Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hebrides

View on Wikipedia

The Hebrides (/ˈhɛbrɪdiːz/ HEB-rid-eez; Scottish Gaelic: Innse Gall, pronounced [ˈĩːʃə ˈkaul̪ˠ]; Old Norse: Suðreyjar, lit. 'Southern isles') are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebrides.

Key Information

These islands have a long history of occupation (dating back to the Mesolithic period), and the culture of the inhabitants has been successively influenced by the cultures of Celtic-speaking, Norse-speaking, and English-speaking peoples. This diversity is reflected in the various names given to the islands, which are derived from the different languages that have been spoken there at various points in their history.

The Hebrides are where much of Scottish Gaelic literature and Gaelic music has historically originated. Today, the economy of the islands is dependent on crofting, fishing, tourism, the oil industry, and renewable energy. The Hebrides have less biodiversity than mainland Scotland, but a significant number of seals and seabirds.

The islands have a combined area of 7,285 km2 (2,813 sq mi), and, as of 2011[update], a combined population of around 45,000.[1]

Geology, geography and climate

[edit]

The Hebrides have a diverse geology, ranging in age from Precambrian strata that are amongst the oldest rocks in Europe, to Paleogene igneous intrusions.[2][3][Note 1] Raised shore platforms in the Hebrides have been identified as strandflats, possibly formed during the Pliocene period and later modified by the Quaternary glaciations.[4]

The Hebrides can be divided into two main groups, separated from one another by the Minch to the north and the Sea of the Hebrides to the south. The Inner Hebrides lie closer to mainland Scotland and include Islay, Jura, Skye, Mull, Raasay, Staffa and the Small Isles. There are 36 inhabited islands in this group. The Outer Hebrides form a chain of more than 100 islands and small skerries located about 70 km (45 mi) west of mainland Scotland. Among them, 15 are inhabited. The main inhabited islands include Lewis and Harris, North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist, and Barra.

A complication is that there are various descriptions of the scope of the Hebrides. The Collins Encyclopedia of Scotland describes the Inner Hebrides as lying "east of the Minch". This definition would encompass all offshore islands, including those that lie in the sea lochs, such as Eilean Bàn and Eilean Donan, which might not ordinarily be described as "Hebridean". However, no formal definition exists.[5][6]

In the past, the Outer Hebrides were often referred to as the Long Isle (Scottish Gaelic: An t-Eilean Fada). Today, they are also sometimes known as the Western Isles, although this phrase can also be used to refer to the Hebrides in general.[Note 2]

The Hebrides have a cool, temperate climate that is remarkably mild and steady for such a northerly latitude, due to the influence of the Gulf Stream. In the Outer Hebrides, the average temperature is 6 °C (44 °F) in January and 14 °C (57 °F) in the summer. The average annual rainfall in Lewis is 1,100 mm (43 in), and there are between 1,100 and 1,200 hours of sunshine per annum (13%). The summer days are relatively long, and May through August is the driest period.[8]

Etymology

[edit]The earliest surviving written references to the islands were made circa 77 AD by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History: He states that there are 30 Hebudes, and makes a separate reference to Dumna, which Watson (1926) concluded refers unequivocally to the Outer Hebrides. About 80 years after Pliny the Elder, in 140–150 AD, Ptolemy (drawing on accounts of the naval expeditions of Agricola) writes that there are five Ebudes (possibly meaning the Inner Hebrides) and Dumna.[9][10][11] Later texts in classical Latin, by writers such as Solinus, use the forms Hebudes and Hæbudes.[12]

The name Ebudes (used by Ptolemy) may be pre-Celtic.[11] Ptolemy calls Islay "Epidion",[13] and the use of the letter "p" suggests a Brythonic or Pictish tribal name, Epidii,[14] because the root is not Gaelic.[15] Woolf (2012) has suggested that Ebudes may be "an Irish attempt to reproduce the word Epidii phonetically, rather than by translating it", and that the tribe's name may come from the root epos, meaning "horse".[16] Watson (1926) also notes a possible relationship between Ebudes and the ancient Irish Ulaid tribal name Ibdaig, and also the personal name of a king Iubdán (recorded in the Silva Gadelica).[11]

The names of other individual islands reflect their complex linguistic history. The majority are Norse or Gaelic, but the roots of several other names for Hebrides islands may have a pre-Celtic origin.[11] Adomnán, a 7th-century abbot of Iona, records Colonsay as Colosus and Tiree as Ethica, and both of these may be pre-Celtic names.[17] The etymology of Skye is complex and may also include a pre-Celtic root.[15] Lewis is Ljoðhús in Old Norse. Various suggestions have been made as to possible meanings of the name in Norse (for example, "song house"),[18] but the name is not of Gaelic origin, and the Norse provenance is questionable.[15]

The earliest comprehensive written list of Hebridean island names was compiled by Donald Monro in 1549. This list also provides the earliest written reference to the names of some of the islands.

The derivations of all the inhabited islands of the Hebrides and some of the larger uninhabited ones are listed below.

Outer Hebrides

[edit]Lewis and Harris is the largest island in Scotland and the third largest of the British Isles, after Great Britain and Ireland.[19] It incorporates Lewis in the north and Harris in the south, both of which are frequently referred to as individual islands, although they are joined by a land border. The island does not have a single common name in either English or Gaelic and is referred to as "Lewis and Harris", "Lewis with Harris", "Harris with Lewis" etc. For this reason it is treated as two separate islands below.[20] The derivation of Lewis may be pre-Celtic (see above) and the origin of Harris is no less problematic. In the Ravenna Cosmography, Erimon may refer to Harris[21] (or possibly the Outer Hebrides as a whole). This word may derive from the Ancient Greek: ἐρῆμος (erimos "desert".[22] The origin of Uist (Old Norse: Ívist) is similarly unclear.[15]

| Island | Derivation | Language | Meaning | Munro (1549) | Modern Gaelic name | Alternative Derivations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baleshare | Am Baile Sear | Gaelic | east town[23] | Baile Sear | |||

| Barra | Barrey[24] | Gaelic + Norse | Finbar's island[25] | Barray | Barraigh | Old Gaelic barr, a summit.[24] | |

| Benbecula | Peighinn nam Fadhla | Gaelic | pennyland of the fords[26] | Beinn nam Fadhla | "little mountain of the ford" or "herdsman's mountain"[23] | ||

| Berneray | Bjarnarey[24] | Norse | Bjorn's island[26] | Beàrnaraigh | bear island[23] | ||

| Eriskay | Uruisg + ey | Gaelic + Norse | goblin or water nymph island[23] | Eriskeray | Èirisgeigh | Erik's island[23][27] | |

| Flodaigh | Norse | float island[28] | Flodaigh | ||||

| Great Bernera | Bjarnarey[24] | Norse | Bjorn's island[29] | Berneray-Moir | Beàrnaraigh Mòr | bear island[29] | |

| Grimsay[Note 3] | Grímsey | Norse | Grim's island[23] | Griomasaigh | |||

| Grimsay[Note 4] | Grímsey | Norse | Grim's island[23] | Griomasaigh | |||

| Harris | Erimon?[21] | Ancient Greek? | desert? | Harrey | na Hearadh | Ptolemy's Adru. In Old Norse (and in modern Icelandic), a Hérað is a type of administrative district.[30] Alternatives are the Norse haerri, meaning "hills" and Gaelic na h-airdibh meaning "the heights".[29] | |

| Lewis | Limnu | Pre-Celtic? | marshy | Lewis | Leòdhas | Ptolemy's Limnu is literally "marshy". The Norse Ljoðhús may mean "song house" – see above.[15][30] | |

| North Uist | English + Pre-Celtic?[15] | Ywst | Uibhist a Tuath | "Uist" may possibly be "corn island"[31] or "west"[29] | |||

| Scalpay | Skalprey[29] | Norse | scallop island[29] | Scalpay of Harray | Sgalpaigh na Hearadh | ||

| Seana Bhaile | Gaelic | old township | Seana Bhaile | ||||

| South Uist | English + Pre-Celtic? | Uibhist a Deas | See North Uist | ||||

| Vatersay | Vatrsey?[32] | Norse | water island[33] | Wattersay | Bhatarsaigh | fathers' island, priest island, glove island, wavy island[29] |

Inner Hebrides

[edit]There are various examples of earlier names for Inner Hebridean islands that were Gaelic, but these names have since been completely replaced. For example, Adomnán records Sainea, Elena, Ommon and Oideacha in the Inner Hebrides. These names presumably passed out of usage in the Norse era, and the locations of the islands they refer to are not clear.[34] As an example of the complexity: Rona may originally have had a Celtic name, then later a similar-sounding Norse name, and then still later a name that was essentially Gaelic again, but with a Norse "øy" or "ey" ending.[35] (See Rona, below.)

| Island | Derivation | Language | Meaning | Munro (1549) | Modern Gaelic name | Alternative Derivations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canna | Cana | Gaelic | porpoise island[36] | Kannay | Eilean Chanaigh | possibly Old Gaelic cana, "wolf-whelp", or Norse kneøy, "knee island"[36] |

| Coll | Colosus | Pre-Celtic | Colla | possibly Gaelic coll – a hazel[37] | ||

| Colonsay | Kolbein's + ey | Norse[38] | Kolbein's island | Colnansay | Colbhasa | possibly Norse for "Columba's island"[39] |

| Danna | Daney[40] | Norse | Dane island[40] | Danna | Unknown[41] | |

| Easdale | Eisdcalfe | Eilean Èisdeal | Eas is "waterfall" in Gaelic and dale is the Norse for "valley".[42] However the combination seems inappropriate for this small island. Also known as Ellenabeich – "island of the birches"[43] | |||

| Eigg | Eag | Gaelic | a notch[44] | Egga | Eige | Also called Eilean Nimban More – "island of the powerful women" until the 16th century.[45] |

| Eilean Bàn | Gaelic | white isle | Naban | Eilean Bàn | ||

| Eilean dà Mhèinn | Gaelic | |||||

| Eilean Donan | Gaelic | island of Donnán | Eilean Donnain | |||

| Eilean Shona | Gaelic + Norse | sea island[46] | Eilean Seòna | Adomnán records the pre-Norse Gaelic name of Airthrago – the foreshore isle".[47] | ||

| Eilean Tioram | Gaelic | dry island | ||||

| Eriska | Erik's + ey | Norse | Erik's island[27] | Aoraisge | ||

| Erraid | Arthràigh? | Gaelic | foreshore island[46] | Erray | Eilean Earraid | |

| Gigha | Guðey[48][49] | Norse | "good island" or "God island"[50] | Gigay | Giogha | Various including the Norse Gjáey – "island of the geo" or "cleft", or "Gydha's isle".[51] |

| Gometra | Goðrmaðrey[52] | Norse | "The good-man's island", or "God-man's island"[52] | Gòmastra | "Godmund's island".[53][49] | |

| Iona | Hí | Gaelic | Possibly "yew-place" | Colmkill | Ì Chaluim Chille | Numerous. Adomnán uses Ioua insula which became "Iona" through misreading.[54] |

| Islay | Pre-Celtic | Ila | Ìle | Various – see above | ||

| Isle of Ewe | Eo[55] | English + Gaelic | isle of yew | Ellan Ew | possibly Gaelic eubh, "echo" | |

| Jura | Djúrey[40] | Norse | deer island[56] | Duray | Diùra | Norse: Jurøy – "udder island"[56] |

| Kerrera | Kjarbarey[57] | Norse | Kjarbar's island[58] | Cearrara | Norse: ciarrøy – "brushwood island"[58] or "copse island"[59] | |

| Lismore | Lios Mòr | Gaelic | big garden/enclosure[60] | Lismoir | Lios Mòr | |

| Luing | Gaelic | ship island[61] | Lunge | An t-Eilean Luinn | Norse: lyng – heather island[61] or pre-Celtic[62] | |

| Lunga | Langrey | Norse | longship isle[63] | Lungay | Lunga | Gaelic long is also "ship"[63] |

| Muck | Eilean nam Muc | Gaelic | isle of pigs[64] | Swynes Ile | Eilean nam Muc | Eilean nam Muc-mhara- "whale island". John of Fordun recorded it as Helantmok – "isle of swine".[64] |

| Mull | Malaios | Pre-Celtic[15] | Mull | Muile | Recorded by Ptolemy as Malaios[13] possibly meaning "lofty isle".[11] In Norse times it became Mýl.[15] | |

| Oronsay | Ørfirisey[65] | Norse | ebb island[66] | Ornansay | Orasaigh | Norse: "Oran's island"[39] |

| Raasay | Raasey | Norse | roe deer island[67] | Raarsay | Ratharsair | Rossøy – "horse island"[67] |

| Rona | Hrauney or Ròney | Norse or Gaelic/Norse | "rough island" or "seal island" | Ronay | Rònaigh | |

| Rum | Pre-Celtic[68] | Ronin | Rùm | Various including Norse rõm-øy for "wide island" or Gaelic ì-dhruim – "isle of the ridge"[69] | ||

| Sanday | Sandey[70] | Norse | sandy island[36] | Sandaigh | ||

| Scalpay | Skalprey[71] | Norse | scallop island[72] | Scalpay | Sgalpaigh | Norse: "ship island"[73] |

| Seil | Sal? | Probably pre-Celtic[74] | "stream"[43] | Seill | Saoil | Gaelic: sealg – "hunting island"[43] |

| Shuna | Unknown | Norse | Possibly "sea island"[46] | Seunay | Siuna | Gaelic sidhean – "fairy hill"[75] |

| Skye | Scitis[76] | Pre-Celtic? | Possibly "winged isle"[77] | Skye | An t-Eilean Sgitheanach | Numerous – see above |

| Soay | So-ey | Norse | sheep island | Soa Urettil | Sòdhaigh | |

| Tanera Mor | Hafrarey[78] | From Old Norse: hafr, he-goat | Hawrarymoir(?) | Tannara Mòr | Brythonic: Thanaros, the thunder god,[79] island of the haven[79] | |

| Tiree | Tìr + Eth, Ethica | Gaelic + unknown | Unknown[17] | Tiriodh | Norse: Tirvist of unknown meaning and numerous Gaelic versions, some with a possible meaning of "land of corn"[17] | |

| Ulva | Ulfey[32] | Norse | wolf island[80][32] | Ulbha | Ulfr's island[80] |

Uninhabited islands

[edit]

The names of uninhabited islands follow the same general patterns as the inhabited islands. (See the list, below, of the ten largest islands in the Hebrides and their outliers.)

The etymology of the name "St Kilda", a small archipelago west of the Outer Hebrides, and the name of its main island, "Hirta," is very complex. No saint is known by the name of Kilda, so various other theories have been proposed for the word's origin, which dates from the late 16th century.[81] Haswell-Smith (2004) notes that the full name "St Kilda" first appears on a Dutch map dated 1666, and that it may derive from the Norse phrase sunt kelda ("sweet wellwater") or from a mistaken Dutch assumption that the spring Tobar Childa was dedicated to a saint. (Tobar Childa is a tautological placename, consisting of the Gaelic and Norse words for well, i.e., "well well").[82] Similarly unclear is the origin of the Gaelic for "Hirta", Hiort, Hirt, or Irt[83] a name for the island that long pre-dates the name "St Kilda". Watson (1926) suggests that it may derive from the Old Irish word hirt ("death"), possibly a reference to the often lethally dangerous surrounding sea.[84] Maclean (1977) notes that an Icelandic saga about an early 13th-century voyage to Ireland refers to "the islands of Hirtir", which means "stags" in Norse, and suggests that the outline of the island of Hirta resembles the shape of a stag, speculating that therefore the name "Hirta" may be a reference to the island's shape.[85]

The etymology of the names of small islands may be no less complex and elusive. In relation to Dubh Artach, Robert Louis Stevenson believed that "black and dismal" was one translation of the name, noting that "as usual, in Gaelic, it is not the only one."[86]

| Island | Derivation | Language | Meaning | Munro (1549) | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceann Ear | Ceann Ear | Gaelic | east headland | ||

| Hirta | Hirt | Possibly Old Irish | death | Hirta | Numerous – see above |

| Mingulay | Miklaey[87] | Norse | big island[88][87] | Megaly | "Main hill island".[89] Murray (1973) states that the name "appropriately means Bird Island".[90] |

| Pabbay | Papaey[87] | Norse | priest island[91] | Pabay | |

| Ronay | Norse | rough island[92] | |||

| Sandray | Sandray[93] | Norse | sand island[73] | Sanderay | beach island[70] |

| Scarba | Norse | cormorant island[74] | Skarbay | Skarpey, sharp or infertile island[71] | |

| Scarp | Skarpoe[94] | Norse | "barren"[74] or "stony" | Scarpe | |

| Taransay | Norse | Taran's island[95] | Tarandsay | Haraldsey, Harold's island[78] | |

| Wiay | Búey[40] | Norse | From bú, a settlement | Possibly "house island"[96] |

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]

The Hebrides were settled during the Mesolithic era around 6500 BC or earlier, after the climatic conditions improved enough to sustain human settlement. Occupation at a site on Rùm is dated to 8590 ±95 uncorrected radiocarbon years BP, which is amongst the oldest evidence of occupation in Scotland.[97][98] There are many examples of structures from the Neolithic period, the finest example being the standing stones at Callanish, dating to the 3rd millennium BC.[99] Cladh Hallan, a Bronze Age settlement on South Uist is the only site in the UK where prehistoric mummies have been found.[100][101]

Celtic era

[edit]In 55 BC, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote that there was an island called Hyperborea (which means "beyond the North Wind"), where a round temple stood from which the moon appeared only a little distance above the earth every 19 years. This may have been a reference to the stone circle at Callanish.[102]

A traveller called Demetrius of Tarsus related to Plutarch the tale of an expedition to the west coast of Scotland in or shortly before 83 AD. He stated it was a gloomy journey amongst uninhabited islands, but he had visited one which was the retreat of holy men. He mentioned neither the druids nor the name of the island.[103]

The first written records of native life begin in the 6th century AD, when the founding of the kingdom of Dál Riata took place.[104] This encompassed roughly what is now Argyll and Bute and Lochaber in Scotland and County Antrim in Ireland.[105] The figure of Columba looms large in any history of Dál Riata, and his founding of a monastery on Iona ensured that the kingdom would be of great importance in the spread of Christianity in northern Britain. However, Iona was far from unique. Lismore in the territory of the Cenél Loairn, was sufficiently important for the death of its abbots to be recorded with some frequency and many smaller sites, such as on Eigg, Hinba, and Tiree, are known from the annals.[106]

North of Dál Riata, the Inner and Outer Hebrides were nominally under Pictish control, although the historical record is sparse. Hunter (2000) states that in relation to King Bridei I of the Picts in the sixth century: "As for Shetland, Orkney, Skye and the Western Isles, their inhabitants, most of whom appear to have been Pictish in culture and speech at this time, are likely to have regarded Bridei as a fairly distant presence."[107]

Norwegian control

[edit]

Viking raids began on Scottish shores towards the end of the 8th century, and the Hebrides came under Norse control and settlement during the ensuing decades, especially following the success of Harald Fairhair at the Battle of Hafrsfjord in 872.[108][109] In the Western Isles Ketill Flatnose may have been the dominant figure of the mid 9th century, by which time he had amassed a substantial island realm and made a variety of alliances with other Norse leaders. These princelings nominally owed allegiance to the Norwegian crown, although in practice the latter's control was fairly limited.[110] Norse control of the Hebrides was formalised in 1098 when Edgar of Scotland formally signed the islands over to Magnus III of Norway.[111] The Scottish acceptance of Magnus III as King of the Isles came after the Norwegian king had conquered Orkney, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man in a swift campaign earlier the same year, directed against the local Norwegian leaders of the various island petty kingdoms. By capturing the islands Magnus imposed a more direct royal control, although at a price. His skald Bjorn Cripplehand recorded that in Lewis "fire played high in the heaven" as "flame spouted from the houses" and that in the Uists "the king dyed his sword red in blood".[111][Note 5]

The Hebrides were now part of the Kingdom of the Isles, whose rulers were themselves vassals of the Kings of Norway. This situation lasted until the partitioning of the Western Isles in 1156, at which time the Outer Hebrides remained under Norwegian control while the Inner Hebrides broke out under Somerled, the Norse-Gael kinsman of the Manx royal house.[113]

Following the ill-fated 1263 expedition of Haakon IV of Norway, the Outer Hebrides and the Isle of Man were yielded to the Kingdom of Scotland as a result of the 1266 Treaty of Perth.[114] Although their contribution to the islands can still be found in personal and place names, the archaeological record of the Norse period is very limited. The best known find is the Lewis chessmen, which date from the mid 12th century.[115]

Scottish control

[edit]

As the Norse era drew to a close, the Norse-speaking princes were gradually replaced by Gaelic-speaking clan chiefs including the MacLeods of Lewis and Harris, Clan Donald and MacNeil of Barra.[112][116][Note 6] This transition did little to relieve the islands of internecine strife although by the early 14th century the MacDonald Lords of the Isles, based on Islay, were in theory these chiefs' feudal superiors and managed to exert some control.[120]

The Lords of the Isles ruled the Inner Hebrides as well as part of the Western Highlands as subjects of the King of Scots until John MacDonald, fourth Lord of the Isles, squandered the family's powerful position. A rebellion by his nephew, Alexander of Lochalsh provoked an exasperated James IV to forfeit the family's lands in 1493.[121]

In 1598, King James VI authorised some "Gentleman Adventurers" from Fife to civilise the "most barbarous Isle of Lewis".[122] Initially successful, the colonists were driven out by local forces commanded by Murdoch and Neil MacLeod, who based their forces on Bearasaigh in Loch Ròg. The colonists tried again in 1605 with the same result, but a third attempt in 1607 was more successful and in due course Stornoway became a Burgh of Barony.[122][123] By this time, Lewis was held by the Mackenzies of Kintail (later the Earls of Seaforth), who pursued a more enlightened approach, investing in fishing in particular. The Seaforths' royalist inclinations led to Lewis becoming garrisoned during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms by Cromwell's troops, who destroyed the old castle in Stornoway.[124]

Early British era

[edit]

With the implementation of the Treaty of Union in 1707, the Hebrides became part of the new Kingdom of Great Britain, but the clans' loyalties to a distant monarch were not strong. A considerable number of islesmen "came out" in support of the Jacobite Earl of Mar in the 1715 and again in the 1745 rising including Macleod of Dunvegan and MacLea of Lismore.[126][127] The aftermath of the decisive Battle of Culloden, which effectively ended Jacobite hopes of a Stuart restoration, was widely felt.[128] The British government's strategy was to estrange the clan chiefs from their kinsmen and turn their descendants into English-speaking landlords whose main concern was the revenues their estates brought rather than the welfare of those who lived on them.[129] This may have brought peace to the islands, but over the following century the clan system was broken up and islands of the Hebrides became a series of landed estates.[129][130]

The early 19th century was a time of improvement and population growth. Roads and quays were built; the slate industry became a significant employer on Easdale and surrounding islands; and the construction of the Crinan and Caledonian canals and other engineering works such as Clachan Bridge improved transport and access.[131] However, in the mid-19th century, the inhabitants of many parts of the Hebrides were devastated by the Clearances, which destroyed communities throughout the Highlands and Islands as the human populations were evicted and replaced with sheep farms.[132] The position was exacerbated by the failure of the islands' kelp industry that thrived from the 18th century until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815[133][134] and large scale emigration became endemic.[135]

As Iain Mac Fhearchair, a Gaelic poet from South Uist, wrote for his countrymen who were obliged to leave the Hebrides in the late 18th century, emigration was the only alternative to "sinking into slavery" as the Gaels had been unfairly dispossessed by rapacious landlords.[136] In the 1880s, the "Battle of the Braes" involved a demonstration against unfair land regulation and eviction, stimulating the calling of the Napier Commission. Disturbances continued until the passing of the 1886 Crofters' Act.[137]

Language

[edit]

The residents of the Hebrides have spoken a variety of different languages during the long period of human occupation.

It is assumed that Pictish must once have predominated in the northern Inner Hebrides and Outer Hebrides.[107][138] The Scottish Gaelic language arrived from Ireland due to the growing influence of the kingdom of Dál Riata from the 6th century AD onwards, and became the dominant language of the southern Hebrides at that time.[139][140] For a few centuries, the military might of the Gall-Ghàidheil meant that Old Norse was prevalent in the Hebrides. North of Ardnamurchan, the place names that existed prior to the 9th century have been all but obliterated.[140] The Old Norse name for the Hebrides during the Viking occupation was Suðreyjar, which means "Southern Isles"; in contrast to the Norðreyjar, or "Northern Isles" of Orkney and Shetland.[141]

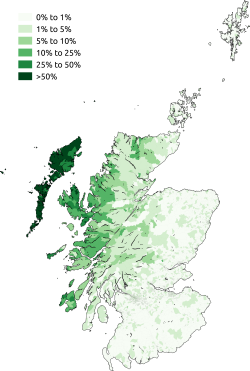

South of Ardnamurchan, Gaelic place names are more common,[140] and after the 13th century, Gaelic became the main language of the entire Hebridean archipelago. Due to Scots and English being favoured in government and the educational system, the Hebrides have been in a state of diglossia since at least the 17th century. The Highland Clearances of the 19th century accelerated the language shift away from Scottish Gaelic, as did increased migration and the continuing lower status of Gaelic speakers.[142] Nevertheless, as late as the end of the 19th century, there were significant populations of monolingual Gaelic speakers, and the Hebrides still contain the highest percentages of Gaelic speakers in Scotland. This is especially true of the Outer Hebrides, where a slim majority speak the language.[142][143] The Scottish Gaelic college, Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, is based on Skye and Islay.[144]

Ironically, given the status of the Western Isles as the last Gaelic-speaking stronghold in Scotland, the Gaelic language name for the islands – Innse Gall – means "isles of the foreigners"; from the time when they were under Norse colonisation.[145]

Modern economy

[edit]

For those who remained, new economic opportunities emerged through the export of cattle, commercial fishing and tourism.[146] Nonetheless, emigration and military service became the choice of many[147] and the archipelago's populations continued to dwindle throughout the late 19th century and for much of the 20th century.[148][149] Lengthy periods of continuous occupation notwithstanding, many of the smaller islands were abandoned.[150]

There were, however, continuing gradual economic improvements, among the most visible of which was the replacement of the traditional thatched blackhouse with accommodation of a more modern design[151] and with the assistance of Highlands and Islands Enterprise many of the islands' populations have begun to increase after decades of decline.[1] The discovery of substantial deposits of North Sea oil in 1965 and the renewables sector have contributed to a degree of economic stability in recent decades. For example, the Arnish yard has had a chequered history but has been a significant employer in both the oil and renewables industries.[152]

The widespread immigration of mainlanders, particularly non-Gaelic speakers, has been a subject of controversy.[153][154]

Agriculture practised by crofters remained popular in the 21st century in the Hebrides; crofters own a small property but often share a large common grazing area. Various types of funding are available to crofters to help supplement their incomes, including the "Basic Payment Scheme, the suckler beef support scheme, the upland sheep support scheme and the Less Favoured Area support scheme". One reliable source discussed the Crofting Agricultural Grant Scheme (CAGS) in March 2020:[155]

the scheme "pays up to £25,000 per claim in any two-year period, covering 80% of investment costs for those who are under 41 and have had their croft less than five years. Older, more established crofters can get 60% grants".

Media and the arts

[edit]Music

[edit]

Many contemporary Gaelic musicians have roots in the Hebrides, including vocalist and multi-instrumentalist Julie Fowlis (North Uist),[156] Catherine-Ann MacPhee (Barra), Kathleen MacInnes of the band Capercaillie (South Uist), and Ishbel MacAskill (Lewis). All of these singers have composed their own music in Scottish Gaelic, with much of their repertoire stemming from Hebridean vocal traditions, such as puirt à beul ("mouth music", similar to Irish lilting) and òrain luaidh (waulking songs). This tradition includes many songs composed by little-known or anonymous poets, well-before the 1800s, such as "Fear a' bhàta", "Ailein duinn", "Hùg air a' bhonaid mhòir" and "Alasdair mhic Cholla Ghasda". Several of Runrig's songs are inspired by the archipelago; Calum and Ruaraidh Dòmhnallach were raised on North Uist[157] and Donnie Munro on Skye.[158]

Literature

[edit]The Gaelic poet Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair spent much of his life in the Hebrides and often referred to them in his poetry, including in An Airce and Birlinn Chlann Raghnaill.[159] The best known Gaelic poet of her era, Màiri Mhòr nan Òran (Mary MacPherson, 1821–98), embodied the spirit of the land agitation of the 1870s and 1880s. This, and her powerful evocation of the Hebrides—she was from Skye—has made her among the most enduring Gaelic poets.[160] Allan MacDonald (1859–1905), who spent his adult life on Eriskay and South Uist, composed hymns and verse in honour of the Blessed Virgin, the Christ Child, and the Eucharist. In his secular poetry, MacDonald praised the beauty of Eriskay and its people. In his verse drama, Parlamaid nan Cailleach (The Old Wives' Parliament), he lampooned the gossiping of his female parishioners and local marriage customs.[161]

In the 20th century, Murdo Macfarlane of Lewis wrote Cànan nan Gàidheal, a well-known poem about the Gaelic revival in the Outer Hebrides.[162] Sorley MacLean, the most respected 20th-century Gaelic writer, was born and raised on Raasay, where he set his best known poem, Hallaig, about the devastating effect of the Highland Clearances.[163] Aonghas Phàdraig Caimbeul, raised on South Uist and described by MacLean as "one of the few really significant living poets in Scotland, writing in any language" (West Highland Free Press, October 1992)[164] wrote the Scottish Gaelic-language novel An Oidhche Mus do Sheòl Sinn which was voted in the Top Ten of the 100 Best-Ever Books from Scotland.

Virginia Woolf's To The Lighthouse is set on the Isle of Skye, part of the Inner Hebrides.

Film

[edit]- The area around the Inaccessible Pinnacle of Sgurr Dearg of Skye provided the setting for the Scottish Gaelic feature film Seachd: The Inaccessible Pinnacle (2006).[165] The script was written by the actor, novelist, and poet Aonghas Phàdraig Chaimbeul, who also starred in the movie.[164]

- An Drochaid, an hour-long documentary in Scottish Gaelic, was made for BBC Alba documenting the battle to remove tolls from the Skye bridge.[166][167]

- The 1973 film, The Wicker Man, is set on the fictional Hebridean island of Summerisle. The filming itself took place in Galloway and Skye[168][169]

- I Know Where I'm Going! (1945) is set on and was filmed on locations on Mull and the whirlpool in the Gulf of Corryvreckan.[170]

Video games

[edit]- The 2012 exploration adventure game Dear Esther by developer The Chinese Room is set on an unnamed island in the Hebrides.

- The Hebrides are featured in the 2021 video game Battlefield 2042 as the setting of the multiplayer map Redacted, which was introduced into the game in October 2023.[171]

Influence on visitors

[edit]- J.M. Barrie's Marie Rose contains references to Harris inspired by a holiday visit to Amhuinnsuidhe Castle and he wrote a screenplay for the 1924 film adaptation of Peter Pan whilst on Eilean Shona.[172][173][174][175]

- The Hebrides, also known as Fingal's Cave, is a famous overture composed by Felix Mendelssohn while residing on these islands, while Granville Bantock composed the Hebridean Symphony.

- Enya's song "Ebudæ" from Shepherd Moons is named after the Hebrides (see below).[176]

- The 1973 British horror film The Wicker Man is set on the fictional Hebridean island of Summerisle.[177]

- The 2011 British romantic comedy The Decoy Bride is set on the fictional Hebrides island of Hegg.[178]

Natural history

[edit]In some respects the Hebrides lack biodiversity in comparison to mainland Britain; for example, there are only half as many mammalian species.[179] However, these islands provide breeding grounds for many important seabird species including the world's largest colony of northern gannets.[180] Avian life includes the corncrake, red-throated diver, rock dove, kittiwake, tystie, Atlantic puffin, goldeneye, golden eagle and white-tailed sea eagle.[181][182] The latter was re-introduced to Rùm in 1975 and has successfully spread to various neighbouring islands, including Mull.[183] There is a small population of red-billed chough concentrated on the islands of Islay and Colonsay.[184]

Red deer are common on the hills and the grey seal and common seal are present around the coasts of Scotland. Colonies of seals are found on Oronsay and the Treshnish Isles.[185][186] The rich freshwater streams contain brown trout, Atlantic salmon and water shrew.[187][188] Offshore, minke whales, orcas, basking sharks, porpoises and dolphins are among the sealife that can be seen.[189][190]

Heather moor containing ling, bell heather, cross-leaved heath, bog myrtle and fescues is abundant and there is a diversity of Arctic and alpine plants including Alpine pearlwort and mossy cyphal.[191]

Loch Druidibeg on South Uist is a national nature reserve owned and managed by Scottish Natural Heritage. The reserve covers 1,677 hectares across the whole range of local habitats.[192] Over 200 species of flowering plants have been recorded on the reserve, some of which are nationally scarce.[193] South Uist is considered the best place in the UK for the aquatic plant slender naiad, which is a European Protected Species.[194][195]

Hedgehogs are not native to the Outer Hebrides—they were introduced in the 1970s to reduce garden pests—and their spread poses a threat to the eggs of ground nesting wading birds. In 2003, Scottish Natural Heritage undertook culls of hedgehogs in the area although these were halted in 2007 due to protests. Trapped animals were relocated to the mainland.[196][197]

See also

[edit]References and footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Rollinson (1997) states that the oldest rocks in Europe have been found "near Gruinard Bay" on the Scottish mainland. Gillen (2003) p. 44 indicates the oldest rocks in Europe are found "in the Northwest Highlands and Outer Hebrides". McKirdy, Alan Gordon, John & Crofts, Roger (2007) Land of Mountain and Flood: The Geology and Landforms of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. p. 93 state of the Lewisian gneiss bedrock of much of the Outer Hebrides that "these rocks are amongst the oldest to be found anywhere on the planet". Other (non-geologist) sources sometimes claim that the rocks of Lewis and Harris are "the oldest in Britain", meaning that they are the oldest deposits of large bedrock. As Rollinson makes clear, Lewis and Harris is not the location of the oldest small outcrop.

- ^ Murray (1973) notes that "Western Isles" has tended to mean "Outer Hebrides" since the creation of the Na h-Eileanan an Iar or Western Isles parliamentary constituency in 1918. Murray also notes that "Gneiss Islands" – a reference to the underlying geology – is another name used to refer to the Outer Hebrides, but that its use is "confined to books".[7]

- ^ There are two inhabited islands called "Grimsay" or Griomasaigh that are joined to Benbecula by a road causeway, one to the north at grid reference NF855572 and one to the south east at grid reference NF831473.

- ^ See above note.

- ^ Thompson (1968) provides a more literal translation: "Fire played in the fig-trees of Liodhus; it mounted up to heaven. Far and wide the people were driven to flight. The fire gushed out of the houses".[112]

- ^ The transitional relationships between Norse and Gaelic-speaking rulers are complex. The Gall-Ghàidhels who dominated much of the Irish Sea region and western Scotland at this time were of joint Gaelic and Scandinavian origin. When Somerled wrested the southern Inner Hebrides from Godred the Black in 1156, this was the beginnings of a break with nominal Norse rule in the Hebrides. Godred remained the ruler of Mann and the Outer Hebrides, but two years later Somerled's invasion of the former caused him to flee to Norway. Norse control was further weakened in the ensuring century, but the Hebrides were not formally ceded by Norway until 1266.[117][118] The transitions from one language to another are also complex. For example, many Scandinavian sources from this period of time typically refer to individuals as having a Scandinavian first name and a Gaelic by-name.[119]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. (pdf) Retrieved 22 January 2011. Archived 22 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rollinson, Hugh (September 1997). "Britain's oldest rocks" Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Geology Today. 13 no. 5 pp. 185–190.

- ^ Gillen, Con (2003). Geology and landscapes of Scotland. Harpenden. Terra Publishing. Pages 44 and 142.

- ^ Dawson, Alastair G.; Dawson, Sue; Cooper, J. Andrew G.; Gemmell, Alastair; Bates, Richard (2013). "A Pliocene age and origin for the strandflat of the Western Isles of Scotland: a speculative hypothesis". Geological Magazine. 150 (2): 360–366. Bibcode:2013GeoM..150..360D. doi:10.1017/S0016756812000568. S2CID 130965005.

- ^ Keay & Keay (1994) p. 507.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (1978) states: "Hebrides – group of islands of the west coast of Scotland extending in an arc between 55.35 and 58.30 N and 5.26 and 8.40 W." These coordinates include Gigha, St Kilda and everything up to Cape Wrath – although not North Rona.

- ^ Murray (1973) p. 32.

- ^ Thompson (1968) pp. 24–26.

- ^ Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 11–13.

- ^ Watson (1994) pp. 40–41

- ^ a b c d e Watson (1994) p. 38

- ^ Louis Deroy & Marianne Mulon (1992) Dictionnaire de noms de lieux, Paris: Le Robert, article "Hébrides".

- ^ a b Watson (1994) p. 37.

- ^ Watson (1994) p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides – A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith et al (2007) p. 487.

- ^ Woolf, Alex (2012) Ancient Kindred? Dál Riata and the Cruthin Archived 2 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Academia.edu. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Watson (1994) p. 85-86.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 80.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 262.

- ^ Thompson (1968) p. 13.

- ^ a b "The Roman Map of Britain Maiona (Erimon) 7 Lougis Erimon Isles of Harris and Lewis, Outer Hebrides " Archived 27 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine romanmap.com. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Megaw, J.V. S. and SIMPSON, D.A. (1960) "A short cist burial on North Uist and some notes on the prehistory of the Outer Isles in the second millennium BC" Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (pdf) p. 72 Proc Soc Antiq Scot. archaeologydataservice.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 236.

- ^ a b c d Gammeltoft 2006, p. 68.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 17.

- ^ a b Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 19.

- ^ a b Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 46.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e f g Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 218.

- ^ a b Mac an Tàilleir (2003).

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 116.

- ^ a b c Gammeltoft 2006, p. 80.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 117.

- ^ Watson (1994) p. 93.

- ^ Gammeltoft (2010) pp. 482, 486.

- ^ a b c Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 143.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 118.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 31.

- ^ a b Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 52.

- ^ a b c d Gammeltoft 2006, p. 69.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 38.

- ^ "Etymology of British place-names" Archived 9 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Pbenyon. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 76.

- ^ Watson (1994) p. 85.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 134.

- ^ a b c Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 105.

- ^ Watson (1994) p. 77.

- ^ Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar, § 328, line 8 Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ a b Gammeltoft 2006, p. 71.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 72.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 32.

- ^ a b Gillies (1906) p. 129. "Gometra, from N., is gottr + madr + ey."

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) pp. 58–59.

- ^ Watson (1926) p. 87.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 185.

- ^ a b Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 47.

- ^ Gammeltoft 2006, p. 74.

- ^ a b Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 84.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 69.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 109.

- ^ a b Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 70.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 83.

- ^ a b Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 65.

- ^ a b Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 132.

- ^ Gammeltoft 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 93.

- ^ a b Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 161.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 102.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 138.

- ^ a b Gammeltoft 2006, p. 77.

- ^ a b Gammeltoft 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 153.

- ^ a b Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 103.

- ^ a b c Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 104.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 63.

- ^ "Group 34: islands in the Irish Sea and the Western Isles 1" Archived 8 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine kmatthews.org.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ Munro, D. (1818) Description of the Western Isles of Scotland called Hybrides, by Mr. Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles, who travelled through most of them in the year 1549. Miscellanea Scotica, 2. Quoted in Murray (1966) p. 146.

- ^ a b Gammeltoft 2006, p. 72.

- ^ a b Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 195.

- ^ a b Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 102.

- ^ Buchanan (1983) Pages 2–6.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 314–25.

- ^ Newton, Michael Steven. The Naughty Little Book of Gaelic: All the Scottish Gaelic You Need to Curse, Swear, Drink, Smoke and Fool around. Sydney, Nova Scotia: Cape Breton UP, 2014.

- ^ Watson (1994) p. 97.

- ^ Maclean (1977) page 33.

- ^ Stevenson (1872) p. 10.

- ^ a b c Gammeltoft 2006, p. 76.

- ^ Buxton (1995) p. 33.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 87

- ^ Murray (1973) p. 41.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 94.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 101.

- ^ Buxton (1995) p. 158.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p 285.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 111.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 118.

- ^ Edwards, Kevin J. and Whittington, Graeme "Vegetation Change" in Edwards & Ralston (2003) p. 70.

- ^ Edwards, Kevin J., and Mithen, Steven (Feb. 1995) "The Colonization of the Hebridean Islands of Western Scotland: Evidence from the Palynological and Archaeological Records," Archived 22 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine World Archaeology. 26. No. 3. p. 348. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ Li, Martin (2005) Adventure Guide to Scotland Archived 22 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Hunter Publishing. p. 509.

- ^ "Mummification in Bronze Age Britain" BBC History. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "The Prehistoric Village at Cladh Hallan" Archived 25 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. University of Sheffield. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ^ See for example Haycock, David Boyd. "Much Greater, Than Commonly Imagined." Archived 26 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine The Newton Project. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ Moffat, Alistair (2005) Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London. Thames & Hudson. pp. 239–40.

- ^ Nieke, Margaret R. "Secular Society from the Iron Age to Dál Riata and the Kingdom of Scots" in Omand (2006) p. 60.

- ^ Lynch (2007) pp. 161 162.

- ^ Clancy, Thomas Owen "Church institutions: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- ^ a b Hunter (2000) pp. 44, 49.

- ^ Hunter (2000) p. 74.

- ^ Rotary Club (1995) p. 12.

- ^ Hunter (2000) p. 78.

- ^ a b Hunter (2000) p. 102.

- ^ a b Thompson (1968) p. 39.

- ^ "The Kingdom of Mann and the Isles" Archived 17 December 2012 at archive.today The Viking World. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Hunter (2000) pp. 109–111.

- ^ Thompson (1968) p. 37.

- ^ Rotary Club (1995) pp. 27, 30.

- ^ Gregory (1881) pp. 13–15, 20–21.

- ^ Downham (2007) pp. 174–75.

- ^ Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides: A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith et al (2007) p. 480.

- ^ Hunter (2000) pp. 127, 166.

- ^ Oram, Richard "The Lordship of the Isles: 1336–1545" in Omand (2006) pp. 135–38.

- ^ a b Rotary Club (1995) pp. 12–13.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 312.

- ^ Thompson (1968) pp. 41–42.

- ^ Murray (1977) p. 121.

- ^ "Dunvegan" Archived 4 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine castlescotland.net Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ "Incidents of the Jacobite Risings – Donald Livingstone" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine clanmclea.co.uk. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ "The Battle of Culloden" Archived 8 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine BBC. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ a b Hunter (2000) pp. 195–96, 204–06.

- ^ Hunter (2000) pp. 207–08.

- ^ Duncan, P. J. "The Industries of Argyll: Tradition and Improvement" in Omand (2006) pp. 152–53.

- ^ Hunter (2000) p. 212.

- ^ Hunter (2000) pp. 247, 262.

- ^ Duncan, P. J. "The Industries of Argyll: Tradition and Improvement" in Omand (2006) pp. 157–58.

- ^ Hunter (2000) p. 280.

- ^ Newton, Michael. "Highland Clearances Part 3". The Virtual Gael. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Hunter (2000) pp. 308–23.

- ^ Watson (1994) p. 65.

- ^ Armit, Ian "The Iron Age" in Omand (2006) p. 57.

- ^ a b c Woolf, Alex "The Age of the Sea-Kings: 900–1300" in Omand (2006) p. 95.

- ^ Brown, James (1892) "Place-names of Scotland" Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine p. 4 ebooksread.com. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ a b Duwe, Kurt C. (17 May 2005). "Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies". Linguae Celticae. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2004) "1901–2001 Gaelic in the Census" (PowerPoint) Linguae Celticae. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ "A' Cholaiste". UHI. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ Hunter (2000) p. 104.

- ^ Hunter (2000) p. 292.

- ^ Hunter (2000) p. 343.

- ^ Duncan, P. J. "The Industries of Argyll: Tradition and Improvement" in Omand (2006) p. 169.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 47, 87.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 57, 99.

- ^ "Blackhouses" Archived 19 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. isle-of-lewis.com Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ "Yard wins biggest wind tower job". BBC News. 10 December 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ^ McEwan-Fujita, Emily (2010), "Ideology, Affect, and Socialization in Language Shift and Revitalization: The Experiences of Adults Learning Gaelic in the Western Isles of Scotland", Language in Society, 39 (1): 27–64, doi:10.1017/S0047404509990649, JSTOR 20622703, S2CID 145694600

- ^ Charles Jedrej; Mark Nuttall (1996). White Settlers: Impact/Cultural. Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 9781134368501. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "How small-scale crofters in the Hebrides survive the challenges". 27 March 2020.

- ^ "Julie Fowlis". Thistle and Shamrock. NPR. 22 May 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Calum MacDonald at IMDb. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ "Donnie Munro: Biography" Archived 30 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine donniemunro.co.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ John Lorne Campbell, "Canna: The Story of a Hebridean Island," Oxford University Press, 1984, pages 104–105.

- ^ J. MacDonald, "Gaelic literature" in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 255–7.

- ^ School of Scottish Studies. (1967) University of Edinburgh. 11–12 p. 109.

- ^ "Làrach nam Bàrd". BBC Alba.

- ^ MacLean, Sorley (1954) Hallaig Archived 30 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Gairm magazine. Translation by Seamus Heaney (2002). Guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Angus Peter Campbell | Aonghas Phadraig Caimbeul – Fiosrachadh/Biog". Angus Peter Campbell. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Seachd: The Inaccessible Pinnacle (2007) at IMDb

- ^ "An Drochaid / The Bridge Rising". Media Co-op. January 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "An Drochaid". BBC Alba. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "How The Wicker Man changed the face of horror". The Independent. 15 September 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "The Wicker Man – The Various Versions of "The Wicker Man"". steve-p.org. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ I Know Where I'm Going! (1945) – IMDb, retrieved 18 February 2024

- ^ "Battlefield 2042 is getting overhauled for Season 6: Dark Creations". Sports Illustrated Video Games. 5 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "Famous Visitors to the Islands – Luchd-tadhail Ainmeil" Archived 17 October 2002 at the Wayback Machine Culture Hebrides. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ^ Thomson, Gordon (28 May 2009) "The house where Big Brother was born" Archived 31 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine New Statesman. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ Bold, Alan (29 December 1983) The Making of Orwell's 1984 Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Glasgow Herald.

- ^ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 130.

- ^ "Translations for Shepherd Moons" Archived 13 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. pathname.com. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "The various versions of The Wicker Man" Archived 12 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Steve Philips. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ The Decoy Bride at IMDb

- ^ Murray (1973) p. 72.

- ^ "Seabirds" Archived 3 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. National Trust for Scotland. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ Fraser Darling (1969) p. 79.

- ^ "Trotternish Wildlife" Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Duntulm Castle. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ Watson, Jeremy (12 October 2006). "Sea eagle spreads its wings...". Scotland on Sunday. Edinburgh.

- ^ Benvie (2004) p. 118.

- ^ "Protected mammals – Seals" Archived 20 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ Murray (1973) pp. 96–98.

- ^ Fraser Darling (1969) p. 286.

- ^ "Trout Fishing in Scotland: Skye" Archived 29 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine Trout & Salmon Fishing. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- ^ "Trends – The Sea" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ "Species List" Archived 2 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. www.whalewatchingtrips.co.uk. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Slack, Alf "Flora" in Slesser (1970) pp. 45–58.

- ^ "Loch Druidibeg National Nature Reserve: Where Opposites Meet". Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (pdf) SNH. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- ^ "South Uist and Eriskay attractions" Archived 14 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine isle-of-south-uist.co.uk. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "Higher plant species: 1833 Slender naiad" Archived 13 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine JNCC. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- ^ "Statutory Instrument 1994 No. 2716 " Archived 18 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "Campaign to stop the slaughter of over 5000 Hedgehogs on the Island of Uist". Epping Forest Hedgehog Rescue. Archived from the original on 27 August 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ Ross, John (21 February 2007). "Hedgehogs saved from the syringe as controversial Uist cull called off". The Scotsman. Edinburgh.

General references

[edit]- Ballin Smith, B. and Banks, I. (eds) (2002) In the Shadow of the Brochs, the Iron Age in Scotland. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2517-X

- Ballin Smith, Beverley; Taylor, Simon; and Williams, Gareth (2007) West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. Leiden. Brill.

- Benvie, Neil (2004) Scotland's Wildlife. London. Aurum Press. ISBN 1-85410-978-2

- Buchanan, Margaret (1983) St Kilda: a Photographic Album. W. Blackwood. ISBN 0-85158-162-5

- Buxton, Ben. (1995) Mingulay: An Island and Its People. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-874744-24-6

- Downham, Clare "England and the Irish-Sea Zone in the Eleventh Century" in Gillingham, John (ed) (2004) Anglo-Norman Studies XXVI: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 2003. Woodbridge. Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-072-8

- Fraser Darling, Frank; Boyd, J. Morton (1969). The Highlands and Islands. The New Naturalist. London: Collins. First published in 1947 under title: Natural history in the Highlands & Islands; by F. Fraser Darling. First published under the present title 1964.

- Gammeltoft, Peder (2006). "Scandinavian influence on Hebridean island names". In Gammeltoft, Peder; Jorgenson, Bent (eds.). Names through the Looking-Glass. Copenhagen: C.A. Reitzels Forlag. ISBN 8778764726.

- Gammeltoft, Peder (2010) "Shetland and Orkney Island-Names – A Dynamic Group Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine". Northern Lights, Northern Words. Selected Papers from the FRLSU Conference, Kirkwall 2009, edited by Robert McColl Millar.

- "Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands". (28 November 2003) General Register Office for Scotland. Edinburgh. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- Gillies, Hugh Cameron (1906) The Place Names of Argyll. London. David Nutt.

- Gregory, Donald (1881) The History of the Western Highlands and Isles of Scotland 1493–1625. Edinburgh. Birlinn. 2008 reprint – originally published by Thomas D. Morrison. ISBN 1-904607-57-8

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Hunter, James (2000) Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh. Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-376-4

- Keay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London. HarperCollins.

- Lynch, Michael (ed) (2007) Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923482-0.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Goireasan Cànain / Language Resources - Tadhail is Ionnsaich : Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 October 2025.

- Maclean, Charles (1977) Island on the Edge of the World: the Story of St. Kilda. Edinburgh. Canongate ISBN 0-903937-41-7

- Monro, Sir Donald (1549) A Description Of The Western Isles of Scotland. Appin Regiment/Appin Historical Society. Retrieved 3 March 2007. First published in 1774.

- Murray, W. H. (1966) The Hebrides. London. Heinemann.

- Murray, W.H. (1973) The Islands of Western Scotland. London. Eyre Methuen. ISBN 0-413-30380-2

- Omand, Donald (ed.) (2006) The Argyll Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-480-0

- Ordnance Survey (2009) "Get-a-map". Retrieved 1–15 August 2009.

- Rotary Club of Stornoway (1995) The Outer Hebrides Handbook and Guide. Machynlleth. Kittiwake. ISBN 0-9511003-5-1

- Slesser, Malcolm (1970) The Island of Skye. Edinburgh. Scottish Mountaineering Club.

- Steel, Tom (1988) The Life and Death of St. Kilda. London. Fontana. ISBN 0-00-637340-2

- Stevenson, Robert Louis (1995) The New Lighthouse on the Dhu Heartach Rock, Argyllshire. California. Silverado Museum. Based on an 1872 manuscript and edited by Swearingen, R.G.

- Thompson, Francis (1968) Harris and Lewis, Outer Hebrides. Newton Abbot. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4260-6

- Watson, W. J. (1994) The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-323-5. First published 1926.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1234-5.

External links

[edit]- Map sources for Hebrides

57°00′N 07°00′W / 57.000°N 7.000°W

- Hebrides/Western Isles Guide

- National Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE Archived 3 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine (selection of archive films about the Hebrides)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

Hebrides

View on GrokipediaPhysical Environment

Geology and Geography

The Hebrides constitute an archipelago situated off the northwestern coast of Scotland, subdivided into the Inner Hebrides—positioned between the mainland and the Minch strait—and the Outer Hebrides, which lie farther west in the Atlantic Ocean. The Outer Hebrides form a near-continuous chain of islands extending approximately 210 kilometers from the Butt of Lewis in the north to Barra Head in the south, characterized by intricate coastlines exceeding 3,000 kilometers in length and encompassing an area of about 3,000 square kilometers. These islands feature undulating terrain with moorlands, machair plains, and rugged hills, shaped by glacial erosion during the Quaternary period.[7][8] Geologically, the Outer Hebrides are predominantly underlain by Lewisian gneiss, Precambrian metamorphic rocks representing some of the oldest exposed formations in Europe, with ages exceeding 1.7 billion years. This ancient basement forms a stable horst block between the Minch fault zone and the Atlantic margin, minimally affected by subsequent tectonic events. In contrast, the Inner Hebrides display a more complex stratigraphy, including Mesozoic sediments intruded and overlain by Paleogene igneous rocks from the British Tertiary Igneous Province, linked to early rifting of the North Atlantic around 60 million years ago. Volcanic fissures and flood basalts contributed to the uplift and formation of islands like Skye and Mull, producing features such as the hexagonal basalt columns of Staffa.[8][9][10] Prominent topographic features include the Cuillin ridge on Skye, with peaks rising to over 900 meters, and Clisham, the highest summit in the Outer Hebrides at 799 meters on Harris. Coastal processes have carved sea stacks, arches, and caves, while post-glacial rebound and periglacial activity have influenced valley forms and boulder fields, particularly in elevated areas of Lewis. The region's stability is underscored by recent British Geological Survey assessments indicating low seismic risk and minimal ground instability.[11][12][13]Climate and Weather Patterns

The Hebrides possess a temperate oceanic climate, moderated by the North Atlantic Drift, resulting in mild winters with rare frosts and cool summers, alongside consistently high precipitation and prevailing westerly winds that often reach gale force, particularly during autumn and winter.[14][15] Annual average temperatures range from 8°C to 9°C across the islands, with the coldest months (January and February) recording means of 5°C to 6°C and the warmest (July and August) reaching 13°C to 15°C; diurnal highs in summer typically peak at 16°C in representative stations like Stornoway on Lewis.[16][14][17] Precipitation is abundant and evenly distributed, averaging 1,150 mm to 1,300 mm annually, with December as the wettest month (up to 150 mm) featuring around 25 rainy days, while May is driest with about 17; overcast conditions dominate, with sunshine hours totaling 1,100 to 1,200 per year, concentrated in the southern Outer Hebrides.[16][17][18] Wind speeds frequently exceed 20 knots, escalating to storm force (over 50 knots) in winter due to frequent Atlantic depressions, rendering the Outer Hebrides more exposed and gusty than the somewhat sheltered Inner Hebrides.[15][14] These patterns stem from the islands' position in the path of mid-latitude cyclones, yielding over 200 rainy days yearly and limiting extreme temperature swings, though recent decades show slight warming trends with increased winter wetness.[19][20]Etymology and Nomenclature

Linguistic Origins

The English name "Hebrides" derives from the Latin "Hebudes" or "Hæbudes," first attested in Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia (c. 77 AD), where he describes a cluster of about 30 islands lying off the northwestern coast of Britain, inhabited by primitive peoples who subsisted on fish and lacked knowledge of agriculture.[21] This form appears to stem from earlier Greek renderings, such as Ptolemy's "Eboudai" or "Hebouda i" in his Geographia (c. 150 AD), which maps five principal islands in the vicinity of ancient Caledonia.[22] The precise linguistic root remains uncertain, with scholars proposing a pre-Celtic substrate origin, potentially from a Pictish or indigenous Brittonic language predating Roman contact; alternative hypotheses link it to phonetic adaptations of tribal names like the "Epidii," a group documented in Argyll, though evidence for direct equivalence is lacking.[23] Medieval evolution of the term involved scribal variations, with "Hebudes" transitioning to "Hebrides" likely through manuscript errors substituting "ri" for "u," as seen in later Latin texts by authors like Solinus and Pomponius Mela.[24] Concurrently, Norse settlers from the 8th to 13th centuries designated the archipelago Suðreyjar ("Southern Isles") in Old Norse, distinguishing it from the Norðreyjar (Orkney Islands) to the north; this toponym reflected geographic orientation rather than linguistic descent from classical forms and persisted in ecclesiastical contexts, such as the Bishopric of the Sudreys until its dissolution in 1472.[25] In Scottish Gaelic, the islands lack a direct calque of "Hebrides," instead employing descriptive phrases like Innse Gall ("Islands of the Strangers"), alluding to Norse overlordship, or modern administrative terms such as Na h-Eileanan Siar ("the Western Isles") for the Outer Hebrides council area established in 1975.[23] The classical-derived "Hebrides" gained prominence in English cartography and literature from the Renaissance, notably in Timothy Pont's maps (c. 1590s) and Martin Martin's A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland (1703), supplanting Norse-influenced alternatives like "Sorows" or "Sowris."[26]Divisions: Inner and Outer Hebrides

The Hebrides are geographically divided into the Inner Hebrides, situated closer to the Scottish mainland, and the Outer Hebrides, positioned farther westward and more remote.[4][27] This distinction arises from their relative proximity, with the Inner group lying east of major sea channels like the Little Minch and the Sea of the Hebrides, which separate them from the Outer chain.[4] The Inner Hebrides encompass approximately 35 inhabited islands and numerous uninhabited ones, scattered along the western Scottish coast over a distance of about 150 miles.[28] Principal islands include Skye, the largest at 1,656 square kilometers; Mull; Islay; Jura; Coll; Tiree; and the Small Isles (Eigg, Rum, Muck, and Canna).[29][30] These islands are administratively divided among Highland, Argyll and Bute, and Argyll councils, reflecting their fragmented distribution.[29] In contrast, the Outer Hebrides consist of a more linear archipelago of over 100 islands and skerries, with 15 inhabited, stretching 130 miles from Lewis in the north to Barra in the south.[31] Key islands are Lewis and Harris, which together form the largest landmass at 2,179 square kilometers and are geologically one island; North Uist; Benbecula; South Uist; and Barra.[2][32] Many southern islands in this group are linked by causeways, facilitating connectivity, and the entire chain falls under the unitary authority of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar.[32] This administrative unity contrasts with the Inner Hebrides' dispersal, underscoring the Outer group's cohesive geographical alignment parallel to the mainland's western edge.[31]Pre-Modern History

Prehistoric and Early Settlements

The earliest archaeological evidence of human occupation in the Hebrides dates to the Mesolithic period, with microlithic tools and activity layers uncovered at Northton on Harris in the Outer Hebrides, radiocarbon dated to approximately 7050–6700 cal BC.[33] These findings indicate small-scale hunter-gatherer groups exploiting coastal resources, consistent with broader western Scottish Mesolithic patterns.[34] Late Mesolithic shell middens on Oronsay in the Inner Hebrides further attest to sustained maritime subsistence strategies into around 4000 BC.[34] Neolithic settlers arrived around 4000 BC, introducing agriculture, domesticated animals, and monumental architecture.[35] Prominent sites include the Callanish Stones on Lewis, where the primary stone circle and central monolith were erected circa 2900 BC, forming part of a larger complex used for ritual purposes.[36] Chambered cairns, such as Barpa Langais on North Uist, represent communal burial practices typical of Neolithic farming communities across the islands.[37] Bronze Age activity is evidenced by roundhouse settlements like Cladh Hallan on South Uist, featuring preserved structures and mummified remains from around 1600–1100 BC, highlighting continuity in domestic organization amid metalworking advancements.[38] Iron Age developments saw the construction of defensive structures, including brochs—tall, dry-stone towers—beginning circa 400 BC, with examples like Dun Carloway on Lewis exemplifying elite residences or fortifications occupied into the early centuries AD.[39] Duns, promontory forts, and later wheelhouses indicate evolving settlement patterns focused on fortified coastal sites, reflecting social complexity prior to broader Celtic influences.[35]Celtic and Norse Influences

The Hebrides were initially shaped by Celtic Gaels who migrated from Ireland, establishing a Gaelic-speaking society influenced by the kingdom of Dál Riata. Christianity reached the islands through Irish missionaries, with St. Columba founding a monastery on Iona in 563 AD, which served as a key center for evangelizing the region and mainland Scotland.[40] This Celtic Christian tradition emphasized monastic communities and integrated with pre-existing Gaelic customs, fostering a culture of oral literature, kinship-based clans, and early stone crosses that reflected Insular artistic styles. Norse influence began with Viking raids in the late 8th century, targeting monastic sites like Iona, which suffered attacks in 795, 802, and 825 AD. Settlement followed in the mid-9th century, led by figures such as Ketill Flatnose, a Norwegian chieftain who established control over the Hebrides around 850 AD, displacing or assimilating local Picts and Gaels.[41] Ketill's rule marked the integration of Norse governance, with Scandinavian settlers introducing longhouse architecture, pagan burial practices initially, and a seafaring economy focused on raiding and trade. By the 10th century, a hybrid Norse-Gaelic elite emerged, known as the Gall-Gaedhil or "foreign Gaels," who blended Norse military prowess with Gaelic social structures in the Kingdom of the Isles (Suðreyjar), encompassing the Hebrides and Isle of Man.[42] This kingdom, often under nominal Norwegian suzerainty, featured rulers like the Uí Ímair dynasty who adopted Christianity while retaining Norse legal assemblies (things) and ship-based warfare; place names such as Barra (from Norse Barrey) and Lewis (from Ljǫðhus) persist as linguistic evidence of this era. The Gall-Gaedhil facilitated cultural exchange, evident in hybrid artifacts like the Manx cross slabs combining Celtic knotwork with Norse runes. Norse dominance waned after Scottish incursions, culminating in the Battle of Largs in 1263 and the Treaty of Perth in 1266, by which King Magnus VI of Norway ceded the Hebrides to Scotland for 4,000 merks, ending formal Scandinavian rule.[43] Despite this, Norse genetic and toponymic legacies endured, contributing to a bilingual Norse-Gaelic society that transitioned under Scottish overlordship, with Gaelic reasserting cultural primacy by the 15th century.Transition to Scottish Dominion

Norwegian suzerainty over the Hebrides, exercised through the Kingdom of the Isles (Suðreyjar), persisted from the late 11th century until the mid-13th century, with local control often held by Gaelic-Norse chieftains such as those descended from Somerled.[44] Scottish monarchs, seeking to consolidate western territories, began challenging this arrangement under Alexander II, who in 1248 demanded the submission of Hebridean lords and attempted to purchase the islands from Norway, offers rejected by Haakon IV.[44] Tensions escalated in 1262 when Scottish forces under Dubhghall mac Ruaidhrí and Aonghas Mór mac Domhnaill seized Norse-held territories in Skye and Kintyre, prompting Haakon IV to assemble a fleet of over 100 ships and sail west to reassert control.[44] [45] The decisive confrontation occurred at the Battle of Largs on October 2, 1263, where a Norwegian detachment from Haakon's storm-battered fleet clashed with Scottish levies led by Alexander Stewarts; adverse weather had already dispersed much of the Norse armada, contributing to their tactical disadvantage despite initial successes.[46] [44] Haakon IV withdrew to Orkney, where he died on December 12, 1263, leaving his son Magnus VI to inherit a weakened position amid ongoing Scottish gains in the Hebrides.[44] Negotiations ensued, culminating in the Treaty of Perth on July 2, 1266, whereby Magnus ceded the Hebrides and Isle of Man to Alexander III for a lump sum of 4,000 merks (equivalent to 100,000 silver pennies) and an initial annual pension of 100 merks, which Scotland ceased paying after 1269.[47] [45] The treaty formalized Scottish dominion but allowed Hebridean inhabitants the option to relocate to Norway, though few exercised this right, reflecting entrenched local ties.[45] Post-1266, the islands integrated into the Scottish realm, with crown authority delegated to powerful clans like the MacDonalds, who retained de facto control as Lords of the Isles until the late 15th century, marking a gradual shift from Norse overlordship to Gaelic-Scottish feudal structures.[48] Norwegian influence waned rapidly, evidenced by the non-renewal of tribute and the absence of further military reclamation attempts.[46]Modern History and Social Changes

Highland Clearances: Causes and Consequences

The Highland Clearances in the Hebrides encompassed the systematic eviction of tenants from communal lands, primarily in the western islands such as Skye, Lewis, Harris, and the Small Isles, to facilitate agricultural reorganization and commercial exploitation between approximately 1760 and 1860.[49] This process accelerated after the 1820s, driven by the collapse of temporary economic booms and the need for larger-scale farming units amid rising population pressures.[49] In the Outer Hebrides, for instance, clearances targeted interior glens and coastal townships, converting them from subsistence crofting and cattle rearing to sheep pastures or deer forests.[50] Key causes stemmed from the transition of clan chiefs into profit-oriented landlords following the 1746 Battle of Culloden, which dismantled the traditional tacksman system and exposed Highland economies to market forces.[49] Population growth in the Hebrides, averaging 1.46% annually from 1811 to 1820, exceeded land productivity, leading to subdivision of holdings and subsistence crises, such as those in 1816–1817 and 1837–1838.[49] The introduction of Cheviot sheep farming proved highly lucrative, with sheep numbers in comparable Highland regions surging from 50,000 in Inverness-shire in 1800 to 700,000 by 1880, necessitating the consolidation of fragmented tenancies into expansive grazings that displaced smallholders.[49] Additionally, the kelp industry, which employed 25,000–30,000 in the western islands by 1815 for alkali production during the Napoleonic Wars, collapsed post-1815 due to cheaper industrial alternatives, rendering coastal populations economically redundant and prompting further evictions.[49] In Lewis's Uig parish, clearances from 1804 onward, including sites like Scaliscro in 1804 and Valtos in 1848–1851, explicitly prioritized sheep runs over tenant grazing rights.[50] The consequences included widespread displacement, with estimates of tens of thousands evicted across the Highlands and Islands over the period, though precise Hebridean figures vary; for example, around 700 people from about 50 families were removed from South Harris in 1839, and approximately 500 from Lewis emigrated forcibly in 1851.[51][50] Emigration surged, particularly to Canada’s Eastern Townships and Quebec, where Lewis evacuees from townships like Mealista (1838) and Gisla settled, though high mortality followed—up to 250 of the 1851 Lewis contingent died from smallpox and cholera within months of arrival.[50] Depopulation accelerated during the 1846–1856 potato famine, with landlords in the Hebrides funding passages for over 16,000 across affected regions, resulting in abandoned townships and a shift to coastal crofting clusters.[49] Long-term effects encompassed enduring rural underdevelopment, cultural disruption through Gaelic community fragmentation, and the eventual statutory recognition of crofters' rights in the 1886 Crofters Holdings Act, which stabilized remnants of the tenant system but did not reverse prior losses.[52][49]Industrialization, Depopulation, and Emigration

The Hebrides experienced limited industrialization, primarily through extractive and seasonal industries rather than large-scale manufacturing. The kelp industry, involving the harvesting and burning of seaweed for soda ash used in glass and soap production, expanded during the Napoleonic Wars due to import restrictions, generating up to £70,000 annually in the Hebrides by the early 19th century.[53] However, it collapsed after 1815 with the end of hostilities and competition from cheaper Leblanc process imports, leading to widespread economic distress and contributing to the Highland Clearances as landlords sought alternative revenues from sheep farming.[54] [55] Fishing, particularly herring, provided a temporary boom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with Stornoway in Lewis becoming a key port during the "Herring Age." At its 1907 peak, Scotland's herring industry cured and exported 2.5 million barrels (227,000 tonnes), with Hebridean communities, including up to 3,000 local women known as "Herring Girls," processing catches for export to Germany and Eastern Europe.[56] [57] This influx supported population stability briefly but declined sharply from the 1930s due to overfishing, stock depletion, and shifting markets, exacerbating economic vulnerability in crofting-dependent islands.[58] Cottage industries like Harris Tweed weaving offered some diversification in the Outer Hebrides, handwoven from local wool since the 19th century and employing up to 50% of the workforce at its mid-20th-century peak, with production regulated under the Harris Tweed Act of 1993 to ensure island origin.[59] Small-scale quarrying, such as slate on Seil in the Inner Hebrides, peaked in the 19th century but closures like Easdale's in the 1880s led to local depopulation.[60] These efforts failed to foster sustained manufacturing due to geographic isolation, poor infrastructure, and reliance on volatile global commodities, leaving the economy agrarian and susceptible to busts. Depopulation accelerated post-Clearances, driven by economic stagnation and limited opportunities. Scotland's islands, including the Hebrides, saw over half of 233 inhabited islands lose all residents between 1861 and 2011, with the Outer Hebrides recording a population of 26,830 in 2018, down 3.1% from 2011 and reflecting long-term decline from 19th-century peaks exceeding 29,000 on Lewis alone.[61] [62] [63] Factors included harsh terrain limiting arable land, subdivision of crofts fostering overpopulation, and collapse of kelp and herring sectors, prompting out-migration to urban Lowlands or overseas.[64] Emigration waves from the Hebrides spanned the 19th and 20th centuries, with approximately 70,000 Highlanders and islanders departing for Canada, Australia, and North America amid post-Napoleonic hardships and interwar depressions.[54] Specific outflows, such as from Uig in 1855, were documented in contemporary reports, often facilitated by landlords easing restrictions after kelp's failure to sustain rents.[65] [53] Twentieth-century emigration continued post-World Wars and during the 1930s slump, targeting industrial centers and colonies, reducing island densities to 9 persons per square kilometer by 2018—far below Scottish averages—and threatening community viability and Gaelic culture.[66] [62] This pattern underscores causal links between failed industrialization, subsistence pressures, and demographic exodus, with remittances and return migration offering partial mitigation but insufficient to reverse trends.[64]20th-Century Developments and Post-War Recovery