Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ore genesis

View on Wikipedia

Various theories of ore genesis explain how the various types of mineral deposits form within Earth's crust. Ore-genesis theories vary depending on the mineral or commodity examined.

Ore-genesis theories generally involve three components: source, transport or conduit, and trap. (This also applies to the petroleum industry: petroleum geologists originated this analysis.)

- Source is required because metal must come from somewhere, and be liberated by some process.

- Transport is required first to move the metal-bearing fluids or solid minerals into their current position, and refers to the act of physically moving the metal, as well as to chemical or physical phenomena which encourage movement.

- Trapping is required to concentrate the metal via some physical, chemical, or geological mechanism into a concentration which forms mineable ore.

The biggest deposits form when the source is large, the transport mechanism is efficient, and the trap is active and ready at the right time.

Ore genesis processes

[edit]This section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (November 2016) |

Endogenous

[edit]Magmatic processes

[edit]- Fractional crystallization: separates ore and non-ore minerals according to their crystallization temperature. As early crystallizing minerals form from magma, they incorporate certain elements, some of which are metals. These crystals may settle onto the bottom of the intrusion, concentrating ore minerals there. Chromite and magnetite are ore minerals that form in this way.[1]

- Liquid immiscibility: sulfide ores containing copper, nickel, or platinum may form from this process. As a magma changes, parts of it may separate from the main body of magma. Two liquids that will not mix are called immiscible; oil and water are an example. In magmas, sulfides may separate and sink below the silicate-rich part of the intrusion or be injected into the rock surrounding it. These deposits are found in mafic and ultramafic rocks.

Hydrothermal processes

[edit]These processes are the physicochemical phenomena and reactions caused by movement of hydrothermal water within the crust, often as a consequence of magmatic intrusion or tectonic upheavals. The foundations of hydrothermal processes are the source-transport-trap mechanism.

Sources of hydrothermal solutions include seawater and meteoric water circulating through fractured rock, formational brines (water trapped within sediments at deposition), and metamorphic fluids created by dehydration of hydrous minerals during metamorphism.

Metal sources may include a plethora of rocks. However most metals of economic importance are carried as trace elements within rock-forming minerals, and so may be liberated by hydrothermal processes. This happens because of:

- incompatibility of the metal with its host mineral, for example zinc in calcite, which favours aqueous fluids in contact with the host mineral during diagenesis.

- solubility of the host mineral within nascent hydrothermal solutions in the source rocks, for example mineral salts (halite), carbonates (cerussite), phosphates (monazite and thorianite), and sulfates (barite)

- elevated temperatures causing decomposition reactions of minerals

Transport by hydrothermal solutions usually requires a salt or other soluble species which can form a metal-bearing complex. These metal-bearing complexes facilitate transport of metals within aqueous solutions, generally as hydroxides, but also by processes similar to chelation.

This process is especially well understood in gold metallogeny where various thiosulfate, chloride, and other gold-carrying chemical complexes (notably tellurium-chloride/sulfate or antimony-chloride/sulfate). The majority of metal deposits formed by hydrothermal processes include sulfide minerals, indicating sulfur is an important metal-carrying complex.

Sulfide deposition

[edit]Sulfide deposition within the trap zone occurs when metal-carrying sulfate, sulfide, or other complexes become chemically unstable due to one or more of the following processes;

- falling temperature, which renders the complex unstable or metal insoluble

- loss of pressure, which has the same effect

- reaction with chemically reactive wall rocks, usually of reduced oxidation state, such as iron-bearing rocks, mafic or ultramafic rocks, or carbonate rocks

- degassing of the hydrothermal fluid into a gas and water system, or boiling, which alters the metal carrying capacity of the solution and even destroys metal-carrying chemical complexes

Metal can also precipitate when temperature and pressure or oxidation state favour different ionic complexes in the water, for instance the change from sulfide to sulfate, oxygen fugacity, exchange of metals between sulfide and chloride complexes, et cetera.

Metamorphic processes

[edit]Lateral secretion

[edit]Ore deposits formed by lateral secretion are formed by metamorphic reactions during shearing, which liberate mineral constituents such as quartz, sulfides, gold, carbonates, and oxides from deforming rocks, and focus these constituents into zones of reduced pressure or dilation such as faults. This may occur without much hydrothermal fluid flow, and this is typical of podiform chromite deposits.

Metamorphic processes also control many physical processes which form the source of hydrothermal fluids, outlined above.

Sedimentary or surficial processes (exogenous)

[edit]Surficial processes are the physical and chemical phenomena which cause concentration of ore material within the regolith, generally by the action of the environment. This includes placer deposits, laterite deposits, and residual or eluvial deposits. Superficial deposits processes of ore formation include;

- Erosion of non-ore material.

- Deposition by sedimentary processes, including winnowing, density separation (e.g.; gold placers).

- Weathering via oxidation or chemical attack of a rock, either liberating rock fragments or creating chemically deposited clays, laterites, or supergene enrichment.

- Deposition in low-energy environments in beach environments.

- Sedimentary Exhalative Deposits (SEDEX), formed on the sea floor from metal-bearing brines.

Classification of ore deposits

[edit]Classification of hydrothermal ore deposits is also achieved by classifying according to the temperature of formation, which roughly also correlates with particular mineralising fluids, mineral associations and structural styles.[2] This scheme, proposed by Waldemar Lindgren (1933) classified hydrothermal deposits as follows:[2]

- Hypothermal — mineral ore deposits formed at great depth under conditions of high temperature.[3]

- Mesothermal — mineral ore deposits formed at moderate temperature and pressure, in and along fissures or other openings in rocks, by deposition at intermediate depths, from hydrothermal fluids.[4]

- Epithermal — mineral ore deposits formed at low temperatures (50–200 °C) near the Earth's surface (<1500 m), that fill veins, breccias, and stockworks.[2]

- Telethermal — mineral ore deposits formed at shallow depth and relatively low temperatures, with little or no wall-rock alteration, presumably far from the source of hydrothermal solutions.[5]

Ore deposits are usually classified by ore formation processes and geological setting. For example, sedimentary exhalative deposits (SEDEX), are a class of ore deposit formed on the sea floor (sedimentary) by exhalation of brines into seawater (exhalative), causing chemical precipitation of ore minerals when the brine cools, mixes with sea water, and loses its metal carrying capacity.

Ore deposits rarely fit neatly into the categories in which geologists wish to place them. Many may be formed by one or more of the basic genesis processes above, creating ambiguous classifications and much argument and conjecture. Often ore deposits are classified after examples of their type, for instance Broken Hill type lead-zinc-silver deposits or Carlin–type gold deposits.

Genesis of common ores

[edit]As they require the conjunction of specific environmental conditions to form, particular mineral deposit types tend to occupy specific geodynamic niches,[6] therefore, this page has been organised by metal commodity. It is also possible to organise theories the other way, namely according to geological criteria of formation. Often ores of the same metal can be formed by multiple processes, and this is described here under each metal or metal complex.

Iron

[edit]Iron ores are overwhelmingly derived from ancient sediments known as banded iron formations (BIFs). These sediments are composed of iron oxide minerals deposited on the sea floor. Particular environmental conditions are needed to transport enough iron in sea water to form these deposits, such as acidic and oxygen-poor atmospheres within the Proterozoic Era.

Often, more recent weathering is required to convert the usual magnetite minerals into more easily processed hematite. Some iron deposits within the Pilbara of Western Australia are placer deposits, formed by accumulation of hematite gravels called pisolites which form channel-iron deposits. These are preferred because they are cheap to mine.

Lead zinc silver

[edit]Lead-zinc deposits are generally accompanied by silver, hosted within the lead sulfide mineral galena or within the zinc sulfide mineral sphalerite.

Lead and zinc deposits are formed by discharge of deep sedimentary brine onto the sea floor (termed sedimentary exhalative or SEDEX), or by replacement of limestone, in skarn deposits, some associated with submarine volcanoes (called volcanogenic massive sulfide ore deposits or VMS), or in the aureole of subvolcanic intrusions of granite. The vast majority of SEDEX lead and zinc deposits are Proterozoic in age, although there are significant Jurassic examples in Canada and Alaska.

The carbonate replacement type deposit is exemplified by the Mississippi valley type (MVT) ore deposits. MVT and similar styles occur by replacement and degradation of carbonate sequences by hydrocarbons, which are thought important for transporting lead.

Gold

[edit]

Gold deposits are formed via a very wide variety of geological processes. Deposits are classified as primary, alluvial or placer deposits, or residual or laterite deposits. Often a deposit will contain a mixture of all three types of ore.

Plate tectonics is the underlying mechanism for generating gold deposits. The majority of primary gold deposits fall into two main categories: lode gold deposits or intrusion-related deposits.

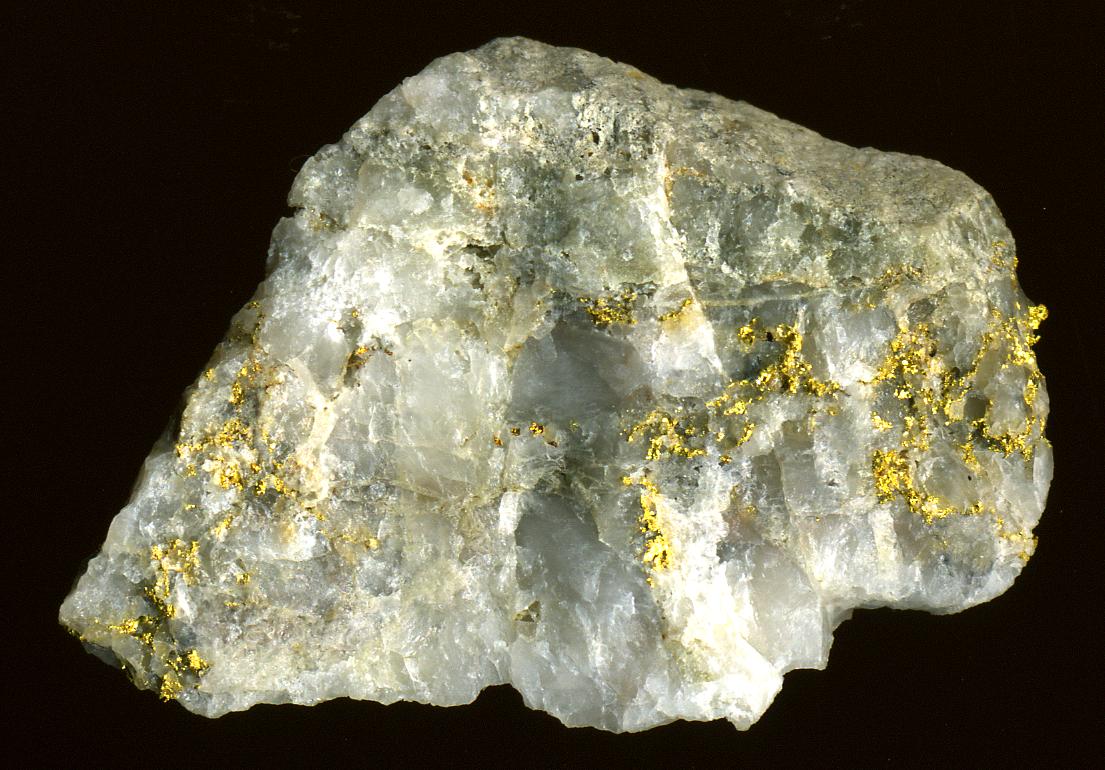

Lode gold deposits, also referred to as orogenic gold are generally high-grade, thin, vein and fault hosted. They are primarily made up of quartz veins also known as lodes or reefs, which contain either native gold or gold sulfides and tellurides. Lode gold deposits are usually hosted in basalt or in sediments known as turbidite, although when in faults, they may occupy intrusive igneous rocks such as granite.

Lode-gold deposits are intimately associated with orogeny and other plate collision events within geologic history. It is thought that most lode gold deposits are sourced from metamorphic rocks by the dehydration of basalt during metamorphism. The gold is transported up faults by hydrothermal waters and deposited when the water cools too much to retain gold in solution.

Intrusive related gold (Lang & Baker, 2001) is generally hosted in granites, porphyry, or rarely dikes. Intrusive related gold usually also contains copper, and is often associated with tin and tungsten, and rarely molybdenum, antimony, and uranium. Intrusive-related gold deposits rely on gold existing in the fluids associated with the magma (White, 2001), and the inevitable discharge of these hydrothermal fluids into the wall-rocks (Lowenstern, 2001). Skarn deposits are another manifestation of intrusive-related deposits.

Placer deposits are sourced from pre-existing gold deposits and are secondary deposits. Placer deposits are formed by alluvial processes within rivers and streams, and on beaches. Placer gold deposits form via gravity, with the density of gold causing it to sink into trap sites within the river bed, or where water velocity drops, such as bends in rivers and behind boulders. Often placer deposits are found within sedimentary rocks and can be billions of years old, for instance the Witwatersrand deposits in South Africa. Sedimentary placer deposits are known as 'leads' or 'deep leads'.

Placer deposits are often worked by fossicking, and panning for gold is a popular pastime.

Laterite gold deposits are formed from pre-existing gold deposits (including some placer deposits) during prolonged weathering of the bedrock. Gold is deposited within iron oxides in the weathered rock or regolith, and may be further enriched by reworking by erosion. Some laterite deposits are formed by wind erosion of the bedrock leaving a residuum of native gold metal at surface.

A bacterium, Cupriavidus metallidurans, plays a vital role in the formation of gold nuggets by precipitating metallic gold from a solution of gold (III) tetrachloride, a compound highly toxic to most other microorganisms.[8] Similarly, Delftia acidovorans can form gold nuggets.[9]

Platinum

[edit]Platinum and palladium are precious metals generally found in ultramafic rocks. The source of platinum and palladium deposits is ultramafic rocks which have enough sulfur to form a sulfide mineral while the magma is still liquid. This sulfide mineral (usually pentlandite, pyrite, chalcopyrite, or pyrrhotite) gains platinum by mixing with the bulk of the magma because platinum is chalcophile and is concentrated in sulfides. Alternatively, platinum occurs in association with chromite either within the chromite mineral itself or within sulfides associated with it.

Sulfide phases only form in ultramafic magmas when the magma reaches sulfur saturation. This is generally thought to be nearly impossible by pure fractional crystallisation, so other processes are usually required in ore genesis models to explain sulfur saturation. These include contamination of the magma with crustal material, especially sulfur-rich wall-rocks or sediments; magma mixing; volatile gain or loss.

Often platinum is associated with nickel, copper, chromium, and cobalt deposits.

Nickel

[edit]Nickel deposits are generally found in two forms, either as sulfide or laterite.

Sulfide type nickel deposits are formed in essentially the same manner as platinum deposits. Nickel is a chalcophile element which prefers sulfides, so an ultramafic or mafic rock which has a sulfide phase in the magma may form nickel sulfides. The best nickel deposits are formed where sulfide accumulates in the base of lava tubes or volcanic flows — especially komatiite lavas.

Komatiitic nickel-copper sulfide deposits are considered to be formed by a mixture of sulfide segregation, immiscibility, and thermal erosion of sulfidic sediments. The sediments are considered to be necessary to promote sulfur saturation.

Some subvolcanic sills in the Thompson Belt of Canada host nickel sulfide deposits formed by deposition of sulfides near the feeder vent. Sulfide was accumulated near the vent due to the loss of magma velocity at the vent interface. The massive Voisey's Bay nickel deposit is considered to have formed via a similar process.

The process of forming nickel laterite deposits is essentially similar to the formation of gold laterite deposits, except that ultramafic or mafic rocks are required. Generally nickel laterites require very large olivine-bearing ultramafic intrusions. Minerals formed in laterite nickel deposits include gibbsite.

Copper

[edit]Copper is found in association with many other metals and deposit styles. Commonly, copper is either formed within sedimentary rocks, or associated with igneous rocks.

The world's major copper deposits are formed within the granitic porphyry copper style. Copper is enriched by processes during crystallisation of the granite and forms as chalcopyrite — a sulfide mineral, which is carried up with the granite.

Sometimes granites erupt to surface as volcanoes, and copper mineralisation forms during this phase when the granite and volcanic rocks cool via hydrothermal circulation.

Sedimentary copper forms within ocean basins in sedimentary rocks. Generally this forms by brine from deeply buried sediments discharging into the deep sea, and precipitating copper and often lead and zinc sulfides directly onto the sea floor. This is then buried by further sediment. This is a process similar to SEDEX zinc and lead, although some carbonate-hosted examples exist.

Often copper is associated with gold, lead, zinc, and nickel deposits.

Uranium

[edit]

Uranium deposits are usually sourced from radioactive granites, where certain minerals such as monazite are leached during hydrothermal activity or during circulation of groundwater. The uranium is brought into solution by acidic conditions and is deposited when this acidity is neutralised. Generally this occurs in certain carbon-bearing sediments, within an unconformity in sedimentary strata. The majority of the world's nuclear power is sourced from uranium in such deposits.

Uranium is also found in nearly all coal at several parts per million, and in all granites. Radon is a common problem during mining of uranium as it is a radioactive gas.

Uranium is also found associated with certain igneous rocks, such as granite and porphyry. The Olympic Dam deposit in Australia is an example of this type of uranium deposit. It contains 70% of Australia's share of 40% of the known global low-cost recoverable uranium inventory.

Titanium and zirconium

[edit]Mineral sands are the predominant type of titanium, zirconium, and thorium deposit. They are formed by accumulation of such heavy minerals within beach systems, and are a type of placer deposits. The minerals which contain titanium are ilmenite, rutile, and leucoxene, zirconium is contained within zircon, and thorium is generally contained within monazite. These minerals are sourced from primarily granite bedrock by erosion and transported to the sea by rivers where they accumulate within beach sands. Rarely, but importantly, gold, tin, and platinum deposits can form in beach placer deposits.

Tin, tungsten, and molybdenum

[edit]These three metals generally form in a certain type of granite, via a similar mechanism to intrusive-related gold and copper. They are considered together because the process of forming these deposits is essentially the same. Skarn type mineralisation related to these granites is a very important type of tin, tungsten, and molybdenum deposit. Skarn deposits form by reaction of mineralised fluids from the granite reacting with wall rocks such as limestone. Skarn mineralisation is also important in lead, zinc, copper, gold, and occasionally uranium mineralisation.

Greisen granite is another related tin-molybdenum and topaz mineralisation style.

Rare-earths, niobium, tantalum, lithium

[edit]The overwhelming majority of rare-earth elements, tantalum, and lithium are found within pegmatite. Ore genesis theories for these ores are wide and varied, but most involve metamorphism and igneous activity.[10] Lithium is present as spodumene or lepidolite within pegmatite.

Carbonatite intrusions are an important source of these elements. Ore minerals are essentially part of the unusual mineralogy of carbonatite.

Phosphate

[edit]Phosphate is used in fertilisers. Immense quantities of phosphate rock or phosphorite occur in sedimentary shelf deposits, ranging in age from the Proterozoic to currently forming environments.[11] Phosphate deposits are thought to be sourced from the skeletons of dead sea creatures which accumulated on the seafloor. Similar to iron ore deposits and oil, particular conditions in the ocean and environment are thought to have contributed to these deposits within the geological past.

Phosphate deposits are also formed from alkaline igneous rocks such as nepheline syenites, carbonatites, and associated rock types. The phosphate is, in this case, contained within magmatic apatite, monazite, or other rare-earth phosphates.

Vanadium

[edit]

Due to the presence of vanabins, concentration of vanadium found in the blood cells of Ascidia gemmata belonging to the suborder Phlebobranchia is 10,000,000 times higher than that in the surrounding seawater. A similar biological process might have played a role in the formation of vanadium ores. Vanadium is also present in fossil fuel deposits such as crude oil, coal, oil shale, and oil sands. In crude oil, concentrations up to 1200 ppm have been reported.

Cosmic origins of rare metals

[edit]Precious metals such as gold and platinum, but also many other rare and noble metals, largely originated within neutron star collisions - collisions between exceedingly heavy massive and dense remnants of supernovas. In the final moments of the collision, the physical conditions are so extreme that these heavy rare elements can be formed, and are sprayed into space. Interstellar dust and gas clouds contain some of these elements, as did the dust cloud from which the Solar System formed.

Those heavy metals fell to the centre of the molten core of Earth, and are no longer accessible. However about 200 million years after Earth formed, a late heavy bombardment of meteors impacted Earth. As Earth had already begun to cool and solidify, the material (including heavy metals) in that bombardment became part of Earth's crust, rather than falling deep into the core. They became processed and exposed by geological processes over billions of years. It is believed that this represents the origin of many elements, and all heavy metals, that are now found on Earth.[12][13]

See also

[edit]- Mineral exploration – Finding commercially viable concentrations of minerals to mine.

- Copper extraction – Process of extracting copper from the ground

- Hydrothermal circulation – Circulation of water driven by heat exchange

- Economic geology – Science concerned with earth materials of economic value

- Mineral redox buffer – Geochemical assemblage

- Metasomatism – Chemical alteration of a rock by hydrothermal and other fluids

- Igneous differentiation – Geologic process in formation of some igneous rocks

- List of hyperaccumulators

References

[edit]- ^ Troll, Valentin R.; Weis, Franz A.; Jonsson, Erik; Andersson, Ulf B.; Majidi, Seyed Afshin; Högdahl, Karin; Harris, Chris; Millet, Marc-Alban; Chinnasamy, Sakthi Saravanan; Kooijman, Ellen; Nilsson, Katarina P. (2019-04-12). "Global Fe–O isotope correlation reveals magmatic origin of Kiruna-type apatite-iron-oxide ores". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1712. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1712T. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09244-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6461606. PMID 30979878.

- ^ a b c Camprubí, Antoni; et, al (2016). "Geochronology of Mexican mineral deposits. IV: the Cinco Minas epithermal deposit, Jalisco". Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana. 68 (2): 357–364. Bibcode:2016BoSGM..68..357C. doi:10.18268/BSGM2016v68n2a12.

- ^ Hypothermal.

- ^ Mesothermal.

- ^ Teletherma.

- ^ Groves, David I.; Bierlein, Frank P. (2007). "Geodynamic settings of mineral deposit systems". Journal of the Geological Society. 164 (1): 19–30. Bibcode:2007JGSoc.164...19G. doi:10.1144/0016-76492006-065. S2CID 129680970. Abstract

- ^ Geology and geochemistry of the Sleeper Gold Mine Archived 2017-02-12 at the Wayback Machine, USGS Open File Report 89-476, 1989

- ^ Reith, Frank; Stephen L. Rogers; D. C. McPhail; Daryl Webb (July 14, 2006). "Biomineralization of Gold: Biofilms on Bacterioform Gold". Science. 313 (5784): 233–236. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..233R. doi:10.1126/science.1125878. hdl:1885/28682. PMID 16840703. S2CID 32848104.

- ^ O'Hanlon, Larry (September 1, 2010). "Bacteria Make Gold Nuggets". Discovery News. Archived from the original on November 25, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ Sahlström, Fredrik; Jonsson, Erik; Högdahl, Karin; Troll, Valentin R.; Harris, Chris; Jolis, Ester M.; Weis, Franz (2019-10-23). "Interaction between high-temperature magmatic fluids and limestone explains 'Bastnäs-type' REE deposits in central Sweden". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 15203. Bibcode:2019NatSR...915203S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49321-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6811582. PMID 31645579.

- ^ Guilbert, John M. and Charles F. Park, The Geology of Ore Deposits, 1986, Freeman, pp. 715–720, ISBN 0-7167-1456-6

- ^ "Where does all Earth's gold come from? Precious metals the result of meteorite bombardment, rock analysis finds".

- ^ Willbold, Matthias; Elliott, Tim; Moorbath, Stephen (September 2011). "The tungsten isotopic composition of the Earth's mantle before the terminal bombardment". Nature. 477 (7363): 195–198. Bibcode:2011Natur.477..195W. doi:10.1038/nature10399. PMID 21901010. S2CID 4419046.

- Arne, D.C.; Bierlein, F.P.; Morgan, J.W.; Stein, H.J. (2001). "Re-Os Dating of Sulfides Associated With Gold Mineralisation in Central Victoria, Australia". Economic Geology. 96 (6): 1455–1459. Bibcode:2001EcGeo..96.1455A. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.96.6.1455.

- Dill, H.G. (2010). "The "chessboard" classification scheme of mineral deposits: Mineralogy and geology from aluminum to zirconium". Earth-Science Reviews. 100 (1–4): 1–420. Bibcode:2010ESRv..100....1D. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2009.10.011. S2CID 128609115.

- Elder, D.; Cashman, S. (1992). "Tectonic Control and Fluid Evolution in the Quartz Hill, California, Lode-gold Deposits". Economic Geology. 87 (7): 1795–1812. Bibcode:1992EcGeo..87.1795E. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.87.7.1795.

- Evans, A.M., 1993. Ore Geology and Industrial Minerals, An Introduction., Blackwell Science, ISBN 0-632-02953-6

- Groves, D.I. 1993. The Crustal Continuum Model for late-Archaean lode-gold deposits of the Yilgarn Block, Western Australia. Mineralium Deposita 28, pp366–374.

- Lang, J.R. & Baker, T., 2001. Intrusion-related gold systems: the present level of understanding. Mineralium Deposita, 36, pp 477–489

- Lindgren, W. (1922). "A suggestion for the terminology of certain mineral deposits". Economic Geology. 17 (4): 292–294. Bibcode:1922EcGeo..17..292L. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.17.4.292.

- Lindgren, Waldemar, 1933. Mineral Deposits, 4th ed., McGraw-Hill

- Lowenstern, J.B. (2001). "Carbon dioxide in magmas and implications for hydrothermal systems". Mineralium Deposita. 36 (6): 490–502. Bibcode:2001MinDe..36..490L. doi:10.1007/s001260100185. S2CID 140590124.

- Pettke, T; Frei, R.; Kramers, J.D.; Villa, I. M. (1997). "Isotope systematics in vein gold from Brusson, Val d'Ayas (NW Italy); (U+Th)/He and K/Ar in native Au and its fluid inclusions". Chemical Geology. 135 (3–4): 173–187. Bibcode:1997ChGeo.135..173P. doi:10.1016/s0009-2541(96)00114-3.

- Robb, L. (2005), Introduction to Ore-Forming Processes (Blackwell Science). ISBN 978-0-632-06378-9

- White, A.J.R (2001). "Water, restite and granite mineralisation". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 48 (4): 551–555. Bibcode:2001AuJES..48..551W. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0952.2001.00878.x. S2CID 140585355.