Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Operation Albion

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (June 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Operation Albion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I | |||||||

Operation Albion amphibious operations 12–20 October 1917 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 battlecruiser 10 dreadnought battleships 9 light cruisers 1 mine cruiser 50 torpedo boats 6 U-boats 19 transports 6 airships 102 combat aircraft 24,500 soldiers 8,500 horses 2,400 vehicles 150 machine guns 54 guns 12 mortars |

2 pre-dreadnought battleships 2 cruisers 1 protected cruiser 21 destroyers 3 gunboats 3 submarines 24,000 soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 torpedo boat sunk (S 64) 7 minesweepers destroyed 9 trawlers & auxiliary vessels destroyed 5 aircraft shot down 156 killed 60 wounded (Navy) 54 killed 141 wounded (Army) |

1 battleship sunk (Slava) 1 destroyer sunk (Grom) 1 submarine destroyed (HMS C32) 20,130 captured 141 guns lost (47 heavy guns) 130 machine guns lost 40 aircraft lost | ||||||

| |||||||

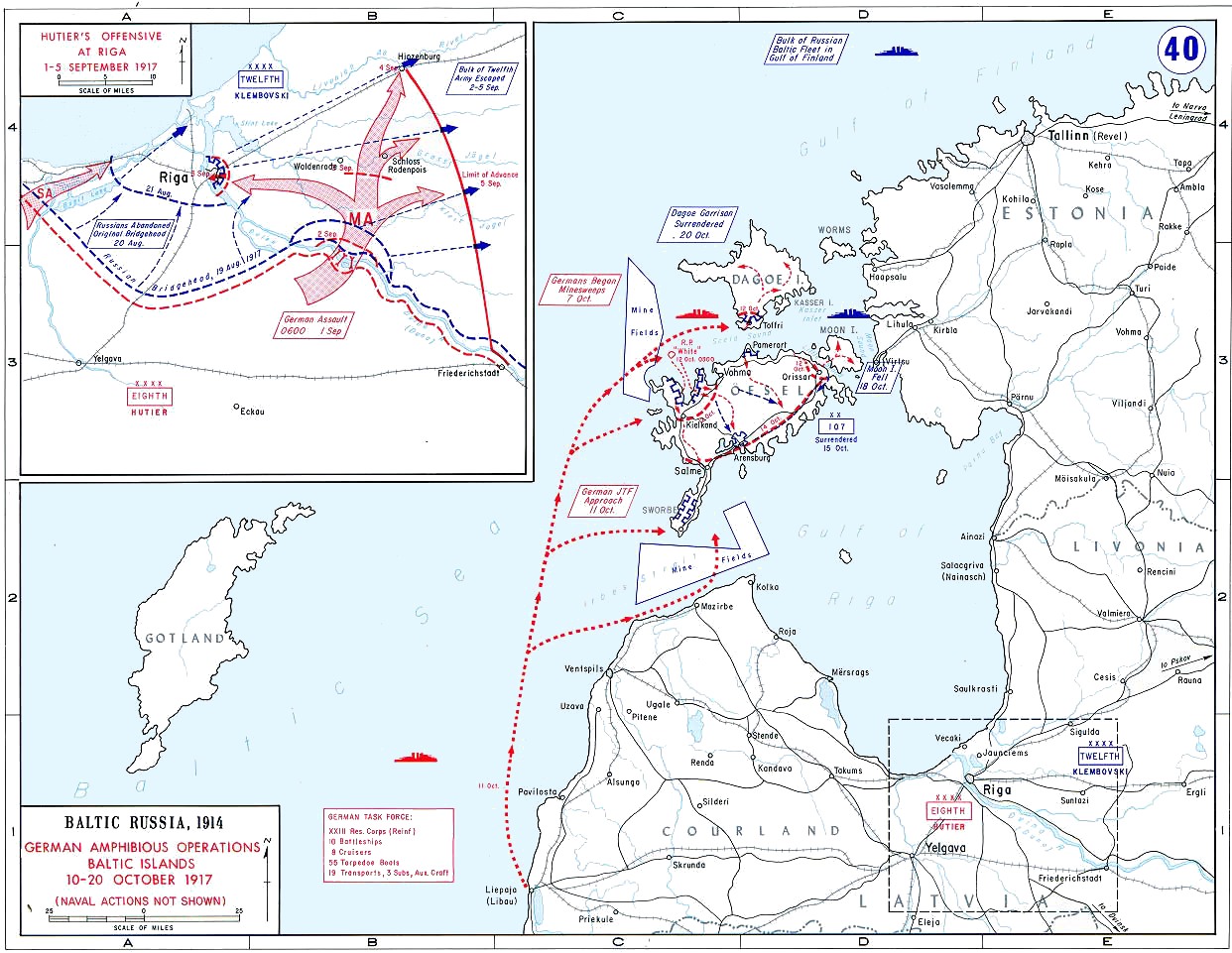

Operation Albion was a German air, land and naval operation in the First World War, against Russian forces in October 1917 to occupy the West Estonian Archipelago. The campaign aimed to occupy the Baltic islands of Saaremaa (Ösel), Hiiumaa (Dagö) and Muhu (Moon). The three islands were part of the Russian Empire and strategically dominated the central and northern Baltic Sea. The land campaign opened with German landings at the Tagalaht (Tagga) bay on the island of Saaremaa (Ösel), on 12 October, after extensive naval operations to clear mines and subdue coastal artillery batteries. German forces secured the island by 16 October and the Russian army evacuated Muhu (Moon) on 20 October.

After two failed attempts, the German army landed on Hiiumaa (Dagö) on 12 October, capturing the island the following day. The Russian Baltic Fleet had to withdraw from the Suur Strait after its losses at the Battle of Moon Sound. The Germans claimed 20,000 prisoners and 100 guns captured during Operation Albion from 12 to 20 October 1917.

Strategic significance

[edit]At the beginning of the First World War, the islands were of little importance to the Russian Empire or Germany. After the revolutionary turmoil in Russia during the early part of 1917, the German high command believed capturing the islands would outflank Russian defences and lay Petrograd (St. Petersburg) vulnerable to attack.[1][2]

Order of battle

[edit]German units

[edit]- Naval Forces[3](Sonderverband): Vice Admiral Ehrhard Schmidt

- Battlecruiser: Moltke (flagship)

- III Battle Squadron (III. Geschwader) (Vice Admiral Paul Behncke) dreadnought battleships: König (flagship), Bayern, Grosser Kurfürst, Kronprinz, Markgraf

- IV Battle Squadron (IV. Geschwader) (Vice Admiral Wilhelm Souchon) dreadnought battleships: Friedrich der Grosse (flagship), König Albert, Kaiserin, Prinzregent Luitpold, Kaiser

- II Scouting Group (II. Aufklärungsgruppe) (Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter) light cruisers: Königsberg (flagship), Karlsruhe, Nürnberg, Frankfurt, Danzig

- IV Scouting Group (VI. Aufklärungsgruppe) (Rear Admiral Albert Hopman) light cruisers: Kolberg (flagship), Strassburg, Augsburg; minelayer: Nautilus; tender: Blitz

- Torpedo Boats (Commodore Paul Heinrich) cruiser: Emden (flagship)

- II Torpedo Boat Flotilla: B 98; 3rd Half-Flotilla: G 101, V 100, G 103, G 104; 4th Half-Flotilla: B 109, B 110, B 111, B 97, B 112

- VI Torpedo Boat Flotilla: V 69; 12th Half-Flotilla: V 43, S 50, V 44, V 45, V 46; 13th Half-Flotilla: V 82, S 64, S 61, S 63, V 74

- VIII Torpedo Boat Flotilla: V 180; 15th Half-Flotilla: V 183, V 185, V 181, V 184, V 182; 16th Half-Flotilla: S 176, S 178, G 174, S 179, V 186

- X Torpedo Boat Flotilla:: S 56; 19th Half-Flotilla: T 170, T 169, T 172, G 175, T 165; 20th Half-Flotilla: V 78, V 77, G 89, S 65, S 66

- VII Half-Flotilla: T 154, T 158, T 157, T 151, T 160, T 145, T 140, T 139

- Courland Submarine Flotilla (U-BootsFlottille Kurland): UC 56, UC 57, UC 58, UC 59, UC 60, UC 78

- Minesweepers (Minensuchdienst)

- II Minesweeper Flotilla: A 62; 3rd Half-Flotilla: T 136, M 67, M 68, M 75, M 76, M 77, T 59, T 65, T 68, T 82, T 85; 4th Half-Flotilla: T 104, T 53, T 54, T 55, T 56, T 60, T 61, T 62, T 66, T 67, T 69; 8th Half-Flotilla: M 64, M 11, M 31, M 32, M 39, A 35

- III Half-Flotilla of the Search Flotilla: T 141, 15 motor-boats

- Mine-Searcher Group of the Outpost Half-Flotilla East: 6 fishing vessels

- I Minesweeper Division (Riga): 11 motor-boats

- II Minesweeper Division: 12 motor-boats

- III Minesweeper Division: 12 motor-boats

- IV Minesweeper Division: 10 motor-boats; outpost boat O 2

- Mine-barrage Breaker group (Sperrbrechergruppe): Rio Parbo, Lothar, Schwaben, Elass

- Anti-Submarine Forces (U-Bootsabwehr)

- Baltic Search Flotilla: T 144; 1st half-flotilla: T 142, A 32, A 28, A 30, 32 fishing vessels; 2nd half-flotilla: T 130, A 31, A 27, A 29, 24 fishing vessels

- Ground Forces: Generalleutnant Ludwig von Estorff

- 42nd Division

- 2nd Infanterie Cyclist Brigade

Russian units

[edit]- 425th, 426th and 472nd Infantry Regiments

- Battleships: Grazhdanin, Slava

- Armored cruisers: Admiral Makarov, Bayan

- Destroyers: Desna, Novik, Pobeditel, Zabiyaka, Grom, Konstantin

- Gunboats: Khivinets, Grozyashchy

- Blockship: Lavwija

- Minelayer: Pripyat[4]

British units

[edit]See also

[edit]Citations and references

[edit]- ^ Barrett 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Buttar 2017, pp. 217–225.

- ^ Gagern 1964.

- ^ Operation Albion: The Attack On The Baltic Islands

Cited sources

[edit]- Barrett, M. B. (2008). Operation Albion: The German Conquest of the Baltic Islands. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34969-9.

- Buttar, Prit (2017). Russia's Last Gasp: The Eastern Front 1916–17. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-47-282489-9.

- Gagern, Ernst Freiherr von (1964). Der Krieg zur See 1914–1918: Der Krieg in der Ostsee Bd.3 [The War at Sea 1914−1918: The War in the Eastern Sea]. Vol. III. Frankfurt: Mittler & Sohn. OCLC 1240432483.

External links

[edit]Operation Albion

View on GrokipediaBackground

Strategic Context

The collapse of the Russian war effort on the Eastern Front was accelerated by the February Revolution of 1917, which led to the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the formation of the Provisional Government, resulting in widespread demoralization and indiscipline within the Russian army. The subsequent failure of the Kerensky Offensive in July 1917 triggered mass mutinies, desertions, and a breakdown in command structures, further eroding combat effectiveness across the front. By the time of the October Revolution in November 1917, Bolshevik influence had deepened these divisions, prompting calls for an immediate end to hostilities and rendering Russian defenses in the Baltic region particularly vulnerable. In response to these developments, German naval strategy in the Baltic Sea shifted toward exploiting Russian weaknesses to achieve dominance over the theater. The Imperial German Navy sought to neutralize the Russian Baltic Fleet, which was primarily based in Helsingfors (modern Helsinki), and to establish a position from which to threaten Petrograd directly through the Gulf of Finland. This approach aimed to outflank Russian positions at Riga—captured by Germany in early September 1917—and to secure unrestricted access to the Gulf of Riga, thereby enhancing overall operational freedom in the eastern Baltic.[8] Prior to the revolutions, the West Estonian islands—Saaremaa (Ösel), Hiiumaa (Dagö), and Muhu (Moon)—held limited strategic value in the broader war, serving mainly as peripheral outposts in Russian control of the Baltic approaches. However, the post-revolutionary chaos transformed them into critical targets, as their capture would dismantle Russian naval barriers and facilitate potential advances toward the Russian heartland. German reconnaissance flights over the islands during the summer of 1917 provided essential intelligence on defenses, confirming the viability of an amphibious operation amid the deteriorating Russian situation.[9]Planning and Preparations

In the wake of the German capture of Riga in early September 1917, the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL), led by Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff, decided to pursue an amphibious assault on the Russian-held Baltic islands to exploit Russia's weakening position and potentially threaten Petrograd, thereby accelerating its withdrawal from the war.[2] The operation's planning originated from earlier naval proposals dating to August 1917, with formal agreement reached on 13 August between the OHL and Admiral Henning von Holtzendorf of the Admiralty staff to launch the assault following Riga's fall.[10] A joint army-navy planning committee was established in mid-September under General Oskar von Hutier of the Eighth Army, issuing operational orders on 18 September and selecting the codename "Albion" to preserve secrecy.[11][4][2] Logistical preparations centered on forming the Sonderverband Ostsee (Special Baltic Detachment) under Vice Admiral Ehrhard Schmidt, assembling roughly 24,000 troops, 5,000 horses, and 1,400 vehicles at the port of Libau by late September, supported by a naval contingent that included 10 dreadnought battleships for fire support and multiple mine-sweeping flotillas to navigate the heavily mined approaches.[4][2] Key challenges arose from the lack of specialized amphibious equipment, relying instead on towed barges and steamers for troop transport, compounded by stormy weather that postponed the fleet's departure from Wilhelmshaven until 23 September and the overall operation until early October.[4][2] The entire buildup occurred over approximately one month, with von Hutier overseeing embarkation for nearly two weeks to ensure coordination between ground and naval elements.[2][11] Russian preparations were hampered by widespread demoralization and revolutionary unrest in the aftermath of the February Revolution, leaving island garrisons—nominally 24,000 strong—plagued by mutinies, desertions, and poor discipline under Admiral Mikhail Bakhirev's naval command.[4][3] Fortifications remained incomplete, with limited fieldworks and bridgeheads around key causeways like the one connecting Saaremaa and Muhu, as resources were diverted to mainland upheavals rather than island defenses.[4] The primary defensive strategy relied on dense minefields in the Gulf of Riga and Irben Strait—exceeding 10,000 mines in the former and 1,300 in Moon Sound—along with coastal batteries mounting 15.2 cm to 30.5 cm guns, though maintenance and manning were inconsistent due to internal discord.[4][3] Russian intelligence detected German troop movements and fleet concentrations but misinterpreted the weather and exact objectives, assuming an assault was improbable and dispatching only minimal reinforcements.[2] German intelligence played a crucial role through aerial reconnaissance flights starting in early October, including missions on 1, 5, 9, and 10 October that dropped over 5,900 kg of bombs on Russian air stations and identified sparse defenses at potential landing sites such as Tagalaht Bay on Saaremaa.[4] These efforts, conducted by seaplanes and fighters, pinpointed weak points in Russian positions and steamer movements off Zerel, enabling planners to select undefended beaches for the initial assault while Russians remained uncertain of the invasion's scale and timing.[4][2]Opposing Forces

German Order of Battle

The German forces committed to Operation Albion were under the overall naval command of Vice Admiral Ehrhard Schmidt, who led the Special Unit (Sonderverband) of the High Seas Fleet, while the army contingent was directed by Lieutenant General Hugo von Kathen as commander of the XXIII Reserve Corps.[12][4] This joint operation marked one of the few large-scale amphibious assaults by German forces during World War I, emphasizing close coordination between sea, land, and air elements to seize the West Estonian islands.[13]Naval Forces

The naval component formed the backbone of the invasion, providing bombardment, escort, and transport capabilities across more than 300 vessels.[12] The main battle force included the battlecruiser SMS Moltke as flagship, supported by ten dreadnought battleships divided between the 3rd Battle Squadron (under Vice Admiral Paul Behncke, with ships such as SMS König, SMS Bayern, SMS Grosser Kurfürst, SMS Kronprinz, and SMS Markgraf) and the 4th Battle Squadron (under Vice Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, including SMS Friedrich der Große, SMS Kaiser, SMS Kaiserin, SMS Prinzregent Luitpold, and SMS König Albert).[14] These capital ships delivered heavy gunfire to suppress Russian coastal defenses. Light forces consisted of eleven light cruisers from the 2nd Scouting Group (under Rear Admiral Konrad von Reuter, e.g., SMS Königsberg, SMS Karlsruhe) and the 6th Scouting Group (under Rear Admiral Erich Koops, e.g., SMS Kolberg, SMS Strassburg), which handled reconnaissance and torpedo defense.[14] Screening duties fell to 53 torpedo boats and destroyers organized in ten flotillas (e.g., the 3rd, 6th, and 9th Torpedo Boat Flotillas, with vessels like SMS V69 and SMS S56), while eight submarines (UC-56, UC-57, UC-58, UC-59, UC-60, UC-78, and two others from U-Flotilla Kurland) patrolled for Russian naval threats.[14][4] Mine-layers and over 50 minesweeping vessels were essential for clearing paths through the heavily mined Gulf of Riga and Soela Strait, drawn from five minesweeper divisions, the II Minesweeper Flotilla (including the 3rd, 4th, and 8th Half-Flotillas), and specialized groups like the Sperrbrecher (e.g., Rio Pardo, Lothar, Schwaben).[14] Troop transports, ammunition ships, and hospital vessels (four in total) facilitated the movement of army units from assembly points at Libau and Windau.[14][12]Army Forces

The ground assault force comprised approximately 24,600 officers and men from the XXIII Reserve Corps, transported in 19 steamers and landed in two echelons at Tagga Bay on Saaremaa.[12] The core units were the reinforced 42nd Infantry Division (under Major General Ludwig von Estorff), including the 65th Infantry Brigade (131st and 255th Infantry Regiments) and 66th Infantry Brigade (138th and 234th Infantry Regiments), augmented by the 2nd Infantry Cyclist Brigade for mobile operations.[4][12] Supporting equipment included 5,000 horses, 1,400 vehicles, 150 machine guns, 54 field guns, and 12 mortars, providing the firepower needed for island combat.[4]Air Forces

Aerial support totaled over 100 aircraft, primarily from naval aviation, with 81 seaplanes for reconnaissance and spotting, 16 land-based aircraft from Army Detachments Holtzmann and Baerens, and six airships (e.g., L 30, L 37, LZ 113, LZ 120, SL 8, SL 20) for long-range bombing and patrol.[14][12] These assets conducted pre-invasion strikes on Russian batteries and provided real-time intelligence during landings.[13]Russian Order of Battle

The Russian defensive forces during Operation Albion were significantly weakened by the ongoing effects of the February Revolution, which led to widespread indiscipline, mutinies, and low morale among both naval and land units, exacerbated by the relocation of the main Baltic Fleet to Helsingfors (modern Helsinki) for political reasons.[3] Overall command of the Riga Bay Operations Group fell to Vice Admiral Mikhail Bakhirev, who oversaw the naval detachment supporting the island garrisons, while land defenses under General Dryomov of the 107th Infantry Division suffered from poor coordination and desertions that reduced effective fighting strength.[14][15] Naval forces under Bakhirev's direct control included two pre-dreadnought battleships, Slava and Grazhdanin, along with five cruisers including Bayan, Admiral Makarov, and Diana, and approximately 26 destroyers divided into several flotillas, including the 11th, 12th, and 13th Divisions.[14][4] The detachment also featured 12 submarines, three minelayers (Amur, Pripyat, Volga), and support vessels like gunboats (Khrabri, Grozyashchi, Khivenetz) and minesweepers, with heavy reliance on minefields in the Moon Sound strait to compensate for the absence of the fleet's five dreadnoughts (Petropavlovsk, Gangut, Sevastopol, Poltava, and Yevstafi), which remained at Helsingfors and provided no direct support.[14][3] Land forces garrisoning the islands totaled around 24,000 troops, primarily infantry from regiments such as the 425th, 426th, and 472nd, deployed across Saaremaa, Hiiumaa, and Muhu with fragmented command structures that hindered unified resistance.[4] These units were equipped with approximately 130 artillery pieces, including coastal batteries like those at Pamerort (four 30.5 cm guns) and Cape Hundsort (four 15.2 cm guns), though many fortifications were outdated and exposed, contributing to their rapid neutralization.[4] Morale issues manifested in high desertion rates and reluctance to engage, with revolutionary committees on ships and among troops often undermining officers' authority.[15][3] Air support was minimal, consisting of a handful of seaplanes for reconnaissance from island bases, which proved ineffective against superior German aerial operations and offered little beyond sporadic spotting for coastal guns.[10] The overall defensive strategy thus depended heavily on static defenses like minefields and batteries rather than mobile or integrated forces.[15]Allied Involvement

The British Royal Navy deployed a submarine flotilla to the Baltic Sea in support of the Russian Baltic Fleet starting in late 1914, with the first successful arrivals of E-class submarines in early 1915, aimed at interdicting German supply lines, particularly iron ore shipments from Sweden to Germany.[16] By mid-1915, the flotilla had grown to six submarines, primarily E-class vessels such as HMS E1, HMS E8, HMS E9, and HMS E19, operating from bases like Reval (modern Tallinn) in coordination with Russian naval commands.[16] These submarines conducted patrols to harass German merchant and naval traffic, achieving notable early successes, including the sinking of multiple cargo ships by November 1915, which disrupted vital wartime imports for Germany.[16] In the lead-up to Operation Albion in October 1917, British submarines maintained their interdiction role amid deteriorating Russian morale following the February Revolution, with liaison officers facilitating joint operations despite growing coordination challenges from revolutionary unrest within the Russian fleet.[17] On October 11, HMS E1 sighted the departing German invasion force from Libau but failed to launch an effective attack or alert Russian forces in time, highlighting the flotilla's limited intelligence-sharing capabilities.[4] The flotilla, numbering around six to eight submarines by 1917—including reinforcements of smaller C-class vessels like HMS C26, HMS C27, and HMS C32—remained attached to Russian command structures, though their overall impact was constrained by the small force size and the extensive German minefields in the operational area.[18] During the operation, British submarines focused on harassing German shipping and supporting Russian defenses in the Gulf of Riga and Moon Sound, but their efforts proved largely ineffective against the heavily mined waters and superior German escorts. On October 16, HMS C27, under Lieutenant Sealy, fired torpedoes at German vessels, reportedly striking two ships, while HMS C32 under Lieutenant Satow patrolled nearby; these actions contributed to the sinking of the German minesweeper T46 and destroyer V99, though broader German advances continued unchecked.[17] Post-landing, the submarines attempted further patrols to disrupt German reinforcements, but dense minefields and the rapid Russian withdrawal limited successes, with the presence of Allied submarines ultimately prompting a cautious German pullback on October 20 for dissuasion rather than decisive engagements.[17] The British involvement resulted in no major engagements or casualties during Operation Albion itself, reflecting the flotilla's peripheral role amid the Russian fleet's collapse.[17] Following the operation's conclusion, the submarines redeployed northward to Hanko, Finland, as Russian defenses crumbled, and the entire flotilla was scuttled off Helsinki in April 1918 to prevent capture by advancing German forces after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.[16]Course of the Operation

Initial Landings on Saaremaa

The initial landings of Operation Albion targeted Saaremaa (German: Ösel) island as the primary objective, with the German XXIII Reserve Corps, comprising approximately 23,000 troops including the 42nd Infantry Division and the 2nd Infantry Cyclist Brigade, assigned to the amphibious assault.[4] The main assault focused on Tagalaht (Tagga) Bay on the northwest coast, while a secondary landing occurred at the nearby Pamerort site to the east, allowing for a coordinated push inland.[4] Prior to the landings, German naval forces conducted extensive mine-sweeping operations in the approach channels and a heavy bombardment using dreadnoughts from Squadrons III and IV to suppress Russian coastal batteries at positions such as Hundsort, Ninnast, and Toffri.[4][15] H-hour was set for dawn on October 12, 1917, around 0500 hours, with pioneer units leading the way to secure beachheads.[4] The assault began under cover of naval gunfire, which effectively neutralized most Russian artillery, though sporadic defensive fire continued from remaining positions.[4] By 0800 hours, over 3,000 troops from the advance guard had disembarked at Tagalaht, establishing a firm bridgehead despite challenges from minefields—one transport, the Corsica, struck a mine at 0535 hours—and the soft, muddy terrain that hindered movement of men and equipment.[4][15] Russian forces, numbering around 24,000 on the islands but with lower effective strength due to morale issues, offered only light initial resistance at the beaches, allowing German pioneers to push forward rapidly.[4] The first German casualties occurred from this defensive fire, but counterattacks by Russian units were quickly repelled as the landing force organized.[15] By evening on October 12, the beachhead was secured, and German troops advanced inland, with infantry reaching Papensholm and the cyclist brigade moving toward the strategic stone causeway linking Saaremaa to the mainland to block Russian withdrawals.[4] On October 13, coastal forts were captured following continued naval support, and the advance pressed on toward Kuressaare (Arensburg) despite ongoing artillery duels and the difficult, swampy ground that slowed artillery deployment.[4] These initial successes established a foothold on Saaremaa, setting the stage for further operations while demonstrating effective joint army-navy coordination despite the absence of formal amphibious doctrine.[15]Battle of Moon Sound

Following the successful German landings on Saaremaa, which secured a foothold for further advances, the Battle of Moon Sound unfolded as the decisive naval engagement to consolidate control over the West Estonian archipelago. On October 17, 1917, after intensive mine-clearing operations by the German II Minesweeper Flotilla starting at 0600 hours, Vice Admiral Paul Behncke's Gruppe Behncke—comprising dreadnought battleships SMS König and SMS Kronprinz, supported by cruisers and destroyers—entered the southern end of Moon Sound strait through the swept channel south of a trapezoidal minefield.[1] The Russian Baltic Fleet, under Vice Admiral Mikhail Bakhirev, positioned battleships Slava and Grazhdanin (pre-dreadnoughts) along with the armored cruiser Bayan and several destroyers to block the German advance and protect the northern exit leading to the Gulf of Finland.[19] Shore batteries at Woi Island provided additional fire support to the Russian squadron, aiming to exploit the shallow waters and remaining minefields to impede the deeper-draft German capital ships.[1] The engagement commenced at 0722 hours when the Russian ships opened fire on the approaching Germans from superior range, with Slava and Grazhdanin leveraging their 12-inch guns against the German dreadnoughts.[1] König responded by targeting Russian destroyers and then engaging Slava at long range around 1000 hours after an initial German withdrawal to reposition; shells from König and Kronprinz struck Slava at 1013 hours, causing severe flooding (over 1,130 tonnes of water) and rendering her unnavigable.[1] The Russian cruiser Bayan was also hit multiple times at 1036 hours, igniting fires and forcing her to disengage, while Grazhdanin sustained only minor damage. Battlecruiser SMS Moltke joined the fray later, contributing to the long-range bombardment that overwhelmed the outdated Russian pre-dreadnoughts.[2] By 1030 hours, Bakhirev ordered a general withdrawal northward to avoid encirclement by the advancing German fleet and land forces, but Slava was scuttled by her crew at 1155 hours to prevent capture.[1] Tactical constraints shaped the battle's progression: the Germans paused their pursuit at 0812 hours due to Slava's effective gunnery at 24 kilometers—beyond the optimal range of their own 30.5 cm guns—and the risks posed by shallow depths (as little as 10 meters in places) and uncleared mines, which later damaged two German dreadnoughts.[1] Bakhirev's decision to retreat stemmed from the realization that prolonged combat would trap his squadron against German land positions on Saaremaa and Muhu, compounded by the demoralization within the post-revolutionary Russian fleet.[3] The remaining Russian ships, including Bayan and Grazhdanin, successfully evaded further damage and withdrew to Helsinki (then part of the route to Petrograd), effectively ceding naval control of Moon Sound and the surrounding waters to the Germans.[19] The battle's outcome sealed German dominance in the Baltic approaches, with the Russian Baltic Fleet's retreat neutralizing any immediate threat to German operations and allowing unhindered supply lines for island garrisons.[2] This naval victory facilitated the surrender of approximately 20,000 Russian troops isolated on Saaremaa and adjacent islands, along with significant artillery and equipment, marking a pivotal step in Operation Albion's success.[2]Capture of Hiiumaa and Muhu

Following the successful landings on Saaremaa, German forces established a bridgehead on Muhu via the connecting causeway. Russian defenders, plagued by low morale and widespread desertions amid the Bolshevik Revolution, offered minimal resistance and began evacuating the island on October 18, 1917, allowing German troops to occupy key positions with little fighting.[20][15] Concurrently, German naval and land elements attempted to seize Hiiumaa through amphibious assault from the south, but the first two efforts on October 18 failed due to rough seas and Russian coastal fire. On October 19, after bombardment from supporting warships including the dreadnought Kaiser, approximately 3,000 troops from the 42nd Infantry Division landed successfully near Lõuna Bay despite weak opposition from retreating Russian garrisons. Russian forces, numbering around 2,000, conducted a hasty withdrawal northward, destroying several artillery pieces to deny their capture, while desertions further eroded their cohesion.[17][21] By October 20, 1917, German units had swiftly advanced across Hiiumaa, capturing the island's main settlements and ports with negligible losses, completing the seizure of the West Estonian archipelago. This peripheral operation, enabled by the prior control of Saaremaa, secured vital naval anchorages such as those at Arensburg and ensured uncontested German dominance in the region.[17][20]Aftermath and Consequences

Casualties and Captures

The German forces incurred relatively light casualties during Operation Albion, reflecting the operation's overall success and the rapid collapse of Russian defenses. Naval personnel suffered 156 killed and 60 wounded, primarily from mines, aircraft attacks, and engagements in the Irben Strait and Moon Sound. Army losses were even lower, with 54 killed and 141 wounded, mostly during the initial landings on Saaremaa and subsequent advances. Ship damage was minimal, limited to one torpedo boat (S 64) sunk by a mine, alongside several minesweepers and auxiliary vessels lost to mines and air strikes.[1] Russian losses were disproportionately heavy, underscoring the demoralized state of their forces amid the Bolshevik Revolution's onset. Approximately 20,130 soldiers were captured, the vast majority on Saaremaa as German troops overran positions with little resistance. Killed and wounded figures are not precisely documented but were relatively light compared to captures, concentrated in naval actions like the Battle of Moon Sound and scattered land fighting. The Russian Navy lost the pre-dreadnought battleship Slava, which was scuttled after sustaining heavy damage from German dreadnought fire, along with the destroyer Grom captured. Additionally, German forces seized 141 artillery pieces, including 47 heavy guns, and 130 machine guns, crippling Russian defensive capabilities on the islands.[1] Allied involvement, primarily British submarines operating in support of Russia, resulted in negligible casualties, with no losses in direct combat against German forces. One British submarine, HMS C32, ran aground on a mudbank in the Gulf of Riga while attempting to interdict German movements but was not sunk in action.| Side | Killed | Wounded | Captured | Key Material Losses/Captures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| German (Navy) | 156 | 60 | - | 1 torpedo boat sunk, several auxiliaries lost |

| German (Army) | 54 | 141 | - | Minimal equipment losses |

| Russian | Undocumented (relatively light) | Undocumented (relatively light) | 20,130 | Slava sunk, Grom captured, 141 guns (47 heavy), 130 machine guns seized |

| British (Allied) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 submarine stranded (no combat loss) |