Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

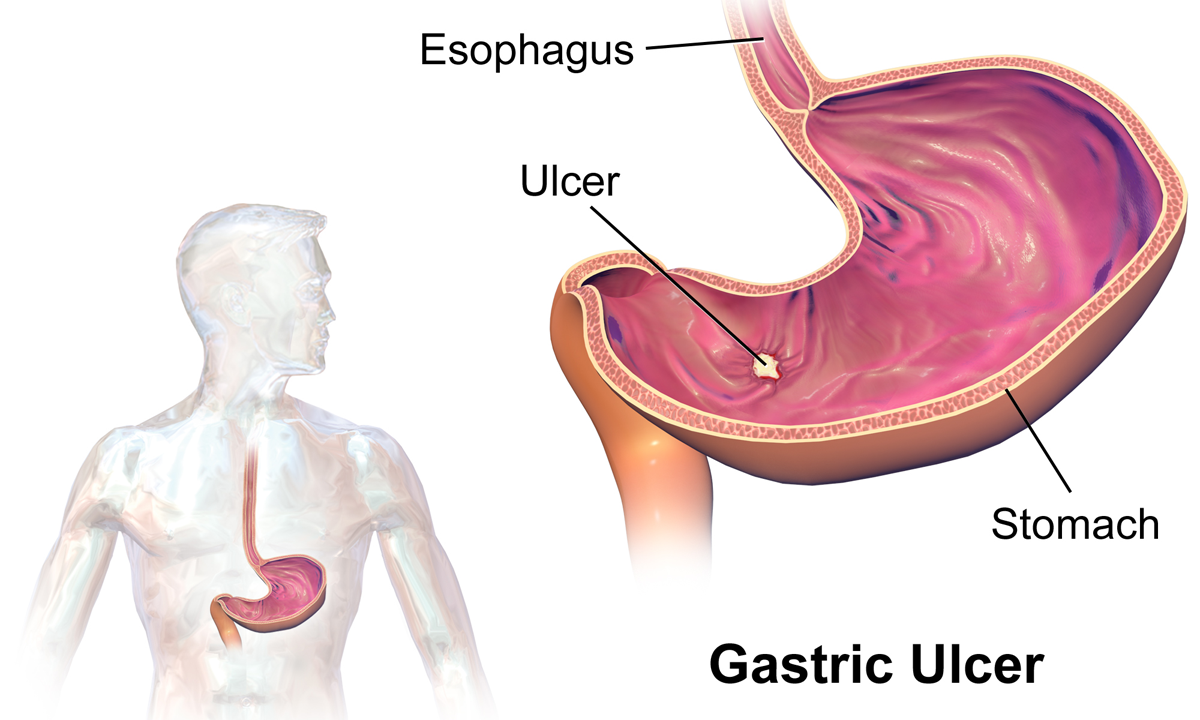

Peptic ulcer disease

View on Wikipedia

Peptic ulcer disease refers to damage of the inner part of the stomach's gastric mucosa (lining of the stomach), the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while one in the first part of the intestines is a duodenal ulcer.[1] The most common symptoms of a duodenal ulcer are waking at night with upper abdominal pain, and upper abdominal pain that improves with eating.[1] With a gastric ulcer, the pain may worsen with eating.[7] The pain is often described as a burning or dull ache.[1] Other symptoms include belching, vomiting, weight loss, or poor appetite.[1] About a third of older people with peptic ulcers have no symptoms.[1] Complications may include bleeding, perforation, and blockage of the stomach.[2] Bleeding occurs in as many as 15% of cases.[2]

Common causes include infection with Helicobacter pylori and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[1] Other, less common causes include tobacco smoking, stress as a result of other serious health conditions, Behçet's disease, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, Crohn's disease, and liver cirrhosis.[1][3] Older people are more sensitive to the ulcer-causing effects of NSAIDs.[1] The diagnosis is typically suspected due to the presenting symptoms with confirmation by either endoscopy or barium swallow.[1] H. pylori can be diagnosed by testing the blood for antibodies, a urea breath test, testing the stool for signs of the bacteria, or a biopsy of the stomach.[1] Other conditions that produce similar symptoms include stomach cancer, coronary heart disease, and inflammation of the stomach lining or gallbladder inflammation.[1]

Diet does not play an important role in either causing or preventing ulcers.[8] Treatment includes stopping smoking, stopping use of NSAIDs, stopping alcohol, and taking medications to decrease stomach acid.[1] The medication used to decrease acid is usually either a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or an H2 blocker, with four weeks of treatment initially recommended.[1] Ulcers due to H. pylori are treated with a combination of medications, such as amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and a PPI.[4] Antibiotic resistance is increasing and thus treatment may not always be effective.[4] Bleeding ulcers may be treated by endoscopy, with open surgery typically only used in cases in which it is not successful.[2]

Peptic ulcers are present in around 4% of the population.[1] New ulcers were found in around 87.4 million people worldwide during 2015.[5] About 10% of people develop a peptic ulcer at some point in their life.[9] Peptic ulcers resulted in 267,500 deaths in 2015, down from 327,000 in 1990.[6][10] The first description of a perforated peptic ulcer was in 1670, in Princess Henrietta of England.[2] H. pylori was first identified as causing peptic ulcers by Barry Marshall and Robin Warren in the late 20th century,[4] a discovery for which they received the Nobel Prize in 2005.[11]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Signs and symptoms of a peptic ulcer can include one or more of the following:[12]

- abdominal pain, classically epigastric, strongly correlated with mealtimes. In case of duodenal ulcers, the pain appears about three hours after taking a meal and wakes the person from sleep;

- bloating and abdominal fullness;

- waterbrash (a rush of saliva after an episode of regurgitation to dilute the acid in esophagus, although this is more associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease);

- nausea and copious vomiting;

- loss of appetite and weight loss, in gastric ulcer;

- weight gain, in duodenal ulcer, as the pain is relieved by eating;

- hematemesis (vomiting of blood); this can occur due to bleeding directly from a gastric ulcer or from damage to the esophagus from severe/continuing vomiting.

- melena (tarry, foul-smelling feces due to presence of oxidized iron from hemoglobin);

- rarely, an ulcer can lead to a gastric or duodenal perforation, which leads to acute peritonitis and extreme, stabbing pain,[13] and requires immediate surgery.

A history of heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and use of certain medications can raise the suspicion for peptic ulcer. Medicines associated with peptic ulcer include NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) that inhibit cyclooxygenase and most glucocorticoids (e.g., dexamethasone and prednisolone).[14]

In people over the age of 45 with more than two weeks of the above symptoms, the odds for peptic ulceration are high enough to warrant rapid investigation by esophagogastroduodenoscopy.[citation needed]

The timing of symptoms in relation to the meal may differentiate between gastric and duodenal ulcers. A gastric ulcer would give epigastric pain during the meal, associated with nausea and vomiting, as gastric acid production is increased as food enters the stomach. Pain in duodenal ulcers would be aggravated by hunger and relieved by a meal and is associated with night pain.[15]

Also, the symptoms of peptic ulcers may vary with the location of the ulcer and the person's age. Furthermore, typical ulcers tend to heal and recur, and as a result the pain may occur for few days and weeks and then wane or disappear.[16] Usually, children and the elderly do not develop any symptoms unless complications have arisen.

A burning or gnawing feeling in the stomach area lasting between 30 minutes and 3 hours commonly accompanies ulcers. This pain can be misinterpreted as hunger, indigestion, or heartburn. Pain is usually caused by the ulcer, but it may be aggravated by the stomach acid when it comes into contact with the ulcerated area. The pain caused by peptic ulcers can be felt anywhere from the navel up to the sternum, it may last from a few minutes to several hours, and it may be worse when the stomach is empty. Also, sometimes the pain may flare at night, and it can commonly be temporarily relieved by eating foods that buffer stomach acid or by taking anti-acid medication.[17] However, peptic ulcer disease symptoms may be different for everyone.[18]

Complications

[edit]

- Gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common complication. Sudden large bleeding can be life-threatening.[19][20] It is associated with 5% to 10% death rate.[15]

- Perforation (a hole in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract) following a gastric ulcer often leads to catastrophic consequences if left untreated. Erosion of the gastrointestinal wall by the ulcer leads to spillage of the stomach or intestinal contents into the abdominal cavity, leading to an acute chemical peritonitis.[21] The first sign is often sudden intense abdominal pain,[15] as seen in Valentino's syndrome. Posterior gastric wall perforation may lead to bleeding due to the involvement of gastroduodenal artery that lies posterior to the first part of the duodenum.[22] The death rate in this case is 20%.[15]

- Penetration is a form of perforation in which the hole leads to and the ulcer continues into adjacent organs such as the liver and pancreas.[16]

- Gastric outlet obstruction (stenosis) is a narrowing of the pyloric canal by scarring and swelling of the gastric antrum and duodenum due to peptic ulcers. The person often presents with severe vomiting.[15]

- Cancer is included in the differential diagnosis (elucidated by biopsy), Helicobacter pylori as the etiological factor making it 3 to 6 times more likely to develop stomach cancer from the ulcer.[16] The risk for developing gastrointestinal cancer also appears to be slightly higher with gastric ulcers.[23]

Cause

[edit]H. pylori

[edit]Helicobacter pylori is one of the major causative factors of peptic ulcer disease. It secretes urease to create an alkaline environment, which is suitable for its survival. It expresses blood group antigen-binding adhesin (BabA) and outer inflammatory protein adhesin (OipA), which enables it to attach to the gastric epithelium. The bacterium also expresses virulence factors such as CagA and PicB, which cause stomach mucosal inflammation. The VacA gene encodes for vacuolating cytotoxin, but its mechanism of causing peptic ulcers is unclear. Such stomach mucosal inflammation can be associated with hyperchlorhydria (increased stomach acid secretion) or hypochlorhydria (reduced stomach acid secretion). Inflammatory cytokines inhibit the parietal cell acid secretion. H. pylori also secretes certain products that inhibit hydrogen potassium ATPase; activate calcitonin gene-related peptide sensory neurons, which increases somatostatin secretion to inhibit acid production by parietal cells; and inhibit gastrin secretion. This reduction in acid production causes gastric ulcers.[15] On the other hand, increased acid production at the pyloric antrum is associated with duodenal ulcers in 10% to 15% of H. pylori infection cases. In this case, somatostatin production is reduced and gastrin production is increased, leading to increased histamine secretion from the enterochromaffin cells, thus increasing acid production. An acidic environment at the antrum causes metaplasia of the duodenal cells, causing duodenal ulcers.[15]

Human immune response toward the bacteria also determines the emergence of peptic ulcer disease. The human IL1B gene encodes for Interleukin 1 beta, and other genes that encode for tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and Lymphotoxin alpha also play a role in gastric inflammation.[15]

NSAIDs

[edit]Taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin[24] can increase the risk of peptic ulcer disease by four times compared to non-users. The risk of getting a peptic ulcer is two times for aspirin users. Risk of bleeding increases if NSAIDs are combined with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), corticosteroids, antimineralocorticoids, and anticoagulants. The gastric mucosa protects itself from gastric acid with a layer of mucus, the secretion of which is stimulated by certain prostaglandins. NSAIDs block the function of cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1), which is essential for the production of these prostaglandins. Besides this, NSAIDs also inhibit stomach mucosa cells proliferation and mucosal blood flow, reducing bicarbonate and mucus secretion, which reduces the integrity of the mucosa. Another type of NSAIDs, called COX-2 selective anti-inflammatory drugs (such as celecoxib), preferentially inhibit COX-2, which is less essential in the gastric mucosa. This reduces the probability of getting peptic ulcers; however, it can still delay ulcer healing for those who already have a peptic ulcer.[15] Peptic ulcers caused by NSAIDs differ from those caused by H. pylori as the latter's appear as a consequence of inflammation of the mucosa (presence of neutrophil and submucosal edema), the former instead as a consequence of a direct damage of the NSAID molecule against COX enzymes, altering the hydrophobic state of the mucus, the permeability of the lining epithelium and mitochondrial machinery of the cell itself. In this way NSAID ulcers tend to complicate faster and dig deeper in the tissue, causing more complications – often asymptomatically – until a great portion of the tissue is involved.[25][26]

Stress

[edit]Physiological (not psychological) stress due to serious health problems, such as those requiring treatment in an intensive care unit, is well described as a cause of peptic ulcers, which are also known as stress ulcers.[3]

While chronic life stress was once believed to be the main cause of ulcers, this is no longer the case.[27] It is, however, still occasionally believed to play a role.[27] This may be due to the well-documented effects of stress on gastric physiology, increasing the risk in those with other causes, such as H. pylori or NSAID use.[28]

Diet

[edit]Dietary factors, such as spice consumption, were hypothesized to cause ulcers until the late 20th century, but have been shown to be of relatively minor importance.[29] Caffeine and coffee, also commonly thought to cause or exacerbate ulcers, appear to have little effect.[30][31] Similarly, while studies have found that alcohol consumption increases risk when associated with H. pylori infection, it does not seem to independently increase risk. Even when coupled with H. pylori infection, the increase is modest in comparison to the primary risk factor.[32][33][nb 1]

Other

[edit]Other causes of peptic ulcer disease include gastric ischaemia, drugs, metabolic disturbances, cytomegalovirus (CMV), upper abdominal radiotherapy, Crohn's disease, and vasculitis.[15] Gastrinomas (Zollinger–Ellison syndrome), or rare gastrin-secreting tumors, also cause multiple and difficult-to-heal ulcers.[34]

It is still unclear whether smoking increases the risk of getting peptic ulcers.[15]

Diagnosis

[edit]

The diagnosis is mainly established based on the characteristic symptoms. Stomach pain is the most common sign of a peptic ulcer.[12]

More specifically, peptic ulcers erode the muscularis mucosae, at minimum reaching to the level of the submucosa (contrast with erosions, which do not involve the muscularis mucosae).[35]

Confirmation of the diagnosis is made with the help of tests such as endoscopies or barium contrast x-rays. The tests are typically ordered if the symptoms do not resolve after a few weeks of treatment, or when they first appear in a person who is over age 45 or who has other symptoms such as weight loss, because stomach cancer can cause similar symptoms. Also, when severe ulcers resist treatment, particularly if a person has several ulcers or the ulcers are in unusual places, a doctor may suspect an underlying condition that causes the stomach to overproduce acid.[16]

An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), a form of endoscopy, also known as a gastroscopy, is carried out on people in whom a peptic ulcer is suspected. It is also the gold standard of diagnosis for peptic ulcer disease.[15] By direct visual identification, the location and severity of an ulcer can be described. Moreover, if no ulcer is present, EGD can often provide an alternative diagnosis.

One of the reasons that blood tests are not reliable for accurate peptic ulcer diagnosis on their own is their inability to differentiate between past exposure to the bacteria and current infection. Additionally, a false negative result is possible with a blood test if the person has recently been taking certain drugs, such as antibiotics or proton-pump inhibitors.[36]

The diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori can be made by:

- Urea breath test (noninvasive and does not require EGD);

- Direct culture from an EGD biopsy specimen; this is difficult and can be expensive. Most labs are not set up to perform H. pylori cultures;

- Direct detection of urease activity in a biopsy specimen by rapid urease test;[15]

- Measurement of antibody levels in the blood (does not require EGD). It is still somewhat controversial whether a positive antibody without EGD is enough to warrant eradication therapy;

- Stool antigen test;[37]

- Histological examination and staining of an EGD biopsy.

The breath test uses radioactive carbon to detect H. pylori.[38] To perform this exam, the person is asked to drink a tasteless liquid that contains the carbon as part of the substance that the bacteria breaks down. After an hour, the person is asked to blow into a sealed bag. If the person is infected with H. pylori, the breath sample will contain radioactive carbon dioxide. This test provides the advantage of being able to monitor the response to treatment used to kill the bacteria.

The possibility of other causes of ulcers, notably malignancy (gastric cancer), needs to be kept in mind. This is especially true in ulcers of the greater curvature of the stomach; most are also a consequence of chronic H. pylori infection.

If a peptic ulcer perforates, air will leak from inside the gastrointestinal tract (which always contains some air) to the peritoneal cavity (which normally never contains air). This leads to "free gas" within the peritoneal cavity. If the person stands, as when having a chest X-ray, the gas will float to a position underneath the diaphragm. Therefore, gas in the peritoneal cavity, shown on an erect chest X-ray or supine lateral abdominal X-ray, is an omen of perforated peptic ulcer disease.

Classification

[edit]

- Esophagus

- Stomach

- Ulcers

- Duodenum

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscle

Peptic ulcers are a form of acid–peptic disorder. Peptic ulcers can be classified according to their location and other factors.

By location

[edit]- Duodenum (called duodenal ulcer)

- Esophagus (called esophageal ulcer)

- Stomach (called gastric ulcer)

- Meckel's diverticulum (called Meckel's diverticulum ulcer; is very tender with palpation)

Modified Johnson

[edit]- Type I: Ulcer along the body of the stomach, most often along the lesser curve at incisura angularis along the locus minoris resistantiae. Not associated with acid hypersecretion.

- Type II: Ulcer in the body in combination with duodenal ulcers. Associated with acid oversecretion.

- Type III: In the pyloric channel within 3 cm of pylorus. Associated with acid oversecretion.

- Type IV: Proximal gastroesophageal ulcer.

- Type V: Can occur throughout the stomach. Associated with the chronic use of NSAIDs (such as ibuprofen).

Macroscopic appearance

[edit]

Gastric ulcers are most often localized on the lesser curvature of the stomach. The ulcer is a round to oval parietal defect ("hole"), 2–4 cm diameter, with a smooth base and perpendicular borders. These borders are not elevated or irregular in the acute form of peptic ulcer, and regular but with elevated borders and inflammatory surrounding in the chronic form. In the ulcerative form of gastric cancer, the borders are irregular. Surrounding mucosa may present radial folds, as a consequence of the parietal scarring.[citation needed]

Microscopic appearance

[edit]

A gastric peptic ulcer is a mucosal perforation that penetrates the muscularis mucosae and lamina propria, usually produced by acid-pepsin aggression. Ulcer margins are perpendicular and present chronic gastritis. During the active phase, the base of the ulcer shows four zones: fibrinoid necrosis, inflammatory exudate, granulation tissue and fibrous tissue. The fibrous base of the ulcer may contain vessels with thickened wall or with thrombosis.[39]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]

Conditions that may appear similar include:

Prevention

[edit]Prevention of peptic ulcer disease for those who are taking NSAIDs (with low cardiovascular risk) can be achieved by adding a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), an H2 antagonist, or misoprostol.[15] NSAIDs of the COX-2 inhibitor type may reduce the rate of ulcers when compared to non-selective NSAIDs.[15] PPI is the most popular agent in peptic ulcer prevention.[15] However, there is no evidence that H2 antagonists can prevent stomach bleeding for those taking NSAIDs.[15] Although misoprostol is effective in preventing peptic ulcer, its properties of promoting abortion and causing gastrointestinal distress limit its use.[15] For those with high cardiovascular risk, naproxen with PPI can be a useful choice.[15] Otherwise, low-dose aspirin, celecoxib, and PPI can also be used.[15]

Management

[edit]

Eradication therapy

[edit]Once the diagnosis of H. pylori is confirmed, the first-line treatment would be a triple regimen in which pantoprazole and clarithromycin are combined with either amoxicillin or metronidazole. This treatment regimen can be given for 7–14 days. However, its effectiveness in eradicating H. pylori has been reducing from 90% to 70%. However, the rate of eradication can be increased by doubling the dosage of pantoprazole or increasing the duration of treatment to 14 days. Quadruple therapy (pantoprazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and metronidazole) can also be used. The quadruple therapy can achieve an eradication rate of 90%. If the clarithromycin resistance rate is higher than 15% in an area, the usage of clarithromycin should be abandoned. Instead, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy can be used (pantoprazole, bismuth citrate, tetracycline, and metronidazole) for 14 days. The bismuth therapy can also achieve an eradication rate of 90% and can be used as second-line therapy when the first-line triple-regimen therapy has failed.

NSAIDs-induced ulcers

[edit]NSAID-associated ulcers heal in six to eight weeks provided the NSAIDs are withdrawn with the introduction of proton pump inhibitors (PPI).[15]

Bleeding

[edit]

For those with bleeding peptic ulcers, fluid replacement with crystalloids is sometimes given to maintain volume in the blood vessels. Maintaining haemoglobin at greater than 7 g/dL (70 g/L) through restrictive blood transfusion has been associated with reduced rate of death. Glasgow-Blatchford score is used to determine whether a person should be treated inside a hospital or as an outpatient. Intravenous PPIs can suppress stomach bleeding more quickly than oral ones. A neutral stomach pH is required to keep platelets in place and prevent clot lysis. Tranexamic acid and antifibrinolytic agents are not useful in treating peptic ulcer disease.[15]

Early endoscopic therapy can help to stop bleeding by using cautery, endoclip, or epinephrine injection. Treatment is indicated if there is active bleeding in the stomach, visible vessels, or an adherent clot. Endoscopy is also helpful in identifying people who are suitable for hospital discharge. Prokinetic agents such as erythromycin and metoclopramide can be given before endoscopy to improve endoscopic view. Either high- or low-dose PPIs are equally effective in reducing bleeding after endoscopy. High-dose intravenous PPI is defined as a bolus dose of 80 mg followed by an infusion of 8 mg per hour for 72 hours—in other words, the continuous infusion of PPI of greater than 192 mg per day. Intravenous PPI can be changed to oral once there is no high risk of rebleeding from peptic ulcer.[15]

For those with hypovolemic shock and ulcer size of greater than 2 cm, there is a high chance that the endoscopic treatment would fail. Therefore, surgery and angiographic embolism are reserved for these complicated cases. However, there is a higher rate of complication for those who underwent surgery to patch the stomach bleeding site when compared to repeated endoscopy. Angiographic embolisation has a higher rebleeding rate but a similar rate of death to surgery.[15]

Anticoagulants

[edit]According to expert opinion, for those who are already on anticoagulants, the international normalized ratio (INR) should be kept at 1.5. For aspirin users who required endoscopic treatment for bleeding peptic ulcer, there is two times increased risk of rebleeding but with ten times reduced risk of death at eight weeks following the resumption of aspirin. For those who were on double antiplatelet agents for indwelling stent in blood vessels, both antiplatelet agents should not be stopped because there is a high risk of stent thrombosis. For those who were under warfarin treatment, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), vitamin K, prothrombin complex concentrates, or recombinant factor VIIa can be given to reverse the effect of warfarin. High doses of vitamin K should be avoided to reduce the time for rewarfarinisation once the stomach bleeding has stopped. Prothrombin complex concentrates are preferred for severe bleeding. Recombinant factor VIIa is reserved for life-threatening bleeding because of its high risk of thromboembolism.[15] Direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) are recommended instead of warfarin as they are more effective in preventing thromboembolism. In case of bleeding caused by DOAC, activated charcoal within four hours is the antidote of choice.

Epidemiology

[edit]

The lifetime risk for developing a peptic ulcer is approximately 5% to 10%[9][15] with the rate of 0.1% to 0.3% per year.[15] Peptic ulcers resulted in 301,000 deaths in 2013, down from 327,000 in 1990.[10]

In Western countries, the percentage of people with H. pylori infections roughly matches age (i.e., 20% at age 20, 30% at age 30, 80% at age 80, etc.). Prevalence is higher in third world countries, where it is estimated at 70% of the population, whereas developed countries show a maximum of a 40% ratio. Overall, H. pylori infections show a worldwide decrease, more so in developed countries. Transmission occurs via food, contaminated groundwater, or human saliva (such as from kissing or sharing food utensils).[41]

Peptic ulcer disease had a tremendous effect on morbidity and mortality until the last decades of the 20th century when epidemiological trends started to point to an impressive fall in its incidence. The reason that the rates of peptic ulcer disease decreased is thought to be the development of new effective medication and acid suppressants and the rational use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[15]

History

[edit]John Lykoudis, a general practitioner in Greece, treated people for peptic ulcer disease with antibiotics beginning in 1958, long before it was commonly recognized that bacteria were a dominant cause for the disease.[42]

Helicobacter pylori was identified in 1982 by two Australian scientists, Robin Warren and Barry J. Marshall, as a causative factor for ulcers.[43] In their original paper, Warren and Marshall contended that most gastric ulcers and gastritis were caused by colonization with this bacterium, not by stress or spicy food, as had been assumed before.[44]

The H. pylori hypothesis was still poorly received,[45] so in an act of self-experimentation Marshall drank a Petri dish containing a culture of organisms extracted from a person with an ulcer and five days later developed gastritis. His symptoms disappeared after two weeks, but he took antibiotics to kill the remaining bacteria at the urging of his wife, since halitosis is one of the symptoms of infection.[46] This experiment was published in 1984 in the Australian Medical Journal and is among the most cited articles from the journal.

In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with other government agencies, academic institutions, and industry, launched a national education campaign to inform health care providers and consumers about the link between H. pylori and ulcers. This campaign reinforced the news that ulcers are a curable infection and that health can be greatly improved and money saved by disseminating information about H. pylori.[47]

In 2005, the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Marshall and his long-time collaborator Warren "for their discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease." Marshall continues research related to H. pylori and runs a molecular biology lab at UWA in Perth, Western Australia.

A 1998 New England Medical Journal study found that mastic gum, a tree resin extract, actively eliminated the H. pylori bacteria.[48] However, multiple subsequent studies (in mice and in vivo) have found no effect of using mastic gum on reducing H. pylori levels.[49][50]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sonnenberg in his study cautiously concludes that, among other potential factors that were found to correlate to ulcer healing, "moderate alcohol intake might [also] favor ulcer healing." (p. 1066)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Najm WI (September 2011). "Peptic ulcer disease". Primary Care. 38 (3): 383–94, vii. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2011.05.001. PMID 21872087.

- ^ a b c d e Milosavljevic T, Kostić-Milosavljević M, Jovanović I, Krstić M (2011). "Complications of peptic ulcer disease". Digestive Diseases. 29 (5): 491–3. doi:10.1159/000331517. PMID 22095016. S2CID 25464311.

- ^ a b c Steinberg KP (June 2002). "Stress-related mucosal disease in the critically ill patient: risk factors and strategies to prevent stress-related bleeding in the intensive care unit". Critical Care Medicine. 30 (6 Suppl): S362–4. doi:10.1097/00003246-200206001-00005. PMID 12072662.

- ^ a b c d Wang AY, Peura DA (October 2011). "The prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori-associated peptic ulcer disease and upper gastrointestinal bleeding throughout the world". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America. 21 (4): 613–35. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2011.07.011. PMID 21944414.

- ^ a b "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. October 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, Casey DC, Charlson FJ, Chen AZ, Coates MM, Coggeshall M, Dandona L, Dicker DJ, Erskine HE, Ferrari AJ, Fitzmaurice C, Foreman K, Forouzanfar MH, Fraser MS, Fullman N, Gething PW, Goldberg EM, Graetz N, Haagsma JA, Hay SI, Huynh C, Johnson CO, Kassebaum NJ, Kinfu Y, Kulikoff XR (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Rao SD (2014). Clinical Manual of Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 526. ISBN 978-81-312-3871-4.

- ^ "Eating, Diet, & Nutrition for Peptic Ulcers (Stomach or Duodenal Ulcers)". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 13 July 2025.

- ^ a b Snowden FM (October 2008). "Emerging and reemerging diseases: a historical perspective". Immunological Reviews. 225 (1): 9–26. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00677.x. PMC 7165909. PMID 18837773.

- ^ a b "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. January 2015. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2005". nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Symptoms & Causes of Peptic Ulcers (Stomach or Duodenal Ulcers) – NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ Bhat S (2013). SRB's Manual of Surgery. JP Medical. p. 364. ISBN 978-93-5025-944-3.

- ^ "Treatment for Peptic Ulcers (Stomach or Duodenal Ulcers) – NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Lanas A, Chan FK (August 2017). "Peptic ulcer disease". Lancet. 390 (10094): 613–624. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32404-7. PMID 28242110. S2CID 4547048.

- ^ a b c d "Peptic Ulcer". Home Health Handbook for Patients & Caregivers. Merck Manuals. October 2006. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011.

- ^ "Peptic ulcer". Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "Ulcer Disease Facts and Myths". Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ Cullen DJ, Hawkey GM, Greenwood DC, Humphreys H, Shepherd V, Logan RF, Hawkey CJ (October 1997). "Peptic ulcer bleeding in the elderly: relative roles of Helicobacter pylori and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs". Gut. 41 (4): 459–62. doi:10.1136/gut.41.4.459. PMC 1891536. PMID 9391242.

- ^ Blackford, John W., Williams, Robert H. (1940). "Fatal Hemorrhage from Peptic Ulcer: One Hundred and Sixteen Cases Collected from Vital Statistics of Seattle During the Years 1935–1939 Inclusive". Journal of the American Medical Association. 115 (21): 1774–1779. doi:10.1001/jama.1940.02810470018005.

- ^ Gossman W, Tuma F, Kamel BG, Cassaro S (2019). "Gastric Perforation". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30137838.

- ^ Weledji EP (9 November 2020). "An Overview of Gastroduodenal Perforation". Frontiers in Surgery. 7 573901. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2020.573901. ISSN 2296-875X. PMC 7680839. PMID 33240923.

- ^ Søgaard KK, Farkas DK, Pedersen L, Lund JL, Thomsen RW, Sørensen HT (2016). "Long-term risk of gastrointestinal cancers in persons with gastric or duodenal ulcers". Cancer Medicine. 5 (6): 1341–1351. doi:10.1002/cam4.680. PMC 4924392. PMID 26923747.

- ^ Chan FK, Graham DY (15 May 2004). "Review article: prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastrointestinal complications--review and recommendations based on risk assessment". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 19 (10): 1051–61. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01935.x. PMID 15142194. S2CID 24654342. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "NSAIDs: When To Use Them and for How Long". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ Ghlichloo I, Gerriets V (2024), "Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31613522, retrieved 7 June 2024

- ^ a b Fink G (February 2011). "Stress controversies: post-traumatic stress disorder, hippocampal volume, gastroduodenal ulceration*". Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 23 (2): 107–17. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02089.x. PMID 20973838. S2CID 30231594.

- ^ Yeomans ND (January 2011). "The ulcer sleuths: The search for the cause of peptic ulcers". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 26 (Suppl 1): 35–41. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06537.x. PMID 21199512. S2CID 42592868.

- ^ For nearly 100 years, scientists and doctors thought that ulcers were caused by stress, spicy food, and alcohol. Treatment involved bed rest and a bland diet. Later, researchers added stomach acid to the list of causes and began treating ulcers with antacids. National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse Archived 5 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ryan-Harshman M, Aldoori W (May 2004). "How diet and lifestyle affect duodenal ulcers. Review of the evidence". Canadian Family Physician. 50: 727–32. PMC 2214597. PMID 15171675.

- ^ Rubin R, Strayer DS, Rubin E (1 February 2011). Rubin's pathology: clinicopathologic foundations of medicine (Sixth ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 623. ISBN 978-1-60547-968-2.

- ^ Salih BA, Abasiyanik MF, Bayyurt N, Sander E (June 2007). "H pylori infection and other risk factors associated with peptic ulcers in Turkish patients: a retrospective study". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (23): 3245–8. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i23.3245. PMC 4436612. PMID 17589905.

- ^ Sonnenberg A, Müller-Lissner SA, Vogel E, Schmid P, Gonvers JJ, Peter P, Strohmeyer G, Blum AL (December 1981). "Predictors of duodenal ulcer healing and relapse". Gastroenterology. 81 (6): 1061–7. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(81)80012-1. PMID 7026344.

- ^ Feliberti E, Hughes MS, Perry RR, Vinik A, Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Dungan K, Grossman A, Hershman JM, Kaltsas G, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, McLachlan R, Morley JE, New M, Perreault L, Purnell J, Rebar R, Singer F, Trence DL, Vinik A, Wilson DP (28 November 2013). "Gastrinoma Zollinger–Ellison-Syndrome". Endotext. PMID 25905301.

- ^ "Peptic Ulcer Disease". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Peptic ulcer". Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ Stenström B, Mendis A, Marshall B (August 2008). "Helicobacter pylori – the latest in diagnosis and treatment". Australian Family Physician. 37 (8): 608–12. PMID 18704207.

- ^ "Tests and diagnosis". Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "ATLAS OF PATHOLOGY". Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Brown LM (2000). "Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission". Epidemiologic Reviews. 22 (2): 283–97. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018040. PMID 11218379.

- ^ Rigas B, Papavasassiliou ED (22 May 2002). "Ch. 7 John Lykoudis. The general practitioner in Greece who in 1958 discovered the etiology of, and a treatment for, peptic ulcer disease.". In Marshall BJ (ed.). Helicobacter pioneers: firsthand accounts from the scientists who discovered helicobacters, 1892–1982. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 74–88. ISBN 978-0-86793-035-1. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016.

- ^ Warren JR, Marshall B (June 1983). "Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis". Lancet. 1 (8336): 1273–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92719-8. PMID 6134060. S2CID 1641856.

- ^ Marshall BJ, Warren JR (June 1984). "Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration". Lancet. 1 (8390): 1311–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91816-6. PMID 6145023. S2CID 10066001.

- ^ Schulz K (9 September 2010). "Stress Doesn't Cause Ulcers! Or, How To Win a Nobel Prize in One Easy Lesson: Barry Marshall on Being ... Right". The Wrong Stuff. Slate. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Van Der Weyden MB, Armstrong RM, Gregory AT (2005). "The 2005 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine". The Medical Journal of Australia. 183 (11–12): 612–4. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb00052.x. PMID 16336147. S2CID 45487832. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009.

- ^ "Ulcer, Diagnosis and Treatment - CDC Bacterial, Mycotic Diseases". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ Huwez FU, Thirlwell D, Cockayne A, Ala'Aldeen DA (December 1998). "Mastic gum kills Helicobacter pylori". The New England Journal of Medicine. 339 (26): 1946. doi:10.1056/NEJM199812243392618. PMID 9874617. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. See also their corrections in the next volume Archived 5 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Loughlin MF, Ala'Aldeen DA, Jenks PJ (February 2003). "Monotherapy with mastic does not eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection from mice". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 51 (2): 367–71. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg057. PMID 12562704.

- ^ Bebb JR, Bailey-Flitter N, Ala'Aldeen D, Atherton JC (September 2003). "Mastic gum has no effect on Helicobacter pylori load in vivo". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 52 (3): 522–3. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg366. PMID 12888582.

External links

[edit]- Gastric ulcer images

- "Peptic Ulcer". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

Peptic ulcer disease

View on GrokipediaClinical presentation

Symptoms

The hallmark symptom of peptic ulcer disease is epigastric pain, typically described as burning or gnawing in quality and localized to the upper abdomen.[3] In patients with duodenal ulcers, this pain often occurs 2 to 3 hours after meals or at night, particularly between 11 p.m. and 2 a.m., due to peak gastric acid secretion, and it may awaken individuals from sleep.[4] Conversely, pain from gastric ulcers tends to arise within 15 to 30 minutes after eating and may be exacerbated by meals.[3] The pain's periodicity often follows a cyclic pattern, lasting for weeks followed by symptom-free intervals of similar duration.[4] Associated symptoms commonly include nausea, vomiting, bloating, a sensation of abdominal fullness, early satiety, and heartburn or acid regurgitation, which affect approximately 46% of patients.[4] These manifestations arise from irritation of the gastric or duodenal mucosa and can contribute to discomfort after eating fatty foods or large meals.[5] Symptom severity is influenced by meal timing; for instance, duodenal ulcer pain may improve with food intake or antacids, providing temporary relief by neutralizing acid, whereas gastric ulcer symptoms often persist or worsen postprandially.[3] Atypical presentations are more frequent in elderly patients, who may experience vague symptoms such as anorexia and unintentional weight loss rather than prominent pain, potentially leading to delayed diagnosis.[3] Additionally, up to 70% of individuals with peptic ulcers are asymptomatic, with this proportion higher among older adults and those using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), where mucosal damage can occur silently.[4] Such cases underscore the importance of considering peptic ulcer disease in at-risk populations, often linked to Helicobacter pylori infection or NSAID use, even without overt symptoms.[5]Complications

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) can lead to several serious complications, with upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding being the most frequent, affecting approximately 10 to 20% of patients with PUD. This complication arises when an ulcer erodes into a blood vessel, resulting in hematemesis (vomiting of blood), melena (black, tarry stools), or hemodynamic instability such as hypotension and tachycardia. Risk stratification for upper GI bleeding often employs the Rockall score, which incorporates factors including age, presence of shock, comorbidities (e.g., renal failure or liver disease), endoscopic diagnosis, and stigmata of recent hemorrhage to predict rebleeding and mortality risks.[6][7][8] Perforation occurs in 5 to 10% of PUD cases and represents a surgical emergency, characterized by sudden, severe abdominal pain that may progress to peritonitis due to leakage of gastric contents into the peritoneal cavity. Patients typically present with abdominal tenderness, rigidity, and signs of systemic inflammation such as fever and leukocytosis. The annual incidence of perforated PUD is estimated at 4 to 14 cases per 100,000 individuals, with a 30-day mortality rate of approximately 23.5%, particularly elevated in older patients or those with delayed diagnosis.[7][9] Gastric outlet obstruction develops in 2 to 5% of PUD patients, often from edema, inflammation, or scarring around the pylorus, leading to symptoms of postprandial vomiting, early satiety, and significant weight loss. Penetration, a less common sequela, involves the ulcer eroding into adjacent structures such as the pancreas, causing referred pain to the back and potential fistula formation. In gastric ulcers specifically, there is a 1 to 2% risk of underlying malignancy, necessitating endoscopic surveillance to rule out gastric cancer.[7][10] Overall mortality from PUD complications ranges from 5 to 10%, with higher rates in elderly patients or those experiencing bleeding (up to 8.6% at 30 days) and even greater in perforation cases. Continuation of risk factors like Helicobacter pylori infection or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use can exacerbate these outcomes.[11][9]Etiology and risk factors

Helicobacter pylori infection

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral-shaped, Gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the gastric mucosa and serves as the primary infectious cause of peptic ulcer disease.[12] This microaerophilic pathogen produces urease, an enzyme that hydrolyzes urea to generate ammonia and carbon dioxide, creating a neutral microenvironment that enables survival in the acidic stomach.[13] The bacterium's flagella facilitate motility, allowing it to penetrate the mucus layer and adhere to epithelial cells.[14] Transmission of H. pylori occurs primarily through fecal-oral or oral-oral routes, often via contaminated water, food, or close person-to-person contact.[15] Prevalence is markedly higher in developing countries, reaching up to 80%, compared to 20-40% in developed nations, with infection rates strongly correlated to low socioeconomic status and overcrowding.[16][17] Upon colonization, H. pylori induces chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa, known as gastritis, by recruiting neutrophils and lymphocytes that release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β and interleukin-8.[14] This inflammatory response disrupts the mucosal barrier, leading to epithelial cell damage and impaired tissue repair.[18] The bacterium is associated with 70-90% of duodenal ulcers and 50-70% of gastric ulcers, conferring a 2- to 6-fold increased risk for peptic ulcer disease overall.[19][20] Additionally, chronic infection elevates the risk of gastric cancer by approximately 6-fold through progressive mucosal atrophy and metaplasia.[21] Key virulence factors include the cytotoxin-associated gene A (cagA) and vacuolating cytotoxin A (vacA), encoded by the cag pathogenicity island and vacA gene, respectively.[22] The CagA protein is injected into epithelial cells via a type IV secretion system, where it disrupts cell polarity, induces cytoskeletal rearrangements, and promotes pro-inflammatory signaling, exacerbating mucosal injury.[18] VacA forms anion-selective channels in cell membranes, causing vacuolation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis in epithelial cells, which further compromises the gastric barrier.[22] Strains possessing both cagA and toxigenic vacA alleles are linked to more severe disease outcomes.[18] Through these mechanisms, H. pylori contributes to acid hypersecretion in duodenal ulcer pathogenesis.[14]NSAID use

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a leading pharmacological cause of peptic ulcer disease, second only to Helicobacter pylori infection. These agents exert their ulcerogenic effects primarily through systemic inhibition of the cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) enzyme, which reduces synthesis of gastroprotective prostaglandins such as prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin. Prostaglandins normally promote mucus and bicarbonate secretion, maintain mucosal blood flow, and inhibit acid production; their depletion thus impairs the gastric mucosal barrier, facilitating acid-induced erosion and ulceration.[23][3][24] Several factors amplify the risk of NSAID-induced ulcers. High-dose or prolonged use significantly elevates incidence, with daily aspirin doses exceeding 325 mg associated with greater mucosal damage compared to lower cardioprotective doses. Concomitant administration of corticosteroids or anticoagulants further heightens vulnerability by exacerbating mucosal fragility and bleeding potential. Elderly patients, due to diminished mucosal repair capacity and higher comorbidity burden, experience a 2- to 4-fold increased risk relative to younger users.[23][25][26] Traditional non-selective NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen and naproxen, inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2 isoforms, leading to a pronounced reduction in protective prostaglandins and thus a higher ulcer risk. In contrast, selective COX-2 inhibitors like celecoxib spare COX-1 to a greater extent, resulting in lower gastrointestinal toxicity—endoscopic studies show up to a 4-fold reduction in ulcer formation compared to traditional NSAIDs—although the risk is not entirely eliminated, particularly at higher doses.[27][28][29] Among regular NSAID users, the point prevalence of endoscopic ulcers ranges from 10% to 30%, with up to 40% of cases remaining asymptomatic and prone to silent progression or complications. NSAIDs preferentially induce gastric ulcers over duodenal ones, with gastric lesions occurring approximately 4 times more frequently due to direct topical irritation and greater impairment of gastric mucosal defenses. The ulcer risk shows synergy with H. pylori infection, where co-occurrence can increase odds by 3- to 6-fold compared to either factor alone.[26][30][31][32]Other risk factors

Dietary factors, such as consumption of spicy foods or acidic foods including citrus fruits (e.g., lemons), do not cause peptic ulcer disease but may irritate the gastric mucosa and exacerbate symptoms in some individuals with existing ulcers, though individual tolerance varies. Evidence on the effects of acidic foods is mixed, with no strong consensus for universal avoidance; major health organizations indicate that diet does not play a significant role in causing or treating ulcers, and specific foods like citrus should only be limited if they personally worsen symptoms.[33][34][35][36] Smoking is a significant modifiable risk factor for peptic ulcer disease, approximately doubling the risk by impairing mucosal blood flow, inhibiting bicarbonate secretion, and delaying ulcer healing, with relative risks typically ranging from 1.5 to 2.0 across studies.[1][37] Current smokers also experience higher rates of ulcer complications and recurrence compared to nonsmokers.[38] Excessive alcohol consumption irritates the gastric and duodenal mucosa, promoting acid production and erosion, though it is not considered a primary cause of peptic ulcer disease. A dose-response relationship exists, with daily ethanol intake exceeding 40 g associated with elevated risk, and heavy drinking (more than 42 drinks per week) conferring a fourfold increase in bleeding ulcers.[1][39] Stress contributes to peptic ulcer development, particularly physiological stress in critical illnesses like burns or severe trauma, which stimulates vagal activity and acid hypersecretion. Psychological stress shows a weaker but positive association, increasing ulcer risk independently of Helicobacter pylori infection or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use.[3][40][41] Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, a rare condition caused by gastrin-secreting tumors (gastrinomas) in the pancreas or duodenum, leads to marked gastric acid hypersecretion and often multiple, refractory peptic ulcers. Diagnosis typically involves elevated fasting serum gastrin levels alongside a basal acid output exceeding 15 mEq/h.[3]00789-0/fulltext) Genetic predisposition influences peptic ulcer susceptibility, with first-degree family history conferring a 2- to 3-fold increased risk, likely due to inherited variations in acid secretion or mucosal defense. Rare genetic conditions, such as primary hyperparathyroidism, are also linked, potentially through hypercalcemia-induced gastrin release and acid overproduction.[42][43] Certain comorbidities elevate the risk of peptic ulcer disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and liver cirrhosis, with odds ratios generally between 1.5 and 2.5 after adjusting for confounders. In cirrhosis, portal hypertension and impaired platelet function contribute to higher ulcer bleeding rates, while COPD may exacerbate risk via chronic inflammation and medication interactions. These factors can synergize with primary etiologies like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use to amplify overall vulnerability.[44][45][46]Pathophysiology

Mucosal defense mechanisms

The gastroduodenal mucosa maintains integrity through a multifaceted system of defense mechanisms that counteract luminal aggressors such as acid and pepsin under normal physiological conditions. These protective strategies operate at pre-epithelial, epithelial, and subepithelial levels, ensuring a delicate balance that prevents tissue damage.[47] Physical barriers form the first line of defense. The mucus layer, secreted by goblet cells, consists of glycoproteins that create a viscoelastic gel approximately 0.2-0.6 mm thick, which shields the epithelium from direct contact with acid and enzymes. Tight junctions between epithelial cells further reinforce this barrier, preventing back-diffusion of hydrogen ions and maintaining epithelial permeability.[47] Chemical defenses neutralize potential threats. Bicarbonate ions are secreted by surface epithelial cells into the mucus gel, creating a pH gradient that maintains near-neutral conditions (approximately pH 7) at the epithelial surface despite acidic luminal contents. Prostaglandins, particularly PGE2, enhance these protections by stimulating mucus and bicarbonate secretion while increasing mucosal blood flow to support nutrient delivery and waste removal.[48][47] Cellular and circulatory factors contribute to ongoing resilience. The gastric epithelium undergoes rapid renewal, with surface mucous cells turning over every 3-5 days through proliferation of stem cells in the gastric isthmus, allowing quick replacement of damaged cells. Mucosal blood flow, regulated locally, delivers oxygen and nutrients while facilitating the removal of excess acid and toxic metabolites.[49][47] Neural and hormonal regulation fine-tunes these defenses. Somatostatin, released from D cells in the gastric mucosa, acts as a paracrine inhibitor of acid secretion by suppressing gastrin and histamine release from nearby cells. Epidermal growth factor (EGF), produced by mucosal cells and salivary glands, promotes epithelial proliferation and repair, enhancing overall mucosal integrity.[50] This equilibrium between defensive mechanisms and controlled aggressive factors like hydrochloric acid and pepsin is essential for mucosal homeostasis; disruptions, such as those induced by Helicobacter pylori infection or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, can impair prostaglandin synthesis or other components, tipping the balance toward injury.[47]Ulcer formation processes

Peptic ulcer formation begins with initial mucosal injury, where gastric acid and pepsin erode the epithelial layer, particularly when protective mechanisms are compromised. This erosion starts superficially in the mucosa but progresses due to ongoing exposure to luminal contents, leading to breaches in the epithelial barrier.[3] The inflammatory response follows, characterized by neutrophil infiltration into the damaged site, which amplifies tissue injury through the release of reactive oxygen species and proteases. Cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) are upregulated in this phase, promoting further inflammation and inhibiting gastric acid secretion, thereby exacerbating epithelial damage and delaying repair.[51][52] In the chronic phase, persistent injury leads to a mucosal defect 5 mm or greater in diameter, extending through the muscularis mucosae and forming a discrete ulcer crater with elevated, fibrotic edges. Healing attempts involve fibrosis for scar formation and angiogenesis to restore blood supply, but continued aggressors like acid exposure hinder complete resolution, resulting in chronic ulceration.[3][53] Ulcer formation varies by location: duodenal ulcers typically develop in the bulb due to high post-pyloric acid load and alkaline duodenal contents, often linked to hypergastrinemia, while gastric ulcers predominate in the antrum or body, influenced by regional differences in mucosal blood flow and H. pylori distribution.[3][54] Healing dynamics under acid suppression therapy, such as proton pump inhibitors, achieve resolution in approximately 80% of cases within 4-8 weeks by reducing acid-mediated erosion. However, factors like continued smoking can delay this process by up to 50% through impaired mucosal blood flow and reduced epidermal growth factor expression.[55]Diagnosis

Clinical assessment

The clinical assessment of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) begins with a detailed history to identify symptom patterns and risk factors that raise suspicion for the condition. Patients often describe epigastric pain that may vary in relation to meals: duodenal ulcers typically cause pain that is relieved by eating or antacids, occurring 1-3 hours after meals or at night, while gastric ulcers may worsen with food intake shortly after meals.[3] A thorough inquiry into medication history, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, and potential exposure to Helicobacter pylori through family or environmental factors is essential, as these are key contributors. Family history of ulcers or gastrointestinal malignancy should also be elicited, as it increases the likelihood of PUD.[56][57] Alarm features in the history warrant heightened concern and prompt further evaluation to exclude complications or alternative diagnoses. These include unintentional weight loss, progressive dysphagia, persistent vomiting, evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding such as melena or hematemesis, anemia, and early satiety suggesting obstruction. To differentiate PUD from functional dyspepsia, the Rome IV criteria are applied: functional dyspepsia requires bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric pain, or burning for at least 3 months, with no evidence of structural disease, whereas PUD symptoms often align more closely with meal-related patterns and risk factors.[58][59] The physical examination focuses on abdominal findings and systemic signs. Epigastric tenderness is a common localized finding upon palpation, reflecting mucosal inflammation.[3] Pallor may indicate chronic anemia from occult blood loss, while tachycardia or hypotension could signal acute bleeding. In cases of suspected perforation, signs such as abdominal guarding, rebound tenderness, and a rigid board-like abdomen are critical. The exam also assesses for dehydration from vomiting or general nutritional status. Risk stratification during assessment helps prioritize patients for urgent intervention. Factors such as age ≥60 years, current smoking, and a history of prior ulcers significantly elevate suspicion for PUD and influence the need for expedited evaluation, as smoking impairs healing and increases recurrence risk.[60] Asymptomatic PUD can occur, particularly in high-risk groups, and assessment should include screening considerations for long-term NSAID users, where ulcers may be incidentally discovered without preceding symptoms.[61] In such cases, history focuses on exposure risks rather than overt complaints to identify silent disease.Endoscopic evaluation

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (EGD), also known as esophagogastroduodenoscopy, serves as the gold standard for diagnosing peptic ulcer disease by providing direct visualization of the mucosal lining in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum.[62] It is particularly indicated for patients ≥60 years with new-onset dyspepsia or those of any age presenting with alarm symptoms such as unexplained weight loss, dysphagia, recurrent vomiting, anemia, or evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, as these features raise suspicion for ulcers or complications.[60] In cases of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding, early EGD within 24 hours of presentation is recommended to confirm the diagnosis, assess severity, and facilitate immediate intervention, correlating with symptom urgency to reduce risks like rebleeding. During EGD, ulcers are identified by their characteristic mucosal breaks exceeding 5 mm in diameter, with location typically in the duodenum or stomach.[62] Endoscopic findings distinguish between clean-based ulcers, which indicate low rebleeding risk, and those with active bleeding or high-risk stigmata. The Forrest classification stratifies bleeding peptic ulcers based on endoscopic appearance to guide therapy:- Ia: Active spurting hemorrhage, indicating ongoing severe bleeding.

- Ib: Active oozing hemorrhage from the ulcer base.

- IIa: Nonbleeding visible vessel, a precursor to rebleeding.

- IIb: Adherent clot over the ulcer.

- IIc: Flat pigmented spot or hematin-covered base.

- III: Clean base without stigmata, signifying recent hemorrhage resolution.