Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Precisionism

View on Wikipedia

Precisionism was a modernist art movement that emerged in the United States after World War I. Influenced by Cubism, Purism, and Futurism, Precisionist artists reduced subjects to their essential geometric shapes, eliminated detail, and often used planes of light to create a sense of crisp focus and suggest the sleekness and sheen of machine forms. At the height of its popularity during the 1920s and early 1930s, Precisionism celebrated the new American landscape of skyscrapers, bridges, and factories in a form that has also been called "Cubist-Realism."[1] The term "Precisionism" was first coined in the mid-1920s, possibly by Museum of Modern Art director Alfred H. Barr[2] although according to Amy Dempsey the term "Precisionism" was coined by Charles Sheeler.[3] Painters working in this style were also known as the "Immaculates", which was the more commonly used term at the time.[4] The stiffness of both art-historical labels suggests the difficulties contemporary critics had in attempting to characterize these artists.

An American movement

[edit]

While influenced by European modernist artistic movements like Cubism, Purism, and Futurism, Precisionism focused on the themes of industrialization and modernization in the American landscape, using precise, sharply defined geometrical forms. Precisionist artists embraced their American identity and some were reluctant to acknowledge European artistic influences.[5]

There is a degree of reverence for the industrial age in the movement, but social commentary was not fundamental to the style. Like Pop Art, Precisionism has on occasion been interpreted as a criticism of the de-natured society it portrays, though its artists did not often feel comfortable with this reading of their work. Elsie Driggs' Pittsburgh (1926) illustrates this gap in perception.[6] A painting of black and gray steel-mill smokestacks, thick piping, and crisscrossing wires, with only clouds of smoke to relieve the severity of the image, viewers have been tempted to see this dark painting as a statement of environmental concern. To the contrary, Driggs always claimed that she intended an ironic beauty in the image and referred to it as "my El Greco." Upon seeing the painting, Charles Daniel dubbed her "one of the new classicists."[7] More often than not, Precisionism implicitly celebrated man-made dynamism and new technologies. Possible exceptions to this statement are some of the darker, more claustrophobic city paintings of Louis Lozowick and the comic anti-capitalist satires of Preston Dickinson.

Varying degrees of abstraction are found in Precisionist works. The Figure 5 in Gold (1928) by Charles Demuth, an homage to William Carlos Williams' imagist poem about a fire truck is abstract and stylized, while the paintings of Charles Sheeler sometimes verge on a form of photorealism. (In addition to his meticulously detailed paintings like River Rouge Plant and American Landscape, Sheeler, like his friend Paul Strand, also created sharply focused photographs of factories and public buildings.[8]) Some Precisionist works tended toward a "highly controlled approach to technique and form" as well as an application of "hard-edged style to long-familiar American scenes".[9]

Precisionist artists often focused on urban imagery: office towers, apartment houses, bridges, tunnels, subway platforms, streets, the skyline and grid of the modern city. Other artists, however, such as Georgia O'Keeffe, Charles Demuth, Niles Spencer, Ralston Crawford, Sanford Ross, and Charles Sheeler, applied the same approach to more pastoral settings and painted starkly geometric renderings of barns, cottages, country roads, and farm houses. Stuart Davis and Gerald Murphy painted still life compositions in a Precisionist style.

Precisionists

[edit]

American artists whose work has been labeled as reflective of Precisionism include: Anna Held Audette,[10] George Ault, Ralston Crawford, Francis Criss, Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, Georgia O'Keeffe, Preston Dickinson, Elsie Driggs, Louis Lozowick, Gerald Murphy, Charles Sheeler, Niles Spencer, Morton Schamberg, Joseph Stella,[11] Charles Rosen, Dale Nichols, Millard Sheets,[12]Edward Hopper, Virginia Berresford, Henry Billings, Peter Blume, Stefan Hirsch, Edmund Lewandowski, John Storrs, Miklos Suba, Sandor Bernath, Herman Trunk, Arnold Wiltz, Clarence Holbrook Carter, Edgar Corbridge and the photographers Paul Strand and Lewis Hine. The movement had no major presence outside the United States, although it did influence Australian art where Jeffrey Smart adopted its principles.[citation needed] Although no manifesto was ever created, some of the artists were friends and frequently exhibited at the same galleries. Georgia O'Keeffe's husband, photographer and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz, was a highly regarded mentor for the group and was especially supportive of Paul Strand.[citation needed]

Precisionism had an indirect influence on the later styles known as magic realism, pop art, and photorealism, but it was largely considered a dated "period style" by the 1950s, though its influence on advertising imagery and stage and set design continued throughout the twentieth century. Its two most famous practitioners are Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler.[citation needed]

Gallery

[edit]-

Morton Schamberg, Telephone, 1916, oil on canvas, Columbus Museum of Art.

-

John Storrs, Profile Head with Cap, c. 1918, woodcut on paper Smithsonian American Art Museum

-

Joseph Stella, Brooklyn Bridge, 1919–1920, Yale University Art Gallery

-

Stuart Davis, Steeple and Street, 1922, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC.

-

Charles Demuth, Incense of a New Church (1921)

-

Charles Demuth, My Egypt, oil on composition board, 1927, Whitney Museum

-

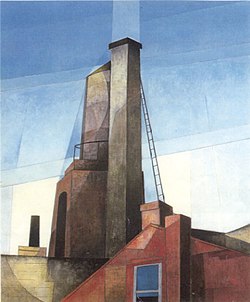

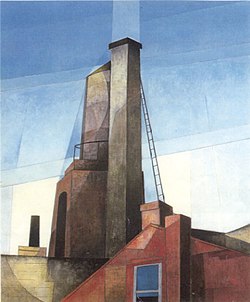

Charles Demuth, Chimney and Watertower, oil on composition board, 1931, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

-

Charles Sheeler, Skyscrapers (1922)

-

Charles Rosen, Sidewheel in the Rondout

References

[edit]- ^ Milton Brown, American Painting from the Armory Show to the Depression (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955), pp. 114–115.

- ^ Gail Stavitsky, Precisionism in America, 1915–1941: Reordering Reality (New York: Abrams, 1994), p. 21.

- ^ [Styles, schools and movements, published by Thames & Hudson 2002 Amy Dempsey]

- ^ Stavitsky, p. 19.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ For a fuller discussion of Pittsburgh, see Constance Kimmerle, Elsie Driggs: The Quick and the Classical (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), pp. 31-33 and John Loughery, "Blending the Classical and the Modern: The Art of Elsie Driggs", Woman's Art Journal (Winter 1987), p 24.

- ^ Kimmerle, p. 32.

- ^ Charles Sheeler photo, retrieved online November 9, 2008

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ "The Art of Anna Held Audette – APM". American Precision Museum. Retrieved 25 December 2024.

- ^ The New York Times, Roberta Smith, ART VIEW: Precisionism And a Few Of Its Friends", October 26, 2008

- ^ The Hilbert Museum reveals treasures of California Scene Painting, Liz Goldner, February 24, 2016 KCET https://www.kcet.org/

Bibliography

[edit]- Acker, Emma; Canterbury, Sue; Daub, Adrian; and Palmor, Lauren. Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American Art. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018.

- Barry, Claire and Fahlman, Betsy. Chimneys and Towers: Charles Demuth's Late Paintings of Lancaster. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

- Friedman, Martin L. The Precisionist View in American Art. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1960.

- Harnsberger, R.S. Ten Precisionist Artists: Annotated Bibliographies. Art Reference Collection no. 14. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1992.

- Hemingway, Andrew The Mysticism of Money: Precisionist Painting and Machine Age America. Pittsburgh & New York: Periscope Publishing, 2013

- Hughes, Robert. American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America. New York; Knopf, 1994.

- Kimmerle, Constance. Elsie Driggs: The Quick and the Classical. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- Lazevnick, Ashley. Fantasies of Precision: American Modern Art, 1908-1947. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2023.

- Martin, Michael (ed.). Edmund Lewandowski: Precisionism and Beyond. Flint, MI: Flint Institute of Arts, 2010.

- Rawlinson, Mark. Charles Sheeler: Modernism, Precisionism and the Borders of Abstraction. Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, England, UK: Routledge, 2025.

- Stavitsky, Gail. Precisionism in America, 1915–1941: Reordering Reality. New York: Abrams, 1994.

- Tsujimoto, Karen. Images of America: Precisionist Painting and Modern Photography. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1982.

- Ward, Meredith. Streamlined: The Precisionist Impulse in American Art. New York: Hirschl & Adler Galleries, 1995.

Further reading

[edit]- Kramer, Hilton, 1982, "Precisionism Revised" in Revenge of the Philistines, Art & Culture 1972–1984. Free Press, September 12, 2007, ISBN 1416576932

External links

[edit]- "Precisionism" in Artcyclopedia

- Precisionism at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Precisionists—Consummate Anti-Expressionists