Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

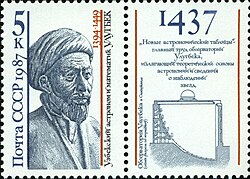

Ulugh Beg

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Mīrzā Muhammad Tarāghāy bin Shāhrukh (Chagatay: میرزا محمد تراغای بن شاهرخ; Persian: میرزا محمد طارق بن شاهرخ), better known as Ulugh Beg (Persian: الغبیک; 22 March 1394 – 27 October 1449),[a] was a Timurid sultan, as well as an astronomer and mathematician.

Ulugh Beg was notable for his work in astronomy-related mathematics, such as trigonometry and spherical geometry, as well as his general interests in the arts and intellectual activities.[1][2] It is thought that he spoke five languages: Arabic, Persian, Chaghatai Turkic, Mongolian, and a small amount of Chinese.[3] During his rule (first as a governor, then outright) the Timurid Empire achieved the cultural peak of the Timurid Renaissance through his attention and patronage. Samarkand was captured and given to Ulugh Beg by his father Shah Rukh.[4][5]

He built the great Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand between 1424 and 1429. It was considered by scholars to have been one of the finest observatories in the Islamic world at the time and the largest in Central Asia.[1] Ulugh Beg was subsequently recognized as the most important observational astronomer from the 15th century by many scholars.[6] He also built the Ulugh Beg Madrasah (1417–1420) in Samarkand and Bukhara, transforming the cities into cultural centers of learning in Central Asia.[7]

However, Ulugh Beg's scientific expertise was not matched by his skills in governance. During his short reign, he failed to establish his power and authority. As a result, other rulers, including his family, took advantage of his lack of control, and he was subsequently overthrown and assassinated.[8]

Early life

[edit]He was a grandson of the great conqueror and king, Timur (Tamerlane) (1336–1405), and the oldest son of Shah Rukh, both of whom came from the Turkicized Mongol Barlas tribe of Transoxiana (now Uzbekistan).[9] His mother was a noblewoman named Gawhar Shad, daughter of a member of the representative Turkic[10][11] tribal aristocracy, Ghiyasuddin Tarkhan.

Ulugh Beg was born in Sultaniyeh during his grandfather's invasion of Persia. He was given the name Mīrzā Muhammad Tāraghay. Ulugh Beg, the name he was most commonly known by, was not truly a personal name, but rather a moniker, which can be loosely translated as "Great Ruler" (compare modern Turkish ulu, "great", and bey, "chief") and is the Turkic equivalent of Timur's Perso-Arabic title Amīr-e Kabīr.[12]

As a child he wandered through a substantial part of the Middle East and India as his grandfather expanded his conquests in those areas. After Timur's death, Shah Rukh moved the empire's capital to Herat (in modern Afghanistan). Sixteen-year-old Ulugh Beg subsequently became the governor of the former capital of Samarkand in 1409. In 1411, he was named the sovereign ruler of the whole of Mavarannahr.

Science

[edit]The teenage ruler set out to turn the city into an intellectual center for the empire. Between 1417 and 1420, he built a madrasa ("university" or "institute") on Registan Square in Samarkand (currently in Uzbekistan), and he invited numerous Islamic astronomers and mathematicians to study there. The madrasa building still survives. Ulugh Beg's most famous pupil in astronomy was Ali Qushchi (died in 1474). Qadi Zada al-Rumi was the most notable teacher at Ulugh Beg's madrasa and Jamshid al-Kashi, an astronomer, later came to join the staff.[3]

Astronomy

[edit]

Astronomy piqued Ulugh Beg's interest when he visited the Maragheh Observatory at a young age. This observatory, located in Maragheh, Iran, is where the well-known astronomer Nasir al-Din al-Tusi practised.[6]

In 1428, Ulugh Beg built an enormous observatory, similar to Tycho Brahe's later Uraniborg as well as Taqi al-Din's observatory in Constantinople. Lacking telescopes to work with, he increased his accuracy by increasing the length of his sextant; the so-called Fakhri sextant had a radius of about 36 meters (118 feet) and the optical separability of 180" (seconds of arc). The Fakhri sextant was the largest instrument at the observatory in Samarkand (an image of the sextant is on the side of this article). There were many other astronomical instruments located at the observatory, but the Fakhri sextant is the most well-known instrument there. The purpose of the Fakhri sextant was to measure the transit altitudes of the stars. This was a measurement of the maximum altitude above the horizon of the stars. It was only possible to use this device to measure the declination of celestial objects.[13] The image, which can be found in this article, shows the remaining portion of the instrument, which consists of the underground, lower portion of the instrument that was not destroyed. The observatory built by Ulugh Beg was the most pervasive and well-known observatory throughout the Islamic world.[3]

With the instruments located in the observatory in Samarkand, Ulugh Beg composed a star catalogue consisting of 1018 stars, which is eleven fewer stars than are present in the star catalogue of Ptolemy. Ulugh Beg utilized dimensions from al-Sufi and based his star catalogue on a new analysis that was autonomous from the data used by Ptolemy.[14] Throughout his life as an astronomer, Ulugh Beg came to realize that there were multiple mistakes in the work and subsequent data of Ptolemy that had been in use for many years.[2]

Using it, he compiled the 1437 Zij-i-Sultani of 994 stars, generally considered the greatest star catalogue between those of Ptolemy and Tycho Brahe, a work that stands alongside Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's Book of Fixed Stars.[15][16] The serious errors which he found in previous Arabian star catalogues (many of which had simply updated Ptolemy's work, adding the effect of precession to the longitudes) induced him to redetermine the positions of 992 fixed stars, to which he added 27 stars from Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's catalogue Book of Fixed Stars from the year 964, which were too far south for observation from Samarkand. This catalogue, one of the most original of the Middle Ages, was first edited by Thomas Hyde at Oxford in 1665 under the title Jadāvil-i Mavāzi' S̱avābit, sive, Tabulae Long. ac Lat. Stellarum Fixarum ex Observatione Ulugh Beighi and reprinted in 1767 by G. Sharpe. More recent editions are those by Francis Baily in 1843 in Vol. XIII of the Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society, and by Edward Ball Knobel in Ulugh Beg's Catalogue of Stars, Revised from all Persian Manuscripts Existing in Great Britain, with a Vocabulary of Persian and Arabic Words (1917).

In 1437, Ulugh Beg determined the length of the sidereal year as 365.2570370...d = 365d 6h 10m 8s (an error of +58 seconds). In his measurements over the course of many years he used a 50 m high gnomon. This value was improved by 28 seconds in 1525 by Nicolaus Copernicus, who appealed to the estimation of Thabit ibn Qurra (826–901), which had an error of +2 seconds. However, Ulugh Beg later measured another more precise value of the tropical year as 365d 5h 49m 15s, which has an error of +25 seconds, making it more accurate than Copernicus's estimate which had an error of +30 seconds. Ulugh Beg also determined the Earth's axial tilt as 23°30'17" in the sexagesimal system of degrees, minutes and seconds of arc, which in decimal notation converts to 23.5047°.[17]

Mathematics

[edit]In mathematics, Ulugh Beg wrote accurate trigonometric tables of sine and tangent values correct to at least eight decimal places.[18]

Foreign relations

[edit]Once Ulugh Beg became governor of Samarqand, he fostered diplomatic relations with the Yongle emperor of the Ming dynasty.[19] In 1416, Ming envoys Chen Cheng and Lu An presented silk and silver stuffs to Ulugh Beg on behalf of the Yongle emperor.[19] In 1419, The Timurid sent his own emissaries, Sultan-Shah and Muhammad Bakhshi, to the Ming court.[20] Ulugh Beg's emissaries came across Ghiyāth al-dīn Naqqāsh and other envoys representing Shah Rukh, Prince Baysunghur, and other Timurid authorities in Beijing; however, they stayed at separate hostelries.[21] Ghiyāth al-dīn Naqqāsh even saw the Yongle emperor riding a black horse with white feet which had been gifted by Ulugh Beg.[22]

Ulugh Beg led two major campaigns against his neighbours. This first one took place in 1425 and was directed against Moghulistan and its ruler Shir Muhammad. He was victorious but the impact of the campaign was limited and Shir Muhammad remained in power. A year later, Baraq, Khan of the Golden Horde and former protégé of Ulugh Beg, laid claim to Timurid possessions around the Syr Darya, including the town of Sighnaq. In response to that, in 1427 Ulugh Beg, accompanied by his brother Muhummad Juki, marched against Baraq. In a hill close to Sighnaq the Timurid army was surprised by a smaller enemy force but was soundly defeated. The humiliation suffered at the hands of Baraq was to have a lasting effect on Ulugh Beg. His campaign against the Golden Horde would be the last he would undertake against a neighbouring power. The armies he later sent against them would not win any resounding victories and by the end of his reign his territories would be raided by his northern and easterly foes.[23]

In 1439, the Zhengtong emperor ordered an artist to produce a painting of a black horse with white feet and a white forehead that had been sent by Ulugh Beg.[24] Six years later, the Ming emperor sent a letter to Ulugh Beg in order to express his gratitude for all the "tribute" from Samarqand.[24] The emperor sent "vessels made of gold and jade, a spear with a dragon's head, a fine horse with saddle, and variegated gold-embroidered silk stuffs" to Ulugh Beg, as well as silk stuffs and garments for the Timurid prince's family.[24]

War of succession and death

[edit]

In 1447, upon learning of the death of his father Shah Rukh, Ulugh Beg went to Balkh. Here, he heard that Ala al-Dawla, the son of his late brother Baysunghur, had claimed the rulership of the Timurid Empire in Herat. Consequently, Ulugh Beg marched against Ala al-Dawla and met him in battle at Murghab. He defeated his nephew and advanced toward Herat, massacring its people in 1448. However, Abul-Qasim Babur Mirza, Ala al-Dawla's brother, came to the latter's aid and defeated Ulugh Beg.[13]

Ulugh Beg retreated to Balkh where he found that its governor, his oldest son Abdal-Latif Mirza, had rebelled against him. Another civil war ensued.[13] Abdal-Latif recruited troops to meet his father's army on the banks of the Amu Darya river. However, Ulugh Beg was forced to retreat to Samarkand before any fighting took place, having heard news of turmoil in the city. Abdal-Latif soon reached Samarkand and Ulugh Beg involuntarily surrendered to his son. Abd-al-Latif released his father from custody, allowing him to make pilgrimage to Mecca. However, he ensured Ulugh Beg never reached his destination, having him, as well as his brother Abdal-Aziz assassinated in 1449.[25][26][27]

Eventually, Ulugh Beg's reputation was rehabilitated by his nephew, Abdallah Mirza (1450–1451), who placed his remains at Timur's feet in the Gur-e-Amir in Samarkand,[28] where they were found by Soviet archaeologists in 1941.

Marriages

[edit]Ulugh Beg had sixteen consorts:

- Aka Begi, daughter of Muhammad Sultan Mirza bin Jahangir Mirza and Khan Sultan Khanika, mother of Habiba Sultan known as Khanzada Begum and another Khanzada Begum;

- Sultan Badi al-mulk Begum, daughter of Khalil Sultan bin Miran Shah and Shad Malik Agha;

- Aqi Sultan Khanika, daughter of Sultan Mahmud Khan Ogeday;

- Husn Nigar Khanika, daughter of Shams-i-Jahan Khan Chaghatay;

- Shukr Bi Khanika, daughter of Darwīsh Khan of the Golden Horde;

- Rukaiya Sultan Agha, an Arlat lady, and mother of Abdal-Latif Mirza, Ak Bash Begum and Sultan Bakht Begum;

- Mihr Sultan Agha, daughter of Tukal bin Sarbuka;

- Sa'adat Bakht Agha, daughter of Bayan Kukaltash, mother of Qutlugh Turkhan Agha;

- Daulat Sultan Agha, daughter of Khawand Sa'id;

- Bakhti Bi Agha, daughter of Aka Sufi Uzbek;

- Daulat Bakht Agha, daughter of Sheikh Muhammad Barlas;

- Sultanim Agha, mother of Abdul Hamid Mirza and Abdul Jabrar Mirza;

- Sultan Malik Agha, daughter of Nasir-al-Din, mother of Ubaydullah Mirza, Abdullah Mirza and another Abdullah Mirza;

- A daughter of Abu'l-Khayr Khan, khan of Uzbek Khanate;

- Khutan Agha;

- A daughter of Aqila Sultan;

Legacy

[edit]

- The crater, Ulugh Beigh, on the Moon, was named after him by the German astronomer Johann Heinrich von Mädler on his 1830 map of the Moon.[31][32]

- 2439 Ulugbek, a main-belt asteroid which was discovered on 21 August 1977 by N. Chernykh at Nauchnyj, was named after him.

- The dinosaur Ulughbegsaurus was named after him in 2021.[33]

Exhumation

[edit]Soviet anthropologist Mikhail M. Gerasimov reconstructed the face of Ulugh Beg. Like his grandfather Timurlane, Ulugh Beg is close to the Mongoloid type with slightly Europoid features.[34][35] His father Shah Rukh had predominantly Caucasoid features, with no obvious Mongoloid feature.[36][37]

See also

[edit]- Aryabhata, ancient Indian astronomer

- Ulugh Beg Observatory and Museum

- Ulugh Beg Madrasa in Samarkand

- Ulugh beg Madrasa in Bukhara

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ulugh or Үлэг in Cyrillic probably meant "the eldest" in Mongolian language

References

[edit]- ^ a b Science in Islamic civilisation: proceedings of the international symposia: "Science institutions in Islamic civilisation", & "Science and technology in the Turkish and Islamic world"[1]

- ^ a b Ulugh Beg, OU Libraries, Britannica Academic

- ^ a b c "Samarkand: Ulugh Beg's Observatory". Depts.washington.edu.

- ^ "Ulugh Beg and His Observatory". University of Washington. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "Ulugh Beg". MacTutor. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Legacy of Ulugh Beg | Central Asian Monuments | Edited by H. B. Paksoy | CARRIE Books". Vlib.iue.it. Archived from the original on May 19, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ The global built environment as a representation of realities: By author:A.J.J. Mekking [2]

- ^ "Ulugh Beg". The University of Oklahoma Libraries. Britannica Academic. Archived from the original on September 19, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Timur", Online Academic Edition, 2007. Quotation: "Timur was a member of the Turkicized Barlas tribe, a Mongol subgroup that had settled in Transoxania..."

- ^ V. V. Bartold. Улугбек и его время [Ulug Beg and his time]. St Petersburg (1918). p. 37.

- ^ "Ulug Beg – Biografiya" Улугбек - Биография. Opklare.ru. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ B. F. Manz, "Tīmūr Lang", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006

- ^ a b c Krisciunas, Kevin (1992). "The Legacy of Ulugh Beg". In Paksoy, Hasan Bulent (ed.). Central Asian Monuments. Istanbul: Isis Press. Archived from the original on May 19, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2006 – via Carrie Books.

- ^ "The Star Catalogues of Ptolemaios and Ulugh Beg" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics.

- ^ Nakamura, Tsuko (2017). "The 28-Xiu constellations in East Asian calendars and analysis of their observation dates". p. 10. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ McCarthy, Dennis D. (2020). "Reference Systems. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-5081-7700-5. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ L. P. E. A. Sédillot, Prolégomènes des tables astronomiques d'OlougBeg: Traduction et commentaire (Paris: Firmin Didot Frères, 1853), pp. 87 & 253.

- ^ "Ulugh Beg (1393 - 1449)". mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Bretschneider, Emil (1910). Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources. Vol. 2. London, UK: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & co., ltd. p. 262.

- ^ Naqqash, Ghiyathuddin (1989). 'Report to Mirza Baysunghur on the Timurid Legation to the Ming Court at Peking' in A Century of Princes: Sources on Timurid History and Art. Translated by Thackston, W. M. Massachusetts: Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. p. 280.

- ^ Maitra, K. M. (1934). A Persian Embassy to China, Being an Extract from Zubdatu't Tawarikh of Hafiz Abru. Lahore, Pakistan. pp. 63–64.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Naqqash, Ghiyathuddin (1989). Report to Mirza Baysunghur on the Timurid Legation to the Ming Court at Peking in A Century of Princes: Sources on Timurid History and Art. Massachusetts: Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. p. 295.

- ^ bluedomes (March 18, 2025). "Ulugh Beg: a short biography". Blue Domes. Retrieved March 19, 2025.

- ^ a b c Bretschneider, Emil (1910). Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources. Vol. 2. London, UK: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & co., ltd. p. 263.

- ^ "ʿABD-AL-LAṬĪF MĪRZĀ – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org.

- ^ The history of Persia. Containing, the lives and memorable actions of its kings from the first erecting of that monarchy to this time; an exact Description of all its Dominions; a curious Account of India, China, Tartary, Kermon, Arabia, Nixabur, and the Islands of Ceylon and Timor; as also of all Cities occasionally mention'd, as Schiras, Samarkand, Bokara, &c. Manners and Customs of those People, Persian Worshippers of Fire; Plants, Beasts, Product, and Trade. With many instructive and pleasant digressions, being remarkable Stories or Passages, occasionally occurring, as Strange Burials; Burning of the Dead; Liquors of several Countries; Hunting; Fishing; Practice of Physick; famous Physicians in the East; Actions of Tamerlan, &c. To which is added, an abridgment of the lives of the kings of Harmuz, or Ormuz. The Persian history written in Arabick, by Mirkond, a famous Eastern Author that of Ormuz, by Torunxa, King of that Island, both of them translated into Spanish, by Antony Teixeira, who liv'd several Years in Persia and India; and now render'd into English.

- ^ Jonathan L. Lee, The "Ancient Supremacy": Bukhara, Afghanistan and the Battle for Balkh, 1731 (1996), p. 21

- ^ Ahmad Hasan Dani, Akhmadali Askarovich Askarov, Sergeĭ Pavlovich Gubin, Rediscovery of the civilization of Central Asia: integral study of silk roads, roads of dialogue, steppe route expedition in USSR (1991), p. 82

- ^ Woods (1990, pp. 43–45)

- ^ image, James Stuby based on NASA (2015), English: Ulugh Beigh, on the moon, retrieved December 2, 2018

- ^ image, James Stuby based on NASA (2015), English: Ulugh Beigh, on the moon, retrieved December 2, 2018

- ^ "Ulugh Beg". Perth Observer. August 25, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ Rieger, Sarah (September 7, 2021). "Newly discovered dinosaur predated tyrannosaurs — and at the time was a bigger apex predator". CBC. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ Frye, Richard Nelson (January 5, 2019). Greater Iran: A 20th-century Odyssey. Mazda. ISBN 9781568591773. Retrieved January 5, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gerasimov, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich (January 5, 1971). "Ich suchte Gesichter". J. B. Lippincott. Retrieved January 5, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Frye, Richard Nelson (March 22, 2005). Greater Iran: A 20th-century Odyssey. Mazda. ISBN 9781568591773 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gerasimov, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich (March 22, 1971). "The Face Finder". J. B. Lippincott – via Google Books.

Bibliography

[edit]- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ulugh Beg", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- 1839. L. P. E. A. Sedillot (1808–1875). Tables astronomiques d’Oloug Beg, commentees et publiees avec le texte en regard, Tome I, 1 fascicule, Paris. A very rare work, but referenced in the Bibliographie generale de l’astronomie jusqu’en 1880, by J.

- 1847. L. P. E. A. Sedillot (1808–1875). Prolegomenes des Tables astronomiques d’Oloug Beg, publiees avec Notes et Variantes, et precedes d’une Introduction. Paris: F. Didot.

- 1853. L. P. E. A. Sedillot (1808–1875). Prolegomenes des Tables astronomiques d’Oloug Beg, traduction et commentaire. Paris.

- Le Prince Savant annexe les étoiles, Frédérique Beaupertuis-Bressand, in Samarcande 1400–1500, La cité-oasis de Tamerlan : coeur d'un Empire et d'une Renaissance, book directed by Vincent Fourniau, éditions Autrement, 1995, ISSN 1157-4488.

- L'âge d'or de l'astronomie ottomane, Antoine Gautier, in L'Astronomie, (Monthly magazine created by Camille Flammarion in 1882), December 2005, volume 119.

- L'observatoire du prince Ulugh Beg, Antoine Gautier, in L'Astronomie, (Monthly magazine created by Camille Flammarion in 1882), October 2008, volume 122.

- Le recueil de calendriers du prince timouride Ulug Beg (1394–1449), Antoine Gautier, in Le Bulletin, n° spécial Les calendriers, Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales, juin 2007, pp. 117–123. d

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, Personnages marquants d'Asie centrale, du Turkestan et de l'Ouzbékistan, Paris, éditions L'Harmattan, 2004. ISBN 2-7475-7017-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Dalen, Benno van (2007). "Ulugh Beg: Muḥammad Ṭaraghāy ibn Shāhrukh ibn Tīmūr". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 1157–9. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

External links

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Ulugh Beg: a short biography March 18. 2025

- The observatory and memorial museum of Ulugbek

- Bukhara Ulugbek Madrasah

- Registan the heart of ancient Samarkand.

- Biography by School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St Andrews, Scotland

- Legacy of Ulug Beg Archived May 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- BBC's History of the World in 100 Objects, jade dragon cup, discusses its patronage by Ulugh Beg

Ulugh Beg

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth and Timurid Ancestry

Ulugh Beg was born Mirza Muhammad Taraghai on 22 March 1394 in Sulṭāniyya, Persia (modern-day Iran), during his grandfather Timur's invasion of the region.[3] He was the eldest son of Shah Rukh, Timur's fourth surviving son, who would later consolidate control over much of the empire by 1407, ruling from bases in Herat and Samarkand.[4] This lineage positioned Ulugh Beg within the ruling branch of the Timurid dynasty, inheriting claims to authority rooted in Timur's foundational conquests.[4] Timur, a Turco-Mongol warlord from the Barlas tribe of the Chagatai Khanate, built the empire through relentless campaigns beginning in the 1370s, subduing Transoxiana and eastern Persia by the early 1380s before completing the conquest of western Persia and Iraq by 1393. His forces, comprising mounted archers from nomadic tribes, extended Timurid dominion into the Caucasus, Anatolia, Syria, and notably India with the sack of Delhi in 1398, amassing tribute, slaves, and resources that formed the economic backbone for subsequent rulers like Shah Rukh and, indirectly, Ulugh Beg.[5] These victories secured vast territories across Central Asia and Persia, providing the manpower, wealth, and legitimacy that enabled the dynasty's stability and cultural patronage. As a scion of this lineage, Ulugh Beg's origins bridged the dynasty's nomadic Turco-Mongol heritage—emphasizing tribal alliances, mobile warfare, and steppe customs—with the increasingly sedentary Persianate influences of the conquered realms, where Timurid courts adopted Islamic administrative practices, poetry, and architecture from urban centers like Herat and Samarkand.[4] Timur's own blending of Mongol imperial ideology with Persian governance set this pattern, allowing heirs like Shah Rukh to govern through a mix of tribal loyalties and bureaucratic control, which Ulugh Beg would later navigate in his ascent.

Upbringing and Initial Education

Ulugh Beg, originally named Muhammad Taraghay, was born on March 22, 1394, in Sultaniyya during his grandfather Timur's military campaign in northern Iran.[6] As the eldest son of Shah Rukh, Timur's fourth son, and grandson of the conqueror, he was raised amid the peripatetic Timurid court, frequently accompanying Timur on campaigns that defined a era of relentless expansion and instability.[4] This early exposure to martial affairs provided foundational political training, yet the court's scholarly circles introduced him to broader intellectual pursuits.[4] Following Timur's death in 1405, Shah Rukh consolidated power by 1407, relocating the capital to Herat and prioritizing administrative stability and cultural revival over his father's conquests.[4] Ulugh Beg spent his formative years in this Herat-based environment, benefiting from Shah Rukh's patronage of arts and learning, which created a relatively peaceful backdrop for education compared to Timur's turbulent reign.[4] The Timurid court's emphasis on intellectual endeavors, including libraries and gatherings of scholars, shaped his worldview amid ongoing princely duties.[4] His initial tutelage, drawn from court scholars, encompassed Islamic sciences such as Qur'anic studies and jurisprudence, alongside history and introductory mathematics, promoting a harmony between orthodox religious principles and empirical reasoning.[6] These studies cultivated early inclinations toward rational inquiry, evident in his personal engagements with poetry composition and historical documentation, which demonstrated a versatile cultural aptitude prior to deeper specialization.[4][6]Rise to Power

Governorship of Samarkand

In 1409, Ulugh Beg, then aged fifteen, was appointed by his father Shah Rukh as governor of Samarkand and the surrounding Transoxiana region, following Shah Rukh's consolidation of power after Timur's death in 1405.[7][4] This role positioned him to oversee a key Timurid stronghold, capitalizing on Samarkand's central location along the Silk Road trade routes, which supported economic vitality through commerce in goods like silk, spices, and intellectual exchanges among scholars from Persia, China, and beyond.[8] Ulugh Beg's administration emphasized infrastructural development over military expansion, initiating projects that enhanced the city's cultural and educational prominence. Between 1417 and 1420, he oversaw the construction of the Ulugh Beg Madrasa on the Registan Square, a monumental complex designed to serve as a hub for advanced studies in mathematics, astronomy, and Islamic jurisprudence, attracting scholars and elevating Samarkand's status as an intellectual center.[9][10] While remaining subordinate to Shah Rukh, who governed the broader empire from Herat, Ulugh Beg exercised de facto authority in Samarkand from approximately 1411 onward, fostering local stability by integrating Timurid oversight with regional autonomy and avoiding large-scale unrest through measured policies that prioritized prosperity and scholarly patronage.[11][3]Role in Shah Rukh's Empire

Ulugh Beg was appointed governor of Transoxiana by his father Shah Rukh around 1409, at the age of fifteen, with Samarkand serving as his administrative center while Shah Rukh relocated the Timurid capital to Herat.[4] In this capacity, he managed the eastern frontiers of the empire, contributing to its stability by overseeing local defenses against nomadic threats, including early incursions by Uzbek forces under leaders like Berek Khan, though Shah Rukh directed the broader military responses.[12] Unlike predecessors focused on perpetual expansion, Ulugh Beg emphasized internal consolidation, channeling resources from Timur's prior conquests—estimated to include vast treasuries of gold, silver, and tribute—into enduring administrative and cultural frameworks rather than funding endless frontier wars.[4] Under his governance, Samarkand emerged as a refuge for intellectuals displaced by regional turmoil following Timur's death in 1405, which had unleashed succession struggles and instability across Central Asia and Persia.[13] Ulugh Beg actively recruited prominent scholars, such as Qadi Zada al-Rumi, who arrived around 1420 after teaching in Bursa and other centers, and Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid al-Kashi from Isfahan, fostering an environment that drew approximately sixty to seventy experts in mathematics, astronomy, and related fields to his court.[14][4] This patronage not only bolstered imperial intellectual capital but also aligned with a pragmatic approach to sustaining Timurid legitimacy through knowledge production, contrasting with the militaristic priorities of rival dynasties like the Qara Qoyunlu.[15]Ascension Following Shah Rukh's Death

Shah Rukh died on 13 March 1447 during a military campaign near Rayy in southern Khurasan, aged 69. As the longstanding governor of Mawarannahr from Samarkand, Ulugh Beg learned of the event while in Balkh and immediately positioned himself as the primary successor, leveraging his established authority in the eastern Timurid domains.[16] He was proclaimed Timurid ruler in Samarkand shortly thereafter, facing no major coordinated resistance in the core Transoxianan territories at the outset. Ulugh Beg moved decisively to consolidate control over Mawarannahr, dispatching forces to neutralize minor rival claimants among Timurid princes who sought local advantages amid the power vacuum.[17] These efforts succeeded rapidly, securing loyalty from key regional amirs and urban centers without prolonged conflict, in contrast to the fragmentation in western provinces like Herat where other relatives vied for influence. This swift stabilization reflected Ulugh Beg's administrative experience and the deference accorded to him as Shah Rukh's eldest surviving son in the east. The unchallenged nature of his initial rule in Transoxiana permitted continuity in scholarly activities, including ongoing refinements to astronomical data at the Samarkand observatory established under his patronage years earlier.[1] Observations and tabular compilations, central to his Zij-i Sultani, proceeded amid this transitional calm, underscoring the prioritization of intellectual endeavors over immediate political turmoil in his domains.[16]Governance

Administrative Structure

Ulugh Beg's administration in Transoxiana centered on a bureaucratic framework inherited from Timurid precedents, particularly those refined under Shah Rukh, emphasizing centralized control through specialized divans to ensure efficient governance over a vast territory spanning modern Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and parts of Kazakhstan. Key institutions included the Diwan-i A'la, overseeing general chancery and fiscal matters; the Diwan-i Arz, managing military registers and payroll; and auxiliary bodies like the Chagatai court (Tavachi) for tribal oversight and the Yarqo court for judicial appeals, blending Persianate organizational models with Timurid adaptations for local Turkic-Mongol integration.[18][19] This structure facilitated stability from 1409 onward, when Ulugh Beg assumed governorship of the region at age 15, by delegating routine operations to appointed officials while retaining ultimate authority in Samarkand. Appointments to high offices, such as viziers and divan heads, prioritized competence through rigorous evaluations, a practice that contrasted with the nepotism and factionalism marking earlier Timurid successions and contributed to Ulugh Beg's relatively stable 40-year rule in Transoxiana.[20] This merit-oriented approach extended to administrative roles beyond the royal family, drawing on Persian bureaucratic traditions while curbing dynastic infighting by favoring capable administrators capable of maintaining order amid nomadic and settled populations.[20] The legal system under Ulugh Beg enforced Sharia for civil, criminal, and religious disputes via qadi courts, supplemented by Mongol Yasa codes for customary tribal matters, reflecting a pragmatic synthesis that upheld social cohesion without suppressing cultural pluralism or scholarly endeavors.[21] This dual framework, rooted in Timur's policies which Ulugh Beg emulated, balanced Islamic legal primacy with residual nomadic enforcement mechanisms, enabling effective rule over diverse subjects while avoiding the rigid uniformity that could provoke unrest.[21]Economic and Fiscal Policies

Ulugh Beg's economic policies emphasized stability and trade facilitation to support the Timurid realm's prosperity, drawing revenues primarily from Silk Road commerce and agricultural output in controlled territories. As ruler of Mawarannahr, including the fertile Fergana Valley, he leveraged agricultural taxes and transit duties on caravan routes connecting China, India, and the West, which generated substantial funds for state initiatives such as the construction of the madrasa in 1417 and the observatory completed in 1420. These revenues, derived from grain surpluses and silk, spice, and textile trades, contrasted with the conquest-driven exploitation under Timur, enabling sustained investment in intellectual infrastructure without heavy reliance on military plunder. Fiscal measures under Ulugh Beg included monetary reforms initiated around 1428, which standardized coin weights and compositions to bolster economic activities and trade expansion. Copper coins were adjusted to a lower weight standard—approximately two-thirds of prior issues—while silver tankas maintained consistency, reducing debasement risks and facilitating commerce with partners like India and China.[22] [23] These reforms promoted domestic and foreign exchange by enhancing currency reliability, differing from the variable standards in earlier post-Mongol systems, and supported low-inflation stability that encouraged merchant activity along key routes. Infrastructure investments focused on urban enhancements in Samarkand, including maintenance of irrigation systems inherited from Timurid predecessors, which sustained agricultural productivity and indirectly funded scientific patronage through increased tax yields. While specific aqueduct projects attributable to Ulugh Beg are sparsely documented, his administration's emphasis on regional stability yielded verifiable long-term gains in output, as evidenced by the era's expanded trade volumes recorded in contemporary accounts. Overall, these policies prioritized pragmatic resource allocation over aggressive extraction, fostering an environment where fiscal prudence underpinned cultural and scientific advancements.[22]Military Affairs and Foreign Relations

Ulugh Beg conducted limited military campaigns primarily aimed at securing the eastern and northern borders of his realm rather than pursuing expansive conquests characteristic of his grandfather Timur. In 1425, he led an expedition into Moghulistan to counter the rising power of Shir Muhammad, who had consolidated control and posed a threat to Timurid frontiers, successfully pushing back incursions from this Chagatai remnant state that included elements allied with Oirat groups.[24] Similar defensive actions addressed Uzbek nomadic pressures, focusing on containment rather than subjugation, as sustained offensives against these mobile steppe forces proved logistically challenging without broader mobilization. The Timurid military under Ulugh Beg relied heavily on tribal levies mobilized for specific threats, rather than maintaining a robust professional standing army, a shift from Timur's earlier centralization efforts that integrated diverse units into a more disciplined force. This dependence on ad hoc recruitments from nomadic confederations, including Turkic and Mongol tribes, sufficed for border skirmishes but lacked the cohesion for prolonged engagements, exposing structural weaknesses when faced with coordinated internal dissent or external raids. Historians attribute this underinvestment in permanent forces to Ulugh Beg's prioritization of scholarly and administrative pursuits, which causally undermined military readiness and facilitated vulnerabilities to opportunistic steppe incursions.[25] In foreign relations, Ulugh Beg sustained diplomatic exchanges with the Ming dynasty, exchanging over twenty embassies during the reigns of Shah Rukh and himself, fostering trade in prized Central Asian horses for Chinese silks and porcelain while avoiding direct conflict. Relations with remnants of the Golden Horde involved attempted alliances through steppe diplomacy, but tensions arose with figures like Baraq Khan, leading to border frictions resolved via tribute arrangements and nominal pacts rather than decisive military dominance. These efforts emphasized stability through economic interdependence over aggression, contrasting Timur's confrontational posture and preserving a fragile peace amid nomadic volatility.Scientific Patronage and Contributions

Establishment of Madrasa and Observatory

Ulugh Beg oversaw the completion of the Ulugh Beg Madrasa in Samarkand in 1420, establishing it as a multifunctional academy dedicated to advanced studies in theology, mathematics, astronomy, and related disciplines.[4] Construction of the madrasa, initiated in 1417, positioned it as a central hub for intellectual pursuits within the Timurid realm, accommodating lectures and scholarly discourse.[1] Concurrent with the madrasa, Ulugh Beg directed the construction of an observatory on a hill outside Samarkand, beginning in 1420 and concluding by 1424, which incorporated advanced instrumentation for celestial observations.[7] The facility's centerpiece was a massive meridian sextant with a radius of approximately 40 meters, embedded in a trench aligned with the north-south meridian to enable precise angular measurements of celestial bodies.[26] This instrument, constructed from marble and iron, represented a scale of engineering unmatched in prior Islamic observatories and surpassed contemporary European efforts in precision tooling.[26] [7] To staff these institutions, Ulugh Beg recruited astronomers and mathematicians from across the Islamicate world, including regions in present-day Iran and Turkey, forming a collaborative cadre that operated under structured oversight.[1] This international assembly created an environment of shared empirical inquiry, distinct from isolated scholarly traditions elsewhere in Asia or Europe during the early 15th century.[1] The madrasa and observatory were sustained through Ulugh Beg's patronage, including endowments such as a charitable allocation of 30,000 dinars, with portions dedicated to stipends for students and faculty, reflecting a state commitment to scientific infrastructure comparable to defenses or public works.[1] [7]

Astronomical Works and Observations

Ulugh Beg's primary astronomical contribution was the Zij-i Sultani, completed in 1437, which included a comprehensive star catalog listing positions for 1,018 stars across 48 constellations.[27] This catalog surpassed the accuracy of Ptolemy's Almagest by incorporating direct naked-eye observations refined through systematic measurement, achieving positional errors typically within 1 to 2 arcminutes when compared to modern values.[28] The work emphasized empirical verification over inherited Hellenistic and earlier Islamic tables, with coordinates given in ecliptic longitude and latitude relative to the equinox of 1430 CE.[29] Key observational results from the Samarkand observatory included a determination of the sidereal year length as 365 days, 6 hours, 10 minutes, and 8 seconds, deviating from the modern value by only about 58 seconds.[4] Ulugh Beg's team also measured the obliquity of the ecliptic at 23° 30' 17", an improvement over prior estimates and accurate to within roughly 32 arcseconds of contemporaneous astronomical reality.[30] These refinements stemmed from prolonged meridian transit observations using large fixed instruments, such as the mural quadrant and sextant, which anchored sightings to permanent architectural references to reduce parallax and instrumental errors.[6] The methodological rigor involved nightly naked-eye sightings calibrated against these immobile tools, amassing data over decades to average out atmospheric distortions and observer variability, yielding outputs that remained authoritative until Tycho Brahe's telescopic era.[7] Such practices privileged direct celestial measurement, enabling cross-verification with later epochs where precession adjustments confirm the catalog's foundational precision.[1]Mathematical Advancements

Ulugh Beg contributed to trigonometry through the compilation of detailed tables for sines and tangents, calculated at intervals of 1° from 0° to 90° in his Zij-i Sultani (completed around 1440), with values accurate to the equivalent of at least eight decimal places, as demonstrated by his computation of sin 1° ≈ 0.01745240643.[4] These tables incorporated interpolation methods to derive intermediate values efficiently, supplemented by verification via multiple independent recalculations to minimize errors inherent in manual computation.[31] Such rigorous computational protocols ensured the tables' reliability for deriving angular measurements in astronomical models. In spherical trigonometry, Ulugh Beg provided refined formulae applicable to celestial sphere problems, enabling more accurate solutions for spherical triangles used in determining positions on the celestial dome.[4] These advancements built upon foundational work by predecessors like al-Battani, who had introduced key identities for sines in spherical contexts, but Ulugh Beg elevated precision by integrating empirical adjustments derived from systematic observations at his Samarkand observatory rather than solely relying on inherited parameters.[32] This data-driven refinement established a direct causal pathway from observed discrepancies to corrected trigonometric constants, thereby enhancing the predictive fidelity of planetary and stellar ephemerides over purely theoretical inheritances from antiquity.Collaboration with Scholars

Ulugh Beg maintained close collaborative relationships with leading astronomers, actively participating in their work rather than delegating solely as a patron. He invited the mathematician and astronomer Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid al-Kashi to Samarkand around 1420, where they jointly advanced trigonometric computations; al-Kashi provided a highly precise value for sin 1°, which Ulugh Beg utilized to construct extensive tables of sines and tangents for every minute of arc, accurate to five sexagesimal places.[4][33] This partnership, which lasted until al-Kashi's death in 1429, emphasized empirical refinement over inherited authorities like Ptolemy.[14] Similarly, Ulugh Beg worked directly with Qadi Zada al-Rumi, appointing him as the principal instructor at the Samarkand madrasa and commissioning commentaries on key mathematical and astronomical texts tailored to his specifications.[34] Qadi Zada contributed to observational programs under Ulugh Beg's supervision, including systematic star position measurements that prioritized repeated verifications to minimize errors, as evidenced by discrepancies identified against earlier catalogs.[14] Ulugh Beg personally oversaw these sessions, lecturing on astronomy and ensuring computations aligned with direct sightings, fostering an environment where claims required empirical substantiation.[35] The results of these collaborations were disseminated through manuscripts of the Zij-i Sultani, completed around 1440, which circulated widely in the Islamic world and later influenced European astronomers via translations and adaptations, such as those impacting Tycho Brahe's work.[1][36] This table-based catalog, with over 1,000 star entries refined through group observations, underscored Ulugh Beg's insistence on collective scrutiny, enabling its adoption in subsequent Persian, Ottoman, and Western tables until the 17th century.[7][37]Personal Life

Marriages and Family Dynamics

Ulugh Beg contracted multiple marriages typical of Timurid rulers, aimed at consolidating dynastic and tribal alliances through kinship ties. At the age of ten, he wed his cousin Agha Bīkī (also known as Aka Begi), whose maternal lineage descended directly from Chinggis Khan, thereby bolstering the Timurid claim to Genghisid legitimacy amid the empire's fractious nomadic confederations.[3] Subsequent unions with noblewomen, such as Roqyā Ḵātūn Arolat, further intertwined the ruling family with influential lineages, facilitating political stability by binding potential rivals and tribal factions through matrimonial networks.[38] These marriages yielded several sons, including the eldest, ʿAbd-al-Laṭīf Mīrzā (born c. 1420), who was raised primarily at the court of his grandfather Shāhroḵ in Herat rather than under Ulugh Beg's direct oversight in Samarkand.[38] Other documented offspring included figures like ʿAbdallāh and Muḥammad, though records of their precise birth dates and maternal lines remain sparse in primary Timurid chronicles. Paternal relations grew strained as sons pursued independent power bases, reflecting the inherent volatility of Timurid succession where fraternal and filial ambitions often undermined centralized authority, exacerbating familial rifts that mirrored broader imperial fragmentation. Posthumously, Ulugh Beg's descendants exerted limited influence, with the dynasty splintering into rival branches; for instance, ʿAbd-al-Laṭīf's brief rule ended in his own assassination in 1450, and subsequent lines faded amid internecine conflicts, curtailing any sustained familial legacy in governance.[38] This pattern underscored how Ulugh Beg's marital strategies, while initially stabilizing tribal loyalties, failed to avert the centrifugal forces of princely entitlement within the Timurid house.Religious Outlook and Intellectual Pursuits

Ulugh Beg followed the Hanafi school of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence, the prevailing madhhab among Timurids in Central Asia, which emphasized rational interpretation (ijtihad) within Sharia alongside textual sources. His personal devotion was evident in his complete memorization of the Quran, including its classical commentaries (tafsir) and associated citations, underscoring a commitment to Islamic scholarship that coexisted with his scientific endeavors.[3] This depth of religious knowledge aligned with the Timurid tradition of blending piety and patronage, yet Ulugh Beg's approach diverged from rigid literalism by favoring observable phenomena as a means to understand divine creation, as demonstrated in his astronomical tables derived from direct measurements rather than solely inherited Ptolemaic models.[4] In patronage, Ulugh Beg supported ulema (religious scholars) through institutions like the Samarkand madrasa, where theology and jurisprudence were taught, while simultaneously advancing empirical sciences such as mathematics and astronomy in the same curriculum—a departure from madrasas focused exclusively on religious dogma.[30] This dual sponsorship refuted claims of inevitable tension between Islam and rationalism, as he assembled diverse scholars without subordinating observation to unverified tradition; records indicate no broad suppression of conservatives, though he maintained order by curbing disruptions to intellectual harmony, prioritizing causal evidence from nature over dogmatic assertions.[6] His restraint in religious enforcement, evident in the absence of major purges, allowed for a synthesis where Quranic contemplation informed but did not constrain scientific progress. Ulugh Beg's own literary output, including poetry and historical compositions, embodied this realist orientation, portraying history and the cosmos through lenses of verifiable patterns and human agency rather than mystical fatalism.[4] These works, composed in Persian, reflected a worldview that valued empirical causation—such as celestial mechanics—as revelations of God's order, bridging devotional verse with analytical prose and countering narratives of faith-science antagonism in medieval Islamic contexts.[39]Downfall and Death

War of Succession

In early 1449, tensions between Ulugh Beg and his eldest son Abd al-Latif, governor of Balkh, escalated due to Ulugh Beg's neglectful administration and financial interference in his son's domain, including disputes over custom duties that strained their relations amid ongoing regional instability from rival Timurid princes and nomadic incursions.[38] Abd al-Latif capitalized on this opportunistically, raising a rebellion in spring 1449 by abolishing disputed taxes to rally support and assembling an army that confronted Ulugh Beg's forces near the Oxus River, exploiting his father's weakened military preparedness stemming from prolonged focus on scholarly pursuits over defense.[38] Ulugh Beg, facing desertions in his ranks and unrest in Samarkand exacerbated by external pressures such as Uzbek raids and prior revolts by figures like ʿAlāʾ-al-dawla, marched southward with insufficient troops to suppress the uprising, retreating after initial setbacks.[38] By September or October 1449, the armies clashed again near Dimashq outside Samarkand, where Ulugh Beg's position deteriorated further, prompting a temporary submission in a bid for reconciliation; however, mutual distrust—fueled by Abd al-Latif's grievances over inadequate paternal support and Ulugh Beg's perceived humiliations—rendered these efforts futile, solidifying the rift.[38]Assassination and Its Immediate Consequences

Ulugh Beg suffered a decisive military defeat against his son ʿAbd al-Laṭīf near Samarkand in late 1449, following a rebellion sparked by the son's ambitions and Ulugh Beg's perceived neglect of governance amid scientific pursuits. After surrendering and being denied refuge in local strongholds, Ulugh Beg submitted to ʿAbd al-Laṭīf, who ostensibly granted him permission to perform the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca as a means of exile. However, ʿAbd al-Laṭīf dispatched agents who assassinated Ulugh Beg en route on October 27, 1449 (10 Ramaḍān 853 AH), effectively eliminating him through a judicial fatwa and execution to consolidate power.[40][41] ʿAbd al-Laṭīf promptly seized control of Samarkand, executing his own brother ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz within days to preempt rival claims, an act widely condemned in contemporary Timurid chronicles for its fratricidal brutality. His rule, spanning from October 1449 to May 1450, was marked by efforts to suppress opposition but alienated key amirs and clan leaders through arbitrary purges and failure to stabilize the realm. Scientific institutions under Ulugh Beg's patronage, including the Samarkand observatory and madrasa, ceased operations abruptly as funding and scholarly continuity evaporated amid the regime's insecurity.[38][40] The instability intensified when ʿAbd al-Laṭīf was himself murdered on May 8, 1450 (26 Rabīʿ I 854 AH), in a conspiracy orchestrated by Samarkand notables and Ulugh Beg's surviving loyalists, who viewed his parricide as a catalyst for dynastic erosion. This swift reversal installed ʿAbdullāh Mīrzā as interim ruler but underscored Ulugh Beg's empirical shortcomings in succession planning, as the lack of a robust administrative framework allowed personal ambitions to fracture Timurid cohesion in Transoxiana, paving the way for intensified rivalries among collateral branches.[38][40]Legacy

Political and Dynastic Impact

Ulugh Beg's brief tenure as Timurid ruler from March 1447 to October 1449 marked a critical juncture in the dynasty's decline, as his administrative capabilities in maintaining order within Transoxiana failed to offset the empire's growing centrifugal forces. While Shah Rukh had preserved relative cohesion across the Timurid domains through persistent military expeditions and suppression of rebellious kin since consolidating power by 1407, Ulugh Beg's governance emphasized scholarly patronage over martial preparedness, resulting in inadequate investment in loyal military successors and vulnerability to internal challenges.[4][42] This deprioritization exacerbated dynastic rivalries, as peripheral Timurid princes exploited the central administration's neglect of frontier defenses and heir grooming, leading to rapid splintering into autonomous khanates following his overthrow. Contemporary accounts, including those from Timurid historians, highlight how Ulugh Beg's inattentiveness to military hierarchies allowed figures like his son Abd al-Latif to seize power violently, creating an immediate power vacuum that fragmented authority in key regions such as Khorasan and Fars.[4][43] The ensuing instability eroded Timurid legitimacy, accelerating the empire's partition into competing polities by the early 1450s and facilitating external incursions, most notably the Uzbek Shaybanid conquests under Muhammad Shaybani, who captured Samarkand in 1501 and subdued remaining Timurid fragments in Transoxiana by 1507. Ulugh Beg's rule thus stands as a pivot where administrative strengths yielded to structural weaknesses in dynastic militarism, hastening the transition from imperial unity to localized rule.[43][42]Enduring Scientific Influence

![Miniature from Ulugh Beg's Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib al-ṯābita]float-right The Zij-i Sultani, Ulugh Beg's comprehensive astronomical handbook completed around 1437, exerted influence through its detailed star catalog and planetary tables, which Ottoman astronomer Taqi al-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf referenced and sought to revise in his own Zij during the late 16th century, conducting observations from 1573 to 1580 to update Ulugh Beg's data with instruments like a large wooden astrolabe and mural quadrant.[44] Taqi al-Din's efforts built directly on the empirical foundation of Ulugh Beg's measurements, incorporating corrections while preserving the original's structure for timekeeping and astrological computations in the Ottoman Empire.[45] Transmission of the Zij-i Sultani to Europe occurred via Latin, French, and English translations by the 17th century, where its star positions—accurate to within about one degree for many entries—served as a primary reference for astronomers lacking comparable observational data until the widespread adoption of telescopic observations.[7] These tables indirectly informed pre-telescopic efforts, including those of Tycho Brahe, whose Uraniborg observatory echoed Ulugh Beg's Samarkand setup in scale and precision goals, though direct textual linkage remains through shared Islamic astronomical traditions disseminated via Ottoman intermediaries like Ali Qushji, who bridged Timurid and Ottoman scholarship after fleeing Samarkand post-1449.[46] Ulugh Beg's trigonometric tables, featuring sine and tangent values computed to at least eight decimal places, demonstrated superior precision over Ptolemaic and contemporaneous European compilations, enabling more reliable spherical calculations essential for navigation, surveying, and calendar adjustments in pre-modern contexts.[32] These advancements sustained utility in practical astronomy until Johannes Kepler's elliptical models and refined ephemerides in the early 17th century supplanted them with dynamically superior predictions, highlighting the Zij-i Sultani's empirical edge derived from large-scale meridian observations that yielded positional accuracies unmatched in Europe until Brahe's naked-eye work.[1] This cross-cultural persistence underscores a continuum of observational rigor rather than isolated "golden age" peaks followed by decline.[47]Modern Commemoration and Archaeological Insights

![Remains of Ulugh Beg Observatory][float-right]The ruins of Ulugh Beg's observatory in Samarkand were excavated in 1908 by Russian archaeologist Vassily Vyatkin, who uncovered the subterranean remnants of the Fakhri sextant and other structures buried since the site's destruction in 1449.[48][32] These findings confirmed the observatory's scale, including a sextant with a 63-meter radius designed for meridian observations, enabling positional accuracies rivaling or exceeding those of Ptolemaic tables. Recent studies, including analyses of the sextant's arc divisions—where 70.2 cm intervals represented one degree—reaffirm its instrumental precision, attributing superior star catalog entries in the Zij-i Sultani to this engineering.[7][32] Modern commemorations include the lunar crater Ulugh Beigh, named in 1830 by Johann Heinrich von Mädler and officially recognized by the International Astronomical Union for its location near Oceanus Procellarum.[49] Asteroid 2439 Ulugbek, a main-belt object discovered on August 21, 1977, by Nikolai Chernykh, was designated in Ulugh Beg's honor.[48] The observatory contributes to Samarkand's UNESCO World Heritage status as "Crossroads of Cultures," inscribed in 2001 for its role in synthesizing Persian, Islamic, and Timurid scientific traditions.[26] Archaeological validations counter myths of post-Timurid scientific stagnation, as data from the Zij-i Sultani's 1018 star positions informed astronomical practices in Mughal India and Safavid Persia, where tables were adapted for almanacs and instruments without substantial degradation until European imports.[50][51] This continuity is evidenced by Safavid astrologers' reliance on the Zij for calendrical computations and Mughal observatories' precession corrections derived from Ulugh Beg's data.[51][52] ![Ulugh Beigh lunar crater][center]