Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Archipelago

View on Wikipedia

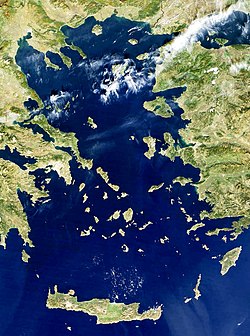

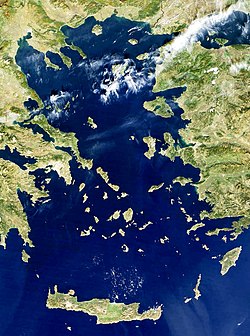

An archipelago (/ˌɑːrkəˈpɛləɡoʊ/ ⓘ AR-kə-PEL-ə-goh),[1] sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Examples of archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the origin of the term), the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, the Stockholm Archipelago, the Malay Archipelago (which includes the Indonesian and Philippine Archipelagos), the Lucayan (Bahamian) Archipelago, the Japanese archipelago, and the Hawaiian Archipelago.

Etymology

[edit]The word archipelago is derived from the Italian arcipelago, used as a proper name for the Aegean Sea, itself perhaps a deformation of the Greek Αιγαίον Πέλαγος.[2][3] Later, usage shifted to refer to the Aegean Islands (since the sea has a large number of islands). The erudite paretymology, deriving the word from Ancient Greek ἄρχι- (arkhi-, "chief") and πέλαγος (pélagos, "sea"), proposed by Buondelmonti, can still be found.[4]

Geographic types

[edit]Archipelagos may be found isolated in large amounts of water or neighboring a large land mass. For example, Scotland has more than 700 islands surrounding its mainland, which form an archipelago.

Depending on their geological origin, islands forming archipelagos can be referred to as oceanic islands, continental fragments, or continental islands.[5]

Oceanic islands

[edit]Oceanic islands are formed by volcanoes erupting from the ocean floor. The Hawaiian Islands and Galapagos Islands in the Pacific, and Mascarene Islands in the south Indian Ocean are examples.

Continental fragments

[edit]Continental fragments are islands that were once part of a continent, and became separated due to natural disasters. The fragments may also be formed by moving glaciers which cut out land, which then fills with water. The Farallon Islands off the coast of California are examples of continental islands.

Continental Islands

[edit]

Continental islands are islands that were once part of a continent and still sit on the continental shelf, which is the edge of a continent that lies under the ocean. The islands of the Inside Passage off the coast of British Columbia and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago are examples.

Artificial archipelagos

[edit]Artificial archipelagos have been created in various countries for different purposes. Palm Islands and The World Islands in Dubai were or are being created for leisure and tourism purposes.[6][7] Marker Wadden in the Netherlands is being built as a conservation area for birds and other wildlife.[8]

Superlatives

[edit]The largest archipelago in the world by number of islands is the Archipelago Sea, which is part of Finland. There are approximately 40,000 islands, mostly uninhabited.[9]

The largest archipelagic state in the world by area, and by population, is Indonesia.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "archipelago". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "archipelago". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. "archipelago (n.), Etymology", July 2023, [1]

- ^ Maltézou, Chryssa A., De la mer Égée à l'archipel: quelques remarques sur l'histoire insulaire égéenne In: Mélanges Hélène Ahrweiler Pt. 2 (1998) p. 464–465

- ^ Whittaker R. J. & Fernández-Palacios J. M. (2007) Island Biogeography: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation. New York, Oxford University Press

- ^ McFadden, Christopher (22 December 2019). "7+ Amazing Facts About Dubai's Palm Islands". Interesting Engineering. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Wainwright, Oliver (13 February 2018). "Not the end of The World: the return of Dubai's ultimate folly". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Boffey, Daniel (27 April 2019). "Marker Wadden, the manmade Dutch archipelago where wild birds reign supreme". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ "Nautical chart: International no. 1205, SE61, Baltic Sea, North, Sea of Åland" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ "Indonesia". The World Factbook (2025 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 7 December 2008. (Archived 2008 edition.)

External links

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- 30 Most Incredible Island Archipelagos

Archipelago

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Etymology

Definition

An archipelago is defined as a group of islands closely clustered or scattered within a body of water, such as an ocean, sea, lake, or river, where the islands are typically separated by narrow straits, channels, or other waterways.[3][1] This configuration distinguishes it from isolated single islands, which lack such grouping, or peninsulas, which remain connected to a mainland.[11] Key characteristics of an archipelago include the presence of numerous islands—generally at least several—that exhibit spatial proximity and geographical association, rather than random dispersion across vast distances.[3] These islands are often linked by shared oceanographic or environmental contexts, forming a cohesive unit within the surrounding water body.[1] In contrast to linear island chains, which align in elongated sequences often following tectonic ridges, archipelagos emphasize clustered or irregular groupings.[12] Atolls represent a type of coral island consisting of ring-shaped reefs encircling a central lagoon, which may form part of an archipelago.[13] Historically, the term "archipelago" began as a descriptive toponym for island-rich seas and has evolved into a formal geographical classification in physical geography and the social sciences, enabling systematic analysis of island distributions and their spatial dynamics.[14] This progression reflects its adaptation from a nautical reference to a precise concept in physical geography, aiding in the delineation of marine landforms.[15]Etymology

The term "archipelago" derives from the Italian arcipelago, which emerged in the 13th century as a proper name for the Aegean Sea, literally translating to "chief sea" or "principal sea."[16] This Italian form combines arci- (from Latin archi-, meaning "chief" or "principal") with pelago (from Medieval Latin pelagus, borrowed from Ancient Greek pelagos, denoting "sea," "gulf," or "abyss").[11] The Greek pelagos underscores the maritime connotation, appearing in related terms like "pelagic," which refers to open ocean environments.[17] Coined during the Middle Ages, likely by Venetian or Italian mariners familiar with the Aegean region's dense cluster of islands, the word initially described that specific body of water and its island chains, reflecting its status as a vital navigational hub in the Mediterranean.[16] It may represent an Italian adaptation or compound alteration of the Medieval Latin Egeopelagus, itself drawn from Greek Aigaion pelagos ("Aegean Sea").[16] The term entered English in the 16th century, with the earliest recorded uses around 1598, often in translations of ancient and medieval texts that highlighted the Aegean's island-dotted expanse.[11] Over time, the meaning underwent a semantic shift from this specific regional reference to a general designation for any group of islands scattered in a body of water, driven by the broader European Age of Exploration.[16] By around 1600, Italian usage had already extended arcipelago to describe any "sea studded with islands" and the islands themselves, a pattern that English adopted as explorers documented similar formations worldwide.[16] This evolution is evident in archaic literature and early navigation charts, where the term transitioned from denoting the Aegean alone to symbolizing island clusters encountered in distant seas, enriching its cultural resonance in cartography and travel accounts.[11]Geological Formation

Tectonic Origins

Archipelagos arise primarily from the interactions of tectonic plates driven by mantle convection, a process central to plate tectonics theory that explains the movement of Earth's lithospheric plates over the asthenosphere. These movements, occurring at rates of a few centimeters per year, lead to the fragmentation and reassembly of continental and oceanic crust, resulting in clusters of islands separated by water. Continental drift, integral to this framework, has historically separated large landmasses, isolating fragments that evolve into archipelagic configurations over geological timescales.[18] Subduction zones at convergent plate boundaries play a pivotal role in archipelago formation, where denser oceanic lithosphere descends beneath less dense continental or oceanic plates, reaching depths of up to 700 kilometers. The subducting plate undergoes partial melting due to elevated temperatures and pressures, producing magma that ascends through the overriding plate to form volcanic island arcs—typically curved chains of islands positioned about 100 kilometers above the Benioff zone of seismicity. This process exemplifies structural geology in action, as the arcs parallel the trench formed by subduction and contribute to the accretion of new crustal material.[18][19][20] Divergent plate boundaries, where plates pull apart, facilitate archipelago development by generating new crust through upwelling mantle material along rift zones, often at mid-ocean ridges. In continental rifts, extensional forces thin the lithosphere, creating fault-controlled basins that can subside and flood to form island-dotted seascapes if marine transgression occurs. These rift-related structures highlight the extensional tectonics that contrast with the compressional regimes of subduction.[18][21] The fragmentation of supercontinents like Gondwana, which began around 180 million years ago during the Early Jurassic, produced numerous continental fragments and microplates through rifting along zones of weakness in the crust. These detached blocks, often bounded by transform faults, drifted independently to become isolated landmasses encircled by expanding ocean basins, directly contributing to the origin of continental archipelagos. Estimates suggest over 90 such fragments originated from Gondwana, underscoring the scale of this tectonic disassembly.[22][23][24] Archipelago formation unfolds over millions of years, with many contemporary examples tracing their tectonic foundations to the Cenozoic era, which commenced 66 million years ago following the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event. This era witnessed accelerated plate convergence and rifting, including the ongoing subduction around the Pacific Ring of Fire and the continued dispersal of Gondwanan remnants, shaping the structural framework of island groups through episodic deformation.[25][26] Tectonically active archipelagos are characterized by extensive fault lines, such as strike-slip and thrust faults, that accommodate plate motions and trigger frequent earthquakes, often exceeding magnitude 7 due to stress accumulation along boundaries. Orogeny, or mountain-building, accompanies these dynamics, particularly in subduction settings, where compressive forces uplift fold-thrust belts and volcanic edifices within the island clusters, enhancing topographic diversity.[27][28]Volcanic and Erosional Processes

Volcanic activity plays a pivotal role in the formation and evolution of many archipelagos, particularly through hotspot volcanism driven by mantle plumes. These plumes are buoyant columns of hot mantle material rising from deep within the Earth, piercing the overlying tectonic plates to generate magma that erupts and builds volcanic islands. As the plate moves over the stationary plume, a linear chain of islands emerges, with the youngest and most active at the hotspot and older islands trailing behind. The Hawaiian archipelago exemplifies this process, where the Pacific Plate's northwestward motion over a mantle plume has produced a chain spanning over 2,400 kilometers, with islands forming sequentially over tens of millions of years.[29][30][31] In subduction zones, where one tectonic plate slides beneath another, archipelagos often develop as chains of stratovolcanoes due to the partial melting of the subducting plate, which generates viscous, silica-rich magmas that erupt explosively. These stratovolcanoes form steep-sided cones built from layers of lava flows, ash, and pyroclastic material, creating island arcs parallel to the subduction trench. The Aleutian Islands in Alaska represent a classic example, arising from the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the North American Plate, resulting in a curved chain of over 200 islands characterized by frequent eruptions and seismic activity. Similarly, the Mariana Islands form an arc from subduction-related volcanism in the western Pacific.[32][33][34] Erosional processes complement volcanism by sculpting and isolating islands within archipelagos, often transforming rugged volcanic terrains into fragmented clusters. Wave action relentlessly attacks coastlines, undercutting cliffs and abrading shorelines to create sea stacks, arches, and isolated islands from what were once continuous landmasses. Weathering, including chemical dissolution and physical breakdown, further weakens volcanic rocks, while in glaciated regions, ice carving deepens fjords and separates islands, as seen in archipelagos like the San Juan Islands where glacial erosion has etched depressions and bogs into bedrock. These processes can isolate portions of larger landforms, contributing to the dispersed nature of continental-fringing archipelagos.[35][36] Sediment deposition, driven by erosion, is crucial for forming low-lying islands in coral-based archipelagos, particularly atolls. Waves and currents transport eroded reef fragments and carbonate sediments from surrounding coral platforms, depositing them to build narrow, ring-shaped islands around subsided volcanic foundations. This process relies on the interplay of erosion supplying loose material and deposition stabilizing it above sea level, creating habitable rims on atolls like those in the Pacific. Over time, continued erosion of the inner lagoon and outer reef margins maintains the dynamic equilibrium of these sediment piles.[37][38] The interaction between volcanism and erosion, influenced by tectonic forces, drives cycles of land building and sculpting in archipelagos. Volcanic eruptions rapidly add mass, causing isostatic uplift that elevates islands, while subsequent erosion redistributes material and promotes subsidence through flexural loading of the lithosphere. In hotspot settings, volcanic loading induces initial uplift followed by gradual subsidence as the plume's heat dissipates, allowing erosion to dominate and eventually drown older islands beneath the waves. Subduction-related archipelagos experience similar cycles, where tectonic compression aids uplift, but erosion and subsidence lead to fragmentation. These processes occur on contrasting timescales: volcanic islands can emerge and reach significant elevation in as little as thousands to hundreds of thousands of years through rapid shield-building phases, whereas erosion and subsidence reshape them over millions of years, often culminating in atoll formation after 10-30 million years of subsidence.[39][40][41]Classification by Origin

Oceanic Archipelagos

Oceanic archipelagos consist of island groups that emerge in the open ocean, distant from continental margins, primarily through volcanic processes driven by mantle hotspots or mid-ocean ridge activity. These formations arise when magma from deep within the Earth's mantle rises to the surface, lacking any influence from continental crust, which results in predominantly basaltic rock compositions characteristic of ocean island basalts. Unlike continental archipelagos, oceanic ones develop in isolation over abyssal depths, often forming linear chains as tectonic plates drift over stationary hotspots, with volcanic activity concentrated at the point of upwelling.[42][43][44] A defining feature of oceanic archipelagos is their profound geographical isolation, surrounded by deep ocean waters exceeding several kilometers in depth, which limits species dispersal and fosters high levels of endemism through in situ evolution. Island ages within these archipelagos typically decrease progressively away from the hotspot, reflecting the plate's movement and the episodic nature of volcanism, leading to a conveyor-belt-like sequence where older islands subside and erode while newer ones form. This uniformity in geological origin and age gradient contrasts with the diverse lithologies of continental fragments, promoting simplified biotas adapted to volcanic substrates.[42][43][45] Prominent examples include the Hawaiian Islands, a classic hotspot chain spanning over 6,000 kilometers as part of the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain, where the Pacific Plate's northwestward motion has generated more than 80 volcanoes over 70 million years, with the youngest at the southeastern end. The Galápagos Islands similarly originated from a mantle plume hotspot beneath the Nazca Plate, forming around 20 million years ago through successive volcanic eruptions that built a 3-kilometer-thick platform, resulting in an archipelago of varied island ages and basaltic shield volcanoes. Associated structural features such as seamounts—extinct underwater volcanoes—and guyots, which are flat-topped seamounts eroded during subaerial exposure before subsidence, are integral to these systems; for instance, the Hawaiian chain includes active seamounts like Lōʻihi, poised to emerge as the next island.[43][46][44] Oceanographic processes significantly shape the ecosystems of oceanic archipelagos, as surrounding currents and localized upwelling deliver nutrients that sustain high productivity. In the Galápagos, for example, the cold Humboldt Current and equatorial upwelling driven by the Cromwell Current bring nutrient-rich deep waters to the surface around the islands, fueling phytoplankton blooms that support diverse marine food webs, including fish populations vital to endemic species like penguins and sea lions. These dynamics enhance biodiversity in otherwise nutrient-poor open-ocean settings, though they can vary with climatic events such as El Niño, which temporarily disrupts upwelling.[47][48]Continental Archipelagos

Continental archipelagos consist of groups of islands that originate from the fragmentation of continental landmasses, typically through processes such as the flooding of continental shelves, tectonic rifting, or erosion. These formations are closely associated with adjacent continents, sitting on the continental shelf where sea depths are generally shallow, often less than 200 meters. Subtypes include flooded continental shelves, which result from post-Ice Age sea-level rise that submerged low-lying coastal plains and river valleys, and fragments created by tectonic rifting or prolonged erosion that isolates portions of the mainland.[13][49] A key characteristic of continental archipelagos is their geological diversity, featuring a mix of sedimentary, metamorphic, and sometimes igneous rock types inherited from the parent continent, along with uplifted fault blocks and drowned valleys. Their proximity to the mainland facilitates faunal and floral exchange, leading to biodiversity patterns that blend continental and insular elements, unlike more isolated oceanic systems. Shallower surrounding waters promote sediment deposition and tidal influences, shaping dynamic coastal geomorphology.[13][50] Prominent examples include the Indonesian archipelago, where islands like Sumatra, Java, and Borneo represent fragments of the Sunda Shelf—a vast, partially drowned continental platform exposed during Pleistocene lowstands but submerged by post-glacial sea-level rise around 10,000 years ago. In the Aegean Sea, the islands form through tectonic subsidence in extensional basins, such as the North Aegean Trough, where crustal thinning since the Pliocene has fragmented the continental crust of the Tethyan belt, creating a mosaic of metamorphic cores and sedimentary basins. Northern examples, like the British Isles, illustrate the role of glaciation, with repeated Ice Age advances over the past 500,000 years eroding landscapes and subsequent sea-level rise flooding glacial troughs to form islands with diverse features including U-shaped valleys and ribbon lakes.[49][50][51]Artificial Archipelagos

Artificial archipelagos consist of groups of islands engineered by humans through methods such as land reclamation, dredging, and the use of structural platforms, distinguishing them from naturally formed island clusters.[52] These constructions typically involve pumping sand and rock from seabeds or nearby sources onto shallow reefs or seabeds to create stable landmasses, often shaped using GPS-guided dredgers for precise contours.[53] Alternative techniques include floating platforms made from buoyant materials like concrete caissons or modular structures anchored in place, as well as linking smaller islets with causeways to form cohesive groups.[54] Such engineering allows for the creation of habitable or functional land in marine environments where natural expansion is limited. Historical development of artificial archipelagos traces back centuries, with early examples emerging in coastal and lacustrine settings for defensive and communal purposes. In the Western Pacific, indigenous groups in regions like the Solomon Islands constructed clusters of up to 60 artificial islands on coral reefs using coral rubble, mangrove stakes, and thatched materials as early as the 16th century, forming stable settlements in lagoon environments. Similarly, the Uros people of Lake Titicaca in Peru and Bolivia have maintained floating island groups made from totora reeds for over 1,000 years, periodically renewing the buoyant layers to sustain communities.[55] In Europe, Iron Age crannogs—artificial islands built by piling timber, stone, and earth in Scottish and Irish lochs—created defensive clusters dating to around 800 BCE, often serving as elite retreats.[56] These pre-modern efforts laid foundational techniques for later large-scale projects, though modern advancements in hydraulics and materials accelerated construction during the 20th and 21st centuries, particularly for urban expansion in land-scarce regions.[57] Contemporary artificial archipelagos are primarily built for residential, tourism, and military objectives, exemplifying ambitious geo-engineering in response to population pressures and strategic needs. The Palm Islands off Dubai, initiated in 2001 by developer Nakheel, form a trio of palm-shaped archipelagos—Jumeirah, Jebel Ali, and Deira—using approximately 94 million cubic meters of dredged sand for Palm Jumeirah, contributing to over 5.6 square kilometers of new land for the initial island, with the trio planned to span much larger areas exceeding 50 square kilometers in total to boost the emirate's tourism economy. In the South China Sea, China has engineered an archipelago on seven Spratly reefs since 2013, expanding 3,000 acres through dredging and landfilling to establish military outposts equipped with airstrips, radar, and missile systems, enhancing territorial claims and naval projection.[58] Tourism-focused examples include Dubai's The World, a 300-island cluster mimicking a world map, constructed via seabed dredging to attract high-end developments, while environmental engineering applications, such as mangrove restoration islands in Southeast Asian wetlands, use similar dredging to rehabilitate coastlines against erosion.[59] Despite their utility, artificial archipelagos pose significant engineering and ecological challenges, including subsidence and habitat disruption. Structures like Dubai's Palm Jumeirah experience ongoing subsidence of up to 5 millimeters per year due to soil compaction under heavy loads, necessitating continuous monitoring and reinforcement to prevent flooding.[60] Ecologically, dredging for these projects increases water turbidity, buries marine habitats, and alters sediment flows, as seen in the Palm Islands where coral mortality reached 80% in adjacent areas and wave patterns shifted, reducing beach accretion.[61] In the South China Sea, China's islands have destroyed over 3,000 acres of reefs, exacerbating biodiversity loss and fisheries decline across 295,000 square kilometers of affected waters.[58] These issues highlight the trade-offs in balancing human expansion with marine ecosystem integrity.Notable Examples and Characteristics

Largest and Most Populous

The Malay Archipelago, often regarded as the world's largest by land area, spans approximately 2.5 million square kilometers across Indonesia, the Philippines, parts of Malaysia, Brunei, and eastern Indonesia including western New Guinea, encompassing over 25,000 islands and making it a defining feature of Southeast Asia.[62] This vast expanse includes significant sea coverage, with the land area highlighting its role as both a continental shelf extension and oceanic island group. In contrast, archipelagos like the Canadian Arctic Archipelago cover around 1.42 million square kilometers of land across 36,000 islands, emphasizing remote, ice-influenced terrains.[63] By population, the Malay Archipelago components stand out, with Indonesia alone home to an estimated 285.7 million people as of mid-2025, driven by high densities on islands like Java, where over 150 million reside on just 138,000 square kilometers.[64] Population distribution varies widely, with densely settled continental-type archipelagos contrasting sparse oceanic ones; for instance, the Philippine archipelago supports about 116.8 million across 7,641 islands as of mid-2025, while the Canadian Arctic's islands host fewer than 150,000 due to harsh climates.[65] These demographics reflect human adaptation to island constraints, including limited arable land and reliance on maritime trade. Recent climate impacts, such as sea-level rise, have submerged smaller islets in vulnerable archipelagos, potentially altering island counts and habitability as of 2025.[66] Archipelagos are ranked by excluding isolated single islands or continental landmasses connected by shallow seas, focusing instead on discrete island clusters separated by deeper waters.[3] Rankings can shift due to political boundaries, such as Indonesia's post-colonial unification in 1945 incorporating diverse island groups, or environmental factors like rising sea levels submerging smaller islets and altering counts over millennia.[67]| Rank | Archipelago | Land Area (km²) | Approximate Number of Islands | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Malay | ~2,500,000 | >25,000 | Jagran Josh |

| 2 | Canadian Arctic | 1,424,500 | 36,563 | The Canadian Encyclopedia |

| 3 | Japanese | 364,555 | 6,852 | CIA World Factbook |

| 4 | Philippine | 298,170 | 7,641 | CIA World Factbook |

| 5 | British Isles | 243,610 | ~6,000 | Britannica |

| Rank | Archipelago | Population (mid-2025 est.) | Key Density Factors | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indonesian | 285,700,000 | High urban centers like Jakarta | Worldometer |

| 2 | Japanese | 123,100,000 | Concentrated on Honshu | Worldometer |

| 3 | Philippine | 116,800,000 | Metro Manila and Cebu | Worldometer |

| 4 | British Isles | 74,600,000 | England and Ireland hubs | ONS UK; World Population Review Ireland |

| 5 | New Zealand | 5,250,000 | North and South Islands | Worldometer |