Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

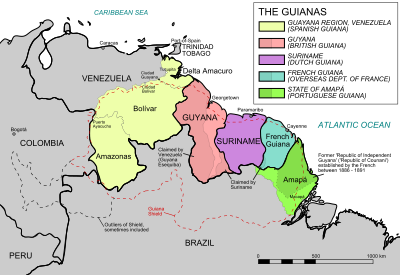

The Guianas

View on Wikipedia

The Guianas, also spelled Guyanas or Guayanas, are a geographical region in north-eastern South America. Strictly, the term refers to the three Guianas: Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, formerly British, Dutch, and French Guiana respectively. Broadly, it refers to the South American coast from the mouth of the Orinoco to the mouth of the Amazon.

Politically it is divided into:

- Spanish or Venezuelan Guiana, now the Delta Amacuro State and Guayana Region of Venezuela.

- Guyana, formerly British Guiana, independent since 1966.

- Suriname, formerly Dutch Guiana, independent since 1975.

- French Guiana, an overseas department and region of France.

- Brazilian or Portuguese Guiana, now the Amapá State of Brazil.

The three Guianas proper have a combined population of 1,718,651; Guyana: 804,567, Suriname: 612,985, and French Guiana: 301,099.[1][2] Most of the population is along the coast. Due to the jungles to the south, the Guianas are one of the most sparsely populated regions on Earth.

Prior to c. 1815 there was a string of mostly Dutch settlements along the coast which changed hands several times. They were mostly several miles upriver to avoid the coastal marshes which were only drained later.

- British Guiana (before 1793 part of Dutch Guyana):

- Pomeroon (colony) (70 miles NW of Georgetown) 165?: Dutch, 1689:abandoned after French destruction, Dutch later return, 1831 to British Guyana.

- Essequibo (colony) (20 miles NW of Georgetown) c 1616 Dutch, 1665 British occupation, (1781 British, 1782 French occupation, 1783 Dutch), 1793 British, 1831 British Guiana

- Demerara (Georgetown) 1745 Dutch from Essequibo, 1781-1831: like Essequibo

- Berbice (114 miles SE of Georgetown) 1627 Dutch, 1781-1831: like Essequebo

- Dutch Guiana

- Nickerie (200 miles SE of Georgetown)(small) 1718 Dutch

- Surinam 1651 English, 1667 Dutch, 1799 English during French wars, 1814 restored to Dutch but England keeps British Guiana

- French Guiana

- Sinnamary: (100 miles NW of Cayenne) 1624 French, captured by Dutch and English several times, 1763: French

- Cayenne 1604,1643 French fail,1615 Dutch fail, 1635 Dutch, 1664 French, 1667 English capture and return, French, 1676? Dutch, 1763? French, 1809 Anglo-Portuguese, 1817 French

To the east and up the lower Amazon, there were a number of English, French and Dutch outposts that either failed or were expelled by the Portuguese. To the west, Spanish Guyana was thinly settled and interacted slightly with Pomeroon.

History

[edit]Pre-colonial period

[edit]Before the arrival of European colonials, the Guianas were populated by scattered bands of native Arawak people. The native tribes of the Northern amazon forests are most closely related to the natives of the Caribbean; most evidence suggests that the Arawaks immigrated from the Orinoco and Essequibo River Basins in Venezuela and Guiana into the northern islands, and were then supplanted by more warlike tribes of Carib Indians, who departed from these same river valleys a few centuries later.[3][4][5]

Over the centuries of the pre-colonial period, the ebb and flow of power between Arawak and Carib interests throughout the Caribbean resulted in a great deal of intermingling (some forced through capture, some accidental through contact). This ethnic mixing, particularly in the Caribbean margins like the Guianas, produced a hybridised culture. Despite their political rivalry, the ethnic and cultural blending between the two groups had reached such a level that, by the time the Europeans arrived, the Carib/Arawak complex in Guiana was so homogeneous that the two groups were almost indistinguishable to outsiders.[4]: 11–13 Through the contact period following Columbus's arrival, the term "Guiana" was used to refer to all areas between the Orinoco, the Rio Negro, and the Amazon, and was seen so much as a unified, isolated entity that it was often referred to as the “Island of Guiana.”[6][7]: 17

European colonisation

[edit]Christopher Columbus first spotted the coast of the Guianas in 1498, but real interest in the exploration and colonisation of the Guianas, which came to be known as the "Wild Coast," did not begin until the end of the sixteenth century. In 1542, when Francisco de Orellana reached the mouth of the Amazon, he was pushed by winds and currents northwest along the Guiana coast until he reached a Spanish settlement west of Trinidad. Walter Raleigh began the exploration of the Guianas in earnest in 1594. He was in search of a great golden city at the headwaters of the Caroní River. A year later he explored what is now Guyana and eastern Venezuela in search of "Manoa", the legendary city of the king known as El Dorado. Raleigh described the city of El Dorado as being located on Lake Parime far up the Orinoco River in Guyana. Much of his exploration is documented in his books The Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Bewtiful Empyre of Guiana, published first in 1596, and The Discovery of Guiana, and the Journal of the Second Voyage Thereto, published in 1606.[8]

After the publication of Raleigh's accounts, several other European powers developed interest in the Guianas. The Dutch joined in the exploration of the Guianas before the end of the century. Between the start of the Dutch Revolt in 1568 and 1648, when the Treaty of Münster was signed with the Spanish, the Dutch cobbled together different ethnicities and tribes and religious faiths into a viable economic entity. When beginning an empire, the Dutch concerned themselves more with trade and establishing viable networks and outposts than with claiming tracts of land to act as a buffer against neighbouring states. With this goal in mind, the Dutch dispatched explorer Jacob Cornelisz to survey the area in 1597. His clerk, Adriaen Cabeliau, related the voyage of Cornelisz and his survey of Indian groups and areas of potential trade partnerships in his diary. Throughout the seventeenth century, the Dutch made gains by establishing trading colonies and outposts in the region and in the neighbouring Caribbean islands under the banner of the Dutch West India Company. The company, established in 1621 for such purposes, benefited from a larger investment of capital than the English, primarily through foreign investors like Isaac de Pinto, a Portuguese Jew. The area was also cursorily explored by Amerigo Vespucci and Vasco Núñez de Balboa, and in 1608 the Grand Duchy of Tuscany also organised an expedition to the Guianas, but this was cut short by the untimely death of the Grand Duke.

English and Dutch settlers were regularly harassed by the Spanish and Portuguese, who viewed settlement of the area as a violation of the Treaty of Tordesillas. In 1613, Dutch trading posts on the Essequibo and Corantijn Rivers were completely destroyed by Spanish troops. The troops had been sent into the Guianas from neighbouring Venezuela under the premise of stamping out privateering and with the support of a cédula passed by the Spanish Council of the Indies and King Philip III.[9] Nonetheless, the Dutch returned in 1615, founding a new settlement at present-day Cayenne (later abandoned in favour of Suriname), one on the Wiapoco River (now more commonly known as the Oyapock) and one on the upper Amazon. By 1621, a charter was granted by the Dutch States-General, but even a few years prior to the official chartering a fort and trading post had been built at Kijkoveral, under the supervision of Aert Groenewegen, at the confluence of the Essequibo, Cuyuni, and Mazaruni Rivers.[10] British settlers also succeeded in establishing a small settlement in 1606 and a much larger one in modern-day Suriname in 1650, under the leadership of former Barbadian governor Francis Willoughby, Lord Parham.[9]: 76

The French had also made less significant attempts at colonisation, first in 1604 along the Sinnamary River. The settlement collapsed within a summer, and initial attempts at settlement near modern-day Cayenne, beginning in 1613, were met with similar setbacks. French priorities—land acquisition and Catholic conversion—were not easily reconciled with the difficulties of initial settlement-building on the Wild Coast. Even as late as 1635, the King of France granted permission to the whole of Guiana to a joint-stock company of Norman merchants. When these merchants made a settlement near the modern city of Cayenne, failure ensued. Eight years later, a reinforcement contingent led by Charles Poncet de Brétigny found only a few of the original colonists left alive, living among the aborigines. Later that year, among the combined total of the original surviving settlers, the reinforcement contingent led by de Brétigny, and a subsequent reinforcement later in the year, only two individuals remained alive long enough to reach the Dutch settlement on the Pomeroon River in 1645, begging for refuge. Though some trading outposts that could be considered permanent settlements were founded as early as 1624, French “possession” of the land now known as French Guiana is not recognised as having taken place until at least 1637. Cayenne itself, the first permanent settlement of comparable size to the Dutch colonies, experienced instability until 1643.[11][12][7]: 36

The Dutch appointed a new governor of the Guiana settlements in 1742. In this year, Laurens Storm van 's Gravesande took over the region. He held the position for three decades, coordinating the development and expansion of the Dutch colonies from his plantation Soesdyke in Demerara.[13] Gravesande’s tenure brought significant change to the colonies, though his policy was in many ways an extension of his predecessor, Hermanus Gelskerke. Commandeur Gelskerke had begun pressing for change from a trading focus to one of cultivation, especially of sugar. The area east of the existing Essequibo colony, known as Demerara, was relatively isolated and encompassed the trading areas of just a few indigenous tribes, thus it contained only two trading outposts during Gelskerke’s term of office. Demerara, though, showed great potential as a sugar-cultivating area, so the commandeur began shifting focus toward the development of the region, signifying his intentions by transferring the administrative center of the colony from Fort Kijkoveral to Flag Island, on the mouth of the Essequibo River, further east and closer to Demerara. These operations were carried out by Gravesande, acting as the Secretary of the Company under Gelskerke. Upon Gelskerke’s death, Gravesande continued the policy of Demerara expansion and the move to sugar cultivation.

Conflict among the British, Dutch, and French continued throughout the seventeenth century. The Treaty of Breda (1667) sealed peace between the English and the Dutch. The treaty allowed the Dutch to retain control over the valuable sugar plantations and factories on the coast of Suriname which had been secured by Abraham Crijnssen earlier in 1667.

All the colonies along the Guiana coast were converted to profitable sugar plantations during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. War continued off and on among the three principal powers in the Guianas (the Netherlands, France, and Britain) until a final peace was signed in 1814 (the Convention of London), heavily favouring the British. By this time France had sold off most of its North American territory in the Louisiana Purchase and had lost all but Guadeloupe, Martinique, and French Guiana in the Caribbean region. The Dutch lost Berbice, Essequibo, and Demerara; these colonies were consolidated under a central British administration and would be known after 1831 as British Guiana. The Dutch retained Suriname.

After 1814, the Guianas came to be recognised individually as British Guiana, French Guiana, and Dutch Guiana.

Demographics

[edit]Due to the isolated geography of the Guianas, the region is one of the most isolated and sparsely populated on Earth. In most of the region, the population is almost entirely concentrated on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean at the mouth of river deltas, in the cities of Georgetown, Paramaribo, Cayenne, and Macapá. However, in Venezuela, major cities are inland: the largest city in the Guianas, Ciudad Guayana in Venezuela, is one that is inland, with a population of almost 1 million people, Ciudad Bolivar with an estimated population of 422,578[14] as well as another major city, Puerto Ayacucho, with a population of 41,000.

Spanish, English, Dutch, French, and Portuguese are spoken in the Guianas: in Guayana, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, and Amapá, respectively. Suriname is the only sovereign nation, other than the Netherlands, where Dutch is the sole official language. Languages spoken locally by specific ethnic groups include Arawakan and Cariban languages, Caribbean Hindustani, Maroon languages, Javanese, Chinese, Hmong, Haitian Creole, and Arabic.

The diverse population and isolation of the region has led to the development of a number of creole and pidgin languages; these include Guyanese Creole in Guyana, Sranan Tongo, Saramaccan, Ndyuka, Matawai, and Kwinti in Suriname, and French Guianese Creole in French Guiana, and Karipúna French Creole in Amapa. These creole languages are based on English in Suriname and Guyana with significant influence from Dutch, Arawak, Cariban, Javanese, Hindustani, West African languages, Chinese, and Portuguese. French Guianese Creole and Karipuna French Creole are based on French with influences from Brazilian Portuguese and Arawak and Cariban languages. Ndyuka is one of the only creole languages that uses its own script, called Afaka syllabary. Pidgin languages spoken in the Guianas include Panare Trade Spanish, a pidgin between the Panare language and Spanish; and Ndyuka-Tiriyó Pidgin, a pidgin spoken in Suriname until the 1960s formed between the creole Ndyuka language and the Amerindian Tiriyó language. Extinct creole languages in the Guianas are Skepi Creole Dutch and Berbice Creole Dutch, both based on Dutch and spoken in Guyana.

The Guianas is also one of the most racially diverse regions on Earth, particularly in Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, due to their long histories of migration to the region brought by slavery and indentured labour. The entire region has a large Amerindian population of the Arawak and Carib language groups. There are a number of uncontacted peoples in the region due to the region's isolation. The two largest ethnic groups in Guyana and Suriname are Indians, who are largely descended from indentured labourers from the Bhojpuri regions of India, with smaller numbers from South India; and Africans, descendants of enslaved West Africans brought to the region during colonial times. Africans are further divided into Creoles, who are located along the coastal regions, and Maroons, who are descendants of people who escaped slavery into the interior regions of the country. Multiracial people, who are largely Dougla people, of African and Indian descent, make up a growing proportion of the population in Guyana and Suriname. Javanese Surinamese are another major group in Suriname, who are descendants of indentured labourers recruited from Dutch colonies in Indonesia, and both Guyana and Suriname have Chinese and Portuguese communities, as well as a small number of Jews in Suriname. French Guiana's population is largely African; there are also minorities of European, Chinese, and Hmong descent. French Guiana has also been a recipient of immigration from surrounding countries, especially Guyana, Suriname, and Brazil, as well as from Haiti.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Population, total". World Bank. 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ "Produits intérieurs bruts régionaux et valeurs ajoutées régionales de 2000 à 2020" (in French). Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ Rogoziński, Ian (1999). A Brief History of the Caribbean, from the Arawak and Carib to the Present. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-3811-2.

- ^ a b Radin, Paul (1942). Indians of South America. New York: Doubleday. OCLC 491517.

- ^ Parry, J. H. (1979). The Discovery of South America. New York: Taplinger. ISBN 0-8008-2233-1.

- ^ Robert Harcourt, A Relation of a Voyage to Guiana (1613; repr., London Hakluyt Society Press, 1928), p. 4

- ^ a b Hyles, Joshua (2010). Guiana and the Shadows of Empire (Master's thesis). Baylor University. hdl:2104/7936.

- ^ Sir Walter Raleigh, The Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Bewtiful Empyre of Guiana (1596; repr., Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1968) and The Discovery of Guiana, and the Journal of the Second Voyage Thereto (1606; repr., London: Cassell, 1887).

- ^ a b Goslinga, Cornelis (1971). The Dutch in the Caribbean and on the Wild Coast. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-0280-X.

- ^ Smith, Raymond T. (1962). British Guiana. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 485746.

- ^ Watkins, Thayer. "Political and Economic History of French Guiana". San Jose State University Faculty Research. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Aldrich (1996). Greater France: a History of French Overseas Expansion. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-16000-3.

- ^ P.J. Blok; P.C. Molhuysen, eds. (1927). "Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek. Deel 7". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "Ciudad Bolivar Population 2023".

Further reading

[edit]- Bahadur, Gaiutra. Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture. The University of Chicago (2014) ISBN 978-0-226-21138-1

The Guianas

View on GrokipediaGeography

Physical Features

The Guianas region, encompassing Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, is underlain by the Guiana Shield, a Precambrian craton approximately 1.7 billion years old composed primarily of metamorphic rocks, greenstone belts, and intrusive formations such as gabbros.[10] This ancient geological basement gives rise to a diverse terrain featuring low coastal plains, extensive savannas, dense tropical rainforests, and rugged interior highlands with plateaus, escarpments, and tepuis—flat-topped table mountains.[10] The region's landforms reflect minimal tectonic activity since the Precambrian era, resulting in eroded peneplains interrupted by steep valleys and inselbergs. Along the Atlantic coastline, spanning roughly 1,600 kilometers collectively, the Guianas exhibit narrow alluvial plains, swampy lowlands, mudflats, and mangrove forests, with widths typically 10-30 kilometers in French Guiana and similar in neighboring territories.[11] These coastal zones transition inland to savanna grasslands and forested peneplains, covering much of the flatter interiors where slopes are predominantly less than 5 degrees.[12] Further south, the landscape elevates into low mountains and plateaus, including the granite-dominated terrains that host bauxite deposits and support vast rainforest canopies. The interior highlands host prominent mountain ranges, such as the Pakaraima Mountains along the Guyana-Venezuela border, reaching elevations up to 2,810 meters at Mount Roraima, characterized by sandstone tepuis with sheer cliffs exceeding 400 meters.[13] In Suriname, the Wilhelmina Mountains peak at 1,230 meters on Julianatop, while Guyana's Kanuku Mountains rise to 1,067 meters amid rolling hills; French Guiana's Tumuc-Humac and Inini-Camopi ranges top out around 850 meters, forming watersheds for transboundary rivers.[13] These features contribute to dramatic waterfalls, including Guyana's Kaieteur Falls with a 226-meter drop.[13] A dense network of rivers drains northward to the Atlantic, with major systems including Guyana's Essequibo (the longest at approximately 1,010 kilometers), the Courantyne forming the Guyana-Suriname border, Suriname's 480-kilometer namesake river, and French Guiana's Maroni and Oyapock, which delineate boundaries with Suriname and Brazil, respectively.[11] These waterways, varying from blackwater to clear streams, originate in the shield's highlands and traverse rainforests, facilitating sediment transport and biodiversity corridors across the region's predominantly forested expanse exceeding 80% coverage.[10]Climate and Environment

The Guianas exhibit a tropical rainforest climate characterized by high temperatures, elevated humidity, and abundant precipitation throughout the year, with minimal seasonal variation in temperature but distinct wet and dry periods driven by the migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone. Average daytime temperatures range from 28°C to 32°C (82°F to 90°F), with nighttime lows around 21°C to 24°C (70°F to 75°F), and relative humidity often exceeding 80%. Annual rainfall typically totals 2,000 to 3,000 mm (79 to 118 inches), concentrated in two rainy seasons: a shorter one from November to January and a longer one from April to August, though patterns vary slightly by country—Suriname records peak monthly rainfall of about 300 mm (12 inches) in May and June, while French Guiana experiences its primary wet period from December to June.[14][15][16] The region's environment is dominated by the Guiana Shield, a Precambrian geological formation spanning approximately 1.7 million square kilometers and supporting some of the world's most intact lowland rainforests, which cover over 85% of the land area and store an estimated 18% of global tropical forest carbon stocks. These forests harbor exceptional biodiversity, including over 8,000 plant species, more than 1,000 bird species, and high endemism rates for amphibians and mammals, positioning the Shield as a global hotspot for ecological value. The ecosystems regulate regional hydrology and climate, with intact forests contributing to stable precipitation patterns across northern South America; simulations indicate that replacing just 28% of the Shield's rainforest with savanna could double local runoff and precipitation while disrupting broader continental weather dynamics.[3][17] Environmental pressures have intensified in recent decades, primarily from artisanal and industrial gold mining, which cleared 53,700 hectares of forest between 2015 and 2018, accumulating to 213,623 hectares of deforestation by that year—half occurring in Guyana alone—and contaminating freshwater systems with mercury. Logging and infrastructure development exacerbate habitat fragmentation, though overall deforestation rates remain lower than in the central Amazon, at under 0.1% annually in some Shield areas. Conservation efforts include protected areas covering about 20% of the region, such as Guyana's Iwokrama Forest and Suriname's Central Suriname Nature Reserve, but face challenges from illegal activities and limited enforcement; rising temperatures projected for the Shield could further slow forest dynamics and amplify biodiversity declines without aggressive mitigation.[18][19][20]History

Pre-Colonial Period

The Guianas, encompassing the coastal and interior regions of present-day Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, and adjacent areas in Venezuela and Brazil, were inhabited by diverse indigenous groups prior to European contact in the late 15th century. Archaeological investigations reveal human occupation spanning several millennia, with evidence of settlements, earthworks, and modified landscapes indicating adaptation to varied environments including coastal mangroves, savannas, and rainforests. Key sites in western French Guiana document cultural sequences from approximately 5000 BP, featuring shell middens, pottery, and early agricultural modifications such as raised fields and drainage ditches, though denser forest interiors yield sparser pre-2000 BP artifacts due to preservation challenges and limited exploration.[21][22][23] Linguistic and ethnohistorical analyses identify primary language families as Cariban, Arawakan, and Waraoan, with Carib-speaking groups predominant in southern and inland zones, Arawak speakers along coastal and riverine areas, and Warao (Warrau) in swampy deltas. Ethnohistorical reconstructions suggest a migratory sequence: Warao groups as possible earliest arrivals, followed by Arawak migrations from the Orinoco and Rio Negro basins around 2000 years ago, and later Carib influxes from the Xingu and Tapajós regions, reflecting broader Amazonian population dynamics. These groups maintained semi-sedentary to nomadic lifestyles, with Warao emphasizing canoe-based fishing and foraging in aquatic habitats—their autonym deriving from terms denoting "canoe people"—while Arawak and Carib communities developed village-based societies supported by shifting cultivation.[24][25][26] Subsistence relied on a mix of slash-and-burn agriculture (cultivating manioc, maize, and sweet potatoes), hunting, fishing, and gathering, evidenced by tools like ground-stone axes, pottery with incised designs, and landscape alterations such as savanna field systems in central Guyana. Social organization varied, with Arawak groups forming hierarchical villages potentially numbering hundreds, marked by communal houses and ritual centers, whereas Carib bands were more egalitarian and mobile, often engaging in intergroup raids that shaped regional interactions. Pre-Columbian population growth in the broader Amazonian biome, including the Guianas, followed a logistic model, accelerating over the 1700 years before 1492 CE through technological and environmental adaptations, though estimates remain approximate due to post-contact depopulation. Trade networks exchanged goods like salt, feathers, and stone tools across savanna-rainforest ecotones, fostering cultural exchanges among these groups.[23][27][28]European Colonization and Exploitation

European powers first encountered the Guianas during Christopher Columbus's third voyage in 1498, when he sighted the mainland coast, but initial Spanish expeditions in 1499–1500 failed to establish lasting settlements due to indigenous resistance and inhospitable conditions.[29] Spanish claims under the Treaty of Tordesillas nominally extended to the region, yet lacked effective occupation, allowing Dutch, English, and French interests to dominate from the early 17th century onward.[30] The Dutch initiated substantive colonization in the western Guianas, establishing trading posts along the Essequibo River around 1580 and expanding into permanent agricultural settlements by the mid-17th century, including the colonies of Essequibo, Demerara, and Berbice (collectively forming modern Guyana).[30] These efforts focused on exploiting fertile coastal soils for cash crops, beginning with tobacco and cotton before shifting to sugarcane by the 1660s; enslaved Africans, imported from West Africa starting in the mid-17th century, provided the coerced labor essential to plantation viability amid high mortality from disease and harsh conditions.[30] In Suriname (then Dutch Guiana), English planters founded the first permanent settlement in 1651 at what became Paramaribo, cultivating sugar with slave labor, but the Dutch seized control in 1667 via the Treaty of Breda, exchanging it for New Amsterdam (modern New York); under Dutch administration, Suriname emerged as a premier plantation colony, exporting sugar, coffee, cacao, indigo, and timber by the 18th century, reliant on tens of thousands of African slaves.[29] French colonization of eastern Guiana (modern French Guiana) began with exploratory attempts in 1604, leading to intermittent settlements disrupted by Dutch incursions, including their occupation of Cayenne in 1664; France secured permanent control in 1667 through the same Treaty of Breda, founding Cayenne as the administrative center.[31] Like its neighbors, French Guiana's economy centered on plantations producing sugar and coffee, powered by enslaved African labor imported from the 17th century, though smaller scale and frequent setbacks limited output compared to Dutch and British holdings.[31] Territorial control shifted amid Anglo-Dutch and Napoleonic Wars: Britain captured Dutch Guianas in 1796 and 1803, purchasing Essequibo, Demerara, and Berbice outright in 1814 and unifying them as British Guiana in 1831, where by 1807 approximately 100,000 slaves supported an intensified sugar economy.[30] Britain briefly occupied Suriname (1799–1802, 1804–1815) but returned it to Dutch rule, while French Guiana endured British assaults before reverting to France.[29] Exploitation intensified across the region through the 18th century, with slave-based monocultures driving exports but fostering revolts, such as those in Berbice (1763) and Demerara (1823); abolition of the slave trade occurred in Britain (1807) and the Netherlands (1814), followed by full emancipation in French Guiana (1848), British Guiana (1838), and Dutch Guiana (1863), after which planters transitioned to indentured Asian labor to sustain profitability.[30][29][31]Independence and Post-Colonial Era

British Guiana attained independence from the United Kingdom on May 26, 1966, establishing the independent nation of Guyana with Forbes Burnham of the People's National Congress as prime minister.[32][33] Guyana became a republic within the Commonwealth on February 23, 1970, with Arthur Chung as its first president.[34] Under Burnham's leadership, the government pursued socialist policies, including nationalization of key industries like bauxite mining in the 1970s, amid ethnic divisions between the Afro-Guyanese-dominated PNC and the Indo-Guyanese-supported People's Progressive Party led by Cheddi Jagan.[35] Political instability marked the era, with allegations of electoral irregularities favoring the PNC until Jagan's electoral victory in 1992 restored PPP governance.[36] A persistent territorial dispute arose with Venezuela over the Essequibo region, comprising two-thirds of Guyana's territory; the 1966 Geneva Agreement sought resolution, but Venezuela's claims persisted, leading to International Court of Justice proceedings initiated by Guyana in 2018.[37][38] Suriname achieved independence from the Netherlands on November 25, 1975, transitioning from associate status within the Kingdom granted in 1954.[39] Initial civilian governments faced economic challenges and ethnic fragmentation among Hindustani, Creole, Javanese, and Maroon communities, culminating in a 1980 military coup led by Desi Bouterse, who established de facto rule.[40] Bouterse's regime oversaw purges, including the execution of 15 opponents in 1982, sparking a civil war with Maroon insurgents that lasted until 1992; partial democratization occurred in 1988, but Bouterse later served as elected president from 2010 to 2020 before his conviction for the 1982 killings.[41] Suriname also contended with border disputes, including maritime claims with Guyana resolved by a 2007 UN tribunal award favoring Suriname's continental shelf position.[42] French Guiana, integrated as an overseas department of France since 1946, has not pursued successful independence, maintaining full representation in the French parliament and European Union as part of metropolitan France.[43] Post-colonial development centered on the Guiana Space Centre at Kourou, established in 1964, which generates significant employment and GDP contributions through launches by the European Space Agency, though illegal gold mining and undocumented migration from Brazil and Suriname pose ongoing security and environmental challenges.[44] Social unrest, including strikes in 2017 over living costs and infrastructure, highlighted disparities despite subsidies from France.[45] Across the Guianas, post-colonial trajectories diverged: Guyana and Suriname grappled with authoritarianism, ethnic politics, and resource-dependent economies, while French Guiana benefited from French fiscal transfers but faced integration tensions; regional cooperation remains limited amid historical rivalries and differing international alignments.[8]

Political Structure

Sovereign States and Dependencies

The sovereign states of the Guianas region are Guyana and Suriname. Guyana, a parliamentary republic and member of the Commonwealth of Nations, attained independence from the United Kingdom on May 26, 1966, following a period of British colonial rule as British Guiana.[32] Suriname, a presidential republic, secured independence from the Kingdom of the Netherlands on November 25, 1975, after operating as an autonomous territory within the Dutch realm since 1954.[39] French Guiana constitutes the principal dependency in the region, functioning as an overseas department and region of France with full integration into the French Republic.[46] Established in this status on March 19, 1946, it elects representatives to the French National Assembly and Senate, applies French law, and utilizes the euro as currency, while lacking independent foreign policy or defense capabilities.[46] Broader definitions of the Guianas occasionally incorporate the Guayana region of Venezuela and the state of Amapá in Brazil as historical or geographical extensions, but these form integral territories of their respective sovereign nations—Venezuela and the Federative Republic of Brazil—without separate status as states or dependencies.[47] No other active dependencies or non-self-governing territories exist within the core Guianas coastal area.Governance and Political Challenges

Guyana functions as a parliamentary republic where the president, currently Irfaan Ali following his reelection in 2025, holds executive authority and is indirectly elected by the National Assembly amid a multiparty system often divided along ethnic lines between Indo-Guyanese and Afro-Guyanese populations.[48] [49] Political challenges persist, including entrenched corruption, clientelism, and ethnic tensions that polarize elections, as evidenced by the protracted 2020 vote count disputes involving fraud allegations that tested democratic institutions.[48] [50] The territorial dispute with Venezuela over the oil-rich Essequibo region, comprising two-thirds of Guyana's claimed land, has intensified in 2025 with Venezuelan military incursions, such as the March 1 gunboat entry into Guyanese waters, and threats of retaliation amid U.S. naval deployments supporting Guyana.[51] [52] Calls for constitutional reform to mitigate winner-take-all electoral dynamics and foster inclusive governance remain unaddressed, exacerbating disparities fueled by rapid oil-driven growth averaging 39.8% annually from 2021 to 2024.[53] [37] Suriname maintains a constitutional democracy with a president, Chan Santokhi since 2020, elected by the National Assembly in a fragmented, ethnicity-based multiparty landscape prone to coalition instability.[54] Governance faces pervasive corruption, clientelism, and the lingering effects of military rule under Desi Bouterse, whose 1980 coup, 1982 executions of opponents, and cocaine trafficking convictions—finalized before his 2024 death—undermined rule of law and entrenched impunity through amnesty laws.[54] [55] The 2025 elections highlighted these fractures, with ethnic affiliations dominating voter alignments and economic reforms struggling against historical authoritarian legacies that fostered discontent and potential unrest.[56] [57] French Guiana, an overseas department of France since 1946, integrates into the French Republic with a prefect representing the central government, a locally elected assembly, and representation in the French parliament, limiting autonomous decision-making on key fiscal and security matters.[58] Political challenges center on demands for expanded self-governance, culminating in 2025 negotiations for devolved powers over local competencies like education and health, amid chronic social strains including high unemployment, illegal immigration from Suriname and Brazil, and territorial inequities that fuel protests.[59] [58] Separatist sentiments persist but lack majority support, complicated by reliance on French subsidies and EU outermost region status, which constrain reforms without risking economic isolation.[59] Across the Guianas, shared challenges include corruption's erosion of public trust, ethnic or communal divisions in politics, and external pressures like resource disputes, though divergent statuses—independent republics versus French integration—shape responses, with oil booms in Guyana and Suriname amplifying governance tests around equitable distribution.[48] [54] [60]Economy

Natural Resources and Industries

The Guianas possess substantial natural resources, including extensive tropical rainforests covering over 90% of the land in French Guiana and significant portions in Guyana and Suriname, alongside mineral deposits such as bauxite, gold, and emerging offshore oil and gas reserves.[7] [61] These resources underpin extractive industries that dominate the regional economy, with mining and energy sectors contributing approximately 30% of GDP in Suriname and driving rapid growth in Guyana following commercial oil production initiation in late 2019.[62] [63] In Guyana, key minerals include bauxite, gold, and diamonds, while agriculture features sugar and rice production; however, oil has transformed the economy, with production averaging an annual increase of 98,000 barrels per day from 2020 to 2023, tripling overall GDP.[64] The country's Natural Resource Fund reached $1.7 billion by June 2023, reflecting oil revenues.[65] Mining and agriculture each account for about 20% of real GDP.[64] Suriname's economy relies heavily on gold mining, bauxite for alumina production, and nascent oil exploration, with the mineral sector comprising 60% of GDP and nearly 90% of exports as of recent assessments.[66] Additional resources encompass timber, hydropower potential, and small-scale diamond extraction, supporting industries that exported mining goods amid high global commodity prices through 2023.[67] [68] French Guiana's industries center on gold mining, timber harvesting, and fishing, supplemented by construction and public works; its economy also benefits from the high-tech European Space Agency's Guiana Space Centre, though natural resources like bauxite and iron remain underexploited relative to biodiversity assets.[69] Despite abundant forests and minerals, economic activity lags due to infrastructural challenges.[70]Economic Transformations and Disparities

The economies of the Guianas transitioned from colonial-era plantation agriculture and extractive industries, such as sugar and bauxite, to post-independence reliance on commodities amid political instability and nationalization efforts in the 1970s-1980s, which often led to stagnation and debt accumulation.[7] Guyana and Suriname faced socialist policies that deterred investment, resulting in GDP contraction or low growth until market-oriented reforms in the 1990s; French Guiana, remaining under French administration, benefited from integration into the EU's single market and structural funds. Recent decades have seen divergent paths driven by resource discoveries and institutional ties, with causal factors including governance quality, foreign investment, and geopolitical status determining outcomes.[71] Guyana's economy transformed dramatically following ExxonMobil's 2015 discovery of over 11 billion barrels of recoverable oil offshore, with commercial production commencing in 2019 and output surging to 650,000 barrels per day by mid-2024, positioning it as a top global crude growth contributor outside OPEC.[72] This fueled average annual GDP growth exceeding 40% from 2020-2023, elevating GDP per capita from approximately $4,500 in 2014 to $32,330 in 2024, though challenges persist in diversifying beyond oil and managing Dutch disease effects on non-oil sectors. Suriname, hampered by chronic fiscal mismanagement, corruption, and a 2020-2022 hyperinflation episode exceeding 50%, pursued IMF-supported reforms including debt restructuring, achieving single-digit inflation by 2024 but with projected growth limited to 3%, reliant on gold exports and nascent offshore oil prospects delayed until 2027.[71] [73] French Guiana's economy, buoyed by its status as a French overseas department, derives stability from transfers exceeding 50% of GDP, EU outermost region programs like POSEI (€278 million annually for agriculture), and the Guiana Space Centre, which generates €0.27 in local wages per euro spent on operations, supporting 2,500 direct jobs amid Ariane and Vega launches.[74] [75] Economic disparities across the Guianas are stark, reflecting differences in sovereignty, resource management, and external support:| Territory | GDP per Capita (2024, USD) | Key Driver |

|---|---|---|

| Guyana | 32,330 | Oil production |

| French Guiana | ~35,000 (est. EUR equiv.) | EU/French transfers, space |

| Suriname | ~6,500 | Gold, limited diversification |

Demographics

Ethnic and Cultural Composition

In Guyana, the 2012 population and housing census reported Indo-Guyanese (descendants of 19th-century Indian indentured laborers) as the largest group at 39.8% (297,493 individuals), followed by Afro-Guyanese (descendants of enslaved Africans) at 30.1%, mixed-race individuals at 19.9%, Amerindians at 10.5%, and smaller groups including Chinese, Portuguese, and others at about 0.7%.[78] Suriname's 2012 census indicated a more fragmented composition, with Hindustani (Indian-origin) at 27.4%, Maroons (descendants of escaped African slaves) at 21.7%, Creoles (mixed African-European descent) at 15.7%, Javanese (from Dutch East Indies indentured labor) at 13.7%, unspecified "other" at 13.4%, Amerindians at 3.8%, Chinese at 1.5%, and Europeans at 1.2%; Afro-Surinamese groups (Maroons and Creoles combined) constitute roughly 37% overall.[79] In French Guiana, no comprehensive ethnic census exists due to French policy against collecting such data, but estimates from 2010-2020 indicate about 66% Black or mixed Afro-European-indigenous (Creoles), 12% White Europeans, 12% Amerindians and other indigenous, with the remainder including East Indians, Chinese, Brazilians, Haitians, and Surinamese immigrants; foreign nationals comprise 35.5% of residents.[80]| Country | Largest Group(s) | Key Percentages (Recent Estimates/Censuses) |

|---|---|---|

| Guyana | Indo-Guyanese, Afro-Guyanese | Indo 39.8%, Afro 30.1%, Mixed 19.9%, Amerindian 10.5% (2012)[78] |

| Suriname | Hindustani, Afro-Surinamese | Hindustani 27.4%, Maroons 21.7%, Creoles 15.7%, Javanese 13.7%, Amerindian 3.8% (2012)[79] |

| French Guiana | Creoles (mixed Black/European) | Creoles ~66%, White 12%, Indigenous ~12% (2010s est.)[80] |

Population Dynamics and Migration

The populations of the three main Guianas exhibit distinct dynamics influenced by differing colonial legacies, economic conditions, and migration policies. Guyana's population stood at approximately 836,000 in 2024, with an annual growth rate of 0.57% as of 2023, reflecting modest natural increase tempered by persistent outflows.[85][86] Suriname's population reached about 640,000 in 2024, growing at 0.9% annually, driven by births but offset by emigration.[85][87] French Guiana, as an overseas department of France, had a population of roughly 309,000 in 2024, with a higher growth rate exceeding 2.5% due to both elevated fertility and net immigration.[88][89] Across the region, low overall densities—typically under 5 people per square kilometer—stem from vast rainforests and historical settlement patterns concentrated along coasts.| Country/Territory | Population (2024 est.) | Annual Growth Rate (recent) | Net Migration (recent est.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guyana | 836,000 | 0.57% (2023) | Negative (~ -5,000 annually) |

| Suriname | 640,000 | 0.9% (2024) | -1,166 (2024) |

| French Guiana | 309,000 | >2.5% (2024) | Positive (~1,500 annually) |