Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fossil

View on Wikipedia

A fossil (from Classical Latin fossilis, lit. 'obtained by digging')[1] is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved in amber, hair, petrified wood and DNA remnants. The totality of fossils is known as the fossil record. Though the fossil record is incomplete, numerous studies have demonstrated that there is enough information available to give a good understanding of the pattern of diversification of life on Earth.[2][3][4] In addition, the record can predict and fill gaps such as the discovery of Tiktaalik in the arctic of Canada.[5]

Paleontology includes the study of fossils: their age, method of formation, and evolutionary significance. Specimens are sometimes considered to be fossils if they are over 10,000 years old.[6][7][8] The oldest fossils are around 3.48 billion years [9][10][11] to 4.1 billion years old.[12][13] The observation in the 19th century that certain fossils were associated with certain rock strata led to the recognition of a geological timescale and the relative ages of different fossils. The development of radiometric dating techniques in the early 20th century allowed scientists to quantitatively measure the absolute ages of rocks and the fossils they host.

There are many processes that lead to fossilization, including permineralization, casts and molds, authigenic mineralization, replacement and recrystallization, adpression, carbonization, and bioimmuration.

Fossils vary in size from one-micrometre (1 μm) bacteria[14] to dinosaurs and trees, many meters long and weighing many tons. The largest presently known is a Sequoia sp. measuring 88 m (289 ft) in length at Coaldale, Nevada.[15] A fossil normally preserves only a portion of the deceased organism, usually that portion that was partially mineralized during life, such as the bones and teeth of vertebrates, or the chitinous or calcareous exoskeletons of invertebrates. Fossils may also consist of the marks left behind by the organism while it was alive, such as animal tracks or feces (coprolites). These types of fossil are called trace fossils or ichnofossils, as opposed to body fossils. Some fossils are biochemical and are called chemofossils or biosignatures.

| Part of a series on |

| Paleontology |

|---|

|

History of study

[edit]Gathering fossils dates at least to the beginning of recorded history. The fossils themselves are referred to as the fossil record. The fossil record was one of the early sources of data underlying the study of evolution and continues to be relevant to the history of life on Earth. Paleontologists examine the fossil record to understand the process of evolution and the way particular species have evolved.

Ancient civilizations

[edit]

Fossils have been visible and common throughout most of natural history, and so documented human interaction with them goes back as far as recorded history, or earlier.

There are many examples of Paleolithic stone knives in Europe, with fossil echinoderms set precisely at the hand grip, dating back to Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals.[16] These ancient peoples also drilled holes through the center of those round fossil shells, apparently using them as beads for necklaces.

The ancient Egyptians gathered fossils of species that resembled the bones of modern species they worshipped. The god Set was associated with the hippopotamus, therefore fossilized bones of hippo-like species were kept in that deity's temples.[17] Five-rayed fossil sea urchin shells were associated with the deity Sopdu, the Morning Star, equivalent of Venus in Roman mythology.[16]

Fossils appear to have directly contributed to the mythology of many civilizations, including the ancient Greeks. Classical Greek historian Herodotos wrote of an area near Hyperborea where gryphons protected golden treasure. There was indeed gold mining in that approximate region, where beaked Protoceratops skulls were common as fossils.

A later Greek scholar, Aristotle, eventually realized that fossil seashells from rocks were similar to those found on the beach, indicating the fossils were once living animals. He had previously explained them in terms of vaporous exhalations,[18] which Persian polymath Avicenna modified into the theory of petrifying fluids (succus lapidificatus). Recognition of fossil seashells as originating in the sea was built upon in the 14th century by Albert of Saxony, and accepted in some form by most naturalists by the 16th century.[19]

Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote of "tongue stones", which he called glossopetra. These were fossil shark teeth, thought by some classical cultures to look like the tongues of people or snakes.[20] He also wrote about the horns of Ammon, which are fossil ammonites, whence the group of shelled octopus-cousins ultimately draws its modern name. Pliny also makes one of the earlier known references to toadstones, thought until the 18th century to be a magical cure for poison originating in the heads of toads, but which are fossil teeth from Lepidotes, a Cretaceous ray-finned fish.[21]

The Plains tribes of North America are thought to have similarly associated fossils, such as the many intact pterosaur fossils naturally exposed in the region, with their own mythology of the thunderbird.[22]

There is no such direct mythological connection known from prehistoric Africa, but there is considerable evidence of tribes there excavating and moving fossils to ceremonial sites, apparently treating them with some reverence.[23]

In Japan, fossil shark teeth were associated with the mythical tengu, thought to be the razor-sharp claws of the creature, documented some time after the 8th century AD.[20]

In medieval China, the fossil bones of ancient mammals including Homo erectus were often mistaken for "dragon bones" and used as medicine and aphrodisiacs. In addition, some of these fossil bones are collected as "art" by scholars, who left scripts on various artifacts, indicating the time they were added to a collection. One good example is the famous scholar Huang Tingjian of the Song dynasty during the 11th century, who kept a specific seashell fossil with his own poem engraved on it.[24] In his Dream Pool Essays published in 1088, Song dynasty Chinese scholar-official Shen Kuo hypothesized that marine fossils found in a geological stratum of mountains located hundreds of miles from the Pacific Ocean was evidence that a prehistoric seashore had once existed there and shifted over centuries of time.[25][26] His observation of petrified bamboos in the dry northern climate zone of what is now Yan'an, Shaanxi province, China, led him to advance early ideas of gradual climate change due to bamboo naturally growing in wetter climate areas.[26][27][28]

In medieval Christendom, fossilized sea creatures on mountainsides were seen as proof of the biblical deluge of Noah's Ark. After observing the existence of seashells in mountains, the ancient Greek philosopher Xenophanes (c. 570 – 478 BC) speculated that the world was once inundated in a great flood that buried living creatures in drying mud.[29][30]

In 1027, the Persian Avicenna explained fossils' stoniness in The Book of Healing:

If what is said concerning the petrifaction of animals and plants is true, the cause of this (phenomenon) is a powerful mineralizing and petrifying virtue which arises in certain stony spots, or emanates suddenly from the earth during earthquake and subsidences, and petrifies whatever comes into contact with it. As a matter of fact, the petrifaction of the bodies of plants and animals is not more extraordinary than the transformation of waters.[31]

From the 13th century to the present day, scholars pointed out that the fossil skulls of Deinotherium giganteum, found in Crete and Greece, might have been interpreted as being the skulls of the Cyclopes of Greek mythology, and are possibly the origin of that Greek myth.[32][33] Their skulls appear to have a single eye-hole in the front, just like their modern elephant cousins, though in fact it's actually the opening for their trunk.

In Norse mythology, echinoderm shells (the round five-part button left over from a sea urchin) were associated with the god Thor, not only being incorporated in thunderstones, representations of Thor's hammer and subsequent hammer-shaped crosses as Christianity was adopted, but also kept in houses to garner Thor's protection.[16]

These grew into the shepherd's crowns of English folklore, used for decoration and as good luck charms, placed by the doorway of homes and churches.[34] In Suffolk, a different species was used as a good-luck charm by bakers, who referred to them as fairy loaves, associating them with the similarly shaped loaves of bread they baked.[35][36]

Early modern explanations

[edit]

More scientific views of fossils emerged during the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci concurred with Aristotle's view that fossils were the remains of ancient life.[37]: 361 For example, Leonardo noticed discrepancies with the biblical flood narrative as an explanation for fossil origins:

If the Deluge had carried the shells for distances of three and four hundred miles from the sea it would have carried them mixed with various other natural objects all heaped up together; but even at such distances from the sea we see the oysters all together and also the shellfish and the cuttlefish and all the other shells which congregate together, found all together dead; and the solitary shells are found apart from one another as we see them every day on the sea-shores.

And we find oysters together in very large families, among which some may be seen with their shells still joined together, indicating that they were left there by the sea and that they were still living when the strait of Gibraltar was cut through. In the mountains of Parma and Piacenza multitudes of shells and corals with holes may be seen still sticking to the rocks....[38]

In 1666, Nicholas Steno examined a shark, and made the association of its teeth with the "tongue stones" of ancient Greco-Roman mythology, concluding that those were not in fact the tongues of venomous snakes, but the teeth of some long-extinct species of shark.[20]

Robert Hooke (1635–1703) included micrographs of fossils in his Micrographia and was among the first to observe fossil forams. His observations on fossils, which he stated to be the petrified remains of creatures some of which no longer existed, were published posthumously in 1705.[39]

William Smith (1769–1839), an English canal engineer, observed that rocks of different ages (based on the law of superposition) preserved different assemblages of fossils, and that these assemblages succeeded one another in a regular and determinable order. He observed that rocks from distant locations could be correlated based on the fossils they contained. He termed this the principle of faunal succession. This principle became one of Darwin's chief pieces of evidence that biological evolution was real.

Georges Cuvier came to believe that most if not all the animal fossils he examined were remains of extinct species. This led Cuvier to become an active proponent of the geological school of thought called catastrophism. Near the end of his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants he said:

All of these facts, consistent among themselves, and not opposed by any report, seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.[40]

Interest in fossils, and geology more generally, expanded during the early nineteenth century. In Britain, Mary Anning's discoveries of fossils, including the first complete ichthyosaur and a complete plesiosaurus skeleton, sparked both public and scholarly interest.[41]

Linnaeus and Darwin

[edit]Early naturalists well understood the similarities and differences of living species leading Linnaeus to develop a hierarchical classification system still in use today. Darwin and his contemporaries first linked the hierarchical structure of the tree of life with the then very sparse fossil record. Darwin eloquently described a process of descent with modification, or evolution, whereby organisms either adapt to natural and changing environmental pressures, or they perish.

When Darwin wrote On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, the oldest animal fossils were those from the Cambrian Period, now known to be about 540 million years old. He worried about the absence of older fossils because of the implications on the validity of his theories, but he expressed hope that such fossils would be found, noting that: "only a small portion of the world is known with accuracy." Darwin also pondered the sudden appearance of many groups (i.e. phyla) in the oldest known Cambrian fossiliferous strata.[42]

After Darwin

[edit]Since Darwin's time, the fossil record has been extended to between 2.3 and 3.5 billion years.[43] Most of these Precambrian fossils are microscopic bacteria or microfossils. However, macroscopic fossils are now known from the late Proterozoic. The Ediacara biota (also called Vendian biota) dating from 575 million years ago collectively constitutes a richly diverse assembly of early multicellular eukaryotes.

The fossil record and faunal succession form the basis of the science of biostratigraphy or determining the age of rocks based on embedded fossils. For the first 150 years of geology, biostratigraphy and superposition were the only means for determining the relative age of rocks. The geologic time scale was developed based on the relative ages of rock strata as determined by the early paleontologists and stratigraphers.

Since the early years of the twentieth century, absolute dating methods, such as radiometric dating (including potassium/argon, argon/argon, uranium series, and, for very recent fossils, radiocarbon dating) have been used to verify the relative ages obtained by fossils and to provide absolute ages for many fossils. Radiometric dating has shown that the earliest known stromatolites are over 3.4 billion years old.

Modern era

[edit]The fossil record is life's evolutionary epic that unfolded over four billion years as environmental conditions and genetic potential interacted in accordance with natural selection.

Paleontology has joined with evolutionary biology to share the interdisciplinary task of outlining the tree of life, which inevitably leads backwards in time to Precambrian microscopic life when cell structure and functions evolved. Earth's deep time in the Proterozoic and deeper still in the Archean is only "recounted by microscopic fossils and subtle chemical signals."[45] Molecular biologists, using phylogenetics, can compare protein amino acid or nucleotide sequence homology (i.e., similarity) to evaluate taxonomy and evolutionary distances among organisms, with limited statistical confidence. The study of fossils, on the other hand, can more specifically pinpoint when and in what organism a mutation first appeared. Phylogenetics and paleontology work together in the clarification of science's still dim view of the appearance of life and its evolution.[46]

Niles Eldredge's study of the Phacops trilobite genus supported the hypothesis that modifications to the arrangement of the trilobite's eye lenses proceeded by fits and starts over millions of years during the Devonian.[47] Eldredge's interpretation of the Phacops fossil record was that the aftermaths of the lens changes, but not the rapidly occurring evolutionary process, were fossilized. This and other data led Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge to publish their seminal paper on punctuated equilibrium in 1971.

Synchrotron X-ray tomographic analysis of early Cambrian bilaterian embryonic microfossils yielded new insights of metazoan evolution at its earliest stages. The tomography technique provides previously unattainable three-dimensional resolution at the limits of fossilization. Fossils of two enigmatic bilaterians, the worm-like Markuelia and a putative, primitive protostome, Pseudooides, provide a peek at germ layer embryonic development. These 543-million-year-old embryos support the emergence of some aspects of arthropod development earlier than previously thought in the late Proterozoic. The preserved embryos from China and Siberia underwent rapid diagenetic phosphatization resulting in exquisite preservation, including cell structures.[jargon] This research is a notable example of how knowledge encoded by the fossil record continues to contribute otherwise unattainable information on the emergence and development of life on Earth. For example, the research suggests Markuelia has closest affinity to priapulid worms, and is adjacent to the evolutionary branching of Priapulida, Nematoda and Arthropoda.[48][jargon]

Despite significant advances in uncovering and identifying paleontological specimens, it is generally accepted that the fossil record is vastly incomplete.[49][50] Approaches for measuring the completeness of the fossil record have been developed for numerous subsets of species, including those grouped taxonomically,[51][52] temporally,[53] environmentally/geographically,[54] or in sum.[55][56] This encompasses the subfield of taphonomy and the study of biases in the paleontological record.[57][58][59]

Dating/Age

[edit]Stratigraphy and estimations

[edit]

Paleontology seeks to map out how life evolved across geologic time. A substantial hurdle is the difficulty of working out fossil ages. Beds that preserve fossils typically lack the radioactive elements needed for radiometric dating. This technique is our only means of giving rocks greater than about 50 million years old an absolute age, and can be accurate to within 0.5% or better.[60] Although radiometric dating requires careful laboratory work, its basic principle is simple: the rates at which various radioactive elements decay are known, and so the ratio of the radioactive element to its decay products shows how long ago the radioactive element was incorporated into the rock. Radioactive elements are common only in rocks with a volcanic origin, and so the only fossil-bearing rocks that can be dated radiometrically are volcanic ash layers, which may provide termini for the intervening sediments.[60]

Consequently, palaeontologists rely on stratigraphy to date fossils. Stratigraphy is the science of deciphering the "layer-cake" that is the sedimentary record.[61] Rocks normally form relatively horizontal layers, with each layer younger than the one underneath it. If a fossil is found between two layers whose ages are known, the fossil's age is claimed to lie between the two known ages.[62] Because rock sequences are not continuous, but may be broken up by faults or periods of erosion, it is very difficult to match up rock beds that are not directly adjacent. However, fossils of species that survived for a relatively short time can be used to match isolated rocks: this technique is called biostratigraphy. For instance, the conodont Eoplacognathus pseudoplanus has a short range in the Middle Ordovician period.[63] If rocks of unknown age have traces of E. pseudoplanus, they have a mid-Ordovician age. Such index fossils must be distinctive, be globally distributed and occupy a short time range to be useful. Misleading results are produced if the index fossils are incorrectly dated.[64] Stratigraphy and biostratigraphy can in general provide only relative dating (A was before B), which is often sufficient for studying evolution. However, this is difficult for some time periods, because of the problems involved in matching rocks of the same age across continents.[64] Family-tree relationships also help to narrow down the date when lineages first appeared. For instance, if fossils of B or C date to X million years ago and the calculated "family tree" says A was an ancestor of B and C, then A must have evolved earlier.

It is also possible to estimate how long ago two living clades diverged (i.e., the age of their last common ancestor) by assuming that mutations accumulate at a constant rate for a given gene. These "molecular clocks", however, are fallible, and provide only approximate timing: for example, they are not sufficiently precise and reliable for estimating when the groups that feature in the Cambrian explosion first evolved,[65] and estimates produced by different techniques may vary by a factor of two.[66]

Limitations

[edit]Organisms are only rarely preserved as fossils in the best of circumstances, and only a fraction of such fossils have been discovered. This is illustrated by the fact that the number of species known through the fossil record is less than 5% of the number of known living species, suggesting that the number of species known through fossils must be far less than 1% of all the species that have ever lived.[67] Because of the specialized and rare circumstances required for a biological structure to fossilize, only a small percentage of life-forms can be expected to be represented in discoveries, and each discovery represents only a snapshot of the process of evolution. The transition itself can only be illustrated and corroborated by transitional fossils, which are never guaranteed to demonstrate a convenient half-way point.[68]

The fossil record is strongly biased toward organisms with hard parts, leaving most groups of soft-bodied organisms with little to no presence.[67] It is replete with mollusks, vertebrates, echinoderms, brachiopods, and some groups of arthropods.[69]

Sites

[edit]Lagerstätten

[edit]Fossil sites with exceptional preservation—sometimes including preserved soft tissues—are known as Lagerstätten (German for "storage places"). These formations may have resulted from carcass burial in an anoxic environment with minimal bacteria, thus slowing decomposition. Lagerstätten span geological time from the Cambrian period to the present. Worldwide, some of the best examples of near-perfect fossilization are the Cambrian Maotianshan Shales and Burgess Shale, the Devonian Hunsrück Slates, the Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone, and the Carboniferous Mazon Creek localities.

Fossilization processes

[edit]Recrystallization

[edit]A fossil is said to be recrystallized when the original skeletal compounds are still present but in a different crystal form, such as from aragonite to calcite.[70]

-

Calcite-recrystallized fossil shell of Busycon sp. from Indrio Pit

-

Recrystallized bivalve shell with sparry calcite from Bird Spring Formation

Replacement

[edit]

Replacement occurs when the shell, bone, or other tissue is replaced with another mineral. In some cases mineral replacement of the original shell occurs so gradually and at such fine scales that microstructural features are preserved despite the total loss of original material. Scientists can use such fossils when researching the anatomical structure of ancient species.[71] Several species of saurids have been identified from mineralized dinosaur fossils.[72][73]

Permineralization

[edit]Permineralization is a process of fossilization that occurs when an organism is buried. The empty spaces within an organism (spaces filled with liquid or gas during life) become filled with mineral-rich groundwater. Minerals precipitate from the groundwater, occupying the empty spaces. This process can occur in very small spaces, such as within the cell wall of a plant cell, and can produce very detailed fossils at small scales.[74] For permineralization to occur, the organism must become covered by sediment soon after death, otherwise the remains are destroyed by scavengers or decomposition.[75] The degree to which the remains are decayed when covered determines the later details of the fossil. Some fossils consist only of skeletal remains or teeth; other fossils contain traces of skin, feathers or even soft tissues.[76] This is a form of diagenesis.

Phosphatization

[edit]Phosphatization refers to a process of fossilization where organic matter is replaced by abundant calcium-phosphate minerals. The produced fossils tend to be particularly dense and have a dark coloration that ranges from dark orange to black.[77]

Pyritization

[edit]This fossil preservation involves the elements sulfur and iron. Organisms may become pyritized when they are in marine sediments saturated with iron sulfides. As organic matter decays, it releases sulfide which reacts with dissolved iron in the surrounding waters, forming pyrite. Pyrite replaces carbonate shell material due to an undersaturation of carbonate in the surrounding waters. Some plants become pyritized when they are in a clay terrain, but to a lesser extent than in a marine environment. Some pyritized fossils include Precambrian microfossils, marine arthropods, and plants.[78][79]

-

Pyritized ammonoid Pleuroceras solare fossil specimen

-

Pyritized specimen of the brachiopod Paraspirifer bownockeri

-

Pyritized Triarthrus eatoni from Whetstone Gulf Formation

-

Pyritized Furcaster paleozoicus from Hunsrück Slate

-

Pyritized Tornoceras uniangulare from Ludlowville Formation

Silicification

[edit]In silicification, the precipitation of silica from saturated water bodies is responsible for the fossil's formation and preservation. The mineral-laden water permeates the pores and cells of some dead organism, where it becomes a gel. Over time, the gel will dehydrate, forming a silica-rich crystal structure, which can be expressed in the form of quartz, chalcedony, agate, opal, among others, with the shape of the original remain.[80][81]

-

Chalcedony replaced fossil shells of Elimia tenera with inclusions of ostracods

-

Chalcedonized gastropods internal molds

-

Agatized internal molds of gastropods from Deccan Traps

-

Agatized fossil coral from Florida

-

Fossil bivalves replaced by opal, from Queensland

-

Rear view of an opalized Addyman Plesiosaur fossil at the South Australian Museum

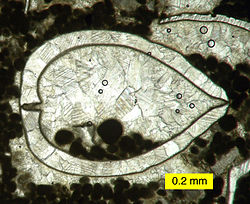

Casts and molds

[edit]In some cases, the original remains of the organism completely dissolve or are otherwise destroyed. The remaining organism-shaped hole in the rock is called an external mold. If this void is later filled with sediment, the resulting cast resembles what the organism looked like. An endocast, or internal mold, is the result of sediments filling an organism's interior, such as the inside of a bivalve or snail or the hollow of a skull.[82] Endocasts are sometimes termed Steinkerns, especially when bivalves are preserved this way.[83]

The term "cast" is also used in a different context for human-made replicas of fossils. A cast-maker pours silicone rubber over an original fossil to capture its form. Once removed, the silicone acts as a mold to be refilled with a liquid such as plaster, which hardens into a plaster cast. Many fossils are too fragile to safely display or transport, and casts allow their anatomical details to become available to other museums or public exhibits. More recent technologies such as 3D printing serve a similar purpose.

-

Internal mold (steinkern) of Hormotoma sp. from Galena Formation

-

Gastropod internal mold (steinkern) from Ventana Formation

-

Shell external mold of Anomalodonta gigantea from Waynesville Formation

-

Internal mold (steinkern) of Glycymeris alpinus, Austria

-

External mold of the dicynodont therapsid Gordonia traquairi from the Late Permian Hopeman Sandstone Formation, Scotland

Authigenic mineralization

[edit]This is a special form of cast and mold formation. If the chemistry is right, the organism (or fragment of organism) can act as a nucleus for the precipitation of minerals such as siderite, resulting in a nodule forming around it. If this happens rapidly before significant decay to the organic tissue, very fine three-dimensional morphological detail can be preserved. Nodules from the Carboniferous Mazon Creek fossil beds of Illinois, US, are among the best documented examples of such mineralization.[84]

Adpression (compression-impression)

[edit]Compression fossils, such as those of fossil ferns, are the result of chemical reduction of the complex organic molecules composing the organism's tissues. In this case, the fossil consists of original material, albeit in a geochemically altered state. This chemical change is an example of diagenesis. What remains is often a carbonaceous film known as a phytoleim, in which case the fossil is known as a compression. Often, however, the phytoleim is lost and all that remains is an impression of the organism in the rock—an impression fossil. In many cases, however, compressions and impressions occur together. For instance, when the rock is broken open, the phytoleim will often be attached to one part (compression), whereas the counterpart will just be an impression. For this reason, one term covers the two modes of preservation: adpression.[85]

Carbonization and coalification

[edit]Fossils that are carbonized or coalified consist of the organic remains which have been reduced primarily to the chemical element carbon. Carbonized fossils consist of a thin film which forms a silhouette of the original organism, and the original organic remains were typically soft tissues. Coalified fossils consist primarily of coal, and the original organic remains were typically woody in composition.

-

Carbonized fossil of a cycloneuralian worm that was once misidentified as a leech[86] from the Silurian Waukesha Biota of Wisconsin.

Soft tissue, cell and molecular preservation

[edit]Because of their antiquity, an unexpected exception to the alteration of an organism's tissues by chemical reduction of the complex organic molecules during fossilization has been the discovery of soft tissue in dinosaur fossils, including blood vessels, and the isolation of proteins and evidence for DNA fragments.[87][88][89][90] In 2014, Mary Schweitzer and her colleagues reported the presence of iron particles (goethite-aFeO(OH)) associated with soft tissues recovered from dinosaur fossils. Based on various experiments that studied the interaction of iron in haemoglobin with blood vessel tissue they proposed that solution hypoxia coupled with iron chelation enhances the stability and preservation of soft tissue and provides the basis for an explanation for the unforeseen preservation of fossil soft tissues.[91] However, a slightly older study based on eight taxa ranging in time from the Devonian to the Jurassic found that reasonably well-preserved fibrils that probably represent collagen were preserved in all these fossils and that the quality of preservation depended mostly on the arrangement of the collagen fibers, with tight packing favoring good preservation.[92] There seemed to be no correlation between geological age and quality of preservation, within that timeframe.

Bioimmuration

[edit]

Bioimmuration occurs when a skeletal organism overgrows or otherwise subsumes another organism, preserving the latter, or an impression of it, within the skeleton.[94] Usually it is a sessile skeletal organism, such as a bryozoan or an oyster, which grows along a substrate, covering other sessile sclerobionts. Sometimes the bioimmured organism is soft-bodied and is then preserved in negative relief as a kind of external mold. There are also cases where an organism settles on top of a living skeletal organism that grows upwards, preserving the settler in its skeleton. Bioimmuration is known in the fossil record from the Ordovician[95] to the Recent.[94]

Types

[edit]

Index

[edit]Index fossils (also known as guide fossils, indicator fossils or zone fossils) are fossils used to define and identify geologic periods (or faunal stages). They work on the premise that, although different sediments may look different depending on the conditions under which they were deposited, they may include the remains of the same species of fossil. The shorter the species' time range, the more precisely different sediments can be correlated, and so rapidly evolving species' fossils are particularly useful as index fossils. The best index fossils are common, easy to identify at species level and have a broad distribution—otherwise the likelihood of finding and recognizing one in the two sediments is poor.

Trace

[edit]Trace fossils are fossil records of biological activity by lifeforms but not the preserved remains of the organism itself. They consist mainly of tracks and burrows, but also include coprolites (fossil feces) and marks left by feeding.[96][97] Trace fossils are particularly significant because they represent a data source that is not limited to animals with easily fossilized hard parts, and they reflect animal behaviours. Many traces date from significantly earlier than the body fossils of animals that are thought to have been capable of making them.[98] Whilst exact assignment of trace fossils to their makers is generally impossible, traces may for example provide the earliest physical evidence of the appearance of moderately complex animals (comparable to earthworms).[97]

Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. They were first described by William Buckland in 1829. Prior to this they were known as "fossil fir cones" and "bezoar stones." They serve a valuable purpose in paleontology because they provide direct evidence of the predation and diet of extinct organisms.[99] Coprolites may range in size from a few millimetres to over 60 centimetres.

-

A coprolite of a carnivorous dinosaur found in southwestern Saskatchewan

-

Densely packed, subaerial or nearshore trackways (Climactichnites wilsoni) made by a putative, slug-like mollusk on a Cambrian tidal flat

Transitional

[edit]A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group.[100] This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross anatomy and mode of living from the ancestral group. Because of the incompleteness of the fossil record, there is usually no way to know exactly how close a transitional fossil is to the point of divergence. These fossils serve as a reminder that taxonomic divisions are human constructs that have been imposed in hindsight on a continuum of variation.

Microfossils

[edit]

Microfossil is a descriptive term applied to fossilized plants and animals whose size is just at or below the level at which the fossil can be analyzed by the naked eye. A commonly applied cutoff point between "micro" and "macro" fossils is 1 mm. Microfossils may either be complete (or near-complete) organisms (such as the marine plankters foraminifera and coccolithophores) or component parts (such as small teeth or spores) of larger animals or plants. Microfossils are of critical importance as a reservoir of paleoclimate information, and are also commonly used by biostratigraphers to assist in the correlation of rock units.

Resin

[edit]

Fossil resin (colloquially called amber) is a natural polymer found in many types of strata throughout the world, even the Arctic. The oldest fossil resin dates to the Triassic, though most dates to the Cenozoic. The excretion of resin by certain plants is thought to be an evolutionary adaptation for to protect against insects and to seal wounds. Fossil resin often contains other fossils, called inclusions, that were captured by the sticky resin. These include bacteria, fungi, other plants, and animals. Animal inclusions are usually small invertebrates, predominantly arthropods such as insects and spiders, and only extremely rarely a vertebrate such as a small lizard. Preservation of inclusions can be exquisite, including small fragments of DNA.

Derived or reworked

[edit]

A derived, reworked or remanié fossil is a fossil found in rock that accumulated significantly later than when the fossilized animal or plant died.[101] Reworked fossils are created by erosion exhuming (freeing) fossils from the rock formation in which they were originally deposited and redepositing them in a younger sedimentary deposit.

Wood

[edit]Fossil wood is wood that is preserved in the fossil record. Wood is usually the part of a plant that is best preserved (and most easily found). Fossil wood may or may not be petrified. The fossil wood may be the only part of the plant that has been preserved;[102] therefore such wood may get a special kind of botanical name. This will usually include "xylon" and a term indicating its presumed affinity, such as Araucarioxylon (wood of Araucaria or some related genus), Palmoxylon (wood of an indeterminate palm), or Castanoxylon (wood of an indeterminate chinkapin).[103]

Subfossil

[edit]

The term subfossil can be used to refer to remains, such as bones, nests, or fecal deposits, whose fossilization process is not complete, either because the length of time since the animal involved was living is too short or because the conditions in which the remains were buried were not optimal for fossilization.[104] Subfossils are often found in caves or other shelters where they can be preserved for thousands of years.[105] The main importance of subfossil vs. fossil remains is that the former contain organic material, which can be used for radiocarbon dating or extraction and sequencing of DNA, protein, or other biomolecules. Additionally, isotope ratios can provide much information about the ecological conditions under which extinct animals lived. Subfossils are useful for studying the evolutionary history of an environment and can be important to studies in paleoclimatology.

Subfossils are often found in depositionary environments, such as lake sediments, oceanic sediments, and soils. Once deposited, physical and chemical weathering can alter the state of preservation, and small subfossils can also be ingested by living organisms. Subfossil remains that date from the Mesozoic are exceptionally rare, are usually in an advanced state of decay, and are consequently much disputed.[106] The vast bulk of subfossil material comes from Quaternary sediments, including many subfossilized chironomid head capsules, ostracod carapaces, diatoms, and foraminifera.

For remains such as molluscan seashells, which frequently do not change their chemical composition over geological time, and may occasionally even retain such features as the original color markings for millions of years, the label 'subfossil' is applied to shells that are understood to be thousands of years old, but are of Holocene age, and therefore are not old enough to be from the Pleistocene epoch.[107]

Chemical fossils

[edit]Chemical fossils, or chemofossils, are chemicals found in rocks and fossil fuels (petroleum, coal, and natural gas) that provide an organic signature for ancient life. Molecular fossils and isotope ratios represent two types of chemical fossils.[108] The oldest traces of life on Earth are fossils of this type, including carbon isotope anomalies found in zircons that imply the existence of life as early as 4.1 billion years ago.[12][13]

Stromatolites

[edit]

Stromatolites are layered accretionary structures formed in shallow water by the trapping, binding and cementation of sedimentary grains by biofilms of microorganisms, especially cyanobacteria.[109] Stromatolites provide some of the most ancient fossil records of life on Earth, dating back more than 3.5 billion years ago.[110]

Stromatolites were much more abundant in Precambrian times. While older, Archean fossil remains are presumed to be colonies of cyanobacteria, younger (that is, Proterozoic) fossils may be primordial forms of the eukaryote chlorophytes (that is, green algae). One genus of stromatolite very common in the geologic record is Collenia. The earliest stromatolite of confirmed microbial origin dates to 2.724 billion years ago.[111]

A 2009 discovery provides strong evidence of microbial stromatolites extending as far back as 3.45 billion years ago.[112][113]

Stromatolites are a major constituent of the fossil record for life's first 3.5 billion years, peaking about 1.25 billion years ago.[112] They subsequently declined in abundance and diversity,[114] which by the start of the Cambrian had fallen to 20% of their peak. The most widely supported explanation is that stromatolite builders fell victims to grazing creatures (the Cambrian substrate revolution), implying that sufficiently complex organisms were common over 1 billion years ago.[115][116][117]

The connection between grazer and stromatolite abundance is well documented in the younger Ordovician evolutionary radiation; stromatolite abundance also increased after the end-Ordovician and end-Permian extinctions decimated marine animals, falling back to earlier levels as marine animals recovered.[118] Fluctuations in metazoan population and diversity may not have been the only factor in the reduction in stromatolite abundance. Factors such as the chemistry of the environment may have been responsible for changes.[119]

While prokaryotic cyanobacteria themselves reproduce asexually through cell division, they were instrumental in priming the environment for the evolutionary development of more complex eukaryotic organisms. Cyanobacteria (as well as extremophile Gammaproteobacteria) are thought to be largely responsible for increasing the amount of oxygen in the primeval Earth's atmosphere through their continuing photosynthesis. Cyanobacteria use water, carbon dioxide and sunlight to create their food. A layer of mucus often forms over mats of cyanobacterial cells. In modern microbial mats, debris from the surrounding habitat can become trapped within the mucus, which can be cemented by the calcium carbonate to grow thin laminations of limestone. These laminations can accrete over time, resulting in the banded pattern common to stromatolites. The domal morphology of biological stromatolites is the result of the vertical growth necessary for the continued infiltration of sunlight to the organisms for photosynthesis. Layered spherical growth structures termed oncolites are similar to stromatolites and are also known from the fossil record. Thrombolites are poorly laminated or non-laminated clotted structures formed by cyanobacteria common in the fossil record and in modern sediments.[111]

The Zebra River Canyon area of the Kubis platform in the deeply dissected Zaris Mountains of southwestern Namibia provides an extremely well exposed example of the thrombolite-stromatolite-metazoan reefs that developed during the Proterozoic period, the stromatolites here being better developed in updip locations under conditions of higher current velocities and greater sediment influx.[120]

Pseudofossils

[edit]

Pseudofossils are visual patterns in rocks that imitate fossils but are produced by geologic processes rather than biologic processes. Some pseudofossils, such as geological dendrite crystals, are formed by naturally occurring fissures in the rock that get filled up by percolating minerals. Other types of pseudofossils are kidney ore (round shapes in iron ore) and moss agates, which look like moss or plant leaves. Concretions, spherical or ovoid-shaped nodules found in some sedimentary strata, were once thought to be dinosaur eggs and are often mistaken for fossils as well.

Astrobiology

[edit]It has been suggested that biominerals could be important indicators of extraterrestrial life and thus could play an important role in the search for past or present life on the planet Mars. Furthermore, organic components (biosignatures) that are often associated with biominerals are believed to play crucial roles in both pre-biotic and biotic reactions.[121]

On 24 January 2014, NASA reported that current studies by the Curiosity and Opportunity rovers on Mars would begin searching for evidence of ancient life, including a biosphere based on autotrophic, chemotrophic and/or chemolithoautotrophic microorganisms, as well as ancient water, including fluvio-lacustrine environments (plains related to ancient rivers or lakes) that may have been habitable.[122][123][124][125] The search for evidence of habitability, taphonomy (related to fossils), and organic carbon on the planet Mars is now a primary NASA objective.[122][123]

Art

[edit]According to one hypothesis, a Corinthian vase from the 6th century BCE (Boston 63.420) is the oldest artistic record of a vertebrate fossil, perhaps a Miocene giraffe combined with elements from other species.[126] However, a later study by Julián Monge-Nájera using expert evaluations rejects this idea, because mammals do not have the eye bones shown on the painted monster. Monge-Nájera believes the morphology shown in the vase painting corresponds best to an extant varanid that would have been known to the Ancient Greeks.[127]

Trading and collecting

[edit]Fossil trading is the practice of buying and selling fossils. This is often done illegally with artifacts stolen from research sites, costing many important scientific specimens each year.[128] The problem is quite pronounced in China, where many specimens have been stolen.[129]

Fossil collecting (sometimes, in a non-scientific sense, fossil hunting) is the collection of fossils for scientific study, leisure, or profit. Amateur fossil collecting is the predecessor of modern paleontology and remains a practiced hobby to date. Professionals and amateurs alike collect fossils for their scientific value.

As medicine

[edit]The use of fossils to address health issues is rooted in traditional medicine and include the use of fossils as talismans. The specific fossil to use to alleviate or cure an illness is often based on its resemblance to the symptoms or affected organ (see sympathetic magic). The usefulness of fossils as medicine is almost entirely a placebo effect, though fossil material might conceivably have some antacid activity or supply some essential minerals.[130] The use of dinosaur bones as "dragon bones" has persisted in Traditional Chinese medicine into modern times, with mid-Cretaceous dinosaur bones being consumed in Ruyang County during the early 21st century.[131]

Gallery

[edit]-

Marine fossils found high in the Himalayas. Collection of the Abbot of Dhankar Gompa, HP, India

-

Three small ammonite fossils, each approximately 1.5 cm across

-

Eocene fossil fish Priscacara liops from the Green River Formation of Wyoming

-

A permineralized trilobite, Asaphus kowalewskii

-

Fossil shrimp (Cretaceous)

-

Petrified wood in Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

-

Petrified cone of Araucaria mirabilis from Patagonia, Argentina dating from the Jurassic Period (approx. 210 Ma)

-

Silurian Orthoceras fossil

-

Eocene fossil flower from Florissant, Colorado

-

Fossils from beaches of the Baltic Sea island of Gotland, placed on paper with 7 mm (0.28 inch) squares

-

Dinosaur footprints from Torotoro National Park in Bolivia.

See also

[edit]- Bioerosion – Erosion of hard substrates by living organisms

- Cryptospore – Fossilised primitive plant spore

- Endolith – Organism living inside a rock

- List of fossil parks

- Living fossil – Organism resembling a form long shown in the fossil records

- Paleobiology – Study of organic evolution using fossils

- Paleobotany – Study of organic evolution of plants based on fossils

- Schultz's rule – Relationship between tooth wear and lifespan of fossil organisms

- Shark tooth – Teeth of a shark

- Signor–Lipps effect – Sampling bias in the fossil record raising difficulties to characterize extinctions

References

[edit]- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Jablonski, David; Roy, Kaustuv; Valentine, James W.; Price, Rebecca M.; Anderson, Philip S. (16 May 2003). "The impact of the pull of the recent on the history of marine diversity". Science. 300 (5622): 1133–1135. Bibcode:2003Sci...300.1133J. doi:10.1126/science.1083246. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 12750517. S2CID 42468747.

- ^ Sahney, Sarda; Benton, Michael J.; Ferry, Paul A. (23 August 2010). "Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land". Biology Letters. 6 (4): 544–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024. PMC 2936204. PMID 20106856.

- ^ Sahney, Sarda; Benton, Michael (2017). "The impact of the Pull of the Recent on the fossil record of tetrapods" (PDF). Evolutionary Ecology Research. 18: 7–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Edward B. Daeschler, Neil H. Shubin and Farish A. Jenkins Jr. (6 April 2006). "A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan" (PDF). Nature. 440 (7085): 757–763. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..757D. doi:10.1038/nature04639. PMID 16598249. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Bertling, M; et al. (2006). "Names for trace fossils: a uniform approach". Lethaia. 39 (3): 265–286. Bibcode:2006Letha..39..265B. doi:10.1080/00241160600787890. hdl:11336/16772.

- ^ Bertling, M; et al. (2022). "Names for trace fossils 2.0: theory and practice in ichnotaxonomy". Lethaia. 55 (3): 1–19. Bibcode:2022Letha..55..3.3B. doi:10.18261/let.55.3.3.

- ^ "theNAT :: San Diego Natural History Museum :: Your Nature Connection in Balboa Park :: Frequently Asked Questions". Sdnhm.org. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (13 November 2013). "Oldest fossil found: Meet your microbial mom". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Noffke, Nora; Christian, Daniel; Wacey, David; Hazen, Robert M. (8 November 2013). "Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures Recording an Ancient Ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 Billion-Year-Old Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia". Astrobiology. 13 (12): 1103–24. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13.1103N. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1030. PMC 3870916. PMID 24205812.

- ^ Brian Vastag (21 August 2011). "Oldest 'microfossils' raise hopes for life on Mars". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

Wade, Nicholas (21 August 2011). "Geological Team Lays Claim to Oldest Known Fossils". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2011. - ^ a b Borenstein, Seth (19 October 2015). "Hints of life on what was thought to be desolate early Earth". Excite. Yonkers, NY: Mindspark Interactive Network. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ a b Bell, Elizabeth A.; Boehnike, Patrick; Harrison, T. Mark; et al. (19 October 2015). "Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 (47): 14518–21. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214518B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517557112. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 4664351. PMID 26483481. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015. Early edition, published online before print.

- ^ Westall, Frances; et al. (2001). "Early Archean fossil bacteria and biofilms in hydrothermally influenced sediments from the Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa". Precambrian Research. 106 (1–2): 93–116. Bibcode:2001PreR..106...93W. doi:10.1016/S0301-9268(00)00127-3.

- ^ Donald McFarlan and Norris McWhirter, ed. (1989). Guinness Book of Records - 1990. London: Guinness Superlatives Ltd. p. 50.

- ^ a b c "Prehistoric Fossil Collectors". Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Ancient Egyptians Collected Fossils". 5 September 2016. Archived from the original on 10 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Aristotle (1931) [350 BCE]. "Book III part 6". Meteorology. Translated by E. W. Webster. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2023 – via The Internet Classics Archive.

- ^ Rudwick, M. J. S. (1985). The Meaning of Fossils: Episodes in the History of Palaeontology. University of Chicago Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-226-73103-2. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "Cartilaginous fish". Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "References to fossils by Pliny the Elder". Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Mayor, Adrienne (24 October 2013). Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4931-4. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Helm, Charles (29 January 2019). Joseph, Natasha (ed.). "How we know that ancient African people valued fossils and rocks". doi:10.64628/AAJ.3xdfskjuy. Archived from the original on 10 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "4億年前"書法化石"展出 黃庭堅曾刻下四行詩[圖]" [400 million-year-old fossil appeared in exhibition with poem by Huang Tingjian]. People's Daily Net (in Traditional Chinese). 17 May 2013. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections. Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing. III, p. 23

- ^ a b Needham, Joseph. (1959). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge University Press. pp. 603–618.

- ^ Chan, Alan Kam-leung and Gregory K. Clancey, Hui-Chieh Loy (2002). Historical Perspectives on East Asian Science, Technology and Medicine. Singapore: Singapore University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9971-69-259-7.

- ^ Rafferty, John P. (2012). Geological Sciences; Geology: Landforms, Minerals, and Rocks. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, p. 6. ISBN 9781615305445

- ^ Desmond, Adrian. "The Discovery of Marine Transgressions and the Explanation of Fossils in Antiquity", American Journal of Science, 1975, Volume 275: 692–707.

- ^ Rafferty, John P. (2012). Geological Sciences; Geology: Landforms, Minerals, and Rocks. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, pp. 5–6. ISBN 9781615305445.

- ^ Alistair Cameron Crombie (1990). Science, optics, and music in medieval and early modern thought. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-907628-79-8. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ "Cyclops Myth Spurred by 'One-Eyed' Fossils?". National Geographic Society. 5 February 2003. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "8 Types of Imaginary Creatures "Discovered" In Fossils". 19 May 2015. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Folklore of Fossil Echinoderms". 4 April 2017. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ McNamara, Kenneth J. (2007). "Shepherds' crowns, fairy loaves and thunderstones: the mythology of fossil echinoids in England". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 273 (1): 279–294. Bibcode:2007GSLSP.273..279M. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2007.273.01.22. S2CID 129384807. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Archaeological Echinoderm! Fairy Loaves & Thunderstones!". 12 January 2009. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Baucon, Andrea (2010). "Leonardo da Vinci, the founding father of ichnoogy". PALAIOS. 25 (5/6). SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology: 361–367. Bibcode:2010Palai..25..361B. doi:10.2110/palo.2009.p09-049r. JSTOR 40606506. S2CID 86011122.

- ^ da Vinci, Leonardo (1956) [1938]. The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. London: Reynal & Hitchcock. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-9737837-3-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)[permanent dead link] - ^ Bressan, David. "July 18, 1635: Robert Hooke – The Last Virtuoso of Silly Science". Scientific American Blog Network. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Cuvier". palaeo.gly.bris.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ "Mary Anning". Lyme Regis Museum. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1872), "Chapter X: On the Imperfection of the Geological Record", The Origin of Species, London: John Murray

- ^ Schopf JW (1999) Cradle of Life: The Discovery of the Earth's Earliest Fossils, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- ^ "The Virtual Fossil Museum – Fossils Across Geological Time and Evolution". Archived from the original on 8 March 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- ^ Knoll, A, (2003) Life on a Young Planet. (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ)

- ^ Donovan, S. K.; Paul, C. R. C., eds. (1998). "An Overview of the Completeness of the Fossil Record". The Adequacy of the Fossil Record. New York: Wiley. pp. 111–131. ISBN 978-0-471-96988-4.

- ^ Fortey, Richard, Trilobite!: Eyewitness to Evolution. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2000.

- ^ Donoghue, PCJ; Bengtson, S; Dong, X; Gostling, NJ; Huldtgren, T; Cunningham, JA; Yin, C; Yue, Z; Peng, F; et al. (2006). "Synchrotron X-ray tomographic microscopy of fossil embryos". Nature. 442 (7103): 680–683. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..680D. doi:10.1038/nature04890. PMID 16900198. S2CID 4411929.

- ^ Foote, M.; Sepkoski, J.J. Jr (1999). "Absolute measures of the completeness of the fossil record". Nature. 398 (6726): 415–417. Bibcode:1999Natur.398..415F. doi:10.1038/18872. PMID 11536900. S2CID 4323702.

- ^ Benton, M. (2009). "The completeness of the fossil record". Significance. 6 (3): 117–121. doi:10.1111/j.1740-9713.2009.00374.x. S2CID 84441170.

- ^ Žliobaitė, I.; Fortelius, M. (2021). "On calibrating the completometer for the mammalian fossil record". Paleobiology. 48: 1–11. doi:10.1017/pab.2021.22. S2CID 238686414.

- ^ Eiting, T.P.; Gunnell, G.G (2009). "Global Completeness of the Bat Fossil Record". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 16 (3): 151–173. doi:10.1007/s10914-009-9118-x. S2CID 5923450.

- ^ Brocklehurst, N.; Upchurch, P.; Mannion, P.D.; O'Connor, J. (2012). "The Completeness of the Fossil Record of Mesozoic Birds: Implications for Early Avian Evolution". PLOS ONE. 7 (6) e39056. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...739056B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039056. PMC 3382576. PMID 22761723.

- ^ Retallack, G. (1984). "Completeness of the rock and fossil record: some estimates using fossil soils". Paleobiology. 10 (1): 59–78. Bibcode:1984Pbio...10...59R. doi:10.1017/S0094837300008022. S2CID 140168970.

- ^ Benton, M.J.; Storrs, G.Wm. (1994). "Testing the quality of the fossil record: Paleontological knowledge is improving". Geology. 22 (2): 111–114. Bibcode:1994Geo....22..111B. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1994)022<0111:TTQOTF>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Holland, S.M.; Patzkowsky, M.E. (1999). "Models for simulating the fossil record". Geology. 27 (6): 491–494. Bibcode:1999Geo....27..491H. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0491:MFSTFR>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Koch, C. (1978). "Bias in the published fossil record". Paleobiology. 4 (3): 367–372. Bibcode:1978Pbio....4..367K. doi:10.1017/S0094837300006060. S2CID 87368101.

- ^ Signore, P.W. III; Lipps, J.H. (1982). "Sampling bias, gradual extinction patterns and catastrophes in the fossil record". In Silver, L.T.; Schultz, P.H. (eds.). Geological Implications of Impacts of Large Asteroids and Comets on the Earth. Geological Society of America Special Papers. Vol. 190. pp. 291–296. doi:10.1130/SPE190-p291. ISBN 0-8137-2190-3.

- ^ Vilhena, D.A.; Smith, A.B. (2013). "Spatial Bias in the Marine Fossil Record". PLOS ONE. 8 (10) e74470. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...874470V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074470. PMC 3813679. PMID 24204570.

- ^ a b Martin, M.W.; Grazhdankin, D.V.; Bowring, S.A.; Evans, D.A.D.; Fedonkin, M.A.; Kirschvink, J.L. (5 May 2000). "Age of Neoproterozoic Bilaterian Body and Trace Fossils, White Sea, Russia: Implications for Metazoan Evolution". Science. 288 (5467): 841–5. Bibcode:2000Sci...288..841M. doi:10.1126/science.288.5467.841. PMID 10797002. S2CID 1019572.

- ^ Pufahl, P.K.; Grimm, K.A.; Abed, A.M. & Sadaqah, R.M.Y. (October 2003). "Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) phosphorites in Jordan: implications for the formation of a south Tethyan phosphorite giant". Sedimentary Geology. 161 (3–4): 175–205. Bibcode:2003SedG..161..175P. doi:10.1016/S0037-0738(03)00070-8.

- ^ "Geologic Time: Radiometric Time Scale". U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ Löfgren, A. (2004). "The conodont fauna in the Middle Ordovician Eoplacognathus pseudoplanus Zone of Baltoscandia". Geological Magazine. 141 (4): 505–524. Bibcode:2004GeoM..141..505L. doi:10.1017/S0016756804009227. S2CID 129600604.

- ^ a b Gehling, James; Jensen, Sören; Droser, Mary; Myrow, Paul; Narbonne, Guy (March 2001). "Burrowing below the basal Cambrian GSSP, Fortune Head, Newfoundland". Geological Magazine. 138 (2): 213–218. Bibcode:2001GeoM..138..213G. doi:10.1017/S001675680100509X. hdl:10662/24314. S2CID 131211543.

- ^ Hug, L.A.; Roger, A.J. (2007). "The Impact of Fossils and Taxon Sampling on Ancient Molecular Dating Analyses". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (8): 889–1897. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm115. PMID 17556757.

- ^ Peterson, Kevin J.; Butterfield, N.J. (2005). "Origin of the Eumetazoa: Testing ecological predictions of molecular clocks against the Proterozoic fossil record". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (27): 9547–52. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.9547P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503660102. PMC 1172262. PMID 15983372.

- ^ a b Prothero, Donald R. (2007). Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters. Columbia University Press. pp. 50–53. ISBN 978-0-231-51142-1.

- ^ Isaak, M (5 November 2006). "Claim CC200: There are no transitional fossils". TalkOrigins Archive. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ Donovan, S. K.; Paul, C. R. C., eds. (1998). The Adequacy of the Fossil Record. New York: Wiley. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-471-96988-4.[page needed]

- ^ Prothero 2013, pp. 8–9.

- ^ "Molecular Expressions Microscopy Primer: Specialized Microscopy Techniques - Phase Contrast Photomicrography Gallery - Agatized Dinosaur Bone". micro.magnet.fsu.edu. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Exclusive: Sparkly, opal-filled fossils reveal new dinosaur species". Science. 4 December 2018. Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Gem-like fossils reveal stunning new dinosaur species". Science. 3 June 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Prothero, Donald R. (2013). Bringing fossils to life: an introduction to paleobiology (Third ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-231-15893-0.

- ^ Prothero 2013, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Prothero 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Wilby, P.; Briggs, D. (1997). "Taxonomic trends in the resolution of detail preserved in fossil phosphatized soft tissues". Geobios. 30: 493–502. Bibcode:1997Geobi..30..493W. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(97)80056-3.

- ^ Wacey, D. et al (2013) Nanoscale analysis of pyritized microfossils reveals differential heterotrophic consumption in the ~1.9-Ga Gunflint chert PNAS 110 (20) 8020-8024 doi:10.1073/pnas.1221965110

- ^ Raiswell, R. (1997). A geochemical framework for the application of stable sulfur isotopes to fossil pyritization. Journal of the Geological Society 154, 343–356.

- ^ Oehler, John H., & Schopf, J. William (1971). Artificial microfossils: Experimental studies of permineralization of blue-green algae in silica. Science. 174, 1229–1231.

- ^ Götz, Annette E.; Montenari, Michael; Costin, Gelu (2017). "Silicification and organic matter preservation in the Anisian Muschelkalk: Implications for the basin dynamics of the central European Muschelkalk Sea". Central European Geology. 60 (1): 35–52. Bibcode:2017CEJGl..60...35G. doi:10.1556/24.60.2017.002. ISSN 1788-2281.

- ^ Prothero 2013, pp. 9–10.

- ^ "Definition of Steinkern". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

a fossil consisting of a stony mass that entered a hollow natural object (such as a bivalve shell) in the form of mud or sediment, was consolidated, and remained as a cast after dissolution of the mold

- ^ Prothero 2013, p. 579.

- ^ Shute, C. H.; Cleal, C. J. (1986). "Palaeobotany in museums". Geological Curator. 4 (9): 553–559. doi:10.55468/GC865. S2CID 251638416.

- ^ Braddy, Simon J.; Gass, Kenneth C.; Tessler, Michael (4 September 2023). "Not the first leech: An unusual worm from the early Silurian of Wisconsin". Journal of Paleontology. 97 (4): 799–804. Bibcode:2023JPal...97..799B. doi:10.1017/jpa.2023.47. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 261535626.

- ^ Fields H (May 2006). "Dinosaur Shocker – Probing a 68-million-year-old T. rex, Mary Schweitzer stumbled upon astonishing signs of life that may radically change our view of the ancient beasts". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015.

- ^ Schweitzer MH, Wittmeyer JL, Horner JR, Toporski JK (25 March 2005). "Soft-tissue vessels and cellular preservation in Tyrannosaurus rex". Science. 307 (5717): 1952–5. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1952S. doi:10.1126/science.1108397. PMID 15790853. S2CID 30456613.

- ^ Schweitzer MH, Zheng W, Cleland TP, Bern M (January 2013). "Molecular analyses of dinosaur osteocytes support the presence of endogenous molecules". Bone. 52 (1): 414–23. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2012.10.010. PMID 23085295.

- ^ Embery G, Milner AC, Waddington RJ, Hall RC, Langley ML, Milan AM (2003). "Identification of Proteinaceous Material in the Bone of the Dinosaur Iguanodon". Connective Tissue Research. 44 (Suppl 1): 41–6. doi:10.1080/03008200390152070. PMID 12952172. S2CID 2249126.

- ^ Schweitzer MH, Zheng W, Cleland TP, Goodwin MB, Boatman E, Theil E, Marcus MA, Fakra SC (November 2013). "A role for iron and oxygen chemistry in preserving soft tissues, cells and molecules from deep time". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 281 (1774) 20132741. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2741. PMC 3866414. PMID 24285202.

- ^ Zylberberg, L.; Laurin, M. (2011). "Analysis of fossil bone organic matrix by transmission electron microscopy". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (5–6): 357–366. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.04.004.

- ^ Palmer, T. J.; Wilson, MA (1988). "Parasitism of Ordovician bryozoans and the origin of pseudoborings". Palaeontology. 31: 939–949.

- ^ a b Taylor, P. D. (1990). "Preservation of soft-bodied and other organisms by bioimmuration: A review". Palaeontology. 33: 1–17.

- ^ Wilson, MA; Palmer, T. J.; Taylor, P. D. (1994). "Earliest preservation of soft-bodied fossils by epibiont bioimmuration: Upper Ordovician of Kentucky". Lethaia. 27 (3): 269–270. Bibcode:1994Letha..27..269W. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1994.tb01420.x.

- ^ "What is paleontology?". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ a b Fedonkin, M.A.; Gehling, J.G.; Grey, K.; Narbonne, G.M.; Vickers-Rich, P. (2007). The Rise of Animals: Evolution and Diversification of the Kingdom Animalia. JHU Press. pp. 213–216. ISBN 978-0-8018-8679-9. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ e.g. Seilacher, A. (1994). "How valid is Cruziana Stratigraphy?". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 83 (4): 752–758. Bibcode:1994GeoRu..83..752S. doi:10.1007/BF00251073. S2CID 129504434.

- ^ "coprolites". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Herron, Scott; Freeman, Jon C. (2004). Evolutionary analysis (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. p. 816. ISBN 978-0-13-101859-4. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Neuendorf, Klaus K. E.; Institute, American Geological (2005). Glossary of Geology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-922152-76-6. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Ed Strauss (2001). "Petrified Wood from Western Washington". Archived from the original on 11 December 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Wilson Nichols Stewart; Gar W. Rothwell (1993). Paleobotany and the evolution of plants (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-38294-6.

- ^ "Subfossils Collections". South Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Subfossils Collections". South Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Peterson, Joseph E.; Lenczewski, Melissa E.; Scherer, Reed P. (October 2010). Stepanova, Anna (ed.). "Influence of Microbial Biofilms on the Preservation of Primary Soft Tissue in Fossil and Extant Archosaurs". PLOS ONE. 5 (10): 13A. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513334P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013334. PMC 2953520. PMID 20967227.

- ^ Anand, Konkala (2022). Zoology: Animal Distribution, Evolution And Development. AG PUBLISHING HOUSE. p. 42. ISBN 978-93-95936-29-3.

- ^ "Chemical or Molecular Fossils". petrifiedwoodmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Riding, R. (2007). "The term stromatolite: towards an essential definition". Lethaia. 32 (4): 321–330. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1999.tb00550.x. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015.

- ^ "Stromatolites, the Oldest Fossils". Archived from the original on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- ^ a b Lepot, Kevin; Benzerara, Karim; Brown, Gordon E.; Philippot, Pascal (2008). "Microbially influenced formation of 2.7 billion-year-old stromatolites". Nature Geoscience. 1 (2): 118–21. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..118L. doi:10.1038/ngeo107.

- ^ a b Allwood, Abigail C.; Grotzinger, John P.; Knoll, Andrew H.; Burch, Ian W.; Anderson, Mark S.; Coleman, Max L.; Kanik, Isik (2009). "Controls on development and diversity of Early Archean stromatolites". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (24): 9548–9555. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9548A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903323106. PMC 2700989. PMID 19515817.

- ^ Schopf, J. William (1999). Cradle of life: the discovery of earth's earliest fossils. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-0-691-08864-8. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ McMenamin, M. A. S. (1982). "Precambrian conical stromatolites from California and Sonora". Bulletin of the Southern California Paleontological Society. 14 (9&10): 103–105.

- ^ McNamara, K.J. (20 December 1996). "Dating the Origin of Animals". Science. 274 (5295): 1993–1997. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1993M. doi:10.1126/science.274.5295.1993f.

- ^ Awramik, S.M. (19 November 1971). "Precambrian columnar stromatolite diversity: Reflection of metazoan appearance". Science. 174 (4011): 825–827. Bibcode:1971Sci...174..825A. doi:10.1126/science.174.4011.825. PMID 17759393. S2CID 2302113.

- ^ Bengtson, S. (2002). "Origins and early evolution of predation" (PDF). In Kowalewski, M.; Kelley, P.H. (eds.). The fossil record of predation. The Paleontological Society Papers. Vol. 8. The Paleontological Society. pp. 289–317. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Sheehan, P.M.; Harris, M.T. (2004). "Microbialite resurgence after the Late Ordovician extinction". Nature. 430 (6995): 75–78. Bibcode:2004Natur.430...75S. doi:10.1038/nature02654. PMID 15229600. S2CID 4423149.

- ^ Riding R (March 2006). "Microbial carbonate abundance compared with fluctuations in metazoan diversity over geological time" (PDF). Sedimentary Geology. 185 (3–4): 229–38. Bibcode:2006SedG..185..229R. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2005.12.015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ Adams, E. W.; Grotzinger, J. P.; Watters, W. A.; Schröder, S.; McCormick, D. S.; Al-Siyabi, H. A. (2005). "Digital characterization of thrombolite-stromatolite reef distribution in a carbonate ramp system (terminal Proterozoic, Nama Group, Namibia)" (PDF). AAPG Bulletin. 89 (10): 1293–1318. Bibcode:2005BAAPG..89.1293A. doi:10.1306/06160505005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ The MEPAG Astrobiology Field Laboratory Science Steering Group (26 September 2006). "Final report of the MEPAG Astrobiology Field Laboratory Science Steering Group (AFL-SSG)" (.doc). In Steele, Andrew; Beaty, David (eds.). The Astrobiology Field Laboratory. U.S.: Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG) – NASA. p. 72. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ a b Grotzinger, John P. (24 January 2014). "Introduction to Special Issue – Habitability, Taphonomy, and the Search for Organic Carbon on Mars". Science. 343 (6169): 386–387. Bibcode:2014Sci...343..386G. doi:10.1126/science.1249944. PMID 24458635.

- ^ a b Various (24 January 2014). "Special Issue – Table of Contents – Exploring Martian Habitability". Science. 343 (6169): 345–452. Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Various (24 January 2014). "Special Collection – Curiosity – Exploring Martian Habitability". Science. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Grotzinger, J.P.; et al. (24 January 2014). "A Habitable Fluvio-Lacustrine Environment at Yellowknife Bay, Gale Crater, Mars". Science. 343 (6169) 1242777. Bibcode:2014Sci...343A.386G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.455.3973. doi:10.1126/science.1242777. PMID 24324272. S2CID 52836398.

- ^ Mayor, A. (2000). "The "Monster of Troy" Vase: The Earliest Artistic Record of a Vertebrate Fossil Discovery?". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 19 (1): 57–63. doi:10.1111/1468-0092.00099.

- ^ Monge-Nájera, Julián (31 January 2020). "Evaluation of the hypothesis of the Monster of Troy vase as the earliest artistic record of a vertebrate fossil". Uniciencia. 34 (1): 147–151. doi:10.15359/ru.34-1.9. ISSN 2215-3470. S2CID 208591414. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ Milmo, Cahal (25 November 2009). "Fossil theft: One of our dinosaurs is missing". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

Simons, Lewis. "Fossil Wars". National Geographic. The National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

Willis, Paul; Clark, Tim; Dennis, Carina (18 April 2002). "Fossil Trade". Catalyst. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

Farrar, Steve (5 November 1999). "Cretaceous crimes that fuel the fossil trade". Times Higher Education. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2011. - ^ Williams, Paige. "The Black Market for Dinosaurs". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ van der Geer, Alexandra; Dermitzakis, Michael (2010). "Fossils in pharmacy: from "snake eggs" to "Saint's bones"; an overview" (PDF). Hellenic Journal of Geosciences. 45: 323–332. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2013.

- ^ "Chinese villagers ate dinosaur 'dragon bones'". MSNBC. Associated Press. 5 July 2007. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- "Grand Canyon cliff collapse reveals 313 million-year-old fossil footprints" 21 August 2020, CNN

- "Hints of fossil DNA discovered in dinosaur skull" by Michael Greshko, 3 March 2020, National Geographic

- "Fossils for Kids | Learn all about how fossils are formed, the types of fossils and more!" Video (2:23), 27 January 2020, Clarendon Learning

- "Fossil & their formation" Video (9:55), 15 November 2019, Khan Academy

- "How are dinosaur fossils formed? by Lisa Hendry, Natural History Museum, London

- "Fossils 101" Video (4:27), 22 August 2019, National Geographic

- "How to Spot the Fossils Hiding in Plain Sight" by Jessica Leigh Hester, 23 February 2018, Atlas Obscura

- "It's extremely hard to become a fossil" Archived 4 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, by Olivia Judson, 30 December 2008, The New York Times

- "Bones Are Not the Only Fossils" Archived 15 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, by Olivia Judson, 4 March 2008, The New York Times

External links

[edit]- Fossils on In Our Time at the BBC

- The Virtual Fossil Museum throughout Time and Evolution

- Paleoportal, geology and fossils of the United States Archived 30 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- The Fossil Record, a complete listing of the families, orders, class and phyla found in the fossil record (archived 3 May 2012)

- Ernest Ingersoll (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

![Carbonized fossil of a cycloneuralian worm that was once misidentified as a leech[86] from the Silurian Waukesha Biota of Wisconsin.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ac/Probable_leech_from_the_Waukesha_Biota.jpg/120px-Probable_leech_from_the_Waukesha_Biota.jpg)