising these as 'foreign' and directing an immune response against them. However, the scientific community is still exploring answers to exactly what causes over 80 autoimmune diseases. Certain risk factors are believed to impact immune tolerance and may lead to the development of autoimmune conditions: sex, genetics, obesity, smoking, exposure to toxic agents, and infection.[9]

Stroke

[edit]A stroke is an interruption of the blood supply to the brain. Approximately every 40 seconds, someone in the US has a stroke.[10] This can happen when a blood vessel is blocked by a blood clot or when a blood vessel ruptures, causing blood to leak to the brain. If the brain cannot get enough oxygen and blood, brain cells can die, leading to permanent damage.

Functions

[edit]Spinal cord

[edit]The spinal cord transmits sensory reception from the peripheral nervous system.[11] It also conducts motor information to the body's skeletal muscles, cardiac muscles, smooth muscles, and glands. There are 31 pairs of spinal nerves along the spinal cord, all of which consist of both sensory and motor neurons.[11] The spinal cord is protected by vertebrae and connects the peripheral nervous system to the brain, and it acts as a "minor" coordinating center.

Brain

[edit]The brain serves as the organic basis of cognition and exerts centralized control over the other organs of the body. The brain is protected by the skull; however, if the brain is damaged, significant impairments in cognition and physiological function or death may occur.

Diagnosis

[edit]Types of CNS disorders

[edit]Addiction

[edit]Addiction is a disorder of the brain's reward system which arises through transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms and occurs over time from chronically high levels of exposure to an addictive stimulus (e.g., morphine, cocaine, sexual intercourse, gambling, etc.).[13][14][15][16]

Arachnoid cysts

[edit]Arachnoid cysts are cerebrospinal fluid covered by arachnoidal cells that may develop on the brain or spinal cord.[17] They are a congenital disorder, and in some cases may not show symptoms. However, if there is a large cyst, symptoms may include headache, seizures, ataxia (lack of muscle control), hemiparesis, and several others. Macrocephaly and ADHD are common among children, while presenile dementia, hydrocephalus (an abnormality of the dynamics of the cerebrospinal fluid), and urinary incontinence are symptoms for elderly patients (65 and older).

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

[edit]ADHD is an organic disorder of the nervous system.[18][19][20][21] ADHD, which in severe cases can be debilitating,[22] has symptoms thought to be caused by structural as well as biochemical imbalances in the brain; in particular, low levels of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine,[23] which are responsible for controlling and maintaining attention and movement. Many people with ADHD continue to have symptoms well into adulthood.[24] Also of note is an increased risk of the development of Dementia with Lewy bodies, or (DLB), and a direct genetic association of Attention deficit disorder to Parkinson's disease[25][26] two progressive, and serious, neurological diseases whose symptoms often occur in people over age 65.[24][27][28][29]

Autism

[edit]Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that is characterized by repetitive patterns of behavior and persistent deficits in social interaction and communication.[12]

Brain tumors

[edit]Tumors of the central nervous system constitute around 2% of all cancer in the United States.[30]

Catalepsy

[edit]Catalepsy is a nervous disorder characterized by immobility and muscular rigidity, along with a decreased sensitivity to pain. Catalepsy is considered a symptom of serious diseases of the nervous system (e.g., Parkinson's disease, Epilepsy, etc.) rather than a disease by itself. Cataleptic fits can range in duration from several minutes to weeks. Catalepsy often responds to Benzodiazepines (e.g., Lorazepam) in pill and I.V. form.[31]

Encephalitis

[edit]Encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain. It is usually caused by a foreign substance or a viral infection. Symptoms of this disease include headache, neck pain, drowsiness, nausea, and fever. If caused by the West Nile virus,[32] it may be lethal to humans, as well as birds and horses.

Epilepsy and seizures

[edit]Epilepsy is an unpredictable, serious, and potentially fatal disorder of the nervous system, thought to be the result of faulty electrical activity in the brain. Epileptic seizures result from abnormal, excessive, or hypersynchronous neuronal activity in the brain. About 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy, and nearly 80% of epilepsy occurs in developing countries. Epilepsy becomes more common as people age. Onset of new cases occurs most frequently in infants and the elderly. Epileptic seizures may occur in recovering patients as a consequence of brain surgery.[33]

Infection

[edit]A number of different pathogens (i.e., certain viruses, bacteria, protozoa, fungi, and prions) can cause infections that adversely affect the brain or spinal cord.

Meningitis

[edit]Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges (membranes) of the brain and spinal cord. It is most often caused by a bacterial or viral infection. Fever, vomiting, and a stiff neck are all symptoms of meningitis.

Migraine

[edit]A chronic, often debilitating neurological disorder characterized by recurrent moderate to severe headaches, often in association with a number of autonomic nervous system symptoms.

Multiple sclerosis

[edit]Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, inflammatory demyelinating disease, meaning that the myelin sheath of neurons is damaged. Symptoms of MS include visual and sensation problems, muscle weakness, numbness and tingling all over, muscle spasms, poor coordination, and depression. Also, patients with MS have reported extreme fatigue and dizziness, tremors, and bladder leakage.

Myelopathy

[edit]Myelopathy is an injury to the spinal cord due to severe compression that may result from trauma, congenital stenosis, degenerative disease or disc herniation. The spinal cord is a group of nerves housed inside the spine that runs almost its entire length.

Tourette's

[edit]Tourette's syndrome is an inherited neurological disorder. Early onset may be during childhood, and it is characterized by physical and verbal tics. Tourette's often also includes symptoms of both OCD and ADHD indicating a link between the three disorders. The exact cause of Tourette's, other than genetic factors, is unknown.

Neurodegenerative disorders

[edit]Alzheimer's

[edit]Alzheimer's is a neurodegenerative disease typically found in people over the age of 65 years. Worldwide, approximately 24 million people have dementia; 60% of these cases are due to Alzheimer's. The ultimate cause is unknown. The clinical sign of Alzheimer's is progressive cognition deterioration.

Huntington's disease

[edit]Huntington's disease is a degenerative neurological disorder that is inherited. Degeneration of neuronal cells occurs throughout the brain, especially in the striatum. There is a progressive decline that results in abnormal movements.[34] Statistics show that Huntington's disease may affect 10 per 100,000 people of Western European descent.

Lewy body dementia

[edit]Lewy body dementia is an umbrella term for two similar and common subtypes of dementia:[35] dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD).[36][37][38][39] Both are characterized by changes in thinking, movement, behavior, and mood.[35] The two conditions have similar features and may have similar causes, and are believed to belong on a spectrum of Lewy body disease[36] that includes Parkinson's disease.[39]

Parkinson's

[edit]Parkinson's disease, or PD, is a progressive illness of the nervous system. Caused by the death of dopamine-producing brain cells that affect motor skills and speech. Symptoms may include bradykinesia (slow physical movement), muscle rigidity, and tremors. Behavior, thinking, sensation disorders, and the sometimes co-morbid skin condition Seborrheic dermatitis are just some of PD's numerous nonmotor symptoms. Parkinson's disease, Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and Bi-polar disorder, all appear to have some connection to one another, as all three nervous system disorders involve lower than normal levels of the brain chemical dopamine (In ADHD, Parkinson's, and the depressive phase of Bi-polar disorder.) or too much dopamine (in Mania or Manic states of Bi-polar disorder) in different areas of the brain:[40][41][42]

Treatments

[edit]There are a wide range of treatments for central nervous system diseases. These can range from surgery to neural rehabilitation or prescribed medications.[citation needed] Neurotherapy, like many other treatments, relies on knowledge from traditional medicine and uses a scientific approach and evidence-based practice. Neurotherapy is a medical treatment that involves the targeted systemic administration of an energetic stimulus or chemical agent to a specific neurological area. However, some neuromodulation techniques are still considered alternative medicine (medical procedures that are not easily integrated into the mainstream healthcare model) due to their novelty and lack of supporting evidence.[43] The wide range of non-invasive neurotherapy methods can be divided into four groups depending on the use of energy stimulation: acoustic energy, electric energy, electromagnetic radiation, and magnetic energy.[44] The most valued pharmacological companies worldwide whose leading products are in CNS Care include CSPC Pharma (Hong Kong), Biogen (United States), UCB (Belgium) and Otsuka (Japan) who are active in treatment areas like MS, Alzheimers, Epilepsy and Psychiatry.[45]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Nervous System Diseases". Healthinsite.gov.au. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ Central Nervous System Diseases at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ a b Cacabelos R, Torrellas C, Fernández-Novoa L, López-Muñoz F (2016). "Histamine and Immune Biomarkers in CNS Disorders". Mediators Inflamm. 2016 1924603. doi:10.1155/2016/1924603. PMC 4846752. PMID 27190492.

- ^ Neurological Infections. (2025) University of Maryland Medical Center. https://www.umms.org/ummc/health-services/neurology/services/neurological-infections Retrieved 2025-08-17

- ^ Degenerative spine conditions. (2025) UC Davis Spine Center. https://health.ucdavis.edu/spine/specialties/degenerative.html#:~:text=Degenerative%20spine%20conditions%20involve%20the,Slipped%20or%20herniated%20discs Retrieved 2025-08-17

- ^ Raji, Cyrus A.; Ho, April J.; Parikshak, Neelroop N.; Becker, James T.; Lopez, Oscar L.; Kuller, Lewis H.; Hua, Xue; Leow, Alex D.; Toga, Arthur W.; Thompson, Paul M. (March 2010). "Brain structure and obesity". Human Brain Mapping. 31 (3): 353–364. doi:10.1002/hbm.20870. PMC 2826530. PMID 19662657.

- ^ "Birth Defects". Kidshealth.org. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ McKean-Cowdin, R.; Barrington-Trimis, J.; Preston-Martin, S. (2014). "Tumors, Central Nervous System; Epidemiology of". Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. pp. 552–560. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385157-4.00600-X. ISBN 978-0-12-385158-1.

- ^ 7 Risk Factors for Autoimmune Disease. (2025) Global Autoimmune Institute. https://www.autoimmuneinstitute.org/7-ad-risk-factors/ Retrieved 2025-08-17

- ^ "Stroke". Hearthealthywomen.org. Archived from the original on 2013-06-24. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ a b "Organization of the Nervous System". Users.rcn.com. Archived from the original on 2010-01-03. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ a b Lipton JO, Sahin M (October 2014). "The neurology of mTOR". Neuron. 84 (2): 275–291. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.034. PMC 4223653. PMID 25374355.

- ^ Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 15 (4): 431–443. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

- ^ Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–437. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822.

- ^ Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–1122. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

- ^ Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). Longo DL (ed.). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". N. Engl. J. Med. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

- ^ "How the Brain Works". Arachnoidcyst.org. Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ "Brain Studies Show ADHD Is Real Disease - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ "ADHD Study: General Information". Genome.gov. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ Christian Nordqvist (2010-09-30). "MNT - ADHD Is A Genetic Neurodevelopmental Disorder, Scientists Reveal". Medical News Today. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ "Social Security Disability SSI and ADHD, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". Ssdrc.com. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ "112.00-MentalDisorders-Childhood". Ssa.gov. 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ "What Is ADHD? Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: What You Need to Know". Webmd.com. 2008-09-18. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ a b "Adult ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder)". MayoClinic.com. 2013-03-07. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ "Parkinsonism, ADHD: Common Genetic Link?". 2014-07-04.

- ^ Golimstok A, Rojas JI, Romano M, Zurru MC, Doctorovich D, Cristiano E (January 2011). "Previous adult attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder symptoms and risk of dementia with Lewy bodies: a case-control study". Eur J Neurol. 18 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03064.x. PMID 20491888.

- Lay summary in: "Adult ADHD significantly increases risk of common form of dementia, study finds". Science Daily (Press release). February 6, 2011.

- ^ "Dementia With Lewy Bodies Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". Ninds.nih.gov. 2013-06-06. Archived from the original on 2016-08-09. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ Puschmann A, Bhidayasiri R, Weiner WJ (January 2012). "Synucleinopathies from bench to bedside". Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 18 (Suppl 1): S24–7. doi:10.1016/S1353-8020(11)70010-4. PMID 22166445.

- ^ Hansen FH, Skjørringe T, Yasmeen S, Arends NV, Sahai MA, Erreger K, et al. (July 2014). "Missense dopamine transporter mutations associate with adult parkinsonism and ADHD". J Clin Invest. 124 (7): 3107–20. doi:10.1172/JCI73778. PMC 4071392. PMID 24911152.

- ^ Ostrom QT, et al. (October 2019). "CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016". Neuro-Oncology. 21 (5): v1 – v100. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noz150. PMC 6823730. PMID 31675094.

- ^ "What is Catalepsy? (with pictures)". wiseGEEK. 7 August 2023.

- ^ "West Nile Virus". Medicinenet.com. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ "How Serious Are Seizures?". Epilepsy.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ "Huntington's Disease". Hdsa.org. Archived from the original on 2013-11-01. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ^ a b Walker Z, Possin KL, Boeve BF, Aarsland D (October 2015). "Lewy body dementias". Lancet (Review). 386 (10004): 1683–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00462-6. PMC 5792067. PMID 26595642.

- ^ a b Gomperts SN (April 2016). "Lewy Body Dementias: Dementia With Lewy Bodies and Parkinson Disease Dementia". Continuum (Minneap Minn). 22 (2 Dementia): 435–63. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000309. PMC 5390937. PMID 27042903.

- ^ Pezzoli S, Cagnin A, Bandmann O, Venneri A (July 2017). "Structural and Functional Neuroimaging of Visual Hallucinations in Lewy Body Disease: A Systematic Literature Review". Brain Sci. 7 (12): 84. doi:10.3390/brainsci7070084. PMC 5532597. PMID 28714891.

- ^ Galasko D (May 2017). "Lewy Body Disorders". Neurol Clin. 35 (2): 325–38. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2017.01.004. PMC 5912679. PMID 28410662.

- ^ a b Kon T, Tomiyama M, Wakabayashi K (February 2020). "Neuropathology of Lewy body disease: Clinicopathological crosstalk between typical and atypical cases". Neuropathology. 40 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1111/neup.12597. PMID 31498507.

- ^ Engmann B (2011). "Bipolar affective disorder and Parkinson's disease". Case Rep Med. 2011 154165. doi:10.1155/2011/154165. PMC 3226531. PMID 22162696.

- ^ Walitza, S.; Melfsen, S.; Herhaus, G.; Scheuerpflug, P.; Warnke, A.; Müller, T.; Lange, K. W.; Gerlach, M. (2007). "Association of Parkinson's disease with symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in childhood". Neuropsychiatric Disorders an Integrative Approach. Journal of Neural Transmission. Supplementum. pp. 311–315. doi:10.1007/978-3-211-73574-9_38. ISBN 978-3-211-73573-2. PMID 17982908.

- ^ "Movement disorders in young people related to ADHD". ScienceDaily (Press release). University of Copenhagen – The Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences. 3 July 2014.

- ^ Eskinazi, Daniel; Mindes, Janet (8 January 2001). "Alternative Medicine: Definition, Scope and Challenges". Asia-Pacific Biotech News. 05 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1142/S0219030301001793.

- ^ Val Danilov, Igor (29 November 2024). "The Origin of Natural Neurostimulation: A Narrative Review of Noninvasive Brain Stimulation Techniques". OBM Neurobiology. 08 (4): 1–23. doi:10.21926/obm.neurobiol.2404260.

- ^ "Top Global Pharmaceutical Company Report" (PDF). The Pharma 1000. November 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

External links

[edit]Central nervous system disease

View on GrokipediaAnatomy and Physiology

The Brain

The human brain is the largest and most complex organ in the central nervous system, serving as the primary center for processing sensory information, initiating motor responses, and enabling higher cognitive functions such as reasoning and memory. Weighing approximately 1.4 kg in adults, it constitutes about 2% of total body weight yet consumes around 20% of the body's oxygen and energy at rest, underscoring its high metabolic demands. The brain contains roughly 86 billion neurons, the fundamental signaling units, along with an equal number of non-neuronal glial cells that provide structural and metabolic support. This intricate network is protected by the skull and meninges, with cerebrospinal fluid cushioning it against mechanical stress. Structurally, the brain is divided into three main regions: the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem. The cerebrum, comprising the largest portion, is subdivided into four lobes—frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital—each with specialized roles. The frontal lobe governs executive functions like decision-making, problem-solving, and voluntary motor control through the primary motor cortex. The parietal lobe integrates sensory input, particularly touch and spatial awareness, via the somatosensory cortex. The temporal lobe processes auditory information and contributes to memory formation in structures like the hippocampus, while the occipital lobe is dedicated to visual processing. The cerebellum, located at the rear base, coordinates fine motor movements, maintains balance, and refines posture through its Purkinje and granule cells. The brainstem, connecting the brain to the spinal cord, regulates vital autonomic functions including respiration, heart rate, and blood pressure via nuclei in the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. At the cellular level, the brain consists primarily of neurons and glial cells. Neurons transmit electrical and chemical signals across synapses, enabling rapid communication essential for all brain functions. Glial cells outnumber neurons and include astrocytes, which maintain the extracellular environment, regulate ion balance, and form the supportive framework for neurons; oligodendrocytes, which produce myelin sheaths to insulate axons and speed signal conduction in the central nervous system; and microglia, the resident immune cells that monitor for injury and clear debris. These components are safeguarded by the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a selective semipermeable interface formed by endothelial cells in brain capillaries, joined by tight junctions, along with astrocyte end-feet and pericytes. The BBB restricts the passage of toxins, pathogens, and large molecules from the bloodstream while permitting essential nutrients like glucose and oxygen, thus maintaining the brain's stable internal milieu. Functionally, the brain integrates sensory inputs from the periphery to form coherent perceptions, plans and executes motor actions through hierarchical pathways, supports advanced cognition including language and emotion via cortical networks, and oversees autonomic regulation of homeostasis. For instance, thalamocortical circuits relay and process sensory data, while the basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex modulate voluntary movements and inhibitory control. The brainstem and hypothalamus further coordinate involuntary processes like circadian rhythms and stress responses. Regional blood flow, averaging 50-60 mL per 100 g of tissue per minute, meets the brain's oxygen demand of about 3.5 mL per 100 g per minute, ensuring uninterrupted function despite its vulnerability to even brief interruptions.The Spinal Cord

The spinal cord is a cylindrical structure of nervous tissue that extends from the brainstem through the vertebral canal, measuring approximately 45 cm in length in adult males and 43 cm in females.[8] It is divided into 31 segments, consisting of 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 1 coccygeal segment, each corresponding to paired spinal nerves that exit the cord.[9] In cross-section, the spinal cord features an inner core of gray matter arranged in an H-shape, surrounded by outer white matter; the gray matter includes dorsal horns primarily for sensory neuron integration, ventral horns for motor neuron cell bodies, and lateral horns (in thoracic and upper lumbar segments) for autonomic preganglionic neurons.[10] The white matter comprises ascending tracts, such as the spinothalamic tract for pain and temperature sensation, and descending tracts, like the corticospinal tract for voluntary motor control, facilitating bidirectional communication along myelinated axons.[11] The spinal cord exhibits variations in diameter, widest at the cervical enlargement (around 13-14 mm transversely at C4-C5) to accommodate nerves innervating the upper limbs, narrowing to about 6-7 mm in the thoracic region, and widening again at the lumbar enlargement for lower limb innervation.[12] It is enveloped by three protective meninges—the outermost dura mater, middle arachnoid mater, and innermost pia mater—with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulating in the subarachnoid space between the arachnoid and pia to cushion and nourish the cord.[13] Additional safeguards include the bony vertebral column encasing the cord and the ligamentum flavum, a elastic ligament connecting adjacent vertebral laminae to maintain spinal stability and protect against compression.[14] Functionally, the spinal cord serves as a vital relay for sensory and motor signals between the periphery and the brain, transmitting ascending sensory inputs via dorsal root ganglia to higher centers and descending motor commands from the brainstem and cortex to effector muscles.[15] It also mediates local spinal reflexes, such as the knee-jerk (patellar) reflex, which operates through a monosynaptic arc involving sensory afferents from muscle spindles directly synapsing with motor efferents in the ventral horn for rapid, involuntary responses.[16] Furthermore, the cord coordinates autonomic functions, with sympathetic preganglionic outflows originating from lateral horn neurons in thoracic and lumbar segments (T1-L2) to regulate visceral activities like heart rate and vasoconstriction, while parasympathetic outflows emerge from sacral segments (S2-S4) for functions such as bladder control and digestion.[9] Overall, these roles underscore the spinal cord's integration under brain oversight for coordinated neural processing.[15]Pathophysiology

Mechanisms of CNS Injury and Dysfunction

Central nervous system (CNS) injuries often begin with primary mechanisms that directly damage neurons and supporting cells. Excitotoxicity arises from excessive glutamate release, leading to overstimulation of ionotropic receptors such as NMDA and AMPA, which causes massive calcium influx into neurons and triggers cell death pathways.[17] Ischemia, characterized by oxygen deprivation through hypoxia, impairs ATP production and exacerbates excitotoxicity by disrupting ionic gradients across neuronal membranes.[18] Concurrently, oxidative stress generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage lipids, proteins, and DNA in cellular components, further compromising neuronal integrity.[19] Secondary injury cascades amplify initial damage through delayed processes that evolve over hours to days. Inflammation involves microglial activation and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1, which recruit immune cells and perpetuate tissue destruction.[20] Cell death in this phase proceeds via apoptosis, an energy-dependent programmed pathway involving caspase activation, or necrosis, a passive process marked by membrane rupture and inflammation; mitochondrial dysfunction often dictates the balance between these modes.[20] Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) allows influx of serum proteins and immune mediators, contributing to vasogenic edema and further neuronal toxicity.[21] Distinct structural and functional changes characterize CNS responses to injury. Wallerian degeneration entails the distal axonal segment breaking down and fragmenting following axotomy, with early pathological changes detectable as soon as two days post-injury via imaging and histology.[22] Loss of synaptic plasticity impairs adaptive rewiring, as inhibitory extracellular matrix components prevent new synapse formation in the injured CNS.[23] Adult neurogenesis is severely limited outside specific niches, such as the hippocampal subgranular zone, restricting endogenous repair capacity after widespread CNS damage.[24] These secondary processes typically peak between 24 and 72 hours after the initial insult, providing a therapeutic window for intervention. Aquaporin-4 (AQP4), the predominant water channel in astrocytic endfeet, facilitates edema formation by mediating water influx across the BBB, exacerbating intracranial pressure during this critical period.[25]Common Pathological Processes

Central nervous system (CNS) diseases often involve degenerative processes characterized by the misfolding of proteins, which leads to the formation of toxic aggregates that disrupt cellular function. Protein misfolding occurs when proteins adopt abnormal conformations, promoting self-assembly into insoluble fibrils or plaques that impair proteostasis and trigger cellular stress responses. For instance, the principles of amyloid-beta aggregation involve the hydrophobic interactions and beta-sheet formation of peptides, resulting in extracellular deposits that interfere with synaptic transmission and neuronal viability.[26] Similarly, tau hyperphosphorylation at specific serine and threonine residues destabilizes microtubules, promoting tau detachment from them and subsequent aggregation into neurofibrillary tangles that compromise axonal transport.[27] Mitochondrial dysfunction exacerbates these degenerative events by causing energy failure through impaired oxidative phosphorylation and increased reactive oxygen species production, which accelerates protein misfolding and neuronal apoptosis.[28] Genetic factors, such as polymorphisms in the APOE gene (particularly the ε4 allele), predispose individuals to enhanced protein aggregation and degeneration by altering lipid metabolism and amyloid clearance efficiency in the CNS.[29] Inflammatory and autoimmune pathological processes in the CNS are driven by the activation of resident immune cells like microglia and astrocytes, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory mediators that amplify tissue damage. Cytokine-mediated damage involves the overproduction of interleukins (e.g., IL-1β and IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which induce excitotoxicity and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, allowing further immune infiltration.[30] Complement activation contributes to this cascade by opsonizing damaged neurons for phagocytosis and generating anaphylatoxins that recruit inflammatory cells, thereby exacerbating synaptic loss.[31] T-cell infiltration across the compromised BBB occurs via adhesion molecule upregulation on endothelial cells, enabling adaptive immune responses that, in chronic states, promote demyelination and axonal injury.[32] Chronic neuroinflammation plays a pivotal role in disease progression, as sustained microglial activation leads to persistent cytokine release and oxidative stress, culminating in progressive neuronal loss and circuit dysfunction.[33] Vascular pathology in CNS diseases arises from endothelial dysfunction, which impairs the integrity of cerebral blood vessels and predisposes to ischemic or hemorrhagic events. Endothelial cells normally regulate vascular tone and barrier function through nitric oxide production, but dysfunction—often triggered by oxidative stress or inflammation—results in reduced vasodilation and increased permeability, facilitating leukocyte adhesion and plaque formation.[34] Thrombosis formation follows Virchow's triad, encompassing blood stasis (e.g., from hypoperfusion), hypercoagulability (due to elevated pro-thrombotic factors like fibrinogen), and vessel wall injury (from shear stress or inflammatory damage), collectively promoting clot occlusion in cerebral arteries.[35] Neoplastic processes in the CNS involve uncontrolled cellular proliferation driven by dysregulated signaling pathways that bypass normal growth controls, leading to tumor expansion within the confined cranial space. This proliferation is supported by aberrant activation of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressors, resulting in rapid cell division and genomic instability.[36] Angiogenesis is a critical component, mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secreted by hypoxic tumor cells, which stimulates endothelial sprouting, vessel permeability, and new capillary formation to sustain nutrient supply and tumor growth.[37]Signs and Symptoms

Neurological Deficits

Neurological deficits in central nervous system (CNS) diseases encompass a range of cognitive, behavioral, and autonomic impairments that arise from disruptions in brain function, often manifesting as higher-order symptoms rather than primary sensory or motor issues. These deficits can significantly impact daily functioning and quality of life, with cognitive impairments being particularly prevalent across various CNS pathologies such as traumatic brain injury, stroke, and neurodegenerative conditions.[38] For instance, memory loss is a common feature, categorized into anterograde amnesia, where individuals struggle to form new memories after the onset of the condition, and retrograde amnesia, involving the inability to recall events from before the injury or disease.[39] Executive dysfunction, another key cognitive impairment, stems from prefrontal cortex involvement and affects planning, decision-making, and cognitive flexibility, leading to difficulties in organizing tasks and adapting to changing environments.[40] Language disturbances, such as aphasia, further illustrate cognitive deficits; Broca's aphasia, resulting from damage to the frontal lobe, impairs expressive speech while preserving comprehension, whereas Wernicke's aphasia, linked to temporal lobe lesions, disrupts receptive language understanding, often producing fluent but nonsensical speech.[41] Behavioral changes in CNS diseases frequently involve alterations in mood and perception due to limbic system and temporal lobe dysfunction. Mood disorders like depression and anxiety are associated with limbic involvement, where structures such as the amygdala and hippocampus regulate emotional processing, leading to persistent low mood, heightened fear responses, or irritability.[42] Psychosis, including hallucinations, can emerge from temporal lobe pathology, manifesting as auditory or visual perceptual disturbances that mimic primary psychiatric conditions but are secondary to neurological insult.[43] Seizures, sudden uncontrolled bursts of electrical activity in the brain leading to temporary changes in movement, sensation, or consciousness, are also common in CNS diseases, particularly those involving trauma, infections, strokes, or tumors.[44] These behavioral symptoms often exacerbate cognitive decline and require integrated management to address both neural and psychological aspects. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) serves as a standardized tool for assessing levels of consciousness in CNS disease, with scores ranging from 3 (deep unconsciousness) to 15 (fully alert), based on three components: eye-opening response (1-4 points), verbal response (1-5 points), and motor response (1-6 points).[45] In the context of aging-related CNS changes, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) represents a transitional state, affecting approximately 15-20% of adults over age 65 and acting as a precursor to dementia in 10-15% of cases annually.[46] Autonomic symptoms, including altered consciousness and sleep disturbances, commonly accompany these deficits; for example, disrupted sleep architecture due to CNS lesions can lead to insomnia or hypersomnolence, further impairing cognitive recovery.[47]Sensory and Motor Impairments

Sensory and motor impairments represent core manifestations of central nervous system (CNS) diseases, arising from disruptions in neural pathways that transmit signals for perception and movement. These deficits often stem from lesions in the brain, brainstem, or spinal cord, leading to altered sensory processing and impaired motor execution. For instance, damage to ascending sensory tracts can result in loss of sensation, while descending motor pathways may cause weakness or uncoordinated movements. Headaches, often severe and persistent, are frequent in CNS diseases associated with vascular disruptions, increased intracranial pressure, or inflammation, serving as an early warning sign.[4] Motor deficits in CNS diseases commonly include paresis or paralysis, distinguished by the level of the lesion in the motor neuron pathway. Upper motor neuron (UMN) lesions, typically from cortical or spinal cord involvement, produce spasticity, hyperreflexia, and a positive Babinski sign due to loss of inhibitory control from higher centers. In contrast, lower motor neuron (LMN) lesions, such as those in anterior horn cells, lead to flaccid paralysis, muscle atrophy, fasciculations, and hyporeflexia from direct denervation. Cerebellar ataxia manifests as intention tremor, dysmetria, and broad-based gait instability, reflecting impaired coordination and error correction in movement planning. Gait abnormalities, like the hemiplegic shuffle seen in stroke-related hemiparesis, involve circumduction of the leg and reduced arm swing on the affected side, compensating for extensor spasticity. Sensory losses encompass a range of disturbances in perception, often mapped to specific dermatomes that delineate segmental sensory innervation from spinal roots. Hypoesthesia or anesthesia occurs with damage to dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathways, impairing fine touch and vibration sense, while spinothalamic tract involvement leads to loss of pain and temperature sensation. Paresthesia, described as tingling or "pins and needles," arises from irritable lesions in sensory pathways, and proprioception deficits—loss of joint position sense—can cause sensory ataxia, where patients rely on visual cues for balance, exacerbated in the dark. Pain syndromes in CNS disease include neuropathic pain from central sensitization, differing from nociceptive pain by its burning, lancinating quality and poor response to opioids; thalamic pain syndrome exemplifies this post-stroke. Reflex changes provide diagnostic clues: UMN lesions evoke hyperreflexia and clonus due to uninhibited stretch reflexes, whereas LMN lesions diminish or abolish reflexes. The ASIA Impairment Scale assesses spinal cord injury severity, grading from A (complete, no sensory or motor function below the lesion) to E (normal), guiding prognosis for motor and sensory recovery. Cranial nerve involvements contribute to these impairments, such as facial droop from lower motor neuron seventh nerve palsy in Bell's phenomenon or brainstem strokes, and dysphagia from ninth and tenth nerve dysfunction in medullary lesions, increasing aspiration risk. In advanced CNS diseases, sensory-motor impairments may overlap with cognitive declines, complicating rehabilitation.Causes

Infectious Causes

Infectious causes of central nervous system (CNS) disease encompass a range of pathogens that invade the brain and spinal cord, leading to inflammation, tissue damage, and neurological dysfunction. These infections often result from hematogenous spread, direct extension from adjacent sites, or reactivation of latent organisms, particularly in vulnerable populations such as the immunocompromised. Bacterial, viral, fungal, parasitic, and prion agents each contribute uniquely to the global burden of CNS disease, with meningitis alone accounting for an estimated 2.51 million incident cases worldwide in 2019.[48] Bacterial InfectionsBacterial pathogens are a leading cause of acute CNS infections, with meningitis being the most prevalent manifestation. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis are primary etiologic agents, responsible for the majority of community-acquired cases in adults and children, respectively.[49] Symptoms typically include fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status, though the classic triad is present in only about 44% of adults.[50] Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis in bacterial meningitis reveals elevated white blood cell counts (often >1,000 cells/µL, predominantly neutrophils), increased protein levels (>200 mg/dL), and decreased glucose (<40 mg/dL), aiding in differentiation from viral causes.[51] The introduction of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate vaccines in the late 1980s led to a dramatic decline in invasive Hib disease, reducing U.S. incidence by over 99% by the early 2000s.[52] Brain abscesses represent another serious bacterial complication, often forming localized collections of pus within brain parenchyma due to contiguous spread from sinusitis, otitis, or hematogenous dissemination. Staphylococcus aureus is a common culprit, particularly in postoperative or trauma-related cases, contributing to focal neurological deficits and high mortality if untreated.[53] Viral Infections

Viral pathogens primarily cause encephalitis, an inflammation of brain parenchyma that can lead to seizures, cognitive impairment, and coma. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is the most frequent cause of sporadic encephalitis in adults, with a predilection for the temporal and frontal lobes, resulting from reactivation of latent virus in trigeminal ganglia.[54] In individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, opportunistic CNS infections can exacerbate viral effects. Other Infectious Agents

Fungal infections of the CNS, though less common, pose significant risks to immunocompromised hosts, such as those with HIV/AIDS or undergoing organ transplantation. Cryptococcus neoformans is the predominant species, causing meningitis through inhalation and subsequent dissemination, with subacute symptoms like headache and fever; it accounts for up to 15% of AIDS-related deaths globally.[55] Parasitic infections include neurocysticercosis, endemic in regions with poor sanitation, where larval cysts of Taenia solium (the pork tapeworm) lodge in the brain, provoking seizures in up to 80% of cases—the leading cause of acquired epilepsy in endemic areas.[56] In individuals with HIV infection, toxoplasmosis, caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, is the most common mass lesion in untreated or advanced HIV/AIDS, often presenting as multiple ring-enhancing lesions on imaging due to reactivation of latent cysts.[57] Prion diseases, such as sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), represent transmissible protein misfolding disorders that rapidly destroy neurons, leading to progressive dementia, myoclonus, and death within months of onset; CJD has an incidence of about 1-2 cases per million annually and is invariably fatal.[58] These infections trigger inflammatory cascades, including cytokine release and blood-brain barrier disruption, which amplify tissue injury as detailed in broader pathophysiological discussions.[49]