Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Transport network analysis

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on | ||||

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

A transport network, or transportation network, is a network or graph in geographic space, describing an infrastructure that permits and constrains movement or flow.[1] Examples include but are not limited to road networks, railways, air routes, pipelines, aqueducts, and power lines. The digital representation of these networks, and the methods for their analysis, is a core part of spatial analysis, geographic information systems, public utilities, and transport engineering. Network analysis is an application of the theories and algorithms of graph theory and is a form of proximity analysis.

History

[edit]The applicability of graph theory to geographic phenomena was recognized at an early date. Many of the early problems and theories undertaken by graph theorists were inspired by geographic situations, such as the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem, which was one of the original foundations of graph theory when it was solved by Leonhard Euler in 1736.[2]

In the 1970s, the connection was reestablished by the early developers of geographic information systems, who employed it in the topological data structures of polygons (which is not of relevance here), and the analysis of transport networks. Early works, such as Tinkler (1977), focused mainly on simple schematic networks, likely due to the lack of significant volumes of linear data and the computational complexity of many of the algorithms.[3] The full implementation of network analysis algorithms in GIS software did not appear until the 1990s,[4][5] but rather advanced tools are generally available today.

Network data

[edit]Network analysis requires detailed data representing the elements of the network and its properties.[6] The core of a network dataset is a vector layer of polylines representing the paths of travel, either precise geographic routes or schematic diagrams, known as edges. In addition, information is needed on the network topology, representing the connections between the lines, thus enabling the transport from one line to another to be modeled. Typically, these connection points, or nodes, are included as an additional dataset.[7]

Both the edges and nodes are attributed with properties related to the movement or flow:

- Capacity, measurements of any limitation on the volume of flow allowed, such as the number of lanes in a road, telecommunications bandwidth, or pipe diameter.

- Impedance, measurements of any resistance to flow or to the speed of flow, such as a speed limit or a forbidden turn direction at a street intersection

- Cost accumulated through individual travel along the edge or through the node, commonly elapsed time, in keeping with the principle of friction of distance. For example, a node in a street network may require a different amount of time to make a particular left turn or right turn. Such costs can vary over time, such as the pattern of travel time along an urban street depending on diurnal cycles of traffic volume.

- Flow volume, measurements of the actual movement taking place. This may be specific time-encoded measurements collected using sensor networks such as traffic counters, or general trends over a period of time, such as Annual average daily traffic (AADT).

Analysis methods

[edit]A wide range of methods, algorithms, and techniques have been developed for solving problems and tasks relating to network flow. Some of these are common to all types of transport networks, while others are specific to particular application domains.[8] Many of these algorithms are implemented in commercial and open-source GIS software, such as GRASS GIS and the Network Analyst extension to Esri ArcGIS.

Optimal routing

[edit]One of the simplest and most common tasks in a network is to find the optimal route connecting two points along the network, with optimal defined as minimizing some form of cost, such as distance, energy expenditure, or time.[9] A common example is finding directions in a street network, a feature of almost any web street mapping application such as Google Maps. The most popular method of solving this task, implemented in most GIS and mapping software, is Dijkstra's algorithm.[10]

In addition to the basic point-to-point routing, composite routing problems are also common. The Traveling salesman problem asks for the optimal (least distance/cost) ordering and route to reach a number of destinations; it is an NP-hard problem, but somewhat easier to solve in network space than unconstrained space due to the smaller solution set.[11] The Vehicle routing problem is a generalization of this, allowing for multiple simultaneous routes to reach the destinations. The Route inspection or "Chinese Postman" problem asks for the optimal (least distance/cost) path that traverses every edge; a common application is the routing of garbage trucks. This turns out to be a much simpler problem to solve, with polynomial time algorithms.

Location analysis

[edit]This class of problems aims to find the optimal location for one or more facilities along the network, with optimal defined as minimizing the aggregate or mean travel cost to (or from) another set of points in the network. A common example is determining the location of a warehouse to minimize shipping costs to a set of retail outlets, or the location of a retail outlet to minimize the travel time from the residences of its potential customers. In unconstrained (cartesian coordinate) space, this is an NP-hard problem requiring heuristic solutions such as Lloyd's algorithm, but in a network space it can be solved deterministically.[12]

Particular applications often add further constraints to the problem, such as the location of pre-existing or competing facilities, facility capacities, or maximum cost.

Service areas

[edit]A network service area is analogous to a buffer in unconstrained space, a depiction of the area that can be reached from a point (typically a service facility) in less than a specified distance or other accumulated cost.[13] For example, the preferred service area for a fire station would be the set of street segments it can reach in a small amount of time. When there are multiple facilities, each edge would be assigned to the nearest facility, producing a result analogous to a Voronoi diagram.[14]

Fault analysis

[edit]A common application in public utility networks is the identification of possible locations of faults or breaks in the network (which is often buried or otherwise difficult to directly observe), deduced from reports that can be easily located, such as customer complaints.

Transport engineering

[edit]Traffic has been studied extensively using statistical physics methods.[15][16][17]

Vertical analysis

[edit]To ensure the railway system is as efficient as possible a complexity/vertical analysis should also be undertaken. This analysis will aid in the analysis of future and existing systems which is crucial in ensuring the sustainability of a system (Bednar, 2022, pp. 75–76). Vertical analysis will consist of knowing the operating activities (day to day operations) of the system, problem prevention, control activities, development of activities and coordination of activities.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Barthelemy, Marc (2010). "Spatial Networks". Physics Reports. 499 (1–3): 1–101. arXiv:1010.0302. Bibcode:2011PhR...499....1B. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2010.11.002. S2CID 4627021.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1736). "Solutio problematis ad geometriam situs pertinentis". Comment. Acad. Sci. U. Petrop 8, 128–40.

- ^ Tinkler, K.J. (1977). "An Introduction to Graph Theoretical Methods in Geography" (PDF). CATMOG (14).

- ^ Ahuja R K, Magnanti T L, Orlin J B (1993) Network flows: Theory, algorithms and applications. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA

- ^ Daskin M S (1995) Network and discrete location — models, algorithms and applications. Wiley, NJ, USA

- ^ "What is a network dataset?". ArcGIS Pro Documentation. Esri.

- ^ "Network elements". ArcGIS Pro Documentation. Esri. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ deSmith, Michael J.; Goodchild, Michael F.; Longley, Paul A. (2021). "7.2.1 Overview - network and locational analysis". Geospatial Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, Techniques, and Software Tools (6th revised ed.).

- ^ Worboys, Michael; Duckham, Matt (2004). "5.7 Network Representation and Algorithms". GIS: A Computing Perspective (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 211–218.

- ^ Dijkstra, E. W. (1959). "A note on two problems in connexion with graphs" (PDF). Numerische Mathematik. 1: 269–271. doi:10.1007/BF01386390. S2CID 123284777.

- ^ "v.net.salesman command". GRASS GIS manual. OSGEO. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ deSmith, Michael J.; Goodchild, Michael F.; Longley, Paul A. (2021). "7.4.2 Larger p-median and p-center problems". Geospatial Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, Techniques, and Software Tools (6th revised ed.).

- ^ deSmith, Michael J.; Goodchild, Michael F.; Longley, Paul A. (2021). "7.4.3 Service areas". Geospatial Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, Techniques, and Software Tools (6th revised ed.).

- ^ "v.net.alloc command". GRASS GIS documentation. OSGEO. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Helbing, D (2001). "Traffic and related self-driven many-particle systems". Reviews of Modern Physics. 73 (4): 1067–1141. arXiv:cond-mat/0012229. Bibcode:2001RvMP...73.1067H. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.73.1067. S2CID 119330488.

- ^ S., Kerner, Boris (2004). The Physics of Traffic : Empirical Freeway Pattern Features, Engineering Applications, and Theory. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 9783540409861. OCLC 840291446.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wolf, D E; Schreckenberg, M; Bachem, A (June 1996). Traffic and Granular Flow. WORLD SCIENTIFIC. pp. 1–394. doi:10.1142/9789814531276. ISBN 9789810226350.

- ^ Bednar, 2022, pp. 75–76

Transport network analysis

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

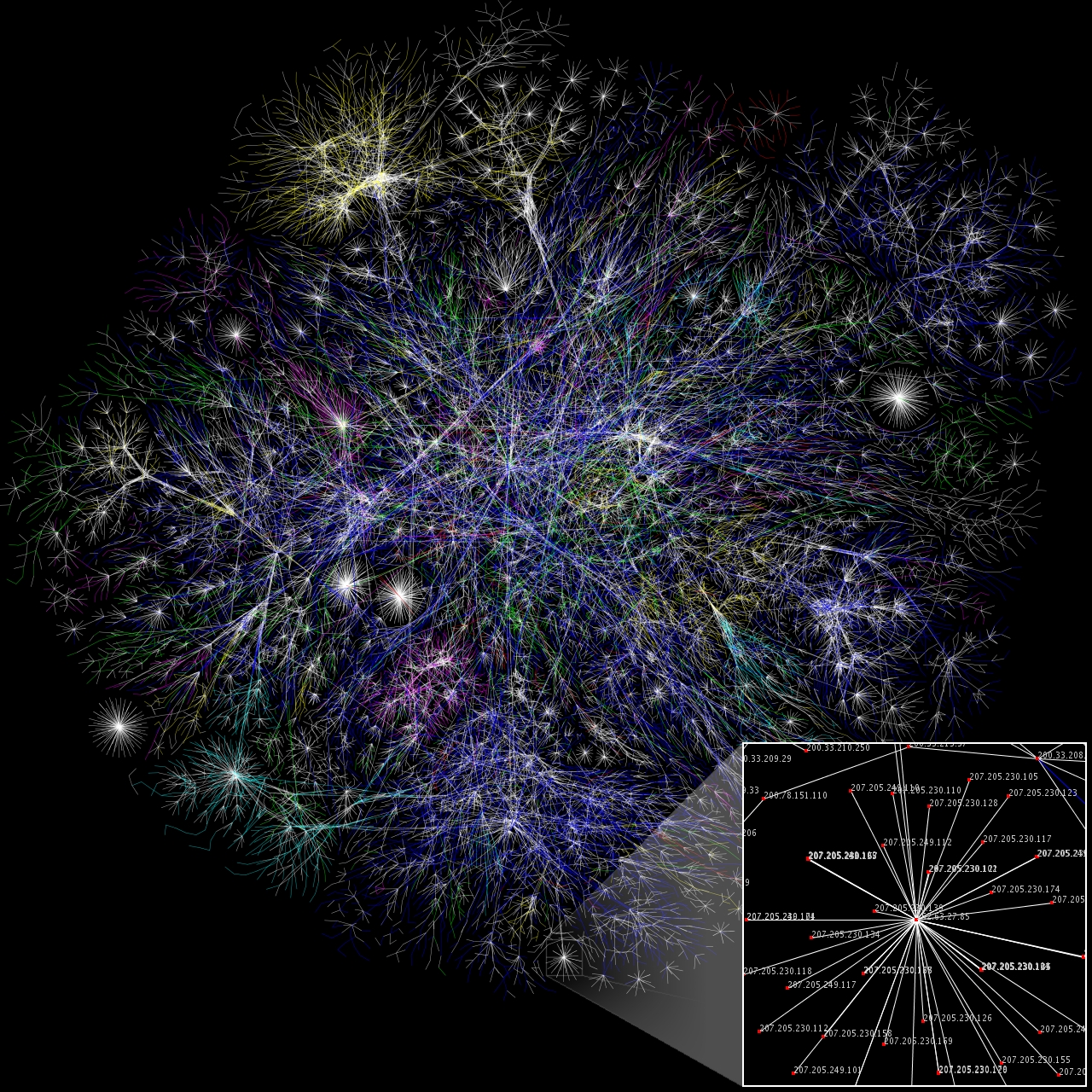

Transport network analysis is the application of mathematical and computational methods to model, evaluate, and optimize interconnected transportation systems, such as roads, rails, and airways, represented as networks of nodes and links.[1] This field examines the spatial and temporal dynamics of movement for people and goods, focusing on how infrastructure configurations influence overall system performance.[4] It relies on graph theory as the foundational modeling tool for abstracting these systems into analyzable structures.[1] The scope of transport network analysis encompasses urban mobility, logistics, public transit, and freight transportation, emphasizing systemic interactions among components rather than isolated elements.[3] Unlike studies of individual routes or vehicles, it addresses how networks integrate diverse modes—like automobiles, buses, trains, and shipping corridors—to handle varying demands across regions.[5] This holistic approach is essential for understanding trade-offs in infrastructure design and policy implementation. Key objectives include improving connectivity to enhance access and economic opportunities, reducing congestion through efficient flow management, enhancing safety by minimizing accident risks, and supporting sustainable planning to balance environmental impacts with operational needs.[3] These goals guide the evaluation of network resilience and adaptability to disruptions, such as traffic peaks or natural events.[1] Basic terminology in the field includes nodes, which represent intersections, junctions, origins, or destinations; links, denoting routes or edges connecting nodes; flow, the rate of vehicles or passengers traversing a link; capacity, the maximum sustainable flow on a link; and demand, the volume of trips required between origin-destination pairs.[5] These concepts form the building blocks for quantitative assessments, enabling precise simulations of network behavior.[1]Graph Theory Foundations

Transport networks are fundamentally represented using graph theory, where nodes correspond to intersections, stations, or origins/destinations, and edges represent links such as roads, rail segments, or routes. These graphs can be undirected, treating connections as bidirectional (e.g., two-way streets), or directed to account for one-way traffic flows or oriented paths in transit systems. Edges are typically weighted to incorporate attributes like distance, travel time, or cost, enabling quantitative analysis of network efficiency; for instance, weights might reflect free-flow travel times adjusted for congestion. Node degrees, defined as the number of incident edges, quantify local connectivity, with higher degrees indicating hubs like major interchanges that facilitate greater traffic throughput.[6][7] Key representational tools include the adjacency matrix, an matrix where if a direct edge exists from node to (and 0 otherwise), which efficiently encodes pairwise connections for computational algorithms in transport routing. The incidence matrix, an matrix with rows for nodes and columns for edges, uses +1 for the originating node, -1 for the terminating node, and 0 elsewhere in directed graphs, aiding in flow conservation constraints for traffic models. Shortest path problems, central to route optimization, seek the minimum-cost route between nodes; Dijkstra's algorithm solves this for non-negative weights by iteratively selecting the lowest-distance unvisited node, building a shortest path tree from the source without revisiting nodes. The shortest path distance between nodes and is formally defined as: where denotes the set of all paths from to , and is the weight of edge .[6][8][7] Network properties provide insights into structural robustness and performance. Connectivity assesses whether paths exist between all node pairs; a graph is strongly connected if directed paths link every pair, essential for reliable transport systems without isolated components. Centrality measures evaluate node importance: degree centrality counts incident edges, betweenness centrality quantifies the fraction of shortest paths passing through a node (e.g., , where is the total shortest paths from to and those via ), and closeness centrality measures inverse average shortest path distance to others (e.g., ), highlighting critical junctions for flow control or vulnerability. Cycles, closed loops of edges, introduce redundancy but can complicate equilibrium computations, while spanning trees—acyclic connected subgraphs covering all nodes—underpin minimal connector structures, such as minimum spanning trees that minimize total edge weight for basic coverage in network design.[9][10][6]Historical Development

Early Pioneers and Models

The foundations of transport network analysis trace back to Leonhard Euler's seminal 1736 work on the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem, which is widely regarded as the origin of graph theory and its application to network problems. In this problem, Euler analyzed whether it was possible to traverse all seven bridges connecting four landmasses in the city of Königsberg exactly once and return to the starting point, modeling the landmasses as vertices and the bridges as edges in a graph. He proved it impossible by demonstrating that the graph had more than two vertices of odd degree, establishing key concepts like paths and degrees that later proved essential for analyzing connectivity in transport networks such as roads and railways.[11] In the 19th century, advancements in electrical network theory provided analogous frameworks for understanding flows in transport systems. Gustav Kirchhoff introduced his two circuit laws in 1845, which describe the conservation of charge (current law) and energy (voltage law) in electrical circuits, enabling the analysis of currents and potentials across branched networks. These principles, originally developed for electrical conduction, offered early mathematical tools for modeling flow conservation and potential differences, concepts directly transferable to transport flows like vehicle traffic or commodity movement along interconnected paths.[12] Early 20th-century contributions shifted focus toward practical transport and location decisions within networks. Alfred Weber's 1909 theory of industrial location emphasized minimizing transportation costs in network-based site selection, using isodapane maps to balance material sourcing, market proximity, and labor costs while accounting for network distances rather than straight-line Euclidean ones. Weber's model highlighted how network topology influences optimal facility placement, influencing urban planning and logistics by prioritizing least-cost paths over geographic proximity.[13] A pivotal development occurred in 1939 when Leonid Kantorovich introduced linear programming as a method for optimal resource allocation, including transport problems. In his work, Kantorovich formulated mathematical techniques to minimize costs in production and distribution networks, using systems of linear inequalities to solve for efficient flows and assignments under constraints like capacity limits. This approach laid the groundwork for systematic optimization in transport planning, bridging theoretical models with practical resource distribution.[14] These early models evolved into post-war computational methods that enabled large-scale empirical applications.Post-War Advancements

Following World War II, transport network analysis advanced significantly through the integration of operations research techniques, enabling the modeling of capacity constraints and optimization in complex networks. In 1956, Lester R. Ford Jr. and Delbert R. Fulkerson introduced the max-flow min-cut theorem, which provided a foundational algorithm for determining the maximum flow in capacitated networks, including applications to traffic evacuation scenarios where it optimizes evacuation routes under link capacity limits.[15] This theorem, implemented via the Ford-Fulkerson algorithm, allowed analysts to identify bottlenecks and ensure efficient resource allocation in emergency transport planning, marking a shift toward computational solutions for real-world infrastructure challenges.[16] The influence of operations research further propelled these developments, with George B. Dantzig's simplex method—originally formulated in 1947 for linear programming—adapted for transport problems by the early 1950s and widely applied in planning during the 1960s.[17] Dantzig's approach facilitated the solution of transportation allocation models, optimizing the distribution of goods and vehicles across networks while accounting for costs and capacities, which became essential for urban and regional planning initiatives in post-war economic recovery. Institutional support grew concurrently, as the Highway Research Board (renamed the Transportation Research Board in 1974) expanded its activities in the 1950s to foster collaborative research on network modeling and traffic flow, influencing policy and methodology standardization. By the 1970s, the field saw the rise of user-equilibrium models, building on John G. Wardrop's 1952 principles that defined equilibrium as the state where no user can reduce travel time by unilaterally changing routes. These principles were computationally implemented in the 1970s through algorithms for traffic assignment, enabling simulations of congested networks where travel costs reflect user choices. The 1973 oil crisis accelerated this evolution, prompting studies on energy-efficient network designs that incorporated fuel consumption into assignment models to minimize overall system energy use amid rising costs and supply disruptions.[18] Early software tools like SATURN (Simulation and Assignment of Traffic to Urban Road Networks), developed in the 1970s at the University of Leeds, exemplified these advancements by integrating equilibrium-based assignment with dynamic simulation for evaluating traffic management strategies.Network Representation

Data Structures and Models

Transport networks are fundamentally represented using node-link models, where nodes represent intersections, terminals, or points of interest, and links denote the connections between them, such as roads, rails, or routes. This graph-theoretic structure allows for the abstraction of complex infrastructure into analyzable components, enabling computations of flows, paths, and capacities.[6][5] Hierarchical networks extend this by organizing nodes and links into multiple levels, often through zoning for aggregation, where finer-grained details (e.g., individual streets) are grouped into broader zones (e.g., neighborhoods or districts) to reduce computational complexity while preserving essential connectivity. This approach is particularly useful in large-scale urban planning, balancing detail and efficiency in model scalability.[19][20] For time-dependent phenomena, temporal graphs incorporate time-varying edges or node attributes, capturing dynamic elements like varying traffic volumes or schedule changes in transport systems. These models extend static graphs by associating timestamps with links, facilitating analysis of evolving network states over periods such as peak hours.[21][22] Modeling approaches in transport networks distinguish between static and dynamic paradigms: static models assume constant conditions across a time horizon, suitable for long-term planning with aggregated data, while dynamic models account for time progression, such as evolving congestion or route choices.[23][24] Stochastic elements further enhance these by incorporating uncertainty, treating demand or delays as probabilistic variables to simulate variability in real-world scenarios like fluctuating passenger loads or weather-induced disruptions.[25][26] Standardized formats facilitate interoperability in data representation, including GIS-based structures like Shapefiles for vector-based node-link geometries and the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) for transit schedules, which define stops, routes, and timetables in a tabular CSV format in a ZIP archive.[27] These standards ensure compatibility across software tools for network loading and visualization. Essential data requirements include link attributes such as length, free-flow speed, and capacity, alongside node attributes like type (e.g., junction or origin) and associated demand. A foundational principle is flow conservation, ensuring balance at intermediate nodes, expressed as: where denotes flow on link from node to , excluding sources and sinks.[5][28]Spatial and Attribute Data

Spatial data in transport network analysis primarily consists of vector-based representations, such as points for nodes (e.g., intersections or stops) defined by geocoded latitude and longitude coordinates, and polylines for links (e.g., road segments) that connect these nodes to model linear infrastructure like highways or rail lines.[29] Vector formats are preferred over raster representations in transport contexts because they efficiently capture discrete network topologies with precise geometric accuracy, whereas rasters, which divide space into grid cells, are better suited for continuous phenomena like land use but introduce unnecessary computational overhead for linear features.[30] Key sources for this spatial data include crowdsourced platforms like OpenStreetMap (OSM), which provides global coverage of road networks through volunteer contributions, and official national surveys such as the U.S. National Transportation Atlas Database (NTAD), maintained by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, offering standardized geospatial datasets for multimodal infrastructure.[31][32] Attribute data enriches these spatial elements with non-geometric properties essential for analysis, including traffic volumes measured as average daily traffic (ADT) on links, vehicle types categorized by classifications like passenger cars or heavy trucks, and environmental factors such as elevation profiles for vertical alignment or weather impacts on capacity.[33][34] For instance, traffic volumes are derived from continuous count stations or short-term surveys extrapolated via adjustment factors, while vehicle type breakdowns support differentiated modeling of flow behaviors.[33] Real-time attribute data increasingly comes from Internet of Things (IoT) sensors and feeds, such as inductive loops embedded in pavements for detecting vehicle presence and speed, or connected vehicle systems transmitting anonymized location and velocity data to update network states dynamically.[35][36] Data quality issues significantly affect the reliability of transport network models, with accuracy referring to the positional fidelity of spatial elements (e.g., link geometries matching real-world surveys within meters) and completeness addressing gaps in coverage, such as underrepresented rural roads in crowdsourced datasets.[37] In attribute data, incompleteness arises from inconsistent sensor deployment, leading to biased volume estimates, while inaccuracies in environmental attributes like elevation can skew gravity-based accessibility calculations.[38] Privacy concerns are paramount, particularly with real-time IoT data that may inadvertently capture personal identifiers; in Europe, compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), effective since May 2018, requires pseudonymization of location traces and explicit consent for processing, imposing fines up to €20 million or 4% of the total worldwide annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher, for serious violations in transport applications like fleet tracking.[39][40] Integration challenges emerge when combining multi-scale data, where microscopic details (e.g., lane-level geometries from high-resolution LiDAR surveys) must align with macroscopic zonal aggregates (e.g., traffic districts from census blocks) without introducing aggregation errors or topological inconsistencies.[41] For example, mismatched scales can cause disaggregate link attributes to misalign with aggregate zone centroids, complicating hybrid models that transition from detailed simulations to broader planning.[42] Addressing these requires standardized referencing systems, such as linear referencing methods, to ensure seamless fusion across resolutions while preserving data integrity.[43]Core Analytical Methods

Path Optimization Techniques

Path optimization techniques in transport network analysis focus on identifying the most efficient routes between origins and destinations, minimizing criteria such as travel time, distance, or cost while accounting for network constraints like capacity and topology. These methods are essential for individual vehicle routing and fleet management, treating transport networks as weighted graphs where nodes represent intersections or stops and edges denote road segments with associated weights. Transport networks are typically modeled as directed graphs with non-negative edge weights to reflect realistic travel conditions, as detailed in foundational graph theory approaches.[44] A foundational algorithm for single-source shortest paths is Dijkstra's algorithm, which computes the minimum-cost path from a source node to all other nodes in a graph with non-negative weights by maintaining a priority queue of tentative distances and iteratively selecting the node with the smallest distance. Introduced by Edsger W. Dijkstra in 1959, it guarantees optimality under the assumption of non-negative weights and has a computational complexity of O((V + E) log V) when implemented with Fibonacci heaps, where V is the number of vertices and E the number of edges, making it suitable for sparse transport networks.[44] For large-scale transport applications, the A* algorithm extends Dijkstra's approach by incorporating a heuristic estimate of the remaining distance to the goal, such as Euclidean distance or road network approximations, to guide the search and reduce explored nodes. Developed by Peter Hart, Nils Nilsson, and Bertram Raphael in 1968, A* is admissible and optimal if the heuristic is consistent, enabling faster computation in expansive urban or highway networks.[45] Variants address more complex scenarios, including multi-objective optimization, where paths balance conflicting criteria like time versus monetary cost or emissions. In transport networks, multi-objective shortest path problems generate Pareto-optimal sets of routes, often solved via label-setting algorithms that propagate non-dominated vectors of costs.[46] Another key variant is the vehicle routing problem (VRP), which optimizes paths for a fleet of vehicles with capacity constraints, starting and ending at a depot while serving customer locations to minimize total distance or cost. Formulated by George Dantzig and John Ramser in 1959 for truck dispatching, VRP incorporates constraints like vehicle load limits and time windows, extending basic shortest path methods to combinatorial optimization. The total path cost in these techniques is typically defined as , where are the weights (e.g., distances or times) along the edges of the path.[47] These techniques find widespread applications in navigation systems, where real-time variants of Dijkstra's and A* algorithms power GPS routing by integrating live traffic data to suggest optimal paths. In logistics, VRP solvers optimize delivery routes for e-commerce and supply chains, reducing fuel consumption and operational costs in urban distribution networks.[48][49]Traffic Assignment Models

Traffic assignment models distribute a specified traffic demand across a transportation network to estimate link volumes, travel times, and congestion patterns, serving as a critical component in predicting network performance under varying conditions. These models simulate route choices by travelers, assuming rational behavior influenced by travel costs such as time and congestion, and are typically applied in static or quasi-static frameworks for planning purposes. The equilibrium state achieved in these models reflects a balance where route selections stabilize given the induced costs.[50] The user equilibrium (UE) model, based on Wardrop's first principle, posits that each traveler selects a route that minimizes their individual travel time, resulting in a state where no user can unilaterally improve their journey by switching paths. Introduced in 1952, this principle assumes perfect information and non-cooperative behavior among users, leading to equal minimum travel times on all utilized paths between an origin-destination pair and longer times on unused paths. UE is widely adopted for its behavioral realism in modeling selfish routing decisions in congested networks.[50] In contrast, the system optimal (SO) model, derived from Wardrop's second principle, aims to minimize the aggregate travel time across all users in the network, promoting cooperative routing to achieve global efficiency. This approach often requires centralized control or incentives, as it may assign some users to longer individual paths to reduce overall system costs. Stochastic variants of SO incorporate uncertainty in route choices, such as perceptual variations in travel times, by using probabilistic distributions to model demand allocation while still targeting total system minimization.[50][51] Congestion effects in both UE and SO models are commonly captured through link performance functions that relate travel time to flow volume. The Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) function, developed in 1964, provides a standard empirical form for this relationship: where is the average travel time on link , is the free-flow travel time, is the traffic volume, is the capacity, and typical parameters are and . This function assumes increasing delays beyond capacity utilization, enabling realistic simulation of bottlenecks.[52] To solve the UE problem, formulated as a convex mathematical program, the Frank-Wolfe algorithm is a foundational method that iteratively performs all-or-nothing traffic assignments along shortest paths followed by line search adjustments to update link flows. First applied to traffic networks in 1956 by Beckmann, McGuire, and Winsten,[53] this successive approximation technique converges to the equilibrium under mild conditions on link cost functions, making it computationally efficient for large-scale networks despite slower convergence near the optimum.Location and Accessibility Analysis

Location models in transport network analysis focus on determining optimal sites for facilities to enhance service efficiency and equity. The p-median problem seeks to locate a fixed number of facilities, p, to minimize the average distance between demand points and their assigned facilities, often formulated as an integer linear program where distances are derived from network paths.[54] This model assumes facilities serve nearest demands and is particularly suited for scenarios where travel costs dominate decision-making, such as in communication or logistics networks. In contrast, the set covering problem aims to minimize the number of facilities needed to ensure all demand points are within a specified coverage distance or time, treating the problem as a binary optimization to select sites that collectively cover the entire demand set without overlap requirements.[55] These models rely on graph representations of transport networks, where nodes represent potential facility sites and demand locations, and edges capture connectivity and impedances like travel time. Accessibility indices quantify the ease of reaching opportunities across a transport network, providing a measure of reachability beyond simple coverage. Gravity-based measures, inspired by Newtonian physics, calculate accessibility at origin i as , where represents the mass of opportunities (e.g., jobs or services) at destination j, is the network distance between i and j, and is a decay parameter reflecting impedance sensitivity, typically calibrated empirically between 1 and 2 for urban transport contexts.[56] This formulation weights closer opportunities more heavily, capturing diminishing returns with distance and enabling comparisons of network performance across regions. For retail applications, the Huff model extends this by estimating the probability that a customer at i patronizes facility j as , where is facility size or attractiveness and is a similar decay parameter, defining probabilistic catchment areas for store siting.[57] These techniques find practical use in siting essential facilities within transport networks. For hospitals, the p-median model has been applied to optimize locations by minimizing weighted travel times to emergency services, balancing population density and network congestion in urban settings.[58] School placement often employs set covering to ensure all neighborhoods are within walking or short bus distances, minimizing the number of sites while achieving full coverage under budget constraints.[59] In emerging contexts like electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure, gravity-based indices guide charging station placement by assessing accessibility to high-demand routes, incorporating travel patterns to maximize coverage for long-distance trips.[60] Evaluation of location and accessibility often incorporates centrality metrics adapted to transport contexts, such as betweenness or closeness centrality weighted by network flows, to identify nodes with high reachability potential without delving into detailed graph theory derivations. These metrics help validate facility placements by highlighting bottlenecks or underserved areas, ensuring proposed sites enhance overall network equity.[61]Specialized Applications

Service Area and Coverage Modeling

Service area and coverage modeling in transport network analysis involves delineating the geographic regions effectively served by transport facilities, such as stations or routes, to evaluate reach and efficiency. These methods partition space based on proximity or travel time, enabling planners to assess how well a network meets demand across a study area. By defining boundaries around facilities, analysts can quantify coverage and identify gaps, ensuring resources are allocated to maximize accessibility without overlapping redundantly. This approach is distinct from broader accessibility measures, which it complements by focusing on boundary-specific evaluations. Thiessen polygons, also known as Voronoi diagrams in their generalized form, partition a plane into regions where each polygon encompasses all points closer to a specific facility than to any other, based on Euclidean or network distance. In transport contexts, these diagrams are constructed around transit stops or depots to define exclusive service zones, facilitating the analysis of catchment areas for route optimization. For instance, network-constrained Voronoi diagrams account for road or rail topologies, ensuring boundaries align with actual travel paths rather than straight-line distances. This method, rooted in geometric tessellations, has been applied since the early 20th century but gained prominence in transport planning through computational advancements in GIS. A key application involves delineating transit traffic analysis zones (TTAZs) by connecting stations via Delaunay triangulation and generating polygons, which can improve ridership forecasting accuracy compared to uniform zoning. Buffer analysis extends this by creating zones of fixed radius or travel time around facilities, with radial buffers using straight-line distance for simplicity and network-based buffers incorporating impedance like speed limits or turns. A prominent variant is the isochrone, which maps areas reachable within a specified time threshold, such as 30 minutes by public transit, revealing time-dependent coverage influenced by schedules and congestion. These are generated using shortest-path algorithms on transport graphs, often via breadth-first search extensions, to produce irregular polygons that better reflect real-world accessibility than circular buffers. In urban settings, isochrones highlight disparities in service reach, such as how peak-hour traffic can significantly reduce effective coverage in dense areas. Coverage metrics quantify the effectiveness of these modeled areas, typically as the percentage of population or demand points falling within defined service radii or isochrones. For example, transit coverage might measure the proportion of residents within a 400-meter walking buffer of stops, often high in well-served cities such as many in Europe. Equity considerations employ indices like the Gini coefficient, which assesses spatial disparities in coverage by comparing cumulative service distribution against perfect equality, with values closer to 0 indicating balanced access. Applied to transit, a Gini coefficient below 0.3 suggests equitable distribution, while higher values flag underserved low-income areas, as observed in analyses of U.S. metropolitan systems. These metrics prioritize population-weighted evaluations to address social impacts, using Lorenz curves for visualization. In public transit route planning, service area models guide expansions by simulating coverage under proposed alignments, ensuring new lines fill gaps identified via Voronoi partitions or isochrones. For emergency response zones, Voronoi diagrams define dispatch territories around fire or ambulance stations, optimizing response times by assigning incidents to the nearest facility within network constraints. These applications underscore the role of coverage modeling in enhancing network resilience and fairness.Reliability and Fault Assessment

Reliability and fault assessment in transport network analysis evaluates the robustness of infrastructure against disruptions, such as component failures or external events, to ensure sustained connectivity and performance under uncertainty.[62] This involves quantifying how network degradation affects travel flows, times, and accessibility, guiding designs that incorporate redundancy and resilience.[63] Vulnerability analysis identifies critical links and nodes whose failure disproportionately impacts overall network function. Betweenness centrality, which measures the proportion of shortest paths passing through a link, is widely used to pinpoint these elements, as high-betweenness links carry disproportionate traffic loads and amplify disruptions when removed.[64] For instance, the traffic flow betweenness index (TFBI) extends this by integrating flow volumes and origin-destination demands, ranking links for targeted assessment; in a case study of Changchun's road network, TFBI identified 250 critical links in the central business district, reducing computational demands by 93.5% compared to full scans.[64] Reserve capacity, defined as the additional loading a network can handle before congestion thresholds are breached, provides redundancy by allowing alternative routing during failures; enhancing capacity on high-saturation links in Stockholm's public transport network helped mitigate welfare losses from disruptions in simulated scenarios.[65] Reliability metrics focus on probabilistic measures of network performance post-disruption. Network reliability is commonly defined as the probability that origins and destinations remain connected within acceptable service levels, such as travel time not exceeding a threshold :where is the travel time under degradation.[62] Seminal work by Du and Nicholson formalized this for degradable systems, calculating as the probability that flow reductions stay below specified limits using equilibrium models.[63] For robust design under uncertainty, two-stage stochastic programming optimizes first-stage infrastructure investments (e.g., link capacities) before demand realization, followed by second-stage flow adjustments; this approach balances costs and reliability in mixed-integer linear frameworks, as applied to freight networks with random demand variations.[66] Fault scenarios encompass link or node failures from structural issues, like bridge collapses, or broader events such as natural disasters, which sever connectivity and cascade delays.[67] In the 2005 Hurricane Katrina case, the I-10 Twin Span Bridge collapse isolated New Orleans, halting evacuations and freight for over a month with $35 million in repairs, while rail lines like CSX's Gulf Coast Mainline faced $250-300 million in damage and five-month closures, underscoring vulnerabilities in coastal infrastructure.[67] Under such uncertainties, expected travel time aggregates scenario-based outcomes:

where is the probability of failure scenario and its travel time, enabling planners to prioritize resilient configurations over deterministic baselines.[68]