Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hoboken, New Jersey

View on Wikipedia

Hoboken (/ˈhoʊboʊkən/ HOH-boh-kən;[22] Unami: Hupokàn)[23] is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Hoboken is part of the New York metropolitan area and is the site of Hoboken Terminal, a major transportation hub. As of the 2020 United States census, the city's population was 60,419,[11][12] an increase of 10,414 (+20.8%) from the 2010 census count of 50,005,[24] which in turn reflected an increase of 11,428 (+29.6%) from the 38,577 counted in the 2000 census.[25] The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated a population of 57,010 for 2023,[14] making it the 708th-most populous municipality in the nation.[13] With more than 42,400 inhabitants per square mile (16,400/km2) in data from the 2010 census, Hoboken was ranked as the third-most densely populated municipality in the United States among cities with a population above 50,000.[26] In the 2020 census, the city's population density climbed to more than 48,300 inhabitants per square mile (18,600/km2) of land, ranked fourth in the county behind Guttenberg, Union City and West New York.[11][27]

Key Information

Hoboken was first settled by Europeans as part of the Pavonia, New Netherland colony in the 17th century. During the early 19th century, the city was developed by Colonel John Stevens, first as a resort and later as a residential neighborhood. Originally part of Bergen Township and later North Bergen Township, it became a separate township in 1849 and was incorporated as a city in 1855. Hoboken is the location of the first recorded game of baseball and of the Stevens Institute of Technology, one of the oldest technological universities in the United States.

It is also known as the birthplace and hometown of the word-famous singer and actor Frank Sinatra (1915–1998); various streets and parks in the city have been named after him.

Located on the Hudson Waterfront, the city was an integral part of the Port of New York and New Jersey and was home to major industries for most of the 20th century. The character of the city has changed from an artsy industrial vibe from the days when Maxwell House coffee, Lipton tea, Hostess Cupcakes, and Wonder Bread called Hoboken home, to one of trendy shops and expensive condominiums.[28] It was ranked 2nd in Niche's "2019 Best Places to Live in Hudson County" list,[29] and 1st in 2022.[30]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The name Hoboken was chosen by Colonel John Stevens when he bought land, on a part of which the city still sits. The Lenape, later called Delaware Indian tribe of Native Americans, referred to the area as the "land of the tobacco pipe", most likely to refer to the soapstone collected there to carve tobacco pipes, and used a phrase that became "Hopoghan Hackingh".[31][32][33] Like Weehawken, its neighbor to the north, as well as Communipaw and Harsimus to the south, Hoboken had many variations in the folks-tongue. Hoebuck, old Dutch for high bluff, and likely referring to Castle Point, the district of the city highest above sea level, was used during the colonial era, and was later spelled as Hobuck,[34] Hobock,[35] Hobuk[36] and Hoboocken.[37] However, in the nineteenth century, the name was changed to Hoboken, influenced by Flemish immigrants, and a folk etymology had emerged, linking the town of Hoboken to the similarly-named Hoboken district of Antwerp.[38]

Hoboken has been nicknamed the Mile Square City,[1] but it actually occupies about 1.25 sq mi (3.2 km2) of land.[2] During the late 19th/early 20th century the population and culture of Hoboken was dominated by German language speakers who sometimes called it "Little Bremen", many of whom are buried in Hoboken Cemetery, North Bergen.[39][40]

Early-European arrival and colonial period

[edit]

Hoboken was originally an island which was surrounded by the Hudson River on the east and tidal lands at the foot of the New Jersey Palisades on the west. It was a seasonal campsite in the territory of the Hackensack, a phratry of the Lenni Lenape, who used the serpentine rock found there to carve pipes.[31]

The first recorded European to lay claim to the area was Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing for the Dutch East India Company, who anchored his ship the Halve Maen (Half Moon) at Weehawken Cove on October 2, 1609.[41] An entry made in the journal of Hudson's mate, Robert Juet, on that date, is the earliest known reference to the area today known as Hoboken, and would be the last known such reference until twenty years later.[42] Soon after the area became part of the province of New Netherland.[citation needed]

In 1630, Michael Reyniersz Pauw, a burgemeester (mayor) of Amsterdam and a director of the Dutch West India Company, received a land grant as patroon on the condition that he would plant a colony of not fewer than fifty persons within four years on the west bank of what had been named the North River. Three Lenape sold the land that became Hoboken and part of Jersey City for 80 fathoms (146 m) of wampum, 20 fathoms (37 m) of cloth, 12 kettles, six guns, two blankets, one double kettle, and half a barrel of beer.[41] These transactions, variously dated as July 12, 1630 and November 22, 1630, represent the earliest known conveyance for the area. Pauw, whose Latinized name is Pavonia, failed to settle the land, and he was obliged to sell his holdings back to the company in 1633.[citation needed]

It was later acquired by Hendrick Van Vorst, who leased part of the land to Aert Van Putten, a farmer. In 1643, north of what would be later known as Castle Point, Van Putten built a house and a brewery, North America's first. In series of Indian and Dutch raids and reprisals, Van Putten was killed and his buildings destroyed, and all residents of Pavonia, as the colony was then known, were ordered back to New Amsterdam.[43]

In 1664, the English took possession of New Amsterdam with little to no resistance, and in 1668 they confirmed a previous land patent by Nicolas Verlett. In 1674–1675, the area became part of East Jersey, and the province was divided into four administrative districts, Hoboken becoming part of Bergen County, where it remained until the creation of Hudson County on February 22, 1840. English-speaking settlers (some relocating from New England) interspersed with the Dutch, but it remained sparsely populated and agrarian.[citation needed]

Eventually, the land came into the possession of William Bayard, who originally supported the revolutionary cause, but became a Loyalist Tory after the fall of New York in 1776 when the city and surrounding areas, including the west bank of the renamed Hudson River, were occupied by the British. At the end of the Revolutionary War, Bayard's property was confiscated by the Revolutionary Government of New Jersey. In 1784, the land described as "William Bayard's farm at Hoebuck" was bought at auction by Colonel John Stevens for £18,360 (then $90,000).[41]

19th century

[edit]

In the early 19th century, Colonel John Stevens developed the waterfront as a resort for Manhattanites.[44] On October 11, 1811, Stevens' ship the Juliana, began to operate as a ferry between Manhattan and Hoboken, making it the world's first commercial steam ferry.[45] In 1825, he designed and built a steam locomotive capable of hauling several passenger cars at his estate.[46] Sybil's Cave, a cave with a natural spring, was opened in 1832 and visitors came to pay a penny for a glass of water from the cave which was said to have medicinal powers.[47] In 1841, the cave became a legend, when Edgar Allan Poe wrote "The Mystery of Marie Roget" about an event that took place there.[48] The cave was closed in the late 1880s after the water was found to be contaminated, and it was shut and in the 1930s and filled with concrete, before it was reopened in 2008.[49] Before his death in 1838, Stevens founded the Hoboken Land and Improvement Company, which laid out a regular system of streets, blocks and lots, constructed housing, and developed manufacturing sites. In general, the housing consisted of masonry row houses of three to five stories, some of which survive to the present day, as does the street grid.[50]

Hoboken was originally formed as a township on April 9, 1849, from portions of North Bergen Township. As the town grew in population and employment, many of Hoboken's residents saw a need to incorporate as a full-fledged city, and in a referendum held on March 29, 1855, ratified an Act of the New Jersey Legislature signed the previous day, and the City of Hoboken was born.[51] In the subsequent election, Cornelius V. Clickener became Hoboken's first mayor. On March 15, 1859, the Township of Weehawken was created from portions of Hoboken and North Bergen Township.[51]

Based on a bequest from Edwin A. Stevens, Stevens Institute of Technology was founded at Castle Point in 1870, at the site of the Stevens family's former estate, as the nation's first mechanical engineering college.[52]

By the late 19th century, shipping lines were using Hoboken as a terminal port, and the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad (later the Erie Lackawanna Railroad) developed a railroad terminal at the waterfront, with the present NJ Transit terminal designed by architect Kenneth Murchison constructed in 1907.[53] It was also during this time that German immigrants, who had been settling in town during most of the century, became the predominant population group in the city, at least partially due to its being a major destination port of the Hamburg America Line, though anti-German sentiment during World War I led to a rapid decline in the German community.[54] In addition to the primary industry of shipbuilding, Hoboken became home to Keuffel and Esser's three-story factory and in 1884, to Tietjen and Lang Drydock (later Todd Shipyards). Well-known companies that developed a major presence in Hoboken after the turn-of the-century included Maxwell House, Lipton Tea, and Hostess.[55]

Birthplace of baseball

[edit]

The first officially recorded game of baseball took place in Hoboken in 1846 between Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine at Elysian Fields.[56] In 1845, the Knickerbocker Club, which had been founded by Alexander Cartwright, began using Elysian Fields to play baseball due to the lack of suitable grounds on Manhattan.[57] Team members included players of the St George's Cricket Club, the brothers Harry and George Wright, and Henry Chadwick, the English-born journalist who coined the term "America's Pastime".[citation needed]

By the 1850s, several Manhattan-based members of the National Association of Base Ball Players were using the grounds as their home field while St. George's continued to organize international matches between Canada, England and the United States at the same venue. In 1859, George Parr's All England Eleven of professional cricketers played the United States XXII at Hoboken, easily defeating the local competition. Sam Wright and his sons Harry and George Wright played on the defeated United States team, a loss which inadvertently encouraged local players to take up baseball. Henry Chadwick believed that baseball and not cricket should become the national pastime after the game drawing the conclusion that amateur American players did not have the leisure time required to develop cricket skills to the high technical level required of professional players. Harry Wright and George Wright then became two of the first professional baseball players in the United States when Aaron Champion raised funds to found the Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1869.[citation needed]

In 1865, the grounds hosted a championship match between the Mutual Club of New York City and the Atlantic Club of Brooklyn that was attended by an estimated 20,000 fans and captured in the Currier & Ives lithograph "The American National Game of Base Ball".[58]

With the construction of two significant baseball parks enclosed by fences in Brooklyn, enabling promoters there to charge admission to games, the prominence of Elysian Fields diminished. In 1868 the leading Manhattan club, Mutual, shifted its home games to the Union Grounds in Brooklyn. In 1880, the founders of the New York Metropolitans and New York Giants finally succeeded in siting a ballpark in Manhattan that became known as the Polo Grounds.[citation needed]

20th century

[edit]

Few nonwhites had settled in Hoboken by 1901. The Brooklyn Eagle claimed that an unwritten sundown town policy prevented African Americans from residing or working there.[59]

World War I

[edit]When the U.S. entered World War I, the Hamburg-American Line piers in Hoboken and New Orleans were taken under eminent domain.[60] Federal control of the port and anti-German sentiment led to part of the city being placed under martial law, and many German immigrants were forcibly moved to Ellis Island or left the city of their own accord.[61] Hoboken became the major point of embarkation and more than three million soldiers, known as "doughboys", passed through the city.[62] Their hope for an early return led to General Pershing's slogan, "Heaven, Hell or Hoboken... by Christmas."[63]

Following the war, Italians, mostly stemming from the Adriatic port city of Molfetta, became the city's major ethnic group, with the Irish also having a strong presence.[64] While the city experienced the Great Depression, jobs in the ships yards and factories were still available, and the tenements were bustling. Middle-European Jews, mostly German-speaking, also made their way to the city and established small businesses. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which was established on April 30, 1921, oversaw the development of the Holland Tunnel (completed in 1927) and the Lincoln Tunnel (in 1937), allowing for easier vehicular travel between New Jersey and New York City, bypassing the waterfront.[citation needed]

Post-World War II

[edit]The war facilitated economic growth in Hoboken, as the many industries located in the city were crucial to the war effort. As men went off to battle, more women were hired in the factories, some (most notably, Todd Shipyards), offering classes and other incentives to them. Though some returning service men took advantage of GI housing bills, many with strong ethnic and familial ties chose to stay in town. During the 1950s, the economy was still driven by Todd Shipyards, Maxwell House,[65] Lipton Tea, Hostess and Bethlehem Steel and companies with big plants were still not inclined to invest in major infrastructure elsewhere.[citation needed]

In the 1960s, working pay and conditions began to deteriorate: turn-of-the century housing started to look shabby and feel crowded, shipbuilding was cheaper overseas, and single-story plants surrounded by parking lots made manufacturing and distribution more economical than old brick buildings on congested urban streets. The city appeared to be in the throes of inexorable decline as industries sought (what had been) greener pastures, port operations shifted to larger facilities on Newark Bay, and the car, truck and plane displaced the railroad and ship as the transportation modes of choice in the United States. Many Hobokenites headed to the suburbs, often the close by ones in Bergen and Passaic Counties, and real-estate values declined. Hoboken sank from its earlier incarnation as a lively port town into a rundown condition and was often included in lists with other New Jersey cities experiencing the same phenomenon, such as Paterson, Elizabeth, Camden, and neighboring Jersey City.[66]

The old economic underpinnings were gone and nothing new seemed to be on the horizon. Attempts were made to stabilize the population by demolishing the so-called slums along River Street and build subsidized middle-income housing at Marineview Plaza, and in midtown, at Church Towers. Heaps of long uncollected garbage and roving packs of semi-wild dogs were not uncommon sights.[67] Though the city had seen better days, Hoboken was never abandoned. New infusions of immigrants, most notably Puerto Ricans, kept the storefronts open with small businesses and housing stock from being abandoned, but there wasn't much work to be had. Washington Street, commonly called "the avenue", was never boarded up, and the tight-knit neighborhoods remained home to many who were still proud of their city. Stevens remained a premier technology school, Maxwell House kept chugging away, and Bethlehem Steel still housed sailors who were dry-docked on its piers. Italian-Americans and other came back to the "old neighborhood" to shop for delicatessen.[citation needed]

In 1975, the western part of the Keuffel and Esser Manufacturing Complex (known as "Clock Towers") was converted into residential apartments, after having been an architectural, engineering and drafting facility from 1907 to 1968;[68] the eastern part portion became residential apartments in 1984 (now called the Grand Adams).[68]

Waterfront

[edit]The Hudson Waterfront defined Hoboken as an archetypal port town and powered its economy from the mid-19th to mid-20th century, by which time it had become essentially industrial (and mostly inaccessible to the general public). The large production plants of Lipton Tea and Maxwell House, and the drydocks of Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation and Todd Shipbuilding dominated the northern portion for many years. On June 30, 1900, a large fire at the Norddeutscher Lloyd piers killed numerous people and caused almost $10 million in damage.[69][70] The southern portion (which had been a U.S. base of the Hamburg-American Line) was seized by the federal government under eminent domain at the outbreak of World War I, after which it became (with the rest of the Hudson County) a major East Coast cargo-shipping port.[citation needed]

With the development of the Interstate Highway System and containerization shipping facilities (particularly at Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal), the docks became obsolete, and by the 1970s were more or less abandoned.[41] A large swath of River Street, known as the Barbary Coast for its taverns and boarding houses (which had been home for many dockworkers, sailors, merchant mariners, and other seamen) was leveled as part of an urban renewal project. Though control of the confiscated area had been returned to the city in the 1950s, complex lease agreements with the Port Authority gave it little influence on its management. In the 1980s, the waterfront dominated Hoboken politics, with various civic groups and the city government engaging in sometimes nasty, sometimes absurd politics and court cases. By the 1990s, agreements were made with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, various levels of government, Hoboken citizens, and private developers to build commercial and residential buildings and "open spaces" (mostly along the bulkhead and on the foundation of un-utilized Pier A).[71]

The northern portion, which had remained in private hands, has also been re-developed. While most of the dry-dock and production facilities[72][73] were razed to make way for mid-rise apartment houses, many sold as investment condominiums, some buildings were renovated for adaptive re-use (notably the Tea Building, formerly home to Lipton Tea,[74] and the Machine Shop, home of the Hoboken Historic Museum).[75] Zoning requires that new construction follow the street grid and limits the height of new construction to retain the architectural character of the city and open sight-lines to the river. Downtown, Frank Sinatra Park and Sinatra Drive honor the man most consider to be Hoboken's most famous son, while uptown the name Maxwell recalls the factory with its smell of roasting coffee wafting over town and its huge neon "Good to the Last Drop" sign, so long a part of the landscape. The midtown section is dominated by the serpentine rock outcropping atop of which sits Stevens Institute of Technology (which also owns some, as yet, undeveloped land on the river). At the foot of the cliff is Sybil's Cave (where 19th century day-trippers once came to "take the waters" from a natural spring), long sealed shut, though plans for its restoration are in place. The promenade along the river bank is part of the Hudson River Waterfront Walkway, a state-mandated master plan to connect the municipalities from the Bayonne Bridge to George Washington Bridge and provide contiguous unhindered access to the water's edge and to create an urban linear park offering expansive views of the Hudson with the spectacular backdrop of the New York skyline. As of 2017, the city was considering using eminent domain to take over the last operating maritime industry in the city, the Union Dry Dock.[76][77]

1970s–present

[edit]During the late 1970s and 1980s, the city witnessed a speculation spree, fueled by transplanted New Yorkers and others who bought many turn-of-the-20th-century brownstones in neighborhoods that the still solid middle and working class population had kept intact and by local and out-of-town real-estate investors who bought up late 19th century apartment houses often considered to be tenements. Hoboken experienced a wave of fires, some of which were arson.[78][79][80] Applied Housing, a real-estate investment firm, used federal government incentives to renovate "sub-standard" housing and receive subsidized rental payments (commonly known as Section 8), which enabled some low-income, displaced, and disabled residents to move within town. Hoboken attracted artists, musicians, upwardly mobile commuters, and "bohemian types" interested in the socioeconomic possibilities and challenges of a bankrupt New York and who valued the aesthetics of Hoboken's residential, civic and commercial architecture, its sense of community, and relatively (compared to Lower Manhattan) less expensive rents, all a quick, train hop away.

These trends in development resembled similar growth and change patterns in Brooklyn and downtown Jersey City and Manhattan's East Village—and to a lesser degree, SoHo and TriBeCa—which previously had not been residential. Empty lots were built on, tenements were transformed into luxury condominiums. Hoboken felt the impact of the destruction of the World Trade Center intensely, many of its newer residents having worked there. Re-zoning encouraged new construction on former industrial sites on the waterfront and the traditionally more impoverished low-lying west side of the city where, in concert with Hudson-Bergen Light Rail and New Jersey State land-use policy, transit villages are now being promoted.[81] Once a blue collar town characterized by live poultry shops and drab taverns, it has since been transformed into a town filled with gourmet shops and luxury condominiums.[79]

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy caused widespread flooding in Hoboken, leaving 1,700 homes flooded and causing $100 million in damage after the storm "filled up Hoboken like a bathtub",[82] leaving the city without electricity for days, and requiring the summoning of the National Guard.[83] Workers in Hoboken had the highest rate of public transportation use in the nation, with 56% commuting daily via mass transit.[84] Hurricane Sandy caused seawater to flood half the city, crippling the PATH station at Hoboken Terminal when more than 10 million gallons of water dumped into the system. In December 2013 Mayor Dawn Zimmer testified before a U.S. Senate Committee on the impact the storm had on Hoboken's businesses and residents,[85][86] and in January 2014 she stated that Lieutenant Governor Kim Guadagno and Richard Constable, a member of governor Chris Christie's cabinet, deliberately held back Hurricane Sandy relief funds from the city in order to pressure her to approve a Christie ally's developmental project,[87][88] a charge that the Christie administration denied.[89][90][91] In June 2014, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development allocated $230 million to Hoboken as part of its Rebuild by Design initiative, adding levees, parks, green roofs, retention basins and other infrastructure to help the low-lying riverfront city protect itself from ordinary flooding and build a network of features to help Hoboken future-proof itself against subsequent storms.[92]

The project included expanding the city's sewer capacity, incorporating cisterns and basins into parks and playgrounds, redesigning streets to minimize traffic accidents, and collect and redirect waster. By September 2023, the improvements were so successful that when a storm hit the area that month, depositing 3.5 inches on the city, including 1.44 inches during the hour coinciding with high tide, only a few inches of standing water remains at three of the city's 277 intersections by the evening, resulting in only three towed cars, and no cancelation of any city events. In an article that November for The New York Times, Michael Kimmelman compared this to the storm's effects in New York City, whose government focused on flood walls and breakwaters, but not rainwater, resulting in several subway lines being submerged in water, and thigh-high water levels in Brooklyn streets. For this, the article hailed Hoboken as a "climate change success story."[83]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2 square miles (5.2 square kilometres), including 1.25 sq mi (3.2 km2) of land and 0.75 sq mi (1.9 km2) of water (37.50%).[93]

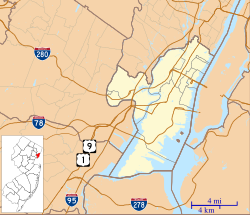

Hoboken lies on the west bank of the Hudson River between Weehawken and Union City to the north and Jersey City (the county seat) to the south and west.[94][95][96] Directly across the Hudson River are the Manhattan, New York City neighborhoods of the West Village and Chelsea.

Hoboken is laid out in a grid. North–south streets are named (Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, Harrison, and Clinton, for example). The numbered streets running east–west start two blocks north of Observer Highway with First Street, with the grid ending close to 16th near Weehawken Cove and the city line.[96] Castle Point (or Stevens Point[97]), The Projects, Hoboken Terminal, and Hudson Tea are distinct enclaves at the city's periphery. The "Northwest" is a name being used for that part of the city as it transforms from its previous industrial use into a residential district.[98][99]

Hoboken's ZIP Code is 07030[17] and its area code is 201.[100]

Climate

[edit]Hoboken's temperatures hover around an average in winter, rising and falling, rather than a consistent pattern with a clear coldest time of year, with minimums occurring in late December and early-mid February, rising and falling repeatedly throughout January.[101] Just like neighboring New York City, the climate is humid subtropical (Cfa).

| Climate data for Hoboken | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

75 (24) |

86 (30) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

101 (38) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

94 (34) |

84 (29) |

75 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 38 (3) |

42 (6) |

50 (10) |

61 (16) |

71 (22) |

79 (26) |

84 (29) |

83 (28) |

75 (24) |

64 (18) |

54 (12) |

43 (6) |

62 (17) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 27 (−3) |

29 (−2) |

35 (2) |

45 (7) |

54 (12) |

64 (18) |

69 (21) |

68 (20) |

61 (16) |

50 (10) |

42 (6) |

32 (0) |

48 (9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −6 (−21) |

−15 (−26) |

3 (−16) |

12 (−11) |

28 (−2) |

44 (7) |

52 (11) |

50 (10) |

39 (4) |

28 (−2) |

7 (−14) |

−13 (−25) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.65 (93) |

3.21 (82) |

4.36 (111) |

4.50 (114) |

4.19 (106) |

4.41 (112) |

4.60 (117) |

4.44 (113) |

4.28 (109) |

4.40 (112) |

4.02 (102) |

4.00 (102) |

50.06 (1,273) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.5 (19) |

6.8 (17) |

3.0 (7.6) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

3.9 (9.9) |

22.1 (55.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.0 | 5.6 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 77.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.0 | 6.5 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 20.4 |

| Source: [102] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 2,668 | — | |

| 1860 | 9,662 | 262.1% | |

| 1870 | 20,297 | 110.1% | |

| 1880 | 30,999 | 52.7% | |

| 1890 | 43,648 | 40.8% | |

| 1900 | 59,364 | 36.0% | |

| 1910 | 70,324 | 18.5% | |

| 1920 | 68,166 | −3.1% | |

| 1930 | 59,261 | −13.1% | |

| 1940 | 50,115 | −15.4% | |

| 1950 | 50,676 | 1.1% | |

| 1960 | 48,441 | −4.4% | |

| 1970 | 45,380 | −6.3% | |

| 1980 | 42,460 | −6.4% | |

| 1990 | 33,397 | −21.3% | |

| 2000 | 38,577 | 15.5% | |

| 2010 | 50,005 | 29.6% | |

| 2020 | 60,419 | 20.8% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 57,010 | [11][13][14] | −5.6% |

| Population sources: 1850–1920[103] 1860–1930[22] 1850–1870[104] 1850[105] 1870[106] 1880–1890[107] 1890–1910[108] 1910–1930[109] 1940–2000[110] 2000[111] 2010[24] 2020[11][12] | |||

2020 census

[edit]The 2020 United States census counted 60,419 people, 28,175 households, and 12,177 families in Hoboken.[112][113] The population density was 48,335.2 per square mile (18,662.2/km2). There were 30,202 housing units at an average density of 24,161.6 per square mile (9,328.8/km2).[113][114] The racial makeup was 70.69% (42,711) white or European American (67.29% non-Hispanic white), 4.11% (2,484) black or African-American, 0.18% (107) Native American or Alaska Native, 10.89% (6,581) Asian, 0.09% (57) Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian, 5.34% (3,225) from other races, and 8.7% (5,254) from two or more races.[115] Hispanic or Latino of any race was 14.14% (8,542) of the population.[116]

Of the 28,175 households, 20.9% had children under the age of 18; 33.2% were married couples living together; 30.3% had a female householder with no spouse or partner present. 34.5% of households consisted of individuals and 5.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older.[113] The average household size was 2.1 and the average family size was 2.7.[117] The percent of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher was estimated to be 57.0% of the population.[118]

15.6% of the population was under the age of 18, 9.8% from 18 to 24, 53.3% from 25 to 44, 15.1% from 45 to 64, and 6.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.2 males.[113] For every 100 females ages 18 and older, there were 99.9 males.[113]

The 2016-2020 5-year American Community Survey estimates show that the median household income was $153,438 (with a margin of error of +/- $9,118). The median family income was $200,132 (+/- $18,994).[119] Males had a median income of $100,368 (+/- $5,816) versus $77,081 (+/- $3,810) for females. The median income for those above 16 years old was $86,005 (+/- $2,370).[120] Approximately, 2.4% of families and 7.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.1% of those under the age of 18 and 11.0% of those ages 65 or over.[121][122]

2010 census

[edit]The 2010 United States census counted 50,005 people, 25,041 households, and 9,465 families in the city. The population density was 39,212.0 per square mile (15,139.8/km2). There were 26,855 housing units at an average density of 21,058.7 per square mile (8,130.8/km2). The racial makeup was 82.24% (41,124) White, 3.53% (1,767) Black or African American, 0.15% (73) Native American, 7.12% (3,558) Asian, 0.03% (15) Pacific Islander, 4.29% (2,144) from other races, and 2.65% (1,324) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 15.20% (7,602) of the population.[24]

Of the 25,041 households, 15.5% had children under the age of 18; 28.8% were married couples living together; 6.9% had a female householder with no husband present and 62.2% were non-families. Of all households, 39.7% were made up of individuals and 5.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.93 and the average family size was 2.68.[24]

12.2% of the population were under the age of 18, 12.1% from 18 to 24, 55.9% from 25 to 44, 13.5% from 45 to 64, and 6.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31.2 years. For every 100 females, the population had 101.8 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 100.7 males.[24]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $101,782 (with a margin of error of +/− $3,219) and the median family income was $121,614 (+/− $18,466). Males had a median income of $90,878 (+/− $6,412) versus $67,331 (+/− $3,710) for females. The per capita income for the city was $69,085 (+/− $3,335). About 9.6% of families and 11.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.7% of those under age 18 and 24.4% of those age 65 or over.[123]

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 census, there were 38,577 people, 19,418 households, and 6,835 families residing in the city. The population density was 30,239.2 inhabitants per square mile (11,675.4/km2), fourth highest in the nation after neighboring communities of Guttenberg, Union City and West New York.[124] There were 19,915 housing units at an average density of 15,610.7 per square mile (6,027.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 80.82% White, 4.26% African American, 0.16% Native American, 4.31% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 7.63% from other races, and 2.78% from two or more races. Furthermore, 20.18% of residents considered themselves to be Hispanic or Latino.[111][125]

There were 19,418 households, out of which 11.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 23.8% were married couples living together, 9.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 64.8% were non-families. 41.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.92 and the average family size was 2.73.[111][125]

In the city the age distribution of the population showed 10.5% under the age of 18, 15.3% from 18 to 24, 51.7% from 25 to 44, 13.5% from 45 to 64, and 9.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females, age 18 and over, there were 103.9 males.[111][125]

The median income for a household in the city as of the 2000 census was $62,550, while the median income for a family was $67,500. Males had a median income of $54,870 versus $46,826 for females. The per capita income for the city was $43,195. 11.0% of the population and 10.0% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 23.6% of those under the age of 18 and 20.7% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[111][125]

The city is a bedroom community of New York City, where most of its employed residents work. Based on the 2000 Census Worker Flow Files, about 53% of the employed residents of Hoboken (13,475 out of 25,306) worked in one of the five boroughs of New York City, as opposed to about 15% working within Hoboken.[126]

Economy

[edit]The first centrally air-conditioned public space in the United States was demonstrated at Hoboken Terminal.[127] The first Blimpie restaurant opened in 1964 at the corner of Seventh and Washington Streets.[128][129] Hoboken is home to one of the headquarters of publisher John Wiley & Sons, which moved from Manhattan in 2002.[130]

According to the New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, Hoboken's unemployment rate as of 2014 was 3.3%, compared to a 6.5% in Hudson County as a whole.[131] In 2018, Hoboken had an unemployment rate of 2.1%, vs. 3.9% countywide.[132]

A 2014 study showed that Stevens Institute of Technology contributed $117 million to Hoboken's economy in 2014, reflecting the university's nearly $100 million payroll for salaries and wages, as well as other goods and services acquired, construction and off-campus spending by students and visitors. The university is responsible for 1,285 full-time jobs.[133]

Parks and recreation

[edit]

The four parks were originally laid out within city street grid in the 19th century were Church Square Park, Columbus Park, Elysian Park and Stevens Park. Four other parks that were developed later but fit into the street pattern are Gateway Park, Jackson Street Park, Legion Park and Madison Park.[134]

More recently built parks throughout the city include Pier C,[135] a reconstructed pier accessed by a curving walkway along lower Sinatra Drive. A multi-use sports field called 1600 Park opened in 2013,[136] while the one-acre Southwest Park was completed along Jackson Street and Paterson Avenue in 2017.[137] As of 2019, the city was considering expanding the park to a property across the street.[138]

A two-acre park and public plaza called 7th and Jackson Resiliency Park opened in 2019. It includes a playground, an acre of open lawn space, a new indoor gymnasium, play sculptures, and infrastructure to capture over 450,000 gallons of rainwater to reduce flooding.[139]

Construction of the 5.4-acre (2.2 ha) Northwest Resiliency Park broke ground in 2019. Amenities in the $90 million park's design include a great lawn, a stage, a central fountain that can be converted into a seasonal ice skating rink, a pavilion, playgrounds, and athletic fields. Also incorporated into the park are a number of environmentally friendly provisions, including both underground and above ground stormwater detention system that can store up to 2 million US gallons (7,600,000 litres) of water to help mitigate flooding. The park, which is located at 12th and Adams Streets,[140] opened in June 2023.[141]

A 2014 renovation to the 14th Street Viaduct near the city's northwest edge saw the creation of several recreational areas underneath the structure that include a dog park, passive recreation areas, and street hockey and basketball courts amid a new cobblestone streetscape.[142]

The Hudson River Waterfront Walkway is a state-mandated master plan to connect the municipalities from the Bayonne Bridge to the George Washington Bridge creating an 18 mi (29 km)-long urban linear park and provide contiguous unhindered access to the water's edge. By law, any development on the waterfront must provide a public promenade with a minimum width of 30 ft (9.1 m). To date, completed segments in Hoboken and the new parks and renovated piers that abut them are at Hoboken Terminal, Pier A, the promenade and bike path from Newark to 5th Streets, Frank Sinatra Park, Castle Point Park, Sinatra Drive to 12th to 14th Streets, New York Waterway Pier, 14th Street Pier, and 14th Street north to southern side of Weehawken Cove. Other segments of river-front held privately are not required to build a walkway until the land is re-developed.[143]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Since 1992, the Hudson Shakespeare Company has been the resident Shakespeare Festival of Hudson County performing a free Shakespeare production for each month of the summer. Since 1998, the group has performed "Shakespeare Mondays" at Frank Sinatra Park (410 Frank Sinatra Drive) as part of their annual Shakespeare in the Park tour.[144] Hoboken is also home to cultural attractions such as Barsky Gallery[145] and creative institutions such as the Hoboken Historical Museum[146] and the Monroe Center.[147]

Annual cultural events

[edit]Hoboken has many annual events such as the Frank Sinatra Idol Contest,[148] Hoboken Comedy Festival,[149] Hoboken House Tour,[150] Hoboken International Film Festival,[151] Hoboken Studio Tour,[152] Hoboken Arts and Music Festival, Hoboken (Secret) Garden Tour[153] and Movies Under the Stars.[154] The Hoboken Farmer's Market occurs every Tuesday, June through October.[155] There are also numerous festivals such as the Saint Patrick's Day Parade,[156] Feast of Saint Anthony's,[157] Saint Ann's Feast[158] and the Hoboken Italian Festival.[159]

From the 1960s until 2011, Hoboken was home to the Macy's Parade Studio, which houses many of the floats for the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade.[160][161][162] Many Stevens students, alumni, and staff members volunteer in the preparation and piloting of the parade floats.[163] The studio was moved out of Hoboken and into a converted former Tootsie Roll Factory in Moonachie, New Jersey 2011.[160]

Government and public service

[edit]Local government

[edit]

The City of Hoboken is governed within the Faulkner Act (formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law) under the mayor-council (Plan D) system of municipal government, implemented based on the recommendations of a Charter Study Commission as of January 1, 1953.[164] The city is one of 71 municipalities (of the 564) statewide that use this form of government.[165][166] The governing body is comprised of the Mayor and the nine-member City Council. The city council includes three members elected at-large from the city as a whole, and six members who each represent one of the city's six wards.[167] All of the members of the city council are elected to four-year terms of office in non-partisan elections on a staggered basis in odd-numbered years, with the six ward seats up for election together and the three at-large and mayoral seats up for vote two years later.[8][168]

In July 2011, the city council voted to move municipal elections from May to November. The first shifted election were held in November 2013, with all officials elected in 2009 and 2011 having their terms extended by six months.[169]

As of 2025[update], the mayor of Hoboken is Ravinder Bhalla, whose term of office ends December 31, 2025.[4] Members of the city council are Council President James J. Doyle (2025; at-large), Council Vice President Phil Cohen (2027; 5th Ward), Tiffanie Fisher (2027; 2nd Ward), Emily Jabbour (2025; at-large), Paul Presinzano (2027; 1st Ward), Joseph Quintero (2025; at-large), Ruben J. Ramos Jr. (2027; 4th Ward) and Michael Russo (2027; 3rd Ward), with the seat from the 6th ward being vacant.[170][171][172][173][174][175]

Since November 2024, the 6th Ward is vacant following the death of five-time-elected councilwoman Jen Giattin. Her seat, expiring in 2027, will be filled in the November 2025 general election, when voters will choose a candidate to serve the balance of the term of office.[176]

In the 2017 general election, Ravinder Bhalla was elected to succeed Dawn Zimmer, becoming the state's first Sikh mayor; Zimmer had chosen not to run for re-election to a third term and had endorsed Bhalla for the post. Bhalla's running mates, incumbents James Doyle and Emily Jabbour, won two of the at-large seats, while the third seat was won Vanessa Falco who had been aligned with the slate of mayoral candidate Michael DeFusco.[177][178] Zimmer had been the city council president and first took office as mayor on July 31, 2009, after her predecessor, Peter Cammarano,[179] was arrested on allegations of corruption stemming from a decade-long FBI operation.[180] Zimmer, who lost a June 9, 2009, runoff election to Cammarano by 161 votes, served as acting mayor starting on July 31, 2009, making her the city's first female mayor.[181] She won a special election to fill the remainder of the term on November 3, 2009, and was sworn in as mayor on November 6.[182] Zimmer won re-election in November 2013 to a second term of office and began her second term in January 2014.[183]

Federal, state, and county representation

[edit]

Hoboken is located in the 8th Congressional District[184] and is part of New Jersey's 32nd state legislative district.[185]

For the 119th United States Congress, New Jersey's 8th congressional district is represented by Rob Menendez (D, Jersey City).[186][187] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027) and Andy Kim (Moorestown, term ends 2031).[188]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 32nd legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Raj Mukherji (D, Jersey City) and in the General Assembly by John Allen (D, Hoboken) and Jessica Ramirez (D, Jersey City).[189]

Hudson County is governed by the directly elected Hudson County Executive and by a Board of County Commissioners, which serves as the county's legislative body. As of 2025[update], Hudson County's Hudson County Executive is Craig Guy (D, Jersey City), whose term of office expires December 31, 2027.[190] Hudson County's Commissioners are Kenneth Kopacz (D, District 1 - Bayonne and parts of Jersey City; 2026, Bayonne),[191][192] William O'Dea (D, District 2 - Western Jersey City; 2026, Jersey City),[193][194] Vice Chair Jerry Walker (D, District 3 - South Eastern Jersey City[195][196] Yraida Aponte-Lipski (D, District 4 - North Eastern Jersey City; 2026, Jersey City),[197][198] Chair Anthony L. Romano Jr. (D, District 5 - Hoboken and parts of Jersey City; 2026, Hoboken),[199][200] Fanny J. Cedeño (D, District 6 - Union City; 2026, Union City),[201][202] Caridad Rodriguez (D, District 7 - Weehawken, West New York, and Gutenberg; 2026, West New York),[203][204] Robert Bascelice (D, District 8 - West New York, North Bergen, Secaucus; 2026, North Bergen)[205][206] and Albert J. Cifelli (D, District 9 - Secaucus, Kearny, East Newark, Harrison; 2026, Harrison)[207][208][209][210][211]

Hudson County's constitutional officers are County Clerk E. Junior Maldonado (D, Jersey City, 2027),[212][213] Register Jeffrey Dublin (D, Jersey City, 2026)[214][215][216] Sheriff Frank X. Schillari (R, Jersey City, 2025)[217][218] and Surrogate Tilo E. Rivas (D, Jersey City, 2029)[219][220][221]

Politics

[edit]As of March 2011, there were a total of 35,532 registered voters in Hoboken, of which 14,385 (40.5%) were registered as Democrats, 3,881 (10.9%) were registered as Republicans and 17,218 (48.5%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 48 voters registered to other parties.[222]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2021 | 3,683 | 28.44% | 9,148 | 70.63% | 121 | 0.93% |

| 2017 | 3,154 | 23.23% | 10,422 | 76.77% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2013 | 6,562 | 53.05% | 5,565 | 44.99% | 243 | 1.96% |

| 2009 | 4,307 | 30.30% | 9,095 | 63.99% | 811 | 5.71% |

| 2005 | 2,498 | 23.44% | 7,935 | 74.47% | 223 | 2.09% |

In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 66.1% of the vote (14,443 cast), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 32.4% (7,078 votes), and Libertarian and Green candidates with 1.5% (325 votes), among the 22,018 ballots cast by the city's 40,209 registered voters (172 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 54.8%.[224][225] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 71.0% of the vote here (17,051 cast), ahead of Republican John McCain with 27.5% (6,590 votes) and other candidates with 0.9% (225 votes), among the 24,007 ballots cast by the city's 38,970 registered voters, for a turnout of 61.6%.[226] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 65.0% of the vote here (13,436 ballots cast), outpolling Republican George W. Bush with 33.4% (6,898 votes) and other candidates with 0.5% (161 votes), among the 20,668 ballots cast by the city's 31,221 registered voters, for a turnout percentage of 66.2.[227]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024[228] | 29.1% 7,673 | 67.9% 17,932 | 3.0% 612 |

| 2020[229] | 22.2% 6,259 | 74.7% 21,046 | 3.1% 493 |

| 2016[230] | 22.5% 5,034 | 72.0% 16,111 | 4.5% 1,006 |

| 2012[231] | 32.4% 7,078 | 66.1% 14,443 | 1.5% 325 |

| 2008[232] | 27.5% 6,590 | 71.0% 17,051 | 0.9% 225 |

| 2004[233] | 33.4% 6,898 | 65.0% 13,436 | 0.5% 161 |

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 53.0% of the vote (6,562 cast), ahead of Democrat Barbara Buono with 45.0% (5,565 votes), and other candidates with 2.0% (243 votes), among the 16,331 ballots cast by the city's 41,094 registered voters (3,961 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 39.7%.[234][235] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 62.3% of the vote here (9,095 ballots cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 29.5% (4,307 votes), Independent Chris Daggett with 4.6% (673 votes) and other candidates with 0.9% (138 votes), among the 14,593 ballots cast by the city's 34,844 registered voters, yielding a 41.9% turnout.[236]

On November 7, 2017, City Councilmember Ravinder Bhalla was elected as mayor, making him the first Sikh mayor in the state's history.[237] He was re-elected in November 2021.[238]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2024 | 7,503 | 30.40% | 16,625 | 67.35% | 555 | 2.25% |

| 2018 | 5,170 | 26.28% | 13,932 | 70.81% | 572 | 2.91% |

| 2012 | 5,695 | 29.89% | 12,819 | 67.28% | 538 | 2.82% |

| 2006 | 2,812 | 25.01% | 8,256 | 73.43% | 176 | 1.57% |

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 6,690 | 24.72% | 19,916 | 73.60% | 455 | 1.68% |

| 2014 | 2,040 | 23.71% | 6,381 | 74.16% | 183 | 2.13% |

| 2013 | 1,376 | 21.52% | 4,935 | 77.18% | 83 | 1.30% |

| 2008 | 5,747 | 30.02% | 12,920 | 67.49% | 476 | 2.49% |

Fire department

[edit]| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Established | 1891 |

| Annual calls | ~3,500 |

| Employees | 132 |

| Staffing | Career |

| Fire chief | Brian Crimmins |

| EMS level | First Responder BLS |

| Facilities and equipment | |

| Battalions | 1 |

| Stations | 4 |

| Engines | 4 |

| Trucks | 2 |

| Rescues | 1 |

| HAZMAT | 1 |

| USAR | 1 |

| Fireboats | 1 |

The city is protected by the 132 paid firefighters of the city of Hoboken Fire Department (HFD). Established in 1891, the HFD currently operates under the command of a Department Chief, to whom two Deputy Chiefs report.[241] The department reported to 3,352 emergency calls in 2010, arriving in an average of 2.6 minutes from the time the original call was received.[242] The HFD has been a Class 1 rated fire department since 1996 as determined by the Insurance Services Office, one of only three in New Jersey, joining Hackensack and Cherry Hill.[243][244] HFD's firehouses, including its fire museum, are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[245]

The department is part of the Metro USAR Strike Team, which consists of nine North Jersey fire departments and other emergency services divisions working to address major emergency rescue situations.[246]

Fire station locations and apparatus

[edit]Fire station and company locations in Hoboken are:[247][248][249]

| Engine company | Ladder company | Special unit | Chief unit | Address | Neighborhood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine 1 | Ladder 1 | Fire Boat 1 (docked in Shipyard Marina), Spare Ladder 3 | 1313 Washington Street | Uptown | |

| Engine 2 | Ladder 2 | Spare Engine 5 | 43 Madison Street | Downtown | |

| Engine 3 | Rescue 1 (which is also part of the Metro USAR Collapse Rescue Strike Team)[246] | 801 Clinton Street | Uptown | ||

| Engine 4 | Haz-Mat 1, Spare Rescue 2, Spare Engine 6 | Car 155 (Deputy Chief/Tour Commander) | 201 Jefferson Street | Midtown |

The Fire Museum is located at 213 Bloomfield Street.[249][250]

Emergency medical services

[edit]EMS in the city of Hoboken is provided primarily by the members of the Hoboken Volunteer Ambulance Corps (HVAC), which was established in 1971. HVAC does not charge for the services it provides. HVAC has seven emergency vehicles, in addition to six bicycles that can be used to provide coverage at outdoor events.[251]

Hoboken University Medical Center, founded in 1863 as St. Mary's Hospital, is a historic hospital and the oldest in continuous operation in the state.[252] It is a community hospital and part of the CarePoint Health System.[253]

Social services

[edit]HOPES Community Action Partnership, Incorporated (HOPES CAP, Inc. / HOPES) was established in 1964 under President Lyndon B. Johnson's administration signing the Economic Opportunity Act.[254] The majority of HOPES program participants have incomes below the federal poverty threshold. Services include those for youth enrichment, adults, senior assistance, and early childhood development.[255]

Homelessness in the city is addressed by the Hoboken Homeless Shelter, one of the three homeless shelters in the county.[256] In December 2018, the city of Hoboken installed eight parking meters in high foot-traffic areas, painted orange, to collect donations to benefit homelessness initiatives.[257]

Transportation

[edit]

Hoboken has the highest public transportation use of any city in the United States, with 56% of working residents using public transportation for commuting purposes each day.[258] Hoboken Terminal, located at the city's southeastern corner, is a national historic landmark originally built in 1907 by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad.[259] The terminal is the origination/destination point for several modes of transportation and an important hub within the NY/NJ metropolitan region's public transit system.[citation needed]

The number of residents parking on Hoboken streets decreased from 2010 to 2015.[260] Hudson Bike Share, a bicycle sharing system operated by nextbike, opened[261] in October 2015.[262] Amid conflicts with Jersey City, which used Citi Bike,[263] Hoboken ceased using Hudson Bike Share in May 2021, and adopted Citi Bike itself, thus connecting the town's bicycle sharing network with the ones already operating in Jersey City and New York City.[264]

Pedestrian safety

[edit]In the late 2010s, Hoboken implemented a number of improvements to make certain intersections and roads safer. These include giving pedestrians lead time before turning traffic lights green; installing vertical delineator post or a flexible bollard to prevent cars from parking within 25 feet of intersections, thus improving sightlines for motorists in order to allow them to avoid cyclists, pedestrians, and other cars. By 2022, the city had not seen a traffic death in four years.[265][266]

Rail

[edit]NJ Transit's Main Line, Bergen County Line, Pascack Valley Line, Montclair-Boonton Line, Morris and Essex Lines and Meadowlands Rail Line terminate at Hoboken Terminal with additional morning weekday service on a single inbound train on the Raritan Valley Line.[267]

The Hudson-Bergen Light Rail, another NJ Transit subsidiary, has three stations in Hoboken–Hoboken Terminal, 2nd Street and 9th Street-Congress Street.[268]

PATH, a 24-hour subway system operated by the Port Authority, operates from Hoboken Terminal to 33rd Street Manhattan, World Trade Center, and Journal Square.[269]

Water

[edit]NY Waterway ferry service makes Hudson River crossings from Hoboken Terminal and 14th Street to Battery Park City Ferry Terminal, Wall Street-Pier 11 and the West Midtown Ferry Terminal in Manhattan.[270]

Surface

[edit]

New Jersey Transit buses 22, 22X, 23, 64, 68, 85, 87, 89, and 126 terminate at Hudson Place/Hoboken Terminal.[271][272][273]

Academy Bus Lines has a garage in Hoboken, operating most of their NYC services from there.[citation needed] Taxi service is available for a flat fare within city limits and negotiated fare for other destinations. Zipcar is located downtown at the Center Parking Garage on Park Avenue, between Newark Street and Observer Highway.[274]

Roads and highways

[edit]

As of May 2010[update], the city had a total of 31.79 mi (51.16 km) of roadways, of which 26.71 mi (42.99 km) were maintained by the municipality and 5.08 mi (8.18 km) by Hudson County.[275]

The 14th Street Viaduct connects Hoboken to Paterson Plank Road in Jersey City Heights. Two highway tunnels that connect New Jersey to New York are located close to Hoboken. The Lincoln Tunnel is north of the city in Weehawken. The Holland Tunnel is south of the city in downtown Jersey City.[276]

Air

[edit]Hoboken has no airports. Airports which serve Hoboken are operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. These airports are Newark Liberty International Airport, LaGuardia Airport and John F. Kennedy Airport.[277]

Education

[edit]Hoboken has a highly educated population. Based on data from the American Community Survey, it was ranked in 2019 as one of the top 15 most-educated municipalities in New Jersey with a population of at least 10,000, placing first on the list, with 50.2% of residents having bachelor's degree or higher, more than double the 23.4% of residents in New Jersey and 19.1% nationwide who have reached that educational level.[278]

Public schools

[edit]

Hoboken Public Schools is a school district that serves students in pre-kindergarten through twelfth grade.[279] The district is one of 31 former Abbott districts statewide that were established pursuant to the decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court in Abbott v. Burke[280] which are now referred to as "SDA Districts" based on the requirement for the state to cover all costs for school building and renovation projects in these districts under the supervision of the New Jersey Schools Development Authority.[281][282]

As of the 2023–24 school year, the district, comprised of five schools, had an enrollment of 3,531 students and 240.0 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 14.7:1.[283] Schools in the district (with 2023–24 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[284]) are Joseph F. Brandt Elementary School[285] with 611 students in grades K–5, Thomas G. Connors Elementary School[286] with 328 students in grades K–5, Wallace Elementary School[287] with 594 students in grades PreK–5, Hoboken Middle School[288] with 432 students in grades 6–8 and Hoboken High School[289] with 607 students in grades 9–12.[290][291][292]

In addition, Hoboken has three charter schools, which are schools that receive public funds yet operate independently of the Hoboken Public Schools under charters granted by the Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Education. Elysian Charter School serves students in grades K–8, Hoboken Charter School in grades K–12 and Hoboken Dual Language Charter School in grades K–8.[293] In 2018 the New Jersey Department of Education named the Dual Language charter as having one of six "Model Programs" in New Jersey.[294]

Private schools

[edit]Private schools in Hoboken include The Hudson School, All Saint's Episcopal Day School, and Stevens Cooperative School. Hoboken Catholic Academy, a K-8 Catholic school operated by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark,[295] was one of eight private schools recognized in 2017 as an Exemplary High Performing School by the National Blue Ribbon Schools Program of the United States Department of Education.[296]

Higher education

[edit]

Stevens Institute of Technology, which was founded in 1870, is located in the Castle Point section of Hoboken.[52] The university is comprised of three schools and one college; the Charles V. Schaefer Jr. School of Engineering and Science, School of Business, School of Systems and Enterprises and the College of Arts and Letters.[297] Total enrollment is more than 8,800 undergraduate and graduate students across all schools.[298] Stevens is home to three national research centers of excellence and joint research programs focusing on healthcare, energy, finance, defense, STEM education and coastal stability. Stevens also owns most of Castle Point, which is the highest point in Hoboken.[299]

Media

[edit]

Hoboken is located within the New York media market. Regional news was previously covered by The Jersey Journal, a daily newspaper which ceased publication in February 1, 2025.[300] The Hoboken Reporter was the first local weekly published by The Hudson Reporter group of papers,[301] which was based in Hoboken from 1983 - 2016. It then moved its headquarters to Bayonne,[302] before closing in January 2023.[303][304][305] Local reporting can be found on Hoboken Patch.com, and within NJ.com. Other publications, the River View Observer and the Spanish-language El Especialito,[306] also cover local news, as does The Stute, the campus newspaper at Stevens Institute of Technology.

The city has been the location of several film productions. Elia Kazan's Academy Award-winning 1954 film On the Waterfront, was shot in Hoboken.[307][308] A wedding scene in the 1997 Jennifer Aniston film Picture Perfect was filmed at the Elks Club at 1005 Washington Street.[309] The 1998 Adrien Brody film Restaurant is set in Hoboken.[310] The production company for the 2009 film Assassination of a High School President was based in Hoboken.[311] The 2024 Bob Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown filmed at 10 locations in Hoboken.[312] The children's book The Hoboken Chicken Emergency takes place in the city.[313]

The city is home to Carlo's Bake Shop, which was featured from 2009 to 2020 in the TLC reality show Cake Boss. The popularity of the show resulted in increased business for Carlo's Bake Shop, and increased tourism to the Hoboken area,[314] although the long lines drove away some of the shop's local customers.[315]

The fourth season of A&E's Parking Wars, which documents the lives and duties of parking enforcement personnel, was filmed in Hoboken, in addition to its usual venues of Detroit and Philadelphia.[316] The ABC Primetime magazine Primetime: What Would You Do? has filmed multiple episodes of their social experiments in Hoboken's shops and restaurants.[317][318]

The 1989 television series Dream Street was set and shot in Hoboken.[319]

Bands from Hoboken include alternative rock pioneers The Bongos[320] and the art-rock band Yo La Tengo.[321]

Notable people

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Rodas, Steven. "Is Hoboken officially the 'Mile Square City'? Delving into the longstanding nickname" Archived November 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Hudson Reporter, January 17, 2016. Accessed June 2, 2016. "The same way New Yorkers call their city The Big Apple, many people refer to Hoboken as the 'Mile-Square City' or 'Mile Square City'. Despite the fact that the city covers 1.27 square miles on land (close to 2 if you count the water), the nickname has stuck through the years and made it into the appellations of local businesses, a bar, and a theater company."

- ^ a b c d e 2019 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Places Archived March 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- ^ US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990 Archived August 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Meet the Mayor Archived July 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, City of Hoboken. Accessed September 26, 2025.

- ^ NJ Mayors Directory, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed June 1, 2025.

- ^ Department of Administration, City of Hoboken. Accessed September 26, 2025.

- ^ City Clerk Archived July 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, City of Hoboken. Accessed September 26, 2025.

- ^ a b 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 145.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ "City of Hoboken". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f QuickFacts Hoboken city, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c Total Population: Census 2010 - Census 2020 New Jersey Municipalities, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 20,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2023 Population: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023[permanent dead link], United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 30, 2024. Note that townships (including Edison, Lakewood and Woodbridge, all of which have larger populations) are excluded from these rankings.

- ^ a b c Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Population Density by County and Municipality: New Jersey, 2020 and 2021, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ "City of Hoboken unveils Frank Sinatra statue on 106th birthday of famous Hobokenite", City of Hoboken, December 13, 2021. Accessed May 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Look Up a ZIP Code Archived May 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Postal Service. Accessed November 27, 2011.

- ^ Area Code Lookup - NPA NXX for Hoboken, NJ Archived May 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Area-Codes.com. Accessed December 30, 2014.

- ^ U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 31, 2008.

- ^ Geographic Codes Lookup for New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- ^ Board on Geographic Names[permanent dead link], United States Geological Survey, January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b Heilprin, Angelo; Heilprin, Louis (1916). Lippincott's new gazetteer: a complete pronouncing gazetteer or geographical dictionary of the world, containing the most recent and authentic information respecting the countries, cities, towns, resorts, islands, rivers, mountains, seas, lakes, etc., in every portion of the globe, Part 1. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. p. 833. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ Hoboken Archived June 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Lenape Talking Dictionary. Accessed June 2, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1: Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Hoboken city, Hudson County, New Jersey Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed February 1, 2012.

- ^ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ Maciag, Mike. "Population Density for U.S. Cities Statistics" Archived December 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Governing, November 29, 2017. Accessed December 4, 2020. "The following are the most densely populated cities with populations exceeding 50,000:... [3rd] Hoboken, N.J.: 42,484 persons/sq. mile"

- ^ "Diversity, density and change in Hoboken and other Hudson County municipalities", Fund for a Better Waterfront, September 7, 2021. Accessed January 18, 2023. "Hudson is the most densely populated county in New Jersey, which is the most densely populated state in the country. Hudson County also contains the four most densely populated cities in the nation: Guttenberg, Union City, West New York and Hoboken. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, Hoboken has 47,202 people per square mile, in fourth place behind the three other Hudson municipalities."

- ^ Martin, Antoinette. "Less Luster on the 'Gold Coast'" Archived October 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, October 29, 2010. Accessed September 24, 2012. "In Hoboken the inventory was just over nine months. In Jersey City it had swelled to 17.6 months."

- ^ "2019 Best Places to Live in Hudson County". Niche. 2019. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "2022 Best Places to Live in Hudson County". Niche. 2022. Archived from the original on January 18, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Abridged History of Hoboken" Archived May 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Hoboken Museum, Accessed February 24, 2015.

- ^ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names Archived November 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed September 1, 2015.

- ^ Gannett, Henry. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States, p. 158. United States Government Printing Office, 1905. Accessed September 1, 2015.

- ^ Hoboken Reporter January 16, 2005

- ^ Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675–1776, Volume 8 Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p. 428. Archived at Google Books. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- ^ History of Hoboken Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, WNET. Accessed September 1, 2015. "The following description of Hobuk, as it was then known, comes from a letter written in 1685 by a George Scott, of Edinburg"

- ^ New Jersey Colonial Records, East Jersey Records: Part 1 – Volume 21 Calendar of Records 1664–1703 Archived February 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, USGenWeb Archives. Accessed November 27, 2011.

- ^ Van Der Sijs, Nicoline. Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops: The Influence of Dutch on the North American Languages Archived August 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, p. 109. Amsterdam University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-9089641243. Accessed June 2, 2016.

- ^ "Hoboken Historical Museum Hosts Publication Party for Oral History Chapbook, "A Nice Tavern" Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Hoboken Historical Museum. Accessed November 17, 2010.

- ^ Applebome, Peter. "Our Towns; Jitters About Who's in Charge on the Waterfront, in 1917 and Today" Archived September 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, March 5, 2006. Accessed September 13, 2018. "And Hoboken, where as early as the 1850s, more than 1,500 of the 7,000 inhabitants were of German origin, was known as Little Bremen, and had an elaborate network of German beer gardens and restaurants, social clubs, newspapers, theaters and schools."

- ^ a b c d Short History of Hoboken Archived May 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Hoboken Historical Museum. Accessed September 1, 2015.

- ^ W.H. Drescher, Jr. (1903). "I: First Owners of West Hoboken.". History of West Hoboken, NJ: 1609 - 1903. Lehne & Drescher. p. 7.

- ^ King, Rebecca (August 23, 2022). "An ill-fated brewery in Hoboken was America's oldest". NorthJersey.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ Gordon, Thomas Francis (1834). A Gazetteer of the State of New Jersey: Comprehending a General View of Its Physical and Moral Condition, Together with a Topographical and Statistical Account of Its Counties, Towns, Villages, Canals, Rail Roads, &c., Accompanied by a Map. Daniel Fenton. ISBN 978-0-7222-0244-9. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "History: Steamboats" Archived June 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Stevens Institute of Technology. Accessed April 16, 2012. "Thus, in 1811 the Colonel purchased a commercial ferry license in New York state and operated a horse powered ferry while building a steam ferry, the Juliana. When the Juliana was put into service from Hoboken to New York, the Stevenses inaugurated what is reputed to be the first regular commercially operated steam ferry in the world."

- ^ Burks, Edward C. "Hoboken to Pay Tribute To 5‐Wheel Locomotive" Archived October 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, May 13, 1976. Accessed August 19, 2020.

- ^ Jennemann, Tom. "Excavation of Sybil's Cave to begin Tuesday Site was location of natural spring, inspiration for Poe murder mystery" Archived April 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Hudson Reporter, January 25, 2005. Accessed April 16, 2012. "Roberts said that the benches they will add will hark back to a time when the city's waterfront was a retreat for wealthy New Yorkers. Sybil's Cave was first opened as a day trippers' attraction in 1832, according to an Aug. 9, 1934 story in the Hoboken Dispatch."

- ^ Fahim, Kareem. "'Open Sesame' Just Won't Do: Hoboken Tries to Unlock Its Cave" Archived June 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, June 26, 2007. Accessed April 16, 2012. "In 1841, the bloodied body of Mary Cecilia Rogers drifted to shore near the mouth of Sybil's Cave, and into legend, the subject of a thriller by Edgar Allan Poe."

- ^ Baldwin, Carly. "Sybil's Cave reopened -- amid controversy" Archived August 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, The Jersey Journal/ NJ.com, October 21, 2008, updated April 2, 2019. Accessed November 13, 2019. "Hoboken Mayor Dave Roberts celebrated the re-opening of the historic Sybil's Cave this morning. But, as Hoboken wrestles with a state takeover and residents face a 47 percent tax hike, some say Sybil's Cave is just another example of what they call the mayor's spendthrift ways."

- ^ Colrick, Patricia Florio. Hoboken Archived August 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. p. 6. Arcadia Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0-7385-3730-6. Accessed April 16, 2012. "Hoboken was laid out in a grid pattern in 1804, on the Loss Map by the inventor and the owner of much of the land, Colonel John Stevens."

- ^ a b Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 148. Accessed May 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Leading Innovation: A Brief History of Stevens Archived November 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Stevens Institute of Technology. Accessed November 5, 2017. "When inventor Edwin A. Stevens died in 1868, his will provided for the establishment of the university that now bears his family's name. Two years later, in 1870, Stevens Institute of Technology opened, offering a rigorous engineering curriculum leading to the degree of Mechanical Engineer following a course of study firmly grounded both in scientific principles and the humanities."

- ^ Hughes, C. J. "Reviving the Glory of Hoboken Terminal" Archived October 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, December 21, 2005. Accessed April 16, 2012. "The Hoboken Terminal, built in 1907, is a two-story Beaux-Arts structure designed by Kenneth Murchison, an architect with the firm of McKim, Mead & White, which designed the original Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan."

- ^ Skontra, Alan. "A History of Hoboken's Immigrants: Dr. Christina Ziegler-McPherson presented her new book at the museum." Archived June 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, HobokenPatch, July 18, 2011. Accessed April 16, 2012. "Hoboken's population started to grow when shipping companies built docks and warehouses along the waterfront, notably the Hamburg America line in 1863. With this development came jobs, which attracted immigrants. The city's population jumped from 2,200 in 1850 to 20,000 in 1870 and 43,000 in 1890.... Ziegler-McPherson said she learned just how much the city was a German enclave at the turn of the 20th century. A quarter of the city's residents had German roots, earning Hoboken the nickname of 'Little Bremen.'"

- ^ "Factories And Family Favorites In Hoboken". Hoboken, NJ Patch. November 12, 2020. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Dean A. "Early Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1825–1908" Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, University of Nebraska Press, 1997. ISBN 9780803292444. Accessed September 1, 2015.

- ^ Nieves, Evelyn. "Our Towns; In Hoboken, Dreams of Eclipsing the Cooperstown Baseball Legend" Archived November 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, April 3, 1996. Accessed February 1, 2012.

- ^ "The American national game of base ball. Grand match for the championship at the Elysian Fields, Hoboken, N.J." Archived March 31, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress. Accessed September 1, 2015.

- ^ "Colored Folk Shun Hoboken" Archived June 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 29, 1901, via Newspapers.com. Accessed November 13, 2019. "Hoboken, that unique suburb of New York, which has been maligned by many and spoken of derisively from Maine to California, has one claim to distinction: It has only one negro family within its borders. This is all the more remarkable because its neighbor, Jersey City, is full of colored people and outlying sections also have a large quota. ... Of the hundred and one reasons given for the diminutive size of the negro population of Hoboken, probably the correct one is that there is no way for negroes to earn a livelihood in the city.... There seems to be a sort of unwritten law in the town that negroes are to be barred out. This feeling permeates of everything. The Hobokenese are proud of the distinction conferred on their town by the absence of negroes."

- ^ Staff. "Army put in charge of piers in Hoboken; Waterfront Used by Teuton Lines to be a Government Shipping Base. Mayor Reassures Germans May Live in the District So Long as They Are Orderly;-Strict Rules for Saloons. Army put in charge of piers in Hoboken would use German Ships. Marine Experts Want Them to Carry Food to the Allies." Archived July 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, April 20, 1917. Accessed September 13, 2018. "About a quarter of a mile of Hoboken's writer front is technically under martial law today. Military authority superseded civil authority early yesterday morning along that part of the shore line occupied by the big North German Lloyd and Hamburg American Line piers, and armed sentries kept persons on the opposite side of the street from the pier yards."