Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Feces

View on Wikipedia

Feces (also faeces or fæces) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine.[1][2] Feces contain a relatively small amount of metabolic waste products such as bacterially-altered bilirubin and dead epithelial cells from the lining of the gut.[1]

Feces are discharged through the anus or cloaca during defecation.

Feces can be used as fertilizer or soil conditioner in agriculture. They can also be burned as fuel or dried and used for construction. Some medicinal uses have been found. In the case of human feces, fecal transplants or fecal bacteriotherapy are in use. Urine and feces together are called excreta.

Characteristics

[edit]

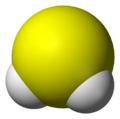

The distinctive odor of feces is due to skatole, and thiols (sulfur-containing compounds), as well as amines and carboxylic acids. Skatole is produced from tryptophan via indoleacetic acid. Decarboxylation gives skatole.[3][4]

The perceived bad odor of feces has been hypothesized to be a deterrent for humans, as consuming or touching it may result in sickness or infection.[5]

Physiology

[edit]Feces are discharged through the anus or cloaca during defecation. This process requires pressures that may reach 100 millimetres of mercury (3.9 inHg) (13.3 kPa) in humans and 450 millimetres of mercury (18 inHg) (60 kPa) in penguins.[6][7] The forces required to expel the feces are generated through muscular contractions and a build-up of gases inside the gut, prompting the sphincter to relieve the pressure and release the feces.[7]

Ecology

[edit]After an animal has digested eaten material, the remains of that material are discharged from its body as waste. Although it is lower in energy than the food from which it is derived, feces may retain a large amount of energy, often 50% of that of the original food.[8] This means that of all food eaten, a significant amount of energy remains for the decomposers of ecosystems.

Many organisms feed on feces, from bacteria to fungi to insects such as dung beetles, who can sense odors from long distances.[9] Some may specialize in feces, while others may eat other foods. Feces serve not only as a basic food, but also as a supplement to the usual diet of some animals. This process is known as coprophagia, and occurs in various animal species such as young elephants eating the feces of their mothers to gain essential gut flora, or by other animals such as dogs, rabbits, and monkeys.

Feces and urine, which reflect ultraviolet light, are important to raptors such as kestrels, who can see the near ultraviolet and thus find their prey by their middens and territorial markers.[10]

Seeds also may be found in feces. Animals who eat fruit are known as frugivores. An advantage for a plant in having fruit is that animals will eat the fruit and unknowingly disperse the seed in doing so. This mode of seed dispersal is highly successful, as seeds dispersed around the base of a plant are unlikely to succeed and often are subject to heavy predation. Provided the seed can withstand the pathway through the digestive system, it is not only likely to be far away from the parent plant, but is even provided with its own fertilizer.

Organisms that subsist on dead organic matter or detritus are known as detritivores, and play an important role in ecosystems by recycling organic matter back into a simpler form that plants and other autotrophs may absorb once again. This cycling of matter is known as the biogeochemical cycle. To maintain nutrients in soil it is therefore important that feces returns to the area from which they came, which is not always the case in human society where food may be transported from rural areas to urban populations and then feces disposed of into a river or sea.

Human feces

[edit]Depending on the individual and the circumstances, human beings may defecate several times a day, every day, or once every two or three days. Extensive hardening of the feces that interrupts this routine for several days or more is called constipation.

The appearance of human fecal matter varies according to diet and health.[11] Normally it is semisolid, with a mucus coating. A combination of bile and bilirubin, which comes from dead red blood cells, gives feces the typical brown color.[1][2]

After the meconium, the first stool expelled, a newborn's feces contains only bile, which gives it a yellow-green color. Breast feeding babies expel soft, pale yellowish, and not quite malodorous matter; but once the baby begins to eat, and the body starts expelling bilirubin from dead red blood cells, its matter acquires the familiar brown color.[2]

At different times in their life, human beings will expel feces of different colors and textures. A stool that passes rapidly through the intestines will look greenish; lack of bilirubin will make the stool look like clay.

Uses of animal feces

[edit]Fertilizer

[edit]The feces of animals, e.g. guano and manure, often are used as fertilizer.[12]

Energy

[edit]Dry animal dung, such as that of camel, bison and cattle, is burned as fuel in many countries.[13]

Animals such as the giant panda[14] and zebra[15] possess gut bacteria capable of producing biofuel. The bacterium in question, Brocadia anammoxidans, can be used to synthesize the rocket fuel hydrazine.[16][17]

Coprolites and paleofeces

[edit]A coprolite is fossilized feces and is classified as a trace fossil. In paleontology they give evidence about the diet of an animal. They were first described by William Buckland in 1829. Prior to this, they were known as "fossil fir cones" and "bezoar stones". They serve a valuable purpose in paleontology because they provide direct evidence of the predation and diet of extinct organisms.[18] Coprolites may range in size from a few millimetres to more than 60 centimetres.

Palaeofeces are ancient feces, often found as part of archaeological excavations or surveys. Intact paleofeces of ancient people may be found in caves in arid climates and in other locations with suitable preservation conditions. These are studied to determine the diet and health of the people who produced them through the analysis of seeds, small bones, and parasite eggs found inside. Feces may contain information about the person excreting the material as well as information about the material. They also may be analyzed chemically for more in-depth information on the individual who excreted them, using lipid analysis and ancient DNA analysis. The success rate of usable DNA extraction is relatively high in paleofeces, making it more reliable than skeletal DNA retrieval.[19]

The reason this analysis is possible at all is due to the digestive system not being entirely efficient, in the sense that not everything that passes through the digestive system is destroyed. Not all of the surviving material is recognizable, but some of it is. Generally, this material is the best indicator archaeologists can use to determine ancient diets, as no other part of the archaeological record is so direct an indicator.[20]

A process that preserves feces in a way that they may be analyzed later is the Maillard reaction. This reaction creates a casing of sugar that preserves the feces from the elements. To extract and analyze the information contained within, researchers generally have to freeze the feces and grind it up into powder for analysis.[21]

Other uses

[edit]

Animal dung occasionally is used as a cement to make adobe (mudbrick) huts,[22] or even in throwing sports, especially with cow and camel dung.[23]

Kopi luwak, or civet coffee, is coffee made from coffee beans that have been eaten and excreted by Asian palm civets (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus).[24]

Giant pandas provide fertilizer for the world's most expensive green tea.[25] In Malaysia, tea is made from the droppings of stick insects fed on guava leaves.

In northern Thailand, elephants are used to digest coffee beans in order to make Black Ivory coffee, which is among the world's most expensive coffees. Paper is also made from elephant dung in Thailand.[25] Haathi Chaap is a brand of paper made from elephant dung.

Dog feces was used in the tanning process of leather during the Victorian era. Collected dog feces, known as "pure", "puer", or "pewer",[26] were mixed with water to form a substance known as "bate", because proteolytic enzymes in the dog feces helped to relax the fibrous structure of the hide before the final stages of tanning.[27] Dog feces collectors were known as pure finders.[28]

Elephants, hippos, koalas and pandas are born with sterile intestines, and require bacteria obtained from eating the feces of their mothers to digest vegetation.

In India, cow dung and cow urine are major ingredients of the traditional Hindu drink Panchagavya. Politician Shankarbhai Vegad stated that they can cure cancer.[29]

Terminology

[edit]

Feces is the scientific terminology, while the term stool is also commonly used in medical contexts.[30] Outside of scientific contexts, these terms are less common, with the most common layman's term being poop or poo. The term shit is also in common use, although it is widely considered vulgar or offensive. There are many other terms, see below.

Etymology

[edit]The word faeces is the plural of the Latin word faex meaning "dregs". In most English-language usage, there is no singular form, making the word a plurale tantum;[31] out of various major dictionaries, only one enters variation from plural agreement.[32]

Synonyms

[edit]"Feces" is used more in biology and medicine than in other fields (reflecting science's tradition of classical Latin and Neo-Latin)

- In hunting and tracking, terms such as dung, scat, spoor, and droppings normally are used to refer to non-human animal feces

- In husbandry and farming, manure is common.

- Stool is a common term in reference to human feces. For example, in medicine, to diagnose the presence or absence of a medical condition, a stool sample sometimes is requested for testing purposes.[33]

- The term bowel movement(s) (with each movement a defecation event) is also common in health care.

There are many synonyms in informal registers for feces, just like there are for urine. Many are euphemistic, colloquial, or both; some are profane (such as shit), whereas most belong chiefly to child-directed speech) or to crude humor (such as crap, dump, load and turd).

Feces of animals

[edit]The feces of animals often have special names (some of them are slang), for example:

- Non-human animals

- As bulk material – dung

- Individually – droppings

- Cattle

- Bulk material – cow dung

- Individual droppings – cow pats, meadow muffins, etc.

- Deer (and formerly other quarry animals) – fewmets

- Wild carnivores – scat

- Otter – spraint

- Birds (individual) – droppings (also include urine as white crystals of uric acid)

- Seabirds or bats (large accumulations) – guano

- Herbivorous insects, such as caterpillars and leaf beetles – frass

- Earthworms, lugworms etc. – worm castings (feces extruded at ground surface)

- Feces when used as fertilizer (usually mixed with animal bedding and urine) – manure

- Horses – horse manure, roadapple (before motor vehicles became common, horse droppings were a big part of the rubbish communities needed to clean off roads)

Society and culture

[edit]

Feelings of disgust

[edit]In all human cultures, feces elicit varying degrees of disgust in adults. Children under two years typically have no disgust response to it, suggesting it is culturally derived.[34] Disgust toward feces appears to be strongest in cultures where flush toilets make olfactory contact with human feces minimal.[35][36] Disgust is experienced primarily in relation to the sense of taste (either perceived or imagined) and, secondarily to anything that causes a similar feeling by sense of smell, touch, or vision.

Social media

[edit]There is a Pile of Poo emoji represented in Unicode as U+1F4A9 💩 PILE OF POO, called unchi or unchi-kun in Japan.[37][38]

Jokes

[edit]Poop is the center of toilet humor, and is commonly an interest of young children and teenagers.[39]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Tortora, Gerard J.; Anagnostakos, Nicholas P. (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (Fifth ed.). New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. p. 624. ISBN 978-0-06-350729-6.

- ^ a b c Diem, K.; Lentner, C. (1970). "Faeces". in: Scientific Tables (Seventh ed.). Basle, Switzerland: CIBA-GEIGY Ltd. pp. 657–660.

- ^ Whitehead, T. R.; Price, N. P.; Drake, H. L.; Cotta, M. A. (25 January 2008). "Catabolic pathway for the production of skatole and indoleacetic acid by the acetogen Clostridium drakei, Clostridium scatologenes, and swine manure". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 74 (6): 1950–3. Bibcode:2008ApEnM..74.1950W. doi:10.1128/AEM.02458-07. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 2268313. PMID 18223109.

- ^ Yokoyama, M. T.; Carlson, J. R. (1979). "Microbial metabolites of tryptophan in the intestinal tract with special reference to skatole". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 32 (1): 173–178. doi:10.1093/ajcn/32.1.173. PMID 367144.

- ^ Curtis V, Aunger R, Rabie T (May 2004). "Evidence that disgust evolved to protect from risk of disease". Proc. Biol. Sci. 271 (Suppl 4): S131–3. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0144. PMC 1810028. PMID 15252963.

- ^ Langley, Leroy Lester; Cheraskin, Emmanuel (1958). The Physiology of Man. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno; Gal, Jozsef (2003). "Pressures produced when penguins pooh?calculations on avian defaecation". Polar Biology. 27 (1): 56–58. Bibcode:2003PoBio..27...56M. doi:10.1007/s00300-003-0563-3. ISSN 0722-4060. S2CID 43386022.

- ^ Cummings, Benjamin; Campbell, Neil A. (2008). Biology, 8th Edition, Campbell & Reece, 2008: Biology (8th ed.). Pearson. p. 890.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Heinrich B, Bartholomew GA (1979). "The ecology of the African dung beetle". Scientific American. 241 (5): 146–56. Bibcode:1979SciAm.241e.146H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1179-146.

- ^ "Document: Krestel". City of Manhattan, Kansas. Retrieved 11 February 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Stromberg, Joseph (22 January 2015). "Everybody poops. But here are 9 surprising facts about feces you may not know". Vox. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Dittmar, Heinrich; Drach, Manfred; Vosskamp, Ralf; Trenkel, Martin E.; Gutser, Reinhold; Steffens, Günter (2009). "Fertilizers, 2. Types". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.n10_n01. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ "STCWA". Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Handwerk, Brian (11 September 2013). "Panda Poop Might Help Turn Plants Into Fuel". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Ray, Kathryn Hobgood (25 August 2011). "Cars Could Run on Recycled Newspaper, Tulane Scientists Say". Tulane News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Handwerk, Brian (9 November 2005). "Bacteria Eat Human Sewage, Produce Rocket Fuel". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019 – via wildsingapore.com.

- ^ Harhangi, HR; Le Roy, M; van Alen, T; Hu, BL; Groen, J; Kartal, B; Tringe, SG; Quan, ZX; Jetten, MS; Op; den Camp, HJ (2012). "Hydrazine synthase, a unique phylomarker with which to study the presence and biodiversity of anammox bacteria". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 (3): 752–8. Bibcode:2012ApEnM..78..752H. doi:10.1128/AEM.07113-11. PMC 3264106. PMID 22138989.

- ^ "Definition of coprolite | Dictionary.com". dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Poinar, Hendrik N.; et al. (10 April 2001). "A Molecular Analysis of Dietary Diversity for Three Archaic Native Americans". PNAS. 98 (8): 4317–4322. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.4317P. doi:10.1073/pnas.061014798. PMC 31832. PMID 11296282.

- ^ Feder, Kenneth L. (2008). Linking to the Past: A Brief Introduction to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533117-2. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Stokstad, Erik (28 July 2000). "Divining Diet and Disease From DNA". Science. 289 (5479): 530–531. doi:10.1126/science.289.5479.530. PMID 10939960. S2CID 83373644.

- ^ "Your Home Technical Manual – 3.4d Construction Systems – Mud Brick (Adobe)". Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ "Dung Throwing contests". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- ^ Marcone, M. (2004). "Composition and properties of Indonesian palm civet coffee (Kopi Luwak) and Ethiopian civet coffee" (PDF). Food Research International. 37 (9): 901–912. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2004.05.008.

- ^ a b Topper, R (15 October 2012). "Elephant Dung Coffee: World's Most Expensive Brew Is Made With Pooped-Out Beans". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ "pure". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) n., 6

- ^ "Rohm and Haas Innovation - The Leather Breakthrough". Rohmhaas.com. 1 September 1909. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Steven (2006). The ghost map: the story of London's most terrifying epidemic--and how it changed science, cities, and the modern world. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 1-59448-925-4. OCLC 70483471.

- ^ Ramachandran, Smriti Kak (19 March 2015). "Cow dung, urine can cure cancer: BJP MP". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "stool". Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2017 – via The Free Dictionary.

- ^ "Feces definition – Medical Dictionary definitions of popular medical terms easily defined on MedTerms". Medterms. Medterms.com. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, archived from the original on 25 September 2015, retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Steven Dowshen, MD (September 2011). "Stool Test: Bacteria Culture". Kidshealth. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Moore, Alison M. (8 November 2018). "Coprophagy in nineteenth-century psychiatry". Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease. 30 (sup1) 1535737. doi:10.1080/16512235.2018.1535737. PMC 6225515. PMID 30425610.

- ^ "Yes, poop is gross. But that's not the only reason for its shameful social stigma". Upworthy. 25 May 2016. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Goldman, Jason G. (11 November 2013). "Why do humans hate poo so much?". BBC. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Lauren (18 November 2014), "The Oral History Of The Poop Emoji (Or, How Google Brought Poop To America)", Fast Company, archived from the original on 3 April 2018, retrieved 9 November 2016

- ^ Darlin, Damon (7 March 2015), "America Needs its own Emojis", The New York Times, archived from the original on 30 October 2016, retrieved 1 March 2017

- ^ Praeger, Dave (2007). Poop Culture: How America Is Shaped by Its Grossest National Product. United States: Feral House. ISBN 978-1-932595-21-5.

External links

[edit]- Article on Feces – MedFriendly

Feces

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Composition and Physical Properties

Feces consist primarily of water, which accounts for approximately 75% of its total mass, with the remaining 25% comprising dry solids.[4] The dry matter is predominantly organic, including undigested food residues such as carbohydrates (around 25%), lipids (2–15%), and proteins (2–25%), along with inorganic salts like calcium and iron phosphates.[4] Bile pigments, derived from the breakdown of hemoglobin, contribute to the chemical profile and influence coloration.[7] Biologically, feces contain a diverse microbial community, with bacteria comprising 25–54% of the dry solids by biomass.[4] Dominant phyla include Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which together represent up to 80% of the identifiable fecal microbiota in healthy adults.[8] Additional components encompass dead epithelial cells sloughed from the intestinal lining, as well as potential parasites or pathogens depending on health status.[4] Physically, the color of feces varies based on its constituents; the characteristic brown hue results from stercobilin, an oxidation product of bilirubin produced by gut bacteria.[7] Green tones arise from unmetabolized bile pigments, while black discoloration can indicate digested blood from upper gastrointestinal bleeding.[9] Consistency ranges from soft and formed to hard and pellet-like, influenced by dietary fiber content and water retention, with higher fiber promoting bulkier stools.[9] The odor stems from volatile sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol, and dimethyl sulfide, alongside indole and skatole generated during protein fermentation.[10] Compositional and physical traits differ markedly by diet and species. In herbivores, such as rabbits, feces are often fibrous and pellet-shaped due to high cellulose intake, with hard pellets from the colon contrasting softer, bacteria-rich caecotrophs reingested for nutrient extraction.[9] Carnivores produce more compact, moist, and strongly odorous stools reflecting higher protein and fat residues, as seen in dogs.[11] Ruminants like cows yield large, moist pats rich in undigested plant fiber, while dietary shifts in omnivores, such as increased fiber, lead to softer consistency and altered microbial profiles favoring Bacteroidetes.[9][8]Formation Process

The formation of feces commences with the ingestion of food, which is mechanically fragmented in the mouth through mastication and mixed with saliva containing amylase to initiate carbohydrate digestion. Upon entering the stomach, the bolus is exposed to gastric acid and enzymes such as pepsin, which primarily break down proteins into smaller peptides, while peristalsis—a series of involuntary wave-like muscle contractions—mixes and propels the contents forward.[3][12] In the small intestine, the chyme receives pancreatic enzymes that further degrade carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, alongside bile secreted from the liver and gallbladder, which emulsifies dietary lipids to facilitate their enzymatic hydrolysis by lipases. This bile also contains bilirubin, a byproduct of red blood cell breakdown, which is later converted by intestinal bacteria into stercobilin, imparting the characteristic brown color to feces. Peristalsis continues to advance the semi-liquid mixture, enabling nutrient absorption while undigested residues, including fiber, proceed to the large intestine.[3][13][2] Within the large intestine, or colon, the residual material undergoes significant water and electrolyte absorption, transforming the liquid chyme into a compacted semisolid mass; this process is augmented by the gut microbiota, which ferment indigestible carbohydrates to produce short-chain fatty acids like acetate, propionate, and butyrate, serving as an energy source for colonocytes. Haustral contractions and mass movements, forms of peristalsis, slowly propel the contents toward the rectum over a typical transit time of 24 to 72 hours in humans, where final molding occurs as fecal matter is stored until defecation. The resulting output is a water-rich semisolid composed largely of undigested food remnants, bacteria, and sloughed intestinal cells.[14][15][16] Several factors influence this formation process, including hydration status, which affects stool consistency—sufficient fluid intake maintains softer output by limiting excessive water reabsorption, whereas dehydration promotes harder stools through heightened colonic absorption. Transit time variations also play a key role; prolonged retention in conditions like constipation leads to over-compaction and drier feces due to extended water extraction, while accelerated transit in diarrhea results in loose, watery output from inadequate absorption.[17][2] Cross-species comparisons reveal adaptations in digestive tract morphology that impact feces formation: carnivores typically feature shorter guts optimized for rapid processing of proteinaceous diets, yielding quicker feces production with minimal fermentation, in contrast to herbivores, whose elongated intestinal tracts support prolonged microbial breakdown of cellulose-rich plant material, resulting in bulkier, fiber-laden feces.[18]Biological Role

Physiology in Animals

In non-human animals, the production and expulsion of feces are tightly regulated by integrated neural and hormonal mechanisms to ensure efficient digestion and waste elimination. The enteric nervous system (ENS), often termed the "second brain," autonomously coordinates gastrointestinal motility, including the defecation reflex, through interconnected networks of neurons embedded in the gut wall. This reflex is primarily triggered by rectal distension, which activates mechanosensitive receptors and propagates signals via the ENS to relax the internal anal sphincter and contract the rectal smooth muscle, facilitating expulsion. Hormonal controls further modulate these processes by influencing intestinal transit and secretion. These mechanisms allow animals to adapt defecation timing to environmental cues, such as predator avoidance or foraging patterns. Adaptations in feces production vary across animal taxa, reflecting dietary and ecological pressures. In lagomorphs like rabbits, coprophagy involves the re-ingestion of soft cecotropes—nutrient-rich fecal pellets produced in the cecum—to recycle vitamins (e.g., B vitamins) and proteins that escape initial small intestine absorption, enhancing overall nutrient efficiency from fibrous plant matter. Canines, such as dogs and wolves, often use feces for scent-marking, depositing them strategically to communicate territory boundaries via volatile compounds, a behavior more pronounced in intact males and linked to social hierarchy maintenance. Lagomorphs also form dry, discrete fecal pellets in the colon, an adaptation that minimizes water loss and allows rapid deposition during flight responses, contrasting with the softer, clustered output in other herbivores. Evolutionarily, feces represent the residual byproduct of optimized nutrient extraction in the gut, enabling animals to maximize energy yield from limited resources while minimizing waste volume. This efficiency has driven adaptations like the dual fecal strategy in hindgut fermenters, where initial nutrient-poor hard feces are supplemented by reprocessed cecotropes for secondary fermentation. In birds, guano—the combined excretion of feces and uric acid-rich urine—serves as an evolutionary innovation for water conservation in arid or flight-dependent lifestyles, as uric acid requires less hydration for nitrogen elimination compared to urea in mammals, reducing overall body water loss during excretion. Pathophysiological variations in feces output often arise from dietary shifts or infections, particularly in livestock. Abrupt diet changes, such as increasing grain content in ruminant feeds, can elevate fecal moisture and volume due to altered rumen fermentation, leading to softer consistency and higher nutrient excretion. In calves, diseases causing scours (diarrhea) disrupt colonic absorption, resulting in watery feces laden with undigested electrolytes and pathogens like rotavirus or Escherichia coli, which exacerbate dehydration and reduce growth efficiency if untreated.Ecological Functions

Feces play a crucial role in nutrient cycling within ecosystems by returning essential elements such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon to the soil, thereby supporting plant growth and overall ecosystem productivity. In terrestrial environments, herbivore feces deposit these nutrients directly onto the ground, where they are broken down and incorporated into the soil through the activities of decomposers. For instance, dung beetles (Scarabaeinae) actively bury and fragment herbivore feces, accelerating the release of nitrogen and phosphorus while enhancing soil aeration and fertility, which in turn promotes vegetation regrowth in grasslands and forests.[19] In ruminant systems, feces from animals like cattle contribute significantly to phosphorus recycling.[20] Feces also support biodiversity by serving as a primary food source and habitat for coprophagous organisms, including insects, fungi, and bacteria. Over 7,000 species of dung beetles worldwide rely on vertebrate feces for feeding and reproduction, with their larvae developing within the material, thereby sustaining diverse arthropod communities that enhance ecosystem resilience.[21] These insects, along with dung flies and scarab beetles, facilitate the proliferation of fungi and bacteria that colonize feces, breaking down organic matter and creating microhabitats for parasites and other microbes; this microbial diversity aids in decomposition and prevents nutrient lockup in undigested waste.[19] In trophic interactions, feces mediate key ecological processes such as seed dispersal and predator-prey signaling. Many omnivorous and frugivorous animals, including birds and mammals, excrete viable seeds from consumed fruits in their droppings, enabling long-distance dispersal; for example, birds like thrushes spread berry seeds from species such as Rubus through endozoochory, with germination rates often improved by the digestive process, contributing to forest regeneration and plant population dynamics.[22] Additionally, fecal scents act as chemical signals in predator-prey dynamics, where prey detect predator feces as kairomones—odors that convey risk and trigger avoidance behaviors, such as reduced foraging in affected areas—while predators use their own fecal deposits to mark territories and attract conspecifics or prey through volatile compounds.[23] While feces generally enhance ecosystem health, excess accumulation from intensive animal farming can lead to environmental pollution, particularly through nutrient runoff that causes eutrophication in waterways. In concentrated livestock operations, unmanaged manure releases high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus, contributing to algal blooms and hypoxic zones in rivers and lakes.[24] Conversely, in restoration ecology, strategic use of wildlife feces in rewilding projects can aid habitat recovery by improving soil microbiota and properties; experiments in damaged ecosystems demonstrate that fecal inputs from native animals can increase soil carbon content and facilitate vegetation establishment and biodiversity rebound.[25]Human-Specific Aspects

Health Implications

Human feces serve as a primary vector for pathogen transmission through the fecal-oral route, where contaminated food, water, or hands facilitate the spread of infectious agents from the gastrointestinal tract of infected individuals to others. This route commonly transmits bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella, viruses including norovirus and hepatitis A, and protozoa like Giardia lamblia. [26] [27] [28] Historical epidemics, such as cholera outbreaks caused by Vibrio cholerae, exemplify the devastating public health impact of this transmission, with pandemics in the 19th and 20th centuries linked to poor sanitation and fecal contamination of water sources, resulting in millions of deaths worldwide. [29] [30] [31] Fecal analysis plays a crucial role in medical diagnostics for gastrointestinal conditions. The fecal occult blood test (FOBT) detects hidden blood in stool samples, serving as a key screening tool for colorectal cancer by identifying early signs of polyps or tumors that may bleed intermittently. [32] [33] Stool cultures identify bacterial pathogens responsible for infections, aiding in the diagnosis of conditions like salmonellosis or shigellosis through targeted microbial growth and identification. [34] [35] Additionally, measuring fecal calprotectin levels provides a non-invasive marker of intestinal inflammation, helping differentiate inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) from irritable bowel syndrome and monitoring disease activity in conditions such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. [36] [37] Therapeutically, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has emerged as an effective treatment for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections, where healthy donor feces restore gut microbial balance, with FDA-approved products like Rebyota demonstrating high cure rates in clinical trials. [38] [39] As of 2025, ongoing research explores FMT's potential for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), showing symptom improvements in pilot studies through microbiota modulation [40], and for autism spectrum disorder, where preliminary trials indicate behavioral benefits linked to gut-brain axis alterations, though larger randomized controlled trials are needed for validation. [41] [42] [43] Fecal examination also reveals nutritional insights, particularly in assessing malabsorption syndromes. Steatorrhea, characterized by excessive fat in feces (typically exceeding 7 grams per 24 hours), signals impaired fat digestion or absorption, often due to pancreatic insufficiency or celiac disease, and is diagnosed via quantitative fecal fat analysis. [44] [45] Furthermore, correlations between dietary fiber intake and fecal composition highlight its role in promoting gut health; higher fiber consumption is associated with increased microbial diversity and short-chain fatty acid production in the feces, reducing risks of chronic inflammation and supporting overall intestinal barrier function. [46] [47] [48]Management and Sanitation

The management and sanitation of feces have evolved significantly over time to mitigate public health risks and environmental contamination. Historically, sanitation practices relied on simple pit latrines, which date back thousands of years and were common in ancient civilizations for containing human waste. In the 19th century, amid rapid urbanization and cholera outbreaks in Europe and North America, innovations like the flush toilet gained prominence; for instance, the S-shaped trap invented by Alexander Cummings in 1775 and improved by Joseph Bramah in 1778 helped prevent sewer gases from entering homes, while widespread adoption accelerated after the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak in London highlighted the need for better sewage systems. By the late 1800s, public health reforms in cities like London and New York led to the construction of modern sewer networks connected to flush toilets, marking a shift from rudimentary pits to centralized wastewater infrastructure.[49] Despite these advancements, global disparities in sanitation access persist, particularly in low-income regions. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 2024, over 1.5 billion people lack basic sanitation services, such as private toilets or latrines, while 354 million still practice open defecation, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. These gaps contribute to the spread of fecal-oral pathogens, exacerbating diseases like diarrhea, which claims hundreds of thousands of lives annually. In contrast, high-income countries have near-universal access to improved facilities, underscoring inequities driven by economic and infrastructural barriers.[50] Modern sanitation systems emphasize treatment and resource recovery to safely process feces-laden wastewater. Centralized wastewater treatment plants, serving urban areas, employ processes like anaerobic digestion, where bacteria break down organic matter in the absence of oxygen to produce biogas for energy and stabilized biosolids, reducing pathogen loads by up to 99% in primary and secondary treatments. In rural or decentralized settings, septic systems collect and partially treat household wastewater in underground tanks, allowing solids to settle while liquids percolate into soil for natural filtration, though regular pumping is essential to prevent overflows. For sustainable alternatives, composting toilets use aerobic decomposition to convert feces and carbon additives into nutrient-rich compost, enabling resource recovery without water use and suitable for off-grid locations like remote cabins or disaster zones.[51][52][53] Public health strategies complement infrastructural efforts by targeting transmission pathways. Handwashing with soap after toilet use or before food preparation is a cornerstone intervention, reducing diarrheal disease incidence by 30-48% according to WHO analyses of community trials. Vaccinations against fecal-borne pathogens, such as rotavirus (recommended by WHO for infants worldwide since 2009) and cholera (via oral vaccines in endemic areas), provide targeted immunity and have averted millions of cases globally. Regulatory frameworks, like the U.S. Clean Water Act of 1972, enforce pollutant discharge limits through the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, mandating treatment standards for sewage to protect waterways from fecal contamination.[54][55] Key challenges in feces management include persistent open defecation and emerging threats like antimicrobial resistance. In developing regions, socioeconomic factors and inadequate infrastructure sustain open defecation, affecting 354 million people and perpetuating cycles of poverty and disease as per WHO estimates. Untreated sewage discharges contribute to antibiotic resistance by disseminating resistant bacteria and genes into aquatic environments, with CDC research indicating that human waste from communities with poor sanitation accelerates the spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens like extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producers. Addressing these requires integrated approaches, including scalable infrastructure investments and global surveillance.[50][56]Practical Uses

Fertilizer and Agriculture

Feces from both humans and animals have served as organic fertilizers in agriculture for thousands of years, recycling essential nutrients back into the soil. In ancient China, night soil—human excreta collected from urban areas—was widely applied to croplands as a nutrient-rich amendment, supporting intensive rice and vegetable production for over two millennia.[57] Similarly, in medieval Europe, animal manure was integral to the three-field crop rotation system, where it was spread across arable lands during the fallow period to replenish soil fertility and sustain higher yields of grains and legumes.[58] The nutrient content of feces makes it a valuable fertilizer, particularly due to its high levels of nitrogen (derived largely from urea), phosphorus, and potassium, which are critical for plant growth. Animal manures typically contain 70-80% available nitrogen, 60-85% available phosphorus, and 80-90% available potassium in the first year after application, varying by livestock type and diet.[59] Human feces provide comparable benefits, with typical concentrations on a dry matter basis of approximately 20–50 g/kg nitrogen, 10–30 g/kg phosphorus, and 10–20 g/kg potassium, though processing is required to optimize availability and safety.[60] These nutrients not only promote vigorous crop development but also enhance soil structure by increasing organic matter content.[61] Application methods for fecal fertilizers emphasize safety and efficacy, often involving preprocessing to minimize risks. Composting is a standard practice, where manure or night soil is piled and turned to achieve temperatures that kill pathogens while stabilizing nutrients; for instance, maintaining internal temperatures above 55°C for at least three days during active composting significantly reduces microbial hazards.[62] Direct spreading of fresh or aged manure is common on pastures, allowing grazing animals to naturally incorporate it into the soil. For human-derived materials, treated sewage sludge known as biosolids must comply with EPA Class A standards, which require processes like heat drying or pasteurization to reduce pathogens to undetectable levels before land application.[63] The use of feces as fertilizer offers substantial benefits for soil health, including improved nutrient retention, enhanced microbial activity, and increased crop productivity, thereby reducing reliance on synthetic inputs.[64] However, risks such as heavy metal contamination—particularly cadmium, zinc, and copper from industrial sources in sewage sludge—can lead to soil accumulation and potential uptake by plants, posing long-term environmental and health concerns.[65] Pathogen reduction during maturation, such as through 60-day composting periods that allow die-off under aerobic conditions, further mitigates these issues when properly managed.[66] Modern regulations balance agricultural benefits with environmental protection, particularly regarding overuse that could lead to water pollution. The European Union's Nitrates Directive restricts livestock manure application to 170 kg of nitrogen per hectare per year in designated nitrate vulnerable zones to curb leaching into groundwater. In sustainable systems like permaculture, manure integration with diverse cropping, cover plants, and composting promotes closed-loop nutrient cycling, mimicking natural ecological processes while minimizing waste.[67]Energy and Fuel Sources

Feces, particularly from humans and livestock, serve as a renewable energy source through processes like anaerobic digestion, which converts organic matter into biogas primarily composed of methane. In this process, bacteria break down the fecal material in oxygen-free environments within digesters, producing biogas that contains 50-70% methane, along with carbon dioxide and trace gases, which can be combusted for heat, electricity, or cooking fuel. This method harnesses the high organic content of feces, including undigested carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, to generate energy while reducing waste volume and pathogens. Early references to covered sewage pits in ancient China date back potentially over 2,000 years, but systematic biogas production and use began in the 20th century. In modern contexts, large-scale biogas plants in Denmark process millions of tons of livestock manure annually, generating electricity for over 100,000 households through centralized anaerobic digestion facilities that integrate fecal waste with agricultural residues. By 2023, India had installed approximately 5 million household biogas plants, many utilizing human and animal feces to provide clean cooking fuel for rural communities, supported by government subsidies to promote sustainable energy access. The efficiency of biogas production from feces varies by feedstock composition and digestion conditions, with approximately 1 kg of dry fecal matter yielding about 0.25 cubic meters of biogas, equivalent to roughly 0.5 kWh of energy. Byproducts include digestate, a nutrient-rich slurry that can be used as fertilizer, enhancing the overall sustainability of the process. However, challenges persist, such as high initial setup costs for digesters—often exceeding $1,000 per household unit—and variability in biogas yield due to differences in diet, moisture content, and microbial activity in the fecal feedstock. Applications involving human feces have gained traction in developing regions, with pilot projects like Sanergy in Kenya converting urine-diverting toilets' fecal sludge into biogas for community cooking and lighting in urban slums, processing over 10,000 tons annually. These initiatives often integrate with wastewater treatment systems, where fecal solids are separated and digested to produce biogas that offsets energy needs for the facilities themselves, as seen in decentralized plants in sub-Saharan Africa. Such efforts not only address energy poverty but also mitigate environmental pollution from untreated waste.Scientific and Archaeological Applications

Coprolites, or fossilized feces, serve as valuable archives in paleontology and archaeology, preserving undigested remains that reveal dietary habits, environmental conditions, and behaviors of ancient organisms. In human contexts, analysis of coprolites from Hidden Cave in western Nevada has provided evidence of prehistoric diets including seeds, nuts, and other plant materials, indicating seasonal occupation and resource use by early inhabitants dating back thousands of years. Similarly, paleofeces from the Paisley Caves in Oregon, dated to approximately 14,000 years ago via radiocarbon dating, contain macroscopic remains such as plant fragments and have yielded human DNA, supporting the presence of pre-Clovis populations and insights into early migrations into North America. These samples demonstrate how preserved feces can reconstruct paleodiets without relying on skeletal evidence. In paleontological studies, coprolites from extinct species offer direct evidence of trophic interactions. For instance, theropod dinosaur coprolites from the Late Cretaceous often contain bone fragments and fish scales, confirming carnivorous or piscivorous diets and digestive capabilities through microscopic examination of inclusions. Paleofeces analysis extends to extinct mammals and birds, where pollen and spore counts via microscopy reveal floral communities and seasonal foraging patterns. Advanced techniques, such as ancient DNA sequencing, further identify consumed species and gut microbiomes, enhancing phylogenetic and ecological reconstructions. Methodologies for coprolite and paleofeces research include radiocarbon dating to establish chronological frameworks, often applied to organic components like plant residues. Pollen and phytolith analysis under microscopy identifies specific vegetation types, while stable isotope ratios—particularly carbon (δ¹³C)—distinguish between C₃ pathway plants (e.g., trees and shrubs, with more negative ratios around -28‰) and C₄ grasses (less negative, around -12‰), enabling diet reconstructions in varied ecosystems. These approaches have been pivotal in studies of megafaunal extinctions and human adaptations. In modern forensics, feces function as trace evidence in criminal investigations, with DNA profiling linking suspects to scenes through fecal deposits on clothing or objects. For example, mitochondrial DNA from canine feces has matched samples from crime scenes to suspects' shoes, aiding in murder reconstructions. Forensic entomology utilizes insect succession on feces to estimate the postmortem interval or time since deposition; blowflies and beetles colonize fecal matter rapidly, and larval development stages provide timelines accurate to within days, particularly useful in outdoor or animal-related cases.Medicinal and Other Uses

In ancient Egyptian medicine, powdered feces mixed with honey were applied as an ointment to treat eye conditions such as trachoma and conjunctivitis, leveraging the antibiotic properties inherent in fecal matter.[68][69] Similarly, in Ayurvedic practices, cow dung poultices, often combined with herbs like neem leaves, have been used traditionally to alleviate skin ailments including boils, heat rashes, and irritations due to their purported antibacterial and detoxifying effects.[70][71] Historically, mixtures of urine and animal feces were employed in leather tanning processes to soften hides by breaking down proteins through enzymatic action from the organic matter, a method used by Romans and medieval tanners that contributed to the industry's notorious odors.[72][73] In contemporary India, stabilized cow dung is processed into eco-friendly handmade paper by pulping the fibrous residue and blending it with recycled materials, producing durable sheets for stationery and packaging while reducing deforestation.[74] Additionally, animal dung serves as a binder in adobe construction, where it is mixed with clay, sand, and straw to enhance brick cohesion and water resistance in traditional earthen buildings across various cultures.[75][76] Emerging biotechnological applications include the isolation of probiotic strains from fecal microbiota, such as certain Lactobacillus species, which exhibit beneficial properties like acid tolerance and pathogen inhibition, supporting developments in gut health supplements.[77][78] Fecal matter also indirectly aids sustainable material innovation, as mycelium-based leather alternatives are cultivated on agro-waste substrates including dung-derived organic refuse, yielding biodegradable textiles with leather-like texture.[79] These probiotics relate briefly to fecal microbiota transplantation techniques for restoring gut balance, though such medical procedures extend beyond direct fecal uses here.[80] Animal-specific applications highlight feces' versatility; elephant dung, rich in undigested plant fibers, is pulped and formed into high-quality handmade paper in regions like Sri Lanka and Uganda, creating textured, chemical-free products for artisanal goods.[81][82] Research on giant panda feces has identified unique microbial enzymes capable of efficiently degrading lignocellulosic biomass, informing biotech efforts to develop industrial enzymes for applications like waste processing, with studies ongoing as of recent analyses.[83][84]Terminology

Etymology

The word "feces" originates from the Latin term faex, meaning "dregs" or "sediment," with the plural form faeces referring to the grounds or lees left after liquids settle, such as in wine or other substances.[85] This root entered Middle English around the early 15th century, initially denoting non-biological residues in alchemical and medical contexts, as seen in texts like the Book of Quinte Essence before 1475.[86] By the 17th century, specifically circa 1625–1630, the term shifted to describe human excrement, reflecting its adaptation in scientific writing to distinguish it from earlier, more general English words like "excrement," which derived from Latin excrementum meaning "that which is strained out."[87][85] In English medical nomenclature, "feces" formalized discussions of bodily waste, influenced by Greek roots such as skatos (excrement or dung), which contributed to compound terms like "scatology" for the study of feces, emphasizing a precise, classical foundation in biology.[88] This linguistic evolution paralleled broader transitions from alchemical uses—where faex described impurities in mixtures—to biological applications in anatomy and physiology texts by the 18th century. Cross-language parallels trace directly to the Latin source: in French, fèces (plural) retains the original sense of sediment depositing in liquids, borrowed from Latin faeces and used archaically in pharmacy. Similarly, Spanish heces, the plural of hez, evolved from faex to denote both lees and fecal matter, with usage shifting from winemaking residues to medical descriptions of waste by the Renaissance.[89] During the 19th-century Victorian era, societal taboos and euphemisms—such as "night soil" for human waste collected from privies—prompted the increased formal adoption of "feces" in medical literature, allowing professionals to discuss sanitation and health objectively amid cultural reticence toward direct references to excretion.[90] This clinical preference positioned "feces" as a formal alternative to synonyms like "stools" or "evacuations" in emerging fields like public hygiene and coprology.[91]Synonyms and Regional Variations

In scientific literature, feces is often interchangeably referred to as excrement, denoting the solid or semisolid waste expelled from the digestive tract of animals, including humans.[92] Another formal synonym is ordure, a term historically used for animal or human dung, emphasizing its foul nature in older texts.[93] In medical contexts, stools specifically describes human fecal matter, as observed in clinical assessments of bowel health.[94] For wildlife studies, scat serves as a key term for the feces of non-human animals, employed in tracking species like mammals and aiding ecological research; it derives from Greek roots denoting excrement.[95][96] Colloquial and regional variations reflect cultural nuances and often employ child-friendly or informal language. In American and British English, poop is a widespread childish term for feces, softening the reference in everyday speech.[97] Across Spanish-speaking regions and in Portuguese, caca functions similarly as a playful or euphemistic word for excrement, commonly used with children.[98] In German, the slang Kacke, derived from the verb kacken meaning "to defecate," denotes feces in casual or mildly vulgar contexts.[99] Scandinavian languages feature kaka (or variants like kakka in Swedish and Norwegian) as a colloquial, often infantile term for poop, appearing in dialects across Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.[98] Animal-specific nomenclature distinguishes feces by species or habitat, facilitating specialized fields like ecology and agriculture. Guano refers to the accumulated droppings of bats or seabirds, prized for its phosphate-rich composition in fertilizer production.[100] Insect excrement is termed frass, typically appearing as powdery residue from herbivores like caterpillars, useful in entomological identification.[101] Birds produce droppings, a general term encompassing their semisolid waste, which mixes uric acid with fecal matter.[92] In veterinary and agricultural contexts, terminology differentiates based on application and species to avoid confusion with human references. Feces is the standard scientific term across animals, while manure specifically applies to livestock waste, often blended with urine and bedding materials for soil amendment in farming.[102][103] This contrasts with stool, reserved for human output in medical diagnostics, ensuring precision in professional discussions.[94]Cultural and Social Dimensions

Disgust and Taboos

Disgust toward feces is a fundamental human emotion rooted in evolutionary adaptations for disease avoidance. Psychologists Paul Rozin and April Fallon proposed that disgust originated as a mechanism to prevent the ingestion of harmful substances, with feces serving as a prototypical trigger due to its association with pathogens and contamination risks.[104] This response is considered part of the "behavioral immune system," an innate system that promotes avoidance behaviors to reduce infection exposure, as evidenced by cross-species parallels in rejection of foul substances.[105] Rozin and colleagues further identified feces as a universal disgust elicitor in adults across cultures, distinguishing it from mere distaste by evoking visceral revulsion linked to decay and mortality reminders.[106] Psychological research underscores the intensity of fecal disgust compared to other bodily wastes. In a seminal framework, Rozin and Fallon described disgust as revulsion at the prospect of oral incorporation of offensive items, with feces rated highest in offensiveness due to its symbolic contamination potential.[104] Cross-cultural studies confirm this potency; for example, a comparison between Ghana and the United States found mean disgust ratings of 3.7–4.5 on a 0–6 scale for fecal-related scenarios like touching dog feces.[107] These findings highlight feces' role in core disgust domains, often amplified by olfactory cues, and demonstrate consistency across diverse populations despite variations in other elicitors.[108] Cultural taboos amplify this innate aversion through religious and societal norms. In Hinduism, ancient texts like the Manusmriti prescribe ritual purity laws that prohibit contact with feces, viewing it as a source of impurity (ashaucha) that requires ablution with water to restore sanctity, reinforcing social hierarchies tied to cleanliness.[109] Islamic teachings emphasize hygiene via istinja, the mandatory washing of the anus with water after defecation, as outlined in hadiths, with feces deemed najis (impure) and contact necessitating purification to avoid spiritual contamination.[110] In historical Europe, particularly during the medieval period, poor urban sanitation—such as emptying chamber pots into streets—fostered widespread stigma and public health crises, with feces symbolizing moral and social decay amid outbreaks like the Black Death, though attitudes reflected disgust rather than outright religious bans.[111] In modern contexts, taboos persist in public discourse but diminish in professional medical settings. Healthcare providers, such as midwives and nurses, routinely handle feces during procedures like childbirth or incontinence care, where exposure is normalized through training to override personal disgust for patient welfare.[112] For example, midwifery discussions reveal that while societal aversion remains strong, clinical necessity fosters desensitization, though stigma around fecal incontinence still hinders open patient-provider communication.[113] This contrast illustrates how evolutionary and cultural factors maintain broad aversion, yet pragmatic needs in healthcare create localized exceptions.[114]Representations in Media and Humor

Scatological humor, involving references to feces and bodily functions, has long been a staple in folklore and literature, often serving to subvert social norms through exaggeration and absurdity. In Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, particularly "The Miller's Tale" (c. 1387–1400), scatological elements are central to the comedic plot, culminating in a scene where a character farts in another's face as a form of revenge, aligning with the fabliau tradition of bawdy, lowbrow tales that mock pretension.[115] Similarly, Jonathan Swift employed scatological satire in works like "The Lady's Dressing Room" (1732), where a suitor discovers the mundane and repulsive realities of his beloved's excretions, critiquing idealized romance and human vanity through grotesque imagery.[116] In modern media, feces-related gags continue this tradition, amplified for visual and shock value in comedy. Stand-up comedian George Carlin frequently riffed on defecation in routines such as "Take a Shit" from his 1986 special Playing with Your Head, humorously dissecting the euphemisms and rituals surrounding bathroom habits to highlight linguistic absurdities.[117] Films like Dumb and Dumber (1994) feature iconic scatological scenes, including one where protagonist Harry Dunne causes a toilet overflow with excessive feces, turning a mundane mishap into slapstick chaos that underscores the characters' incompetence.[118] Animated series such as South Park have elevated poop humor to recurring motifs, with episodes like "Mr. Hankey, the Christmas Poo" (1997) introducing a sentient feces character who sings holiday songs, satirizing censorship and holiday cheer through absurd anthropomorphism.[119] Social media has democratized scatological content, transforming it into viral, participatory trends that blend humor with relatability. The poop emoji (💩), introduced in 1997 but surging in popularity during the 2020s, symbolizes everything from literal messes to ironic failures as a lighthearted shorthand in internet culture.[120] Challenges like the #PoopChallenge, which gained traction on TikTok and Twitter in 2020, involve parents pranking children by smearing fake feces (often peanut butter) on their hands and filming reactions, amassing millions of views for its harmless, family-oriented shock value.[121] Influencers further normalize discussions by sharing personal gut health stories, such as destigmatizing irregular bowel movements on platforms like Instagram, where creators like The Bird's Papaya advocate for open conversations about poop to reduce shame around digestive issues.[122] These representations reflect broader cultural shifts, evolving from 20th-century taboo-breaking in comedy—where scatology challenged Victorian prudery through vaudeville and early films—to contemporary normalization via health advocacy. In the 21st century, humor has increasingly intersected with awareness, as seen in 2024 campaigns like Queensland Health's "It's okay to poo at work," which uses playful videos to encourage employees with IBS to prioritize bathroom breaks, reducing stigma around fecal urgency.[123] Similarly, Guts UK's partnership with Imodium in 2024 promoted "flushing away the poo taboo" through humorous social media posts, fostering solidarity among those affected by gut disorders.[124] This progression illustrates how scatological elements in media now balance levity with education, mirroring societal moves toward destigmatizing bodily functions.[125]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/heces