Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

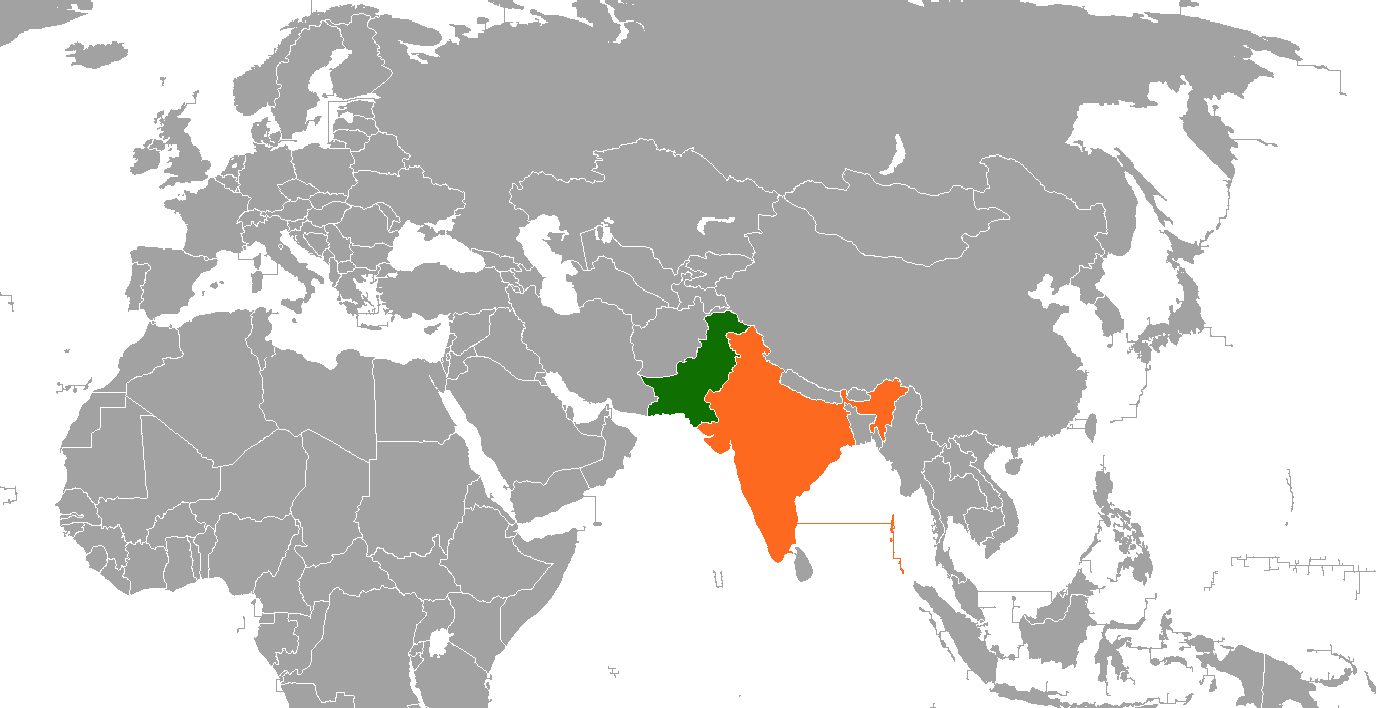

India–Pakistan relations

View on Wikipedia

| |

Pakistan |

India |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| High Commission of Pakistan, New Delhi | High Commission of India, Islamabad |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Saad Ahmad Warraich | Ambassador Geetika Srivastava |

India and Pakistan have a complex and largely hostile relationship that is rooted in a multitude of historical and political events, most notably the partition of British India in August 1947.

Two years after World War II, the United Kingdom formally dissolved British India, dividing it into two new sovereign nations: the Union of India and Pakistan. The partitioning of the former British colony resulted in the displacement of up to 15 million people, with the death toll estimated to have reached between several hundred thousand and one million people as Hindus and Muslims migrated in opposite directions across the Radcliffe Line to reach India and Pakistan, respectively.[1] In 1950, India emerged as a secular republic with a Hindu-majority population. Shortly afterwards, in 1956, Pakistan emerged as an Islamic republic with a Muslim-majority population.

While the two South Asian countries established full diplomatic ties shortly after their formal independence, their relationship was quickly overshadowed by the mutual effects of the partition as well as by the emergence of conflicting territorial claims over various princely states, with the most significant dispute being that of Jammu and Kashmir. Since 1947, India and Pakistan have fought three major wars and one undeclared war, and have also engaged in numerous armed skirmishes and military standoffs; the Kashmir conflict has served as the catalyst for every war between the two states, with the exception of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, which instead occurred alongside the Bangladesh Liberation War, which saw the secession of East Pakistan as the independent country of Bangladesh. It resulted in a large displacement of Pakistan's Hindu minority.[2][3]

The India–Pakistan border is one of the most militarized international boundaries in the world. There have been numerous attempts to improve the relationship, notably with the 1972 Shimla summit, 1999 Lahore summit, and the 2001 Agra summit in addition to various peace and co-operation initiatives. Despite those efforts, relations between the countries have remained frigid as a result of repeated acts of cross-border terrorism sponsored by the Pakistani side and alleged subversive acts sponsored by India.[4] The lack of any political advantages on either side for pursuing better relations has resulted in a period of "minimalist engagement" by both countries. This allows them to keep a "cold peace" with each other.[5]

Northern India and most of modern-day eastern Pakistan overlap with each other in terms of their common Indo-Aryan demographic, natively speaking a variety of Indo-Aryan languages (mainly Punjabi, Sindhi, and Hindi–Urdu). Although the two countries have linguistic and cultural ties, the size of India–Pakistan trade is very small relative to the size of their economies and the fact that they share a land border.[6] Trade across direct routes has been curtailed formally,[7] so the bulk of India–Pakistan trade is routed through Dubai in the Middle East.[8] According to a BBC World Service poll in 2017, only 5% of Indians view Pakistan's influence positively, with 85% expressing a negative view, while 11% of Pakistanis view India's influence positively, with 62% expressing a negative view.[9]

Background

[edit]Pre-partition era

[edit]

Most of the pre-British invasions into India (the Muslim conquests having been the most impactful) took place from the northwest through the modern-day territory of Pakistan. This geography meant that Pakistan absorbed more Persian and Muslim influences than the rest of the subcontinent, which can be seen in its usage of a modified Perso-Arabic alphabet for writing its native languages.[10]

In the 1840s, Sindh, Kashmir, and Punjab, which are along today's India–Pakistan border, were annexed into British India. British historian John Keay notes that while the rest of British India had generally been consolidated through treaties and more nonviolent means, much of what is now Pakistan had to be physically conquered.[11] By the early 20th century, the Pakistan Movement had emerged, demanding a separate nation for Indian Muslims carved out of the northwestern and northeastern regions.[12]

Seeds of conflict during independence

[edit]

Massive population exchanges occurred between the two newly formed states in the months immediately following the partition. There was no conception that population transfers would be necessary because of the partitioning. Religious minorities were expected to stay put in the states they found themselves residing in. However, while an exception was made for Punjab, where the transfer of populations was organised because of the communal violence affecting the province, this did not apply to other provinces.[13][14]

The partition of British India split the former British province of Punjab and Bengal between the Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. The mostly Muslim western part of the province became Pakistan's Punjab province; the mostly Hindu and Sikh eastern part became India's East Punjab state (later divided into the new states of Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh). Many Hindus and Sikhs lived in the west, and many Muslims lived in the east, and the fears of all such minorities were so great that the Partition saw many people displaced and much inter-communal violence. Some have described the violence in Punjab as a retributive genocide.[15] Total migration across Punjab during the partition is estimated at 12 million people;[16] around 6.5 million Muslims moved from East Punjab to West Punjab, and 4.7 million Hindus and Sikhs moved from West Punjab to East Punjab.

According to the British plan for the partition of British India, all the 680 princely states were allowed to decide which of the two countries to join. With the exception of a few, most of the Muslim-majority princely-states acceded to Pakistan while most of the Hindu-majority princely states joined India. However, the decisions of some of the princely states would shape the Pakistan–India relationship considerably in the years to come.

Junagadh issue

[edit]

Junagadh was a state on the south-western end of Gujarat, with the principalities of Manavadar, Mangrol and Babriawad. It was not contiguous to Pakistan and other states physically separated it from Pakistan. The state had an overwhelming Hindu population which constituted more than 80% of its citizens, while its ruler, Nawab Mahabat Khan, was a Muslim. Mahabat Khan acceded to Pakistan on 15 August 1947. Pakistan confirmed the acceptance of the accession on 15 September 1947.

India did not accept the accession as legitimate. The Indian point of view was that Junagadh was not contiguous to Pakistan, that the Hindu majority of Junagadh wanted it to be a part of India, and that the state was surrounded by Indian territory on three sides.

The Pakistani point of view was that since Junagadh had a ruler and governing body who chose to accede to Pakistan, it should be allowed to do so. Also, because Junagadh had a coastline, it could have maintained maritime links with Pakistan even as an enclave within India.

Neither of the states was able to resolve this issue amicably and it only added fuel to an already charged environment. Sardar Patel, India's Home Minister, felt that if Junagadh was permitted to go to Pakistan, it would create communal unrest across Gujarat. The government of India gave Pakistan time to void the accession and hold a plebiscite in Junagadh to pre-empt any violence in Gujarat. Samaldas Gandhi formed a government-in-exile, the Arzi Hukumat (in Urdu: Arzi: Transitional, Hukumat: Government) of the people of Junagadh. Patel ordered the annexation of Junagadh's three principalities.

India cut off supplies of fuel and coal to Junagadh, severed air and postal links, sent troops to the frontier, and occupied the principalities of Mangrol and Babariawad that had acceded to India.[17] On 26 October, Nawab of Junagadh and his family fled to Pakistan following clashes with Indian troops. On 7 November, Junagadh's court, facing collapse, invited the Government of India to take over the State's administration. The Dewan of Junagadh, Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, the father of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, decided to invite the Government of India to intervene and wrote a letter to Mr. Buch, the Regional Commissioner of Saurashtra in the Government of India to this effect.[18] The Government of Pakistan protested. The Government of India rejected the protests of Pakistan and accepted the invitation of the Dewan to intervene.[19] Indian troops occupied Junagadh on 9 November 1947. In February 1948, a plebiscite held almost unanimously voted for accession to India.

Kashmir conflict

[edit]

Kashmir was a Muslim-majority princely state, ruled by a Hindu king, Maharaja Hari Singh. At the time of the partition of India, Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of the state, preferred to remain independent and did not want to join either the Dominion of India or the Dominion of Pakistan.

Despite the standstill agreement with Pakistan, teams of Pakistani forces were dispatched into Kashmir. Backed by Pakistani paramilitary forces, Pashtun Mehsud tribals[20] invaded Kashmir in October 1947 under the code name "Operation Gulmarg" to seize Kashmir. The Maharaja requested military assistance from India. The Governor General of India, Lord Mountbatten, required the Maharaja to accede to India before India could send troops. Accordingly, the instrument of accession was signed and accepted during 26–27 October 1947. The accession as well as India's military assistance were supported by Sheikh Abdullah, the state's political leader heading the National Conference party, and Abdullah was appointed as the Head of Emergency Administration of the state the following week.

Pakistan refused to accept the state's accession to India and escalated the conflict, by giving full-fledged support to the rebels and invading tribes. A constant replenishment of Pashtun tribes were organised, and provided arms and ammunition as well as military leadership.

Indian troops managed to evict the invading tribes from the Kashmir Valley but the onset of winter made much of the state impassable. In December 1947, India referred the conflict to the United Nations Security Council, requesting it to prevent the outbreak of a general war between the two fledgling nations. The Security Council passed Resolution 47, asking Pakistan to withdraw all its nationals from Kashmir, asking India to withdraw the bulk of its forces as a second step, and offering to conduct a plebiscite to determine the people's wishes. Though India rejected the resolution, it accepted a suitably amended version of it negotiated by the UN Commission set up for the purpose, as did Pakistan towards the end of 1948. A ceasefire was declared on 1 January the following year.

However, India and Pakistan could not agree on the suitable steps for demilitarisation to occur as prelude to the plebiscite. Pakistan organised the rebel fighting forces of Azad Kashmir into a full-fledged military of 32 battalions, and India insisted that it should be disbanded as part of the demilitarisation. No agreement was reached and the plebiscite never took place.

Wars, conflicts, and disputes

[edit]India and Pakistan have fought in numerous armed conflicts since their independence. There are three major wars that have taken place between the two states, namely in 1947, 1965 and the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. In addition to this was the unofficial Kargil War in 1999 and some border skirmishes.[21] While both nations have held a shaky cease-fire agreement since 2003, they continue to trade fire across the disputed area. Both nations blame the other for breaking the cease-fire agreement, claiming that they are firing in retaliation for attacks.[22] On both sides of the disputed border, an increase in territorial skirmishes that started in late 2016 and escalated into 2018 killed hundreds of civilians and made thousand homeless.[21][22]

War of 1965

[edit]The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 started following the culmination of skirmishes that took place between April 1965 and September 1965 and Pakistan's Operation Gibraltar, which was designed to infiltrate forces into Jammu and Kashmir to precipitate an insurgency against rule by India.[23] India retaliated by launching a full-scale military attack on West Pakistan. The seventeen-day war caused thousands of casualties on both sides and witnessed the largest engagement of armored vehicles and the largest tank battle since World War II.[24][25] Hostilities between the two countries ended after a United Nations-mandated ceasefire was declared following diplomatic intervention by the Soviet Union and the United States, and the subsequent issuance of the Tashkent Declaration.[26] The five-week war caused thousands of casualties on both sides. Most of the battles were fought by opposing infantry and armoured units, with substantial backing from air forces, and naval operations. It ended in a United Nations (UN) mandated ceasefire and the subsequent issuance of the Tashkent Declaration.

War of 1971

[edit]

Pakistan, since independence, was geo-politically divided into two major regions, West Pakistan and East Pakistan. East Pakistan was occupied mostly by Bengali people. After a Pakistani military operation and a genocide on Bengalis in December 1971, following a political crisis in East Pakistan, the situation soon spiralled out of control in East Pakistan and India intervened in favour of the rebelling Bengali populace. The conflict, a brief but bloody war, resulted in the independence of East Pakistan. In the war, the Indian Army invaded East Pakistan from three sides, while the Indian Navy used the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant to impose a naval blockade of East Pakistan. The war saw the first offensive operations undertaken by the Indian Navy against an enemy port, when Karachi harbour was attacked twice during Operation Trident (1971) and Operation Python. These attacks destroyed a significant portion of Pakistan's naval strength, whereas no Indian ship was lost. The Indian Navy did, however, lose a single ship, when INS Khukri (F149) was torpedoed by a Pakistani submarine. 13 days after the invasion of East Pakistan, 93,000 Pakistani military personnel surrendered to the Indian Army and the Mukti Bahini. After the surrender of Pakistani forces, East Pakistan became the independent nation of Bangladesh.

1999 Kargil War

[edit]

In May 1999 some Kashmiri shepherds discovered the presence of militants and non-uniformed Pakistani soldiers (many with official identifications and Pakistan Army's custom weaponry) in the Kashmir Valley, where they had taken control of border hilltops and unmanned border posts. The incursion was centred around the town of Kargil, but also included the Batalik and Akhnoor sectors and artillery exchanges at the Siachen Glacier.[27][28]

The Indian army responded with Operation Vijay, which launched on 26 May 1999. This saw the Indian military fighting thousands of militants and soldiers in the midst of heavy artillery shelling and while facing extremely cold weather, snow and treacherous terrain at the high altitude.[29] Over 500 Indian soldiers were killed in the three-month-long Kargil War, and it is estimated around 600–4,000 Pakistani militants and soldiers died as well.[30][31][32][33] India pushed back the Pakistani militants and Northern Light Infantry soldiers. Almost 70% of the territory was recaptured by India.[29] Vajpayee sent a "secret letter" to U.S. President Bill Clinton that if Pakistani infiltrators did not withdraw from the Indian territory, "we will get them out, one way or the other".[34]

After Pakistan suffered heavy losses, and with both the United States and China refusing to condone the incursion or threaten India to stop its military operations, General Pervez Musharraf was recalcitrant and Nawaz Sharif asked the remaining militants to stop and withdraw to positions along the LoC.[35] The militants were not willing to accept orders from Sharif but the NLI soldiers withdrew.[35] The militants were killed by the Indian army or forced to withdraw in skirmishes which continued even after the announcement of withdrawal by Pakistan.[35]

A subsequent military coup in Pakistan that overturned the democratically elected Nawaz Sharif government in October of the same year also proved a setback to relations.

Water disputes

[edit]The Indus Waters Treaty governs the rivers that flow from India into Pakistan. Water is cited as one possible cause for a conflict between the two nations, but to date issues such as the Nimoo Bazgo Project have been resolved through diplomacy.[36]

Bengal refugee crisis (1949)

[edit]In 1949, India recorded close to 1 million Hindu refugees, who flooded into West Bengal and other states from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), owing to communal violence, intimidation and repression from authorities. The plight of the refugees outraged Hindus and Indian nationalists, and the refugee population drained the resources of Indian states, which were unable to absorb them. While not ruling out war, Prime Minister Nehru and Sardar Patel invited Liaquat Ali Khan for talks in Delhi. Although many Indians termed this appeasement, Nehru signed a pact with Liaquat Ali Khan that pledged both nations to the protection of minorities and creation of minority commissions. Khan and Nehru also signed a trade agreement, and committed to resolving bilateral conflicts through peaceful means. Steadily, hundreds of thousands of Hindus returned to East Pakistan, but the thaw in relations did not last long, primarily owing to the Kashmir conflict.

Insurgency in Kashmir (1989–present)

[edit]

According to some reports published by the Council of Foreign Relations, the Pakistan military and the ISI have provided covert support to terrorist groups active in Kashmir, including the al-Qaeda affiliate Jaish-e-Mohammed.[37][38] Pakistan has denied any involvement in terrorist activities in Kashmir, arguing that it only provides political and moral support to the secessionist groups who wish to escape Indian rule. Many Kashmiri militant groups also maintain their headquarters in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, which is cited as further proof by the Indian government.

Journalist Stephen Suleyman Schwartz notes that several militant and criminal groups are "backed by senior officers in the Pakistani army, the country's ISI intelligence establishment and other armed bodies of the state."[39]

Insurgent attacks

[edit]- Insurgents attack on Jammu and Kashmir State Assembly: A car bomb exploded near the Jammu and Kashmir State Assembly on 1 October 2001, killing 27 people on an attack that was blamed on Kashmiri separatists. It was one of the most prominent attacks against India apart from on the Indian Parliament in December 2001. The dead bodies of the terrorists and the data recovered from them revealed that Pakistan was solely responsible for the activity.[40]

- Qasim Nagar Attack: On 13 July 2003, armed men believed to be a part of the Lashkar-e-Toiba threw hand grenades at the Qasim Nagar market in Srinagar and then fired on civilians standing nearby killing twenty-seven and injuring many more.[41][42][43][44][45]

- Assassination of Abdul Ghani Lone: Abdul Ghani Lone, a prominent All Party Hurriyat Conference leader, was assassinated by an unidentified gunmen during a memorial rally in Srinagar. The assassination resulted in wide-scale demonstrations against the Indian occupied-forces for failing to provide enough security cover for Mr. Lone.[1]

- 20 July 2005 Srinagar Bombing: A car bomb exploded near an armoured Indian Army vehicle in the Church Lane area in Srinagar killing four Indian Army personnel, one civilian and the suicide bomber. Terrorist group Hizbul Mujahideen, claimed responsibility for the attack.[2]

- Budshah Chowk attack: A terrorist attack on 29 July 2005 at Srinigar's city centre, Budshah Chowk, killed two and left more than 17 people injured. Most of those injured were media journalists.[3]

- Murder of Ghulam Nabi Lone: On 18 October 2005, a suspected man killed Jammu and Kashmir's then education minister Ghulam Nabi Lone. No Terrorist group claimed responsibility for the attack.[4]

- 2016 Uri attack: A terrorist attack by four heavily armed terrorists on 18 September 2016, near the town of Uri in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, killed 18 and left more than 20 people injured. It was reported as "the deadliest attack on security forces in Kashmir in two decades".[46]

- 2019 Pulwama attack: On 14 February 2019, a convoy of vehicles carrying security personnel on the Jammu Srinagar National Highway was attacked by a vehicle-bound suicide bomber in Lethpora near Awantipora, Pulwama district, Jammu and Kashmir, India. The attack resulted in the death of 38 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel and the attacker. The responsibility of the attack was claimed by the Pakistan-based Islamist militant group Jaish-e-Mohammed.[47]

- 2025 Pahalgam attack: On 22 April 2025, 26 tourists were attacked by terrorists, resulting in the death of 28 people, including a local from Jammu and Kashmir and two foreigners from Nepal and the UAE. India stopped supplying the Indus river to Pakistan.

Insurgent activities elsewhere

[edit]The attack on the Indian Parliament was by far the most dramatic attack carried out allegedly by Pakistani terrorists. India blamed Pakistan for carrying out the attacks, an allegation which Pakistan strongly denied. The following 2001–2002 India–Pakistan standoff raised concerns of a possible nuclear confrontation. However, international peace efforts ensured the cooling of tensions between the two nuclear-capable nations.

Apart from this, the most notable was the hijacking of Indian Airlines Flight IC 814 en route New Delhi from Kathmandu, Nepal. The plane was hijacked on 24 December 1999 approximately one hour after takeoff and was taken to Amritsar airport and then to Lahore in Pakistan. After refuelling the plane took off for Dubai and then finally landed in Kandahar, Afghanistan. Under intense media pressure, New Delhi complied with the hijackers' demand and freed Maulana Masood Azhar from his captivity in return for the freedom of the Indian passengers on the flight. The decision, however, cost New Delhi dearly. Maulana, who is believed to be hiding in Karachi, later became the leader of Jaish-e-Mohammed, an organisation which has carried out several terrorist acts against Indian security forces in Kashmir.[5]

On 22 December 2000, a group of terrorists belonging to the Lashkar-e-Toiba stormed the Red Fort in New Delhi. The fort houses an Indian military unit and a high-security interrogation cell used both by the Central Bureau of Investigation and the Indian Army. The terrorists successfully breached the security cover around the Red Fort and opened fire at the Indian military personnel on duty killing two of them on spot. The attack was significant because it was carried out just two days after the declaration of the cease-fire between India and Pakistan.[6]

In 2002, India claimed again that terrorists from Jammu and Kashmir were infiltrating into India, a claim denied by Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf, who claimed that such infiltration had stopped—India's spokesperson for the External Affairs Ministry did away with Pakistan's claim, calling it "terminological inexactitude".[48] Only two months later, two Kashmiri terrorists belonging to Jaish-e-Mohammed raided the Swami Narayan temple complex in Ahmedabad, Gujarat killing 30 people, including 18 women and five children. The attack was carried out on 25 September 2002, just few days after state elections were held in Jammu and Kashmir. Two identical letters found on both the terrorists claimed that the attack was done in retaliation for the deaths of thousands of Muslims during the Gujarat riots.[7]

Two car bombs exploded in south Mumbai on 25 August 2003; one near the Gateway of India and the other at the Zaveri Bazaar, killing at least 48 and injuring 150 people. Though no terrorist group claimed responsibility for the attacks, Mumbai Police and RAW suspected Lashkar-e-Toiba's hand in the twin blasts.[8]

In an unsuccessful attempt, six terrorists belonging to Lashkar-e-Toiba, stormed the Ayodhya Ram Janmbhomi complex on 5 July 2005. Before the terrorists could reach the main disputed site, they were shot down by Indian security forces. One Hindu worshipper and two policemen were injured during the incident.[9]

2001 Indian Parliament attack

[edit]The 2001 Indian Parliament attack was an attack at the Parliament of India in New Delhi on 13 December 2001, during which fourteen people, including the five men who attacked the building, were killed. The perpetrators were Lashkar-e-Taiba (Let) and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) terrorists.[49][50] The attack led to the deaths of five terrorists, six Delhi Police personnel, two Parliament Security Service personnel and a gardener, in total 14[51] and to increased tensions between India and Pakistan, resulting in the 2001–02 India–Pakistan standoff.[52]

2001–02 India–Pakistan standoff

[edit]The 2001–2002 India–Pakistan standoff was a military standoff between India and Pakistan that resulted in the massing of troops on either side of the border and along the Line of Control (LoC) in the region of Kashmir. This was the first major military standoff between India and Pakistan since the Kargil War in 1999. The military buildup was initiated by India responding to a 2001 Indian Parliament attack and the 2001 Jammu and Kashmir legislative assembly attack.[53] India claimed that the attacks were carried out by two Pakistan-based terror groups, the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad, both of whom India has said are backed by Pakistan's ISI[54] a charge that Pakistan denied.[55][56][57] Tensions de-escalated following international diplomatic mediation which resulted in the October 2002 withdrawal of Indian[58] and Pakistani troops[59] from the international border.

2007 Samjhauta Express bombings

[edit]The 2007 Samjhauta Express bombings was a terrorist attack targeted on the Samjhauta Express train on 18 February. The Samjhauta Express is an international train that runs from New Delhi, India to Lahore, Pakistan, and is one of two trains to cross the India–Pakistan border. At least 68 people were killed, mostly Pakistani civilians but also some Indian security personnel and civilians.[60]

2008 Mumbai attacks

[edit]The 2008 Mumbai attacks by ten Pakistani terrorists killed over 173 and wounded 308. The sole surviving gunman Ajmal Kasab who was arrested during the attacks was found to be a Pakistani national. This fact was acknowledged by Pakistani authorities.[61] In May 2010, an Indian court convicted him on four counts of murder, waging war against India, conspiracy and terrorism offences, and sentenced him to death.[62]

India blamed the Lashkar-e-Taiba, a Pakistan-based militant group, for planning and executing the attacks. Indian officials demanded Pakistan extradite suspects for trial. They also said that, given the sophistication of the attacks, the perpetrators "must have had the support of some official agencies in Pakistan".[63] In July 2009 Pakistani authorities confirmed that LeT plotted and financed the attacks from LeT camps in Karachi and Thatta.[64] In November 2009, Pakistani authorities charged seven men they had arrested earlier, of planning and executing the assault.[65]

On 9 April 2015, the foremost ringleader of the attacks, Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi[66][67] was granted bail against surety bonds of Rs. 200,000 (US$690) in Pakistan.[68][69]

Balochistan Insurgency

[edit]The Balochistan Insurgency, ongoing since the early 2000s, involves separatist groups in Pakistan's Balochistan province seeking autonomy. The largest and most prominent group, the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA), has fought for independence, citing long-standing grievances over perceived discrimination and underdevelopment by the central government. The insurgency escalated in March 2025 when the BLA hijacked a train in a remote area of Balochistan, killing 26 people.

Pakistan's military has accused India of supporting the insurgents, citing the 2016 arrest of Indian naval officer Kulbhushan Jadhav, who was convicted of espionage and allegedly aiding Baloch separatists. These accusations have been rejected by India, which denies any involvement in the insurgency. The region's strategic importance, with its oil and mineral wealth, and its proximity to India, has made the conflict a focal point in South Asian military tensions.[70][71]

2025 conflict

[edit]Following the Pahalgam terrorist attack on April 22 which resulted in the deaths of 26 civilians, including 25 Indian tourists and one Nepali national, India–Pakistan relations have reached a critical low point. The attack, attributed by India to the Islamic Resistance Front, an offshoot of the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba, has triggered a series of retaliatory measures from both nations, escalating tensions to levels not seen in years.[72][73] According to Indian news, unnamed sources have stated that Hashim Musa, a former para commando in the Pakistan Army's elite Special Service Group (SSG), was involved in the attack. Trained in covert and unconventional warfare, he is said to have joined the banned terror group, Lashkar-e-Taiba, after his dismissal from SSG and to have infiltrated Kashmir in September 2023. Unnamed sources say his name and SSG background were revealed during the interrogation of Over Ground Workers (OGWs) who supported the perpetrators.[74]

Diplomatic fallout

[edit]India's response

[edit]In response to escalating tensions, India has suspended the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, placing the long-standing water-sharing agreement "in abeyance" due to what it alleges is Pakistan's ongoing support for cross-border terrorism. Additionally, India has imposed visa and diplomatic restrictions, halting visa services for Pakistani nationals and expelling several Pakistani diplomats. As part of broader punitive measures, the Attari–Wagah border has been closed, effectively cutting off overland trade and further straining bilateral ties.[75][76]

Additionally, authorities across various states started a crackdown on illegal immigrants from Pakistan and began the process of deporting them. Many of these illegal immigrants had reportedly possessed voter IDs and ration cards, sparking a major controversy and debate as non-citizens do not have right to vote.[77] Furthermore, short term visas of several Pakistani visitors, some of who were married to Indians, were also being cancelled.[78]

Pakistan's countermeasures

[edit]In retaliation, Pakistan announced a series of countermeasures. It suspended the 1972 Shimla Agreement, which had emphasized the peaceful resolution of bilateral disputes. Pakistan also closed its airspace to Indian aircraft and halted all trade with India. On the diplomatic front, Indian diplomats have been expelled, and the staff size at the Indian High Commission in Islamabad has been significantly reduced, deepening the diplomatic rift between the two countries.[73][79]

India's missile strikes

[edit]On May 6, India targeted Pakistan proper and Pakistan-administered Kashmir with multiple airstrikes as part of Operation Sindoor, marking a significant escalation of the conflict.[80] India announced that it struck nine "terrorist infrastructure" sites in Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir, stating the targets were used to plan and direct attacks. It stressed the strikes were precise, avoided Pakistani military sites, and were non-escalatory. Jaish-e-Mohammad stronghold of Bahawalpur and Lashkar-e-Taiba's base in Muridke were among the targets. Pakistan reported hits in Muzaffarabad, Kotli, and Bahawalpur.[81][82]

Diplomatic expulsions

[edit]On 13 May, India reportedly declared Md. Ehsan Ur Rahim, a staff member at the Pakistan High Commission, persona non grata for engaging in activities inconsistent with his diplomatic status. He was allegedly involved in espionage.[83][84] More information on the expulsion was revealed to Indian media after 17 May when a YouTuber was arrested.[85] It was alleged that Ehsan used an Indian YouTuber, namely Jyoti Malhotra, for espionage activities.[86] He reportedly befriended the youtuber in 2023 and maintained close contact with her during the four-day military conflict. Over time, he reportedly cultivated her as an asset by introducing her to Pakistani contacts and facilitating her visit to Pakistan, where she met intelligence officials. The youtuber is believed to have maintained communication with these officials through encrypted platforms like WhatsApp, Telegram, and Snapchat, and shared sensitive information, according to Indian police.[87][88]

Weapons of mass destruction

[edit]India has a long history of nuclear weapons development.[89] The origins of India's nuclear program date back to 1944, when it started a nuclear program soon after obtaining independence.[90] In the 1940s–1960s, India's nuclear program slowly matured towards militarisation and expanded the nuclear power infrastructure throughout the country.[89] Decisions on the development of nuclear weapons were made by Indian political leaders after the 1962 Chinese invasion and territorial annexation of North India. In 1967, India's nuclear program was aimed at the development of nuclear weapons, with Indira Gandhi overseeing the development of the weapons.[91] In 1971, India gained military and political momentum over Pakistan, after their success in the Indo-Pakistani war of 1971. Starting preparations for a nuclear test in 1972, India finally exploded its first nuclear bomb at the Pokhran test range, codenamed Smiling Buddha, in 1974.[91] During the 1980s–90s, India began development of space and nuclear armed rockets with its Integrated Guided Missile Development Program, which marked Pakistan's efforts to engage in the space race with India.[92] Pakistan's own Integrated Missile Research and Development Programme developed space and nuclear missiles and began unmanned flight tests of its space vehicles in the mid-1990s.[92]

After their defeat in the Indo-Pakistani war in 1971, Pakistan launched its own nuclear bomb program in 1972, and accelerated its efforts in 1974, after India exploded its first nuclear bomb in Pokhran test range.[91][93] This large-scale nuclear bomb program was directly in response to India's nuclear program.[94] In 1983, Pakistan achieved a major milestone in its efforts after it covertly performed a series of non-fission tests, codenamed Kirana-I. No official announcements of such tests were made by the Pakistani Government.[94] Over the next several years, Pakistan expanded and modernized nuclear power projects around the country to supply its electricity sector and to provide back-up support and benefit to its national economy. In 1988, a mutual understanding was reached between the two countries in which each pledged not to attack nuclear facilities. Agreements on cultural exchanges and civil aviation were also initiated in 1988.[94] Finally, in May 1998, India carried out its second nuclear test series (see Pokhran-II) which caused Pakistan to reply with its own test series, also in May 1998 (see Chagai-I and Chagai-II).

The U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency's 2025 assessment stated that Pakistan viewed India as an existential threat and was modernizing its military, focusing on tactical nuclear weapons to counter India's conventional superiority. The report estimated Pakistan's arsenal at 170 warheads in 2024, potentially rising to 200 by 2025, and noted growing defense ties with China, a key supplier for materials and technologies for its weapons of mass destruction programs.[95][96]

In August 2025, Pakistan's army chief Field Marshal Asim Munir issued a nuclear threat against India during a black-tie dinner in Tampa, Florida, stating that if Pakistan faced an existential threat, "we'll take half the world down with us."[97][98] India condemned the remarks as "nuclear sabre-rattling," with Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal stating that it was "Pakistan's stock-in-trade" and adding that "the international community can draw its own conclusions on the irresponsibility inherent in such remarks."[99] Pakistan's Foreign Office claimed the remarks were "distorted."[100]

Terrorism charges

[edit]Border terrorism

[edit]Countries including India and the United States have demanded that Pakistan stop using its territory as a base for terrorist groups following multiple terrorist attacks by Islamic jihadists in Kashmir and other parts of India.[101] The Pakistani government has denied the accusation and accused India of sponsoring so-called "state-backed terror".[102]

Fugitives

[edit]India has accused some of the most wanted Indian fugitives, such as Dawood Ibrahim, of having a presence in Pakistan. On 11 May 2011, India released a list of 50 "Most Wanted Fugitives" hiding in Pakistan. This was to tactically pressure Pakistan after the killing of Osama bin Laden in his compound in Abbottabad.[103] After two errors in the list received publicity, the Central Bureau of Investigation removed it from their website, pending review.[104] After this incident, the Pakistani interior ministry rejected the list forwarded by India to Islamabad, saying it should first probe if those named in the list were even living in the country.[105]

Talks and other confidence-building measures

[edit]After the 1971 war, Pakistan and India made slow progress towards the normalisation of relations. In July 1972, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Pakistani President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto met in the Indian hill station of Shimla. They signed the Shimla Agreement, by which India would return all Pakistani personnel (over 90,000) and captured territory in the west, and the two countries would "settle their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations." Diplomatic and trade relations were also re-established in 1976.

1990s

[edit]In 1997, high-level Indo-Pakistan talks resumed after a three-year pause. The Prime Ministers of Pakistan and India met twice and the foreign secretaries conducted three rounds of talks. In June 1997, the foreign secretaries identified eight "outstanding issues" around which continuing talks would be focused. The conflict over the status of Kashmir, (referred by India as Jammu and Kashmir), an issue since Independence, remains the major stumbling block in their dialogue. India maintains that the entire former princely state is an integral part of the Indian union, while Pakistan insists that UN resolutions calling for self-determination of the people of the state/province must be taken into account. It however refuses to abide by the previous part of the resolution, which calls for it to vacate all territories occupied.

In September 1997, the talks broke down over the structure of how to deal with the issues of Kashmir, and peace and security. Pakistan advocated that the issues be treated by separate working groups. India responded that the two issues be taken up along with six others on a simultaneous basis.

Attempts to restart dialogue between the two nations were given a major boost by the February 1999 meeting of both Prime Ministers in Lahore and their signing of three agreements.

2000s

[edit]In 2001, a summit was called in Agra; Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf turned up to meet Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee. The talks fell through.

On 20 June 2004, with a new government in place in India, both countries agreed to extend a nuclear testing ban and to set up a hotline between their foreign secretaries aimed at preventing misunderstandings that might lead to a nuclear war.[106]

Baglihar Dam issue was a new issue raised by Pakistan in 2005.

After Dr. Manmohan Singh become prime minister of India in May 2004, the Punjab provincial Government declared it would develop Gah, his place of birth, as a model village in his honour and name a school after him.[107] There is also a village in India named Pakistan, despite occasional pressure over the years to change its name the villagers have resisted.[108]

Violent activities in the region declined in 2004. There are two main reasons for this: warming of relations between New Delhi and Islamabad which consequently lead to a ceasefire between the two countries in 2003 and the fencing of the Line of Control being carried out by the Indian Army. Moreover, coming under intense international pressure, Islamabad was compelled to take action against the militants' training camps on its territory. In 2004, the two countries also agreed upon decreasing the number of troops present in the region.

Under pressure, Kashmiri militant organisations made an offer for talks and negotiations with New Delhi, which India welcomed.

India's Border Security Force blamed the Pakistani military for providing cover-fire for the terrorists whenever they infiltrated into Indian territory from Pakistan. Pakistan in turn has also blamed India for providing support to terrorist organisations operating in Pakistan such as the BLA.

In 2005, Pakistan's information minister, Sheikh Rashid, was alleged to have run a terrorist training camp in 1990 in N.W. Frontier, Pakistan. The Pakistani government dismissed the charges against its minister as an attempt to hamper the ongoing peace process between the two neighbours.

Both India and Pakistan have launched several mutual confidence-building measures (CBMs) to ease tensions between the two. These include more high-level talks, easing visa restrictions, and restarting of cricket matches between the two. The new bus service between Srinagar and Muzaffarabad has also helped bring the two sides closer. Pakistan and India have also decided to co-operate on economic fronts.

Some improvements in the relations are seen with the re-opening of a series of transportation networks near the India–Pakistan border, with the most important being bus routes and railway lines.

A major clash between Indian security forces and militants occurred when a group of insurgents tried to infiltrate into Kashmir from Pakistan in July 2005. The same month also saw a Kashmiri militant attack on Ayodhya and Srinagar. However, these developments had little impact on the peace process.

An Indian man held in Pakistani prisons since 1975 as an accused spy walked across the border to freedom 3 March 2008, an unconditional release that Pakistan said was done to improve relations between the two countries.[109]

In 2006, a "Friends Without Borders" scheme began with the help of two British tourists. The idea was that Indian and Pakistani children would make pen pals and write friendly letters to each other. The idea was so successful in both countries that the organisation found it "impossible to keep up". The World's Largest Love Letter was recently sent from India to Pakistan.[110]

2010s

[edit]

In December 2010, several Pakistani newspapers published stories about India's leadership and relationship with militants in Pakistan that the papers claimed were found in the United States diplomatic cables leak. A British newspaper, The Guardian, which had the Wikileaks cables in its possession reviewed the cables and concluded that the Pakistani claims were "not accurate" and that "WikiLeaks [was] being exploited for propaganda purposes."[112]

On 10 February 2011, India agreed to resume talks with Pakistan which were suspended after 26/11 Mumbai Attacks.[113] India had put on hold all the diplomatic relations saying it will only continue if Pakistan will act against the accused of Mumbai attacks.

On 13 April 2012, following a thaw in relations whereby India gained most favoured nation status in the country, India announced the removal of foreign direct investment restrictions from Pakistan to India.[114]

The Foreign Minister of Pakistan Hina Rabbani Khar on 11 July 2012, stated in Phnom Penh that her country is willing to resolve some of the disputes, including Sir Creek and Siachen, on the basis of agreements reached in past.[115]

On 7 September 2012, Indian External Affairs Minister S. M. Krishna would pay a 3-day visit to Pakistan to review the progress of bilateral dialogue with his Pakistani counterpart.[116]

In August 2019, following the approval of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Bill in the Indian Parliament, which revoked the special status of Jammu and Kashmir,[117][118] further tension was brought between the two countries, with Pakistan downgrading their diplomatic ties, closing its airspace, and suspending bilateral trade with India.[119]

The Kartarpur Corridor was opened in November 2019.[120]

2020s

[edit]On 25 February 2021, India and Pakistan issued a joint statement indicating that both sides agreed to stop firing at each other at the Line of Control (LOC, disputed de facto border) in Kashmir.[121]

Despite this, in July 2021 Indian government rejected Pakistan's call for talks, stating that "Peace, prosperity can't coexist with terrorism".[122]

On 16 October 2024, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar met Pakistan's Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif to discuss topics at the SCO Summit dinner in Islamabad.[123][124][125]

Response to natural calamities

[edit]2001 Gujarat earthquake in India

[edit]In response to the 2001 Gujarat earthquake, Pakistani President Pervez Mushrraf sent a plane load of relief supplies from Islamabad to Ahmedabad.[126] They carried 200 tents and more than 2,000 blankets.[127] Furthermore, the President called Indian PM to express his 'sympathy' over the loss from the earthquake.[128]

2005 earthquake in Pakistan

[edit]India offered aid to Pakistan in response to the 2005 Kashmir earthquake on 8 October. Indian and Pakistani High Commissioners consulted with one another regarding cooperation in relief work. India sent 25 tonnes of relief material to Pakistan including food, blankets and medicine. Large Indian companies such as Infosys offered aid up to $226,000. On 12 October, an Ilyushin-76 cargo plane ferried across seven truckloads (about 82 tons) of army medicines, 15,000 blankets and 50 tents and returned to New Delhi. A senior air force official also stated that they had been asked by the Indian government to be ready to fly out another similar consignment.[129]

On 14 October, India dispatched the second consignment of relief material to Pakistan, by train through the Wagah Border. The consignment included 5,000 blankets, 370 tents, 5 tons of plastic sheets and 12 tons of medicine. A third consignment of medicine and relief material was also sent shortly afterwards by train.[130] India also pledged $25 million as aid to Pakistan.[131] India opened the first of three points at Chakan Da Bagh, in Poonch, on the Line of Control between India and Pakistan for earthquake relief work.[132]

2022 Pakistan floods

[edit]Amid the 2022 Pakistan floods, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed his "heartfelt condolences to families of the victims".[133] As of 30 August, it has been reported that the government of India is considering sending relief aid to Pakistan.[134]

Economic relations

[edit]India and Pakistan have curtailed formal trade; South Asia, the region inhabited by the two countries, is the least economically integrated region in the world, with only 5% of its trade conducted internally.[135] However, there is an informal bilateral trade of around $10 billion, with most of the goods imported by Pakistan.[136]

During the 2025 India–Pakistan conflict, bilateral maritime trade was suspended.[137]

Social relations

[edit]Organisational ties

[edit]

India and Pakistan both feature in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the Commonwealth of Nations. SAARC membership initially helped the two countries come to certain agreements, such as simplifying visa access for each other, while in the early years of independence, one of the reasons both countries remained in the Commonwealth was arguably to prevent a British preference towards the other country.[139][140] Eventually SAARC became defunct largely due to the impasse between the two nations,[141] and since the 2025 Pahalgam attack, India removed SAARC visa privileges for Pakistani nationals.[142]

Aman ki Asha is a joint venture and campaign between The Times of India and the Jang Group started in 2010 calling for mutual peace and development of diplomatic and cultural relations.[143]

Cultural links

[edit]India and Pakistan, particularly Northern India and Eastern Pakistan, to some degree have similar cultures, cuisines and languages due to common Indo-Aryan heritage which spans through the two countries and throughout much of the northern subcontinent which also underpin the historical ties between the two. Pakistani singers, musicians, comedians and entertainers have enjoyed widespread popularity in India, with many achieving overnight fame in the Indian film industry Bollywood. Likewise, Indian music and film are very popular in Pakistan. Being located in the northernmost region of South Asia, Pakistan's culture is somewhat similar to that of North India, especially the northwest.

The Punjab region was split into Punjab, Pakistan and Punjab, India following the independence and partition of the two countries in 1947. The Punjabi people are today the largest ethnic group in Pakistan and also an important ethnic group of northern India. The founder of Sikhism was born in the modern-day Pakistani Punjab province, in the city of Nankana Sahib. Each year, millions of Indian Sikh pilgrims cross over to visit holy Sikh sites in Nankana Sahib. The Sindhi people are the native ethnic group of the Pakistani province of Sindh. Many Hindu Sindhis migrated to India in 1947, making the country home to a sizeable Sindhi community. In addition, the millions of Muslims who migrated from India to the newly created Pakistan during independence came to be known as the Muhajir people; they are settled predominantly in Karachi and still maintain family links in India.

Relations between Pakistan and India have also resumed through platforms such as media and communications.

Geographic links

[edit]

The India–Pakistan border is the official international boundary that demarcates the Indian states of Punjab, Rajasthan and Gujarat from the Pakistani provinces of Punjab and Sindh. The Wagah border is the only road crossing between India and Pakistan and lies on the Grand Trunk Road, connecting Lahore, Pakistan with Amritsar, India. Each evening, the Wagah–Attari border ceremony takes place, in which the flags are lowered and guards on both sides make a pompous military display and exchange handshakes.

Linguistic ties

[edit]

Hindustani is the lingua franca of North India and Pakistan, as well as the official language of both countries, under the standard registers Hindi and Urdu, respectively. Standard Urdu is mutually intelligible with standard Hindi. Hindustani is also widely understood and used as a lingua franca amongst South Asians including Sri Lankans, Nepalis and Bangladeshis, and is the language of Bollywood, which is enjoyed throughout much of the subcontinent.

Apart from Hindustani, India and Pakistan also share a distribution of the Punjabi language (written in the Gurmukhi script in Indian Punjab, and the Shahmukhi script in Pakistani Punjab), Kashmiri language and Sindhi language, mainly due to population exchange. These languages belong to a common Indo-Aryan family that are spoken in countries across the subcontinent.

Matrimonial ties

[edit]Some Indian and Pakistani people marry across the border at instances. Many Indians and Pakistanis in the diaspora, especially in the United States, intermarry, as there are large cultural similarities between the two countries respectively.[145]

In April 2010 a high-profile Pakistani cricketer, Shoaib Malik married the Indian tennis star Sania Mirza.[146] The wedding received much media attention and was said to transfix both India and Pakistan.[147]

Sporting ties

[edit]

Cricket and hockey matches between the two (as well as other sports to a lesser degree such as those of the SAARC/South Asian Games) have often been political in nature. During the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan General Zia-ul Haq travelled to India for a bout of "cricket diplomacy" to keep India from supporting the Soviets by opening another front. Pervez Musharaff also tried to do the same more than a decade later but to no avail.

Following the 2008 terror attack in Mumbai, India stopped playing bilateral cricket series against Pakistan. Since then, the Indian team has only played against them in ICC and Asian Cricket Council events such as the Cricket World Cup, T20 World Cup, Asia Cup and ICC Champions Trophy. In 2017, the then Sports Minister of India, Vijay Goel opposed further bilateral series due to Pakistan's alleged sponsoring of terrorism, saying that "there cannot be sports relations between the two countries [while] there is terrorism from the Pakistani side."[148] The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) also opposed any further series without the permission of the Indian government.[149] The BCCI also did not allow Pakistani players to play in the Indian Premier League in the aftermath of the 2008 terror attack, although they were part of the inaugural season.[150]

The two nations also share some of the same traditional games, such as kabaddi and kho kho.[151] In tennis, Rohan Bopanna of India and Aisam-ul-Haq Qureshi of Pakistan have formed a successful duo and have been dubbed as the "Indo-Pak Express".[152]

Diasporic relations

[edit]The large size of the Indian diaspora and Pakistani diaspora in many different countries throughout the world has created strong diasporic relations. It is quite common for a "Little India" and a "Little Pakistan" to co-exist in South Asian ethnic enclaves in overseas countries.

British Indians and British Pakistanis, the largest and second-largest ethnic minorities living in the United Kingdom respectively, are said to have friendly relations with one another.[153][154] There are various cities such as Birmingham, Blackburn and Manchester where British Indians and British Pakistanis live alongside each other in peace and harmony. Both Indians and Pakistanis living in the UK fit under the category of British Asian. The UK is also home to the Pakistan & India friendship forum.[155] In the United States, Indians and Pakistanis are classified under the South Asian American category and share many cultural traits, with intermarriage being common.[145]

The British MEP Sajjad Karim is of Pakistani origin. He is a member of the European Parliament Friends of India Group, Karim was also responsible for opening up Europe to free trade with India.[156][157] He narrowly escaped the Mumbai attacks at Hotel Taj in November 2008. Despite the atrocity, Karim does not wish the remaining killer Ajmal Kasab to be sentenced to death. He said: "I believe he had a fair and transparent trial and I support the guilty verdict. But I am not a supporter of capital punishment. I believe he should be given a life sentence, but that life should mean life."[158][159]

Head of state visits

[edit]| Year | Name |

|---|---|

| 1953 | Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru |

| 1960 | Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru |

| 1964 | Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri |

| 1988 | Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi (Funeral of Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan and SAARC Summit) |

| 1989 | Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi |

| 1999 | Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee |

| 2004 | Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee (SAARC Summit) |

| 2015 | Prime Minister Narendra Modi (Informal meeting with Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif) |

See also

[edit]Foreign relations

[edit]History

[edit]Human rights

[edit]Cultural issues

[edit]Wars and skirmishes

[edit]Sports

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 221–222

- ^ Area, Population, Density and Urban/Rural Proportion by Administrative Units Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marshall Cavendish (September 2006). World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2.

- ^ "Pakistan Ups the Ante With India on Terrorism". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ "The age of minimalism in India-Pakistan ties". The Hindu. 7 November 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Pakistan-India Trade: What Needs to Be Done? What Does It Matter? Asia Centre Program. The Wilson Centre. Accessed 1 March 2022.

- ^ Nisha Taneja (Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations); Shaheen Rafi Khan; Moeed Yusuf; Shahbaz Bokhari; Shoaib Aziz (January 2007). Zareen Fatima Naqvi and Philip Schuler (ed.). "Chapter 4: India–Pakistan Trade: The View from the Indian Side (p. 72-77) Chapter 5: Quantifying Informal Trade Between Pakistan and India (p. 87-104)". The Challenges and Potential of Pakistan-India Trade. (The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, June 2007). Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ Ahmed, Sadiq; Ghani, Ejaz. "South Asia's Growth and Regional Integration: An Overview" (PDF). World Bank. p. 33. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ "2017 BBC World Service Global Poll" (PDF). BBC World Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ "Details for: South Asia's geography of conflict / › ACKU catalog". archive.af. Retrieved 20 December 2024.

- ^ Shaikh, Dr Muhammad Ali (31 October 2021). "HISTORY: THE BRITISH CONQUEST OF SINDH". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 20 December 2024.

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha (20 November 2017), "The Creation of Pakistan", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-114?p=emailayfh9ygdluhbw&d=/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-114 (inactive 1 July 2025), ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7, retrieved 24 April 2025

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar (2010). The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia: Refugees, Boundaries, Histories. Columbia University Press. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-0-231-13847-5.

Second, it was feared that if an exchange of populations was agreed to in principle in Punjab, ' there was the likelihood of trouble breaking out in other parts of the subcontinent to force Muslims in the Indian Dominion to move to Pakistan. If that happened, we would find ourselves with inadequate land and other resources to support the influx.' Punjab could set a very dangerous precedent for the rest of the subcontinent. Given that Muslims in the rest of India, some 42 million, formed a population larger than the entire population of West Pakistan at the time, economic rationality eschewed such a forced migration. However, in divided Punjab, millions of people were already on the move, and the two governments had to respond to this mass movement. Thus, despite these important reservations, the establishment of the MEO led to an acceptance of a 'transfer of populations' in divided Punjab, too, 'to give a sense of security' to ravaged communities on both sides. A statement of the Indian government's position of such a transfer across divided Punjab was made in the legislature by Neogy on November 18, 1947. He stated that although the Indian government's policy was 'to discourage mass migration from one province to another.' Punjab was to be an exception. In the rest of the subcontinent migrations were not to be on a planned basis, but a matter of individual choice. This exceptional character of movements across divided Punjab needs to be emphasized, for the agreed and 'planned evacuations' by the two governments formed the context of those displacements.

- ^ Peter Gatrell (2013). The Making of the Modern Refugee. OUP Oxford. pp. 149–. ISBN 978-0-19-967416-9.

Notwithstanding the accumulated evidence of inter-communal tension, the signatories to the agreement that divided the Raj did not expect the transfer of power and the partition of India to be accompanied by a mass movement of population. Partition was conceived as a means of preventing migration on a large scale because the borders would be adjusted instead. Minorities need not be troubled by the new configuration. As Pakistan's first Prime Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, affirmed, 'the division of India into Pakistan and India Dominions was based on the principle that minorities will stay where they were and that the two states will afford all protection to them as citizens of the respective states'.

- ^ "The partition of India and retributive genocide in the Punjab, 1946–47: means, methods, and purposes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ^ Zamindar, Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali (2013). India–Pakistan Partition 1947 and forced migration. Wiley Online Library. ISBN 978-1-4443-3489-0.

Some 12 million people were displaced in the divided province of Punjab alone, and up to 20 million in the subcontinent as a whole.

- ^ Lumby 1954, p. 238

- ^ "Letter Inviting India to Intervene". Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 238–239

- ^ Haroon, Sana (1 December 2007). Frontier of faith: Islam in the Indo-Afghan borderland. Columbia University Press. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-231-70013-9. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ a b Ganguly, Sumit (17 December 2020), "India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh: Civil-Military Relations", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1926, ISBN 978-0-19-022863-7

- ^ a b Pye, Lucian W.; Schofield, Victoria (2000). "Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan, and the Unfinished War". Foreign Affairs. 79 (6): 190. doi:10.2307/20050024. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 20050024. S2CID 129061164.

- ^ Chandigarh, India – Main News. Tribuneindia.com. Retrieved on 14 April 2011.

- ^ David R. Higgins 2016.

- ^ Rachna Bisht 2015.

- ^ Lyon, Peter (2008). Conflict between India and Pakistan: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-57607-712-2. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "SJIR: The Fate of Kashmir: International Law or Lawlessness?". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Guha 2007, pp. 675–678.

- ^ a b Myra 2017, pp. 27–66.

- ^ "PARLIAMENT QUESTIONS, LOK SABHA". 2 December 2008. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Rodrigo 2006.

- ^ Reddy, B. Muralidhar (17 August 2003). "Over 4,000 soldiers killed in Kargil: Sharif". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 31 May 2004. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Pak quietly names 453 men killed in Kargil war". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Team, BS Web (3 December 2015). "India was ready to cross LoC, use nuclear weapons in Kargil war". Business Standard India. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ a b c "The story of how Nawaz Sharif pulled back from nuclear war". Foreign Policy. 14 May 2013. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Unquenchable thirst." The Economist, 19 November 2011.

- ^ The ISI and Terrorism: Behind the Accusations Archived 24 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Council on Foreign Relations, 28 May 2009

- ^ "Pakistan's New Generation of Terrorists". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ Stephen Schwartz (19 August 2006). "A threat to the world". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ "Bombing at Kashmir assembly kills at least 29". Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (8 May 2007). "What happened to Muslims in Jammu? Local identity, '"the massacre" of 1947' and the roots of the 'Kashmir problem'". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 24 (2): 111–134. doi:10.1080/00856400108723454.

- ^ Rahman, Maseeh (15 July 2002). "Panic in the dark as slum is attacked by Kashmiri militants". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Ahmad, Mukhtar (13 July 2002). "29 killed in militant attack in Jammu". Rediff. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "Terrorists behind Qasim Nagar massacre nabbed". Rediff. 6 September 2002. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ McCarthy, Rory (15 July 2002). "Massacre in Kashmir slum renews fear of war". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ "Militants attack Indian army base in Kashmir 'killing 17'". BBC News. 18 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ "Pulwama Attack 2019, everything about J&K terror attack on CRPF by terrorist Adil Ahmed Dar, Jaish-e-Mohammad". India Today. 16 February 2019.

- ^ "India rejects Musharraf's claim on infiltration". The Economic Times. 28 July 2002. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ "Govt blames LeT for Parliament attack". Rediff.com (14 December 2001). Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ Embassy of India – Washington DC (official website) United States of America Archived 11 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Indianembassy.org. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ PTI (13 December 2011). "Parliament attack victims remembered". The Hindu. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "From Kashmir to the FATA: The ISI Loses Control". Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Rajesh M. Basrur (14 December 2009). "The lessons of Kargil as learned by India". In Peter R. Lavoy (ed.). Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia: The Causes and Consequences of the Kargil Conflict (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-521-76721-7. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ "Who will strike first", The Economist, 20 December 2001.

- ^ Jamal Afridi (9 July 2009). "Kashmir Militant Extremists". Council Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

Pakistan denies any ongoing collaboration between the ISI and militants, stressing a change of course after 11 September 2001.

- ^ Perlez, Jane (29 November 2008). "Pakistan Denies Any Role in Mumbai Attacks". The New York Times. Mumbai (India);Pakistan. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "Attack on Indian parliament heightens danger of Indo-Pakistan war". Wsws.org. 20 December 2001. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "India to withdraw troops from Pak border" Archived 30 November 2003 at the Wayback Machine, Times of India, 16 October 2002.

- ^ "Pakistan to withdraw front-line troops", BBC, 17 October 2002.

- ^ "Indian police release sketches of bomb suspects". Reuters. 21 February 2007.

- ^ "DAWN.COM | Pakistan | Surviving-gunmans-identity-established-as-Pakistani-ss". www.dawn.com.

- ^ "DAWN.COM | World | Ajmal Kasab sentenced to death for Mumbai attacks". www.dawn.com.

- ^ Lakshmi, Rama (6 January 2009). "India Gives Pakistan Findings From Mumbai Probe, Urges Action Against Suspects". The Washington Post.

- ^ Hussain, Zahid (28 July 2009). "Islamabad Tells of Plot by Lashkar". The Wall Street Journal. Islamabad. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ Schifrin, Nick (25 November 2009). "Mumbai terror attacks: 7 Pakistanis charged". United States: ABC News. Archived from the original on 27 November 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Masood, Salman (12 February 2009). "Pakistan Announces Arrests for Mumbai Attacks". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ Haider, Kamran (12 February 2009). "Pakistan says it arrests Mumbai attack plotters". Reuters. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ "Pak court grants bail to Mumbai terror attack accused Lakhvi". Yahoo! News. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Lakhvi gets bail, again". Dawn. Pakistan. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Pakistan moves closer to Bangladesh as India watches warily". www.bbc.com. 17 March 2025. Retrieved 19 March 2025.

- ^ Press, Associated (14 March 2025). "Pakistan accuses India of sponsoring militant terror group after train hijacking". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 March 2025.

- ^ "Deadly Kashmir attack threatens new escalation between India and Pakistan". 2025.

- ^ a b Blair, Anthony (28 April 2025). "Tourist captures Kashmir terror attack as he films himself ziplining". Retrieved 30 April 2025.

- ^ Ranjan, Mukesh (29 April 2025). "Hashim Musa, ex-Pakistan Army Special Forces soldier, prime suspect in Pahalgam terror attack". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 7 May 2025.

- ^ "Pakistan preparing to challenge India's suspension of water treaty, minister says". 2025.

- ^ Campbell, Matthew (26 April 2025). "Are India and Pakistan on the cusp of war over water?". www.thetimes.com. Retrieved 30 April 2025.

- ^ "22 women with Pakistani citizenship found in Moradabad; many have grandchildren, families total over 500".

- ^ "Fate of pregnant Maryam, illegal settler Seema hangs in balance as UP speeds up deportation of Pakistanis".

- ^ "India File: A deadly reminder from Kashmir". 2025.

- ^ "Pakistan 'attacked with missiles' - as India says it targeted terrorist camps". Sky News. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ "What we know about India's strike on Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir". www.bbc.com. 7 May 2025. Retrieved 7 May 2025.

- ^ "Operation Sindoor: Full list of terrorist camps in Pakistan, PoJK targeted by Indian strikes". The Hindu. 7 May 2025. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 7 May 2025.

- ^ Chaudhury, Dipanjan Roy (13 May 2025). "Pakistan High Commissioner staffer declared persona non grata for 'espionage'". The Economic Times. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ "Pakistani official declared persona non grata". Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original on 14 May 2025. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ "Haryana-based YouTuber among 6 arrested for spying for Pakistan". India Today. 17 May 2025. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ "India-Pakistan tensions: YouTuber arrested for allegedly spying for Pakistan". www.bbc.com. 19 May 2025. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ "Cops Say Haryana YouTuber Was Groomed As A Pak Asset. How She Was Lured". www.ndtv.com. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ "How YouTuber Jyoti Malhotra used social media apps to pass secrets to Pakistan". The Economic Times. 18 May 2025. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ a b Carey Sublette (30 March 2001). "Indian nuclear program: origin". Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Indian nuclear program: originwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c India's First Bomb: 1967-1974. "India's First Bomb: 1967-1974". India's First Bomb: 1967-1974. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lodhi, SFS. "Pakistan's space technology". Pakistan Space Journal. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Pakistan atomic bomb project: The Beginning. "Pakistan atomic bomb project: The Beginning". Pakistan atomic bomb project: The Beginning. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ a b c "The Eighties: Developing Capabilities". Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Jacob, Jayanth (25 May 2025). "Pakistan modernising nuclear arsenal; views India as 'existential threat', says US intelligence". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 27 May 2025.

- ^ "Pak's Mass Destruction Weapons Mention In US Threat Report - And China Link". NDTV. Retrieved 27 May 2025.

- ^ "India decries 'sabre rattling' after Pakistan army chief's reported nuclear remarks". Reuters. 11 August 2025. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Swami, Praveen (10 August 2025). "ThePrint Exclusive: Asim Munir's India nuke threat from US ballroom—'will take half the world down'". ThePrint. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ ""Nuke Sabre-Rattling Is Pak's Stock-In-Trade": India On Asim Munir Comments". NDTV. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Pakistan denies nuclear threat claims, says India misrepresenting army chief's US remarks". Arab News PK. 12 August 2025. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Pakistan Rejects US, India Call to Curb Cross-Border Terrorism". VOA. 23 June 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ Kakar, Abdul Hai; Siddique, Abubakar (18 September 2016). "Baluch Separatists Call For India To Intervene Like In Bangladesh". gandhara.rferl.org. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ "India releases list of 50 'most wanted fugitives' in Pak". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ "India: 'Most wanted' errors embarrass government". BBC News. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Pakistan rejects India's list of 50 most wanted". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 3 June 2011.

- ^ "Nuke hotline for India, Pakistan". CNN. 20 June 2004. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ "Schoolmate wants to meet PM". The Hindu. 23 June 2007. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007.

- ^ "This 'Pakistan' has no Muslims". India Today. 24 January 2009.

- ^ "Freed Indian man arrives back home". Archived from the original on 9 March 2008.

- ^ "Friends Without Borders – international penpal program between India and Pakistan". friendswithoutborders.org.

- ^ "A hug and high tea: Indian PM makes surprise visit to Pakistan". Reuters. 25 December 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Declan Walsh, Pakistani media publish fake WikiLeaks cables attacking India The Guardian 9 December 2010

- ^ "A New Turn in India Pakistan Ties". 14 February 2011.

- ^ Banerji, Annie (13 April 2012). "India to allow FDI from Pakistan, open border post". In.reuters.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ "Pak willing to resolve bilateral disputes with India: Hina Rabbani Khar". 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Krishna to undertake 3-day visit to Pakistan from Sept 7". 24 July 2012.

- ^ "India strips disputed Kashmir of special status". 5 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ "UN expresses concern over India's move to revoke special status of Kashmir". radio.gov.pk. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ "Pakistan sends back Indian High Commissioner Ajay Bisaria, suspends bilateral trade". timesnownews.com. 7 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ "Pakistan opens visa-free border crossing for India Sikhs". gulfnews.com. 9 November 2019. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

Kartarpur, Pakistan: The prime ministers of India and Pakistan inaugurated on Saturday a visa-free border crossing for Sikh pilgrims from India, allowing thousands of pilgrims to easily visit a Sikh shrine just inside Pakistan each day.

- ^ "India, Pakistan agree to stop firing at Kashmir border". Deutsche Welle. DW. 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Peace, prosperity can't coexist with terrorism: Rajnath Singh at SCO meet". The Indian Express. 29 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "PM Shehbaz welcomes state dignitaries to SCO dinner". Dawn. 15 October 2024.

- ^ Haidar, Suhasini (16 October 2024). "SCO Summit in Islamabad: Jaishankar attends day 2 meet". The Hindu.

- ^ "How S Jaishankar started his day in Islamabad ahead of SCO Summit". India Today. 16 October 2024.

- ^ "Quake may improve India Pakistan ties". CNN. 2 February 2001. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Rival Pakistan offers India help". BBC News. 30 January 2001.

- ^ "Gujarat gets Musharraf to dial PM in New Delhi". Archived from the original on 4 October 2012.

- ^ "Indian troops cross LoC to back up relief efforts". 13 October 2005.

- ^ "Hindustan Times – Archive News". Archived from the original on 4 November 2005. Retrieved 15 October 2005.

- ^ "BBC NEWS – South Asia – India offers Pakistan $25m in aid". 27 October 2005.

- ^ "White flags at the LoC". Rediff. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Pakistan Floods: India Offers Condolences, Several Countries Extend Help As Monsoon Death Toll Crosses 1,100". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "India Reportedly Discussing Flood Aid As Pak Minister Talks Food Import". NDTV.com. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Realizing the Promise of Regional Trade in South Asia". World Bank. Retrieved 10 May 2025.

- ^ Sharma, Priyanka Shankar, Yashraj. "The $10bn India-Pakistan trade secret hidden by official data". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 10 May 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "India and Pakistan Halt Maritime Trade". The Maritime Executive. Retrieved 10 May 2025.

- ^ Kirpalani, Renuka (4 February 2022). "Winding Across Borders Remembering the First-Ever SAARC Car Rally". Outlook Traveller. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- ^ Gangal, S.C. (1 January 1966). "The Commonwealth and Indo-Pakistani Relations". International Studies. 8 (1–2): 134–149. doi:10.1177/002088176600800107. ISSN 0020-8817.

- ^ "Pakistan and the Commonwealth". The Round Table. 89 (354): 157–160. 1 April 2000. doi:10.1080/750459440.

- ^ "SAARC Is Dead. Long Live Subregional Cooperation". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- ^ "SAARC Visa Exemption Scheme Suspended For Pak Nationals: What It Means". www.ndtv.com. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- ^ Rid, Saeed Ahmed (2 January 2020). "Aman ki Asha (a desire for peace): a case study of a people-to-people contacts peacebuilding initiative between India and Pakistan". Contemporary South Asia. 28 (1): 113–125. doi:10.1080/09584935.2019.1666090. ISSN 0958-4935.

- ^ "The story of the Kartarpur Sahib Corridor in dates". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 6 May 2025.