Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aesop

View on Wikipedia

Aesop (/ˈiːsɒp/ EE-sop; Ancient Greek: Αἴσωπος, Aísōpos; c. 620–564 BCE; formerly rendered as Æsop) was a Greek fabulist and storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as Aesop's Fables. Although his existence remains unclear and no writings by him survive, numerous tales credited to him were gathered across the centuries and in many languages in a storytelling tradition that continues to this day. Many of the tales associated with him are characterized by anthropomorphic animal characters.

Key Information

Scattered details of Aesop's life can be found in ancient sources, including Aristotle, Herodotus, and Plutarch. An ancient literary work called The Aesop Romance tells an episodic, probably highly fictional version of his life, including the traditional description of him as a strikingly ugly slave (δοῦλος) who by his cleverness acquires freedom and becomes an adviser to kings and city-states. Older spellings of his name have included Esop(e) and Isope. Depictions of Aesop in popular culture over the last 2,500 years have included many works of art and his appearance as a character in numerous books, films, plays, and television programs.

Life

[edit]The name of Aesop is as widely known as any that has come down from Graeco-Roman antiquity [yet] it is far from certain whether a historical Aesop ever existed ... in the latter part of the fifth century something like a coherent Aesop legend appears, and Samos seems to be its home.

The earliest Greek sources, including Aristotle, indicate that Aesop was born around 620 BCE in the Greek colony of Mesembria. A number of later writers from the Roman imperial period (including Phaedrus, who adapted the fables into Latin) say that he was born in Phrygia.[2] The 3rd-century poet Callimachus called him "Aesop of Sardis,"[3] and the later writer Maximus of Tyre called him "the sage of Lydia."[4]

By Aristotle[5] and Herodotus[6] we are told that Aesop was a slave in Samos; that his slave masters were first a man named Xanthus, and then a man named Iadmon; that he must eventually have been freed, since he argued as an advocate for a wealthy Samian; and that he met his end in the city of Delphi. Plutarch[7] tells us that Aesop came to Delphi on a diplomatic mission from King Croesus of Lydia, that he insulted the Delphians, that he was sentenced to death on a trumped-up charge of temple theft, and that he was thrown from a cliff (after which the Delphians suffered pestilence and famine). Before this fatal episode, Aesop met with Periander of Corinth, where Plutarch has him dining with the Seven Sages of Greece and sitting beside his friend Solon, whom he had met in Sardis. (Leslie Kurke suggests that Aesop was himself "a popular contender for inclusion" in the list of Seven Sages.)[8]

In 1965, Ben Edwin Perry, an Aesop scholar and compiler of the Perry Index, concluded that, due to problems of chronological reconciliation dating the death of Aesop and the reign of Croesus, "everything in the ancient testimony about Aesop that pertains to his associations with either Croesus or with any of the so-called Seven Wise Men of Greece must be reckoned as literary fiction." Perry likewise dismissed accounts of Aesop's death in Delphi as mere fictional legends.[9] However, later research has established that a possible diplomatic mission for Croesus and a visit to Periander "are consistent with the year of Aesop's death."[10] Still problematic is the story by Phaedrus, which has Aesop, in Athens, relating the fable of the frogs who asked for a king, because Phaedrus has this happening during the reign of Peisistratos, which occurred decades after the presumed date of Aesop's death.[11]

The Aesop Romance

[edit]Along with the scattered references in the ancient sources regarding the life and death of Aesop, there is a highly fictional biography now commonly called The Aesop Romance (also known as the Vita or The Life of Aesop or The Book of Xanthus the Philosopher and Aesop His Slave), "an anonymous work of Greek popular literature composed around the second century of our era ... Like The Alexander Romance, The Aesop Romance became a folkbook, a work that belonged to no one, and the occasional writer felt free to modify as it might suit him."[12] Multiple, sometimes contradictory, versions of this work exist. The earliest known version was probably composed in the 1st century CE, but the story may have circulated in different versions for centuries before it was committed to writing,[13] and certain elements can be shown to originate in the 4th century BCE.[14] Scholars long dismissed any historical or biographical validity in The Aesop Romance; widespread study of the work began only toward the end of the 20th century.

In The Aesop Romance, Aesop is a slave of Phrygian origin on the island of Samos, and extremely ugly. At first he lacks the power of speech, but after showing kindness to a priestess of Isis, is granted by the goddess not only speech but a gift for clever storytelling, which he uses alternately to assist and confound his master, Xanthus, embarrassing the philosopher in front of his students and even sleeping with his wife. After interpreting a portent for the people of Samos, Aesop is given his freedom and acts as an emissary between the Samians and King Croesus. Later he travels to the courts of Lycurgus of Babylon and Nectanabo of Egypt – both imaginary rulers – in a section that appears to borrow heavily from the romance of Ahiqar.[15] The story ends with Aesop's journey to Delphi, where he angers the citizens by telling insulting fables, is sentenced to death and, after cursing the people of Delphi, is forced to jump to his death.

Fabulist

[edit]

Aesop may not have written his fables. The Aesop Romance claims that he wrote them down and deposited them in the library of Croesus; Herodotus calls Aesop a "writer of fables" and Aristophanes speaks of "reading" Aesop,[16] but that might simply have been a compilation of fables ascribed to him.[17] Various Classical authors name Aesop as the originator of fables. Sophocles, in a poem addressed to Euripides, made reference to the North Wind and the Sun.[18] Socrates, while in prison, turned some of the fables into verse,[19] of which Diogenes Laërtius records a small fragment.[20] The early Roman playwright and poet Ennius also rendered at least one of Aesop's fables in Latin verse, of which the last two lines still exist.[21]

Collections of what are claimed to be Aesop's Fables were transmitted by a series of authors writing in both Greek and Latin. Demetrius of Phalerum made what may have been the earliest, probably in prose (Αἰσοπείων α), contained in ten books for the use of orators, although that has since been lost.[22] Next appeared an edition in elegiac verse, cited by the Suda, but the author's name is unknown. Phaedrus, a freedman of Augustus, rendered the fables into Latin in the 1st century CE. At about the same time Babrius turned the fables into Greek choliambics. A 3rd-century author, Titianus, is said to have rendered the fables into prose in a work now lost.[23] Avianus (of uncertain date, perhaps the 4th century) translated 42 of the fables into Latin elegiacs. The 4th-century grammarian Dositheus Magister also made a collection of Aesop's Fables, now lost.

Aesop's Fables continued to be revised and translated through the ensuing centuries, with the addition of material from other cultures, so that the body of fables known today bears little relation to those Aesop originally told. With a surge in scholarly interest beginning toward the end of the 20th century, some attempt has been made to determine the nature and content of the very earliest fables which may be most closely linked to the historic Aesop.[24]

Physical appearance and the question of African origin

[edit]The anonymously authored Aesop Romance begins with a vivid description of Aesop's appearance, saying he was "of loathsome aspect ... potbellied, misshapen of head, snub-nosed, swarthy, dwarfish, bandy-legged, short-armed, squint-eyed, liver-lipped—a portentous monstrosity,"[25] or as another translation has it, "a faulty creation of Prometheus when half-asleep."[26] The earliest text by a known author that refers to Aesop's appearance is Himerius in the 4th century, who says that Aesop "was laughed at and made fun of, not because of some of his tales but on account of his looks and the sound of his voice."[27] The evidence from both of these sources is dubious, since Himerius lived some 800 years after Aesop and his image of Aesop may have come from The Aesop Romance, which is essentially fiction; but whether based on fact or not, at some point the idea of an ugly, even deformed Aesop took hold in popular imagination. Scholars have begun to examine why and how this "physiognomic tradition" developed.[28]

A much later tradition depicts Aesop as a black African from Aethiopia. The first known promulgator of the idea was Planudes, a Byzantine scholar of the 13th century who made a recension of The Aesop Romance in which it is conjectured that Aesop might have been Ethiopian, given his name. But according to Gert-Jan van Dijk, "Planudes' derivation of 'Aesop' from 'Aethiopian' is ... etymologically incorrect,"[29] and Frank Snowden says that Planudes' account is "worthless as to the reliability of Aesop as 'Ethiopian.'"[30]

The notion of Aesop's African origin later reappeared in Britain, as attested by the lively figurine of a negro from the Chelsea porcelain factory which appeared in its Aesop series in the mid-18th century.[31] In 1856 William Martin Leake repeated the false etymological linkage of "Aesop" with "Aethiop" when he suggested that the "head of a negro" found on several coins from ancient Delphi (with specimens dated as early as 520 BCE)[32] might depict Aesop, presumably to commemorate (and atone for) his execution at Delphi,[33] but Theodor Panofka supposed the head to be a portrait of Delphos, founder of Delphi,[34] a view which was repeated later by Frank Snowden, who nevertheless notes that the arguments which have been advanced are not sufficient to establish such an identification.[35]

In 1876 the Italian painter Roberto Fontana portrayed the fabulist as black in Aesop Narrates His Fables to the Handmaids of Xanthus. When the painting was shown at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878, a French critic was dubious: "Why is M. Fontana's Aesop ... black as an Ethiopian? Perhaps M. Fontana knows more about Aesop than we do, which would not be difficult."[36]

The idea that Aesop was Ethiopian seems supported by the presence of camels, elephants and apes in the fables, even though these African elements are more likely to have come from Egypt and Libya than from Ethiopia, and the fables featuring African animals may have entered the body of Aesopic fables long after Aesop actually lived.[37] Nevertheless, in 1932 the anthropologist J. H. Driberg, repeating the Aesop/Aethiop linkage, asserted that, while "some say he [Aesop] was a Phrygian ... the more general view ... is that he was an African", and "if Aesop was not an African, he ought to have been;"[38] and in 2002 Richard A. Lobban Jr. cited the number of African animals and "artifacts" in the Aesopic fables as "circumstantial evidence" that Aesop was a Nubian folkteller.[39]

Popular perception of Aesop as black was to be encouraged by comparison between his fables and the stories of the trickster Br'er Rabbit told by African slaves in North America. In Ian Colvin's introduction to Aesop in Politics (1914), for example, the fabulist is bracketed with Uncle Remus, "For both were slaves, and both were black."[40] The traditional role of the slave Aesop as "a kind of culture hero of the oppressed" is further promoted by the fictional Life, emerging "as a how-to handbook for the successful manipulation of superiors."[41] Such a perception was reinforced at the popular level by the 1971 TV production Aesop's Fables in which Bill Cosby played Aesop. In that mixture of live action and animation, Aesop tells fables that differentiate between realistic and unrealistic ambition and his version there of "The Tortoise and the Hare" illustrates how to take advantage of an opponent's over-confidence.[42]

On other continents Aesop has occasionally undergone a degree of acculturation. This is evident in Isango Portobello's 2010 production of the play Aesop's Fables at the Fugard Theatre in Cape Town, South Africa. Based on a script by British playwright Peter Terson (1983),[43] it was radically adapted by the director Mark Dornford-May as a musical using native African instrumentation, dance and stage conventions.[44] Although Aesop is portrayed as Greek, and dressed in the short Greek tunic, the all-black production contextualises the story in the recent history of South Africa. The former slave, we are told "learns that liberty comes with responsibility as he journeys to his own freedom, joined by the animal characters of his parable-like fables."[45]

There had already been an example of Asian acculturation in 17th-century Japan. There Portuguese missionaries had introduced a translation of the fables (Esopo no Fabulas, 1593) that included the biography of Aesop. This was then taken up by Japanese printers and taken through several editions under the title Isopo Monogatari. Even when Europeans were expelled from Japan and Christianity proscribed, this text survived, in part because the figure of Aesop had been assimilated into the culture and depicted in woodcuts as dressed in Japanese costume.[46][47]

Depictions

[edit]Art and literature

[edit]Ancient sources mention two statues of Aesop, one by Aristodemus and another by Lysippus,[48] and Philostratus describes a painting of Aesop surrounded by the animals of his fables.[49] None of these images have survived. According to Philostratus:[50]

The Fables are gathering about Aesop, being fond of him because he devotes himself to them. For ... he checks greed and rebukes insolence and deceit, and in all this some animal is his mouthpiece—a lion or a fox or a horse ... and not even the tortoise is dumb—that through them children may learn the business of life. So the Fables, honoured because of Aesop, gather at the doors of the wise man to bind fillets about his head and to crown him with a victor's crown of wild olive. And Aesop, methinks, is weaving some fable; at any rate his smile and his eyes fixed on the ground indicate this. The painter knows that for the composition of fables relaxation of the spirit is needed. And the painting is clever in representing the persons of the Fables. For it combines animals with men to make a chorus about Aesop, composed of the actors in his fables; and the fox is painted as leader of the chorus.

With the advent of printing in Europe, various illustrators tried to recreate this scene. One of the earliest was in Spain's La vida del Ysopet con sus fabulas historiadas (1489, see above). In France there was I. Baudoin's Fables d'Ésope Phrygien (1631) and Matthieu Guillemot's Les images ou tableaux de platte peinture des deux Philostrates (1637).[51] In England, there was Francis Cleyn's frontispiece to John Ogilby's The Fables of Aesop[52] and the much later frontispiece to Godwin's Fables Ancient and Modern mentioned above in which the fabulist points out three of his characters to the children seated about him.

Early on, the representation of Aesop as an ugly slave emerged. The later tradition which makes Aesop a black African resulted in depictions ranging from 17th-century engravings to a television portrayal by a black comedian. In general, beginning in the 20th century, plays have shown Aesop as a slave, but not ugly, while movies and television shows (such as The Bullwinkle Show[citation needed]) have depicted him as neither ugly nor a slave.

Perhaps the most elaborate celebration of Aesop and his fables was the labyrinth of Versailles, a hedge maze constructed for Louis XIV with 39 fountains with lead sculptures depicting Aesop's fables. A statue of Aesop by Pierre Le Gros the Elder, depicted as a hunchback, stood on a pedestal at the entrance. Finished in 1677, the labyrinth was demolished in 1778, but the statue of Aesop survives and can be seen in the vestibule of the Queen's Staircase at Versailles.[53]

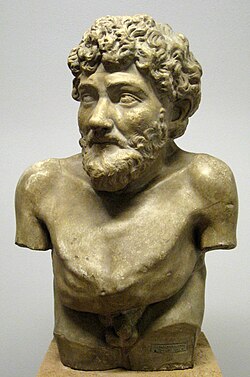

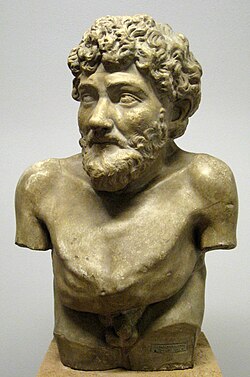

In 1843, the archaeologist Otto Jahn suggested that Aesop was the person depicted on a Greek red-figure cup,[54] c. 450 BCE, in the Vatican Museums.[55] Paul Zanker describes the figure as a man with "emaciated body and oversized head ... furrowed brow and open mouth", who "listens carefully to the teachings of the fox sitting before him. He has pulled his mantle tightly around his meager body, as if he were shivering ... he is ugly, with long hair, bald head, and unkempt, scraggly beard, and is clearly uncaring of his appearance."[56] Some archaeologists have suggested that the Hellenistic statue of a bearded hunchback with an intellectual appearance, discovered in the 18th century and pictured at the head of this article, also depicts Aesop, although alternative identifications have since been put forward.[57]

Aesop began to appear early in literary works. The 4th-century-BCE Athenian playwright Alexis put Aesop on the stage in his comedy "Aesop", of which a few lines survive (Athenaeus 10.432);[58] conversing with Solon, Aesop praises the Athenian practice of adding water to wine.[59] Leslie Kurke suggests that Aesop may have been "a staple of the comic stage" of this era.[60]

The 3rd-century-BCE poet Poseidippus of Pella wrote a narrative poem entitled "Aesopia" (now lost), in which Aesop's fellow slave Rhodopis (under her original name Doricha) was frequently mentioned, according to Athenaeus 13.596.[61] Pliny would later identify Rhodopis as Aesop's lover,[62] a romantic motif that would be repeated in subsequent popular depictions of Aesop.

Aesop plays a fairly prominent part in Plutarch's conversation piece "The Banquet of the Seven Sages" in the 1st century CE.[63] The fabulist then makes a cameo appearance in the novel A True Story by the 2nd-century satirist Lucian; when the narrator arrives at the Island of the Blessed, he finds that "Aesop the Phrygian was there, too; he acts as their jester."[64]

Beginning with the Heinrich Steinhowel edition of 1476, many translations of the fables into European languages, which also incorporated Planudes's "Life of Aesop", featured illustrations depicting him as a hunchback. The 1687 edition of Aesop's Fables with His Life: in English, French and Latin[65] included 31 engravings by Francis Barlow that show him as a dwarfish hunchback, and his facial features appear to accord with his statement in the text (p. 7), "I am a Negro."

The Spaniard Diego Velázquez painted a portrait of Aesop, dated 1639–40 and now in the collection of the Museo del Prado. The presentation is anachronistic and Aesop, while arguably not handsome, displays no physical deformities. It was partnered by another portrait of Menippus, a satirical philosopher equally of slave-origin. A similar philosophers series was painted by fellow Spaniard Jusepe de Ribera,[66] who is credited with two portraits of Aesop. "Aesop, poet of the fables" is in the El Escorial gallery and pictures him as an author leaning on a staff by a table which holds copies of his work, one of them a book with the name Hissopo on the cover.[67] The other is in the Museo de Prado, dated 1640–50 and titled "Aesop in beggar's rags." There he is also shown at a table, holding a sheet of paper in his left hand and writing with the other.[68] While the former hints at his lameness and deformed back, the latter only emphasises his poverty.

In 1690, French playwright Edmé Boursault's Les fables d'Esope (later known as Esope à la ville) premiered in Paris. A sequel, Esope à la cour[69] (Aesop at Court), was first performed in 1701; drawing on a mention in Herodotus 2.134-5[70] that Aesop had once been owned by the same master as Rhodopis, and the statement in Pliny 36.17[71] that she was Aesop's concubine as well, the play introduced Rodope as Aesop's mistress, a romantic motif that would be repeated in later popular depictions of Aesop.

Sir John Vanbrugh's comedy "Aesop"[72] was premièred at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, London, in 1697 and was frequently performed there for the next twenty years. A translation and adaptation of Boursault's Les fables d'Esope, Vanbrugh's play depicted a physically ugly Aesop acting as adviser to Learchus, governor of Cyzicus under King Croesus, and using his fables to solve romantic problems and quiet political unrest.[73]

In 1780, the anonymously authored novelette The History and Amours of Rhodope was published in London. The story casts the two slaves Rhodope and Aesop as unlikely lovers, one ugly and the other beautiful; ultimately Rhodope is parted from Aesop and marries the Pharaoh of Egypt. Some editions of the volume were illustrated with an engraving of a work by the painter Angelica Kauffman.[74] The Beautiful Rhodope in Love with Aesop pictures Rhodope leaning on an urn; she holds out her hand to Aesop, who is seated under a tree and turns his head to look at her. His right arm rests on a cage of doves, as he points to the captive state of both of them. Otherwise, the picture illustrates how different the couple are. Rhodope and Aesop lean on opposite elbows, gesture with opposite hands, and while Rhodope's hand is held palm upwards, Aesop's is held palm downwards. She stands while he sits; he is dressed in dark clothes, she in lighter shades. When the theme of their relationship was taken up again by Walter Savage Landor, in the two dialogues between the pair in his series of Imaginary Conversations, it is the difference in their ages that is most emphasised.[75] Théodore de Banville's 1893 comedy Ésope later dealt with Aesop and Rhodopis at the court of King Croesus in Sardis.[76]

Along with Fontana's Aesop Narrates His Fables to the Handmaids of Xanthus, two other 19th-century paintings show Aesop surrounded by listeners. Johann Michael Wittmer's Aesop Tells His Fables (1879) depicts the diminutive fabulist seated on a high pedestal, surrounded by an enraptured crowd. When Julian Russell Story's Aesop's Fables was exhibited in 1884, Henry James wrote to a correspondent: "Julian Story has a very clever & big Subject—Aesop telling fables ... He has a real talent but ... carries even further (with less ability) Sargent's danger—that of seeing the ugliness of things."[77][78] Conversely, Aesop Composing His Fables by Charles Landseer (1799–1879) depicts a writer in a household setting, handsome and wearing an earring.[79]

20th century genres

[edit]The 20th century saw the publication of three novels about Aesop. A. D. Wintle's Aesop (London: Gollancz, 1943) was a plodding fictional biography described in a review of the time as so boring that it makes the fables embedded in it seem "complacent and exasperating."[80] The two others, preferring the fictional Life to any approach to veracity, are genre works. In John Vornholt's The Fabulist (New York: Avon, 1993), "an ugly, mute slave is delivered from wretchedness by the gods and blessed with a wondrous voice. [It is] the tale of a most unlikely adventurer, dispatched to far and perilous realms to battle impossible beasts and terrible magicks."[81]

The other novel was George S. Hellman's Peacock's Feather (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1931).[82] Its unlikely plot made it the perfect vehicle for the 1946 Hollywood spectacular, Night in Paradise. A dashing (not ugly) Turhan Bey was cast as Aesop. In a plot containing "some of the most nonsensical screen doings of the year," he becomes entangled with the intended bride of King Croesus, a Persian princess played by Merle Oberon, and makes such a hash of it that he has to be rescued by the gods.[83] The 1953 teleplay Aesop and Rhodope takes up another theme of his fictional history.[citation needed] Written by Helene Hanff, it was broadcast on Hallmark Hall of Fame with Lamont Johnson playing Aesop.

The three-act A raposa e as uvas ("The Fox and the Grapes" 1953) marked Aesop's entry into Brazilian theatre. The three-act play was by Guilherme Figueiredo and has been performed in many countries, including a videotaped production in China in 2000 under the title Hu li yu pu tao or 狐狸与葡萄.[84] The play is described as an allegory about freedom with Aesop as the main character.[85]

Occasions on which Aesop was played as black include Richard Durham's Destination Freedom radio show broadcast (1949), where the drama "The Death of Aesop" portrayed him as an Ethiopian.[86][87] In 1971, Bill Cosby starred as Aesop in the TV production Aesop's Fables – The Tortoise and the Hare.[88][89] He was also played by Mhlekahi Mosiea in the 2010 South Africa adaptation of British playwright Peter Terson's musical Aesop's Fables.[90]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ West, pp. 106 and 119.

- ^ Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World (hereafter BNP) 1:256.

- ^ Callimachus. Iambus 2 (Loeb fragment 192)

- ^ Maximus of Tyre, Oration 36.1

- ^ Aristotle. Rhetoric 2.20 Archived 2011-05-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Herodotus. Histories 2.134 Archived 2012-05-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Plutarch. On the Delays of Divine Vengeance; Banquet of the Seven Sages; Life of Solon.

- ^ Kurke 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Perry, Ben Edwin. Introduction to Babrius and Phaedrus, pp. xxxviii–xlv.

- ^ BNP 1:256.

- ^ Phaedrus 1.2

- ^ William Hansen, review of Vita Aesopi: Ueberlieferung, Sprach und Edition einer fruehbyzantinischen Fassung des Aesopromans by Grammatiki A. Karla in Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2004.09.39 Archived 2010-05-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Leslie Kurke, "Aesop and the Contestation of Delphic Authority", in The Cultures Within Ancient Greek Culture: Contact, Conflict, Collaboration, ed. Carol Dougherty and Leslie Kurke, p. 77.

- ^ François Lissarrague, "Aesop, Between Man and Beast: Ancient Portraits and Illustrations", in Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, ed. Beth Cohen (hereafter, Lissarrague), p. 133.

- ^ Lissarrague, p. 113.

- ^ BNP 1:257; West, p. 121; Hägg, p. 47.

- ^ Aesop's Fables, ed. D.L. Ashliman, New York 2005, pp. xiii–xv, xxv–xxvi

- ^ Athenaeus 13.82 Archived 2010-12-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo 61b Archived 2010-01-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 2.5.42 Archived 2010-03-02 at the Wayback Machine: "He also composed a fable, in the style of Aesop, not very artistically, and it begins—Aesop one day did this sage counsel give / To the Corinthian magistrates: not to trust / The cause of virtue to the people's judgment."

- ^ Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 2.29.

- ^ Perry, Ben E. "Demetrius of Phalerum and the Aesopic Fables", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 93, 1962, pp. 287–346.

- ^ Ausonius, Epistles 12 Archived 2014-02-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ BNP 1:258–9; West; Niklas Holzberg, The Ancient Fable: An Introduction, pp. 12–13; see also Ainoi, Logoi, Mythoi: Fables in Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic Greek by Gert-Jan van Dijk and History of the Graeco-Latin Fable by Francisco Rodríguez Adrados.

- ^ The Aesop Romance, translated by Lloyd W. Daly, in Anthology of Ancient Greek Popular Literature, ed. William Hansen, p. 111.

- ^ Papademetriou, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Himerius, Orations 46.4, translated by Robert J. Penella in Man and the Word: The Orations of Himerius, p. 250.

- ^ See Lissarrage; Papademetriou; Compton, Victim of the Muses; Lefkowitz, "Ugliness and Value in the Life of Aesop" in Kakos: Badness and Anti-value in Classical Antiquity ed. Sluiter and Rosen.

- ^ Gert-Jan van Dijk, "Aesop" entry in The Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece, ed. Nigel Wilson, p. 18.

- ^ Frank M. Snowden, Jr., Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience (hereafter Snowden), p. 264.

- ^ "The Fitzwilliam Museum : The Art Fund". cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-04-11. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- ^ Ancient Coins of Phocis Archived 2010-08-28 at the Wayback Machine web page, accessed 11-12-2010.

- ^ William Martin Leake, Numismata Hellenica: A Catalogue of Greek Coins, p. 45. Archived 2014-02-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Theodor Panofka, Antikenkranz zum fünften Berliner Winckelmannsfest: Delphi und Melaine, p. 7 Archived 2016-12-29 at the Wayback Machine; an illustration of the coin in question follows p. 16.

- ^ Snowden, pp. 150–51 and 307-8.

- ^ Proth, Mario. Voyage au pays des peintres, Paris: Baschet, 1878, p. 240.

- ^ Robert Temple, Introduction to Aesop: The Complete Fables, pp. xx–xxi.

- ^ Driberg, 1932.

- ^ Lobban, Jr. 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Colvin, Ian Duncan (1914). Aesop in Politics. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. p. 3.

- ^ Kurke 2010, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Complete film at Black Junction

- ^ "Playwrights and Their Stage Works: Peter Terson". 4-wall.com. 1932-02-24. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ ""Backstage with 'Aesop's Fables' Director Mark Dornford-May", Sunday Times (Cape Town), June 7, 2010". Timeslive.co.za. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ Cape Argus, 31 May 2010

- ^ Elisonas, J.S.A. "Fables and Imitations: Kirishitan literature in the forest of simple letters", Bulletin of Portuguese Japanese Studies, Lisbon, 2002, pp. 13–17.

- ^ Marceau, Lawrence. From Aesop to Esopo to Isopo: Adapting the Fables in Late Medieval Japan, 2009. See abstract at p. 277 Archived 2012-03-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ van Dijk, Geert. "Aesop" in Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece, New York, 2006, p. 18. Archived 2016-12-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ BNP 1:257.

- ^ "'Imagines' 1.3". Theoi. Archived from the original on 2012-08-23. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ^ Antonio Bernat Vistarini, Tamás Sajó: Imago Veritatis. La circulación de la imagen simbólica entre fábula y emblema, Universitat de les Illes Balears, Studia Aurea 5 (2007), figures 2 and 1 Archived 2011-02-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Aesop frontispiece". Archived from the original on 2013-05-11. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ^ Schröder, Volker. "Versailles on Paper–Past and Present: The Labyrinth". Princeton University. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Aesop talks with a fox from one of his fables, on a medallion from a Greek drinking cup from about 470 bc, in the Gregorian Etruscan Museum, the Vatican". Kids Britannica. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ Lissarrague, p.137.

- ^ Paul Zanker, The Mask of Socrates, pp. 33–34.

- ^ The question is discussed by Lisa Trentin in "What's in a hump? Re-examining the hunchback in the Villa-Albani-Torlonia" in The Cambridge Classical Journal (New Series) December 2009 55 : pp 130–156; available as an academic reprint online

- ^ "Digicoll.library.wisc.edu". Digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-10-05. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ Attribution of these lines to Aesop is conjectural; see the reference and footnote in Kurke 2010, p 356.

- ^ Kurke 2010, p. 356.

- ^ "Digicoll.library.wisc.edu". Digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-10-05. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ "Pliny 36.17". Perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-10-04. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ "Plutarch • The Dinner of the Seven Wise Men". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- ^ Lucian, Verae Historiae (A True Story) 2.18 (Reardon translation).

- ^ Magic.lib.msu.edu. Magic.lib.msu.edu. 1687. Archived from the original on 2022-04-03. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ There is a note on another from this series on the Christies site Archived 2012-10-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Lessing-photo.com". Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ "Fineart-china.com". Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ Boursault, Edme (1788). Books.google.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-12-29. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ "Old.perseus.tufts.edu". Old.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ "Perseus.tufts.edu". Perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-10-04. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ Archive.org. London : Printed for J. Rivington ... [& 8 others]. 1776. Archived from the original on 2012-11-07. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ Mark Loveridge, A History of Augustan Fable (hereafter Loveridge), pp. 166–68.

- ^ Louise Fagan, A catalogue raisonné of the engraved works of William Woollett, The Fine Art Society (London 1885), pp.48–9

- ^ Landor, Walter Savage. Imaginary Conversations, volume 1, London: J. M. Dent & Co., 1891, "Aesop and Rhodopè" pp.7–28.

- ^ Banville, Théodore de. Ésope; comédie en trois actes, Paris: Charpentier et Fasquelle, 1893.

- ^ The Complete Letters of Henry James: Volume 2, University of Nebraska Press, 2019, p. 137 and note p. 140.

- ^ Aesop's Fables, Blouin art sales. Archived 2018-01-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Aesop Composing His Fables". artuk.org. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ "Fiction". The Spectator Archive. Archived from the original on 2014-08-17.

- ^ "The Fabulist by John Vornholt – FictionDB". fictiondb.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-27.

- ^ Aesop also appears as a character in Hellnan's 1935 novel Persian Conqueror, about Cyrus the Great.

- ^ Universal Horrors, McFarland, 2007, pp. 531–5 Archived 2016-12-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Figueiredo, Guilherme. "Hu li yu pu tao". youku.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Latin American Theater, Greenwood 2003, p.72 Archived 2016-12-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Death of Aesop". RichardDurham.com. 1949-02-13. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ "Destination Freedom". RichardDurham.com. Archived from the original on 2010-03-09. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ WorldCat

- ^ Available on YouTube

- ^ "AESOP'S FABLES opens at the Fugard Theatre". portobellopictures.com. Archived from the original on 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2014-09-08.

References

[edit]- Adrado, Francisco Rodriguez, 1999–2003. History of the Graeco-Latin Fable (three volumes). Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Anthony, Mayvis, 2006. The Legendary Life and Fables of Aesop.

- Cancik, Hubert, et al., 2002. Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Cohen, Beth (editor), 2000. Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. Includes "Aesop, Between Man and Beast: Ancient Portraits and Illustrations" by François Lissarrague.

- Dougherty, Carol and Leslie Kurke (editors), 2003. The Cultures Within Ancient Greek Culture: Contact, Conflict, Collaboration. Cambridge University Press. Includes "Aesop and the Contestation of Delphic Authority" by Leslie Kurke.

- Driberg, J. H., 1932. "Aesop", The Spectator, vol. 148 #5425, June 18, 1932, pp. 857–8.

- Hansen, William (editor), 1998. Anthology of Ancient Greek Popular Literature. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Includes The Aesop Romance (The Book of Xanthus the Philosopher and Aesop His Slave or The Career of Aesop), translated by Lloyd W. Daly.

- Hägg, Tomas, 2004. Parthenope: Selected Studies in Ancient Greek Fiction (1969–2004). Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. Includes Hägg's "A Professor and his Slave: Conventions and Values in The Life of Aesop", first published in 1997.

- Hansen, William, 2004. Review of Vita Aesopi: Ueberlieferung, Sprach und Edition einer fruehbyzantinischen Fassung des Aesopromans by Grammatiki A. Karla. Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2004.09.39.

- Holzberg, Niklas, 2002. The Ancient Fable: An Introduction, translated by Christine Jackson-Holzberg. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University press.

- Keller, John E., and Keating, L. Clark, 1993. Aesop's Fables, with a Life of Aesop. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press. English translation of the first Spanish edition of Aesop from 1489, La vida del Ysopet con sus fabulas historiadas including original woodcut illustrations; the Life of Aesop is a version from Planudes.

- Kurke, Leslie, 2010. Aesopic Conversations: Popular Tradition, Cultural Dialogue, and the Invention of Greek Prose. Princeton University Press.

- Leake, William Martin, 1856. Numismata Hellenica: A Catalogue of Greek Coins. London: John Murray.

- Loveridge, Mark, 1998. A History of Augustan Fable. Cambridge University Press.

- Lobban, Jr., Richard A. (2002). "Was Aesop a Nubian Kummaji (Folkteller)?". Northeast African Studies. 9 (1): 11–31. JSTOR 41931299.

- Lobban, Jr., Richard A., 2004. Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press.

- Panofka, Theodor, 1849. Antikenkranz zum fünften Berliner Winckelmannsfest: Delphi und Melaine. Berlin: J. Guttentag.

- Papademetriou, J. Th., 1997. Aesop as an Archetypal Hero. Studies and Research 39. Athens: Hellenic Society for Humanistic Studies.

- Penella, Robert J., 2007. Man and the Word: The Orations of Himerius." Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Perry, Ben Edwin (translator), 1965. Babrius and Phaedrus. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Philipott, Tho. (translator), 1687. Aesop's Fables with His Life: in English, French and Latin Archived 2022-04-03 at the Wayback Machine. London: printed for H. Hills jun. for Francis Barlow. Includes Philipott's English translation of Planudes' Life of Aesop with illustrations by Francis Barlow.

- Reardon, B. P. (editor), 1989. Collected Ancient Greek Novels. Berkeley: University of California Press. Includes An Ethiopian Story by Heliodorus, translated by J.R. Morgan, and A True Story by Lucian, translated by B.P. Reardon.

- Snowden, Jr., Frank M., 1970. Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Temple, Robert and Olivia (translators), 1998. Aesop: The Complete Fables. New York: Penguin Books.

- van Dijk, Gert-Jan, 1997. Ainoi, Logoi, Mythoi: Fables in Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic Greek. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers.

- West, M. L., 1984. "The Ascription of Fables to Aesop in Archaic and Classical Greece", La Fable (Vandœuvres–Genève: Fondation Hardt, Entretiens XXX), pp. 105–36.

- Wilson, Nigel, 2006. Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. New York: Routledge.

- Zanker, Paul, 1995. The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Anonymous, 1780. The History and Amours of Rhodope. London: Printed for E.M Diemer.

- Caxton, William, 1484. The history and fables of Aesop, Westminster. Modern reprint edited by Robert T. Lenaghan (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1967). Includes Caxton's Epilogue to the Fables, dated March 26, 1484.

- Compton, Todd, 1990. "The Trial of the Satirist: Poetic Vitae (Aesop, Archilochus, Homer) as Background for Plato's Apology", The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 111, No. 3 (Autumn 1990), pp. 330–347. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Daly, Lloyd W., 1961. Aesop without Morals: The Famous Fables, and a Life of Aesop, Newly Translated and Edited. New York and London: Thomas Yoseloff. Includes Daly's translation of The Aesop Romance.

- Gibbs, Laura. "Life of Aesop: The Wise Fool and the Philosopher", Journey to the Sea (online journal), issue 9, March 1, 2009.

- Sluiter, Ineke and Rosen, Ralph M. (editors), 2008. Kakos: Badness and Anti-value in Classical Antiquity. Mnemosyne: Supplements. History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity; 307. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. Includes "Ugliness and Value in the Life of Aesop" by Jeremy B. Lefkowitz.

- Perry, Ben Edwin, 1936. Studies in the text history of the life and fables of Aesop. Haverford (PA), American Philological Association

External links

[edit]- Works by Aesop in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Aesop at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Aesop at the Internet Archive

- Works by Aesop at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Vita Aesopi Online resources for the Life of Aesop

- Aesopica.net Over 600 fables in English, with Latin and Greek texts also; searchable

- Works by Aesop at Open Library

- Reprint Archived 2020-10-29 at the Wayback Machine of a German Fables edition of 1479 in letter press, with woodcuts on a reconstructed Gutenberg press and limp binding in leather or parchment

- Carlson Fable Collection at Creighton University includes 10,000 books and thousands of fable-related images and objects under the heading "Aesop's Artifacts"

- Esopus leben und Fabeln, German edition with many woodcuts from 1531.