Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geology

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Geology |

|---|

|

Geology is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical bodies, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time.[1] The name comes from Ancient Greek γῆ (gê) 'earth' and λoγία (-logía) 'study of, discourse'.[2][3] Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth sciences, including hydrology. It is integrated with Earth system science and planetary science.

Geology describes the structure of the Earth on and beneath its surface and the processes that have shaped that structure. Geologists study the mineralogical composition of rocks in order to get insight into their history of formation. Geology determines the relative ages of rocks found at a given location; geochemistry (a branch of geology) determines their absolute ages.[4] By combining various petrological, crystallographic, and paleontological tools, geologists are able to chronicle the geological history of the Earth as a whole. One aspect is to demonstrate the age of the Earth. Geology provides evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and the Earth's past climates.

Geologists broadly study the properties and processes of Earth and other terrestrial planets. Geologists use a wide variety of methods to understand the Earth's structure and evolution, including fieldwork, rock description, geophysical techniques, chemical analysis, physical experiments, and numerical modelling. In practical terms, geology is important for mineral and hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation, evaluating water resources, understanding natural hazards, remediating environmental problems, and providing insights into past climate change. Geology is a major academic discipline, and it is central to geological engineering and plays an important role in geotechnical engineering.

Geological material

[edit]The majority of geological data comes from research on solid Earth materials. Meteorites and other extraterrestrial natural materials are also studied by geological methods.

Minerals

[edit]Minerals are naturally occurring elements and compounds with a definite homogeneous chemical composition and an ordered atomic arrangement. Amorphous substances that resemble a mineral are sometimes referred to as mineraloids, although there are exceptions such as georgeite and autunite. Some amorphous substances formed by geological processes are considered minerals if the original substance was a mineral before metamictisation.[5]

Each mineral has distinct physical properties, and there are many tests to determine each of them. Minerals are often identified through these tests. The specimens can be tested for:[6]

- Color: Minerals are grouped by their color. Mostly diagnostic but impurities can change a mineral's color.

- Streak: Performed by scratching the sample on a porcelain plate. The color of the streak can help identify the mineral.

- Hardness: The resistance of a mineral to scratching or indentation.

- Breakage pattern: A mineral can either show fracture or cleavage, the former being breakage of uneven surfaces, and the latter a breakage along closely spaced parallel planes.

- Luster: Quality of light reflected from the surface of a mineral. Examples are metallic, pearly, waxy, dull.

- Specific gravity: the weight of a specific volume of a mineral.

- Effervescence: Involves dripping hydrochloric acid on the mineral to test for fizzing.

- Magnetism: Involves using a magnet to test for magnetism.

- Taste: Minerals can have a distinctive taste such as halite (which tastes like table salt).

Rock

[edit]

A rock is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloids. Most research in geology is associated with the study of rocks, as they provide the primary record of the majority of the geological history of the Earth. There are three major types of rock: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic. The rock cycle illustrates the relationships among them (see diagram).[7]

When a rock solidifies or crystallizes from melt (magma or lava), it is an igneous rock.[8] The active flow of molten rock is closely studied in volcanology, and igneous petrology aims to determine the history of igneous rocks from their original molten source to their final crystallization.[9]

Rocks can be weathered and eroded, then redeposited and lithified into a sedimentary rock. Sedimentary rocks are mainly divided into four categories: sandstone, shale, carbonate, and evaporite. This group of classifications focuses partly on the size of sedimentary particles (sandstone and shale), and partly on mineralogy and formation processes (carbonation and evaporation).[10] Igneous and sedimentary rocks can then be turned into metamorphic rocks by heat and pressure that change its mineral content, resulting in a characteristic fabric. All three types may melt again, and when this happens, new magma is formed, from which an igneous rock may once again solidify. Organic matter, such as coal, bitumen, oil, and natural gas, is linked mainly to organic-rich sedimentary rocks.[11]

To study all three types of rock, geologists evaluate the minerals of which they are composed and their other physical properties, such as texture and fabric.

Unlithified material

[edit]Geologists study unlithified materials (referred to as superficial deposits) that lie above the bedrock.[12] This study is often known as Quaternary geology, after the Quaternary period of geologic history, which is the most recent period of geologic time.[13]

Whole-Earth structure

[edit]Plate tectonics

[edit]

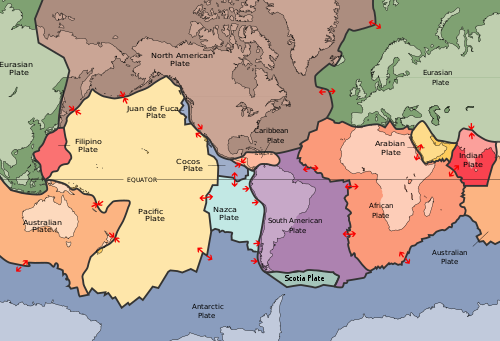

In the 1960s, it was discovered that the Earth's lithosphere, which includes the crust and rigid uppermost portion of the upper mantle, is separated into tectonic plates that move across the plastically deforming, solid, upper mantle, which is called the asthenosphere. This theory is supported by several types of observations, including seafloor spreading[15][16] and the global distribution of mountain terrain and seismicity.[17]

There is an intimate coupling between the movement of the plates on the surface and the convection of the mantle (that is, the heat transfer caused by the slow movement of ductile mantle rock). Thus, oceanic parts of plates and the adjoining mantle convection currents always move in the same direction – because the oceanic lithosphere is actually the rigid upper thermal boundary layer of the convecting mantle. This coupling between rigid plates moving on the surface of the Earth and the convecting mantle is called plate tectonics.[18]

The development of plate tectonics has provided a physical basis for many observations of the solid Earth. Long linear regions of geological features are explained as plate boundaries:[19]

- Mid-ocean ridges, high regions on the seafloor where hydrothermal vents and volcanoes exist, are seen as divergent boundaries, where two plates move apart.

- Arcs of volcanoes and earthquakes are theorized as convergent boundaries, where one plate subducts, or moves, under another.

- Transform boundaries, such as the San Andreas Fault system, are where plates slide horizontally past each other.

Plate tectonics has provided a mechanism for Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift,[20] in which the continents move across the surface of the Earth over geological time. They provided a driving force for crustal deformation, and a new setting for the observations of structural geology. The power of the theory of plate tectonics lies in its ability to combine all of these observations into a single theory of how the lithosphere moves over the convecting mantle, forming a "grand unifying theory of geology".[21][22]

Earth structure

[edit]

Advances in seismology, computer modeling, and mineralogy and crystallography at high temperatures and pressures give insights into the internal composition and structure of the Earth.[23]

Seismologists can use the arrival times of seismic waves to image the interior of the Earth. Early advances in this field showed the existence of a liquid outer core (where shear waves were not able to propagate) and a dense solid inner core. These advances led to the development of a layered model of the Earth, with a lithosphere (including crust) on top, the mantle below (separated within itself by seismic discontinuities at 410 and 660 kilometers), and the outer core and inner core below that.[24][25] Starting in the 1970s, seismologists have been able to use new techniques such as seismic full-waveform inversion to create detailed images of wave speeds inside the earth in the same way a doctor images a body in a CT scan. These images have led to a much more detailed view of the interior of the Earth, and have replaced the simplified layered model with a much more dynamic model.[26][24]

Mineralogists have been able to use the pressure and temperature data from the seismic and modeling studies alongside knowledge of the elemental composition of the Earth to reproduce these conditions in experimental settings and measure changes within the crystal structure.[27] These studies explain the chemical changes associated with the major seismic discontinuities in the mantle[28] and show the crystallographic structures expected in the inner core of the Earth.[29]

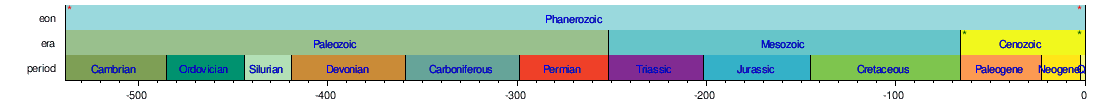

Geological time

[edit]The geological time scale encompasses the history of the Earth.[30] It is bracketed at the earliest by the dates of the first Solar System material at 4.567 Ga[31] (or 4.567 billion years ago) and the formation of the Earth at 4.54 Ga[32][33] (4.54 billion years), which is the beginning of the Hadean eon – a division of geological time. At the later end of the scale, it is marked by the present day (in the Holocene epoch).[34]

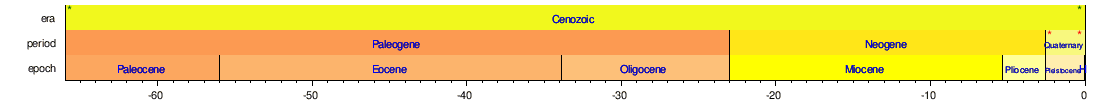

Timescale of the Earth

[edit]The following five timelines show the geologic time scale to scale. The first shows the entire time from the formation of Earth to the present, but this gives little space for the most recent eon. The second timeline shows an expanded view of the most recent eon. In a similar way, the most recent era is expanded in the third timeline, the most recent period is expanded in the fourth timeline, and the most recent epoch is expanded in the fifth timeline.

(Horizontal scale is millions of years for the above timelines; thousands of years for the timeline below)

Important milestones on Earth

[edit]

- 4.567 Ga (gigaannum: billion years ago): Solar system formation[31]

- 4.54 Ga: Accretion, or formation, of Earth[32][33]

- 4.5 Ga: Proposed Moon-forming impact[35]

- c. 4 Ga: End of Late Heavy Bombardment, the first life

- c. 3.5 Ga: Start of photosynthesis

- 3.2–2.3 Ga: Transition of crust from stagnant lid to plate tectonics[36]

- c. 2.3 Ga: Oxygenated atmosphere, first snowball Earth

- 1.8–1.5 Ga: Columbia supercontinent[37]

- 1,100–750 Ma (megaannum: million years ago): Rodinia supercontinent[37]

- 730–635 Ma: second snowball Earth

- 650–540 Ma: Pannotia supercontinent[37]

- 541±0.3 Ma: Cambrian explosion – vast multiplication of hard-bodied life; first abundant fossils; start of the Paleozoic

- c. 380 Ma: First vertebrate land animals

- 300–180 Ma: Pangaea supercontinent[37]

- 250 Ma: Permian-Triassic extinction – 90% of all land animals die; end of Paleozoic and beginning of Mesozoic

- 66 Ma: Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction – Dinosaurs die; end of Mesozoic and beginning of Cenozoic

- 45–35 Ma: Himalayas mountain range forms[38]

- c. 7 Ma: First hominins appear

- 3.9 Ma: First Australopithecus, direct ancestor to modern Homo sapiens, appear

- 200 ka (kiloannum: thousand years ago): First modern Homo sapiens appear in East Africa

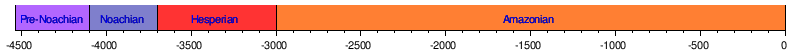

Timescale of the Moon

[edit]

The epochs of lunar history are based on the chronology of impact events, and they are named after defining major impacts. Hence, the Imbrian is named after the formation of the Mare Imbrium basin. The ages of older lunar basins can be dated based on the strength of their intrinsic magnetic field, since the early Moon had a magnetic field that faded over time. The ages of craters can be estimated by morphological and stratigraphic classifications, with younger craters overlapping older impacts and generally showing less impact wear.[39]

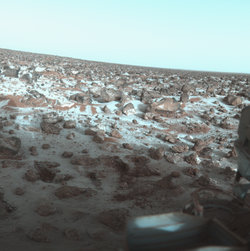

Timescale of Mars

[edit]

Epochs:

Dating methods

[edit]Relative dating

[edit]

Methods for relative dating were developed when geology first emerged as a natural science. Geologists still use the following principles today as a means to provide information about geological history and the timing of geological events.[40]

The principle of uniformitarianism states that the geological processes observed in operation that modify the Earth's crust at present have worked in much the same way over geological time.[41][42] A fundamental principle of geology advanced by the 18th-century Scottish physician and geologist James Hutton is that "the present is the key to the past." In Hutton's words: "the past history of our globe must be explained by what can be seen to be happening now."[43]

The principle of intrusive relationships concerns crosscutting intrusions. In geology, when an igneous intrusion cuts across a formation of sedimentary rock, it can be determined that the igneous intrusion is younger than the sedimentary rock.[44] Different types of intrusions include stocks, laccoliths, batholiths, sills and dikes.[45]

The principle of cross-cutting relationships pertains to the formation of faults and the age of the sequences through which they cut. Faults are younger than the rocks they cut; accordingly, if a fault is found that penetrates some formations but not those on top of it, then the formations that were cut are older than the fault, and the ones that are not cut must be younger than the fault.[42] Finding the key bed in these situations may help determine whether the fault is a normal fault or a thrust fault.[46]

The principle of inclusions and components states that, with sedimentary rocks, if inclusions (or clasts) are found in a formation, then the inclusions must be older than the formation that contains them.[42] For example, in sedimentary rocks, it is common for gravel from an older formation to be ripped up and included in a newer layer. A similar situation with igneous rocks occurs when xenoliths are found. These foreign bodies are picked up as magma or lava flows, and are incorporated, later to cool in the matrix. As a result, xenoliths are older than the rock that contains them.[47]

The principle of original horizontality states that the deposition of sediments occurs as essentially horizontal beds.[42] Observation of modern marine and non-marine sediments in a wide variety of environments supports this generalization (although cross-bedding is inclined, the overall orientation of cross-bedded units is horizontal).[46]

The principle of superposition states that a sedimentary rock layer in a tectonically undisturbed sequence is younger than the one beneath it and older than the one above it. Logically a younger layer cannot slip beneath a layer previously deposited.[42] This principle allows sedimentary layers to be viewed as a form of the vertical timeline, a partial or complete record of the time elapsed from deposition of the lowest layer to deposition of the highest bed.[46]

The principle of faunal succession is based on the appearance of fossils in sedimentary rocks. As organisms exist during the same period throughout the world, their presence or (sometimes) absence provides a relative age of the formations where they appear.[42] Based on principles that William Smith laid out almost a hundred years before the publication of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, the principles of succession developed independently of evolutionary thought. The principle becomes quite complex, however, given the uncertainties of fossilization, localization of fossil types due to lateral changes in habitat (facies change in sedimentary strata), and that not all fossils formed globally at the same time.[48]

Absolute dating

[edit]

Geologists use methods to determine the absolute age of rock samples and geological events. These may be used in conjunction with relative dating methods or to calibrate relative methods.[50]

At the beginning of the 20th century, advancement in geological science was facilitated by the ability to obtain accurate absolute dates to geological events using radioactive isotopes and other methods. This changed the understanding of geological time. Previously, geologists could only use fossils and stratigraphic correlation to date sections of rock relative to one another. With isotopic dates, it became possible to assign absolute ages to rock units, and these absolute dates could be applied to fossil sequences in which there was datable material, converting the old relative ages into new absolute ages.[51]

For many geological applications, isotope ratios of radioactive elements are measured in minerals that give the amount of time that has passed since a rock passed through its particular closure temperature: the point at which different radiometric isotopes stop diffusing into and out of the crystal lattice.[52][53] These are used in geochronologic and thermochronologic studies. The most suitable isotope systems for this purpose include uranium–lead, rubidium–strontium, and potassium–argon.[54] Uranium–thorium dating is used for dating calcium-carbonate.[55]

Dating of lava and volcanic ash layers found within a stratigraphic sequence can provide absolute age data for sedimentary rock units that do not contain radioactive isotopes and calibrate relative dating techniques.[56] These methods can be used to determine ages of pluton emplacement. Fractionation of the lanthanide series elements is used to compute ages since rocks were removed from the mantle.[57] Other methods are used for more recent events. Optically stimulated luminescence and cosmogenic radionuclide dating are used to date surfaces and/or erosion rates.[58][59] Dendrochronology can be used for the dating of landscapes.[60] Radiocarbon dating is used for geologically young materials containing organic carbon.[54]

Thermochemical techniques can be used to determine temperature profiles within the crust, the uplift of mountain ranges, and paleo-topography.[relevant?]

Geological development of an area

[edit]

A. Strike-slip faults occur when rock units slide past one another.

B. Normal faults occur when rocks are undergoing horizontal extension.

C. Reverse (or thrust) faults occur when rocks are undergoing horizontal shortening.

The geology of an area changes through time as rock units are deposited and inserted, and deformational processes alter their shapes and locations.

Rock units are first emplaced either by deposition onto the surface or intrusion into the overlying rock. Deposition can occur when sediments settle onto the surface of the Earth and later lithify into sedimentary rock,[61] or when as volcanic material such as volcanic ash[62] or lava flows blanket the surface. Igneous intrusions such as batholiths, laccoliths, dikes, and sills, push upwards into the overlying rock, and crystallize as they intrude.[45]

After the initial sequence of rocks has been deposited, the rock units can be deformed and/or metamorphosed. Deformation typically occurs as a result of horizontal shortening, horizontal extension, or side-to-side (strike-slip) motion. These structural regimes broadly relate to convergent boundaries, divergent boundaries, and transform boundaries, respectively, between tectonic plates.[63]: 7–9

When rock units are placed under horizontal compression, they shorten and become thicker. Because rock units, other than muds, do not significantly change in volume, this is accomplished in two primary ways: through faulting and folding. In the shallow crust, where brittle deformation can occur, thrust faults form, which causes the deeper rock to move on top of the shallower rock.[64] Because deeper rock is often older, as noted by the principle of superposition, this can result in older rocks moving on top of younger ones.[65] Movement along faults can result in folding, either because the faults are not planar or because rock layers are dragged along, forming drag folds as slip occurs along the fault.[63]: 57–58

Deeper in the Earth, rocks behave plastically and fold instead of faulting. These folds can either be those where the material in the center of the fold buckles upwards, creating "antiforms", or where it buckles downwards, creating "synforms". If the tops of the rock units within the folds remain pointing upwards, they are called anticlines and synclines, respectively. If some of the units in the fold are facing downward, the structure is called an overturned anticline or syncline, and if all of the rock units are overturned or the correct up-direction is unknown, they are simply called by the most general terms, antiforms, and synforms.[66]

Even higher pressures and temperatures during horizontal shortening can cause both folding and metamorphism of the rocks. This metamorphism causes changes in the mineral composition of the rocks; creates a foliation, or planar surface, that is related to mineral growth under stress. This can remove signs of the original textures of the rocks, such as bedding in sedimentary rocks, flow features of lavas, and crystal patterns in crystalline rocks.[67]

Extension causes the rock units as a whole to become longer and thinner. This is primarily accomplished through normal faulting and through the ductile stretching and thinning. Normal faults drop rock units that are higher below those that are lower. This typically results in younger units ending up below older units. Stretching of units can result in their thinning.[68] In fact, at one location within the Maria Fold and Thrust Belt, the entire sedimentary sequence of the Grand Canyon appears over a length of less than a meter.[citation needed] Rocks at the depth to be ductilely stretched are often metamorphosed. These stretched rocks can pinch into lenses, known as boudins, after the French word for "sausage" because of their visual similarity.

Where rock units slide past one another, strike-slip faults develop in shallow regions, and become shear zones at deeper depths where the rocks deform ductilely.

The addition of new rock units, both depositionally and intrusively, often occurs during deformation. Faulting and other deformational processes result in the creation of topographic gradients, causing material on the rock unit that is increasing in elevation to be eroded by hillslopes and channels. These sediments are deposited on the rock unit that is going down. Continual motion along the fault maintains the topographic gradient in spite of the movement of sediment and continues to create accommodation space for the material to deposit.

Deformational events are often associated with volcanism and igneous activity.[69] Volcanic ashes and lavas accumulate on the surface, and igneous intrusions enter from below. Dikes, long, planar igneous intrusions, enter along cracks, and therefore often form in large numbers in areas that are being actively deformed. This can result in the emplacement of dike swarms,[70] such as those that are observable across the Canadian shield,[71] or rings of dikes around the lava tube of a volcano.

All of these processes do not necessarily occur in a single environment and do not necessarily occur in a single order. The Hawaiian Islands, for example, consist almost entirely of layered basaltic lava flows. The sedimentary sequences of the mid-continental United States and the Grand Canyon in the southwestern United States contain almost-undeformed stacks of sedimentary rocks that have remained in place since Cambrian time. Other areas are much more geologically complex. In the southwestern United States, sedimentary, volcanic, and intrusive rocks have been metamorphosed, faulted, foliated, and folded. Even older rocks, such as the Acasta gneiss of the Slave craton in northwestern Canada, the oldest known rock in the world have been metamorphosed to the point where their origin is indiscernible without laboratory analysis.

These processes can occur in stages. In many places, the Grand Canyon in the southwestern United States being a very visible example, the lower rock units were metamorphosed and deformed, and then deformation ended and the upper, undeformed units were deposited. Although any amount of rock emplacement and rock deformation can occur, and they can occur any number of times, these concepts provide a guide to understanding the geological history of an area.

Investigative methods

[edit]

Geologists use a number of fields, laboratory, and numerical modeling methods to decipher Earth history and to understand the processes that occur on and inside the Earth. In typical geological investigations, geologists use primary information related to petrology (the study of rocks), stratigraphy (the study of sedimentary layers), and structural geology (the study of positions of rock units and their deformation). In many cases, geologists study modern soils, rivers, landscapes, and glaciers; investigate past and current life and biogeochemical pathways, and use geophysical methods to investigate the subsurface. Sub-specialities of geology may distinguish endogenous and exogenous geology.[72]

Field methods

[edit]

Geological field work varies depending on the task at hand. Typical fieldwork could consist of:

- Geological mapping[73]

- Structural mapping: identifying the locations of major rock units and the faults and folds that led to their placement there.

- Stratigraphic mapping: pinpointing the locations of sedimentary facies (lithofacies and biofacies) or the mapping of isopachs of equal thickness of sedimentary rock

- Surficial mapping: recording the locations of soils and surficial deposits

- Surveying of topographic features

- compilation of topographic maps[74]

- Work to understand change across landscapes, including:

- Patterns of erosion and deposition

- River-channel change through migration and avulsion

- Hillslope processes

- Subsurface mapping through geophysical methods[75]

- These methods include:

- They aid in:

- High-resolution stratigraphy

- Measuring and describing stratigraphic sections on the surface

- Well drilling and logging

- Biogeochemistry and geomicrobiology[76]

- Collecting samples to:

- determine biochemical pathways

- identify new species of organisms

- identify new chemical compounds

- and to use these discoveries to:

- understand early life on Earth and how it functioned and metabolized

- find important compounds for use in pharmaceuticals

- Collecting samples to:

- Paleontology: excavation of fossil material

- Collection of samples for geochronology and thermochronology[77]

- Glaciology: measurement of characteristics of glaciers and their motion[78]

Petrology

[edit]In addition to identifying rocks in the field (lithology), petrologists identify rock samples in the laboratory. Two of the primary methods for identifying rocks in the laboratory are through optical microscopy (such as with the petrographic microscope[79]) and by using an electron microprobe.[80] In an optical mineralogy analysis, petrologists analyze thin sections of rock samples using a petrographic microscope, where the minerals can be identified through their different properties in plane-polarized and cross-polarized light, including their birefringence, pleochroism, twinning, and interference properties with a conoscopic lens.[81] In the electron microprobe, individual locations are analyzed for their exact chemical compositions and variation in composition within individual crystals.[82] Stable[83] and radioactive isotope[84] studies provide insight into the geochemical evolution of rock units.

Petrologists can use fluid inclusion data[85] and perform high temperature and pressure physical experiments[86] to understand the temperatures and pressures at which different mineral phases appear, and how they change through igneous[87] and metamorphic processes. This research can be extrapolated to the field to understand metamorphic processes and the conditions of crystallization of igneous rocks.[88] This work can help to explain processes that occur within the Earth, such as subduction and magma chamber evolution.[89]

Structural geology

[edit]

Structural geologists use microscopic analysis of oriented thin sections of geological samples to observe the fabric within the rocks, which gives information about strain within the crystalline structure of the rocks.[90] They plot and combine measurements of geological structures to better understand the orientations of faults and folds to reconstruct the history of rock deformation in the area. In addition, they perform analog and numerical experiments of rock deformation in large and small settings.

The analysis of structures is often accomplished by plotting the orientations of various features onto stereonets. A stereonet is a stereographic projection of a sphere onto a plane, in which planes are projected as lines and lines are projected as points. These can be used to find the locations of fold axes, relationships between faults, and relationships between other geological structures.[91]

Among the most well-known experiments in structural geology are those involving orogenic wedges, which are zones in which mountains are built along convergent tectonic plate boundaries.[92] In the analog versions of these experiments, horizontal layers of sand are pulled along a lower surface into a back stop, which results in realistic-looking patterns of faulting and the growth of a critically tapered (all angles remain the same) orogenic wedge.[93] Numerical models work in the same way as these analog models, though they are often more sophisticated and can include patterns of erosion and uplift in the mountain belt.[94] This helps to show the relationship between erosion and the shape of a mountain range. These studies can give useful information about pathways for metamorphism through pressure, temperature, space, and time.[95]

Stratigraphy

[edit]

In the laboratory, stratigraphers analyze samples of stratigraphic sections that can be returned from the field, such as those from drill cores.[96] Stratigraphers analyze data from geophysical surveys that show the locations of stratigraphic units in the subsurface.[97] Geophysical data and well logs can be combined to produce a better view of the subsurface, and stratigraphers often use computer programs to do this in three dimensions.[98] Stratigraphers can then use these data to reconstruct ancient processes occurring on the surface of the Earth,[99] interpret past environments, and locate areas for water, coal, and hydrocarbon extraction.

In the laboratory, biostratigraphers analyze rock samples from outcrop and drill cores for the fossils found in them.[96] These fossils help scientists to date the core and to understand the depositional environment in which the rock units formed. Geochronologists precisely date rocks within the stratigraphic section to provide better absolute bounds on the timing and rates of deposition.[100] Magnetic stratigraphers look for signs of magnetic reversals in igneous rock units within the drill cores.[96] Other scientists perform stable-isotope studies on the rocks to gain information about past climate.[96]

Planetary geology

[edit]

With the advent of space exploration in the twentieth century, geologists have begun to look at other planetary bodies in the same ways that have been developed to study the Earth. This new field of study is called planetary geology (sometimes known as astrogeology) and relies on known geological principles to study other bodies of the Solar System. This is a major aspect of planetary science, and largely focuses on the terrestrial planets, icy moons, asteroids, comets, and meteorites. However, some planetary geophysicists study the giant planets and exoplanets.[101]

Although the Greek-language-origin prefix geo refers to Earth, "geology" is often used in conjunction with the names of other planetary bodies when describing their composition and internal processes: examples are "the geology of Mars" and "Lunar geology". Specialized terms such as selenology (studies of the Moon), areology (of Mars), hermesology (of Mercury), etc., are also in use.[102]

Although planetary geologists are interested in studying all aspects of other planets, a significant focus is to search for evidence of past or present life on other worlds. This has led to many missions whose primary or ancillary purpose is to examine planetary bodies for evidence of life.[103] One of these is the Phoenix lander, which analyzed Martian polar soil for water, chemical, and mineralogical constituents related to biological processes.[104]

Applied geology

[edit]

Economic geology

[edit]Economic geology is a branch of geology that deals with aspects of economic minerals that humankind uses to fulfill various needs. Economic minerals are those extracted profitably for various practical uses. Economic geologists help locate and manage the Earth's natural resources, such as petroleum and coal, as well as mineral resources, which include metals such as iron, copper, and uranium.[105]

Mining geology

[edit]Mining geology consists of the extractions of mineral and ore resources from the Earth. Some resources of economic interests include gemstones,[106] metals such as gold and copper,[107] and many industrial minerals such as asbestos, magnesite, perlite, mica, phosphates, zeolites, clay,[108] silica,[109] and pumice,[110] as well as elements such as sulfur[111] and helium.[112]

Petroleum geology

[edit]

Petroleum geologists study the locations of the subsurface of the Earth that can contain extractable hydrocarbons, especially petroleum and natural gas.[113] Because many of these reservoirs are found in sedimentary basins,[114] they study the formation of these basins, their sedimentary and tectonic evolution, and the present-day positions of the rock units.

Engineering geology

[edit]Engineering geology is the application of geological principles to engineering practice for the purpose of assuring that the geological factors affecting the location, design, construction, operation, and maintenance of engineering works are properly addressed.[115] Engineering geology is distinct from geological engineering, particularly in North America.

In the field of civil engineering, geological principles and analyses are used in order to ascertain the mechanical principles of the material on which structures are built. This allows tunnels to be built without collapsing, bridges and skyscrapers to be built with sturdy foundations, and buildings to be built that will not settle in clay and mud.[116]

Hydrology

[edit]Geology and geological principles can be applied to various environmental problems such as stream restoration, the restoration of brownfields, and the understanding of the interaction between natural habitat and the geological environment. Groundwater hydrology, or hydrogeology, is used to locate groundwater,[117] which can often provide a ready supply of uncontaminated water and is especially important in arid regions,[118] and to monitor the spread of contaminants in groundwater wells.[117][119]

Paleoclimatology

[edit]Geologists obtain data through stratigraphy, boreholes, core samples, and ice cores. Ice cores[120] and sediment cores[121] are used for paleoclimate reconstructions, which tell geologists about past and present temperature, precipitation, and sea level across the globe. These datasets are our primary source of information on global climate change outside of instrumental data.[122]

Natural hazards

[edit]

Geologists and geophysicists study natural hazards in order to enact safe building codes and warning systems that are used to prevent loss of property and life.[123] Examples of important natural hazards that are pertinent to geology (as opposed those that are mainly or only pertinent to meteorology) are:[124]

History

[edit]

The study of the physical material of the Earth dates back at least to ancient Greece when Theophrastus (372–287 BCE) wrote the work Peri Lithon (On Stones). During the Roman period, Pliny the Elder wrote in detail of the many minerals and metals, then in practical use – even correctly noting the origin of amber. Additionally, in the 4th century BCE Aristotle made critical observations of the slow rate of geological change. He observed the composition of the land and formulated a theory where the Earth changes at a slow rate and that these changes cannot be observed during one person's lifetime. Aristotle developed one of the first evidence-based concepts connected to the geological realm regarding the rate at which the Earth physically changes.[126][127]

Abu al-Rayhan al-Biruni (973–1048 CE) was one of the earliest Persian geologists, whose works included the earliest writings on the geology of India, hypothesizing that the Indian subcontinent was once a sea.[128] Drawing from Greek and Indian scientific literature that were not destroyed by the Muslim conquests, the Persian scholar Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 981–1037) proposed detailed explanations for the formation of mountains, the origin of earthquakes, and other topics central to modern geology, which provided an essential foundation for the later development of the science.[129][130] In China, the polymath Shen Kuo (1031–1095) formulated a hypothesis for the process of land formation: based on his observation of fossil animal shells in a geological stratum in a mountain hundreds of miles from the ocean, he inferred that the land was formed by the erosion of the mountains and by deposition of silt.[131]

Georgius Agricola (1494–1555) published his groundbreaking work De Natura Fossilium in 1546 and is seen as the founder of geology as a scientific discipline.[132]

Nicolas Steno (1638–1686) is credited with the law of superposition, the principle of original horizontality, and the principle of lateral continuity: three defining principles of stratigraphy.[133]

The word geology was first used by Ulisse Aldrovandi in 1603,[134][135] then by Jean-André Deluc in 1778[136] and introduced as a fixed term by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure in 1779.[137][138] The word is derived from the Greek γῆ, gê, meaning "earth" and λόγος, logos, meaning "speech".[139] But according to another source, the word "geology" comes from a Norwegian, Mikkel Pedersøn Escholt (1600–1669), who was a priest and scholar. Escholt first used the definition in his book titled, Geologia Norvegica (1657).[140][141]

William Smith (1769–1839) drew some of the first geological maps and began the process of ordering rock strata (layers) by examining the fossils contained in them.[125]

In 1763, Mikhail Lomonosov published his treatise On the Strata of Earth.[142] His work was the first narrative of modern geology, based on the unity of processes in time and explanation of the Earth's past from the present.[143]

James Hutton (1726–1797) is often viewed as the first modern geologist.[144] In 1785 he presented a paper entitled Theory of the Earth to the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In his paper, he explained his theory that the Earth must be much older than had previously been supposed to allow enough time for mountains to be eroded and for sediments to form new rocks at the bottom of the sea, which in turn were raised up to become dry land. Hutton published a two-volume version of his ideas in 1795.[145]

Followers of Hutton were known as Plutonists because they believed that some rocks were formed by vulcanism, which is the deposition of lava from volcanoes, as opposed to the Neptunists, led by Abraham Werner, who believed that all rocks had settled out of a large ocean whose level gradually dropped over time.[146]

The first geological map of the U.S. was produced in 1809 by William Maclure.[147] In 1807, Maclure commenced the self-imposed task of making a geological survey of the United States. Almost every state in the Union was traversed and mapped by him, the Allegheny Mountains being crossed and recrossed some 50 times.[148] The results of his unaided labours were submitted to the American Philosophical Society in a memoir entitled Observations on the Geology of the United States explanatory of a Geological Map, and published in the Society's Transactions, together with the nation's first geological map.[149] This antedates William Smith's geological map of England by six years, although it was constructed using a different classification of rocks.

Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875) first published his famous book, Principles of Geology,[150] in 1830. This book, which influenced the thought of Charles Darwin, successfully promoted the doctrine of uniformitarianism. This theory states that slow geological processes have occurred throughout the Earth's history and are still occurring today. In contrast, catastrophism is the theory that Earth's features formed in single, catastrophic events and remained unchanged thereafter. Though Hutton believed in uniformitarianism, the idea was not widely accepted at the time.

Much of 19th-century geology revolved around the question of the Earth's exact age. Estimates varied from a few hundred thousand to billions of years.[151] By the early 20th century, radiometric dating allowed the Earth's age to be estimated at two billion years. The awareness of this vast amount of time opened the door to new theories about the processes that shaped the planet.

Some of the most significant advances in 20th-century geology have been the development of the theory of plate tectonics in the 1960s and the refinement of estimates of the planet's age. Plate tectonics theory arose from two separate geological observations: seafloor spreading and continental drift. The theory revolutionized the Earth sciences. Today the Earth is known to be approximately 4.5 billion years old.[33]

-

Georgius Agricola, German mineralogist, founder of geology as a scientific field

-

Mikhail Lomonosov, Russian polymath, author of the first systematic treatise in scientific geology (1763)

-

The volcanologist David A. Johnston 13 hours before his death at the

1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens

Fields or related disciplines

[edit]- Earth system science

- Economic geology

- Engineering geology

- Environmental geology

- Environmental science

- Geoarchaeology

- Geochemistry

- Geochronology

- Geodetics

- Geography

- Geological engineering

- Geological modelling

- Geometallurgy

- Geomicrobiology

- Geomorphology

- Geomythology

- Geophysics

- Glaciology

- Historical geology

- Hydrogeology

- Meteorology

- Mineralogy

- Oceanography

- Paleoclimatology

- Paleontology

- Petrology

- Petrophysics

- Planetary geology

- Plate tectonics

- Regional geology

- Sedimentology

- Seismology

- Soil science

- Speleology

- Stratigraphy

- Structural geology

- Systems geology

- Tectonics

- Volcanology

See also

[edit]- Glossary of geology

- Geoprofessions – Group of technical disciplines

- Geotourism – Tourism associated with geological attractions and destinations

- Index of geology articles – Alphabetical listing of Wikipedia articles on Geology topics

- International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) – International non-governmental organization

- List of individual rocks – Named rocks

- Outline of geology – Scientific study of Earth's physical composition

- Timeline of geology – Chronological list of notable events in the history of the science of geology

References

[edit]- ^ "What is geology?". The Geological Society. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "geology". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ γῆ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Gunten, Hans R. von (1995). "Radioactivity: A Tool to Explore the Past" (PDF). Radiochimica Acta. 70–71 (s1): 305–413. doi:10.1524/ract.1995.7071.special-issue.305. ISSN 2193-3405. S2CID 100441969. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-12-12. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ^ Nickel, Ernest H. (1995). "Definition of a mineral". Mineralogical Magazine. 59 (397): 767–768. doi:10.1180/minmag.1995.059.397.20.

- ^ "Mineral Identification Tests". Geoman's Mineral ID Tests. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ Upadhyay, R. K. (2025). "Rocks and Their Formation". Geology and Mineral Resources. Springer Geology. Singapore: Springer. pp. 351–421. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-0598-9_6. ISBN 978-981-96-0597-2.

- ^ "What are igneous rocks?". USGS. 2025-07-29. Retrieved 2025-10-06.

- ^ National Roster of Scientific and Specialized Personnel (U.S.) (1945). Handbook of Descriptions of Specialized Fields in Geology. Bureau of Placement, War Manpower Commission. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Guéguen, Yves; Palciauskas, Victor (1994). Introduction to the Physics of Rocks. Princeton University Press: Princeton University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-691-03452-2.

- ^ Staplin, F. L. (1969). "Sedimentary organic matter, organic metamorphism, and oil and gas occurrence". Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology. 17 (1): 47–66. doi:10.35767/gscpgbull.17.1.047 (inactive 6 October 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2025 (link) - ^ "Geologic Mapping Program: Surficial Geologic Maps". des.nh.gov. New Hampshire Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2016-02-16. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- ^ Oldroyd, D. R.; Grapes, R. H. (2008). "Contributions to the history of geomorphology and Quaternary geology: an introduction". In Grapes, R. H.; et al. (eds.). History of Geomorphology and Quaternary Geology. Special publication. Vol. 301. Geological Society of London. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-1-86239-255-7.

- ^ van Dijk, Jan Pieter. "OCRE GeoMap". OCRE Geoscience Services. Retrieved 2025-10-05.

- ^ Hess, H. H. (November 1, 1962). "History Of Ocean Basins". In Engel, A. E. J.; James, Harold L.; Leonard, B. F. (eds.). Petrologic studies: a volume in honor of A. F. Buddington. Geological Society of America. pp. 599–620. Archived from the original on 2009-10-16. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Kious, Jacquelyne; Tilling, Robert I. (1996). "Developing the Theory". This Dynamic Earth: The Story of Plate Tectonics. Kiger, Martha, Russel, Jane (Online ed.). Reston: United States Geological Survey. ISBN 978-0-16-048220-5. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ^ Dewey, John F. (May 1972). "Plate Tectonics". Scientific American. 226 (5): 56–72. Bibcode:1972SciAm.226e..56D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0572-56. JSTOR 24927338.

- ^ Schubert, Gerald; et al. (2001). Turcotte, Donald Lawson; Olson, Peter (eds.). Mantle Convection in the Earth and Planets. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-79836-5.

- ^ Kious, Jacquelyne; Tilling, Robert I. (1996). "Understanding Plate Motions". This Dynamic Earth: The Story of Plate Tectonics. Kiger, Martha, Russel, Jane (Online ed.). Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. ISBN 978-0-16-048220-5. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ^ Wegener, A. (1999). Origin of continents and oceans. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-61708-4.

- ^ Brusatte, Stephan S. (2009). "Plate Tectonics". In Birx, H. James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Time: Science, Philosophy, Theology, & Culture. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-5063-1993-3.

- ^ Ervin-Blankenheim, Elisabeth (August 2021). "Plate Tectonics: Oceans, Continents, Plates, and How They Interact". Song of the Earth: Understanding Geology and Why It Matters. Oxford University Press. pp. 114–136. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197502464.003.0007. ISBN 978-0-19-750249-5.

- ^ Choudhury, N.; Chaplot, S. L. (2008). "Inelastic neutron scattering and lattice dynamics: perspectives and challenges in mineral physics". In Liang, Liyuan; et al. (eds.). Neutron Applications in Earth, Energy and Environmental Sciences. Neutron Scattering Applications and Techniques. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 145–188. ISBN 978-0-387-09416-8.

- ^ a b Fichtner, Andreas (2010). "Preliminaries". Full Seismic Waveform Modelling and Inversion. Advances in Geophysical and Environmental Mechanics and Mathematics. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-15807-0.

- ^ Goes, Saskia (2022). "Compositional heterogeneity in the mantle transition zone". Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 3 (8): 533-550. Bibcode:2022NRvEE...3..533G. doi:10.1038/s43017-022-00312-w. hdl:1721.1/148207.

- ^ Tromp, Jeroen (2020). "Seismic wavefield imaging of Earth's interior across scales". Nature Reviews Earth & Environment Volume. 1: 40–53. doi:10.1038/s43017-019-0003-8.

- ^ van Zelst, Iris; et al. (2022). "101 geodynamic modelling: how to design, interpret, and communicate numerical studies of the solid Earth". Solid Earth. 13 (3). European Geosciences Union: 583–637. Bibcode:2022SolE...13..583V. doi:10.5194/se-13-583-2022.

- ^ Goes, Saskia; et al. (2022). "Compositional heterogeneity in the mantle transition zone". Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 3 (8): 533–550. Bibcode:2022NRvEE...3..533G. doi:10.1038/s43017-022-00312-w.

- ^ Belonoshko, Anatoly B.; et al. (May 23, 2022). "Elastic properties of body-centered cubic iron in Earth's inner core". Physical Review B. 105 (18) L180102. Bibcode:2022PhRvB.105r0102B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.105.L180102.

- ^ "International Commission on Stratigraphy". stratigraphy.org. September 20, 2005. Archived from the original on 2005-09-20. Retrieved 2005-09-20.

- ^ a b Amelin, Y. (2002). "Lead Isotopic Ages of Chondrules and Calcium-Aluminum-Rich Inclusions". Science. 297 (5587): 1678–1683. Bibcode:2002Sci...297.1678A. doi:10.1126/science.1073950. PMID 12215641. S2CID 24923770.

- ^ a b Patterson, C. (1956). "Age of Meteorites and the Earth". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 10 (4): 230–237. Bibcode:1956GeCoA..10..230P. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(56)90036-9.

- ^ a b c Dalrymple, G. Brent (1994). The age of the earth. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2331-2.

- ^ Gradstein, Felix; et al. (2020). Geologic Time Scale 2020. Vol. 1. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-824361-9.

- ^ Gabriel, Travis S. J.; Cambioni, Saverio (2023). "The Role of Giant Impacts in Planet Formation". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 51: 671–695. arXiv:2312.15018. Bibcode:2023AREPS..51..671G. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-031621-055545.

- ^ Brown, Michael; Johnson, Tim; Gardiner, Nicholas J. (2020). "Plate Tectonics and the Archean Earth". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 48: 291–320. Bibcode:2020AREPS..48..291B. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-081619-052705.

- ^ a b c d Vázquez, M.; et al. (2010). The Earth as a Distant Planet: A Rosetta Stone for the Search of Earth-Like Worlds. Astronomy and Astrophysics Library. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-1684-6.

- ^ Valdiya, K. S. (2002). "Emergence and evolution of Himalaya: reconstructing history in the light of recent studies". Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment. 26 (3): 360–399. doi:10.1191/0309133302pp342 (inactive 6 October 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2025 (link) - ^ Ćuk, Matija (March 2012). "Chronology and sources of lunar impact bombardment". Icarus. 218 (1): 69–79. arXiv:1112.0046. Bibcode:2012Icar..218...69C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.11.031.

- ^ Jain, Sreepat (2013). Fundamentals of Physical Geology. Springer Geology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 98–100. ISBN 978-81-322-1539-4.

- ^ Hooykaas, Reijer (1963). Natural Law and Divine Miracle: The Principle of Uniformity in Geology, Biology, and Theology. Leiden: EJ Brill.

- ^ a b c d e f West, Terry R.; Shakoor, Abdul (2018). Geology Applied to Engineering (Second ed.). Waveland Press. pp. 193–198. ISBN 978-1-4786-3722-6.

- ^ Levin, Harold L. (2010). The earth through time (9th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-470-38774-0.

- ^ Stanley, Steven M. (2004). Earth System History (Second ed.). W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7167-3907-4.

- ^ a b Hunt, Roy E. (2005). Geotechnical Engineering Investigation Handbook (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 418–422. ISBN 978-1-4200-3915-3.

- ^ a b c Olsen, Paul E. (2001). "Steno's Principles of Stratigraphy". Dinosaurs and the History of Life. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ "Xenolith". Education. National Geographic Society. April 24, 2024. Retrieved 2025-10-09.

- ^ As recounted in: Winchester, Simon (2001). The Map that Changed the World. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 59–91.

- ^ Macdougall, Doug (2011). Why Geology Matters: Decoding the Past, Anticipating the Future. University of California Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-520-94892-1.

- ^ Tucker, R. D.; Bradley, D. C.; Ver Straeten, C. A.; Harris, A. G.; Ebert, J. R.; McCutcheon, S. R. (1998). "New U–Pb zircon ages and the duration and division of Devonian time" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 158 (3–4): 175–186. Bibcode:1998E&PSL.158..175T. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.498.7372. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(98)00050-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-26. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ^ White, William M. (2023). Isotope Geochemistry (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-1-119-72994-5.

- ^ Rollinson, Hugh R. (1996). Using geochemical data evaluation, presentation, interpretation. Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-06701-1.

- ^ Faure, Gunter (1998). Principles and applications of geochemistry: a comprehensive textbook for geology students. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-02-336450-1.

- ^ a b Nance, Damian; Murphy, Brendan E. (2016). Physical Geology Today. Oxford University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-19-996555-7.

- ^ Edwards, R. L. (January 2003). "Uranium-series Dating of Marine and Lacustrine Carbonates". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 52 (1): 363–405. Bibcode:2003RvMG...52..363E. doi:10.2113/0520363.

- ^ Miall, Andrew D. (2010). The Geology of Stratigraphic Sequences (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 420–425. ISBN 978-3-642-05027-5.

- ^ Philpotts, Anthony R.; Ague, Jay J. (2022). Principles of Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-108-49288-1.

- ^ Rhodes, Edward J. (2011). "Optically Stimulated Luminescence Dating of Sediments over the Past 200,000 Years". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 39: 461–488. Bibcode:2011AREPS..39..461R. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-040610-133425.

- ^ Ivy-Ochs, Susan; Kober, Florian (2008). "Surface exposure dating with cosmogenic nuclides". E&G Quaternary Science Journal. 57 (1/2): 179–209. doi:10.3285/eg.57.1-2.7.

- ^ Shroder, Jr., John F. (1980). "Dendrogeomorphology: review and new techniques of tree-ring dating". Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment. 4 (2): 161–188. Bibcode:1980PrPG....4..161S. doi:10.1177/030913338000400202.

- ^ Spellman, Frank R. (2009). Geology for Nongeologists. Science for Nonscientists. Vol. 6. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. ISBN 978-0-86587-185-4.

- ^ Asniar, Novi; et al. (June 26, 2019). Tuff as rock and soil: Review of the literature on tuff geotechnical, chemical and mineralogical properties around the world and in Indonesia. Exploring Resources, Process and Design for Sustainable Urban Development; Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Engineering, Technology, and Industrial Application (ICETIA) 2018. AIP Conference Procedings. Vol. 2114. AIP Publishing LLC. p. 050022. doi:10.1063/1.5112466.

- ^ a b Twiss, Robert J.; Moores, Eldridge M. (1992). Structural Geology. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-2252-6.

- ^ Greeley, Ronald (2013). Introduction to Planetary Geomorphology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–37. ISBN 978-0-521-86711-5.

- ^ Prost, Gary; Prost, Benjamin (2017). The Geology Companion: Essentials for Understanding the Earth. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4987-5609-9.

- ^ Davis, George H.; et al. (2011). Structural Geology of Rocks and Regions (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 344–354. ISBN 978-0-471-15231-6.

- ^ Christiansen, Eric H.; Hamblin, W. Kenneth (2014). Dynamic Earth: An Introduction to Physical Geology. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-4496-5902-8.

- ^ Price, Neville J.; Cosgrove, John W. (1990). Analysis of Geological Structures. Cambridge University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-521-31958-4.

- ^ Biggs, J.; et al. (2014). "Global link between deformation and volcanic eruption quantified by satellite imagery". Nature Communications. 5 3471. doi:10.1038/ncomms4471.

- ^ Walker, George P. L. (December 1999). "Volcanic rift zones and their intrusion swarms". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 94 (1–4): 21–34. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(99)00096-7.

- ^ Fahrig, W. F.; et al. (August 1965). "Paleomagnetism of Diabase Dykes of the Canadian Shield". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2 (4): 278–298. doi:10.1139/e65-023.

- ^ Compare: Hansen, Jens Morten (2009-01-01). "On the origin of natural history: Steno's modern, but forgotten philosophy of science". In Rosenberg, Gary D. (ed.). The Revolution in Geology from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. Geological Society of America Memoir. Vol. 203. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America (published 2009). p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8137-1203-1. Archived from the original on 2017-01-20. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

[...] the historic dichotomy between 'hard rock' and 'soft rock' geologists, i.e. scientists working mainly with endogenous and exogenous processes, respectively [...] endogenous forces mainly defining the developments below Earth's crust and the exogenous forces mainly defining the developments on top of and above Earth's crust.

- ^ Compton, Robert R. (1985). Geology in the field. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-82902-7.

- ^ "USGS Topographic Maps". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2009-04-12. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

- ^ Burger, H. Robert; Sheehan, Anne F.; Jones, Craig H. (2006). Introduction to applied geophysics : exploring the shallow subsurface. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-92637-8.

- ^ Krumbein, Wolfgang E., ed. (1978). Environmental biogeochemistry and geomicrobiology. Ann Arbor, MI: Ann Arbor Science Publ. ISBN 978-0-250-40218-2.

- ^ McDougall, Ian; Harrison, T. Mark (1999). Geochronology and thermochronology by the ♯°Ar/©Ar method. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510920-7.

- ^ Hubbard, Bryn; Glasser, Neil (2005). Field techniques in glaciology and glacial geomorphology. Chichester, England: J. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-84426-7.

- ^ Klein, Cornelis; Philpotts, Anthony (2016). "Minerals and Rocks Observed under the Polarizing Optical Microscope". Earth Materials: Introduction to Mineralogy and Petrology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 135–158. doi:10.1017/9781316652909.008. ISBN 978-1-316-60885-2.

- ^ Llovet, Xavier; et al. (February 2021). "Electron probe microanalysis: A review of recent developments and applications in materials science and engineering". Progress in Materials Science. 116 100673. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100673.

- ^ Nesse, William D. (1991). Introduction to optical mineralogy. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506024-9.

- ^ Morton, A. C. (1985). "A new approach to provenance studies: electron microprobe analysis of detrital garnets from Middle Jurassic sandstones of the northern North Sea". Sedimentology. 32 (4): 553–566. Bibcode:1985Sedim..32..553M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.1985.tb00470.x.

- ^ Zheng, Y.; Fu, Bin; Gong, Bing; Li, Long (2003). "Stable isotope geochemistry of ultrahigh pressure metamorphic rocks from the Dabie–Sulu orogen in China: implications for geodynamics and fluid regime". Earth-Science Reviews. 62 (1): 105–161. Bibcode:2003ESRv...62..105Z. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00133-2.

- ^ Condomines, M.; Tanguy, J.; Michaud, V. (1995). "Magma dynamics at Mt Etna: Constraints from U-Th-Ra-Pb radioactive disequilibria and Sr isotopes in historical lavas". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 132 (1): 25–41. Bibcode:1995E&PSL.132...25C. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(95)00052-E.

- ^ Shepherd, T. J.; Rankin, A. H.; Alderton, D. H. M. (1985). "A practical guide to fluid inclusion studies". Mineralogical Magazine. 50 (356). Glasgow: Blackie: 352. Bibcode:1986MinM...50..352P. doi:10.1180/minmag.1986.050.356.32. ISBN 978-0-412-00601-2.

- ^ Sack, Richard O.; Walker, David; Carmichael, Ian S.E. (1987). "Experimental petrology of alkalic lavas: constraints on cotectics of multiple saturation in natural basic liquids". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 96 (1): 1–23. Bibcode:1987CoMP...96....1S. doi:10.1007/BF00375521. S2CID 129193823.

- ^ McBirney, Alexander R. (2007). Igneous petrology. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-3448-0.

- ^ Spear, Frank S. (1995). Metamorphic phase equilibria and pressure-temperature-time paths. Washington, DC: Mineralogical Soc. of America. ISBN 978-0-939950-34-8.

- ^ Deegan, F. M.; Troll, V. R.; Freda, C.; Misiti, V.; Chadwick, J. P.; McLeod, C. L.; Davidson, J. P. (May 2010). "Magma–Carbonate Interaction Processes and Associated CO2 Release at Merapi Volcano, Indonesia: Insights from Experimental Petrology". Journal of Petrology. 51 (5): 1027–1051. doi:10.1093/petrology/egq010. ISSN 1460-2415.

- ^ Passchier, Cees W.; Trouw, Rudolph A. J. (2005). Microtectonics (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-3-540-64003-5.

- ^ Pollard, David D.; Martel, Stephen J. (2020). Structural Geology: A Quantitative Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-1-108-66145-4.

- ^ Dahlen, F. A. (1990). "Critical Taper Model of Fold-and-Thrust Belts and Accretionary Wedges". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 18: 55–99. Bibcode:1990AREPS..18...55D. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.18.050190.000415.

- ^ Gutscher, M; Kukowski, Nina; Malavieille, Jacques; Lallemand, Serge (1998). "Material transfer in accretionary wedges from analysis of a systematic series of analog experiments". Journal of Structural Geology. 20 (4): 407–416. Bibcode:1998JSG....20..407G. doi:10.1016/S0191-8141(97)00096-5.

- ^ Koons, P. O. (1995). "Modeling the Topographic Evolution of Collisional Belts". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 23: 375–408. Bibcode:1995AREPS..23..375K. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.23.050195.002111.

- ^ Dahlen, F. A.; Suppe, J.; Davis, D. (1984). "Mechanics of Fold-and-Thrust Belts and Accretionary Wedges: Cohesive Coulomb Theory". Journal of Geophysical Research. 89 (B12): 10087–10101. Bibcode:1984JGR....8910087D. doi:10.1029/JB089iB12p10087.

- ^ a b c d Hodell, David A.; Benson, Richard H.; Kent, Dennis V.; Boersma, Anne; Rakic-El Bied, Kruna (1994). "Magnetostratigraphic, Biostratigraphic, and Stable Isotope Stratigraphy of an Upper Miocene Drill Core from the Salé Briqueterie (Northwestern Morocco): A High-Resolution Chronology for the Messinian Stage". Paleoceanography. 9 (6): 835–855. Bibcode:1994PalOc...9..835H. doi:10.1029/94PA01838.

- ^ Bally, A. W., ed. (1987). Atlas of seismic stratigraphy. Tulsa, Oklahoma: American Association of Petroleum Geologists. ISBN 978-0-89181-033-9.

- ^ Fernández, O.; Muñoz, J. A.; Arbués, P.; Falivene, O.; Marzo, M. (2004). "Three-dimensional reconstruction of geological surfaces: An example of growth strata and turbidite systems from the Ainsa basin (Pyrenees, Spain)". AAPG Bulletin. 88 (8): 1049–1068. Bibcode:2004BAAPG..88.1049F. doi:10.1306/02260403062.

- ^ Poulsen, Chris J.; Flemings, Peter B.; Robinson, Ruth A. J.; Metzger, John M. (1998). "Three-dimensional stratigraphic evolution of the Miocene Baltimore Canyon region: Implications for eustatic interpretations and the systems tract model". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 110 (9): 1105–1122. Bibcode:1998GSAB..110.1105P. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1998)110<1105:TDSEOT>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Toscano, M.; Lundberg, Joyce (1999). "Submerged Late Pleistocene reefs on the tectonically-stable S.E. Florida margin: high-precision geochronology, stratigraphy, resolution of Substage 5a sea-level elevation, and orbital forcing". Quaternary Science Reviews. 18 (6): 753–767. Bibcode:1999QSRv...18..753T. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(98)00077-8.

- ^ Laughlin, Gregory; Lissauer, Jack (2015). "Exoplanetary Geophysics: An Emerging Discipline". Treatise on Geophysics. pp. 673–694. arXiv:1501.05685. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53802-4.00186-X. ISBN 978-0-444-53803-1. S2CID 118743781.

- ^ Nayak, V. K. (1971). "Geoplanetology: A New Term for Geology of the Planets Including the Moon: Reply Available to Purchase". GSA Bulletin. 82 (8): 2381–2382. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1971)82[2381:GANTFG]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Dick, Steven J. (June 2006). "NASA and the search for life in the universe". Endeavour. 30 (2): 71–75. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2006.02.005.

- ^ Stoker, Carol R.; et al. (June 2010). "Habitability of the Phoenix landing site". Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (E6). doi:10.1029/2009JE003421.

- ^ Jébrak, Michael (June 2006). "Economic Geology: Then and Now". Geoscience Canada. 33 (2): 49–96. Retrieved 2025-10-09.

- ^ Groat, Lee A.; Laurs, Brendan M. (2009). "Gem Formation, Production, and Exploration: Why Gem Deposits Are Rare and What is Being Done to Find Them". Elements. 5 (3): 153–158. doi:10.2113/gselements.5.3.153.

- ^ Meyer, Charles (March 22, 1985). "Ore Metals Through Geologic History". Science. 227 (4693): 1421–1428. doi:10.1126/science.227.4693.1421.

- ^ Kucera, M. (2013). Industrial Minerals and Rocks. Developments in Economic Geology. Vol. 18. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-59750-2.

- ^ Peters, S. G.; et al. (2005). Geology and nonfuel mineral deposits of Asia and the Pacific. U. S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2025-10-09.

- ^ Hoffer, J. M. (1994). Pumice and pumicite in New Mexico (PDF). New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources. Vol. 140. Retrieved 2025-10-09.

- ^ Pawlowski, S.; et al. (April 1979). "Geology and genesis of the Polish sulfur deposits". Economic Geology. 74 (2). doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.74.2.475.

- ^ Wilson, Ross W.; Newsom, H. R. "Helium: Its Extraction and Purification". Journal of Petroleum Technology. 20 (4): 341–344. doi:10.2118/1952-PA.

- ^ Aminzadeh, Fred; Dasgupta, Shivaji N. (2013). "Fundamentals of Petroleum Geology". Developments in Petroleum Science. Vol. 60. Elsevier. pp. 15–36. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-50662-7.00002-0.

- ^ Selley, Richard C. (1998). Elements of petroleum geology. San Diego, California: Academic Press. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-12-636370-8.

- ^ Price, David George (2009). de Freitas, Michael (ed.). Engineering Geology: Principles and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-29249-4.

- ^ Das, Braja M. (2006). Principles of geotechnical engineering. England: Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-55144-5.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Pixie A.; Helsel, Dennis R. (1995). "Effects of Agriculture on Ground-Water Quality in Five Regions of the United States". Ground Water. 33 (2): 217–226. Bibcode:1995GrWat..33..217H. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6584.1995.tb00276.x. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ Seckler, David; Barker, Randolph; Amarasinghe, Upali (1999). "Water Scarcity in the Twenty-first Century". International Journal of Water Resources Development. 15 (1–2): 29–42. Bibcode:1999IJWRD..15...29S. doi:10.1080/07900629948916.

- ^ Welch, Alan H.; Lico, Michael S.; Hughes, Jennifer L. (1988). "Arsenic in Ground Water of the Western United States". Ground Water. 26 (3): 333–347. Bibcode:1988GrWat..26..333W. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6584.1988.tb00397.x.

- ^ Barnola, J. M.; Raynaud, D.; Korotkevich, Y. S.; Lorius, C. (1987). "Vostok ice core provides 160,000-year record of atmospheric CO2". Nature. 329 (6138): 408–414. Bibcode:1987Natur.329..408B. doi:10.1038/329408a0. S2CID 4268239.

- ^ Colman, S. M.; Jones, G. A.; Forester, R. M.; Foster, D. S. (1990). "Holocene paleoclimatic evidence and sedimentation rates from a core in southwestern Lake Michigan". Journal of Paleolimnology. 4 (3): 269. Bibcode:1990JPall...4..269C. doi:10.1007/BF00239699. S2CID 129496709.

- ^ Jones, P. D.; Mann, M. E. (6 May 2004). "Climate over past millennia" (PDF). Reviews of Geophysics. 42 (2): RG2002. Bibcode:2004RvGeo..42.2002J. doi:10.1029/2003RG000143. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "USGS Natural Hazards Gateway". usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-09-23. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ^ Paul, Bimal Kanti (2011). Environmental Hazards and Disasters: Contexts, Perspectives and Management. John Wiley & Sons. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-470-66001-0.

- ^ a b Winchester, Simon (2002). The map that changed the world: William Smith and the birth of modern geology. New York: Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-093180-3.

- ^ Moore, Ruth (1956). The Earth We Live On. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 13.

- ^ Aristotle. Meteorology. Book 1, Part 14.

- ^ Asimov, M. S.; Bosworth, Clifford Edmund, eds. (1992). The Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century : The Achievements. History of civilizations of Central Asia. pp. 211–214. ISBN 978-92-3-102719-2.

- ^ Toulmin, S.; Goodfield, J. (1965). The Ancestry of science: The Discovery of Time. London, England: Hutchinson & Company. p. 64.

- ^ Al-Rawi, Munin M. (November 2002). The Contribution of Ibn Sina (Avicenna) to the development of Earth Sciences (PDF) (Report). Manchester, UK: Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation. Publication 4039. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-03. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. pp. 603–604. ISBN 978-0-521-31560-9.

- ^ "Georgius Agricola (1494–1555)".

- ^ Shellnutt, Gregory; et al. (2024). "Introduction to methods and applications of geochronology: A perspective on geological time". Methods and Applications of Geochronology. Elsevier. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-443-18802-2.

- ^ From his will (Testamento d'Ullisse Aldrovandi) of 1603, which is reproduced in: Fantuzzi, Giovanni, Memorie della vita di Ulisse Aldrovandi, medico e filosofo bolognese … (Bologna, Italy: Lelio dalla Volpe, 1774). From p. 81: Archived 2017-02-16 at the Wayback Machine " … & anco la Giologia, ovvero de Fossilibus; … " ( … and likewise geology, or [the study] of things dug from the earth; … )

- ^ Vai, Gian Battista; Cavazza, William (2003). Four centuries of the word geology: Ulisse Aldrovandi 1603 in Bologna. Minerva. ISBN 978-88-7381-056-8.

- ^ Deluc, Jean André de, Lettres physiques et morales sur les montagnes et sur l'histoire de la terre et de l'homme. … [Physical and moral letters on mountains and on the history of the Earth and man. … ], vol. 1 (Paris, France: V. Duchesne, 1779), pp. 4, 5, and 7. From p. 4: Archived 2018-11-22 at the Wayback Machine "Entrainé par les liaisons de cet objet avec la Géologie, j'entrepris dans un second voyage de les développer à SA MAJESTÉ; … " (Driven by the connections between this subject and geology, I undertook a second voyage to develop them for Her Majesty [viz, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland]; … ) From p. 5: Archived 2018-11-22 at the Wayback Machine "Je vis que je faisais un Traité, et non une equisse de Géologie." (I see that I wrote a treatise, and not a sketch of geology.) From the footnote on p. 7: Archived 2018-11-22 at the Wayback Machine "Je répète ici, ce que j'avois dit dans ma première Préface, sur la substitution de mot Cosmologie à celui de Géologie, quoiqu'il ne s'agisse pas de l'Univers, mais seulement de la Terre: … " (I repeat here what I said in my first preface about the substitution of the word "cosmology" for that of "geology", although it is not a matter of the universe but only of the Earth: … ) [Note: A pirated edition of this book was published in 1778.]

- ^ Saussure, Horace-Bénédict de, Voyages dans les Alpes, … (Neuchatel, (Switzerland): Samuel Fauche, 1779). From pp. i–ii: Archived 2017-02-06 at the Wayback Machine "La science qui rassemble les faits, qui seuls peuvent servir de base à la Théorie de la Terre ou à la Géologie, c'est la Géographie physique, ou la description de notre Globe; … " (The science that assembles the facts which alone can serve as the basis of the theory of the Earth or of "geology", is physical geography, or the description of our globe; … )

- ^ On the controversy regarding whether Deluc or Saussure deserves priority in the use the term "geology":

- Zittel, Karl Alfred von, with Maria M. Ogilvie-Gordon, trans., History of Geology and Paleontology to the End of the Nineteenth Century (London, England: Walter Scott, 1901), p. 76.

- Geikie, Archibald, The Founders of Geology, 2nd ed. (London, England: Macmillan and Company, 1905), p. 186.. Archived 2017-02-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- Eastman, Charles Rochester (12 August 1904). Letter to the Editor: "Variæ Auctoritatis". Archived 2017-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, Science, 2nd series, 20 (502): 215–217; see p. 216.

- Emmons, Samuel Franklin (21 October 1904). Letter to the Editor: "Variæ Auctoritatis". Archived 2017-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, Science, 2nd series, 20 (512): 537.

- Eastman, C.R. (25 November 1904). Letter to the Editor: "Notes on the History of Scientific Nomenclature", Archived 2017-02-07 at the Wayback Machine. Science, 2nd series, 20 (517): 727–730; see p. 728.

- Emmons, S. F. (23 December 1904). Letter to the Editor: "The term 'geology' ", Science, 2nd series, 20 (521): 886–887.

- Eastman, C. R. (20 January 1905). Letter to the Editor: "Deluc's 'Geological Letters'". Archived 2017-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, Science, 2nd series, 21 (525): 111.

- Emmons, S. F. (17 February 1905). Letter to the Editor: "Deluc versus de Saussure". Archived 2017-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, Science, 2nd series, 21 (529): 274–275.

- ^ Winchester, Simon (2001). The Map that Changed the World. HarperCollins Publishers. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-06-093180-3.

- ^ Escholt, Michel Pedersøn, Geologia Norvegica : det er, En kort undervisning om det vitt-begrebne jordskelff som her udi Norge skeedemesten ofuer alt Syndenfields den 24. aprilis udi nærværende aar 1657: sampt physiske, historiske oc theologiske fundament oc grundelige beretning om jordskellfs aarsager oc betydninger Archived 2017-02-16 at the Wayback Machine [Norwegian geology: that is, a brief lesson about the widely-perceived earthquake which happened here in Norway across all southern parts [on] the 24th of April in the present year 1657: together with physical, historical, and theological bases and a basic account of earthquakes' causes and meanings] (Christiania (now: Oslo), Norway: Mickel Thomesøn, 1657). (in Danish).

- Reprinted in English as: Escholt, Michel Pedersøn with Daniel Collins, trans., Geologia Norvegica … . Archived 2017-02-16 at the Wayback Machine. (London, England: S. Thomson, 1663).

- ^ Kermit H., (2003) Niels Stensen, 1638–1686: the scientist who was beatified. Archived 2017-01-20 at the Wayback Machine. Gracewing Publishing. p. 127.

- ^ Lomonosov, Mikhail (2012). On the Strata of the Earth. Translation and commentary by S.M. Rowland and S. Korolev. The Geological Society of America, Special Paper 485. ISBN 978-0-8137-2485-0. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-19.

- ^ Vernadsky, V. (1911). Pamyati M.V. Lomonosova. Zaprosy zhizni, 5: 257–262 (in Russian) [In memory of M.V. Lomonosov].

- ^ James Hutton: The Founder of Modern Geology. Archived 2016-08-27 at the Wayback Machine. American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ Gutenberg ebook links: (Vol. 1. Theory of the Earth, with Proofs and Illustrations, Volume 1 (Of 4). Archived from the original on 2020-09-14. Retrieved 2022-07-30., Vol. 2. Theory of the Earth, with Proofs and Illustrations, Volume 2 (Of 4). Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2020-08-28.).

- ^ Corbin, Alain (2021). Terra Incognita: A History of Ignorance in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Translated by Pickford, Susan. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-5095-4627-5.

- ^ Maclure, William (1817). Observations on the Geology of the United States of America: With Some Remarks on the Effect Produced on the Nature and Fertility of Soils, by the Decomposition of the Different Classes of Rocks; and an Application to the Fertility of Every State in the Union, in Reference to the Accompanying Geological Map. Philadelphia: Abraham Small. Archived from the original on 2015-10-27. Retrieved 2015-11-14.

- ^ Greene, J. C.; Burke, J. G. (1978). "The Science of Minerals in the Age of Jefferson". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. New Series. 68 (4): 1–113 [39]. doi:10.2307/1006294. JSTOR 1006294.

- ^ Maclure's 1809 Geological Map. Archived 2014-08-14 at the Wayback Machine. davidrumsey.com.

- ^ Lyell, Charles (1991). Principles of geology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-49797-6.

- ^ England, Philip; Molnar, Peter; Richter, Frank (2007). "John Perry's neglected critique of Kelvin's age for the Earth: A missed opportunity in geodynamics". GSA Today. 17 (1): 4. Bibcode:2007GSAT...17R...4E. doi:10.1130/GSAT01701A.1.

External links

[edit]- One Geology: This interactive geological map of the world is an international initiative of the geological surveys around the globe. This groundbreaking project was launched in 2007 and contributed to the 'International Year of Planet Earth', becoming one of their flagship projects.

- Earth Science News, Maps, Dictionary, Articles, Jobs

- American Geophysical Union

- American Geosciences Institute

- European Geosciences Union

- European Federation of Geologists

- Geological Society of America