Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1

View on WikipediaFibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR-1), also known as basic fibroblast growth factor receptor 1, fms-related tyrosine kinase-2 / Pfeiffer syndrome, and CD331, is a receptor tyrosine kinase whose ligands are specific members of the fibroblast growth factor family. FGFR-1 has been shown to be associated with Pfeiffer syndrome,[5] and clonal eosinophilias.[6]

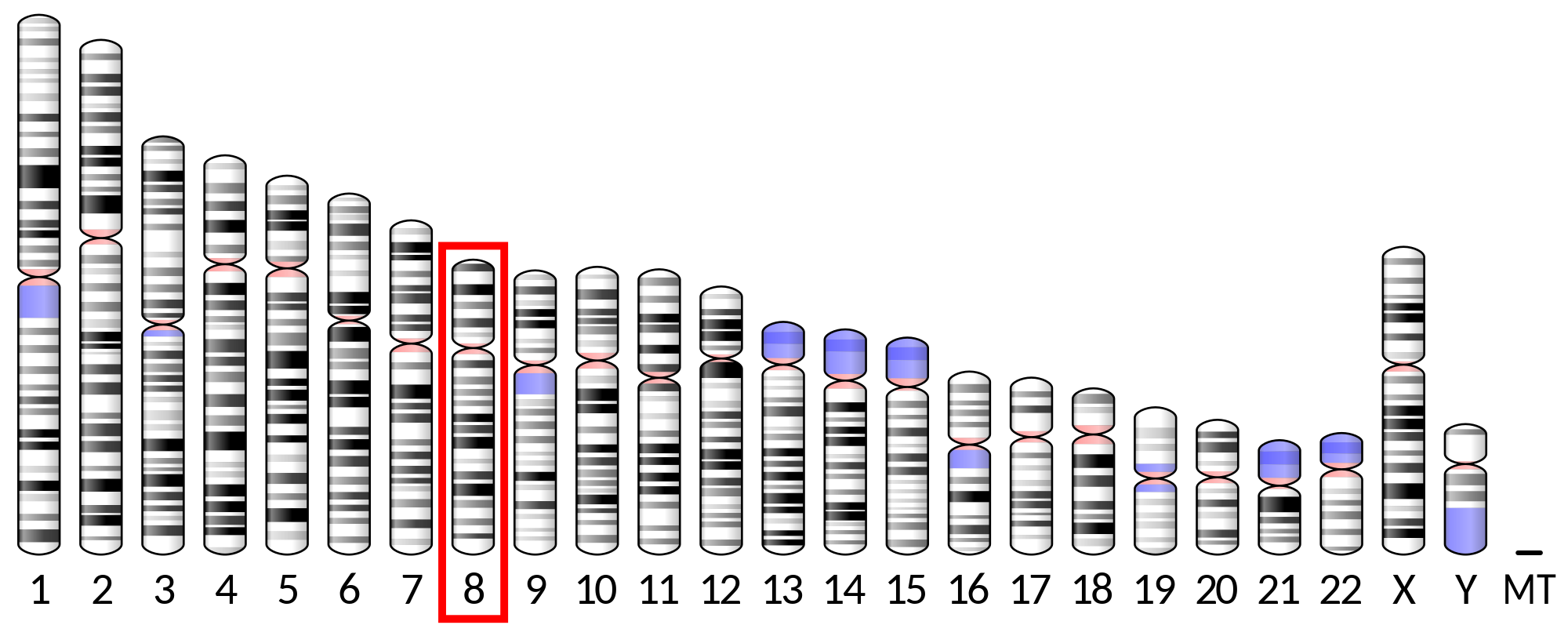

Gene

[edit]The FGFR1 gene is located on human chromosome 8 at position p11.23 (i.e. 8p11.23), has 24 exons, and codes for a Precursor mRNA that is alternatively spliced at exons 8A or 8B thereby generating two mRNAs coding for two FGFR1 isoforms, FGFR1-IIIb (also termed FGFR1b) and FGFR1-IIIc (also termed FGFR1c), respectively. Although these two isoforms have different tissue distributions and FGF-binding affinities, FGFR1-IIIc appears responsible for most of functions of the FGFR1 gene while FGFR1-IIIb appears to have only a minor, somewhat redundant functional role.[7][8] There are four other members of the FGFR1 gene family: FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, and Fibroblast growth factor receptor-like 1 (FGFRL1). The FGFR1 gene, similar to the FGFR2-4 genes are commonly activated in human cancers as a result of their duplication, fusion with other genes, and point mutation; they are therefore classified as proto-oncogenes.[9]

Protein

[edit]Receptor

[edit]FGFR1 is a member of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) family, which in addition to FGFR1, includes FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, and FGFRL1. FGFR1-4 are cell surface membrane receptors that possess tyrosine kinase activity. A full-length representative of these four receptors consists of an extracellular region composed of three immunoglobulin-like domains which bind their proper ligands, the fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), a single hydrophobic stretch which passes through the cell's surface membrane, and a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain. When bonded to FGFs, these receptors form dimers with any one of the four other FGFRs and then cross-phosphorylate key tyrosine residues on their dimer partners. These newly phosphorylated sites bind cytosolic docking proteins such as FRS2, PRKCG and GRB2 which proceed to activate cell signaling pathways that lead to cellular differentiation, growth, proliferation, prolonged survival, migration, and other functions. FGFRL1 lacks a prominent intracellular domain and tyrosine kinase activity; it may serve as a decoy receptor by binding with and thereby diluting the action of FGFs.[9][10] There are 18 known FGFs that bind to and activate one or more of the FGFRs: FGF1 to FGF10 and FGF16 to FGF23. Fourteen of these, FGF1 to FGF6, FGF8, FGF10, FGF17, and FGF19 to FGF23 bind and activate FGFR1.[11] FGFs binding to FGFR1 is promoted by their interaction with cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans and, with respect to FGF19, FGF20, and FGR23, the transmembrane protein Klotho.[11]

Cell activation

[edit]FGFR1, when bound to a proper FGF, elicits cellular responses by activating signaling pathways that include the: a) Phospholipase C/PI3K/AKT, b) Ras subfamily/ERK, c) Protein kinase C, d) IP3-induced raising of cytosolic Ca2+, and e) Ca2+/calmodulin-activated elements and pathways. The exact pathways and elements activated depend on the cell type being stimulated plus other factors such as the stimulated cells microenvironment and previous as well as concurrent history of stimulation[9][10]

Activation of the gamma isoforms of phospholipase C (PLCγ) (see PLCG1 and PLCG2 illustrates one mechanism by which FGFR1 activates cell stimulating pathways. Following its binding of a proper FGF and subsequent pairing with another FGFR, FGFR1 becomes phosphorylated by its partner FGFR on a highly conserved tyrosine residue (Y766) at its C-terminal. This creates a binding or "docking" site to recruit PLCγ via PLCγ tandem nSH2 and cSH2 domains and then phosphorylate PLCγ. By being phosphorylated PLCγ is relieved of its auto-inhibition structure and becomes active in metabolizing nearby Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to two secondary messengers, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacyglycerol (DAG). These secondary messengers proceed to mobilize other cell-signaling and cell-activating agents: IP3 elevates cytosolic Ca2+ and thereby various Ca2+-sensitive elements while DAG activates various protein kinase C isoforms.[11]

Recent publication on the 2.5 Å crystal structure of PLCγ in complex with FGFR1 kinase (PDB: 3GQI) provides new insights in understanding the molecular mechanism of FGFR1's recruitment of PLCγ by its SH2 domains. Figure 1 on the extreme right shows the PLCγ-FGFR1 kinase complex with the c-SH2 domain colored in red, n-SH2 domain colored in blue, and the interdomain linker colored in yellow. The structure contains typical SH2 domain, with two α-helices and three antiparallel β-strands in each SH2 domain. In this complex, the phosphorylated tyrosine (pY766) on the C-terminal tail of FGFR1 kinase binds preferentially to the nSH2 domain of PLCγ. The phosphorylation of tyrosine residue 766 on FGFR1 kinase forms hydrogen bonds with the n-SH2 to stabilize the complex. Hydrogen bonds in the binding pocket help to stabilize the PLCγ-FGFR1 kinase complex. The water molecule as shown mediates the interaction of asparagine 647 (N647) and aspartate 768 (D768) to further increase the binding affinity of the n-SH2 and FGFR1 kinase complex. (Figure 2). The phosphorylation of tyrosine 653 and tyrosine 654 in the active kinase conformation causes a large conformation change in the activation segment of FGFR1 kinase. Threonine 658 is moved by 24Å from the inactive form (Figure 3.) to the activated form of FGFR1 kinase (Figure 4.). The movement causes the closed conformation in the inactive form to open to enable substrate binding. It also allows the open conformation to coordinate Mg2+ with AMP-PCP (analog of ATP). In addition, pY653 and pY654 in the active form helps to maintain the open conformation of the SH2 and FGFR1 kinase complex. However, the mechanism by which the phosphorylation at Y653 and Y654 helps to recruit the SH2 domain to its C-terminal tail upon phosphorylation of Y766 remains elusive. Figure 5 shows the overlay structure of active and inactive forms of FGFR1 kinase. Figure 6 shows the dots and contacts on phosphorylated tyrosine residues 653 and 654. Green dots show highly favorable contacts between pY653 and pY654 with surrounding residues. Red spikes show unfavorable contacts in the activation segment. The figure is generated through Molprobity extension on Pymol.

The tyrosine kinase region of FGFR1 binds to the N-SH2 domain of PLCγ primarily through charged amino acids. Arginine residue (R609) on the N-SH2 domain forms a salt bridge to aspartate 755 (D755) on the FGFR1 domain. The acid base pairs located in the middle of the interface are nearly parallel to each other, indicating a highly favorable interaction. The N-SH2 domain makes an additional polar contact through water-mediated interaction that takes place between the N-SH2 domain and the FGFR1 kinase region. The arginine residue 609 (R609) on the FGFR1 kinase also forms a salt bridge to the aspartate residue (D594) on the N-SH2 domain. The acid-base pair interacts with each other carry out a reduction–oxidation reaction that stabilizes the complex (Figure 7). Previous studies have done to elucidate the binding affinity of the n-SH2 domain with the FGFR1 kinase complex by mutating these phenylalanine or valine amino acids. The results from isothermal titration calorimetry indicated that the binding affinity of the complex decreased by 3 to 6-fold, without affecting the phosphorylation of the tyrosine residues.[12]

Cell inhibition

[edit]FGF-induced activation of FGFR1 also stimulates the activation of sprouty proteins SPRY1, SPRY2, SPRY3, and/or SPRY4 which in turn interact with GRB2, SOS1, and/or c-Raf to reduce or inhibit further cell stimulation by activated FGFR1 as well as other tyrosine kinase receptors such as the Epidermal growth factor receptor. These interactions serve as negative feedback loops to limit the extent of cellular activation.[11]

Function

[edit]Mice genetically engineered to lack a functional Fgfr1 gene (ortholog of the human FGFR1 gene) die in utero before 10.5 days of gestation. Embryos exhibit extensive deficiencies in the development and organization of mesoderm-derived tissues and the musculoskeletal system. The Fgfr1 gene appears critical for the truncation of embryonic structures and formation of muscle and bone tissues and thereby the normal formation of limbs, skull, outer, middle, and inner ear, neural tube, tail, and lower spine as well as normal hearing.[11][13][14]

Clinical significance

[edit]Congenital diseases

[edit]Hereditary mutations in the FGFR1 gene are associated with various congenital malformations of the musculoskeletal system. Interstitial deletions at human chromosome 8p12-p11, arginine to a stop nonsense mutation at FGFR1 amino acid 622 (annotated as R622X), and numerous other autosomal dominant inactivating mutations in FGFR1 are responsible for ~10% of the cases of Kallmann syndrome. This syndrome is a form of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism associated in a varying percentage of cases with anosmia or hyposmia; cleft palate and other craniofacial defects; and scoliosis and other musculoskeletal malformations. An activating mutation in FGFR1 viz., P232R (proline-to-arginine substitution in the protein's 232nd amino acid), is responsible for the Type 1 or classic form of Pfeiffer syndrome, a disease characterized by craniosynostosis and mid-face deformities. A tyrosine-to-cysteine substitution mutation in the 372nd amino acid of FGFR1 (Y372C) is responsible for some cases of Osteoglophonic dysplasia. This mutation results in craniosynostosis, mandibular prognathism, hypertelorism, brachydactyly, and inter-phalangeal joint fusion. Other inherited defects associated with 'FGFR1 mutations likewise involve musculoskeletal malformations: these include the Jackson–Weiss syndrome (proline to arg substitution at amino acid 252), Antley-Bixler syndrome (isoleucine-to-threonine at amino acid 300 (I300T), and trigonocephaly (mutation the same as the one for the Antley-Bixler syndrome viz., I300T).[10][11][15]

Cancers

[edit]Somatic mutations and epigenetic changes in the expression of the FGFR1 gene occur in and are thought to contribute to various types of lung, breast, hematological, and other types of cancers.

Lung cancers

[edit]Amplification of the FGFR1 gene (four or more copies) is present in 9 to 22% of patients with non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). FGFR1 amplification was highly correlated with a history of tobacco smoking and proved to be the single largest prognostic factor in a cohort of patients suffering this disease. About 1% of patients with other types of lung cancer show amplifications in FGFR1.[9][10][16][17]

Breast cancers

[edit]Amplification of FGFR1 also occurs in ~10% of estrogen receptor positive breast cancers, particularly of the luminal subtype B form of breast cancer. The presence of FGFR1 amplification has been correlated with resistance to hormone blocking therapy and found to be a poor prognostic factor in the disease.[9][10]

Hematological cancers

[edit]In certain rare hematological cancers, the fusion of FGFR1 with various other genes due to Chromosomal translocations or Interstitial deletions create genes that encode chimeric FGFR1 Fusion proteins. These proteins have continuously active FGFR1-derived tyrosine kinase and thereby continuously stimulated the cell growth and proliferation. These mutations occur in the early stages of myeloid and/or lymphoid cell lines and are the cause of or contribute to the development and progression of certain types of hematological malignancies that have increased numbers of circulating blood eosinophils, increased numbers of bone marrow eosinophils, and/or the infiltration of eosinophils into tissues. These neoplasms were initially regarded as eosinophilias, hypereosinophilias, Myeloid leukemias, myeloproliferative neoplasms, myeloid sarcomas, lymphoid leukemias, or non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Based on their association with eosinophils, unique genetic mutations, and known or potential sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, they are now being classified together as clonal eosinophilias.[6] These mutations are described by connecting the chromosome site for the FGFR1 gene, 8p11 (i.e. human chromosome 8's short arm [i.e. p] at position 11) with another gene such as the MYO18A whose site is 17q11 (i.e human chromosome 17's long arm [i.e. q] at position 11) to yield the fusion gene annotated as t(8;17)(p11;q11). These FGFR1 mutations along with the chromosomal location of FGFR1A's partner gene and the annotation of the fused gene are given in the following table.[18][19][20]

| Gene | locus | notation | gene | locus | notation | Gene | locus | notation | gene | locus | notation | gene | locus | notation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYO18A | 17q11 | t(8;17)(p11;q11) | CPSF6 | 12q15 | t(8;12)(p11;q15) | TPR | 1q25 | t(1;8)(q25p11;; | HERV-K | 10q13 | t(8;13)(p11-q13) | FGFR1OP2 | 12p11 | t(8;12)(p11;q12) | ||||

| ZMYM2 | 13q12 | t(8;13)(p11;q12) | CUTL1 | 7q22 | t(7;8)(q22;p11) | SQSTM1 | 5q35 | t(5;8)(q35;p11 | RANBP2 | 2q13 | t(2;8)(q13;p11) | LRRFIP1 | 2q37 | t(8;2)(p11;q37) | ||||

| CNTRL | 9q33 | t(8;9)(p11;q33) | FGFR1OP | 6q27 | t(6;8)(q27;p11) | BCR | 22q11 | t(8;22)(p11;q11 | NUP98 | 11p15 | t(8;11)(p11-p15) | MYST3 | 8p11.21 | multiple[21] | ||||

| CEP110 | 16p12 | t(8;16)(p11;p12) |

These cancers are sometimes termed 8p11 myeloproliferative syndromes based on the chromosomal location of the FGFR1 gene. Translocations involving ZMYM2, CNTRL, and FGFR1OP2 are the most common forms of these 8p11 syndromes. In general, patients with any of these diseases have an average age of 44 and present with fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, fever, lymphadenopathy, and enlarged liver and/or spleen. They typically evidence hematological features of the myeloproliferative syndrome with moderate to greatly elevated levels of blood and bone marrow eosinophils. However, patients bearing: a) ZMYM2-FGFR1 fusion genes often present as T-cell lymphomas with spreading to non-lymphoid tissue; b) FGFR1-BCR fusion genes usually present as chronic myelogenous leukemias; c) CEP110 fusion genes may present as a chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with involvement of tonsil; and d) FGFR1-BCR or FGFR1-MYST3 fusion genes often present with little or no eosinophilia. Diagnosis requires conventional cytogenetics using Fluorescence in situ hybridization#Variations on probes and analysis for FGFR1.[19][21]

Unlike many other myeloid neoplasms with eosinophil such as those caused by Platelet-derived growth factor receptor A or platelet-derived growth factor receptor B fusion genes, the myelodysplasia syndromes caused by FGFR1 fusion genes in general do not respond to tyrosine kinase inhibitors, are aggressive and rapidly progressive, and require treatment with chemotherapy agents followed by bone marrow transplantion in order to improve survival.[19][18] The tyrosine kinase inhibitor Ponatinib has been used as mono-therapy and subsequently used in combination with intensive chemotherapy to treat the myelodysplasia caused by the FGFR1-BCR fusion gene.[19]

Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor

[edit]Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors is characterized by a hypervascular proliferation of apparently non-malignant spindled cells associated with a variable amount of ‘smudgy’ calcified matrix but a small subset of these tumors exhibit malignant histological features and may behave in a clinically malignant fashion. In a series of 15 patients with this disease, 9 were found to have tumors that bore fusions between the FGFR1 gene and the FN1 gene located on human chromosome 2 at position q35.[22] The FGFR1-FN1 fusion gene was again identified in 16 of 39 (41%) patients with phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors.[23] The role of the(2;8)(35;11) FGFR1-FN1 fusion gene in this disease is not known.

Rhabdomyosarcoma

[edit]Elevated expression of FGFR1 protein was detected in 10 of 10 human Rhabdomyosarcoma tumors and 4 of 4 human cell lines derived from rhabdomyocarcoma. The tumor cases included 6 cases of Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, 2 cases of Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, and 2 cases of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma. Rhabdomyosarcoma is a highly malignant form of cancer that develops from immature skeletal muscle cell precursors viz., myoblastss that have failed to fully differentiate. FGFR1 activation causes myoblast to proliferate while inhibiting their differentiation, dual effects that may lead to the assumption of a malignant phenotype by these cells. The 10 human rhabdomyosarcoma tumor exhibited decreased levels of methylation of CpG islands upstream of the first FGFR1 exon. CpG islands commonly function to silence expression of adjacent genes while their methylation inhibits this silencing. Hypomethylation of CpG islands upstream of FGFR1 is hypothesized to be at least in part responsible for the over-expression of FGFR1 by and malignant behavior of these rhabdomyosarcoma tumors.[24] In addition, a single case of rhabdomyosarcoma tumor was found express co-amplified FOXO1 gene at 13q14 and FGFR1 gene at 8p11, i.e. t(8;13)(p11;q14), suggesting the formation, amplification, and malignant activity of a chimerical FOXO1-FGFR1 fusion gene by this tumor.[9][25]

Other types of cancers

[edit]Acquired abnormalities if the FGFR1 gene are found in: ~14% of urinary bladder Transitional cell carcinomas (almost all are amplifications); ~10% of squamous cell Head and neck cancers (~80% amplifications, 20% other mutations); ~7% of endometrial cancers (half amplifications, half other types of mutations); ~6% of prostate cancers (half amplifications, half other mutations); ~5% of ovarian Papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma (almost all amplifications); ~5% of colorectal cancers (~60 amplifications, 40% other mutations); ~4% of sarcomas (mostly amplifications); <3% of Glioblastomas (Fusion of FGFR1 and TACC1 (8p11) gene); <3% of Salivary gland cancer (all amplifications); and <2% in certain other cancers.[11][26][27]

FGFR inhibitors

[edit]FGFR-targeted drugs exert direct as well as indirect anticancer effects, due to the fact that FGFRs on cancer cells and endothelial cells are involved in tumorigenesis and vasculogenesis, respectively.[9] FGFR therapeutics are active as FGF affects numerous features of cancers, such as invasiveness, stemness and cellular survival. Primary among such drugs are antagonists. Small molecules that fit between the ATP binding pockets of the tyrosine kinase domains of the receptors. For FGFR1, numerous such small molecules have been approved for targeting the TKI ATP pocket. These include dovitinib and brivanib. The table below provides the IC50 (nanomolar) of small-molecule compounds targeting FGFRs.[9]

| PD173074 | Dovitinib | Ki23057 | Lenvatinib | Brivanib | Nintedanib | Ponatinib | MK-2461 | Lucitanib | AZD4547 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | 8 | NA | 46 | 148 | 69 | 2.2 | 65 | 18 | 0.2 |

FGFR1 mutation in breast and lung cancer as a result of genetic over-amplification is effectively targeted using dovitinib and ponatinib, respectively.[28] Drug resistance is a highly relevant topic in the field of drug development for FGFR targets. FGFR inhibitors allow for the increase of tumor sensitivity to cytotoxic anticancer drugs such as paclitaxel, and etoposide in human cancer cells, thereby decreasing antiapoptotic potential based on faulty FGFR activation.[9] Since FGF signaling inhibition dramatically reduces revascularization, it interferes with one of the hallmarks of cancers, angiogenesis. It also reduces tumor burden in human tumors that depend on autocrine FGF signaling, based on FGF2 upregulation following the common VEGFR-2 therapy for breast cancer. Thus, FGFR1 can act synergistically with therapies to cut off cancer clonal resurgence by eliminating potential pathways of future relapse. Moreover, FGF signaling inhibition dramatically reduces revascularization.[29][30]

FGFR inhibitors have been predicted to be effective on relapsed tumors because of the clonal evolution of an FGFR-activated minor subpopulation after therapy targeted to EGFRs or VEGFRs. Because there are multiple mechanisms of action for FGFR inhibitors to overcome drug resistance in human cancer, FGFR-targeted therapy might be a promising strategy for the treatment of refractory cancer.[31]

AZD4547 has undergone a phase II clinical trial in gastric cancer and reported some results.[32]

Lucitanib is an inhibitor of FGFR1 and FGFR2 and has undergone clinical trials for advanced solid tumors.[33]

Dovitinib (TKI258), an inhibitor of FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR3, has had a clinical trial on FGFR-amplified breast cancers.[28]

Interactions

[edit]Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 has been shown to interact with:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000077782 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000031565 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Itoh N, Terachi T, Ohta M, Seo MK (June 1990). "The complete amino acid sequence of the shorter form of human basic fibroblast growth factor receptor deduced from its cDNA". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 169 (2): 680–685. Bibcode:1990BBRC..169..680I. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(90)90384-Y. PMID 2162671.

- ^ a b Gotlib J (November 2015). "World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management". American Journal of Hematology. 90 (11): 1077–1089. doi:10.1002/ajh.24196. PMID 26486351. S2CID 42668440.

- ^ "FGFR1 fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI".

- ^ Gonçalves C, Bastos M, Pignatelli D, Borges T, Aragüés JM, Fonseca F, et al. (November 2015). "Novel FGFR1 mutations in Kallmann syndrome and normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: evidence for the involvement of an alternatively spliced isoform". Fertility and Sterility. 104 (5): 1261–7.e1. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.1142. hdl:10400.17/2465. PMID 26277103.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Katoh M, Nakagama H (March 2014). "FGF receptors: cancer biology and therapeutics". Medicinal Research Reviews. 34 (2): 280–300. doi:10.1002/med.21288. PMID 23696246. S2CID 27412585.

- ^ a b c d e Kelleher FC, O'Sullivan H, Smyth E, McDermott R, Viterbo A (October 2013). "Fibroblast growth factor receptors, developmental corruption and malignant disease". Carcinogenesis. 34 (10): 2198–2205. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgt254. PMID 23880303.

- ^ a b c d e f g Helsten T, Schwaederle M, Kurzrock R (September 2015). "Fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling in hereditary and neoplastic disease: biologic and clinical implications". Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 34 (3): 479–496. doi:10.1007/s10555-015-9579-8. PMC 4573649. PMID 26224133.

- ^ Bae JH, Lew ED, Yuzawa S, Tomé F, Lax I, Schlessinger J (August 2009). "The selectivity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling is controlled by a secondary SH2 domain binding site". Cell. 138 (3): 514–524. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.028. PMC 4764080. PMID 19665973.

- ^ Deng C, Bedford M, Li C, Xu X, Yang X, Dunmore J, Leder P (May 1997). "Fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR-1) is essential for normal neural tube and limb development". Developmental Biology. 185 (1): 42–54. doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8553. PMID 9169049.

- ^ Calvert JA, Dedos SG, Hawker K, Fleming M, Lewis MA, Steel KP (June 2011). "A missense mutation in Fgfr1 causes ear and skull defects in hush puppy mice". Mammalian Genome. 22 (5–6): 290–305. doi:10.1007/s00335-011-9324-8. PMC 3099004. PMID 21479780.

- ^ "OMIM Entry - * 136350 - FIBROBLAST GROWTH FACTOR RECEPTOR 1; FGFR1".

- ^ "FGFR1 Alterations". Archived from the original on 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2015-04-21.[full citation needed]

- ^ Kim HR, Kim DJ, Kang DR, Lee JG, Lim SM, Lee CY, et al. (February 2013). "Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 gene amplification is associated with poor survival and cigarette smoking dosage in patients with resected squamous cell lung cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 31 (6): 731–737. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.8622. PMID 23182986.

- ^ a b Vega F, Medeiros LJ, Bueso-Ramos CE, Arboleda P, Miranda RN (September 2015). "Hematolymphoid neoplasms associated with rearrangements of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, and FGFR1". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 144 (3): 377–392. doi:10.1309/AJCPMORR5Z2IKCEM. PMID 26276769. S2CID 10435391.

- ^ a b c d Reiter A, Gotlib J (February 2017). "Myeloid neoplasms with eosinophilia". Blood. 129 (6): 704–714. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-10-695973. PMID 28028030.

- ^ Appiah-Kubi K, Lan T, Wang Y, Qian H, Wu M, Yao X, et al. (January 2017). "Platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs) fusion genes involvement in hematological malignancies". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 109: 20–34. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.11.008. PMID 28010895.

- ^ a b Patnaik MM, Gangat N, Knudson RA, Keefe JG, Hanson CA, Pardanani A, et al. (April 2010). "Chromosome 8p11.2 translocations: prevalence, FISH analysis for FGFR1 and MYST3, and clinicopathologic correlates in a consecutive cohort of 13 cases from a single institution". American Journal of Hematology. 85 (4): 238–242. doi:10.1002/ajh.21631. PMID 20143402. S2CID 5256456.

- ^ Lee JC, Jeng YM, Su SY, Wu CT, Tsai KS, Lee CH, et al. (March 2015). "Identification of a novel FN1-FGFR1 genetic fusion as a frequent event in phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour". The Journal of Pathology. 235 (4): 539–545. doi:10.1002/path.4465. PMID 25319834. S2CID 9887919.

- ^ Lee JC, Su SY, Changou CA, Yang RS, Tsai KS, Collins MT, et al. (November 2016). "Characterization of FN1-FGFR1 and novel FN1-FGF1 fusion genes in a large series of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors". Modern Pathology. 29 (11): 1335–1346. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2016.137. PMID 27443518.

- ^ Goldstein M, Meller I, Orr-Urtreger A (November 2007). "FGFR1 over-expression in primary rhabdomyosarcoma tumors is associated with hypomethylation of a 5' CpG island and abnormal expression of the AKT1, NOG, and BMP4 genes". Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer. 46 (11): 1028–1038. doi:10.1002/gcc.20489. PMID 17696196. S2CID 8865648.

- ^ Liu J, Guzman MA, Pezanowski D, Patel D, Hauptman J, Keisling M, et al. (October 2011). "FOXO1-FGFR1 fusion and amplification in a solid variant of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma". Modern Pathology. 24 (10): 1327–1335. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2011.98. PMID 21666686.

- ^ Singh D, Chan JM, Zoppoli P, Niola F, Sullivan R, Castano A, et al. (September 2012). "Transforming fusions of FGFR and TACC genes in human glioblastoma". Science. 337 (6099): 1231–1235. Bibcode:2012Sci...337.1231S. doi:10.1126/science.1220834. PMC 3677224. PMID 22837387.

- ^ Ach T, Schwarz-Furlan S, Ach S, Agaimy A, Gerken M, Rohrmeier C, et al. (August 2016). "Genomic aberrations of MDM2, MDM4, FGFR1 and FGFR3 are associated with poor outcome in patients with salivary gland cancer". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 45 (7): 500–509. doi:10.1111/jop.12394. PMID 26661925.

- ^ a b André F, Bachelot T, Campone M, Dalenc F, Perez-Garcia JM, Hurvitz SA, et al. (July 2013). "Targeting FGFR with dovitinib (TKI258): preclinical and clinical data in breast cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 19 (13): 3693–3702. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0190. PMID 23658459.

- ^ Repetto M, Crimini E, Giugliano F, Morganti S, Belli C, Curigliano G (October 2021). "Selective FGFR/FGF pathway inhibitors: inhibition strategies, clinical activities, resistance mutations, and future directions". Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 14 (10): 1233–1252. doi:10.1080/17512433.2021.1947246. PMID 34591728. S2CID 238231910.

- ^ Chioni AM, Grose RP (November 2021). "Biological Significance and Targeting of the FGFR Axis in Cancer". Cancers. 13 (22): 5681. doi:10.3390/cancers13225681. PMC 8616401. PMID 34830836.

- ^ Asai N, Ohkuni Y, Kaneko N, Yamaguchi E, Kubo A (March 2014). "Relapsed small cell lung cancer: treatment options and latest developments". Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology. 6 (2): 69–82. doi:10.1177/1758834013517413. PMC 3932054. PMID 24587832.

- ^ "A randomized, open-label phase II study of AZD4547 (AZD) versus Paclitaxel (P) in previously treated patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC) with Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 (FGFR2) polysomy or gene amplification (amp): SHINE study". Archived from the original on 2016-03-24. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- ^ Soria JC, DeBraud F, Bahleda R, Adamo B, Andre F, Dientsmann R, et al. (November 2014). "Phase I/IIa study evaluating the safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of lucitanib in advanced solid tumors". Annals of Oncology. 25 (11): 2244–2251. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu390. PMID 25193991.

- ^ Schlessinger J, Plotnikov AN, Ibrahimi OA, Eliseenkova AV, Yeh BK, Yayon A, et al. (September 2000). "Crystal structure of a ternary FGF-FGFR-heparin complex reveals a dual role for heparin in FGFR binding and dimerization". Molecular Cell. 6 (3): 743–750. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00073-3. PMID 11030354.

- ^ Santos-Ocampo S, Colvin JS, Chellaiah A, Ornitz DM (January 1996). "Expression and biological activity of mouse fibroblast growth factor-9". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (3): 1726–1731. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.3.1726. PMID 8576175.

- ^ Yan KS, Kuti M, Yan S, Mujtaba S, Farooq A, Goldfarb MP, Zhou MM (May 2002). "FRS2 PTB domain conformation regulates interactions with divergent neurotrophic receptors". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (19): 17088–17094. doi:10.1074/jbc.M107963200. PMID 11877385.

- ^ Ong SH, Guy GR, Hadari YR, Laks S, Gotoh N, Schlessinger J, Lax I (February 2000). "FRS2 proteins recruit intracellular signaling pathways by binding to diverse targets on fibroblast growth factor and nerve growth factor receptors". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 20 (3): 979–989. doi:10.1128/mcb.20.3.979-989.2000. PMC 85215. PMID 10629055.

- ^ Xu H, Lee KW, Goldfarb M (July 1998). "Novel recognition motif on fibroblast growth factor receptor mediates direct association and activation of SNT adapter proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (29): 17987–17990. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.29.17987. PMID 9660748.

- ^ Dhalluin C, Yan KS, Plotnikova O, Lee KW, Zeng L, Kuti M, et al. (October 2000). "Structural basis of SNT PTB domain interactions with distinct neurotrophic receptors". Molecular Cell. 6 (4): 921–929. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(05)00087-0. PMC 5155437. PMID 11090629.

- ^ Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, Iijima K, Hasegawa H, Okawa K, et al. (December 2006). "Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23". Nature. 444 (7120): 770–774. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..770U. doi:10.1038/nature05315. PMID 17086194. S2CID 4387190.

- ^ Reilly JF, Mickey G, Maher PA (March 2000). "Association of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 with the adaptor protein Grb14. Characterization of a new receptor binding partner". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (11): 7771–7778. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.11.7771. PMID 10713090.

- ^ Karlsson T, Songyang Z, Landgren E, Lavergne C, Di Fiore PP, Anafi M, et al. (April 1995). "Molecular interactions of the Src homology 2 domain protein Shb with phosphotyrosine residues, tyrosine kinase receptors and Src homology 3 domain proteins". Oncogene. 10 (8): 1475–1483. PMID 7537362.

Further reading

[edit]- Weiss J, Sos ML, Seidel D, Peifer M, Zander T, Heuckmann JM, et al. (December 2010). "Frequent and focal FGFR1 amplification associates with therapeutically tractable FGFR1 dependency in squamous cell lung cancer". Science Translational Medicine. 2 (62): 62ra93. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3001451. PMC 3990281. PMID 21160078.

- Johnson DE, Williams LT (1992). Structural and Functional Diversity in the FGF Receptor Multigene Family. Advances in Cancer Research. Vol. 60. pp. 1–41. doi:10.1016/S0065-230X(08)60821-0. ISBN 978-0-12-006660-5. PMID 8417497.

- Macdonald D, Reiter A, Cross NC (2002). "The 8p11 myeloproliferative syndrome: a distinct clinical entity caused by constitutive activation of FGFR1". Acta Haematologica. 107 (2): 101–107. doi:10.1159/000046639. PMID 11919391. S2CID 9582122.

- Groth C, Lardelli M (2002). "The structure and function of vertebrate fibroblast growth factor receptor 1". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 46 (4): 393–400. PMID 12141425.

- Wilkie AO (April 2005). "Bad bones, absent smell, selfish testes: the pleiotropic consequences of human FGF receptor mutations". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 16 (2): 187–203. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.03.001. PMID 15863034.

External links

[edit]- GeneReviews/NIH/NCBI/UW entry on FGFR-Related Craniosynostosis Syndromes

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Kallmann syndrome

- FGFR1+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 on the Atlas of Genetics and Oncology

- FGFR1 human gene location in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- FGFR1 human gene details in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P11362 (Human Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1) at the PDBe-KB.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P16092 (Mouse Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1) at the PDBe-KB.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.