Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Epilepsy

View on Wikipedia

| Epilepsy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Seizure disorder Neurological disability |

| |

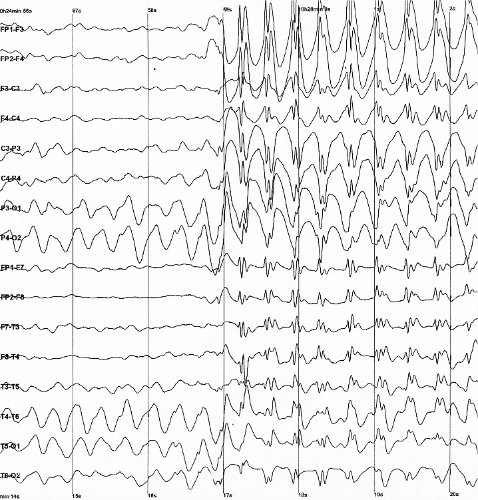

| Generalized 3 Hz spike-and-wave discharges on an electroencephalogram | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Periods of loss of consciousness, abnormal shaking, staring, change in vision, mood changes and/or other cognitive disturbances [1] |

| Duration | Long term[1] |

| Causes | Unknown, brain injury, stroke, brain tumors, infections of the brain, birth defects[1][2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Electroencephalogram, ruling out other possible causes[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Fainting, alcohol withdrawal, electrolyte problems[4] |

| Treatment | Medication, surgery, neurostimulation, dietary changes[5][6] |

| Prognosis | Controllable in 69%[7] |

| Frequency | 51.7 million/0.68% (2021)[8] |

| Deaths | 140,000 (2021)[9] |

Epilepsy is a group of neurological disorders characterized by a tendency for recurrent, unprovoked seizures.[10] A seizure is a sudden burst of abnormal electrical activity in the brain that can cause a variety of symptoms, ranging from brief lapses of awareness or muscle jerks to prolonged convulsions.[1] These episodes can result in physical injuries, either directly, such as broken bones, or through causing accidents. The diagnosis of epilepsy typically requires at least two unprovoked seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart.[11] In some cases, however, it may be diagnosed after a single unprovoked seizure if clinical evidence suggests a high risk of recurrence.[10] Isolated seizures that occur without recurrence risk or are provoked by identifiable causes are not considered indicative of epilepsy.[12]

The underlying cause is often unknown,[11] but epilepsy can result from brain injury, stroke, infections, tumors, genetic conditions, or developmental abnormalities.[13][2][3] Epilepsy that occurs as a result of other issues may be preventable.[1] Diagnosis involves ruling out other conditions that can resemble seizures, and may include neuroimaging, blood tests, and electroencephalography (EEG).[4]

Most cases of epilepsy — approximately 69% — can be effectively controlled with anti-seizure medications,[7] and inexpensive treatment options are widely available. For those whose seizures do not respond to drugs, other approaches, such as surgery, neurostimulation or dietary changes, may be considered.[5][6] Not all cases of epilepsy are lifelong, and many people improve to the point that treatment is no longer needed.[1]

As of 2024[update], approximately 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy, with nearly 80% of cases occurring in low- and middle-income countries.[1] The burden of epilepsy in low-income countries is more than twice that in high-income countries, likely due to higher exposure to risk factors such as perinatal injury, infections, and traumatic brain injury, combined with limited access to healthcare.[14] In 2021, epilepsy was responsible for an estimated 140,000 deaths, an increase from 125,000 in 1990.[9]

Epilepsy is more common in both children and older adults.[15][16] About 5–10% of people will have an unprovoked seizure by the age of 80.[17] The chance of experiencing a second seizure within two years after the first is around 40%.[18][19]

People with epilepsy may be treated differently in various areas of the world and experience varying degrees of social stigma due to the alarming nature of their symptoms.[11][20] In many countries, people with epilepsy face driving restrictions and must be seizure-free for a set period before regaining eligibility to drive.[21] The word epilepsy is from Ancient Greek ἐπιλαμβάνειν, 'to seize, possess, or afflict'.[22]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Epilepsy is characterized by a long-term tendency to experience recurrent, unprovoked seizures.[23] They may vary widely in their presentation depending on the affected brain regions, age of onset, and type of epilepsy.[24]

Seizures

[edit]According to the 2025 classification by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), seizures are grouped into four main classes: focal, generalized, unknown (whether focal or generalized), and unclassified.[25]

Focal seizures

[edit]Focal seizures originate in one area of the brain and may involve localized or distributed networks.[23] For a given seizure type, the site of onset tends to be consistent across episodes. Once initiated, the seizure may remain localized or spread to adjacent areas, and in some cases, may propagate to the opposite hemisphere (contralateral spread).[25]

They are further classified based on the state of consciousness during the episode:[25]

- Focal preserved consciousness seizure: the person remains aware and responsive.

- Focal impaired consciousness seizure: awareness and/or responsiveness are affected.

Experiences known as auras often precede focal seizures.[26] The seizures can include sensory (visual, hearing, or smell), psychic, autonomic, and motor phenomena depending on which part of the brain is involved.[23][27] Muscle jerks may start in a specific muscle group and spread to surrounding muscle groups, a pattern known as a Jacksonian march.[28] Automatisms, or non-consciously generated activities, may occur; these may be simple repetitive movements like smacking the lips or more complex activities such as attempts to pick up something.[28] Some focal seizures can evolve into focal-to-bilateral tonic-clonic seizures, where abnormal brain activity spreads to both hemispheres.[25]

Generalized seizures

[edit]Generalized seizures originate at a specific point within, and quickly spread across both hemispheres through interconnected brain networks. Although the spread is rapid, the onset may appear asymmetric in some cases. These seizures typically impair consciousness from the outset and can take several forms, including:[25]

- Generalized tonic–clonic seizures, often with an initial tonic phase followed by clonic jerking;

- Absence seizures, which may present with eye blinking or automatisms;

- Other generalized seizures, a category that includes tonic, clonic, myoclonic, atonic seizures and epileptic spasms.

Tonic–clonic seizures are among the most recognizable seizure types, typically involving sudden loss of consciousness, stiffening (tonic phase), and rhythmic jerking (clonic phase) of the limbs.[29] This form of seizure — whether focal to bilateral, generalized, or of unknown onset — is given particular emphasis due to their clinical severity; they are associated with the highest risk of injury, medical complications, and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).[25]

Myoclonic seizures involve sudden, brief muscle jerks, which may affect specific muscle groups or the whole body.[30][31] They can cause falls and injury.[30] Absence seizures are characterized by brief lapses in awareness, sometimes accompanied by subtle movements such as blinking or slight head turning.[2] The person typically recovers immediately afterward without confusion. Atonic seizures involve a sudden loss of muscle tone, often resulting in falls.[26]

Triggers and reflex seizures

[edit]Certain external or internal factors may increase the likelihood of a seizure in individuals with epilepsy. These triggers do not cause epilepsy but can lower the seizure threshold in people who are already susceptible. Common triggers include sleep deprivation, stress, fever, illness, menstruation, alcohol, and certain medications. These do not cause seizures by themselves, but lower the threshold in people who are already susceptible.[32][33][34][35]

A small subset of individuals have reflex epilepsy, in which seizures are reliably provoked by specific stimuli. These reflex seizures account for about 6% of epilepsy cases.[36][37] Common triggers include flashing lights (photosensitive epilepsy), sudden sounds, or specific cognitive tasks such as reading or performing calculations. In some epilepsy syndromes, seizures occur more frequently during sleep or upon awakening.[38][39]

Seizure clusters

[edit]Seizure clusters refer to multiple seizures occurring over a short period of time, with incomplete recovery between events. They are distinct from status epilepticus, though the two may overlap. Definitions vary across studies, but seizure clusters are typically described as two or more seizures within 24 hours or a noticeable increase in seizure frequency over a person's usual baseline. Estimates of their prevalence range widely — from 5% to 50% of people with epilepsy — largely due to differing definitions and populations studied.[40][41] Seizure clusters are more common in individuals with drug-resistant epilepsy, high baseline seizure frequency, or certain epilepsy syndromes.[42] They are associated with increased emergency care utilization, worse quality of life, impaired psychosocial functioning, and possibly elevated risk of mortality.[43]

Postictal state

[edit]After the active portion of a seizure (the ictal state) there is typically a period of recovery during which there is confusion, referred to as the postictal state, before a normal level of consciousness returns,[44] lasting minutes to days.[27] This period is marked by confusion, headache, fatigue, or speech and motor disturbances. Some may experience Todd's paralysis, a transient focal weakness.[45] Postictal psychosis occurs in approximately 2% of individuals with epilepsy, particularly after clusters of generalized tonic–clonic seizures.[46][47]

Psychosocial

[edit]Epilepsy can have substantial effects on psychological and social well-being. People with the condition may experience social isolation, stigma, or functional disability, which can contribute to lower educational attainment and reduced employment opportunities. These challenges often extend to family members, who may also encounter stigma and increased caregiving burden.[48]

Several psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders are more common in individuals with epilepsy. These include depression, anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD),[49] and migraine.[50] Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is particularly prevalent among children with epilepsy, occurring three to five times more often than in the general population. ADHD and epilepsy together can markedly affect behavior, learning, and social development.[51] Epilepsy is also more common in children with autism spectrum disorder.[52]

Approximately, one-in-three people with epilepsy have a lifetime history of a psychiatric disorder.[53] This association is thought to reflect a combination of shared neurobiological mechanisms and the psychosocial impact of living with a chronic neurological condition.[54] Some research also suggests that psychiatric conditions such as depression may precede the onset of epilepsy in certain individuals, particularly those with focal epilepsy. However, the nature of this association remains under investigation and may involve shared pathways, diagnostic overlap, or other confounding factors.[55]

Comorbid depression and anxiety are associated with poorer quality of life,[56] increased healthcare utilization, reduced treatment response (including to surgery), and higher mortality.[57] Some studies suggest that these psychiatric conditions may influence quality of life more than seizure type or frequency.[58] Despite their clinical importance, depression and anxiety often go underdiagnosed and undertreated in people with epilepsy.[59]

Causes

[edit]Epilepsy can result from a wide range of genetic and acquired factors, and in many cases, both play a role.[60][61] Acquired causes include serious traumatic brain injury, stroke, brain tumors, and central nervous system infections.[60] Despite advances in diagnostic tools, no clear cause is identified in approximately 50% of cases.[1] The distribution of causes often varies with age. Epilepsies associated with genetic, congenital, or developmental conditions are more common in children, while epilepsy related to stroke or tumors is more frequently seen in older adults.[48]

Seizures may also occur as a direct response to acute health conditions such as stroke, head trauma, metabolic disturbances, or toxic exposures.[62] These are known as acute symptomatic seizures and are distinct from epilepsy, which involves a recurrent tendency to have unprovoked seizures over time.[63]

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classifies the causes of epilepsy into six broad categories: structural, genetic, infectious, metabolic, immune, and unknown. These categories are not mutually exclusive, and more than one may apply in an individual case.[64]

Structural

[edit]Structural causes of epilepsy refer to abnormalities in the anatomy of the brain that increase the risk of seizures. These may be acquired — such as from a stroke, traumatic brain injury, brain tumor, or central nervous system infection — or developmental and genetic in origin, as seen in conditions like focal cortical dysplasia or certain congenital brain malformations. A major example is mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS), a common cause of temporal lobe epilepsy.[65][64]

Traumatic brain injury is estimated to cause between 6% and 20% of epilepsy cases, depending on severity, mechanism, and study population. Mild brain injury increases the risk about two-fold, while severe brain injury increases the risk seven-fold. In those who have experienced a high-powered gunshot wound to the head, the risk is about 50%.[66] Stroke is a major cause of epilepsy, particularly in older adults.[67] Approximately 6% to 10% of individuals who experience a stroke develop epilepsy, most often within the first few years after the event. The risk is highest following severe strokes that involve cortical regions, especially in cases of intracerebral hemorrhage.[68] Brain tumors are implicated in approximately 4% of epilepsy cases, with seizures occurring in nearly 30% of individuals with intracranial neoplasms.[66]

In clinical practice, a structural cause is typically identified through neuroimaging (such as MRI), which reveals an abnormality that plausibly accounts for the individual's seizure semiology and EEG findings. The lesion must be epileptogenic, meaning that it is capable of generating seizures. Infections like encephalitis or brain abscess may lead to permanent structural damage, increasing the risk of epilepsy even after the infection resolves.[64]

Structural damage can also result from perinatal brain injury, such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, especially in low- and middle-income countries where access to prenatal and neonatal care may be limited. When seizures are linked to a clearly defined structural lesion, epilepsy surgery may be considered — particularly in individuals whose seizures do not respond to medication.[64]

Genetics

[edit]Genetic causes of epilepsy are those in which a person's genes directly contribute to the development of seizures. This includes cases where a specific mutation has been identified, as well as situations where the family history and clinical features strongly suggest a genetic basis, even if no known mutation is found. In the updated classification by the ILAE, the term genetic replaces the older term idiopathic, to highlight that these epilepsies arise from inherited or spontaneous changes in a person's biology — not from injury or infection.[64]

Genetic factors are believed to contribute to many cases of epilepsy, either directly or by increasing vulnerability to other causes.[69] Some forms are caused by a single gene defect, which account for around 1–2% of cases. However, most are due to a combination of multiple genes and environmental influences.[13] Many of the genes known to play a role in epilepsy affect how brain cells send electrical signals, especially those involved in ion channels, receptors, or signaling proteins.[30]

Genetics is believed to play an important role in epilepsies by a number of mechanisms. Simple and complex modes of inheritance have been identified for some of them. However, extensive screening have failed to identify many single gene variants of large effect.[70] More recent exome and genome sequencing studies have begun to reveal a number of de novo gene mutations that are responsible for some epileptic encephalopathies, including CHD2 and SYNGAP1[71][72][73] and DNM1, GABBR2, FASN and RYR3.[74]

Some genetic disorders, including phakomatoses such as tuberous sclerosis complex and Sturge–Weber syndrome, are strongly associated with epilepsy.[75]

Infectious

[edit]Infectious causes include infections of the central nervous system that directly affect brain tissue and lead to long-term seizure susceptibility.[66] Examples include herpes simplex encephalitis, which carries a high risk of developing epilepsy, and neurocysticercosis, a major preventable cause of epilepsy in endemic regions. Other infections such as cerebral malaria, toxoplasmosis, and toxocariasis.[66]

Immune

[edit]Immune causes include conditions like autoimmune encephalitis, in which the immune system attacks brain tissue, often presenting with seizures. Certain autoimmune epilepsies are associated with specific autoantibodies, including those against the NMDA receptor, LGI1, and CASPR2. These cases often present with rapid-onset, difficult-to-treat seizures.[64]

Celiac disease has also been associated with epilepsy in rare syndromic forms, such as the triad of epilepsy, cerebral calcifications, and celiac disease.[76][77]

Metabolic

[edit]Metabolic causes of epilepsy include metabolic disorders that disrupt the brain's normal function. In rare cases, epilepsy may result from inborn errors of metabolism, such as mitochondrial diseases, urea cycle disorders, or glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) deficiency. These often present early in life and may be associated with developmental delays, movement disorders, or other neurological symptoms.[64]

Seizures can also occur in the context of acquired metabolic disturbances, such as hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, or hypocalcemia. These seizures are often considered acute symptomatic seizures, and are not epilepsy.[78]

Some forms of malnutrition, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, have been associated with a higher risk of epilepsy, although it remains unclear whether the relationship is causal or due to other contributing factors.[14]

Unknown

[edit]Unknown causes of epilepsy refer to cases where no clear structural, genetic, infectious, immune, or metabolic origin can be identified despite thorough evaluation. This category acknowledges the limits of current diagnostic techniques and scientific understanding. A substantial proportion of epilepsy cases still fall into this group, particularly in regions with limited access to advanced testing.[64]

Mechanism

[edit]Understanding the mechanism of epilepsy involves two related but distinct questions: how the brain develops a long-term tendency to generate seizures (epileptogenesis), and how individual seizures begin and spread (ictogenesis). While these processes are not yet fully understood, research has identified a number of cellular, molecular, and network-level changes that contribute to each.[79]

Seizures

[edit]In a healthy brain, neurons communicate through electrical signals that are generally desynchronized. This activity is tightly regulated by a balance between excitatory and inhibitory influences. Intracellular factors that influence neuronal excitability include the type, number, and distribution of ion channels, as well as alterations in receptor function and gene expression. Extracellular factors include ionic concentrations in the surrounding environment, synaptic plasticity, and the regulation of neurotransmitter breakdown by glial cells.[80][81]

During a seizure, this balance breaks down, leading to a sudden and excessive synchronization of neuronal firing. A localized group of neurons may begin firing together in an abnormal and repetitive pattern, overwhelming normal inhibitory controls. This abnormal activity can remain confined to a specific region of the brain or propagate to other areas. The process by which this transition occurs is known as ictogenesis. It involves a shift in network dynamics, typically beginning with excessive excitatory activity in a susceptible area of cortex — known as a seizure focus — and failure of inhibitory mechanisms to contain it. At the cellular level, ictogenesis is often marked by a paroxysmal depolarizing shift, a characteristic pattern of sustained neuronal depolarization followed by rapid repetitive firing.[82] As excitatory feedback loops engage and inhibition further declines, the seizure may become self-sustaining and spread to other regions of the brain.[83]

There is evidence that epileptic seizures are usually not a random event. Seizures are often brought on by factors (also known as triggers) such as stress, excessive alcohol use, flickering light, or a lack of sleep, among others. The term seizure threshold is used to indicate the amount of stimulus necessary to bring about a seizure; this threshold is lowered in epilepsy.[84] The seizures can be described on different scales, from the cellular level[85] to the whole brain.[86]

Epilepsy

[edit]While ictogenesis explains how individual seizures arise, it does not account for why the brain develops a persistent tendency to generate them. This longer-term process is known as epileptogenesis — the sequence of biological events that transforms a previously non-epileptic brain into one capable of producing spontaneous seizures. It can occur after a wide range of brain insults, including traumatic brain injury, stroke, central nervous system infections, brain tumors, or prolonged seizures (such as status epilepticus). In most cases, no clear cause is identified. Although not fully understood, it involves a range of biological changes, including neuronal loss, synaptic reorganization, gliosis, neuroinflammation, and disruption of the blood–brain barrier.[79][87]

Together, these changes contribute to the formation of hyperexcitable neural networks, often anchored around a seizure focus. Once established, this pathological network increases the brain's susceptibility to seizures, even in the absence of ongoing injury. Although many of the processes underlying ictogenesis and epileptogenesis have been identified, the exact mechanisms by which the brain transitions into a seizure or becomes epileptic remain unknown.[87]

Diagnosis

[edit]The diagnosis of epilepsy is primarily clinical, based on a thorough evaluation of the person's history, seizure features, and risk of recurrence. Diagnostic tests such as electroencephalograms and neuroimaging can support the diagnosis. Clinicians must also distinguish epileptic seizures from other conditions that can mimic them and determine whether the event was provoked by an acute, reversible cause or if it suggests a long-term tendency for unprovoked seizures.[26][23]

Definition

[edit]According to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), a diagnosis of epilepsy can be made when any one of the following criteria is met:[10]

- At least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart

- One unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years

- Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome

The ILAE also introduced the concept of resolved epilepsy, which applies to individuals who are past the typical age range for an age-dependent syndrome, or who have remained seizure-free for at least 10 years, including the last 5 years without medication.[10]

This 2014 practical definition built upon the broader 2005 conceptual framework, which defined epilepsy as a disorder involving an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures. The updated criteria incorporated recurrence risk and reflected the realities of clinical decision-making. While widely adopted in clinical settings, other definitions—such as the traditional "two unprovoked seizures" rule still used by the World Health Organization — remain appropriate in epidemiology and public health contexts, provided they are clearly stated. The 2014 revision also shifted terminology, referring to epilepsy as a disease rather than a disorder, to reflect its medical seriousness and public health impact.[88][10]

Classification

[edit]

Once epilepsy is diagnosed, the ILAE recommends a three-level framework to guide further classification and management:[64]

- Identify the seizure type, based on clinical features and EEG (e.g., focal aware seizure, generalized absence)

- Determine the epilepsy type, such as focal, generalized, combined, or unknown

- Identify an epilepsy syndrome, if applicable

Not all levels can always be determined; in some cases, only the seizure type is identifiable. The etiology — whether structural, genetic, infectious, metabolic, immune, or unknown — should be considered at each stage of classification, as it often influences treatment and prognosis.[89][64]

The classification of epilepsies has evolved significantly over time.[90] Earlier systems emphasized seizure location and used terms such as "partial" or "cryptogenic," which have been replaced in the modern framework.[91][92] The current system, introduced in 2017, reflects advances in neuroimaging, genetics, and clinical understanding, and allows for a more individualized and dynamic diagnostic approach.[93]

Syndromes

[edit]An epilepsy syndrome is a specific diagnosis based on a combination of features, including seizure types, age of onset, EEG patterns, imaging findings, and associated symptoms or comorbidities. In many cases, a known genetic or structural cause may also support the diagnosis. Recognizing a syndrome can guide treatment decisions, inform prognosis, and provide clarity for individuals and families navigating an epilepsy diagnosis.[94][95]

Some syndromes are self-limited and age-dependent, such as childhood absence epilepsy, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, and self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes.[63] These typically respond well to treatment or remit with age. In contrast, more severe syndromes fall under the category of developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEEs).[96] These include Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, West syndrome, and Dravet syndrome, which are associated with early onset, drug-resistant seizures, and significant neurodevelopmental impairments.[97]

Some epilepsy syndromes do not yet fit neatly within current etiological categories, particularly when no definitive cause has been identified. In many cases, a genetic cause is presumed based on age of onset, family history, and electroclinical features, even if no mutation has been found. As genetic and neuroimaging technologies continue to evolve, the classification of epilepsy syndromes is expected to become more precise.[89]

Tests

[edit]

The diagnostic evaluation of epilepsy begins with confirming whether the reported event was in fact a seizure. A detailed clinical history remains essential, supported by eyewitness accounts and, when possible, video recordings. The initial assessment aims to distinguish epileptic seizures from common mimics such as syncope, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, or transient ischemic attacks.[98][99]

Following clinical evaluation, selected tests may be used to rule out acute causes and seizure mimics. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is recommended for all individuals presenting with a first seizure, to screen for cardiac arrhythmias and other cardiovascular conditions that may resemble epilepsy. Blood tests may be performed to identify metabolic disturbances such as hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, or renal and hepatic dysfunction, particularly in acute settings.[100]

Once epilepsy is suspected, electroencephalography (EEG) is used to support the diagnosis, classify seizure types, and help identify specific epilepsy syndromes. A routine EEG may include activation techniques such as hyperventilation or photic stimulation. However, a normal EEG does not rule out epilepsy. When initial EEG findings are inconclusive, further studies such as sleep-deprived EEG, ambulatory EEG, or long-term video EEG monitoring may be considered.[100]

Neuroimaging, usually with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is recommended to detect structural causes of epilepsy. If MRI is contraindicated or unavailable, computed tomography (CT) may be considered. Imaging should be interpreted by radiologists with expertise in epilepsy.[100]

Additional tests may be guided by clinical context. Genetic testing may be considered in individuals with early-onset epilepsy, developmental delay, or features of a known genetic epilepsy syndrome. Testing for neuronal antibodies may be appropriate in suspected cases of autoimmune encephalitis, particularly when seizures are new-onset, rapidly progressive, or resistant to standard treatment. Metabolic testing may be pursued in infants or children with unexplained epilepsy, especially when developmental regression or multisystem involvement is present.[100]

Serum prolactin may occasionally be measured after a suspected seizure, particularly to help distinguish epileptic seizures from non-epileptic events. While it can be elevated following certain seizure types, the test lacks sufficient sensitivity and specificity and is not recommended for routine use.[101]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]A number of conditions can resemble epileptic seizures, leading to potential misdiagnosis. Accurate diagnosis is essential, as inappropriate treatment may delay effective care or cause harm. Common mimics include fainting (syncope), psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), transient ischemic attacks, migraine, narcolepsy, and various sleep or movement disorders.[102][103] In children, reflux, breath-holding spells, and parasomnias such as night terrors may also resemble seizures.[103]

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) are a particularly important consideration, especially in individuals with refractory epilepsy. PNES are involuntary episodes that resemble epileptic seizures but are not associated with abnormal electrical discharges. They are classified as functional neurological disorders and are typically associated with psychological distress or trauma. Studies suggest that approximately 20% of individuals referred to epilepsy centers are diagnosed with PNES,[17] and up to 10% of these individuals also have coexisting epilepsy.[104] Differentiating between the two can be difficult and often requires prolonged video EEG monitoring.[104]

Misdiagnosis remains a significant concern in epilepsy. Reported rates vary widely — from 2% to 71% — depending on factors such as clinical setting, patient population, diagnostic criteria, and physician expertise.[105][106]

Prevention

[edit]Although many causes of epilepsy are not preventable, several known risk factors are modifiable. Perinatal care, including prevention of birth trauma, hypoxia, and maternal infections, can lower the risk of epilepsy in infants.[7] Vaccination programs, especially against neurotropic infections such as measles and meningitis, play a key role in preventing epilepsy caused by central nervous system infections. In low- and middle-income countries, neurocysticercosis remains a major preventable cause of epilepsy, which can be reduced through improved sanitation and food safety.[14][20] Eliminating or reducing risk factors for seizures in older adults such as inactivity, smoking, diabetes, high blood pressure, and excessive alcohol consumption have been suggested as strategies to help prevent epilepsy in older adults.[107]

Complications

[edit]Epilepsy can lead to a range of medical, psychological, and social complications, particularly when seizures are frequent or uncontrolled.[11] One of the most serious risks is injury during a seizure, including falls, burns, or accidents while driving, swimming, or operating machinery.[108][109] The risk of drowning is significantly increased in people with epilepsy, especially those with poor seizure control.[110]

People with epilepsy are at greater risk for mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and social isolation. These challenges are often compounded by stigma, employment difficulties, and driving restrictions.[111][112] In children, epilepsy — especially when drug-resistant — can interfere with cognitive development and academic performance.[113]

A rare but serious complication is sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), which is most often associated with uncontrolled generalized tonic–clonic seizures, particularly during sleep.[114]

Management

[edit]

The primary goals of epilepsy management are to control seizures, minimize treatment side effects, and optimize quality of life. Management strategies are individualized based on the type of seizures or epilepsy syndrome, the underlying cause when known, the person's age and comorbidities, and their preferences and life circumstances.[100]

Supporting people's self-management of their condition may be useful.[115] In drug-resistant cases different management options may be considered, including special diets, the implantation of a neurostimulator, or neurosurgery.[23]

First aid and acute management of seizures

[edit]During a generalized tonic–clonic seizure, the primary goals are to ensure safety and prevent injury. The following steps should be taken:[116]

- Stay calm and remove any potential hazards from the area. Clear the space of sharp objects, furniture, or anything that might cause injury.

- If the person is standing, gently guide them to the ground to avoid a fall.

- Position the person on their side and into the recovery position, which helps keep the airway clear and reduces the risk of choking. If possible, place something soft (e.g., a jacket or cushion) under their head to prevent injury.

- Do not restrain their movements or attempt to hold them down. Do not put anything in their mouth, as this may cause harm.[44][116]

If the seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes or if multiple seizures occur without full recovery in between, it is important to call for emergency medical assistance immediately, as it is considered a medical emergency known as status epilepticus.[117]

Convulsive status epilepticus requires immediate medical attention to prevent serious complications. In a community setting (such as at home or in the ambulance), first-line treatment includes the administration of benzodiazepines. If the person has an individualized emergency management plan — which may have been developed with healthcare providers and outlines personalized treatment steps (such as the use of buccal midazolam or rectal diazepam) — this plan should be followed immediately.[100] In hospital, intravenous lorazepam is preferred.[100]

If seizures continue after the first dose of benzodiazepine, emergency medical services should be contacted, and further doses can be given. For ongoing seizures, levetiracetam, phenytoin, or sodium valproate may be used as second-line treatments, with levetiracetam preferred for its quicker action and fewer side effects.[100]

Most institutions have a preferred pathway or protocol to be used in a seizure emergency like status epilepticus. These protocols have been found to be effective in reducing time to delivery of treatment.[100]

Medications

[edit]

The primary treatment for epilepsy involves the use of antiseizure medications (ASMs), which aim to control seizures while minimizing side effects. Treatment plans should be individualized, taking into account the seizure type, epilepsy syndrome, patient age, sex, comorbidities, lifestyle factors, and the potential for drug interactions.[100]

First-line treatment for most individuals with epilepsy is monotherapy with a single ASM. For many people with epilepsy, seizure control is achieved with a single medication, but some may require combination therapy if seizures are not well-controlled with monotherapy.[100]

There are a number of medications available including phenytoin, carbamazepine and valproate. Evidence suggests that these drugs are similarly effective for both focal and generalized seizures, although their side-effect profiles vary.[118][119] Controlled release carbamazepine appears to work as well as immediate release carbamazepine, and may have fewer side effects.[120] In the UK, carbamazepine or lamotrigine are recommended as first-line treatments for focal seizures, with levetiracetam and valproate used as second-line treatments due to concerns about cost and side effects. Valproate is the first-line choice for generalized seizures, while lamotrigine is used as second-line. For absence seizures, ethosuximide or valproate are recommended, with valproate also being effective for myoclonic and tonic–clonic seizures.[100][121]

Controlled-release formulations of carbamazepine may be preferred in some cases, as they appear to be equally effective as immediate-release carbamazepine but may have fewer side effects. Once a person's seizures are well-controlled on a specific treatment, it is generally not necessary to routinely check medication blood levels, unless there are concerns about side effects or toxicity.[100]

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the management of epilepsy is often hindered by limited access to medications, diagnostic tools, and specialized care.[14] While phenytoin and carbamazepine are commonly used as first-line treatments due to their availability and low cost, newer drugs like levetiracetam and lamotrigine may not be accessible. Additionally, surgical options and advanced therapies, such as vagus nerve stimulation or resective surgery, are typically inaccessible due to high costs and lack of infrastructure.

The least expensive anticonvulsant is phenobarbital at around US$5 a year.[14] The World Health Organization gives it a first-line recommendation in LMICs and it is commonly used in these countries.[122][123] Access, however, may be difficult as some countries label it as a controlled drug.[14]

Adverse effects from medications are reported in 10% to 90% of people, depending on how and from whom the data is collected.[124] Most adverse effects are dose-related and mild.[124] Some examples include mood changes, sleepiness, or an unsteadiness in gait.[124] Certain medications have side effects that are not related to dose such as rashes, liver toxicity, or suppression of the bone marrow.[124] Up to a quarter of people stop treatment due to adverse effects.[124] Some medications are associated with birth defects when used in pregnancy.[125] Many of the common used medications, such as valproate, phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, and gabapentin have been reported to cause increased risk of birth defects,[126] especially when used during the first trimester.[127] Despite this, treatment is often continued once effective, because the risk of untreated epilepsy is believed to be greater than the risk of the medications.[127] Among the antiepileptic medications, levetiracetam and lamotrigine seem to carry the lowest risk of causing birth defects.[126]

Slowly stopping medications may be reasonable in some people who do not have a seizure for two to four years; however, around a third of people have a recurrence, most often during the first six months.[125][128] Stopping is possible in about 70% of children and 60% of adults.[20] Measuring medication levels is not generally needed in those whose seizures are well controlled.[129]

Surgery

[edit]Epilepsy surgery is an important treatment option for individuals with drug-resistant epilepsy,[15][130] typically defined as the failure of at least two appropriately chosen and tolerated antiseizure medications.[131] Surgery is most effective in cases of focal epilepsy, where seizures originate from a specific area of the brain that can be safely removed.[132][133]

Although epilepsy surgery has demonstrated strong evidence of efficacy — especially in drug-resistant focal epilepsy — it remains underutilized worldwide and is often reserved for individuals whose condition has reached an advanced or chronic stage.[130] Early consideration and referral for surgical evaluation can improve long-term outcomes and quality of life. This evaluation, conducted in specialized epilepsy centers, includes seizure classification, long-term video EEG monitoring, high-resolution MRI with epilepsy-specific protocols, neuropsychological assessment, and sometimes functional imaging or invasive monitoring. Early referral improves the likelihood of successful outcomes and avoids prolonged periods of unnecessary disability.[134]

The primary goal of epilepsy surgery is to achieve seizure freedom,[135] but even when that is not possible, palliative procedures that significantly reduce seizure frequency can lead to meaningful improvements in quality of life and development — particularly in children. Studies suggest that 60-70% of individuals with drug-resistant focal epilepsy experience a substantial reduction in seizures following surgery.[136]

Common procedures include anterior temporal lobe resection, which often involves removal of the hippocampus in cases of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, as well as lesionectomy for tumors or cortical dysplasia, and lobectomy for larger seizure foci.[136] In cases where resection is not possible, procedures such as corpus callosotomy may help reduce the severity and spread of seizures. In addition to traditional resective techniques, minimally invasive approaches such as MRI-guided laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT) have gained traction as safer alternatives in select cases, particularly where reducing cognitive impact and recovery time is a priority.[137] In many cases, antiseizure medications can be tapered following successful surgery, though long-term monitoring remains essential.[133][136] Surgical treatment is not limited to adults. A 2023 systematic review found that early surgery in children under 3 years with drug-resistant epilepsy can result in meaningful seizure reduction or freedom when other treatments have failed.[138]

Although epilepsy surgery has demonstrated efficacy, it is still rarely used around the world, and is typically reserved for cases where the condition has reached an advanced stage.[130]

Neuromodulation

[edit]Neurotherapy or Neuromodulation therapies, including vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), deep brain stimulation (DBS), Neuromodulation through Radiotherapy (e.g. Leksell Gamma Knife) and responsive neurostimulation (RNS), are treatment options for individuals with drug-resistant epilepsy who are not candidates for resective surgery, or for whom previous surgery has not resulted in seizure freedom.[139][140][141] These neurotherapies aim to reduce seizure frequency and severity by delivering controlled electrical stimulation to targeted neural circuits.

Diet

[edit]Dietary therapy, particularly the ketogenic diet (high-fat, low-carbohydrate, adequate-protein), is a non-pharmacological treatment option used primarily in children with drug-resistant epilepsy. Evidence suggests that children on a classical ketogenic diet may be up to three times more likely to achieve seizure freedom and up to six times more likely to experience a ≥50% reduction in seizure frequency compared to those receiving standard care. Modified versions of the diet, such as the modified Atkins diet, are better tolerated but may be less effective.[6][142] In adults, the ketogenic diet has shown limited evidence of achieving seizure freedom, though it may increase the likelihood of seizure reduction. However, further research is necessary.[6]

It is typically supervised by a multidisciplinary team, including neurologists and dietitians, due to its restrictive nature and potential side effects, such as vomiting, constipation and diarrhoea. Regular monitoring of nutritional status, blood parameters, and growth is recommended.[6] It is unclear why this diet works.[143] A gluten-free diet has been proposed in rare cases of epilepsy associated with celiac disease and occipital calcifications, though evidence is limited and based on small case series.[76]

Adjunctive and complementary therapies

[edit]There is moderate-quality evidence supporting the use of psychological interventions — such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), relaxation techniques, and self-management training — alongside standard treatment.[144] These approaches may improve quality of life, emotional wellbeing, and treatment adherence; however, evidences targeting seizure control are uncertain.[145] Avoidance therapy consists of minimizing or eliminating triggers. For example, those who are sensitive to light may have success with using a small television, avoiding video games, or wearing dark glasses.[146] Biofeedback, particularly EEG-based operant conditioning, has shown preliminary benefit in some people with drug-resistant epilepsy.[147] However, these methods are considered adjunctive and are not recommended as standalone treatments.

Cannabidiol (CBD) has shown benefit as an add-on therapy in certain severe childhood epilepsies. A purified form of CBD was approved by the U.S. FDA in 2018 and by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2020 for the treatment of Dravet syndrome, Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis complex.[148][149][150]

Regular physical activity is generally considered safe and may have beneficial effects on seizure frequency, mood, and overall wellbeing.[151] While evidence remains limited, some studies suggest that moderate exercise can reduce seizure burden in certain individuals.[152] Seizure response dogs have been trained to assist individuals during or after seizures by providing physical support or alerting others.[153][154] Although anecdotal reports claim that some dogs can anticipate seizures, there is no conclusive scientific evidence supporting the consistent ability of dogs to predict seizures before they occur.[155]

Various forms of alternative medicine, including acupuncture,[156] routine vitamins,[157] and yoga,[158] have no reliable evidence to support their use in epilepsy. Melatonin, as of 2016[update], is insufficiently supported by evidence.[159] The trials were of poor methodological quality and it was not possible to draw any definitive conclusions.[159]

Contraception and pregnancy

[edit]Women of child-bearing age, including those with epilepsy, are at risk of unintended pregnancies if they are not using an effective form of contraception.[160] Women with epilepsy may experience a temporary increase in seizure frequency when they begin hormonal contraception.[160]

Some anti-seizure medications interact with enzymes in the liver and cause the drugs in hormonal contraception to be broken down more quickly. These enzyme inducing drugs make hormonal contraception less effective, and this is particularly hazardous if the anti-seizure medication is associated with birth defects.[161] Potent enzyme-inducing anti-seizure medications include carbamazepine, eslicarbazepine acetate, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, and rufinamide. The drugs perampanel and topiramate can be enzyme-inducing at higher doses.[162] Conversely, hormonal contraception can lower the amount of the anti-seizure medication lamotrigine circulating in the body, making it less effective.[160] The failure rate of oral contraceptives, when used correctly, is 1%, but this increases to between 3–6% in women with epilepsy.[161] Overall, intrauterine devices (IUDs) are preferred for women with epilepsy who are not intending to become pregnant.[160]

Women with epilepsy, especially if they have other medical conditions, may have a slightly lower, but still high, chance of becoming pregnant.[160] Women with infertility have about the same chance of success with in vitro fertilisation or other forms of assisted reproductive technology as women without epilepsy.[160] There may be a higher risk of pregnancy loss.[160]

Once pregnant, there are two main concerns related to pregnancy. The first concern is about the risk of seizures during pregnancy, and the second concern is that the anti-seizure medications may result in birth defects.[126] Most women with epilepsy must continue treatment with anti-seizure drugs, and the treatment goal is to balance the need to prevent seizures with the need to prevent drug-induced birth defects.[160][163]

Pregnancy does not seem to change seizure frequency very much.[160] When seizures happen, however, they can cause some pregnancy complications, such as pre-term births or the babies being smaller than usual when they are born.[160]

All pregnancies have a risk of birth defects, e.g., due to smoking during pregnancy.[160] In addition to this typical level of risk, some anti-seizure drugs significantly increase the risk of birth defects and intrauterine growth restriction, as well as developmental, neurocognitive, and behavioral disorders.[163] Most women with epilepsy receive safe and effective treatment and have typical, healthy children.[163] The highest risks are associated with specific anti-seizure drugs, such as valproic acid and carbamazepine, and with higher doses.[126][160] Folic acid supplementation, such as through prenatal vitamins, reduced the risk.[160] Planning pregnancies in advance gives women with epilepsy an opportunity to switch to a lower-risk treatment program and reduced drug doses.[160]

Although anti-seizure drugs can be found in breast milk, women with epilepsy can breastfeed their babies, and the benefits usually outweigh the risks.[160]

Prognosis

[edit]Epilepsy is generally considered a chronic neurological condition, but its long-term course can vary widely depending on factors such as seizure type, underlying cause, and response to treatment. Although epilepsy is not typically "cured," in many cases it may be considered resolved. According to the ILAE, epilepsy is considered to be resolved in individuals who have been seizure-free for at least 10 years, with no antiseizure medications for the last 5 of those years.[10]

Approximately 60–70% of individuals with epilepsy achieve good seizure control with appropriate antiseizure medications, and many can maintain long-term remission.[7] However, outcomes vary significantly by epilepsy type and etiology. Early treatment response is one of the strongest predictors of long-term outcome, with poor early control correlating with lower chances of remission. Several factors — such as structural brain abnormalities, comorbid developmental disorders, or a high frequency of seizures at onset — have been associated with worse outcomes, although findings are not always consistent.[164]

Epilepsy disproportionately affects low- and middle-income countries, where nearly 80% of the global epilepsy population resides.[165] In these countries, to 75% of individuals with epilepsy do not receive the treatment they need.[11] Untreated epilepsy is associated with elevated risk of injury, psychiatric comorbidities, and early death, including sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).

Cognition

[edit]Cognitive impairment frequently accompanies epilepsy, although it is difficult to determine to what extant it is caused by the epilepsy itself.[166][167] This is because observed cognitive decline could be a result of the cause of the epilepsy (e.g. epilepsy caused by mesial temporal sclerosis), or be secondary to the epilepsy (e.g. brain damage from falling due to a seizure, or impairment from pharmacological or surgical treatment of the epilepsy).[166][167]

In the majority of people who achieve seizure control, there is no associated progressive cognitive decline.[166] However, severe intractable epilepsy does cause negative cognitive effects.[166] Due to its variability, it is unclear whether any given case of epilepsy will lead to cognitive decline, but a few points are noted:

- Epilepsy is associated with increased risk for Alzheimer's disease (and vice-versa).[166][167]

- Longer seizures cause more damage than shorter seizures.[166]

- Progressive thinning of the cerebral cortex occurs with recurring seizures.[166]

Mortality

[edit]People with epilepsy may have a higher risk of premature death compared to those without the condition.[168] This risk is estimated to be between 1.6 and 4.1 times greater than that of the general population.[169] The greatest increase in mortality from epilepsy is among the elderly.[169] Those with epilepsy due to an unknown cause have a relatively low increase in risk.[169]

Mortality is often related to the underlying cause of the seizures, status epilepticus, suicide, trauma, and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).[168] Death from status epilepticus is primarily due to an underlying problem rather than missing doses of medications.[168] The risk of suicide is between two and six times higher in those with epilepsy;[170][171] the cause of this is unclear.[170] SUDEP appears to be partly related to the frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures[172] and accounts for about 15% of epilepsy-related deaths;[173] it is unclear how to decrease its risk.[172] Risk factors for SUDEP include nocturnal generalized tonic-clonic seizures, seizures, sleeping alone and medically intractable epilepsy.[174]

In the United Kingdom, it is estimated that 40–60% of deaths are possibly preventable.[48] In the developing world, many deaths are due to untreated epilepsy leading to falls or status epilepticus.[14]

Epidemiology

[edit]Epilepsy is one of the most common serious neurological disorders, affecting approximately 50 million people globally as of 2021,[8][175] with the majority living in low- and middle-income countries.[11][176] The point prevalence of active epilepsy is generally reported between 5 and 7 per 1,000 people, while lifetime prevalence is slightly higher, typically between 6 and 9 per 1,000.[177] Both prevalence and incidence are higher in low-income regions. The annual incidence of epilepsy — the rate of new diagnoses each year — is estimated at 50 to 70 new cases per 100,000 people globally, based on population studies.[177] Rates are significantly higher in low- and middle-income countries, and, within high-income countries, higher incidence has also been observed among lower socioeconomic groups and some ethnic minorities.

Epilepsy can develop at any age, but its incidence is highest in early infancy and in older adults, following a bimodal distribution. In high-income countries, the incidence peaks during the first year of life, declines during adulthood, and rises again in people over age 85. The increase in older adults is associated with age-related conditions such as stroke, brain tumors, and neurodegenerative diseases. In low- and middle-income countries, incidence more often peaks in older children and young adults, which may reflect the effects of trauma, infections, and underdiagnosis in the elderly. Epilepsy is slightly more common in males than females, a difference that may be influenced by risk factor exposure and underreporting in women in some regions due to sociocultural factors.[178]

Beyond prevalence and incidence, epilepsy imposes a significant global burden in terms of disability, stigma, and premature mortality. The disorder is responsible for an estimated 13 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide each year, with the majority of this burden falling on individuals in low-resource settings where access to diagnosis and treatment remains limited.[175]

History

[edit]

The oldest medical records show that epilepsy has been affecting people at least since the beginning of recorded history.[179] Throughout ancient history, the condition was thought to be of a spiritual cause.[179] The world's oldest description of an epileptic seizure comes from a text in Akkadian (a language used in ancient Mesopotamia) and was written around 2000 BC.[22] The person described in the text was diagnosed as being under the influence of a moon god, and underwent an exorcism.[22] Epileptic seizures are listed in the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1790 BC) as reason for which a purchased slave may be returned for a refund,[22] and the Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1700 BC) describes cases of individuals with epileptic convulsions.[22]

The oldest known detailed record of the condition itself is in the Sakikku, a Babylonian cuneiform medical text from 1067–1046 BC.[179] This text gives signs and symptoms, details treatment and likely outcomes,[22] and describes many features of the different seizure types.[179] As the Babylonians had no biomedical understanding of the nature of epilepsy, they attributed the seizures to possession by evil spirits and called for treating the condition through spiritual means.[179] Around 900 BC, Punarvasu Atreya described epilepsy as loss of consciousness;[180] this definition was carried forward into the Ayurvedic text of Charaka Samhita (c. 400 BC).[181]

The ancient Greeks had contradictory views of the condition. They thought of epilepsy as a form of spiritual possession, but also associated the condition with genius and the divine. One of the names they gave to it was the sacred disease (Ancient Greek: ἠ ἱερὰ νόσος).[22][182] Epilepsy appears in Greek mythology: it is associated with the Moon goddesses Selene and Artemis, who afflicted those who upset them. The Greeks thought that important figures such as Julius Caesar and Hercules had the condition.[22] The notable exception to this divine and spiritual view was that of the school of Hippocrates. In the fifth century BC, Hippocrates rejected the idea that the condition was caused by spirits. In his landmark work On the Sacred Disease, he proposed that epilepsy was not divine in origin and instead was a medically treatable problem originating in the brain.[22][179] He accused those of attributing a sacred cause to the condition of spreading ignorance through a belief in superstitious magic.[22] Hippocrates proposed that heredity was important as a cause, described worse outcomes if the condition presents at an early age, and made note of the physical characteristics as well as the social shame associated with it.[22] Instead of referring to it as the sacred disease, he used the term great disease, giving rise to the modern term grand mal, used for tonic–clonic seizures.[22] Despite his work detailing the physical origins of the condition, his view was not accepted at the time.[179] Evil spirits continued to be blamed until at least the 17th century.[179]

In Ancient Rome people did not eat or drink with the same pottery as that used by someone who was affected.[183] People of the time would spit on their chest believing that this would keep the problem from affecting them.[183] According to Apuleius and other ancient physicians, to detect epilepsy, it was common to light a piece of gagates, whose smoke would trigger the seizure.[184] Occasionally a spinning potter's wheel was used, perhaps a reference to photosensitive epilepsy.[185]

In most cultures, persons with epilepsy have been stigmatized, shunned, or even imprisoned. As late as in the second half of the 20th century, in Tanzania and other parts of Africa epilepsy was associated with possession by evil spirits, witchcraft, or poisoning and was believed by many to be contagious.[186] In the Salpêtrière, the birthplace of modern neurology, Jean-Martin Charcot found people with epilepsy side by side with the mentally ill, those with chronic syphilis, and the criminally insane.[187] In Ancient Rome, epilepsy was known as the morbus comitialis or 'disease of the assembly hall' and was seen as a curse from the gods. In northern Italy, epilepsy was traditionally known as Saint Valentine's malady.[188] In at least the 1840s in the United States of America, epilepsy was known as the falling sickness or the falling fits, and was considered a form of medical insanity.[189] Around the same time period, epilepsy was known in France as the haut-mal lit. 'high evil', mal-de terre lit. 'earthen sickness', mal de Saint Jean lit. 'Saint John's sickness', mal des enfans lit. 'child sickness', and mal-caduc lit. 'falling sickness'.[189] People of epilepsy in France were also known as tombeurs lit. 'people who fall', due to the seizures and loss of consciousness in an epileptic episode.[189]

In the mid-19th century, the first effective anti-seizure medication, bromide, was introduced.[124] The first modern treatment, phenobarbital, was developed in 1912, with phenytoin coming into use in 1938.[190]

Society and culture

[edit]Epilepsy has significant social and cultural implications that vary across regions and contexts. People with epilepsy may experience social stigma, legal restrictions, economic disadvantage, and barriers to education and employment. Public perceptions of the condition are shaped by cultural beliefs, media portrayals, and the level of awareness in a given society. Efforts by advocacy groups and international organizations aim to improve public understanding, reduce stigma, and promote access to care. Social consequences, such as educational exclusion, unemployment, and social isolation, further compound the impact on quality of life. Despite the availability of effective antiseizure medications and cost-effective treatment strategies, a large treatment gap persists in many countries, underscoring the need for strengthened health systems and public health interventions.

Stigma

[edit]Social stigma is commonly experienced by people with epilepsy worldwide, and it can have economic, social, and cultural consequences.[11][191] Misconceptions about the condition — including beliefs that it is contagious, a form of madness, or caused by supernatural forces — persist in many communities. In parts of Africa, including Tanzania and Uganda, epilepsy is sometimes associated with spirit possession, witchcraft, or poisoning, and is incorrectly believed to be contagious.[186][192] Similar stigmatizing beliefs have been reported in other regions, such as India and China, where epilepsy may be cited as grounds for denying marriage.[20] In the United Kingdom, epilepsy was legally considered valid grounds for annulling a marriage until 1971.[63]

Stigma can also affect how people respond to a diagnosis. Some individuals with epilepsy may deny having had seizures, fearing discrimination.[63] A 2024 cross-sectional study found that 64.8% of relatives of people with epilepsy reported experiencing moderate levels of stigma, which was associated with more negative attitudes toward the condition. Greater stigma was observed among relatives of patients with more frequent seizures or poor medication adherence.[193]

Negative perceptions of epilepsy can also affect educational opportunities and academic outcomes.[194] Children with epilepsy are at increased risk of underachievement in school due to a combination of neurological factors, medication side effects, and the effects of social exclusion.[195]

In adulthood, stigma can result in reduced employment opportunities and workplace discrimination. Adults with epilepsy are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed than the general population, a disparity often driven by employer concerns about safety, productivity, or liability.[194] Disclosure of an epilepsy diagnosis in job applications or interviews may lead to discrimination, although nondisclosure can limit access to workplace accommodations.[196]

Economic impact

[edit]Epilepsy is associated with a substantial economic burden at both the individual and societal levels. Direct costs include expenses related to diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management, such as antiseizure medications and hospitalizations. Indirect costs may arise from lost productivity, unemployment, and premature death. In many countries, especially those with limited health infrastructure, individuals with epilepsy and their families often bear the majority of healthcare expenses out of pocket. A 2021 modeling study estimated the total global cost of epilepsy at approximately $119.27 billion annually, based on per capita cost projections applied to an estimated 52.51 million people living with epilepsy worldwide, while accounting for the treatment gap.[197] The treatment gap — referring to the proportion of people with epilepsy who do not receive appropriate care — remains high in low- and middle-income countries, exacerbating the economic burden through avoidable seizures, injuries, and emergency care. Seizures result in direct economic costs of about one billion dollars in the United States.[17] Epilepsy resulted in economic costs in Europe of around 15.5 billion euros in 2004.[48] In India, epilepsy is estimated to result in costs of US$1.7 billion or 0.5% of the GDP.[20] It is the cause of about 1% of emergency department visits (2% for emergency departments for children) in the United States.[198]

Driving and legal restrictions

[edit]Those with epilepsy are at about twice the risk of being involved in a motor vehicular collision and thus in many areas of the world are not allowed to drive or able to drive only if certain conditions are met.[21] Diagnostic delay has been suggested to be a cause of some potentially avoidable motor vehicle collisions since at least one study showed that most motor vehicle accidents occurred in those with undiagnosed non-motor seizures as opposed to those with motor seizures at epilepsy onset.[199] In some places physicians are required by law to report if a person has had a seizure to the licensing body while in others the requirement is only that they encourage the person in question to report it themselves.[21] Countries that require physician reporting include Sweden, Austria, Denmark and Spain.[21] Countries that require the individual to report include the UK and New Zealand, and physicians may report if they believe the individual has not already.[21] In Canada, the United States and Australia the requirements around reporting vary by province or state.[21] If seizures are well controlled most feel allowing driving is reasonable.[200] The amount of time a person must be free from seizures before they can drive varies by country.[200] Many countries require one to three years without seizures.[200] In the United States the time needed without a seizure is determined by each state and is between three months and one year.[200]

Those with epilepsy or seizures are typically denied a pilot license.[201]

- In Canada if an individual has had no more than one seizure, they may be considered after five years for a limited license if all other testing is normal.[202] Those with febrile seizures and drug related seizures may also be considered.[202]

- In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration does not allow those with epilepsy to get a commercial pilot license.[203] Rarely, exceptions can be made for persons who have had an isolated seizure or febrile seizures and have remained free of seizures into adulthood without medication.[204]

- In the United Kingdom, a full National Private Pilot Licence requires the same standards as a professional driver's license.[205] This requires a period of ten years without seizures while off medications.[206] Those who do not meet this requirement may acquire a restricted license if free from seizures for five years.[205]

Advocacy and support organizations

[edit]There are organizations that provide support for people and families affected by epilepsy. In 1997 the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE), the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the World Health Organization launched the Global Campaign Against Epilepsy (GCAE) to bring epilepsy 'out of the shadows' by raising awareness of, and improving treatment and services for epilepsy.[1][207] In the United States, the Epilepsy Foundation is a national organization that works to increase the acceptance of those with the disorder, their ability to function in society and to promote research for a cure.[208] The Epilepsy Foundation, some hospitals, and some individuals also run support groups in the United States.[209] In Australia, the Epilepsy Foundation provides support, delivers education and training and funds research for people living with epilepsy.

International Epilepsy Day (World Epilepsy Day) began in 2015 and occurs on the second Monday in February.[210][211]

Purple Day, a different world-wide epilepsy awareness day for epilepsy, was initiated by a nine-year-old Canadian named Cassidy Megan in 2008, and is every year on 26 March.[212]

Research directions

[edit]Epilepsy research aims to uncover the causes of seizures, improve diagnosis, and develop more effective treatments. It spans genetics, neuroscience, pharmacology, and biomedical engineering, with the shared goal of reducing the burden of disease. Researchers also study how epilepsy develops (epileptogenesis), seeking ways to prevent it entirely.

Animal models

[edit]Animal models are widely used in epilepsy research, providing insight into seizure mechanisms, disease progression, and treatment effects. Rodents are most commonly used, with models based on chemical induction (e.g. kainic acid, pilocarpine), electrical stimulation (e.g. kindling), genetic mutations, and others.[213] Other species, including zebrafish, dogs, and non-human primates, are also employed to capture features not easily replicated in rodents, such as complex behaviors or chronic seizure patterns. These models help researchers study epileptogenesis, test antiseizure drugs, and explore surgical or neuromodulatory interventions. While no model captures the full complexity of human epilepsy, they remain essential for translational research.[214]

Genetics and molecular research

[edit]Advances in genetics have transformed the understanding of epilepsy, particularly in early-onset and treatment-resistant forms. Mutations in genes affecting ion channels, synaptic transmission, and mTOR signaling pathways have been linked to a growing number of epilepsy syndromes, including Dravet syndrome (SCN1A), PCDH19-related epilepsy, and familial focal epilepsies. High-throughput sequencing has enabled the discovery of de novo mutations in severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. In parallel, research into polygenic risk and epigenetic mechanisms is expanding the view of common epilepsies as complex traits. Molecular studies also support the development of targeted therapies, such as precision treatments for specific genetic subtypes.[215] Variations within the sodium channel SCN3A, and Na+/K+,ATPase (ATP1A3), has been implicated some of earliest onset epilepsies with cortical malformations.[216][217]

Epileptogenesis and biomarkers

[edit]Understanding how epilepsy develops (epileptogenesis) is a major focus of current research. This includes identifying biomarkers that predict who is at risk of developing epilepsy. EEG patterns, neuroimaging features, and molecular signals in blood or cerebrospinal fluid are being investigated as early indicators. The goal is to detect epilepsy before chronic seizures begin and to develop interventions that prevent or halt this process. While no validated biomarker is yet in clinical use, this area holds promise for future disease-modifying therapies.[218]

Antiseizure drug development

[edit]The development of new antiseizure medications remains a priority, especially for people with drug-resistant epilepsy. Current research focuses on compounds with novel mechanisms of action, better safety profiles, and disease-modifying potential. High-throughput screening, including zebrafish and organoid models, accelerates early-stage discovery, while pharmacogenomic studies aim to personalize drug selection. Cannabinoids and neurosteroids are also under investigation for specific syndromes and seizure types.[219][220]

Seizure prediction

[edit]The unpredictability of seizures is a major concern for many people with epilepsy, and seizure prediction has been a longstanding focus of research. Early efforts were limited by small datasets and inconsistent results; however, advances in computational modeling, long-term EEG recording, and machine learning have led to renewed interest in the field. Public EEG databases and algorithm competitions have helped standardize evaluation and fostered the development of more accurate methods. In one clinical trial, prospective seizure prediction using intracranial EEG was achieved in a small group of participants. Current approaches often integrate network models of brain activity, multimodal data sources, and closed-loop systems capable of both detecting and responding to pre-ictal changes. These developments have laid the groundwork for future large-scale clinical trials and the potential integration of seizure forecasting into clinical practice.[221]

Mechanistic modeling and alternative pathways

[edit]Mathematical and computational models are increasingly used to simulate the neural dynamics underlying seizures. Reductionist models such as the Epileptor use ordinary differential equations to replicate interictal and ictal discharges observed in experimental data.[222] More detailed versions, including the Epileptor-2, incorporate physiological variables such as ion concentrations and synaptic resource availability.[223] These models suggest that fluctuations in extracellular potassium and intracellular sodium levels may play a key role in the emergence and termination of seizures.[224]

Potential future therapies

[edit]Several novel therapeutic strategies are under investigation for epilepsy. Gene therapy is being studied in some types of epilepsy.[225] Medications that alter immune function, such as intravenous immunoglobulins, may reduce the frequency of seizures when including in normal care as an add-on therapy; however, further research is required to determine whether these medications are very well tolerated in children and in adults with epilepsy.[226] Noninvasive stereotactic radiosurgery is, as of 2012[update], being compared to standard surgery for certain types of epilepsy.[227]

Other animals

[edit]Epilepsy has also been documented in several animal species, particularly dogs and cats.[228] Veterinary treatments often use similar antiepileptic drugs, such as phenobarbital or levetiracetam. In horses, diagnosis can be challenging, especially in focal seizures,[229] and such conditions as juvenile idiopathic epilepsy have been reported in foals.[230]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Epilepsy Fact sheet". WHO. February 2024. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ a b c Hammer GD, McPhee SJ, eds. (2010). "7". Pathophysiology of disease: an introduction to clinical medicine (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-162167-0.

- ^ a b Goldberg EM, Coulter DA (May 2013). "Mechanisms of epileptogenesis: a convergence on neural circuit dysfunction". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 14 (5): 337–349. doi:10.1038/nrn3482. PMC 3982383. PMID 23595016.

- ^ a b c Longo DL (2012). "369 Seizures and Epilepsy". Harrison's principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 3258. ISBN 978-0-07-174887-2.

- ^ a b Bergey GK (June 2013). "Neurostimulation in the treatment of epilepsy". Experimental Neurology. 244: 87–95. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.04.004. PMID 23583414.

- ^ a b c d e Martin-McGill KJ, Bresnahan R, Levy RG, Cooper PN (June 2020). "Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6) CD001903. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001903.pub5. PMC 7387249. PMID 32588435.

- ^ a b c d Eadie MJ (December 2012). "Shortcomings in the current treatment of epilepsy". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 12 (12): 1419–1427. doi:10.1586/ern.12.129. PMID 23237349.

- ^ a b "GBD 2021 Cause and Risk Summary: EPILEPSY". Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Seattle, USA: University of Washington. 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ a b Sinmetz JD, Seeher KM, Schiess N, Nichols E, Cao B, Servili C, et al. (1 April 2024). "Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021". The Lancet Neurology. 23 (4). Elsevier: 344–381. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00038-3. hdl:1959.4/102176. PMC 10949203. PMID 38493795.

- ^ a b c d e f Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, et al. (April 2014). "ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy". Epilepsia. 55 (4): 475–482. doi:10.1111/epi.12550. PMID 24730690.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Epilepsy". World Health Organization. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, et al. (April 2005). "Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE)". Epilepsia. 46 (4): 470–472. doi:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x. PMID 15816939.

- ^ a b Pandolfo M (November 2011). "Genetics of epilepsy". Seminars in Neurology. 31 (5): 506–518. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1299789. PMID 22266888.

- ^ a b c d e f g Newton CR, Garcia HH (September 2012). "Epilepsy in poor regions of the world". Lancet. 380 (9848): 1193–1201. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61381-6. PMID 23021288.

- ^ a b Brodie MJ, Elder AT, Kwan P (November 2009). "Epilepsy in later life". The Lancet. Neurology. 8 (11): 1019–1030. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70240-6. PMID 19800848.

- ^ Holmes TR, Browne GL (2008). Handbook of epilepsy (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7817-7397-3.

- ^ a b c Wilden JA, Cohen-Gadol AA (August 2012). "Evaluation of first nonfebrile seizures". American Family Physician. 86 (4): 334–340. PMID 22963022.

- ^ Neligan A, Adan G, Nevitt SJ, Pullen A, Sander JW, Bonnett L, et al. (Cochrane Epilepsy Group) (January 2023). "Prognosis of adults and children following a first unprovoked seizure". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD013847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013847.pub2. PMC 9869434. PMID 36688481.

- ^ Epilepsy: what are the chances of having a second seizure? (Report). 16 August 2023. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_59456.