Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chang'an

View on Wikipedia34°18′30″N 108°51′30″E / 34.30833°N 108.85833°E

| Chang'an | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 長安 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 长安 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Perpetual Peace" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chang'an, located in China's Shaanxi Province, was the capital city of several Chinese dynasties, including the Western Han and the Tang, from 202 BC to AD 907. At various times, it was the largest city in the world. Its name was subsequently changed, and during the Ming dynasty period its modern name of Xi'an was adopted.

The site of Chang'an south of the Wei River in central Xi'an has been inhabited since Neolithic times, when the Yangshao culture had a major center at Banpo to its south during the 5th millennium BC. Fenghao, the twin capitals of the Western Zhou, straddled the Feng River to its southwest from the 11th to 8th centuries BC and the state of Qin and its imperial dynasty had their capital in nearby Xianyang, north of the Wei, in the 4th & 3rd centuries BC. The First Emperor's mausoleum and its Terracotta Army lay to its east.

Liu Bang moved his court to the Changle Palace in 200 BC, soon after the establishment of the Western Han. It held a central position in the large but easily defended Guanzhong Region, near but outside the ruins of the Qin Xianyang and Epang Palaces. Han Chang'an grew up to the north of it and the adjacent Weiyang Palace. Weiyang continued to serve as the imperial palace of the Xin, late Eastern Han, Western Jin, Han-Zhao, Former Qin, Later Qin, Western Wei, Northern Zhou, and early Sui dynasties and became the largest palace ever built, covering 4.8 km2 (1,200 acres)—nearly seven times larger than the Forbidden City—before its destruction under the early Tang. The main areas of Sui and Tang-era Chang'an was south of the earlier settlement and southeast of Weiyang. Around AD 750, Chang'an was called a "million-man city" in Chinese records; most modern estimates put the population within the walls of the Tang city around 800,000–1,000,000.[1] The 742 census recorded in the New Book of Tang listed the population of Jingzhao, the province including the capital and its metropolitan area, as 1,960,188 people in 362,921 households[2] and modern scholars—including Charles Benn[3] and Patricia Ebrey[4]—have concurred that Chang'an and its immediate hinterland could have supported around 2,000,000 people.[5]

Amid the Fall of Tang, the warlord Zhu Wen forcibly relocated most of the city's remaining population to Luoyang in 904. Chang'an was of minor importance in the following centuries but again became a regional center under the Northern Song. Its name was changed repeatedly under the Mongol Yuan dynasty before the Ming settled on Xi'an and erected its city walls around the former Sui and Tang palace district, an area about an eighth the size of the medieval city at its height.

History

[edit]

Zhou and Qin period

[edit]The site of Chang'an south of the Wei River in central Xi'an has been inhabited since Neolithic times, when the Yangshao culture had a major center at Banpo to its south from around 5000 to around 4300 BC[6] and other sites in the area for several more centuries. Fenghao, the twin capitals of the Western Zhou, straddled the Feng River to its southwest from c. 1064 to 771 BC[7] and the state of Qin and its imperial dynasty had their capital in nearby Xianyang, north of the Wei, from 350 to 207 BC.[8] The First Emperor's mausoleum and its Terracotta Army lay beside Mount Li[9] to its east. Chang'an itself existed as a small village under the Qin.[10]

Han period

[edit]

Upon the Fall of Qin and the resolution of the Chu–Han Contention with the establishment of the Han dynasty in 202 BC, the emperor Liu Bang (posthumously honored as its Emperor Gaozu) initially ruled from Luoyang, the site of the Eastern Zhou capital Chengzhou and supposed center of the world.[11] This was in accordance with the majority of his advisors, themselves mostly from eastern China.[12] Upon reflection, however, he heeded the advice of a soldier Lou Jing and his general Zhang Liang that the Guanzhong Region—the Zhou and Qin heartland along the Wei River—could provide for a larger core population and offered much greater natural protection against potential unrest.[13] Additionally, Chang'an was far more centrally located in the lands directly administered by the Han emperor and much further from their border with the realm's notionally vassal kings.

Liu Bang commissioned his chancellor Xiao He to rehabilitate the Qin's Xingle Palace (興樂宮, "Palace of Flourishing Happiness") for use as his primary court in the 9th month of Year 5 of his reign as king of Han (202 BC).[14] This was completed as the 7×7 li Changle Palace[15] in the 2nd month of Year 7 (200 BC),[14] by which time Xiao He had already begun renovating the Zhangtai Palace (章台宮, "Palace of the Splendid Terrace")[16] as the 5×7 li Weiyang Palace.[15] According to Sima Qian's Records, Liu Bang returned to Chang'an in that year, initially reproaching his minister for the needless extravagance of constructing such enormous palaces in such close proximity to one another. Xiao He successfully argued, however, that the magnificence was necessary to overawe Liu's rivals and affirm the legitimacy of the dynasty.[17] Around the same time, thousands of clans in then military aristocracy were forcibly relocated to the region.[15] The minister Liu Jing described this policy as "weakening the root while strengthening the branch", but it served to keep potential rivals where they could be more easily observed and redirected their energy towards defending the new capital against the nearby Xiongnu. The Weiyang Palace was initially completed in 198 BC,[18] but Liu Bang continued to rule from the Changle Palace for the remainder of his life.[19] Subsequent emperors ruled from Weiyang while using Changle to house their mothers, wives, and concubines.[18] An arsenal was placed directly between the two palaces to protect them and the nascent city.[20]

The Han capital was located 5 km (3 mi) northwest of Xi'an under the Ming and Qing,[21] although the modern city has expanded to include it. Chang'an had a population of 146,000 in 195 BC,[15] when Liu Bang's son and successor Liu Ying (posthumously known as the Hui Emperor) began work on the city walls. He completed the walls in September[dubious – discuss] 191 BC, having used 146,000[14]–290,000 workers[10] serving 30-day corvées, as well as 20,000 convicts on continual work detail.[14] The city itself was largely completed by 189 BC,[10] its walls, streets, and buildings constructed at a 2° difference in alignment from the grid used within the palaces.[15] The wide main avenues were lined with locust, poplar, cypress, and other trees.[10] Given the importance of square shapes in ancient Chinese urban planning, the irregular shape of the walls of Han-era Chang'an was the subject of debate for centuries. The effort of Qin-era palaces to reconstruct astrological designs led to a common theory that the wall attempted to mimic the Little Dipper asterism. Just as likely, however, the northern wall protected existing buildings along the Wei River and the irregular southern extensions were forced on the city by the large palaces built on Qin-era terraces.[22] Liu Ying also removed the ancestral temples from the city, placing them beside the imperial tomb complexes instead; this arrangement was maintained throughout the Western Han.[23]

Emperor Wu began a third phase of construction which peaked in 100 BC with the construction of many new palaces. He also added the nine temples complex south of the city, and built the park. In 120 BC, Shanglin Park, which had been used for agriculture by the common people since Liu Bang was sealed off, was turned into an imperial park again. In the center of the park was a recreation of the three islands of the immortals mentioned in the Classic of Mountains and Seas: Penglai, Yingzhou, and Fangzhang. This became a theme in Chinese gardening, with the idea of "one pond, three hills" (一池三山) being subsequently employed in Hangzhou's West Lake, the Forbidden City's Taiye Lake, and the Summer Palace's Kunming Lake.[24] By the time he was finished, the area within the city walls was fully two-thirds occupied by imperial palaces[22] and nearly three-fourths of China's nobility lived in Chang'an or its vicinity.[25]

Also during the reign of Emperor Wu, the diplomat Zhang Qian was dispatched westward into Central Asia. Subsequently, Ching'an was the political, economic, and cultural center of China as well as the cosmopolitan eastern terminus of the overland Silk Road. It was a consumer city, a city whose existence was not primarily predicated upon manufacturing or trade but upon its role as the political and military center of China. By the AD 2 census, the population of the walled city was recorded as 246,200 in 80,000 households[15] and the population of the entire metropolitan region reckoned as 682,000.[26] Much of this population consisted of the scholar gentry class whose education was being sponsored by their wealthy aristocratic families. In addition to these civil servants, there was a larger underclass to serve them.

During the short-lived Xin dynasty of Wang Mang, he attempted to bring the design of the palaces and city in closer alignment to the idealized plans recorded in the Kaogongji, an apocryphal addition to the Book of Zhou.[27] He razed Emperor Wu's Jianzhang Palace[28] but constructed additional temples south of the city.[29] (These are traditionally listed as his "Nine Temples" but archaeologists have found the remains of more than nine similar foundations in the area and the Chinese 九 in the name may have simply been used in its figurative senses of "several" or "many".)[30] During the Lülin peasant rebellion that ended his reign, Chang'an was captured and sacked on 4 October AD 23 and Wang was killed and beheaded by the rebels two days later.[31] The Eastern Han government subsequently settled on Luoyang as their new primary capital while Chang'an continued to occasionally be referenced as the Western Capital or Xijing (西京). In the year 190, the Han court was seized and returned to Chang'an by the notorious chancellor Dong Zhuo, primarily as a strategically superior site against the insurgency mounting against him. After Dong's death in 192, the capital was moved back to Luoyang in August 196 and then to Xuchang in the autumn of 196.[32]

Jin, Sixteen Kingdoms, and Northern Dynasties period

[edit]During the fall of the Western Jin dynasty, Chang'an was made the Jin capital from 312 to 316 as they began to lose control over northern China. The city was conquered by the Han-Zhao in 316, signalling the end for the Western Jin and the beginning of the Eastern Jin in the south at Jiankang. Later on, Chang'an served as the capital of the Han-Zhao (318–329), Former Qin (351–385) and Later Qin (384–417). Under the Later Qin ruler, Yao Xing, Chang'an became an important hub for Buddhism in China.

The Eastern Jin briefly recovered Chang'an in 417 during the second northern expedition of Liu Yu (the future Emperor Wu of Liu Song), but was lost to the Helian Xia in 418. The city finally fell into the hands of the Northern Wei dynasty in 426 and remained under their control for more than a century. When the Wei was split in two, Chang'an became the capital of Western Wei (535–557), and also of its successor state Northern Zhou (557–581).

Sui and Tang period

[edit]

Sui Daxing and Tang Chang'an occupied the same location. In 582, Emperor Wen of the Sui dynasty sited a new region southeast of the much ruined Han dynasty Chang'an to build his new capital, which he called Daxing (大興, "Great Prosperity"). Daxing was renamed Chang'an in the year 618 when the Duke of Tang, Li Yuan, proclaimed himself the Emperor Gaozu of Tang. Chang'an during the Tang dynasty (618–907) was, along with Constantinople (now Istanbul) and Baghdad, one of the largest cities in the world.[33]

The Tang Dynasty was the last dynasty to have control of Chang'an before its downfall. The Tang had a preference for entertainment, writers, poets, singers, and dancers. There was an entertainment ward established in this dynasty that was considered to have the finest singers in the city and another with the finest dancers. During the Tang Dynasty, this institution was called "Jiaofang" (教坊) and hired singing courtesans and dancing courtesans to provide performances. The institution also hired male musicians to perform music.[34]

There was also a crackdown on religions by the Tang government. For example, The Xingqing Palace, once a Buddhist monastery, was converted to an imperial palace in the early 8th century when the emperor believed the monks were untrustworthy and wanted to use the palace for military training.[34] However, most of the religious crackdowns were focused on Sogdian or Kuchan religions such as Islam or the Church of the East.[35] However, Buddhist monasteries and structures were not immune. In 713, Emperor Xuanzong liquidated the highly lucrative Inexhaustible Treasury, which was run by a prominent Buddhist monastery in Chang'an. This monastery collected vast amounts of money, silk, and treasures through multitudes of anonymous rich people's repentances, leaving the donations on the premises without providing their name. Although the monastery was generous in donations, Emperor Xuanzong issued a decree abolishing their treasury on grounds that their banking practices were fraudulent, collected their riches, and distributed the wealth to various other Buddhist monasteries, Taoist abbeys, and to repair statues, halls, and bridges in the city.[36]

There were many rebellions and assassinations during this dynasty as well, in part due to the authoritarian and aggressive nature of the emperors and government officials. The government was more forceful in taking payments and tribute from citizens, and citizens were being divided up into more and more groups and selected for specific roles.[37] People were afraid of the government taking their property whenever it felt like it. In 613 where a family threw their gold into the well of their mansion because they feared the city government would confiscate it.[38] There were more forceful actions being taken by rebel groups during this dynasty. For example, in 815 assassins murdered Chancellor Wu as he was leaving the eastern gate of the northeastern most ward in southern Chang'an. This does not mean all citizens were on board with the rebels, as people were afraid of the rebels actions as much as the governments, if not more so. In the ninth century three maidservants committed suicide by leaping into a well and drowning once they heard the rebel Huang Chao was ransacking their mistress's mansion.[39] The government wanted to have a clear message though, and brutality was often used against the rebels.[35] There was an instance where an individual had his stomach cut open in order to defend Emperor Ruizong of Tang against charges of treason.[40] The markets and regular shops would be a site where people would gather to discuss rebellions in the region as well. Many rebel leaders would go to these areas to recruit people, as they knew many people were just barely making enough to get by.[41] In 835 palace troops captured rebel leaders in a tea shop that were planning a palace coup d'état against the chief court eunuchs.[42]

In 682, a culmination of major droughts, floods, locust plagues, and epidemics, a widespread famine broke out in the dual Chinese capital cities of Chang'an and Luoyang. The scarcity of food drove the price of grain to unprecedented heights of inflation, while a once prosperous era under emperors Taizong and Gaozong ended on a sad note.[43]

Much of Chang'an was destroyed during its repeated sacking during the An Lushan Rebellion and several subsequent events. Chang'an was occupied by the forces of An Lushan and Shi Siming, in 756; then taken back by the Tang government and allied troops in 757. In 763, Chang'an, modern-day Xian, was briefly occupied by the Tibetan Empire. In 765, Chang'an was besieged by an alliance of the Tibetan Empire and the Uyghur Khaganate. Several laws enforcing segregation of foreigners from Han Chinese were passed during the Tang dynasty. In 779, the Tang dynasty issued an edict which forced Uighurs in the capital, Chang'an, to wear their ethnic dress, stopped them from marrying Chinese females, and banned them from pretending to be Chinese.[44] Between 783 and 784, Chang'an was again occupied by rebels during the Jingyuan Rebellion.

In 881, Chang'an was occupied by the rebel Huang Chao, who made it the seat of his Qi Dynasty. In 882, the Tang dynasty briefly regained control of Chang'an. However, the Tang forces, although welcomed by the inhabitants, looted Chang'an before being driven back by the forces of Huang Chao. In revenge, Huang Chao conducted a systematic slaughter of the inhabitants after retaking the city. Chang'an was finally retaken by the Tang government in 883. In 904, the warlord Zhu Wen ordered the city's buildings demolished and the construction materials moved to Luoyang, which became the new capital. The residents, together with the emperor Zhaozong, were also forced to move to Luoyang. Chang'an never recovered after the apex of the Tang dynasty, but there are some monuments from the Tang era still standing.

Subsequent history

[edit]After Zhu Wen moved the capital to Luoyang, the Youguo Governorate (佑國軍) was established in Chang'an, with Han Jian as its first jiedushi. Han Jian rebuilt Chang'an on the basis of the old Imperial City. Much of Chang'an was abandoned and the new town, called Xincheng ("New City") by its remaining inhabitants, was less than 1/16 the size of the old Chang'an in area.[45] The rest of the city was overrun by nature and was used for agriculture. The northern and eastern city wall was expanded a little and the official name of the city was changed from Jingzhao to Xi'an under the Ming dynasty.[46]

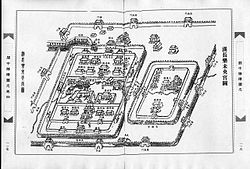

City structure

[edit]The overall form of the city[when?] was an irregular rectangle. The ideal square of the city had been twisted into the form of the Big Dipper for astrological reasons, and also to follow the bank of the Wei River. The eight avenues divided the city into nine districts. These nine main districts were subdivided into 160 walled 1×1 li wards.[15] About 50–100 families lived in each ward. Historically, Chang'an grew in four phases: the first from 200 to 195 BC when the palaces were built; the second 195–180 BC when the outer city walls were built; the third between 141 and 87 BC with a peak at 100 BC; and the fourth from 1 BC – AD 24 when it was destroyed.

The Xuanping Gate was the main gate between the city and the suburbs. The district north of the Weiyang Palace was the most exclusive. The main market, called the Nine Markets, was the eastern economic terminus of the Silk Road. Access to the market was from the northeast and northwest gates, which were the most heavily used by the common people. The former connected with a bridge over the Wei River to the northern suburbs and the latter connected with the rest of China to the east. An intricate network of underground passages connected the imperial harem with other palaces and the city.[47] These passages were controlled by underground gatehouses and their existence was not known to the public. The city was broken up into three districts by internal walls: the Palace, the Imperial City, and the Outer City.[37]

Palace City

[edit]The Palace City (宮城, Gongcheng) was reserved to the emperor and his entourage. The Palace City also had a vast royal garden, which was referred to as the "Forbidden Garden", as it was not accessible to the general public or even many government employees.[37] The idea behind giving the emperor this space was to give him space to think and make decisions. The seclusion of the area was also a mark of the importance and sacredness of the emperor.[41]

Imperial City

[edit]The Imperial City (皇城, Huangcheng) was delegated for government workers and administrators. This is where the bureaucrats who kept the administrative processes in the country worked and lived,[37] keeping them focused on their work. The bureaucrats were so vital to the operations of the country that the court wanted their attention focused solely upon it.[41]

Outer City

[edit]The Outer City (外郭城, Waiguocheng) is where many of the common civilians would live. There were about 110 separately walled wards, two markets, suburbs, villas for lower-level government officials, and religious institutions.[37] This is the area where many travelers would stay and trade with the nation, where typically it was bartering that would occur. There would be some coinage used, but typically silk was one of the main types of currency people used to exchange for goods and services.[35] This part of the city housed millions of peoples, saw the mixing of different cultures and religions, and was a main focus for government officials, as any architectural or structural problems could bring imbalance within the empire.[41]

The West and East Markets would open at noon, announced by the 300 strikes on a loud drum, while the markets would close one hour and three quarters before dusk, the curfew signaled by the sound of 300 beats to a loud gong.[36] After the official markets were closed for the night, small night markets in residential areas would then thrive with plenty of customers, despite government efforts in the year 841 to shut them down.[36]

The West Market (西市) covered the size of two regular city wards and was divided into 9 different city blocks. It sported a Persian bazaar that catered to tastes and styles popular then in medieval Iran. It had numerous wineshops, taverns, and vendors of beverages (tea being the most popular), gruel, pastries, and cooked cereals. There was a safety deposit firm located here as well, along with government offices in a central city block that monitored commercial actions.[35]

The East Market (東市), like the West Market, was a walled and gated marketplace that had nine city blocks and a central block reserved for government offices that regulated trade and monitored the transactions of goods and services. There was a street with the name "Ironmongers' Lane", plenty of pastry shops, taverns, and a seller of foreign musical instruments.[36]

Layout of the city

[edit]

Under the Tang, the main exterior walls of Chang'an rose 18 ft (5.5 m) high, were 5 mi (8.0 km) by six miles in length, and formed a city in a rectangular shape, with an inner surface area of 30 sq mi (78 km2).[42] The areas to the north that jutted out like appendages from the main wall were the West Park, the smaller East Park, and the Daming Palace, while the southeasternmost extremity of the main wall was built around the Serpentine River Park that jutted out as well. The West Park walled off and connected to the West Palace (guarded behind the main exterior wall) by three gates in the north, the walled-off enclosure of the Daming Palace connected by three gates in the northeast, the walled-off East Park led in by one gate in the northeast, and the Serpentine River Park in the southeast was simply walled off by the main exterior wall, and open without gated enclosures facing the southeasternmost city blocks. There was a Forbidden Park to the northwest outside of the city, where there was a cherry orchard, a Pear Garden, a vineyard, and fields for playing popular sports such as polo and cuju (ancient Chinese football).[48] On the northwest section of the main outer wall there were three gates leading out to the Forbidden Park, three gates along the western section of the main outer wall, three gates along the southern section of the main outer wall, and three gates along the eastern section of the main outer wall.[49]

Although the city had many different streets and roads passing between the wards, city blocks, and buildings, there were distinct major roads (lined up with the nine gates of the western, southern, and eastern walls of the city) that were much wider avenues than the others.[50] There were six of these major roads that divided the city into nine distinct gridded sectors (listed below by cardinal direction). The narrowest of these streets were 82 ft (25 m) wide, those terminating at the gates of the outer walls being 328 ft (100 m) wide, and the largest of all, the Imperial Way that stretched from the central southern gate all the way to the Administrative City and West Palace in the north, was 492 ft (150 m) wide.[51] Streets and roads of these widths allowed for efficient fire breaks in the city of Chang'an. For example, in 843, a large fire consumed 4,000 homes, warehouses, and other buildings in the East Market, yet the rest of the city was at a safe distance from the blaze (which was largely quarantined in East Central Chang'an).[51] The citizens of Chang'an were also pleased with the government once the imperial court ordered the planting of fruit trees along all of the avenues of the city in 740.[52]

City walls

[edit]The 25.7 km long city wall was initially 3.5 m wide at the base tapering upward 8 m for a top width of 2 m.[21] Beyond this wall, a 6.13 m wide moat with a depth of 4.62 m was spanned by 13.86 m long stone bridges. The wall was later expanded to 12–16 m at base and 12 m high. The moat was expanded to 8 m wide and 3 m deep. The expansion of the wall was likely a solution to flooding from the Wei River. The entire city was sited below the 400 m contour line which the Tang dynasty used to mark the edge of the floodplain.[15]

Twelve gates with three gateways each, according with the ritual formulas of Zhou dynasty urban planning, pierced the wall. These gates were distributed three a side and from them eight 45 m wide main avenues extended into the city.[21] These avenues were also divided into three lanes aligned with the three gateways of each gate. The lanes were separated by median strips planted with pine, elm, and scholar trees. Bachengmen Avenue was an exception with a width of 82 m and no medians.[15] Four of the gates opened directly into the palaces.

The northern, western and southern ends of the walls were zig-zagged and the eastern part of the walls were straight. There were military garrisons at each side of the wall. However, on the southern end, the garrison was on the outside part of the city. The northern camp was also close to the royal entrance of Weiyang. The walls on the northern side also divided the military's armory perimeter in half, dividing the arms on each side.[53]

Water systems

[edit]

Within the West Park was a running stream and within the walled enclosure of the West Palace were two running streams, one connecting three ponds and another connecting two ponds. The small East Park had a pond the size of those in the West Palace. The Daming Palace and the Xingqing Palace (along the eastern wall of the city) had small lakes to boast. The Serpentine River Park had a large lake within its bounds that was bigger than the latter two lakes combined, connected at the southern end by a river that ran under the main walls and out of the city.[49]

There were five transport and sanitation canals running throughout the city, which had several water sources, and delivered water to city parks, gardens of the rich, and the grounds of the imperial palaces.[52] The sources of water came from a stream running through the Forbidden Park and under the northern city wall, two running streams from outside the city in the south, a stream that fed into the pond of the walled East Park, which in turn fed into a canal that led to the inner city. These canal waterways in turn streamed water into the ponds of the West Palace; the lake in the Xingqing Palace connected two canals running through the city. The canals were also used to transport crucial goods throughout the city, such as charcoal and firewood in the winter.[52]

The Stone Dike, located around the Kunming Pond, was designed as one of the primary regulators for water flow and regulation. The Kunming Pond also had the Raise-River Slope, which was a man made contraption to divide the water into two streams. The purpose of both the Stone Dike and Raise-River Slope was to get the water flowing northward and some water into water store houses. In order to make it into the royal parts of the city, water flow would have to be increased several times a year, as the pond was about 1500 meters from the royal areas.[41]

The Jiao River was a man-made river which ran east to west and linked the Jue River to the Feng River. This river helped with outflow, and ensured that rivers near the capital flowed farther before emptying out into the Wei River.[41]

Food supply

[edit]Those living in Chang'an relied a lot on farming goods for sustenance. Many ate pancakes, greens, wheat, soybeans, rice, millet, barley, and sweet bean stew which grew from local farmers. Most of the grain products were grown in the greater metropolitan regions of Chang'an. Each person was also given a monthly food allowance of 3 bushes of grain a month. There were five granaries in which these monthly allowance grains were held. These were the Great Grainery, Capital Grainery, Jiahe Grainery, Sweet Springs Grainery, and the Pier Grainery. These granaries relied on the water transportation systems from the canals which were built to transport food among other materials.[41]

Palaces

[edit]

- Changle Palace (長樂宮, Chánglè Gōng, "Palace of Perpetual Joy"), also called the East Palace, was built over the ruins of the Qin-dynasty Xingle Palace. After Liu Bang it was used as the residence of empress dowagers and the imperial harem. The 10,000 m wall surrounded a square 6 km2 complex. Important halls of the palace included: Linhua Hall, Changxin Hall, Changqiu Hall, Yongshou Hall, Shenxian Hall, Yongchang Hall, and the Bell Room.

- Weiyang Palace (未央宮, Wèiyāng Gōng, "Eternal Palace"), also known as the West Palace, was the official center of government from Emperor Huidi onwards. The palace was a walled rectangle 2250×2150 m enclosing a 5 km2 building complex of 40 halls. There were four gates in the wall facing a cardinal direction. The east gate was used only by nobility and the north one only by commoners. The palace was sited along the highest portion of the ridgeline on which Chang'an was built. In, fact the Front Hall at the center of the palace was built atop the exact highest point of the ridge. The foundation terrace of this massive building is 350×200×15 m. Other important halls are: Xuanshi Hall, Wenshi Hall, Qingliang Hall, Qilin Hall, Jinhua Hall, and Chengming Hall. Used by seven dynasties this palace has become the most famous in Chinese history.

- Gui Palace (桂宫, Gui Gōng, "Cassia Palace") was built as an extension of the harem in 100 BC.

- North Palace (北宮, Běi Gōng) was a ceremonial center built in 100 BC.

- Mingguang Palace (明光宫) was built as an imperial guesthouse in 100 BC.

- Jianzhang Palace (建章宫, "Palace of Establishing Rules") was built in 104 BC in Shanglin Park. It was a rectangle 20×30 li with a tower 46 m high.

- Epang Palace (阿房宮, Ēpáng Gōng)

Peoples and ethnicities

[edit]Two of the largest ethnic groups in Chang'an were Han Chinese and Sogdians (people from Sogdia). Their cultures and traditions at times overlapped and combined. For instance, there were tombs within the city in Chinese style, had Chinese writing, led to an underground compartment, and had descriptions of the deceased. They also had Sogdian elements such as a miniature stone house and a stone bedlike platform. Funeral beds tend to also depict a Sogdian swirl as well. There were also many motifs that involved things like bird priests, winged, crowned horsed, winged musicians, and crowned human figures with streamers behind them. These motifs are not fully known as not much is known of the Sogdian religion.[35]

Ease of travel from the Yellow River and Yangtze River also made it easier for other travelers to go to Chang'an and sell goods to the people of the city. Some of these people even stayed and lived in the city as well. Chang'an would be an overlap for travelers going to other parts of the region. People from India, the Arabian Peninsula, Iranian plateau, and Eastern African Coast would have people traveling to there and people from there traveling and residing in Chang'an.[54]

Not every government official took a liking to foreigners coming and staying into Chang'an. For instance, Yuan Zhen wrote about how non-Chinese people were "barbaric" and how their cultures and practices would degrade the Chinese way of life.[55]

Religious institutions

[edit]

Immigrants brought the ideas of new religions into the capital. The hub-status of the city caused these religions to stick and grow over time. Evidence suggests at least five or six Zoroastrian temples existed inside of the city while four temples existed around the Western Market. Christianity was around at this time as well. It was brought by a man named Aluoben who was sent by a church official in Seleucia-Ctesiphon. The Church of the East first settlement was in China circa 635. Several hundred stone tablets and an artifact related to the Church of the East were discovered, which pointed to the existence of an affiliated single Christian church. The Church of the East is a Christian organization which sponsored the creation of churches in multiple Chinese cities, like Chang'an. Members of the Church of the East had received support from the Tang dynasty and yet during this same dynasty, the emperor placed a ban on Buddhism and Christianity, and only Buddhism survived. In 843 the Tang emperor also banned the religion of Manichaeism. A few years later the emperor banned Zoroastrianism and reinstated the ban on Buddhism. This ban on Buddhism was lifted a short while later when the current emperor passed away.[35] Emperor Xuanzong[56] decreed around the year 742 AD (as Tangmingsi[57], 唐明寺) that a place of worship for the Muslim community was to be constructed in the city, and the Great mosque of Xi'an was established where it still stands to this day.[58]

Suburban sacrifices

[edit]High level sacrifices would be orchestrated and performed by the high ruling family near the suburbs of Chang'an. Typically, these sacrifices worshipped the Earth and Heaven. These would sometimes entail human sacrifices of imprisoned individuals or enslaved peoples but would also entail sacrifices of parts of the earth and animals. There were several alters constructed for worship to several deities. The most significant came from the Han Wudi, who emphasized alters to Taiyi (The Grand Unity), Ganquan (Sweet Springs), and Houtu (Sovereign Earth).[59]

There were groups that were against these sacrifices. Kuang Heng had enacted reforms as emperor, limiting the sacrifices. One prominent figure on this topic was Liu Xiang, who formed a group to get rid of Heng's reforms. During the reign of Chengdi, there were many natural disasters that occurred. Liu Xiang argued that his research as a scholar showcases that the sacrifices were a part of an old cult, but they were proven to work. The idea was that if these sacrifices occurred, there would be balance between heaven and earth. When these sacrifices stopped, this gave the idea that the balance was broken. Chengdi would eventually restore this sacrificial system in 14 BC. By 4 BC, all of the old Gods that were banned were restored and more temples were enacted. Chengdi did try to keep the sacrifices away from Chang'an to keep the practice separate from the capital.[41]

Citywide events

[edit]Sources:[38]

The grandest of all festivals, and a seven-day holiday period for government officials. Civil officials, military officers, and foreign emissaries gathered first in the early hours of the morning to attend a levee, an occasion where omens, disasters, and blessings of the previous year would be reviewed, along with tribute of regional prefectures and foreign countries presented. It was also an opportunity for provincial governors to present their recommended candidates for the imperial examination. Although festival ceremonies in Chang'an were lavish, rural people in the countryside celebrated privately at home with their families in age old traditions, such as drinking a special wine, Killing Ghosts and Reviving Souls wine, that was believed to cure illnesses in the following year.

A three-day festival held on the 14th, 15th, and 16th days of the first full moon. This was the only holiday where the government lifted its nightly curfew all across the city so that people could freely exit their wards and stroll about the main city streets to celebrate. Citizens attempted to outdo one another each year in the amount of lamps and the size of lamps they could erect in a grand display. By far the most prominent was the one in the year 713 erected at a gate in Chang'an by the recently abdicated Emperor Ruizong of Tang. His lantern wheel had a recorded height of 200 ft (61 m), the frame of which was draped in brocades and silk gauze, adorned with gold and jade jewelry, and when it had its total of some 50,000 oil cups lit the radiance of it could be seen for miles.

Lustration

[edit]This one-day festival took place on the third day of the third moon (dubbed the "double-three"), and traditionally was meant to dispel evil and wash away defilement in a river with scented aromatic orchis plants. By the Tang era it had become a time of bawdy celebration, feasting, wine drinking, and writing poetry. The Tang court annually served up a special batch of deep fried pastries as dessert for the occasion, most likely served in the Serpentine River Park.

This solar-based holiday on April 5 (concurrent with the Qingming Festival) was named so because no fires were allowed to be lit for three days, hence no warmed or hot food. It was a time to respect one's ancestors by maintaining their tombs and offering sacrifices, while a picnic would be held later in the day. It was also a time for fun in outdoor activities, with amusement on swing sets, playing cuju football, horse polo, and tug of war. In the year 710, Emperor Zhongzong of Tang had his chief ministers, sons-in-law, and military officers engage in a game of tug of war, and purportedly laughed when the oldest ministers fell over. The imperial throne also presented porridge to officials, and even dyed chicken and duck eggs, similar to the practice on Easter in the Western world.

Fifth Day of the Fifth Moon

[edit]This one-day holiday dubbed the Dragon Boat Festival was held in honor of an ancient Chinese statesman Qu Yuan (c. 340–278 BC) from the State of Chu. Ashamed that he could not save the dire affairs of his state or his king by offering good council, Qu Yuan leaped into a river and committed suicide; it was said that soon after many went out on the river in boats in a desperate attempt to rescue him if still alive. This act turned into a festive tradition of boarding a dragon boat to race against other oarsmen, and also to call out Qu's name, still in search of him. The type of food commonly eaten during the Tang period for this festival was either glutinous millet or rice wrapped in leaves and boiled.

Seventh Night of the Seventh Moon

[edit]This was a one-day festival that was held in honor of the celestial love affair with deities associated with the star Altair (the male cow-herd deity) in the constellation Aquila and the star Vega (the female weaver maid deity) in the constellation Lyra. For this holiday, women prayed for the enhancement of their skills at sewing and weaving. In the early eighth century Tang servitors had erected a 100 ft (30 m) tall hall by knotting brocades to a bamboo frame and laid out fruits, ale, and roasts as offerings to the two stellar lovers. It was during this holiday that the emperor's concubines threaded polychrome thread into needles with nine eyes, while facing the Moon themselves (in a ritual called "praying for skill [in sewing and weaving]").

Fifteenth Day of the Seventh Moon

[edit]This holiday was called All Saints' Feast, developing from the legend Mulian Rescues His Mother. in which the bodhisattva savior Mulian who had discovered his mother paying for her sinful ways while in purgatory filled with hungry ghosts. According to the tale, she starved there because any food that she put into her mouth would turn into charcoal. Then it was said that she told the Buddha to make an offering with his clergy on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, a virtuous act that would free seven generations of people from being hungry ghosts in Hell as well as people reborn as lower animals. After Mulian was able to save his own mother by offerings, Mulian convinced the Buddha to make the day into a permanent holiday. This holiday was an opportunity of Buddhist monasteries to flaunt their collected wealth and attract donors, especially by methods of drawing crowds with dramatic spectacles and performances.

Fifteenth Day of the Eighth Moon

[edit]This festival (today simply called the Moon Festival or Mid-Autumn Festival), took place in mid autumn, and was designated as a three-day vacation for government officials. Unlike the previous holiday's association with Buddhism, this holiday was associated with Taoism, specifically Taoist alchemy. There was a tale about a hare on the moon who worked hard grinding ingredients for an elixir by using a mortar and pestle. In folklore, a magician escorted Emperor Illustrious August to the palace of the moon goddess across a silver bridge that was conjured up by him tossing his staff into the air. In the tale, on the fifteenth day of the eighth moon, the emperor viewed the performance of "Air of the Rainbow Robe and Feathered Skirt" by immortal maids. He memorized the music, and on his return to earth taught it to his performers. For people in Chang'an (and elsewhere), this holiday was a means for many to simply feast and drink for the night.

Ninth Day of the Ninth Moon

[edit]This was a three-day holiday associated with the promotion of longevity (with chrysanthemum as the main symbol). It was a holiday where many sought to have picnics out in the country, especially in higher elevated areas such as mountain sides. Without the ability to travel away to far off mountains, inhabitants of Chang'an simply held their feasts at the tops of pagodas or in the Serpentine River Park. Stems and leaves of chrysanthemum were added to fermented grains and were brewed for a year straight. On the same festival the following year, it was believed that drinking this ale would prolong one's life.

The Last Day of the Twelfth Moon

[edit]On this holiday ale and fruit were provided as offerings to the god of the stove, after having Buddhist or Taoist priests recite scripture at one's own home (if one had the wealth and means). Offerings were made to the stove god because it was his responsibility to make annual reports to heaven on the good deeds or sins committed by the family in question. A family would do everything to charm the god, including hanging a newly painted portrait of the god on a piece of paper above their stove on New Years, which hung in the same position for an entire year. It was a common practice to rub in some alcoholic beverage across the picture of the deities mouth, so that he would become drunk and far too inebriated to make any sort of reasonably bad or negative report about the family to heaven.

Grand Carnivals

[edit]Carnivals during the Tang period were lively events, with great quantities of eating, drinking, street parades, and sideshow acts in tents. Carnivals had no fixed dates or customs, but were merely celebrations bestowed by the emperor in the case of his generosity or special circumstances such as great military victories, abundant harvests after a long drought or famine, sacrifices to gods, or the granting of grand amnesties.[60] This type of carnival as a nationwide tradition was established long before the Tang by Qin Shihuang in the third century BC, upon his unification of China in 221.[61] Between 628 and 758, the imperial throne bestowed a total of sixty nine different carnivals, seventeen of which were held under Empress Wu.[60]

These carnivals generally lasted 3 days, and sometimes five, seven, or nine days (using odd numbers due so that the number of days could correspond with beliefs in the cosmos). The carnival grounds were usually staged in the wide avenues of the city, and smaller parties in attendance in the open plazas of Buddhist monasteries. However, in 713, a carnival was held in the large avenue running east to west between the West Palace walls and the government compounds of the administrative city, an open space that was 0.75 mi (1.21 km) long and 1,447 ft (441 m) wide, and was more secure since the guard units of the city were placed nearby and could handle crowd control of trouble arose.[62]

Carnivals of the Tang dynasty featured large passing wagons with high poles were acrobats would climb and perform stunts for crowds. Large floats during the Tang, on great four-wheeled wagons, rose as high as five stories, called 'mountain carts' or 'drought boats'.[40] These superstructure vehicles were draped in silken flags and cloths, with bamboo and other wooden type frames, foreign musicians dressed in rich fabrics sitting on the top playing music, and the whole cart drawn by oxen that were covered in tiger skins and outfitted to look like rhinoceroses and elephants. An official in charge of the Music Bureau in the early seventh century set to the task of composing the official music that was to be played in the grand carnival of the year. On some occasions the emperor granted prizes to those carnival performers he deemed to outshine the rest with their talents.

Legacy

[edit]

Chang'an's layout influenced the city planning of several other Asian capitals for many years to come. Chang'an's walled and gated wards were much larger than conventional city blocks seen in modern cities, as the smallest ward had a surface area of 68 acres, and the largest ward had a surface area of 233 acres (0.94 km2).[33] The height of the walls enclosing each ward were on average 9 to 10 ft (3.0 m) in height.[33] The Japanese built their ancient capitals, Heijō-kyō (today's Nara) and later Heian-kyō or Kyoto, modeled after Chang'an in a more modest scale and without the same level of fortifications.[63] The modern Kyoto still retains some characteristics of Sui-Tang Chang'an. Similarly, the Korean Silla dynasty modeled their capital of Gyeongju after the Chinese capital. Sanggyeong, one of the five capitals of the state of Balhae, was also laid out like Chang'an.

Archaeological finds

[edit]Two Sogdian tombs were discovered in Xi'an in the early 2000s. They were the first Sogdian tombs discovered which had never been opened before their discovery by archaeologists, which meant that the artifacts inside the tombs were well preserved.[35] The tombs are evidence of the cultural interconnections between immigrants and Chinese cultural practices which they adopted when they moved to large population centers like Chang'an.[35]

An Jia Tomb

[edit]The tomb of An Jia was discovered in 2001 and had mixed elements of Chinese and Sogdian burial practices. An Jia's remains were buried in an uncommon manner as his bones were discovered strewn throughout the tomb which was uncommon to both the Confucian and Zoroastrian customs at the time.[35] Archaeologists also uncovered an epitaph to An Jia written in the Chinese language which retells his life, career, and achievements as a "Sabao of the Tong Prefecture and Commander General of the Great Zhou Dynasty".[35]

Shi Wirkak Tomb

[edit]The tomb of Wirkak was discovered in 2003–2004 slightly over 1.6 km (1 mile) east of An Jia's tomb.[35] Similarly to An Jia's tomb it also had the mix of both the Chinese and Sogdian burial practices. However, unlike An Jia the there were two versions of Shi Wirkak's epitaph, one in Chinese and one in Sogdian, though they were not the direct translations of each other which in quality of text could mean that the scribe who wrote the epitaphs had little understanding of either language.[35]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Chandler (1987)[page needed] & Modelski (2000).[page needed]

- ^ New Book of Tang, vol. 41 (Zhi, vol. 27), Geography, §1.

- ^ Benn (2002), p. 46.

- ^ Ebrey & al. (2006), p. 93.

- ^ Haywood, Jotischky & McGlynn (1998), 3.20 & 3.31.

- ^ Boyd (2017), p. 68.

- ^ Khayutina (2008), pp. 25 & 48.

- ^ Fu & al. (2009), pp. 91 & 93.

- ^ Li Daoyuan, Commentary on the Water Classic, Ch. 19 (in Chinese).

- ^ a b c d Fu & al. (2009), p. 104.

- ^ Hung (2011), p. 172.

- ^ Hung (2011), p. 173.

- ^ Hung (2011), pp. 172–174.

- ^ a b c d Habberstad (2014), p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schinz (1996).[page needed]

- ^ Habberstad (2014), p. 29.

- ^ Habberstad (2014), p. 23.

- ^ a b Steinhardt (2019), p. 90.

- ^ Habberstad (2014), p. 37.

- ^ Tang (2015), p. 61.

- ^ a b c China Culture (2003).

- ^ a b Steinhardt (2019), p. 89.

- ^ Liu (2002), p. 43.

- ^ Cultural China (2007).

- ^ Nylan (2015), p. 50.

- ^ Nylan (2015), p. 46.

- ^ Tang (2015), p. 67.

- ^ Tang (2015), p. 65.

- ^ Tang (2015), p. 68.

- ^ Tang (2015), p. 74.

- ^ Hymes (2000), p. 13.

- ^ De Crespigny (2006), pp. 35–39.

- ^ a b c Benn (2002), p. 50.

- ^ a b Bossler (2012).[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hansen (2017), pp. 239–284.[clarification needed]

- ^ a b c d Benn (2002), p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e Wen (2024).[page needed]

- ^ a b Benn (2002), pp. 149–153.

- ^ Benn (2002), p. 152.

- ^ a b Benn (2002), p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chang'an 26 BCE.[clarification needed][page needed]

- ^ a b Benn (2002), p. 47.

- ^ Benn (2002), p. 4.

- ^ Schafer (1985), p. 22

- ^ Xue (2004).[page needed]

- ^ Cartwright (2017).

- ^ IACASS (2006).

- ^ Benn (2002), p. xiv.

- ^ a b Benn (2002), p. xiii.

- ^ Benn (2002), p. xviii.

- ^ a b Benn (2002), p. 48.

- ^ a b c Benn (2002), p. 49.

- ^ Xie (2024).[page needed]

- ^ UNESCO (2021).

- ^ Follett (2020).

- ^ 统先, 傅 (2019). 中国回教史. Beijing: 商务印书馆. pp. 33–36.

- ^ Steinhardt, Nancy S. (2015). China's Early Mosques. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-7041-3.

- ^ "Sino-Arabic script and architectural inscriptions in Xi'an Great Mosque, China". www.researchgate.net. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ Chang'an 26 BCE.[clarification needed][page needed]

- ^ a b Benn (2002), p. 155.

- ^ Benn (2002), p. 154.

- ^ Benn (2002), p. 156.

- ^ Ebrey & al. (2006), p. 92.

Sources

[edit]- Chang'an 26 BCE: An Augustan Age in China, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0-295-99405-5.

- "Site of Capital Chang'an of Han", China Culture, Beijing: China Daily, September 2003, archived from the original on 15 March 2014.

- "Kunming Lake Area of the Summer Palace", Cultural China, Shanghai: Hongtu Real Estate Development Co., 2007, archived from the original on 2014-07-04, retrieved 2025-08-16.

- "Underground Passages Reveal Power Struggle in Ancient Han Capital", Chinese Archaeology, Beijing: Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, 9 November 2006, archived from the original on 28 September 2011, retrieved 19 June 2018

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - "Did You Know? The Cosmopolitan city of Chang'an at the Eastern End of the Silk Roads", Silk Roads Programme, Paris: UNESCO, 2021.

- Benn, Charles (2002), China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-517665-0.

- Bossler, Beverly (June 2012), "Vocabularies of Pleasure: Categorizing Female Entertainers in the Late Tang Dynasty", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, vol. 72, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 71–99.

- Boyd, David (2017), "Banpocun", Encyclopedia of Chinese History, Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 68–69, ISBN 978-1-317-81715-4.

- Cartwright, Mark (12 July 2017), "Chang'an", World History Encyclopedia.

- Chandler, Tertius (1987), Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census, Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, ISBN 0-88946-207-0.

- De Crespigny, Rafe (2006), A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD), Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-9047411840.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; et al. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- Follett, Chelsea (27 August 2020), "Centers of Progress, Pt. 10: Chang'an (Trade)", Human Progress, Washington: Cato Institute.

- Fu Chonglan; et al. (2009), Introduction to the Urban History of China, China Connections, Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-981-13-8207-9.

- Habberstad, Luke Ronald (2014), Courtly Institutions, Status, and Politics in Early Imperial China (206 BCE–9 CE) (PDF), Berkeley: University of California.

- Hansen, Valerie (2017), The Silk Road: A New History with Documents, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-020892-9.

- Haywood, John; Jotischky, Andrew; McGlynn, Sean (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600–1492, Barnes & Noble, ISBN 978-0-7607-1976-3.

- Hung Hing Ming (2011), The Road to the Throne: How Liu Bang Founded China's Han Dynasty, New York: Algora Publishing, ISBN 978-0-87586-839-4.

- Hymes, Robert (2000), Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-11004-4.

- Khayutina, Maria (2008), "Western 'Capitals' of the Western Zhou Dynasty: Historical Reality and Its Reflections until the Time of Sima Qian", Oriens Extremus, vol. 47, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 25–65, JSTOR 24048045.

- Liu Xujie (2002), "The Qin and Han Dynasties", Chinese Architecture, New Haven: Yale University, pp. 33–60, ISBN 0-300-09559-7.

- Modelski, George (2000), World Cities: –3000 to 2000, Washington: FAROS, ISBN 0-9676230-1-4.

- Nylan, Michael (2015), "Introduction", Chang'an 26 BCE: An Augustan Age in China, Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 3–52, ISBN 978-0-295-99405-5.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985) [1963], The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'ang Exotics, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05462-8.

- Schinz, Alfred (1996), The Magic Square: Cities in Ancient China, Stuttgart: Edition Axel Menges, ISBN 3-930698-02-1.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (2019), Chinese Architecture: A History, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-19197-3.

- Tang Xiaofeng (2015), "The Evolution of the Imperial Urban Form in Western Han Chang'an", Chang'an 26 BCE: An Augustan Age in China, Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 55–74, ISBN 978-0-295-99405-5.

- Wen Xin (2024), "The Song Rediscovery of Chang'an", Journal of Song–Yuan Studies, vol. 53, pp. 127–190, doi:10.1353/sys.2024.a946876.

- Xie Libin (2024), "A Study of Military Defense in the Ancient Chinese City of Chang'an during the Han Dynasty", Minden: Journal of History and Archaeology, vol. 1, Pulau Penang: Penerbit Universiti Sains Malaysia, JSTOR 23354213.

- Xue Pingshuan (March 2004), "Wǔdài Sòng Yuán Shíqí Gǔdū Cháng'ān Shāngyè de Xīngshuāi Yǎnbiàn" 五代宋元时期古都长安商业的兴衰演变 [The Rise and Fall of Commerce in the Ancient Capital Chang'an during the Five Dynasties, Song, and Yuan], Zhōngguó Lìshǐ Dìlǐ Lùncóng 《中國歷史地理論叢》 [Collections of Essays on Chinese Historical Geography] (in Chinese), vol. 19, Xi'an: Shaanxi People's Publishing House, pp. 57 ff.