Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

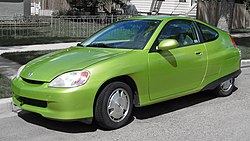

Hybrid electric vehicle

View on Wikipedia

A hybrid electric vehicle (HEV) is a type of hybrid vehicle that couples a conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) with one or more electric engines into a combined propulsion system. The presence of the electric powertrain, which has inherently better energy conversion efficiency, is intended to achieve either better fuel economy or better acceleration performance than a conventional vehicle. There is a variety of HEV types and the degree to which each functions as an electric vehicle (EV) also varies. The most common form of HEV is hybrid electric passenger cars, although hybrid electric trucks (pickups, tow trucks[2] and tractors), buses, motorboats,[3] and aircraft also exist.

Modern HEVs use energy recovery technologies such as motor–generator units and regenerative braking to recycle the vehicle's kinetic energy to electric energy via an alternator, which is stored in a battery pack or a supercapacitor. Some varieties of HEV use an internal combustion engine to directly drive an electrical generator, which either recharges the vehicle's batteries or directly powers the electric traction motors; this combination is known as a range extender.[4] Many HEVs reduce idle emissions by temporarily shutting down the combustion engine at idle (such as when waiting at the traffic light) and restarting it when needed; this is known as a start-stop system. A hybrid-electric system produces less tailpipe emissions than a comparably sized petrol engine vehicle since the hybrid's petrol engine usually has smaller displacement and thus lower fuel consumption than that of a conventional petrol-powered vehicle. If the engine is not used to drive the car directly, it can be geared to run at maximum efficiency, further improving fuel economy.

Ferdinand Porsche developed the Lohner–Porsche in 1901.[3] But hybrid electric vehicles did not become widely available until the release of the Toyota Prius in Japan in 1997, followed by the Honda Insight in 1999.[5] Initially, hybrid seemed unnecessary due to the low cost of petrol. Worldwide increases in the price of petroleum caused many automakers to release hybrids in the late 2000s; they are now perceived as a core segment of the automotive market of the future.[6][7][better source needed]

As of April 2020[update], over 17 million hybrid electric vehicles have been sold worldwide since their inception in 1997.[8][9] Japan has the world's largest hybrid electric vehicle fleet with 7.5 million hybrids registered as of March 2018[update].[10] Japan also has the world's highest hybrid market penetration with hybrids representing 19.0% of all passenger cars on the road as of March 2018[update], both figures excluding kei cars.[10][11] As of December 2020[update], the U.S. ranked second with cumulative sales of 5.8 million units since 1999,[12] and, as of July 2020[update], Europe listed third with 3.0 million cars delivered since 2000.[13]

Global sales are led by the Toyota Motor Corporation with more than 15 million Lexus and Toyota hybrids sold as of January 2020[update],[8] followed by Honda Motor Co., Ltd. with cumulative global sales of more than 1.35 million hybrids as of June 2014[update];[14][15][16] As of September 2022[update], worldwide hybrid sales are led by the Toyota Prius liftback, with cumulative sales of 5 million units.[1] The Prius nameplate had sold more than 6 million hybrids up to January 2017.[17] Global Lexus hybrid sales achieved the 1 million unit milestone in March 2016.[18] As of January 2017[update], the conventional Prius is the all-time best-selling hybrid car in both Japan and the U.S., with sales of over 1.8 million in Japan and 1.75 million in the U.S.[17][9]

Classification

[edit]Types of powertrain

[edit]

Hybrid electric vehicles can be classified according to the way in which power is supplied to the drivetrain:

- In parallel hybrids, the ICE and the electric motor are both connected to the mechanical transmission and can simultaneously transmit power to drive the wheels, usually through a conventional transmission. Honda's Integrated Motor Assist (IMA) system as found in the Insight, Civic, Accord, as well as the GM Belted Alternator/Starter (BAS Hybrid) system found in the Chevrolet Malibu hybrids are examples of production parallel hybrids.[19] The internal combustion engine of many parallel hybrids can also act as a generator for supplemental recharging. As of 2013[update], commercialized parallel hybrids use a full size combustion engine with a single, small (<20 kW) electric motor and small battery pack as the electric motor is designed to supplement the main engine, not to be the sole source of motive power from launch. But after 2015 parallel hybrids with over 50 kW are available, enabling electric driving at moderate acceleration. Parallel hybrids are more efficient than comparable non-hybrid vehicles especially during urban stop-and-go conditions where the electric motor is permitted to contribute,[19] and during highway operation.

- In series hybrids, only the electric motor drives the drivetrain, and a smaller ICE (also called range extender) works as a generator to power the electric motor or to recharge the batteries. They also usually have a larger battery pack than parallel hybrids, making them more expensive. Once the batteries are low, the small combustion engine can generate power at its optimum settings at all times, making them more efficient in extensive city driving.[19]

- Power-split hybrids have the benefits of a combination of series and parallel characteristics. As a result, they are more efficient overall, because series hybrids tend to be more efficient at lower speeds and parallel tend to be more efficient at high speeds; however, the cost of power-split hybrid is higher than a pure parallel.[19] Examples of power-split (referred to by some as "series-parallel") hybrid powertrains include 2007 models of Ford, General Motors, Lexus, Nissan, and Toyota.[19][20]

In each of the hybrids above it is common to use regenerative braking to recharge the batteries.

Type of hybridization

[edit]- Full hybrid, sometimes also called a strong hybrid, is a vehicle that can run entirely on its electric motor for a period of time.[21] Ford's hybrid system, Toyota's Hybrid Synergy Drive, Peugeot-Citroën's HYbrid4 and General Motors/Chrysler's Two-Mode Hybrid technologies are full hybrid systems.[22] The Toyota Prius, Peugeot 508 RXH HYbrid4, Ford Escape Hybrid, and Ford Fusion Hybrid are examples of full hybrids, as these cars can be moved forward on battery power alone. A large, high-capacity battery pack is needed for battery-only operation. These vehicles have a split power path allowing greater flexibility in the drivetrain by interconverting mechanical and electrical power, at some cost in complexity.

- Mild hybrid, is a vehicle that cannot be driven solely on its electric motor, because the electric motor does not have enough power to propel the vehicle on its own.[21][22] Mild hybrids include only some of the features found in hybrid technology, and usually achieve limited fuel consumption savings, up to 15 percent in urban driving and 8 to 10 percent overall cycle.[21][22] A mild hybrid is essentially a conventional vehicle with oversize starter motor, allowing the engine to be turned off whenever the car is coasting, braking, or stopped, yet restart quickly and cleanly. The motor is often mounted between the engine and transmission, taking the place of the torque converter, and is used to supply additional propulsion energy when accelerating. Accessories can continue to run on electrical power while the petrol engine is off, and as in other hybrid designs, the motor is used for regenerative braking to recapture energy. As compared to full hybrids, mild hybrids have smaller batteries and a smaller, weaker motor/generator, which allows manufacturers to reduce cost and weight.[22] Honda's early hybrids including the first generation Insight used this design,[22] leveraging their reputation for design of small, efficient petrol engines; their system is dubbed Integrated Motor Assist (IMA). Starting with the 2006 Civic Hybrid, the IMA system now can propel the vehicle solely on electric power during medium speed cruising. Another example is the 2005–2007 Chevrolet Silverado Hybrid, a full-size pickup truck.[22] Chevrolet was able to get a 10% improvement on the Silverado's fuel efficiency by shutting down and restarting the engine on demand and using regenerative braking. General Motors has also used its mild BAS Hybrid technology in other models such as the Saturn Vue Green Line, the Saturn Aura Greenline, the 2008-2009 Chevrolet Malibu Hybrid and the 2013–2014 Chevrolet Malibu Eco.[22]

Plug-in hybrids (PHEVs)

[edit]

A plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV), also known as a plug-in hybrid, is a hybrid electric vehicle with rechargeable batteries that can be restored to full charge by connecting a plug to an external electric power source. A PHEV shares the characteristics of both a conventional hybrid electric vehicle, having an electric motor and an internal combustion engine; and of an all-electric vehicle, also having a plug to connect to the electrical grid. PHEVs have a much larger all-electric range as compared to conventional petrol-electric hybrids, and also eliminate the "range anxiety" associated with all-electric vehicles, because the combustion engine works as a backup when the batteries are depleted.[21][23][24]

Flex-fuel hybrid

[edit]

In December 2018, Toyota do Brasil announced the development of the world's first commercial hybrid electric car with flex-fuel engine capable of running with electricity and ethanol fuel or petrol. The flexible fuel hybrid technology was developed in partnership with several Brazilian federal universities, and a prototype was tested for six months using a Toyota Prius as development mule.[25] Toyota announced plans to start series production of a flex hybrid electric car for the Brazilian market in the second half of 2019.[25][26]

The twelfth generation of the Corolla line-up was launched in Brazil in September 2019, which included an Altis trim with the first version of a flex-fuel hybrid powered by a 1.8-litre Atkinson engine.[27] By February 2020, sales of the Corolla Altis flex-fuel hybrid represented almost 25% of all Corolla sales in the country.[28]

Energy Management Systems

[edit]To take advantage of the emission reduction potential of hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), appropriate design of their energy management systems (EMSs) to control the power flow between the engine and the battery is essential.[29]

In a conventional (non-hybrid) vehicle, there is no need for an energy management strategy: the driver decides the instant power delivery using the brake and accelerator pedals and, in manual transmission vehicles, decides which gear is engaged at any time. In a hybrid vehicle, on the other hand, there is an additional decision that must be taken due to its ability to recover energy during braking or driving downhill: how much power is delivered by each of the energy sources on-board of the vehicle. The recovered energy can be stored in the battery and deployed at a later time to assist the prime mover to provide tractive power. This is why all hybrid vehicles include an energy management controller, interposed between the driver and the component controllers. As mentioned, the aim of the energy management system is to determine the optimal power split between the on-board energy sources. The decision regarding what to consider optimal depends on the specific application: in most cases, the strategies tend to minimize the fuel consumption, but optimization objectives could also include the minimization of pollutant emissions, maximization of battery life or—in general—a compromise among all the above goals.[30]

History

[edit]Early days

[edit]

William H. Patton filed a patent application for a petrol-electric hybrid rail-car propulsion system in early 1889, and for a similar hybrid boat propulsion system in mid-1889.[31][32] He went on to test and market the Patton Motor Car, a gas-electric hybrid system used to drive tram cars and small locomotives. A petrol engine drove a generator that served to charge a lead acid battery in parallel with the traction motors. A conventional series-parallel controller was used for the traction motors. A prototype was built in 1889, an experimental tram car was run in Pullman, Illinois, in 1891, and a production locomotive was sold to a street railway company in Cedar Falls, Iowa, in 1897.[33][34]

In 1896, the Armstrong Phaeton was developed by Harry E. Dey and built by the Armstrong Company of Bridgeport, CT for the Roger Mechanical Carriage Company. Though there were steam, electric, and internal combustion vehicles introduced in the early days, the Armstrong Phaeton was innovative with many firsts. Not only did it have a petrol powered 6.5-litre, two-cylinder engine, but also a dynamo flywheel connected to an onboard battery. The dynamo and regenerative braking were used to charge the battery. Its electric starter was used 16 years before Cadillac's. The dynamo also provided ignition spark and powered the electric lamps. The Phaeton also had the first semi-automatic transmission (no manual clutch). The exhaust system was an integrated structural component of the vehicle. The Armstrong Phaeton's motor was too powerful; the torque damaged the carriage wheels repeatedly.[35]

In 1900, while employed at Lohner Coach Factory, Ferdinand Porsche developed the Mixte,[3][36] a 4WD series-hybrid version of "System Lohner–Porsche" electric carriage that previously appeared in 1900 Paris World Fair.[3][37] George Fischer sold hybrid buses to England in 1901; Knight Neftal produced a racing hybrid in 1902.[38]

In 1905, Henri Pieper of Germany/Belgium introduced a hybrid vehicle with an electric motor/generator, batteries, and a small petrol engine. It used the electric motor to charge its batteries at cruise speed and used both motors to accelerate or climb a hill. The Pieper factory was taken over by Impéria, after Pieper died.[39] The 1915 Dual Power, made by the Woods Motor Vehicle electric car maker, had a four-cylinder ICE and an electric motor. Below 15 mph (24 km/h) the electric motor alone drove the vehicle, drawing power from a battery pack, and above this speed the "main" engine cut in to take the car up to its 35 mph (56 km/h) top speed. About 600 were made up to 1918.[40] The Woods hybrid was a commercial failure, proving to be too slow for its price, and too difficult to service. In England, the prototype Lanchester petrol-electric car was made in 1927. It was not a success, but the vehicle is on display in Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum.[41][42] The United States Army's 1928 Experimental Motorized Force tested a petrol-electric bus in a truck convoy.[citation needed]

In 1931, Erich Gaichen invented and drove from Altenburg to Berlin a 1/2 horsepower electric car containing features later incorporated into hybrid cars. Its maximum speed was 25 miles per hour (40 km/h), but it was licensed by the Motor Transport Office, taxed by the German Revenue Department and patented by the German Reichs-Patent Amt. The car battery was re-charged by the motor when the car went downhill. Additional power to charge the battery was provided by a cylinder of compressed air which was re-charged by small air pumps activated by vibrations of the chassis and the brakes and by igniting oxyhydrogen gas. No production beyond the prototype was reported.[citation needed]

During the Second World War, Ferdinand Porsche sought to use his firm's experience in hybrid drivetrain design for powering armoured fighting vehicles for Nazi Germany. A series of designs, starting with the VK 3001 (P), the unsuccessful VK 4501 (P) heavy tank prototype (which became the Elefant tank destroyer) and concluding with the heaviest armoured fighting vehicle ever prototyped, the Panzerkampfwagen Maus of nearly 190 tonnes in weight, were just two examples of a number of planned Wehrmacht "weapons systems" (including the highly-"electrified" subsystems on the Fw 191 bomber project), crippled in their development by the then-substandard supplies of electrical-grade copper, required for the electric final drives on Porsche's armoured fighting vehicle powertrain designs.[citation needed]

Predecessors of present technology

[edit]The regenerative braking system, a core design concept of most modern production HEVs, was developed in 1967 for the American Motors Amitron and called Energy Regeneration Brake by AMC.[43] This completely battery powered urban concept car was recharged by braking, thus increasing the range of the automobile.[44] The AMC Amitron was first use of regenerative braking technology in the U.S.[45]

A more recent working prototype of the HEV was built by Victor Wouk (one of the scientists involved with the Henney Kilowatt, the first transistor-based electric car) and Dr. Charles L Rosen. Wouk's work with HEVs in the 1960s and 1970s earned him the title as the "Godfather of the Hybrid".[46] They installed a prototype hybrid drivetrain (with a 16-kilowatt (21 hp) electric motor) into a 1972 Buick Skylark provided by GM for the 1970 Federal Clean Car Incentive Program, but the program was stopped by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1976 while Eric Stork, the head of the EPA's vehicle emissions control program at the time, was accused of a prejudicial coverup.[47]

In 1979 the Fiat 131 Ibrido was presented in Detroit,[48][49] a marching prototype made by the CRF (Fiat Research Center). The engine compartment was composed by the 903cc borrowed from the Fiat 127, set to output 33 hp only and coupled to a 20 kW electric motor. The scheme proposed by Fiat is defined as "parallel hybrid": the petrol engine is connected to the differential with a 1:1 direct gear ratio, without gearbox, instead of the clutch there was an 8-inch torque converter followed by the transmission shaft on which the rotor of the electric motor is keyed, the latter powered by a 12-batteries pack.

The regenerative brake concept was further developed in the early 1980s by David Arthurs, an electrical engineer, using off-the shelf components, military surplus, and an Opel GT.[50] The voltage controller to link the batteries, motor (a jet-engine starter motor), and DC generator was Arthurs'. The vehicle exhibited 75 miles per US gallon (3.1 L/100 km; 90 mpg‑imp) fuel efficiency, and plans for it were marketed by Mother Earth News.[51]

In 1982, Fritz Karl Preikschat invented an electric propulsion and braking system for cars based on regenerative braking.[52] While clearly not the only patent relating to the hybrid electric vehicle, the patent was important based on 120+ subsequent patents directly citing it.[52] The patent was issued in the U.S. and the system was not prototyped or commercialized.

In 1988, Alfa Romeo built three prototypes of the Alfa 33 Hybrid,[53] equipped with the tried and tested Alfasud boxer engine (1,500cc, 95 HP) combined with a three-phase asynchronous electric motor (16 HP, 6.1 kgm of torque) supplied by Ansaldo of Genoa. The design was realistic and already mass production-oriented, with minimal modifications to the standard body and a weight increase of only 150 kg (110 for the batteries, 20 for the electric engine and 10 for power electronics). The Alfa Romeo 33 Ibrida was able to travel up to 60 km/h in full electric mode, with a 5 km range, very good performance for the time.

In 1989, Audi produced its first iteration of the Audi Duo (the Audi C3 100 Avant Duo) experimental vehicle, a plug-in parallel hybrid based on the Audi 100 Avant quattro. This car had a 9.4 kilowatts (12.8 PS; 12.6 bhp) Siemens electric motor which drove the rear roadwheels. A trunk-mounted nickel–cadmium battery supplied energy to the motor that drove the rear wheels. The vehicle's front road wheels were powered by a 2.3-litre five-cylinder petrol engine with an output of 100 kilowatts (136 PS; 134 bhp). The intent was to produce a vehicle which could operate on the engine in the country, and electric mode in the city. Mode of operation could be selected by the driver. Just ten vehicles are believed to have been made; one drawback was that due to the extra weight of the electric drive, the vehicles were less efficient when running on their engines alone than standard Audi 100s with the same engine.[citation needed]

Two years later, Audi, unveiled the second duo generation, the Audi 100 Duo – likewise based on the Audi 100 Avant quattro. Once again, this featured an electric motor, a 21.3 kilowatts (29.0 PS; 28.6 bhp) three-phase machine, driving the rear roadwheels. This time, however, the rear wheels were additionally powered via the Torsen centre differential from the main engine compartment, which housed a 2.0-litre four-cylinder engine.[citation needed]

Research and Development was advancing in the 1990s with projects such as the early BMW 5 Series (E34) CVT hybrid-electric vehicle [54] In 1992, Volvo ECC was developed by Volvo. The Volvo ECC was built on the Volvo 850 platform. In contrast to most production hybrids, which use a petrol piston engine to provide additional acceleration and to recharge the battery storage, the Volvo ECC used a gas turbine engine to drive the generator for recharging.

The Clinton administration initiated the Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles (PNGV) program on 29 September 1993, that involved Chrysler, Ford, General Motors, USCAR, the DoE, and other various governmental agencies to engineer the next efficient and clean vehicle.[55] The United States National Research Council (USNRC) cited automakers' moves to produce HEVs as evidence that technologies developed under PNGV were being rapidly adopted on production lines, as called for under Goal 2. Based on information received from automakers, NRC reviewers questioned whether the "Big Three" would be able to move from the concept phase to cost effective, pre-production prototype vehicles by 2004, as set out in Goal 3.[56] The program was replaced by the hydrogen-focused FreedomCAR initiative by the George W. Bush administration in 2001,[57] an initiative to fund research too risky for the private sector to engage in, with the long-term goal of developing effectively carbon emission- and petroleum-free vehicles.

1998 saw the Esparante GTR-Q9 became the first Petrol-Electric Hybrid to race at Le Mans, although the car failed to qualify for the main event. The car managed to finished second in class at Petit Le Mans the same year.

Modern hybrids

[edit]

This section may be too long and excessively detailed. (August 2021) |

Automotive hybrid technology became widespread beginning in the late 1990s. The first mass-produced hybrid vehicle was the Toyota Prius, launched in Japan in 1997, and followed by the Honda Insight, launched in 1999 in the United States and Japan.[5] The Prius was launched in Europe, North America and the rest of the world in 2000.[59] The first-generation Prius sedan has an estimated fuel economy of 52 miles per US gallon (4.5 L/100 km; 62 mpg‑imp) in the city and 45 miles per US gallon (5.2 L/100 km; 54 mpg‑imp) in highway driving. The two-door first-generation Insight was estimated at 61 miles per US gallon (3.9 L/100 km; 73 mpg‑imp) in city driving and 68 miles per US gallon (3.5 L/100 km; 82 mpg‑imp) on the highway.[5]

The Toyota Prius sold 300 units in 1997 and 19,500 in 2000, and cumulative worldwide Prius sales reached the one million mark in April 2008.[59] By early 2010, the Prius global cumulative sales were estimated at 1.6 million units.[60][61] Toyota launched a second-generation Prius in 2004 and a third in 2009.[62] The 2010 Prius has an estimated U.S. Environmental Protection Agency combined fuel economy cycle of 50 miles per US gallon (4.7 L/100 km; 60 mpg‑imp).[62][63]

The Audi Duo III was introduced in 1997, based on the Audi B5 A4 Avant, and was the only Duo to ever make it into series production.[3] The Duo III used the 1.9-litre Turbocharged Direct Injection (TDI) diesel engine, which was coupled with a 21 kilowatts (29 PS; 28 bhp) electric motor. Due to low demand for it because of its high price,[clarification needed] only about sixty Audi Duos were produced. Until the release of the Audi Q7 Hybrid in 2008, the Duo was the only European hybrid ever put into production.[3][64]

The Honda Civic Hybrid was introduced in February 2002 as a 2003 model, based on the seventh-generation Civic.[65] The 2003 Civic Hybrid appears identical to the non-hybrid version, but delivers 50 miles per US gallon (4.7 L/100 km; 60 mpg‑imp), a 40 percent increase compared to a conventional Civic LX sedan.[65] Along with the conventional Civic, it received a styling update for 2004. The redesigned 2004 Toyota Prius (second generation) improved passenger room, cargo area, and power output, while increasing energy efficiency and reducing emissions. The Honda Insight first generation stopped being produced after 2006 and has a devoted base of owners. A second-generation Insight was launched in 2010. In 2004, Honda also released a 6-cylinder hybrid version of the Accord but discontinued it in 2007, citing disappointing sales, although production of a 4-cylinder hybrid began in 2012.[66]

The Ford Escape Hybrid, the first hybrid electric sport utility vehicle (SUV), was released in 2005. Toyota and Ford entered into a licensing agreement in March 2004 allowing Ford to use 20 patents[citation needed] from Toyota related to hybrid technology, although Ford's engine was independently designed and built.[citation needed] In exchange for the hybrid licenses, Ford licensed patents involving their European diesel engines to Toyota.[citation needed] Toyota announced calendar year 2005 hybrid electric versions of the Toyota Highlander Hybrid and Lexus RX 400h with 4WD-i, which uses a rear electric motor to power the rear wheels, negating the need for a transfer case.

In 2006, General Motors Saturn Division began to market a mild parallel hybrid, the 2007 Saturn Vue Green Line, which utilized GM's Belted Alternator/Starter (BAS Hybrid) system combined with a 2.4-litre L4 engine and an FWD automatic transmission. The same hybrid powertrain was also used to power the 2008 Saturn Aura Green Line and Malibu Hybrid models. As of December 2009[update], only the BAS-equipped Malibu is still in (limited) production.

In 2007, Lexus released a hybrid electric version of their GS sport sedan, the GS 450h, with a power output of 335 bhp.[67] The 2007 Camry Hybrid became available in summer 2006 in the United States and Canada. Nissan launched the Altima Hybrid with technology licensed by Toyota in 2007.[68]

Commencing in fall 2007, General Motors began to market their 2008 Two-Mode Hybrid models of their GMT900-based Chevrolet Tahoe and GMC Yukon SUVs, closely followed by the 2009 Cadillac Escalade Hybrid[69] version.[70] For the 2009 model year, General Motors released the same technology in their half-ton pickup truck models, the 2009 Chevrolet Silverado[71] and GMC Sierra[72] Two-Mode Hybrid models.

The Ford Fusion Hybrid officially debuted at the Greater Los Angeles Auto Show in November 2008,[73] and was launched to the U.S. market in March 2009, together with the second-generation Honda Insight and the Mercury Milan Hybrid.[58]

Latest developments

[edit]

This section may be too long and excessively detailed. (August 2021) |

- 2009–2010

The Hyundai Elantra LPI Hybrid was unveiled at the 2009 Seoul Motor Show, and sales began in the South Korean domestic market in July 2009. The Elantra LPI (Liquefied Petroleum Injected) is the world's first hybrid vehicle to be powered by an internal combustion engine built to run on liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) as a fuel. The Elantra PLI is a mild hybrid and the first hybrid to adopt advanced lithium polymer (Li–Poly) batteries.[75][76] The Elantra LPI Hybrid delivers a fuel economy rating of 41.9 miles per US gallon (5.61 L/100 km; 50.3 mpg‑imp) and CO2 emissions of 99 g/km to qualify as a Super Ultra Low Emission Vehicle (SULEV).[75]

The Mercedes-Benz S400 BlueHybrid was unveiled in the 2009 Chicago Auto Show,[77] and sales began in the U.S. in October 2009.[78][79] The S400 BlueHybrid is a mild hybrid and the first hybrid car to adopt a lithium-ion battery.[77][80] The hybrid technology in the S400 was co-developed by Daimler AG and BMW.[22][77] The same hybrid technology is being used in the BMW ActiveHybrid 7, expected to go on sales in the U.S. and Europe by mid-2010.[81] In December 2009 BMW began sales of its full hybrid BMW ActiveHybrid X6, while Daimler launched the Mercedes-Benz ML450 Hybrid by lease only.[82][83]

Sales of the Honda CR-Z began in Japan in February 2010, followed by the U.S. and European markets later in the year, becoming Honda's third hybrid electric car in the market.[74][85] Honda also launched the 2011 Honda Fit Hybrid in Japan in October 2010, and unveiled the European version, the Honda Jazz Hybrid, at the 2010 Paris Motor Show, which went on sale in some European markets by early 2011.[86]

Mass production of the 2011 Toyota Auris Hybrid began in May 2010 at Toyota Manufacturing UK (TMUK) Burnaston plant and became the first mass-produced hybrid vehicle to be built in Europe.[84] Sales in the UK began in July 2010, at a price starting at£18,950 (US$27,450), £550 (US$800) less than the Toyota Prius.[87][88] The 2011 Auris Hybrid shares the same powertrain as the Prius, and combined fuel economy is 74.3 mpg‑imp (3.80 L/100 km; 61.9 mpg‑US).[89][90]

The 2011 Lincoln MKZ Hybrid was unveiled at the 2010 New York International Auto Show[91] and sales began in the U.S. in September 2010.[92] The MKZ Hybrid is the first hybrid version ever to have the same price as the petrol-engine version of the same car.[93] The Porsche Cayenne Hybrid was launched in the U.S. in late 2010.[94]

- 2011–2015

Volkswagen announced at the 2010 Geneva Motor Show the launch of the 2012 Touareg Hybrid, which went on sale on the U.S. in 2011.[95][96] VW also announced plans to introduce diesel-electric hybrid versions of its most popular models in 2012, beginning with the new Jetta, followed by the Golf Hybrid in 2013 together with hybrid versions of the Passat.[97][98] Other petrol-electric hybrids released in the U.S. in 2011 were the Lexus CT 200h, the Infiniti M35 Hybrid, the Hyundai Sonata Hybrid and its sibling the Kia Optima Hybrid.[99][100]

The Peugeot 3008 HYbrid4 was launched in the European market in 2012, becoming the world's first production diesel-electric hybrid. According to Peugeot the new hybrid delivers a fuel economy of up to 62 miles per US gallon (3.8 L/100 km; 74 mpg‑imp) and CO2 emissions of 99g/km on the European test cycle.[101][102]

The Toyota Prius v, launched in the U.S. in October 2011, is the first spinoff from the Prius family. Sales in Japan began in May 2011 as the Prius Alpha. The European version, named Prius +, was launched in June 2012.[103] The Prius Aqua was launched in Japan in December 2011, and was released as the Toyota Prius c in the U.S. in March 2012.[104] The Prius c was launched in Australia in April 2012.[105] The production version of the 2012 Toyota Yaris Hybrid went on sale in Europe in June 2012.[106]

Other hybrids released in the U.S. during 2012 are the Audi Q5 Hybrid, BMW 5 Series ActiveHybrid, BMW 3 series Hybrid, Ford C-Max Hybrid, Acura ILX Hybrid. Also during 2012 were released the next generation of Toyota Camry Hybrid and the Ford Fusion Hybrid, both of which offer significantly improved fuel economy in comparison with their previous generations.[107][108][109] The 2013 models of the Toyota Avalon Hybrid and the Volkswagen Jetta Hybrid were released in the U.S. in December 2012.[110]

Global sales of the Toyota Prius liftback passed the 3 million milestone in June 2013. The Prius liftback is available in almost 80 countries and regions, and it is the world's best-selling hybrid electric vehicle.[111] Toyota released the hybrid versions of the Corolla Axio sedan and Corolla Fielder station wagon in Japan in August 2013. Both cars are equipped with a 1.5-litre hybrid system similar to the one used in the Prius c.[112]

Sales of the Honda Vezel Hybrid SUV began in Japan began in December 2013.[113] The Range Rover Hybrid diesel-powered electric hybrid was unveiled at the 2013 Frankfurt Motor Show, and retail deliveries in Europe are slated to start in early 2014.[114] Ford Motor Company, the world's second largest manufacturer of hybrids after Toyota Motor Corporation, reached the milestone of 400,000 hybrid electric vehicles produced in November 2014.[115] After 18 years since the introduction of hybrid cars, Japan became in 2014 the first country to reach sales of over 1 million hybrid cars in a single year, and also the Japanese market surpassed the United States as the world's largest hybrid market.[116][117]

The redesigned and more efficient fourth generation Prius was released for retail customers in Japan in December 2015. The 2016 model year Prius Eco surpassed the 2000 first generation Honda Insight as the all-time EPA-rated most fuel efficient petrol-powered car available in the U.S. without plug-in capability.[118][119][120] In late 2017 Chevy introduced the Chevy ZH2 that runs on hydrogen fuel cells. The ZH2 was built especially for the U.S.

Sales and rankings

[edit]This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (December 2023) |

As of April 2020[update], more than 17 million hybrid electric vehicles have been sold worldwide since their inception in 1997.[8][9] Japan ranks as the market leader with more than 7.5 million hybrids sold as of March 2018[update],[10] followed by the United States with cumulative sales of 5.4 million units through 2019[121] while 3.0 million hybrid cars had been sold in Europe by July 2020.[13] Hybrid sales in the rest of the world totaled over 500,000 units by April 2016.[9] As of August 2014[update], more than 130,000 hybrids have been sold in Canada, of which, over 100,000 are Toyota and Lexus models.[122] In Australia, over 50,000 Lexus and Toyota models have been sold through February 2014.[123][124]

As of January 2020[update], global hybrid sales led by Toyota Motor Company (TMC) with over 15 million Lexus and Toyota hybrids sold;[8] followed by Honda Motor Co., Ltd. with cumulative global sales of more than 1.35 million hybrids as of June 2014[update];[14][15][16] Ford Motor Corporation with over 424,000 hybrids sold in the United States through June 2015, of which, around 10% are plug-in hybrids;[125][110][126][127][128] Hyundai Group with cumulative global sales of 200,000 hybrids as of March 2014[update], including both Hyundai Motors and Kia Motors hybrid models;[129] and PSA Peugeot Citroën with over 50,000 diesel-powered hybrids sold in Europe through December 2013.[130]

TMC experienced record sales of hybrid cars during 2013, with 1,279,400 units sold worldwide, and it took nine months to achieve one million hybrid sales.[131][132] Again in 2014, TMC sold a record one million hybrids in nine months.[133] Toyota hybrids combined with Lexus models reached 1 million units in May 2007,[134] and the U.S. reached the 1 million mark of sales of both brands by February 2009.[135] Worldwide sales of TMC hybrids totaled over 2 million vehicles by August 2009,[134] 3 million units by February 2011,[136] 5 million in March 2013,[137] 7 million in September 2014,[133] and the 8 million mark in July 2015.[138] The 9 million sales mark was reached in April 2016, again, selling one million hybrids in just ninth months,[139] and the 10 million milestone in January 2017, achieved one more time just nine months after the previous million.[17] TMC achieved the 15 million sales milestone in January 2020.[8]

Ford experienced record sales of its hybrids models in the U.S. during 2013, with almost 80,000 units sold, almost triple the 2012 total.[140] During the second quarter of 2013 Ford achieved its best hybrid sales quarter ever, up 517% over the same quarter of 2012.[141] In 2013 Toyota's hybrid market share in the U.S. declined from 2012 totals due to new competition, particularly from Ford with the arrival of new products such as the C-Max Hybrid and the new styling of the Fusion. Except for the Prius c, sales of the other models of the Prius family and the Camry Hybrid suffered a decline from 2012, while the Fusion Hybrid experienced a 164.3% increase from 2012, and C-Max Hybrid sales climbed 156.6%.[126] During 2013 Ford increased its market share of the American hybrid market from 7.5% in 2012 to 14.7% in 2013.[126][142]

As of January 2017[update], global hybrid sales are led by the Prius family, with cumulative sales of 6.0361 million units (excluding plug-in hybrids) representing 60% of the 10 million hybrids sold worldwide by Toyota and Lexus since 1997.[17] As of January 2017[update], the Toyota Prius liftback is the leading model of the Toyota brand with cumulative sales of 3.985 million units. Ranking second is the Toyota Aqua/Prius c, with global sales of 1.380 million units, followed by the Prius v/α/+ with 671,200, the Camry Hybrid with 614,700 units, the Toyota Auris with 378,000 units, and the Toyota Yaris Hybrid with 302,700.[17] U.S. sales of the Toyota Prius reached the 1.0 million milestone in early April 2011,[143] and cumulative sales of the Prius in Japan exceeded the 1 million mark in August 2011.[144] As of January 2017[update], sales of the Prius liftback totaled over 1.8 million units in Japan and 1.75 million in the United States, ranking as the all-time best-selling hybrid car in both countries.[17][9]

Global sales of Lexus brand hybrid vehicles worldwide reached the 500,000 mark in November 2012.[145] The 1 million sales milestone was achieved in March 2016.[18] The Lexus RX 400h/RX 450h ranks as the top-selling Lexus hybrid with 363,000 units delivered worldwide as of January 2017[update], followed by the Lexus CT 200h with 290,800 units, and the Lexus ES 300h with 143,200 units.[17]

Annual sales in top markets

[edit]| Country | Number of hybrids sold or registered by year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008[146] | 2007[147] | ||

| 633,200(1)[139] | Over 1 million[116] | 679,100(1)[148] | 678,000(1)[149] | 316,300(1)[149] | 392,200(1)[149] | 334,000[150] | 94,259 | 69,015 | ||

| 384,404[151] | 452,152[127] | 495,771[127] | 434,498[110] | 268,752[152] | 274,210[153] | 290,271[153] | 312,386[153] | 352,274[153] | ||

| 56,030[154] | 41,208[154] | 46,785[155] | 27,730[156] | 13,340[157] | 9,443[158] | 9,399[159] | 9,137[159] | 7,268[160] | ||

| 44,580[161] | 37,215[162] | 29,129[162] | 24,900[163] | 23,391[164] | 22,127[165] | 14,645[166] | 15,385[166] | 15,971[166] | ||

| 25,240[154] | 21,154[154] | 14,695[167] | 5,885[168] | 5,244[169] | ||||||

| 22,529[170] | 22,908[171] | 24,963[172] | 21,438[173] | 12,622[174] | 10,661[175] | 8,374[175] | 6,464[175] | 7,591[175] | ||

| 18,406[154] | 12,083[154] | 10,294[176] | 10,030[177] | 10,350[178] | ||||||

| 13,752[179] | 10,341[180] | 18,356[181] | 19,519[182][183] | 14,874[169] | 16,111[184] | 16,122[185] | 11,837[185] | 3,013[185] | ||

| Not available | ~15,000[186] | ~25,000[187] | Not available | 16,167[188] | 19,963[189] | 14,828 | ||||

| World | Over 1.2 million | Over 1.6 million | Over 1.3 million | Over 1.2 million | - | - | 740,000[190] | 511,758 | 500,405 | |

| Notes: (1) Partial sales, includes only Toyota/Lexus sales.[149] (2) French registrations between 2011 and 2013 include plug-in hybrids | ||||||||||

Japanese market

[edit]

Japan has the largest hybrid electric vehicle fleet in the world, as of March 2018[update], a total of 7.51 million hybrids registered in the country, excluding kei cars.[10] By 2016 it represented around 45% of cumulative global hybrid sales since their inception in 1997.[9] After 18 years since their introduction in the Japanese market, annual hybrid sales surpassed the 1 million mark for the first time in 2014. With cumulative sales of over 4 million hybrids through December 2014, Japan surpassed the United States as the world's largest hybrid market.[9][116][117] It was also the first time that all eight major Japanese manufacturers offered hybrid vehicles in their lineup.[117]

Japan also has the world's highest hybrid market penetration,[11] as of March 2018[update], hybrids represented 19.0% of all passenger cars on the road.[10] The hybrid market share of new car sales began to increase significantly in 2009, when the government implemented aggressive fiscal incentives for fuel efficient vehicles and the third generation Prius was introduced. That year, the hybrid market share of new car sales in the country, including kei cars, jumped from less than 5% in 2008 to over 10% in 2009. If only conventional passenger cars are accounted for, the hybrid market share was about 15%. By 2013 the hybrid market share accounted for more than 30% of the 2.9 million standard passenger vehicles sold, and about 20% of the 4.5 million passenger vehicles including kei cars.[194] Sales of standard cars in 2016 totaled 1.49 million units, with the hybrid segment achieving a record 38% market share. Accounting for kei cars, hybrids achieved a market share of 25.7% of new passenger car sales, up from 22.3% in 2015.[11] In 2016 every one of the standard cars listed in the Japanese top-20 best-selling car ranking had a hybrid version on sale.[11] and the two top-selling standard cars were models available only as a hybrid, the Toyota Prius and the Toyota Aqua.[195]

Toyota's hybrid sales in Japan since 1997, including both Toyota and Lexus models, passed the 1 million mark in July 2010,[196] 2 million in October 2012,[197] and topped the 3 million mark in March 2014.[123] As of January 2017[update], TMC hybrid sales in the country totaled 4,853,000 vehicles, of which, only 4,900 units are commercial vehicles.[17][198] Cumulative sales of the original Prius in Japan reached the 1 million mark in August 2011.[144] Sales of the Prius family vehicles totaled 3,435,800 units through January 2017.[17] The Prius liftback is the top-selling model with 1,812,800 units, followed by the Aqua with 1,154,500 units, the Prius α with 446,400, and the Prius plug-in with 22,100.[17] Cumulative sales of Honda's hybrid vehicles since November 1999 reached 25,239 units by January 2009,[199] and in March 2010, Honda announced that the new 2010 Insight broke through 100,000 sales in Japan in just one year after its introduction.[200]

Hybrid sales in Japan almost tripled in 2009 as compared to 2008 as a result of government incentives that included a scrappage program, tax breaks on hybrid vehicles and other low-emission cars and trucks, and a higher levy on petrol that rose prices in the order of US$4.50.[60][190][201] New hybrid car sales jumped from 94,259 in 2008[146] to 334,000 in 2009,[150] and hybrid sales in 2009 represented around 10% of new vehicles sales in Japan. In contrast, the U.S. market share was 2.8% for the same year.[60] These record sales allowed Japan to surpass the U.S. in total new hybrid sales, with the Japanese market representing almost half (48%) of the worldwide hybrid sales in 2009 while the U.S. market represented 42% of global sales.[150] The Toyota Prius became the first hybrid to top annual new car sales in Japan with 208,876 units sold in 2009.[60][202] The Insight ranked fifth in overall sales in 2009 with 93,283 units sold.[60]

A total of 315,669 Priuses were sold domestically in 2010, making the Prius the country's best-selling vehicle for the second straight year. Also the Prius broke Japan's annual sales record for a single model for the first time in 20 years, surpassing the Toyota Corolla, which in 1990 set the previous sales record with 300,008 units.[203] The Prius sold 252,528 units in 2011, becoming the best-selling vehicle for the third-consecutive year. This figure includes sales of the Prius α, launched in May 2011, and the Toyota Aqua, launched in December. Despite keeping to the top-selling spot, total Prius sales for 2011 were 20% lower than 2010 due partly to the disruptions caused by the March 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, and also because government incentives for hybrid cars were scaled back.[204][205] Nevertheless, during the 2011 Japanese fiscal year (April 1, 2011 through March 31, 2012), hybrid vehicles accounted for 16% of all new car sales in the country.[206] In May 2012, hybrid sales reached a record market share of 19.7% of new car sales in the country, including kei cars. Sales were led by the conventional Prius followed by the Toyota Aqua. Also during this month, hybrid sales represented 25% of Honda sales and 46% of Toyota sales in the country.[207]

The Toyota Aqua, released in December 2011, ranked as the second top-selling new car in Japan in 2012 after the conventional Prius.[208] Totaling 262,367 units sold in 2013, the Aqua topped new car sales in Japan in 2013, including kei car sales.[191] And with 233,209 units sold during 2014, down 11.1% from 2013, the Aqua was the top-selling new car in Japan for the second consecutive year.[192] Again in 2015, with 215,525 units sold, down 7.6% from 2014, the Aqua ranked as the top-selling new car in Japan.[193] The Toyota Aqua not only was the best-selling new car in Japan for three years running, from 2013 to 2015,[191][192][193] but it is considered the most successful nameplate launch in the Japanese market of the last 20 years.[209] In the first quarter of 2016, the Prius liftback surpassed the Aqua as the best-selling new car,[210] the Prius ended 2016 as the best-selling standard car in the Japanese market with 248,258 units, followed by the Aqua with 168,208 units.[195][211]

American market

[edit]

The market of hybrid electric vehicles in the United States is the second largest in the world after Japan[9] with cumulative sales of 5.4 million units through December 2019.[121] The 3 million mark was achieved in October 2013, and 4 million in April 2016.[9][214] Sales of hybrid vehicles in the U.S. began to decline following the 2008 financial crisis, and after a short recovery, began to decline again in 2014 due to low petrol prices, and had a small rebound in 2019.[9][127][121] Hybrid sales in the American market achieved its highest market share ever in 2013, capturing 3.19% of new carsales that year. At the end of 2015 the hybrid take rate had fallen to 2.21%, dropped to 1.99% in 2016, slightly recovered to 2.4% in 2019.[9][215][121]

Since their inception in 1999, a total of 5,374,000 hybrid electric automobiles and sport utility vehicles have been sold in the country through December 2019.[121] The Toyota Prius family is the market leader with 1,932,805 units sold through April 2016, representing a 48.0% market share of total hybrid sales.[110][126][127][151][152][153][215] The conventional Toyota Prius is the top-selling hybrid model, with 1,643,000 units sold through April 2016, accounting for 40.8% of all hybrids sold in the U.S. since inception.[9] The United States accounted for 44.7% of Toyota Motor Company global hybrid sales through April 2016.[139]

European market

[edit]

As of July 2020[update], more than 3.0 million hybrids cars have been sold in Europe since their introduction.[13][9] PSA Peugeot Citroën had sold over 50,000 diesel-powered hybrids in Europe through December 2013,[130] and Toyota and Lexus hybrids totaled 3.0 million units by July 2020.[13] In 2014, one-fourth of all new vehicles sold by Toyota in the European Union were hybrid-electric.[217] The top-selling hybrid markets in 2015 were France, followed by the UK, Italy, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, and Norway.[154]

As of December 2014[update], hybrid vehicles accounted for 1.4% of new passenger car registrations in the EU Member States, up from 1.1% in 2012.[217][218] The Netherlands is the leading country within the Union states with a market share of 3.7% of total passenger car sales in 2014, though fewer hybrid vehicles were sold in the Dutch market in 2014 than in previous years. Accounting for all countries in the continent, Norway is the segment leader, with a market share of 6.9% in 2014.[217]

Sales of hybrids in Europe went up from around 9,000 units in 2004 to 39,880 in 2006, with Toyota accounting for 91% of hybrid sales and Honda with 3,410 units sold that year. Cumulative sales of Toyota hybrids since 2000 reached 69,674 units in 2006, while Honda hybrid sales reached over 8,000 units.[219] By January 2009, Honda had sold 35,149 hybrids in Europe, of which 34,757 were Honda Civic Hybrids.[199] During 2008 combined sales of Toyota and Lexus hybrids in Europe were 57,819 units, representing 5.2% of total Toyota sales in the region. Toyota sales were led by Prius with 41,495 units.[220] Cumulative sales of the Toyota Prius reached 100,000 units in 2008 and the 200,000 mark was reached in July 2010. The UK has been one of the leading European markets for the Prius since its inception, with 20% of Prius sales in Europe by 2010.[221]

Toyota's European hybrid sales reached 70,529 vehicles in 2010, including sales of 15,237 Toyota Auris Hybrids.[222] Sales reached 84,839 units in 2011, including 59,161 Toyota and 25,678 Lexus hybrid vehicles. The Auris hybrid sold 32,725 units in 2011. Lexus hybrids made up 85% of total sales in Western Europe in 2011. Toyota and Lexus hybrids represented 10% percent of Toyota's European new car sales in 2011.[223][224] TMC share of hybrid sales out of the company's total European sales climbed from 13% in 2012 to 20% during the first 11 months of 2013.[225]

During the first nine months of 2013, over 118,000 hybrids were sold in Western Europe representing a 1.4% market share of new car sales in the region.[226] A total of 192,664 hybrid cars were sold in the European Union and EFTA countries in 2014. Sales increased 21.5% in 2015, with 234,170 units sold.[154] In 2015, petrol-powered hybrids represented 91.6% of total hybrid registrations.[227] The top-selling model in 2015 was the Toyota Auris Hybrid, with 75,810 units, up 13.0% from 2014; followed by the Yaris Hybrid with 68,902 units, up 22% from 2014. Seven of the top ten hybrids models sold in 2015 were from either Toyota or the Lexus brand.[227] Toyota achieved record hybrid sales in 2015 with 201,500 units delivered.[139] Hybrid registrations in the European Union and EFTA countries totaled 74,796 units during the first quarter of 2016, up 29.7% from the same quarter the previous year.[228]

Cumulative TMC sales since the Prius introduction in Europe in 2000 passed the one million unit milestone in November 2015.[229] As of December 2017[update], the top-selling Toyota hybrids were the Auris Hybrid (427,600), the Yaris Hybrid (388,900), and the conventional Prius (299,100).[216] The top-selling Lexus models are the Lexus RX 400h/RX 450h with 111,100 units, and the Lexus CT 200h with 78,100 units.[216] European sales of TMC hybrids totaled 3 million cars in July 2020.[13]

- UK

Since 2006 hybrid car registrations in the UK totaled 257,404 units up to April 2016, including 11,679 diesel-electric hybrids, which were introduced in 2011.[161][162][163][164][165][166][230] The market share of the British hybrid segment climbed from 1.1% in 2010, to 1.2% in 2012, and achieved 1.5% of new car registrations in 2014.[217]

Since 2000, when the Prius was launched in the UK, 100,000 Toyota hybrids had been sold by May 2014, and almost 50,000 Lexus models since the introduction of the RX 400h in 2005.[231] Honda had sold in the UK more than 22,000 hybrid cars through December 2011 since the Insight was launched in the country in 2000.[232] After 15 years since the launch of the Prius in the British market, combined sales of Toyota and Lexus hybrids reached the 200,000 unit milestone in November 2015.[233]

A total of 37,215 hybrids were registered in 2014, and while petrol-electric hybrids increased 32.6% from 2013, diesel-electric hybrids declined 12.6%.[162] Hybrid registrations totaled a record of 44,580 units in 2015, consisting of 40,707 petrol-powered hybrids and 3,873 powered by diesel; the latter experienced a 36.3% increase from 2014, while petrol-powered hybrid grew by 18.1%. The hybrid segment market shared reached 1.69% of new car registrations in the UK that year.[161]

- France

A total of 165,915 hybrid cars have been registered in France between 2007 and 2014,[155][156][157][158][159][160][234] including 33,547 diesel-powered hybrids. French registrations account plug-in hybrid together with conventional hybrids.[155][157][234] Among EU Member States, France had the second largest hybrid market share in 2014, with 2.3% of new car sales, down from 2.6% in 2013.[217]

Diesel hybrid technology, introduced by PSA Peugeot Citroën with the HYbrid4 system in 2011, represented 20.2% of the hybrid car stock sold in France between 2011 and 2014.[155][156][157][234] Among the 13,340 units registered in 2011, the top-selling models in the French market were the Toyota Auris (4,740 units), the Prius (2,429 units), and the Honda Jazz Hybrid (1,857 units). The diesel-powered Peugeot 3008 HYbrid4, launched in late 2011, sold 401 units.[157] Toyota led hybrid sales in the French market in 2013 with 27,536 registrations of its Yaris, Auris and Prius models, followed by the PSA group with 13,400 registrations.[155] During 2014, a total of 42,813 hybrid cars and vans were registered, down 8.5% from 2013. Of these, 9,518 were diesel-electric hybrids, down 31.9% from 13,986 units a year earlier, while registrations of petrol-electric hybrids were up 1.5%.[234] The top-selling models in 2014 were the Toyota Yaris Hybrid with 12,819 units, Toyota Auris with 10,595 and the Peugeot 3008 with 4,189 units.[234] Hybrid registrations in 2014 included 1,519 plug-in hybrids, with sales led by the Mitsubishi Outlander P-HEV, with 820 units.[234][235]

- The Netherlands

As of 31 December 2015[update], hybrid car registrations totaled 131,011 units, up 11.7% from 117,259 a year earlier.[179] By the end of 2009 there were about 39,300 hybrid cars registered in the Netherlands, up from 23,000 the previous year. Most of the registered hybrid cars belonged to corporate fleets due to tax incentives established in the country in 2008.[236][237] During the first eight months of 2013, around 65% of TMC cars sold in the Netherlands have been hybrids, with the technology particularly popular among fleet owners and taxi drivers.[238] Following the same market trend as in 2014, more plug-in hybrids were registered in 2015 (41,226) in the country than conventional hybrids (13,752).[179][180]

As a result of the tax incentives, the country has had for several years the highest hybrid market share among EU Member States. Hybrid sales climbed from 0.7% in 2006 and 2007 to 2.4% in 2008, and reached 4.2% in 2009. Due to the 2008 financial crisis, the market fell for two years to 2.7% in 2011, but recovered to 4.5% in 2012.[218] As fewer hybrid vehicles were sold in the Dutch market in 2014 than in previous years, the hybrid segment market share fell to 3.7% of total passenger car sales in 2014. The sales decline is due to a change in the national vehicle taxation scheme.[217] As of 2014[update], Japan (~20%) and Norway (6.9%) are the only countries with a higher market share than the Netherlands.[194][217]

- Germany

As of January 2016[update], there were 130,365 hybrid cars registered in Germany,[239] up from 85,575 on the roads on January 1, 2014,[240] and 47,642 vehicles on January 1, 2012.[241] Hybrid car registrations totaled a record of 24,963 units in 2013,[172] and declined to 22,908 in 2014,[171] and to 22,529 in 2015.[170] The German hybrid market share climbed from 0.3% in 2010, to 0.8% in 2013, and declined 0.7% of new car registrations in 2014.[217]

- Spain

A total of 10,350 hybrid cars were registered in Spain in 2011, up 22% from 2010 sales. The top-selling hybrids were the Toyota Prius, Toyota Auris HSD and the Lexus CT 200h, which together represented 83,2% of new hybrid car sales in the country.[178] During 2012 hybrid sales remained almost constant with 10,030 units sold, representing 1.44% of new passenger cars sales that year. The top-selling car was the Prius with 3,969 units, followed by the Auris HSD (2,234) and the Lexus CT 200h (1,244). Combined sales of Toyota and Lexus models represented 89.15% of hybrid sales in the Spanish market in 2012.[177] Hybrid sales in 2013 increased 1.72% from 2012, with 10,294 units registered. The Toyota Auris HSD was the top-selling hybrid with 3,644 units, followed by the Prius (2,378) and the Yaris Hybrid (1,587 ).[176]

- Republic of Ireland

As of February 2020, Hybrid cars as a proportion of all cars for sale in Ireland was very small, which could be seen in a snapshot (7 February 2020) of four car sales websites (Autotrader.ie, Carsireland.ie, Carzone.ie, and Donedeal.ie) that showed that out of circa 38,000 to 70,000 cars listed for sale, only circa 3.7% to 4.7% were Hybrids (including a small proportion of electric plug-in hybrids (PHEV)), so in real terms only 1,844-2,640 hybrid cars were advertised for sale in the market.

This very low level of Hybrids compared poorly to the circa 25,338 to 46,940 diesel engine cars available for sale on the same date, representing a much larger, circa 64-67% of the market at that time.

The Irish Government (to January 2020) had stated an aim to ban the sale of petrol, diesel and hybrid new ('non-electric') cars from 2030 (compared to the proposed EU ban by 2040, and the UK's proposed ban on the sale of new petrol, diesel and hybrid cars from 2035 as announced in the first week of February, 2020), though car dealers were reported to consider the Irish Government's target for one million electric and plug-in hybrid cars to be in use by 2030, as far too ambitious (The Irish Times, 07/02/2020).

A compromise in terms of transition to Electric Vehicles (EVs), and a non-electric car ban implementation around 2030, maybe for acceptance of Hybrid cars with modest size petrol engines (regardless of whether 'Full' or 'Mild' hybrids), for example those at/ less than 1.6Litre (1600cc) engine capacity, and/ or at circa 100g/km CO2, or less in terms of emissions, or a fuel efficiency rating (L/100 km) for Highway/Extra Urban and 'Combined' journeys.

Technology

[edit]The varieties of hybrid electric designs can be differentiated by the structure of the hybrid vehicle drivetrain, the fuel type, and the mode of operation.

In 2007, several automobile manufacturers announced that future vehicles will use aspects of hybrid electric technology to reduce fuel consumption without the use of the hybrid drivetrain. Regenerative braking can be used to recapture energy and stored to power electrical accessories, such as air conditioning. Shutting down the engine at idle can also be used to reduce fuel consumption and reduce emissions without the addition of a hybrid drivetrain. In both cases, some of the advantages of hybrid electric technology are gained while additional cost and weight may be limited to the addition of larger batteries and starter motors. There is no standard terminology for such vehicles, although they may be termed mild hybrids.

Engines and fuel sources

[edit]Petrol

[edit]Petrol engines are used in most hybrid electric designs and will likely remain dominant for the foreseeable future.[citation needed] While petroleum-derived petrol is the primary fuel, it is possible to mix in varying levels of ethanol created from renewable energy sources. Like most modern ICE powered vehicles, HEVs can typically use up to about 15% bioethanol. Manufacturers may move to flexible fuel engines, which would increase allowable ratios, but no plans are in place at present.

Diesel

[edit]The most prominent example of a full hybrid diesel system is the HYbrid4 by PSA Peugeot-Citroën. It was discontinued in 2016, following the decline in diesel popularity following the VW Dieselgate scandal. Diesel-electric HEVs use a diesel engine for power generation. Diesels have advantages when delivering constant power for long periods of time, suffering less wear while operating at higher efficiency. [citation needed] The diesel engine's high torque, combined with hybrid technology, may offer substantially improved mileage. Most diesel vehicles can use 100% pure biofuels (biodiesel), so they can use but do not need petroleum at all for fuel (although mixes of biofuel and petroleum are more common). [citation needed] If diesel-electric HEVs were in use, this benefit would likely also apply. Diesel-electric hybrid drivetrains have begun to appear in commercial vehicles (particularly buses); as of 2007[update], no light duty diesel-electric hybrid passenger cars are widely available, although prototypes exist. Peugeot was expected to produce a diesel-electric hybrid version of its 308 in late 2008 for the European market.[242]

PSA Peugeot Citroën has unveiled two demonstrator vehicles featuring a diesel-electric hybrid drivetrain: the Peugeot 307, Citroën C4 Hybride HDi and Citroën C-Cactus.[243] Volkswagen made a prototype diesel-electric hybrid car that achieved 2 L/100 km (140 mpg‑imp; 120 mpg‑US) fuel economy, but has yet to sell a hybrid vehicle. General Motors has been testing the Opel Astra Diesel Hybrid. There have been no concrete dates suggested for these vehicles, but press statements have suggested production vehicles would not appear before 2009.

At the Frankfurt Motor Show in September 2009 both Mercedes and BMW displayed diesel-electric hybrids.[244]

Robert Bosch GmbH is supplying hybrid diesel-electric technology to diverse automakers and models, including the Peugeot 308.[245]

So far, production diesel-electric engines have mostly[vague] appeared in mass transit buses.[citation needed]

FedEx, along with Eaton Corp. in the US and Iveco in Europe, has begun deploying a small fleet of Hybrid diesel electric delivery trucks.[246] As of October 2007, Fedex operates more than 100 diesel electric hybrids in North America, Asia and Europe.[247]

Human power

[edit]There are bicycles that consist of an electric motor fitted turned by a generator powered from pedals almost similar to but different from pedal only bicycles. It also combines an Electric battery to store surplus power which can be charged from regenerative braking, from battery chargers like a Battery electric vehicle or Plug-in hybrid and also from the pedal powered generator just like in an internal combustion engine vehicle that uses the engine to charge the battery. It is quite likely that such vehicles are considered hybrids since power to the electric motor is coming from two sources (i.e. pedal power via a generator and battery power).

- Liquefied petroleum gas

Hyundai introduced in 2009 the Hyundai Elantra LPI Hybrid, which is the first mass production hybrid electric vehicle to run on liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).[75]

Hydrogen

[edit]Hydrogen can be used in cars in two ways: a source of combustible heat, or a source of electrons for an electric motor. The burning of hydrogen is not being developed in practical terms; it is the hydrogen fuel-cell electric vehicle (HFEV) which is garnering all the attention. Hydrogen fuel cells create electricity fed into an electric motor to drives the wheels. Hydrogen is not burned, but it is consumed. This means molecular hydrogen, H2, is combined with oxygen to form water. 2H2 (4e−) + O2 --> 2H2O (4e−). The molecular hydrogen and oxygen's mutual affinity drives the fuel cell to separate the electrons from the hydrogen, to use them to power the electric motor, and to return them to the ionized water molecules that were formed when the electron-depleted hydrogen combined with the oxygen in the fuel cell. Recalling that a hydrogen atom is nothing more than a proton and an electron; in essence, the motor is driven by the proton's atomic attraction to the oxygen nucleus, and the electron's attraction to the ionized water molecule.

An HFEV is an all-electric car featuring an open-source battery in the form of a hydrogen tank and the atmosphere. HFEVs may also comprise closed-cell batteries for the purpose of power storage from regenerative braking, but this does not change the source of the motivation. It implies the HFEV is an electric car with two types of batteries. Since HFEVs are purely electric, and do not contain any type of heat engine, they are not hybrids.

Solar power

[edit]Some vehicles like mostly cars and occasionally other vehicles combine the solar photovoltaic cell propulsion system with an electric battery that is charged by the solar panel or sometimes like plug-in hybrid vehicles can also be charged from the power grid. These types of vehicles are technically hybrids, although they consist of two types of cells, since both of them use different fuels. The advantage of combining the two systems is that the vehicle can function with the battery if there is no sunlight and also reduces the risk of getting stuck on the road in case of a battery depletion since the solar panels charge the battery simultaneously.

Bio-fuels

[edit]

Hybrid vehicles might use an internal combustion engine running on biofuels, such as a flexible-fuel engine running on ethanol or engines running on biodiesel. In 2007 Ford produced 20 demonstration Escape Hybrid E85s for real-world testing in fleets in the U.S.[248][249] Also as a demonstration project, Ford delivered in 2008 the first flexible-fuel plug-in hybrid SUV to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), a Ford Escape Plug-in Hybrid, capable of running on petrol or E85.[250]

The Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid electric vehicle would be the first commercially available flex-fuel plug-in hybrid capable of adapting the propulsion to the biofuels used in several world markets such as the ethanol blend E85 in the U.S., or E100 in Brazil, or biodiesel in Sweden.[251][252] The Volt will be E85 flex-fuel capable about a year after its introduction.[253][254]

Design considerations

[edit]In some cases, manufacturers are producing HEVs that use the added energy provided by the hybrid systems to give vehicles a power boost, rather than significantly improved fuel efficiency compared to their traditional counterparts.[255] The trade-off between added performance and improved fuel efficiency is partly controlled by the software within the hybrid system and partly the result of the engine, battery and motor size. In the future, manufacturers may provide HEV owners with the ability to partially control this balance (fuel efficiency vs. added performance) as they wish, through a user-controlled setting.[256] Toyota announced in January, 2006 that it was considering a "high-efficiency" button.[citation needed]

Conversion kits

[edit]One can buy a stock hybrid or convert a stock petroleum car to a hybrid electric vehicle using an aftermarket hybrid kit.[257]

Environmental impact

[edit]Fuel consumption

[edit]Electric hybrids reduce petroleum consumption under certain circumstances, compared to otherwise similar conventional vehicles, primarily by using three mechanisms:[258]

- Reducing wasted energy during idle/low output, generally by turning the ICE off

- Recapturing waste energy (i.e. regenerative braking)

- Reducing the size and power of the ICE, and hence inefficiencies from under-utilization, by using the added power from the electric motor to compensate for the loss in peak power output from the smaller ICE.

Any combination of these three primary hybrid advantages may be used in different vehicles to realize different fuel usage, power, emissions, weight and cost profiles. The ICE in an HEV can be smaller, lighter, and more efficient than the one in a conventional vehicle, because the combustion engine can be sized for slightly above average power demand rather than peak power demand. The drive system in a vehicle is required to operate over a range of speed and power, but an ICE's highest efficiency is in a narrow range of operation, making conventional vehicles inefficient. On the contrary, in most HEV designs, the ICE operates closer to its range of highest efficiency more frequently. The power curve of electric motors is better suited to variable speeds and can provide substantially greater torque at low speeds compared with internal-combustion engines. The greater fuel economy of HEVs has implication for reduced petroleum consumption and vehicle air pollution emissions worldwide[259]

Many hybrids use the Atkinson cycle, which gives greater efficiency, but less power for the size of engine.

Noise

[edit]Reduced noise emissions resulting from substantial use of the electric motor at idling and low speeds, leading to roadway noise reduction,[260] in comparison to conventional petrol or diesel powered engine vehicles, resulting in beneficial noise health effects (although road noise from tires and wind, the loudest noises at highway speeds from the interior of most vehicles, are not affected by the hybrid design alone). Reduced noise may not be beneficial for all road users, as blind people or the visually impaired consider the noise of combustion engines a helpful aid while crossing streets and feel quiet hybrids could pose an unexpected hazard.[261] Tests have shown that vehicles operating in electric mode can be particularly hard to hear below 20 mph (32 km/h).[262][263]

A 2009 study conducted by the NHTSA found that crashes involving pedestrian and bicyclist have higher incidence rates for hybrids than internal combustion engine vehicles in certain vehicle maneuvers. These accidents commonly occurred on in zones with low speed limits, during daytime and in clear weather.[264]

In January 2010 the Japanese Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism issued guidelines for hybrid and other near-silent vehicles.[265] The Pedestrian Safety Enhancement Act of 2010 was approved by the U.S. Congress in December 2010,[266][267][268] and the bill was signed into law by President Barack Obama on January 4, 2011.[269] A proposed rule was published for comment by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) in January, 2013. It would require hybrids and electric vehicles traveling at less than 18.6 mph (30 km/h) to emit warning sounds that pedestrians must be able to hear over background noises.[270][271] The rules are scheduled to go into effect in September 2014.[271][272] In April 2014 the European Parliament approved legislation that requires the mandatory use of Acoustic Vehicle Alerting Systems (AVAS) for all new electric and hybrid electric vehicles, and car manufacturers have to comply within five years.[273]

As of mid-2010, and in advance of upcoming legislation, some carmakers announced their decision to address this safety issue shared by regular hybrids and all types of plug-in electric vehicles, and as a result, the Nissan Leaf and Chevrolet Volt, both launched in late 2010, and the Nissan Fuga hybrid and the Fisker Karma plug-in hybrid, both launched in 2011, include synthesized sounds to alert pedestrians, the blind and others to their presence.[274][275][276][277] Toyota introduced its Vehicle Proximity Notification System (VPNS) in the United States in all 2012 model year Prius family vehicles, including the Prius v, Prius Plug-in Hybrid and the standard Prius.[278][279]

There is also aftermarket technology available in California to make hybrids sound more like conventional combustion engine cars when the vehicle goes into the silent electric mode (EV mode).[280] In August 2010 Toyota began sales in Japan of an onboard device designed to automatically emit a synthesized sound of an electric motor when the Prius is operating as an electric vehicle at speeds up to approximately 25 kilometres per hour (16 mph). Toyota plans to use other versions of the device for use in petrol-electric hybrids, plug-in hybrids, electric vehicles as well as fuel-cell hybrid vehicles planned for mass production.[265]

Top ten EPA-rated hybrids

[edit]The following table shows the fuel economy ratings and pollution indicators for the top ten most fuel efficient hybrids rated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as of June 2016[update], for model year 2015 and 2016 available in the American market.

| Vehicle | Year model |

EPA Combined mileage (mpg) |

EPA City (mpg) |

EPA Highway (mpg) |

Annual fuel cost (1) (USD) |

Tailpipe emissions (grams per mile CO2) |

EPA Air Pollution Score(2) |

Annual Petroleum Use (barrel) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toyota Prius Eco | 2016 | 56 | 58 | 53 | US$650 | 158 | NA | 5.9 |

| Toyota Prius (4th gen) | 2016 | 52 | 54 | 50 | US$700 | 170 | NA | 6.3 |

| Toyota Prius c | 2015/16 | 50 | 53 | 46 | US$700 | 178 | 7/8* | 6.6 |

| Toyota Prius (3rd gen) | 2015 | 50 | 51 | 48 | US$700 | 179 | 7/9* | 6.6 |

| Honda Accord (2nd gen) | 2015 | 47 | 50 | 45 | US$750 | 188 | 7/8* | 7.0 |

| Chevrolet Malibu Hybrid | 2016 | 46 | 47 | 46 | US$750 | 212 | 7/8* | 7.8 |

| Honda Civic Hybrid (3rd gen) | 2015 | 45 | 44 | 47 | US$800 | 196 | 7/9* | 7.3 |

| Volkswagen Jetta Hybrid | 2015 | 45 | 42 | 48 | US$950 | 200 | 7/9* | 7.3 |

| 2016 | 44 | 42 | 48 | 7.5 | ||||

| Ford Fusion (2nd gen) | 2015/16 | 42 | 44 | 41 | US$850 | 211 | 7/9* | 7.8 |

| 2017 | 42 | 43 | 41 | 210 | 9/10 | |||

| Toyota Prius v | 2015/16 | 42 | 44 | 40 | US$850 | 211 | 7/8* | 7.8 |

| Source: U.S. Department of Energy and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency[281] Notes: (1) Estimates assumes 15,000 miles (24,000 km) per year (45% highway, 55% city) using average fuel price of US$2.34/gallon for regular petrol and US$2.57/gallon for premium petrol (national average as of 7 June 2016[update]). (2) All states except California and Northeastern states, * otherwise.[281] | ||||||||

Vehicle types

[edit]Motorcycles

[edit]Companies such as Zero Motorcycles[283] and Vectrix have market-ready all-electric motorcycles available now, but the pairing of electrical components and an internal combustion engine (ICE) has made packaging cumbersome, especially for niche brands.[284]

Also, eCycle Inc produces series diesel-electric motorcycles, with a top speed of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a target retail price of $5500.[285][286]

Peugeot HYmotion3 compressor,[287][288] a hybrid scooter is a three-wheeler that uses two separate power sources to power the front and back wheels. The back wheel is powered by a single cylinder 125 cc, 20 bhp (15 kW) single cylinder motor while the front wheels are each driven by their own electric motor. When the bike is moving up to 10 km/h only the electric motors are used on a stop-start basis reducing the amount of carbon emissions.[289]

SEMA has announced that Yamaha is going to launch one in 2010, with Honda following a year later, fueling a competition to reign in new customers and set new standards for mobility. Each company hopes to provide the capability to reach 60 miles (97 km) per charge by adopting advanced lithium-ion batteries to accomplish their claims. These proposed hybrid motorcycles could incorporate components from the upcoming Honda Insight car and its hybrid powertrain. The ability to mass-produce these items helps to overcome the investment hurdles faced by start-up brands and bring new engineering concepts into mainstream markets.[284]

Automobiles and light trucks

[edit]High-performance cars

[edit]

As emissions regulations become tougher for manufacturers to adhere to, a new generation of high-performance cars will be powered by hybrid technology (for example the Porsche GT3 hybrid racing car). Aside from the emissions benefits of a hybrid system, the immediately available torque which is produced from electric motor(s) can lead to performance benefits by addressing the power curve weaknesses of a traditional combustion engine.[290] Hybrid racecars have been very successful, as is shown by the Audi R18 and Porsche 919, which have won the 24 hours of Le Mans using hybrid technology.[citation needed]

Formula One

[edit]Since 2014, Formula One cars have used 1.6 L turbocharged V6 engines, limited to 15,000 rpm. These engines allow Formula One cars to reach speeds of 372 km/h (231 mph),[291] as recorded by Valtteri Bottas at the 2016 Mexican Grand Prix.

Taxis

[edit]

In 2000, North America's first hybrid electric taxi was put into service in Vancouver, British Columbia, operating a 2001 Toyota Prius which traveled over 332,000 km (206,000 mi) before being retired.[292][293] In 2015, a taxi driver in Austria claimed to have covered 1,000,000 km (620,000 mi) in his Toyota Prius with the original battery pack.[294]

Many of the major cities in the world are adding hybrid taxis to their taxicab fleets, led by San Francisco and New York City.[295] By 2009 15% of New York's 13,237 taxis in service are hybrids, the most in any city in North America, and also began retiring its original hybrid fleet after 300,000 and 350,000 miles (480,000 and 560,000 km) per vehicle.[295][296] Other cities where taxi service is available with hybrid vehicles include Tokyo, London, Sydney, Melbourne, and Rome.[297]

Buses

[edit]

Hybrid technology for buses has seen increased attention since recent battery developments decreased battery weight significantly. Drivetrains consist of conventional diesel engines and gas turbines. Some designs concentrate on using car engines, recent designs have focused on using conventional diesel engines already used in bus designs, to save on engineering and training costs. As of 2007[update], several manufacturers were working on new hybrid designs, or hybrid drivetrains that fit into existing chassis offerings without major re-design. A challenge to hybrid buses may still come from cheaper lightweight imports from the former Eastern bloc countries or China, where national operators are looking at fuel consumption issues surrounding the weight of the bus, which has increased with recent bus technology innovations such as glazing, air conditioning and electrical systems. A hybrid bus can also deliver fuel economy though through the hybrid drivetrain. Hybrid technology is also being promoted by environmentally concerned transit authorities.

Trucks

[edit]