Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Decompression theory

View on Wikipedia

Decompression theory is the study and modelling of the transfer of the inert gas component of breathing gases from the gas in the lungs to the tissues and back during exposure to variations in ambient pressure. In the case of underwater diving and compressed air work, this mostly involves ambient pressures greater than the local surface pressure,[1] but astronauts, high altitude mountaineers, and travellers in aircraft which are not pressurised to sea level pressure,[2][3] are generally exposed to ambient pressures less than standard sea level atmospheric pressure. In all cases, the symptoms caused by decompression occur during or within a relatively short period of hours, or occasionally days, after a significant pressure reduction.[4]

The term "decompression" derives from the reduction in ambient pressure experienced by the organism and refers to both the reduction in pressure and the process of allowing dissolved inert gases to be eliminated from the tissues during and after this reduction in pressure. The uptake of gas by the tissues is in the dissolved state, and elimination also requires the gas to be dissolved, however a sufficient reduction in ambient pressure may cause bubble formation in the tissues, which can lead to tissue damage and the symptoms known as decompression sickness, and also delays the elimination of the gas.[1]

Decompression modeling attempts to explain and predict the mechanism of gas elimination and bubble formation within the organism during and after changes in ambient pressure,[5] and provides mathematical models which attempt to predict acceptably low risk and reasonably practicable procedures for decompression in the field.[6] Both deterministic and probabilistic models have been used, and are still in use.

Efficient decompression requires the diver to ascend fast enough to establish as high a decompression gradient, in as many tissues, as safely possible, without provoking the development of symptomatic bubbles. This is facilitated by the highest acceptably safe oxygen partial pressure in the breathing gas, and avoiding gas changes that could cause counterdiffusion bubble formation or growth. The development of schedules that are both safe and efficient has been complicated by the large number of variables and uncertainties, including personal variation in response under varying environmental conditions and workload.

Physiology of decompression

[edit]

The evidence that decompression sickness is caused by bubble formation and growth within the body tissues resulting from supersaturated dissolved gas is strong, but research results also suggest that the quantity of those bubbles alone is not enough to predict whether someone will experience symptoms of DCS.[7]

Gas is breathed at ambient pressure, and some of this gas dissolves into the blood and other fluids. Inert gas continues to be taken up until the gas dissolved in the tissues is in a state of equilibrium with the gas in the lungs (see saturation diving), or the ambient pressure is reduced until the inert gases dissolved in the tissues are at a higher concentration than the equilibrium state, and start diffusing out again.[1]

The absorption of gases in liquids depends on the solubility of the specific gas in the specific liquid, the concentration of gas, customarily measured by partial pressure, and temperature.[1] In the study of decompression theory the behaviour of gases dissolved in the tissues is investigated and modeled for variations of pressure over time.[8]

Once dissolved, distribution of the dissolved gas may be by diffusion, where there is no bulk flow of the solvent, or by perfusion where the solvent (blood) is circulated around the diver's body, where gas can diffuse to local regions of lower concentration. Given sufficient time at a specific partial pressure in the breathing gas, the concentration in the tissues will stabilise, or saturate, at a rate depending on the solubility, diffusion rate and perfusion.[1]

If the concentration of the inert gas in the breathing gas is reduced below that of any of the tissues, there will be a tendency for gas to return from the tissues to the breathing gas. This is known as outgassing, and occurs during decompression, when the reduction in ambient pressure or a change of breathing gas reduces the partial pressure of the inert gas in the lungs.[1]

The combined concentrations of gases in any given tissue will depend on the history of pressure and gas composition. Under equilibrium conditions, the total concentration of dissolved gases will be less than the ambient pressure, as oxygen is metabolised in the tissues, and the carbon dioxide produced is much more soluble. However, during a reduction in ambient pressure, the rate of pressure reduction may exceed the rate at which gas can be eliminated by diffusion and perfusion, and if the concentration gets too high, it may reach a stage where bubble formation can occur in the supersaturated tissues. When the pressure of gases in a bubble exceeds the combined external pressures of ambient pressure and the surface tension from the bubble - liquid interface, the bubble will grow, and this growth can cause damage to tissues. Symptoms caused by this damage are known as decompression sickness.[1]

The actual rates of diffusion and perfusion and the solubility of gases in specific tissues are not generally known, and they vary considerably. However, mathematical models have been proposed which approximate the real situation to a greater or lesser extent, and these models are used to predict whether symptomatic bubble formation is likely to occur for a given pressure exposure profile.[8] Decompression involves a complex interaction of gas solubility, partial pressures and concentration gradients, diffusion, bulk transport and bubble mechanics in living tissues.[6]

Dissolved phase gas dynamics

[edit]Solubility of gases in liquids is influenced by the nature of the solvent liquid and the solute,[9] the temperature,[10] pressure,[11][12] and the presence of other solutes in the solvent.[13] Diffusion is faster in smaller, lighter molecules of which helium is the extreme example. Diffusivity of helium is 2.65 times faster than nitrogen.[14] The concentration gradient, can be used as a model for the driving mechanism of diffusion.[15] In this context, inert gas refers to a gas which is not metabolically active. Atmospheric nitrogen (N2) is the most common example, and helium (He) is the other inert gas commonly used in breathing mixtures for divers.[16] Atmospheric nitrogen has a partial pressure of approximately 0.78 bar at sea level. Air in the alveoli of the lungs is diluted by saturated water vapour (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2), a metabolic product given off by the blood, and contains less oxygen (O2) than atmospheric air as some of it is taken up by the blood for metabolic use. The resulting partial pressure of nitrogen is about 0,758 bar.[17]

At atmospheric pressure the body tissues are therefore normally saturated with nitrogen at 0.758 bar (569 mmHg). At increased ambient pressures due to depth or habitat pressurisation, a diver's lungs are filled with breathing gas at the increased pressure, and the partial pressures of the constituent gases will be increased proportionately.[8] The inert gases from the breathing gas in the lungs diffuse into blood in the alveolar capillaries and are distributed around the body by the systemic circulation in the process known as perfusion.[8] Dissolved materials are transported in the blood much faster than they would be distributed by diffusion alone.[18] From the systemic capillaries the dissolved gases diffuse through the cell membranes and into the tissues, where it may eventually reach equilibrium. The greater the blood supply to a tissue, the faster it will reach equilibrium with gas at the new partial pressure.[8][18] This equilibrium is called saturation.[8] Ingassing appears to follow a simple inverse exponential equation. The time it takes for a tissue to take up or release 50% of the difference in dissolved gas capacity at a changed partial pressure is called the half-time for that tissue and gas.[19][20]

Gas remains dissolved in the tissues until the partial pressure of that gas in the lungs is reduced sufficiently to cause a concentration gradient with the blood at a lower concentration than the relevant tissues. As the concentration in the blood drops below the concentration in the adjacent tissue, the gas will diffuse out of the tissue into the blood, and will then be transported back to the lungs where it will diffuse into the lung gas and then be eliminated by exhalation. If the ambient pressure reduction is limited, this desaturation will take place in the dissolved phase, but if the ambient pressure is lowered sufficiently, bubbles may form and grow, both in blood and other supersaturated tissues.[8] When the partial pressure of all gas dissolved in a tissue exceeds the total ambient pressure on the tissue it is supersaturated,[21] and there is a possibility of bubble formation.[8]

The sum of partial pressures of the gas that the diver breathes must necessarily balance with the sum of partial pressures in the lung gas. In the alveoli the gas has been humidified and has gained carbon dioxide from the venous blood. Oxygen has also diffused into the arterial blood, reducing the partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli. As the total pressure in the alveoli must balance with the ambient pressure, this dilution results in an effective partial pressure of nitrogen of about 758 mb (569 mmHg) in air at normal atmospheric pressure.[22] At a steady state, when the tissues have been saturated by the inert gases of the breathing mixture, metabolic processes reduce the partial pressure of the less soluble oxygen and replace it with carbon dioxide, which is considerably more soluble in water. In the cells of a typical tissue, the partial pressure of oxygen will drop, while the partial pressure of carbon dioxide will rise. The sum of these partial pressures (water, oxygen, carbon dioxide and nitrogen) is less than the total pressure of the respiratory gas. This is a significant saturation deficit, and it provides a buffer against supersaturation and a driving force for dissolving bubbles.[22] Experiments suggest that the degree of unsaturation increases linearly with pressure for a breathing mixture of fixed composition, and decreases linearly with fraction of inert gas in the breathing mixture.[23] As a consequence, the conditions for maximising the degree of unsaturation are a breathing gas with the lowest possible fraction of inert gas – i.e. pure oxygen, at the maximum permissible partial pressure. This saturation deficit is also referred to as inherent unsaturation, the "Oxygen window".[24] or partial pressure vacancy.[25]

The location of micronuclei or where bubbles initially form is not known.[26] The incorporation of bubble formation and growth mechanisms in decompression models may make the models more biophysical and allow better extrapolation.[26] Flow conditions and perfusion rates are dominant parameters in competition between tissue and circulation bubbles, and between multiple bubbles, for dissolved gas for bubble growth.[26]

Bubble mechanics

[edit]Equilibrium of forces on the surface is required for a bubble to exist. The sum of the Ambient pressure and pressure due to tissue distortion, exerted on the outside of the surface, with surface tension of the liquid at the interface between the bubble and the surroundings must be balanced by the pressure on the inside of the bubble. This is the sum of the partial pressures of the gases inside due to the net diffusion of gas to and from the bubble. The force balance on the bubble may be modified by a layer of surface active molecules which can stabilise a microbubble at a size where surface tension on a clean bubble would cause it to collapse rapidly, and this surface layer may vary in permeability, so that if the bubble is sufficiently compressed it may become impermeable to diffusion.[27] If the solvent outside the bubble is saturated or unsaturated, the partial pressure will be less than in the bubble, and the surface tension will be increasing the internal pressure in direct proportion to surface curvature, providing a pressure gradient to increase diffusion out of the bubble, effectively "squeezing the gas out of the bubble", and the smaller the bubble the faster it will get squeezed out. A gas bubble can only grow at constant pressure if the surrounding solvent is sufficiently supersaturated to overcome the surface tension or if the surface layer provides sufficient reaction to overcome surface tension.[27] Clean bubbles that are sufficiently small will collapse due to surface tension if the supersaturation is low. Bubbles with semipermeable surfaces will either stabilise at a specific radius depending on the pressure, the composition of the surface layer, and the supersaturation, or continue to grow indefinitely, if larger than the critical radius.[28] Bubble formation can occur in the blood or other tissues.[29]

A solvent can carry a supersaturated load of gas in solution. Whether it will come out of solution in the bulk of the solvent to form bubbles will depend on a number of factors. Something which reduces surface tension, or adsorbs gas molecules, or locally reduces solubility of the gas, or causes a local reduction in static pressure in a fluid may result in a bubble nucleation or growth. This may include velocity changes and turbulence in fluids and local tensile loads in solids and semi-solids. Lipids and other hydrophobic surfaces may reduce surface tension (blood vessel walls may have this effect). Dehydration may reduce gas solubility in a tissue due to higher concentration of other solutes, and less solvent to hold the gas.[30] Another theory presumes that microscopic bubble nuclei always exist in aqueous media, including living tissues. These bubble nuclei are spherical gas phases that are small enough to remain in suspension yet strong enough to resist collapse, their stability being provided by an elastic surface layer consisting of surface-active molecules which resists the effect of surface tension.[31]

Once a micro-bubble forms it may continue to grow if the tissues are sufficiently supersaturated. As the bubble grows it may distort the surrounding tissue and cause damage to cells and pressure on nerves resulting in pain, or may block a blood vessel, cutting off blood flow and causing hypoxia in the tissues normally perfused by the vessel.[32]

If a bubble or an object exists which collects gas molecules this collection of gas molecules may reach a size where the internal pressure exceeds the combined surface tension and external pressure and the bubble will grow.[33] If the solvent is sufficiently supersaturated, the diffusion of gas into the bubble will exceed the rate at which it diffuses back into solution, and if this excess pressure is greater than the pressure due to surface tension the bubble will continue to grow. When a bubble grows, the surface tension decreases, and the interior pressure drops, allowing gas to diffuse in faster, and diffuse out slower, so the bubble grows or shrinks in a positive feedback situation. The growth rate is reduced as the bubble grows because the surface area increases as the square of the radius, while the volume increases as the cube of the radius. If the external pressure is reduced due to reduced hydrostatic pressure during ascent, the bubble will also grow, and conversely, an increased external pressure will cause the bubble to shrink, but may not cause it to be eliminated entirely if a compression-resistant surface layer exists.[33]

Decompression bubbles appear to form mostly in the systemic capillaries where the gas concentration is highest, often those feeding the veins draining the active limbs. They do not generally form in the arteries provided that ambient pressure reduction is not too rapid, as arterial blood has recently had the opportunity to release excess gas into the lungs. The bubbles carried back to the heart in the veins may be transferred to the systemic circulation via a patent foramen ovale in divers with this septal defect, after which there is a risk of occlusion of capillaries in whichever part of the body they end up in.[34]

Bubbles which are carried back to the heart in the veins will pass into the right side of the heart, and from there they will normally enter the pulmonary circulation and pass through or be trapped in the capillaries of the lungs, which are around the alveoli and very near to the respiratory gas, where the gas will diffuse from the bubbles though the capillary and alveolar walls into the gas in the lung. If the number of lung capillaries blocked by these bubbles is relatively small, the diver will not display symptoms, and no tissue will be damaged (lung tissues are adequately oxygenated by diffusion).[35] The bubbles which are small enough to pass through the lung capillaries may be small enough to be dissolved due to a combination of surface tension and diffusion to a lowered concentration in the surrounding blood, though the Varying Permeability Model nucleation theory implies that most bubbles passing through the pulmonary circulation will lose enough gas to pass through the capillaries and return to the systemic circulation as recycled but stable nuclei.[36] Bubbles which form within the tissues must be eliminated in situ by diffusion, which implies a suitable concentration gradient.[35]

Isobaric counterdiffusion (ICD)

[edit]Isobaric counterdiffusion is the diffusion of gases in opposite directions caused by a change in the composition of the external ambient gas or breathing gas without change in the ambient pressure. During decompression after a dive this can occur when a change is made to the breathing gas, or when the diver moves into a gas filled environment which differs from the breathing gas.[37] While not strictly speaking a phenomenon of decompression, it is a complication that can occur during decompression, and that can result in the formation or growth of bubbles without changes in the environmental pressure. Two forms of this phenomenon have been described by Lambertsen:[38][37]

Superficial ICD (also known as Steady State Isobaric Counterdiffusion)[39] occurs when the inert gas breathed by the diver diffuses more slowly into the body than the inert gas surrounding the body.[38][37][39] An example of this would be breathing air in an heliox environment. The helium in the heliox diffuses into the skin quickly, while the nitrogen diffuses more slowly from the capillaries to the skin and out of the body. The resulting effect generates supersaturation in certain sites of the superficial tissues and the formation of inert gas bubbles.[37]

Deep Tissue ICD (also known as Transient Isobaric Counterdiffusion)[39] occurs when different inert gases are breathed by the diver in sequence.[38] The rapidly diffusing gas is transported into the tissue faster than the slower diffusing gas is transported out of the tissue.[37] This can occur as divers switch from a nitrogen mixture to a helium mixture or when saturation divers breathing hydreliox switch to a heliox mixture.[37][40]

Doolette and Mitchell's study of Inner Ear Decompression Sickness (IEDCS) shows that the inner ear may not be well-modelled by common (e.g. Bühlmann) algorithms. Doolette and Mitchell propose that a switch from a helium-rich mix to a nitrogen-rich mix, as is common in technical diving when switching from trimix to nitrox on ascent, may cause a transient supersaturation of inert gas within the inner ear and result in IEDCS.[41] They suggest that breathing-gas switches from helium-rich to nitrogen-rich mixtures should be carefully scheduled either deep (with due consideration to nitrogen narcosis) or shallow to avoid the period of maximum supersaturation resulting from the decompression. Switches should also be made during breathing of the largest inspired oxygen partial pressure that can be safely tolerated with due consideration to oxygen toxicity.[41]

Causative role of oxygen

[edit]Although it is commonly held that DCS is caused by inert gas supersaturation, Hempleman has stated:

...This did not lead to a sufficient cut-back in the permitted decompression ratio and an allowance in the calculations is now made for high oxygen partial pressures. Whenever the partial pressure of oxygen in air (or mixture) exceeds 0.6 bar then it is considered that significant amounts of dissolved oxygen are present in the tissues and that there is an increased decompression risk. This is estimated by adding 25% to the dive depth, and proceeding with the calculations as just outlined using assumption (1). An oxygen first stop depth is thus obtained, and 5 min is spent at this depth to allow for metabolic use of the excess dissolved oxygen gas. Following this 'oxygen stop' the calculations proceed as outlined above.[42]

Decompression sickness

[edit]Vascular bubbles formed in the systemic capillaries may be trapped in the lung capillaries, temporarily blocking them. If this is severe, the symptom called "chokes" may occur.[34] If the diver has a patent foramen ovale (or a shunt in the pulmonary circulation), bubbles may pass through it and bypass the pulmonary circulation to enter the arterial blood. If these bubbles are not absorbed in the arterial plasma and lodge in systemic capillaries they will block the flow of oxygenated blood to the tissues supplied by those capillaries, and those tissues will be starved of oxygen. Moon and Kisslo (1988) concluded that "the evidence suggests that the risk of serious neurological DCI or early onset DCI is increased in divers with a resting right-to-left shunt through a PFO. There is, at present, no evidence that PFO is related to mild or late onset bends."[43]

Bubbles form within other tissues as well as the blood vessels.[34] Inert gas can diffuse into bubble nuclei between tissues. In this case, the bubbles can distort and permanently damage the tissue. As they grow, the bubbles may also compress nerves as they grow causing pain.[35][44]

Extravascular or autochthonous[a] bubbles usually form in slow tissues such as joints, tendons and muscle sheaths. Direct expansion causes tissue damage, with the release of histamines and their associated affects. Biochemical damage may be as important as, or more important than mechanical effects.[35][34][45]

The exchange of dissolved gases between the blood and tissues is controlled by perfusion and to a lesser extent by diffusion, particularly in heterogeneous tissues. The distribution of blood flow to the tissues is variable and subject to a variety of influences. When the flow is locally high, that area is dominated by perfusion, and by diffusion when the flow is low. The distribution of flow is controlled by the mean arterial pressure and the local vascular resistance, and the arterial pressure depends on cardiac output and the total vascular resistance. Basic vascular resistance is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, and metabolites, temperature, and local and systemic hormones have secondary and often localised effects, which can vary considerably with circumstances. Peripheral vasoconstriction in cold water decreases overall heat loss without increasing oxygen consumption until shivering begins, at which point oxygen consumption will rise, though the vasoconstriction can persist.[34]

The composition of the breathing gas during pressure exposure and decompression is significant in inert gas uptake and elimination for a given pressure exposure profile. Breathing gas mixtures for diving will typically have a different gas fraction of nitrogen to that of air. The partial pressure of each component gas will differ from that of nitrogen in air at any given depth, and uptake and elimination of each inert gas component is proportional to the actual partial pressure over time. The two foremost reasons for use of mixed breathing gases are the reduction of nitrogen partial pressure by dilution with oxygen, to make Nitrox mixtures, primarily to reduce the rate of nitrogen uptake during pressure exposure, and the substitution of helium (and occasionally other gases) for the nitrogen to reduce the narcotic effects under high partial pressure exposure. Depending on the proportions of helium and nitrogen, these gases are called Heliox, if there is no nitrogen, or Trimix, if there is nitrogen and helium along with the essential oxygen.[46][47] The inert gases used as substitutes for nitrogen have different solubility and diffusion characteristics in living tissues to the nitrogen they replace. For example, the most common inert gas diluent substitute for nitrogen is helium, which is significantly less soluble in living tissue,[48] but also diffuses faster due to the relatively small size and mass of the He atom in comparison with the N2 molecule.[49]

Blood flow to skin and fat are affected by skin and core temperature, and resting muscle perfusion is controlled by the temperature of the muscle itself. During exercise increased flow to the working muscles is often balanced by reduced flow to other tissues, such as kidneys spleen and liver.[34] Blood flow to the muscles is also lower in cold water, but exercise keeps the muscle warm and flow elevated even when the skin is chilled. Blood flow to fat normally increases during exercise, but this is inhibited by immersion in cold water. Adaptation to cold reduces the extreme vasoconstriction which usually occurs with cold water immersion.[34] Variations in perfusion distribution do not necessarily affect respiratory inert gas exchange, though some gas may be locally trapped by changes in perfusion. Rest in a cold environment will reduce inert gas exchange from skin, fat and muscle, whereas exercise will increase gas exchange. Exercise during decompression can reduce decompression time and risk, providing bubbles are not present, but can increase risk if bubbles are present.[34] Inert gas exchange is least favourable for the diver who is warm and exercises at depth during the ingassing phase, and rests and is cold during decompression.[34]

Other factors which can affect decompression risk include oxygen concentration, carbon dioxide levels, body position, vasodilators and constrictors, positive or negative pressure breathing.[34] and dehydration (blood volume).[50] Individual susceptibility to decompression sickness has components which can be attributed to a specific cause, and components which appear to be random. The random component makes successive decompressions a poor test of susceptibility.[34] Obesity and high serum lipid levels have been implicated by some studies as risk factors, and risk seems to increase with age.[51] Another study has also shown that older subjects tended to bubble more than younger subjects for reasons not yet known, but no trends between weight, body fat, or gender and bubbles were identified, and the question of why some people are more likely to form bubbles than others remains unclear.[52]

Decompression model concepts

[edit]

Two rather different concepts have been used for decompression modelling. The first assumes that dissolved gas is eliminated while in the dissolved phase, and that bubbles are not formed during asymptomatic decompression. The second, which is supported by experimental observation, assumes that bubbles are formed during most asymptomatic decompressions, and that gas elimination must consider both dissolved and bubble phases.[33]

Early decompression models tended to use the dissolved phase models, and adjusted them by more or less arbitrary factors to reduce the risk of symptomatic bubble formation. Dissolved phase models are of two main groups. Parallel compartment models, where several compartments with varying rates of gas absorption (half time), are considered to exist independently of each other, and the limiting condition is controlled by the compartment which shows the worst case for a specific exposure profile. These compartments represent conceptual tissues and are not intended to represent specific organic tissues, merely to represent the range of possibilities for the organic tissues. The second group uses serial compartments, where gas is assumed to diffuse through one compartment before it reaches the next.[53] A recent variation on the serial compartment model is the Goldman interconnected compartment model (ICM).[54]

More recent models attempt to model bubble dynamics, also by simplified models, to facilitate the computation of tables, and later to allow real time predictions during a dive. The models used to approximate bubble dynamics are varied, and range from those which are not much more complex that the dissolved phase models, to those which require considerably greater computational power.[55]

None of the decompression models can be shown to be an accurate representation of the physiological processes, although interpretations of the mathematical models have been proposed which correspond with various hypotheses. They are all approximations which predict reality to a greater or lesser extent, and are acceptably reliable only within the bounds of calibration against collected experimental data.[56]

Range of application

[edit]The ideal decompression profile creates the greatest possible gradient for inert gas elimination from a tissue without causing bubbles to form,[57] and the dissolved phase decompression models are based on the assumption that bubble formation can be avoided. However, it is not certain whether this is practically possible: some of the decompression models assume that stable bubble micronuclei always exist.[31] The bubble models make the assumption that there will be bubbles, but there is a tolerable total gas phase volume[31] or a tolerable gas bubble size,[58] and limit the maximum gradient to take these tolerances into account.[31][58]

Decompression models should ideally accurately predict risk over the full range of exposure from short dives within the no-stop limits, decompression bounce dives over the full range of practical applicability, including extreme exposure dives and repetitive dives, alternative breathing gases, including gas switches and constant PO2, variations in dive profile, and saturation dives. This is not generally the case, and most models are limited to a part of the possible range of depths and times. They are also limited to a specified range of breathing gases, and sometimes restricted to air.[59]

A fundamental problem in the design of decompression tables is that the simplified rules that govern a single dive and ascent do not apply when some tissue bubbles already exist, as these will delay inert gas elimination and equivalent decompression may result in decompression sickness.[59] Repetitive diving, multiple ascents within a single dive, and surface decompression procedures are significant risk factors for DCS.[57] These have been attributed to the development of a relatively high gas phase volume which may be partly carried over to subsequent dives or the final ascent of a sawtooth profile.[6]

The function of decompression models has changed with the availability of Doppler ultrasonic bubble detectors, and is no longer merely to limit symptomatic occurrence of decompression sickness, but also to limit asymptomatic post-dive venous gas bubbles.[26] A number of empirical modifications to dissolved phase models have been made since the identification of venous bubbles by Doppler measurement in asymptomatic divers soon after surfacing.[60]

Efficiency and safety

[edit]Two criteria that have been used in comparing decompression schedules are efficiency and safety, where decompression efficiency is defined as the ability of a schedule to provide acceptable safety from decompression sickness in the shortest time spent decompressing, and decompression safety, or converely, risk, is measured by the probability of decompression sickness incurred by following a given schedule for a given dive profile. Since it is impracticable to eliminate all risk using current knowledge of the effects of several variables, risk is estimated by statistical analysis of the recorded outcomes of exposure and decompression profiles, and an acceptable risk is stipulated, which may vary depending on the circumstances of the application.[61]

Tissue compartments

[edit]One attempt at a solution was the development of multi-tissue models, which assumed that different parts of the body absorbed and eliminated gas at different rates. These are hypothetical tissues which are designated as fast and slow to describe the rate of saturation. Each tissue, or compartment, has a different half-life. Real tissues will also take more or less time to saturate, but the models do not need to use actual tissue values to produce a useful result. Models with from one to 16 tissue compartments[62] have been used to generate decompression tables, and dive computers have used up to 20 compartments.[63]

For example: Tissues with a high lipid content can take up a larger amount of nitrogen, but often have a poor blood supply. These will take longer to reach equilibrium, and are described as slow, compared to tissues with a good blood supply and less capacity for dissolved gas, which are described as fast.[64]

Fast tissues absorb gas relatively quickly, but will generally release it quickly during ascent. A fast tissue may become saturated in the course of a normal recreational dive, while a slow tissue may have absorbed only a small part of its potential gas capacity. By calculating the levels in each compartment separately, researchers are able to construct more effective algorithms. In addition, each compartment may be able to tolerate more or less supersaturation than others. The final form is a complicated model, but one that allows for the construction of algorithms and tables suited to a wide variety of diving.[64] A typical dive computer has an 8–12 tissue model, with half times varying from 5 minutes to 400 minutes.[63] The Bühlmann tables use an algorithm with 16 tissues, with half times varying from 4 minutes to 640 minutes.[62]

Tissues may be assumed to be in series, where dissolved gas must diffuse through one tissue to reach the next, which has different solubility properties, in parallel, where diffusion into and out of each tissue is considered to be independent of the others, and as combinations of series and parallel tissues, which becomes computationally complex.[54]

Ingassing model

[edit]The half time of a tissue is the time it takes for the tissue to take up or release 50% of the difference in dissolved gas capacity at a changed partial pressure. For each consecutive half time the tissue will take up or release half again of the cumulative difference in the sequence ½, ¾, 7/8, 15/16, 31/32, 63/64 etc.[20] Tissue compartment half times range from 1 minute to at least 720 minutes.[65] A specific tissue compartment will have different half times for gases with different solubilities and diffusion rates. Ingassing is generally modeled as following a simple inverse exponential equation where saturation is assumed after approximately four (93.75%) to six (98.44%) half-times depending on the decompression model.[19][66][67] There is normally no phase change during ingassing after the gases are dissolved in the blood of the pulmonary circulation in the lungs. They remain in solution in whichever tissues they reach by perfusion and diffusion, so the model is fairly robust. The exception is for isobaric counterdiffusion which can induce bubble growth and posssibly bubble formation when a gas of different solubility is introduced to the breathing mixture.[38][37] This model may not adequately describe the dynamics of outgassing if gas phase bubbles are present.[68][69]

Outgassing models

[edit]For optimised decompression the driving force for tissue desaturation should be kept at a maximum, provided that this does not cause symptomatic tissue injury due to bubble formation and growth (symptomatic decompression sickness), or produce a condition where diffusion is retarded for any reason.[70]

There are two fundamentally different ways this has been approached. The first is based on an assumption that there is a level of supersaturation which does not produce symptomatic bubble formation and is based on empirical observations of the maximum decompression rate which does not result in an unacceptable rate of symptoms. This approach seeks to maximise the concentration gradient providing there are no symptoms, and commonly uses a slightly modified exponential half-time model. The second assumes that bubbles will form at any level of supersaturation where the total gas tension in the tissue is greater than the ambient pressure and that gas in bubbles is eliminated more slowly than dissolved gas.[67] These philosophies result in differing characteristics of the decompression profiles derived for the two models: The critical supersaturation approach gives relatively rapid initial ascents, which maximize the concentration gradient, and long shallow stops, while the bubble models require slower ascents, with deeper first stops, but may have shorter shallow stops. This approach uses a variety of models.[67][71][72][70][73]

The critical supersaturation approach

[edit]J.S. Haldane originally used a critical pressure ratio of 2 to 1 for decompression on the principle that the saturation of the body should at no time be allowed to exceed about double the air pressure.[74] This principle was applied as a pressure ratio of total ambient pressure and did not take into account the partial pressures of the component gases of the breathing air. His experimental work on goats and observations of human divers appeared to support this assumption. However, in time, this was found to be inconsistent with incidence of decompression sickness and changes were made to the initial assumptions. This was later changed to a 1.58:1 ratio of nitrogen partial pressures.[75]

Further research by people such as Robert Workman suggested that the criterion was not the ratio of pressures, but the actual pressure differentials. Applied to Haldane's work, this would suggest that the limit is not determined by the 1.58:1 ratio but rather by the critical pressure difference of 0.58 atmospheres between tissue pressure and ambient pressure. Most Haldanean tables since the mid 20th century, including the Bühlmann tables, are based on the critical difference assumption .[76]

The M-value is the maximum value of absolute inert gas pressure that a tissue compartment can take at a given ambient pressure without presenting symptoms of decompression sickness. M-values are limits for the tolerated gradient between inert gas pressure and ambient pressure in each compartment. Alternative terminology for M-values include "supersaturation limits", "limits for tolerated overpressure", and "critical tensions".[71][77]

Gradient factors are a way of modifying the M-value to a more conservative value for use in a decompression algorithm. The gradient factor is a percentage of the M-value chosen by the algorithm designer, and varies linearly between the maximum depth of the specific dive and the surface. They are expressed as a two number designation, where the first number is the percentage of the deep M-value, and the second is a percentage of the shallow M-value.[72] The gradient factors are applied to all tissue compartments equally and produce an M-value which is linearly variable in proportion to ambient pressure.[72]

- For example: A 30/85 gradient factor would limit the allowed supersaturation at depth to 30% of the designer's maximum, and to 85% at the surface.

In effect the user is selecting a lower maximum supersaturation than the designer considered appropriate. Use of gradient factors will increase decompression time, particularly in the depth zone where the M-value is reduced the most. Gradient factors may be used to force deeper stops in a model which would otherwise tend to produce relatively shallow stops, by using a gradient factor with a small first number.[72] Several models of dive computer allow user input of gradient factors as a way of inducing a more conservative, and therefore presumed lower risk, decompression profile.[78] Forcing a low gradient factor at the deep M-value can have the effect of increasing ingassing during the ascent, generally of the slower tissues, which must then release a larger gas load at shallower depths. This has been shown to be an inefficient decompression strategy.[79][80]

The Variable Gradient Model adjusts the gradient factors to fit the depth profile on the assumption that a straight line adjustment using the same factor on the deep M-value regardless of the actual depth is less appropriate than using an M-value linked to the actual depth. (the shallow M-value is linked to actual depth of zero in both cases) [81]

This section needs expansion with: More specific details on Variable gradient model. You can help by adding to it. (February 2021) |

The no-supersaturation approach

[edit]According to the thermodynamic model of Hugh LeMessurier and Brian Andrew Hills, this condition of optimum driving force for outgassing is satisfied when the ambient pressure is just sufficient to prevent phase separation (bubble formation).[73]

The fundamental difference of this approach is equating absolute ambient pressure with the total of the partial gas tensions in the tissue for each gas after decompression as the limiting point beyond which bubble formation is expected.[73]

The model assumes that the natural unsaturation in the tissues due to metabolic reduction in oxygen partial pressure provides the buffer against bubble formation, and that the tissue may be safely decompressed provided that the reduction in ambient pressure does not exceed this unsaturation value. Clearly any method which increases the unsaturation would allow faster decompression, as the concentration gradient would be greater without risk of bubble formation.[73]

The natural unsaturation increases with depth, so a larger ambient pressure differential is possible at greater depth, and reduces as the diver surfaces. This model leads to slower ascent rates and deeper first stops, but shorter shallow stops, as there is less bubble phase gas to be eliminated.[73]

The critical volume approach

[edit]The critical-volume criterion assumes that whenever the total volume of gas phase accumulated in the tissues exceeds a critical value, signs or symptoms of DCS will appear. This assumption is supported by doppler bubble detection surveys. The consequences of this approach depend strongly on the bubble formation and growth model used, primarily whether bubble formation is practicably avoidable during decompression.[33]

This approach is used in decompression models which assume that during practical decompression profiles, there will be growth of stable microscopic bubble nuclei which always exist in aqueous media, including living tissues.[70]

Efficient decompression will minimize the total ascent time while limiting the total accumulation of bubbles to an acceptable non-symptomatic critical value. The physics and physiology of bubble growth and elimination indicate that it is more efficient to eliminate bubbles while they are very small. Models which include bubble phase have produced decompression profiles with slower ascents and deeper initial decompression stops as a way of curtailing bubble growth and facilitating early elimination, in comparison with the models which consider only dissolved phase gas.[82]

Bounce dives

[edit]A bounce dive is any dive where the exposure to pressure is not long enough for all the tissues to reach equilibrium with the inert gases in the breathing gas.[83]

Saturation dives

[edit]A saturation exposure is where the time exposed to pressure is sufficient for all tissues to reach equilibrium with the inert gases in the breathing mixture. For practical purposes this is usually taken as 6 times the half time of the slowest tissue in the model.[83]

No-stop limits

[edit]A no-stop limit, also called no decompression limit (NDL) is the theoretical maximum dissolved gas content of each tissue compartment of the whole body, which can be decompressed directly to surface pressure at the chosen ascent rate used by the model, without a need to stop to outgas at any depth, which has an acceptable risk of developing symptomatic decompression sickness. No decompression limit is a misnomer as the ascent at the specified ascent rate is decompression, but the term has historical inertia and continues to be used.[84][85]

Decompression ceiling, floor and window

[edit]Once the gas loading of one or more tissue compartments exceeds the maximum level accepted for the no-stop limit, there is a minimum depth to which the diver can ascend at the appropriate ascent rate, at an acceptable risk for decompression sickness. This depth is known as the decompression ceiling. It may be considered a soft overhead, in that it is physically trivial to ascend above it, but that increases the risk of developing symptomatic decompression sickness according to the decompression model to a theoretically unacceptable level. The tissue that reaches its decompression ceiling first is called the limiting tissue.[86][87]

The depth (or pressure) at which the controlling tissue starts to offgas for a given breathing gas is known as the decompression floor. Above this floor and below the decompression ceiling is the depth range known as the decompression window, the depth range in which safe decompression can occur according to the decompression model. Decompression stress is lower towards the floor, and decompression efficiency is greater nearer the ceiling. The floor depth depends on the concentration gradient of the inert gas, and thereby partial pressure of the inert part of the breathing gas.[87]

Offgassing near the floor is relatively slow, and some slower tissues may still be ingassing. If the diver stays in this depth zone the decompression obligation may increase, and off-gassing will eventually stop as the floor rises. At the same time, as offgassing of the limiting tissue progresses, the ceiling will also rise, allowing the diver to ascend to follow it. However if ingassing of other tissues is sufficient, one of them may take over as the limiting tissue and bring the ceiling deeper. Off-gassing near he floor also minimises bubble growth, and near the ceiling maximises off-gassing of dissolved gas.[87]

Decompression obligation

[edit]A decompression obligation is the presence in the tissues of sufficient dissolved gas that the risk of symptomatic decompression sickness is unacceptable if a direct ascent to surface pressure is made at the prescribed ascent rate for the decompression model in use. A diver with a decompression ceiling can be said to have a decompression obligation, meaning that time must be spent outgassing during the ascent additional to the time spent ascending at the appropriate ascent rate. This time is nominally and most efficiently spent at decompression stops, though outgassing will occur at any depth where the arterial blood and lung gas have a lower partial pressure of the inert gas than the limiting tissue. When a decompression obligation exists, there will be a theoretical safe minimum depth known as the decompression ceiling. Obligatory decompression stops will be indicated at a depth at or below the current ceiling.[83]

Time to surface

[edit]Time to surface (TTS) is the estimated total time required for a diver to surface from a given point on a dive profile, using a given set of decompression gases, ascending at the nominal ascent rate, and doing all the stops at the specifies depths. This value may be an estimate calculated from a dive plan, and followed by the diver as the ascent schedule, or shown on the screen of a dive computer as updated in real time. It may be based on the current gas selected, or the optimum gas selection from all gases set as active gases on the computer.[88]

Staged decompression

[edit]Staged decompression is done with stops as specified depths based on an easily followed series. For most tables this has historically been a convenient 3 metres (10 ft) interval, but any arbitrary spacing may be used provided the computation of decompression stops uses it. The diver must stay at the prescribed stop depth until the ceiling decreases to the next shallower stop depth, at which point the diver ascends to that depth for the next stop.[86]

The calculation of stop time can also be done to follow the decompression ceiling, which will give a maximised pressure gradient for inert gas washout, and reduces the overall decompression duration by about 4 to 12% This strategy can be approximately followed when using a dive computer with the option enabled. The effect on decompression risk with this strategy is unknown, as no testing has been done as of 2022.[86]

Residual inert gas

[edit]Gas bubble formation has been experimentally shown to significantly inhibit inert gas elimination.[17][89] A considerable amount of inert gas will remain in the tissues after a diver has surfaced, even if no symptoms of decompression sickness occur. This residual gas may be dissolved or in sub-clinical bubble form, and will continue to outgas while the diver remains at the surface. If a repetitive dive is made, the tissues are preloaded with this residual gas which will make them saturate faster.[90][91]

In repetitive diving, the slower tissues can accumulate gas day after day, if there is insufficient time for the gas to be eliminated between dives. This can be a problem for multi-day multi-dive situations. Multiple decompressions per day over multiple days can increase the risk of decompression sickness because of the build up of asymptomatic bubbles, which reduce the rate of off-gassing and are not accounted for in most decompression algorithms.[92] Consequently, some diver training organisations make extra recommendations such as taking "the seventh day off".[93]

Decompression models in practice

[edit]Deterministic models

[edit]Deterministic decompression models are a rule based approach to calculating decompression.[94] These models work from the idea that "excessive" supersaturation in various tissues is "unsafe" (resulting in decompression sickness). The models usually contain multiple depth and tissue dependent rules based on mathematical models of idealised tissue compartments. There is no objective mathematical way of evaluating the rules or overall risk other than comparison with empirical test results. The models are compared with experimental results and reports from the field, and rules are revised by qualitative judgment and curve fitting so that the revised model more closely predicts observed reality, and then further observations are made to assess the reliability of the model in extrapolations into previously untested ranges. The usefulness of the model is judged on its accuracy and reliability in predicting the onset of symptomatic decompression sickness and asymptomatic venous bubbles during ascent.[94]

It may be reasonably assumed that in reality, both perfusion transport by blood circulation, and diffusion transport in tissues where there is little or no blood flow occur. The problem with attempts to simultaneously model perfusion and diffusion is that there are large numbers of variables due to interactions between all of the tissue compartments and the problem becomes intractable. A way of simplifying the modelling of gas transfer into and out of tissues is to make assumptions about the limiting mechanism of dissolved gas transport to the tissues which control decompression. Assuming that either perfusion or diffusion has a dominant influence, and the other can be disregarded, can greatly reduce the number of variables.[70]

Perfusion limited tissues and parallel tissue models

[edit]The assumption that perfusion is the limiting mechanism leads to a model comprising a group of tissues with varied rates of perfusion, but supplied by blood of approximately equivalent gas concentration. It is also assumed that there is no gas transfer between tissue compartments by diffusion. This results in a parallel set of independent tissues, each with its own rate of ingassing and outgassing dependent on the rate of blood flowing through the tissue. Gas uptake for each tissue is generally modelled as an exponential function, with a fixed compartment half-time, and gas elimination may also be modelled by an exponential function, with the same or a longer half time, or as a more complex function, as in the exponential-linear elimination model.[90]

The critical ratio hypothesis predicts that the development of bubbles will occur in a tissue when the ratio of dissolved gas partial pressure to ambient pressure exceeds a particular ratio for a given tissue. The ratio may be the same for all tissue compartments or it may vary, and each compartment is allocated a specific critical supersaturation ratio, based on experimental observations.[19]

John Scott Haldane introduced the concept of half times to model the uptake and release of nitrogen into the blood. He suggested 5 tissue compartments with half times of 5, 10, 20, 40 and 75 minutes.[19] In this early hypothesis it was predicted that if the ascent rate does not allow the inert gas partial pressure in each of the hypothetical tissues to exceed the environmental pressure by more than 2:1 bubbles will not form.[74] Basically this meant that one could ascend from 30 m (4 bar) to 10 m (2 bar), or from 10 m (2 bar) to the surface (1 bar) when saturated, without a decompression problem. To ensure this a number of decompression stops were incorporated into the ascent schedules. The ascent rate and the fastest tissue in the model determine the time and depth of the first stop. Thereafter the slower tissues determine when it is safe to ascend further.[74] This 2:1 ratio was found to be too conservative for fast tissues (short dives) and not conservative enough for slow tissues (long dives). The ratio also seemed to vary with depth.[95] Haldane's approach to decompression modeling was used from 1908 to the 1960s with minor modifications, primarily changes to the number of compartments and half times used. The 1937 US Navy tables were based on research by O. D. Yarbrough and used 3 compartments: the 5- and 10-minute compartments were dropped. In the 1950s the tables were revised and the 5- and 10-minute compartments restored, and a 120-minute compartment added.[96]

In the 1960s Robert D. Workman of the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) reviewed the basis of the model and subsequent research performed by the US Navy. Tables based on Haldane's work and subsequent refinements were still found to be inadequate for longer and deeper dives. Workman proposed that the tolerable change in pressure was better described as a critical pressure difference, and revised Haldane's model to allow each tissue compartment to tolerate a different amount of supersaturation which varies with depth. He introduced the term "M-value" to indicate the maximum amount of supersaturation each compartment could tolerate at a given depth and added three additional compartments with 160, 200 and 240-minute half times. Workman presented his findings as an equation which could be used to calculate the results for any depth and stated that a linear projection of M-values would be useful for computer programming.[96]

A large part of Albert A. Bühlmann's research was to determine the longest half time compartments for Nitrogen and Helium, and he increased the number of compartments to 16. He investigated the implications of decompression after diving at altitude and published decompression tables that could be used at a range of altitudes. Bühlmann used a method for decompression calculation similar to that proposed by Workman, which included M-values expressing a linear relationship between maximum inert gas pressure in the tissue compartments and ambient pressure, but based on absolute pressure, which made them more easily adapted for altitude diving.[53] Bühlmann's algorithm was used to generate the standard decompression tables for a number of sports diving associations, and is used in several personal decompression computers, sometimes in a modified form.[53]

B.A. Hills and D.H. LeMessurier studied the empirical decompression practices of Okinawan pearl divers in the Torres Strait and observed that they made deeper stops but reduced the total decompression time compared with the generally used tables of the time. Their analysis strongly suggested that bubble presence limits gas elimination rates, and emphasized the importance of inherent unsaturation of tissues due to metabolic processing of oxygen. This became known as the thermodynamic model.[73] More recently, recreational technical divers developed decompression procedures using deeper stops than required by the decompression tables in use. These led to the RGBM and VPM bubble models.[97] A deep stop was originally an extra stop introduced by divers during ascent, at a greater depth than the deepest stop required by their computer algorithm. There are also computer algorithms that are claimed to use deep stops, but these algorithms and the practice of deep stops have not been adequately validated.[98]

A "Pyle stop" is a deep stop named after Richard Pyle, an early advocate of deep stops,[99] at the depths halfway between the bottom and the first conventional decompression stop, and halfway between the previous Pyle stop and the deepest conventional stop, provided the conventional stop is more than 9 m shallower. A Pyle stop is about 2 minutes long. The additional ascent time required for Pyle stops is included in the dive profile before finalising the decompression schedule.[100] Pyle found that on dives where he stopped periodically to vent the swim-bladders of his fish specimens, he felt better after the dive, and based the deep stop procedure on the depths and duration of these pauses.[98] The hypothesis is that these stops provide an opportunity to eliminate gas while still dissolved, or at least while the bubbles are still small enough to be easily eliminated, and the result is that there will be considerably fewer or smaller venous bubbles to eliminate at the shallower stops as predicted by the thermodynamic model of Hills.[101]

- For example, a diver ascends from a maximum depth of 60 metres (200 ft), where the ambient pressure is 7 bars (100 psi), to a decompression stop at 20 metres (66 ft), where the pressure is 3 bars (40 psi). The first Pyle stop would take place at the halfway pressure, which is 5 bars (70 psi) corresponding to a depth of 40 metres (130 ft). The second Pyle stop would be at 30 metres (98 ft). A third would be at 25 metres (82 ft) which is less than 9 metres (30 ft) below the first required stop, and therefore is omitted.[100][102]

The value and safety of deep stops additional to the decompression schedule derived from a decompression algorithm is unclear. Decompression experts have pointed out that deep stops are likely to be made at depths where ingassing continues for some slow tissues, and that the addition of deep stops of any kind should be included in the hyperbaric exposure for which the decompression schedule is computed, and not added afterwards, so that such ingassing of slower tissues can be taken into account.[98] Deep stops performed during a dive where the decompression is calculated in real-time are simply part of a multi-level dive to the computer, and add no risk beyond that which is inherent in the algorithm.

There is a limit to how deep a "deep stop" can be. Some off-gassing must take place, and continued on-gassing should be minimised for acceptably effective decompression. The "deepest possible decompression stop" for a given profile can be defined as the depth where the gas loading for the leading compartment crosses the ambient pressure line. This is not a useful stop depth - some excess in tissue gas concentration is necessary to drive the outgassing diffusion, however this depth is a useful indicator of the beginning of the decompression zone, in which ascent rate is part of the planned decompression.[103]

A study by DAN in 2004 found that the incidence of high-grade bubbles could be reduced to zero providing the nitrogen concentration of the most saturated tissue was kept below 80 percent of the allowed M value and that an added deep stop was a simple and practical way of doing this, while retaining the original ascent rate.[97]

Diffusion limited tissues and the "Tissue slab", and series models

[edit]

The assumption that diffusion is the limiting mechanism of dissolved gas transport in the tissues results in a rather different tissue compartment model. In this case a series of compartments has been postulated, with perfusion transport into one compartment, and diffusion between the compartments, which for simplicity are arranged in series, so that for the generalised compartment, diffusion is to and from only the two adjacent compartments on opposite sides, and the limit cases are the first compartment where the gas is supplied and removed via perfusion, and the end of the line, where there is only one neighbouring compartment.[53] The simplest series model is a single compartment, and this can be further reduced to a one-dimensional "tissue slab" model.[53]

Bubble models

[edit]Bubble decompression models are a rule based approach to calculating decompression based on the idea that microscopic bubble nuclei always exist in water and tissues that contain water and that by predicting and controlling the bubble growth, one can avoid decompression sickness. Most of the bubble models assume that bubbles will form during decompression, and that mixed phase gas elimination occurs, which is slower than dissolved phase elimination. Bubble models tend to have deeper first stops to get rid of more dissolved gas at a lower supersaturation to reduce the total bubble phase volume, and potentially reduce the time required at shallower depths to eliminate bubbles.[31][58][101]

Decompression models that assume mixed phase gas elimination include:

- The arterial bubble decompression model of the French Tables du Ministère du Travail[104] 1992[58]

- The U.S. Navy Exponential-Linear (Thalmann) algorithm used for the 2008 US Navy air decompression tables (among others)[53]

- Hennessy's combined perfusion/diffusion model of the BSAC'88 tables

- The Varying Permeability Model (VPM) developed by D.E. Yount and Hoffman (1986) at the University of Hawaii[31]

- The Reduced Gradient Bubble Model (RGBM) developed by Bruce Wienke in 1990 at Los Alamos National Laboratory[101]

- Michael Gernhardt proposed the Tissue Bubble Dynamics Model (1991)

- Wayne Gerth and Richard Vann (1997) published the Probabilistic Gas and Bubble Dynamics Model.[104]

- Lewis and Crow introduced their Gas Formation Model (GFM) in 2008.[104]

- The Copernicus model of Gutvik and Brubakk (2009)[104]

The most widely implemented model in dive computers is a simplified modification of the RGBM.[104] The models of Yount and Hoffman, and Wienke, assume that bubble formation is due to supersaturation, while Gernhardt, Gerth and Vann, and Gutvik and Brubakk assume pre-existing microscopic bubble nuclei, which grow when concentration of gases in the tissues is high enough. These models are more mathematically complex, and as of 2009 were unsuitable for real-time computation by dive computer.[104]

Goldman Interconnected Compartment Model

[edit]

In contrast to the independent parallel compartments of the Haldanean models, in which all compartments are considered risk bearing, the Goldman model posits a relatively well perfused "active" or "risk-bearing" compartment in series with adjacent relatively poorly perfused "reservoir" or "buffer" compartments, which are not considered potential sites for bubble formation, but affect the probability of bubble formation in the active compartment by diffusive inert gas exchange with the active compartment.[54][105] During compression, gas diffuses into the active compartment and through it into the buffer compartments, increasing the total amount of dissolved gas passing through the active compartment. During decompression, this buffered gas must pass through the active compartment again before it can be eliminated. If the gas loading of the buffer compartments is small, the added gas diffusion through the active compartment is slow.[105] The interconnected models predict a reduction in gas washout rate with time during decompression compared with the rate predicted for the independent parallel compartment model used for comparison.[54]

The Goldman model differs from the Kidd-Stubbs series decompression model in that the Goldman model assumes linear kinetics, where the K-S model includes a quadratic component, and the Goldman model considers only the central well-perfused compartment to contribute explicitly to risk, while the K-S model assumes all compartments to carry potential risk. The DCIEM 1983 model associates risk with the two outermost compartments of a four compartment series.[54] The mathematical model based on this concept is claimed by Goldman to fit not only the Navy square profile data used for calibration, but also predicts risk relatively accurately for saturation profiles. A bubble version of the ICM model was not significantly different in predictions, and was discarded as more complex with no significant advantages. The ICM also predicted decompression sickness incidence more accurately at the low-risk recreational diving exposures recorded in DAN's Project Dive Exploration data set. The alternative models used in this study were the LE1 (Linear-Exponential) and straight Haldanean models.[105] The Goldman model predicts a significant risk reduction following a safety stop on a low-risk dive[106] and significant risk reduction by using nitrox (more so than the PADI tables suggest).[107]

Probabilistic models

[edit]Probabilistic decompression models are designed to calculate the risk (or probability) of decompression sickness (DCS) occurring on a given decompression profile.[108][94] Statistical analysis is well suited to compressed air work in tunneling operations due to the large number of subjects undergoing similar exposures at the same ambient pressure and temperature, with similar workloads and exposure times, with the same decompression schedule.[109] Large numbers of decompressions under similar circumstances have shown that it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate all risk of DCS, so it is necessary to set an acceptable risk, based on the other factors relevant to the application. For example, easy access to effective treatment in the form of hyperbaric oxygen treatment on site, or greater advantage to getting the diver out of the water sooner, may make a higher incidence acceptable, while interfering with work schedule, adverse effects on worker morale or a high expectation of litigation would shift acceptable incidence rate downward. Efficiency is also a factor, as decompression of employees occurs during working hours.[109]

These methods can vary the decompression stop depths and times to arrive at a decompression schedule that assumes a specified probability of DCS occurring, while minimizing the total decompression time. This process can also work in reverse allowing one to calculate the probability of DCS for any decompression schedule, given sufficient reliable data.[109]

In 1936 an incidence rate of 2% was considered acceptable for compressed air workers in the UK. The US Navy in 2000 accepted a 2% incidence of mild symptoms, but only 0.1% serious symptoms. Commercial diving in the North Sea in the 1990s accepted 0.5% mild symptoms, but almost no serious symptoms, and commercial diving in the Gulf of Mexico also during the 1990s, accepted 0.1% mild cases and 0.025% serious cases. Health and Safety authorities tend to specify the acceptable risk as as low as reasonably practicable taking into account all relevant factors, including economic factors.[109][108] To analyse probability of mild and severe symptoms it is first necessary to define these classes of manifestation, as applicable to the analysis.[110]

The necessary tools for probability estimation for decompression sickness are a biophysical model which describes the inert gas exchange and bubble formation during decompression, exposure data in the form of pressure/time profiles for the breathing gas mixtures, and the DCS outcomes for these exposures, statistical methods, such as survival analysis or Bayesian analysis to find a best fit between model and experimental data, after which the models can be quantitatively compared and the best fitting model used to predict DCS probability for the model. This process is complicated by the influence of environmental conditions on DCS probability. Factors that affect perfusion of the tissues during ingassing and outgassing, which affect rates of inert gas uptake and elimination respectively, include immersion, temperature and exercise. Exercise is also known to promote bubble formation during decompression.[109]

The distribution of decompression stops is also known to affect DCS risk. A USN experiment using symptomatic decompression sickness as the endpoint, compared two models for dive working exposures on air using the same bottom time, water temperature and workload, with the same total decompression time, for two different depth distributions of decompression stops, also on air, and found the shallower stops to carry a statistically very significantly lower risk. The model did not attempt to optimise depth distribution of decompression time, or the use of gas switching, it just compared the effectiveness of two specific models, but for those models the results were convincing.[109]

Another set of experiments was conducted for a series of increasing bottom time exposures at a constant depth, with varying ambient temperature. Four temperature conditions were compared: warm during the bottom sector and decompression, cold during bottom sector and decompression, warm at the bottom and cold during decompression, and cold at the bottom and warm during decompression. The effects were very clear that DCS incidence was much lower for divers that were colder during the ingassing phase and warmer during decompression than the reverse, which has been interpreted as indicating the effects of temperature on perfusion on gas uptake and elimination.[109]

A retrospective statistical analysis of a large data set of case reports of air and nitrox dives published in 2017 indicated that for an acceptable risk of 2% for mild symptoms, and 0.1% for severe symptoms, using a linear-exponential degassing model, the severe symptom risk was the limiting factor. One of the factors complicating this analysis was the variability in methods for distinguishing between mild and severe cases.[108]

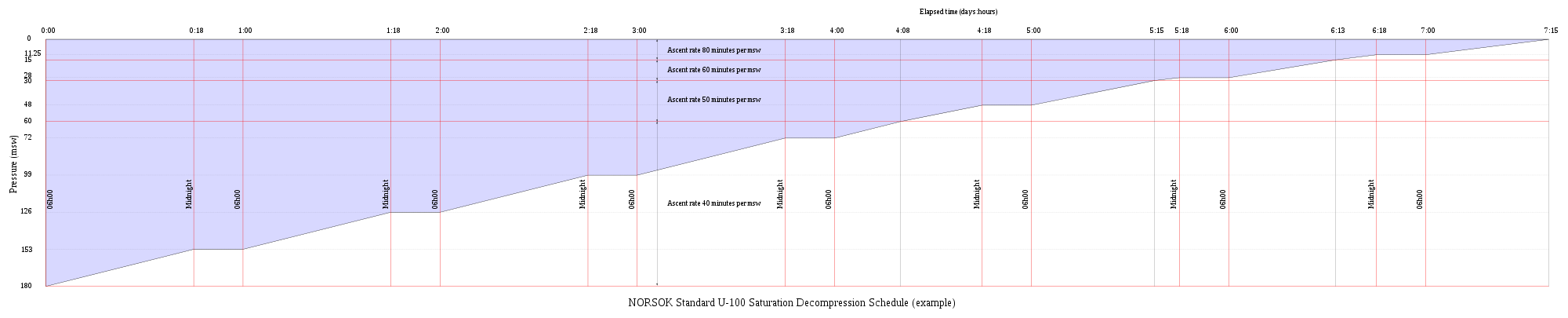

Saturation decompression

[edit]Saturation decompression is a physiological process of transition from a steady state of full saturation with inert gas at raised pressure to standard conditions at normal surface atmospheric pressure. It is a long process during which inert gases are eliminated at a very low rate limited by the slowest affected tissues, and a deviation can cause the formation of gas bubbles which can produce decompression sickness. Most operational procedures rely on experimentally derived parameters describing a continuous slow decompression rate, which may depend on depth and gas mixture.[111]

In saturation diving all tissues are considered saturated and decompression which is safe for the slowest tissues will theoretically be safe for all faster tissues in a parallel model. Direct ascent from air saturation at approximately 7 msw produces venous gas bubbles but not symptomatic DCS. Deeper saturation exposures require decompression to saturation schedules.[112]

The safe rate of decompression from a saturation dive is controlled by the partial pressure of oxygen in the inspired breathing gas.[113] The inherent unsaturation due to the oxygen window allows a relatively fast initial phase of saturation decompression in proportion to the oxygen partial pressure and then controls the rate of further decompression limited by the half-time of inert gas elimination from the slowest compartment.[114] However, some saturation decompression schedules specifically do not allow an decompression to start with an upward excursion.[115] Neither the excursions nor the decompression procedures currently in use (2016) have been found to cause decompression problems in isolation, but there appears to be significantly higher risk when excursions are followed by decompression before non-symptomatic bubbles resulting from excursions have totally resolved. Starting decompression while bubbles are present appears to be the significant factor in many cases of otherwise unexpected decompression sickness during routine saturation decompression.[116]

Application of a bubble model in 1985 allowed successful modelling of conventional decompressions, altitude decompression, no-stop thresholds, and saturation dives using one setting of four global nucleation parameters.[117]

Research continues on saturation decompression modelling and schedule testing. In 2015 a concept named Extended Oxygen Window was used in preliminary tests for a modified saturation decompression model. This model allows a faster rate of decompression at the start of the ascent to utilise the inherent unsaturation due to metabolic use of oxygen, followed by a constant rate limited by oxygen partial pressure of the breathing gas. The period of constant decompression rate is also limited by the allowable maximum oxygen fraction, and when this limit is reached, decompression rate slows down again as the partial pressure of oxygen is reduced. The procedure remains experimental as of May 2016. The goal is an acceptably safe reduction of overall decompression time for a given saturation depth and gas mixture.[111]

Validation of models

[edit]It is important that any theory be validated by carefully controlled testing procedures. As testing procedures and equipment become more sophisticated, researchers learn more about the effects of decompression on the body. Initial research focused on producing dives that were free of recognizable symptoms of decompression sickness (DCS). With the later use of Doppler ultrasound testing, it was realized that bubbles were forming within the body even on dives where no DCI signs or symptoms were encountered. This phenomenon has become known as "silent bubbles". The presence of venous gas emboli is considered a low specificity predictor of decompression sickness, but their absence is recognised to be a sensitive indicator of low risk decompression, therefore the quantitative detection of VGE is thought to be useful as an indicator of decompression stress when comparing decompression strategies, or assessing the efficiency of procedures.[118]

The US Navy 1956 tables were based on limits determined by external DCS signs and symptoms. Later researchers were able to improve on this work by adjusting the limitations based on Doppler testing. However the US Navy CCR tables based on the Thalmann algorithm also used only recognisable DCS symptoms as the test criteria.[119][120] Since the testing procedures are lengthy and costly, and there are ethical limitations on experimental work on human subjects with injury as an endpoint, it is common practice for researchers to make initial validations of new models based on experimental results from earlier trials. This has some implications when comparing models.[121]

This section needs expansion with: NEDU comparison of deep stop/bubble model vs. shallow stop/dissolved state model and reception. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

Efficiency of stop depth distribution

[edit]Deep, short duration dives require a long decompression in comparison to the time at depth, which is inherently inefficient in comparison with saturation diving. Various modifications to decompression algorithms with reasonably validated performance in shallower diving have been used in the effort to develop shorter or safer decompression, but these are generally not supported by controlled experiment and to some extent rely on anecdotal evidence. A widespread belief developed that algorithms based on bubble models and which distribute decompression stops over a greater range of depths are more efficient than the traditional dissolved gas content models by minimising early bubble formation, based on theoretical considerations, largely in the absence of evidence of effectiveness, though there were low incidences of symptomatic decompression sickness. Some evidence relevant to some of these modifications exists and has been analysed, and generally supports the opposite view, that deep stops may lead to greater rates of bubble formation and growth compared to the established systems using shallower stops distributed over the same total decompression time for a given deep profile.[122][79]

The integral of supersaturation over time may be an indicator of decompression stress, either for a given tissue group or for all the tissue groups. Comparison of this indicator calculated for the combined Bühlmann tissue groups for a range of equal duration decompression schedules for the same depth, bottom time, and gas mixtures, has suggested greater overall decompression stress for dives using deep stops, at least partly due to continued ingassing of slower tissues during the deep stops.[79]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

Effects of inert gas component changes