Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Asiatic linsang

View on Wikipedia

| Asiatic linsang Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

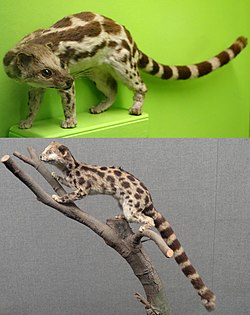

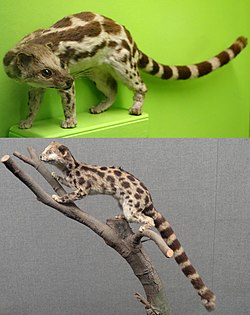

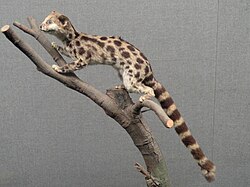

| Banded linsang (Prionodon linsang) and spotted linsang (P. pardicolor) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Superfamily: | Feloidea Gray, 1864[2] |

| Family: | Prionodontidae Gray, 1864[2] |

| Genus: | Prionodon Horsfield, 1822[1] |

| Type species | |

| Prionodon gracilis[3] | |

| Species | |

| |

The Asiatic linsang (Prionodon) is a genus comprising two species native to Southeast Asia: the banded linsang (Prionodon linsang) and the spotted linsang (Prionodon pardicolor).[4][5] Prionodon is considered a sister taxon of the Felidae.[6]

Characteristics

[edit]The coat pattern of the Asiatic linsang is distinct, consisting of large spots that sometimes coalesce into broad bands on the sides of the body; the tail is banded transversely. It is small in size with a head and body length ranging from 36.6 to 42.5 cm (14.4 to 16.75 in) and a 30 to 41 cm (12 to 16 in) long tail. The tail is nearly as long as the head and body, and about five or six times as long as the hind foot. The head is elongated with a narrow muzzle, rhinarium evenly convex above, with wide internarial septum, shallow infranarial portion, and philtrum narrow and grooved, the groove extending only about to the level of the lower edge of the nostrils. The delicate skull is long, low, and narrow with a well defined occipital and a strong crest, but there is no complete sagittal crest. The teeth also are more highly specialized, and show an approach to those of Felidae, although more primitive. The dental formula is 3.1.4.13.1.4.2. The incisors form a transverse, not a curved, line; the first three upper and the four lower pre-molars are compressed and trenchant with a high, sharp, median cusp and small subsidiary cusps in front and behind it. The upper carnassial has a small inner lobe set far forwards, a small cusp in front of the main compressed, high, pointed cusp, and a compressed, blade-like posterior cusp; the upper molar is triangular, transversely set, much smaller than the upper carnassial, and much wider than it is long, so that the upper carnassial is nearly at the posterior end of the upper cheek-teeth as in Felidae.[4]

Systematics

[edit]| Genus | Image | Species |

|---|---|---|

| Prionodon |

|

Banded linsang (P. linsang) Hardwicke, 1821 |

|

Spotted linsang (P. pardicolor) Hodgson, 1842 |

Taxonomic history

[edit]With Viverridae (morphological)

[edit]Prionodon was denominated and first described by Thomas Horsfield in 1822, based on a linsang from Java. He had placed the linsang under "section Prionodontidae" of the genus Felis, because of similarities to both genera Viverra and Felis.[1] In 1864, John Edward Gray placed the genera Prionodon and Poiana in the tribe Prionodontina, as part of Viverridae.[2] Reginald Innes Pocock initially followed Gray's classification, but the existence of scent glands in Poiana induced him provisionally to regard the latter as a specialized form of Genetta, its likeness to Prionodon being possibly adaptive.[4] Furthermore, the skeletal anatomy of Asiatic linsangs are said to be a mosaic of features of other viverrine-like mammals, as linsangs share cranial, postcranial and dental similarities with falanoucs, African palm civet, and oyans respectively.[7]

With Felidae (molecular)

[edit]DNA analysis based on 29 species of Carnivora, comprising 13 species of Viverrinae and three species representing Paradoxurus, Paguma and Hemigalinae, confirmed Pocock's assumption that the African linsang Poiana represents the sister-group of the genus Genetta. The placement of Prionodon as the sister-group of the family Felidae is strongly supported, and it was proposed that the Asiatic linsangs be placed in the monogeneric family Prionodontidae.[8] There is a physical synapomorphy shared between felids and Prionodon in the presence of the specialized fused sacral vertebrae.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Horsfield, T. (1822). Illustration of Felis gracilis in Zoological researches in Java, and the neighboring islands. Kingsbury, Parbury and Allen, London.

- ^ a b c Gray, J. E. (1864). A revision of the genera and species of viverrine animals (Viverridae), founded on the collection in the British Museum. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London for the year 1864: 502–579.

- ^ Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Genus Prionodon Horsfield". The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Vol. Mammalia. – Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 334–342.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Genus Prionodon". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 553. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Barycka, E. (2007). "Evolution and systematics of the feliform Carnivora". Mammalian Biology. 72 (5): 257–282. Bibcode:2007MamBi..72..257B. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2006.10.011.

- ^ a b Gaubert, P. (2009). "Family Prionodontidae (Linsangs)". In Wilson, D.E.; Mittermeier, R.A. (eds.). Handbook of the Mammals of the World – Volume 1. Barcelona: Lynx Ediciones. pp. 170–173. ISBN 978-84-96553-49-1.

- ^ Gaubert, P. and Veron, G. (2003). "Exhaustive sample set among Viverridae reveals the sister-group of felids: the linsangs as a case of extreme morphological convergence within Feliformia". Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B, 270 (1532): 2523–2530. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2521

Asiatic linsang

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy

Species

The genus Prionodon was established by Thomas Horsfield in 1822, with the type species Prionodon gracilis (now considered a subspecies of P. linsang).[6] The family Prionodontidae includes only this genus, which comprises two species and is distinguished from other carnivoran families by its unique morphological and ecological traits.[7] The banded linsang (Prionodon linsang) was first described by Thomas Hardwicke in 1821 and occurs in the Sundaic lowlands of Southeast Asia, where it inhabits lowland forests; it is characterized by pale yellowish fur with five to seven dark bands across the body and a tail marked by multiple dark rings. Four subspecies are recognized: P. l. linsang (Malay Peninsula and Sumatra), P. l. gracilis (Java), P. l. borneanus (Borneo), and P. l. pyi (possibly extinct).[8][9][7] The spotted linsang (Prionodon pardicolor), described by Brian Houghton Hodgson in 1841, ranges from the Himalayan foothills through parts of South and Southeast Asia, including Nepal, India, Bhutan, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia; its fur is soft and dense, typically orange-buff to grayish with dark spots arranged in longitudinal rows and a tail featuring seven to nine broad dark rings. The species is considered monotypic, with no subspecies currently recognized.[10][3]Taxonomic history

The genus Prionodon was first described by Thomas Horsfield in 1822 based on specimens from Java and initially classified within the family Viverridae owing to shared morphological traits with civets, including similar dental formulas and cranial proportions.[11] Throughout the 19th century, this placement persisted in classifications, as Prionodon exhibited viverrid-like features such as perianal scent glands and arboreal adaptations akin to genets and civets.[12] In 1864, John Edward Gray recognized distinctions in a revision of viverrine taxa, elevating Prionodon (along with the African linsang genus Poiana) to the tribe Prionodontina within Viverridae, justified by its unique cranial morphology: a long, narrow skull lacking a complete sagittal crest, unlike the more robust structures in other viverrids. This separation highlighted Prionodon's primitive dentition and elongated rostrum, setting it apart from typical civet-like forms while retaining overall viverrid affinities based on morphological evidence.[13] Molecular phylogenies from the 2000s, employing cytochrome b and nuclear gene sequences, reshaped this view by demonstrating Prionodon as the sister group to Felidae rather than deeply nested within Viverridae, positioning it as a basal feliform carnivoran with genetic distances (p-distances of 0.177–0.191) supporting its distinct family Prionodontidae. These studies revealed extreme morphological convergence with viverrids, explaining prior misclassifications, and confirmed Prionodon's divergence around 34 million years ago (95% HPD: 30–38 Ma) as the most primitive extant feloid outside Felidae.[14] Recent mitogenomic analyses as of 2025 continue to support Prionodontidae as the sister family to Felidae, with Eupleridae (including the fossa) positioned as sister to Viverridae.[15]Description

Physical features

The Asiatic linsangs, comprising the banded linsang (Prionodon linsang) and the spotted linsang (Prionodon pardicolor), exhibit similar body sizes across both species, with a head-body length ranging from 35 to 45 cm, a tail length of 30 to 42 cm, and a weight of 0.6 to 0.8 kg.[16][3] These animals possess an elongated, slender build with short legs, giving them a resemblance to a hybrid of a cat and a weasel, complemented by a highly flexible spine that facilitates arboreal locomotion.[9] Their overall frame is agile and adapted for climbing, with a long tail providing balance during tree navigation.[9] The skull is long and narrow, with a partial sagittal crest, aligning with their small size and carnivorous adaptations. The dental formula is 3.1.4.1/3.1.4.2, totaling 38 teeth, featuring carnassial teeth specialized for shearing meat.[17] The limbs are short yet robust, equipped with retractile claws and padded soles on the feet to enhance grip and traction during climbing.[3] They also have large eyes adapted for nocturnal vision and rounded ears.Coloration and markings

The Asiatic linsangs are characterized by a short, soft coat of yellowish or buff fur, providing a base color that contrasts with distinctive dark markings consisting of spots or bands. This pelage is dense and velvety, aiding in their arboreal lifestyle through camouflage in forested environments.[2][3] In the banded linsang (Prionodon linsang), the dark markings on the body tend to merge, forming prominent bands, including five large transverse dark bands across the back and broad stripes on the neck, with smaller elongate spots and stripes along the flanks. The tail, nearly as long as the body, bears seven to eight dark bands and terminates in a dark tip.[2][18][9] The spotted linsang (Prionodon pardicolor), by comparison, features more discrete dark spots arranged in longitudinal rows across the body, with sparser spotting on the limbs extending to the paws on the forelegs and to the hocks on the hindlegs; the overall coat tone ranges from orange-buff to pale brown. Its cylindrical tail displays eight to nine broad dark rings, separated by narrow pale interspaces. There is no significant sexual dimorphism in coloration between males and females of either species.[3][19]Distribution and habitat

Geographic range

The Asiatic linsangs, comprising the banded linsang (Prionodon linsang) and the spotted linsang (Prionodon pardicolor), are distributed across Southeast Asia, spanning from eastern India to Indonesia.[2][3] The banded linsang occupies the Sundaic region of Southeast Asia, including southern Myanmar, the Malay Peninsula (western Malaysia and southern Thailand), Sumatra, Borneo, and Java in Indonesia.[2][4] This species is found from sea level to 2,700 m elevation, primarily in lowland areas but with records in montane forests, including up to 1,800 m in Borneo.[20] In contrast, the spotted linsang ranges across mainland Southeast Asia, from the Himalayan foothills in Nepal, Bhutan, and northeastern India (including Assam) through Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and into southern China.[3] It inhabits elevations from near sea level up to 2,500 m, with most records below 1,500 m.[21] The two species exhibit no overlap in their distributions, with the banded linsang confined to island and peninsular Sundaic lowlands and the spotted linsang restricted to continental areas. Historically, the range of both species was likely broader, but habitat loss from deforestation has led to contractions, including the apparent disappearance of the spotted linsang from parts of its former range such as Sikkim in India and much of Thailand.[3][11]Habitat preferences

Asiatic linsangs primarily inhabit tropical evergreen and deciduous forests characterized by dense canopies that support their arboreal lifestyle. These environments provide ample cover and structural complexity for climbing and foraging.[2] The banded linsang (Prionodon linsang) favors lowland rainforests, secondary forests, and even plantations, showing tolerance for disturbed areas with vines, epiphytes, and climbing plants. It occurs in primary and secondary evergreen forests, as well as mixed deciduous types, often near human-modified landscapes.[4] In contrast, the spotted linsang (Prionodon pardicolor) prefers montane and subtropical broadleaf forests, exhibiting a more stringent habitat selection for primary or undisturbed areas with high vegetation cover. It is recorded in evergreen biomes, bamboo forests, secondary growth, and mixed evergreen-deciduous forests, favoring sites with dense understory near hills and rivers.[22] Both species occupy elevations from sea level to approximately 2,500 m, generally avoiding open grasslands and highly fragmented landscapes in favor of forested niches.Behavior and ecology

Activity patterns

The Asiatic linsangs, comprising the banded linsang (Prionodon linsang) and the spotted linsang (Prionodon pardicolor), exhibit primarily nocturnal and crepuscular activity patterns, with the majority of their active period occurring during nighttime hours.[23] Both species show bimodal peaks in activity during twilight and late night periods, aligning with peak hunting efforts in low-light conditions.[24] For the spotted linsang, recent camera-trap data indicate nocturnal activity with peaks in autumn, influenced by temperature and altitude.[22] During the day, individuals rest in concealed sites such as tree hollows, nesting holes at ground level, or dense foliage, often lining these shelters with dry leaves and twigs for comfort.[3][9] These linsangs lead solitary lifestyles, with minimal social interactions limited largely to mating encounters, and each maintains an individual home range whose exact size remains poorly documented due to the species' elusive nature.[4][3] Locomotion is semiarboreal, characterized by agile climbing facilitated by sharp claws for gripping bark and a long tail that provides balance during movement through branches.[2] Individuals navigate both trees and ground levels fluidly, employing a sinuous, snake-like gait when stalking prey, though they are not strictly arboreal and frequently forage terrestrially.[17][4] Scent marking helps enforce territorial boundaries in their low-density populations.[3]Diet and foraging

The Asiatic linsangs are carnivorous, with diets consisting primarily of small mammals such as rodents and squirrels, along with birds and their eggs, reptiles including lizards, frogs, and snakes, and smaller shares of insects and other invertebrates.[3][2] Opportunistic scavenging on carrion has also been recorded.[3] Foraging occurs primarily at night, aligning with their nocturnal activity patterns, and employs an ambush predation strategy where linsangs position themselves in trees or dense understory vegetation to pounce on prey moving below or nearby.[2] Their slender, elongated bodies and camouflaged pelage enable stealthy, snake-like movements along branches or the forest floor to stalk targets, with sharp retractile claws and a long tail aiding balance during arboreal pursuits.[2] Ground hunting supplements this, particularly near water sources where amphibians and reptiles are abundant, though arboreal elements predominate due to their semi-arboreal lifestyle.[17] Dietary details remain limited, with no well-documented differences in prey selection between the two species, though the banded linsang is observed to take a variety of small vertebrates reflecting its habitat, and the spotted linsang primarily consumes rodents alongside other small prey.[3][2] Both species exhibit solitary hunting, with limited daily movement to conserve energy while exploiting dense forest niches.[2]Reproduction

The reproductive biology of the Asiatic linsang (genus Prionodon), encompassing the banded linsang (P. linsang) and spotted linsang (P. pardicolor), remains poorly documented due to the species' elusive, nocturnal habits and limited field observations. Breeding appears to occur semiannually or in distinct seasons, with females capable of producing one or two litters per year; for the spotted linsang, peaks are recorded in February and August.[3][2] Given their solitary nature, mating likely involves brief encounters between individuals, though the mating system has not been confirmed.[2] Gestation period is unknown for both species, though related viverrids exhibit durations of 60–81 days.[25] Litter sizes are small, commonly numbering two young for the spotted linsang, with similar estimates of 2–3 suggested for the banded linsang based on limited records.[3] Young are altricial, born helpless and blind in concealed dens such as tree hollows or root cavities lined with dried vegetation, where they remain hidden from predators.[3] Parental care is provided solely by females, who nurse and protect the offspring; males do not participate and maintain separate territories.[2] In the spotted linsang, camera-trap evidence indicates extended post-weaning care, with juveniles aged 4–6 weeks following presumed mothers, suggesting guidance in foraging and movement before independence. For the banded linsang, male young disperse soon after weaning, while females stay with the mother until reaching sexual maturity, though the exact timing of weaning, independence, and maturity remains undocumented for both species.[2]Conservation

Status

The Asiatic linsang genus Prionodon comprises two species, both assessed under the IUCN Red List criteria, with conservation statuses reflecting their respective vulnerabilities despite limited data availability.[27] The banded linsang (Prionodon linsang) is classified as Least Concern by the IUCN, as of the 2016 assessment.[4] Its population is poorly known, considered stable overall but with low encounter rates indicating rarity or elusiveness across its range; no precise estimate of mature individuals exists, though it exceeds thresholds for threatened categories.[4] The species is listed under CITES Appendix II, regulating international trade.[28] The spotted linsang (Prionodon pardicolor) is also classified as Least Concern by the IUCN, as of the 2016 assessment, though it is regarded as rarer and more sparsely distributed than its congener.[29] Population estimates remain unavailable globally, but records suggest declining trends in some regions due to habitat fragmentation, with overall numbers sufficient to avoid threatened status.[30] It is afforded higher protection under CITES Appendix I, prohibiting commercial trade.[28] Collectively, the genus faces no global threat designation, remaining regionally vulnerable in fragmented forest habitats without a unified CITES listing at the genus level.[27] Monitoring efforts are constrained, relying primarily on camera trap surveys in protected areas, which yield infrequent detections and underscore the need for enhanced data collection; recent records as of 2025 continue to highlight their elusiveness.[4][31]Threats and protection

The primary threats to Asiatic linsangs stem from habitat destruction driven by logging and agricultural expansion, which have substantially reduced the extent of tropical evergreen forests essential to their survival. For the banded linsang, evergreen forest and shrubland cover around historical occurrence sites has declined, reflecting broader deforestation trends across Southeast Asia. Incidental capture in snares and traps intended for other wildlife species further exacerbates population pressures, as these non-selective methods frequently ensnare the elusive linsangs.[32] Secondary threats include direct hunting for fur, meat, and use in traditional medicine, with the spotted linsang appearing more vulnerable due to its wider exposure in trade records from regions like India and Myanmar. Climate change poses an additional risk by potentially shifting suitable habitat elevations through altered temperature and precipitation patterns in montane forests.[33] Conservation measures benefit from the species' occurrence in protected areas, such as Kerinci Seblat National Park in Indonesia, where the banded linsang has been documented, and Namdapha Tiger Reserve in India, supporting populations of the spotted linsang.[34][35] Ongoing research coordinated by the IUCN SSC Small Carnivore Specialist Group aids in monitoring and assessment.[36] To address these challenges, experts recommend intensified anti-poaching patrols, reforestation programs to restore degraded habitats, and expanded ecological studies to inform targeted interventions.[4]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/363084440_Evidence_of_Spotted_Linsang_Prionodon_pardicolor_post-weaning_parental_care