Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cistern

View on Wikipedia

A cistern (from Middle English cisterne; from Latin cisterna, from cista 'box'; from Ancient Greek κίστη (kístē) 'basket'[1]) is a waterproof receptacle for holding liquids, usually water. Cisterns are often built to catch and store rainwater.[2] To prevent leakage, the interior of the cistern is often lined with hydraulic plaster.[3]

Cisterns are distinguished from wells by their waterproof linings. Modern cisterns range in capacity from a few liters to thousands of cubic meters, effectively forming covered reservoirs.[4]

Origins

[edit]Early domestic and agricultural use

[edit]

Waterproof lime plaster cisterns in the floors of houses are features of Neolithic village sites of the Levant at, for instance, Ramad and Lebwe,[5] and by the late fourth millennium BC, as at Jawa in northeastern Lebanon, cisterns are essential elements of emerging water management techniques in dry-land farming communities.[6]

Early examples of ancient cisterns, found in Israel, include a significant discovery at Tel Hazor, where a large cistern was carved into bedrock beneath a palace dating to the Late Bronze Age. Similar systems were uncovered at Ta'anakh. In the Iron Age, underground water systems were constructed in royal centers and settlements throughout ancient Israel, marking some of the earliest instances of engineering activity in urban planning.[7]

The Ancient Roman impluvium, a standard feature of the domus house, generally had a cistern underneath. The impluvium and associated structures collected, filtered, cooled, and stored the water, and also cooled and ventilated the house.

Castle cisterns

[edit]

In the Middle Ages, cisterns were often constructed in hill castles in Europe, especially where wells could not be dug deeply enough. There were two types: the tank cistern and the filter cistern. Such a filter cistern was built at the Riegersburg in Austrian Styria, where a cistern was hewn out of the lava rock. Rain water passed through a sand filter and collected in the cistern. The filter cleaned the rain water and enriched it with minerals.[citation needed]

Present-day use

[edit]

Cisterns are commonly prevalent in areas where water is scarce, either because it is rare or has been depleted due to heavy use. Historically, the water was used for many purposes including cooking, irrigation, and washing.[8] Present-day cisterns are often used only for irrigation due to concerns over water quality. Cisterns today can also be outfitted with filters or other water purification methods when the water is intended for consumption. It is not uncommon for a cistern to be open in some manner in order to catch rain or to include more elaborate rainwater harvesting systems. It is important in these cases to have a system that does not leave the water open to algae or to mosquitoes, which are attracted to the water and then potentially carry disease to nearby humans.[9]

One particularly unique modern utilization of cisterns is found in San Francisco, which has historically been subject to devastating fires. As a precautionary measure, in 1850, funds were allocated to construct over 100 cisterns across the city to be utilized in case of fire.[10] The city's firefighting network, the Auxiliary Water Supply System (AWSS) maintains a network of 177 independent underground water cisterns, with sizes varying from 75,000 US gallons (280,000 L) to over 200,000 US gallons (760,000 L) depending on location with a total storage capacity of over 11 million U.S. gallons (42 million liters) of water.[11] These cisterns are easily spotted at street level with manholes labeled CISTERN S.F.F.D surrounded by red brick circles or rectangles. The cisterns are completely separate from the rest of the city's water supply, ensuring that in the event of an earthquake, additional backup is available regardless of the condition of the city's mainline water system.[12]

Some cisterns sit on the top of houses or on the ground higher than the house, and supply the running water needs for the house. They are often supplied by wells with electric pumps, or are filled manually or by truck delivery, rather than by rainwater collection. Very common throughout Brazil, for example, they were traditionally made of concrete walls (much like the houses themselves), with a similar concrete top (about 5cm/2 inches thick), with a piece that can be removed for water filling and then reinserted to keep out debris and insects. Modern cisterns are manufactured out of plastic (in Brazil with a characteristic bright blue color, round, in capacities of about 10,000 and 50,000 liters (2641 and 13,208 gallons)). These cisterns differ from water tanks in the sense that they are not entirely enclosed and sealed with one form, rather they have a lid made of the same material as the cistern, which is removable by the user.[citation needed]

To keep a clean water supply, the cistern must be kept clean. It is important to inspect them regularly, keep them well enclosed, and to occasionally empty and clean them with a proper dilution of chlorine and to rinse them well. Well water must be inspected for contaminants coming from the ground source. City water has up to 1ppm (parts per million) chlorine added to the water to keep it clean. If there is any question about the water supply at any point (source to tap), then the cistern water should not be used for drinking or cooking. If it is of acceptable quality and consistency, then it can be used for (1) toilets, and housecleaning; (2) showers and handwashing; (3) washing dishes, with proper sanitation methods,[13] and for the highest quality, (4) cooking and drinking. Water of non-acceptable quality for the aforementioned uses may still be used for irrigation. If it is free of particulates but not low enough in bacteria, then boiling may also be an effective method to prepare the water for drinking.[citation needed]

Many greenhouses rely on a cistern to help meet their water needs, particularly in the United States. Some countries or regions, such as Flanders, Bermuda and the U.S. Virgin Islands, have strict laws requiring that rainwater harvesting systems be built alongside any new construction, and cisterns can be used in these cases. In Bermuda, for example, its familiar white-stepped roofs seen on houses are part of the rainwater collection system, where water is channeled by roof gutters to below-ground cisterns.[14] Other countries, such as Japan, Germany, and Spain, also offer financial incentives or tax credit for installing cisterns.[15] Cisterns may also be used to store water for firefighting in areas where there is an inadequate water supply. The city of San Francisco, notably, maintains fire cisterns under its streets in case the primary water supply is disrupted. In many flat areas, the use of cisterns is encouraged to absorb excess rainwater which otherwise can overload sewage or drainage systems by heavy rains (certainly in urban areas where a lot of ground is surfaced and doesn't let the ground absorb water).[citation needed]

Bathing

[edit]In some southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia showers are traditionally taken by pouring water over one's body with a dipper (this practice comes from before piped water was common). Many bathrooms even in modern houses are constructed with a small cistern to hold water for bathing by this method.[citation needed]

Toilet cisterns

[edit]

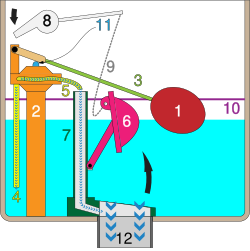

1. float, 2. fill valve, 3. lift arm, 4. tank fill tube, 5. bowl fill tube, 6. flush valve flapper, 7. overflow tube, 8. flush handle, 9. chain, 10. fill line, 11. fill valve shaft, 12. flush tube

The modern toilet utilises a cistern to reserve and hold the correct amount of water required to flush the toilet bowl. In earlier toilets, the cistern was located high above the toilet bowl and connected to it by a long pipe. It was necessary to pull a hanging chain connected to a release valve located inside the cistern in order to flush the toilet. Modern toilets may be close coupled, with the cistern mounted directly on the toilet bowl and no intermediate pipe. In this arrangement, the flush mechanism (lever or push button) is usually mounted on the cistern. Concealed cistern toilets, where the cistern is built into the wall behind the toilet, are also available. A flushing trough is a type of cistern used to serve more than one WC pan at one time. These cisterns are becoming less common, however. The cistern was the genesis of the modern bidet.[citation needed]

At the beginning of the flush cycle, as the water level in the toilet cistern tank drops, the flush valve flapper falls back to the bottom, stopping the main flow to the flush tube. Because the tank water level has yet to reach the fill line, water continues to flow from the tank and bowl fill tubes. When the water again reaches the fill line, the float will release the fill valve shaft and water flow will stop.

One Million Cisterns Program

[edit]In Northeastern Brazil, the One Million Cisterns Program (Programa 1 Milhão de Cisternas or P1MC) has assisted local people with water management. The Brazilian government adopted this new policy of rainwater harvesting in 2013.[16] The Semi-Arid Articulation (ASA) has been providing managerial and technological support to establish cement-layered containers, called cisterns, to harvest and store rainwater for small farm-holders in 34 territories of nine states where ASA operates (Minas Gerais, Bahia, Sergipe, Alagoas, Pernambuco, Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará and Piauí).[17]

The rainwater falling on the rooftops is directed through pipelines or gutters and stored in the cistern.[18] The cistern is covered with a lid to avoid evaporation. Each cistern has a capacity of 16,000 liters. Water collected in it during 3–4 months of the rainy season can sustain the requirement for drinking, cooking, and other basic sanitation purposes for rest of the dry periods. By 2016, 1.2 million rainwater harvesting cisterns were implemented for human consumption alone.[19] After positive results of P1MC, the government introduced another program named "One Land, Two Water Program" (Uma Terra, Duas Águas, P1 + 2), which provides a farmer with another slab cistern to support agricultural production.[20]

Notable examples

[edit]- Basilica Cistern in Istanbul, Turkey

- Aljibe of the Palacio de las Veletas in Cáceres, Spain

- Portuguese cistern (Mazagan) in El Jadida, Morocco

- Cistern in Silves, Portugal

- Matera, southern Italy

- Asa of Judah built a cistern. The prophet Jeremiah was later thrown in it after prophesying the Babylonian invasion

- Cistern in Genesis 37:20, 22

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "cistern". Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary (9th ed.). 1990.

- ^ "Cisterns". National Geographic Society.

- ^ Reich, Ronny; Katzenstein, Hannah (1992). "Glossary of Archaeological Terms". In Kempinski, Aharon; Reich, Ronny (eds.). The Architecture of Ancient Israel. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. p. 312. ISBN 978-965-221-013-5.

- ^ "Cistern Design" (PDF). North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- ^ Robert, Miller (1980). "Water use in Syria and Palestine from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age". World Archaeology. 11 (3): 331–341. doi:10.1080/00438243.1980.9979771. JSTOR 124254.

- ^ Roberts, N. (1977). "Water conservation in ancient Arabia". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 7: 134–46. JSTOR 41223308.

- ^ Shiloh, Yigal (1992). "Underground Water Systems in the Land of Israel in the Iron Age". In Kempinski, Aharon; Reich, Ronny (eds.). The Architecture of Ancient Israel. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. p. 275. ISBN 978-965-221-013-5.

- ^ Mays, Larry; Antoniou, George; Angelakis, Andreas (2013). "History of Water Cisterns: Legacies and Lessons". Water. 5 (4): 1916–1940. Bibcode:2013Water...5.1916M. doi:10.3390/w5041916. hdl:2286/R.I.43114.

- ^ al-Kibsi, Huda (2007-09-29). "Yemen takes another look at cisterns". Yemen Observer. Archived from the original on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ "CISTERNS - FoundSF". www.foundsf.org. Retrieved 2024-08-08.

- ^ King, Jason (2017-12-06). "San Francisco's Hidden Water Tanks". Hidden Hydrology. Retrieved 2024-08-08.

- ^ "The golden legacy of San Francisco's little hydrant that could". FireRescue1. 2021-05-30. Retrieved 2024-08-08.

- ^ "Naturnaher Umgang mit Regenwasser" (PDF). Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt LfU (in German). Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Low, Harry (23 December 2016). "Why houses in Bermuda have white stepped roofs". BBC News. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Scheidewig. "Geld sparen durch Zisternennutzung". Garten-Zisternen (in German). Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- ^ Lindoso, D.P.; Eiró, F.; Bursztyn, M.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Nasuti, S. (2018). "Harvesting water for living with drought: Insights from the Brazilian human coexistence with semi-aridity approach towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals". Sustainability. 10 (3): 622. Bibcode:2018Sust...10..622L. doi:10.3390/su10030622. hdl:2066/183903.

- ^ Pragana, Verônica (2017-12-29). "Acesso à água para produção é ampliado para mais de 6,8 mil famílias do Semiárido". IRPAA - Instituto Regional da Pequena Agropecuária Apropriada.

- ^ Lindoso, D.P.; Eiró, F.; Bursztyn, M.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Nasuti, S. (2018). "Harvesting water for living with drought: Insights from the Brazilian human coexistence with semi-aridity approach towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals". Sustainability. 10 (3): 622. Bibcode:2018Sust...10..622L. doi:10.3390/su10030622. hdl:2066/183903.

- ^ "Programa Cisternas democratiza acesso à água no Semiárido". Government of Brazil. 2016.

- ^ Lindoso, D.P.; Eiró, F.; Bursztyn, M.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Nasuti, S. (2018). "Harvesting water for living with drought: Insights from the Brazilian human coexistence with semi-aridity approach towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals". Sustainability. 10 (3): 622. Bibcode:2018Sust...10..622L. doi:10.3390/su10030622. hdl:2066/183903.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Cisterns at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cisterns at Wikimedia Commons

- Old House Web - Historic Water Conservation.

Cistern

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Ancient and Early Uses

The earliest evidence of cisterns appears in the Neolithic period of the Levant, where communities constructed waterproof storage pits lined with lime plaster to collect rainwater, as seen in settlements like Jericho dating to approximately 7000 BCE.[4] These rudimentary reservoirs, often integrated into house floors, facilitated the transition to settled agriculture by storing seasonal precipitation in regions prone to water shortages, relying on impermeable coatings to minimize evaporation and seepage.[7] In the Bronze Age, Mycenaean Greece demonstrated advanced hydraulic engineering with underground cisterns designed for fortified citadels, such as the one at Mycenae around 1350 BCE, which featured a 99-step staircase leading to a chamber supplied by a natural spring via clay pipe conduits.[8] This system ensured a reliable water supply during sieges or dry periods, exemplifying causal adaptations to topography and vulnerability by channeling subsurface sources into secure, subterranean storage.[9] By the classical Greek era, from roughly 500 BCE, urban cisterns in places like Athens incorporated gravel filtration layers to purify collected rainwater, supporting population growth in water-scarce environments without extensive aqueducts.[10] Roman innovations further scaled these designs, producing vast underground reservoirs—such as those in Fermo, Italy, from the 1st century BCE—capable of holding large volumes for civic distribution, often roofed to prevent contamination and algae growth.[11] In arid Near Eastern contexts, Nabataean engineers from the 3rd century BCE onward hewed rock-cut cisterns in the Negev to harvest flash floods for agriculture, channeling runoff through diversion channels into plastered cavities that sustained oasis farming amid desert conditions.[12] These adaptations prioritized gravitational flow and evaporation-resistant linings, enabling self-sufficient crop irrigation without perennial rivers.[13]Evolution of Waterproofing Plasters and Mortars

The waterproofing of cisterns in the Mediterranean region evolved from simple lime-based coatings to advanced hydraulic mortars, reflecting improvements in material science and engineering across cultures. In the Neolithic Levant, cisterns were lined with basic lime plaster to achieve impermeability, as evidenced by early examples around 7000 BCE in sites like Jericho. This material provided essential waterproofing for rainwater storage in arid conditions.[4] Minoan Crete advanced this technology during the Bronze Age (ca. 3200–1100 BCE), employing hydraulic plaster applied in at least one layer to the bottoms and walls of cisterns to prevent water losses. Examples include cisterns at Myrtos-Pyrgos and Chamaizi, where this plaster enabled reliable storage in surface-fed systems.[14][4] Greek advancements during the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods incorporated pozzolanic additives such as Theran soil (volcanic ash rich in silicon oxide) or crushed ceramics into hydraulic plasters, enhancing setting under wet conditions and improving long-term impermeability in cisterns on islands like Santorini and Delos.[4] Roman engineers built on these Greek influences, refining pozzolanic lime mortars and developing opus signinum—a mixture of lime and crushed terracotta or pottery—for superior waterproofing in large-scale cisterns, baths, and aqueducts. This progression yielded more durable, hydraulic-setting materials capable of withstanding prolonged water exposure and structural demands.[4]Medieval and Defensive Applications

Cisterns played a critical role in medieval European fortifications from the 9th to 15th centuries, designed to secure water supplies during prolonged sieges when external sources could be cut off. These reservoirs typically collected rainwater channeled from castle roofs through gutters into sealed vaults or stone-lined tanks built into towers or courtyards, ensuring a contamination-resistant store independent of wells vulnerable to poisoning by attackers.[15][16] A key Byzantine exemplar is the Basilica Cistern in Constantinople, completed in 532 CE under Emperor Justinian I following the Nika riots to bolster urban water infrastructure. Spanning 143 by 65 meters and supported by 336 columns each 9 meters tall, it held up to 80,000 cubic meters of water sourced from aqueducts, providing strategic reserves for imperial palaces and the city's defense against sieges.[17][18] In the Levant, Crusader and Islamic military architecture from the 11th to 13th centuries incorporated advanced cistern systems adapted to arid conditions, with rainwater harvested from roofs and courtyards into lime-plastered vaults to minimize seepage and bacterial growth. Fortresses such as those in Jordan's mountains featured multiple internal cisterns hewn from rock or built within walls, enabling garrisons to withstand extended blockades without reliance on distant springs.[19][16]Transition to Industrial and Sanitary Roles

In 1596, Sir John Harington, godson of Queen Elizabeth I, invented the first modern flush toilet, known as the water closet, which featured an elevated cistern supplying water via gravity to flush waste through a valve and downpipe.[20] This design aimed to improve hygiene by rapidly removing excreta with water, though adoption remained limited due to unreliable water sources and social resistance.[21] Harington detailed the mechanism in his satirical treatise A New Discourse of a Stale Subject, called the Metamorphosis of Ajax, and installed a prototype at Richmond Palace for the queen, marking an early conceptual shift toward cistern-dependent sanitary appliances.[22] The 19th century accelerated cistern integration into urban plumbing amid rapid industrialization and population growth, as cities like London expanded sewer networks and indoor sanitation to combat waterborne diseases. Cholera epidemics, including the 1831–1832 outbreak that killed over 6,000 in London alone and the 1848–1849 wave claiming 52,000 British lives, exposed vulnerabilities in contaminated municipal supplies, prompting reliance on supplemental cisterns for gravity-fed flushing in private homes.[23][24] Innovations such as siphon valves and high-level cisterns enabled consistent water delivery for waste removal, reducing manual cleaning and bacterial persistence, though cisterns themselves risked stagnation if not maintained.[25] Material advancements supported this evolution, with cistern components shifting from traditional brick or wood to lead pipes for distribution—first documented in American systems around 1800—and later cast iron for structural durability by the mid-1800s, allowing higher pressures and corrosion resistance in plumbed fixtures.[26][27] These changes, driven by engineering needs rather than isolated public health campaigns, facilitated cisterns' role in early sanitary infrastructure until pressurized municipal water partially supplanted them post-1850s.[28]Design and Technical Features

Materials and Construction Methods

Ancient cisterns were typically constructed from locally available stone or rock, with interiors carved directly from bedrock or built using dressed stone blocks and bricks joined by lime mortar to achieve impermeability and structural stability against seismic activity.[7][29] In Roman engineering, opus caementicium—a hydraulic lime mortar mixed with aggregate like small stones—formed durable, watertight linings that resisted biological degradation from algae or bacterial growth by minimizing porosity.[29] Sealing methods employed a range of plaster types that evolved across Mediterranean civilizations to enhance impermeability and durability. Early examples in the Neolithic Levant used simple waterproof lime plasters. Minoan Crete (Bronze Age) applied hydraulic plasters to cistern walls and floors for effective water retention. Hellenistic cisterns in the Aegean incorporated pozzolanic additives, such as Theran soil rich in silica, to improve hydraulic properties. Roman engineers advanced these techniques with opus signinum, a waterproof mortar combining lime, pozzolana (volcanic ash), and crushed ceramics or bricks, widely adopted for cistern linings due to its superior resistance to water seepage and long-term durability. These plasters were applied in layers to walls and floors, creating barriers against leakage while providing flexibility to accommodate ground shifts without cracking.[4][30] Construction involved excavating pits to stable bedrock depths, often 5-10 meters, followed by wall erection with inward batter for load distribution and floor paving with sloped surfaces—typically 1-2% gradient—to facilitate self-draining and periodic cleaning via gravity flow, reducing sediment accumulation and microbial risks.[31] Ventilation shafts, integrated during building, prevented methane or hydrogen sulfide buildup from organic decay, ensuring safe access for maintenance as evidenced in archaeological sites like Mycenaean cisterns dating to the 13th century BCE.[31] In modern practice, reinforced concrete—poured in situ or precast—dominates for underground cisterns due to its compressive strength exceeding 4,000 psi per ASTM C-913 standards, providing seismic resistance through rebar grids and resistance to corrosion when sealed.[32] Polyethylene and fiberglass-reinforced polyester tanks offer superior impermeability and non-porous surfaces that inhibit bacterial adhesion, with lifespans up to 50 years without degradation from UV or chemical exposure.[33][34] Contemporary methods prioritize site assessment for soil stability, followed by excavation with shoring, foundation compaction to prevent settling, and integration of overflow pipes sloped at minimum 2% to avert backups.[35] Interior coatings like cement-based sealants (e.g., Thoroseal) enhance smoothness for self-cleaning flows, while screened vents maintain air exchange without contaminant ingress, aligning with plumbing codes for potable storage.[31][31]Types, Capacities, and Engineering Principles

Cisterns are classified primarily by placement as underground or above-ground variants, each suited to specific hydraulic and site conditions. Underground cisterns, embedded in the earth, maintain consistent water temperatures year-round due to thermal inertia of surrounding soil, typically ranging from cooler summer storage to freeze protection in cold climates, though they demand robust engineering to counter lateral earth pressures and groundwater buoyancy.[31] Above-ground cisterns, elevated or surface-mounted, enable simpler gravity-feed distribution via elevated positioning but expose water to diurnal temperature swings that can promote algal growth or freezing risks without insulation.[36] [37] Capacities span orders of magnitude, from compact units holding tens of liters in gravity toilet flush tanks to expansive reservoirs storing thousands of cubic meters for community-scale rainwater harvesting. Volume is calculated using geometric formulas tailored to shape: for rectangular cisterns, V = length × width × depth in cubic meters; cylindrical forms use V = π r² h, where r is radius and h is height.[38] Sizing for rainwater systems incorporates yield estimates via V = catchment area × rainfall depth × runoff coefficient, with coefficients of 0.8–0.9 for impervious roofs; for example, 1 inch (25.4 mm) of rain on 1000 square feet (93 m²) yields approximately 600 U.S. gallons (2270 liters), guiding minimum storage to capture peak events without overflow.[39] [40] Core engineering principles prioritize pressure equilibrium and sedimentation control for operational reliability. Cisterns function at atmospheric pressure atop the water column, yielding hydrostatic delivery pressures up to ρgh (water density ρ ≈ 1000 kg/m³, g = 9.81 m/s², h = effective head), sufficient for low-pressure gravity systems but necessitating pumps for higher demands. Pre-storage filtration via coarse screens or diverters at inlets minimizes sedimentation, which otherwise reduces usable volume through settled particulates; initial runoff diversion captures the first 0.1–0.2 mm of rainfall laden with roof contaminants, preserving clarity.[31] Specialized variants, such as Venetian well-head systems, integrate multi-layered subsurface filtration—alternating gravel, sand, and clay beds beneath ornate surface heads—to percolate rainwater into sealed underground vaults, leveraging Darcy's law for controlled infiltration rates that historically sustained Venice's freshwater needs amid saline surroundings without mechanical aids.[41] These designs emphasize load-bearing arches or vaults to distribute overburden while ensuring impermeability against infiltration, balancing structural stability with hydraulic throughput.[42]Primary Functions and Traditional Applications

Domestic and Agricultural Water Storage

Cisterns have long served domestic water storage needs in non-urban settings by capturing rooftop runoff for household consumption and non-potable uses such as laundry and gardening. Systems typically involve gutters directing precipitation from roofs into underground or above-ground tanks, with storage capacities ranging from 2,500 to 5,000 gallons (approximately 9,500 to 19,000 liters) for medium-sized households to ensure supply during dry periods.[43] Yield from such systems is calculated as roof area multiplied by precipitation depth times a conversion factor, where 1 inch of rain on 1,000 square feet of roof yields about 623 gallons, though actual collection efficiency is often 75% after losses from evaporation and initial runoff.[44][45] In regions with variable rainfall, cistern yields exhibit significant fluctuations tied directly to annual precipitation patterns, necessitating oversized storage to bridge gaps between wet and dry seasons; for instance, a three-month buffer is recommended to avoid reliance on external sources.[31] This approach promotes self-sufficiency but demands regular maintenance to prevent sedimentation and contamination from first-flush pollutants. For agricultural applications, cisterns scale up to support irrigation in arid and semi-arid drylands, storing harvested rainwater or supplemental sources for crop watering during deficits. Traditional systems in these environments, such as small farm reservoirs, range from 1,000 to 500,000 cubic meters in capacity, enabling flood channeling for later distribution via gravity-fed channels.[46] In ancient Rome, rural cisterns augmented aqueduct supplies for villa estates and gardens, buffering seasonal shortages to sustain viticulture and horticulture amid inconsistent local rainfall.[47][48] Modern equivalents in drylands similarly prioritize episodic flood capture, with outputs varying causally by catchment size and storm intensity rather than uniform distribution.[49]Sanitation, Bathing, and Early Plumbing Integration

Cisterns played a pivotal role in early sanitation systems through their integration with gravity-fed flushing mechanisms in toilets, first developed in the late 16th century. Sir John Harington invented the first modern flush toilet in 1596, featuring a raised cistern that released approximately 7.5 gallons of water via a valve to displace waste through gravitational force, marking a shift from dry privies to water-based hygiene.[50][51] These early designs relied on simple mechanical valves, such as ball cocks for refilling and flush levers to open discharge ports, enabling periodic cleaning of waste without manual handling, though adoption was limited until 19th-century improvements in plumbing infrastructure.[52] By the 20th century, toilet cisterns evolved to address water efficiency amid growing urban demands and conservation efforts. Regulations in the 1990s mandated low-flow models using no more than 1.6 gallons per flush, compared to prior standards of 3.5 to 5 gallons, achieved through refined siphon valves and dual-flush options that optimized gravity displacement while reducing overall consumption.[53] This progression minimized stagnation periods in cisterns by promoting faster turnover, though empirical observations of bacterial proliferation in static water—evident from historical records of foul odors and disease outbreaks linked to poorly maintained reservoirs—underscored ongoing hygiene challenges.[54] In bathing contexts, cisterns supplied reservoirs for ritual and therapeutic immersion, particularly in Roman and Ottoman systems. Roman public baths drew from large-scale cisterns fed by aqueducts, storing millions of gallons to fill heated pools (caldaria) and cold plunge basins (frigidaria), where water circulation via lead pipes mitigated some stagnation risks despite the volume's tendency toward microbial growth without modern filtration.[55][56] Ottoman hammams, building on this legacy, incorporated cistern-stored water for ghusl rituals—full-body ablutions essential for Islamic prayer purity—often heated via underfloor hypocausts, with empirical preferences for frequently renewed supplies to avoid the health hazards of prolonged stasis, as noted in period accounts of water quality degradation.[57] These integrations highlighted cisterns' utility in hygiene but revealed causal vulnerabilities: stagnant conditions fostered pathogens, prompting ancient practices like skimming debris and favoring flowing sources, which prefigured 20th-century chlorination adoption for disinfection, first applied municipally in 1908 to combat similar contamination vectors.[58][59]Contemporary Applications

Rainwater Harvesting and Sustainable Water Management

Rainwater harvesting systems employing cisterns capture roof runoff for storage and non-potable uses such as irrigation, toilet flushing, and laundry, promoting independence from municipal supplies in off-grid or strained urban settings. These systems typically achieve collection efficiencies of 80-95% from impervious roof surfaces, with asphalt shingles yielding approximately 85% and enameled metal roofs exceeding 95%, accounting for initial first-flush diversion and minor evaporation losses.[60] Cistern sizing relies on empirical formulas integrating local precipitation data, such as potential volume = annual rainfall (mm) × catchment area (m²) × runoff coefficient (typically 0.8-0.9 for roofs), ensuring adequate storage to bridge dry periods based on demand profiles.[61][62] In suburban applications, cisterns enable households to offset 20-50% of non-potable water needs, reducing reliance on centralized utilities vulnerable to disruptions from droughts, infrastructure failures, or contamination events, as observed in regions with recurrent supply strains.[63] Yield efficiency varies by climate, with arid zones requiring larger capacities to maximize reliability; for instance, off-grid installations in water-limited areas utilize 4,000-6,000 gallon cisterns to sustain year-round demands from seasonal harvests.[64] This approach enhances resource autonomy, particularly where municipal systems face capacity limits, allowing users to harvest and store volumes equivalent to thousands of gallons annually from typical residential roofs under moderate rainfall regimes.[65] Economic analyses indicate positive returns on investment in water-scarce locales like the U.S. Southwest, where high municipal rates amplify savings from displaced usage; payback periods shorten with elevated water costs and larger catchment areas, often realizing net benefits through reduced bills despite upfront installation expenses of $5,000-15,000 for mid-sized systems.[66][67] In comparable arid environments, such as Australia's outback, similar setups yield verifiable cost efficiencies by minimizing pumping and treatment dependencies, with harvested water substituting pricier alternatives during scarcity peaks.[68] Overall, these cistern-based strategies prioritize causal yield optimization over expansive infrastructure, delivering scalable independence grounded in site-specific hydrology and usage patterns.

![Aljibe of the Palacio de las Veletas [es], Cáceres, Spain](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Palacio_de_las_Veletas%2C_aljibe%2C_C%C3%A1ceres.JPG/120px-Palacio_de_las_Veletas%2C_aljibe%2C_C%C3%A1ceres.JPG)