Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Area | |

|---|---|

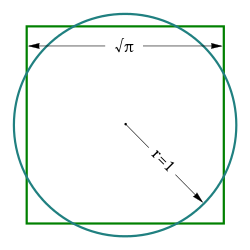

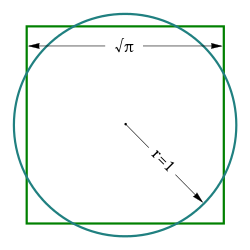

The areas of this square and this disk are the same. | |

Common symbols | A or S |

| SI unit | Square metre [m2] |

| In SI base units | 1 m2 |

| Dimension | |

Area is the measure of a region's size on a surface. The area of a plane region or plane area refers to the area of a shape or planar lamina, while surface area refers to the area of an open surface or the boundary of a three-dimensional object. Area can be understood as the amount of material with a given thickness that would be necessary to fashion a model of the shape, or the amount of paint necessary to cover the surface with a single coat.[1] It is the two-dimensional analogue of the length of a curve (a one-dimensional concept) or the volume of a solid (a three-dimensional concept). Two different regions may have the same area (as in squaring the circle); by synecdoche, "area" sometimes is used to refer to the region, as in a "polygonal area".

The area of a shape can be measured by comparing the shape to squares of a fixed size.[2] In the International System of Units (SI), the standard unit of area is the square metre (written as m2), which is the area of a square whose sides are one metre long.[3] A shape with an area of three square metres would have the same area as three such squares. In mathematics, the unit square is defined to have area one, and the area of any other shape or surface is a dimensionless real number.

There are several well-known formulas for the areas of simple shapes such as triangles, rectangles, and circles. Using these formulas, the area of any polygon can be found by dividing the polygon into triangles.[4] For shapes with curved boundary, calculus is usually required to compute the area. Indeed, the problem of determining the area of plane figures was a major motivation for the historical development of calculus.[5]

For a solid shape such as a sphere, cone, or cylinder, the area of its boundary surface is called the surface area.[1][6][7] Formulas for the surface areas of simple shapes were computed by the ancient Greeks, but computing the surface area of a more complicated shape usually requires multivariable calculus.

Area plays an important role in modern mathematics. In addition to its obvious importance in geometry and calculus, area is related to the definition of determinants in linear algebra, and is a basic property of surfaces in differential geometry.[8] In analysis, the area of a subset of the plane is defined using Lebesgue measure,[9] though not every subset is measurable if one supposes the axiom of choice.[10] In general, area in higher mathematics is seen as a special case of volume for two-dimensional regions.[1]

Area can be defined through the use of axioms, defining it as a function of a collection of certain plane figures to the set of real numbers. It can be proved that such a function exists.

Formal definition

[edit]An approach to defining what is meant by "area" is through axioms. "Area" can be defined as a function from a collection M of a special kinds of plane figures (termed measurable sets) to the set of real numbers, which satisfies the following properties:[11]

- For all S in M, a(S) ≥ 0.

- If S and T are in M then so are S ∪ T and S ∩ T, and also a(S∪T) = a(S) + a(T) − a(S ∩ T).

- If S and T are in M with S ⊆ T then T − S is in M and a(T−S) = a(T) − a(S).

- If a set S is in M and S is congruent to T then T is also in M and a(S) = a(T).

- Every rectangle R is in M. If the rectangle has length h and breadth k then a(R) = hk.

- Let Q be a set enclosed between two step regions S and T. A step region is formed from a finite union of adjacent rectangles resting on a common base, i.e. S ⊆ Q ⊆ T. If there is a unique number c such that a(S) ≤ c ≤ a(T) for all such step regions S and T, then a(Q) = c.

It can be proved that such an area function actually exists.[12]

Units

[edit]

Every unit of length has a corresponding unit of area, namely the area of a square with the given side length. Thus areas can be measured in square metres (m2), square centimetres (cm2), square millimetres (mm2), square kilometres (km2), square feet (ft2), square yards (yd2), square miles (mi2), and so forth.[13] Algebraically, these units can be thought of as the squares of the corresponding length units.

The SI unit of area is the square metre, which is considered an SI derived unit.[3]

Conversions

[edit]

Calculation of the area of a square whose length and width are 1 metre would be:

1 metre × 1 metre = 1 m2

and so, a rectangle with different sides (say length of 3 metres and width of 2 metres) would have an area in square units that can be calculated as:

3 metres × 2 metres = 6 m2. This is equivalent to 6 million square millimetres. Other useful conversions are:

- 1 square kilometre = 1,000,000 square metres

- 1 square metre = 10,000 square centimetres = 1,000,000 square millimetres

- 1 square centimetre = 100 square millimetres.

Non-metric units

[edit]In non-metric units, the conversion between two square units is the square of the conversion between the corresponding length units.

the relationship between square feet and square inches is

- 1 square foot = 144 square inches,

where 144 = 122 = 12 × 12. Similarly:

- 1 square yard = 9 square feet

- 1 square mile = 3,097,600 square yards = 27,878,400 square feet

In addition, conversion factors include:

- 1 square inch = 6.4516 square centimetres

- 1 square foot = 0.09290304 square metres

- 1 square yard = 0.83612736 square metres

- 1 square mile = 2.589988110336 square kilometres

Other units including historical

[edit]There are several other common units for area. The are was the original unit of area in the metric system, with:

- 1 are = 100 square metres

Though the are has fallen out of use, the hectare is still commonly used to measure land:[13]

- 1 hectare = 100 ares = 10,000 square metres = 0.01 square kilometres

Other uncommon metric units of area include the tetrad, the hectad, and the myriad.

The acre is also commonly used to measure land areas, where

- 1 acre = 4,840 square yards = 43,560 square feet.

An acre is approximately 40% of a hectare.

On the atomic scale, area is measured in units of barns, such that:[13]

- 1 barn = 10−28 square meters.

The barn is commonly used in describing the cross-sectional area of interaction in nuclear physics.[13]

In South Asia (mainly Indians), although the countries use SI units as official, many South Asians still use traditional units. Each administrative division has its own area unit, some of them have same names, but with different values. There's no official consensus about the traditional units values. Thus, the conversions between the SI units and the traditional units may have different results, depending on what reference that has been used.[14][15][16][17]

Some traditional South Asian units that have fixed value:

- 1 Killa = 1 acre

- 1 Ghumaon = 1 acre

- 1 Kanal = 0.125 acre (1 acre = 8 kanal)

- 1 Decimal = 48.4 square yards

- 1 Chatak = 180 square feet

History

[edit]Circle area

[edit]In the 5th century BCE, Hippocrates of Chios was the first to show that the area of a disk (the region enclosed by a circle) is proportional to the square of its diameter, as part of his quadrature of the lune of Hippocrates,[18] but did not identify the constant of proportionality. Eudoxus of Cnidus, also in the 5th century BCE, also found that the area of a disk is proportional to its radius squared.[19]

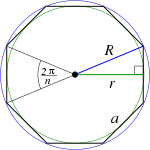

Subsequently, Book I of Euclid's Elements dealt with equality of areas between two-dimensional figures. The mathematician Archimedes used the tools of Euclidean geometry to show that the area inside a circle is equal to that of a right triangle whose base has the length of the circle's circumference and whose height equals the circle's radius, in his book Measurement of a Circle. (The circumference is 2πr, and the area of a triangle is half the base times the height, yielding the area πr2 for the disk.) Archimedes approximated the value of π (and hence the area of a unit-radius circle) with his doubling method, in which he inscribed a regular triangle in a circle and noted its area, then doubled the number of sides to give a regular hexagon, then repeatedly doubled the number of sides as the polygon's area got closer and closer to that of the circle (and did the same with circumscribed polygons).

Triangle area

[edit]Heron of Alexandria found what is known as Heron's formula for the area of a triangle in terms of its sides, and a proof can be found in his book, Metrica, written around 60 CE. It has been suggested that Archimedes knew the formula over two centuries earlier,[20] and since Metrica is a collection of the mathematical knowledge available in the ancient world, it is possible that the formula predates the reference given in that work.[21] In 300 BCE Greek mathematician Euclid proved that the area of a triangle is half that of a parallelogram with the same base and height in his book Elements of Geometry.[22]

In 499 Aryabhata, a great mathematician-astronomer from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy, expressed the area of a triangle as one-half the base times the height in the Aryabhatiya.[23]

A formula equivalent to Heron's was discovered by the Chinese independently of the Greeks. It was published in 1247 in Shushu Jiuzhang ("Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections"), written by Qin Jiushao.[24]Quadrilateral area

[edit]In the 7th century CE, Brahmagupta developed a formula, now known as Brahmagupta's formula, for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral (a quadrilateral inscribed in a circle) in terms of its sides. In 1842, the German mathematicians Carl Anton Bretschneider and Karl Georg Christian von Staudt independently found a formula, known as Bretschneider's formula, for the area of any quadrilateral.

General polygon area

[edit]The development of Cartesian coordinates by René Descartes in the 17th century allowed the development of the surveyor's formula for the area of any polygon with known vertex locations by Gauss in the 19th century.

Areas determined using calculus

[edit]The development of integral calculus in the late 17th century provided tools that could subsequently be used for computing more complicated areas, such as the area of an ellipse and the surface areas of various curved three-dimensional objects.

Area formulas

[edit]Polygon formulas

[edit]For a non-self-intersecting (simple) polygon, the Cartesian coordinates (i=0, 1, ..., n-1) of whose n vertices are known, the area is given by the surveyor's formula:[25]

where when i=n-1, then i+1 is expressed as modulus n and so refers to 0.

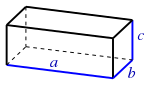

Rectangles

[edit]

The most basic area formula is the formula for the area of a rectangle. Given a rectangle with length l and width w, the formula for the area is:[2]

- A = lw (rectangle).

That is, the area of the rectangle is the length multiplied by the width. As a special case, as l = w in the case of a square, the area of a square with side length s is given by the formula:[1][2]

- A = s2 (square).

The formula for the area of a rectangle follows directly from the basic properties of area, and is sometimes taken as a definition or axiom. On the other hand, if geometry is developed before arithmetic, this formula can be used to define multiplication of real numbers.

Dissection, parallelograms, and triangles

[edit]

Most other simple formulas for area follow from the method of dissection. This involves cutting a shape into pieces, whose areas must sum to the area of the original shape. For an example, any parallelogram can be subdivided into a trapezoid and a right triangle, as shown in figure to the left. If the triangle is moved to the other side of the trapezoid, then the resulting figure is a rectangle. It follows that the area of the parallelogram is the same as the area of the rectangle:[2]

- A = bh (parallelogram).

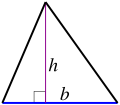

However, the same parallelogram can also be cut along a diagonal into two congruent triangles, as shown in the figure to the right. It follows that the area of each triangle is half the area of the parallelogram:[2]

- (triangle).

Similar arguments can be used to find area formulas for the trapezoid[26] as well as more complicated polygons.[27]

Area of curved shapes

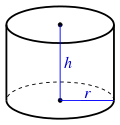

[edit]Circles

[edit]

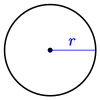

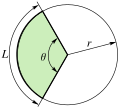

The formula for the area of a circle (more properly called the area enclosed by a circle or the area of a disk) is based on a similar method. Given a circle of radius r, it is possible to partition the circle into sectors, as shown in the figure to the right. Each sector is approximately triangular in shape, and the sectors can be rearranged to form an approximate parallelogram. The height of this parallelogram is r, and the width is half the circumference of the circle, or πr. Thus, the total area of the circle is πr2:[2]

- A = πr2 (circle).

Though the dissection used in this formula is only approximate, the error becomes smaller and smaller as the circle is partitioned into more and more sectors. The limit of the areas of the approximate parallelograms is exactly πr2, which is the area of the circle.[28]

This argument is actually a simple application of the ideas of calculus. In ancient times, the method of exhaustion was used in a similar way to find the area of the circle, and this method is now recognized as a precursor to integral calculus. Using modern methods, the area of a circle can be computed using a definite integral:

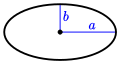

Ellipses

[edit]The formula for the area enclosed by an ellipse is related to the formula of a circle; for an ellipse with semi-major and semi-minor axes x and y the formula is:[2]

Non-planar surface area

[edit]

Most basic formulas for surface area can be obtained by cutting surfaces and flattening them out (see: developable surfaces). For example, if the side surface of a cylinder (or any prism) is cut lengthwise, the surface can be flattened out into a rectangle. Similarly, if a cut is made along the side of a cone, the side surface can be flattened out into a sector of a circle, and the resulting area computed.

The formula for the surface area of a sphere is more difficult to derive: because a sphere has nonzero Gaussian curvature, it cannot be flattened out. The formula for the surface area of a sphere was first obtained by Archimedes in his work On the Sphere and Cylinder. The formula is:[6]

- A = 4πr2 (sphere),

where r is the radius of the sphere. As with the formula for the area of a circle, any derivation of this formula inherently uses methods similar to calculus.

General formulas

[edit]Areas of 2-dimensional figures

[edit]

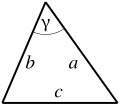

- A triangle: (where B is any side, and h is the distance from the line on which B lies to the other vertex of the triangle). This formula can be used if the height h is known. If the lengths of the three sides are known then Heron's formula can be used: where a, b, c are the sides of the triangle, and is half of its perimeter.[2] If an angle and its two included sides are given, the area is where C is the given angle and a and b are its included sides.[2] If the triangle is graphed on a coordinate plane, a matrix can be used and is simplified to the absolute value of . This formula is also known as the shoelace formula and is an easy way to solve for the area of a coordinate triangle by substituting the 3 points (x1,y1), (x2,y2), and (x3,y3). The shoelace formula can also be used to find the areas of other polygons when their vertices are known. Another approach for a coordinate triangle is to use calculus to find the area.

- A simple polygon constructed on a grid of equal-distanced points (i.e., points with integer coordinates) such that all the polygon's vertices are grid points: , where i is the number of grid points inside the polygon and b is the number of boundary points. This result is known as Pick's theorem.[29]

Area in calculus

[edit]

- The area between a positive-valued curve and the horizontal axis, measured between two values a and b (b is defined as the larger of the two values) on the horizontal axis, is given by the integral from a to b of the function that represents the curve:[1]

- The area between the graphs of two functions is equal to the integral of one function, f(x), minus the integral of the other function, g(x):

- where is the curve with the greater y-value.

- An area bounded by a function expressed in polar coordinates is:[1]

- The area enclosed by a parametric curve with endpoints is given by the line integrals:

- or the z-component of

- (For details, see Green's theorem § Area calculation.) This is the principle of the planimeter mechanical device.

Bounded area between two quadratic functions

[edit]To find the bounded area between two quadratic functions, we first subtract one from the other, writing the difference as where f(x) is the quadratic upper bound and g(x) is the quadratic lower bound. By the area integral formulas above and Vieta's formula, we can obtain that[30][31] The above remains valid if one of the bounding functions is linear instead of quadratic.

Surface area of 3-dimensional figures

[edit]- Cone:[32] , where r is the radius of the circular base, and h is the height. That can also be rewritten as [32] or where r is the radius and l is the slant height of the cone. is the base area while is the lateral surface area of the cone.[32]

- Cube: , where s is the length of an edge.[6]

- Cylinder: , where r is the radius of a base and h is the height. The can also be rewritten as , where d is the diameter.

- Prism: , where B is the area of a base, P is the perimeter of a base, and h is the height of the prism.

- pyramid: , where B is the area of the base, P is the perimeter of the base, and L is the length of the slant.

- Rectangular prism: , where is the length, w is the width, and h is the height.

General formula for surface area

[edit]The general formula for the surface area of the graph of a continuously differentiable function where and is a region in the xy-plane with the smooth boundary:

An even more general formula for the area of the graph of a parametric surface in the vector form where is a continuously differentiable vector function of is:[8]

List of formulas

[edit]| Shape | Formula | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Square |

| |

| Rectangle |

| |

| Triangle |

| |

| Triangle |

| |

| Triangle |

| |

| Isosceles triangle |

| |

| Regular triangle |

| |

| Rhombus/Kite |

| |

| Parallelogram |

| |

| Trapezoid |

| |

| Regular hexagon |

| |

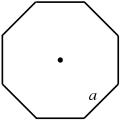

| Regular octagon |

| |

| Regular polygon ( sides) |

|

(perimeter) |

| Circle | ( diameter) |

|

| Circular sector |

| |

| Ellipse |

| |

| Integral |

| |

| Surface area | ||

| Sphere |

| |

| Cuboid |

| |

| Cylinder (incl. bottom and top) |

| |

| Cone (incl. bottom) |

| |

| Torus |

| |

| Surface of revolution | (rotation around the x-axis) |

|

The above calculations show how to find the areas of many common shapes.

The areas of irregular (and thus arbitrary) polygons can be calculated using the "Surveyor's formula" (shoelace formula).[28]

Relation of area to perimeter

[edit]The isoperimetric inequality states that, for a closed curve of length L (so the region it encloses has perimeter L) and for area A of the region that it encloses,

and equality holds if and only if the curve is a circle. Thus a circle has the largest area of any closed figure with a given perimeter.

At the other extreme, a figure with given perimeter L could have an arbitrarily small area, as illustrated by a rhombus that is "tipped over" arbitrarily far so that two of its angles are arbitrarily close to 0° and the other two are arbitrarily close to 180°.

For a circle, the ratio of the area to the circumference (the term for the perimeter of a circle) equals half the radius r. This can be seen from the area formula πr2 and the circumference formula 2πr.

The area of a regular polygon is half its perimeter times the apothem (where the apothem is the distance from the center to the nearest point on any side).

Fractals

[edit]Doubling the edge lengths of a polygon multiplies its area by four, which is two (the ratio of the new to the old side length) raised to the power of two (the dimension of the space the polygon resides in). But if the one-dimensional lengths of a fractal drawn in two dimensions are all doubled, the spatial content of the fractal scales by a power of two that is not necessarily an integer. This power is called the fractal dimension of the fractal. [33]

Area bisectors

[edit]There are an infinitude of lines that bisect the area of a triangle. Three of them are the medians of the triangle (which connect the sides' midpoints with the opposite vertices), and these are concurrent at the triangle's centroid; indeed, they are the only area bisectors that go through the centroid. Any line through a triangle that splits both the triangle's area and its perimeter in half goes through the triangle's incenter (the center of its incircle). There are either one, two, or three of these for any given triangle.

Any line through the midpoint of a parallelogram bisects the area.

All area bisectors of a circle or other ellipse go through the center, and any chords through the center bisect the area. In the case of a circle they are the diameters of the circle.

Optimization

[edit]Given a wire contour, the surface of least area spanning ("filling") it is a minimal surface. Familiar examples include soap bubbles.

The question of the filling area of the Riemannian circle remains open.[34]

The circle has the largest area of any two-dimensional object having the same perimeter.

A cyclic polygon (one inscribed in a circle) has the largest area of any polygon with a given number of sides of the same lengths.

A version of the isoperimetric inequality for triangles states that the triangle of greatest area among all those with a given perimeter is equilateral.[35]

The triangle of largest area of all those inscribed in a given circle is equilateral; and the triangle of smallest area of all those circumscribed around a given circle is equilateral.[36]

The ratio of the area of the incircle to the area of an equilateral triangle, , is larger than that of any non-equilateral triangle.[37]

The ratio of the area to the square of the perimeter of an equilateral triangle, is larger than that for any other triangle.[35]

See also

[edit]- Brahmagupta quadrilateral, a cyclic quadrilateral with integer sides, integer diagonals, and integer area.

- Equiareal map

- Heronian triangle, a triangle with integer sides and integer area.

- List of triangle inequalities

- One-seventh area triangle, an inner triangle with one-seventh the area of the reference triangle.

- Routh's theorem, a generalization of the one-seventh area triangle.

- Orders of magnitude—A list of areas by size.

- Derivation of the formula of a pentagon

- Planimeter, an instrument for measuring small areas, e.g. on maps.

- Area of a convex quadrilateral

- Robbins pentagon, a cyclic pentagon whose side lengths and area are all rational numbers.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Weisstein, Eric W. "Area". Wolfram MathWorld. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Area Formulas". Math.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Resolution 12 of the 11th meeting of the CGPM (1960)". Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. Archived from the original on 2012-07-28. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Mark de Berg; Marc van Kreveld; Mark Overmars; Otfried Schwarzkopf (2000). "Chapter 3: Polygon Triangulation". Computational Geometry (2nd revised ed.). Springer-Verlag. pp. 45–61. ISBN 978-3-540-65620-3.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. (1959). A History of the Calculus and Its Conceptual Development. Dover.

- ^ a b c Weisstein, Eric W. "Surface Area". Wolfram MathWorld. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ "Surface Area". CK-12 Foundation. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- ^ a b do Carmo, Manfredo (1976). Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces. Prentice-Hall. p. 98, ISBN 978-0-13-212589-5

- ^ Walter Rudin (1966). Real and Complex Analysis, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-100276-6.

- ^ Gerald Folland (1999). Real Analysis: modern techniques and their applications, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 20, ISBN 0-471-31716-0

- ^ Apostol, Tom (1967). Calculus. Vol. I: One-Variable Calculus, with an Introduction to Linear Algebra. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 58–59. ISBN 9780471000051.

- ^ Moise, Edwin (1963). Elementary Geometry from an Advanced Standpoint. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d Bureau international des poids et mesures (2006). The International System of Units (SI) (PDF). 8th ed. Chapter 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ^ "Land Measurement Units in India: Standard Measurement Units, Land Conversion Table". Magicbricks Blog. 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ Mishra, Sunita (2023-06-13). "Land is measured in what units in India: All Types In 2023". Housing News. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ "Standard Land Measurement Units in India - Times Property". timesproperty.com. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ www.clicbrics.com. "9 Land Measurement Units in India You Must Know - 2022". www.clicbrics.com. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ Heath, Thomas L. (2003). A Manual of Greek Mathematics. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 121–132. ISBN 978-0-486-43231-1. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01.

- ^ Stewart, James (2003). Single variable calculus early transcendentals (5th. ed.). Toronto ON: Brook/Cole. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-534-39330-4.

However, by indirect reasoning, Eudoxus (fifth century B.C.) used exhaustion to prove the familiar formula for the area of a circle:

- ^ Heath, Thomas L. (1921). A History of Greek Mathematics (Vol II). Oxford University Press. pp. 321–323.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Heron's Formula". MathWorld.

- ^ "Euclid's Proof of the Pythagorean Theorem | Synaptic". Central College. Retrieved 2023-07-12.

- ^ Clark, Walter Eugene (1930). The Aryabhatiya of Aryabhata: An Ancient Indian Work on Mathematics and Astronomy (PDF). University of Chicago Press. p. 26.

- ^ Xu, Wenwen; Yu, Ning (May 2013). "Bridge Named After the Mathematician Who Discovered the Chinese Remainder Theorem" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 60 (5): 596–597. doi:10.1090/noti993.

- ^ Bourke, Paul (July 1988). "Calculating The Area And Centroid Of A Polygon" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-09-16. Retrieved 6 Feb 2013.

- ^ Averbach, Bonnie; Chein, Orin (2012). Problem Solving Through Recreational Mathematics. Dover. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-486-13174-0.

- ^ Joshi, K. D. (2002). Calculus for Scientists and Engineers: An Analytical Approach. CRC Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8493-1319-6. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05.

- ^ a b Braden, Bart (September 1986). "The Surveyor's Area Formula" (PDF). The College Mathematics Journal. 17 (4): 326–337. doi:10.2307/2686282. JSTOR 2686282. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Trainin, J. (November 2007). "An elementary proof of Pick's theorem". Mathematical Gazette. 91 (522): 536–540. doi:10.1017/S0025557200182270. S2CID 124831432.

- ^ Matematika. PT Grafindo Media Pratama. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-979-758-477-1. Archived from the original on 2017-03-20.

- ^ Get Success UN +SPMB Matematika. PT Grafindo Media Pratama. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-602-00-0090-9. Archived from the original on 2016-12-23.

- ^ a b c Weisstein, Eric W. "Cone". Wolfram MathWorld. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ Mandelbrot, Benoît B. (1983). The fractal geometry of nature. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-1186-5. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Gromov, Mikhael (1983). "Filling Riemannian manifolds". Journal of Differential Geometry. 18 (1): 1–147. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.400.9154. doi:10.4310/jdg/1214509283. MR 0697984. Archived from the original on 2014-04-08.

- ^ a b Chakerian, G.D. (1979) "A Distorted View of Geometry." Ch. 7 in Mathematical Plums. R. Honsberger (ed.). Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, p. 147.

- ^ Dorrie, Heinrich (1965), 100 Great Problems of Elementary Mathematics, Dover Publ., pp. 379–380.

- ^ Minda, D.; Phelps, S. (October 2008). "Triangles, ellipses, and cubic polynomials". American Mathematical Monthly. 115 (8): 679–689: Theorem 4.1. doi:10.1080/00029890.2008.11920581. JSTOR 27642581. S2CID 15049234. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04.

External links

[edit]Definition and Basics

Formal Definition

Area represents the intuitive measure of the two-dimensional extent occupied by a plane figure or the space enclosed within its boundary, akin to the amount of material needed to fill or cover that region completely.[9] This contrasts with perimeter, which quantifies the one-dimensional length of the boundary outlining the figure; for instance, filling a circular disk with paint corresponds to its area, whereas tracing its edge with a string measures the perimeter. Formally, in modern mathematics, area is defined as the Lebesgue measure on the Euclidean plane , which provides a complete, translation-invariant, and countably additive measure for Lebesgue-measurable sets. The Lebesgue measure is constructed via the outer measure , defined for any set as the infimum of the sums of areas of countable collections of open rectangles covering , where the area of a rectangle is ; a set is Lebesgue measurable if for all , and then .[10] This framework extends the elementary notion of area to a broad class of sets while preserving properties like monotonicity and additivity for disjoint unions.[11] For simpler regions bounded by Jordan curves—continuous, non-self-intersecting closed paths—an axiomatic approach defines area through Jordan measurability, which approximates the region using finite unions of rectangles to compute inner and outer contents. A bounded set is Jordan measurable if the supremum of the total areas of finite unions of rectangles contained in (inner content) equals the infimum of those covering (outer content), yielding the Jordan measure as this common value; this is finitely additive but not necessarily countably additive.[12] Jordan measurability applies particularly to regions with boundaries of measure zero, such as polygons or smooth curves, providing a precursor to the Lebesgue definition.[13] Not all subsets of admit such a measure; the Vitali set, constructed by partitioning into equivalence classes modulo the rationals and selecting one representative from each using the axiom of choice, is non-Lebesgue measurable, as its countable disjoint translates by rationals would imply contradictory measure assignments under translation invariance and additivity. This example underscores the necessity of restricting area definitions to measurable sets in the axiomatic framework.Units of Area

Area is quantified using square units, which represent the product of two lengths and thus have dimensions of length squared, denoted as [L²] in dimensional analysis. This fundamental relationship arises because area measures the extent of a two-dimensional surface, equivalent to multiplying a length by another length. In the International System of Units (SI), the standard unit of area is the square meter (m²), defined as the area of a square with each side measuring exactly one meter. The meter itself is defined as the distance traveled by light in vacuum in 1/299,792,458 of a second, making the square meter a derived unit based on this base length.[14] Common imperial units include the square foot (ft²), which is the area of a square with sides of one foot, and the acre, defined as 43,560 square feet. The foot is a base unit in the imperial system, approximately equal to 0.3048 meters, so the square foot and acre are similarly derived by squaring or scaling this length. These units find practical applications in everyday contexts; for instance, square meters are commonly used to measure flooring or wall coverings in residential and commercial buildings, while acres are standard for denoting land areas in agriculture and real estate in regions employing imperial measures.[14]Measurement Systems

Metric and Imperial Conversions

The conversion between metric and imperial units of area stems directly from the corresponding linear unit conversions, as area scales with the square of the linear dimensions. The international foot is defined as exactly 0.3048 meters by international agreement, making one square foot exactly 0.09290304 square meters.[15] Therefore, the exact conversion formula is .[15] Common conversions include those for larger land areas, such as hectares to acres. One hectare equals exactly 10,000 square meters, while one acre is defined as exactly 43,560 square feet, or 4,046.8564224 square meters. Thus, . For smaller scales, one square centimeter converts to approximately 0.15500031 square inches, derived from the exact relation , so .[15] The following table provides quick reference equivalents for select metric and imperial area units, using the precise factors above:| Metric Unit | Imperial Equivalent |

|---|---|

| 1 m² | ≈ 10.76391 ft² |

| 1 cm² | ≈ 0.15500 in² |

| 1 ha | ≈ 2.47105 ac |

| 1 km² | ≈ 0.38610 mi² |

![{\displaystyle A=2\pi \int _{a}^{b}\!f(x){\sqrt {1+\left[f'(x)\right]^{2}}}\mathrm {d} x}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/07cf6da325a77c650339de80d9b00d984ca3751d)