Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The accessibility of this article is in question. The specific issue is: animation fails MOS, see talk. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. (April 2025) |

A pump is a device that moves fluids (liquids or gases), or sometimes slurries,[1] by mechanical action, typically converted from electrical energy into hydraulic or pneumatic energy.

Mechanical pumps serve in a wide range of applications such as pumping water from wells, aquarium filtering, pond filtering and aeration, in the car industry for water-cooling and fuel injection, in the energy industry for pumping oil and natural gas or for operating cooling towers and other components of heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems. In the medical industry, pumps are used for biochemical processes in developing and manufacturing medicine, and as artificial replacements for body parts, in particular the artificial heart and penile prosthesis.

When a pump contains two or more pump mechanisms with fluid being directed to flow through them in series, it is called a multi-stage pump. Terms such as two-stage or double-stage may be used to specifically describe the number of stages. A pump that does not fit this description is simply a single-stage pump in contrast.

In biology, many different types of chemical and biomechanical pumps have evolved; biomimicry is sometimes used in developing new types of mechanical pumps.

Types

[edit]Mechanical pumps may be submerged in the fluid they are pumping or be placed external to the fluid.

Pumps can be classified by their method of displacement into electromagnetic pumps, positive-displacement pumps, impulse pumps, velocity pumps, gravity pumps, steam pumps and valveless pumps. There are three basic types of pumps: positive-displacement, centrifugal and axial-flow pumps. In centrifugal pumps the direction of flow of the fluid changes by ninety degrees as it flows over an impeller, while in axial flow pumps the direction of flow is unchanged.[2][3]

Electromagnetic pump

[edit]An electromagnetic pump is a pump that moves liquid metal, molten salt, brine, or other electrically conductive liquid using electromagnetism.

A magnetic field is set at right angles to the direction the liquid moves in, and a current is passed through it. This causes an electromagnetic force that moves the liquid.

Applications include pumping molten solder in many wave soldering machines, pumping liquid-metal coolant, and magnetohydrodynamic drive.

Positive-displacement pumps

[edit]

A positive-displacement pump makes a fluid move by trapping a fixed amount and forcing (displacing) that trapped volume into the discharge pipe.

Some positive-displacement pumps use an expanding cavity on the suction side and a decreasing cavity on the discharge side. Liquid flows into the pump as the cavity on the suction side expands and the liquid flows out of the discharge as the cavity collapses. The volume is constant through each cycle of operation.

Positive-displacement pump behavior and safety

[edit]Positive-displacement pumps, unlike centrifugal, can theoretically produce the same flow at a given rotational speed no matter what the discharge pressure. Thus, positive-displacement pumps are constant flow machines. However, a slight increase in internal leakage as the pressure increases prevents a truly constant flow rate.

A positive-displacement pump must not operate against a closed valve on the discharge side of the pump, because it has no shutoff head like centrifugal pumps. A positive-displacement pump operating against a closed discharge valve continues to produce flow and the pressure in the discharge line increases until the line bursts, the pump is severely damaged, or both.

A relief or safety valve on the discharge side of the positive-displacement pump is therefore necessary. The relief valve can be internal or external. The pump manufacturer normally has the option to supply internal relief or safety valves. The internal valve is usually used only as a safety precaution. An external relief valve in the discharge line, with a return line back to the suction line or supply tank, provides increased safety.

Positive-displacement types

[edit]A positive-displacement pump can be further classified according to the mechanism used to move the fluid:

- Rotary-type positive displacement: internal and external gear pump, screw pump, lobe pump, shuttle block, flexible vane and sliding vane, circumferential piston, flexible impeller, helical twisted roots (e.g. the Wendelkolben pump) and liquid-ring pumps

- Reciprocating-type positive displacement: piston pumps, plunger pumps and diaphragm pumps

- Linear-type positive displacement: rope pumps and chain pumps

Rotary positive-displacement pumps

[edit]

These pumps move fluid using a rotating mechanism that creates a vacuum that captures and draws in the liquid.[4]

Advantages: Rotary pumps are very efficient[5] because they can handle highly viscous fluids with higher flow rates as viscosity increases.[6]

Drawbacks: The nature of the pump requires very close clearances between the rotating pump and the outer edge, making it rotate at a slow, steady speed. If rotary pumps are operated at high speeds, the fluids cause erosion, which eventually causes enlarged clearances that liquid can pass through, which reduces efficiency.

Rotary positive-displacement pumps fall into five main types:

- Gear pumps – a simple type of rotary pump where the liquid is pushed around a pair of gears.

- Screw pumps – the shape of the internals of this pump is usually two screws turning against each other to pump the liquid

- Rotary vane pumps

- Hollow disc pumps (also known as eccentric disc pumps or hollow rotary disc pumps), similar to scroll compressors, these have an eccentric cylindrical rotor encased in a circular housing. As the rotor orbits, it traps fluid between the rotor and the casing, drawing the fluid through the pump. It is used for highly viscous fluids like petroleum-derived products, and it can also support high pressures of up to 290 psi.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13]

- Peristaltic pumps have rollers which pinch a section of flexible tubing, forcing the liquid ahead as the rollers advance. Because they are very easy to keep clean, these are popular for dispensing food, medicine, and concrete.

Reciprocating positive-displacement pumps

[edit]

Reciprocating pumps move the fluid using one or more oscillating pistons, plungers, or membranes (diaphragms), while valves restrict fluid motion to the desired direction. In order for suction to take place, the pump must first pull the plunger in an outward motion to decrease pressure in the chamber. Once the plunger pushes back, it will increase the chamber pressure and the inward pressure of the plunger will then open the discharge valve and release the fluid into the delivery pipe at constant flow rate and increased pressure.

Pumps in this category range from simplex, with one cylinder, to in some cases quad (four) cylinders, or more. Many reciprocating-type pumps are duplex (two) or triplex (three) cylinder. They can be either single-acting with suction during one direction of piston motion and discharge on the other, or double-acting with suction and discharge in both directions. The pumps can be powered manually, by air or steam, or by a belt driven by an engine. This type of pump was used extensively in the 19th century—in the early days of steam propulsion—as boiler feed water pumps. Now reciprocating pumps typically pump highly viscous fluids like concrete and heavy oils, and serve in special applications that demand low flow rates against high resistance. Reciprocating hand pumps were widely used to pump water from wells. Common bicycle pumps and foot pumps for inflation use reciprocating action.

These positive-displacement pumps have an expanding cavity on the suction side and a decreasing cavity on the discharge side. Liquid flows into the pumps as the cavity on the suction side expands and the liquid flows out of the discharge as the cavity collapses. The volume is constant given each cycle of operation and the pump's volumetric efficiency can be achieved through routine maintenance and inspection of its valves.[14]

Typical reciprocating pumps are:

- Plunger pump – a reciprocating plunger pushes the fluid through one or two open valves, closed by suction on the way back.

- Diaphragm pump – similar to plunger pumps, where the plunger pressurizes hydraulic oil which is used to flex a diaphragm in the pumping cylinder. Diaphragm valves are used to pump hazardous and toxic fluids.

- Piston pump displacement pumps – usually simple devices for pumping small amounts of liquid or gel manually. The common hand soap dispenser is such a pump.

- Radial piston pump – a form of hydraulic pump where pistons extend in a radial direction.

- Vibratory pump or vibration pump – a particularly low-cost form of plunger pump, popular in low-cost espresso machines.[15][16] The only moving part is a spring-loaded piston, the armature of a solenoid. Driven by half-wave rectified alternating current, the piston is forced forward while energized, and is retracted by the spring during the other half cycle. Due to their inefficiency, vibratory pumps typically cannot be operated for more than one minute without overheating, so are limited to intermittent duty.

Various positive-displacement pumps

[edit]The positive-displacement principle applies in these pumps:

- Rotary lobe pump

- Progressing cavity pump

- Rotary gear pump

- Piston pump

- Diaphragm pump

- Screw pump

- Gear pump

- Hydraulic pump

- Rotary vane pump

- Peristaltic pump

- Rope pump

- Flexible impeller pump

Gear pump

[edit]

This is the simplest form of rotary positive-displacement pumps. It consists of two meshed gears that rotate in a closely fitted casing. The tooth spaces trap fluid and force it around the outer periphery. The fluid does not travel back on the meshed part, because the teeth mesh closely in the center. Gear pumps see wide use in car engine oil pumps and in various hydraulic power packs.

Screw pump

[edit]

A screw pump is a more complicated type of rotary pump that uses two or three screws with opposing thread — e.g., one screw turns clockwise and the other counterclockwise. The screws are mounted on parallel shafts that often have gears that mesh so the shafts turn together and everything stays in place. In some cases the driven screw drives the secondary screw, without gears, often using the fluid to limit abrasion. The screws turn on the shafts and drive fluid through the pump. As with other forms of rotary pumps, the clearance between moving parts and the pump's casing is minimal.

Progressing cavity pump

[edit]

Widely used for pumping difficult materials, such as sewage sludge contaminated with large particles, a progressing cavity pump consists of a helical rotor, about ten times as long as its width, and a stator, mainly made out of rubber. This can be visualized as a central core of diameter x with, typically, a curved spiral wound around of thickness half x, though in reality it is manufactured in a single lobe. This shaft fits inside a heavy-duty rubber sleeve or stator, of wall thickness also typically x. As the shaft rotates inside the stator, the rotor gradually forces fluid up the rubber cavity. Such pumps can develop very high pressure at low volumes at a rate of 90 PSI per stage on water for standard configurations.

Roots-type pump

[edit]

Named after the Roots brothers who invented it, this lobe pump displaces the fluid trapped between two long helical rotors, each fitted into the other when perpendicular at 90°, rotating inside a triangular shaped sealing line configuration, both at the point of suction and at the point of discharge. This design produces a continuous flow with equal volume and no vortex. It can work at low pulsation rates, and offers gentle performance that some applications require.

Applications include:

- High capacity industrial air compressors.

- Roots superchargers on internal combustion engines.

- A brand of civil defense siren, the Federal Signal Corporation's Thunderbolt.

Peristaltic pump

[edit]

A peristaltic pump is a type of positive-displacement pump. It contains fluid within a flexible tube fitted inside a circular pump casing (though linear peristaltic pumps have been made). A number of rollers, shoes, or wipers attached to a rotor compress the flexible tube. As the rotor turns, the part of the tube under compression closes (or occludes), forcing the fluid through the tube. Additionally, when the tube opens to its natural state after the passing of the cam it draws (restitution) fluid into the pump. This process is called peristalsis and is used in many biological systems such as the gastrointestinal tract.

Plunger pumps

[edit]Plunger pumps are reciprocating positive-displacement pumps.

These consist of a cylinder with a reciprocating plunger. The suction and discharge valves are mounted in the head of the cylinder. In the suction stroke, the plunger retracts and the suction valves open causing suction of fluid into the cylinder. In the forward stroke, the plunger pushes the liquid out of the discharge valve.

Efficiency and common problems: With only one cylinder in plunger pumps, the fluid flow varies between maximum flow when the plunger moves through the middle positions, and zero flow when the plunger is at the end positions. A lot of energy is wasted when the fluid is accelerated in the piping system. Vibration and water hammer may be a serious problem. In general, the problems are compensated for by using two or more cylinders not working in phase with each other. Centrifugal pumps are also susceptible to water hammer.[17], a specialized study, helps evaluate this risk in such systems.

Triplex-style plunger pump

[edit]Triplex plunger pumps use three plungers, which reduces the pulsation relative to single reciprocating plunger pumps. Adding a pulsation dampener on the pump outlet can further smooth the pump ripple, or ripple graph of a pump transducer. The dynamic relationship of the high-pressure fluid and plunger generally requires high-quality plunger seals. Plunger pumps with a larger number of plungers have the benefit of increased flow, or smoother flow without a pulsation damper. The increase in moving parts and crankshaft load is one drawback.

Car washes often use these triplex-style plunger pumps (perhaps without pulsation dampers). In 1968, William Bruggeman reduced the size of the triplex pump and increased the lifespan so that car washes could use equipment with smaller footprints. Durable high-pressure seals, low-pressure seals and oil seals, hardened crankshafts, hardened connecting rods, thick ceramic plungers and heavier duty ball and roller bearings improve reliability in triplex pumps. Triplex pumps now are in a myriad of markets across the world.

Triplex pumps with shorter lifetimes are commonplace to the home user. A person who uses a home pressure washer for 10 hours a year may be satisfied with a pump that lasts 100 hours between rebuilds. Industrial-grade or continuous duty triplex pumps on the other end of the quality spectrum may run for as much as 2,080 hours a year.[18]

The oil and gas drilling industry uses massive semi-trailer-transported triplex pumps called mud pumps to pump drilling mud, which cools the drill bit and carries the cuttings back to the surface.[19] Drillers use triplex or even quintuplex pumps to inject water and solvents deep into shale in the extraction process called fracking.

Diaphragm pump

[edit]Typically run on electricity compressed air, diaphragm pumps are relatively inexpensive and can perform a wide variety of duties, from pumping air into an aquarium, to liquids through a filter press. Double-diaphragm pumps can handle viscous fluids and abrasive materials with a gentle pumping process ideal for transporting shear-sensitive media.[20]

Rope pump

[edit]

Impulse pump

[edit]Impulse pumps use pressure created by gas (usually air). In some impulse pumps the gas trapped in the liquid (usually water), is released and accumulated somewhere in the pump, creating a pressure that can push part of the liquid upwards.

Conventional impulse pumps include:

- Hydraulic ram pumps – kinetic energy of a low-head water supply is stored temporarily in an air-bubble hydraulic accumulator, then used to drive water to a higher head.

- Pulser pumps – run with natural resources, by kinetic energy only.

- Airlift pumps – run on air inserted into pipe, which pushes the water up when bubbles move upward

Instead of a gas accumulation and releasing cycle, the pressure can be created by burning of hydrocarbons. Such combustion driven pumps directly transmit the impulse from a combustion event through the actuation membrane to the pump fluid. In order to allow this direct transmission, the pump needs to be almost entirely made of an elastomer (e.g. silicone rubber). Hence, the combustion causes the membrane to expand and thereby pumps the fluid out of the adjacent pumping chamber. The first combustion-driven soft pump was developed by ETH Zurich.[21]

Hydraulic ram pump

[edit]A hydraulic ram is a water pump powered by hydropower.[22]

It takes in water at relatively low pressure and high flow-rate and outputs water at a higher hydraulic-head and lower flow-rate. The device uses the water hammer effect to develop pressure that lifts a portion of the input water that powers the pump to a point higher than where the water started.

The hydraulic ram is sometimes used in remote areas, where there is both a source of low-head hydropower, and a need for pumping water to a destination higher in elevation than the source. In this situation, the ram is often useful, since it requires no outside source of power other than the kinetic energy of flowing water.

Velocity pumps

[edit]

Rotodynamic pumps (or dynamic pumps) are a type of velocity pump in which kinetic energy is added to the fluid by increasing the flow velocity. This increase in energy is converted to a gain in potential energy (pressure) when the velocity is reduced prior to or as the flow exits the pump into the discharge pipe. This conversion of kinetic energy to pressure is explained by the First law of thermodynamics, or more specifically by Bernoulli's principle.

Dynamic pumps can be further subdivided according to the means in which the velocity gain is achieved.[23]

These types of pumps have a number of characteristics:

- Continuous energy

- Conversion of added energy to increase in kinetic energy (increase in velocity)

- Conversion of increased velocity (kinetic energy) to an increase in pressure head

A practical difference between dynamic and positive-displacement pumps is how they operate under closed valve conditions. Positive-displacement pumps physically displace fluid, so closing a valve downstream of a positive-displacement pump produces a continual pressure build up that can cause mechanical failure of pipeline or pump. Dynamic pumps differ in that they can be safely operated under closed valve conditions (for short periods of time).

Radial-flow pump

[edit]Such a pump is also referred to as a centrifugal pump. The fluid enters along the axis or center, is accelerated by the impeller and exits at right angles to the shaft (radially); an example is the centrifugal fan, which is commonly used to implement a vacuum cleaner. Another type of radial-flow pump is a vortex pump. The liquid in them moves in tangential direction around the working wheel. The conversion from the mechanical energy of motor into the potential energy of flow comes by means of multiple whirls, which are excited by the impeller in the working channel of the pump. Generally, a radial-flow pump operates at higher pressures and lower flow rates than an axial- or a mixed-flow pump.

Axial-flow pump

[edit]These are also referred to as all-fluid pumps. The fluid is pushed outward or inward to move fluid axially. They operate at much lower pressures and higher flow rates than radial-flow (centrifugal) pumps. Axial-flow pumps cannot be run up to speed without special precaution. If at a low flow rate, the total head rise and high torque associated with this pipe would mean that the starting torque would have to become a function of acceleration for the whole mass of liquid in the pipe system.[24]

Mixed-flow pumps function as a compromise between radial and axial-flow pumps. The fluid experiences both radial acceleration and lift and exits the impeller somewhere between 0 and 90 degrees from the axial direction. As a consequence mixed-flow pumps operate at higher pressures than axial-flow pumps while delivering higher discharges than radial-flow pumps. The exit angle of the flow dictates the pressure head-discharge characteristic in relation to radial and mixed-flow.

Regenerative turbine pump

[edit]

Also known as drag, friction, liquid-ring pump, peripheral, traction, turbulence, or vortex pumps, regenerative turbine pumps are a class of rotodynamic pump that operates at high head pressures, typically 4–20 bars (400–2,000 kPa; 58–290 psi).[25]

The pump has an impeller with a number of vanes or paddles which spins in a cavity. The suction port and pressure ports are located at the perimeter of the cavity and are isolated by a barrier called a stripper, which allows only the tip channel (fluid between the blades) to recirculate, and forces any fluid in the side channel (fluid in the cavity outside of the blades) through the pressure port. In a regenerative turbine pump, as fluid spirals repeatedly from a vane into the side channel and back to the next vane, kinetic energy is imparted to the periphery,[25] thus pressure builds with each spiral, in a manner similar to a regenerative blower.[26][27][28]

As regenerative turbine pumps cannot become vapor locked, they are commonly applied to volatile, hot, or cryogenic fluid transport. However, as tolerances are typically tight, they are vulnerable to solids or particles causing jamming or rapid wear. Efficiency is typically low, and pressure and power consumption typically decrease with flow. Additionally, pumping direction can be reversed by reversing direction of spin.[28][26][29]

Side-channel pump

[edit]A side-channel pump has a suction disk, an impeller, and a discharge disk.[30]

Eductor-jet pump

[edit]This uses a jet, often of steam, to create a low pressure. This low pressure sucks in fluid and propels it into a higher-pressure region.

Gravity pumps

[edit]Gravity pumps include the syphon and Heron's fountain. The hydraulic ram is also sometimes called a gravity pump. In a gravity pump the fluid is lifted by gravitational force.

Steam pump

[edit]Steam pumps have been for a long time mainly of historical interest. They include any type of pump powered by a steam engine and also pistonless pumps such as Thomas Savery's or the Pulsometer steam pump.

Recently there has been a resurgence of interest in low-power solar steam pumps for use in smallholder irrigation in developing countries. Previously small steam engines have not been viable because of escalating inefficiencies as vapour engines decrease in size. However the use of modern engineering materials coupled with alternative engine configurations has meant that these types of system are now a cost-effective opportunity.

Valveless pumps

[edit]Valveless pumping assists in fluid transport in various biomedical and engineering systems. In a valveless pumping system, no valves (or physical occlusions) are present to regulate the flow direction. The fluid pumping efficiency of a valveless system, however, is not necessarily lower than that having valves. In fact, many fluid-dynamical systems in nature and engineering more or less rely upon valveless pumping to transport the working fluids therein. For instance, blood circulation in the cardiovascular system is maintained to some extent even when the heart's valves fail. Meanwhile, the embryonic vertebrate heart begins pumping blood long before the development of discernible chambers and valves. Similar to blood circulation in one direction, bird respiratory systems pump air in one direction in rigid lungs, but without any physiological valve. In microfluidics, valveless impedance pumps have been fabricated, and are expected to be particularly suitable for handling sensitive biofluids. Ink jet printers operating on the piezoelectric transducer principle also use valveless pumping. The pump chamber is emptied through the printing jet due to reduced flow impedance in that direction and refilled by capillary action.

Pump repairs

[edit]

Examining pump repair records and mean time between failures (MTBF) is of great importance to responsible and conscientious pump users. In view of that fact, the preface to the 2006 Pump User's Handbook alludes to "pump failure" statistics. For the sake of convenience, these failure statistics often are translated into MTBF (in this case, installed life before failure).[31]

In early 2005, Gordon Buck, John Crane Inc.'s chief engineer for field operations in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, examined the repair records for a number of refinery and chemical plants to obtain meaningful reliability data for centrifugal pumps. A total of 15 operating plants having nearly 15,000 pumps were included in the survey. The smallest of these plants had about 100 pumps; several plants had over 2000. All facilities were located in the United States. In addition, considered as "new", others as "renewed" and still others as "established". Many of these plants—but not all—had an alliance arrangement with John Crane. In some cases, the alliance contract included having a John Crane Inc. technician or engineer on-site to coordinate various aspects of the program.

Not all plants are refineries, however, and different results occur elsewhere. In chemical plants, pumps have historically been "throw-away" items as chemical attack limits life. Things have improved in recent years, but the somewhat restricted space available in "old" DIN and ASME-standardized stuffing boxes places limits on the type of seal that fits. Unless the pump user upgrades the seal chamber, the pump only accommodates more compact and simple versions. Without this upgrading, lifetimes in chemical installations are generally around 50 to 60 percent of the refinery values.

Unscheduled maintenance is often one of the most significant costs of ownership, and failures of mechanical seals and bearings are among the major causes. Keep in mind the potential value of selecting pumps that cost more initially, but last much longer between repairs. The MTBF of a better pump may be one to four years longer than that of its non-upgraded counterpart. Consider that published average values of avoided pump failures range from US$2600 to US$12,000. This does not include lost opportunity costs. One pump fire occurs per 1000 failures. Having fewer pump failures means having fewer destructive pump fires.

As has been noted, a typical pump failure, based on actual year 2002 reports, costs US$5,000 on average. This includes costs for material, parts, labor and overhead. Extending a pump's MTBF from 12 to 18 months would save US$1,667 per year — which might be greater than the cost to upgrade the centrifugal pump's reliability.[31][1][32]

Applications

[edit]

Pumps are used throughout society for a variety of purposes. Early applications includes the use of the windmill or watermill to pump water. Today, the pump is used for irrigation, water supply, gasoline supply, air conditioning systems, refrigeration (usually called a compressor), chemical movement, sewage movement, flood control, marine services, etc.

Because of the wide variety of applications, pumps have a plethora of shapes and sizes: from very large to very small, from handling gas to handling liquid, from high pressure to low pressure, and from high volume to low volume.

Priming a pump

[edit]Typically, a liquid pump cannot simply draw air. The feed line of the pump and the internal body surrounding the pumping mechanism must first be filled with the liquid that requires pumping: An operator must introduce liquid into the system to initiate the pumping, known as priming the pump. Loss of prime is usually due to ingestion of air into the pump, or evaporation of the working fluid if the pump is used infrequently. Clearances and displacement ratios in pumps for liquids are insufficient for pumping compressible gas, so air or other gasses in the pump can not be evacuated by the pump's action alone. This is the case with most velocity (rotodynamic) pumps — for example, centrifugal pumps. For such pumps, the position of the pump and intake tubing should be lower than the suction point so it is primed by gravity; otherwise the pump should be manually filled with liquid or a secondary pump should be used until all air is removed from the suction line and the pump casing. Liquid ring pumps have a dedicated intake for the priming liquid separate from the intake of the fluid being pumped, as the fluid being pumped may be a gas or mix of gas, liquid, and solids. For these pumps the priming liquid intake must be supplied continuously (either by gravity or pressure), however the intake for the fluid being pumped is capable of drawing a vacuum equivalent to the boiling point of the priming liquid.[33]

Positive–displacement pumps, however, tend to have sufficiently tight sealing between the moving parts and the casing or housing of the pump that they can be described as self-priming. Such pumps can also serve as priming pumps, so-called when they are used to fulfill that need for other pumps in lieu of action taken by a human operator.

Pumps as public water supplies

[edit]

One sort of pump once common worldwide was a hand-powered water pump, or 'pitcher pump'. It was commonly installed over community water wells in the days before piped water supplies.

In parts of the British Isles, it was often called the parish pump. Though such community pumps are no longer common, people still used the expression parish pump to describe a place or forum where matters of local interest are discussed.[37]

Because water from pitcher pumps is drawn directly from the soil, it is more prone to contamination. If such water is not filtered and purified, consumption of it might lead to gastrointestinal or other water-borne diseases. A notorious case is the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak. At the time it was not known how cholera was transmitted, but physician John Snow suspected contaminated water and had the handle of the public pump he suspected removed; the outbreak then subsided.

Modern hand-operated community pumps are considered the most sustainable low-cost option for safe water supply in resource-poor settings, often in rural areas in developing countries. A hand pump opens access to deeper groundwater that is often not polluted and also improves the safety of a well by protecting the water source from contaminated buckets. Pumps such as the Afridev pump are designed to be cheap to build and install, and easy to maintain with simple parts. However, scarcity of spare parts for these types of pumps in some regions of Africa has diminished their utility for these areas.

Sealing multiphase pumping applications

[edit]Multiphase pumping applications, also referred to as tri-phase, have grown due to increased oil drilling activity. In addition, the economics of multiphase production is attractive to upstream operations as it leads to simpler, smaller in-field installations, reduced equipment costs and improved production rates. In essence, the multiphase pump can accommodate all fluid stream properties with one piece of equipment, which has a smaller footprint. Often, two smaller multiphase pumps are installed in series rather than having just one massive pump.

Types and features of multiphase pumps

[edit]Helico-axial (centrifugal)

[edit]A rotodynamic pump with one single shaft that requires two mechanical seals, this pump uses an open-type axial impeller. It is often called a Poseidon pump, and can be described as a cross between an axial compressor and a centrifugal pump.

Twin-screw (positive-displacement)

[edit]The twin-screw pump is constructed of two inter-meshing screws that move the pumped fluid. Twin screw pumps are often used when pumping conditions contain high gas volume fractions and fluctuating inlet conditions. Four mechanical seals are required to seal the two shafts.

Progressive cavity (positive-displacement)

[edit]Progressive Cavity Pumps are well suited to pump sludge, slurries, viscous, and shear sensitive fluids.[38] Progressive cavity pumps are single-screw types use in surface and downhole oil production.[39] They serve a vast arrange of industries and applications ranging from Wastewater Treatment,[40] Pulp and Paper, oil and gas, mining, and oil and gas.

Electric submersible (centrifugal)

[edit]These pumps are basically multistage centrifugal pumps and are widely used in oil well applications as a method for artificial lift. These pumps are usually specified when the pumped fluid is mainly liquid.

Buffer tank A buffer tank is often installed upstream of the pump suction nozzle in case of a slug flow. The buffer tank breaks the energy of the liquid slug, smooths any fluctuations in the incoming flow and acts as a sand trap.

As the name indicates, multiphase pumps and their mechanical seals can encounter a large variation in service conditions such as changing process fluid composition, temperature variations, high and low operating pressures and exposure to abrasive/erosive media. The challenge is selecting the appropriate mechanical seal arrangement and support system to ensure maximized seal life and its overall effectiveness.[41][42][43]

Specifications

[edit]Pumps are commonly rated by horsepower, volumetric flow rate, outlet pressure in metres (or feet) of head, inlet suction in suction feet (or metres) of head. The head can be simplified as the number of feet or metres the pump can raise or lower a column of water at atmospheric pressure.

From an initial design point of view, engineers often use a quantity termed the specific speed to identify the most suitable pump type for a particular combination of flow rate and head. Net Positive Suction Head (NPSH)[44] is crucial for pump performance. It has two key aspects:

- NPSHr (Required): The Head required for the pump to operate without cavitation issues.

- NPSHa (Available): The actual pressure provided by the system (e.g., from an overhead tank).

For optimal pump operation, NPSHa must always exceed NPSHr. This ensures the pump has enough pressure to prevent cavitation, a damaging condition.

Pumping power

[edit]The power imparted into a fluid increases the energy of the fluid per unit volume. Thus the power relationship is between the conversion of the mechanical energy of the pump mechanism and the fluid elements within the pump. In general, this is governed by a series of simultaneous differential equations, known as the Navier–Stokes equations. However a more simple equation relating only the different energies in the fluid, known as Bernoulli's equation can be used. Hence the power, P, required by the pump:

where Δp is the change in total pressure between the inlet and outlet (in Pa), and Q, the volume flow-rate of the fluid is given in m3/s. The total pressure may have gravitational, static pressure and kinetic energy components; i.e. energy is distributed between change in the fluid's gravitational potential energy (going up or down hill), change in velocity, or change in static pressure. η is the pump efficiency, and may be given by the manufacturer's information, such as in the form of a pump curve, and is typically derived from either fluid dynamics simulation (i.e. solutions to the Navier–Stokes for the particular pump geometry), or by testing. The efficiency of the pump depends upon the pump's configuration and operating conditions (such as rotational speed, fluid density and viscosity etc.)

For a typical "pumping" configuration, the work is imparted on the fluid, and is thus positive. For the fluid imparting the work on the pump (i.e. a turbine), the work is negative. Power required to drive the pump is determined by dividing the output power by the pump efficiency. Furthermore, this definition encompasses pumps with no moving parts, such as a siphon.

Efficiency

[edit]Pump efficiency is defined as the ratio of the power imparted on the fluid by the pump in relation to the power supplied to drive the pump. Its value is not fixed for a given pump, efficiency is a function of the discharge and therefore also operating head. For centrifugal pumps, the efficiency tends to increase with flow rate up to a point midway through the operating range (peak efficiency or Best Efficiency Point (BEP) ) and then declines as flow rates rise further. Pump performance data such as this is usually supplied by the manufacturer before pump selection. Pump efficiencies tend to decline over time due to wear (e.g. increasing clearances as impellers reduce in size).

When a system includes a centrifugal pump, an important design issue is matching the head loss-flow characteristic with the pump so that it operates at or close to the point of its maximum efficiency.

Pump efficiency is an important aspect and pumps should be regularly tested. Thermodynamic pump testing is one method.

Minimum flow protection

[edit]

Most large pumps have a minimum flow requirement below which the pump may be damaged by overheating, impeller wear, vibration, seal failure, drive shaft damage or poor performance.[45] A minimum flow protection system ensures that the pump is not operated below the minimum flow rate. The system protects the pump even if it is shut-in or dead-headed, that is, if the discharge line is completely closed.[46] The simplest minimum flow system is a pipe running from the pump discharge line back to the suction line. This line is fitted with an orifice plate sized to allow the pump minimum flow to pass.[47] The arrangement ensures that the minimum flow is maintained, although it is wasteful as it recycles fluid even when the flow through the pump exceeds the minimum flow. A more sophisticated, but more costly, system (see diagram) comprises a flow measuring device (FE) in the pump discharge which provides a signal into a flow controller (FIC) which actuates a flow control valve (FCV) in the recycle line. If the measured flow exceeds the minimum flow then the FCV is closed. If the measured flow falls below the minimum flow the FCV opens to maintain the minimum flowrate.[48][45] As the fluids are recycled the kinetic energy of the pump increases the temperature of the fluid. For many pumps this added heat energy is dissipated through the pipework. However, for large industrial pumps, such as oil pipeline pumps, a recycle cooler is provided in the recycle line to cool the fluids to the normal suction temperature.[49] Alternatively the recycled fluids may be returned to upstream of the export cooler in an oil refinery, oil terminal, or offshore installation.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Submersible slurry pumps in high demand". Engineering News. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ "Water lifting devices". www.fao.org. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ Engineering Sciences Data Unit (2007). "Radial, mixed and axial flow pumps. Introduction" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ "Understanding positive displacement pumps | PumpScout". Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "The Volumetric Efficiency of Rotary Positive Displacement Pumps". www.pumpsandsystems.com. 21 May 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ "Positive Displacement Pumps - LobePro Rotary Pumps". www.lobepro.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Eccentric Disc Pumps". PSG.

- ^ "Hollow Disc Rotary Pumps". APEX Equipment. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "M Pompe | Hollow Oscillating Disk Pumps | self priming pumps | reversible pumps | low-speed pumps". www.mpompe.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Hollow disc pumps". Pump Supplier Bedu. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ "3P PRINZ - Hollow rotary disk pumps - Pompe 3P - Made in Italy". www.3pprinz.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Hollow Disc Pump". magnatexpumps.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Hollow Rotary Disc Pumps". 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Triangle Pump Components – Volumetric Efficiency". 15 November 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "FAQs and Favorites – Espresso Machines". www.home-barista.com. 21 November 2014.

- ^ "The Pump: The Heart of Your Espresso Machine". Clive Coffee.

- ^ "Surge Analysis:Tool for Safe and Reliable Operation". theengineeringguide.com. 2 February 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ "Definitive Guide: Pumps Used in Pressure Washers". The Pressure Washr Review. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "How Does a Mud Pump Work? Understanding Its Working Principle". SMKST Petro. 11 November 2024. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ "Advantages of an Air Operated Double Diaphragm Pump". Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ C.M. Schumacher, M. Loepfe, R. Fuhrer, R.N. Grass, and W.J. Stark, "3D printed lost-wax casted soft silicone monoblocks enable heart-inspired pumping by internal combustion," RSC Advances, Vol. 4, pp. 16039–16042, 2014.

- ^ Demirbas, Ayhan (14 November 2008). Biofuels: Securing the Planet's Future Energy Needs. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781848820111.

- ^ "Welcome to the Hydraulic Institute". www.pumps.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ "Radial, mixed and axial flow pumps" (PDF). Institution of Diploma Marine Engineers, Bangladesh. June 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ a b Quail F, Scanlon T, Stickland M (11 January 2011). "Design optimisation of a regenerative pump using numerical and experimental techniques" (PDF). International Journal of Numerical Methods for Heat & Fluid Flow. 21: 95–111. doi:10.1108/09615531111095094. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Regenerative Turbine Pump". rothpump.com. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Rajmane, M. Satish; Kallurkar, S.P. (May 2015). "CFD Analysis of Domestic Centrifugal Pump for Performance Enhancement". International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology. 02 / #02. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Regenerative turbine pumps: product brochure" (PDF). PSG Dover: Ebsra. pp. 3-4-7. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "Dynaflow Engineering, Inc. - Regenerative Turbine Pumps". dynafloweng.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ "What is a Side Channel Pump?". Michael Smith Engineers. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Pump Statistics Should Shape Strategies - Maintenance Technology". Maintenance Technology. 1 October 2008. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ Wasser, Goodenberger, Jim and Bob (November 1993). "Extended Life, Zero Emissions Seal for Process Pumps". John Crane Technical Report. Routledge. TRP 28017.

- ^ Nash (20 January 2017). NASH Liquid Ring Vacuum Pump - How It Works. Retrieved 7 November 2024 – via YouTube.

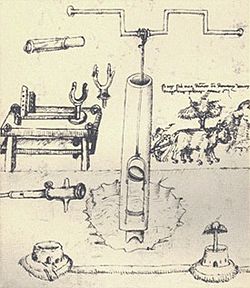

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill, "Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East", Scientific American, May 1991, pp. 64–9 (cf. Donald Hill, Mechanical Engineering Archived 25 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Ahmad Y. al-Hassan. "The Origin of the Suction Pump: al-Jazari 1206 A.D." Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ Hill, Donald Routledge (1996). A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times. London: Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 0-415-15291-7.

- ^ "Online Dictionary – Parish Pump". Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ^ Daniel, Alvarado. "Production Engineer". sulzer. Retrieved 6 March 2025.

- ^ Alvarado, Daniel. "Production Engineer". slb. Retrieved 6 March 2025.

- ^ Daniel, Alvarado (25 February 2025). "Production Engineer". ACCA Pumps. Retrieved 6 March 2025.

- ^ Johnson, Emily. "Sealing Multiphase Pumping Applications | Seals | Seals". pump-zone.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ "John Crane Seal Sentinel - John Crane Increases Production Capabilities with Machine that Streamlines Four Machining Functions into One". www.sealsentinel.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ "Vacuum pump new on SA market". Engineering News. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ "NPSH: A Comprehensive Guide to Preventing Pump Cavitation". theengineeringguide.com. 11 December 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ a b Crane Engineering. "minimum flow bypass line". Crane Engineering. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Gas Processors Suppliers Association (2004). GPSA Engineering Data Book (12 ed.). Tulsa: GPSA. pp. Chapter 7 Pumps and hydraulic turbines.

- ^ Pump Industry (30 September 2020). "Four methods for maintaining minimum flow conditions". Pump Industry. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ "Máy bơm nước". Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ Shell, Shearwater P&IDs dated 1997

Further reading

[edit]- Australian Pump Manufacturers' Association. Australian Pump Technical Handbook, 3rd edition. Canberra: Australian Pump Manufacturers' Association, 1987. ISBN 0-7316-7043-4.

- Hicks, Tyler G. and Theodore W. Edwards. Pump Application Engineering. McGraw-Hill Book Company.1971. ISBN 0-07-028741-4

- Karassik, Igor, ed. (2007). Pump Handbook (4 ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 9780071460446.

- Robbins, L. B. "Homemade Water Pressure Systems". Popular Science, February 1919, pages 83–84. Article about how a homeowner can easily build a pressurized home water system that does not use electricity.

- A pneumatic diaphragm pump, also known as an air-operated double diaphragm (AODD) pump, is a type of positive displacement pump that uses compressed air as its power source. The pump operates by alternately filling and discharging two flexible diaphragms, which create suction and pressure to transfer liquids web archive Saved 22 times between September 27, 2020 and May 12, 2025.

Fundamentals

Definition and Purpose

A pump is a mechanical device that moves fluids, such as liquids or gases, from one location to another by applying mechanical action, typically converting mechanical energy into hydraulic energy to increase the fluid's pressure or velocity.[1] This process enables the fluid to overcome physical barriers, such as elevation differences or resistance in piping systems.[6] Pumps are essential in various engineering applications, where they facilitate the transfer of fluids within processes or between stages.[8] The term "pump" originates from Middle English "pumpe," adopted in the early 15th century from Middle Dutch "pompe," referring to a device for forcing liquids or air, often used in nautical contexts for expelling bilge water.[9] This etymology reflects early mechanical designs, such as foot-operated or hand-cranked apparatuses for fluid displacement.[10] The primary purposes of pumps include generating flow to transport fluids over distances, pressurizing systems to maintain desired operational levels, elevating fluids against gravity for applications like irrigation or water supply, and ensuring circulation in closed loops such as heating or cooling systems.[11] Unlike fans, which handle low-pressure gas movement, or compressors, which significantly increase the pressure of compressible gases, pumps are primarily designed for incompressible fluids like liquids, where volume changes are minimal.[12] Key fluid properties that influence pump performance and selection include viscosity, which affects flow resistance and energy requirements; density, which determines the mass being moved and thus the power needed; corrosiveness, impacting material compatibility to prevent degradation; and abrasiveness, which can cause wear on internal components from solid particles in the fluid.[13] These properties guide the choice of pump materials and design to ensure reliability and efficiency across industries.[14]Basic Components and Working Principle

A pump typically consists of several core components that facilitate the transfer of fluids. The inlet and outlet ports serve as the entry and exit points for the fluid, allowing it to be drawn in and expelled under pressure.[15] The moving element, which may be an impeller in dynamic pumps or a piston in displacement types, is responsible for imparting energy to the fluid.[15] Surrounding these is the casing or housing, which encloses the internal parts, directs fluid flow, and maintains structural integrity by containing pressure.[15] A shaft connects the moving element to the power source, transmitting rotational or linear motion, while bearings support the shaft to reduce friction and ensure smooth operation.[15] Seals, such as mechanical seals or packing in a stuffing box, are critical for preventing fluid leakage along the shaft and maintaining the necessary pressure differentials between the pump interior and exterior.[15] The working principle of a pump involves the transfer of mechanical energy to the fluid, either by increasing its kinetic energy (velocity) in dynamic pumps or by building pressure through volume displacement in positive displacement pumps. This process adheres to fundamental fluid dynamics principles, such as Bernoulli's principle, which relates pressure, velocity, and elevation in a flowing fluid to conserve energy along a streamline.[16] In operation, the fluid follows a defined path: during the suction phase, it enters through the inlet port due to reduced pressure created by the moving element; this is followed by a compression or acceleration phase where energy is added to the fluid; finally, in the discharge phase, the fluid is expelled through the outlet at higher pressure or velocity.[6] Seals play a vital role in pump efficiency by minimizing leakage, which could otherwise reduce performance and cause energy loss, while also protecting bearings from fluid exposure.[15] Common materials for pump components are selected based on the fluid's properties, such as corrosiveness or temperature; cast iron is widely used for casings in general applications due to its durability and cost-effectiveness, stainless steel for corrosive environments to resist degradation, and plastics like polypropylene for handling aggressive chemicals where metal corrosion is a concern.[17][18]History

Early Inventions and Ancient Uses

One of the earliest known positive displacement pumps, the Archimedes' screw, was invented by the Greek mathematician Archimedes in the 3rd century BCE during his time in Egypt. This device features a helical blade wrapped around a central cylinder, which, when rotated manually or by animal power, traps and lifts water upward along the screw's incline, enabling efficient irrigation in arid regions of ancient Greece and Egypt. Archaeological evidence and historical accounts indicate its widespread use for agricultural water supply, marking a significant advancement in hydraulic technology over simpler methods like buckets or shadufs.[19] In the Hellenistic period, engineer Ctesibius of Alexandria, active in the 3rd century BCE, pioneered the force pump, a piston-driven device that pressurized water to deliver it through nozzles or pipes. This innovation, constructed from bronze cylinders and valves, allowed for directed streams of water under pressure. The Romans adapted and refined these force pumps by the 1st century CE, employing double-acting piston designs for practical applications such as firefighting in urban areas and dewatering mines, where excavated examples from sites like Silchester demonstrate their robust construction for handling abrasive slurries.[20][21] During the medieval period in Europe, suction pumps emerged as a key advancement for accessing groundwater from wells, typically featuring a piston within a cylinder that created a partial vacuum to draw water upward. These devices, often powered by hand, animal, or water wheels, were limited to lifting water no higher than about 10 meters due to atmospheric pressure counteracting the suction, a physical constraint later elucidated by Evangelista Torricelli's 1643 mercury barometer experiment, which quantified air pressure at sea level as equivalent to a 760 mm column of mercury. In the 16th century, Ottoman polymath Taqi al-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf advanced pumping with his six-cylinder reciprocating design, described in his treatise Al-Turuq al-Saniya, which used a water wheel to drive pistons for continuous lifting from rivers, incorporating clack valves and counterweights for steady flow.[22][23] Early pumps found essential applications in water management across civilizations, including lifting for agriculture via screw mechanisms to irrigate fields, dewatering mines with force pumps to access deeper ore deposits, and augmenting aqueduct systems—primarily gravity-fed but supplemented by pumps for elevation changes or maintenance in Roman engineering projects. These pre-modern inventions, reliant on manual or basic mechanical power, established foundational principles that influenced subsequent industrial pump designs.[24]Industrial Developments and Modern Innovations

The Industrial Revolution marked a pivotal era in pump development, beginning with steam-powered innovations in the 18th century that transitioned from manual and animal-powered devices to mechanized systems capable of handling larger volumes for factories, mines, and waterworks. A key early example was Thomas Newcomen's 1712 atmospheric steam engine, adapted to drive piston pumps for mine drainage, enabling deeper mining operations. By the early 19th century, improvements like James Watt's separate condenser enhanced efficiency, powering larger reciprocating pumps for industrial and municipal use.[4] In 1851, British engineer John Appold introduced the curved-vane centrifugal pump at the Great Exhibition in London, achieving an efficiency of approximately 68% and enabling more reliable fluid transport over long distances compared to earlier straight-vane designs.[25] This innovation laid the groundwork for widespread adoption in industrial settings. Concurrently, 19th-century engineers advanced rotary pumps, with notable contributions including the rotary gear pump developed by J. & E. Hall in 1850, which improved sealing and reduced leakage for viscous fluids in emerging chemical and food processing industries.[5] The 20th century brought electrification and specialized designs that expanded pump applications in energy, oil, and remote operations. Post-1900, integration of electric motors revolutionized pump operation, with Hayward Tyler producing the first submersible electric motor-pump in 1908, allowing for compact, reliable performance without external drive shafts.[25] Submersible pumps gained prominence in the 1920s, pioneered by Armais Arutunoff's electric submersible pump invented in 1916 and commercialized by REDA Pump in 1928, facilitating deep-well oil extraction and wastewater handling.[26] Jet pumps, introduced in the early 1930s, offered a no-moving-parts solution for remote and offshore applications, using high-velocity fluid jets to create suction for lifting oil in mature fields without electrical components.[27] Key milestones included the establishment of the American Petroleum Institute (API) in 1919, which developed standards like API 610 for centrifugal pumps in the oil industry, ensuring interoperability and safety in refining operations.[28] In the 1960s, NASA's space program advanced cryogenic pumps for rocket propulsion, with turbopump developments at Lewis Research Center achieving high-flow rates for liquid hydrogen and oxygen, influencing industrial designs for liquefied gas handling.[29] Modern innovations since the late 20th century emphasize efficiency, customization, and intelligence, driven by digital and materials advancements. Variable frequency drives (VFDs), popularized in the 1980s, adjust pump motor speeds to match demand, reducing energy consumption by up to 50% in variable-load systems like HVAC and water distribution.[30] Additive manufacturing has enabled 3D-printed impellers, as demonstrated by Shell's 2022 deployment of a customized titanium impeller for a centrifugal pump, cutting production time from weeks to days while optimizing fluid dynamics for specific corrosive environments.[31] Smart pumps incorporating IoT sensors for real-time monitoring emerged in the 2010s, enabling predictive maintenance through vibration and temperature analysis, which can extend equipment life by 20-30% and minimize downtime in industrial processes.[32] Materials science has transformed pump durability, shifting from traditional metals to advanced composites and ceramics for extreme conditions. Since the 1990s, ceramic coatings and silicon carbide composites have been adopted for impellers and casings in high-temperature (up to 1600°C) and corrosive applications, such as chemical processing and power generation, offering superior wear resistance and reducing maintenance frequency by factors of 2-5 compared to steel.[33] This evolution, informed by aerospace research, allows pumps to operate in aggressive media like acids and slurries without degradation.Classification and Types

Positive Displacement Pumps

Positive displacement pumps operate by trapping a fixed volume of fluid within a chamber and then forcing that volume into the discharge line, delivering a nearly constant flow rate irrespective of the system's discharge pressure. This mechanism makes them particularly suitable for handling viscous, shear-sensitive, or abrasive fluids where consistent metering is required. Unlike dynamic pumps, which rely on kinetic energy to impart variable flow based on pressure changes, positive displacement pumps ensure predictable output for applications demanding precision.[34] These pumps are categorized into reciprocating and rotary subtypes, with peristaltic pumps forming a specialized rotary variant. Reciprocating pumps, such as piston and diaphragm types, use a back-and-forth motion to displace fluid; piston pumps feature a cylinder and plunger for direct compression, while diaphragm pumps employ a flexible membrane to isolate the fluid from mechanical parts, ideal for corrosive or hazardous media. Rotary pumps, including gear, screw, lobe, and vane designs, utilize rotating elements to trap and move fluid pockets; for instance, gear pumps mesh two rotating gears to convey fluid between teeth, screw pumps employ intermeshing screws for axial flow, lobe pumps use non-contacting lobes to minimize shear, and vane pumps rely on sliding vanes in a rotor for volumetric displacement. Peristaltic pumps, a rotary subtype, compress a flexible tube with rollers or shoes to propel fluid, ensuring no contact between the pump mechanism and the fluid for sterile applications.[34][35][36] Operationally, reciprocating pumps often produce pulsating flow due to their cyclic motion, which can be smoothed with pulsation dampeners, while rotary pumps deliver smoother, more continuous output. Many positive displacement pumps exhibit self-priming capability, allowing them to evacuate air from the suction line and start pumping without external priming. They tolerate high pressures, with some designs like plunger pumps achieving up to 1000 bar (14,500 psi) for demanding industrial uses, though they require safety valves or relief systems to prevent overpressurization from their incompressible flow nature. However, certain rotary types, such as gear pumps, can introduce shear to sensitive fluids, potentially degrading them.[34][37][38] The primary advantages of positive displacement pumps include their ability to handle high-viscosity fluids effectively, provide precise volumetric control for metering, and operate reliably at low speeds without cavitation issues common in dynamic pumps. Peristaltic variants excel in sterile environments by preventing contamination, as the fluid contacts only the disposable tubing. Disadvantages encompass higher maintenance needs due to close tolerances and wear on moving parts, potential pulsation in reciprocating models leading to vibration, and lower overall efficiency compared to dynamic pumps at high flows. Safety valves are essential to mitigate risks from excessive pressure buildup.[34][39] Specific examples illustrate their versatility: gear pumps are widely used for lubricating oils in machinery due to their compact design and ability to handle viscosities up to 100,000 cSt, while diaphragm pumps serve in water treatment for metering corrosive chemicals like sodium hypochlorite, leveraging their leak-proof operation and compatibility with aggressive media.[34][40]Dynamic Pumps

Dynamic pumps, also known as rotodynamic or velocity pumps, accelerate fluid through the rotation of an impeller to impart kinetic energy, which is then converted into pressure energy as the fluid slows in the pump's volute or diffuser casing.[15] This mechanism enables continuous fluid movement without direct contact between moving parts and the fluid, distinguishing them from other pump categories.[41] The main subtypes of dynamic pumps are centrifugal, axial-flow, and mixed-flow designs, each tailored to specific hydraulic requirements based on flow direction relative to the impeller shaft. Centrifugal pumps feature radial flow, where fluid enters axially along the shaft and exits perpendicularly at the impeller periphery, making them ideal for medium-head applications with moderate flow volumes.[15] Axial-flow pumps use a propeller-style impeller to propel fluid parallel to the shaft, achieving high flow rates at low heads for scenarios demanding rapid, large-scale transfer.[15] Mixed-flow pumps hybridize these approaches, with fluid exiting the impeller at an oblique angle between radial and axial, offering balanced performance for intermediate head and flow needs.[15] Dynamic pumps provide smooth, non-pulsating flow due to their continuous kinetic energy transfer, with operational efficiency peaking at the best efficiency point (BEP) on their performance curve, typically corresponding to the design flow rate.[15] A key operational concern is cavitation, which occurs when local pressure drops below the fluid's vapor pressure, forming and collapsing vapor bubbles that erode the impeller; this risk intensifies if the net positive suction head available (NPSHA) falls below the pump's required NPSH (NPSHR).[42] These pumps excel in delivering high flow rates—reaching up to 70,000 m³/h in large axial-flow models—but struggle with viscous fluids due to increased frictional losses and reduced efficiency, often necessitating positive displacement alternatives for such media.[43] Additional drawbacks include the requirement for priming to remove air from the suction line before operation and vulnerability to performance degradation from solids or abrasives.[44] Representative applications highlight their versatility: radial-flow centrifugal pumps circulate chilled or heated water in HVAC systems for efficient building climate control.[45] Axial-flow pumps support flood control and large-scale irrigation by rapidly displacing vast water volumes in low-lift scenarios, such as river diversion or agricultural flooding.[46]Specialty and Historical Pumps

Electromagnetic pumps operate by generating a Lorentz force through the interaction of an electric current and a magnetic field applied perpendicularly to a conductive fluid, such as liquid metals, propelling the fluid without any moving parts.[47] This design is particularly suited for handling corrosive or high-temperature fluids in specialized environments, including nuclear reactors where they circulate alkali or heavy liquid metal coolants like sodium or lead.[48] In AC electromagnetic pumps, fluctuating fields induce the Lorentz body force to drive liquid metal flow, offering advantages in reliability due to the absence of mechanical seals or bearings.[49] Impulse pumps, exemplified by the hydraulic ram, harness the water hammer effect—created by the sudden deceleration of flowing water—to generate pressure pulses that elevate a portion of the water to a higher outlet without external energy input.[50] The device relies on the kinetic energy from a continuous water supply with a vertical drop, where a check valve closes abruptly to build pressure, delivering intermittent lifts up to several times the supply head while wasting excess flow through a bypass.[51] This low-maintenance mechanism has been used historically for rural water supply, achieving elevation gains of 10-20 meters or more depending on the drive head and valve timing.[51] Gravity pumps encompass simple designs that leverage gravitational potential and atmospheric pressure for fluid transfer, such as siphon systems where liquid rises in a tube due to negative pressure and flows downhill to a lower outlet, enabling transfer over barriers without mechanical aid.[52] Traditional siphons, known since ancient times, function effectively for clear liquids like water as long as the inlet is submerged and the outlet remains below the source level, with practical lifts limited to about 10 meters by atmospheric pressure.[52] Bucket elevators, another gravity-assisted variant, employ a continuous chain or belt with attached buckets to scoop and elevate water from a lower reservoir, often powered manually or by animal traction in historical agricultural settings for irrigation lifting.[53] Steam pumps, typically reciprocating types, utilize steam pressure to drive a piston connected to a liquid cylinder, alternately drawing in and expelling fluid through valves, and were pivotal in 19th-century industrial applications like mine dewatering.[54] These direct-acting engines converted steam's expansive force into mechanical reciprocation, handling large volumes of water from deep shafts—up to 100 meters or more—with efficiencies improved by innovations like the Cornish engine, which used high-pressure steam for greater output.[55] By the mid-1800s, they powered key mining operations in regions like Cornwall and Pennsylvania, facilitating coal and metal extraction by removing floodwater continuously. Valveless pumps, including jet and regenerative designs, achieve continuous, pulsation-free flow by exploiting fluid momentum or impeller recirculation, making them ideal for sensitive applications like medical devices where steady delivery is critical.[56] Jet valveless pumps use a high-velocity motive fluid stream to entrain and propel secondary fluid via momentum transfer, eliminating valves to reduce clotting risks in biomedical circuits.[56] Regenerative variants, often with peripheral impeller channels, recirculate fluid multiple times for low-flow precision, as seen in biohybrid systems for circulatory support that mimic natural pulsatile action without mechanical valves.[57] These pumps provide uniform flow rates as low as microliters per minute, enhancing reliability in implantable devices for drug delivery or organ assistance.[58] Historically, eductor-jet pumps employed the Venturi effect, where a high-velocity jet through a converging-diverging nozzle creates low pressure to draw in and mix secondary fluid, enabling suction without moving parts for tasks like dredging or tank emptying.[59] Developed in the 19th century for naval and industrial use, these pumps transferred energy from a pressurized motive fluid to the suction stream, achieving flow multiplication factors of 3-5 times the jet volume in applications requiring gentle handling of slurries.[59] Regenerative turbine pumps, with roots in early 20th-century designs, feature tangential fluid entry and multiple impeller passages for repeated energy addition, excelling in low-flow, high-pressure scenarios with heads up to 700 feet (213 meters).[60] Their precision stems from the impeller's peripheral vanes, which impart incremental velocity boosts, making them suitable for boiler feed or chemical dosing where steady, low-volume output is essential.[61]Operating Principles

Pumping Power and Energy Requirements

The hydraulic power imparted to a fluid by a pump represents the theoretical energy required to move the fluid against the total dynamic head, calculated as , where is the fluid density (kg/m³), is the acceleration due to gravity (9.81 m/s²), is the volumetric flow rate (m³/s), and is the total head (m).[62] This formula arises from the fundamental principle of work done on the fluid, equivalent to the rate at which potential energy is increased to overcome the head, which encompasses static elevation differences, frictional losses in the system, and velocity head at the discharge.[63] The actual mechanical power input to the pump, known as brake horsepower (BHP), accounts for losses within the pump and is determined by dividing the hydraulic power by the pump efficiency.[62] Pumps are commonly driven by electric motors, which provide reliable and efficient power conversion from electrical energy; internal combustion engines, such as diesel types, for applications requiring portability or backup; or steam turbines, particularly in industrial settings with available steam supply.[64] To aid in selecting an appropriate pump type that matches power requirements, the dimensionless specific speed is used, where is the rotational speed (rpm) and and are at the best efficiency point; this parameter helps characterize impeller geometry and predict performance across similar designs.[65] Several factors influence the overall power demands, including fluid properties like density, which directly scales the hydraulic power, and viscosity, which increases frictional losses; additionally, system losses such as pipe friction contribute to the total head and are quantified using the Darcy-Weisbach equation , where is the friction factor, is pipe length, is diameter, and is fluid velocity.[66] Power is typically expressed in kilowatts (kW) in SI units or horsepower (hp) in imperial units, with 1 hp ≈ 0.746 kW. For example, pumping 100 m³/h of water (ρ = 1000 kg/m³) at a 50 m head yields a hydraulic power of approximately 13.6 kW, computed as .[63]Efficiency and Performance Metrics

Pumps are evaluated based on several efficiency metrics that quantify their ability to convert input energy into useful hydraulic work while minimizing losses. Volumetric efficiency measures the accuracy of flow delivery, defined as the ratio of actual output flow rate to the theoretical displacement volume, accounting for internal leakage in positive displacement pumps.[67] Hydraulic efficiency assesses the effectiveness of energy transfer from the impeller or piston to the fluid, reflecting losses due to friction and turbulence in the pump's flow path.[68] Overall efficiency, often termed wire-to-water efficiency (WWE), encompasses the combined losses from the motor, pump, and drive system, representing the total input electrical power versus the hydraulic output power.[69] The hydraulic efficiency is calculated using the formula: where is the fluid density, is gravitational acceleration, is the flow rate, is the total head, and is the shaft power input to the pump.[63] This metric peaks at a specific flow rate on the efficiency curve, typically reaching 70-90% for well-designed centrifugal pumps operating near their optimal conditions.[3] Overall efficiency incorporates motor losses and is expressed similarly but uses electrical input power , often achieving 50-80% in practical systems depending on size and load.[70] Performance is graphically represented through characteristic curves that plot key parameters against flow rate. The head-capacity (H-Q) curve illustrates the pump's ability to generate pressure head at varying flows, decreasing nonlinearly from shutoff head to maximum capacity.[71] The efficiency curve overlays the percentage efficiency, peaking at the best efficiency point (BEP), where the pump operates with minimal energy waste and vibration.[72] The power curve shows input power requirements, which generally increase with flow, aiding in motor sizing. Operating at or near the BEP—typically 70-120% of the BEP flow—maximizes longevity and energy savings.[73] Several factors can degrade efficiency when pumps deviate from design conditions. Cavitation occurs when local pressure drops cause vapor bubbles to form and collapse, eroding impellers and reducing hydraulic output by up to 20-30% while increasing noise and vibration.[42] Recirculation at low flow rates (below 50-70% of BEP) leads to internal flow instabilities, causing energy dissipation through eddies and further lowering efficiency by 10-15%. These phenomena highlight the importance of matching pump selection to system demands. Standardized testing ensures reliable performance metrics. The ISO 9906 standard outlines procedures for hydraulic acceptance tests on rotodynamic pumps, specifying grades 1, 2, and 3 tolerances for head, flow, and efficiency measurements, with grade 1 allowing no more than 3% deviation at BEP.[74] Wire-to-water efficiency is increasingly mandated for energy labeling under regulations like those from the U.S. Department of Energy, targeting minimum thresholds for circulator pumps with compliance required starting in 2028 to promote high-efficiency models.[75]Startup Procedures and Safety Considerations

Proper startup of pumps requires meticulous preparation to ensure reliable operation and prevent mechanical failures. For non-self-priming centrifugal pumps, priming is essential, involving the filling of the pump casing and suction line with fluid to expel air and avoid air locks that could impair performance.[76] This process typically includes opening the suction valve and venting air from the highest points in the casing until a steady flow of liquid is observed, as incomplete priming can lead to cavitation.[77] The startup sequence begins with verifying mechanical alignments, such as shaft coupling and base leveling within tolerances like 0.002 inches per foot, to mitigate vibration and misalignment issues.[78] Air vents are then opened to release trapped gases, followed by a gradual increase in pump speed after confirming that the net positive suction head available (NPSHA) exceeds the required (NPSHR) by a safety margin of 0.5 to 1 meter to prevent cavitation, which forms vapor bubbles that collapse and erode components.[79] For API 610-compliant centrifugal pumps used in petroleum applications, additional pre-startup checks include flushing auxiliary systems, testing instrumentation, and ensuring proper rotation direction to avoid reverse operation that could cause internal damage.[78] Safety considerations are paramount, particularly for positive displacement pumps, where blocked discharge lines during startup can cause rapid overpressure buildup due to their fixed-volume delivery mechanism, necessitating the installation of relief valves typically set to activate at 10% above the maximum operating pressure.[80] These valves divert excess flow back to the suction side, preventing structural failure or injury from high-pressure releases.[81] Dry running poses another critical risk for both pump types, as the absence of fluid leads to overheating and seal failure without lubrication; positive displacement pumps, with their tight tolerances, can only tolerate brief dry operation—typically minutes—before friction causes irreversible wear.[82] Thermal expansion during startup of hot fluid systems can exacerbate misalignment if not accounted for, potentially damaging bearings and seals if the pump is started before reaching thermal equilibrium.[83] Behavioral differences between pump types influence safe startup practices: positive displacement pumps generate increasing pressure against no-flow conditions, risking overpressure without relief, whereas dynamic pumps like centrifugals draw minimal power at shutoff and require minimum flow to avoid overheating but do not build pressure similarly.[84] Poor startup procedures, such as inadequate NPSH management, can induce cavitation that significantly reduces efficiency by up to 20-30% in severe cases.[79] Regulatory compliance enhances safety, with OSHA standard 1910.147 mandating lockout/tagout procedures to isolate energy sources before pump startup or maintenance, including shutdown, application of lockout devices, and verification of zero energy to prevent unexpected energization.[85] For petroleum service, API 610 outlines rigorous installation and commissioning protocols, including vibration monitoring and seal integrity checks during initial operation to ensure long-term reliability.[78]Applications

Water Supply and Irrigation Systems