Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Siphon

View on Wikipedia

A siphon (from Ancient Greek σίφων (síphōn) 'pipe, tube'; also spelled syphon) is any of a wide variety of devices that involve the flow of liquids through tubes. In a narrower sense, the word refers particularly to a tube in an inverted "U" shape, which causes a liquid to flow upward, above the surface of a reservoir, with no pump, but powered by the fall of the liquid as it flows down the tube under the pull of gravity, then discharging at a level lower than the surface of the reservoir from which it came.

There are two leading theories about how siphons cause liquid to flow uphill, against gravity, without being pumped, and powered only by gravity. The traditional theory for centuries was that gravity pulling the liquid down on the exit side of the siphon resulted in reduced pressure at the top of the siphon. Then atmospheric pressure was able to push the liquid from the upper reservoir, up into the reduced pressure at the top of the siphon, like in a barometer or drinking straw, and then over.[1][2][3][4] However, it has been demonstrated that siphons can operate in a vacuum[4][5][6][7] and to heights exceeding the barometric height of the liquid.[4][5][8] Consequently, the cohesion tension theory of siphon operation has been advocated, where the liquid is pulled over the siphon in a way similar to the chain fountain.[9] It need not be one theory or the other that is correct, but rather both theories may be correct in different circumstances of ambient pressure. The atmospheric pressure with gravity theory cannot explain siphons in vacuum, where there is no significant atmospheric pressure. But the cohesion tension with gravity theory cannot explain CO2 gas siphons,[10] siphons working despite bubbles, and the flying droplet siphon, where gases do not exert significant pulling forces, and liquids not in contact cannot exert a cohesive tension force.

All known published theories in modern times recognize Bernoulli's equation as a decent approximation to idealized, friction-free siphon operation.

History

[edit]

Egyptian reliefs from 1500 BC depict siphons used to extract liquids from large storage jars.[11][12]

Physical evidence for the use of siphons by Greeks are the Justice cup of Pythagoras in Samos in the 6th century BC and usage by Greek engineers in the 3rd century BC at Pergamon.[12][13]

Hero of Alexandria wrote extensively about siphons in the treatise Pneumatica.[14]

The Banu Musa brothers of 9th-century Baghdad invented a double-concentric siphon, which they described in their Book of Ingenious Devices.[15][16] The edition edited by Hill includes an analysis of the double-concentric siphon.

Siphons were studied further in the 17th century, in the context of suction pumps (and the recently developed vacuum pumps), particularly with an eye to understanding the maximum height of pumps (and siphons) and the apparent vacuum at the top of early barometers. This was initially explained by Galileo Galilei via the theory of horror vacui ("nature abhors a vacuum"), which dates to Aristotle, and which Galileo restated as resintenza del vacuo, but this was subsequently disproved by later workers, notably Evangelista Torricelli and Blaise Pascal[17] – see barometer: history.

Theory

[edit]A practical siphon, operating at typical atmospheric pressures and tube heights, works because gravity pulling down on the taller column of liquid leaves reduced pressure at the top of the siphon (formally, hydrostatic pressure when the liquid is not moving). This reduced pressure at the top means gravity pulling down on the shorter column of liquid is not sufficient to keep the liquid stationary against the atmospheric pressure pushing it up into the reduced-pressure zone at the top of the siphon. So the liquid flows from the higher-pressure area of the upper reservoir up to the lower-pressure zone at the top of the siphon, over the top, and then, with the help of gravity and a taller column of liquid, down to the higher-pressure zone at the exit.[2][18]

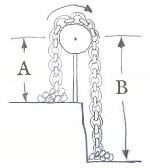

The chain model is a useful but not completely accurate conceptual model of a siphon. The chain model helps to understand how a siphon can cause liquid to flow uphill, powered only by the downward force of gravity. A siphon can sometimes be thought of like a chain hanging over a pulley, with one end of the chain piled on a higher surface than the other. Since the length of chain on the shorter side is lighter than the length of chain on the taller side, the heavier chain on the taller side will move down and pull up the chain on the lighter side. Similar to a siphon, the chain model is obviously just powered by gravity acting on the heavier side, and there is clearly no violation of conservation of energy, because the chain is ultimately just moving from a higher to a lower location, as the liquid does in a siphon.

There are a number of problems with the chain model of a siphon, and understanding these differences helps to explain the actual workings of siphons. First, unlike in the chain model of the siphon, it is not actually the weight on the taller side compared to the shorter side that matters. Rather it is the difference in height from the reservoir surfaces to the top of the siphon, that determines the balance of pressure. For example, if the tube from the upper reservoir to the top of the siphon has a much larger diameter than the taller section of tube from the lower reservoir to the top of the siphon, the shorter upper section of the siphon may have a much larger weight of liquid in it, and yet the lighter volume of liquid in the down tube can pull liquid up the fatter up tube, and the siphon can function normally.[19]

Another difference is that under most practical circumstances, dissolved gases, vapor pressure, and (sometimes) lack of adhesion with tube walls, conspire to render the tensile strength within the liquid ineffective for siphoning. Thus, unlike a chain, which has significant tensile strength, liquids usually have little tensile strength under typical siphon conditions, and therefore the liquid on the rising side cannot be pulled up in the way the chain is pulled up on the rising side.[7][18]

An occasional misunderstanding of siphons is that they rely on the tensile strength of the liquid to pull the liquid up and over the rise.[2][18] While water has been found to have a significant tensile strength in some experiments (such as with the z-tube[20]), and siphons in vacuum rely on such cohesion, common siphons can easily be demonstrated to need no liquid tensile strength at all to function.[7][2][18] Furthermore, since common siphons operate at positive pressures throughout the siphon, there is no contribution from liquid tensile strength, because the molecules are actually repelling each other in order to resist the pressure, rather than pulling on each other.[7]

To demonstrate, the longer lower leg of a common siphon can be plugged at the bottom and filled almost to the crest with liquid as in the figure, leaving the top and the shorter upper leg completely dry and containing only air. When the plug is removed and the liquid in the longer lower leg is allowed to fall, the liquid in the upper reservoir will then typically sweep the air bubble down and out of the tube. The apparatus will then continue to operate as a normal siphon. As there is no contact between the liquid on either side of the siphon at the beginning of this experiment, there can be no cohesion between the liquid molecules to pull the liquid over the rise. It has been suggested by advocates of the liquid tensile strength theory, that the air start siphon only demonstrates the effect as the siphon starts, but that the situation changes after the bubble is swept out and the siphon achieves steady flow. But a similar effect can be seen in the flying-droplet siphon (see above). The flying-droplet siphon works continuously without liquid tensile strength pulling the liquid up.

The siphon in the video demonstration operated steadily for more than 28 minutes until the upper reservoir was empty. Another simple demonstration that liquid tensile strength is not needed in the siphon is to simply introduce a bubble into the siphon during operation. The bubble can be large enough to entirely disconnect the liquids in the tube before and after the bubble, defeating any liquid tensile strength, and yet if the bubble is not too big, the siphon will continue to operate with little change as it sweeps the bubble out.

Another common misconception about siphons is that because the atmospheric pressure is virtually identical at the entrance and exit, the atmospheric pressure cancels, and therefore atmospheric pressure cannot be pushing the liquid up the siphon. But equal and opposite forces may not completely cancel if there is an intervening force that counters some or all of one of the forces. In the siphon, the atmospheric pressure at the entrance and exit are both lessened by the force of gravity pulling down the liquid in each tube, but the pressure on the down side is lessened more by the taller column of liquid on the down side. In effect, the atmospheric pressure coming up the down side does not entirely "make it" to the top to cancel all of the atmospheric pressure pushing up the up side. This effect can be seen more easily in the example of two carts being pushed up opposite sides of a hill. As shown in the diagram, even though the person on the left seems to have his push canceled entirely by the equal and opposite push from the person on the right, the person on the left's seemingly canceled push is still the source of the force to push the left cart up.

In some situations siphons do function in the absence of atmospheric pressure and due to tensile strength – see vacuum siphons – and in these situations the chain model can be instructive. Further, in other settings water transport does occur due to tension, most significantly in transpirational pull in the xylem of vascular plants.[2][21] Water and other liquids may seem to have no tensile strength because when a handful is scooped up and pulled on, the liquids narrow and pull apart effortlessly. But liquid tensile strength in a siphon is possible when the liquid adheres to the tube walls and thereby resists narrowing. Any contamination on the tube walls, such as grease or air bubbles, or other minor influences such as turbulence or vibration, can cause the liquid to detach from the walls and lose all tensile strength.

In more detail, one can look at how the hydrostatic pressure varies through a static siphon, considering in turn the vertical tube from the top reservoir, the vertical tube from the bottom reservoir, and the horizontal tube connecting them (assuming a U-shape). At liquid level in the top reservoir, the liquid is under atmospheric pressure, and as one goes up the siphon, the hydrostatic pressure decreases (under vertical pressure variation), since the weight of atmospheric pressure pushing the water up is counterbalanced by the column of water in the siphon pushing down (until one reaches the maximal height of a barometer/siphon, at which point the liquid cannot be pushed higher) – the hydrostatic pressure at the top of the tube is then lower than atmospheric pressure by an amount proportional to the height of the tube. Doing the same analysis on the tube rising from the lower reservoir yields the pressure at the top of that (vertical) tube; this pressure is lower because the tube is longer (there is more water pushing down), and requires that the lower reservoir is lower than the upper reservoir, or more generally that the discharge outlet simply be lower than the surface of the upper reservoir. Considering now the horizontal tube connecting them, one sees that the pressure at the top of the tube from the top reservoir is higher (since less water is being lifted), while the pressure at the top of the tube from the bottom reservoir is lower (since more water is being lifted), and since liquids move from high pressure to low pressure, the liquid flows across the horizontal tube from the top basin to the bottom basin. The liquid is under positive pressure (compression) throughout the tube, not tension.

Bernoulli's equation is considered in the scientific literature to be a fair approximation to the operation of the siphon. In non-ideal fluids, compressibility, tensile strength and other characteristics of the working fluid (or multiple fluids) complicate Bernoulli's equation.

Once started, a siphon requires no additional energy to keep the liquid flowing up and out of the reservoir. The siphon will draw liquid out of the reservoir until the level falls below the intake, allowing air or other surrounding gas to break the siphon, or until the outlet of the siphon equals the level of the reservoir, whichever comes first.

In addition to atmospheric pressure, the density of the liquid, and gravity, the maximal height of the crest in practical siphons is limited by the vapour pressure of the liquid. When the pressure within the liquid drops to below the liquid's vapor pressure, tiny vapor bubbles can begin to form at the high point, and the siphon effect will end. This effect depends on how efficiently the liquid can nucleate bubbles; in the absence of impurities or rough surfaces to act as easy nucleation sites for bubbles, siphons can temporarily exceed their standard maximal height during the extended time it takes bubbles to nucleate. One siphon of degassed water was demonstrated to 24 m (79 feet) for an extended period of time[8] and other controlled experiments to 10 m (33 feet).[22] For water at standard atmospheric pressure, the maximal siphon height is approximately 10 m (33 feet); for mercury it is 76 cm (30 inches), which is the definition of standard pressure. This equals the maximal height of a suction pump, which operates by the same principle.[17][23] The ratio of heights (about 13.6) equals the ratio of densities of water and mercury (at a given temperature), since the column of water (resp. mercury) is balancing with the column of air yielding atmospheric pressure, and indeed maximal height is (neglecting vapor pressure and velocity of liquid) inversely proportional to density of liquid.

Modern research into the operation of the siphon

[edit]In 1948, Malcolm Nokes investigated siphons working in both air pressure and in a partial vacuum; for siphons in vacuum he concluded: "The gravitational force on the column of liquid in the downtake tube less the gravitational force in the uptake tube causes the liquid to move. The liquid is therefore in tension and sustains a longitudinal strain which, in the absence of disturbing factors, is insufficient to break the column of liquid". But for siphons of small uptake height working at atmospheric pressure, he wrote: "... the tension of the liquid column is neutralized and reversed by the compressive effect of the atmosphere on the opposite ends of the liquid column."[7]

Potter and Barnes at the University of Edinburgh revisited siphons in 1971. They re-examined the theories of the siphon and ran experiments on siphons in air pressure. They concluded: "By now it should be clear that, despite a wealth of tradition, the basic mechanism of a siphon does not depend upon atmospheric pressure."[24]

Gravity, pressure and molecular cohesion were the focus of work in 2010 by Hughes at the Queensland University of Technology. He used siphons at air pressure and his conclusion was: "The flow of water out of the bottom of a siphon depends on the difference in height between the inflow and outflow, and therefore cannot be dependent on atmospheric pressure…"[21] Hughes did further work on siphons at air pressure in 2011 and concluded: "The experiments described above demonstrate that ordinary siphons at atmospheric pressure operate through gravity and not atmospheric pressure".[25]

The father and son researchers Ramette and Ramette successfully siphoned carbon dioxide under air pressure in 2011 and concluded that molecular cohesion is not required for the operation of a siphon, but: "The basic explanation of siphon action is that, once the tube is filled, the flow is initiated by the greater pull of gravity on the fluid on the longer side compared with that on the short side. This creates a pressure drop throughout the siphon tube, in the same sense that 'sucking' on a straw reduces the pressure along its length all the way to the intake point. The ambient atmospheric pressure at the intake point responds to the reduced pressure by forcing the fluid upwards, sustaining the flow, just as in a steadily sucked straw in a milkshake."[1]

Again in 2011, Richert and Binder (at the University of Hawaii) examined the siphon and concluded that molecular cohesion is not required for the operation of a siphon but relies upon gravity and a pressure differential, writing: "As the fluid initially primed on the long leg of the siphon rushes down due to gravity, it leaves behind a partial vacuum that allows pressure on the entrance point of the higher container to push fluid up the leg on that side".[2]

The research team of Boatwright, Puttick, and Licence, all at the University of Nottingham, succeeded in running a siphon in high vacuum, also in 2011. They wrote: "It is widely believed that the siphon is principally driven by the force of atmospheric pressure. An experiment is described that shows that a siphon can function even under high-vacuum conditions. Molecular cohesion and gravity are shown to be contributing factors in the operation of a siphon; the presence of a positive atmospheric pressure is not required".[26]

Writing in Physics Today in 2011, J. Dooley from Millersville University stated that both a pressure differential within the siphon tube and the tensile strength of the liquid are required for a siphon to operate.[27]

A researcher at Humboldt State University, A. McGuire, examined flow in siphons in 2012. Using the advanced general-purpose multiphysics simulation software package LS-DYNA he examined pressure initialisation, flow, and pressure propagation within a siphon. He concluded: "Pressure, gravity and molecular cohesion can all be driving forces in the operation of siphons".[3]

In 2014, Hughes and Gurung (at the Queensland University of Technology) ran a water siphon under varying air pressures ranging from sea level to 11.9 km (39000 ft) altitude. They noted: "Flow remained more or less constant during ascension indicating that siphon flow is independent of ambient barometric pressure". They used Bernoulli's equation and the Poiseuille equation to examine pressure differentials and fluid flow within a siphon. Their conclusion was: "It follows from the above analysis that there must be a direct cohesive connection between water molecules flowing in and out of a siphon. This is true at all atmospheric pressures in which the pressure in the apex of the siphon is above the vapour pressure of water, an exception being ionic liquids".[28]

Practical requirements

[edit]A plain tube can be used as a siphon. An external pump has to be applied to start the liquid flowing and prime the siphon (in home use this is often done by a person inhaling through the tube until enough of it has filled with liquid; this may pose danger to the user, depending on the liquid that is being siphoned). This is sometimes done with any leak-free hose to siphon gasoline from a motor vehicle's gasoline tank to an external tank. (Siphoning gasoline by mouth often results in the accidental swallowing of gasoline, or aspirating it into the lungs, which can cause death or lung damage.[29]) If the tube is flooded with liquid before part of the tube is raised over the intermediate high point and care is taken to keep the tube flooded while it is being raised, no pump is required. Devices sold as siphons often come with a siphon pump to start the siphon process.

In some applications it can be helpful to use siphon tubing that is not much larger than necessary. Using piping of too great a diameter and then throttling the flow using valves or constrictive piping appears to increase the effect of previously cited concerns over gases or vapor collecting in the crest which serve to break the vacuum. If the vacuum is reduced too much, the siphon effect can be lost. Reducing the size of pipe used closer to requirements appears to reduce this effect and creates a more functional siphon that does not require constant re-priming and restarting. In this respect, where the requirement is to match a flow into a container with a flow out of said container (to maintain a constant level in a pond fed by a stream, for example) it would be preferable to utilize two or three smaller separate parallel pipes that can be started as required rather than attempting to use a single large pipe and attempting to throttle it.

Automatic intermittent siphon

[edit]Siphons are sometimes employed as automatic machines, in situations where it is desirable to turn a continuous trickling flow or an irregular small surge flow into a large surge volume. A common example of this is a public restroom with urinals regularly flushed by an automatic siphon in a small water tank overhead. When the container is filled, all the stored liquid is released, emerging as a large surge volume that then resets and fills again. One way to do this intermittent action involves complex machinery such as floats, chains, levers, and valves, but these can corrode, wear out, or jam over time. An alternate method is with rigid pipes and chambers, using only the water itself in a siphon as the operating mechanism.

A siphon used in an automatic unattended device needs to be able to function reliably without failure. This is different from the common demonstration self-starting siphons in that there are ways the siphon can fail to function which require manual intervention to return to normal surge flow operation. A video demonstration of a self-starting siphon can be found here, courtesy of The Curiosity Show.

The most common failure is for the liquid to dribble out slowly, matching the rate that the container is filling, and the siphon enters an undesired steady-state condition. Preventing dribbling typically involves pneumatic principles to trap one or more large air bubbles in various pipes, which are sealed by water traps. This method can fail if it cannot start working intermittently without water already present in parts of the mechanism, and which will not be filled if the mechanism starts from a dry state.

A second problem is that the trapped air pockets will shrink over time if the siphon is not operating due to no inflow. The air in pockets is absorbed by the liquid, which pulls liquid up into the piping until the air pocket disappears, and can cause activation of water flow outside the normal range of operating when the storage tank is not full, leading to loss of the liquid seal in lower parts of the mechanism.

A third problem is where the lower end of the liquid seal is simply a U-trap bend in an outflow pipe. During vigorous emptying, the kinetic motion of the liquid out the outflow can propel too much liquid out, causing a loss of the sealing volume in the outflow trap and loss of the trapped air bubble to maintain intermittent operation.

A fourth problem involves seep holes in the mechanism, intended to slowly refill these various sealing chambers when the siphon is dry. The seep holes can be plugged by debris and corrosion, requiring manual cleaning and intervention. To prevent this, the siphon may be restricted to pure liquid sources, free of solids or precipitate.

Many automatic siphons have been invented going back to at least the 1850s, for automatic siphon mechanisms that attempt to overcome these problems using various pneumatic and hydrodynamic principles.

Applications and terminology

[edit]

When certain liquids needs to be purified, siphoning can help prevent either the bottom (dregs) or the top (foam and floaties) from being transferred out of one container into a new container. Siphoning is thus useful in the fermentation of wine and beer for this reason, since it can keep unwanted impurities out of the new container.

Self-constructed siphons, made of pipes or tubes, can be used to evacuate water from cellars after floodings. Between the flooded cellar and a deeper place outside a connection is built, using a tube or some pipes. They are filled with water through an intake valve (at the highest end of the construction). When the ends are opened, the water flows through the pipe into the sewer or the river.

Siphoning is common in irrigated fields to transfer a controlled amount of water from a ditch, over the ditch wall, into furrows.

Large siphons may be used in municipal waterworks and industry. Their size requires control via valves at the intake, outlet and crest of the siphon. The siphon may be primed by closing the intake and outlets and filling the siphon at the crest. If intakes and outlets are submerged, a vacuum pump may be applied at the crest to prime the siphon. Alternatively the siphon may be primed by a pump at either the intake or outlet. Gas in the liquid is a concern in large siphons.[30] The gas tends to accumulate at the crest and if enough accumulates to break the flow of liquid, the siphon stops working. The siphon itself will exacerbate the problem because as the liquid is raised through the siphon, the pressure drops, causing dissolved gases within the liquid to come out of solution. Higher temperature accelerates the release of gas from liquids so maintaining a constant, low temperature helps. The longer the liquid is in the siphon, the more gas is released, so a shorter siphon overall helps. Local high points will trap gas so the intake and outlet legs should have continuous slopes without intermediate high points. The flow of the liquid moves bubbles thus the intake leg can have a shallow slope as the flow will push the gas bubbles to the crest. Conversely, the outlet leg needs to have a steep slope to allow the bubbles to move against the liquid flow; though other designs call for a shallow slope in the outlet leg as well to allow the bubbles to be carried out of the siphon. At the crest the gas can be trapped in a chamber above the crest. The chamber needs to be occasionally primed again with liquid to remove the gas.

Siphon rain gauge

[edit]A siphon rain gauge is a rain gauge that can record rainfall over an extended period. A siphon is used to automatically empty the gauge. It is often simply called a "siphon gauge" and is not to be confused with a siphon pressure gauge.

Siphon drainage

[edit]A siphon drainage method is being implemented in several expressways as of 2022. Recent studies found that it can reduce groundwater level behind expressway retaining walls, and there was no indication of clogging. This new drainage system is being pioneered as a long-term method to limit leakage hazard in the retaining wall.[31] Siphon drainage is also used in draining unstable slopes, and siphon roof-water drainage systems have been in use since the 1960s.[32][33]

Siphon spillway

[edit]

A siphon spillway in a dam is usually not technically a siphon, as it is generally used to drain elevated water levels.[34] However, a siphon spillway operates as an actual siphon if it raises the flow higher than the surface of the source reservoir, as sometimes is the case when used in irrigation.[35][21] In operation, a siphon spillway is considered to be "pipe flow" or "closed-duct flow".[36] A normal spillway flow is pressurized by the height of the reservoir above the spillway, whereas a siphon flow rate is governed by the difference in height of the inlet and outlet.[citation needed] Some designs make use of an automatic system that uses the flow of water in a spiral vortex to remove the air above to prime the siphon. Such a design includes the volute siphon.[37]

Flush toilet

[edit]Flush toilets often have some siphon effect as the bowl empties.

Some toilets also use the siphon principle to obtain the actual flush from the cistern. The flush is triggered by a lever or handle that operates a simple diaphragm-like piston pump that lifts enough water to the crest of the siphon to start the flow of water which then completely empties the contents of the cistern into the toilet bowl. The advantage of this system was that no water would leak from the cistern excepting when flushed. These were mandatory in the UK until 2011.[38][failed verification]

Early urinals incorporated a siphon in the cistern which would flush automatically on a regular cycle because there was a constant trickle of clean water being fed to the cistern by a slightly open valve.

Devices that are not true siphons

[edit]Siphon coffee

[edit]

While if both ends of a siphon are at atmospheric pressure, liquid flows from high to low, if the bottom end of a siphon is pressurized, liquid can flow from low to high. If pressure is removed from the bottom end, the liquid flow will reverse, illustrating that it is pressure driving the siphon. An everyday illustration of this is the siphon coffee brewer, which works as follows (designs vary; this is a standard design, omitting coffee grounds):

- a glass vessel is filled with water, then corked (so air-tight) with a siphon sticking vertically upwards

- another glass vessel is placed on top, open to the atmosphere – the top vessel is empty, the bottom is filled with water

- the bottom vessel is then heated; as the temperature increases, the vapor pressure of the water increases (it increasingly evaporates); when the water boils the vapor pressure equals atmospheric pressure, and as the temperature increases above boiling the pressure in the bottom vessel then exceeds atmospheric pressure, and pushes the water up the siphon tube into the upper vessel.

- a small amount of still hot water and steam remain in the bottom vessel and are kept heated, with this pressure keeping the water in the upper vessel

- when the heat is removed from the bottom vessel, the vapor pressure decreases, and can no longer support the column of water – gravity (acting on the water) and atmospheric pressure then push the water back into the bottom vessel.

In practice, the top vessel is filled with coffee grounds, and the heat is removed from the bottom vessel when the coffee has finished brewing. What vapor pressure means concretely is that the boiling water converts high-density water (a liquid) into low-density steam (a gas), which thus expands to take up more volume (in other words, the pressure increases). This pressure from the expanding steam then forces the liquid up the siphon; when the steam then condenses down to water the pressure decreases and the liquid flows back down.

Siphon pump

[edit]While a simple siphon cannot output liquid at a level higher than the source reservoir, a more complicated device utilizing an airtight metering chamber at the crest and a system of automatic valves, may discharge liquid on an ongoing basis, at a level higher than the source reservoir, without outside pumping energy being added. It can accomplish this despite what initially appears to be a violation of conservation of energy because it can take advantage of the energy of a large volume of liquid dropping some distance, to raise and discharge a small volume of liquid above the source reservoir. Thus it might be said to "require" a large quantity of falling liquid to power the dispensing of a small quantity. Such a system typically operates in a cyclical or start/stop but ongoing and self-powered manner.[39][40] Ram pumps do not work in this way. These metering pumps are true siphon pumping devices which use siphons as their power source.

Inverted siphon

[edit]

An inverted siphon is not a siphon but a term applied to pipes that must dip below an obstruction to form a U-shaped flow path.

Large inverted siphons are used to convey water being carried in canals or flumes across valleys, for irrigation or gold mining. The Romans used inverted siphons of lead pipes to cross valleys that were too big to construct an aqueduct.[41][42][43]

Inverted siphons are commonly called traps for their function in preventing sewer gases from coming back out of sewers[44] and sometimes making dense objects like rings and electronic components retrievable after falling into a drain.[45][46] Liquid flowing in one end simply forces liquid up and out the other end, but solids like sand will accumulate. This is especially important in sewerage systems or culverts which must be routed under rivers or other deep obstructions where the better term is "depressed sewer".[47][48][failed verification]

Back siphonage

[edit]Back siphonage is a plumbing term applied to the reversal of normal water flow in a plumbing system due to sharply reduced or negative pressure on the water supply side, such as high demand on water supply by fire-fighting;[49] it is not an actual siphon as it is suction.[50] Back siphonage is rare as it depends on submerged inlets at the outlet (home) end and these are uncommon.[51] Back siphonage is not to be confused with backflow; which is the reversed flow of water from the outlet end to the supply end caused by pressure occurring at the outlet end.[51] Also, building codes usually demand a check valve where the water supply enters a building to prevent backflow into the drinking water system.

Anti-siphon valve

[edit]Building codes often contain specific sections on back siphonage and especially for external faucets (See the sample building code quote, below). Backflow prevention devices such as anti-siphon valves[52] are required in such designs. The reason is that external faucets may be attached to hoses which may be immersed in an external body of water, such as a garden pond, swimming pool, aquarium or washing machine. In these situations the unwanted flow is not actually the result of a siphon but suction due to reduced pressure on the water supply side. Should the pressure within the water supply system fall, the external water may be returned by back pressure into the drinking water system through the faucet. Another possible contamination point is the water intake in the toilet tank. An anti-siphon valve is also required here to prevent pressure drops in the water supply line from suctioning water out of the toilet tank (which may contain additives such as "toilet blue"[53]) and contaminating the water system. Anti-siphon valves function as a one-direction check valve.

Anti-siphon valves are also used medically. Hydrocephalus, or excess fluid in the brain, may be treated with a shunt which drains cerebrospinal fluid from the brain. All shunts have a valve to relieve excess pressure in the brain. The shunt may lead into the abdominal cavity such that the shunt outlet is significantly lower than the shunt intake when the patient is standing. Thus a siphon effect may take place and instead of simply relieving excess pressure, the shunt may act as a siphon, completely draining cerebrospinal fluid from the brain. The valve in the shunt may be designed to prevent this siphon action so that negative pressure on the drain of the shunt does not result in excess drainage. Only excess positive pressure from within the brain should result in drainage.[54][55][56]

The anti-siphon valve in medical shunts is preventing excess forward flow of liquid. In plumbing systems, the anti-siphon valve is preventing backflow.

Sample building code regulations regarding "back siphonage" from the Canadian province of Ontario:[57]

- 7.6.2.3.Back Siphonage

- Every potable water system that supplies a fixture or tank that is not subject to pressures above atmospheric shall be protected against back-siphonage by a backflow preventer.

- Where a potable water supply is connected to a boiler, tank, cooling jacket, lawn sprinkler system or other device where a non-potable fluid may be under pressure that is above atmospheric or the water outlet may be submerged in the non-potable fluid, the water supply shall be protected against backflow by a backflow preventer.

- Where a hose bibb is installed outside a building, inside a garage, or where there is an identifiable risk of contamination, the potable water system shall be protected against backflow by a backflow preventer.

Other anti-siphoning devices

[edit]Along with anti-siphon valves, anti-siphoning devices also exist. The two are unrelated in application. Siphoning can be used to remove fuel from tanks. With the cost of fuel increasing, it has been linked in several countries to the rise in fuel theft. Trucks, with their large fuel tanks, are most vulnerable. The anti-siphon device prevents thieves from inserting a tube into the fuel tank.

Siphon barometer

[edit]A siphon barometer is the term sometimes applied to the simplest of mercury barometers. A continuous U-shaped tube of the same diameter throughout is sealed on one end and filled with mercury. When placed into the upright, "U", position, mercury will flow away from the sealed end, forming a partial vacuum, until balanced by atmospheric pressure on the other end. The term "siphon" derives from the belief that air pressure is involved in the operation of a siphon. The difference in height of the fluid between the two arms of the U-shaped tube is the same as the maximum intermediate height of a siphon. When used to measure pressures other than atmospheric pressure, a siphon barometer is sometimes called a siphon gauge; these are not siphons but follow a standard U-shaped design[58] leading to the term. Siphon barometers are still produced as precision instruments.[59] Siphon barometers should not be confused with a siphon rain gauge.,[60]

Siphon bottle

[edit]

A siphon bottle (also called a soda syphon or, archaically, a siphoid[61]) is a pressurized bottle with a vent and a valve. It is not a siphon as pressure within the bottle drives the liquid up and out a tube. A special form was the gasogene.

Siphon cup

[edit]A siphon cup is the (hanging) reservoir of paint attached to a spray gun, it is not a siphon as a vacuum pump extracts the paint.[62] This name is to distinguish it from gravity-fed reservoirs. An archaic use of the term is a cup of oil in which the oil is transported out of the cup via a cotton wick or tube to a surface to be lubricated, this is not a siphon but an example of capillary action.

Heron's siphon

[edit]Heron's siphon is not a siphon as it works as a gravity driven pressure pump,[63][64] at first glance it appears to be a perpetual motion machine but will stop when the air in the priming pump is depleted. In a slightly differently configuration, it is also known as Heron's fountain.[65]

Venturi siphon

[edit]A venturi siphon, also known as an eductor, is not a siphon but a form of vacuum pump using the Venturi effect of fast flowing fluids (e.g. air), to produce low pressures to suction other fluids; a common example is the carburetor. See pressure head. The low pressure at the throat of the venturi is called a siphon when a second fluid is introduced, or an aspirator when the fluid is air, this is an example of the misconception that air pressure is the operating force for siphons.

Siphonic roof drainage

[edit]Despite the name, siphonic roof drainage does not work as a siphon; the technology makes use of gravity induced vacuum pumping[66] to carry water horizontally from multiple roof drains to a single downpipe and to increase flow velocity.[67] Metal baffles at the roof drain inlets reduce the injection of air which increases the efficiency of the system.[68] One benefit to this drainage technique is reduced capital costs in construction compared to traditional roof drainage.[66] Another benefit is the elimination of pipe pitch or gradient required for conventional roof drainage piping. However this system of gravity pumping is mainly suitable for large buildings and is not usually suitable for residential properties.[68]

Self-siphons

[edit]The term self-siphon is used in a number of ways. Liquids that are composed of long polymers can "self-siphon"[69][70] and these liquids do not depend on atmospheric pressure. Self-siphoning polymer liquids work the same as the siphon-chain model where the lower part of the chain pulls the rest of the chain up and over the crest. This phenomenon is also called a tubeless siphon.[71]

"Self-siphon" is also often used in sales literature by siphon manufacturers to describe portable siphons that contain a pump. With the pump, no external suction (e.g. from a person's mouth/lungs) is required to start the siphon and thus the product is described as a "self-siphon".

If the upper reservoir is such that the liquid there can rise above the height of the siphon crest, the rising liquid in the reservoir can "self-prime" the siphon and the whole apparatus be described as a "self-siphon".[72] Once primed, such a siphon will continue to operate until the level of the upper reservoir falls below the intake of the siphon. Such self-priming siphons are useful in some rain gauges and dams.

In nature

[edit]Anatomy

[edit]The term "siphon" is used for a number of structures in human and animal anatomy, either because flowing liquids are involved or because the structure is shaped like a siphon, but in which no actual siphon effect is occurring: see Siphon (disambiguation).

There has been a debate if whether the siphon mechanism plays a role in blood circulation. However, in the 'closed loop' of circulation this was discounted; "In contrast, in 'closed' systems, like the circulation, gravity does not hinder uphill flow nor does it cause downhill flow, because gravity acts equally on the ascending and descending limbs of the circuit", but for "historical reasons", the term is used.[73][74] One hypothesis (in 1989) was that a siphon existed in the circulation of the giraffe.[75] But further research in 2004 found that, "There is no hydrostatic gradient and since the 'fall' of fluid does not assist the ascending arm, there is no siphon. The giraffe's high arterial pressure, which is sufficient to raise the blood 2 m from heart to head with sufficient remaining pressure to perfuse the brain, supports this concept."[74][76] However, a paper written in 2005 urged more research on the hypothesis:

The principle of the siphon is not species specific and should be a fundamental principle of closed circulatory systems. Therefore, the controversy surrounding the role of the siphon principle may best be resolved by a comparative approach. Analyses of blood pressure on a variety of long-necked and long-bodied animals, which take into account phylogenetic relatedness, will be important. In addition experimental studies that combined measurements of arterial and venous blood pressures, with cerebral blood flow, under a variety of gravitational stresses (different head positions), will ultimately resolve this controversy.[77]

Species

[edit]Some species are named after siphons because they resemble siphons in whole or in part. Geosiphons are fungi. There are species of alga belonging to the family Siphonocladaceae in the phylum Chlorophyta[78] which have tube-like structures. Ruellia villosa is a tropical plant in the family Acanthaceae that is also known by the botanical synonym, Siphonacanthus villosus Nees'.[79]

Geology

[edit]In speleology, a siphon or a sump is that part of a cave passage that lies under water and through which cavers have to dive to progress further into the cave system, but it is not an actual siphon.

Rivers

[edit]A river siphon occurs when part of the water flow passes under a submerged object like a rock or tree trunk. The water flowing under the obstruction can be very powerful, and as such can be very dangerous for kayaking, canyoning, and other river-based watersports.

Explanation using Bernoulli's equation

[edit]Bernoulli's equation may be applied to a siphon to derive its ideal flow rate and theoretical maximum height.

- Let the surface of the upper reservoir be the reference elevation.

- Let point A be the start point of siphon, immersed within the higher reservoir and at a depth −d below the surface of the upper reservoir.

- Let point B be the intermediate high point on the siphon tube at height +hB above the surface of the upper reservoir.

- Let point C be the drain point of the siphon at height −hC below the surface of the upper reservoir.

Bernoulli's equation:

- = fluid velocity along the streamline

- = gravitational acceleration downwards

- = elevation in gravity field

- = pressure along the streamline

- = fluid density

Apply Bernoulli's equation to the surface of the upper reservoir. The surface is technically falling as the upper reservoir is being drained. However, for this example we will assume the reservoir to be infinite and the velocity of the surface may be set to zero. Furthermore, the pressure at both the surface and the exit point C is atmospheric pressure. Thus:

| 1 |

Apply Bernoulli's equation to point A at the start of the siphon tube in the upper reservoir where P = PA, v = vA and y = −d

| 2 |

Apply Bernoulli's equation to point B at the intermediate high point of the siphon tube where P = PB, v = vB and y = hB

| 3 |

Apply Bernoulli's equation to point C where the siphon empties. Where v = vC and y = −hC. Furthermore, the pressure at the exit point is atmospheric pressure. Thus:

| 4 |

Velocity

[edit]As the siphon is a single system, the constant in all four equations is the same. Setting equations 1 and 4 equal to each other gives:

Solving for vC:

- Velocity of siphon:

The velocity of the siphon is thus driven solely by the height difference between the surface of the upper reservoir and the drain point. The height of the intermediate high point, hB, does not affect the velocity of the siphon. However, as the siphon is a single system, vB = vC and the intermediate high point does limit the maximum velocity. The drain point cannot be lowered indefinitely to increase the velocity. Equation 3 will limit the velocity to retain a positive pressure at the intermediate high point to prevent cavitation. The maximum velocity may be calculated by combining equations 1 and 3:

Setting PB = 0 and solving for vmax:

- Maximum velocity of siphon:

The depth, −d, of the initial entry point of the siphon in the upper reservoir, does not affect the velocity of the siphon. No limit to the depth of the siphon start point is implied by Equation 2 as pressure PA increases with depth d. Both these facts imply the operator of the siphon may bottom skim or top skim the upper reservoir without impacting the siphon's performance.

This equation for the velocity is the same as that of any object falling height hC. This equation assumes PC is atmospheric pressure. If the end of the siphon is below the surface, the height to the end of the siphon cannot be used; rather the height difference between the reservoirs should be used.

Maximum height

[edit]Although siphons can exceed the barometric height of the liquid in special circumstances, e.g. when the liquid is degassed and the tube is clean and smooth,[80] in general the practical maximum height can be found as follows.

Setting equations 1 and 3 equal to each other gives:

Maximum height of the intermediate high point occurs when it is so high that the pressure at the intermediate high point is zero; in typical scenarios this will cause the liquid to form bubbles and if the bubbles enlarge to fill the pipe then the siphon will "break". Setting PB = 0:

Solving for hB:

- General height of siphon:

This means that the height of the intermediate high point is limited by pressure along the streamline being always greater than zero.

- Maximum height of siphon:

This is the maximum height that a siphon will work. Substituting values will give approximately 10 m (33 feet) for water and, by definition of standard pressure, 0.76 m (760 mm; 30 in) for mercury. The ratio of heights (about 13.6) equals the ratio of densities of water and mercury (at a given temperature). As long as this condition is satisfied (pressure greater than zero), the flow at the output of the siphon is still only governed by the height difference between the source surface and the outlet. Volume of fluid in the apparatus is not relevant as long as the pressure head remains above zero in every section. Because pressure drops when velocity is increased, a static siphon (or manometer) can have a slightly higher height than a flowing siphon.

Operation in a vacuum

[edit]Experiments have shown that siphons can operate in a vacuum, via cohesion and tensile strength between molecules, provided that the liquids are pure and degassed and surfaces are very clean.[4][81][6][7][82][83][84][26]

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) entry on siphon, published in 1911, states that a siphon works by atmospheric pressure. Stephen Hughes of Queensland University of Technology criticized this in a 2010 article[21] which was widely reported in the media.[85][86][87][88] The OED editors stated, "there is continuing debate among scientists as to which view is correct. ... We would expect to reflect this debate in the fully updated entry for siphon, due to be published later this year."[89] Hughes continued to defend his view of the siphon in a late September post at the Oxford blog.[90] The 2015 definition by the OED is:

A tube used to convey liquid upwards from a reservoir and then down to a lower level of its own accord. Once the liquid has been forced into the tube, typically by suction or immersion, flow continues unaided.

The Encyclopædia Britannica currently describes a siphon as:

Siphon, also spelled syphon, instrument, usually in the form of a tube bent to form two legs of unequal length, for conveying liquid over the edge of a vessel and delivering it at a lower level. Siphons may be of any size. The action depends upon the influence of gravity (not, as sometimes thought, on the difference in atmospheric pressure; a siphon will work in a vacuum) and upon the cohesive forces that prevent the columns of liquid in the legs of the siphon from breaking under their own weight. At sea level, water can be lifted a little more than 10 metres (33 feet) by a siphon. In civil engineering, pipelines called inverted siphons are used to carry sewage or stormwater under streams, highway cuts, or other depressions in the ground. In an inverted siphon the liquid completely fills the pipe and flows under pressure, as opposed to the open-channel gravity flow that occurs in most sanitary or storm sewers.[91]

Standards in engineering or industry

[edit]The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) publishes the following Tri-Harmonized Standard:

- ASSE 1002/ASME A112.1002/CSA B125.12 on Performance Requirements for Anti-Siphon Fill Valves (Ballcocks) for Gravity Water Closet Flush Tanks

See also

[edit]- 1992 Guadalajara explosions for details of an accident where a plumbing method (trap, also known as an inverted siphon) was partially responsible for gas explosions.

- Communicating vessels

- Concentric siphon

- Gravity feed

- Jiggle syphon

- Marot jar

- Pythagorean cup

- Water level (device)

References

[edit]- Calvert, James B. (11 May 2000). "Hydrostatics". Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ a b Ramette, Joshua J.; Ramette, Richard W. (July 2011). "Siphonic concepts examined: a carbon dioxide gas siphon and siphons in vacuum". Physics Education. 46 (4): 412–416. Bibcode:2011PhyEd..46..412R. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/46/4/006. S2CID 120194913.

- ^ a b c d e f g Richert, Alex; Binder, P.-M. (February 2011). "Siphons, Revisited" (PDF). The Physics Teacher. 49 (2): 78. Bibcode:2011PhTea..49...78R. doi:10.1119/1.3543576. Press release for this article: "Yanking the chain on siphon claims" (Press release). University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo. 19 January 2011.

- ^ a b McGuire, Adam (2 August 2012). "On the Physics of Siphons" (PDF). National Science Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-05. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- ^ a b c d Minor, Ralph Smith (1914). "Would a Siphon Flow in a Vacuum! Experimental Answers" (PDF). School Science and Mathematics. 14 (2): 152–155. doi:10.1111/j.1949-8594.1914.tb16014.x.

- ^ a b Boatwright, A.; Hughes, S.; Barry, J. (2015-12-02). "The height limit of a siphon". Scientific Reports. 5 (1) 16790. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516790B. doi:10.1038/srep16790. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4667279. PMID 26628323.

- ^ a b Michels, John (1902). Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. p. 152. Retrieved 15 April 2018 – via Internet Archive.

duane siphon 1902.

- ^ a b c d e f Nokes, M. C. (1948). "Vacuum siphons" (PDF). School Science Review. 29: 233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-29.

- ^ a b Water Flowing Up 24 meters Not Magic, Just Science! Gravity of Life (Part3) on YouTube

- ^ Amazing Slow Motion Bead Chain Experiment | Slow Mo | Earth Unplugged on YouTube.

- ^ Pouring and Siphoning a Gas on YouTube

- ^ Schieber, Frank (28 March 2011). "Winemaking in Ancient Egypt: 2000 Years Before the Birth of Christ" (PDF). Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ a b Usher, Abbott Payson (15 April 2018). A History of Mechanical Inventions. Courier Corporation. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-4862-5593-4.

- ^ Dora P. Crouch (1993). "Water management in ancient Greek cities". Oxford University Press US. p. 119. ISBN 0-19-507280-4.

- ^ "THE PNEUMATICS OF HERO OF ALEXANDRIA". himedo.net. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Banu Musa (1979). The book of ingenious devices (Kitāb al-ḥiyal). Translated by Donald Routledge Hill. Springer. p. 21. ISBN 978-90-277-0833-5.

- ^ "History Of Science And Technology In Islam". www.history-science-technology.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ a b Calvert (2000). "Maximum height to which water can be raised by a suction pump".

- ^ a b c d e "QUT physicist corrects Oxford English Dictionary (w/ Video)". phys.org.

- ^ a b "The Pulley Analogy Does Not Work For Every Siphon".

- ^ Smith, Andrew M. (1991). "Negative Pressure Generated by Octopus Suckers: A Study of the Tensile Strength of Water in Nature". Journal of Experimental Biology. 157 (1): 257–271. Bibcode:1991JExpB.157..257S. doi:10.1242/jeb.157.1.257.

- ^ a b c d Hughes, Stephen W. (March 2010). "A practical example of a siphon at work". Physics Education. 45 (2). IOP Publishing: 162–166. Bibcode:2010PhyEd..45..162H. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/45/2/006. ISSN 0031-9120. S2CID 122367587.

- ^ Boatwright, A.; Hughes, S.; Barry, J. (2 December 2015). "The height limit of a siphon". Nature. 5 16790. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516790B. doi:10.1038/srep16790. PMC 4667279. PMID 26628323.

- ^ Calvert (2000). "The siphon".

- ^ Potter, A.; Barnes, F.H. (1 September 1971). "The siphon". Physics Education. 6 (5): 362–366. Bibcode:1971PhyEd...6..362P. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/6/5/005.

- ^ Hughes, Stephen W. (May 2011). "The secret siphon" (PDF). Physics Education. 46 (3): 298–302. Bibcode:2011PhyEd..46..298H. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/46/3/007. S2CID 122754077.

- ^ a b Boatwright, Adrian L. (2011). "Can a Siphon Work In Vacuo?". Journal of Chemical Education. 88 (11): 1547–1550. Bibcode:2011JChEd..88.1547B. doi:10.1021/ed2001818.

- ^ Dooley, John W (2011). "Siphoning—a weighty topic". Physics Today. 64 (8): 10. Bibcode:2011PhT....64h..10D. doi:10.1063/PT.3.1199.

- ^ Hughes, Stephen; Gurung, Som (April 22, 2014). "Exploring the boundary between a siphon and barometer in a hypobaric chamber". Scientific Reports. 4 (1): 4741. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4.4741H. doi:10.1038/srep04741. PMC 3994459. PMID 24751967.

- ^ "Material Safety Data Sheet for MidGrade Unleaded Gasoline" (PDF). 28 November 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-28.

- ^ "Siphons for Geosiphon Treatment Systems". sti.srs.gov. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ Yan, Xin; Zhan, Wei; Hu, Zhi; Wang, Lei; Yu, Yiqiang; Xiao, Danqiang (2022-12-01). "Experimental study on the anti-clogging ability of siphon drainage and engineering application". Soils and Foundations. 62 (6) 101221. Bibcode:2022SoFou..6201221Y. doi:10.1016/j.sandf.2022.101221. ISSN 0038-0806. S2CID 252793321.

- ^ Admin, WJ Group (7 July 2015). "Siphon Draining". WJ Group. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ^ "Siphon roof water drainage systems". www.ntotank.com. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ^ Smith, W. B. (29 July 2005). "Siphon spillway – automatically starting siphons". www.vl-irrigation.org. Archived from the original on 2015-06-02. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Lake Bonney refill underway". www.abc.net.au. 26 November 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Hm16036e.vp" (PDF). Retrieved 2021-11-19.

- ^ Rao, Govinda N. S. (2008). "Design of Volute Siphon" (PDF). Journal of the Indian Institute of Science. 88 (3): 915–930. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-20. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

- ^ "Siphon vs valve flush - Information Hub". Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Improvement in siphon-pumps". Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Siphon pump having a metering chamber". Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Aqua Clopedia, a picture dictionary of Roman aqueducts: Siphons". www.romanaqueducts.info. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Inverted syphon of the roman aqueducts - Naked Science Forum". www.thenakedscientists.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Siphons in Roman (and Hellenistic) aqueducts". www.romanaqueducts.info. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Carter, Tim (26 January 2017). "Sewer Odors in Bathroom - Ask the Builder". Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Drain Traps Are Protection Against Sewer Gas". Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "How To Retrieve An Item Dropped Down A Sink Drain - A Concord Carpenter". www.aconcordcarpenter.com. 26 December 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Inverted Siphon. Depressed Sewer. Design Calculations". www.lmnoeng.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Arizona Administrative Code, Title 18. Environmental Quality, Chapter 9. Department Of Environmental Quality, Article 3. Aquifer Protection Permits, Part E. Type 4 General Permits" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-13. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ Poo, Wing. "What is back-siphonage and its causes? - Water FAQ Backflow Prevention - Water / Wastewater - Operations Centre". www.grimsby.ca. Archived from the original on 2018-04-15. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Drinking Water - Backflow and Backsiphonage". water.ky.gov. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Information about Public Water Systems" (PDF). US EPA. 21 September 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Toiletology ... Anti-siphon needs an explanation". www.toiletology.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ "Toilet Blue Loo - Sweet Lu". www.cleaningshop.com.au. CLEANERS SUPERMARKET® Pty, Ltd. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Tokoro, Kazuhiko; Chiba, Yasuhiro; Abe, Hiroyuki; Tanaka, Nobumasa; Yamataki, Akira; Kanno, Hiroshi (1994). "Importance of anti-siphon devices in the treatment of pediatric hydrocephalus". Child's Nervous System. 10 (4): 236–8. doi:10.1007/BF00301160. PMID 7923233. S2CID 25326092.

- ^ "Hydrocephalus and Shunts in the Person with Spina Bifida" (Press release). Spina Bifida Association of America. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Zemack, Göran; Romner, Bertil (1999). "Seven-year clinical experience with the Codman Hakim programmable valve: a retrospective study of 583 patients". Neurosurgical Focus. 7 (4): 941–8. doi:10.3171/foc.1999.7.4.11.

- ^ "Part 4: Structural Design". Archived from the original on May 28, 2004.

- ^ "Pressure gauge syphon - 910.15 - WIKA Australia". www.wika.com.au. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Siphon barometer". Archived from the original on 2015-01-05. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ "THE SIPHONING RAIN GAUGE". www.axinum.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ "Gravity or Siphon? - Don's Airbrush Tips". sites.google.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Greenslade, Thomas B. Jr. "Hero's Fountain". physics.kenyon.edu. Archived from the original on 21 January 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Agbanlog, Rogelio Cabang; Chen, Guangming (2014). "Mini hydro-electric power plant with re-circulated water power source". In Guan, Y.; Liao, H. (eds.). Proceedings of the 2014 Industrial and Systems Engineering Research Conference. Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers. pp. 2145ff.

- ^ Kezerashvili, R. Ya.; Sapozhnikov, A. (2003). "Magic Fountain". arXiv:physics/0310039v1.

- ^ a b "Siphonic Solutions design and contract" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-27. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ "Syphonic Drainage by Fullflow: Syphonic Explained". Archived from the original on 2015-01-05. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ a b "Siphonic roof drainage comes out on top". Archived from the original on 2014-09-10. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ "Physics Demonstrations - Light". sprott.physics.wisc.edu. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ School of Chemistry. Chem.soton.ac.uk. Retrieved on 11 November 2010.

- ^ Tubeless Siphon and Die Swell Demonstration, Christopher W. MacMinn & Gareth H. McKinley, 26 September 2004

- ^ "Siphon". Grow.arizona.edu. Archived from the original on 2004-06-02. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Gisolf, Janneke (25 February 2005). "Effects of gravity on the circulation" (PDF). Postural changes in humans: effects of gravity on the circulation (PDF) (Thesis). University of Amsterdam. pp. 7–12. hdl:11245/1.239323. ISBN 978-90-901905-70. OCLC 6893398534.

- ^ a b Gisolf, J.; Gisolf, A.; van Lieshout, J. J.; Karemaker, J. M. (2005). "The siphon controversy: an integration of concepts and the brain as baffle". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 289 (2). American Physiological Society: R627 – R629. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00709.2004. ISSN 0363-6119. PMID 16014453.

- ^ Hicks, JW; Badeer, HS (February 1989). "Siphon mechanism in collapsible tubes: application to circulation of the giraffe head". Am. J. Physiol. 256 (2 Pt 2): R567–71. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.2.R567. PMID 2916707.

- ^ Seymour, RS; Johansen, K (1987). "Blood flow uphill and downhill: does a siphon facilitate circulation above the heart?". Comp Biochem Physiol A. 88 (2): 167–70. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(87)90465-8. PMID 2890463.

- ^ Hicks, James W.; Munis, James R. (2005). "The siphon controversy counterpoint: the brain need not be "baffling"". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 289 (2). American Physiological Society: R629 – R632. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00810.2004. ISSN 0363-6119. PMID 16014454.

- ^ "Flora da Bahia: Siphonocladaceae". Retrieved 2021-11-19.

- ^ "Flora brasiliensis, CRIA". florabrasiliensis.cria.org.br. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Water Flowing Up 24 meters Not Magic, Just Science! Gravity of Life (Part3)". YouTube. 24 August 2007. Retrieved 30 Nov 2014.

- ^ "Siphon in a Vacuum - Periodic Table of Videos". 10 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "Siphon Concepts". Archived from the original on 2012-10-09.

- ^ Ganci, S; Yegorenkov, V (2008). "Historical and pedagogical aspects of a humble instrument". European Journal of Physics. 29 (3): 421–430. Bibcode:2008EJPh...29..421G. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/29/3/003. S2CID 119563871.

- ^ Nokes M. C. (1948). "Vacuum siphons". Am. J. Phys. 16: 254.

- ^ QUT physicist corrects Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ "AOL News, For 99 Years, Oxford English Dictionary Got It Wrong". Archived from the original on 2010-05-14.

- ^ Calligeros, Marissa (10 May 2010). "Dictionary mistake goes unnoticed for 99 years". Brisbane Times.

- ^ Malkin, Bonnie (11 May 2010). "Physicist spots 99-year-old mistake in Oxford English Dictionary". The Daily Telegraph (London).

- ^ "On The Definition of "Siphon"". OUPblog. Oxford University Press. 21 May 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "On The Definition of "Siphon" - OUPblog". 21 May 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Siphon - instrument". Retrieved 15 April 2018.

External links

[edit]Siphon

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Operation

A siphon is a tube or conduit designed to transfer liquid from a reservoir at a higher elevation to one at a lower elevation, passing over an intermediate rise, by relying on gravity and atmospheric pressure rather than mechanical pumping. This passive mechanism exploits the natural tendency of fluids to flow downward while enabling the liquid to ascend temporarily against gravity on the inlet side. Siphons are widely used in simple fluid transfer scenarios due to their reliability and lack of moving parts. The basic operation of a siphon begins with priming, where the tube is completely filled with the liquid to eliminate air pockets and form a continuous liquid column. Once primed, the setup creates a pressure differential: the atmospheric pressure acting on the exposed surface of the higher reservoir pushes the liquid up the inlet leg of the tube, while the weight of the liquid column in the descending outlet leg pulls it downward, sustaining flow as long as the outlet remains below the inlet liquid level. This process continues until the source reservoir is depleted or the siphon is interrupted, such as by introducing air into the tube. Siphons have been employed since early times as straightforward devices for gravitational water transfer.[11] A typical basic siphon features an inverted U-shaped or J-shaped tube configuration, with the inlet submerged in the source liquid, the summit positioned above the liquid surface to form the rise, and the outlet extending to a lower point for discharge. Flexible tubing, often made from rubber or plastic for ease of handling and priming, or rigid pipes like PVC for more permanent installations, are common materials in these simple setups, chosen for their compatibility with the liquid and resistance to corrosion.[12]Components and Setup

A siphon is constructed using a simple tube arranged in an inverted U-shape, comprising key components that facilitate liquid transfer. The inlet is the submerged end placed in the source liquid reservoir, allowing liquid to enter the system. The tube itself, preferably of uniform diameter to minimize flow restrictions and ensure even velocity, connects the inlet to the outlet and includes the summit as its highest point, which must rise above the source liquid level. The outlet is the discharge end positioned to release liquid into a lower receptacle.[13] Proper setup requires positioning the outlet below the surface level of the liquid in the source container to enable gravity-driven flow once initiated. The overall tube length is constrained by atmospheric pressure, which supports the liquid column in the summit; for water at standard conditions, this limits the maximum effective height to approximately 10 meters to prevent the column from breaking due to vapor pressure. Assembly involves securing the tube to avoid kinks or leaks, often using flexible materials like rubber or plastic tubing for ease of handling in practical applications.[13] To initiate flow, the tube must be primed by filling it completely with liquid to expel air and establish a continuous column. Common priming techniques include applying suction at the outlet end via mouth or a pump until liquid emerges, fully submerging the tube in the source liquid and then lifting the outlet while pinching to retain the fill, or pouring liquid directly into the tube through a temporary opening before sealing and placing the ends. In laboratory settings, such as fluid dynamics demonstrations, priming can involve filling the tube under a tap and using clamps to control the start of flow.[14][13] Air locks, where trapped air pockets disrupt the liquid column and halt flow, represent a frequent setup challenge, particularly if the tube is not fully primed or if connections are loose. These issues are mitigated by selecting non-porous, airtight materials like smooth plastic or glass tubing that prevent air infiltration, ensuring all joints are tightly sealed with clamps or fittings, and verifying complete filling during priming. Avoiding materials with microscopic pores, such as certain fabrics or degraded rubber, further reduces the risk of gradual air entry.[13] An ideal configuration features a smooth, uninterrupted inverted U-tube with the summit elevated just above the source level and the outlet sufficiently lower to maintain momentum, as depicted in standard engineering diagrams showing symmetric legs for balanced pressure. In contrast, suboptimal setups—such as those with sharp bends at the summit, uneven leg lengths, or the outlet not low enough—can cause intermittent flow or failure to prime, often illustrated in troubleshooting schematics where air bubbles are shown accumulating at high points.[13]Historical Development

Ancient and Classical Uses

The earliest documented uses of siphons date back to ancient Egypt around 1500 BCE, where reliefs depict them being employed to extract liquids from large storage jars, particularly in winemaking to separate wine from sediment without contamination.[15] This technique was crucial in viticulture, as it preserved the quality and purity of the wine by avoiding the mixing of dregs, reflecting the cultural importance of wine in Egyptian society for religious rituals, offerings, and elite consumption.[16] In Mesopotamia, siphons were similarly applied around 2000 BCE for rudimentary irrigation, siphoning water from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers into fields via small canals to support agriculture in the arid Fertile Crescent.[17] During the classical Greek period, the engineer Hero of Alexandria advanced siphon applications in the 1st century CE, as detailed in his treatise Pneumatica. Hero described various siphon designs, including the bent siphon for basic fluid transfer, the concentric siphon for controlled flow, the uniform discharge siphon to maintain consistent rates, and adjustable siphons capable of varying output quantities.[18] These innovations powered elaborate fountains and automata, such as self-operating devices that used siphon networks to create intermittent water displays or mechanical figures, demonstrating pneumatics and hydrostatics for entertainment and engineering demonstration.[19] The Romans adapted and scaled siphon technology for large-scale water management in aqueducts and drainage systems during the 1st century CE and beyond. Inverted siphons—U-shaped pipes that dipped below ground to cross valleys under pressure—were integrated into aqueduct networks to maintain flow where elevated channels were impractical, with lead or terracotta pipes capable of withstanding hydraulic forces.[5] A prominent example is the Gier aqueduct serving Lyon, France, which featured multiple parallel siphons, including the Saint-Genis siphon spanning 2.6 kilometers with a 123-meter drop, highlighting Roman engineering prowess in urban water supply and flood control.[20] In the medieval period, siphon technology was further developed in Islamic engineering. The Banu Musa brothers in 9th-century Baghdad described self-filling and trick siphons in their Book of Ingenious Devices, applying principles of pneumatics for automated water systems and fountains, influencing later European hydraulics.[21]Evolution in Modern Engineering

During the 18th and 19th centuries, siphons saw significant integration into emerging industrial hydraulic systems, particularly for water management in mining operations. Inverted siphons, which allow fluid to flow under pressure across valleys or obstacles, were employed to transport water for hydraulic mining techniques, such as the Virginia and Gold Hill Water Company’s system at Nevada's Comstock Lode in the 1870s, where heavy-gauge pipes withstood high pressures to deliver water without pumps.[22] In Australian gold mining contexts, siphons were routinely used as piping to convey water over barriers, enabling efficient ore processing and reflecting the era's innovative application of fluid dynamics in resource extraction.[23] These advancements complemented steam-powered systems, including beam engines like the Cornish type, which were primarily used for pumping water from deep mine shafts in operations such as those in Cornwall's tin mines.[24] In the 20th century, siphon technology underwent standardization, particularly in large-scale infrastructure like dam spillways designed to manage floodwaters. Post-1900, engineers like John S. Eastwood pioneered siphon spillways in American dams, such as the experimental Big Meadows Dam in California around 1907–1913, where the design automatically initiated flow when reservoir levels rose, providing a controlled discharge mechanism without mechanical gates.[25] This innovation spread to major projects, including siphon spillways at the Bear Valley Dam in California (completed 1913), which featured self-sustaining flow after priming and air vents for regulation, influencing global dam engineering practices.[26] By mid-century, siphon spillways were codified in plumbing and hydraulic standards, such as those from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, ensuring reliable integration into waterworks and irrigation systems for flood control and water level regulation.[27] Key milestones in siphon evolution included the development of self-priming variants in the early 1900s, driven by automotive needs. Vacuum tank fuel systems, introduced in the 1920s for vehicles like the Plymouth, used engine-driven vacuum to prime siphon action, drawing fuel from the tank to a reservoir above the carburetor and enabling reliable delivery without gravity feed limitations in higher-mounted tanks.[28] This addressed priming challenges in internal combustion engines, marking a shift toward automated fluid transfer in transportation.[28] The late 20th century brought a transition to synthetic materials, enhancing siphon durability and cost-effectiveness in plumbing and industrial applications. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes, first commercially produced for water conveyance in 1935, gained widespread adoption in siphon systems by the 1950s and 1960s, replacing metal conduits due to their corrosion resistance and lightweight properties, as standardized in residential and municipal plumbing codes.[29] By the 1980s, PVC's formulation improvements allowed for seamless integration into siphon traps and drainage lines, reducing maintenance needs and enabling scalable use in modern infrastructure like sewer laterals and irrigation.[30]Theoretical Foundations

Explanation via Bernoulli's Equation

Bernoulli's principle provides the theoretical foundation for understanding siphon flow through the conservation of mechanical energy along a fluid streamline. The principle is mathematically expressed by Bernoulli's equation, which states that for an inviscid, incompressible fluid under steady flow conditions, the total energy per unit volume remains constant: Here, represents the static pressure, the fluid density, the acceleration due to gravity, the elevation head above a reference datum, and the flow velocity.[31][3] In a typical siphon setup, where a tube connects a fluid reservoir at higher elevation to an outlet at lower elevation and arches over a barrier, Bernoulli's equation is applied along the streamline from the reservoir surface (point 1) through the summit of the arch (point 3) to the outlet (point 2). At point 1, the pressure is atmospheric (), velocity is negligible (), and elevation is . At point 2, the pressure is also atmospheric () with elevation and velocity . Applying the equation between points 1 and 2 yields: Simplifying, the height difference drives the flow, converting potential energy into kinetic energy at the outlet. This establishes the overall energy balance that sustains the siphon.[32][33] To explain the flow through the uphill section to the summit (point 3, where ), apply Bernoulli's equation between points 1 and 3, assuming constant tube cross-section so : Rearranging gives the pressure at the summit: Since , the term is negative, causing to drop below atmospheric pressure. This reduced pressure at the summit facilitates the upward flow against gravity in the initial leg of the siphon, as the pressure gradient provides the force to elevate the fluid. The subsequent downhill section then accelerates the fluid, recovering momentum from the gravitational potential and maintaining the overall flow driven by the net elevation drop from inlet to outlet.[32][33][34] This derivation relies on key assumptions: the fluid is incompressible (constant ), the flow is steady (no time variation), and inviscid (neglecting viscous effects and friction losses along the tube walls). These idealizations simplify the energy conservation to the form above, focusing on pressure, gravitational potential, and kinetic contributions. In practice, friction introduces head losses, reducing actual flow rates compared to the ideal prediction, though the core mechanism remains valid for low-viscosity fluids like water.[31][34]Flow Velocity and Maximum Height