Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

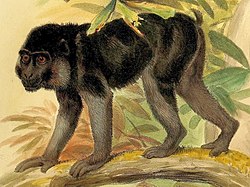

Macaque

View on Wikipedia

| Macaques[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bonnet macaque in Manegaon, Maharashtra, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Subfamily: | Cercopithecinae |

| Tribe: | Papionini |

| Genus: | Macaca Lacépède, 1799 |

| Type species | |

| Simia inuus[1] | |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

The macaques (/məˈkɑːk, -ˈkæk/)[2] constitute a genus (Macaca) of gregarious Old World monkeys of the subfamily Cercopithecinae. The 23 species of macaques inhabit ranges throughout Asia, North Africa, and Europe (in Gibraltar). Macaques are principally frugivorous (preferring fruit), although their diet also includes seeds, leaves, flowers, and tree bark. Some species such as the long-tailed macaque (M. fascicularis; also called the crab-eating macaque) will supplement their diets with small amounts of meat from shellfish, insects, and small mammals. On average, a southern pig-tailed macaque (M. nemestrina) in Malaysia eats about 70 large rats each year.[3][4] All macaque social groups are arranged around dominant matriarchs.[5]

Macaques are found in a variety of habitats throughout the Asian continent and are highly adaptable. Certain species are synanthropic, having learned to live alongside humans, but they have become problematic in urban areas in Southeast Asia and are not suitable to live with, as they can carry transmittable diseases.

Most macaque species are listed as vulnerable to critically endangered on the International Union of the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Description

[edit]Aside from humans (genus Homo), the macaques are the most widespread primate genus, ranging from Japan to the Indian subcontinent, and in the case of the Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus), to North Africa and Southern Europe. Twenty-three macaque species are currently recognized. Macaques are robust primates whose arms and legs are about the same in length. The fur of these animals is typically varying shades of brown or black and their muzzles are rounded in profile with nostrils on the upper surface. The tail varies among each species, which can be long, moderate, short or totally absent.[6] Although several species lack tails, and their common names refer to them as apes, these are true monkeys, with no greater relationship to the true apes than any other Old World monkeys. Instead, this comes from an earlier definition of 'ape' that included primates generally.[7]

In some species, skin folds join the second through fifth toes, almost reaching the first metatarsal joint.[8] The monkey's size differs depending on sex and species. Males from all species can range from 41 to 70 cm (16 to 27.5 in) in head and body length, and in weight from 5.5 to 18 kg (12 to 40 lb).[6] Females can range from a weight of 2.4 to 13 kg (5.3 to 28.7 lb). These primates live in troops that vary in size, where males dominate, however the order of dominance frequently shifts. Female dominance lasts longer and depends upon their genealogical position. Macaques are able to swim and spend most of their time on the ground and spend some time in trees. They have large pouches in their cheeks where they carry extra food. They are considered highly intelligent and are often used in the medical field for experimentation due to their remarkable similarity to humans in emotional and cognitive development. Extensive experimentation has led to the long-tailed macaque being listed as endangered.[6]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]Macaques are highly adaptable to different habitats and climates and can tolerate a wide fluctuation of temperatures and live in varying landscape settings. They easily adapt to human-built environments and can survive well in urban settings if they are able to obtain food. They can also survive in completely natural settings absent of humans.

The ecological and geographic ranges of the macaque are the widest of any non-human primate. Their habitats include the tropical rainforests of Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, India, arid mountains of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and temperate mountains in Algeria, Japan, China, Morocco, and Nepal. Some species also inhabit villages and towns in cities in Asia.[9] There is also an introduced population of rhesus macaques in the US state of Florida consisting, essentially, of monkeys abandoned when a failed boat ride-safari was shut down in the mid-20th century.

A probable Early Pliocene macaque molar from the Red Crag Formation (Waldringfield, United Kingdom), represents one of the oldest and northernmost records of the genus in Europe reported to date.[10]

Ecology and behavior

[edit]Diet

[edit]Macaques are mainly frugivorous, although some species have been observed feeding on insects. In natural habitats, they have been observed to consume certain parts of over one hundred species of plants including the buds, fruit, young leaves, bark, roots, and flowers. When macaques live amongst people, they raid agricultural crops such as wheat, rice, or sugarcane; and garden crops like tomatoes, bananas, melons, mangos, or papayas.[11] In human settings, they also rely heavily on direct handouts from people. This includes peanuts, rice, legumes, or even prepared food.

Group structure

[edit]Macaques live in established social groups that can range from a few individuals to several hundred, as they are social animals. A typical social group possess between 20 and 50 individuals of all ages and of both sexes. The typical composition consists of 15% adult males, 35% adult females, 20% infants, and 30% juveniles, though there exists variation in structure and size of groups across populations.[citation needed]

Macaques have a very intricate social structure and hierarchy, with different classifications of despotism depending on species.[13] If a macaque of a lower level in the social chain has eaten berries and none are left for a higher-ranking macaque, then the one higher in status can, within this social organization, remove the berries from the other monkey's mouth.[14]

Reproduction and mortality

[edit]The reproductive potential of each species differs. Populations of the rhesus macaque can grow at rates of 10% to 15% per year if the environmental conditions are favorable. However, some forest-dwelling species are endangered with much lower reproductive rates.[citation needed] After one year of age, macaques move from being dependent on their mother during infancy, to the juvenile stage, where they begin to associate more with other juveniles through rough tumble and playing activities. They sexually mature between three and five years of age. Females will usually stay with the social group in which they were born; however, young adult males tend to disperse and attempt to enter other social groups. Not all males succeed in joining other groups and may become solitary, attempting to join other social groups for many years.[citation needed] Macaques have a typical lifespan of 20 to 30 years.

As invasive species

[edit]

Certain species under the genus Macaca have been transplanted to different parts of the world, where they become invasive, while others remain threatened. The long-tailed macaque (M. fascicularis) is listed as an invasive alien species in Mauritius, along with the rhesus macaques (M. mulatta) in Florida.[15] Despite this, the former is listed as endangered.

The long-tailed macaque causes severe damage to parts of its range where it has been introduced because the populations grow unchecked due to a lack of predators.[16] On the island of Mauritius, they have created serious conservation concerns for other endemic species. They consume seeds of native plants and aid in the spread of exotic weeds throughout the forests. This changes the composition of the habitats and allows them to be rapidly overrun by invasive plants.

Long-tailed macaques are also responsible for the near extinction of several bird species on Mauritius by destroying the nests of the birds and eating the eggs of critically endangered species, such as the pink pigeon and Mauritian green parrot.[17] They have been known to eat crops from human farms and gardens, sparking human-wildlife conflicts.

In Florida, a group of rhesus macaques inhabit Silver Springs State Park. Humans often feed them, which may alter their movement and keep them close to the river on weekends where high human traffic is present.[15] The monkeys can become aggressive toward humans, largely due to human ignorance of macaque behavior. They carry potentially fatal human diseases, including the herpes B virus.[18]

Relations with humans

[edit]Several species of macaque are used extensively in animal testing, particularly in the neuroscience of visual perception and the visual system.

Nearly all (73–100%) captive rhesus macaques are carriers of the herpes B virus. This virus is harmless to macaques, but infections of humans, while rare, are potentially fatal, a risk that makes macaques unsuitable as pets.[19]

Urban performing macaques also carried simian foamy virus, suggesting they could be involved in the species-to-species jump of similar retroviruses to humans.[20]

Population control

[edit]Management techniques have historically been controversial, and public disapproval can hinder control efforts. Previously, efforts to remove macaque individuals were met with public resistance.[15] One management strategy that is currently being explored is that of sterilization. Natural resource managers are being educated by scientific studies in the proposed strategy. Effectiveness of this strategy is estimated to succeed in keeping populations in check. For example, if 80% of females are sterilized every five years, or 50% every two years, it could effectively reduce the population.[15] Other control strategies include planting specific trees to provide protection to native birds from macaque predation, live trapping, and the vaccine porcine zona pellucida (PZP), which causes infertility in females.[17]

Cloning

[edit]In January 2018, scientists in China reported in the journal Cell the first creation of two crab-eating macaque clones, named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, using somatic cell nuclear transfer – the same method that produced Dolly the sheep.[21][22][23][24]

Species

[edit]| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arunachal macaque | M. munzala Sinha, Datta, Madhusudan, Mishra, 2005 |

Eastern Himalayas

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 9–20 cm (4–8 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[26] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

EN

|

| Assam macaque | M. assamensis (McClelland, 1840) Two subspecies

|

Southeastern Asia

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 9–20 cm (4–8 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[27] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

NT

|

| Barbary macaque | M. sylvanus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Northwestern Africa

|

Size: 45–60 cm (18–24 in) long, plus 1–2 cm (0–1 in) tail[28] Habitat: Forest, shrubland, grassland, rocky areas, and caves[29] Diet: Plants, caterpillars, fruit, seeds, roots, and fungi[28] |

EN

|

| Bonnet macaque | M. radiata (Geoffroy, 1812) Two subspecies

|

Southern India

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 9–20 cm (4–8 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest, savanna, and shrubland[30] Diet: Fruit, foliage, and insects, as well as bird eggs and lizards[31] |

VU

|

| Booted macaque | M. ochreata (Ogilby, 1841) |

Island of Sulawesi in Indonesia

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 1–15 cm (0–6 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest and savanna[32] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

VU

|

| Celebes crested macaque | M. nigra (Desmarest, 1822) |

Island of Sulawesi

|

Size: 44–57 cm (17–22 in) long, plus about 2 cm (1 in) tail[33] Habitat: Forest[34] Diet: Fruit, as well as insects, shoots, leaves, and stems[33] |

CR

|

| Crab-eating macaque | M. fascicularis (Raffles, 1821) Ten subspecies

|

Southeastern Asia

|

Size: 40–47 cm (16–19 in) long, plus 50–60 cm (20–24 in) tail Habitat: Forest, intertidal marine, caves, inland wetlands, grassland, shrubland, and savanna[35] Diet: Fruit, crabs, flowers, insects, leaves, fungi, grasses, and clay[36] |

EN

|

| Formosan rock macaque | M. cyclopis Swinhoe, 1862 |

Taiwan

|

Size: 36–45 cm (14–18 in) long, plus 26–46 cm (10–18 in) tail[37] Habitat: Forest[38] Diet: Fruit, leaves, berries, seeds, insects, and small vertebrates, buds, and shoots[37] |

LC

|

| Gorontalo macaque | M. nigrescens (Temminck, 1849) |

Island of Sulawesi

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 1–15 cm (0–6 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[39] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

VU

|

| Heck's macaque | M. hecki (Matschie, 1901) |

Island of Sulawesi

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 1–15 cm (0–6 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest and grassland[40] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

VU

|

| Japanese macaque | M. fuscata (Blyth, 1875) Two subspecies

|

Japan

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 1–15 cm (0–6 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[41] Diet: Fruit, seeds, flowers, nectar, leaves, and fungi[42] |

LC

|

| Lion-tailed macaque | M. silenus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Southwestern India

|

Size: 40–61 cm (16–24 in) long, plus 24–38 cm (9–15 in) tail[43] Habitat: Forest[44] Diet: Fruit, as well as leaves, stems, flowers, buds, fungi, insects, lizards, tree frogs, and small mammals[43] |

EN

|

| Moor macaque | M. maura (Schinz, 1825) |

Island of Sulawesi

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 1–15 cm (0–6 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest and grassland[45] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

EN

|

| Muna-Buton macaque

|

M. brunnescens (Matschie, 1901) |

Island of Sulawesi in Indonesia

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 1–15 cm (0–6 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[46] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

VU

|

| Northern pig-tailed macaque | M. leonina (Blyth, 1863) |

Southeastern Asia

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 9–20 cm (4–8 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[47] Diet: Leaves, seeds, stems, roots, flowers, bamboo shoots, rice, gums, insects, larvae, termite eggs and spiders[47] |

VU

|

| Pagai Island macaque | M. pagensis (G. S. Miller, 1903) |

Mentawai Islands in Indonesia

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 9–20 cm (4–8 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[48] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

CR

|

| Rhesus macaque | M. mulatta (Zimmermann, 1790) |

Southern and southeastern Asia

|

Size: 45–64 cm (18–25 in) long, plus 19–32 cm (7–13 in) tail[49] Habitat: Forest, savanna, and shrubland[50] Diet: Fish, crabs, shellfish, bird eggs, honeycombs, crayfish, crabs, spiders, plants, gums and pith[50] |

LC

|

| Siberut macaque

|

M. siberu Fuentes, 1995 |

Siberut island in Indonesia

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 9–20 cm (4–8 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[51] Diet: Fruit, as well as mushrooms, leaves, crabs, crayfish, pith, sap, shoots and flowers[51] |

EN

|

| Southern pig-tailed macaque | M. nemestrina (Linnaeus, 1766) |

Southeastern Asia

|

Size: 46–57 cm (18–22 in) long, plus 13–26 cm (5–10 in) tail[52] Habitat: Forest and shrubland[53] Diet: Fruit, insects, seeds, leaves, dirt, and fungus, as well as birds, termite eggs and larvae, and river crabs[52] |

EN

|

| Stump-tailed macaque | M. arctoides (I. Geoffroy, 1831) |

Southeastern Asia

|

Size: 48–65 cm (19–26 in) long, plus 3–7 cm (1–3 in) tail[54] Habitat: Forest[55] Diet: Fruit, seeds, flowers, roots, leaves, frogs, crabs, birds, and bird eggs[54] |

VU

|

| Tibetan macaque | M. thibetana (A. Milne-Edwards, 1870) Four subspecies

|

East China

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 1–15 cm (0–6 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest and caves[56] Diet: Fruit, as well as flowers, berries, seeds, leaves, stems, stalks, and invertebrates[56] |

NT

|

| Tonkean macaque | M. tonkeana (von Meyer, 1899) |

Island of Sulawesi

|

Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 1–15 cm (0–6 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[57] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

VU

|

| Toque macaque | M. sinica (Linnaeus, 1771) Three subspecies

|

Sri Lanka

|

Size: 36–53 cm (14–21 in) long, plus at least 36–53 cm (14–21 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[58] Diet: Fruit as well as tree flowers, buds, and leaves[59] |

EN

|

| White-cheeked macaque | M. leucogenys Li, Zhao, Fan, 2015 |

Northeastern India | Size: 36–77 cm (14–30 in) long, plus about 9–20 cm (4–8 in) tail[25] Habitat: Forest[60] Diet: Fruit, leaves, grains, buds, seeds, flowers, and bark, as well as insects and small invertebrates[25] |

EN

|

Prehistoric (fossil) species

[edit]- M. anderssoni Schlosser, 1924

- M. jiangchuanensis Pan et al., 1992[61]

- M. libyca Stromer, 1920

- M. majori Schaub & Azzaroli in Comaschi Caria, 1969 (sometimes included in M. sylvanus)

- M. florentina Cocchi, 1872

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 161–165. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "macaque". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021.

- ^ Keach, Sean (October 22, 2019). "Rat-eating monkeys in Malaysia stun scientists". The Sun.

- ^ Guy, Jack (October 22, 2019). "Rat-eating macaques could boost palm oil sustainability in Malaysia". CNN.

- ^ Fleagle, John G. (8 March 2013). Primate Adaptation and Evolution. Academic. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-12-378633-3.

- ^ a b c "macaque | Classification & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ^ "ape, n." OED Online. Oxford University Press, March 2017. Web. 16 April 2017.

- ^ Ankel-Simons, Friderun (2000). "Hands and Feet". Primate anatomy: an introduction. Academic Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-12-058670-7.

- ^ Knight, John (August 1999). "Monkeys on the Move: The Natural Symbolism of People-Macaque Conflict in Japan". The Journal of Asian Studies. 58 (3): 622–647. doi:10.2307/2659114. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2659114. S2CID 143569917.

- ^ Pickford, M.; Gommery, D.; Ingicco, T. (2023). "Macaque molar from the Red Crag Formation, Waldringfield, England". Fossil Imprint. 79 (1): 26–36. doi:10.37520/fi.2023.003. S2CID 265089167.

- ^ "Primate Factsheets: Long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) Conservation". pin.primate.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ^ Boussaoud, D.; Tanné-Gariépy, J.; Wannier, T.; Rouiller, E. M. (2005). "Callosal connections of dorsal versus ventral premotor areas in the macaque monkey: A multiple retrograde tracing study". BMC Neuroscience. 6: 67. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-6-67. PMC 1314896. PMID 16309550.

- ^ Matsumura, S (1999). "The evolution of "egalitarian" and "despotic" social systems among macaques". Primates. 40 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1007/BF02557699. PMID 23179529. S2CID 23652944 – via SpringerLink Journals.

- ^ David Attenborough (2003). The Life of Mammals. BBC Video.

- ^ a b c d "Mapping Macaques: Studying Florida's Non-Native Primates". UF/IFAS Wildlife Ecology and Conservation Department. 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ^ "Primate Factsheets: Long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) Conservation". pin.primate.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ^ a b "GISD". iucngisd.org. Upane. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ^ Ostrowski, Stephanie (March 1998). "B-virus from Pet Macaque Monkeys: An Emerging Threat in the United States?". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 4 (1): 117–21. doi:10.3201/eid0401.980117. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2627675. PMID 9452406.

- ^ Ostrowski, Stephanie R.; et al. (1998). "B-virus from Pet Macaque Monkeys: an Emerging Threat in the United States?". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 4 (1). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): 117–121. doi:10.3201/eid0401.980117. PMC 2627675. PMID 9452406.

- ^ "News | University of Toronto". www.utoronto.ca. Archived from the original on March 22, 2006. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ Liu, Zhen; et al. (24 January 2018). "Cloning of Macaque Monkeys by Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer". Cell. 172 (4): 881–887.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.020. PMID 29395327.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (24 January 2018). "These monkey twins are the first primate clones made by the method that developed Dolly". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aat1066. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (24 January 2018). "First monkey clones created in Chinese laboratory". BBC News. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Scientists Successfully Clone Monkeys; Are Humans Up Next?". The New York Times. Associated Press. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Nowak 1999, pp. 140, 142

- ^ a b Kumar, A.; Sinha, A.; Kumar, S. (2020). "Macaca munzala". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T136569A17948833. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T136569A17948833.en.

- ^ a b Boonratana, R.; Chalise, M.; Htun, S.; Timmins, R. J. (2020). "Macaca assamensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12549A17950189. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12549A17950189.en.

- ^ a b Jinn, Judy (2011). "Macaca sylvanus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Wallis, J.; Benrabah, M. E.; Pilot, M.; Majolo, B.; Waters, S. (2020). "Macaca sylvanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12561A50043570. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12561A50043570.en.

- ^ a b Singh, M.; Kumara, H. N.; Kumar, A. (2020). "Macaca radiata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12558A17951596. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12558A17951596.en.

- ^ Brown, Monica (2008). "Macaca radiata". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Riley, E.; Lee, R.; Sangermano, F.; Cannon, C.; Shekelle, M. (2021). "Macaca ochreata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T39793A17985872. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T39793A17985872.en.

- ^ a b Bichell, Rae Ellen (2011). "Macaca nigra". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Lee, R.; Riley, E.; Sangermano, F.; Cannon, C.; Shekelle, M. (2020). "Macaca nigra". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12556A17950422. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T12556A17950422.en.

- ^ a b Hansen, M. F.; Ang, A.; Trinh, T. T. H.; Sy, E.; Paramasivam, S.; Ahmed, T.; Dimalibot, J.; Jones-Engel, L.; Ruppert, N.; Griffioen, C.; Lwin, N.; Phiapalath, P.; Gray, R.; Kite, S.; Doak, N.; Nijman, V.; Fuentes, A.; Gumert, M. D. (2022) [amended version of 2022 assessment]. "Macaca fascicularis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022 e.T12551A221666136. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T12551A221666136.en.

- ^ Bonadio, Christopher (2000). "Macaca fascicularis". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Chiu, Crystal (2001). "Macaca cyclopis". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 30, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Wu, H.; Long, Y. (2020). "Macaca cyclopis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12550A17949875. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12550A17949875.en.

- ^ a b Lee, R.; Riley, E.; Sangermano, F.; Cannon, C.; Shekelle, M. (2020). "Macaca nigrescens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12568A17948400. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T12568A17948400.en.

- ^ a b Lee, R.; Riley, E.; Sangermano, F.; Cannon, C.; Shekelle, M. (2020). "Macaca hecki". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12570A17948969. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T12570A17948969.en.

- ^ a b Watanabe, K.; Tokita, K. (2021) [errata version of 2020 assessment]. "Macaca fuscata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12552A195347803. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12552A195347803.en.

- ^ hardman, brandon (2011). "Macaca fuscata". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Strawder, Nicole (2001). "Macaca silenus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Singh, M.; Kumar, A.; Kumara, H. N. (2020). "Macaca silenus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12559A17951402. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12559A17951402.en.

- ^ a b Riley, E.; Lee, R.; Sangermano, F.; Cannon, C.; Shekelle, M. (2021) [errata version of 2020 assessment]. "Macaca maura". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12553A197831931. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T12553A197831931.en.

- ^ a b Lee, R.; Riley, E.; Sangermano, F.; Cannon, C.; Shekelle, M. (2021). "Macaca brunnescens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T12569A17985924. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T12569A17985924.en.

- ^ a b c Boonratana, R.; Chetry, D.; Yongcheng, L.; Jiang, X.-L.; Htun, S.; Timmins, R. J. (2022) [amended version of 2020 assessment]. "Macaca leonina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022 e.T39792A217754289. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T39792A217754289.en.

- ^ a b Setiawan, A.; Mittermeier, R. A.; Whittaker, D. (2020). "Macaca pagensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T39794A17949995. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T39794A17949995.en.

- ^ Seinfeld, Joshua (2000). "Macaca mulatta". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c Singh, M.; Kumar, A.; Kumara, H. N. (2020). "Macaca mulatta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12554A17950825. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12554A17950825.en.

- ^ a b c Traeholt, C.; Setiawan, A.; Quinten, M; Cheyne, S. M.; Whittaker, D.; Mittermeier, R. A. (2020). "Macaca siberu". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T39795A17949710. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T39795A17949710.en.

- ^ a b Ayers, Kayla; Vanderpoel, Candace (2009). "Macaca nemestrina". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Ruppert, N.; Holzner, A.; Hansen, M. F.; Ang, A.; Jones-Engel, L. (2022). "Macaca nemestrina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022 e.T12555A215350982. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T12555A215350982.en.

- ^ a b Erfurth, Charlotte (2008). "Macaca arctoides". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Chetry, D.; Boonratana, R.; Das, J.; Long, Y.; Htun, S.; Timmins, R. J. (2020). "Macaca arctoides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12548A185202632. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T12548A185202632.en.

- ^ a b c Yongcheng, L.; Richardson, M. (2020). "Macaca thibetana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12562A17948236. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12562A17948236.en.

- ^ a b Riley, E.; Lee, R.; Sangermano, F.; Cannon, C.; Shekelle, M. (2020). "Macaca tonkeana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12563A17947990. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T12563A17947990.en.

- ^ a b Dittus, W.; Watson, A. C. (2020). "Macaca sinica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T12560A17951229. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12560A17951229.en.

- ^ Kanelos, Matthew (2009). "Macaca sinica". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Fan, P. F.; Ma, C. (2022). "Macaca leucogenys". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022 e.T205889816A205890248. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T205889816A205890248.en.

- ^ Hartwig, Walter Carl (2002). The primate fossil record. Cambridge University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-521-66315-1.

Sources

[edit]- Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's Primates of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6251-9.

_Photograph_By_Shantanu_Kuveskar.jpg/250px-Bonnet_macaque_(Macaca_radiata)_Photograph_By_Shantanu_Kuveskar.jpg)

_Photograph_By_Shantanu_Kuveskar.jpg)